Comparative Study of Fatty Acid Desaturase (FAD) Members Reveals Their Differential Roles in Upland Cotton

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Identification of FAD Gene Family in Gossypium

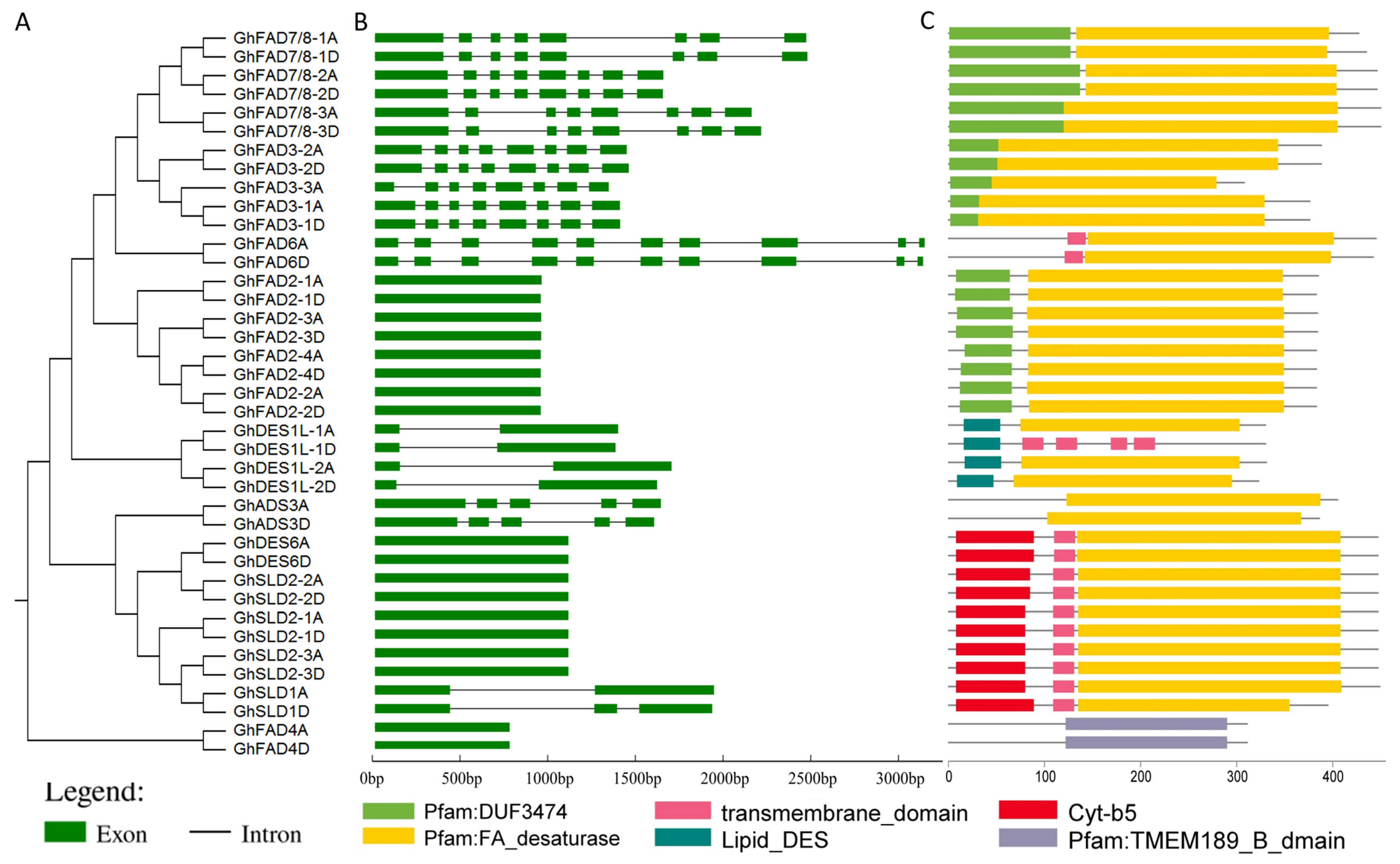

2.2. Conserved Structural Features Analysis of GhFAD Members

2.3. Chromosomal Localization and Gene Synteny Analysis of GhFAD Genes

2.4. Analysis of Cis-Elements in GhFAD Promoter and Regulatory Relationships

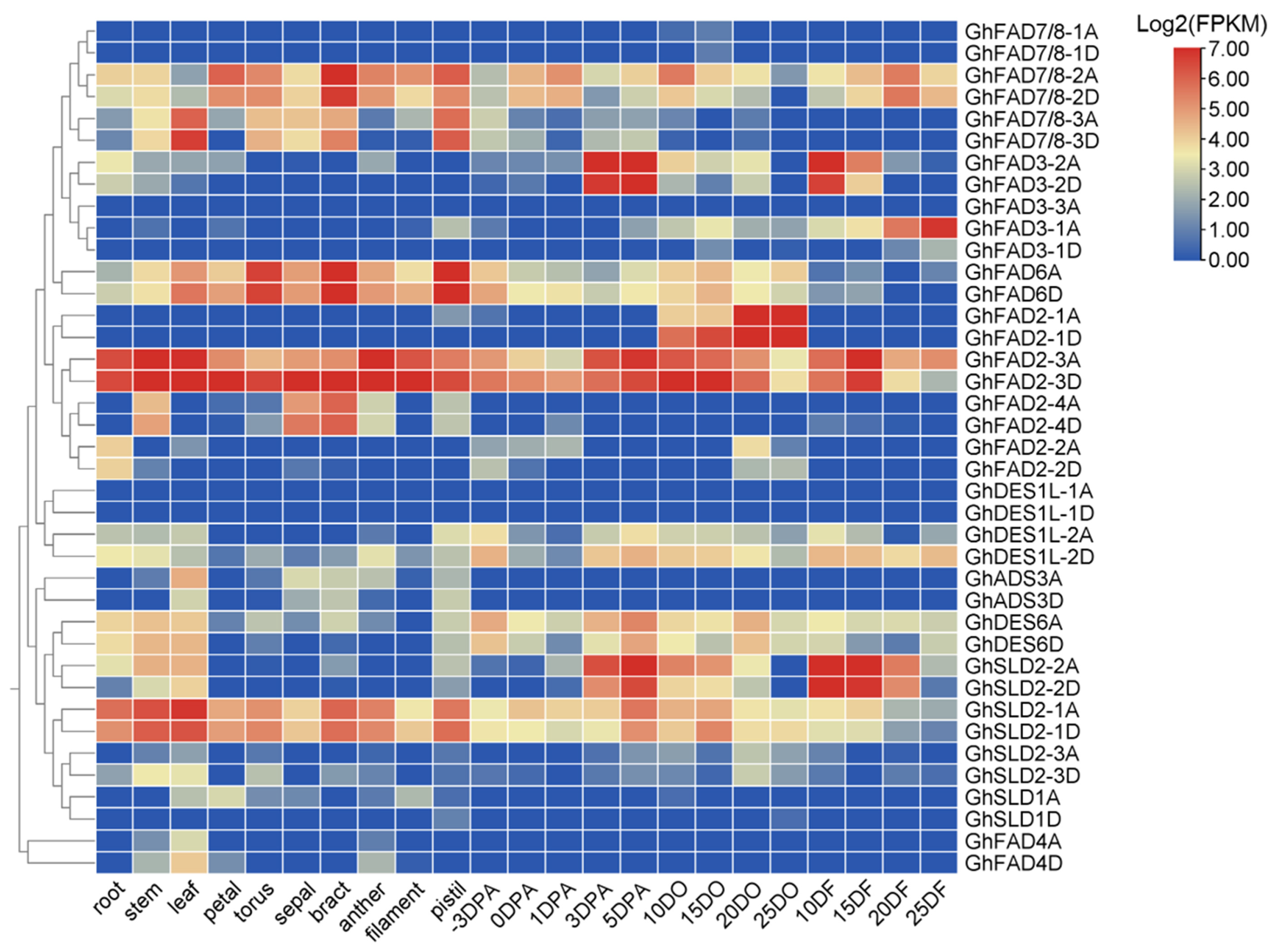

2.5. Expression Profiling of GhFAD Genes in Upland Cotton

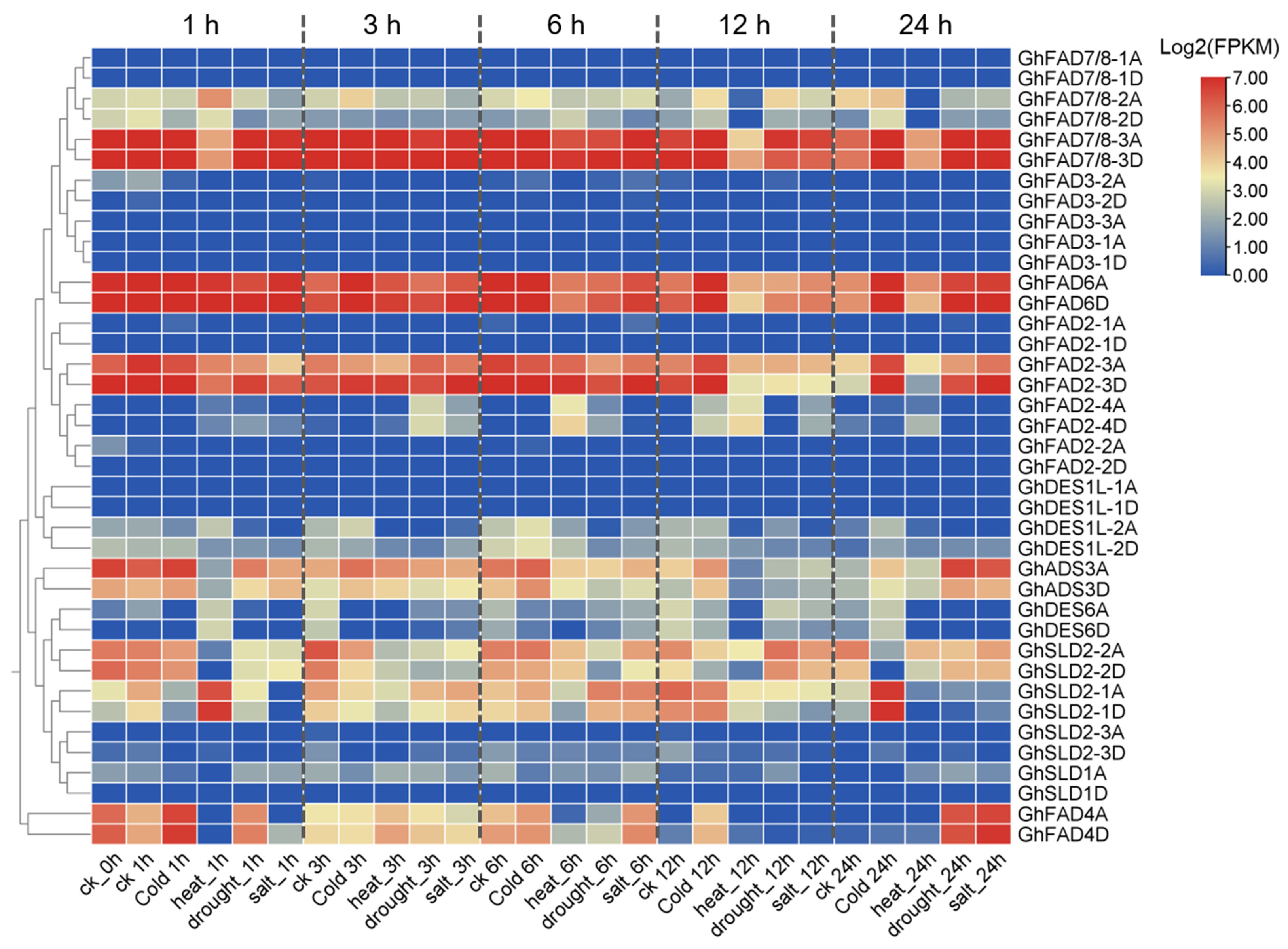

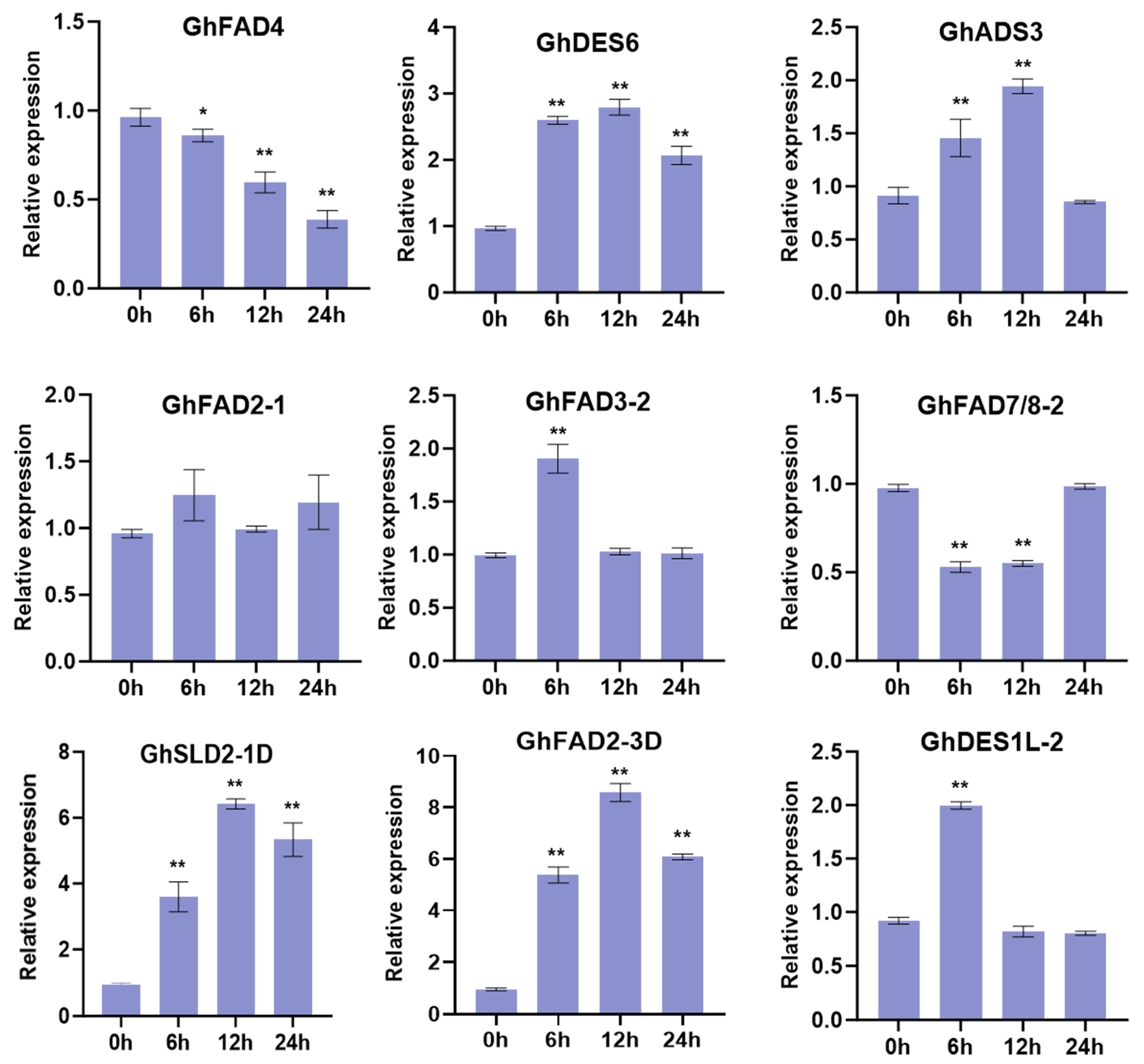

2.6. Response of GhFAD Genes to Abiotic Stresses in Upland Cotton

2.7. Overexpression of GhFAD2-3 Enhances Cold Stress Tolerance in Arabidopsis

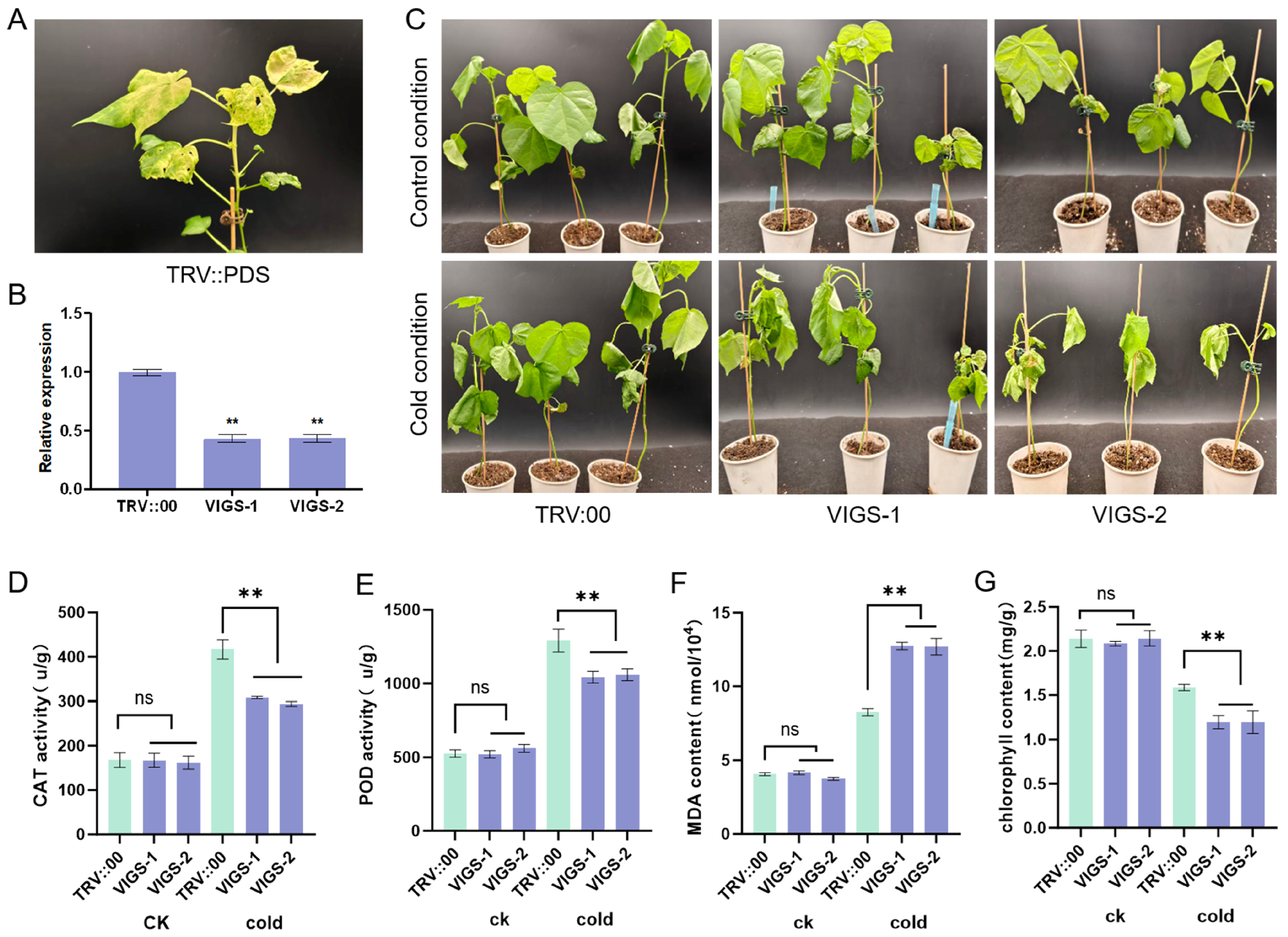

2.8. Functional Validation of GhFAD2-3 in Cold Stress Response via VIGS in Upland Cotton

3. Discussion

3.1. Functional Differentiation of FAD2 Genes During Evolution

3.2. Fatty Acid Composition Regulated by FAD2 and FAD3

3.3. GhFAD3-1 and GhFAD3-2 Sequentially Regulate Fiber Development

3.4. GhFAD2-3 Was Involved in Cold Stress Response

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Identification of FAD Gene Family Members in Gossypium

4.2. Phylogenetic, Structural, and Synteny Analysis of FAD Genes

4.3. Prediction of Transcription Factors and miRNAs Targeting GhFAD Genes

4.4. Expression Profile Analysis

4.5. RNA Extraction and Quantitative Real-Time PCR (RT-qPCR)

4.6. Vector Construction and Arabidopsis Transformation

4.7. Virus-Induced Gene Silencing (VIGS) in Cotton

4.8. Physiological and Biochemical Indicators Determination

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wen, X.; Chen, Z.; Yang, Z.; Wang, M.; Jin, S.; Wang, G.; Zhang, L.; Wang, L.; Li, J.; Saeed, S.; et al. A comprehensive overview of cotton genomics, biotechnology and molecular biological studies. Sci. China Life Sci. 2023, 66, 2214–2256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, H.N.; He, Z.; Ford, C.; Wyckoff, W.; Wu, Q. A review of cottonseed protein chemistry and non-food applications. Sustain. Chem. 2020, 1, 256–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Fu, M.; Li, H.; Wang, L.; Liu, R.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, X.; Jin, S. High-oleic acid content, nontransgenic allotetraploid cotton (Gossypium hirsutum L.) generated by knockout of GhFAD2 genes with CRISPR/Cas9 system. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2021, 19, 424–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Y.; Wang, Y.; Huang, Y.; Cui, Y.; Hua, J. Gene network of oil accumulation reveals expression profiles in developing embryos and fatty acid composition in upland cotton. J. Plant Physiol. 2018, 228, 101–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Terés, S.; Barceló-Coblijn, G.; Benet, M.; Alvarez, R.; Bressani, R.; Halver, J.E.; Escribá, P.V. Oleic acid content is responsible for the reduction in blood pressure induced by olive oil. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 16, 13811–13816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davis, K.E.; Prasad, C.; Imrhan, V. Consumption of a diet rich in cottonseed oil (CSO) lowers total and LDL cholesterol in normo-cholesterolemic subjects. Nutrients 2012, 4, 602–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baud, S.; Lepiniec, L. Physiological and developmental regulation of seed oil production. Prog. Lipid Res. 2010, 49, 235–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li-Beisson, Y.; Shorrosh, B.; Beisson, F.; Andersson, M.X.; Arondel, V.; Bates, P.D.; Baud, S.; Bird, D.; DeBono, A.; Durrett, T.P.; et al. Acyl-lipid metabolism. Arab. Book 2013, 11, e0161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dar, A.A.; Choudhury, A.R.; Kancharla, P.K.; Arumugam, N. The FAD2 gene in plants: Occurrence, regulation, and role. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 1789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gishini, M.F.S.; Kachroo, P.; Hildebrand, D. Fatty acid desaturase 3-mediated α-linolenic acid biosynthesis in plants. Plant Physiol. 2025, 197, kiaf012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohlroggeav’, J.; Browseb, J. Lipid biosynthesis. Plant Cell 1995, 7, 957–970. [Google Scholar]

- Schlueter, J.A.; Vasylenko-Sanders, I.F.; Deshpande, S.; Yi, J.; Siegfried, M.; Roe, B.A.; Schlueter, S.D.; Scheffler, B.E.; Shoemaker, R.C. The FAD2 gene family of soybean: Insights into the structural and functional divergence of a paleopolyploid genome. Crop Sci. 2007, 47, S17–S26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haun, W.; Coffman, A.; Clasen, B.M.; Demorest, Z.L.; Lowy, A.; Ray, E.; Retterath, A.; Stoddard, T.; Juillerat, A.; Cedrone, F.; et al. Improved soybean oil quality by targeted mutagenesis of the fatty acid desaturase 2 gene family. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2014, 12, 934–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wood, C.C.; Okada, S.; Taylor, M.C.; Menon, A.; Mathew, A.; Cullerne, D.; Stephen, S.J.; Allen, R.S.; Zhou, X.R.; Liu, Q.; et al. Seed-specific RNAi in safflower generates a superhigh oleic oil with extended oxidative stability. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2018, 16, 1788–1796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, S.; Liu, D.X.; Lu, S.; Yu, L.; Li, Y.; Lin, S.; Li, L.; Du, Z.; Liu, X.; Li, X.; et al. Development and screening of EMS mutants with altered seed oil content or fatty acid composition in Brassica napus. Plant J. 2020, 104, 1410–1422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shockey, J.; Dowd, M.; Mack, B.; Gilbert, M.; Scheffler, B.; Ballard, L.; Frelichowski, J.; Mason, C. Naturally occurring high oleic acid cottonseed oil: Identification and functional analysis of a mutant allele of Gossypium barbadense fatty acid desaturase-2. Planta 2017, 245, 611–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shockey, J.; Gilbert, M.K.; Thyssen, G.N. A mutant cotton fatty acid desaturase 2-1d allele causes protein mistargeting and altered seed oil composition. BMC Plant Biol. 2023, 23, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Q.; Singh, S.P.; Green, A.G. High-stearic and high-oleic cottonseed oils produced by hairpin RNA-mediated post-transcriptional gene silencing. Plant Physiol. 2002, 129, 1732–1743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Zhao, Y.P.; Zhu, H.G.; Zhu, Q.H.; Sun, J. Simultaneous silencing of GhFAD2-1 and GhFATB enhances the quality of cottonseed oil with high oleic acid. J. Plant Physiol. 2017, 215, 132–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, L.; Zhao, H.; Liu, H.; Wang, X.; Li, X.; Qu, P.; Xue, L.; Huang, B.; Qi, F.; Dai, X.; et al. Development of novel transgene-free high-oleic peanuts through CRISPR-Cas9-mediated gene editing of two AhFAD2 homologues. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2025, 23, 4618–4620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, P.; Deng, Q.; Wang, W.; Garg, V.; Lu, Q.; Huang, L.; Wang, R.; Li, H.; Huai, D.; Chen, X.; et al. scRNA-seq reveals the mechanism of fatty acid desaturase 2 mutation to repress leaf growth in peanut (Arachis hypogaea L.). Cells 2023, 12, 2305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, J.J.; Ahmad, N.; Zhou, X.; He, W.; Wang, J.; Shan, C.; Chen, Z.; Ji, W.; Liu, Z. Divergent fatty acid desaturase 2 is essential for falcarindiol biosynthesis in carrot. Plant Commun. 2025, 6, 101323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, F.; Ma, L.; Wang, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhang, X.; Xue, F.; Nie, X.; Zhu, Q.; Sun, J. GhFAD2-3 is required for anther development in Gossypium hirsutum. BMC Plant Biol. 2019, 19, 393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Fan, M.; Shen, Y.; Zhao, H.; Weng, S.; Chen, Z.; Xiao, G. GhFAD3-4 promotes fiber cell elongation and cell wall thickness by increasing PI and IP3 accumulation in cotton. Plants 2024, 13, 1510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kargiotidou, A.; Deli, D.; Galanopoulou, D.; Tsaftaris, A.; Farmaki, T. Low temperature and light regulate delta 12 fatty acid desaturases (FAD2) at a transcriptional level in cotton (Gossypium hirsutum). J. Exp. Bot. 2008, 59, 2043–2056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menard, G.N.; Moreno, J.M.; Bryant, F.M.; Munoz-Azcarate, O.; Kelly, A.A.; Hassani-Pak, K.; Kurup, S.; Eastmond, P.J. Genome wide analysis of fatty acid desaturation and its response to temperature. Plant Physiol. 2017, 173, 1594–1605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luisa Hernández, M.; Dolores Sicardo, M.; Arjona, P.M.; Martínez-Rivas, J.M. Specialized functions of olive FAD2 gene family members related to fruit development and the abiotic stress response. Plant Cell Physiol. 2019, 61, 427–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Li, K.; Zhou, G.; He, S. Effects of temperature and salt stress on the expression of delta-12 fatty acid desaturase genes and fatty acid compositions in safflower. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 2765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, V.C.; Nakamura, Y.; Kanehara, K. Membrane lipid polyunsaturation mediated by FATTY ACID DESATURASE 2 (FAD2) is involved in endoplasmic reticulum stress tolerance in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 2019, 99, 478–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.W.; Padilla, C.S.; Gupta, C.; Galla, A.; Pereira, A.; Li, J.; Goggin, F.L. The fatty acid desaturase2 family in tomato contributes to primary metabolism and stress responses. Plant Physiol. 2020, 182, 1083–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, R.; Zou, Y.; Guo, X.; Li, H.; Lu, H. Fatty acid desaturases (FADs) modulate multiple lipid metabolism pathways to improve plant resistance. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2022, 49, 9997–10011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Jing, X.; Wang, P.; Wang, G.; Xiang, M.; Li, P.; Zou, H.; Li, H.; Wu, Z.; Wang, C.; et al. A fijivirus capsid protein hijacks autophagy degrading an ω-3 fatty acid desaturase to suppress jasmonate-mediated antiviral defence. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2025, 23, 2891–2907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- E, Z.; Chen, C.; Yang, J.; Tong, H.; Li, T.; Wang, L.; Chen, H. Genome-wide analysis of fatty acid desaturase genes in rice (Oryza sativa L.). Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 19445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Wei, J.; He, L.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Xu, X.; Wei, Y.; Ge, S.; Ding, D.; Liu, M.; et al. Identification of fatty acid desaturases in Maize and their differential responses to low and high temperature. Genes 2019, 10, 445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.; Zhao, S.; Wang, S.; Wang, H.; Zhang, Z. Identification and analysis of the FAD gene family in walnuts (Juglans regia L.) based on transcriptome data. BMC Genom. 2020, 21, 299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, Y.; Wu, F.; Chen, R.; Wang, X.; Tseke Inkabanga, A.; Huang, L.; Qin, S.; Zhang, M.; Chai, Y. Genome-wide analysis of fatty acid desaturase genes in chia (Salvia hispanica) reveals their crucial roles in cold response and seed oil formation. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2023, 199, 107737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zou, Z.; Fu, X.; Li, C.; Huang, J.; Zhao, Y. Insights into membrane-bound fatty acid desaturase genes in tigernut (Cyperus esculentus L.), an oil-rich tuber plant in Cyperaceae. BMC Plant Biol. 2025, 25, 382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Xiaoyang, C.; Li, J.; Wu, H.; Wang, Y.; Di, P.; Deyholos, M.K.; Zhang, J. Whole-genome identification of the flax fatty acid desaturase gene family and functional analysis of the LuFAD2.1 gene under cold stress conditions. Plant Cell Environ. 2025, 48, 2221–2239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, J.; Dong, Y.; Liu, W.; He, Q.; Daud, M.K.; Chen, J.; Zhu, S. Genome-wide identification of membrane-bound fatty acid desaturase genes in Gossypium hirsutum and their expressions during abiotic stress. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 45711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, W.; Li, W.; He, Q.; Daud, M.K.; Chen, J.; Zhu, S. Characterization of 19 genes encoding membrane-bound fatty acid desaturases and their expression profiles in Gossypium raimondii under low temperature. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0123281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, Y.; Han, J.; Jin, S.; Han, Z.; Si, Z.; Yan, S.; Xuan, L.; Yu, G.; Guan, X.; Fang, L.; et al. Post-polyploidization centromere evolution in cotton. Nat. Genet. 2025, 57, 1021–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Liu, H.; Zhan, W.; Yu, Z.; Qin, E.; Liu, S.; Yang, T.; Xiang, N.; Kudrna, D.; Chen, Y.; et al. The chromosome-scale reference genome of safflower (Carthamus tinctorius) provides insights into linoleic acid and flavonoid biosynthesis. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2021, 19, 1725–1742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumann, N.; Harman, M.; Kuhlman, A.; Durrett, T.P. Arabidopsis diacylglycerol acyltransferase1 mutants require fatty acid desaturation for normal seed development. Plant J. 2024, 119, 916–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, N.; Liu, X.; Chen, Y.; Wang, H.; Zhao, Y.; Du, C.; Lu, C.; Zhang, M. Creating ultra-high linolenic acid camelina by co-expressing AtFAD2sm with synonymous mutations and BnFAD3 in the fae1 mutant. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2025, 23, 4536–4538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, H.; Li, Y.; Xiong, X.P.; Liu, X.; Xue, F.; Sun, J.; Zhu, Q.H.; Liu, F. pseudo-GhFAD2-1 is a lncRNA involved in regulating cottonseed oleic and linoleic acid ratios and seed size in Gossypium hirsutum. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2025, 23, 5229–5251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.J.; Xiao, G.H.; Liu, N.J.; Liu, D.; Chen, P.S.; Qin, Y.M.; Zhu, Y.X. Targeted lipidomics studies reveal that linolenic acid promotes cotton fiber elongation by activating phosphatidylinositol and phosphatidylinositol monophosphate biosynthesis. Mol. Plant 2015, 8, 911–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, L.; Chen, W.; Xu, X.; Zhang, J.; Singh, T.K.; Liu, S.; Zhang, D.; Tian, L.; White, A.; Shrestha, P.; et al. Engineering trienoic fatty acids into cottonseed oil improves low-temperature seed germination, plant photosynthesis and cotton fiber quality. Plant Cell Physiol. 2021, 61, 1335–1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, F.; Fan, G.; Lu, C.; Xiao, G.; Zou, C.; Kohel, R.J.; Ma, Z.; Shang, H.; Ma, X.; Wu, J.; et al. Genome sequence of cultivated Upland cotton (Gossypium hirsutum TM-1) provides insights into genome evolution. Nat. Biotechnol. 2015, 33, 524–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yurchenko, O.P.; Park, S.; Ilut, D.C.; Inmon, J.J.; Millhollon, J.C.; Liechty, Z.; Page, J.T.; Jenks, M.A.; Chapman, K.D.; Udall, J.A.; et al. Genome-wide analysis of the omega-3 fatty acid desaturase gene family in Gossypium. BMC Plant Biol. 2014, 14, 312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Gao, L.; Yun, Q.; Wang, W.; Liu, X.; Tang, W.; Sun, Y.; Shang, J.X. Protein tyrosine phosphatase IBR5 positively affects salt stress response by modulating CAT2 activity. Plant Sci. 2025, 359, 112615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, G.; Wu, Z.; Percy, R.G.; Bai, M.Z.; Li, Y.; Frelichowski, J.E.; Hu, J.; Wang, K.; Yu, J.Z.; Zhu, Y.X. Genome sequence of Gossypium herbaceum and genome updates of Gossypium arboreum and Gossypium hirsutum provide insights into cotton A-genome evolution. Nat. Genet. 2020, 52, 516–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paterson, A.H.; Wendel, J.F.; Gundlach, H.; Guo, H.; Jenkins, J.; Jin, D.; Llewellyn, D.; Showmaker, K.C.; Shu, S.; Udall, J.; et al. Repeated polyploidization of Gossypium genomes and the evolution of spinnable cotton fibres. Nature 2012, 492, 423–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, J.; Jung, S.; Cheng, C.H.; Lee, T.; Zheng, P.; Buble, K.; Crabb, J.; Humann, J.; Hough, H.; Jones, D.; et al. CottonGen: The community database for cotton genomics, genetics, and breeding research. Plants 2021, 10, 2805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gasteiger, E.; Hoogland, C.; Gattiker, A.; Duvaud, S.; Wilkins, M.R.; Appel, R.D.; Bairoch, A. Protein identification and analysis tools on the ExPASy server. In The Proteomics Protocols Handbook; Walker, J.M., Ed.; Humana Press: Totowa, NJ, USA, 2005; pp. 571–607. [Google Scholar]

- Lescot, M.; Déhais, P.; Thijs, G.; Marchal, K.; Moreau, Y.; Van De Peer, Y.; Rouzé, P.; Rombauts, S. PlantCARE, a database of plant cis-acting regulatory elements and a portal to tools for in silico analysis of promoter sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002, 30, 325–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Stecher, G.; Suleski, M.; Sanderford, M.; Sharma, S.; Tamura, K. MEGA12: Molecular evolutionary genetic analysis version 12 for adaptive and green computing. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2024, 41, msae263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Letunic, I.; Khedkar, S.; Bork, P. SMART: Recent updates, new developments and status in 2020. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021, 49, D458–D460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Wu, Y.; Li, J.; Wang, X.; Zeng, Z.; Xu, J.; Liu, Y.; Feng, J.; Chen, H.; He, Y.; et al. TBtools-II: A “one for all, all for one” bioinformatics platform for biological big-data mining. Mol. Plant 2023, 16, 1733–1742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, T.L.; Johnson, J.; Grant, C.E.; Noble, W.S. The MEME suite. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015, 43, W39–W49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Wu, Y.; Xia, R. A painless way to customize Circos plot: From data preparation to visualization using TBtools. iMeta 2022, 1, e35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, F.; Yang, D.C.; Meng, Y.Q.; Jin, J.; Gao, G. PlantRegMap: Charting functional regulatory maps in plants. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020, 48, D1104–D1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dai, X.; Zhuang, Z.; Zhao, P.X. PsRNATarget: A plant small RNA target analysis server (2017 release). Nucleic Acids Res. 2018, 46, W49–W54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shannon, P.; Markiel, A.; Ozier, O.; Baliga, N.S.; Wang, J.T.; Ramage, D.; Amin, N.; Schwikowski, B.; Ideker, T. Cytoscape: A software environment for integrated models of biomolecular interaction networks. Genome Res. 2003, 13, 2498–2504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, Y.; Chen, J.; Fang, L.; Zhang, Z.; Ma, W.; Niu, Y.; Ju, L.; Deng, J.; Zhao, T.; Lian, J.; et al. Gossypium barbadense and Gossypium hirsutum genomes provide insights into the origin and evolution of allotetraploid cotton. Nat. Genet. 2019, 51, 739–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pertea, M.; Kim, D.; Pertea, G.M.; Leek, J.T.; Salzberg, S.L. Transcript-level expression analysis of RNA-seq experiments with HISAT, StringTie and Ballgown. Nat. Protoc. 2016, 11, 1650–1667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clough, S.J.; Bent, A.F. Floral dip: A simplified method for Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 1998, 16, 735–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Name | Gene Locus ID | CDS | Exons | Amino Acids | Mw (Da) | pI | Subcellular Location |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GhFAD4A | GhChrA01G0766.1 | 936 | 1 | 311 | 34,623.59 | 7.24 | mitochondrion |

| GhFAD2-4A | GhChrA01G1558.1 | 1152 | 1 | 383 | 44,369.41 | 8.97 | peroxisome |

| GhFAD2-2A | GhChrA01G1559.1 | 1152 | 1 | 383 | 44,367.14 | 9.06 | peroxisome |

| GhFAD7/8-1A | GhChrA01G2801.1 | 1284 | 8 | 427 | 49,534.07 | 8.17 | plastid |

| GhFAD7/8-2A | GhChrA04G1241.1 | 1341 | 8 | 446 | 50,961.32 | 8.47 | endoplasmic reticulum |

| GhDES6A | GhChrA05G0444.1 | 1344 | 1 | 447 | 51,161.89 | 8.43 | plastid |

| GhADS3A | GhChrA05G1321.1 | 1218 | 5 | 405 | 46,282.05 | 9.26 | endoplasmic reticulum |

| GhDES1L-1A | GhChrA06G1765.1 | 993 | 2 | 330 | 38,403.38 | 7.29 | chloroplast |

| GhFAD3-1A | GhChrA07G1217.1 | 1131 | 8 | 376 | 43,504.96 | 8.84 | cytoplasm |

| GhSLD2-1A | GhChrA07G1670.1 | 1344 | 1 | 447 | 51,183.94 | 8.36 | plastid |

| GhSLD2-2A | GhChrA08G3245.1 | 1344 | 1 | 447 | 51,201.35 | 8.64 | plastid |

| GhFAD3-2A | GhChrA09G1203.1 | 1167 | 8 | 388 | 45,033.80 | 9.05 | cytoplasm |

| GhDES1L-2A | GhChrA10G0228.1 | 996 | 2 | 331 | 38,623.81 | 8.82 | chloroplast |

| GhFAD7/8-3A | GhChrA10G2968.1 | 1353 | 8 | 450 | 51,185.89 | 8.91 | mitochondrion |

| GhSLD2-3A | GhChrA11G1028.1 | 1344 | 1 | 447 | 51,379.35 | 8.94 | plastid |

| GhFAD2-3A | GhChrA11G3993.1 | 1155 | 1 | 384 | 44,247.99 | 8.96 | peroxisome |

| GhSLD1A | GhChrA12G1489.1 | 1350 | 2 | 449 | 51,874.66 | 7.98 | plastid |

| GhFAD3-3A | GhChrA13G0736.1 | 927 | 8 | 308 | 35,414.61 | 8.69 | cytoplasm |

| GhFAD6A | GhChrA13G2456.1 | 1338 | 10 | 445 | 51,585.95 | 9.09 | chloroplast |

| GhFAD2-1A | GhChrA13G2779.1 | 1158 | 1 | 385 | 44,061.98 | 9.09 | peroxisome |

| GhFAD4D | GhChrD01G0748.1 | 936 | 1 | 311 | 34,511.51 | 7.69 | chloroplast |

| GhFAD2-4D | GhChrD01G1516.1 | 1152 | 1 | 383 | 44,283.42 | 8.94 | plastid |

| GhFAD2-2D | GhChrD01G1517.1 | 1152 | 1 | 383 | 44,184.98 | 9.04 | peroxisome |

| GhFAD7/8-1D | GhChrD01G2692.1 | 1308 | 8 | 435 | 50,398.01 | 7.42 | plastid |

| GhFAD7/8-2D | GhChrD04G1715.1 | 1341 | 8 | 446 | 50,716.97 | 8.52 | endoplasmic reticulum |

| GhDES6D | GhChrD05G0455.1 | 1344 | 1 | 447 | 51,197.00 | 8.68 | plastid e |

| GhADS3D | GhChrD05G1299.1 | 1161 | 5 | 386 | 44,237.73 | 9.37 | plastid |

| GhDES1L-1D | GhChrD06G1671.1 | 993 | 2 | 330 | 38,346.32 | 6.95 | plastid |

| GhFAD3-1D | GhChrD07G1186.1 | 1131 | 8 | 376 | 43,560.10 | 8.83 | plastid |

| GhSLD2-1D | GhChrD07G1624.1 | 1344 | 1 | 447 | 51,182.96 | 8.55 | plastid |

| GhSLD2-2D | GhChrD08G3126.1 | 1344 | 1 | 447 | 51,273.35 | 8.61 | cytoplasm |

| GhFAD3-2D | GhChrD09G1113.1 | 1167 | 8 | 388 | 45,107.92 | 9.05 | cytoplasm |

| GhDES1L-2D | GhChrD10G0246.1 | 972 | 2 | 323 | 37,794.78 | 7.30 | chloroplast |

| GhFAD7/8-3D | GhChrD10G2859.1 | 1353 | 8 | 450 | 51,146.85 | 8.91 | mitochondrion |

| GhSLD2-3D | GhChrD11G1055.1 | 1344 | 1 | 447 | 51,370.34 | 8.94 | plastid |

| GhFAD2-3D | GhChrD11G3903.1 | 1155 | 1 | 384 | 44,271.03 | 9.04 | peroxisome |

| GhSLD1D | GhChrD12G1413.1 | 1188 | 3 | 395 | 45,134.87 | 7.30 | plastid |

| GhFAD6D | GhChrD13G2333.1 | 1329 | 10 | 442 | 51,322.69 | 9.17 | chloroplast |

| GhFAD2-1D | GhChrD13G2655.1 | 1152 | 1 | 383 | 43,892.69 | 8.95 | endoplasmic reticulum |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hu, F.; He, S.; Hou, X.; He, J.; Wang, P.; Ma, L.; Chen, D.; Yan, H.; Gong, J.; Yuan, Y.; et al. Comparative Study of Fatty Acid Desaturase (FAD) Members Reveals Their Differential Roles in Upland Cotton. Plants 2025, 14, 3767. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14243767

Hu F, He S, Hou X, He J, Wang P, Ma L, Chen D, Yan H, Gong J, Yuan Y, et al. Comparative Study of Fatty Acid Desaturase (FAD) Members Reveals Their Differential Roles in Upland Cotton. Plants. 2025; 14(24):3767. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14243767

Chicago/Turabian StyleHu, Fuxin, Shanyu He, Xiangjiang Hou, Jiale He, Panpan Wang, Lei Ma, Di Chen, Haoliang Yan, Juwu Gong, Youlu Yuan, and et al. 2025. "Comparative Study of Fatty Acid Desaturase (FAD) Members Reveals Their Differential Roles in Upland Cotton" Plants 14, no. 24: 3767. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14243767

APA StyleHu, F., He, S., Hou, X., He, J., Wang, P., Ma, L., Chen, D., Yan, H., Gong, J., Yuan, Y., Shang, H., & Zhao, Y. (2025). Comparative Study of Fatty Acid Desaturase (FAD) Members Reveals Their Differential Roles in Upland Cotton. Plants, 14(24), 3767. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14243767