Transcriptomics and Gene Family Identification of Cell Wall-Related Differentially Expressed Genes Reveal MaXTH32.5 Involved in Fruit Firmness During Banana Ripening

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Analysis of Changes in Physiological Indicators During Banana Fruit Ripening

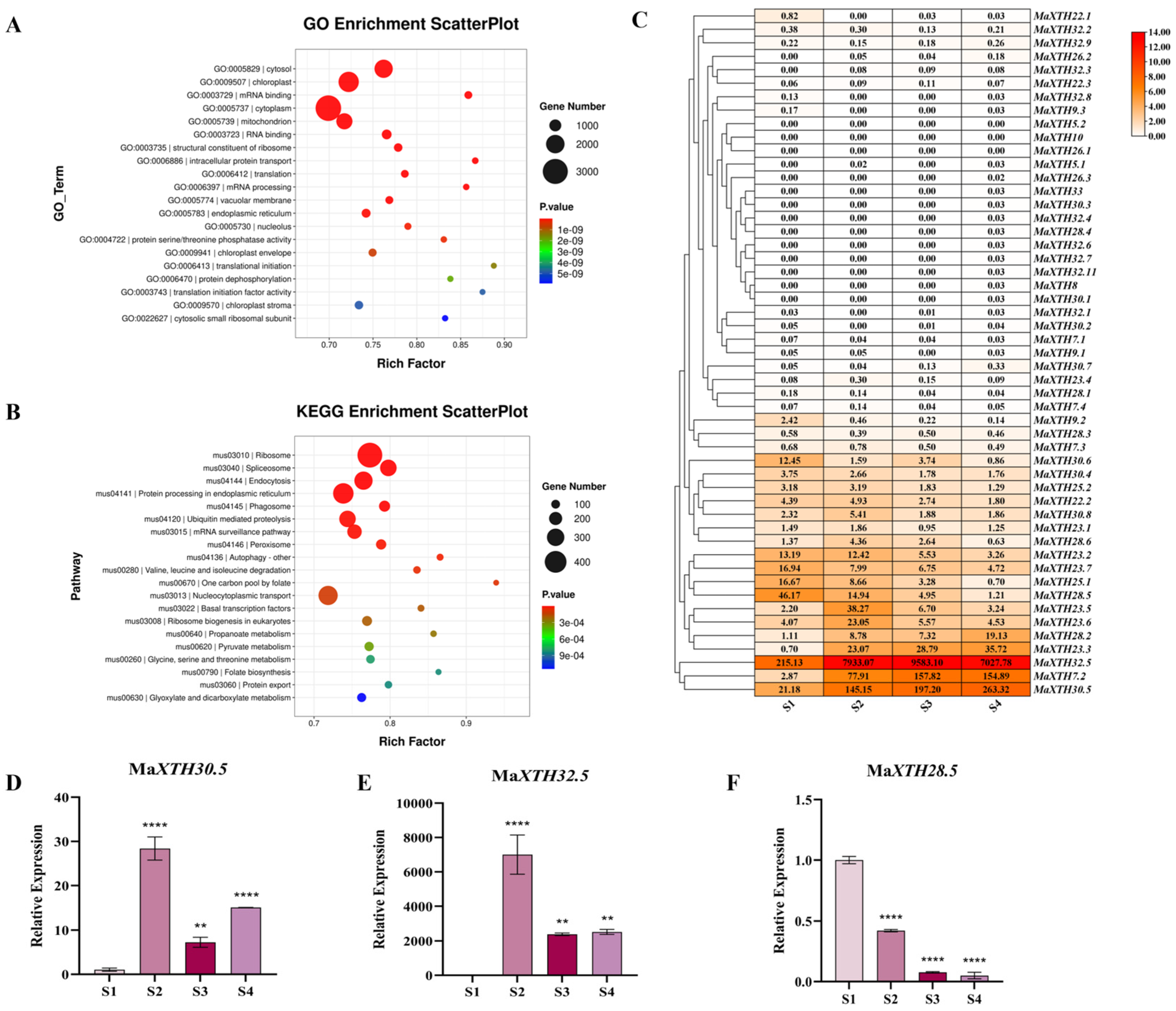

2.2. Transcriptome Reveals the Differential Expression of MaXTH During Fruit Ripening

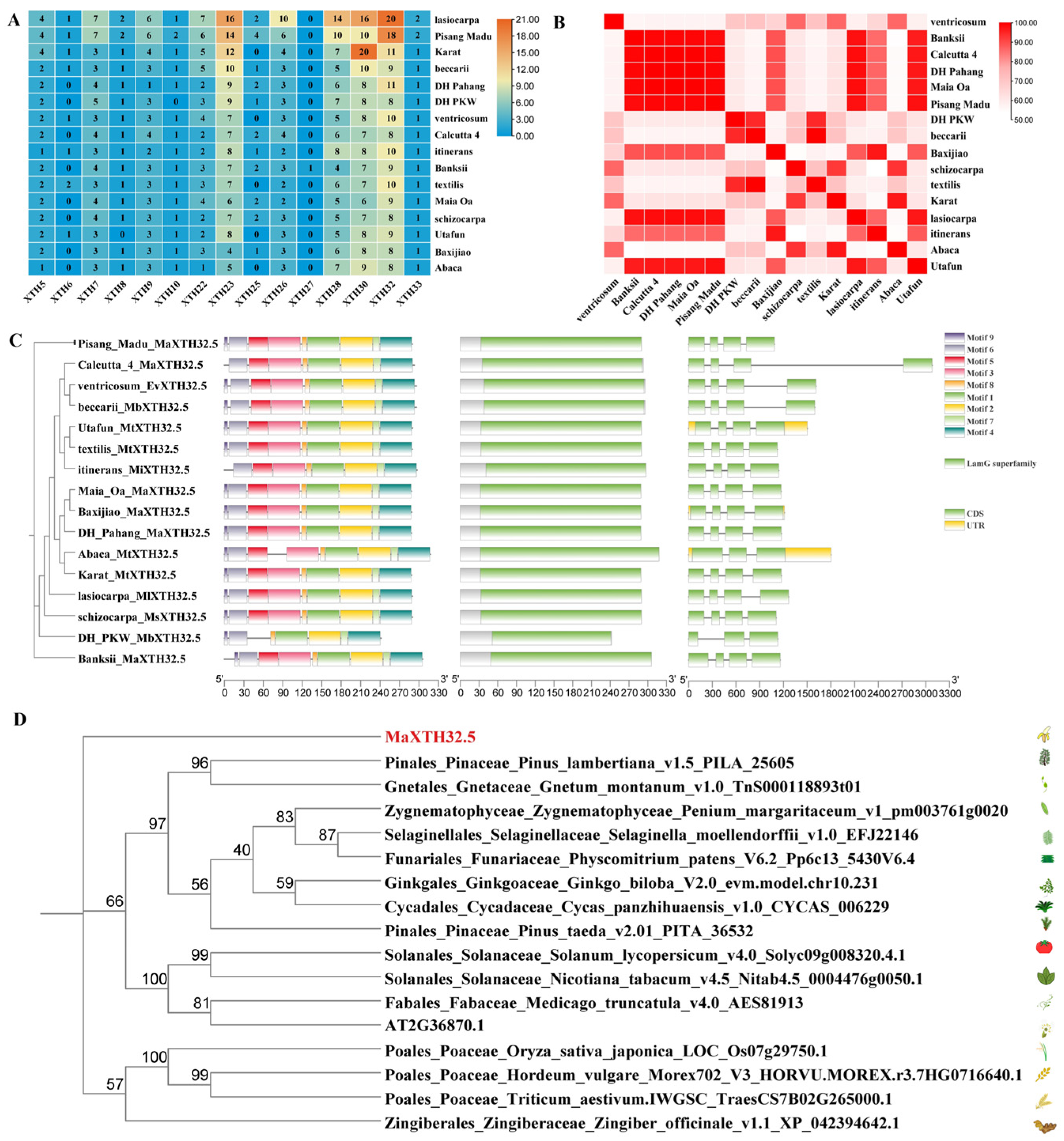

2.3. Identification and Characteristics of XTH32.5s

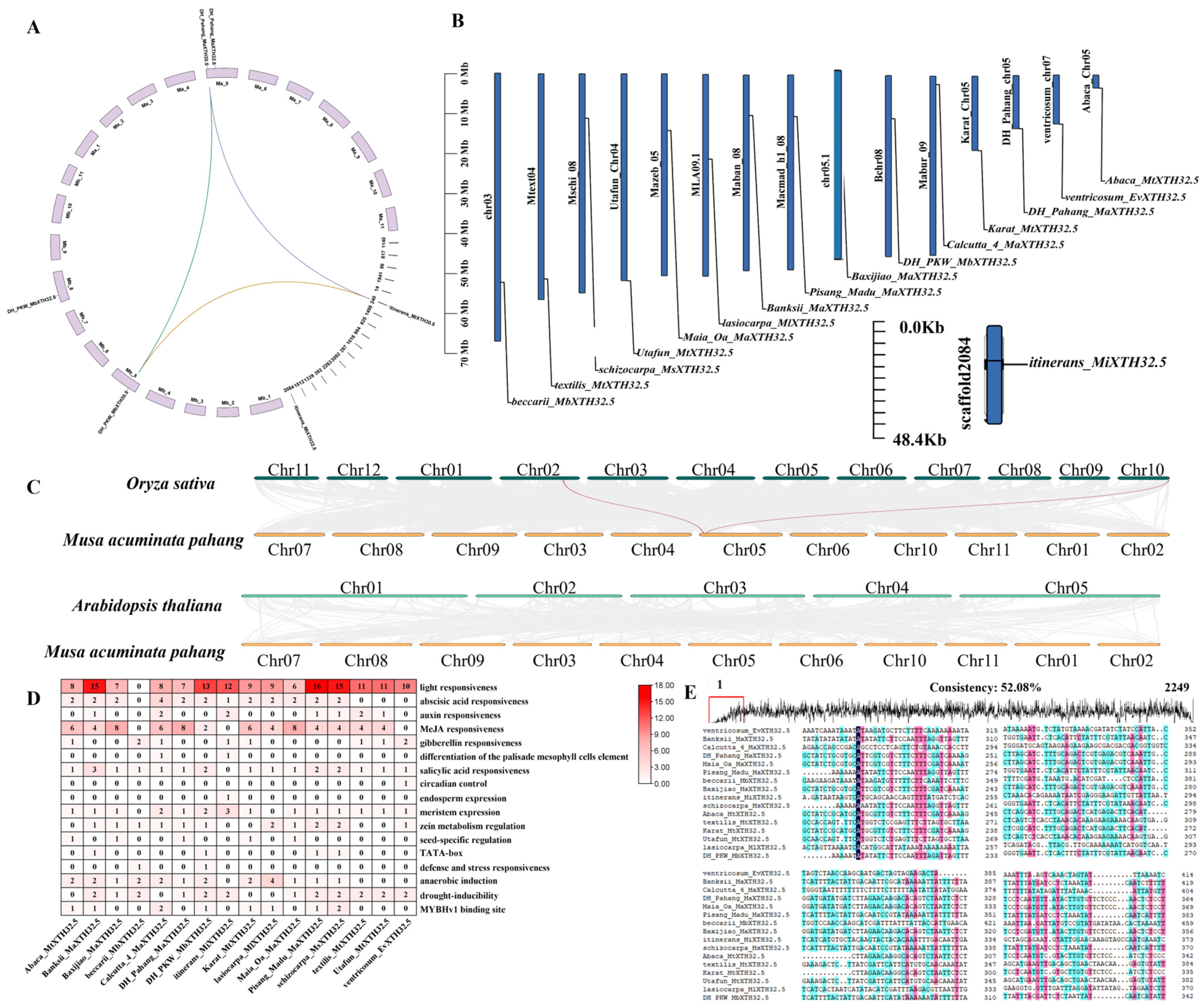

2.4. Chromosomal Distribution, Synteny, Cis-Acting Elements, and Sequence Differences of MaXTH32.5

2.5. MaXTH32.5 Localized to the Chloroplast and May Be Involved in Regulating Firmness in Banana Fruits

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Plant Materials

4.2. Determination of the Firmness and Other Physiological Indices of Banana Fruits

4.3. Transcriptome Sequencing, Assembly, Functional Annotation, and Heatmap

4.4. Analysis of the XTH Pan-Gene Family in the Musa Genus

4.5. Chromosomal Localization, Promoter Analysis, and Gene Duplication Analysis of the XTH Gene Family in the Musa Genus

4.6. Subcellular Localization Analysis, and Banana Transient Transformation

4.7. Quantitative Real-Time PCR Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| d | Day |

| DEGs | Differentially Expressed Genes |

| EV | Empty Vector |

| GO | Gene Ontology |

| KEGG | Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes |

| OE | Overexpression |

| RT-qPCR | Quantitative Real-Time Polymerase Chain Reaction |

| VS. | versus |

| XTH | Xyloglucan endotransglucosylase/hydrolase |

References

- Mbeguie-A-Mbeguie, D.; Hubert, O.; Baurens, F.C.; Matsumoto, T.; Chillet, M.; Fils-Lycaon, B.; Sidibe-Bocs, S. Expression patterns of cell wall-modifying genes from banana during fruit ripening and in relationship with finger drop. J. Exp. Bot. 2009, 60, 2021–2034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takizawa, A.; Hyodo, H.; Wada, K.; Ishii, T.; Satoh, S. Iwai HRegulatory Specialization of Xyloglucan (XG), Glucuronoarabinoxylan (GAX) in pericarp cell walls during fruit ripening in tomato (Solanum lycopersicum). PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e89871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, H.; Sun, P.; Zhu, W.; Liu, Q.; Zhang, J.; Jia, C.; Sun, J.; Zhu, Z.; Xie, J.; Wang, W.; et al. Exploring the function of MaPHO1 in starch degradation and its protein interactions in postharvest banana fruits. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2024, 209, 112687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miedes, E.; Suslov, D.; Vandenbussche, F.; Kenobi, K.; Ivakov, A.; Van Der Straeten, D.; Lorences, E.P.; Mellerowicz, E.J.; Verbelen, J.P.; Vissenberg, K. Xyloglucan endotransglucosylase/hydrolase (XTH) overexpression affects growth and cell wall mechanics in etiolated Arabidopsis hypocotyls. J. Exp. Bot. 2013, 64, 2481–2497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lian, Q.; Huettel, B.; Walkemeier, B.; Mayjonade, B.; Lopez-Roques, C.; Gil, L.; Roux, F.; Schneeberger, K.; Mercier, R. A pan-genome of 69 Arabidopsis thaliana accessions reveals a conserved genome structure throughout the global species range. Nat. Genet. 2024, 56, 982–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shang, L.; Li, X.; He, H.; Yuan, Q.; Song, Y.; Wei, Z.; Lin, H.; Hu, M.; Zhao, F.; Zhang, C.; et al. A super pan-genomic landscape of rice. Cell Res. 2022, 32, 878–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Emmanuel, J.K.; Mtashobya, L.A.; Mgeni, S.T. Potential contributions of banana druits and residues to multiple applications: An Overview. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2025, 20, 1934578X251320151. [Google Scholar]

- SShipman, E.N.; Yu, J.; Zhou, J.; Albornoz, K.; Beckles, D.M. Can gene editing reduce postharvest waste and loss of fruit, vegetables, and ornamentals? Hortic. Res. 2021, 8, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Yeats, T.H.; Uluisik, S.; Rose, J.K.C.; Seymour, G.B. Fruit Softening: Revisiting the Role of Pectin. Trends Plant Sci. 2018, 23, 302–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.H.; Sun, Q.; Ma, C.N.; Wei, M.M.; Wang, C.K.; Zhao, Y.W.; Wang, W.Y.; Hu, D.G. MdWRKY31-MdNAC7 regulatory network: Orchestrating fruit softening by modulating cell wall-modifying enzyme MdXTH2 in response to ethylene signalling. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2024, 22, 3244–3261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asif, M.; Lakhwani, D.; Pathak, S.; Gupta, P.; Bag, S.K.; Nath, P.; Trivedi, P. Transcriptome analysis of ripe and unripe fruit tissue of banana identifies major metabolic networks involved in fruit ripening process. BMC Plant Biol. 2014, 14, 316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, Z.; Li, T.; Gao, H.; Zhu, H.; Gupta, V.K.; Jiang, Y.; Duan, X. Integrated transcriptomic, proteomic, and metabolomics analysis reveals peel ripening of harvested banana under natural condition. Biomolecules 2019, 9, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belser, C.; Baurens, F.C.; Noel, B.; Martin, G.; Cruaud, C.; Istace, B.; Yahiaoui, N.; Labadie, K.; Hřibová, E.; Doležel, J.; et al. Telomere-to-telomere gapless chromosomes of banana using nanopore sequencing. Commun. Biol. 2021, 4, 1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Miao, H.; Liu, J.; Xu, B.; Yao, X.; Xu, C.; Zhao, S.; Fang, X.; Jia, C.; Wang, J.; et al. Musa balbisiana genome reveals subgenome evolution and functional divergence. Nat. Plants 2019, 5, 810–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belser, C.; Istace, B.; Denis, E.; Dubarry, M.; Baurens, F.C.; Falentin, C.; Genete, M.; Berrabah, W.; Chèvre, A.M.; Delourme, R.; et al. Chromosome-scale assemblies of plant genomes using nanopore long reads and optical maps. Nat. Plants 2018, 4, 879–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Wang, J.; Fu, Y.; Jing, Y.; Huang, B.; Chen, Y.; Wang, Q.; Wang, X.B.; Meng, C.; Yang, Q.; et al. The Musa troglodytarum L. genome provides insights into the mechanism of non-climacteric behaviour and enrichment of carotenoids. BMC Biol. 2022, 20, 186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Y.; Zhan, H.; Chen, H.; Li, X.; Chen, C.; Liu, H.; Chen, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Xiao, Y.; Liu, J.; et al. Genome-wide identification of XTH gene family in Musa acuminata and response analyses of MaXTHs and xyloglucan to low temperature. Physiol. Plant. 2024, 176, e14231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peroni-Okita, F.H.G.; Simão, R.A.; Cardoso, M.B.; Soares, C.A.; Lajolo, F.M.; Cordenunsi, B.R. In vivo degradation of banana starch: Structural characterization of the degradation process. Carbohydr. Polym. 2010, 81, 291–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Zhu, L.; Lin, Z.; Wei, W.; Yang, Y.; Si, J.; Shan, W.; Chen, J.; Lu, W.; Kuang, J.; et al. Banana MabZIP21 positively regulates MaBAM4, MaBAM7 and MaAMY3 expression to mediate starch degradation during postharvest ripening. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2001, 211, 112835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, H.; Sun, P.; Li, Q.; Jia, C.; Liu, J.; He, W.; Jin, Z.; Xu, B. Soluble starch synthase III-1 in amylopectin metabolism of banana fruit: Characterization, expression, enzyme activity, and functional analyses. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 96979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, Y.Y.; Kuang, J.F.; Qi, X.N.; Ye, Y.J.; Wu, Z.X.; Chen, J.Y.; Lu, W.J. A comprehensive investigation of starch degradation process and identification of a transcriptional activator MabHLH6 during banana fruit ripening. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2018, 16, 151–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C.J.; Sun, W.; Li, X.C.; Zheng, L.S.; Wei, W.; Yang, Y.Y.; Guo, Y.F.; Bouzayen, M.; Chen, J.Y.; Lu, W.J. Phosphorylation of transcription factor bZIP21 by MAP kinase MPK6-3 enhances banana fruit ripening. Plant Physiol. 2021, 185, 3–15. [Google Scholar]

- Zhai, Z.; Feng, C.; Wang, Y.; Sun, Y.; Peng, X.; Xiao, Y.; Zhang, X.; Zhou, X.; Jiao, J.; Wang, W.; et al. Genome-wide identification of the Xyloglucan endotransglucosylase/Hydrolase (XTH) and Polygalacturonase (PG) genes and vharacterization of their role in fruit softening of sweet cherry. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 12331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Y.; Li, B.; Jia, H.; Yang, X.; Sun, Y.; Shou, J.; Jiang, G.; Shi, Y.; Chen, K. Comparative analysis of fruit firmness and genes associated with cell wall metabolisms in three cultivated strawberries during ripening and postharvest. Food Qual. Saf. 2023, 7, fyad020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Wan, H.; Zhao, H.; Dai, X.; Wu, W.; Liu, J.; Xu, J.; Yang, R.; Xu, B.; Zeng, C. Identification and expression analysis of the Xyloglucan transglycosylase/hydrolase (XTH) gene family under abiotic stress in oilseed (Brassica napus L.). BMC Plant Biol. 2024, 24, 400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.Z.; He, P.W.; Xu, X.M.; Lü, Z.F.; Cui, P.; George, M.S.; Lu, G.Q. Genome-wide identification and expression analysis of the Xyloglucan Endotransglucosylase/Hydrolase gene family in sweet potato [Ipomoea batatas (L.) Lam]. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Zong, Y.; Tu, Z.; Yang, L.; Li, W.; Cui, Z.; Hao, Z.; Li, H. Genome-wide identification of XTH genes in Liriodendron chinense and functional characterization of LcXTH21. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 1014339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Li, H.; Yin, C.; Wang, X.; Jiang, Q.; Zhang, R.; Ge, F.; Chen, Y.; Yang, L. Genome-wide identification and characterization of Xyloglucan Endotransglycosylase/Hydrolase in ananas comosus during development. Genes 2019, 10, 537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, D.; Lin, L.; Liu, X.; Wangzha, M.L.; Pang, X.; Feng, L.; Wan, B.; Wu, G.Z.; Yu, J.; Rochaix, J.D. Characterization of a tomato chlh mis-sense mutant reveals a new function of ChlH in fruit ripening. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2025, 23, 911–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Feng, Y.; Han, Z.; Song, Y.; Guo, J.; Yu, J.; Wang, Z.; Wang, H.; Gao, H.; Yang, Y. Functional analysis of the xyloglucan endotransglycosylase/hydrolase gene MdXTH2 in apple fruit firmness formation. J. Integr. Agric. 2025, 24, 3418–3434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Chen, H.; Zhang, Y.; Thomas, H.R.; Xia, R. TBtools: An integrative toolkit developed for interactive analyses of big biological data. Mol. Plant 2020, 13, 1194–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yokoyama, R.; Nishitani, K. A comprehensive expression analysis of all members of a gene family encoding cell-wall enzymes allowed us to predict cis-Regulatory regions involved in cell-wall construction in specific organs of Arabidopsis. Plant Cell Physiol. 2001, 42, 1025–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aron, M.B.; Yu, B.; Hu, L.; He, J.; Lanczycki, C.J.; Lu, S.; Chitsaz, F.; Derbyshire, M.K.; Geer, R.C.; Gonzales, N.R. CDD/SPARCLE: Functional classification of proteins via subfamily domain architectures. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017, 45, D200–D203. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, S.; Stecher, G.; Tamura, K. MEGA7: Molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 7.0 for bigger datasets. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2016, 33, 1870–1874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, W.; Yang, Y.Y.; Lakshmanan, P.; Kuang, J.F.; Lu, W.J.; Pang, X.Q.; Chen, J.Y.; Shan, W. Proteasomal degradation of MaMYB60 mediated by the E3 ligase MaBAH1 causes high temperature-induced repression of chlorophyll catabolism and green ripening in banana. Plant Cell 2023, 35, 1408–1428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yang, F.; Wan, K.; Kang, X.; Zhong, W.; Lv, J.; Lin, Y.; Wang, J.; Lai, Z.; Liao, B.; Lin, Y. Transcriptomics and Gene Family Identification of Cell Wall-Related Differentially Expressed Genes Reveal MaXTH32.5 Involved in Fruit Firmness During Banana Ripening. Plants 2025, 14, 3810. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14243810

Yang F, Wan K, Kang X, Zhong W, Lv J, Lin Y, Wang J, Lai Z, Liao B, Lin Y. Transcriptomics and Gene Family Identification of Cell Wall-Related Differentially Expressed Genes Reveal MaXTH32.5 Involved in Fruit Firmness During Banana Ripening. Plants. 2025; 14(24):3810. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14243810

Chicago/Turabian StyleYang, Fengjie, Kui Wan, Xiaoli Kang, Wanting Zhong, Jiasi Lv, Yiyao Lin, Jialing Wang, Zhongxiong Lai, Bin Liao, and Yuling Lin. 2025. "Transcriptomics and Gene Family Identification of Cell Wall-Related Differentially Expressed Genes Reveal MaXTH32.5 Involved in Fruit Firmness During Banana Ripening" Plants 14, no. 24: 3810. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14243810

APA StyleYang, F., Wan, K., Kang, X., Zhong, W., Lv, J., Lin, Y., Wang, J., Lai, Z., Liao, B., & Lin, Y. (2025). Transcriptomics and Gene Family Identification of Cell Wall-Related Differentially Expressed Genes Reveal MaXTH32.5 Involved in Fruit Firmness During Banana Ripening. Plants, 14(24), 3810. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14243810