Impact of Climate Change on the Invasion of Mikania micrantha Kunth in China: Predicting Future Distribution Using MaxEnt Modeling

Abstract

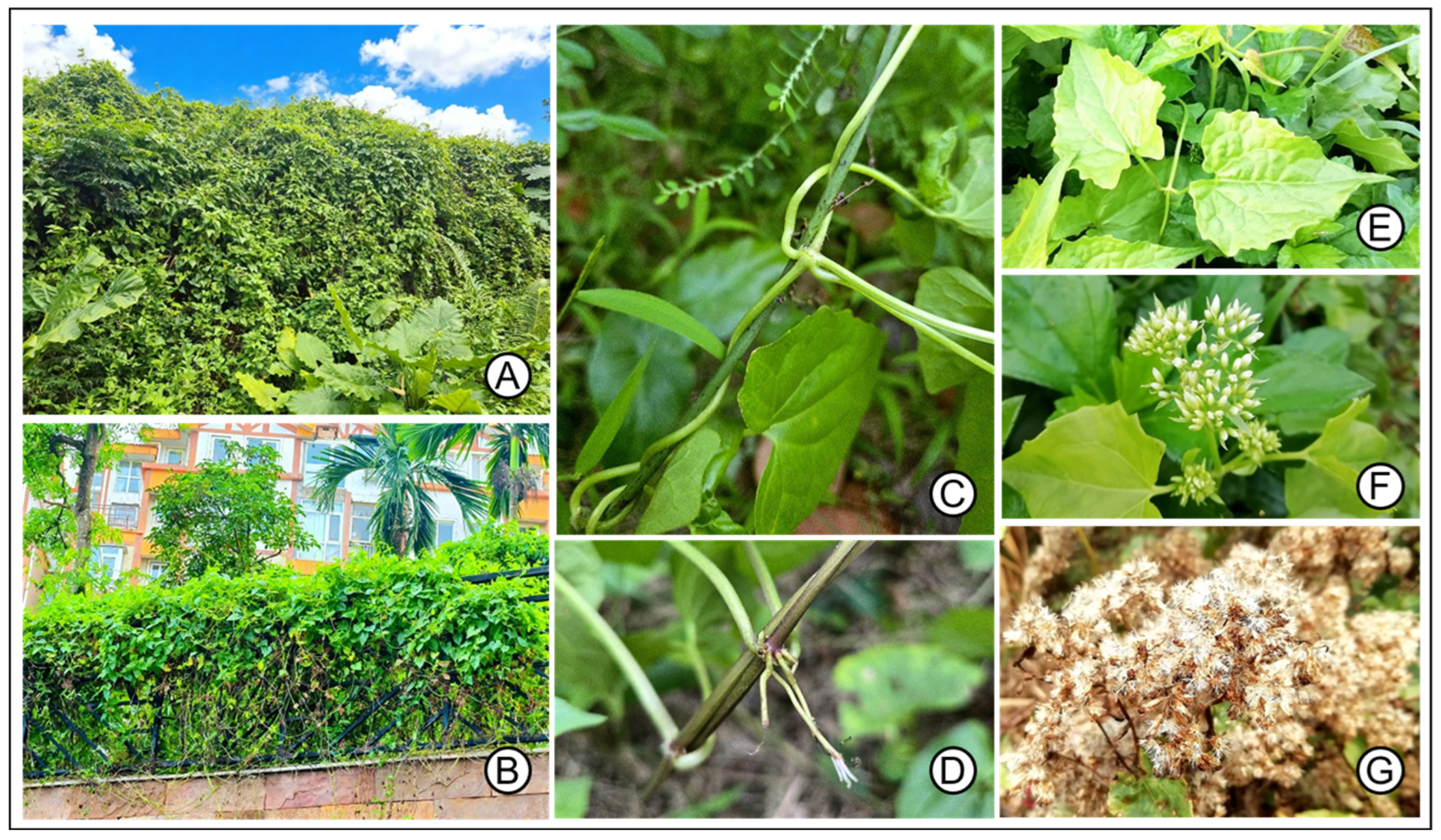

1. Introduction

2. Results

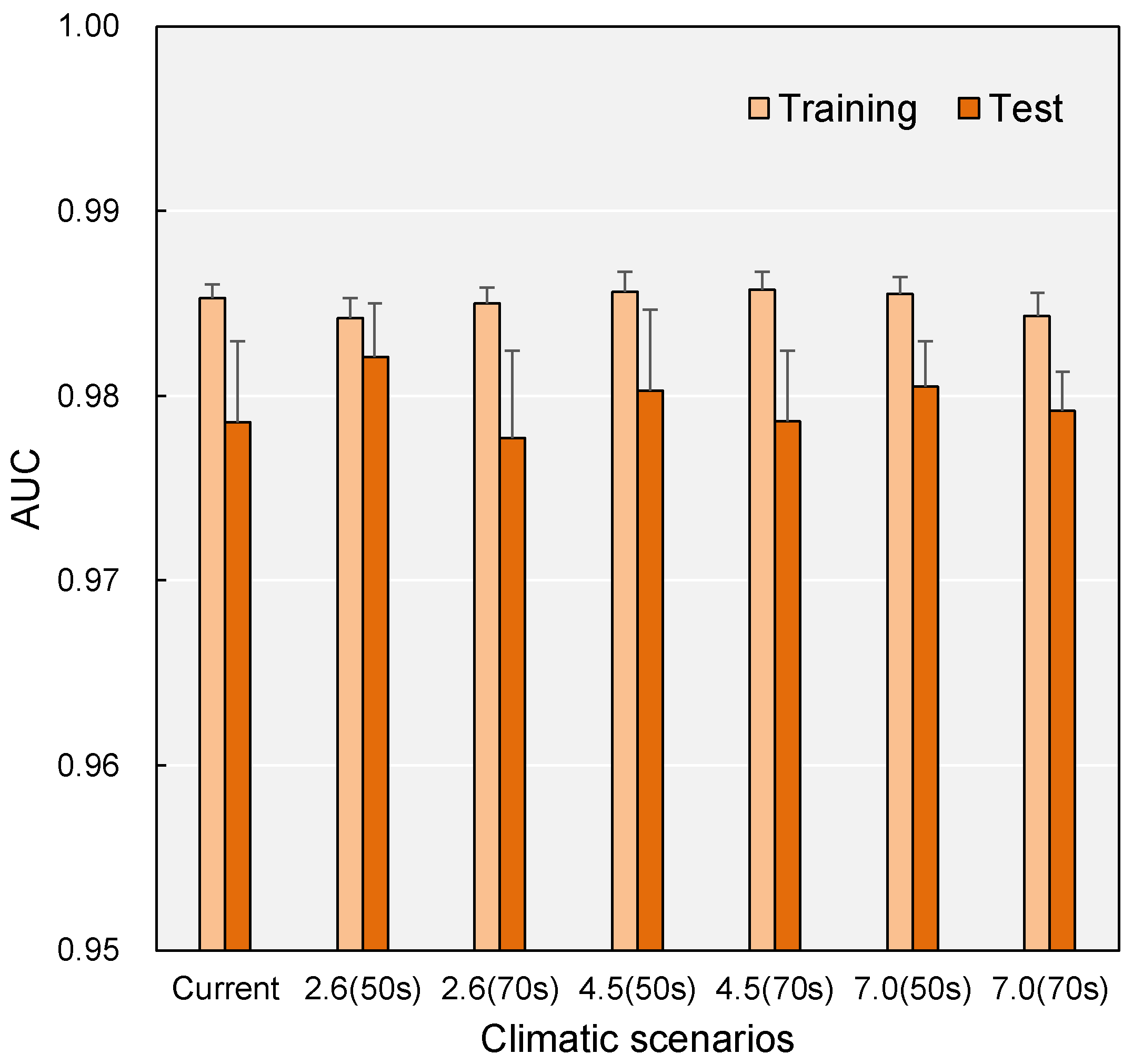

2.1. Model Accuracy

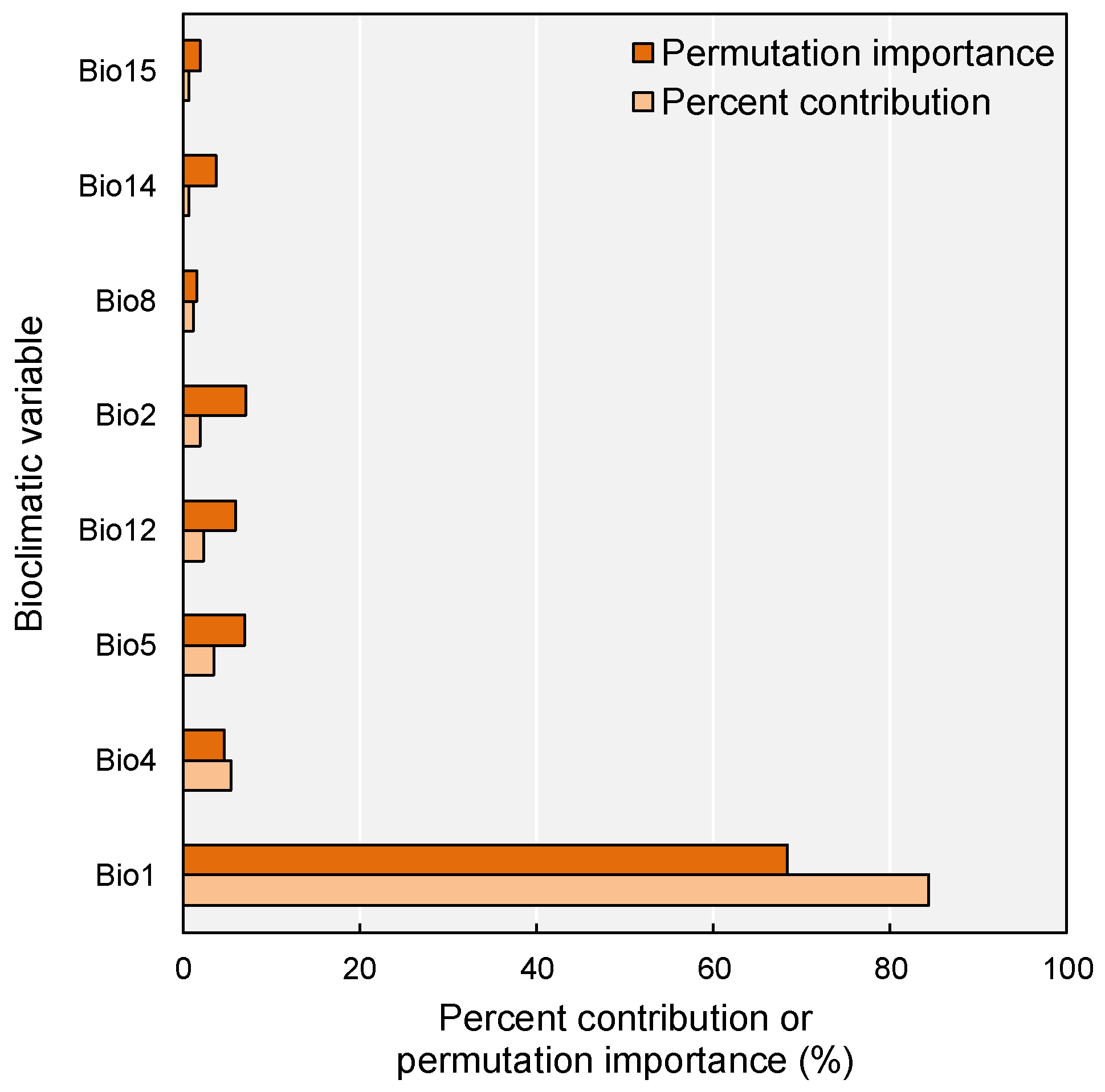

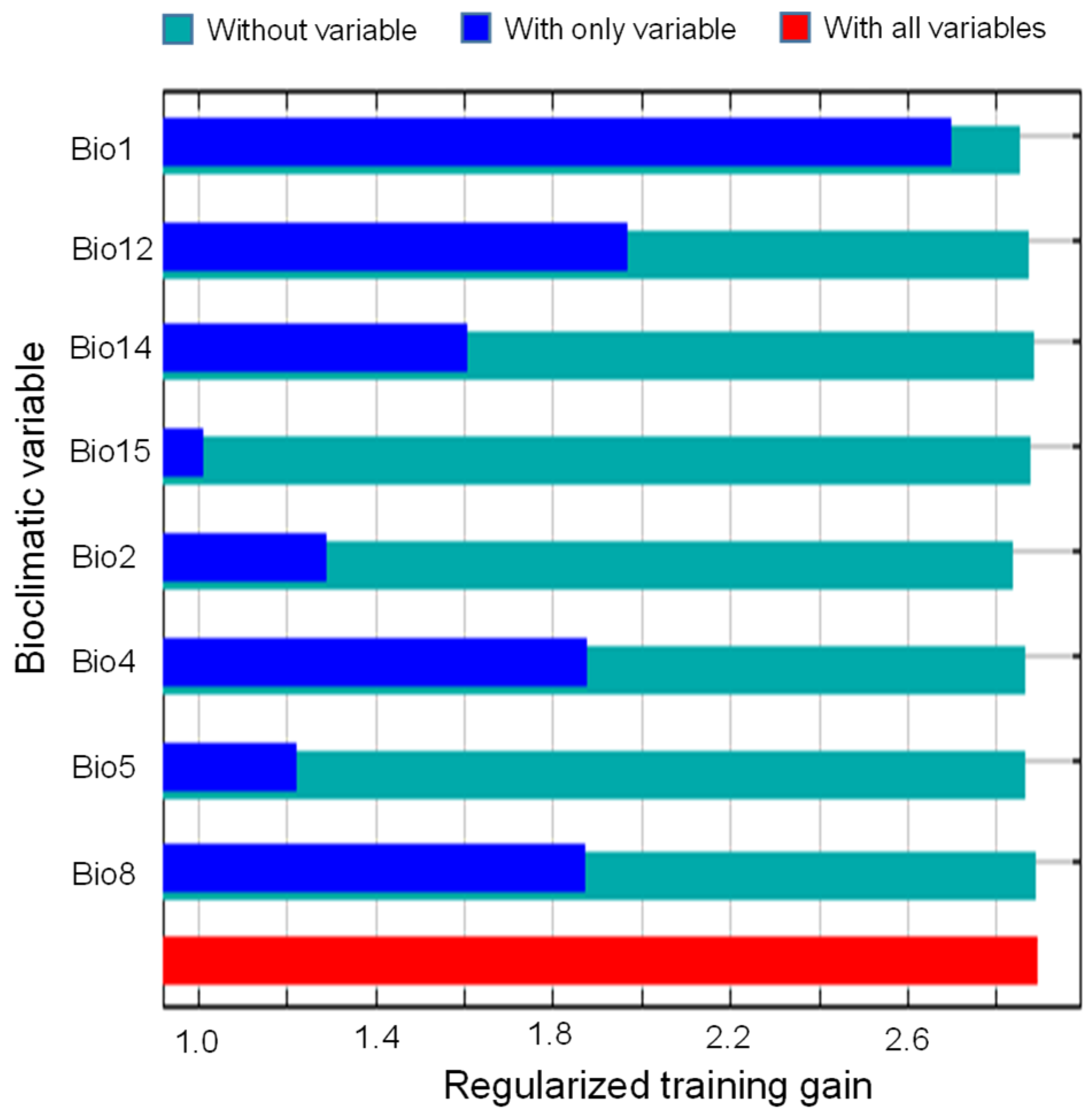

2.2. Key Bioclimatic Drivers of the Current Distribution Pattern

2.3. Current Potential Distribution and Habitat Suitability

2.4. Future Habitat Suitability Pattern

3. Discussion

3.1. Model Performance and Predictive Reliability

3.2. Climatic Determinants of M. micrantha Distribution

3.3. Current Distribution Patterns and Invasion Dynamics

3.4. Future Distribution Under Climate Change Scenarios

3.5. Implications for Invasion Management

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Species Occurrence Data

4.2. Bioclimatic Variables

4.3. Model Optimization

4.4. MaxEnt Modeling and Evaluation

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Bioclimatic Variable | Unit | Bioclimatic Variable | Unit |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bio1: Annual mean temperature | °C | Bio11: Mean temperature of the coldest quarter | °C |

| Bio2: Mean diurnal range | °C | Bio12: Annual precipitation | mm |

| Bio3: Isothermality | Index | Bio13: Precipitation of the wettest month | mm |

| Bio4: Temperature seasonality | Index | Bio14: Precipitation of the driest month | mm |

| Bio5: Max temperature of the warmest month | °C | Bio15: Precipitation seasonality | Index |

| Bio6: Min temperature of the coldest month | °C | Bio16: Precipitation of the wettest quarter | mm |

| Bio7: Temperature annual range | °C | Bio17: Precipitation of the driest quarter | mm |

| Bio8: Mean temperature of the wettest quarter | °C | Bio18: Precipitation of the warmest quarter | mm |

| Bio9: Mean temperature of the driest quarter | °C | Bio19: Precipitation of the coldest quarter | mm |

| Bio10: Mean temperature of the warmest quarter | °C |

References

- Khan, R.; Iqbal, I.M.; Ullah, A.; Ullah, Z.; Khan, S.M. Invasive alien species: An emerging challenge for the biodiversity. In Biodiversity, Conservation and Sustainability in Asia: Volume 2: Prospects and Challenges in South and Middle Asia; Öztürk, M., Khan, S.M., Altay, V., Efe, R., Egamberdieva, D., Khassanov, F.O., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 459–471. [Google Scholar]

- Solarz, W.; Najberek, K.; Tokarska-Guzik, B.; Pietrzyk-Kaszyńska, A. Climate change as a factor enhancing the invasiveness of alien species. Environ. Socioecon. Stud. 2023, 11, 36–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haubrock, P.J.; Turbelin, A.J.; Cuthbert, R.N.; Novoa, A.; Taylor, N.G.; Angulo, E.; Ballesteros-Mejia, L.; Bodey, T.W.; Capinha, C.; Diagne, C. Economic costs of invasive alien species across Europe. NeoBiota 2021, 67, 153–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratt, C.F.; Constantine, K.L.; Murphy, S.T. Economic impacts of invasive alien species on African smallholder livelihoods. Glob. Food Secur. 2017, 14, 31–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barni, E.; Bacaro, G.; Falzoi, S.; Spanna, F.; Siniscalco, C. Establishing climatic constraints shaping the distribution of alien plant species along the elevation gradient in the Alps. Plant Ecol. 2012, 213, 757–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, W.; Peng, J.; Shrestha, N.; Bian, Z.; Yang, Y.; Liu, J.; Liu, X.; Huang, P.; Wu, J. Potential distribution and future shifts of invasive alien plants in China under climate change. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2025, 60, e03601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Huang, W.; Liu, Y.; Zhan, A. Perspectives of invasive alien species management in China. Ecol. Appl. 2024, 34, e2926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.; Li, Z.; Xu, Q.; Zhang, L. Mile-a-minute weed Mikania micrantha Kunth. In Biological Invasions and Its Management in China; Wan, F., Jiang, M., Zhan, A., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2017; Volume 2, pp. 131–141. [Google Scholar]

- Rai, P.K.; Singh, J.S. Ecological mechanisms and weed biology of world’s worst invasive alien plant Mikania micrantha: Policy measures for sustainable management. Weed Biol. Manag. 2025, 25, e70004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, F.; Peng, S.; Chen, B.; Liao, H.; Huang, Q.; Lin, Z.; Liu, G. Rapid evolution of dispersal-related traits during range expansion of an invasive vine Mikania micrantha. Oikos 2015, 124, 1023–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahariah, G.; Dutta, K.N.; Gam, S.; Talukdar, S.; Boro, D.; Deka, K.; Siangshai, S.; Bora, N.S. A review of the ethnopharmacology, phytochemistry and pharmacological activities of Mikania micrantha Kunth.: An Asian invasive weed. Vegetos 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clements, D.R.; Kato-Noguchi, H. Defensive mechanisms of Mikania micrantha likely enhance its invasiveness as one of the world’s worst alien species. Plants 2025, 14, 269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paudel, A.; Bhattarai, S.; Saud, P.; Pant, B.; Tian, N. Impact of Mikania micrantha invasion and perceptions of local communities in Central Nepal. Sustain. Environ. 2024, 10, 2362500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Day, M.D.; Clements, D.R.; Gile, C.; Senaratne, W.K.A.D.; Shen, S.; Weston, L.A.; Zhang, F. Biology and impacts of Pacific Islands invasive species. 13. Mikania micrantha Kunth (Asteraceae). Pac. Sci. 2016, 70, 257–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Le Roux, J.J.; Jiang, Z.; Sun, F.; Peng, C.; Li, W. Soil nitrogen dynamics and competition during plant invasion: Insights from Mikania micrantha invasions in China. New Phytol. 2021, 229, 3440–3452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, C.; Wang, Z.; Su, Y.; Wang, T. New insight into the rapid growth of the Mikania micrantha stem based on DIA proteomic and RNA-Seq analysis. J. Proteom. 2021, 236, 104126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, H.; Chen, Y.; Chen, J.; Ji, J.; He, H. Identification and comparison of allelopathic effects from leaf and flower volatiles of the invasive plants Mikania micrantha. Chemoecology 2021, 31, 355–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, S.; Xu, G.; Zhang, F.; Jin, G.; Liu, S.; Liu, M.; Chen, A.; Zhang, Y. Harmful effects and chemical control study of Mikania micrantha HBK in Yunnan, Southwest China. Afr. J. Agric. Res. 2013, 8, 5554–5561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.Y.; Ye, W.H.; Cao, H.L.; Feng, H.L. Mikania micrantha H. B. K. in China—An overview. Weed Res. 2004, 44, 42–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cock, M.J.W.; Ellison, C.A.; Evans, H.C.; Ooi, P.A.C. Can failure be turned into success for biological control of mile-a-minute weed (Mikania micrantha)? In Proceedings of the X International Symposium on Biological Control of Weeds, Bozeman, MT, USA, 4–14 July 1999; pp. 155–167. [Google Scholar]

- Rai, R.K.; Sandilya, M.; Subedi, R. Controlling Mikania micrantha HBK: How effective manual cutting is? J. Ecol. Environ. 2012, 35, 235–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Bi, P. A study on life cycle and response to herbicides of Mikania micrantha. Acta Sci. Nat. Univ. Sunyatseni 1994, 33, 88–95. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, A.; Hu, X.; Yao, S.; Yu, M.; Ying, Z. Alien, naturalized and invasive plants in China. Plants 2021, 10, 2241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clements, D.R.; Jones, V.L. Rapid evolution of invasive weeds under climate change: Present evidence and future research needs. Front. Agron. 2021, 3, 664034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turbelin, A.; Catford, J.A. Invasive plants and climate change. In Climate Change: Observed Impacts on Planet Earth, 3rd ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021; pp. 515–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, A.E.; Jarnevich, C.S.; Beaury, E.M.; Engelstad, P.S.; Teich, N.B.; LaRoe, J.M.; Bradley, B.A. Shifting hotspots: Climate change projected to drive contractions and expansions of invasive plant abundance habitats. Divers. Distrib. 2024, 30, 41–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, J.A.; Shea, K. Warming and shifting phenology accelerate an invasive plant life cycle. Ecology 2021, 102, e03219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebrewahid, Y.; Abrehe, S.; Meresa, E.; Eyasu, G.; Abay, K.; Gebreab, G.; Kidanemariam, K.; Adissu, G.; Abreha, G.; Darcha, G. Current and future predicting potential areas of Oxytenanthera abyssinica (A. Richard) using MaxEnt model under climate change in Northern Ethiopia. Ecol. Process. 2020, 9, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.T.; Gliottone, I.; Pham, M.P. Current and future predicting habitat suitability map of Cunninghamia konishii Hayata using MaxEnt model under climate change in Northern Vietnam. Eur. J. Ecol. 2021, 7, 2155–2169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, S.J.; Dudík, M. Modeling of species distributions with MaxEnt: New extensions and a comprehensive evaluation. Ecography 2008, 31, 161–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Yan, L.; Shen, H.; Guan, R.; Ge, Q.; Huang, L.; Rohani, E.R.; Ou, J.; Han, R.; Tong, X. Potentially suitable geographical area for Pulsatilla chinensis Regel under current and future climatic scenarios based on the MaxEnt model. Front. Plant Sci. 2025, 16, 1538566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valavi, R.; Guillera-Arroita, G.; Lahoz-Monfort, J.J.; Elith, J. Predictive performance of presence-only species distribution models: A benchmark study with reproducible code. Ecol. Monogr. 2022, 92, e01486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rufai, A.B.; Olatunji, O.A.; Okunlola, G.O.; Adebisi, S.O.; Raimi, I.O.; Komolafe, E.T.; Chukwuma, E.C.; Jimoh, M.A. Predicting the potential habitat suitability of invasive Chromolaena odorata and Tithonia differsifolia in Nigeria’s urban ecosystems using MaxEnt. Ecol. Front. 2025, in press. [CrossRef]

- Waheed, M.; Haq, S.M.; Arshad, F.; Vitasović-Kosić, I.; Bussmann, R.W.; Hashem, A.; Abd-Allah, E.F. Xanthium strumarium L., an invasive species in the subtropics: Prediction of potential distribution areas and climate adaptability in Pakistan. BMC Ecol. Evol. 2024, 24, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, X.; Ze, S.; Zhou, X.; Ji, M. Distribution prediction and assessment of Mikania micrantha in Yunnan province based on MaxEnt model. Guangdong Agric. Sci. 2015, 42, 159–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez, P.A.; Graham, C.H.; Master, L.L.; Albert, D.L. The effect of sample size and species characteristics on performance of different species distribution modeling methods. Ecography 2006, 29, 773–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muscarella, R.; Galante, P.J.; Soley-Guardia, M.; Boria, R.A.; Kass, J.M.; Uriarte, M.; Anderson, R.P. ENMeval: An R package for conducting spatially independent evaluations and estimating optimal model complexity for MaxEnt ecological niche models. Methods Ecol. Evol. 2014, 5, 1198–1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimmett, L.; Whitsed, R.; Horta, A. Presence-only species distribution models are sensitive to sample prevalence: Evaluating models using spatial prediction stability and accuracy metrics. Ecol. Model. 2020, 431, 109194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natale, E.; Zalba, S.M.; Reinoso, H. Presence—Absence versus invasive status data for modelling potential distribution of invasive plants: Saltcedar in Argentina. Écoscience 2013, 20, 161–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, C.; Li, M.; Jim, C.Y.; Liu, D. Spatio-temporal patterns of an invasive species Mimosa bimucronata (DC.) Kuntze under different climate scenarios in China. Front. For. Glob. Chang. 2023, 6, 1144829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, E.; Ji, C.; Liang, M.; Zhu, J.; Tang, Z.; Fang, J. Climatic and non-climatic effects on species occurrence and abundance shift in different trends along elevational gradients. J. Plant Ecol. 2025, 18, rtaf122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; He, Y.; Zhang, W.; Chen, L.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, X.; Dawson, W.; Ding, J. Greater chemical signaling in root exudates enhances soil mutualistic associations in invasive plants compared to natives. New Phytol. 2022, 236, 1140–1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q.-H.Y.; Qi-He, Y.; Wan-Hui, Y.E.; Xiong, D.; Hong-Ling, C.A.O.; Yun, Z.; Kai, Y. Seed germination eco-physiology of Mikania micrantha H.B.K. Bot. Bull. Acad. Sin. 2005, 46, 293–299. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, L.; Sun, O.J.; Sang, W.; Li, Z.; Ma, K. Predicting the spatial distribution of an invasive plant species (Eupatorium adenophorum) in China. Landsc. Ecol. 2007, 22, 1143–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Wang, Y.; Peng, P.; Wang, G.; Zhao, G.; Zhou, Y.; Tang, Z. Mapping the distribution and dispersal risks of the alien invasive plant Ageratina adenophora in China. Diversity 2022, 14, 915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez, T.M.; Feeley, K.J. Weak phylogenetic and climatic signals in plant heat tolerance. J. Biogeogr. 2021, 48, 91–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dev, W.; Sultana, F.; He, S.; Hu, D.; Geng, X.; Du, X.; Iqbal, B. Effects of high temperatures on pollen germination and physio-morphological traits in upland cotton (Gossypium hirsutum L.). J. Agron. Crop Sci. 2025, 211, e70080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Kong, F.; Yin, H.; Middel, A.; Green, J.K.; Liu, H. Green roof plant physiological water demand for transpiration under extreme heat. Urban For. Urban Green. 2024, 98, 128411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, M.; Chen, M.; Zhang, J.; Peng, C. Stem-centered drought tolerance in Mikania micrantha during the dry season. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 9722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, C.; Huang, B.; Jim, C.Y.; Han, W.; Liu, D. Predicting differential habitat suitability of Rhodomyrtus tomentosa under current and future climate scenarios in China. For. Ecol. Manag. 2021, 501, 119696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, M.; Yu, H.; Li, W.; Yin, A.; Cui, Y.; Tian, X. Flooding with shallow water promotes the invasiveness of Mikania micrantha. Ecol. Evol. 2019, 9, 9177–9184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Liu, S.C.; Liu, R.; Shiu, C.J.; He, C.; Zhong, X. Observed changes in precipitation extremes and effects of tropical cyclones in South China during 1955–2013. Int. J. Climatol. 2019, 39, 2677–2684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orsenigo, S.; Mondoni, A.; Rossi, G.; Abeli, T. Some like it hot and some like it cold, but not too much: Plant responses to climate extremes. Plant Ecol. 2014, 215, 677–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Xing, C.; Zhu, J. Analysis of climate characteristics in Hainan Island. J. Trop. Biol. 2022, 13, 315–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H. Flora and vegetation of Yunnan are shaped by geological events and monsoon climate. Biodivers. Sci. 2023, 31, 23262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, A.K.; Reddy, C.S.; Dewanji, A. Impact assessment on floral composition and spread potential of Mikania micrantha H.B.K. in an urban scenario. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. India Sect. B-Biol. Sci. 2017, 87, 777–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Arshad, M.A.; Mahmood, A. Analysis on international competitiveness of service trade in the Guangdong–Hong Kong–Macao Greater Bay Area based on using the entropy and gray correlation methods. Entropy 2021, 23, 1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaverková, M.D.; Paleologos, E.K.; Adamcová, D.; Podlasek, A.; Pasternak, G.; Červenková, J.; Skutnik, Z.; Koda, E.; Winkler, J. Municipal solid waste landfill: Evidence of the effect of applied landfill management on vegetation composition. Waste Manag. Res. 2022, 40, 1402–1411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Li, Y.; Zhang, S.; Lin, R.; Chen, M.; Feng, L. Driving effects of land use and landscape pattern on different spontaneous plant life forms along urban river corridors in a fast-growing city. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 876, 162775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes, L.; Meireles, C.; Pinto Gomes, C.; Almeida Ribeiro, N. Propagation model of invasive species: Road systems as dispersion facilitators. Res. Ecol. 2019, 2, 44–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robeck, P.; Essl, F.; van Kleunen, M.; Pyšek, P.; Pergl, J.; Weigelt, P.; Mesgaran, M.B. Invading plants remain undetected in a lag phase while they explore suitable climates. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2024, 8, 477–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Liao, Z.; Jiang, H.; Tu, W.; Wu, N.; Qiu, X.; Zhang, Y. Climatic variability caused by topographic barrier prevents the northward spread of invasive Ageratina adenophora. Plants 2022, 11, 3108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ji, M.; Ze, S.; Tang, S.; Hu, L.; Li, J. Independent origins of populations from Dehong State, Yunnan Province, and the multiple introductions and post-introduction admixture sources of mile-a-minute (Mikania micrantha) in China. Weed Sci. 2021, 69, 439–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vojík, M.; Sádlo, J.; Petřík, P.; Pyšek, P.; Man, M.; Pergl, J. Two faces of parks: Sources of invasion and habitat for threatened native plants. Preslia 2021, 92, 353–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikkel, E.; Clements, D.R.; Anderson, D.; Williams, J.L. Regional habitat suitability for aquatic and terrestrial invasive plant species may expand or contract with climate change. Biol. Invasions 2023, 25, 3805–3822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osland, M.J.; Stevens, P.W.; Lamont, M.M.; Brusca, R.C.; Hart, K.M.; Waddle, J.H.; Langtimm, C.A.; Williams, C.M.; Keim, B.D.; Terando, A.J.; et al. Tropicalization of temperate ecosystems in North America: The northward range expansion of tropical organisms in response to warming winter temperatures. Glob. Change Biol. 2021, 27, 3009–3034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Price, J.; Warren, R.; Forstenhäusler, N.; Jenkins, R.; Graham, E. Assessing the potential risks of climate change on the natural capital of six countries resulting from global warming of 1.5 to 4 °C above pre-industrial levels. Clim. Chang. 2024, 177, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feeley, K.J.; Bravo-Avila, C.; Fadrique, B.; Perez, T.M.; Zuleta, D. Climate-driven changes in the composition of New World plant communities. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2020, 10, 965–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Zhu, Y.; Wang, L.; Li, Z.; Shi, Z.; Yang, X.; Yahdjian, L. Plant invasion risk assessment in Argentina’s arid and semi-arid rangelands. J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 377, 124648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Yang, Z.; Wang, P.; Xu, C. Long-term high temperature stress decreases the photosynthetic capacity and induces irreversible damage in chrysanthemum seedlings. Hortic. Sci. 2023, 50, 159–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, X.; Ma, J.; Cai, H.; Wang, Y. Carbon balance and controlling factors in a summer maize agroecosystem in the Guanzhong Plain, China. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2023, 103, 1761–1774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lancaster, L.T.; Humphreys, A.M. Global variation in the thermal tolerances of plants. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 13580–13587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rainford, J.; Crowe, A.; Jones, G.; Van Den Berg, F. Early warning systems in biosecurity; translating risk into action in predictive systems for invasive alien species. Emerg. Top. Life Sci. 2020, 4, 453–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Yu, Y.; Guan, Z.; Wang, X. Dominant coupling mode of SST in maritime continental region and East Asian summer monsoon Circulation. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2022, 127, e2022JD036739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larson, C.D.; Pollnac, F.W.; Schmitz, K.; Rew, L.J. Climate change and micro-topography are facilitating the mountain invasion by a non-native perennial plant species. NeoBiota 2021, 65, 23–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shabani, F.; Ahmadi, M.; Kumar, L.; Solhjouy-fard, S.; Shafapour Tehrany, M.; Shabani, F.; Kalantar, B.; Esmaeili, A. Invasive weed species’ threats to global biodiversity: Future scenarios of changes in the number of invasive species in a changing climate. Ecol. Indic. 2020, 116, 106436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.; Lu, Y.; Fang, Y.; Xin, X.; Li, L.; Li, W.; Jie, W.; Zhang, J.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, L.; et al. The Beijing Climate Center Climate System Model (BCC-CSM): The main progress from CMIP5 to CMIP6. Geosci. Model Dev. 2019, 12, 1573–1600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, X.; Chen, X.; Dai, Y.; Hu, G. Climate sensitivity and feedbacks of BCC-CSM to idealized CO2 forcing from CMIP5 to CMIP6. J. Meteorol. Res. 2020, 34, 865–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shetty, S.; Umesh, P.; Shetty, A. The effectiveness of machine learning-based multi-model ensemble predictions of CMIP6 in Western Ghats of India. Int. J. Climatol. 2023, 43, 5029–5054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobson, R.; Challinor, A.J.; Cheke, R.A.; Jennings, S.; Willis, S.G.; Dallimer, M. DYNAMICSDM: An R package for species geographical distribution and abundance modelling at high spatiotemporal resolution. Methods Ecol. Evol. 2023, 14, 1190–1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poorter, H.; Knopf, O.; Wright, I.J.; Temme, A.A.; Hogewoning, S.W.; Graf, A.; Cernusak, L.A.; Pons, T.L. A meta-analysis of responses of C3 plants to atmospheric CO2: Dose–response curves for 85 traits ranging from the molecular to the whole-plant level. New Phytol. 2022, 233, 1560–1596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fick, S.E.; Hijmans, R.J. WorldClim 2: New 1-km spatial resolution climate surfaces for global land areas. Int. J. Climatol. 2017, 37, 4302–4315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindenmayer, D.B.; Lavery, T.; Scheele, C.B. Why we need to invest in large-scale, long-term monitoring programs in landscape ecology and conservation biology. Curr. Landsc. Ecol. Rep. 2022, 7, 137–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reaser, J.K.; Burgiel, S.W.; Kirkey, J.; Brantley, K.A.; Veatch, S.D.; Burgos-Rodríguez, J. The early detection of and rapid response (EDRR) to invasive species: A conceptual framework and federal capacities assessment. Biol. Invasions 2020, 22, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Liu, X.; Zeng, H.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, L. Public education improves farmers knowledge and management of invasive alien species. Biol. Invasions 2021, 23, 2003–2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seebens, H.; Essl, F.; Hulme, P.E.; van Kleunen, M. Development of pathways of global plant invasions in space and time. In Global Plant Invasions; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 53–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davinack, A.A. The double-edged sword of artificial intelligence in invasion biology. Biol. Invasions 2025, 27, 230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallien, L.; Mazel, F.; Lavergne, S.; Renaud, J.; Douzet, R.; Thuiller, W. Contrasting the effects of environment, dispersal and biotic interactions to explain the distribution of invasive plants in alpine communities. Biol. Invasions 2015, 17, 1407–1423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanders, S.K.D.; van Kleunen, M.; Allan, E.; Thakur, M.P. Effects of extreme drought on the invasion dynamics of non-native plants. Trends Plant Sci. 2025, 30, 291–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosas-Chavoya, M.; Gallardo-Salazar, J.L.; López-Serrano, P.M.; Alcántara-Concepción, P.C.; León-Miranda, A.K. QGIS a constantly growing free and open-source geospatial software contributing to scientific development. Cuad. Investig. Geográfica 2022, 48, 197–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammer, Ø.; Harper, D.A.T. Past: Paleontological statistics software package for education and data analysis. Palaeontol. Electron. 2001, 4, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Merow, C.; Smith, M.J.; Silander Jr, J.A. A practical guide to MaxEnt for modeling species’ distributions: What it does, and why inputs and settings matter. Ecography 2013, 36, 1058–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Climate Scenario | Unsuitable | Low | Moderate | Good | Excellent |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Current | 924.5 | 15.9 | 10.1 | 8.3 | 3.6 |

| SSP1-2.6 (2050s) | 921.1 | 14.8 | 11.9 | 9.6 | 4.3 |

| SSP1-2.6 (2070s) | 922.5 | 14.4 | 11.7 | 8.8 | 4.3 |

| SSP2-4.5 (2050s) | 923.4 | 13.9 | 11.5 | 8.9 | 4.1 |

| SSP2-4.5 (2070s) | 924.0 | 13.8 | 9.8 | 9.0 | 5.1 |

| SSP3-7.0 (2050s) | 922.5 | 13.8 | 12.5 | 9.0 | 4.0 |

| SSP3-7.0 (2070s) | 924.4 | 11.7 | 11.7 | 9.5 | 4.4 |

| Average a | 923.0 | 13.7 | 11.5 | 9.1 | 4.4 |

| Change b (%) | −0.2 | −13.6 | 14.0 | 10.0 | 21.3 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Xie, C.; Chen, Z.; Yu, M.; Jim, C.Y. Impact of Climate Change on the Invasion of Mikania micrantha Kunth in China: Predicting Future Distribution Using MaxEnt Modeling. Plants 2025, 14, 3694. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14233694

Xie C, Chen Z, Yu M, Jim CY. Impact of Climate Change on the Invasion of Mikania micrantha Kunth in China: Predicting Future Distribution Using MaxEnt Modeling. Plants. 2025; 14(23):3694. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14233694

Chicago/Turabian StyleXie, Chunping, Zhiquan Chen, Mianting Yu, and Chi Yung Jim. 2025. "Impact of Climate Change on the Invasion of Mikania micrantha Kunth in China: Predicting Future Distribution Using MaxEnt Modeling" Plants 14, no. 23: 3694. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14233694

APA StyleXie, C., Chen, Z., Yu, M., & Jim, C. Y. (2025). Impact of Climate Change on the Invasion of Mikania micrantha Kunth in China: Predicting Future Distribution Using MaxEnt Modeling. Plants, 14(23), 3694. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14233694