Genome-Wide Identification of β-D-Xylosidase Gene Family in Potato and Functional Analysis Under Alkaline Stress

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Identification and Characterization of StBXLs

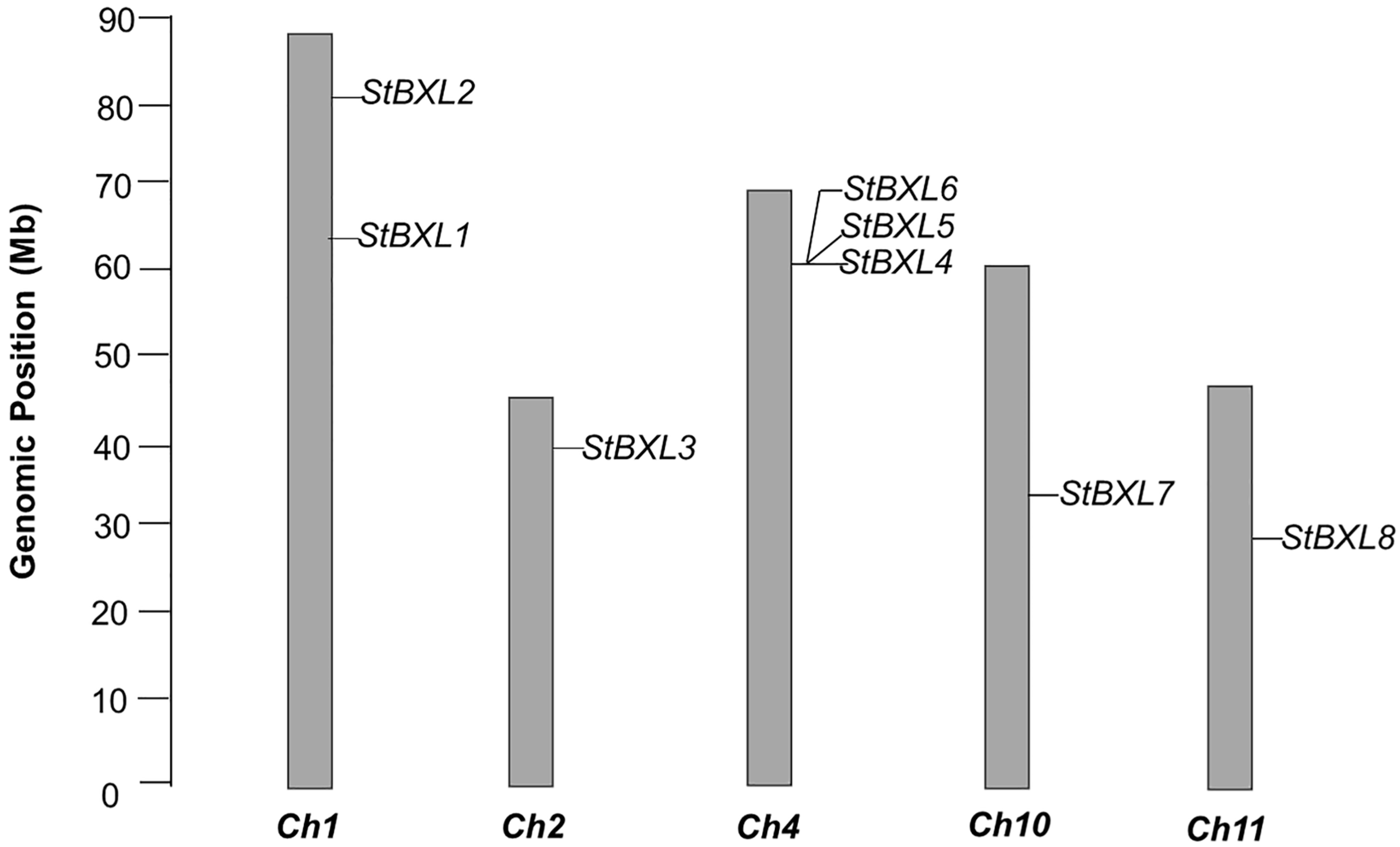

2.2. Chromosome Localization and Duplication of StBXLs

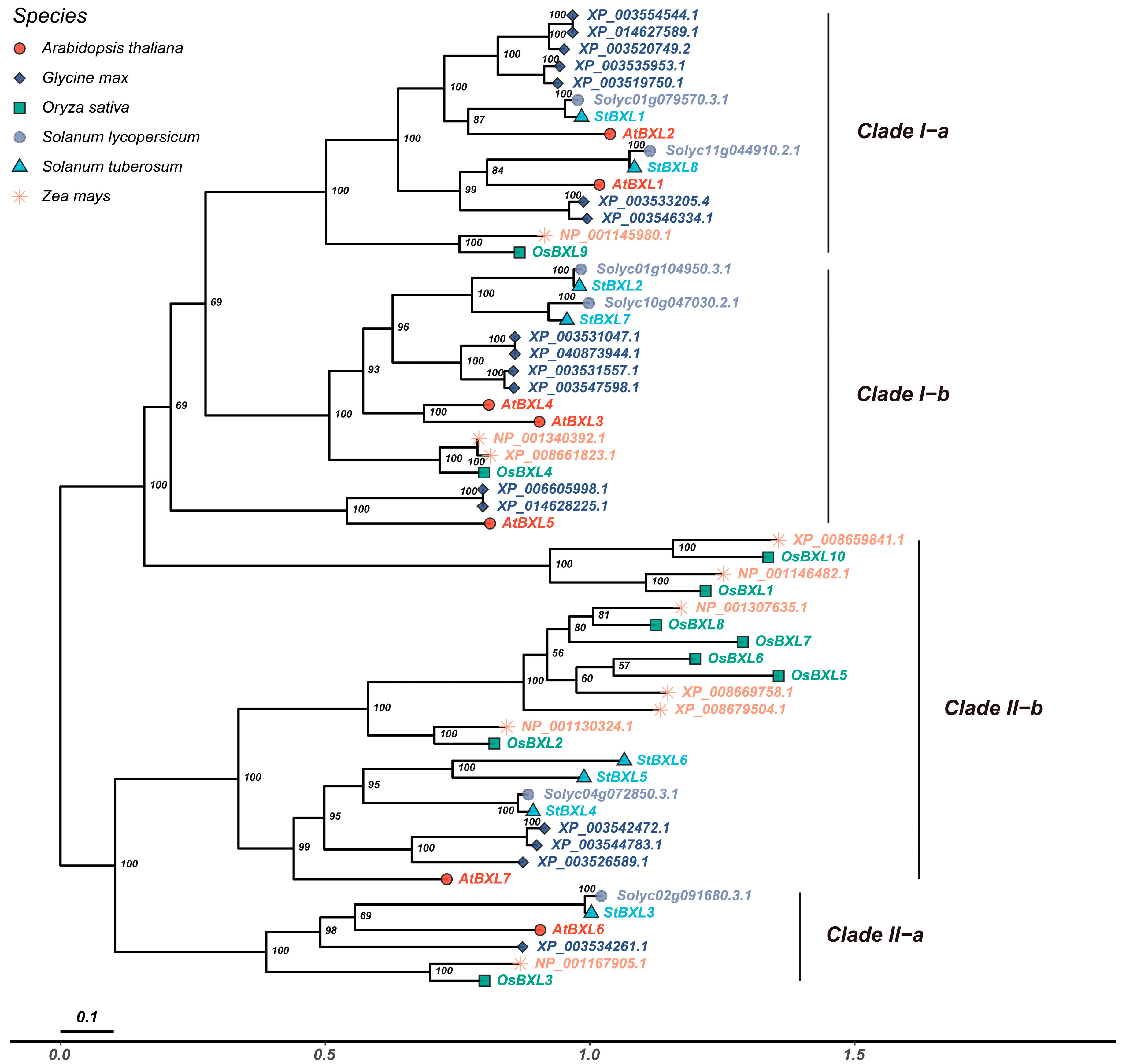

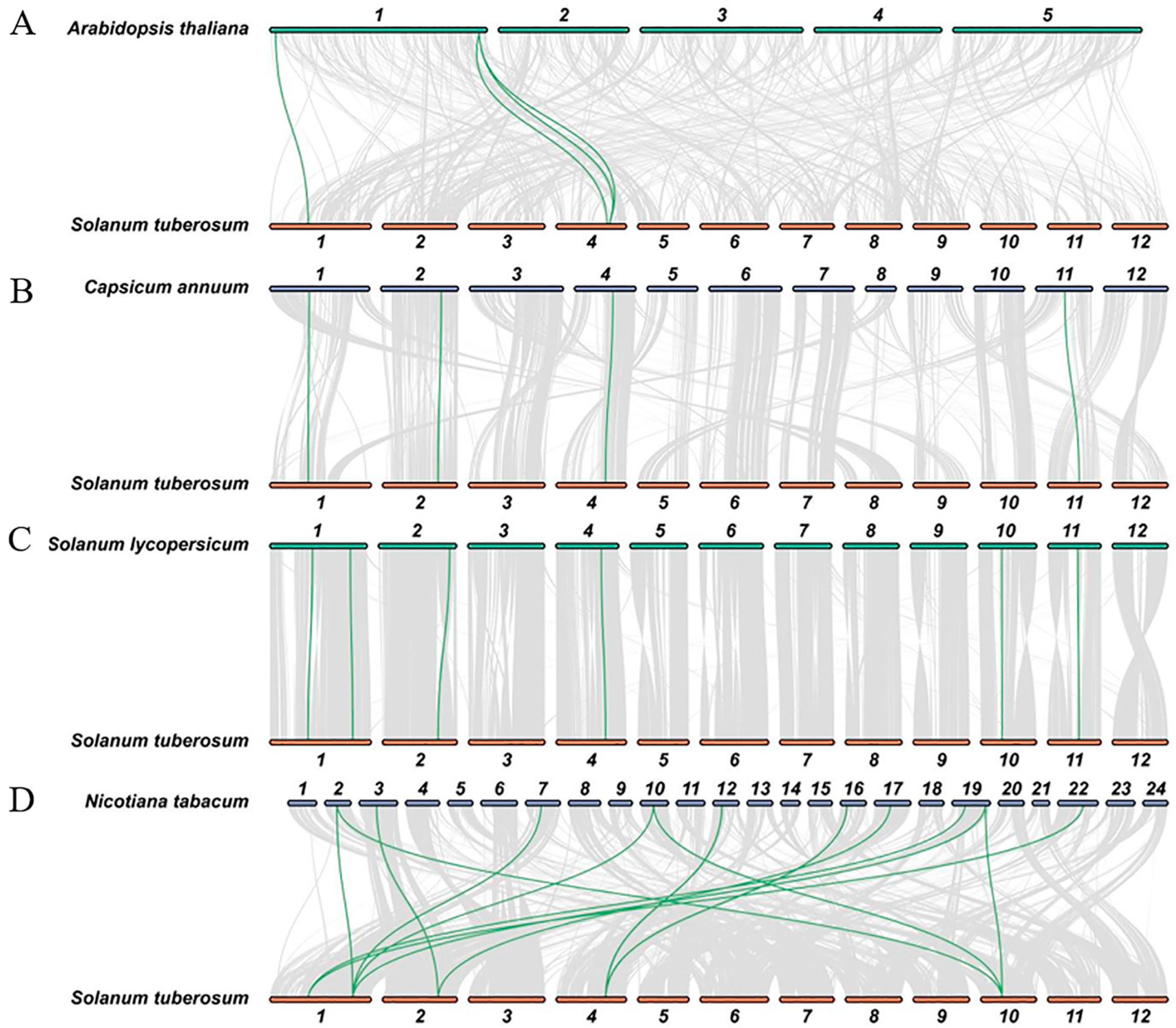

2.3. Phylogenetic and Synteny Analysis of BXL in Different Plant Species

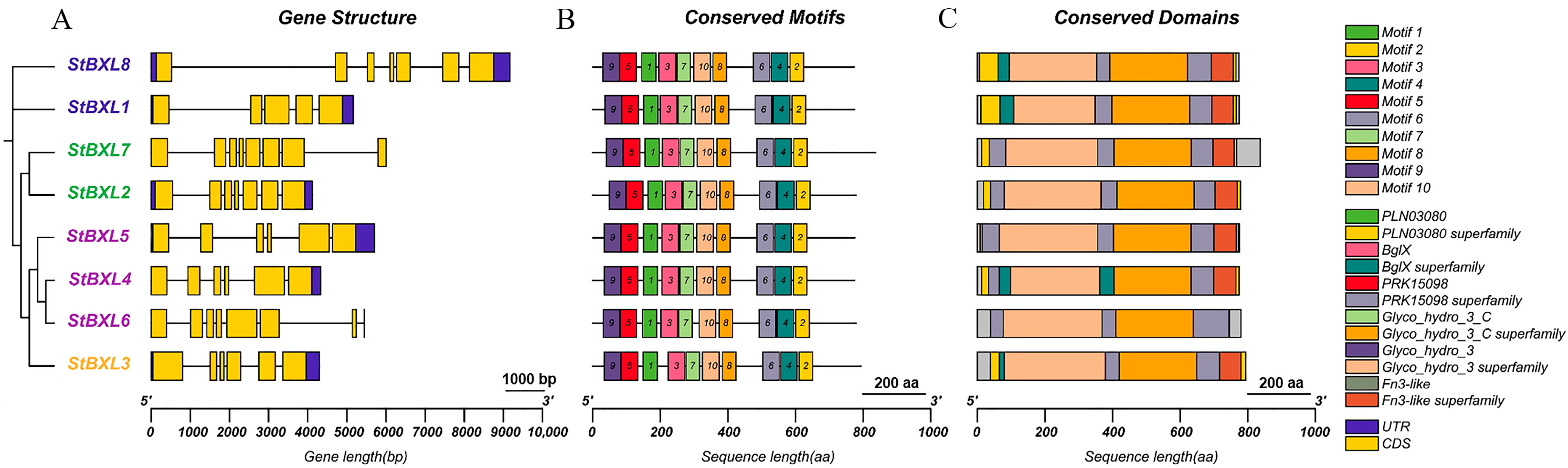

2.4. Gene Structure, Conserved Domain, and Motif Analyses of StBXL

2.5. Analysis of Cis-Elements in StBXL Promoters

2.6. Protein Interaction Networks of StBXL Proteins

2.7. Expression Patterns of StBXL Genes in Different Tissues and Under Abiotic Stresses

2.8. StBXL Expression Patterns Under Alkaline Stress

2.9. Overexpression of StBXL4 Reduces Potato’s Resistance to Alkaline Stress

3. Discussion

4. Conclusions

5. Materials and Methods

5.1. Genome-Wide Identification of StBXL Genes in Potato

5.2. StBXL Sequence Analysis and Characterization

5.3. Prediction of Cis-Elements and Protein Interaction Networks of StBXL

5.4. Phylogenetic Tree Construction and Gene Duplication and Synteny Analysis

- Arabidopsis (https://www.arabidopsis.org/, accessed on 20 May 2025);

- Tomato (https://solgenomics.net/, accessed on 20 May 2025);

- Maize (https://plants.ensembl.org/Zea_mays/Info/Index, accessed on 20 May 2025);

- Soybean (https://plants.ensembl.org/Glycine_max/Info/Index, accessed on 20 May 2025);

- Rice (https://rice.uga.edu/pub/data/Eukaryotic_Projects/o_sativa/, accessed on 20 May 2025);

- Pepper and tobacco (http://plants.ensembl.org/info/data/ftp/index.html, accessed on 20 May 2025).

5.5. RNA-Seq Data Source and Expression Pattern Analysis of StBXL Genes

5.6. Genetic Transformation of Potato and Identification of Transgenic Plants

5.7. Alkali Stress Treatment and Phenotypic Identification of Potato Seedlings

5.8. Data Analysis

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Weidenhamer, J.D.; Cipollini, D.; Morris, K.; Gurusinghe, S.; Weston, L.A. Ecological realism and rigor in the study of plant-plant allelopathic interactions. Plant Soil 2023, 489, 1–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, P.; Ramegowda, V.; Senthil-Kumar, M. Shared and unique responses of plants to multiple individual stresses and stress combinations: Physiological and molecular mechanisms. Front. Plant Sci. 2015, 6, 723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, J.X.; He, M.; Hou, Q.Q.; Zou, L.; Yang, Y.; Wei, Y.; Chen, X. Cell wall associated immunity in plants. Stress Biol. 2021, 1, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shtein, I.; Bar-On, B.; Popper, Z.A. Plant and algal structure: From cell walls to biomechanical function. Physiol. Plant. 2018, 164, 56–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keegstra, K. Plant cell walls. Physiol. Plant. 2010, 154, 483–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cleemput, G.; Hessing, M.; Van, O.M.; Deconynck, M.; Delcour, J.A. Purification and characterization of a β-D-xylosidase and an endo-xylanase from wheat flour. Plant Physiol. 1997, 113, 377–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Zhang, R.; Zhou, J.P.; Huang, Z. Structures, biochemical characteristics, and functions of β-xylosidases. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2023, 71, 7961–7976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pontonio, E.; Mahony, J.; Di, C.R.; Lugli, G.A.; O’Callaghan, A.; De Angelis, M.; Ventura, M.; Gobbetti, M.; van Sinderen, D. Cloning, expression and characterization of a β-D-xylosidase from Lactobacillus rossiae DSM 15814(T). Microb. Cell Fact. 2016, 15, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knob, A.; Terrasan, C.R.F.; Carmona, E.C. β-xylosidases from filamentous fungi: An overview. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2010, 26, 389–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minic, Z.; Rihouey, C.; Do, C.T.; Lerouge, P.; Jouanin, L. Purification and characterization of enzymes exhibiting beta-D-xylosidase activities in stem tissues of Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2004, 135, 867–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goujon, T.; Minic, Z.; El Amrani, A.; Lerouxel, O.; Aletti, E.; Lapierre, C.; Joseleau, J.P.; Jouanin, L. AtBXL1, a novel higher plant (Arabidopsis thaliana) putative beta-xylosidase gene, is involved in secondary cell wall metabolism and plant development. Plant J. 2003, 33, 677–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.Y.; Qu, C.P.; Chang, R.H.; Suo, J.; Yu, J.; Sun, X.; Liu, G.; Xu, Z. Genome-wide identification of BXL genes in Populus trichocarpa and their expression under different nitrogen treatments. 3 Biotech 2020, 10, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, R.C.; Hrmova, M.; Burton, R.A.; Lahnstein, J.; Fincher, G.B. Bifunctional family 3 glycoside hydrolases from barley with α-l-arabinofuranosidase and β-d xylosidase activity characterization, primary structures, and cooh terminal processing. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 5377–5387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Y.; Lai, B.; Hu, W.; You, M.; Wang, L.; Su, T. Genome-Wide Identification of the BXL Gene Family in Soybean and Expression Analysis Under Salt Stress. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 9534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, T.; Gerday, C.; Feller, G. Xylanases, xylanase families and extremophilic xylanases. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2005, 29, 3–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bauer, K.; Nayem, S.; Lehmann, M.; Wenig, M.; Shu, L.; Ranf, S.; Geigenberger, P.; Vlotr, A. β-D-XYLOSIDASE 4 modulates systemic immune signaling in Arabidopsis thaliana. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 13, 1096800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Itai, A.; Yoshida, K.; Tanabe, K.; Tamura, F. A β-D-xylosidase-like gene is expressed during fruit ripening in Japanese pear (Pyrus pyrifolia Nakai). J. Exp. Bot. 1999, 50, 877–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bustamante, C.; Civello, P.; Martinez, G. Cloning of the promoter region of β-xylosidase (FaXyl1) gene and effect of plant growth regulators on the expression of FaXyl1 in strawberry fruit. Plant Sci. 2009, 177, 49–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markel, K.; Shih, P.M. From breeding to genome design: A genomic makeover for potatoes. Cell 2021, 184, 3843–3845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stokstad, E. The new potato. Science 2019, 363, 574–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, B.; Goutam, U.; Kukreja, S.; Sharma, J.; Sood, S.; Bhardwaj, V. Potato biofortification: An effective way to fight global hidden hunger. Physiol. Mol. Biol. Plants 2021, 27, 2297–2313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camire, M.E.; Kubow, S.; Donnelly, D.J. Potatoes and human health. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2009, 49, 823–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolnicar, P. Importance of Potato as a Crop and Practical Approaches to Potato Breeding. Methods Mol. Biol. 2021, 2354, 3–20. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zaheer, K.; Akhtar, M.H. Potato production, usage, and nutrition—A review. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2016, 56, 711–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wijesinha-Bettoni, R.; Mouillé, B. The contribution of potatoes to global food security, nutrition and healthy diets. Am. J. Potato Res. 2019, 96, 139–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebrechristos, H.Y.; Chen, W. Utilization of potato peel as eco-friendly products: A review. Food Sci. Nutr. 2018, 6, 1352–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassani, A.; Azapagic, A.; Shokri, N. Global predictions of primary soil salinization under changing climate in the 21st century. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 6663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Yu, F.; Xie, P.; Sun, S.; Qiao, X.; Tang, S.; Chen, C.; Yang, S.; Mei, C.; Yang, D.; et al. A Gγ protein regulates alkaline sensitivity in crops. Science 2023, 379, 8416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, W.; Zhang, H.; Yang, S.; Liu, L.; Xie, P.; Li, J.; Zhu, Y.; Ouyang, Y.; Xie, Q.; Zhang, H.; et al. Genetic modification of Gγ subunit AT1 enhances salt-alkali tolerance in main graminaceous crops. Natl. Sci. Rev. 2023, 10, 075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katerji, N.; Hoorn, J.W.V.; Hamdy, A.; Mastrorilli, M. Salt tolerance classification of crops according to soil salinity and to water stress day index. Agric. Water Manag. 2000, 43, 99–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altaf, M.A.; Behera, B.; Mangal, V.; Singhal, R.K.; Kumar, R.; More, S.; Naz, S.; Mandal, S.; Dey, A.; Saqib, M.; et al. Tolerance and adaptation mechanism of Solanaceous crops under salinity stress. Funct. Plant Biol. 2024, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozema, J.; Flowers, T. Crops for a salinized world. Science 2008, 322, 1478–1480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.; Zhang, H.; Song, C.; Zhu, J.; Shabala, S. Mechanisms of plant responses and adaptation to soil salinity. Innovation 2020, 1, 100017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X.; Yang, R.; Zhang, L.; Wei, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Shi, Y. A review of potato salt tolerance. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 10726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Liu, X.L.; Zhang, R.X.; Yuan, H.Y.; Wang, M.M.; Yang, H.Y.; Ma, H.Y.; Liu, D.; Jiang, C.J.; Liang, Z.W. Root damage under alkaline stress is associated with reactive oxygen species accumulation in rice (Oryza sativa L.). Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 1580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.S.; Ren, H.L.; Wei, Z.W.; Wang, Y.W.; Ren, W.B. Effects of neutral salt and alkali on ion distributions in the roots, shoots, and leaves of two alfalfa cultivars with differing degrees of salt tolerance. J. Integr. Agric. 2017, 16, 1800–1807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, S.; Hou, X.; Liang, X. Response mechanisms of plants under saline-alkali stress. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 667458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Xu, Y.; Tang, Z.; Jin, S.M.; Yang, S. The impact of alkaline stress on plant growth and its alkaline resistance mechanisms. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 13719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, C.W.; Shi, D.C.; Wang, D.L. Comparative effects of salt and alkali stresses on growth, osmotic adjustment and ionic balance of an alkali-resistant halophyte Suaeda glauca (Bge.). Plant Growth Regul. 2008, 56, 179–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, G.M.; Hamilton, J.P.; Wood, J.C.; Burke, J.T.; Zhao, H.; Vaillancourt, B.; Ou, S.; Jiang, J.; Buell, C.R. Construction of a chromosome-scale long-read reference genome assembly for potato. Gigascience 2020, 9, giaa100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wang, W.; Zhang, N.; Cheng, Y.; Hussain, S.; Wang, Y.; Tian, H.; Hussain, H.; Lin, R.; Yuan, Y.; et al. Antagonistic regulation of ABA responses by duplicated tandemly repeated DUF538 protein genes in Arabidopsis. Plants 2023, 12, 2989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ciarkowska, A.; Ostrowski, M.; Starzyńska, E.; Jakubowska, A. Plant SCPL acyltransferases: Multiplicity of enzymes with various functions in secondary metabolism. Phytochem. Rev. 2019, 18, 303–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.; Zheng, S.; Liu, K.; Yu, R.; Guan, P.; Hu, B.; Jiang, L.; Su, M.; Hu, G.; Chen, Q.; et al. Elucidating the molecular basis of salt tolerance in potatoes through miRNA expression and phenotypic analysis. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 2635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheller, H.V.; Ulvskov, P. Hemicelluloses. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2010, 61, 263–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.; Wilson, L.F.; Terrett, O.M.; Wurman-Rodrich, J.; Lyczakowski, J.J.; Yu, X.; Krogh, K.B.; Dupree, P. Evolution of glucuronoxylan side chain variability in vascular plants and the compensatory adaptations of cell wall-degrading hydrolases. New Phytol. 2024, 244, 1024–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, C.; Cao, Y.; Dai, J.; Li, G.; Manzoor, M.A.; Chen, C.; Deng, H. The multifaceted roles of MYC2 in plants: Toward transcriptional reprogramming and stress tolerance by jasmonate signaling. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 868874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wang, M.; Huang, Y.; Zhu, P.; Qian, G.; Zhang, Y.; Li, L. Genome-wide identification and analysis of R2R3-MYB genes response to saline–alkali stress in quinoa. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 9132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morcuende, R.; Bari, R.; Gibon, Y.; Zheng, W.; Pant, B.D.; Bläsing, O.; Usadel, B.; Czechowski, T.; Udvardi, M.K.; Stitt, M.; et al. Genome wide reprogramming of metabolism and regulatory networks of Arabidopsis in response to phosphorus. Plant Cell Environ. 2007, 30, 85–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmid, M.; Davison, T.S.; Henz, S.; Pape, U.; Demar, M.; Vingron, M.; Schölkopf, B.; Weigel, D.; Lohmann, J.U. A gene expression map of Arabidopsis thaliana development. Nat Genet. 2005, 37, 501–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakano, Y.; Kusunoki, K.; Hoekenga, O.A.; Tanaka, K.; Iuchi, S.; Sakata, Y.; Kobayashi, M.; Yamamoto, Y.Y.; Koyama, H.; Kobayashi, Y. Genome-wide association study and genomic prediction elucidate the distinct genetic architecture of aluminum and proton tolerance in Arabidopsis thaliana. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seifert, G.J.; Blaukopf, C. Irritable walls: The plant extracellular matrix and signaling. Plant Physiol. 2010, 153, 467–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaahtera, L.; Schulz, J.; Hamann, T. Cell wall integrity maintenance during plant development and interaction with the environment. Nat. Plants 2019, 5, 924–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mistry, J.; Chuguransky, S.; Williams, L.; Qureshi, M.; Salazar, G.A.; Sonnhammer, E.L.L.; Tosatto, S.C.E.; Paladin, L.; Raj, S.; Richardson, L.J.; et al. Pfam: The protein families database in 2021. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021, 49, D412–D419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mistry, J.; Finn, R.D.; Eddy, S.R.; Bateman, A.; Punta, M. Challenges in homology search: HMMER3 and convergent evolution of coiled-coil regions. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013, 41, e121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, S.; Wang, J.; Chitsaz, F.; Derbyshire, M.K.; Geer, R.C.; Gonzales, N.R.; Gwadz, M.; Hurwitz, D.I.; Januaryler, G.H.; Song, J.S.; et al. CDD/SPARCLE: The conserved domain database in 2020. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020, 48, D265–D268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Letunic, I.; Khedkar, S.; Bork, P. SMART: Recent updates, new developments and status in 2020. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021, 49, 458–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horton, P.; Park, K.J.; Obayashi, T.; Fujita, N.; Harada, H.; Adams-Collier, C.J.; Nakai, K. WoLF PSORT: Protein localization predictor. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007, 35, 585–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Wu, Y.; Li, J.; Wang, X.; Zeng, Z.; Xu, J.; Liu, Y.; Feng, J.; Chen, H.; He, Y.; et al. TBtools-II: A “one for all, all for one” bioinformatics platform for biological big-data mining. Mol. Plant. 2023, 16, 1733–1742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lescot, M.; Dehais, P.; Thijs, G.; Januaryal, K.; Moreau, Y.; Van de Peer, Y.; Rouze, P.; Rombauts, S. PlantCARE, a database of plant cis-acting regulatory elements and a portal to tools for in silico analysis of promoter sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002, 30, 325–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Gene Name | Locus ID | Chromosome Location | Number of Amino Acids (aa) | Protein MW (KDa) | Theoretical pI | Instability Index | Subcellular Localization |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| StBXL1 | Soltu.DM.01G024730.1 | Chr01 | 774 | 83,826.65 | 8.67 | 37.00 | Chloroplast |

| StBXL2 | Soltu.DM.01G044180.1 | Chr01 | 778 | 85,236.29 | 8.50 | 28.24 | Endoplasmic Reticulum |

| StBXL3 | Soltu.DM.02G026960.1 | Chr02 | 793 | 87,360.26 | 6.10 | 35.34 | Plasma Membrane |

| StBXL4 | Soltu.DM.04G029040.1 | Chr04 | 775 | 85,171.01 | 8.01 | 30.54 | Extracellular |

| StBXL5 | Soltu.DM.04G029050.1 | Chr04 | 774 | 85,184.09 | 6.98 | 31.39 | Chloroplast |

| StBXL6 | Soltu.DM.04G029120.1 | Chr04 | 779 | 86,171.92 | 9.09 | 29.82 | Plasma Membrane |

| StBXL7 | Soltu.DM.10G012310.1 | Chr10 | 836 | 91,199.12 | 8.26 | 28.46 | Vacuole |

| StBXL8 | Soltu.DM.11G017090.1 | Chr11 | 773 | 83,904.52 | 7.32 | 39.42 | Chloroplast |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zheng, S.; Zhang, X.; Lin, C.; Guan, P.; Liu, L.; Su, M.; Chen, Q.; Yu, R.; Jiang, L.; Yao, K.; et al. Genome-Wide Identification of β-D-Xylosidase Gene Family in Potato and Functional Analysis Under Alkaline Stress. Plants 2025, 14, 3790. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14243790

Zheng S, Zhang X, Lin C, Guan P, Liu L, Su M, Chen Q, Yu R, Jiang L, Yao K, et al. Genome-Wide Identification of β-D-Xylosidase Gene Family in Potato and Functional Analysis Under Alkaline Stress. Plants. 2025; 14(24):3790. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14243790

Chicago/Turabian StyleZheng, Shuangshuang, Xia Zhang, Caicai Lin, Peiyan Guan, Lu Liu, Mengyu Su, Qingshuai Chen, Ru Yu, Lingling Jiang, Ke Yao, and et al. 2025. "Genome-Wide Identification of β-D-Xylosidase Gene Family in Potato and Functional Analysis Under Alkaline Stress" Plants 14, no. 24: 3790. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14243790

APA StyleZheng, S., Zhang, X., Lin, C., Guan, P., Liu, L., Su, M., Chen, Q., Yu, R., Jiang, L., Yao, K., & Hu, L. (2025). Genome-Wide Identification of β-D-Xylosidase Gene Family in Potato and Functional Analysis Under Alkaline Stress. Plants, 14(24), 3790. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14243790