Balancing Osmotic Protection and Oxidative Stress: Physiological and Biochemical Responses of Pot Marigold (Calendula officinalis L.) Plants to Water Stress

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Effects of Drought on Vegetative Structures

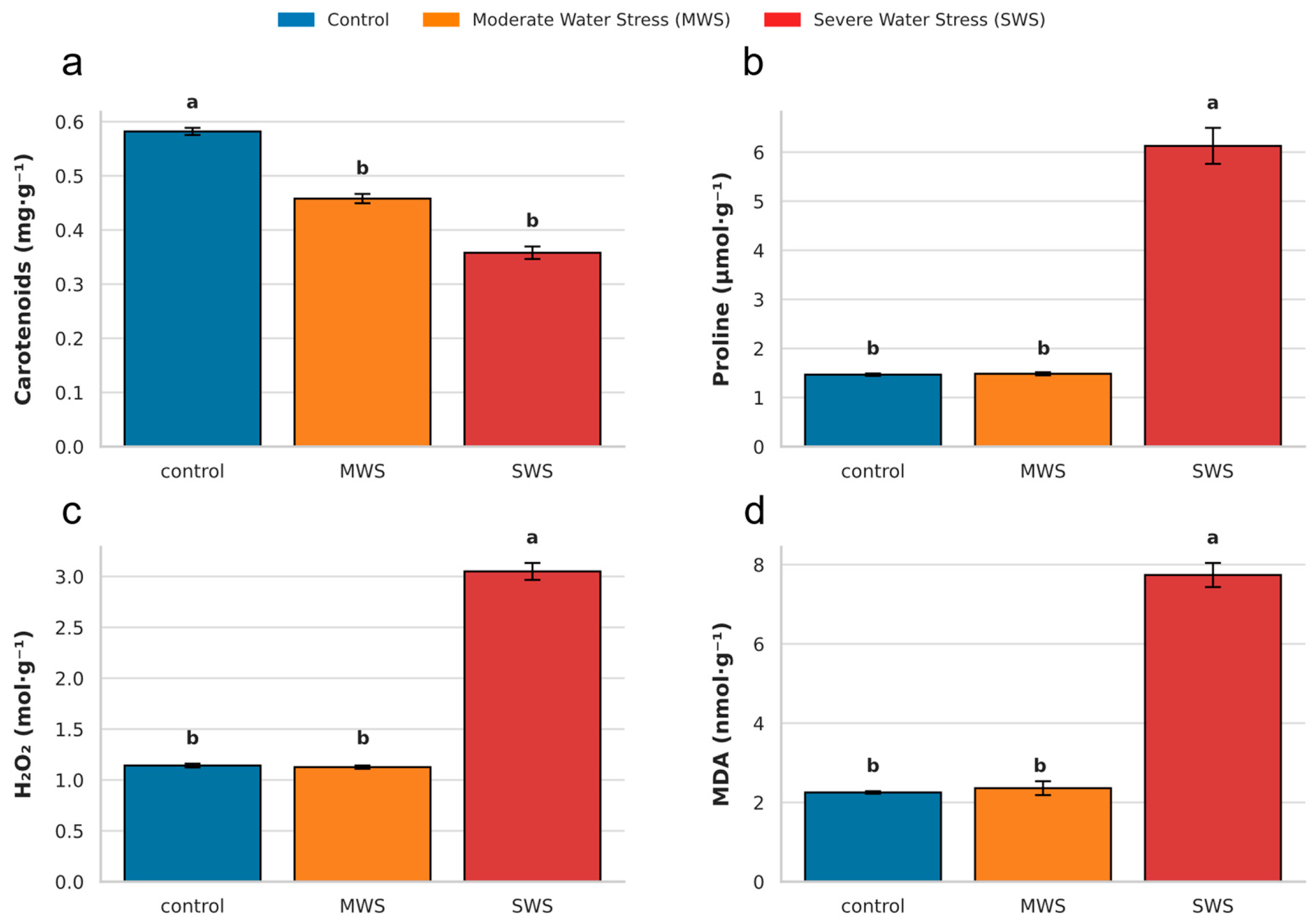

2.2. Activities of Non-Enzymatic and Stress-Related Metabolites

2.3. Enzymatic Activities in Response to Drought

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Plant Growth and Water Treatments

4.2. Activities of Non-Enzymatic and Stress-Related Metabolites

4.3. Antioxidative Enzyme Activities

4.4. Statistical Analyses

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yu, Y.; Wang, L.; Chang, C.; Liu, Z.; Lv, A.; Li, T. Intensified Drought Threatens Future Food Security in Major Food-Producing Countries. Atmosphere 2024, 16, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global Drought Outlook. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/global-drought-outlook_d492583a-en.html (accessed on 23 June 2025).

- Brás, T.A.; Seixas, J.; Carvalhais, N.; Jägermeyr, J. Severity of drought and heatwave crop losses tripled over the last five decades in Europe. Environ. Res. Lett. 2021, 16, 65012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haghpanah, M.; Hashemipetroudi, S.; Arzani, A.; Araniti, F. Drought Tolerance in Plants: Physiological and Molecular Responses. Plants 2024, 13, 2962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, K.; Chen, Y.; Hou, J.; Yan, F.; Liu, F. ABA-mediated stomatal response modulates the effects of drought, salinity and combined stress on tomato plants grown under elevated CO2. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2024, 223, 105797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bharath, P.; Gahir, S.; Raghavendra, A.S. Abscisic Acid-Induced Stomatal Closure: An Important Component of Plant Defense Against Abiotic and Biotic Stress. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 615114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Driesen, E.; De Proft, M.; Saeys, W. Drought stress triggers alterations of adaxial and abaxial stomatal development in basil leaves increasing water-use efficiency. Hortic. Res. 2023, 10, uhad075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alongi, F.; Petek-Petrik, A.; Mukarram, M.; Torun, H.; Schuldt, B.; Petrík, P. Somatic drought stress memory affects leaf morpho-physiological traits of plants via epigenetic mechanisms and phytohormonal signalling. Plant Gene 2025, 42, 100509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keya, S.S.; Islam, M.R.; Pham, H.; Rahman, M.A.; Bulle, M.; Patwary, A.; Kanika, M.M.A.R.; Hemel, F.H.; Ghosh, T.K.; Huda, N.; et al. Thirsty, soaked, and thriving: Maize morpho-physiological and biochemical responses to sequential drought, waterlogging, and re-drying. Plant Stress 2025, 15, 100722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munné-Bosch, S.; Alegre, L. Die and let live: Leaf senescence contributes to plant survival under drought stress. Funct. Plant Biol. 2004, 31, 203–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.S.; Kidokoro, S.; Yamaguchi-Shinozaki, K.; Shinozaki, K. Regulatory networks in plant responses to drought and cold stress. Plant Physiol. 2024, 195, 170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Duan, G.; Li, C.; Liu, L.; Han, G.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, C. The Crosstalks Between Jasmonic Acid and Other Plant Hormone Signaling Highlight the Involvement of Jasmonic Acid as a Core Component in Plant Response to Biotic and Abiotic Stresses. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 458580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wani, S.H.; Singh, N.B.; Haribhushan, A.; Mir, J.I. Compatible Solute Engineering in Plants for Abiotic Stress Tolerance—Role of Glycine Betaine. Curr. Genomics 2013, 14, 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, X.; Lu, M.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Liu, Z.; Chen, S. Response Mechanism of Plants to Drought Stress. Horticulturae 2021, 7, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajput, V.D.; Harish; Singh, R.K.; Verma, K.K.; Sharma, L.; Quiroz-Figueroa, F.R.; Meena, M.; Gour, V.S.; Minkina, T.; Sushkova, S.; et al. Recent Developments in Enzymatic Antioxidant Defence Mechanism in Plants with Special Reference to Abiotic Stress. Biology 2021, 10, 267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mittler, R. Oxidative stress, antioxidants and stress tolerance. Trends Plant Sci. 2002, 7, 405–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, S.S.; Tuteja, N. Reactive oxygen species and antioxidant machinery in abiotic stress tolerance in crop plants. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2010, 48, 909–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zandi, P.; Schnug, E. Reactive Oxygen Species, Antioxidant Responses and Implications from a Microbial Modulation Perspective. Biology 2022, 11, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasanuzzaman, M.; Fujita, M. Plant Responses and Tolerance to Salt Stress: Physiological and Molecular Interventions. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 4810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, P.; Abdelbacki, A.M.M.; Albaqami, M.; Jan, R.; Kim, K.M. Proline Promotes Drought Tolerance in Maize. Biology 2025, 14, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, N.; Pal, M.; Singh, A.; SaiRam, R.K.; Srivastava, G.C. Exogenous proline alleviates oxidative stress and increase vase life in rose (Rosa hybrida L. ‘Grand Gala’). Sci. Hortic. 2010, 127, 79–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzman, M.R.; Marques, I. Divergent Impacts of Moderate and Severe Drought on the Antioxidant Response of Calendula officinalis L. Leaves and Flowers. Biol. Life Sci. Forum 2023, 27, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzman, M.R.; Rojas-Ruilova, X.; Gomes-Domingues, C.; Marques, I. Using Saline Water for Sustainable Floriculture: Identifying Physiological Thresholds and Floral Performance in Eight Asteraceae Species. Agronomy 2025, 15, 1802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kibria, M.G.; Hossain, M.; Murata, Y.; Hoque, M.A. Antioxidant Defense Mechanisms of Salinity Tolerance in Rice Genotypes. Rice Sci. 2017, 24, 155–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szabados, L.; Savouré, A. Proline: A multifunctional amino acid. Trends Plant Sci. 2010, 15, 89–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Du, G.; Li, X.; Zhang, C.; Guo, J. A major locus controlling malondialdehyde content under water stress is associated with Fusarium crown rot resistance in wheat. Mol. Genet. Genomics 2015, 290, 1955–1962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahane, K.; Kshirsagar, M.; Tambe, S.; Jain, D.; Rout, S.; Ferreira, M.K.M.; Mali, S.; Amin, P.; Srivastav, P.P.; Cruz, J.; et al. An Updated Review on the Multifaceted Therapeutic Potential of Calendula officinalis L. Pharmaceuticals 2023, 16, 611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ejiohuo, O.; Folami, S.; Maigoro, A.Y. Calendula in modern medicine: Advancements in wound healing and drug delivery applications. Eur. J. Med. Chem. Rep. 2024, 12, 100199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salama, A.B.; Sabry, R.M. Production Potential of Pot Marigold (Calendula officinalis) as a Dual-Purpose Crop. Sarhad J. Agric. 2023, 39, 298–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, D.; Ferreira, M.S.; Sousa-Lobo, J.M.; Cruz, M.T.; Almeida, I.F. Anti-Inflammatory Activity of Calendula officinalis L. Flower Extract. Cosmetics 2021, 8, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nucia, A.; Ociepa, T.; Król, B.; Okoń, S. Exploring the phenotypic and molecular diversity of Calendula officinalis L. cultivars featuring varying flower types. PeerJ 2025, 13, e18814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baciu, A.D.; Pamfil, D.; Mihalte, L.; Sestras, A.F.; Sestras, R.E. Phenotypic variation and genetic diversity of Calendula officinalis (L.). Bulg. J. Agric. Sci. 2013, 19, 143–151. [Google Scholar]

- Drivers of Change in Calendula officinalis Flower Extract Market 2025–2033. Available online: https://www.datainsightsmarket.com/reports/calendula-officinalis-flower-extract-1084574# (accessed on 23 June 2025).

- VMR. 2023 Calendula officinalis Flower Extract Market Size, Demand, Insights & Trends & Forecast 2033. Available online: https://www.verifiedmarketreports.com/product/calendula-officinalis-flower-extract-market/?utm_source=chatgpt.com/ (accessed on 23 June 2025).

- Eghlima, G.; Mohammadi, M.; Ranjabr, M.E.; Nezamdoost, D.; Mammadov, A. Foliar application of nano-silicon enhances drought tolerance rate of pot marigold (Calendula officinalis L.) by regulation of abscisic acid signaling. BMC Plant Biol. 2024, 24, 1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gholinezhad, E. Impact of drought stress and stress modifiers on water use efficiency, membrane lipidation indices, and water relationship indices of pot marigold (Calendula officinalis L.). Rev. Bras. Bot. 2020, 43, 747–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nour, M.M.; Aljabi, H.R.; AL-Huqail, A.A.; Horneburg, B.; Mohammed, A.E.; Alotaibi, M.O. Drought responses and adaptation in plants differing in life-form. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2024, 12, 1452427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Jia, W.; Zheng, J.; Ma, L.; Duan, Q.; Du, W.; Cui, G.; Wang, X.; Wang, J. Application of Morphological and Physiological Markers for Study of Drought Tolerance in Lilium Varieties. Horticulturae 2022, 8, 786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hessini, K.; Wasli, H.; Al-Yasi, H.M.; Ali, E.F.; Issa, A.A.; Hassan, F.A.S.; Siddique, K.H.M.; Toscano, S.; Franzoni, G.; Álvarez, S.; et al. Graded Moisture Deficit Effect on Secondary Metabolites, Antioxidant, and Inhibitory Enzyme Activities in Leaf Extracts of Rosa damascena Mill. var. trigentipetala. Horticulturae 2022, 8, 177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toscano, S.; Ferrante, A.; Romano, D.; Tribulato, A. Interactive effects of drought and saline aerosol stress on morphological and physiological characteristics of two ornamental shrub species. Horticulturae 2021, 7, 517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Gautam, R.D.; Kumar, A.; Singh, S.; Singh, S. Understanding the Effect of Different Abiotic Stresses on Wild Marigold (Tagetes minuta L.) and Role of Breeding Strategies for Developing Tolerant Lines. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 12, 3332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jia, X.; Feng, H.; Bu, Y.; Ji, N.; Lyu, Y.; Zhao, S. Comparative Transcriptome and Weighted Gene Co-expression Network Analysis Identify Key Transcription Factors of Rosa chinensis ‘Old Blush’ After Exposure to a Gradual Drought Stress Followed by Recovery. Front. Genet. 2021, 12, 690264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, T.; He, Q.; Wang, C.; Li, Z.; Sun, S.; Yang, X.; Yang, X.; Deng, Y.; Hou, C. The Expression Profile of Genes Related to Carotenoid Biosynthesis in Pepper Under Abiotic Stress Reveals a Positive Correlation with Plant Tolerance. Life 2024, 14, 1659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, T.; Rao, S.; Zhou, X.; Li, L. Plant carotenoids: Recent advances and future perspectives. Mol. Hortic. 2022, 2, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, L.; Abbey, L.; MacDonald, M. Changes in Endogenous Carotenoids, Flavonoids, and Phenolics of Drought-Stressed Broccoli Seedlings After Ascorbic Acid Preconditioning. Plants 2024, 13, 3513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toscano, S.; Romano, D. Morphological, physiological, and biochemical responses of Zinnnia to drought stress. Horticulturae 2021, 7, 362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.N.; Jiao, T.Q.; Li, J.; Wang, A.Y.; Li, Y.X.; Wu, S.J.; Du, L.Q.; Dijkwel, P.P.; Zhu, J.B. Drought-induced increase in catalase activity improves cotton yield when grown under water-limiting field conditions. J. Agron. Crop Sci. 2022, 208, 853–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luna, C.M.; Pastori, G.M.; Driscoll, S.; Groten, K.; Bernard, S.; Foyer, C.H. Drought controls on H2O2 accumulation, catalase (CAT) activity and CAT gene expression in wheat. J. Exp. Bot. 2005, 56, 417–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Doorn, W.G.; Ketsa, S. Cross reactivity between ascorbate peroxidase and phenol (guaiacol) peroxidase. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2014, 95, 64–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Passardi, F.; Penel, C.; Dunand, C. Performing the paradoxical: How plant peroxidases modify the cell wall. Trends Plant Sci. 2004, 9, 534–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ying, Z.; Fu, S.; Yang, Y. Signaling and scavenging: Unraveling the complex network of antioxidant enzyme regulation in plant cold adaptation. Plant Stress 2025, 16, 100833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lone, M.L.; Altaf, F.; Tantray, W.W.; Farooq, S.; Haq, A.u.; Parveen, S.; Tahir, I. Insights into the biochemical and molecular aspects of flower senescence in Calendula officinalis L. Plant Growth Regul. 2025, 105, 1323–1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsayed, A.I.; El-Hamahmy, M.A.M.; Rafudeen, M.S.; Mohamed, A.H.; Omar, A.A. The impact of drought stress on antioxidant responses and accumulation of flavonolignans in milk thistle (Silybum marianum (L.) gaertn). Plants 2019, 8, 611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, S.; Srivastava, M. Morphological Changes and Antioxidant Activity of Stevia rebaudiana under Water Stress. Am. J. Plant Sci. 2014, 05, 3417–3422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, A.; Liu, M.; Gu, W.; Chen, Z.; Gu, Y.; Pei, L.; Tian, R. Effect of drought on photosynthesis, total antioxidant capacity, bioactive component accumulation, and the transcriptome of Atractylodes lancea. BMC Plant Biol. 2021, 21, 293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghadyeh Zarrinabadi, I.; Razmjoo, J.; Abdali Mashhadi, A.; Karim mojeni, H.; Boroomand, A. Physiological response and productivity of pot marigold (Calendula officinalis) genotypes under water deficit. Ind. Crops Prod. 2019, 139, 111488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavassoli, A.; Tavakol, E.; Heidari, B.; Afsharifar, A. Drought stress effects on pot marigold (Calendula officinalis L.) revealed by REML and BLUEs analysis. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 30613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavallali, V.; Rahemi, M.; Eshghi, S.; Kholdebarin, B.; Ramezanian, A. Zinc alleviates salt stress and increases antioxidant enzyme activity in the leaves of pistachio (Pistacia vera L. ’Badami’) seedlings. Turkish J. Agric. For. 2010, 34, 349–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allam, O.M.; Kandeel, A.M.; Hassan, S.E.; Abdelhamid, A.N. Effects of melatonin and bacterial bio-stimulants on Calendula officinalis under salinity stress. J. Saudi Soc. Agric. Sci. 2025, 24, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Yuan, Y.; Xu, S.; Li, Z.; Cui, Z.; Zhan, L.; Zhang, D.; Nie, J.; Sun, L.; Dai, J.; et al. Shading-induced canopy cooling alleviates waterlogging damage during flowering by disrupting heat synergism in field-grown cotton. Field Crop. Res. 2025, 334, 110166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozano-Castellanos, L.F.; Pennisi, G.; Navas-Gracia, L.M.; Orsini, F.; Sánchez-Hernández, E.; Martín-Ramos, P.; Correa-Guimaraes, A. Physiological and Phytochemical Responses of Calendula officinalis L. to End-of-Day Red/Far-Red and Green Light. Biology 2025, 14, 935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzman, M.R.; Marques, I. Effect of Varied Salinity on Marigold Flowers: Reduced Size and Quantity Despite Enhanced Antioxidant Activity. Agronomy 2023, 13, 3076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chrysargyris, A.; Tzionis, A.; Xylia, P.; Tzortzakis, N. Effects of salinity on tagetes growth, physiology, and shelf life of edible flowers stored in passive modified atmosphere packaging or treated with ethanol. Front. Plant Sci. 2018, 871, 1765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khedr, A.H.A.; Abbas, M.A.; Abdel Wahid, A.A.; Quick, W.P.; Abogadallah, G.M. Proline induces the expression of salt-stress-responsive proteins and may improve the adaptation of Pancratium maritimum L. to salt-stress. J. Exp. Bot. 2003, 54, 2553–2562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Azevedo Neto, A.D.; Prisco, J.T.; Enéas-Filho, J.; De Abreu, C.E.B.; Gomes-Filho, E. Effect of salt stress on antioxidative enzymes and lipid peroxidation in leaves and roots of salt-tolerant and salt-sensitive maize genotypes. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2006, 56, 87–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Treatments | Number | Length | Width |  |

| Control | 15.7 ± 3.8 a (11.7–20.0) | 7.5 ± 0.9 a (6.0–8.3) | 2.41 ± 0.5 a (1.8–3.0) | |

| MWS | 10.5 ± 4.2 a,b (4.0–15.0) | 4.9 ± 2.8 b (0.9–6.8) | 1.49 ± 0.91 a (0.24–2.31) | |

| SWS | 7.7 ± 2.6 b (4.3–10.7) | 4.3 ± 1.9 b (1.8–7.1) | 1.51 ± 0.59 a (0.91–2.42) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ribeiro, D.; Guzmán, M.R.; Caperta, A.D.; Marques, I. Balancing Osmotic Protection and Oxidative Stress: Physiological and Biochemical Responses of Pot Marigold (Calendula officinalis L.) Plants to Water Stress. Plants 2025, 14, 3809. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14243809

Ribeiro D, Guzmán MR, Caperta AD, Marques I. Balancing Osmotic Protection and Oxidative Stress: Physiological and Biochemical Responses of Pot Marigold (Calendula officinalis L.) Plants to Water Stress. Plants. 2025; 14(24):3809. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14243809

Chicago/Turabian StyleRibeiro, Diana, Maria Rita Guzmán, Ana D. Caperta, and Isabel Marques. 2025. "Balancing Osmotic Protection and Oxidative Stress: Physiological and Biochemical Responses of Pot Marigold (Calendula officinalis L.) Plants to Water Stress" Plants 14, no. 24: 3809. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14243809

APA StyleRibeiro, D., Guzmán, M. R., Caperta, A. D., & Marques, I. (2025). Balancing Osmotic Protection and Oxidative Stress: Physiological and Biochemical Responses of Pot Marigold (Calendula officinalis L.) Plants to Water Stress. Plants, 14(24), 3809. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14243809