A Polycistronic tRNA-amiRNA System Reveals the Antiviral Roles of NbAGO1a/1b/2 Against Soybean mosaic virus Infection

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

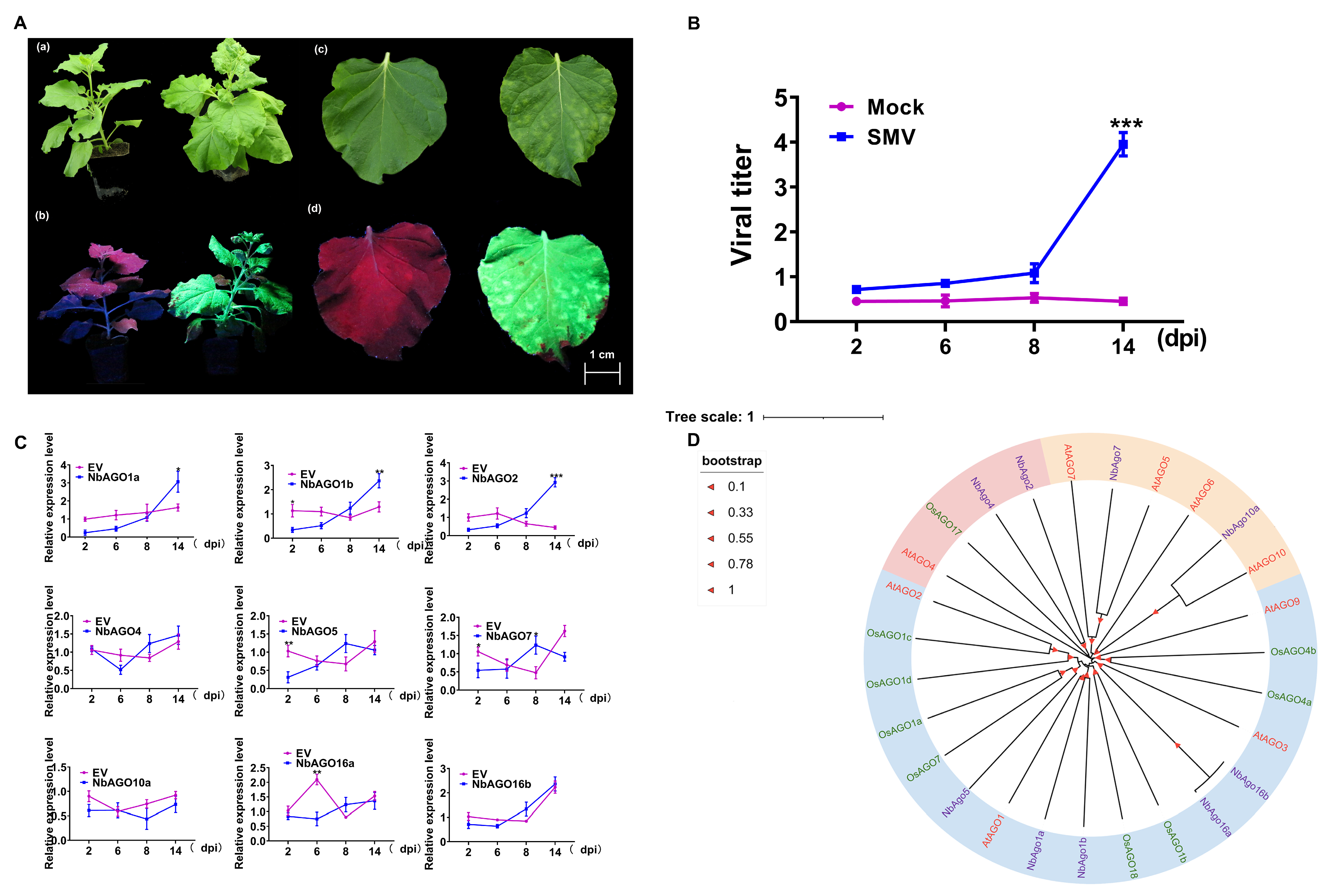

2.1. Symptoms of SMV-GFP Infection and Expression Response of NbAGOs Genes in Nicotiana benthamiana

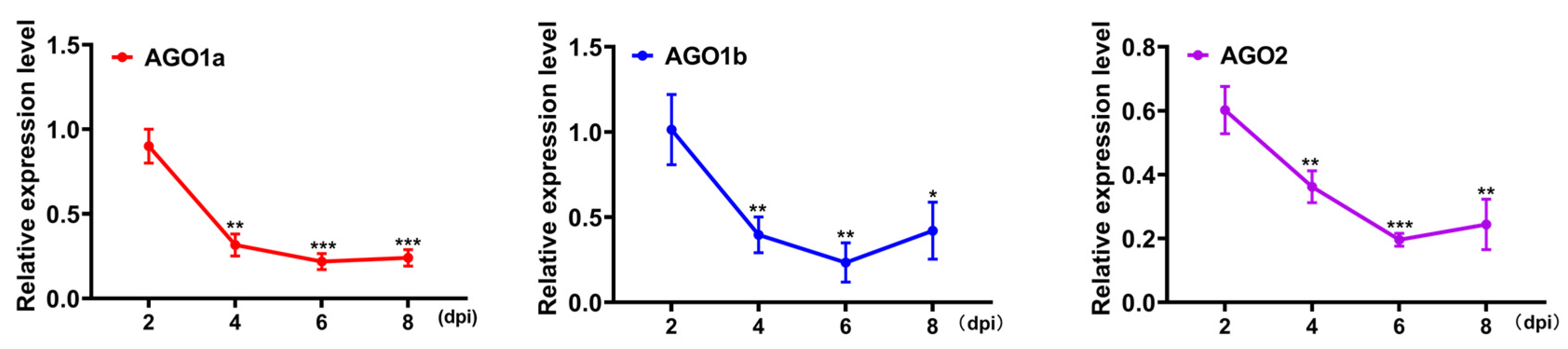

2.2. Transient Silencing of Target Genes Using Specific amiRNA in N. benthamiana

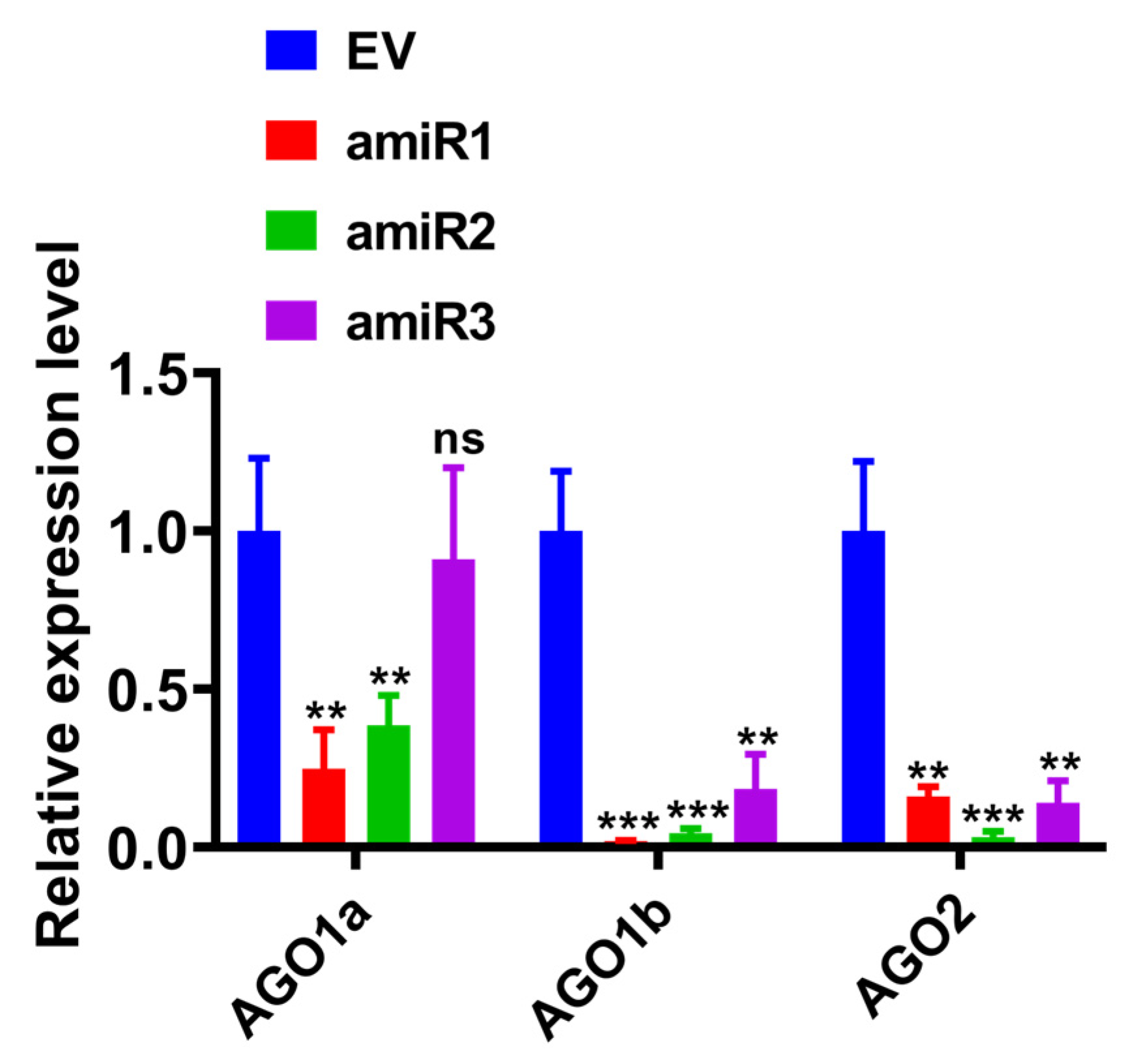

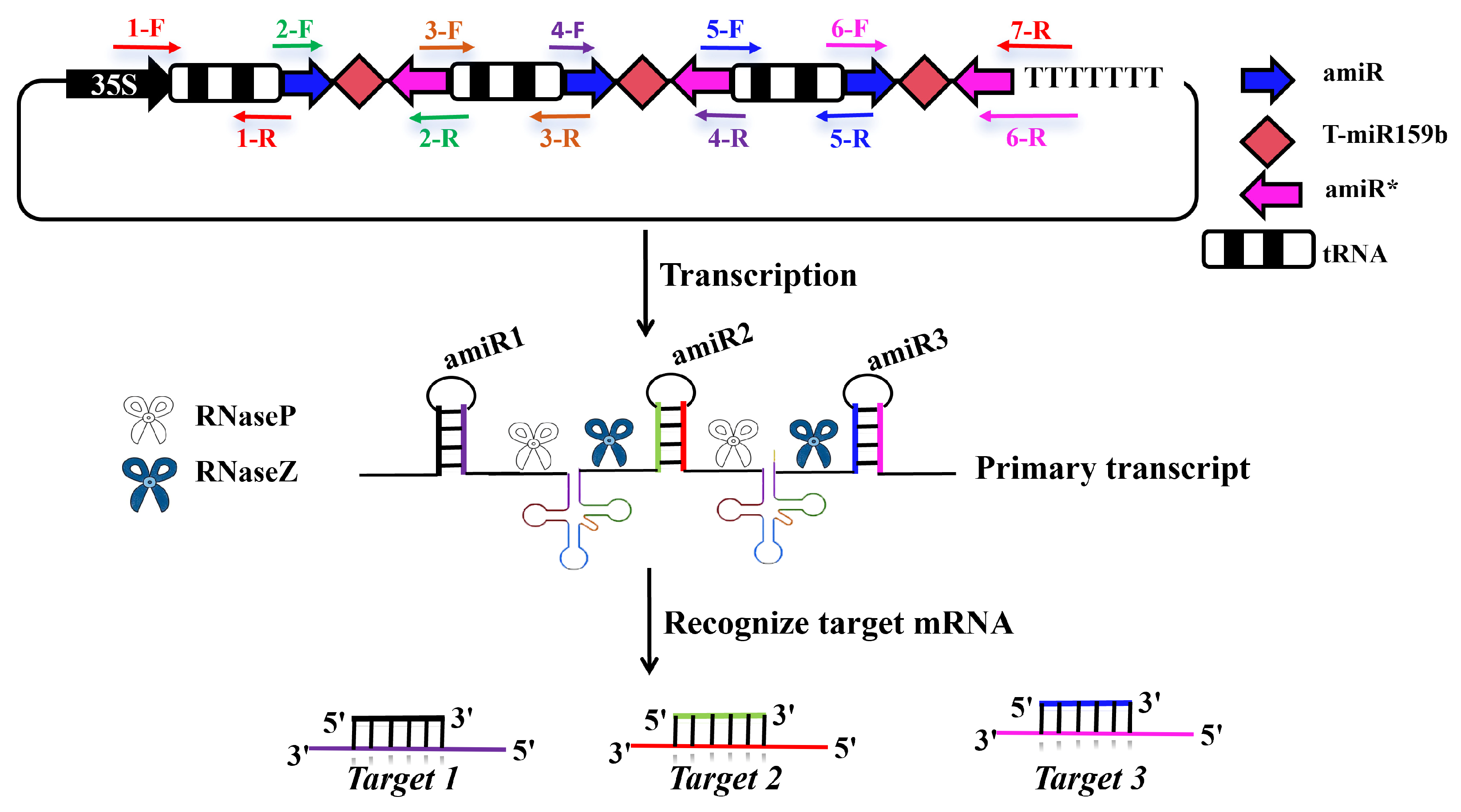

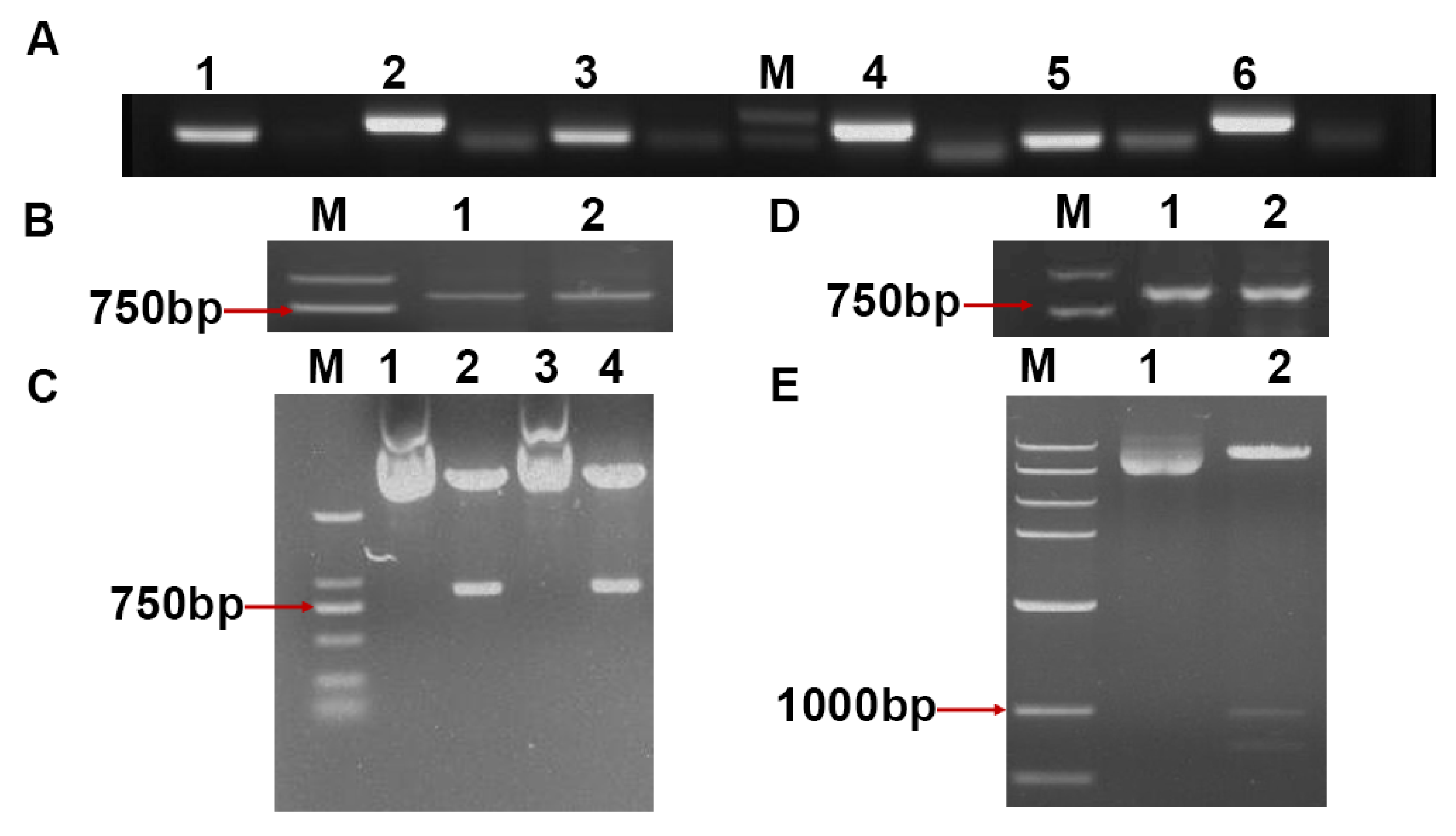

2.3. Constructing AGO Gene-Specific PTA Expression Cassettes of N. benthamiana

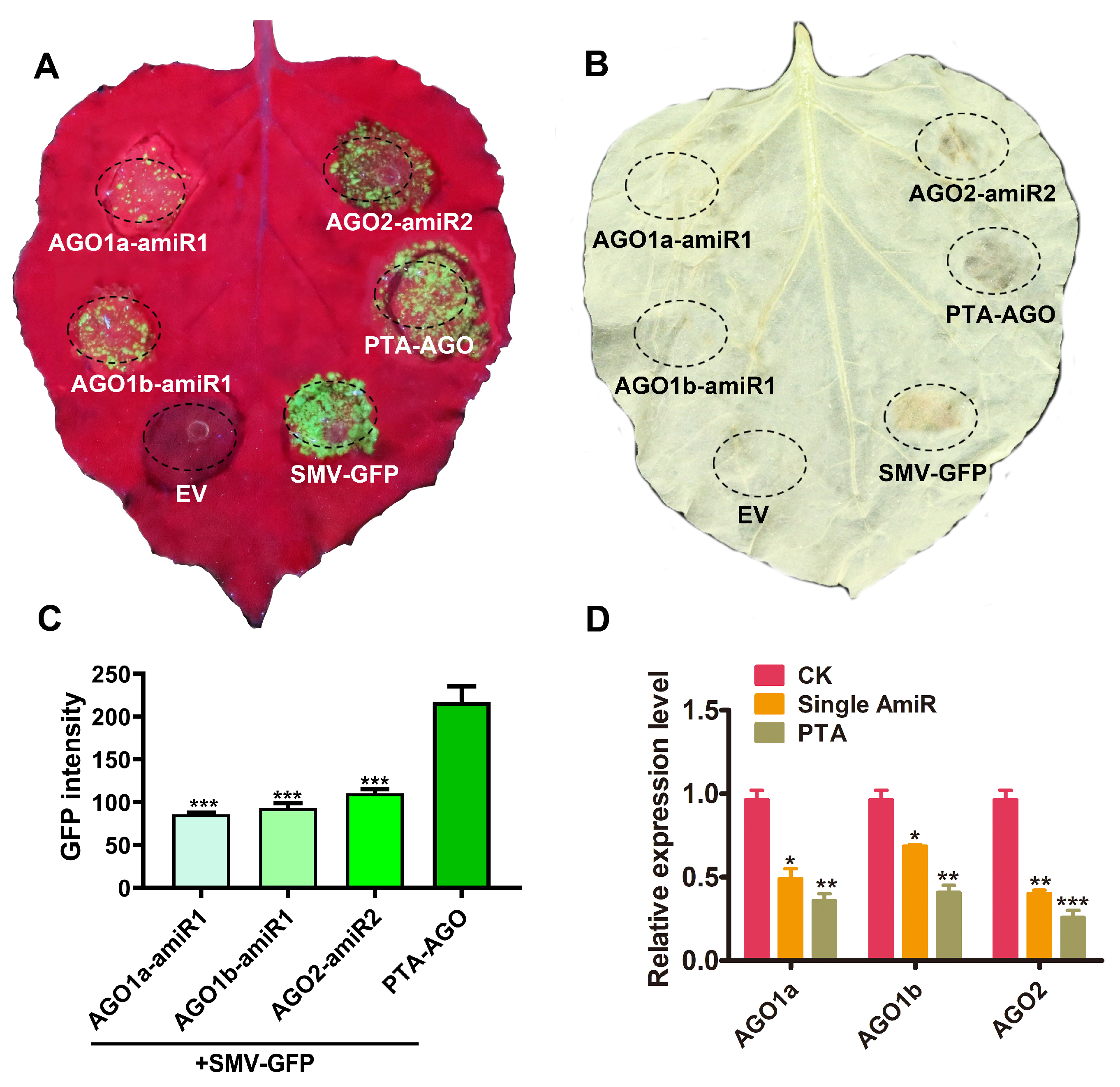

2.4. Influence of PTA Expression Cassettes with AGOs Gene Specificity on SMV Resistance

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Cultivation and Agents

4.2. Construction of the Target Gene Recombinant Vector Based on amiRNA

4.3. Assembly and Transient Assay of PTA Expression Cassettes in N. benthamiana

4.4. RT-qPCR Analysis to Measure the Expression Level of Target Genes

4.5. Quantification of GFP Fluorescence Brightness

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Li, F.; Li, X.; Zhao, S.; Pan, F.; Li, Z.; Hao, Y.; He, J.; Wang, A.; Kormelink, R.; Zhou, X. Antiviral RNA interference in plants: Increasing complexity and integration with other biological processes. Plant Commun. 2025, 26, 101490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.; Shahbaz, M.; Ölmez, F.; Fatima, N.; Umar, U.U.D.; Ali, M.A.; Akram, M.; Seelan, J.S.S.; Baloch, F.S. RNA interference: A promising biotechnological approach to combat plant pathogens, mechanism and future prospects. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2024, 40, 339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betti, F.; Ladera-Carmona, M.J.; Weits, D.A.; Ferri, G.; Iacopino, S.; Novi, G.; Svezia, B.; Kunkowska, A.B.; Santaniello, A.; Piaggesi, A.; et al. Exogenous miRNAs induce post-transcriptional gene silencing in plants. Nat. Plants 2021, 7, 379–1388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morel, J.B.; Godon, C.; Mourrain, P.; Beclin, C.; Boutet, S.; Feuerbach, F.; Proux, F.; Vaucheret, H. Fertile hypomorphic ARGONAUTE (ago1) mutants impaired in post-transcriptional gene silencing and virus resistance. Plant Cell 2002, 14, 629–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, X.; Qi, Y. RNAi in Plants: An Argonaute-Centered View. Plant Cell 2016, 28, 272–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, L.; Zhang, Q.; Zhou, H.; Ni, F.; Wu, X.; Qi, Y. Rice MicroRNA Effector Complexes and Targets. Plant Cell 2009, 21, 3421–3435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Yang, S.J.; Yin, X.X.; Yan, X.L.; Hassan, B.; Fan, J.; Yan, L.; Wang, W.M. ARGONAUTE 1: A node coordinating plant disease resistance with growth and development. Phytopathol. Res. 2023, 5, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sablok, G.; Pérez-Quintero, A.L.; Hassan, M.; Tatarinova, T.V.; López, C. Artificial microRNAs (amiRNAs) engineering—On how microRNA-based silencing methods have affected current plant silencing research. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2011, 406, 315–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kotowska-Zimmer, A.; Pewinska, M.; Olejniczak, M. Artificial miRNAs as therapeutic tools: Challenges and opportunities. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. RNA 2021, 12, e1640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bao, W.; Li, A.; Zhang, Y.; Diao, P.; Zhao, Q.; Yan, T.; Zhou, Z.; Duan, H.; Li, X.; Wuriyanghan, H. Improvement of host-induced gene silencing efficiency via polycistronic-tRNA-amiR expression for multiple target genes and characterization of RNAi mechanism in Mythimna separata. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2021, 19, 1370–1385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, K.; Minkenberg, B.; Yang, Y. Boosting CRISPR/Cas9 multiplex editing capability with the endogenous tRNA-processing system. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, 3570–3575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, C.; Wang, X.; He, H.; Xu, C.; Cui, J. Beyond Loading: Functions of Plant ARGONAUTE Proteins. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 16054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva-Martins, G.; Bolaji, A.; Moffett, P. What does it take to be antiviral? An Argonaute-centered perspective on plant antiviral defense. J. Exp. Bot. 2020, 71, 6197–6210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Li, Y.; Wang, A. Research Advances in Potyviruses: From the Laboratory Bench to the Field. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 2021, 59, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Yuan, Y.R.; Pei, Y.; Lin, S.S.; Tuschl, T.; Patel, D.J.; Chua, N.H. Cucumber mosaic virus-encoded 2b suppressor inhibits Arabidopsis Argonaute1 cleavage activity to counter plant defense. Genes. Dev. 2006, 20, 3255–3268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, H.; Xia, L.; Lin, Z.; Li, H.; Ali, M.; Luo, S.; Hu, Q.; Zhang, Y. Cell-Specific Activation and Inhibition of Conserved PTI Genes by TMV in Susceptible Tobacco. Plant Cell Environ. 2025, 19, 70137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Mei, J.; Ren, G. Plant microRNAs: Biogenesis, Homeostasis, and Degradation. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Zhou, X.; Ren, Y. Host-virus molecular arms race: RNAi-mediated antiviral defense and viral suppressor of RNAi. Cell Insight 2025, 4, 100276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, Q.W.; Lin, S.S.; Reyes, J.L.; Chen, K.C.; Wu, H.W.; Yeh, S.D.; Chua, N.H. Expression of artificial microRNAs in transgenic Arabidopsis thaliana confers virus resistance. Nat. Biotechnol. 2006, 24, 1420–1428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwab, R.; Ossowski, S.; Riester, M.; Warthmann, N.; Weigel, D. Highly specific gene silencing by artificial microRNAs in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 2006, 18, 1121–1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabuma, T.; Sanan-Mishra, N. Artificial miRNAs and target-mimics as potential tools for crop improvement. Physiol. Mol. Biol. Plants 2025, 31, 67–91. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Al-Roshdi, M.R.; Ammara, U.; Khan, J.; Al-Sadi, A.M.; Shahid, M.S. Artificial microRNA-mediated resistance against Oman strain of tomato yellow leaf curl virus. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1164921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teotia, S.; Wang, X.; Zhou, N.; Wangm, M.; Liu, H.; Qin, J.; Han, D.; Li, C.; Li, C.E.; Pan, S.; et al. A high-efficiency gene silencing in plants using two-hit asymmetrical artificial MicroRNAs. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2023, 21, 1799–1811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, Z.; Wang, J.; Li, C. Research Progress on miRNAs and Artificial miRNAs in Insect and Disease Resistance and Breeding in Plants. Genes 2024, 15, 1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bally, J.; Fishilevich, E.; Doran, R.L.; Lee, K.; Campos, S.B.; German, M.A.; Narva, K.E.; Waterhouse, P.M. Plin-amiR, a pre-microRNA-based technology for controlling herbivorous insect pests. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2020, 18, 1925–1932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, N.; Zhang, D.; Chen, S.L.; Gong, B.Q.; Guo, Y.; Xu, L.; Zhang, X.N.; Li, J.F. Engineering Artificial MicroRNAs for Multiplex Gene Silencing and Simplified Transgenic Screen. Plant Physiol. 2018, 178, 989–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haney, C.H.; Long, S.R. Plant flotillins are required for infection by nitrogen-fixing bacteria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 478–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahim, M.; Millar, A.A.; Wood, C.C.; Larkin, P.J. Resistance to Wheat streak mosaic virus generated by expression of an artificial polycistronic microRNA in wheat. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2012, 10, 150–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brosseau, C.; Moffett, P. Functional and Genetic Analysis Identify a Role for Arabidopsis ARGONAUTE5 in Antiviral RNA Silencing. Plant Cell 2015, 27, 1742–1754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jelly, N.S.; Schellenbaum, P.; Walter, B.; Maillot, P. Transient expression of artificial microRNAs targeting Grapevine fanleaf virus and evidence for RNA silencing in grapevine somatic embryos. Transgenic Res. 2012, 21, 1319–1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pieczynski, M.; Marczewski, W.; Hennig, J.; Dolata, J.; Bielewicz, D.; Piontek, P.; Wyrzykowska, A.; Krusiewicz, D.; Strzelczyk-Zyta, D.; Konopka-Postupolska, D. Down-regulation of CBP80 gene expression as a strategy to engineer a drought-tolerant potato. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2013, 11, 459–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maunoury, N.; Vaucheret, H. AGO1 and AGO2 act redundantly in miR408-mediated Plantacyanin regulation. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e28729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diao, P.; Zhang, Q.; Sun, H.; Ma, W.; Cao, A.; Yu, R.; Wang, J.; Niu, Y.; Wuriyanghan, H. miR403a and SA Are Involved in NbAGO2 Mediated Antiviral Defenses Against TMV Infection in Nicotiana benthamiana. Genes 2019, 10, 526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín-Merchán, A.; Lavatelli, A.; Engler, C.; González-Miguel, V.M.; Moro, B.; Rosano, G.L.; Bologna, N.G. Arabidopsis AGO1 N-terminal extension acts as an essential hub for PRMT5 interaction and post-translational modifications. Nucleic Acids Res. 2024, 52, 8466–8482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baumberger, N.; Baulcombe, D.C. Arabidopsis ARGONAUTE1 is an RNA Slicer that selectively recruits microRNAs and short interfering RNAs. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2005, 102, 11928–11933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Odokonyero, D.; Mendoza, M.R.; Alvarado, V.Y.; Zhang, J.; Wang, X.; Scholthof, H.B. Transgenic down-regulation of ARGONAUTE2 expression in Nicotiana benthamiana interferes with several layers of antiviral defenses. Virology 2015, 486, 209–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carbonell, A.; Fahlgrenm, N.; Garcia-Ruizm, H.; Gilbert, K.B.; Montgomery, T.A.; Nguyen, T.; Cuperus, J.T.; Carrington, J.C. Functional analysis of three Arabidopsis ARGONAUTES using slicer-defective mutants. Plant Cell 2012, 24, 3613–3629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, P.; Zhang, J.; Liu, S.; Li, Y.; Qi, C.; Mo, Q.; Jiang, Y.; Hu, H.; Zhang, T.; Zhong, K. The plant signal peptide CLE7 induces plant defense response against viral infection in Nicotiana benthamiana. Dev. Cell 2025, 60, 934–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, L.; Ding, X.; Li, K.; Liao, W.; Zhong, Y.; Ren, R.; Liu, Z.; Adhimoolam, K.; Zhi, H. Characterization of Soybean mosaic virus resistance derived from inverted repeat-SMV-HC-Pro genes in multiple soybean cultivars. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2015, 128, 1489–1505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.J.; Kim, M.-J.; Pak, J.H.; Im, H.H.; Lee, D.H.; Kim, K.-H.; Lee, J.-H.; Kim, D.-H.; Choi, H.K.; Jung, H.W. RNAi-mediated Soybean mosaic virus (SMV) resistance of a Korean Soybean cultivar. Plant Biotechnol. Rep. 2016, 10, 257–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luan, H.; Liao, W.; Song, Y.; Niu, H.; Hu, T.; Zhi, H. Transgenic plant generated by RNAi-mediated knocking down of soybean Vma12 and soybean mosaic virus resistance evaluation. AMB Express 2020, 10, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bao, W.; Yan, T.; Deng, X.; Wuriyanghan, H. Synthesis of Full-Length cDNA Infectious Clones of Soybean Mosaic Virus and Functional Identification of a Key Amino Acid in the Silencing Suppressor Hc-Pro. Viruses 2020, 12, 886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bao, W.; Sun, D.; Qiu, Y.; Zhao, X.; Wuriyanghan, H. A Polycistronic tRNA-amiRNA System Reveals the Antiviral Roles of NbAGO1a/1b/2 Against Soybean mosaic virus Infection. Plants 2025, 14, 3724. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14243724

Bao W, Sun D, Qiu Y, Zhao X, Wuriyanghan H. A Polycistronic tRNA-amiRNA System Reveals the Antiviral Roles of NbAGO1a/1b/2 Against Soybean mosaic virus Infection. Plants. 2025; 14(24):3724. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14243724

Chicago/Turabian StyleBao, Wenhua, Danyang Sun, Yan Qiu, Xiaoke Zhao, and Hada Wuriyanghan. 2025. "A Polycistronic tRNA-amiRNA System Reveals the Antiviral Roles of NbAGO1a/1b/2 Against Soybean mosaic virus Infection" Plants 14, no. 24: 3724. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14243724

APA StyleBao, W., Sun, D., Qiu, Y., Zhao, X., & Wuriyanghan, H. (2025). A Polycistronic tRNA-amiRNA System Reveals the Antiviral Roles of NbAGO1a/1b/2 Against Soybean mosaic virus Infection. Plants, 14(24), 3724. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14243724