Hormesis as a Particular Type of Plant Stress Response

Abstract

1. Introduction

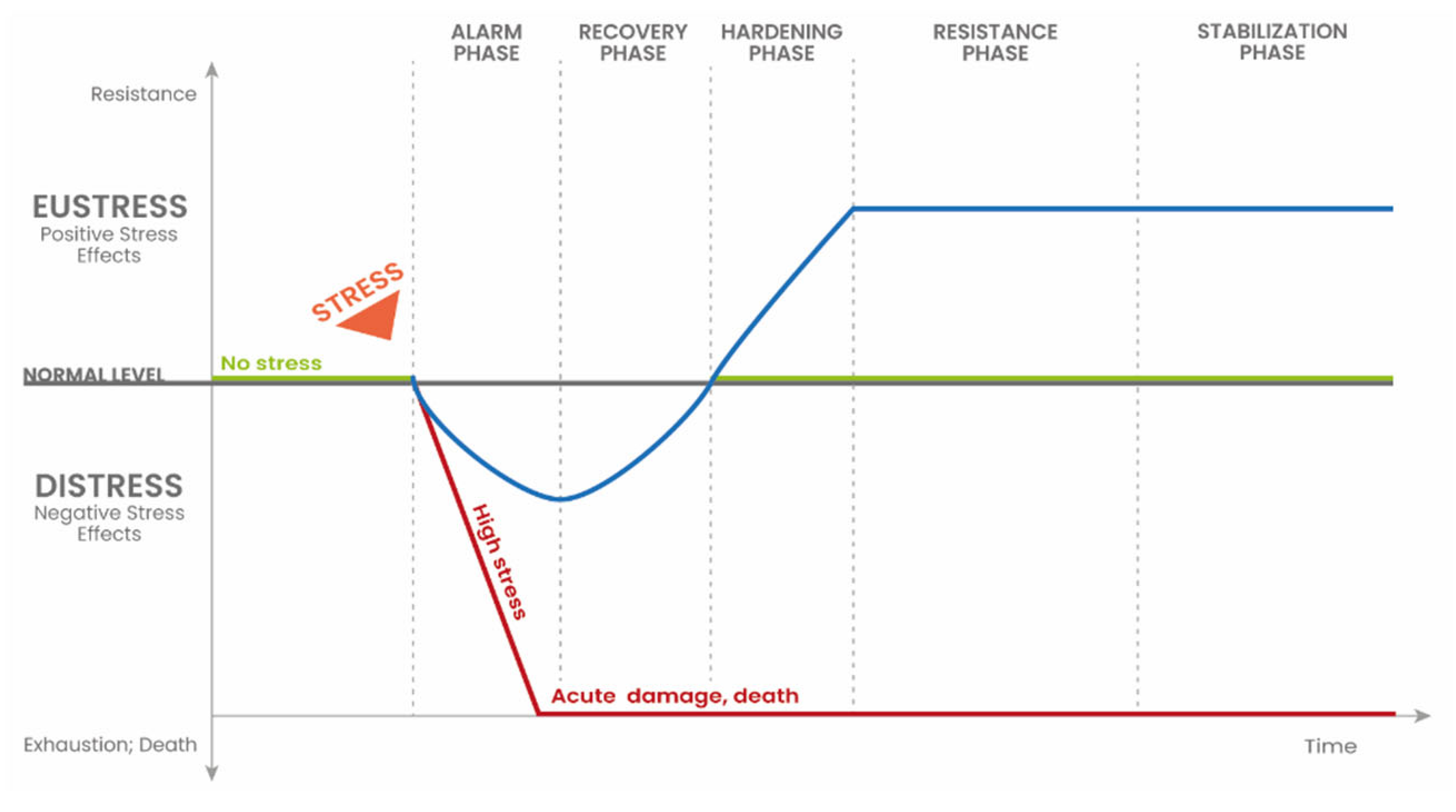

2. Plant Responses to Stress Factors

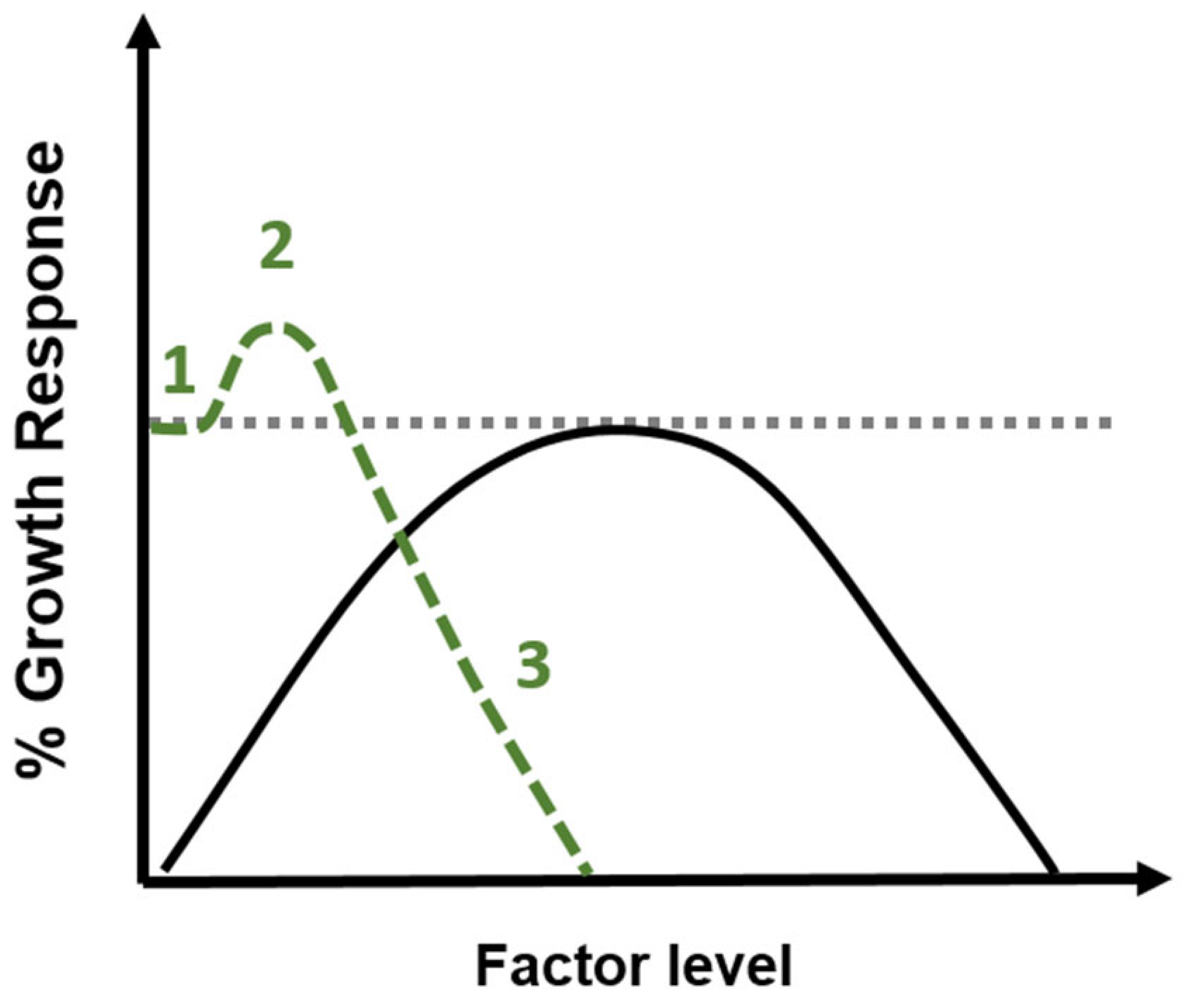

3. The Phenomenon of Hormesis

4. Other Stress-Related Processes

5. Experimental Assessment of Hormesis

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mittler, R.; Zandalinas, S.I.; Fichman, Y.; Van Breusegem, F. Reactive Oxygen Species Signalling in Plant Stress Responses. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2022, 23, 663–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calabrese, E.J.; Baldwin, L.A. Applications of Hormesis in Toxicology, Risk Assessment and Chemotherapeutics. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2002, 23, 331–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calabrese, E.J.; Baldwin, L.A. Hormesis: U-Shaped Dose Responses and Their Centrality in Toxicology. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2001, 22, 285–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calabrese, E.J. Paradigm Lost, Paradigm Found: The Re-Emergence of Hormesis as a Fundamental Dose Response Model in the Toxicological Sciences. Environ. Pollut. 2005, 138, 378–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kefford, B.J.; Zalizniak, L.; Warne, M.S.J.; Nugegoda, D. Is the Integration of Hormesis and Essentiality into Ecotoxicology Now Opening Pandora’s Box? Environ. Pollut. 2008, 151, 516–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saul, N.; Pietsch, K.; Stürzenbaum, S.R.; Menzel, R.; Steinberg, C.E.W. Hormesis and Longevity with Tannins: Free of Charge or Cost-Intensive? Chemosphere 2013, 93, 1005–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seyed Alian, R.; Dziewięcka, M.; Kędziorski, A.; Majchrzycki, Ł.; Augustyniak, M. Do Nanoparticles Cause Hormesis? Early Physiological Compensatory Response in House Crickets to a Dietary Admixture of GO, Ag, and GOAg Composite. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 788, 147801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agathokleous, E.; Calabrese, E.J. A Global Environmental Health Perspective and Optimisation of Stress. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 704, 135263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agathokleous, E.; Kitao, M.; Calabrese, E.J. Human and Veterinary Antibiotics Induce Hormesis in Plants: Scientific and Regulatory Issues and an Environmental Perspective. Environ. Int. 2018, 120, 489–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poschenrieder, C.; Cabot, C.; Martos, S.; Gallego, B.; Barceló, J. Do Toxic Ions Induce Hormesis in Plants? Plant Sci. 2013, 212, 15–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Migliore, L.; Cozzolino, S.; Fiori, M. Phytotoxicity to and Uptake of Flumequine Used in Intensive Aquaculture on the Aquatic Weed, Lythrum salicaria L. Chemosphere 2000, 40, 741–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jia, L.; He, X.; Chen, W.; Liu, Z.; Huang, Y.; Yu, S. Hormesis Phenomena under Cd Stress in a Hyperaccumulator—Lonicera japonica Thunb. Ecotoxicology 2013, 22, 476–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duman, F.; Ozturk, F.; Aydin, Z. Biological Responses of Duckweed (Lemna minor L.) Exposed to the Inorganic Arsenic Species As(III) and As(V): Effects of Concentration and Duration of Exposure. Ecotoxicology 2010, 19, 983–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González, C.I.; Maine, M.A.; Cazenave, J.; Sanchez, G.C.; Benavides, M.P. Physiological and Biochemical Responses of Eichhornia crassipes Exposed to Cr (III). Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2015, 22, 3739–3747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debeljak, M.; van Elteren, J.T.; Špruk, A.; Izmer, A.; Vanhaecke, F.; Vogel-Mikuš, K. The Role of Arbuscular Mycorrhiza in Mercury and Mineral Nutrient Uptake in Maize. Chemosphere 2018, 212, 1076–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Małkowski, E.; Sitko, K.; Szopí Nski, M.; Gieró, Z.; Pogrzeba, M.; Kalaji, H.M.; Ziele´znik-Rusinowska, P.Z. Hormesis in Plants: The Role of Oxidative Stress, Auxins and Photosynthesis in Corn Treated with Cd or Pb. Int. J. Mol. Sci. Artic. 2020, 21, 2099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamakis, I.D.S.; Sperdouli, I.; Hanć, A.; Dobrikova, A.; Apostolova, E.; Moustakas, M. Rapid Hormetic Responses of Photosystem II Photochemistry of Clary Sage to Cadmium Exposure. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stamelou, M.L.; Sperdouli, I.; Pyrri, I.; Adamakis, I.D.S.; Moustakas, M. Hormetic Responses of Photosystem II in Tomato to Botrytis cinerea. Plants 2021, 10, 521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mengdi, X.; Wenqing, C.; Haibo, D.; Xiaoqing, W.; Li, Y.; Yuchen, K.; Hui, S.; Lei, W. Cadmium-Induced Hormesis Effect in Medicinal Herbs Improves the Efficiency of Safe Utilization for Low Cadmium-Contaminated Farmland Soil. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2021, 225, 112724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Lin, I.; Yuan, X.; Zhu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Li, D.; He, J.; Xiao, Y. Low-Level Cadmium Exposure Induced Hormesis in Peppermint Young Plant by Constantly Activating Antioxidant Activity Based on Physiological and Transcriptomic Analyses. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1088285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfleeger, T.; Blakeley-Smith, M.; King, G.; Lee, E.H.; Plocher, M.; Olszyk, D. The Effects of Glyphosate and Aminopyralid on a Multi-Species Plant Field Trial. Ecotoxicology 2012, 21, 1771–1787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Kesel, J.; Conrath, U.; Flors, V.; Luna, E.; Mageroy, M.H.; Mauch-Mani, B.; Pastor, V.; Pozo, M.J.; Pieterse, C.M.J.; Ton, J.; et al. The Induced Resistance Lexicon: Do’s and Don’ts. Trends Plant Sci. 2021, 26, 685–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jalal, A.; de Oliveira Junior, J.C.; Ribeiro, J.S.; Fernandes, G.C.; Mariano, G.G.; Trindade, V.D.R.; Reis, A.R. dos Hormesis in Plants: Physiological and Biochemical Responses. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2021, 207, 111225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erofeeva, E.A. Environmental Hormesis of Non-Specific and Specific Adaptive Mechanisms in Plants. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 804, 150059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliveira, H.C.; Seabra, A.B.; Kondak, S.; Adedokun, O.P.; Kolbert, Z. Multilevel Approach to Plant–Nanomaterial Relationships: From Cells to Living Ecosystems. J. Exp. Bot. 2023, 74, 3406–3424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muszyńska, E.; Labudda, M. Dual Role of Metallic Trace Elements in Stress Biology—From Negative to Beneficial Impact on Plants. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 3117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, M.E.A.; Castro, P.R.C.; Azevedo, R.A. Hormesis in Plants under Cd Exposure: From Toxic to Beneficial Element? J. Hazard. Mater. 2020, 384, 121434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erofeeva, E.A. Environmental Hormesis: From Cell to Ecosystem. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sci. Health 2022, 29, 100378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moustakas, M.; Moustaka, J.; Sperdouli, I. Hormesis in Photosystem II: A Mechanistic Understanding. Curr. Opin. Toxicol. 2022, 29, 57–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agathokleous, E. Dosing Requirements to Untangle Hormesis in Plant Science. Trends Plant Sci. 2025, 30, 1189–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agathokleous, E.; Feng, Z.Z.; Peñuelas, J. Chlorophyll Hormesis: Are Chlorophylls Major Components of Stress Biology in Higher Plants? Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 726, 138637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erofeeva, E.A. Plant Stress Plant Hormesis: The Energy Aspect of Low and High-Dose Stresses. Plant Stress 2024, 14, 100628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolbert, Z.; Szollosi, R.; Rónavári, A.; Molnár, Á. Nanoforms of Essential Metals: From Hormetic Phytoeffects to Agricultural Potential. J. Exp. Bot. 2022, 73, 1825–1840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agathokleous, E.; Kitao, M.; Calabrese, E.J. Hormesis: A Compelling Platform for Sophisticated Plant Science. Trends Plant Sci. 2019, 24, 318–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sims, D.A.; Cheng, W.; Luo, Y.; Seemann, J.R. Photosynthetic Acclimation to Elevated CO2 in a Sunflower Canopy. J. Exp. Bot. 1999, 50, 645–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.; Li, H.; Liu, T.; Polle, A.; Peng, C.; Luo, Z. Bin Nitrogen Metabolism of Two Contrasting Poplar Species during Acclimation to Limiting Nitrogen Availability. J. Exp. Bot. 2013, 64, 4207–4224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wentworth, M.; Murchie, E.H.; Gray, J.E.; Villegas, D.; Pastenes, C.; Pinto, M.; Horton, P. Differential Adaptation of Two Varieties of Common Bean to Abiotic Stress II. Acclimation of Photosynthesis. J. Exp. Bot. 2006, 57, 699–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, L.; Zhang, J.; Li, L.; Xiao, C.; Feng, X.; Chen, S.; Guo, L.; Hu, H. Involvement of Abscisic Acid, ABI5, and PPC2 in Plant Acclimation to Low CO2. J. Exp. Bot. 2020, 71, 4093–4108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauerle, W.L.; Bowden, J.D.; Wang, G.G. The Influence of Temperature on Within-Canopy Acclimation and Variation in Leaf Photosynthesis: Spatial Acclimation to Microclimate Gradients among Climatically Divergent Acer rubrum L. Genotypes. J. Exp. Bot. 2007, 58, 3285–3298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Galviz, Y.; Souza, G.M.; Lüttge, U. The Biological Concept of Stress Revisited: Relations of Stress and Memory of Plants as a Matter of Space–Time. Theor. Exp. Plant Physiol. 2022, 34, 239–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kranner, I.; Minibayeva, F.V.; Beckett, R.P.; Seal, C.E. What Is Stress? Concepts, Definitions and Applications in Seed Science. New Phytol. 2010, 188, 655–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mosa, K.A.; Ismail, A.; Helmy, M. Introduction to Plant Stresses. In Plant Stress Tolerance; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; pp. 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lichtenthaler, H.K. The Stress Concept in Plants: An Introduction. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1998, 851, 187–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reddy, A.R.; Chaitanya, K.V.; Vivekanandan, M. Drought-Induced Responses of Photosynthesis and Antioxidant Metabolism in Higher Plants. J. Plant Physiol. 2004, 161, 1189–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shao, H.B.; Guo, Q.J.; Chu, L.Y.; Zhao, X.N.; Su, Z.L.; Hu, Y.C.; Cheng, J.F. Understanding Molecular Mechanism of Higher Plant Plasticity under Abiotic Stress. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2007, 54, 37–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheppard, S.C.; Regitnig, P.J. Factors Controlling the Hormesis Response in Irradiated Seed. Health Phys. 1987, 52, 599–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, Q.; Fan, L.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, J.; Jiang, Y.; Yang, J.; Li, G.; Fahad, S.; Agathokleous, E.; Chen, Y.; et al. Transcriptomic and Ultrastructural Insights into Zinc-Induced Hormesis in Wheat Seedlings: Glutathione-Mediated Antioxidant Defense in Zinc Toxicity Regulation. Plant Stress 2025, 16, 100820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erofeeva, E.A. Hormesis in Plants: Its Common Occurrence across Stresses. Curr. Opin. Toxicol. 2022, 30, 100333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erofeeva, E.A. Plant Hormesis and Shelford’s Tolerance Law Curve. J. For. Res. 2021, 32, 1789–1802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agathokleous, E.; Calabrese, E.J.; Fotopoulos, V. Low-Dose Stress Promotes Sustainable Food Production. npj Sustain. Agric. 2024, 2, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godínez-Mendoza, P.L.; Rico-Chávez, A.K.; Ferrusquía-Jimenez, N.I.; Carbajal-Valenzuela, I.A.; Villagómez-Aranda, A.L.; Torres-Pacheco, I.; Guevara-González, R.G. Plant Hormesis: Revising of the Concepts of Biostimulation, Elicitation and Their Application in a Sustainable Agricultural Production. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 894, 164883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kendig, E.L.; Le, H.H.; Belcher, S.M. Defining Hormesis: Evaluation of a Complex Concentration Response Phenomenon. Int. J. Toxicol. 2010, 29, 235–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agathokleous, E.; Belz, R.G.; Calatayud, V.; De Marco, A.; Hoshika, Y.; Kitao, M.; Saitanis, C.J.; Sicard, P.; Paoletti, E.; Calabrese, E.J. Predicting the Effect of Ozone on Vegetation via Linear Non-Threshold (LNT), Threshold and Hormetic Dose-Response Models. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 649, 61–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maksymiec, W. Signaling Responses in Plants to Heavy Metal Stress. Acta Physiol. Plant. 2007, 29, 177–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marino, D.; Dunand, C.; Puppo, A.; Pauly, N. A Burst of Plant NADPH Oxidases. Trends Plant Sci. 2012, 17, 9–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodrigo-Moreno, A.; Poschenrieder, C.; Shabala, S. Transition Metals: A Double Edge Sward in ROS Generation and Signaling. Plant Signal. Behav. 2013, 8, e23425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gururani, M.A.; Venkatesh, J.; Tran, L.S.P. Regulation of Photosynthesis during Abiotic Stress-Induced Photoinhibition. Mol. Plant 2015, 8, 1304–1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Zhang, J.; Sun, X.; Agathokleous, E.; Zheng, G. Atmospheric Pb Induced Hormesis in the Accumulator Plant Tillandsia usneoides. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 811, 152384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magalhaes, J.V.; Liu, J.; Guimarães, C.T.; Lana, U.G.P.; Alves, V.M.C.; Wang, Y.-H.; Schaffert, R.E.; Hoekenga, O.A.; Piñeros, M.A.; Shaff, J.E.; et al. A Gene in the Multidrug and Toxic Compound Extrusion (MATE) Family Confers Aluminum Tolerance in Sorghum. Nat. Genet. 2007, 39, 1156–1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arroyave, C.; Barceló, J.; Poschenrieder, C.; Tolrà, R. Aluminium-Induced Changes in Root Epidermal Cell Patterning, a Distinctive Feature of Hyperresistance to Al in Brachiaria decumbens. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2011, 105, 1477–1483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seth, C.S.; Kumar Chaturvedi, P.; Misra, V. The Role of Phytochelatins and Antioxidants in Tolerance to Cd Accumulation in Brassica juncea L. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2008, 71, 76–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; He, X.; Chen, W.; Yuan, F.; Yan, K.; Tao, D. Accumulation and Tolerance Characteristics of Cadmium in a Potential Hyperaccumulator—Lonicera japonica Thunb. J. Hazard. Mater. 2009, 169, 170–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Souza, L.A.; Camargos, L.S.; Carvalho, M.E.A. Toxic Metal Phytoremediation Using High Biomass Non-Hyperaccumulator Crops: New Possibilities for Bioenergy Resources. In Phytoremediation Methods, Management and Assessment; NOVA Science Publishers: Hauppauge, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Kitajima, K.; Hogan, K.P. Increases of Chlorophyll a/b Ratios during Acclimation of Tropical Woody Seedlings to Nitrogen Limitation and High Light. Plant Cell Environ. 2003, 26, 857–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, Y.-T.; Qiu, R.-L.; Zeng, X.-W.; Ying, R.-R.; Yu, F.-M.; Zhou, X.-Y. Lead, Zinc, Cadmium Hyperaccumulation and Growth Stimulation in Arabis paniculata Franch. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2009, 66, 126–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ying, R.R.; Qiu, R.L.; Tang, Y.T.; Hu, P.J.; Qiu, H.; Chen, H.R.; Shi, T.H.; Morel, J.L. Cadmium Tolerance of Carbon Assimilation Enzymes and Chloroplast in Zn/Cd Hyperaccumulator Picris divaricata. J. Plant Physiol. 2010, 167, 81–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; He, X.; Chen, W. Effects of Cadmium Hyperaccumulation on the Concentrations of Four Trace Elements in Lonicera japonica Thunb. Ecotoxicology 2011, 20, 698–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muszyńska, E.; Hanus-Fajerska, E.; Ciarkowska, K. Studies on Lead and Cadmium Toxicity in Dianthus carthusianorum Calamine Ecotype Cultivated In Vitro. Plant Biol. 2018, 20, 474–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, V. Environmental Plant Physiology: Botanical Strategies for a Climate Smart Planet; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2020; ISBN 9781003014997. [Google Scholar]

- Giordano, M. Homeostasis: An Underestimated Focal Point of Ecology and Evolution. Plant Sci. 2013, 211, 92–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutzat, R.; Mittelsten Scheid, O. Epigenetic Responses to Stress: Triple Defense? Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2012, 15, 568–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crisp, P.A.; Ganguly, D.; Eichten, S.R.; Borevitz, J.O.; Pogson, B.J. Reconsidering Plant Memory: Intersections between Stress Recovery, RNA Turnover, and Epigenetics. Sci. Adv. 2016, 2, e1501340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartman, S.; Sasidharan, R.; Voesenek, L.A.C.J. The Role of Ethylene in Metabolic Acclimations to Low Oxygen. New Phytol. 2021, 229, 64–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, X.; Li, L.; Narsai, R.; De Clercq, I.; Whelan, J.; Berkowitz, O. Mitochondrial Signalling Is Critical for Acclimation and Adaptation to Flooding in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 2020, 103, 227–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harb, A.; Krishnan, A.; Ambavaram, M.M.R.; Pereira, A. Molecular and Physiological Analysis of Drought Stress in Arabidopsis Reveals Early Responses Leading to Acclimation in Plant Growth. Plant Physiol. 2010, 154, 1254–1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hassan, M.A.; Xiang, C.; Farooq, M.; Muhammad, N.; Yan, Z.; Hui, X.; Yuanyuan, K.; Bruno, A.K.; Lele, Z.; Jincai, L. Cold Stress in Wheat: Plant Acclimation Responses and Management Strategies. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 676884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charng, Y.Y.; Mitra, S.; Yu, S.J. Maintenance of Abiotic Stress Memory in Plants: Lessons Learned from Heat Acclimation. Plant Cell 2023, 35, 187–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullineaux, C.W.; Emlyn-Jones, D. State Transitions: An Example of Acclimation to Low-Light Stress. J. Exp. Bot. 2005, 56, 389–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karpiński, S.; Szechyńska-Hebda, M.; Wituszyńska, W.; Burdiak, P. Light Acclimation, Retrograde Signalling, Cell Death and Immune Defences in Plants. Plant Cell Environ. 2013, 36, 736–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazihizina, N.; Taiti, C.; Marti, L.; Rodrigo-Moreno, A.; Spinelli, F.; Giordano, C.; Caparrotta, S.; Gori, M.; Azzarello, E.; Mancuso, S. Zn2+-Induced Changes at the Root Level Account for the Increased Tolerance of Acclimated Tobacco Plants. J. Exp. Bot. 2014, 65, 4931–4942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulten, A.; Bytomski, L.; Quintana, J.; Bernal, M.; Krämer, U. Do Arabidopsis Squamosa Promoter Binding Protein-Like Genes Act Together in Plant Acclimation to Copper or Zinc Deficiency? Plant Direct 2019, 3, e00150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.; Vitousek, P.M.; Mao, Q.; Gilliam, F.S.; Luo, Y.; Zhou, G.; Zou, X.; Bai, E.; Scanlon, T.M.; Hou, E.; et al. Plant Acclimation to Long-Term High Nitrogen Deposition in an N-Rich Tropical Forest. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, 5187–5192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Yang, X.; Liu, H.; Wang, W.; Wang, C.; Ding, G.; Xu, F.; Wang, S.; Cai, H.; Hammond, J.P.; et al. Local and Systemic Responses Conferring Acclimation of Brassica napus Roots to Low Phosphorus Conditions. J. Exp. Bot. 2022, 73, 4753–4777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, R.J.; Yang, Y.; Yan, Y.W.; Mao, D.D.; Yuan, H.M.; Wang, C.; Zhao, F.G.; Luan, S. Two Transporters Mobilize Magnesium from Vacuolar Stores to Enable Plant Acclimation to Magnesium Deficiency. Plant Physiol. 2022, 190, 1307–1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carvalho, M.E.A.; Piotto, F.A.; Gaziola, S.A.; Jacomino, A.P.; Jozefczak, M.; Cuypers, A.; Azevedo, R.A. New Insights about Cadmium Impacts on Tomato: Plant Acclimation, Nutritional Changes, Fruit Quality and Yield. Food Energy Secur. 2018, 7, e00131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokarz, K.M.; Makowski, W.; Tokarz, B.; Hanula, M.; Sitek, E.; Muszyńska, E.; Jędrzejczyk, R.; Banasiuk, R.; Chajec, Ł.; Mazur, S. Can Ceylon Leadwort (Plumbago zeylanica L.) Acclimate to Lead Toxicity?—Studies of Photosynthetic Apparatus Efficiency. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 1866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iven, V.; Vanbuel, I.; Hendrix, S.; Cuypers, A. The Glutathione-Dependent Alarm Triggers Signalling Responses Involved in Plant Acclimation to Cadmium. J. Exp. Bot. 2023, 74, 3300–3312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choudhury, F.K.; Rivero, R.M.; Blumwald, E.; Mittler, R. Reactive Oxygen Species, Abiotic Stress and Stress Combination. Plant J. 2017, 90, 856–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, R.S.; Franklin, C.E. Testing the Beneficial Acclimation Hypothesis. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2002, 17, 66–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Tang, Z.; Agathokleous, E.; Zheng, G.; Xu, L.; Li, P. Hormesis in the Heavy Metal Accumulator Plant Tillandsia ionantha under Cd Exposure: Frequency and Function of Different Biomarkers. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 889, 164328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, R.D. Plant Metabolomics: From Holistic Hope, to Hype, to Hot Topic. New Phytol. 2006, 169, 453–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sze, H.; Palanivelu, R.; Harper, J.F.; Johnson, M.A. Holistic Insights from Pollen Omics: Co-Opting Stress-Responsive Genes and ER-Mediated Proteostasis for Male Fertility. Plant Physiol. 2021, 187, 2361–2380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanclemente, M. A Holistic Evaluation of Nitrogen Responses in Maize. Plant Physiol. 2024, 195, 276–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szopiński, M.; Sitko, K.; Rusinowski, S.; Zieleźnik-Rusinowska, P.; Corso, M.; Rostański, A.; Rojek-Jelonek, M.; Verbruggen, N.; Małkowski, E. Different Strategies of Cd Tolerance and Accumulation in Arabidopsis halleri and Arabidopsis arenosa. Plant Cell Environ. 2020, 43, 3002–3019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rusinowski, S.; Szada-Borzyszkowska, A.; Zieleźnik-Rusinowska, P.; Małkowski, E.; Krzyżak, J.; Woźniak, G.; Sitko, K.; Szopiński, M.; McCalmont, J.P.; Kalaji, H.M. How Autochthonous Microorganisms Influence Physiological Status of Zea mays L. Cultivated on Heavy Metal Contaminated Soils? Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2019, 26, 4746–4763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antonkiewicz, J.; Kołodziej, B.; Bielińska, E.J. The Use of Reed Canary Grass and Giant Miscanthus in the Phytoremediation of Municipal Sewage Sludge. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2016, 23, 9505–9517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antonkiewicz, J.; Popławska, A.; Kołodziej, B.; Ciarkowska, K.; Gambuś, F.; Bryk, M.; Babula, J. Application of Ash and Municipal Sewage Sludge as Macronutrient Sources in Sustainable Plant Biomass Production. J. Environ. Manag. 2020, 264, 110450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonkiewicz, J.; Kołodziej, B.; Bryk, M.; Kądziołka, M.; Pełka, R.; Koliopoulos, T. Sustainable Management of Bottom Ash and Municipal Sewage Sludge as a Source of Micronutrients for Biomass Production. Sustainability 2025, 17, 7493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzmán-Báez, G.A.; Trejo-Téllez, L.I.; Ramírez-Olvera, S.M.; Salinas-Ruíz, J.; Bello-Bello, J.J.; Alcántar-González, G.; Hidalgo-Contreras, J.V.; Gómez-Merino, F.C. Silver Nanoparticles Increase Nitrogen, Phosphorus, and Potassium Concentrations in Leaves and Stimulate Root Length and Number of Roots in Tomato Seedlings in a Hormetic Manner. Dose-Response 2021, 19, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agathokleous, E.; Kitao, M.; Harayama, H. On the Nonmonotonic, Hormetic Photoprotective Response of Plants to Stress. Dose-Response 2019, 17, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raja, V.; Majeed, U.; Kang, H.; Andrabi, K.I.; John, R. Abiotic Stress: Interplay between ROS, Hormones and MAPKs. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2017, 137, 142–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Zhao, X.; Zhang, Q.; Zhou, Z.; Dou, Y.; Ji, W.; Li, J. Comparative Transcriptome Analysis of Broccoli Seedlings under Different Cd Exposure Levels Revealed Possible Pathways Involved in Hormesis. Sci. Hortic. 2022, 304, 111330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Qin, M.; Yan, J.; Jia, T.; Sun, X.; Pan, J.; Li, W.; Liu, Z.; El-Sheikh, M.A.; Ahmad, P.; et al. Hormesis Effect of Cadmium on Pakchoi Growth: Unraveling the ROS-Mediated IAA-Sugar Metabolism from Multi-Omics Perspective. J. Hazard. Mater. 2025, 487, 137265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mittler, R.; Blumwald, E. The Roles of ROS and ABA in Systemic Acquired Acclimation. Plant Cell 2015, 27, 64–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Zhao, Y.; Zhu, J.-K. Thriving under Stress: How Plants Balance Growth and the Stress Response. Dev. Cell 2020, 55, 529–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Cui, Y.; Li, J.; Xu, N.; Shi, T.; Sun, Y.; Zhang, C. Glyphosate Hormesis Stimulates Tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.) Plant Growth and Enhances Tolerance against Environmental Abiotic Stress by Triggering Nonphotochemical Quenching. Pest Manag. Sci. 2024, 80, 3628–3639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiao, Q.; Li, G.; Li, L.; Lin, D.; Xu, Z.; Fan, L.; Zhang, J.; Shen, F.; Liu, S.; Seth, C.S. Hormetic Responses to Cadmium Exposure in Wheat Seedlings: Insights into Morphological, Physiological, and Biochemical Adaptations. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2024, 31, 57701–57719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viswanathan, D.; Christudoss, A.C.; Seenivasan, R.; Mukherjee, A. Decoding Plant Hormesis: Cerium Oxide Nanoparticles and the Role of Soil EPS in the Growth Dynamics of Allium sativum L. ACS Agric. Sci. Technol. 2024, 5, 61–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thunb, L. Hormesis Effects Induced by Cadmium on Growth and Photosynthetic Performance in a Hyperaccumulator, Lonicera japonica Thunb. J. Plant Growth Regul. 2015, 34, 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, N.; Sun, Y.; Wang, Y.; Cui, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Zhang, C. Hormesis Effects in Tomato Plant Growth and Photosynthesis Due to Acephate Exposure Based on Physiology and Transcriptomic Analysis. Pest Manag. Sci. 2023, 79, 2029–2039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salinitro, M.; Mattarello, G.; Guardigli, G.; Odajiu, M.; Tassoni, A. Induction of Hormesis in Plants by Urban Trace Metal Pollution. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 20329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, R.N.; Bevilaqua, N.d.C.; Krenchinski, F.H.; Giovanelli, B.F.; Pereira, V.G.C.; Velini, E.D.; Carbonari, C.A. Hormetic Effect of Glyphosate on the Morphology, Physiology and Metabolism of Coffee Plants. Plants 2023, 12, 2249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Faria, G.S.; Carlos, L.; Jakelaitis, A.; de Freitas, S.T.F.; Vicentini, T.A.; Silva, I.O.F.; Vasconcelos Filho, S.C.; Lourenço, L.L.; Farnese, F.S.; Batista, M.A. Hormetic Effect Caused by Sublethal Doses of Glyphosate on Toona ciliata M. Roem. Plants 2023, 12, 4163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.; Luo, Q.; Liu, S.; Zhao, Y.; Long, Y.; Pan, Y. Screening Ornamental Plants to Identify Potential Cd Hyperaccumulators for Bioremediation. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2018, 162, 35–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Process | Definition |

|---|---|

| Acclimation | A facultative physiological modification during the individual life of a plant in response to changes in environmental factor(s) necessary for the plant to function correctly, e.g., fluctuations in water, light, macro- and micronutrients, and concentrations of CO2 and O2, as well as toxic factors as toxic trace elements or toxic organic substances. |

| Adaptation | A genetically conserved, heritable modification in the genome of plants to survive and reproduce in a hostile environment. Examples of adaptation include photosynthetic processes in CAM and C4 plants or hyperaccumulation of Zn and Cd in Arabidopsis halleri. |

| Hormesis | A beneficial effect of low doses of toxic factor(s), e.g., Cd, Hg, Pb, ozone, and herbicides, on plant growth response and fitness. |

| Priming | The capacity of plants to memorise environmental stresses, thereby improving their responses to recurrent stress. |

| No. | Hormesis-Inducing Factor | Plant Species | Parameters Analysed | Findings | Publication Details |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Cadmium | Polygonatum sibiricum | plant biomass, photosynthetic efficiency, and polysaccharide content, as well as CAT, SOD and POD activity and MDA content were measured. Moreover, the polysaccharide contents (PCP1, PCP2 and PCP3) were determined. | A hormetic increase in plant biomass was observed, accompanied by enhanced photosynthetic efficiency, increased antioxidant activity, and a higher polysaccharide content. | [19] |

| 2 | Glyphosate | Solanum lycopersicum | The plant growth reaction (height), photosynthetic pigment content, photosynthetic efficiency, antioxidant enzyme activity (CAT, SOD and POD) and non-photochemical quenching and expression of genes related to NPQ were analysed. | In the case of low doses of glyphosate, an increase in photosynthetic pigment content and photosynthesis efficiency, enhanced antioxidant enzyme activity, and increased plant growth were observed. | [106] |

| 3 | Cadmium | Triticum aestivum | The plant biomass, root morphology and development, photosynthetic rate, stomatal conductance, intercellular carbon dioxide concentration, and transpiration rate, along with MDA, non-protein thiol (NPT), phytochelatin, and glutathione content, were determined. Moreover, antioxidant enzymes activity was also analysed. | An increase in whole-plant biomass, improved root development and enhanced photosynthetic rate were observed in the presence of a low cadmium concentration. This hormetic response is connected with the enhancement of the photosynthetic and antioxidant system. | [107] |

| 4 | Cerium oxide nanoparticles | Allium sativum | Growth parameters such as the length and fresh and dry mass of roots and shoots, together with the mitotic index, levels of MDA and ROS, photosynthetic pigment content, and soluble sugar and protein content, were measured. | Hormesis was observed in the presence of cerium oxide nanoparticles, with increased growth, decreased levels of ROS and MDA, increased carbohydrate and protein content, increased photosynthetic pigment levels, and a higher mitotic index. | [108] |

| 5 | Cadmium | Lonicera japonica Thunb. |

The net photosynthesis rate, stomatal conductance, intercellular CO2 concentration and transpiration rate, as well as photosynthetic pigment contents, photosynthetic efficiency and total plant biomass were measured. | Increased levels of net photosynthesis rate, photosynthetic pigments, enhanced photosynthetic efficiency, and higher total plant biomass were detected in the case of low cadmium concentration. | [109] |

| 6 | Acephate | Solanum lycopersicum L. | The shoot height, root length, and dry weight (DW) of shoots and roots, as well as chlorophyll a fluorescence, photosynthesis pigment content, and CAT, SOD and POT activity, were measured. Moreover, the expression levels of genes involved in the photosynthesis antenna were also analysed. | An increase in plant biomass and photosynthetic rate, as well as increased photosynthetic pigment content, was observed in the presence of low doses of acephate. A similar effect was recorded for genes participating in photosynthesis. | [110] |

| 7 | Cadmium, Chromium, Lead | Cardamine hirsuta, Poa annua, Stellaria media | The root and shoot dry biomass, number of nodes, leaf area, and photosynthetic pigment content were analysed. | In the presence of chromium for all species tested, the dry biomass of both the roots and shoots increased, as did the number of nodes. However, in the presence of cadmium, a similar hormetic reaction to that described above was observed only for C. hirsuta and P. annua. Furthermore, in the case of the latter species, this reaction was also accompanied by an increase in leaf area and in the content of photosynthetic pigments. | [111] |

| 8 | Cadmium | Brassica chinensis L. | Phenotyping of the whole plant, leaf cell anatomy, shoot fresh biomass, and CAT, SOD and POD activity, as well as H2O2, O2˙, and MDA content, were measured. Moreover, analysis of the level of soluble sugars and sequencing of the transcriptome and metabolome were performed. | Brassica chinensis showed an increase in shoot biomass and enhanced he antioxidant system when treated with low levels of cadmium. Moreover, enhanced IAA biosynthesis signalling and the plants’ sugar metabolic pathways were observed. | [103] |

| 9 | Cadmium | Brassica oleracea | The fresh plant biomass, as well as levels of IAA, GSH, GSSG, glucosinolate and MDA, were measured. Additionally, differences in gene expression were analysed in order to identify hormesis-related ones. | Treatment of Brassica oleracea with low cadmium doses resulted in an increase in plant biomass, enhanced auxin biosynthesis and an increase in the ratio of reduced to oxidised glutathione. Moreover, up-regulated genes under low Cd concentrations were identified as potentially related to hormesis, such as a transcription factor regulating the Fe deficiency response; an enzyme catalysing the degradation of GSLs; enzymes modulating the structure of the cell wall; and proteins involved in the photosystem II unit. | [102] |

| 10 | Glyphosate | Coffea arabica | Plant height, leaf number, leaf area, total dry biomass, CO2 assimilation, transpiration and stomatal conductance, carboxylation efficiency, intrinsic water use efficiency, rate of electron transport, photosynthetic efficiency, and content of shikimic acid pathway compounds were analysed. | Treatment with low concentrations of glyphosate increased plant biomass, improved photosynthetic efficiency and caused beneficial changes in morphology and biochemistry (shikimic acid pathway compounds). | [112] |

| 11 | Glyphosate | Toona ciliata | Plant height and stem diameter, chlorophyll a fluorescence, net carbon assimilation rate, stomatal conductance, transpiration rate, internal CO2 concentration and ratio of internal to external CO2 were measured. Moreover, morphoanatomical characterisation and visible leaf symptom analyses were performed. | Toone ciliata exhibited increased plant height and photochemical yield (photosynthetic rate and carboxylation efficiency) in response to lower doses of glyphosate. | [113] |

| 12 | Cadmium | Celosia argentea, Celosia cristata, Malva crispa and Malva rotundifolia | The shoot length, leaf area, shoot and root dry biomass, Cd bioaccumulation (BCF) and translocation (TF) coefficients, as well as the tolerance index (TI), were measured. | The introduction of a low cadmium concentration resulted in an increase in both shoot and root biomass in the case of Celosia argentea, Celosia cristata, Malva crispa and Malva rotundifolia. | [114] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Siemieniuk, A.; Rudnicka, M.; Jemioła, G.; Małkowski, E. Hormesis as a Particular Type of Plant Stress Response. Plants 2025, 14, 3815. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14243815

Siemieniuk A, Rudnicka M, Jemioła G, Małkowski E. Hormesis as a Particular Type of Plant Stress Response. Plants. 2025; 14(24):3815. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14243815

Chicago/Turabian StyleSiemieniuk, Agnieszka, Małgorzata Rudnicka, Gabriela Jemioła, and Eugeniusz Małkowski. 2025. "Hormesis as a Particular Type of Plant Stress Response" Plants 14, no. 24: 3815. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14243815

APA StyleSiemieniuk, A., Rudnicka, M., Jemioła, G., & Małkowski, E. (2025). Hormesis as a Particular Type of Plant Stress Response. Plants, 14(24), 3815. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14243815