The Effects of Photoperiodic Transcription Factor OsPRR37 on Grain Filling and Starch Synthesis During Rice Caryopsis Development

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

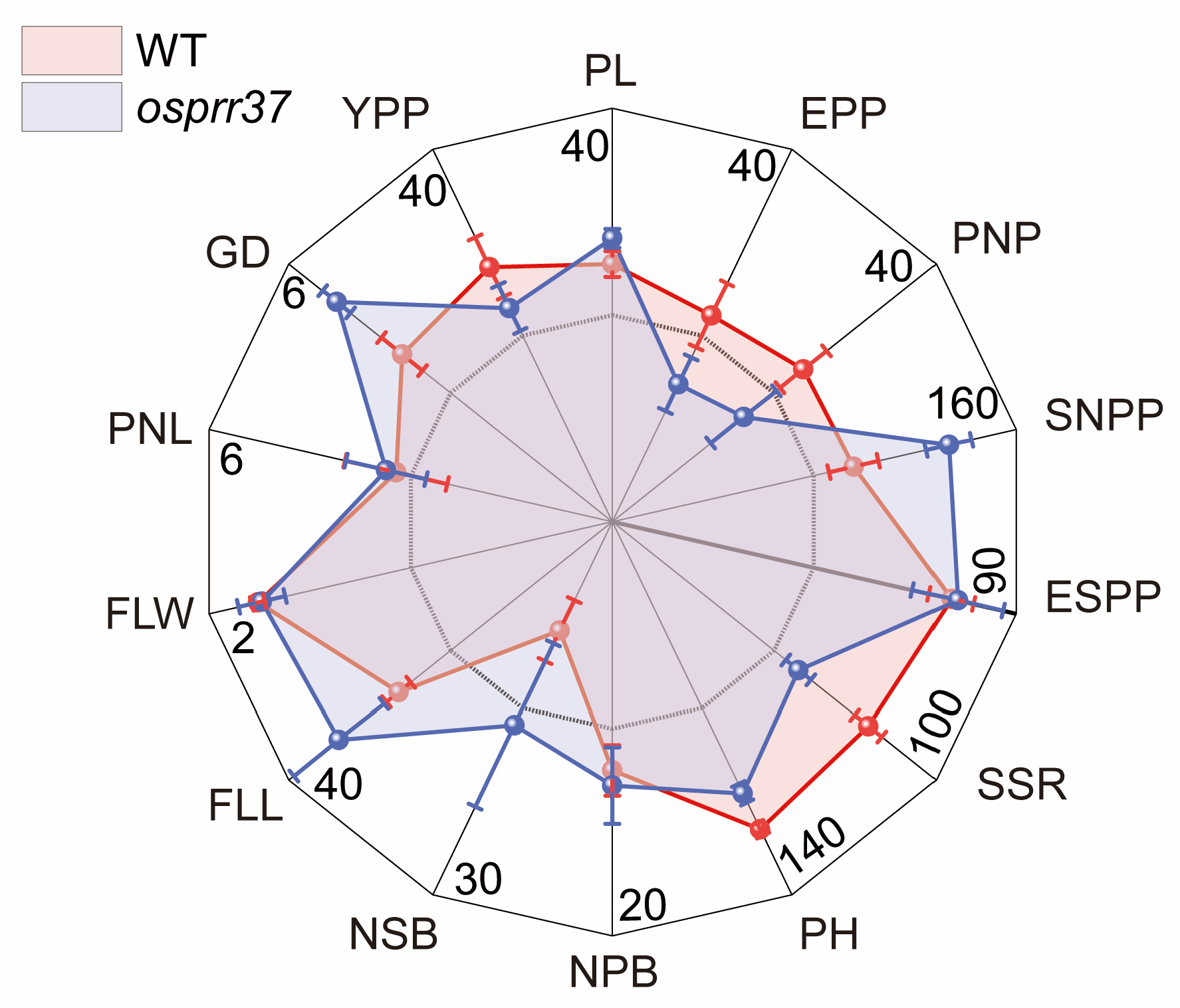

2.1. Effect of OsPRR37 on Agronomic Traits

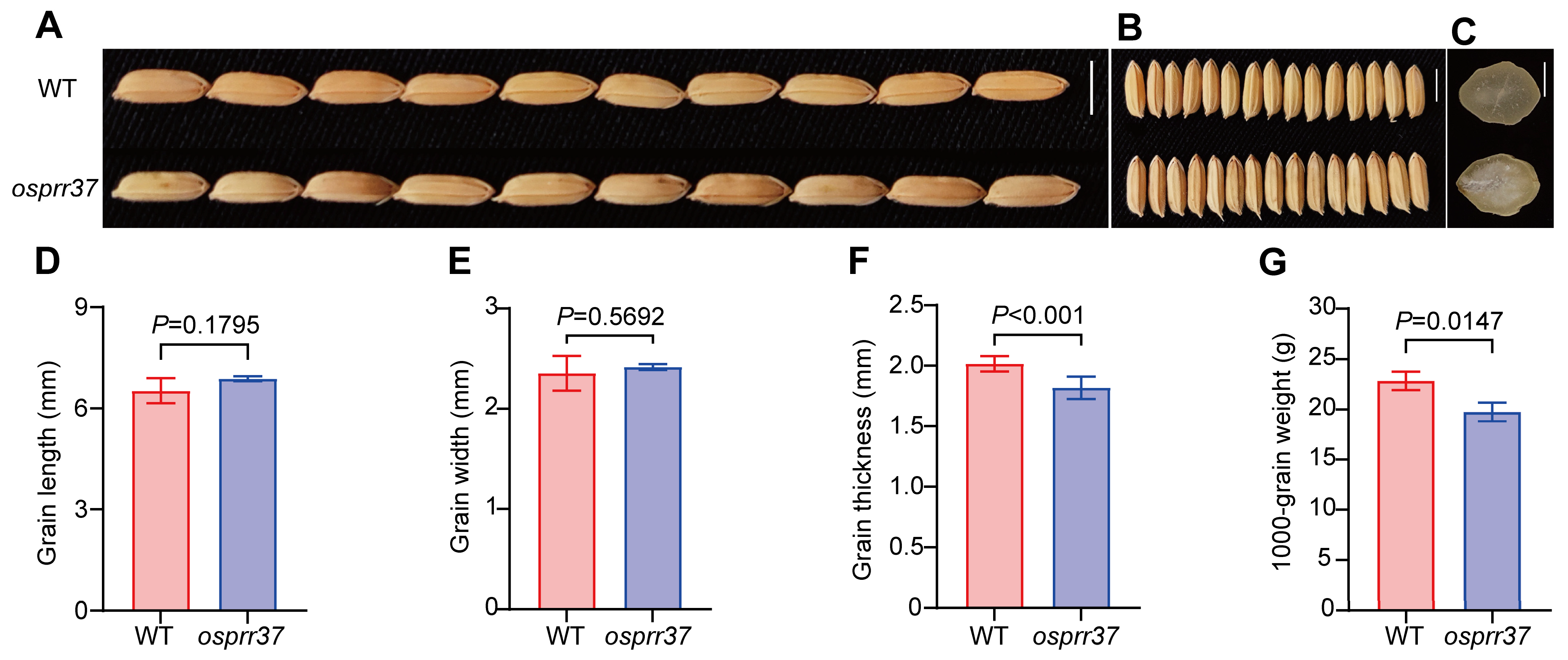

2.2. Effect of OsPRR37 on Seed Morphology

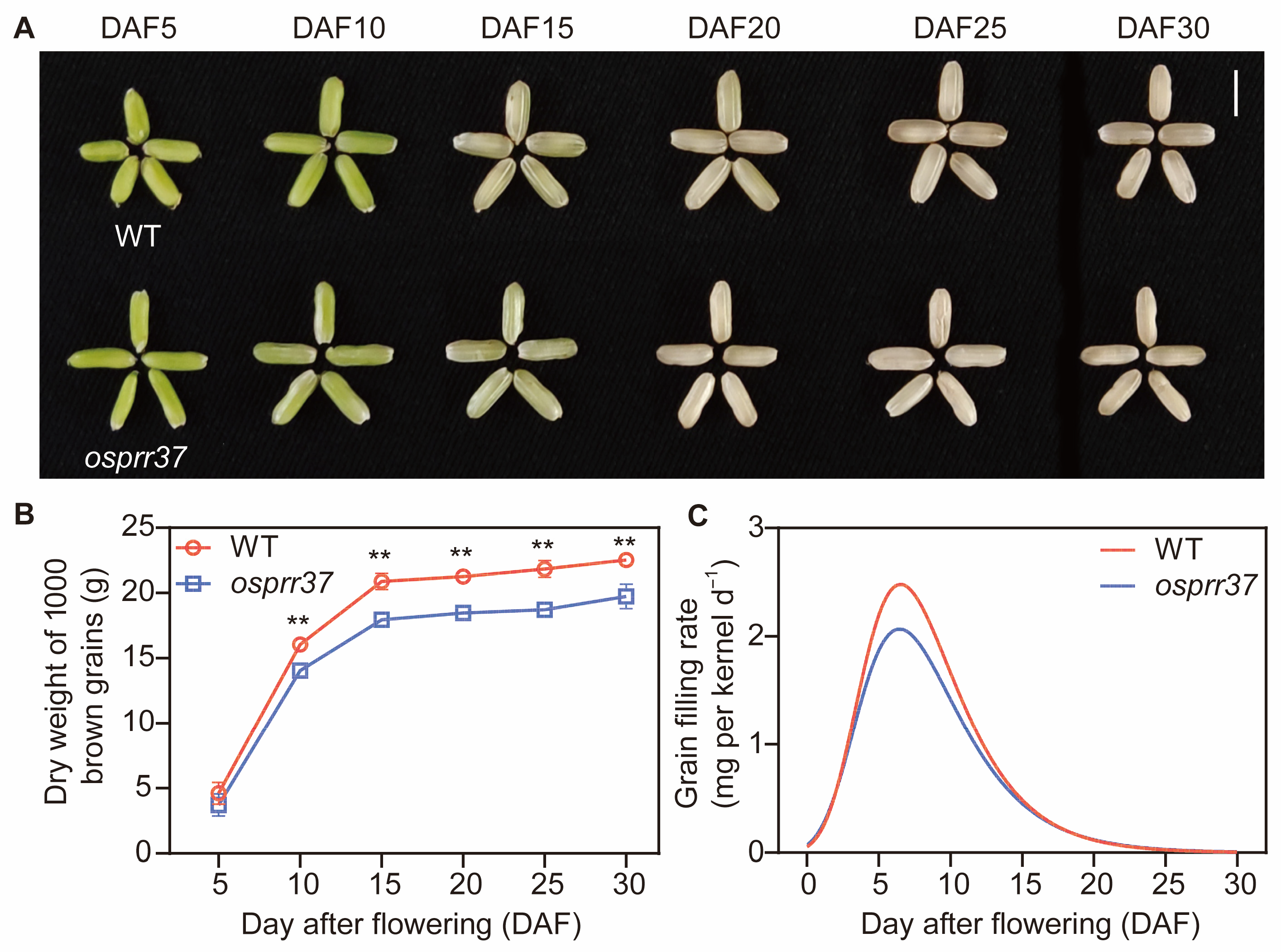

2.3. The Rice osprr37 Mutants Display Defects in Grain Filling

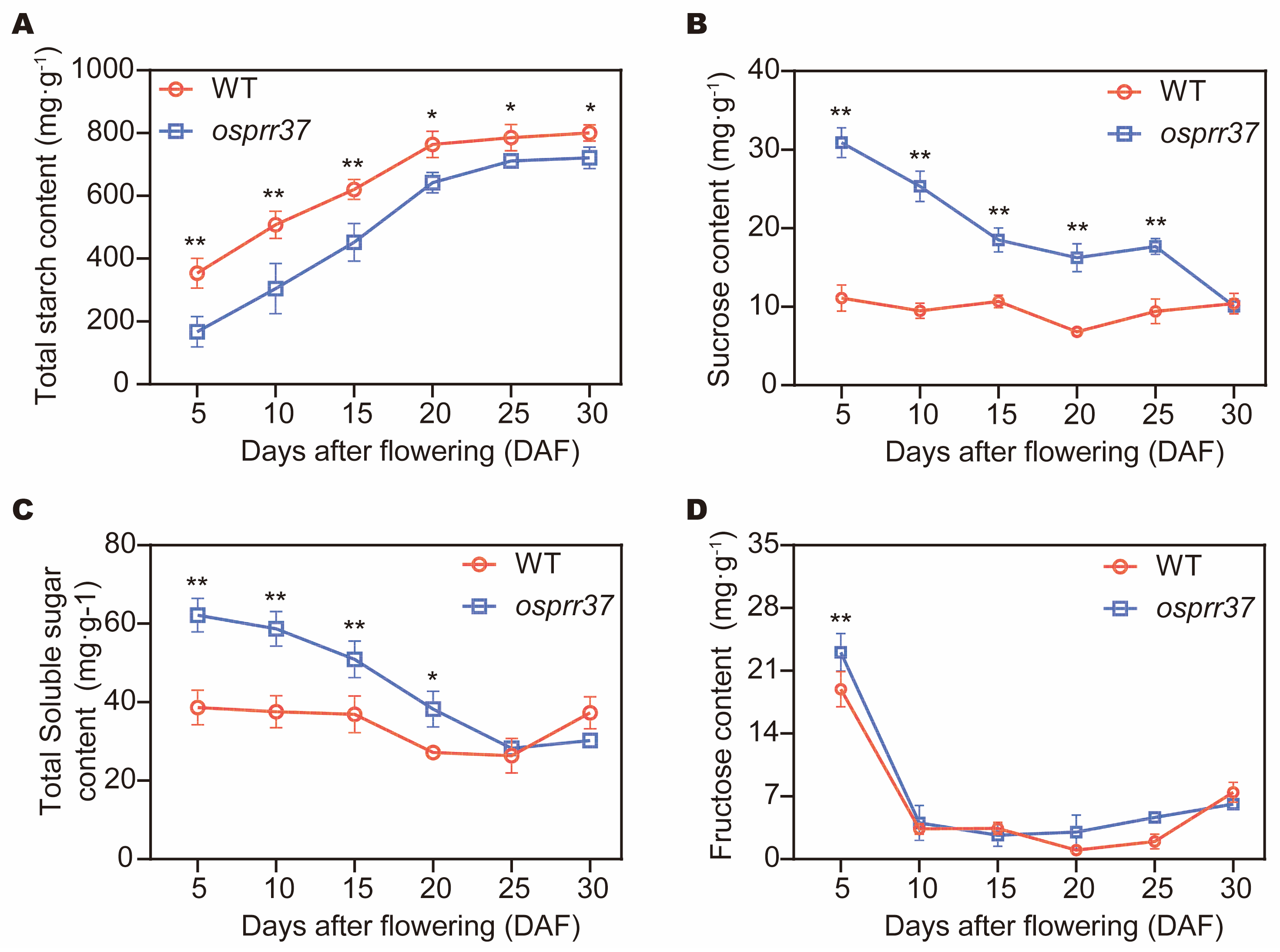

2.4. Effect of OsPRR37 on Carbohydrate Accumulation

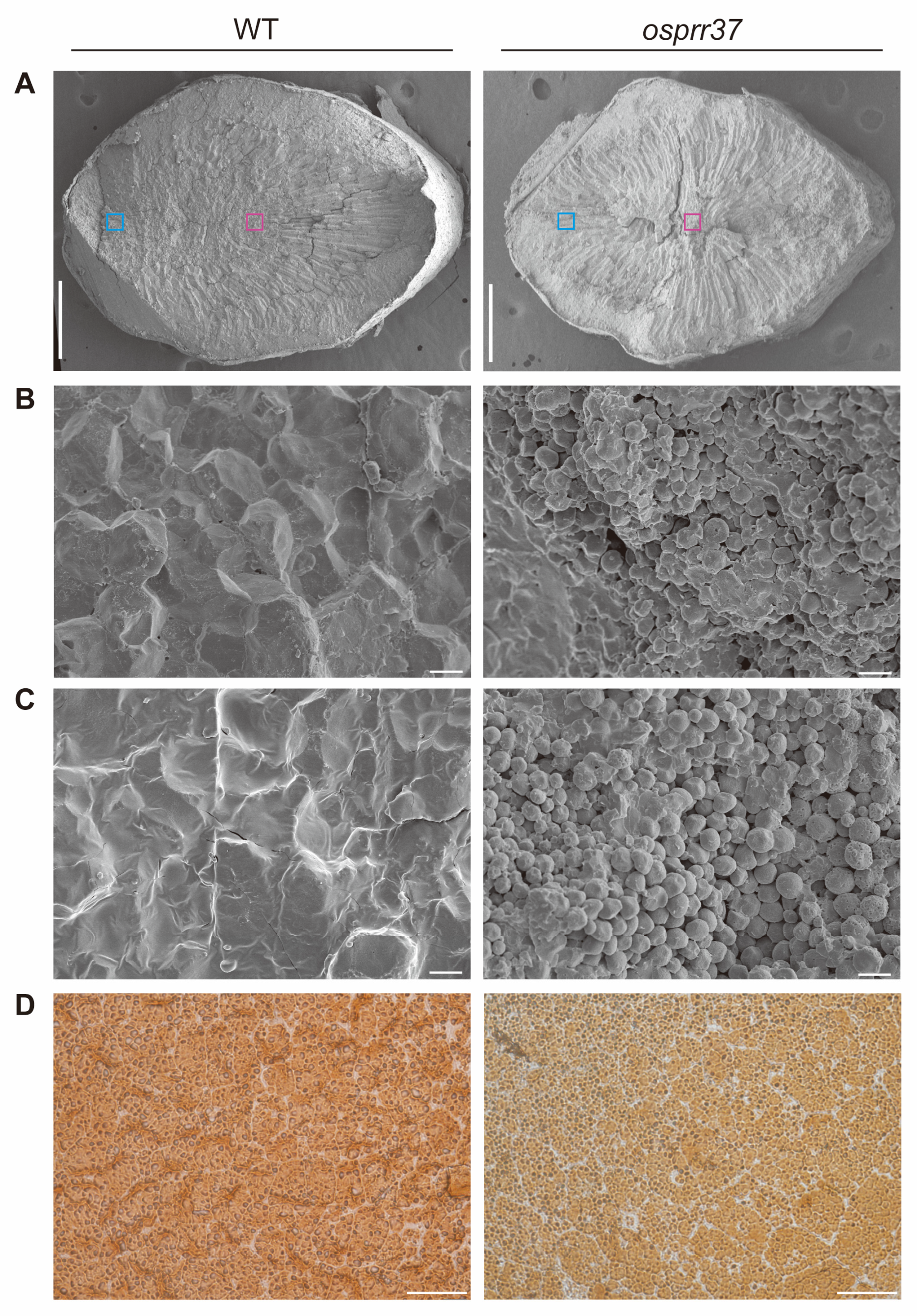

2.5. The Structure of Starch Compound Granules Is Abnormal in osprr37 Endosperm Cells

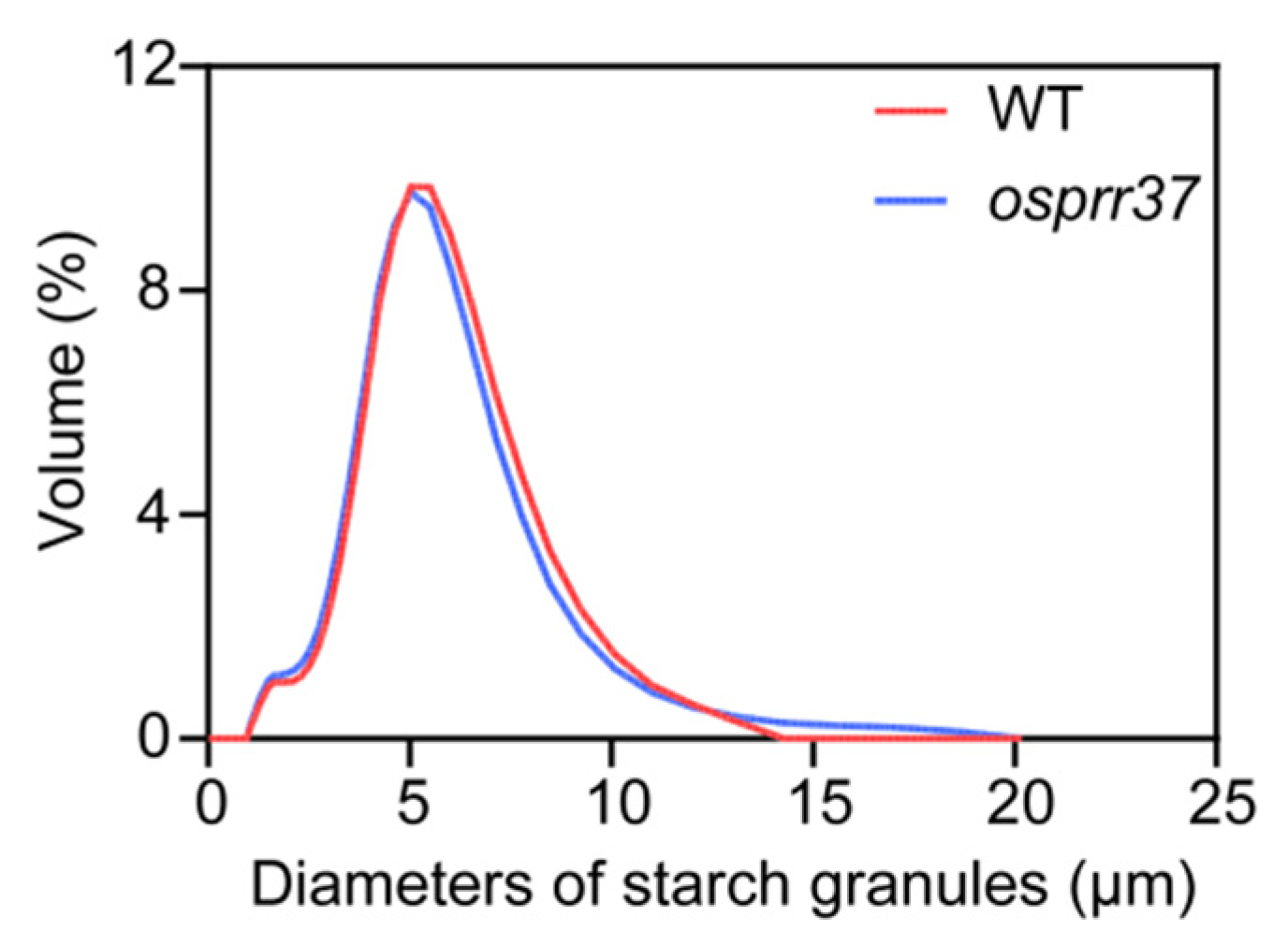

2.6. Effect of OsPRR37 on Starch Particle Size

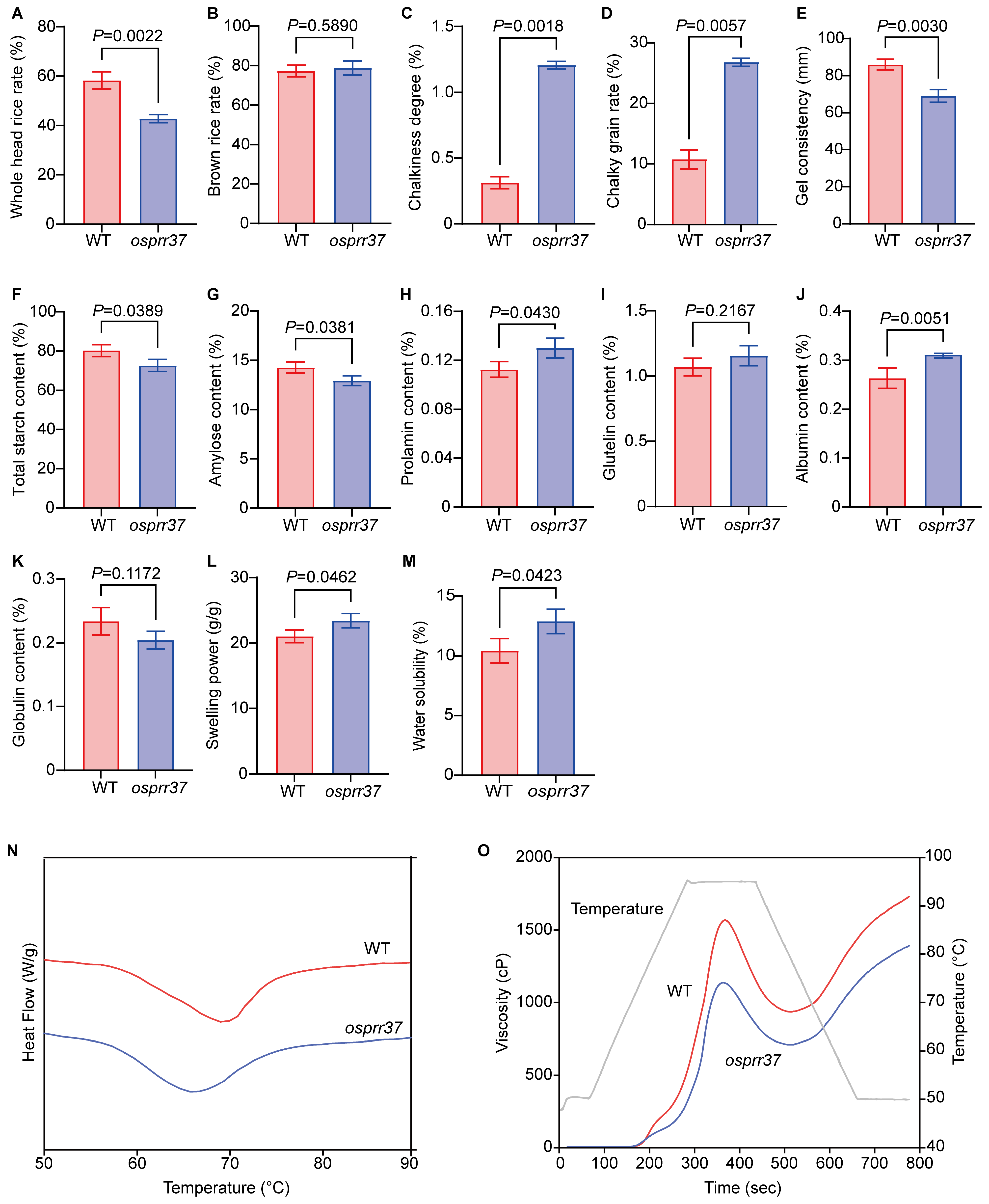

2.7. Effect of OsPRR37 on Rice Grain Quality

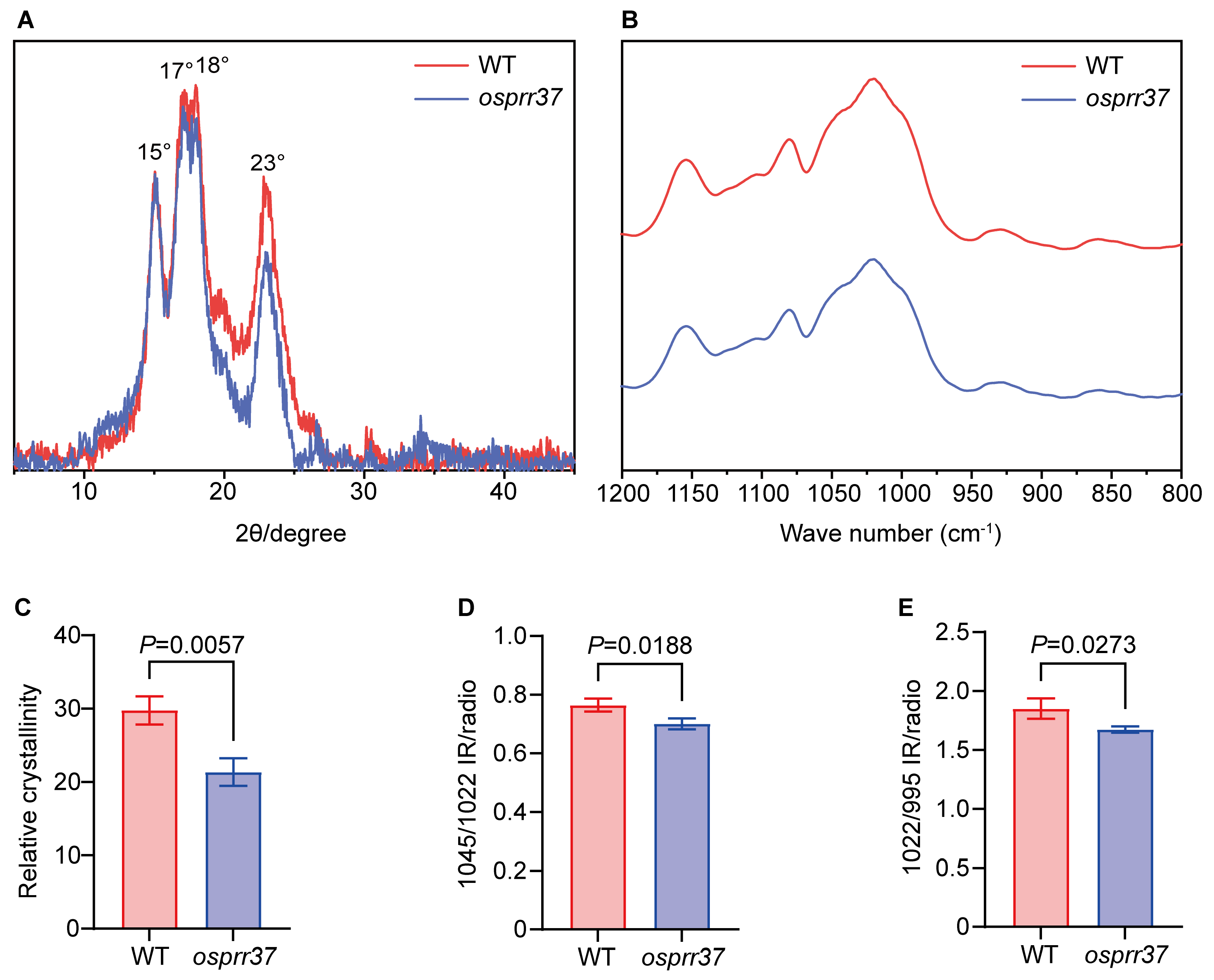

2.8. Starch Physicochemical Properties in osprr37 Grain

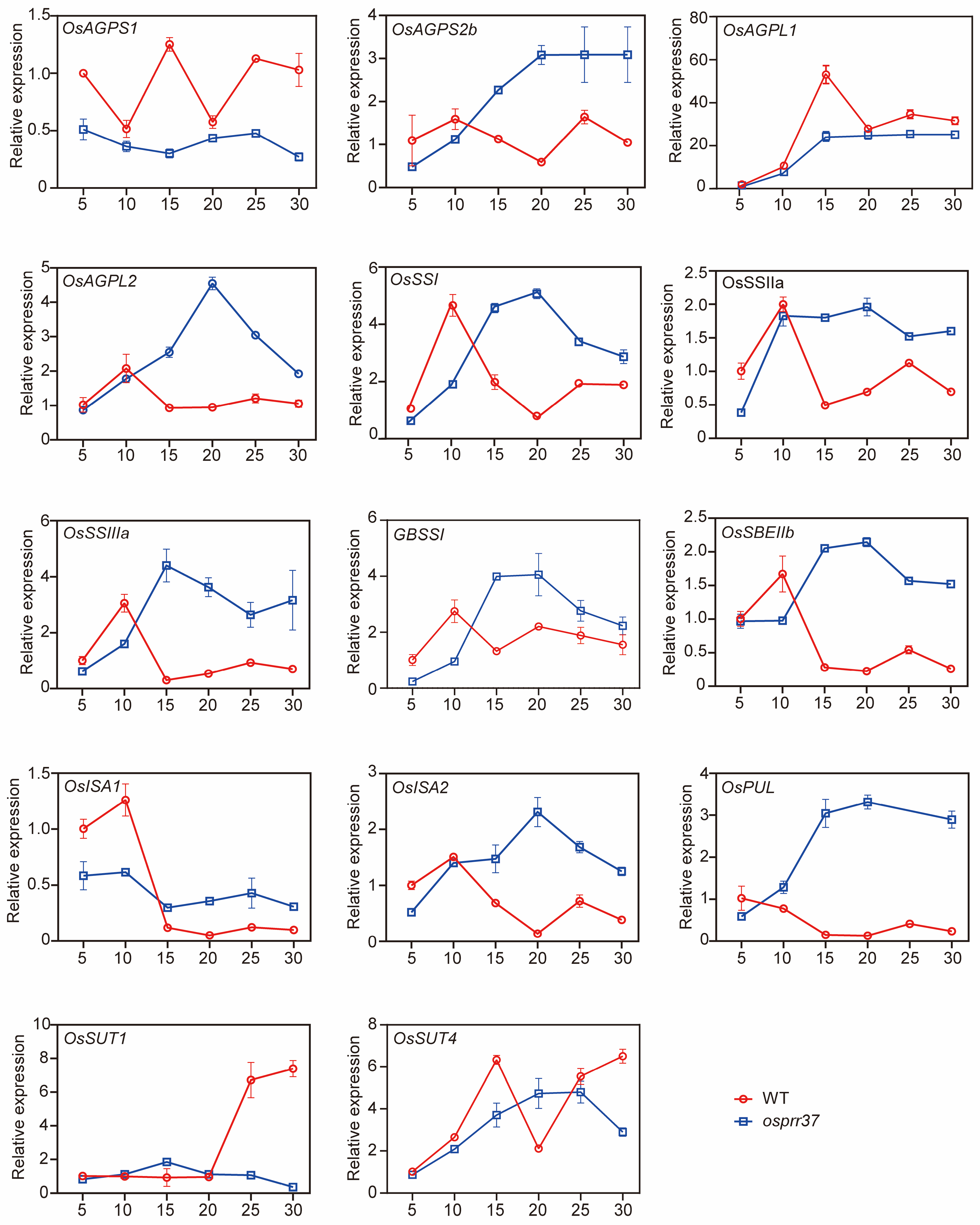

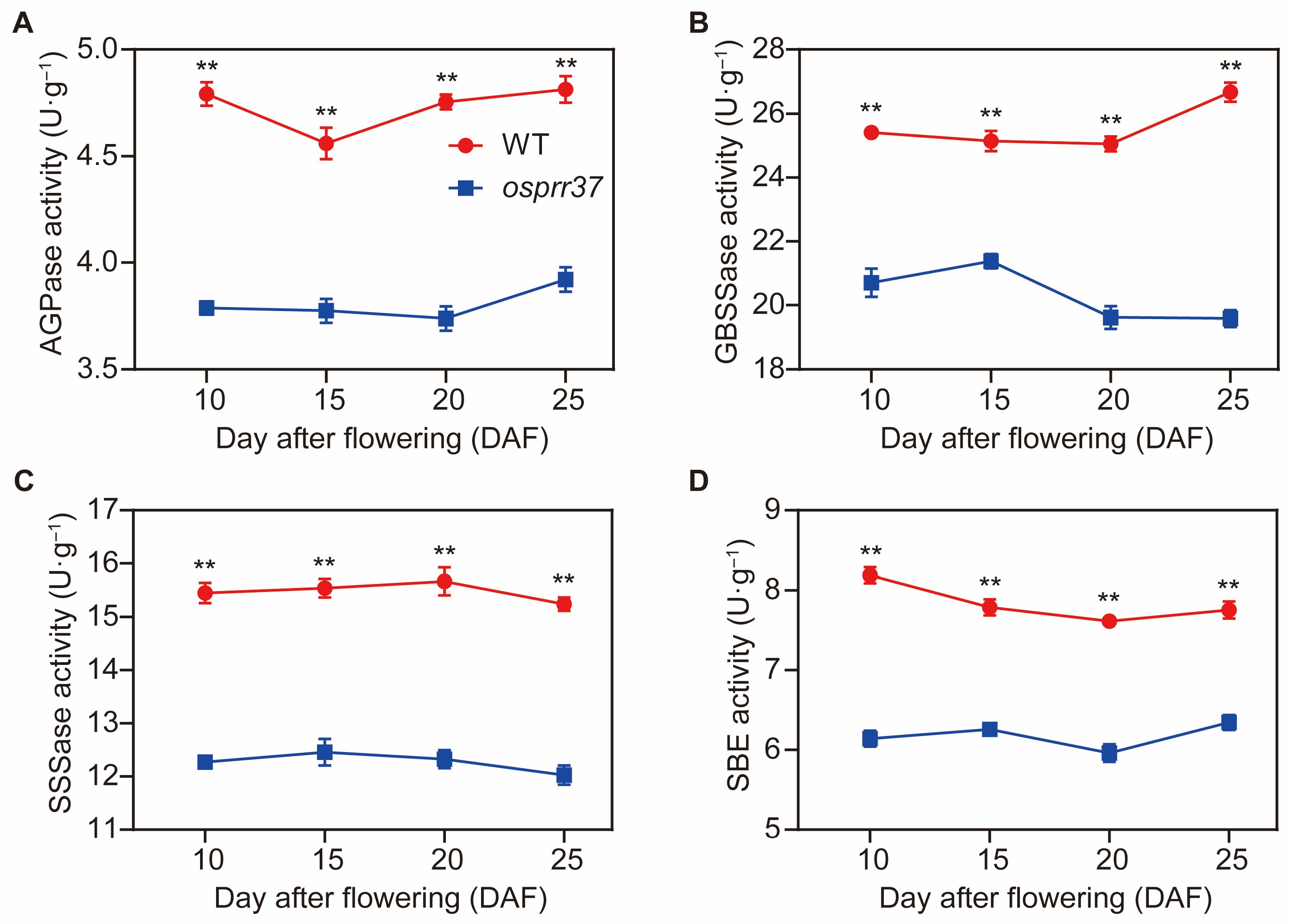

2.9. The Expression Pattern of Starch Synthesis-Related Genes and Enzyme Activities

3. Discussion

3.1. OsPRR37 Controls Rice Grain Filling and Starch Biosynthesis During Caryopsis Development

3.2. Effects of Assimilate Accumulation on Rice Quality Traits

3.3. OsPRR37 Regulates Starch Molecular Architecture and Functional Properties

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Plant Materials and Growth Condition

4.2. Determination of Agronomic Traits and Grain Filling Rate

4.3. Determination of Carbohydrate Content

4.4. Analysis of Starch Physicochemical Properties

4.5. Determination of Storage Protein Content

4.6. Analysis of Starch Granule Morphology and Size Distribution

4.7. Starch Crystallinity Analysis

4.8. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectrum Analysis

4.9. Thermal Properties Analysis

4.10. Pasting Properties Analysis

4.11. RNA Extraction and Real-Time PCR Analysis

4.12. Enzyme Extract and Activity Assay

4.13. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| SSRGs | starch synthesis-related genes |

| PL | panicle length |

| EPP | effective panicles per plant |

| PNP | panicle number per plant |

| SNPP | spikelet number per panicle |

| ESPP | effective spikelet number per panicle |

| SSR | seed setting rate |

| PH | plant height |

| NPB | number of primary branches |

| NSB | number of secondary branches |

| FLL | flag leaf length |

| FLW | flag leaf width |

| PNL | panicle neck length |

| GD | grain density |

| YPP | yield per plant |

| ECQ | eating and cooking quality |

| UPR | unfold protein change |

| pseudo-response regulator | PRR |

| WT | wild-type |

| SEM | scanning electron microscopy |

| DAF | days after flowering |

| DSC | differential scanning calorimetry |

| SSPs | seed storage proteins |

| RVA | Rapid Visco Analyzer |

| XRD | X-ray diffraction |

| AGPase | ADP-glucose pyrophosphorylase |

| SS | starch synthase |

| SBE | starch branching enzyme |

| DBE | starch debranching enzyme |

| PV | peak viscosity |

| FV | final viscosity |

References

- Ahmad, M.S.; Wu, B.; Wang, H.; Kang, D. Identification of Drought Tolerance on the Main Agronomic Traits for Rice (Oryza sativa L. ssp. Japonica) Germplasm in China. Agronomy 2021, 11, 1740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandeputte, G.E.; Delcour, J.A. From Sucrose to Starch Granule to Starch Physical Behaviour: A Focus on Rice Starch. Carbohydr. Polym. 2004, 58, 245–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, M.; Fitzgerald, M.A. Proteins in Rice Grains Influence Cooking Properties! J. Cereal Sci. 2002, 36, 285–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Wang, F.; Zhang, Z.; Terry, N. Optimization of Polysaccharide Production from Cordyceps Militaris by Solid-State Fermentation on Rice and Its Antioxidant Activities. Foods 2019, 8, 590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Lu, Y.; Pan, L.; Fan, X.; Li, Q.; Huang, L.; Zhao, D.; Zhang, C.; Liu, Q. The Underlying Physicochemical Properties and Starch Structures of Indica Rice Grains with Translucent Endosperms under Low-Moisture Conditions. Foods 2022, 11, 1378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzgerald, M.A.; McCouch, S.R.; Hall, R.D. Not Just a Grain of Rice: The Quest for Quality. Trends Plant Sci. 2009, 14, 133–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.; Wang, L.; Xiao, Y.; Wang, F.; Zhang, G.; Tang, W.; Deng, H. Grain Quality Characterization of Hybrid Rice Restorer Lines with Resilience to Suboptimal Temperatures during Filling Stage. Foods 2022, 11, 3513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, A.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, B.; Xue, P.; Cao, Y.; Chen, Y.; Li, Z.; Liu, Q.; Cheng, S.; et al. Genetic Dissection of qPCG1 for a Quantitative Trait Locus for Percentage of Chalky Grain in Rice (Oryza sativa L.). Front. Plant Sci. 2018, 9, 1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.; Dong, Y.; Zhou, M.; Wang, Y.; Liu, X.; Lu, X.; Zhang, G.; Wang, F.; Tang, W.; Deng, H. Regulation of Rice Grain Quality by Exogenous Kinetin During Grain-Filling Period. Plants 2025, 14, 358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Guo, M.; Sun, S.; Zou, Y.; Yin, S.; Liu, Y.; Tang, S.; Gu, M.; Yang, Z.; Yan, C. Natural Variation of OsGluA2 Is Involved in Grain Protein Content Regulation in Rice. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 1949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, F.-F.; Xue, H.-W. Coexpression Analysis Identifies Rice Starch Regulator1, a Rice AP2/EREBP Family Transcription Factor, as a Novel Rice Starch Biosynthesis Regulator. Plant Physiol. 2010, 154, 927–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bello, B.K.; Hou, Y.; Zhao, J.; Jiao, G.; Wu, Y.; Li, Z.; Wang, Y.; Tong, X.; Wang, W.; Yuan, W.; et al. NF-YB1-YC12-bHLH144 Complex Directly Activates Wx to Regulate Grain Quality in Rice (Oryza sativa L.). Plant Biotechnol. J. 2019, 17, 1222–1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; E, Z.; Zhang, D.; Yun, Q.; Zhou, Y.; Niu, B.; Chen, C. OsYUC11-Mediated Auxin Biosynthesis Is Essential for Endosperm Development of Rice. Plant Physiol. 2021, 185, 934–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, Q.; Meng, S.; Wei, C. The NAC Transcription Factors OsNAC20 and OsNAC26 Regulate Starch and Storage Protein Synthesis. Plant Physiol. 2020, 184, 1775–1791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhang, H.; Wang, Y.; Meng, S.; Liu, Q.; Li, Q.; Zhao, Z.; Liu, Q.; Wei, C. Regulatory Loops between Rice Transcription Factors OsNAC25 and OsNAC20/26 Balance Starch Synthesis. Plant Physiol. 2024, 195, 1365–1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, W.; Xu, P.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, S.; Li, Z.; Yang, K.; Chang, X.; Li, Y. OsbZIP60-Mediated Unfolded Protein Response Regulates Grain Chalkiness in Rice. J. Genet. Genom. 2022, 49, 414–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, X.; Zhong, W.; Wang, K.; Gong, X.; Xia, Y.; Nong, J.; Xiao, L.; Xia, S. Regulation of Grain Chalkiness and Starch Metabolism by FLO2 Interaction Factor 3, a bHLH Transcription Factor in Oryza sativa. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 12778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, S.; Prusty, A.; Dansana, P.K.; Kapoor, S.; Tyagi, A. Overexpression of the General Transcription Factor OsTFIIB5 Alters Rice Development and Seed Quality. Plant Cell Rep. 2025, 44, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.-Q.; Tian, X.-Y.; Li, J.; Bai, S.; Zhang, Z.-Y.; Li, Y.; Cao, H.-R.; Chen, Z.-C. Two Central Circadian Oscillators OsPRR59 and OsPRR95 Modulate Magnesium Homeostasis and Carbon Fixation in Rice. Mol. Plant 2022, 15, 1602–1614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, H.; Zhang, W.; Wu, Y.; Gao, L.; Cui, F.; Zhao, C.; Guo, Z.; Jia, J. The Circadian Clock Gene, TaPRR1, Is Associated with Yield-Related Traits in Wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Liu, H.; Zhang, H.; Xing, Y. Validation and Characterization of Ghd7.1, a Major Quantitative Trait Locus with Pleiotropic Effects on Spikelets per Panicle, Plant Height, and Heading Date in Rice (Oryza sativa L.). J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2013, 55, 917–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, W.; Liu, H.; Zhou, X.; Li, Q.; Zhang, J.; Lu, L.; Liu, T.; Liu, H.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, Z.; et al. Natural Variation in Ghd7.1 Plays an Important Role in Grain Yield and Adaptation in Rice. Cell Res. 2013, 23, 969–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, C.; Xing, Y.; Mao, H.; Lu, T.; Han, B.; Xu, C.; Li, X.; Zhang, Q. GS3, a Major QTL for Grain Length and Weight and Minor QTL for Grain Width and Thickness in Rice, Encodes a Putative Transmembrane Protein. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2006, 112, 1164–1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Wang, Y.; Qiao, W.; Zhu, Z.; Wang, Z.; Tian, Y.; Liu, S.; Wan, J.; Liu, L. Identification of a Novel Locus qGW12/OsPUB23 Regulating Grain Shape and Weight in Rice (Oryza sativa L.). Theor. Appl. Genet. 2024, 137, 267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, M.; Liu, J.; Hou, L.; Zhao, S.; Zhang, N.; Lu, L.; Zhao, X. The Mitochondria-Localized Protein OsNDB2 Negatively Regulates Grain Size and Weight in Rice. Crop J. 2022, 10, 1819–1824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Li, Z.; Ye, J.; Yang, Y.; Ye, J.; Xu, S.; Liu, J.; Yuan, X.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, M.; et al. Identification of SMG3, a QTL Coordinately Controls Grain Size, Grain Number per Panicle, and Grain Weight in Rice. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 880919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, L.; Li, J.; Liu, K.; Jiang, C.; Jin, W.; Ye, J.; Qin, T.; Luo, B.; Chen, Z.; Li, J.; et al. DGW1, Encoding an hnRNP-like RNA Binding Protein, Positively Regulates Grain Size and Weight by Interacting with GW6 mRNA. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2024, 22, 512–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, P.; Chen, F.; Liu, H.; Fan, S.; Zeng, J.; Diao, X.; Liu, Y.; Song, W.; Wang, S.; Li, J.; et al. qGW11a/OsCAT8, Encoding an Amino Acid Permease, Negatively Regulates Grain Size and Weight in Rice. Crop J. 2024, 12, 1150–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, X.; Jiao, G.; Lin, H.; Sheng, Z.; Shao, G.; Xie, L.; Tang, S.; Xu, Q.; Hu, P. GRAIN INCOMPLETE FILLING 2 Regulates Grain Filling and Starch Synthesis during Rice Caryopsis Development. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2017, 59, 134–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, X.; Li, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Wang, J.; Zhao, J.; Sun, X.; Pan, Y.; Bian, X.; Zhang, C.; Zhao, D.; et al. Characterization of Physicochemical Qualities and Starch Structures of Two Indica Rice Varieties Tolerant to High Temperature during Grain Filling. J. Cereal Sci. 2020, 93, 102966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.; Tu, B.; Yang, W.; Yuan, H.; Li, J.; Guo, L.; Zheng, L.; Chen, W.; Zhu, X.; Wang, Y.; et al. Mitochondria-Associated Pyruvate Kinase Complexes Regulate Grain Filling in Rice. Plant Physiol. 2020, 183, 1073–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Meng, S.; Yang, J.; Wu, J.; Peng, Y.; Zhang, J.; Ye, N. Carbohydrate Flow during Grain Filling: Phytohormonal Regulation and Genetic Control in Rice (Oryza sativa). J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2025, 67, 1086–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Zhao, Y.; Chen, L.; Wan, X.; Yan, B.; Liu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, W.; Gao, J. Grain Weight and Taste Quality in Japonica Rice Are Regulated by Starch Synthesis and Grain Filling Under Nitrogen–Phosphorus Interactions. Plants 2025, 14, 432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, P.; Wang, J.; Zhang, T.; Huang, J.; Peng, S. High Nitrogen Input Causes Poor Grain Filling of Spikelets at the Panicle Base of Super Hybrid Rice. Field Crops Res. 2019, 244, 107635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Q.; Mayes, S.; Sparkes, D.L. Carpel Size, Grain Filling, and Morphology Determine Individual Grain Weight in Wheat. J. Exp. Bot. 2015, 66, 6715–6730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Zhou, T.; Xue, Z.; Wei, C.; Zhu, K.; Ye, M.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, H.; Liu, L.; Wang, Z.; et al. Combining Controlled-Release and Normal Urea Enhances Rice Grain Quality and Starch Properties by Improving Carbohydrate Supply and Grain Filling. Plants 2025, 14, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, Z.; Zheng, Q.; Liu, B.; Meng, S.; Zhang, J.; Ye, N. Moderate Soil Drying-Induced Alternative Splicing Provides a Potential Novel Approach for the Regulation of Grain Filling in Rice Inferior Spikelets. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 7770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Pan, J.; Cui, K.; Yuan, M.; Hu, Q.; Wang, W.; Mohapatra, P.K.; Nie, L.; Huang, J.; Peng, S. Limitation of Unloading in the Developing Grains Is a Possible Cause Responsible for Low Stem Non-Structural Carbohydrate Translocation and Poor Grain Yield Formation in Rice through Verification of Recombinant Inbred Lines. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 1369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.-K.; Hwang, S.-K.; Han, M.; Eom, J.-S.; Kang, H.-G.; Han, Y.; Choi, S.-B.; Cho, M.-H.; Bhoo, S.H.; An, G.; et al. Identification of the ADP-Glucose Pyrophosphorylase Isoforms Essential for Starch Synthesis in the Leaf and Seed Endosperm of Rice (Oryza sativa L.). Plant Mol. Biol. 2007, 65, 531–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prathap, V.; Tyagi, A. Correlation between Expression and Activity of ADP Glucose Pyrophosphorylase and Starch Synthase and Their Role in Starch Accumulation during Grain Filling under Drought Stress in Rice. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2020, 157, 239–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szydlowski, N.; Ragel, P.; Hennen-Bierwagen, T.A.; Planchot, V.; Myers, A.M.; Mérida, A.; d’Hulst, C.; Wattebled, F. Integrated Functions among Multiple Starch Synthases Determine Both Amylopectin Chain Length and Branch Linkage Location in Arabidopsis Leaf Starch. J. Exp. Bot. 2011, 62, 4547–4559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Ding, J.; Feng, X.; Zhong, X.; Lan, J.; Tang, H.; Harwood, W.; Li, Z.; Guzmán, C.; Xu, Q.; et al. Editing of the Starch Synthase IIa Gene Led to Transcriptomic and Metabolomic Changes and High Amylose Starch in Barley. Carbohydr. Polym. 2022, 285, 119238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, H.; Xie, S.; Xiao, Q.; Wei, B.; Zheng, L.; Wang, Y.; Cao, Y.; Zhang, X.; Long, T.; Li, Y.; et al. Sucrose and ABA Regulate Starch Biosynthesis in Maize through a Novel Transcription Factor, ZmEREB156. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 27590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rook, F.; Corke, F.; Card, R.; Munz, G.A.; Smith, C.; Bevan, M. Impaired Sucrose-Induction Mutants Reveal the Modulation of Sugar-Induced Starch Biosynthetic Gene Expression by Abscisic Acid Signalling. Plant J. Cell Mol. Biol. 2001, 26, 421–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Botticella, E.; Sestili, F.; Sparla, F.; Moscatello, S.; Marri, L.; Cuesta-Seijo, J.A.; Falini, G.; Battistelli, A.; Trost, P.; Lafiandra, D. Combining Mutations at Genes Encoding Key Enzymes Involved in Starch Synthesis Affects the Amylose Content, Carbohydrate Allocation and Hardness in the Wheat Grain. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2018, 16, 1723–1734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.-Z.; Fang, J.-H.; Yan, X.; Liu, J.; Bao, J.-S.; Fransson, G.; Andersson, R.; Jansson, C.; Åman, P.; Sun, C. Molecular Insights into How a Deficiency of Amylose Affects Carbon Allocation—Carbohydrate and Oil Analyses and Gene Expression Profiling in the Seeds of a Rice Waxy Mutant. BMC Plant Biol. 2012, 12, 230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, J.; Ying, Y.; Zhou, X.; Xu, Y.; Wu, P.; Xu, F.; Pang, Y. Relationships among Starch Biosynthesizing Protein Content, Fine Structure and Functionality in Rice. Carbohydr. Polym. 2020, 237, 116118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Yuan, F.; Fu, X.; Zhu, D. Profiling and Relationship of Water-Soluble Sugar and Protein Compositions in Soybean Seeds. Food Chem. 2016, 196, 776–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, C.; Zhang, L.; Jiang, P.; Yang, Z.; Chen, Z.; Xu, F.; Guo, X.; Sun, Y.; Ma, J. Grain Chalkiness Is Decreased by Balancing the Synthesis of Protein and Starch in Hybrid Indica Rice Grains under Nitrogen Fertilization. Foods 2024, 13, 855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fei, L.; Yang, S.; Ma, A.; Lunzhu, C.; Wang, M.; Wang, G.; Guo, S. Grain Chalkiness Is Reduced by Coordinating the Biosynthesis of Protein and Starch in Fragrant Rice (Oryza sativa L.) Grain under Nitrogen Fertilization. Field Crops Res. 2023, 302, 109098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, C.; Yuan, X.; Yan, F.; Xiang, K.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, Z.; He, L.; Fan, P.; Yang, Z.; et al. Nitrogen Application Rate Affects the Accumulation of Carbohydrates in Functional Leaves and Grains to Improve Grain Filling and Reduce the Occurrence of Chalkiness. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 921130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Li, P.; Du, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Cai, M.; Cao, C. Dry Cultivation and Cultivar Affect Starch Synthesis and Traits to Define Rice Grain Quality in Various Panicle Parts. Carbohydr. Polym. 2021, 269, 118336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Gutierrez, A.; Tan, L.; Kong, L. Inhibitory Effect of Ascorbic Acid on in Vitro Enzymatic Digestion of Raw and Cooked Starches. Front. Nutr. 2021, 8, 758367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jekle, M.; Mühlberger, K.; Becker, T. Starch–Gluten Interactions during Gelatinization and Its Functionality in Dough like Model Systems. Food Hydrocoll. 2016, 54, 196–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhital, S.; Butardo, V.M.; Jobling, S.A.; Gidley, M.J. Rice Starch Granule Amylolysis—Differentiating Effects of Particle Size, Morphology, Thermal Properties and Crystalline Polymorph. Carbohydr. Polym. 2015, 115, 305–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, C.; Gong, X.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, C.; Qian, J.-Y.; Zhu, W. Effect of Rice Protein on the Gelatinization and Retrogradation Properties of Rice Starch. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 242, 125061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, F.; Shen, Q. The Impact of Endogenous Proteins on Hydration, Pasting, Thermal and Rheology Attributes of Foxtail Millet. J. Cereal Sci. 2021, 100, 103255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, M.; Wu, H.; Clay, K.L.; Jung, R.; Larkins, B.; Gibbon, B.C. Identification and Characterization of Lysine-Rich Proteins and Starch Biosynthesis Genes in the Opaque2 Mutant by Transcriptional and Proteomic Analysis. BMC Plant Biol. 2013, 13, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sethi, M.; Singh, A.; Kaur, H.; Phagna, R.K.; Rakshit, S.; Chaudhary, D. Expression Profile of Protein Fractions in the Developing Kernel of Normal, Opaque-2 and Quality Protein Maize. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 2469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Rosa Zavareze, E.; Dias, A.R.G. Impact of Heat-Moisture Treatment and Annealing in Starches: A Review. Carbohydr. Polym. 2011, 83, 317–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, N.; Singh, J.; Kaur, L.; Singh Sodhi, N.; Singh Gill, B. Morphological, Thermal and Rheological Properties of Starches from Different Botanical Sources. Food Chem. 2003, 81, 219–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Costa Urtiga, S.C.; Alves, V.M.O.; de Oliveira Melo, C.; de Lima, M.N.; Souza, E.; Cunha, A.P.; Ricardo, N.M.P.S.; Oliveira, E.E.; do Egito, E.S.T. Xylan Microparticles for Controlled Release of Mesalamine: Production and Physicochemical Characterization. Carbohydr. Polym. 2020, 250, 116929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, M.; Cheng, Y.; Wang, F.; Ji, X.; Liu, Y.; Yan, Y. Rheological Properties of Wheat Flour Modified by Plasma-Activated Water and Heat Moisture Treatment and in Vitro Digestibility of Steamed Bread. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 850227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Li, Y.; Jin, Z.; Cheng, Y. Physicochemical, Morphological, and Functional Properties of Starches Isolated from Avocado Seeds, a Potential Source for Resistant Starch. Biomolecules 2022, 12, 1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newberry, M.; Zwart, A.B.; Whan, A.; Mieog, J.C.; Sun, M.; Leyne, E.; Pritchard, J.; Daneri-Castro, S.N.; Ibrahim, K.; Diepeveen, D.; et al. Does Late Maturity Alpha-Amylase Impact Wheat Baking Quality? Front. Plant Sci. 2018, 9, 1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Limpongsa, E.; Jaipakdee, N. Physical Modification of Thai Rice Starch and Its Application as Orodispersible Film Former. Carbohydr. Polym. 2020, 239, 116206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamza, Z.; El-Hashash, M.; Aly, S.; Hathout, A.; Soto, E.; Sabry, B.; Ostroff, G. Preparation and Characterization of Yeast Cell Wall Beta-Glucan Encapsulated Humic Acid Nanoparticles as an Enhanced Aflatoxin B1 Binder. Carbohydr. Polym. 2019, 203, 185–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zong, W.; Ren, D.; Huang, M.; Sun, K.; Feng, J.; Zhao, J.; Xiao, D.; Xie, W.; Liu, S.; Zhang, H.; et al. Strong Photoperiod Sensitivity Is Controlled by Cooperation and Competition among Hd1, Ghd7 and DTH8 in Rice Heading. New Phytol. 2021, 229, 1635–1649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, F.J. A Flexible Growth Function for Empirical Use. J. Exp. Bot. 1959, 10, 290–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Ma, M.; Lu, H.; Meng, Q.; Li, G.; Yang, X. Photosynthesis, Sucrose Metabolism, and Starch Accumulation in Two NILs of Winter Wheat. Photosynth. Res. 2015, 126, 363–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yemm, E.W.; Willis, A.J. The Estimation of Carbohydrates in Plant Extracts by Anthrone. Biochem. J. 1954, 57, 508–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juliano, B.O.; Perez, C.M.; Blakeney, A.B.; Castillo, T.; Kongseree, N.; Laignelet, B.; Lapis, E.T.; Murty, V.V.S.; Paule, C.M.; Webb, B.D. International Cooperative Testing on the Amylose Content of Milled Rice. Starch-Stärke 1981, 33, 157–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cagampang, G.B.; Perez, C.M.; Juliano, B.O. A Gel Consistency Test for Eating Quality of Rice. J. Sci. Food Agric. 1973, 24, 1589–1594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kong, X.; Zhu, P.; Sui, Z.; Bao, J. Physicochemical Properties of Starches from Diverse Rice Cultivars Varying in Apparent Amylose Content and Gelatinisation Temperature Combinations. Food Chem. 2015, 172, 433–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, L.; Wang, Q.; Chen, H.; Wu, D.; Dai, C.; Chen, Y.; Ma, Y.; Wang, Z.; Li, H.; Cao, X.; et al. Moderate Addition of B-Type Starch Granules Improves the Rheological Properties of Wheat Dough. Food Res. Int. 2022, 160, 111748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Li, D.; Ma, Q.; Wu, E.; Gao, L.; Yang, P.; Gao, J.; Feng, B. Nitrogen Fertilizer Affects Starch Synthesis to Define Non-Waxy and Waxy Proso Millet Quality. Carbohydr. Polym. 2023, 302, 120423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Genotype | Tmax·G (Day) | Gmax (g·1000 Grains−1·Day) | D (Day) | (g·1000 Grains−1·Day) | A (g·1000 Grain−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WT | 6.507 ± 0.204 | 2.483 ± 0.111 * | 13.303 ± 0.426 | 1.498 ± 0.058 * | 22.834 ± 0.909 * |

| osprr37 | 6.456 ± 0.238 | 2.069 ± 0.119 | 14.324 ± 1.43 | 1.244 ± 0.072 | 19.742 ± 0.933 |

| Genotype | Mean Diameter (μm) | Distribution of Volume-Weighted Mean Diameter (%) | Surface Area-Weighted Mean Diameter D [3,2] (μm) | Volume-Weighted Mean Diameter D [4,3] (μm) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ≤2 μm | 2–5 μm | ≥5 μm | ||||

| WT | 4.87 ± 0.03 * | 6.13 ± 0.41 | 38.02 ± 0.30 | 55.85 ± 0.71 * | 4.12 ± 0.05 | 5.05 ± 0.02 * |

| osprr37 | 4.73 ± 0.01 | 6.40 ± 0.47 | 41.02 ± 0.30 ** | 52.58 ± 0.17 | 4.02 ± 0.04 | 4.95 ± 0.02 |

| Genotype | To (°C) | Tp (°C) | Tc (°C) | ΔH (J·g−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| WT | 58.46 ± 0.36 | 67.62 ± 0.26 * | 75.66 ± 0.28 | 12.42 ± 0.21 * |

| osprr37 | 57.65 ± 0.37 | 65.18 ± 1.37 | 73.82 ± 1.59 | 10.82 ± 0.82 |

| Genotype | Peak Viscosity PV (cP) | Trough Viscosity TV (cP) | Breakdown BD (cP) | Final Viscosity FV (cP) | Setback SB (cP) | Pasting Temperature PT (°C) | Peak Time PeT (min) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WT | 1587.5 ± 24.7 ** | 947 ± 15.6 ** | 640.5 ± 9.2 ** | 1750.5 ± 27.6 ** | 803.5 ± 12 ** | 76.6 ± 0.1 | 6.17 ± 0.05 * |

| osprr37 | 1142 ± 7.1 | 701 ± 12.7 | 441 ± 19.8 | 1379.5 ± 17.7 | 678.5 ± 4.9 | 92.9 ± 0.1 ** | 6.03 ± 0.05 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, H.; Tang, S.; Wei, F.; Zong, W.; Hou, J.; Ran, X.; Zhao, J.; Guo, J.; Wang, Z. The Effects of Photoperiodic Transcription Factor OsPRR37 on Grain Filling and Starch Synthesis During Rice Caryopsis Development. Plants 2025, 14, 3690. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14233690

Zhang H, Tang S, Wei F, Zong W, Hou J, Ran X, Zhao J, Guo J, Wang Z. The Effects of Photoperiodic Transcription Factor OsPRR37 on Grain Filling and Starch Synthesis During Rice Caryopsis Development. Plants. 2025; 14(23):3690. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14233690

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Hanbing, Siqi Tang, Funan Wei, Wubei Zong, Junbin Hou, Xu Ran, Jingjing Zhao, Jingxin Guo, and Zhonghua Wang. 2025. "The Effects of Photoperiodic Transcription Factor OsPRR37 on Grain Filling and Starch Synthesis During Rice Caryopsis Development" Plants 14, no. 23: 3690. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14233690

APA StyleZhang, H., Tang, S., Wei, F., Zong, W., Hou, J., Ran, X., Zhao, J., Guo, J., & Wang, Z. (2025). The Effects of Photoperiodic Transcription Factor OsPRR37 on Grain Filling and Starch Synthesis During Rice Caryopsis Development. Plants, 14(23), 3690. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14233690