Diversity and Distribution of Bryophytes Along an Altitudinal Gradient on Flores Island (Azores, Portugal)

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Species Inventory and Sampling Completeness

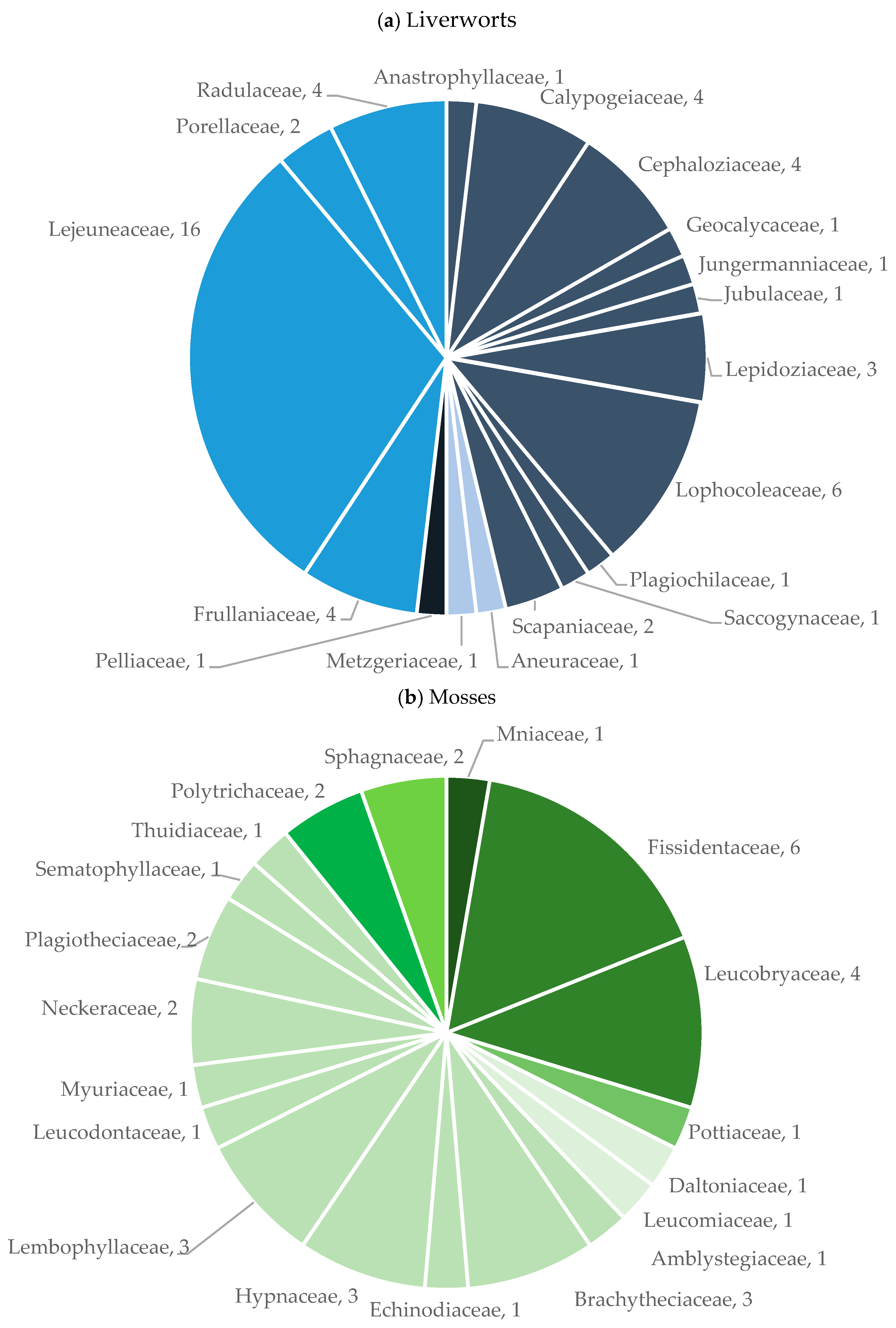

2.1.1. Floristics

2.1.2. Colonization Status and Vulnerability

2.1.3. Sampling Completeness

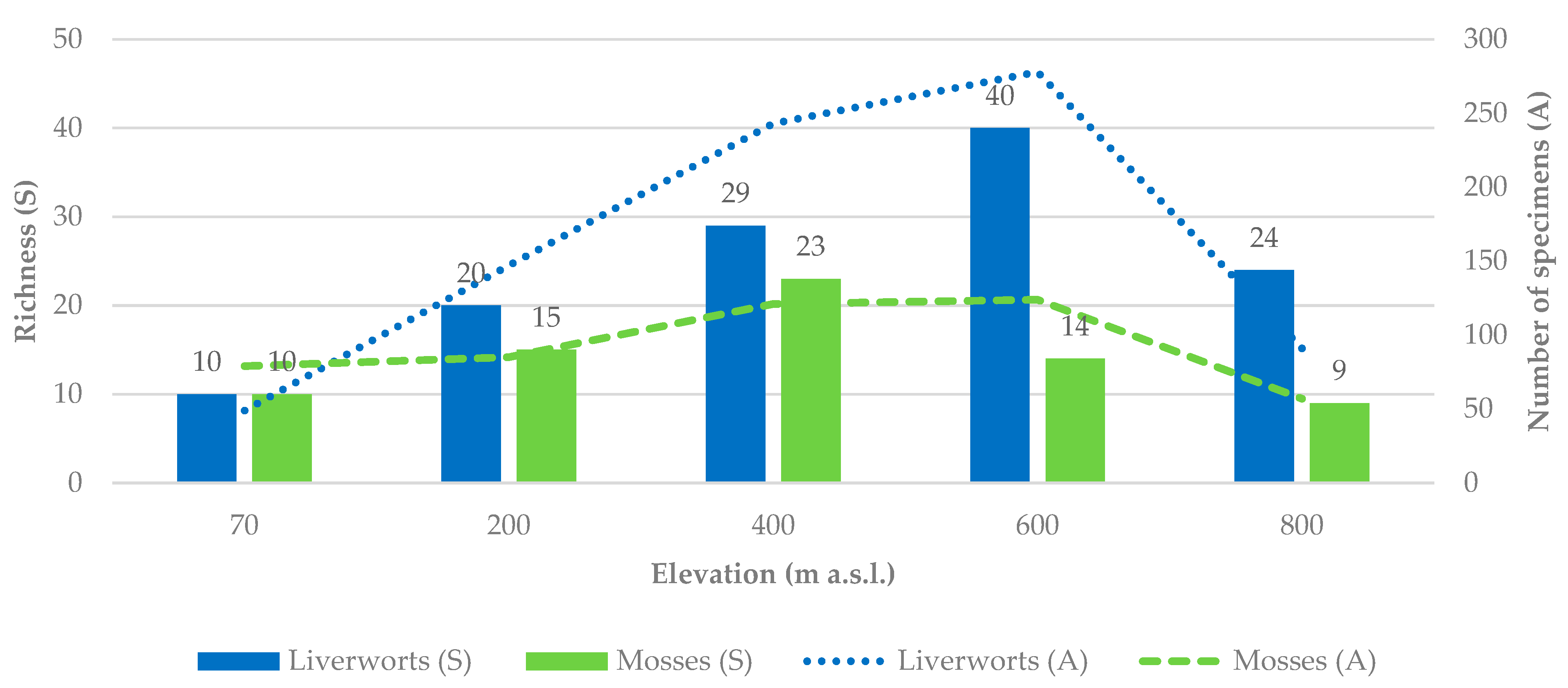

2.2. Altitudinal Gradient and Mid-Domain Effect

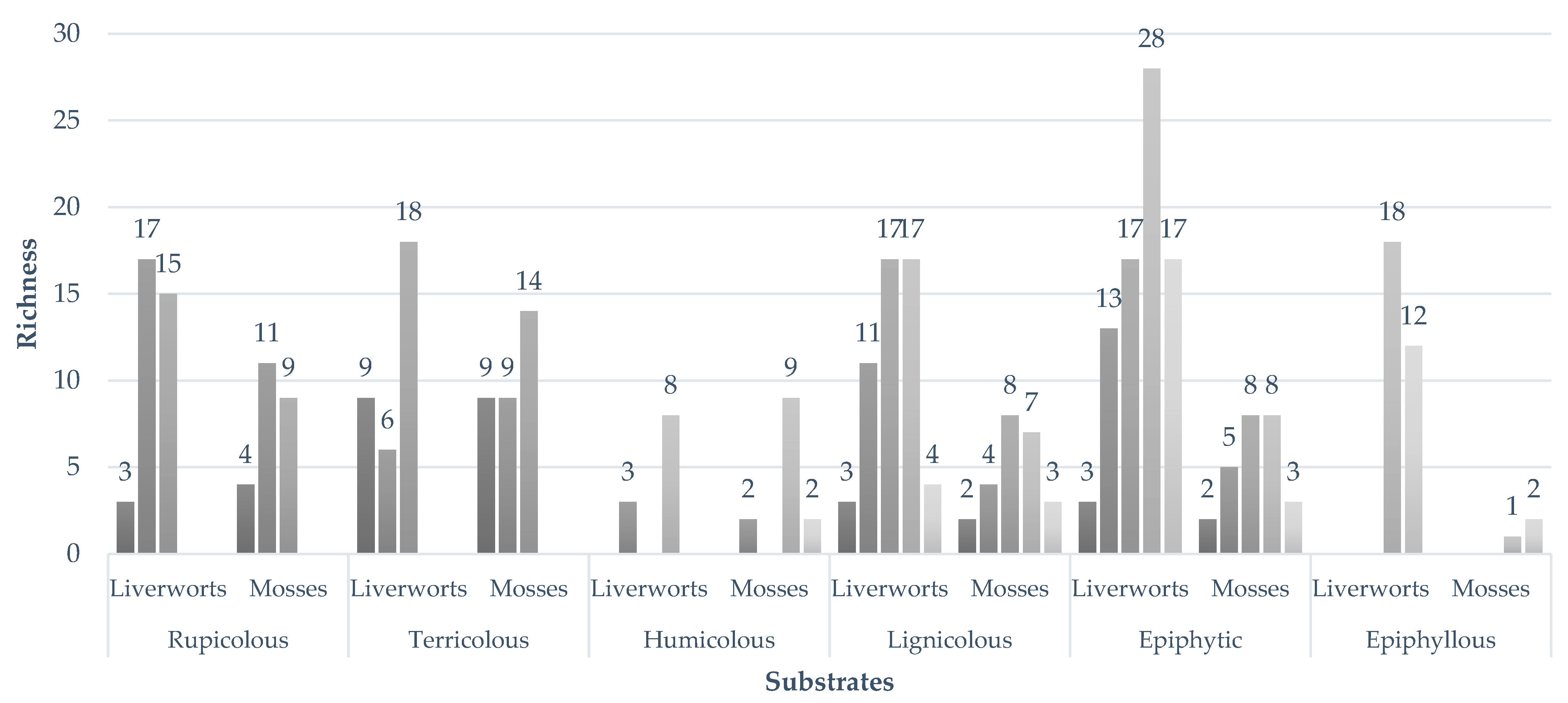

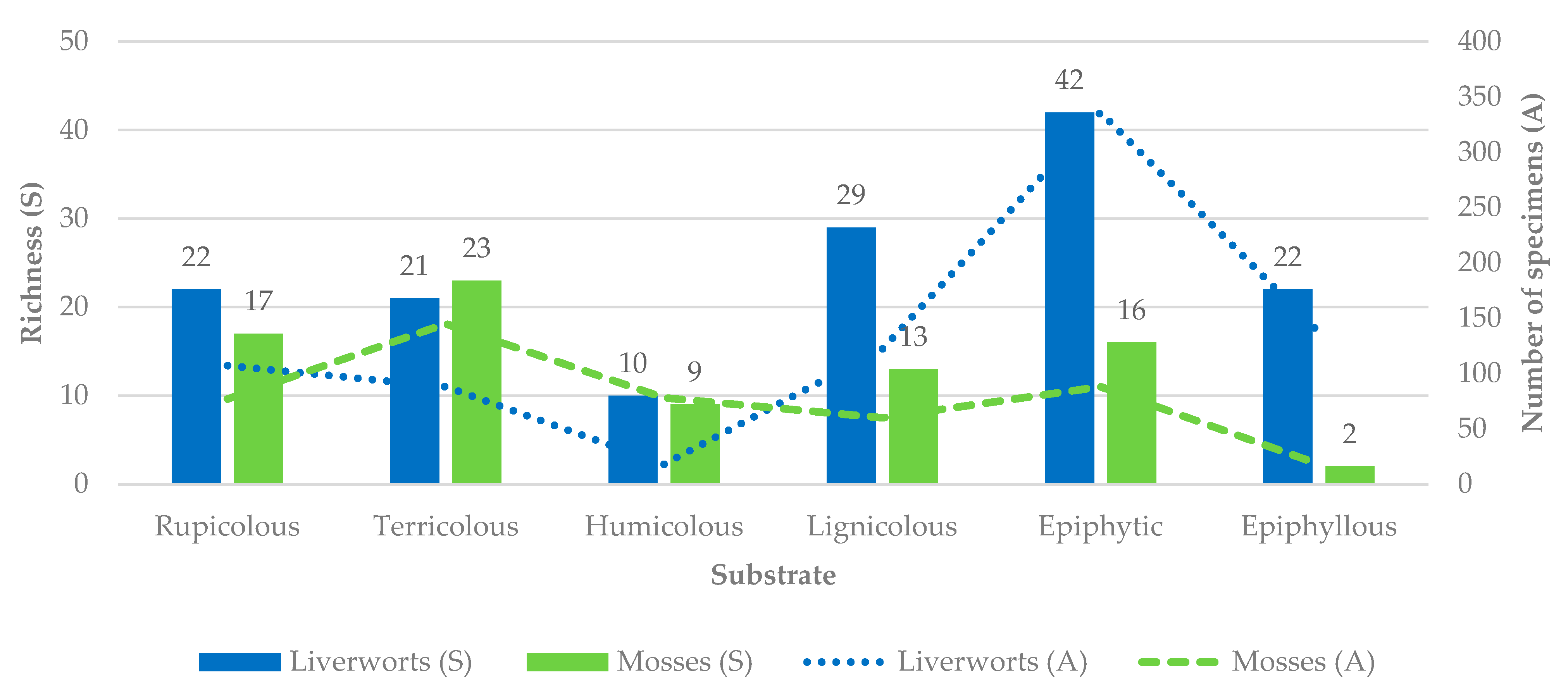

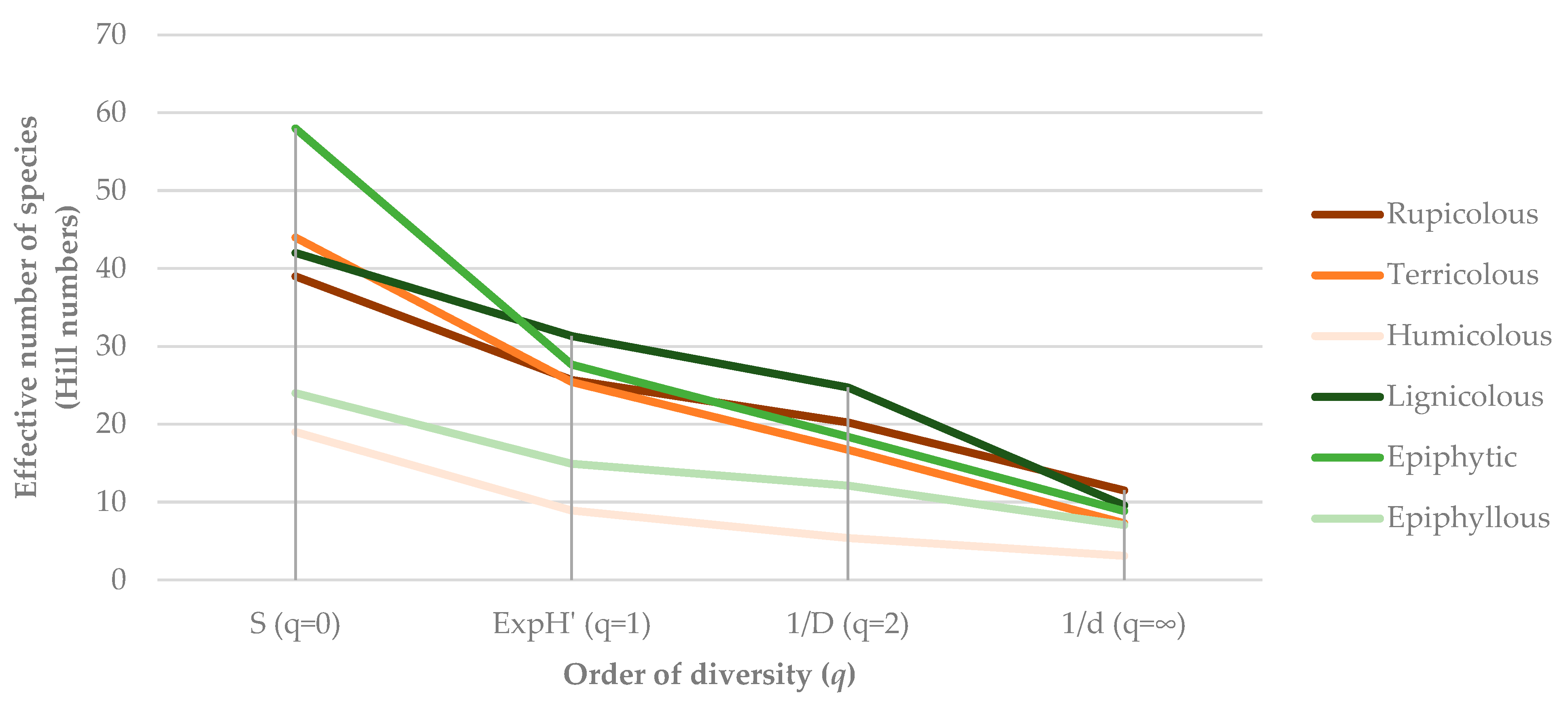

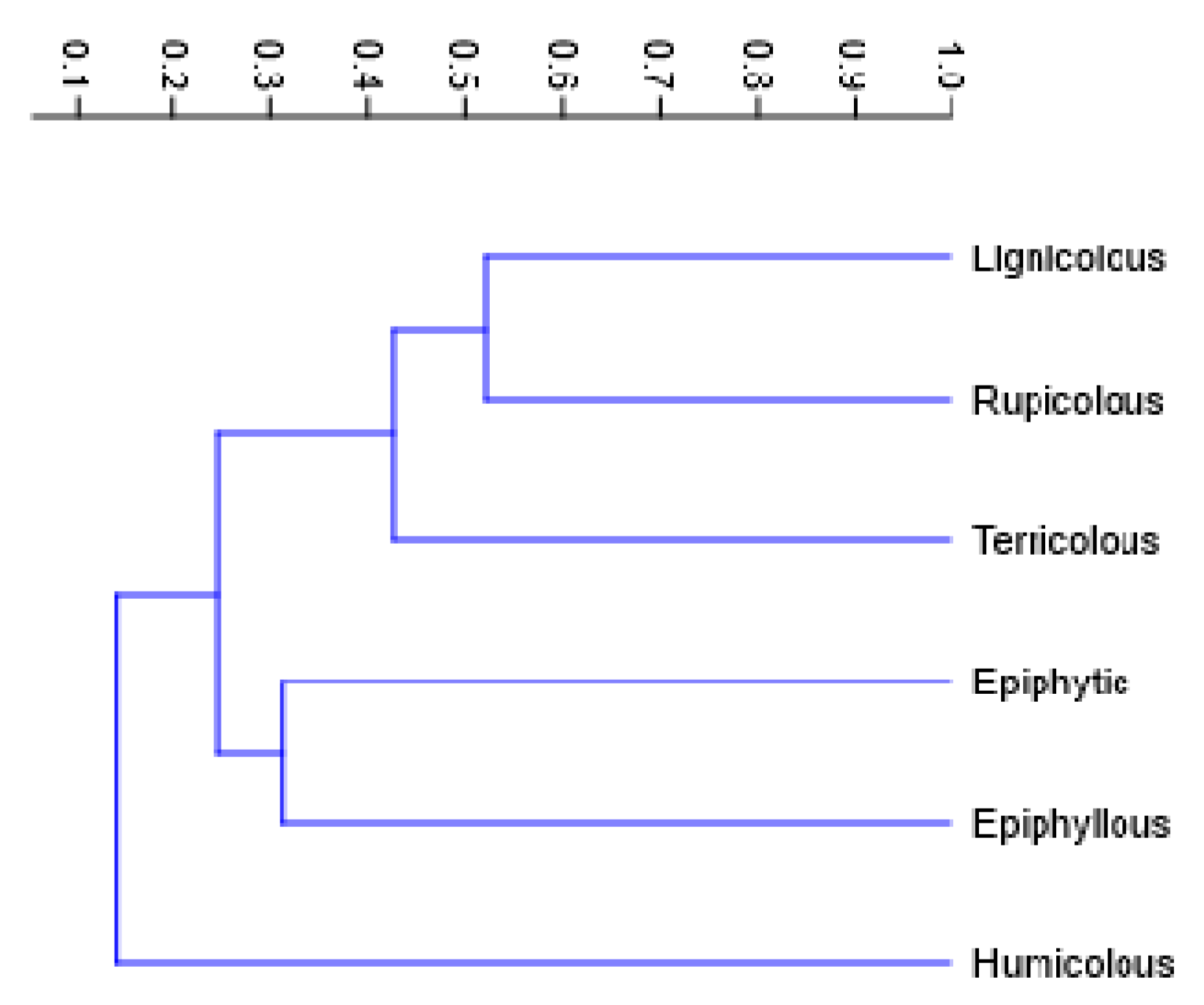

2.3. Substrate Specificity of Bryophyte Assemblages

3. Discussion

3.1. General Overview and Sampling Completeness

3.2. Altitudinal Gradients of Diversity and Compositional Turnover

3.3. Substrate Specificity and Ecological Differentiation

3.4. Biogeographical and Conservation Implications

3.5. Limitations and Perspectives

4. Methodology

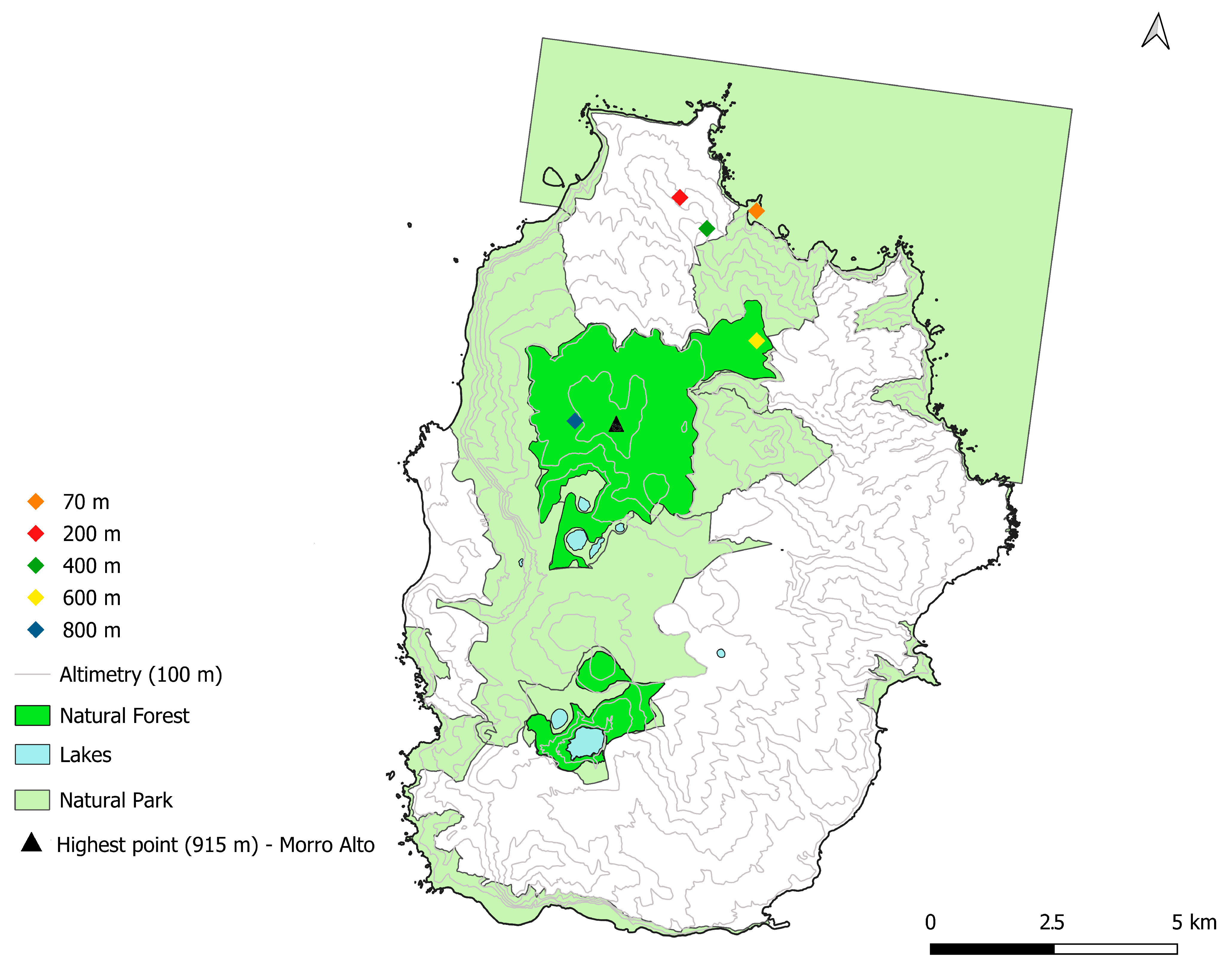

4.1. Study Area

4.1.1. Azores Archipelago

4.1.2. Flores Island

4.1.3. Sampling Design and Fieldwork Procedures

4.1.4. Fieldwork Locations

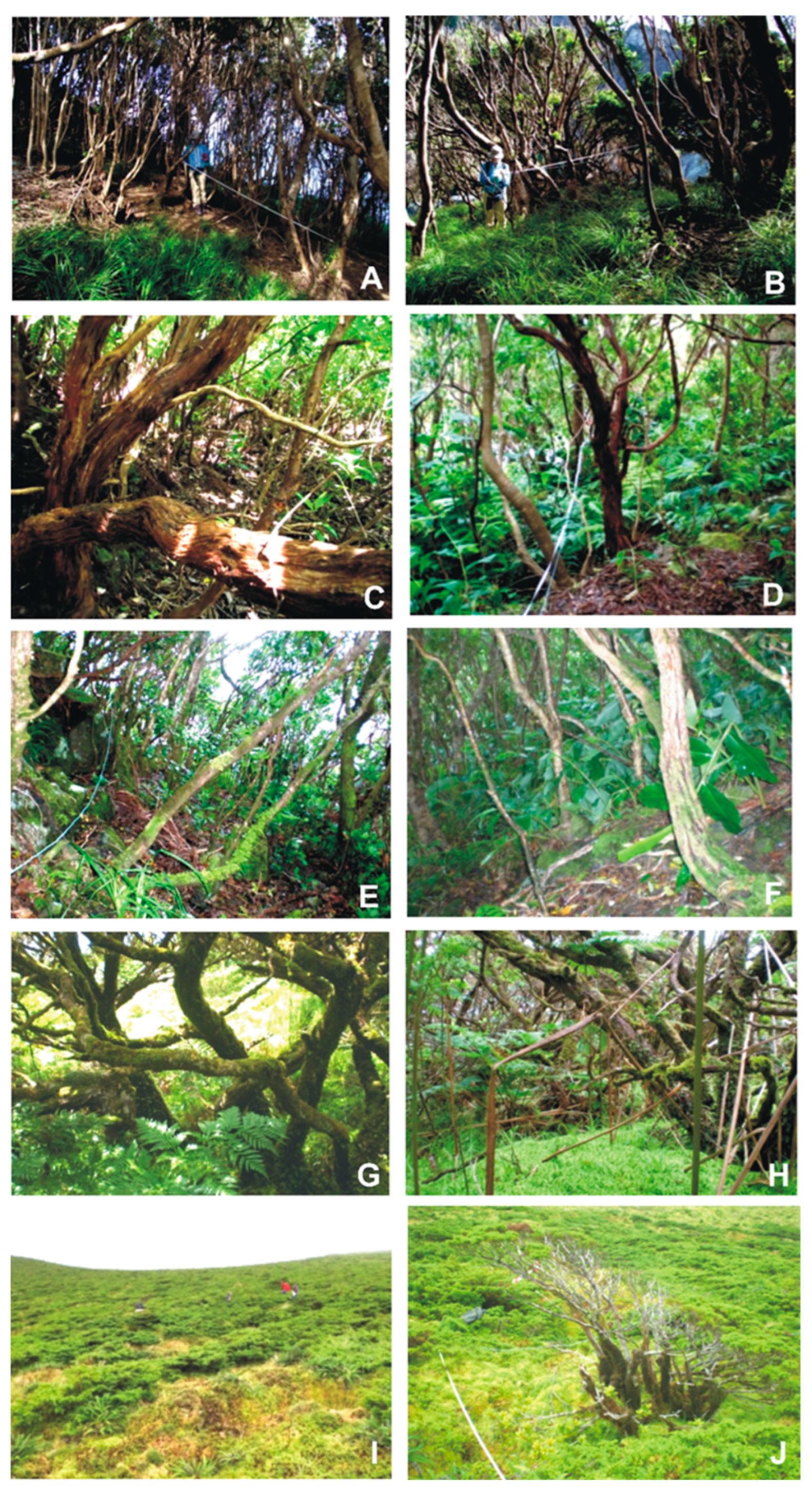

- Ponta do Ilhéu (70 m a.s.l.)—Vegetation at this lowland site is dominated by Picconia azorica (Tutin) Knobl. (Endemic), Pittosporum undulatum Vent. (Introduced/Invasive species), and Morella faya (Aiton) Wilbur. (Native). The forest canopy reaches an average height of 5.2 m. Bryophyte cover ranges from 5% to 25%, distributed across soil, rocks, and tree trunks (Figure 12A,B);

- Caminho para Ponta Delgada (200 m a.s.l.)—The forest includes species such as Erica azorica Hochst. ex Seub. (Endemic), Vaccinium cylindraceum Sm. (Endemic), Juniperus brevifolia (Hochst. ex Seub.) Antoine (Endemic), and Morella faya, alongside the invasive Pittosporum undulatum. The canopy reaches up to 5.8 m. Bryophytes are most abundant on rocky surfaces, with approximately 25% cover, and occur less frequently on soil and tree bark (Figure 12C,D);

- Outeiros (400 m a.s.l.)—This mid-elevation forest exhibits a higher canopy, reaching up to 6.2 m. However, approximately 50% of the vegetation is composed of Pittosporum undulatum, and large individuals of Hedychium gardnerianum Sheppard ex Ker-Gawl. (Introduced/Invasive species) are present. Native species such as Erica azorica, Picconia azorica, Laurus azorica (Seub.) Franco (Endemic), Morella faya, and Vaccinium cylindraceum occur with relative abundances ranging from 15% to 40%. Bryophyte cover is highest on tree trunks (~60%) but is also substantial on the forest floor (~40%) (Figure 12E,F);

- Ribeira do Cascalho (600 m)—This forested site, known locally as “Zimbral,” is dominated by Juniperus brevifolia, comprising approximately 90% of the canopy, which reaches a height of 3.9 m. Other species, including Vaccinium cylindraceum (30%), Ilex azorica Gand. (Endemic) (25%), Laurus azorica (15%), and Myrsine retusa Aiton (Endemic) (25%), are present at lower frequencies. Bryophyte cover is extensive, reaching approximately 80% on both soil and tree surfaces (Figure 12G,H);

- Morro Alto (800 m)—Located within a designated Nature Reserve, this site features high-altitude scrubland dominated by Juniperus brevifolia and Calluna vulgaris (L.) Hull (Native), with Struthiopteris spicant (L.) Weis (Native) also abundant. Vascular plants do not exceed 2 m in height. The bryophyte layer covers nearly 100% of the ground surface, predominantly composed of Sphagnum spp. Epiphytic bryophytes are also well represented, with average coverage reaching up to 30% (Figure 12I,J).

4.2. Study Taxa

4.2.1. Bryophytes

4.2.2. Bryophytes in the Azores

4.3. Identification and Categorization of Specimens

4.3.1. Taxonomic Framework

4.3.2. Biogeographic Framework

4.3.3. Conservation Framework

4.4. Sampling Completeness and Diversity Measurement

4.5. Altitudinal Gradient and Mid-Domain Effect Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Whittaker, R.J.; Triantis, K.A.; Ladle, R.J. A general dynamic theory of oceanic island biogeography. J. Biogeogr. 2008, 35, 977–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whittaker, R.J.; Fernandez-Palácios, J.M. Island Biogeography: Ecology, Evolution, and Conservation, 2nd ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Kier, G.; Kreft, H.; Lee, T.M.; Jetz, W.; Ibisch, P.L.; Nowicki, C.; Mutke, J.; Barthlott, W. A global assessment of endemism and species richness across island and mainland regions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 9322–9327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinbauer, M.J.; Otto, R.; Naranjo-Cigala, A.; Beierkuhnlein, C.; Fernández-Palacios, J.M. Increase of island endemism with altitude—Speciation processes on oceanic islands. Ecography 2012, 35, 23–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levin, S.A. The problem of pattern and scale in ecology: The Robert H. MacArthur Award Lecture. Ecology 1992, 73, 1943–1967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sax, D.F.; Gaines, S.D. Species invasions and extinction: The future of native biodiversity on islands. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 11490–11497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Triantis, K.A.; Guilhaumon, F.; Whittaker, R.J. The island species–area relationship: Biology and statistics. J. Biogeogr. 2012, 39, 215–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lomolino, M.V. Elevation gradients of species-density: Historical and prospective views. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 2001, 10, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahbek, C. The elevational gradient of species richness: A uniform pattern? Ecography 1995, 18, 200–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aranda, S.C.; Gabriel, R.; Borges, P.A.; Santos, A.M.; de Azevedo, E.B.; Patiño, J.; Lobo, J.M. Geographical, temporal and environmental determinants of bryophyte species richness in the Macaronesian Islands. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e101786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ah-Peng, C.; Wilding, N.; Kluge, J.; Descamps-Julien, B.; Bardat, J.; Chuah-Petiot, M.; Hedderson, T.A. Bryophyte diversity and range size distribution along two altitudinal gradients: Continent vs. island. Acta Oecologica 2012, 42, 58–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coelho, M.C.M.; Gabriel, R.; Hespanhol, H.; Borges, P.A.V.; Ah-Peng, C. Bryophyte diversity along an elevational gradient on Pico Island (Azores, Portugal). Diversity 2021, 13, 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahbek, C. The role of spatial scale and the perception of large-scale species-richness patterns. Ecol. Lett. 2005, 8, 224–239. [Google Scholar]

- Tassin, J.; Derroire, G.; Rivière, J.-N. Gradient altitudinal de la richesse spécifique et de l’endémicité de la flore ligneuse indigène à l’île de La Réunion (archipel des Mascareignes). Acta Bot. Gall. 2004, 151, 181–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ah-Peng, C.; Chuah-Petiot, M.; Descamps-Julien, B.; Bardat, J.; Staménoff, P.; Strasberg, D. Bryophyte diversity and distribution along an altitudinal gradient on a lava flow in La Réunion. Divers. Distrib. 2007, 13, 654–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puglisi, M.; Sciandrello, S. Bryophyte Diversity and Distribution Patterns along Elevation Gradients of the Mount Etna (Sicily), the Highest Active Volcano in Europe. Plants 2023, 12, 2655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maul, K.; Wei, Y.M.; Iskandar, E.A.P.; Chantanaorrapint, S.; Ho, B.C.; Quandt, D.; Kessler, M. Liverworts show a globally consistent mid-elevation richness peak. Ecol. Evol. 2023, 13, e9862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coelho, M.C.M.; Elias, R.B.; Kluge, J.; Pereira, F.; Henriques, D.S.G.; Aranda, S.C.; Borges, P.A.V.; Ah-Peng, C.; Gabriel, R. Vascular plants on Pico Island transect. Long-term monitoring across elevational gradients (II): Vascular plants on Pico Island (Azores) transect. Arquipelago Life Mar. Sci. 2016, 33, 21–44. [Google Scholar]

- Gabriel, R.; Morgado, L.N.; Borges, P.A.V.; Coelho, M.C.M.; Aranda, S.C.; Henriques, D.S.G.; Sérgio, C.; Hespanhol, H.; Pereira, F.; Sim-Sim, M.; et al. The MOVECLIM–AZORES project: Bryophytes from Pico Island along an elevation gradient. Biodivers. Data J. 2024, 12, e117890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabriel, R.; Morgado, L.N.; Henriques, D.; Coelho, M.C.M.; Hernández-Hernández, R.; Borges, P.A.V. The MOVECLIM–AZORES project: Bryophytes from Terceira Island along an elevation gradient. Biodivers. Data J. 2024, 12, e131935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henriques, D.S.; Elias, R.B.; Coelho, M.C.; Hernández, R.H.; Pereira, F.; Gabriel, R. Long-term monitoring across elevational gradients (III): Vascular plants on Terceira Island (Azores) transect. Arquipelago Life Mar. Sci. 2017, 34, 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Gabriel, R.; Coelho, M.C.M.; Henriques, D.S.G.; Borges, P.A.V.; Elias, R.B.; Kluge, J.; Ah-Peng, C. Long-term monitoring across elevational gradients to assess ecological hypotheses: A description of standardized sampling methods in oceanic islands and first results. Arquipelago Life Mar. Sci. 2014, 31, 45–67. Available online: https://repositorio.uac.pt/ (accessed on 22 October 2025).

- Borges, P.A.V.; Santos, A.M.C.; Elias, R.B.; Gabriel, R. The Azores Archipelago: Biodiversity erosion and conservation biogeography. In Encyclopedia of the World’s Biomes—Earth Systems and Environmental Sciences; Scott, E., Ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019; pp. 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norder, S.J.; de Lima, R.F.; de Nascimento, L.; Lim, J.Y.; Fernández-Palacios, J.M.; Romeiras, M.M.; Elias, R.B.; Cabezas, F.J.; Catarino, L.; Ceríaco, L.M.; et al. Global change in microcosms: Environmental and societal predictors of land cover change on the Atlantic Ocean Islands. Anthropocene 2020, 30, 100242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elias, R.B.; Gil, A.; Silva, L.; Fernández-Palacios, J.M.; Azevedo, E.B.; Reis, F. Natural zonal vegetation of the Azores Islands: Characterization and potential distribution. Phytocoenologia 2016, 46, 107–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azevedo, J.M.M.; Ferreira, M.R.P. The volcanotectonic evolution of Flores Island, Azores (Portugal). J. Volcanol. Geotherm. Res. 2006, 156, 90–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allorge, P.; Allorge, V. Les étages de végétation muscinale aux îles Açores et leurs éléments. Mém. Soc. Biogéogr. 1946, 8, 369–386. [Google Scholar]

- GBIF Occurrence Download. Available online: https://doi.org/10.15468/943by2 (accessed on 22 October 2025).

- Gabriel, R.; Morgado, L.N.; Borges, P.A.V.; Poponessi, S.; Henriques, D.S.G.; Coelho, M.C.M.; Silveira, G.M.; Pereira, F. Dataset on bryophyte species distribution across an elevational gradient on Flores Island. Biodivers. Data J. 2025, 13, e165664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gabriel, R.; Sjögren, E.; Schumacker, R.; Sérgio, C.; Aranda, S.; Claro, D.; Homem, N.; Martins, B. List of bryophytes (Anthocerotophyta, Marchantiophyta, Bryophyta). In A List of the Terrestrial and Marine Biota from the Azores; Borges, P.A.V., Costa, A., Cunha, R., Gabriel, R., Gonçalves, V., Martins, A.F., Melo, I., Parente, M., Raposeiro, P., Rodrigues, P., Eds.; Princípia: Cascais, Portugal, 2010; pp. 99–115. [Google Scholar]

- PBA. Portal da Biodiversidade dos Açores|Azorean Biodiversity Portal. 2025. Available online: https://azoresbioportal.uac.pt (accessed on 22 October 2025).

- Hodgetts, N.; Cálix, M.; Englefield, E.; Fettes, N.; Criado, M.G.; Patin, L.; Nieto, A.; Bergamini, A.; Bisang, I.; Baisheva, E.; et al. A Miniature World in Decline: European Red List of Mosses, Liverworts and Hornworts, 1st ed.; IUCN: Brussels, Belgium, 2019; Volume 1, 100p. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sjögren, E. Bryosociological Investigations on the Islands of Faial, Pico, S. Jorge, Flores. In LIFE Project Report: Inventário e Cartografia da Vegetação e Flora Natural dos Açores (LIFE B4-3200/94/764); Universidade dos Açores: Horta, Portugal; Uppsala, Sweden, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Borges, P.A.V.; Cardoso, P.; Kreft, H.; Whittaker, R.J.; Fattorini, S.; Emerson, B.C.; Gil, A.; Gillespie, R.G.; Matthews, T.J.; Santos, A.M.C.; et al. Global Island Monitoring Scheme (GIMS): A proposal for the long-term coordinated survey and monitoring of native island forest biota. Biodivers. Conserv. 2018, 27, 2567–2586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuster, R.M. Ecology, reproductive biology and dispersal of Hepaticae in the tropics. J. Hattori Bot. Lab. 1988, 64, 237–269. [Google Scholar]

- Frahm, J.-P.; Pocs, T.; O’sHea, B.; Koponen, T.; Piippo, S.; Enroth, J.; Rao, P.; Fang, Y.-M. Manual of Tropical Bryology. Bryophyt. Divers. Evol. 2003, 23, 1–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, J.G.; Fischer, M.; Pócs, T. Bryoflora and landscapes of the eastern Andes of central Peru: I. Liverworts of the El Sira Communal Reserve. Acta Biol. Plant. Agriensis 2016, 4, 3–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sjögren, E. Epiphyllous bryophytes in the Azores Islands. Arquipel. Life Mar. Sci. 1997, 15, 1–49. [Google Scholar]

- Gabriel, R.; Bates, J.W. Bryophyte community composition and habitat specificity in the natural forests of Terceira, Azores. Plant Ecol. 2005, 177, 125–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aranda, S.C.; Gabriel, R.; Borges, P.A.V.; Lobo, J.M. Assessing the completeness of bryophytes inventories: An oceanic island as a case study (Terceira, Azorean archipelago). Biodivers. Conserv. 2010, 19, 2469–2484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henriques, D.S.; Borges, P.A.V.; Ah-Peng, C.; Gabriel, R. Mosses and liverworts show contrasting elevational distribution patterns in an oceanic island (Terceira, Azores): The influence of climate and space. J. Bryol. 2016, 38, 183–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keppel, G.; Van Niel, K.P.; Wardell-Johnson, G.W.; Yates, C.J.; Byrne, M.; Mucina, L.; Schut, A.G.T.; Hopper, S.D.; Franklin, S.E. Refugia: Identifying and understanding safe havens for biodiversity under climate change. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 2012, 21, 393–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, M.T.; Cardoso, P.; Borges, P.A.V.; Gabriel, R.; Azevedo, E.B.; Reis, F.; Araújo, M.B.; Elias, R.B. Effects of climate change on the distribution of indigenous species in oceanic islands (Azores). Clim. Change 2016, 138, 603–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patiño, J.; Mateo, R.; Zanatta, F.; Marquet, A.; Aranda, S.C.; Borges, P.A.V.; Dirkse, G.; Gabriel, R.; Gonzalez-Mancebo, J.M.; Guisan, A.; et al. Climate threat on the Macaronesian endemic bryophyte flora. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 29156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grytnes, J.-A.; McCain, C.M. Elevational trends in biodiversity. In Encyclopedia of Biodiversity, 2nd ed.; Levin, S.A., Ed.; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 2013; pp. 149–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanders, N.J.; Rahbek, C. The patterns and causes of elevational diversity gradients. Ecography 2012, 35, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Hernández, R.; Borges, P.A.V.; Gabriel, R.; Rigal, F.; Ah-Peng, C.; González-Mancebo, J.M. Scaling α- and β-diversity: Bryophytes along an elevational gradient on a subtropical oceanic island (La Palma, Canary Islands). J. Veg. Sci. 2017, 28, 1209–1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, A.; Collart, F.; Sim Sim, M.; Patiño, J. Ecological drivers of taxonomic, functional, and phylogenetic diversity of bryophytes in an oceanic island. Ecol. Evol. 2024, 14, e70023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gradstein, S.R.; Griffin, D., III; Morales, M.I.; Nadkarni, N.M. Diversity and habitat differentiation of mosses and liverworts in the cloud forest of Monteverde, Costa Rica. Caldasia 2001, 23, 203–212. [Google Scholar]

- Halpern, C.B.; Dovčiak, M.; Urgenson, L.S.; Evans, S.A. Substrates mediate responses of forest bryophytes to a gradient in overstory retention. Can. J. For. Res. 2014, 44, 855–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Niu, S.; Li, P.; Jia, H.; Wang, H.; Ye, Y.; Yuan, Z. Stand structure and substrate diversity as two major drivers for bryophyte distribution in a temperate montane ecosystem. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weigelt, P.; Jetz, W.; Kreft, H. Bioclimatic and physical characterization of the world’s islands. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 15307–15312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rios, E.B.; Sadler, J.; Graham, L.; Matthews, T.J. Species distribution models and island biogeography: Challenges and prospects. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2024, 51, e02943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forjaz, V.H. Atlas Básico dos Açores; Observatório Vulcanológico e Geotérmico dos Açores (OVGA): Ponta Delgada, Portugal, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Ramalho, R.S.; Helffrich, G.; Madeira, J.; Cosca, M.; Thomas, C.; Quartau, R.; Hipólito, A.; Rovere, A.; Hearty, P.J.; Ávila, S.P. Emergence and evolution of Santa Maria Island (Azores)—The conundrum of uplifted islands revisited. Geol. Soc. Am. Bull. 2017, 129, 372–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, A.C.G.; Hildenbrand, A.; Marques, F.O.; Sibrant, A.L.R.; Santos de Campos, A. Catastrophic flank collapses and slumping in Pico Island during the last 130 kyr (Pico-Faial ridge, Azores Triple Junction). J. Volcanol. Geotherm. Res. 2015, 302, 33–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azevedo, E.B.; Pereira, L.S.; Itier, B. Modelling the local climate in island environments: Water balance applications. Agric. Water Manag. 1999, 40, 393–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azevedo, E.B.; Rodrigues, M.C.; Fernandes, J.F. O clima dos Açores. Climatologia: Introdução. In Atlas Básico dos Açores; Forjaz, V.H., Ed.; Observatório Vulcanológico e Geotérmico dos Açores: Ponta Delgada, Portugal, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Dias, E. Vegetação Natural dos Açores: Ecologia e Sintaxonomia das Florestas Naturais. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidade dos Açores, Angra do Heroísmo, Portugal, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Dias, E.; Fontes, J.; Pereira, D.; Mendes, C.; Melo, C. Modelo espacial de avaliação da importância da floresta no ordenamento do território, em função da precipitação oculta. In IV Jornadas Forestales de la Macaronesia; La Palma: Islas Canarias, Spain, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Pereira, D.; Mendes, C.; Dias, E. The potential of peatlands in global climate change mitigation: A case study of Terceira and Flores Islands (Azores, Portugal) hydrologic services. SN Appl. Sci. 2022, 4, 184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borges, P.A.V.; Costa, A.; Cunha, R.; Gabriel, R.; Gonçalves, V.; Martins, A.F.; Melo, I.; Parente, M.; Raposeiro, P.; Santos, R.S.; et al. (Eds.) Listagem dos Organismos Terrestres e Marinhos dos Açores/A List of the Terrestrial and Marine Biota from the Azores, bilingual ed.; Princípia: Cascais, Portugal, 2010; 432p, ISBN 9789898131751. [Google Scholar]

- Fuentes-Sánchez, A.; Dentinho, T.P.; Arroz, A.M.; Gabriel, R. Urban sustainability: Q-method application to five cities of the Azorean Islands. Rev. Port. Estud. Reg. 2021, 57, 33–56. [Google Scholar]

- Chester, D.; Duncan, A.; Coutinho, R.; Wallenstein, N.; Branca, S. Communicating information on eruptions and their impacts from the earliest times until the late twentieth century. In Observing the Volcano World; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 419–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrade, M.; Pimentel, A.; Ramalho, R.; Kutterolf, S.; Hernández, A. The recent volcanism of Flores Island (Azores): Stratigraphy and eruptive history of Funda Volcanic System. J. Volcanol. Geotherm. Res. 2022, 432, 107706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hipólito, M. Ilha das Flores: Reservas da Biosfera dos Açores. Available online: https://siaram.azores.gov.pt (accessed on 28 April 2025).

- Elias, R.B.; Dias, E. Effects of landslides on the mountain vegetation of Flores Island, Azores. J. Veg. Sci. 2009, 20, 706–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SREA. Censos 2021: Principais Resultados Preliminares. Informação Estatística, Estatística dos Açores. 2021. Available online: https://srea.azores.gov.pt (accessed on 29 April 2025).

- van der Maarel, E. Transformation of cover-abundance values for appropriate numerical treatment-Alternatives to the proposals by Podani. J. Veg. Sci. 2007, 18, 767–770. [Google Scholar]

- Silva, L.; Moura, M.; Schaefer, H.; Rumsey, F.; Dias, E.F. Lista das Plantas Vasculares (Tracheobionta)|List of Vascular Plants (Tracheobionta). In A List of the Terrestrial and Marine Biota from the Azores; Borges, P.A.V., Costa, A., Cunha, R., Gabriel, R., Gonçalves, V., Martins, A.F., Melo, I., Parente, M., Raposeiro, P., Rodrigues, P., Eds.; Princípia: Cascais, Portugal, 2010; pp. 117–146. [Google Scholar]

- Grime, J.P.; Rincon, E.R.; Wickerson, B.E. Bryophytes and plant strategy theory. Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 1990, 104, 175–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Söderström, L.; During, H.J. Bryophyte rarity viewed from the perspectives of life history strategy and metapopulation dynamics. J. Bryol. 2005, 27, 261–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coelho, M.C.M.; Gabriel, R.; Ah-Peng, C. Characterizing and quantifying water content in 14 species of bryophytes present in Azorean native vegetation. Diversity 2023, 15, 295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coelho, M.C.M.; Gabriel, R.; Ah-Peng, C. Seasonal hydration status of common bryophyte species in Azorean native vegetation. Plants 2023, 12, 2931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goffinet, B.; Shaw, A.J. (Eds.) Bryophyte Biology, 2nd ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2009; 565p. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elias, R.B.; Rodrigues, A.F.F.; Gabriel, R. Guia Prático da Flora Nativa dos Açores/Field Guide of Azorean Native Flora; Gabriel, R., Borges, P.A.V., Eds.; Instituto Açoriano de Cultura: Angra do Heroísmo, Portugal, 2022; Volume 1, 519p, ISBN 9789898225740. [Google Scholar]

- Costa, D.P.; Sérgio, C. Tropical Atlantic oceanic islands and archipelagos: Physical structures, plant diversity, and affinities of the bryofloras of northern and southern islands. Res. Sq. 2023. preprint. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodgetts, N.; Lockhart, N. Checklist and Country Status of European Bryophytes—Update 2020. Irish Wildl. Man. 2020, 123, 1–214. [Google Scholar]

- Sérgio, C.; Sim-Sim, M.; Fontinha, S.; Figueira, R. Os briófitos (Bryophyta) dos arquipélagos da Madeira e das Selvagens. In Listagem dos Fungos, Flora e Fauna Terrestres dos Arquipélagos da Madeira e Selvagens Borges; Princípia: Cascais, Portugal, 2008; pp. 123–156. [Google Scholar]

- Gabriel, R.; Homem, N.; Couto, A.; Aranda, S.C.; Borges, P.A.V. Azorean bryophytes: A preliminary review of rarity patterns. Açoreana 2011, 7, 149–206. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, A.J.E.; Smith, R. The Moss Flora of Britain and Ireland; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casas, C.; Brugués, M.; Cros, R.M.; Sérgio, C. Handbook of Mosses of the Iberian Peninsula and the Balearic Islands: Illustrated Keys to Genera and Species; Institut d’Estudis Catalans: Barcelona, Spain, 2006; ISBN 847283865X. [Google Scholar]

- Paton, J.A. The Liverwort Flora of the British Isles; Harley Books: Colchester, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Casas, C.; Brugués, M.; Cros, R.M.; Sérgio, C.; Infante, M. Handbook of Liverworts and Hornworts of the Iberian Peninsula and the Balearic Islands: Illustrated Keys to Genera and Species; Institut d’Estudis Catalans: Barcelona, Spain, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Schumacker, R.; Váňa, J. Identification Keys to the Liverworts and Hornworts of Europe and Macaronesia, 2nd ed.; Station Scientifique des Hautes-Fagnes: Waimes, Belgium, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Atherton, I.; Bosanquet, S.; Lawley, M. (Eds.) Mosses and Liverworts of Britain and Ireland: A Field Guide; British Bryological Society: Plymouth, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Lüth, M. Mosses of Europe—A Photographic Flora; Selbstverlag: Freiburg, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- IUCN. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species, Version 2025-2. 2025. Available online: https://www.iucnredlist.org (accessed on 23 October 2025).

- Hortal, J.; Borges, P.A.; Gaspar, C. Evaluating the performance of species richness estimators: Sensitivity to sample grain size. J. Anim. Ecol. 2006, 75, 274–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, M.O. Diversity and Evenness: A Unifying Notation and Its Consequences. Ecology 1973, 54, 427–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jost, L. Entropy and diversity. Oikos 2006, 113, 363–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chao, A.; Chiu, C.H.; Jost, L. Unifying species diversity, phylogenetic diversity, functional diversity, and related similarity and differentiation measures through hill numbers. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 2014, 45, 297–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krebs, C.J. Ecological Methodology, 2nd ed.; Harper Collins Publishers: New York, NY, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Berger, W.H.; Parker, F.L. Diversity of planktonic foraminifera in deep-sea sediments. Science 1970, 168, 1345–1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magurran, A.E. Measuring Biological Diversity; Blackwell Science Ltd.: Malden, MA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Jost, L. Partitioning diversity into independent alpha and beta components. Ecology 2007, 88, 2427–2439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whittaker, R.J.; Willis, K.J.; Field, R. Scale and species richness: Towards a general, hierarchical theory of species diversity. J. Biogeogr. 2001, 28, 453–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammer, Ø.; Harper, D.A.T.; Ryan, P.D. Past: Paleontological Statistics software package for education and data analysis. Palaeontol. Electron. 2001, 4, 9. Available online: https://palaeo-electronica.org/2001_1/past/past.pdf (accessed on 23 October 2025).

| Plot Code | Locality | Elevation (m a.s.l.) | Slope (Degrees) | Exposure (Degrees) | Latitude (Decimal °) | Longitude (Decimal °) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FLO_0070_P1 | Ponta do Ilhéu | 70 | 15 | 280 | 39.50633 | −31.19453 |

| FLO_0070_P2 | 77 | 18 | 107 | 39.50622 | −31.19461 | |

| FLO_0200_P1 | Caminho para Ponta Delgada | 249 | 35 | 141 | 39.50689 | −31.21286 |

| FLO_0200_P2 | 266 | 32 | 14 | 39.50661 | −31.21275 | |

| FLO_0400_P1 | Outeiros | 399 | 40 | 81 | 39.50192 | −31.20558 |

| FLO_0400_P2 | 399 | 41 | 54 | 39.50183 | −31.20558 | |

| FLO_0600_P1 | Ribeira do Cascalho | 649 | 5 | 90 | 39.48281 | −31.19042 |

| FLO_0600_P2 | 648 | 8 | 176 | 39.48267 | −31.19033 | |

| FLO_0800_P1 | Morro Alto | 833 | 14 | 278 | 39.46319 | −31.22594 |

| FLO_0800_P2 | 833 | 15 | 283 | 39.46325 | −31.22600 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gabriel, R.; Morgado, L.N.; Poponessi, S.; Henriques, D.S.G.; Coelho, M.C.M.; Silveira, G.M.; Borges, P.A.V. Diversity and Distribution of Bryophytes Along an Altitudinal Gradient on Flores Island (Azores, Portugal). Plants 2025, 14, 3766. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14243766

Gabriel R, Morgado LN, Poponessi S, Henriques DSG, Coelho MCM, Silveira GM, Borges PAV. Diversity and Distribution of Bryophytes Along an Altitudinal Gradient on Flores Island (Azores, Portugal). Plants. 2025; 14(24):3766. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14243766

Chicago/Turabian StyleGabriel, Rosalina, Leila Nunes Morgado, Silvia Poponessi, Débora S. G. Henriques, Márcia C. M. Coelho, Gabriela M. Silveira, and Paulo A. V. Borges. 2025. "Diversity and Distribution of Bryophytes Along an Altitudinal Gradient on Flores Island (Azores, Portugal)" Plants 14, no. 24: 3766. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14243766

APA StyleGabriel, R., Morgado, L. N., Poponessi, S., Henriques, D. S. G., Coelho, M. C. M., Silveira, G. M., & Borges, P. A. V. (2025). Diversity and Distribution of Bryophytes Along an Altitudinal Gradient on Flores Island (Azores, Portugal). Plants, 14(24), 3766. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14243766