Differential Alteration of Gene Expression by Benzyl Adenine and meta-Topolin in In Vitro Apple Shoots

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

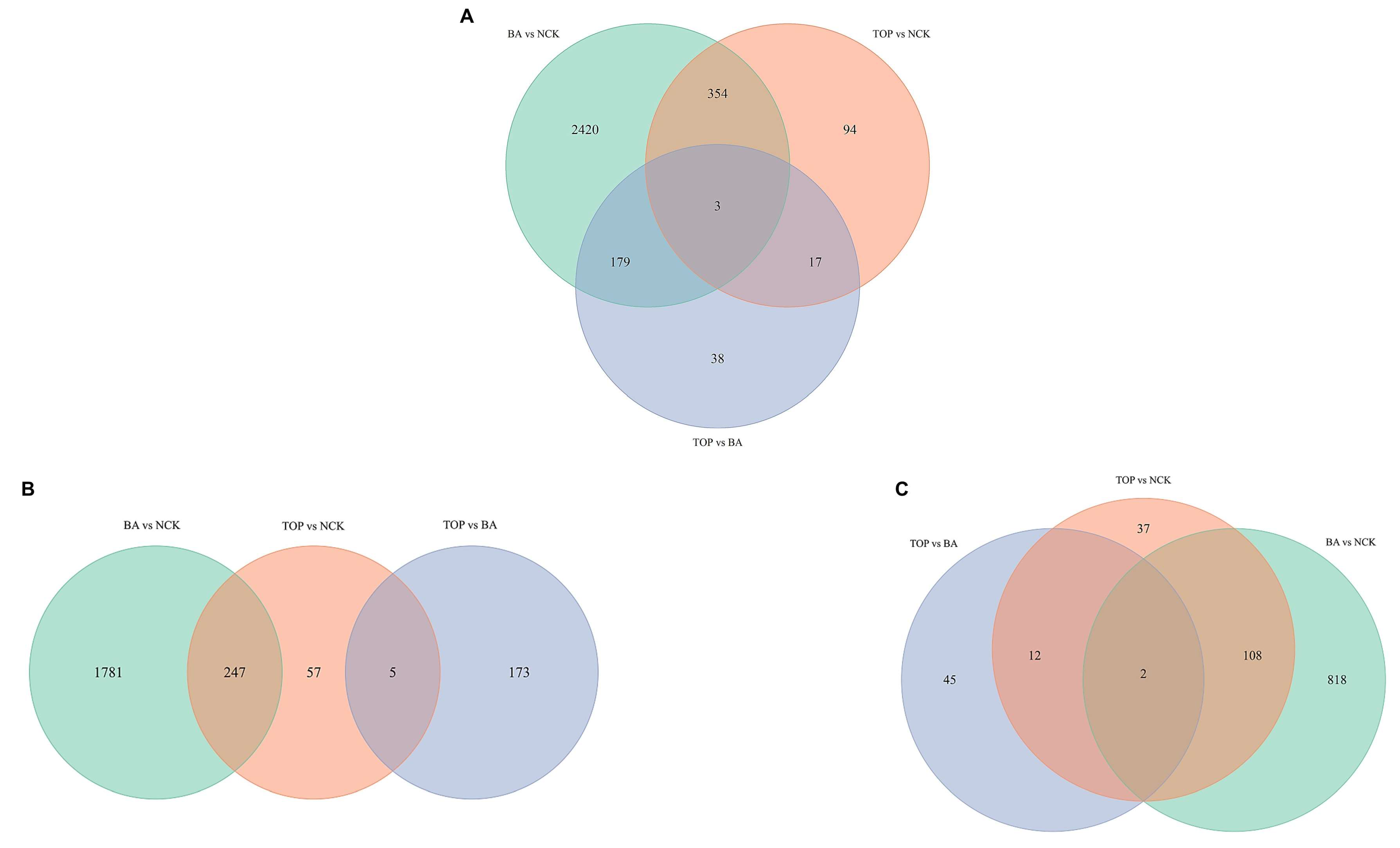

2.1. Evaluation of Global Changes in the RNA Expression Profile

2.2. Changes in Biological Processes, Cellular Components, and Molecular Function in Response to Various Cytokinin Supplies

2.3. Transcription Factor Behavior in Response to Different Cytokinin Supply

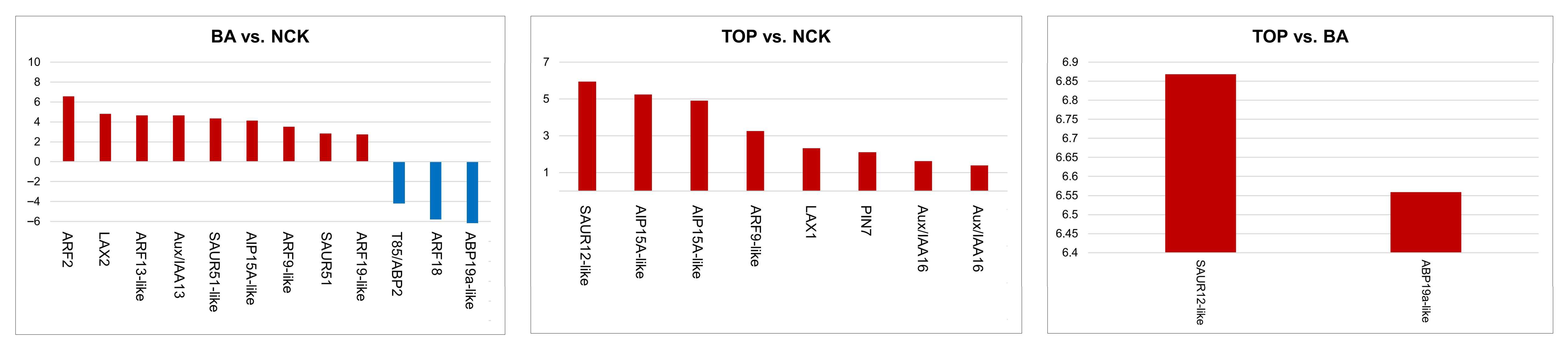

2.4. Up- and Down-Regulated DEGs Related to Auxin Signaling and Transport

2.5. KEGG Mapping of up- and Down-Regulated DEGs Related to Metabolic and Cellular Processes

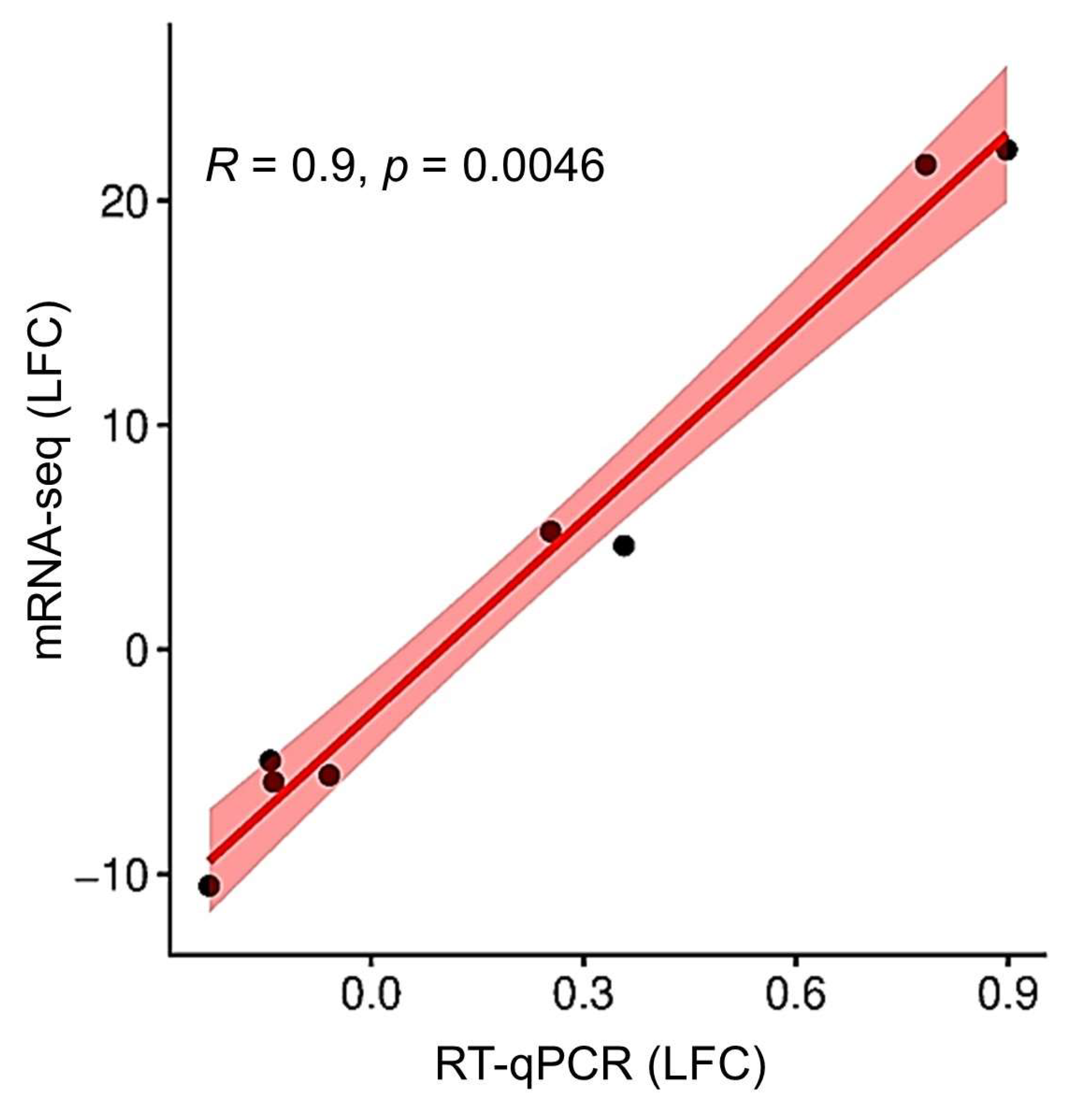

2.6. Validation with RT-qPCR

3. Discussion

3.1. Global Changes in the RNA Expression Profile

3.2. The Transcription Factors Affected Most in Response to Different Cytokinin Supply

3.3. DEGs Related to Auxin Signaling and Transport

3.4. DEGs Related to Metabolic and Cellular Processes Influencing Redox and Hormonal Balances

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Plant Material, In Vitro Growing Conditions, and Sample Collection

4.2. Isolation of mRNA and Sequencing

4.3. Bioinformatic Analysis and Functional Annotation of the Dataset

4.4. RT-qPCR Analysis for Validation

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Baldi, P.; Buti, M.; Gualandri, V.; Khomenko, I.; Farneti, B.; Biasioli, F.; Paffetti, D.; Malnoy, M. Transcriptomic and volatilomic profiles reveal Neofabraea vagabunda infection-induced changes in susceptible and resistant apples during storage. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2024, 212, 112889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerović, R.; Akšić, M.; Kitanović, M.; Meland, M. Abilities of the newly introduced apple cultivars (Malus × domestica Borkh.) ‘Eden’ and ‘Fryd’ to promote pollen tube growth and fruit set with different combinations of pollinations. Agronomy 2025, 15, 909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdalla, N.; Dobránszki, J. Meta-Topolin as an Effective Benzyladenine Derivative to Improve the Multiplication Rate and Quality of In Vitro Axillary Shoots of Húsvéti Rozmaring Apple Scion. Plants 2024, 13, 1568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farkas, D.; Ambrus, V.; Király, A.; Abdalla, N.; Dobránszki, J. Transcriptomic response of apple (Malus × domestica Borkh. cv. Húsvéti rozmaring) shoot explants to in vitro cultivation on media containing thidiazuron or 6-benzylaminopurine riboside. Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult. 2025, 161, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mierczak, K.; Garus-Pakowska, A. An overview of apple varieties and the importance of apple consumption in the prevention of non-communicable diseases—A narrative review. Nutrients 2024, 16, 3307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miranda, S.; Malnoy, M.; Aldrey, A.; Cernadas, M.J.; Sánchez, C.; Christie, B.; Vidal, N. Micropropagation of apple cultivars ‘Golden Delicious’ and ‘Royal Gala’ in bioreactors. Plants 2025, 14, 2740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, C.; Xie, Z.; Zhang, S.; Shao, D.; Ma, X.; Tong, L.; Tahir, M.M.; Lu, Z.; Namozov, I.; Zhang, D.; et al. Pangenome-wide characterization of the TCP gene family and its potential role in regulating adventitious shoot regeneration in apple. Agric. Commun. 2025, 3, 100101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hlophe, N.P.; Aremu, A.O.; Doležal, K.; Staden, J.V.; Finnie, J.F. Cytokinin-facilitated plant regeneration of three Brachystelma species with different conservation status. Plants 2020, 9, 1657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, J.P.R.; Mokhtari, A.M.; Wawrzyniak, M. Cytokinins combined with activated charcoal do not impair in vitro rooting in Quercus robur L.: Insights from morphophysiological and hormonal analyses. BMC Plant Biol. 2025, 25, 1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magyar-Tábori, K.; Dobránszki, J.; Teixeira da Silva, J.A.; Bulley, S.M.; Hudák, I. The role of cytokinins in shoot organogenesis in apple. Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult. 2010, 101, 251–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobránszki, J.; da Silva, J.A.T. Micropropagation of apple—A review. Biotechnol. Adv. 2010, 28, 462–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, N.; Strnad, M. Meta-Topolin: A Growth Regulator for Plant Biotechnology and Agriculture; Springer Nature: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, S.; Singh, A.; Mohan, M.; Das, S.N.; Rai, M.K. In vitro propagation, phytochemical analysis and assessment of antioxidative potential of micropropagated plants of Tecomaria capensis (Thunb.) Spach. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2025, 185, 16–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayaprakash, K.; Manokari, M.; Badhepuri, M.K.; Raj, M.C.; Shekhawat, M.S. Influence of meta-topolin on in vitro propagation and foliar micro-morpho-anatomical developments of Oxystelma esculentum (Lf) Sm. Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult. 2021, 147, 325–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ptak, A.; Szewczyk, A.; Simlat, M.; Błażejczak, A.; Warchoł, M. Meta-Topolin-induced mass shoot multiplication and biosynthesis of valuable secondary metabolites in Stevia rebaudiana Bertoni bioreactor culture. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 15520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasconcelos, J.N.C.; Brito, A.L.; Pinheiro, A.L.; e Costa Pinto, D.I.J.G.; da Silva Almeida, J.R.G.; Soares, T.L.; de Santana, J.R.F. Stimulation of 6-benzylaminopurine and meta-topolin-induced in vitro shoot organogenesis and production of flavonoids of Amburana cearensis (Allemão) A.C. Smith). Biocat. Agr. Biotech. 2019, 22, 101408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdouli, D.; Plačková, L.; Doležal, K.; Bettaieb, T.; Werbrouck, S.P.O. Topolin cytokinins enhanced shoot proliferation, reduced hyperhydricity and altered cytokinin metabolism in Pistacia vera L. seedling explants. Plant Sci. 2022, 322, 111360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bairu, M.W.; Stirk, W.A.; Doležal, K.; van Staden, J. The role of topolins in micropropagation and somaclonal variation of banana cultivars ‘Williams’ and ‘Grand Naine’ (Musa spp. AAA). Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult. 2008, 95, 373–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aremu, A.O.; Bairu, M.W.; Szüčová, L.; Doležal, K.; Finnie, J.F.; Van Staden, J. Genetic fidelity in tissue-cultured ‘Williams’ bananas—The effect of high concentration of topolins and benzyladenine. Sci. Hortic. 2013, 161, 324–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gentile, A.; Frattarelli, A.; Nota, P.; Condello, E.; Caboni, E. The aromatic cytokinin meta-topolin promotes in vitro propagation, shoot quality and micrografting in Corylus colurna L. Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult. 2017, 128, 693–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, A.; Anis, M. Meta-topolin improves in vitro morphogenesis, rhizogenesis and biochemical analysis in Pterocarpus marsupium Roxb.: A potential drug-yielding tree. J. Plant Growth Regul. 2019, 38, 1007–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khai, H.D.; Hiep, P.P.M.; Nguyen, P.L.H.; Hoa, H.C.K.; Thuy, N.T.T.; Mai, N.T.N.; Cuong, D.M.; Tung, H.T.; Luan, V.Q.; Vinh, B.V.T.; et al. Meta-topolin and silica nanoparticles induced vigorous carnation plantlet via regulation of antioxidant status and mineral absorption. Sci. Hortic. 2024, 327, 112877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, J.A.T.; Nezami-Alanagh, E.; Barreal, M.E.; Kher, M.M.; Wicaksono, A.; Gulyás, A.; Hidvégi, N.; Magyar-Tábori, K.; Mendler-Drienyovszki, N.; Márton, L.; et al. Shoot tip necrosis of in vitro plant cultures: A reappraisal of possible causes and solutions. Planta 2020, 252, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doležal, K.; Bryksová, M. Topolin metabolism and its implications for in vitro plant micropropagation. In Meta-Topolin: A Growth Regulator for Plant Biotechnology and Agriculture, 1st ed.; Ahmad, N., Strnad, M., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2021; pp. 49–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aremu, A.O.; Bairu, M.W.; Doležal, K.; Finnie, J.F.; Van Staden, J. Topolins: A panaceae to plant tissue culture challenges? Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult. 2012, 108, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subrahmanyeswari, T.; Gantait, S.; Kamble, S.N.; Singh, S.; Bhattacharyya, S. meta-Topolin-induced regeneration and ameliorated rebaudioside-A production in genetically uniform candy-leaf plantlets (Stevia rebaudiana Bert.). S. Afr. J. Bot. 2023, 159, 405–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gantait, S.; Mitra, M. Role of meta-topolin on in vitro shoot regeneration: An insight. In Meta-Topolin: A Growth Regulator for Plant Biotechnology and Agriculture; Ahmad, N., Strnad, M., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2021; pp. 143–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manokari, M.; Badhepuri, M.K.; Cokulraj, M.; Sandhya, D.; Dey, A.; Kumar, V.; Faisal, M.; Alatar, A.A.; Singh, R.K.; Shekhawat, M.S. Validation of meta-Topolin in organogenesis, improved morpho-physio-chemical responses, and clonal fidelity analysis in Dioscorea pentaphylla L.—An underutilized yam species. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2022, 145, 284–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bansal, S.; Sharma, M.K.; Joshi, P.; Malhotra, E.V.; Malik, S.K. Meta-topolin enhanced in vitro propagation and genetic integrity assessment in sweet potato (Ipomoea batatas (L.) Lam.). S. Afr. J. Bot. 2023, 157, 27–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chouhan, R.; Shekhawat, N.S.; Patel, A.K.; Ram, K.; Choudhary, A.; Ambawat, S.; Choudhary, S.K. Meta-topolin mediated enhanced micropropagation, foliar-micromorphological evaluation and genetic homogeneity validation in African pumpkin (Momordica balsamina L.). S. Afr. J. Bot. 2025, 180, 286–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poisson, A.S.; Berthelot, P.; Le Bras, C.; Grapin, A.; Vergne, E.; Chevreau, E. A droplet-vitrification protocol enabled cryopreservation of doubled haploid explants of Malus × domestica Borkh. ‘Golden Delicious’. Sci. Hortic. 2016, 209, 187–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gentile, A.; Jáquez Gutiérrez, M.; Martinez, J.; Frattarelli, A.; Nota, P.; Caboni, E. Effect of meta-Topolin on micropropagation and adventitious shoot regeneration in Prunus rootstocks. Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult. 2014, 118, 373–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitrova, N.; Nacheva, L.; Berova, M. Effect of meta-topolin on the shoot multiplication of pear rootstock OHF-333 (Pyrus communis L.). Acta Sci. Pol. Hortorum Cultus 2016, 15, 43–53. [Google Scholar]

- Mohapatra, N.; Deo, B. Substitution of BAP with meta-Topolin (m-T) in multiplication culture of Musa species. Plant Sci. Res. 2019, 41, 8–11. [Google Scholar]

- Elayaraja, D.; Subramanyam, K.; Vasudevan, V.; Sathish, S.; Kasthurirengan, S.; Ganapathi, A.; Manickavasagam, M. Meta-Topolin (mT) enhances the in vitro regeneration frequency of Sesamum indicum (L.). Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 2019, 21, 101320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halder, T.; Ghosh, B. Cytological, genetical and phytochemically stable meta-Topolin (mT)-induced mass propagation of underutilized Physalis minima L. for production of withaferin A. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 2021, 33, 102012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobránszki, J.; Magyar-Tábori, J.; Jámbor-Benczúr, E.; Lazányi, J.; Bubán, T.; Szalai, J. Influence of aromatic cytokinins on shoot multiplication and their after-effects on rooting of apple cv. Húsvéti rozmaring. Int. J. Hortic. Sci. 2000, 6, 84–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Mahrouk, M.E.; Dewir, Y.H.; Omar, A.M.K. In vitro propagation of adult strawberry tree (Arbutus unedo L.) through adventitious shoots and somatic embryogenesis. Propag. Ornam. Plants 2010, 10, 93–98. [Google Scholar]

- Seliem, M.K.; Abdalla, N.; El-Mahrouk, M.E. Cytokinin potentials on in vitro shoot proliferation and subsequent rooting of Agave sisalana Perr. Syn. Horticulturae 2025, 11, 929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luna, M.; del Valle, J.R.E.; Velasco, V.A.V.; Aparicio, Y.V.; Rodríguez, J.C.C. Benzyladenine concentration, type and dose of carbohydrates in the culture medium for shoot proliferation of Agave americana. Rev. Fac. Cienc. Agrar. Univ. Nac. Cuyo 2014, 46, 97–107. [Google Scholar]

- Dewir, Y.H.; Murthy, H.N.; Ammar, M.H.; Alghamdi, S.S.; Al-Suhaibani, N.A.; Alsadon, A.A.; Paek, K.Y. In vitro rooting of leguminous plants: Difficulties, alternatives, and strategies for improvement. Hortic. Environ. Biotechnol. 2016, 57, 311–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahir, M.M.; Fan, L.; Liu, Z.; Raza, H.; Aziz, U.; Shehzaib, A.; Li, S.; He, Y.; Lu, Y.; Ren, X.; et al. Physiological and molecular mechanisms of cytokinin involvement in nitrate-mediated adventitious root formation in apples. J. Integr. Agric. 2024, 23, 4046–4057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aremu, A.O.; Bairu, M.W.; Szüčová, L.; Doležal, K.; Finnie, J.F.; Van Staden, J. Assessment of the role of meta-topolins on in vitro produced phenolics and acclimatization competence of micropropagated ‘Williams’ banana. Acta Physiol. Plant. 2012, 34, 2265–2273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aremu, A.O.; Bairu, M.W.; Szüčová, L.; Finnie, J.F.; Van Staden, J. The role of meta-topolins on the photosynthetic pigment profiles and foliar structures of micropropagated ‘Williams’ bananas. J. Plant Physiol. 2012, 169, 1530–1541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zaytseva, Y.; Tatyana, N.; Ambros, E. Meta-topolin: Advantages and disadvantages for in vitro propagation. In Meta-Topolin: A Growth Regulator for Plant Biotechnology and Agriculture; Ahmad, N., Strnad, M., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2021; pp. 119–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobránszki, J.; Mendler-Drienyovszki, N. Cytokinin-induced changes in the chlorophyll content and fluorescence of in vitro apple leaves. J. Plant Physiol. 2014, 171, 1472–1478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manokari, M.; Jayaprakash, K.; Cokulraj, M.; Dey, A.; Faisal, M.; Alatar, A.A.; Joshee, N.; Shekhawat, M.S. In vitro micro-morphometric growth modulations induced by N6 cytokinins (Meta-Topolin and 6-benzylaminopurine) in Ceropegia juncea Roxb.—A rare medicinal climber. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2023, 157, 656–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, T.; Sakai, H.; Meyerowitz, E.M. Whorl-specific expression of the SUPERMAN gene of Arabidopsis is mediated by cis elements in the transcribed region. Curr Biol. 2003, 13, 1524–1530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Ding, H.; Deng, Y.; Zhang, J. Knockdown of quinolinate phosphoribosyltransferase results in decreased salicylic acid-mediated pathogen resistance in Arabidopsis thaliana. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 8484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamada, M.; Han, X.; Benfey, P.N. RGF1 controls root meristem size through ROS signalling. Nature 2020, 577, 85–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mockaitis, K.; Estelle, M. Auxin receptors and plant development: A new signaling paradigm. Annu. Rev. Cell. Dev. Biol. 2008, 24, 55–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Li, D.; Zhang, L.L.; Borthakur, D.; Li, Q.S.; Ye, J.H.; Zheng, X.Q.; Lu, J.L. MicroRNAs and their targeted genes associated with phase changes of stem explants during tissue culture of tea plant. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 20239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niedz, R.P.; Evens, T.J. The effects of benzyladenine and meta-topolin on in vitro shoot regeneration of a citrus citrandarin rootstock. Res. J. Agric. Biol. Sci. 2010, 6, 45–53. [Google Scholar]

- Wojtania, A. Effect of meta-topolin on in vitro propagation of Pelargonium x hortorum and Pelargonium x hederaefolium cultivars. Acta Soc. Bot. Pol. 2010, 79, 101–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magyar-Tábori, K.; Dobránszki, J.; Hudák, I. Effect of cytokinin content of the regeneration media on in vitro rooting ability of adventitious apple shoots. Sci. Hortic. 2011, 129, 910–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moyo, M.; Finnie, J.F.; Van Staden, J. Recalcitrant effects associated with the development of basal callus-like tissue on caulogenesis and rhizogenesis in Sclerocarya birrea. Plant Growth Regul. 2011, 63, 187–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobránszki, J.; Mendler-Drienyovszki, N. Cytokinins and photosynthetic apparatus of leaves on in vitro axillary shoots of apple cv. Freedom. Hung. Agric. Res. 2015, 1, 20–24. [Google Scholar]

- Magyar-Tábori, K.; Dobránszki, J.; Jámbor-Benczúr, E.; Lazányi, J. Role of cytokinins in shoot proliferation of apple in vitro. In Analele Universitii din Oradea Tom VII. Partea I. Fascicula Agricultur Si Horticulture; Romanian University: Bucharest, Romania, 2001; pp. 17–24. [Google Scholar]

- Magyar-Tábori, K.; Dobránszki, J.; Jámbor-Benczúr, E. High in vitro shoot proliferation in the apple cultivar Jonagold induced by benzyladenine analogues. Acta Agron. Hung. 2002, 50, 191–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javed, T.; Gao, S.J. WRKY transcription factors in plant defense. Trends Genet. 2023, 39, 787–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, Y.; Zong, X.; Ren, P.; Qian, Y.; Fu, A. Basic Helix-Loop-Helix (bHLH) Transcription Factors Regulate a Wide Range of Functions in Arabidopsis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 7152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nesi, N.; Debeaujon, I.; Jond, C.; Pelletier, G.; Caboche, M.; Lepiniec, L. The TT8 gene encodes a basic helix-loop-helix domain protein required for expression of DFR and BAN genes in Arabidopsis siliques. Plant Cell 2000, 12, 1863–1878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillon, A.; Shen, H.; Huq, E. Phytochrome interacting factors: Central players in phytochrome-mediated light signaling networks. Trends Plant Sci. 2007, 12, 514–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedrichsen, D.M.; Nemhauser, J.; Muramitsu, T.; Maloof, J.N.; Alonso, J.; Ecker, J.R.; Furuya, M.; Chory, J. Three redundant brassinosteroid early response genes encode putative bHLH transcription factors required for normal growth. Genetics 2002, 162, 1445–1456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Zhou, H.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Feng, X.; Lin, H. Diverse roles of MYB transcription factors in plants. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2025, 67, 539–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gramzow, L.; Theissen, G. A hitchhiker’s guide to the MADS world of plants. Genome Biol. 2010, 11, 214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arora, R.; Agarwal, P.; Ray, S.; Singh, A.K.; Singh, V.P.; Tyagi, A.K. MADS-box gene family in rice: Genome-wide identification, organization and expression profiling during reproductive development and stress. BMC Genom. 2007, 8, 242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jia, J.; Zhao, P.; Cheng, L.; Yuan, G.; Yang, W.; Liu, S.; Chen, S.; Qi, D.; Liu, G.; Li, X. MADS-box family genes in sheepgrass and their involvement in abiotic stress responses. BMC Plant Biol. 2018, 18, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, M.; Wang, Y.; Pan, R.; Li, W. Genome-wide identification and characterization of MADS-box family genes related to floral organ development and stress resistance in Hevea brasiliensis Müll. Arg. Forests 2018, 9, 304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z.; Hu, L.; Jiang, W. Understanding AP2/ERF transcription factor responses and tolerance to various abiotic stresses in plants: A comprehensive review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, B.; Gunnerås, S.A.; Petersson, S.V.; Tarkowski, P.; Graham, N.; May, S.; Dolezal, K.; Sandberg, G.; Ljung, K. Cytokinin regulation of auxin synthesis in Arabidopsis involves a homeostatic feedback loop regulated via auxin and cytokinin signal transduction. Plant Cell 2010, 22, 2956–2969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laplaze, L.; Benkova, E.; Casimiro, I.; Maes, L.; Vanneste, S.; Swarup, R.; Weijers, D.; Calvo, V.; Parizot, B.; Herrera-Rodriguez, M.B.; et al. Cytokinins act directly on lateral root founder cells to inhibit root initiation. Plant Cell 2007, 19, 3889–3900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Růžička, K.; Šimášková, M.; Duclercq, J.; Petrášek, J.; Zažímalová, E.; Simon, S.; Friml, J.; Van Montagu, M.C.E.; Benková, E. Cytokinin regulates root meristem activity via modulation of the polar auxin transport. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 4284–4289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbez, E.; Kubeš, M.; Rolčík, J.; Béziat, C.; Pěnčík, A.; Wang, B.; Rosquete, M.R.; Zhu, J.; Dobrev, P.I.; Lee, Y.; et al. A novel putative auxin carrier family regulates intracellular auxin homeostasis in plants. Nature 2012, 485, 119–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohanta, T.K.; Mohanta, N.; Bae, H. Identification and expression analysis of PIN-like (PILS) gene family of rice treated with auxin and cytokinin. Genes 2015, 6, 622–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Křeček, P.; Skůpa, P.; Libus, J.; Naramoto, S.; Tejos, R.; Friml, J.; Zažímalová, E. The PIN-FORMED (PIN) protein family of auxin transporters. Genome Biol. 2009, 10, 249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Péret, B.; Swarup, K.; Ferguson, A.; Seth, M.; Yang, Y.; Dhondt, S.; James, N.; Casimiro, I.; Perry, P.; Syed, A.; et al. AUX/LAX genes encode a family of auxin influx transporters that perform distinct functions during Arabidopsis development. Plant Cell 2012, 24, 2874–2885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bainbridge, K.; Guyomarc’h, S.; Bayer, E.; Swarup, R.; Bennett, M.; Mandel, T.; Kuhlemeier, C. Auxin influx carriers stabilize phyllotactic patterning. Genes Dev. 2008, 22, 810–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guilfoyle, T.J.; Hagen, G. Auxin response factors. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2007, 10, 453–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guilfoyle, T.J.; Ulmasov, T.; Hagen, G. The ARF family of transcription factors and their role in plant hormone-responsive transcription. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 1998, 54, 619–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chandler, J.W. Auxin response factors. Plant Cell Environ. 2016, 39, 1014–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okushima, Y.; Mitina, I.; Quach, H.L.; Theologis, A. AUXIN RESPONSE FACTOR 2 (ARF2): A pleiotropic developmental regulator. Plant J. 2005, 43, 29–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Jong, M.; Wolters-Arts, M.; Schimmel, B.C.; Stultiens, C.L.; de Groot, P.F.; Powers, S.J.; Tikunov, Y.M.; Bovy, A.G.; Mariani, C.; Vriezen, W.H.; et al. Solanum lycopersicum AUXIN RESPONSE FACTOR 9 regulates cell division activity during early tomato fruit development. J. Exp. Bot. 2015, 66, 3405–3416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.C.; Wang, N.; Xu, H.F.; Jiang, S.H.; Fang, H.C.; Su, M.Y.; Zhang, Z.Y.; Zhang, T.L.; Chen, X.S. Auxin regulates anthocyanin biosynthesis through the Aux/IAA-ARF signaling pathway in apple. Hortic Res. 2018, 5, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Y.; Kong, X.; Hu, K.; Cao, M.; Liu, J.; Ma, C.; Guo, S.; Yuan, X.; Zhao, S.; Robert, H.S.; et al. PIFs coordinate shade avoidance by inhibiting auxin repressor ARF18 and metabolic regulator QQS. New Phytol. 2020, 228, 609–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, X.; Zhang, X.; Luo, J.; Wang, Y.; Feng, B.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, B.; Li, Y.; Zhang, H.; Yuan, W.; et al. The IAA7-ARF7-ARF19 auxin signaling module plays diverse roles in Arabidopsis growth and development. Planta 2025, 262, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guilfoyle, T.J. The PB1 Domain in Auxin Response Factor and Aux/IAA Proteins: A Versatile Protein Interaction Module in the Auxin Response. Plant Cell 2015, 27, 33–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, H.; Li, H.; Yu, J.; Zhao, H.; Zhang, K.; Ge, W. Regulatory Mechanisms of ArAux/IAA13 and ArAux/IAA16 in the Rooting Process of Acer rubrum. Genes 2023, 14, 1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liscum, E.; Reed, J.W. Genetics of Aux /IAA and ARF action in plant growth and development. Plant Mol. Biol. 2002, 49, 387–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quint, M.; Gray, W.M. Auxin signaling. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2006, 9, 448–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esmon, C.; Tinsley, A.; Ljung, K.; Sandberg, G.; Hearne, L.; Liscum, E. A gradient of auxin and auxin-dependent transcription precedes tropic growth responses. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2006, 103, 236–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spartz, A.; Lee, S.H.; Wenger, J.P.; Gonzalez, N.; Itoh, H.; Inzé, D.; Peer, W.A.; Murphy, A.S.; Overvoorde, P.J.; Gray, W.M. The SAUR19 subfamily of small auxin-up RNA genes promote cell expansion. Plant J. 2012, 70, 978–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Mourik, H.; van Dijk, A.D.J.; Stortenbeker, N.; Angenent, G.C.; Bemer, M. Divergent regulation of Arabidopsis SAUR genes: A focus on the SAUR10-clade. BMC Plant Biol. 2017, 17, 245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, T.; Wen, M.; Nagawa, S.; Fu, Y.; Chen, J.G.; Wu, M.J.; Perrot-Rechenmann, C.; Friml, J.; Jones, A.M.; Yang, Z. Cell surface- and rho GTPase-based auxin signaling controls cellular interdigitation in Arabidopsis. Cell 2010, 143, 99–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takei, K.; Yamaya, T.; Sakakibara, H. Arabidopsis CYP735A1 and CYP735A2 encode cytokinin hydroxylases that catalyze the biosynthesis of trans-Zeatin. J. Biol. Chem. 2004, 279, 41866–41872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.S.; Hasan, M.S.; Hasan, M.N.; Prodhan, S.H.; Islam, T.; Ghosh, A. Genome-wide identification, evolution, and transcript profiling of Aldehyde dehydrogenase superfamily in potato during development stages and stress conditions. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 18284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tola, A.J.; Jaballi, A.; Germain, H.; Missihoun, T.D. Recent development on plant aldehyde dehydrogenase enzymes and their functions in plant development and stress signaling. Genes 2021, 12, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiszniewski, A.A.G.; Bussell, J.D.; Long, R.L.; Smith, S.M. Knockout of the two evolutionarily conserved peroxisomal 3-ketoacyl-CoA thiolases in Arabidopsis recapitulates the abnormal inflorescence meristem 1 phenotype. J. Exp. Bot. 2014, 65, 6723–6733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pye, V.E.; Christensen, C.E.; Dyer, J.H.; Arent, S.; Henriksen, A. Peroxisomal plant 3-ketoacyl-CoA thiolase structure and activity are regulated by a sensitive redox switch. J. Biol. Chem. 2010, 285, 24078–24088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, Z.; Jia, Y.; Huang, X.; Chen, Z.; Xiang, T.; Han, N.; Bian, H.; Li, C. Transcriptional and protein structural characterization of homogentisate phytyltransferase genes in barley, wheat, and oat. BMC Plant Biol. 2023, 23, 528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kue Foka, I.C.; Ketehouli, T.; Zhou, Y.; Li, X.-W.; Wang, F.-W.; Li, H. The emerging roles of diacylglycerol kinase (DGK) in plant stress tolerance, growth, and development. Agronomy 2020, 10, 1375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tivendale, N.D.; Belt, K.; Berkowitz, O.; Whelan, J.; Millar, A.H.; Huang, S. Knockdown of succinate dehydrogenase assembly factor 2 induces reactive oxygen species-mediated auxin hypersensitivity causing pH-dependent root elongation. Plant Cell Physiol. 2021, 62, 1185–1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Privalle, L.S. Phosphomannose isomerase, a novel plant selection system: Potential allergenicity assessment. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2002, 964, 129–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mottiar, Y.; Tschaplinski, T.J.; Ralph, J.; Mansfield, S.D. Suppression of chorismate mutase 1 in hybrid poplar to investigate potential redundancy in the supply of lignin precursors. Plant Direct 2025, 9, e70053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashikari, M.; Sasaki, A.; Ueguchi-Tanaka, M.; Itoh, H.; Nishimura, A.; Datta, S.; Ishiyama, K.; Saito, T.; Kobayashi, M.; Khush, G.S.; et al. Loss-of-function of a rice gibberellin biosynthetic gene, GA20 oxidase (GA20ox-2), led to the rice ‘green revolution’. Breed. Sci. 2002, 52, 143–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasanthakumar, T.; Rubinstein, J.L. Structure and roles of V-type ATPases. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2020, 45, 295–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foyer, C.H.; Noctor, G. Redox homeostasis and antioxidant signaling: A metabolic interface between stress perception and physiological responses. Plant Cell 2005, 17, 1866–1875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stoian, I.A.M.; Vlad, A.; Gilca, M.; Dragos, D. Modulation of glutathione-s-transferase by phytochemicals: To activate or inhibit—That is the question. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 7202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Couto, N.; Wood, J.; Barber, J. The role of glutathione reductase and related enzymes on cellular redox homoeostasis network. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2016, 95, 27–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schöttler, M.A.; Thiele, W.; Belkius, K.; Bergner, S.V.; Flügel, C.; Wittenberg, G.; Agrawal, S.; Stegemann, S.; Ruf, S.; Bock, R. The plastid-encoded PsaI subunit stabilizes photosystem I during leaf senescence in tobacco. J. Exp. Bot. 2017, 68, 1137–1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Hong, X.; Hu, K.; Wang, Y.; Wang, X.; Du, S.; Li, Y.; Hu, D.; Cheng, K.; An, B.; et al. Impaired magnesium protoporphyrin IX methyltransferase (ChlM) impedes chlorophyll synthesis and plant growth in rice. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 1694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laskowski, M.J.; Dreher, K.A.; Gehring, M.A.; Abel, S.; Gensler, A.L.; Sussex, I.M. FQR1, a novel primary auxin-response gene, encodes a flavin mononucleotide-binding quinone reductase. Plant Physiol. 2002, 128, 578–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiller, D.; Contreras, C.; Vogt, J.; Dunemann, F.; Defilippi, B.G.; Beaudry, R.; Schwab, W. A dual positional specific lipoxygenase functions in the generation of flavor compounds during climacteric ripening of apple. Hortic. Res. 2015, 2, 15003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, C.; Karim, S.; Zhang, H.; Aronsson, H. Arabidopsis RabF1 (ARA6) is involved in salt stress and dark-induced senescence (DIS). Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murashige, T.; Skoog, F. A revised medium for rapid growth and bio assays with tobacco tissue cultures. Physiol. Plant 1962, 15, 473–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Zhou, Y.; Chen, Y.; Gu, J. fastp: An ultra-fast all-in-one FASTQ preprocessor. Bioinformatics 2018, 34, i884–i890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrews, S. FastQC: A Quality Control Tool for High Throughput Sequence Data. Available online: http://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc/ (accessed on 28 August 2025).

- Kim, D.; Paggi, J.M.; Park, C.; Bennett, C.; Salzberg, S.L. Graph-based genome alignment and genotyping with HISAT2 and HISAT-genotype. Nat. Biotechnol. 2019, 37, 907–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liao, Y.; Smyth, G.K.; Shi, W. featureCounts: An efficient general purpose program for assigning sequence reads to genomic features. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 923–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Love, M.I.; Huber, W.; Anders, S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 2014, 15, 550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, G.; Wang, L.G.; Han, Y.; He, Q.Y. clusterProfiler: An R package for comparing biological themes among gene clusters. OMICS 2012, 16, 284–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wickham, H. ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis (Use R!), 2nd ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- The R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2025; Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 30 August 2025).

- Silver, N.; Best, S.; Jiang, J.; Thein, S.L. Selection of housekeeping genes for gene expression studies in human reticulocytes using real-time PCR. BMC Mol. Biol. 2006, 7, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandesompele, J.; De Preter, K.; Pattyn, F.; Poppe, B.; Van Roy, N.; De Paepe, A.; Speleman, F. Accurate normalization of real-time quantitative RT-PCR data by geometric averaging of multiple internal control genes. Genome Biol. 2002, 3, research0034.1–0034.11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, C.L.; Jensen, J.L.; Ørntoft, T.F. Normalization of real-time quantitative reverse transcription-PCR data: A model-based variance estimation approach to identify genes suited for normalization, applied to bladder and colon cancer data sets. Cancer Res. 2004, 64, 5245–5250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfaffl, M.W.; Tichopad, A.; Prgomet, C.; Neuvians, T.P. Determination of stable housekeeping genes, differentially regulated target genes and sample integrity: Bestkeeper-excel-based tool using pair-wise correlations. Biotechnol. Lett. 2004, 26, 509–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, F.; Xiao, P.; Chen, D.; Xu, L.; Zhang, B. miRDeepFinder: A miRNA analysis tool for deep sequencing of plant small RNAs. Plant Mol. Biol. 2012, 80, 75–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farkas, D.; Király, A.; Ambrus, V.; Tóth, B.; Dobránszki, J. Short-term transcriptional memory and association-forming ability of tomato plants in response to ultrasound and drought stress stimuli. Plant Signal. Behav. 2025, 20, 2556982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livak, K.J.; Schmittgen, T.D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCT method. Methods 2001, 25, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Treatment Comparisons | BA vs. NCK | TOP vs. NCK | TOP vs. BA |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total number of DEGs | 2956 | 468 | 237 |

| Up-regulated DEGs (↑) | 2028 | 309 | 178 |

| Down-regulated DEGs (↓) | 928 | 159 | 59 |

| Pathways | BA vs. CK-Free | TOP vs. CK-Free | TOP vs. BA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Metabolism | ||||

| Global | ||||

| Metabolic pathways | ↓12↑3 | ↓4↑1 | ||

| Biosynthesis of secondary metabolites | ↓8↑2 | |||

| Lipid metabolism | ||||

| Linoleic acid metabolism | ↑1 | |||

| Amino acid metabolism | ||||

| Valine, leucine and isoleucine degradation | ↓2 | |||

| Metabolism of terpenoids and polyketides | ||||

| Diterpenoid biosynthesis; including Gibberellin biosynthesis | ↑1 | |||

| Cellular Processes | ||||

| Transport and catabolism | ||||

| Efferocytosis | ↑1 | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Király, A.; Ambrus, V.; Farkas, D.; Abdalla, N.; Dobránszki, J. Differential Alteration of Gene Expression by Benzyl Adenine and meta-Topolin in In Vitro Apple Shoots. Plants 2025, 14, 3691. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14233691

Király A, Ambrus V, Farkas D, Abdalla N, Dobránszki J. Differential Alteration of Gene Expression by Benzyl Adenine and meta-Topolin in In Vitro Apple Shoots. Plants. 2025; 14(23):3691. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14233691

Chicago/Turabian StyleKirály, Anita, Viktor Ambrus, Dóra Farkas, Neama Abdalla, and Judit Dobránszki. 2025. "Differential Alteration of Gene Expression by Benzyl Adenine and meta-Topolin in In Vitro Apple Shoots" Plants 14, no. 23: 3691. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14233691

APA StyleKirály, A., Ambrus, V., Farkas, D., Abdalla, N., & Dobránszki, J. (2025). Differential Alteration of Gene Expression by Benzyl Adenine and meta-Topolin in In Vitro Apple Shoots. Plants, 14(23), 3691. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14233691