An Integrated Meta-QTL and Transcriptome Analysis Provides Candidate Genes Associated with Drought Tolerance in Rice Seedlings

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

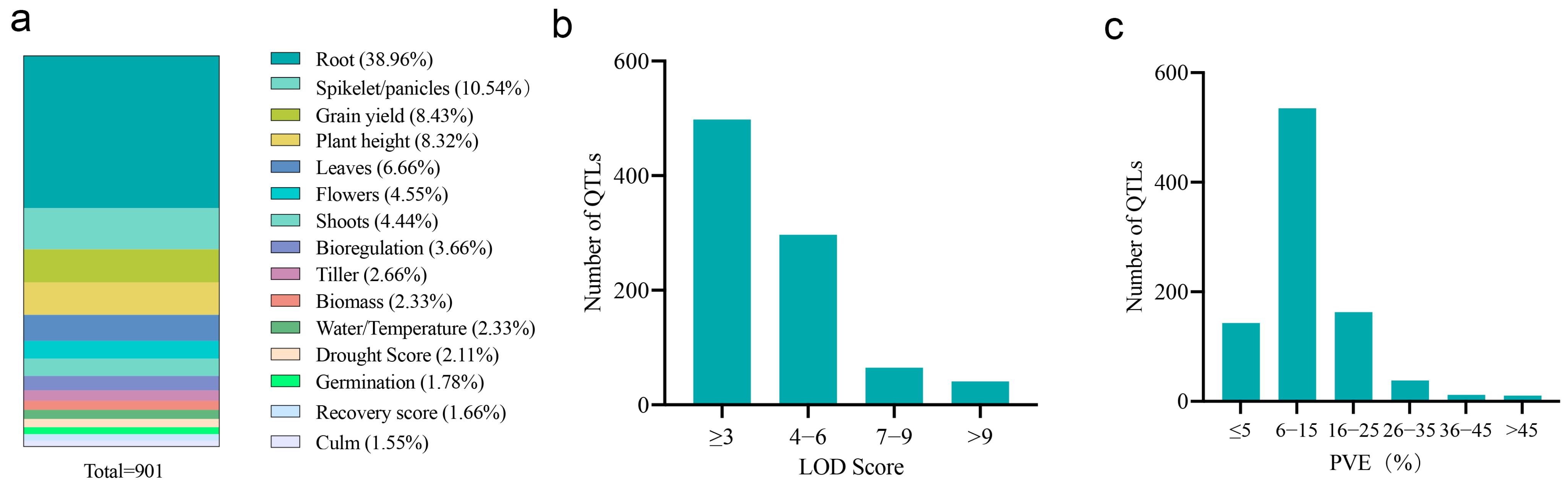

2.1. Collection of QTL Data Associated with Drought Tolerance in Rice from Previous Studies

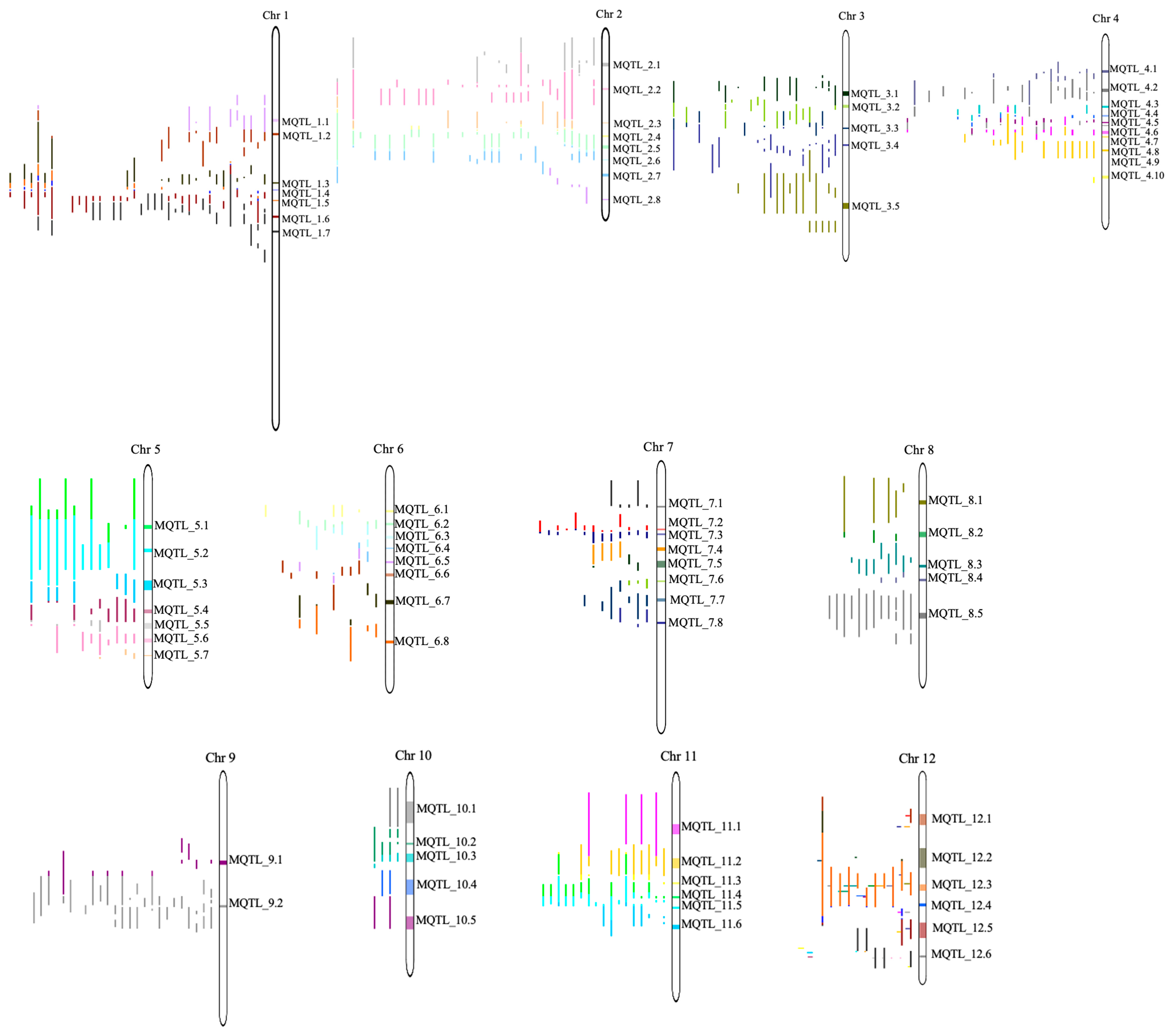

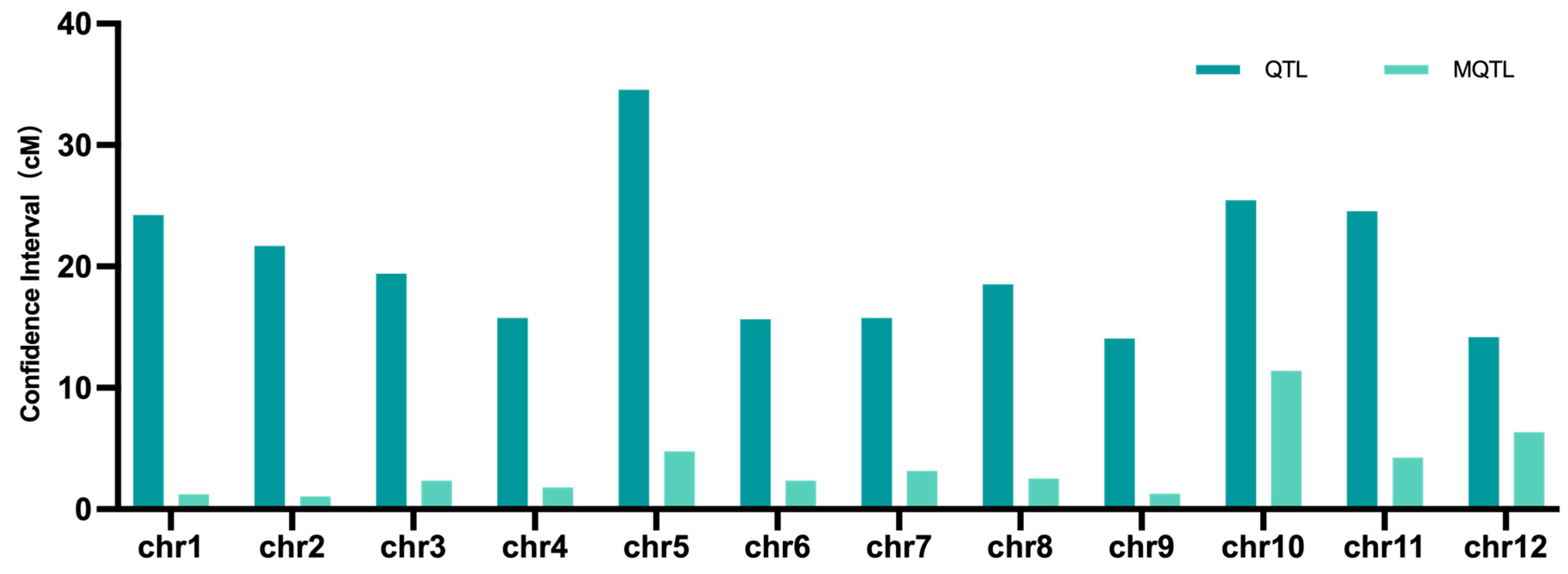

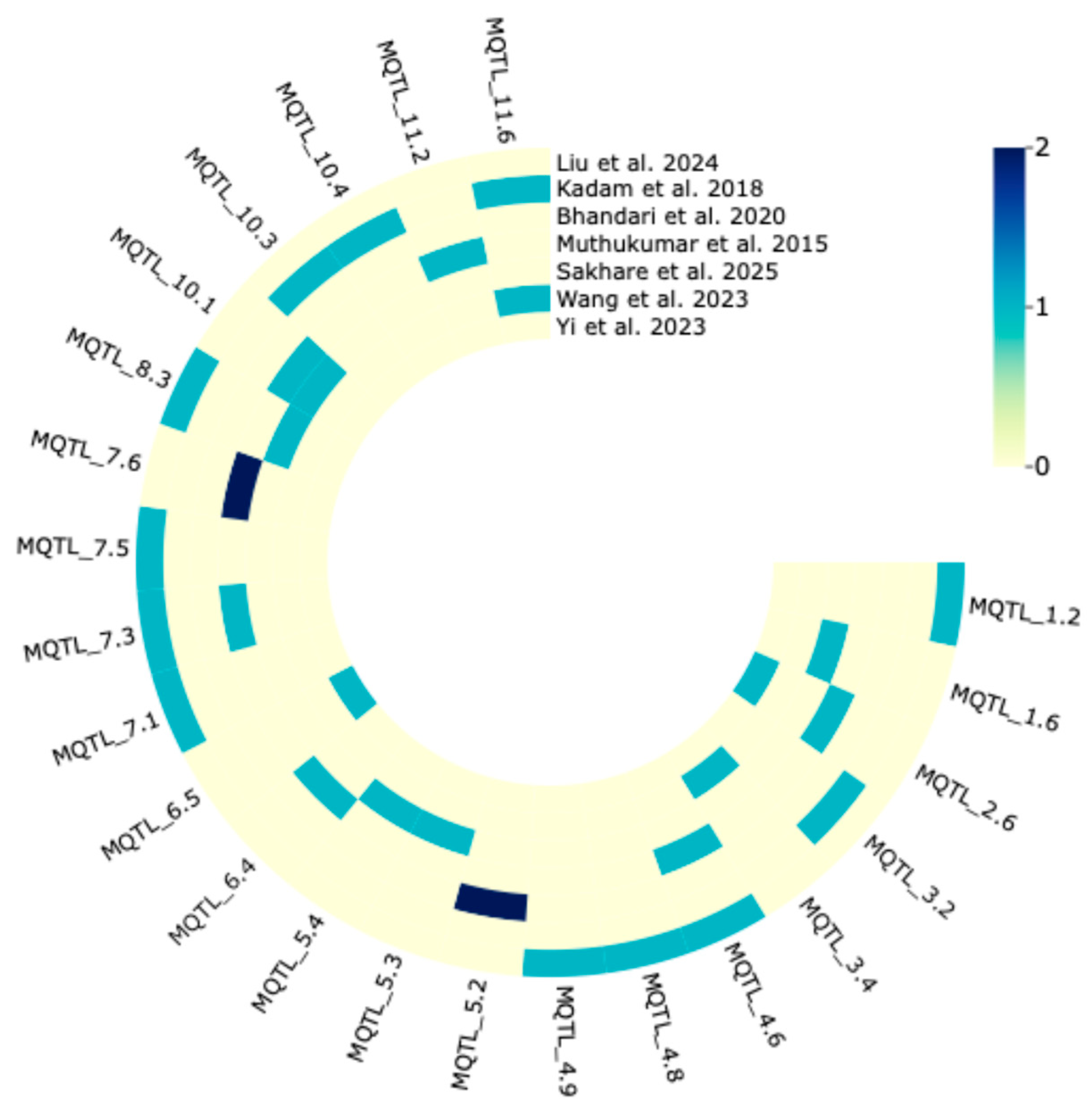

2.2. Meta-Analysis of QTLs Conferring Drought Tolerance in Rice

2.3. Validation of MQTL by GWAS-Based Marker–Trait Associations (MTAs)

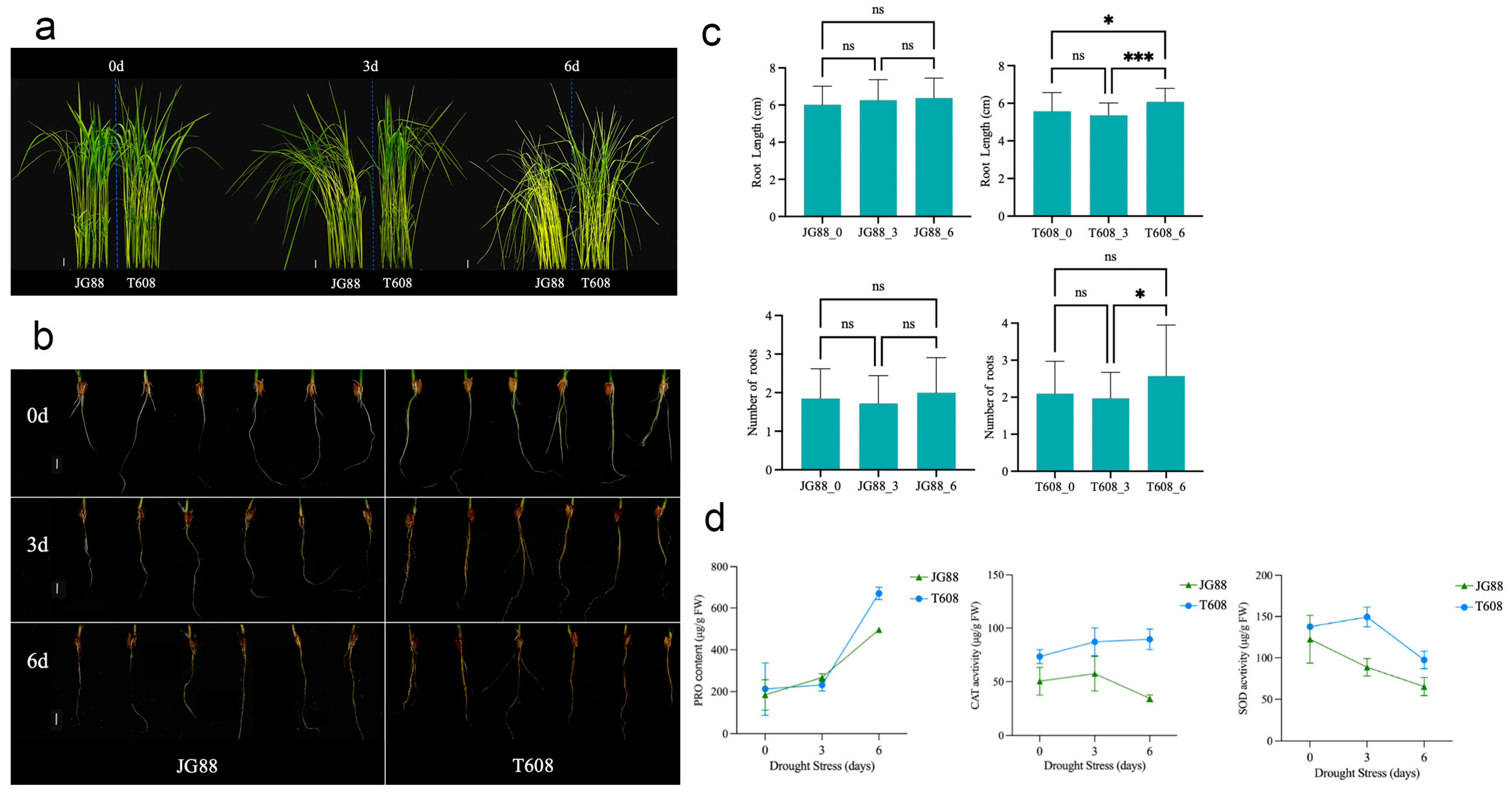

2.4. Comparative Analysis of Drought Tolerance, Root Architecture, and Physiological Responses Between Wild-Type and T608 Mutant Rice

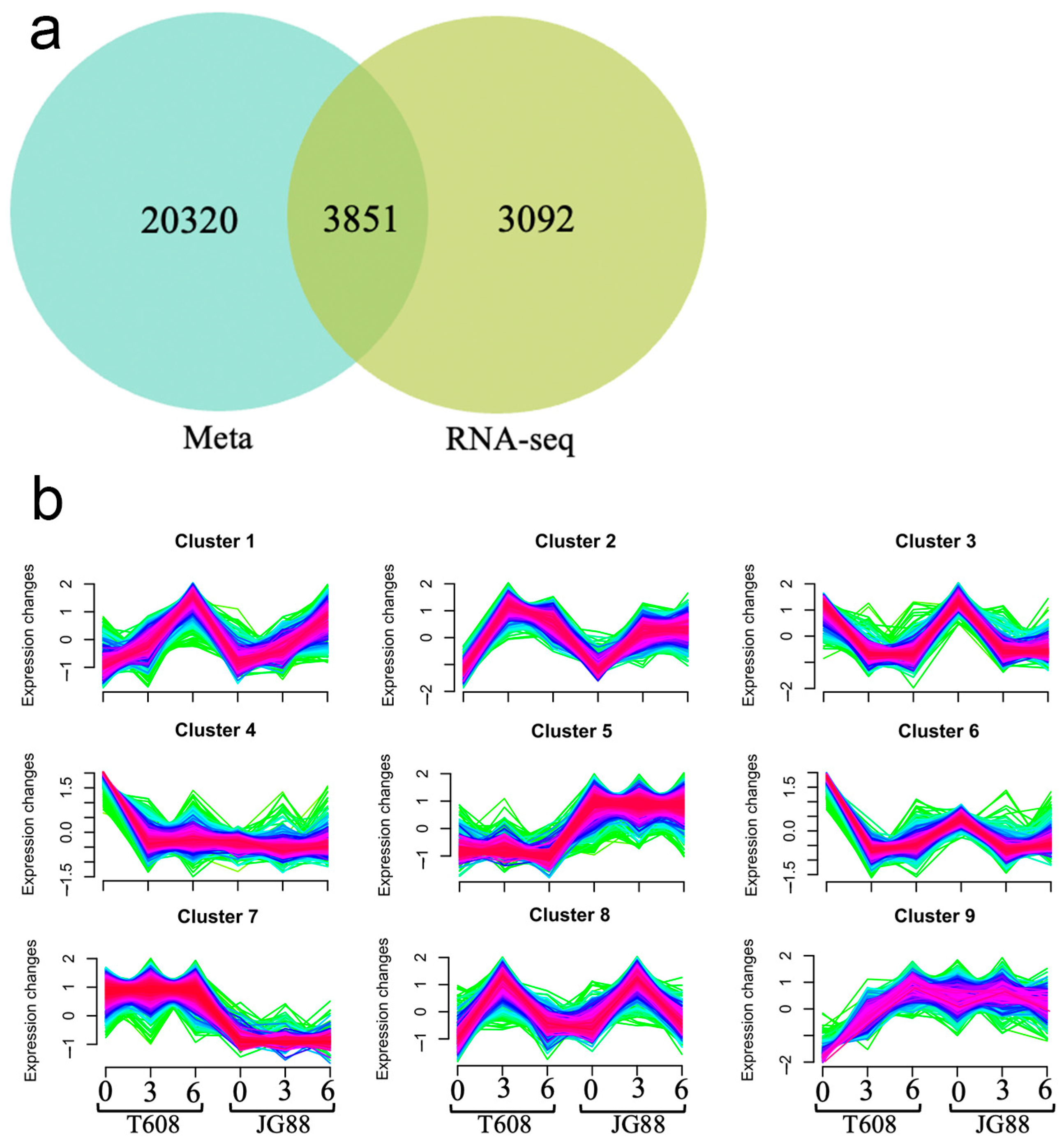

2.5. RNA-Seq, Functional Enrichment (GO and KEGG) of DEGs and qRT-PCR Validation

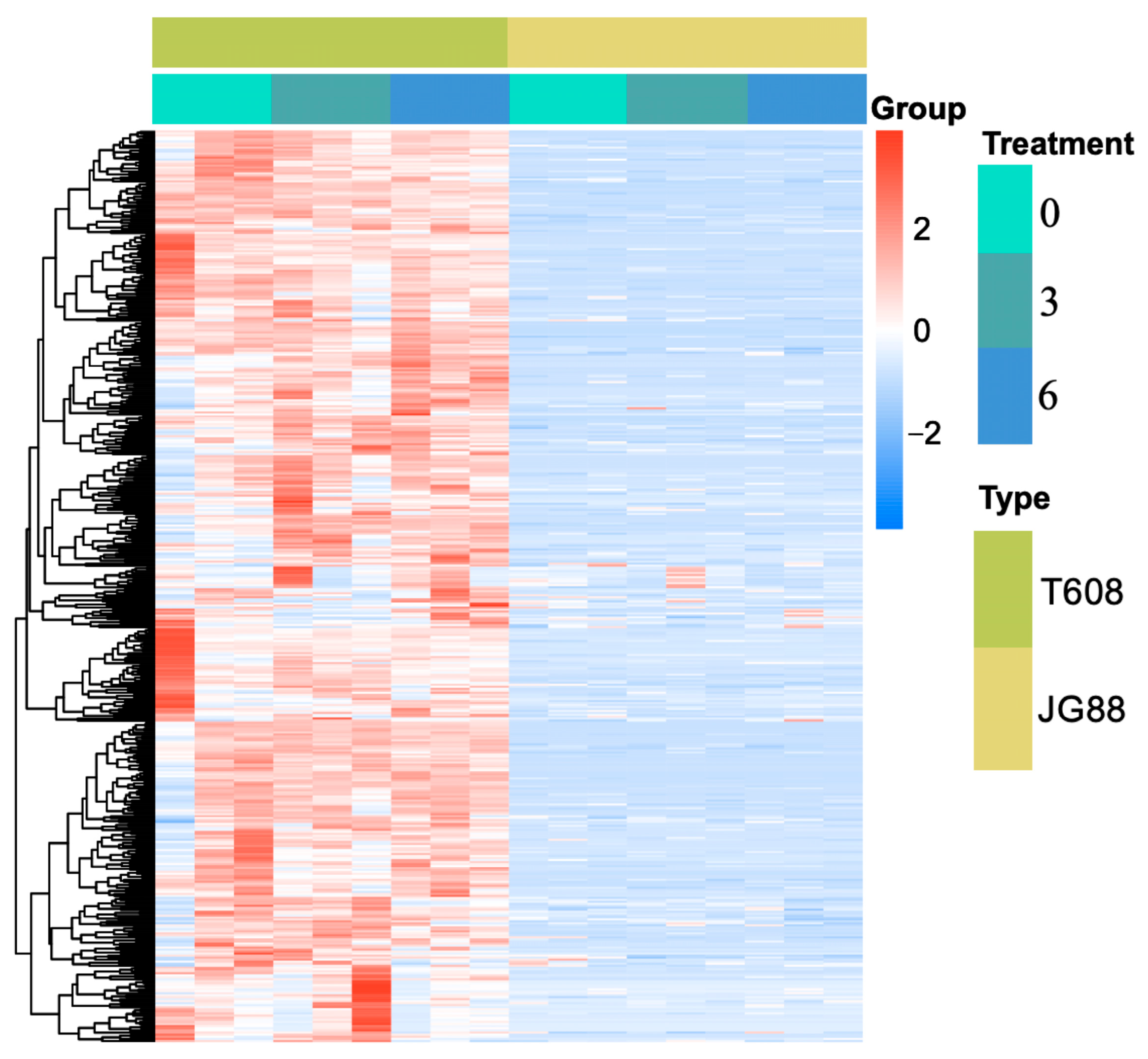

2.6. Integrative RNA-Seq, MQTL, and Clustering Analyses Reveal Mutant-Specific Expression Modules

2.7. Screening of Drought-Responsive Differentially Expressed Candidate Genes (DECGs) in Rice Based on Cis-Acting Regulatory Elements (CREs)

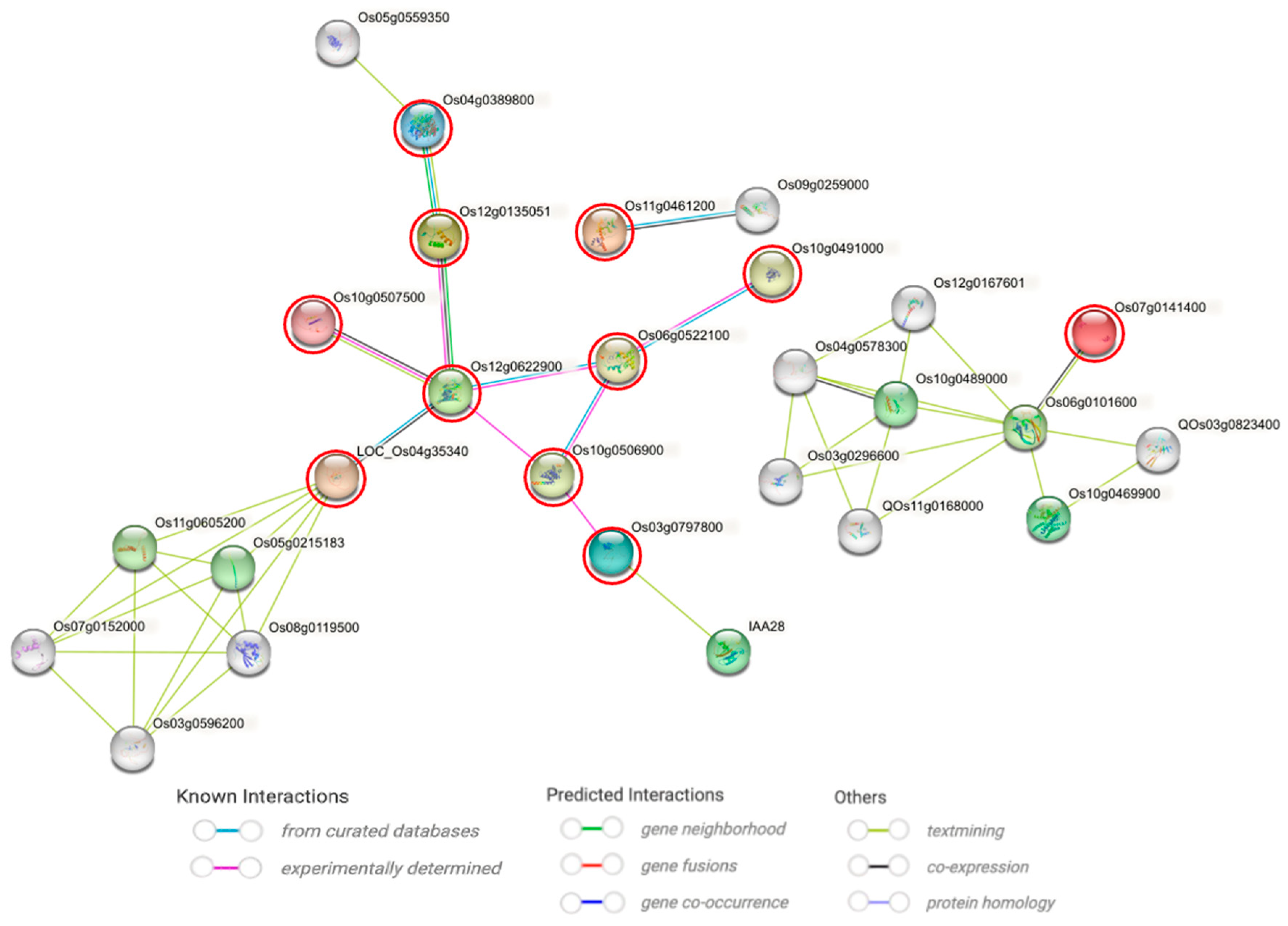

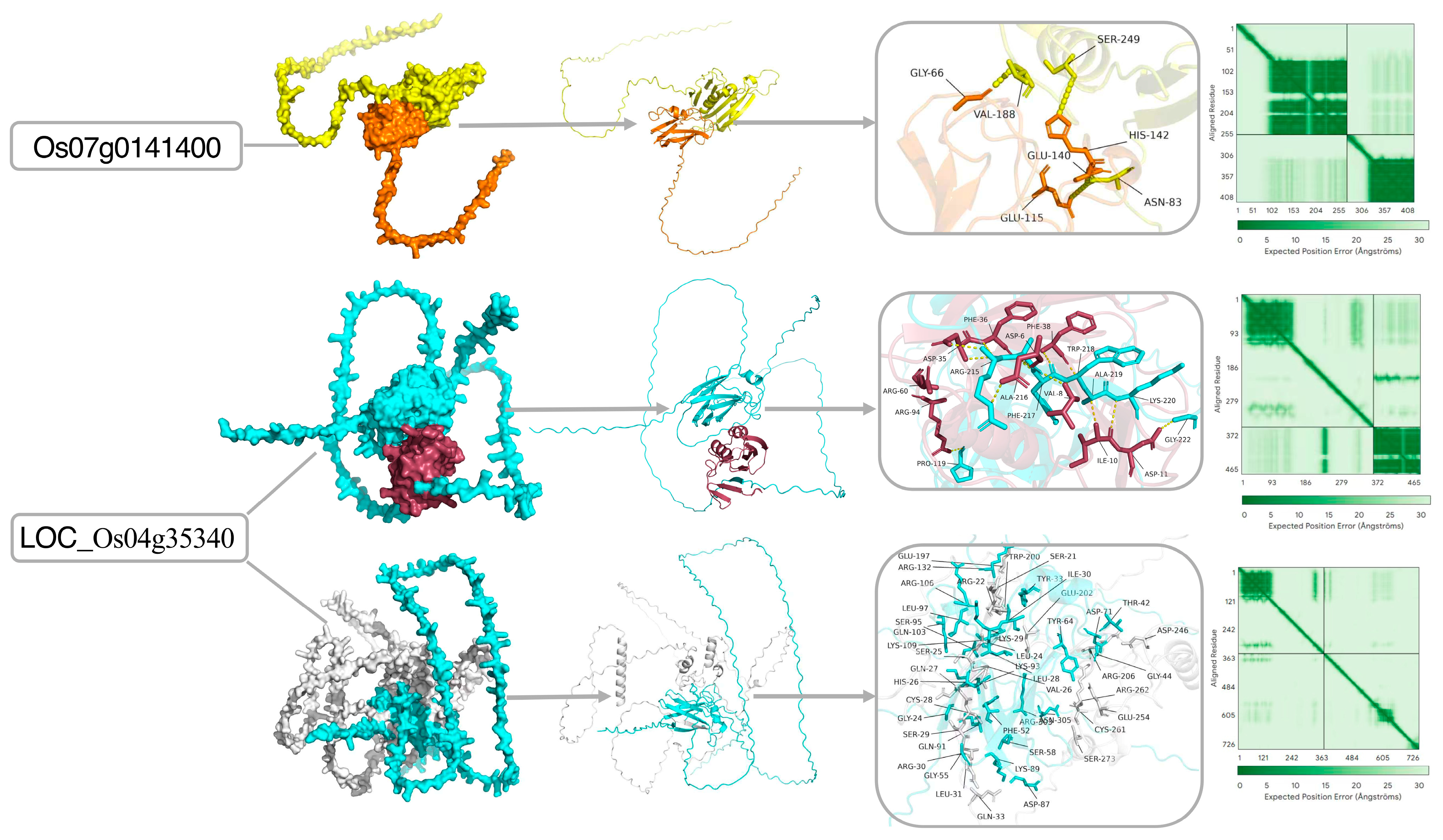

2.8. Hub Proteins for Drought Tolerance Identified via PPI Network and AlphaFold Structure Analyses

3. Discussion

3.1. Identification of QTLs Associated with Drought Tolerance and Construction of MQTLs in Rice

3.2. The Drought-Tolerant Mutant t608 Exhibits Enhanced Root Architecture and Antioxidant Capacity

3.3. Expression Signatures and Physiological Traits Jointly Suggest Potential Metabolic Adjustments in T608 Under Drought Stress

3.4. Integrated Analyses Identify Drought-Hub Genes with Putative Roles in Drought Response

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Data Collection and Screening of Drought-Related QTLs

4.2. Integration of Rice Reference Genetic Maps and Construction of a Consensus Map for the Localization of Drought-Tolerance-Related QTLs

4.3. Meta-QTL Analysis

4.4. Comparative Analysis of MQTLs with Results from Drought Tolerance-Associated Genome-Wide Association Studies (GWAS)

4.5. Plant Materials and Drought Treatments

4.6. RNA Sequencing

4.7. Quantitative Real-Time Polymerase Chain Reaction (qRT-PCR) Validation

4.8. Screening of Differentially Expressed Candidate Genes (DECGs) Based on Cis-Acting Element Analysis

4.9. Systematic Screening of Hub Proteins via PPI Network Construction and Visualization of AlphaFold-Predicted Tertiary Structures

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| QTL | Quantitative Trait Loci |

| MQTL | Meta-QTL |

| GWAS | Genome-Wide Association Studies |

| CI | Confidence Interval |

| DEGs | Differentially Expressed Genes |

| CREs | Cis-acting Regulatory Elements |

| PPI | Protein–Protein Interaction |

| RNA-seq | RNA Sequencing |

| PVE | Phenotypic Variance Explained |

| LOD | Logarithm Of the Odds |

| BC | Backcross Population |

| DH | Doubled Haploid Lines |

| RIL | Recombinant Lnbred Lines |

| F2 | Second Filial Generation Population |

| SSR | Single Sequence Repeats |

| RFLP | Restriction Fragment Length Polymorphism |

| AFLP | Amplified Fragment Length Polymorphism |

| SNP | Single-Nucleotide Polymorphism |

| STS | Sequence-Tagged Site |

| AIC | Akaike Information Content |

| AICc | Akaike Information Content Correction |

| AIC3 | Akaike Information Content 3 Candidate Models |

| BIC | Bayesian Information Criterion |

| AWE | Average Weight of Evidence |

| chr | Chromosomes |

| WT | Wild-Type |

| JG88 | Jigeng 88 |

| PEG 6000 | Polyethylene Glycol 6000 |

| PRO | Proline |

| CAT | Catalase |

| SOD | Superoxide |

| qRT-PCR | Quantitative Real-Time Polymerase Chain Reaction |

| ROS | Reactive Oxygen Species |

| GO | Gene Ontology |

| DRE | Drought-Responsive Element |

| ARE | Anaerobic-Responsive Element |

| DECGs | Differentially Expressed Candidate Genes |

| CGs | Candidate Genes |

| FC | Fold Change |

Appendix A

| MQTL | Chr | CI (95%) | No. of QTL | Mean CI (95%) of Initial QTL | Position | Left Marker | Right Marker |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MQTL_1.1 | 1 | 2.22 | 11 | 30.81 | 125.5 | RM8146 | RM7466 |

| MQTL_1.2 | 1 | 0.69 | 12 | 21.43 | 150.53 | RM8103 | RM3627 |

| MQTL_1.3 | 1 | 1.67 | 35 | 25.95 | 208.15 | RM1349 | RM246 |

| MQTL_1.4 | 1 | 0.13 | 10 | 17.57 | 222.02 | RM7650 | RM3632 |

| MQTL_1.5 | 1 | 3.06 | 2 | 4.12 | 228.15 | RM232 | RZ730 |

| MQTL_1.6 | 1 | 0.1 | 34 | 23.38 | 232.87 | RM3440 | RM212 |

| MQTL_1.7 | 1 | 0.64 | 36 | 25.24 | 264.88 | RM3602 | RM6292 |

| MQTL_2.1 | 2 | 0.41 | 24 | 15.08 | 56.26 | RM6069 | RM12729 |

| MQTL_2.2 | 2 | 1.91 | 31 | 31.34 | 74.48 | RM3549 | RM3178 |

| MQTL_2.3 | 2 | 3.18 | 9 | 22.22 | 125.08 | RM3355 | RM6617 |

| MQTL_2.4 | 2 | 1.41 | 2 | 0.90 | 136.65 | RM599 | RM221 |

| MQTL_2.5 | 2 | 0.1 | 38 | 25.35 | 148.04 | RM6535 | RM6424 |

| MQTL_2.6 | 2 | 0.3 | 1 | 0.31 | 151.69 | RM3857 | RM573 |

| MQTL_2.7 | 2 | 0.4 | 16 | 10.93 | 173.95 | RM250 | RM2265 |

| MQTL_2.8 | 2 | 0.76 | 6 | 13.30 | 216.35 | RM498 | d29 |

| MQTL_3.1 | 3 | 0.56 | 38 | 16.23 | 66.93 | RM489 | RG409 |

| MQTL_3.2 | 3 | 4.7 | 12 | 20.07 | 85.85 | RM3545 | RM545 |

| MQTL_3.3 | 3 | 2.42 | 7 | 18.10 | 115.44 | RM5477 | RM3872 |

| MQTL_3.4 | 3 | 2.46 | 31 | 17.97 | 131.65 | RM338 | RM130 |

| MQTL_3.5 | 3 | 1.69 | 19 | 28.14 | 212.75 | RM6876 | RM570 |

| MQTL_4.1 | 4 | 0.27 | 23 | 15.33 | 38.95 | RM6156 | RM417 |

| MQTL_4.2 | 4 | 0.39 | 17 | 17.10 | 62.46 | RM5424 | RM471 |

| MQTL_4.3 | 4 | 0.31 | 2 | 8.04 | 76.93 | RM119 | RM3337 |

| MQTL_4.4 | 4 | 0.43 | 7 | 14.71 | 90.13 | RM1869 | RM3866 |

| MQTL_4.5 | 4 | 3.4 | 2 | 5.02 | 94.49 | RM3839 | RM1223 |

| MQTL_4.6 | 4 | 1.56 | 5 | 6.96 | 100.89 | RM3288 | RM131 |

| MQTL_4.7 | 4 | 0.06 | 8 | 14.39 | 105.15 | RM2636 | RM3276 |

| MQTL_4.8 | 4 | 4.01 | 10 | 15.34 | 113.84 | RM1153 | RM303 |

| MQTL_4.9 | 4 | 3.28 | 24 | 19.81 | 128.43 | RM470 | RM3648 |

| MQTL_4.10 | 4 | 4.16 | 1 | 8.00 | 171.44 | RM6246 | RM280 |

| MQTL_5.1 | 5 | 4.56 | 2 | 12.25 | 47.04 | RM122 | RM4777 |

| MQTL_5.2 | 5 | 1.59 | 17 | 60.57 | 73.84 | RM6229 | RM507 |

| MQTL_5.3 | 5 | 10.78 | 4 | 24.27 | 103.24 | RM6082 | RM163 |

| MQTL_5.4 | 5 | 4.94 | 7 | 19.26 | 128.08 | RM3351 | RM440 |

| MQTL_5.5 | 5 | 5.99 | 4 | 22.01 | 141.65 | RM459 | RM305 |

| MQTL_5.6 | 5 | 4.27 | 11 | 21.60 | 156.66 | RM173 | RM6360 |

| MQTL_5.7 | 5 | 1.3 | 3 | 15.78 | 172.99 | RM6400 | RM3790 |

| MQTL_6.1 | 6 | 0.3 | 8 | 10.50 | 49.7 | RM6775 | RM4608 |

| MQTL_6.2 | 6 | 1.36 | 8 | 12.92 | 57.57 | RM6536 | RM1163 |

| MQTL_6.3 | 6 | 4.39 | 16 | 14.64 | 75.97 | RM253 | RM2126 |

| MQTL_6.4 | 6 | 0.42 | 8 | 13.61 | 96.1 | RM7488 | RM6836 |

| MQTL_6.5 | 6 | 0.44 | 4 | 10.89 | 111.31 | RM527 | RM564 |

| MQTL_6.6 | 6 | 3.96 | 13 | 18.37 | 122.28 | RM7583 | RM3187 |

| MQTL_6.7 | 6 | 6.36 | 7 | 19.34 | 152.74 | RM275 | RM5371 |

| MQTL_6.8 | 6 | 1.75 | 9 | 21.47 | 191.95 | RM5463 | RM1150 |

| MQTL_7.1 | 7 | 2.34 | 5 | 14.64 | 40.76 | RM3224 | RG528 |

| MQTL_7.2 | 7 | 3.09 | 7 | 13.43 | 67.28 | RM3186 | RM8022 |

| MQTL_7.3 | 7 | 3.4 | 5 | 10.18 | 72.89 | RM8022 | RM432 |

| MQTL_7.4 | 7 | 0.68 | 7 | 24.99 | 92.48 | RM560 | RM3743 |

| MQTL_7.5 | 7 | 7.56 | 2 | 11.25 | 106.72 | RM5508 | RM3583 |

| MQTL_7.6 | 7 | 3.24 | 5 | 11.14 | 128.29 | RM234 | RM5720 |

| MQTL_7.7 | 7 | 4 | 13 | 17.72 | 148.33 | RM478 | RM6650 |

| MQTL_7.8 | 7 | 0.99 | 3 | 13.17 | 176.39 | RM2789 | RM248 |

| MQTL_8.1 | 8 | 0.41 | 13 | 20.20 | 15.67 | RM6925 | RM2680 |

| MQTL_8.2 | 8 | 6.03 | 8 | 17.76 | 52.34 | RM5068 | RM2584 |

| MQTL_8.3 | 8 | 1.22 | 18 | 14.73 | 73.61 | RM8243 | RM1384 |

| MQTL_8.4 | 8 | 4.03 | 4 | 7.93 | 90.21 | RM3459 | RM7356 |

| MQTL_8.5 | 8 | 0.92 | 21 | 23.11 | 125.73 | RM3754 | RM3120 |

| MQTL_9.1 | 9 | 2.45 | 23 | 11.15 | 84 | RM316 | RM5688 |

| MQTL_9.2 | 9 | 0.1 | 65 | 15.10 | 130.37 | RM5661 | RZ228 |

| MQTL_10.1 | 10 | 20.4 | 3 | 37.36 | 21.64 | RM330 | RM3229 |

| MQTL_10.2 | 10 | 3.03 | 11 | 23.53 | 48.55 | RM6207 | RM5348 |

| MQTL_10.3 | 10 | 8.19 | 1 | 8.90 | 60.2 | RM6144 | RM7300 |

| MQTL_10.4 | 10 | 13.26 | 3 | 23.31 | 86.01 | RM216 | RM3451 |

| MQTL_10.5 | 10 | 12.2 | 4 | 27.52 | 116.18 | RM496 | RM590 |

| MQTL_11.1 | 11 | 10.24 | 10 | 36.02 | 41.22 | RM3717 | S20163S |

| MQTL_11.2 | 11 | 10.78 | 8 | 35.59 | 73.53 | RM3701 | RM457 |

| MQTL_11.3 | 11 | 1.91 | 2 | 13.23 | 91.67 | RM7391 | RM5824 |

| MQTL_11.4 | 11 | 1.92 | 8 | 15.91 | 104.69 | RM209 | RM5349 |

| MQTL_11.5 | 11 | 0.64 | 15 | 23.32 | 108.33 | RG2 | RM206 |

| MQTL_11.6 | 11 | 0.01 | 11 | 16.07 | 124.65 | RM206 | RM7170 |

| MQTL_12.1 | 12 | 7.88 | 3 | 15.79 | 27.11 | RM19 | RM453 |

| MQTL_12.2 | 12 | 13.04 | 2 | 18.78 | 52.26 | RM1302 | RM7195 |

| MQTL_12.3 | 12 | 4.82 | 12 | 15.90 | 72.09 | RM101 | RM1261 |

| MQTL_12.4 | 12 | 0.2 | 2 | 2.45 | 87.92 | RM3331 | RM6869 |

| MQTL_12.5 | 12 | 10.6 | 2 | 15.50 | 100.06 | RM6396 | RM235 |

| MQTL_12.6 | 12 | 1.46 | 11 | 16.58 | 117.49 | RM1300 | RM1310 |

References

- Xing, Y.; Zhang, Q. Genetic and Molecular Bases of Rice Yield. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2010, 61, 421–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tester, M.; Langridge, P. Breeding Technologies to Increase Crop Production in a Changing World. Science 2010, 327, 818–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singhal, A.; Tien, Y.-Y.; Hsia, R.Y. Racial-Ethnic Disparities in Opioid Prescriptions at Emergency Department Visits for Conditions Commonly Associated with Prescription Drug Abuse. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0159224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todaka, D.; Shinozaki, K.; Yamaguchi-Shinozaki, K. Recent advances in the dissection of drought-stress regulatory networks and strategies for development of drought-tolerant transgenic rice plants. Front. Plant Sci. 2015, 6, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panda, D.; Mishra, S.S.; Behera, P.K. Drought Tolerance in Rice: Focus on Recent Mechanisms and Approaches. Rice Sci. 2021, 28, 119–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Yao, Y.; Wang, J.; Ruan, B.; Yu, Y. Advancing Stress-Resilient Rice: Mechanisms, Genes, and Breeding Strategies. Agriculture 2025, 15, 721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blum, A. Drought Resistance—Is It Really a Complex Trait? Funct. Plant Biol. 2011, 38, 753–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, C.; Ye, Y.; Qiu, T.; Huang, Y.; Ying, J.; Shen, Z. Drought-Tolerant Rice at Molecular Breeding Eras: An Emerging Reality. Rice Sci. 2024, 31, 179–189. [Google Scholar]

- Sandhu, N.; Kumar, A. Bridging the Rice Yield Gaps under Drought: QTLs, Genes, and their Use in Breeding Programs. Agronomy 2017, 7, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, S.; Das, A.; Sheoran, S.; Rakshit, S. QTL Meta-Analysis: An Approach to Detect Robust and Precise QTL. Trop. Plant Biol. 2023, 16, 225–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilgrami, S.S.; Ramandi, H.D.; Shariati, V.; Razavi, K.; Tavakol, E.; Fakheri, B.A.; Nezhad, N.M.; Ghaderian, M. Detection of genomic regions associated with tiller number in Iranian bread wheat under different water regimes using genome-wide association study. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 14034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swamy, B.M.; Vikram, P.; Dixit, S.; Ahmed, H.; Kumar, A. Meta-analysis of grain yield QTL identified during agricultural drought in grasses showed consensus. BMC Genom. 2011, 12, 319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saini, D.K.; Srivastava, P.; Pal, N.; Gupta, P.K. Meta-QTLs, ortho-meta-QTLs and candidate genes for grain yield and associated traits in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). Theor. Appl. Genet. 2022, 135, 1049–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, R.K.; Kota, S.; Flowers, T.J. Salt tolerance in rice: Seedling and reproductive stage QTL mapping come of age. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2021, 134, 3495–3533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, T.; Zhang, J.; Cao, J.; Cao, S.; Li, W.; Yang, G. A meta-analysis of low temperature tolerance QTL in maize. Electron. J. Biotechnol. 2022, 58, 82–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selamat, N.; Nadarajah, K.K. Meta-Analysis of Quantitative Traits Loci (QTL) Identified in Drought Response in Rice (Oryza sativa L.). Plants 2021, 10, 716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aloryi, K.D.; Okpala, N.E.; Guo, H.; Karikari, B.; Amo, A.; Bello, S.F.; Saini, D.K.; Akaba, S.; Tian, X. Integrated meta-analysis and transcriptomics pinpoint genomic loci and novel candidate genes associated with submergence tolerance in rice. BMC Genom. 2024, 25, 338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, W.; Zhang, C.; Qiang, Y.; Zhong, H.; Zhao, G.; Li, Y. Integrated RNA-seq Analysis and Meta-QTLs Mapping Provide Insights into Cold Stress Response in Rice Seedling Roots. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 4615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadaw, R.B.; Dixit, S.; Raman, A.; Mishra, K.K.; Vikram, P.; Swamy, B.M.; Cruz, M.T.S.; Maturan, P.T.; Pandey, M.; Kumar, A. A QTL for high grain yield under lowland drought in the background of popular rice variety Sabitri from Nepal. Field Crop Res. 2013, 144, 281–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, W.; Zhao, H.; Zou, D. Detection of main-effect and epistatic QTL for yield-related traits in rice under drought stress and normal conditions. Can. J. Plant Sci. 2014, 94, 633–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.-H.; Hur, Y.-J.; Han, S.-I.; Cho, J.-H.; Kim, K.-M.; Lee, J.-H.; Song, Y.-C.; Kwon, Y.-U.; Shin, D. Drought-tolerant QTL qVDT11 leads to stable tiller formation under drought stress conditions in rice. Plant Sci. 2017, 256, 131–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baghyalakshmi, K.; Jeyaprakash, P.; Ramchander, S.; Raveendran, M.; Robin, S. Fine mapping of rice drought QTL and study on combined effect of QTL for their physiological parameters under moisture stress condition. J. Appl. Nat. Sci. 2016, 8, 1992–1998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandhu, N.; Singh, A.; Dixit, S.; Cruz, M.T.S.; Maturan, P.C.; Jain, R.K.; Kumar, A. Identification and mapping of stable QTL with main and epistasis effect on rice grain yield under upland drought stress. BMC Genet. 2014, 15, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixit, S.; Singh, A.; Cruz, M.T.S.; Maturan, P.T.; Amante, M.; Kumar, A. Multiple major QTL lead to stable yield performance of rice cultivars across varying drought intensities. BMC Genet. 2014, 15, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, L.; Ma, J.; Ma, X.; Cui, D.; Han, B.; Sun, J.; Han, L. QTL analysis of drought tolerance traits in rice during the vegetative growth period. Euphytica 2023, 219, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Songping, H.; Ying, Z.; Lin, Z.; Xudong, Z.; Zhenggong, W.; Lin, L.; Lijun, L.; Qingming, Z. QTL analysis of floral traits of rice (Oryza sativa L.) under well-watered and drought stress conditions. Genes Genom. 2009, 31, 173–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barik, S.R.; Pandit, E.; Pradhan, S.K.; Singh, S.; Swain, P.; Mohapatra, T. QTL Mapping for Relative Water Content Trait at Re-productive Stage Drought Stress in Rice. Indian J. Genet. 2018, 78, 401–408. [Google Scholar]

- Mardani, Z.; Rabiei, B.; Sabouri, H.; Sabouri, A. Mapping of QTLs for Germination Characteristics under Non-stress and Drought Stress in Rice. Rice Sci. 2013, 20, 391–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Mei, H.; Yu, X.; Zou, G.; Liu, H.; Hu, S.; Li, M.; Wu, J.; Chen, L.; Luo, L. QTL analysis of panicle neck diameter, a trait highly correlated with panicle size, under well-watered and drought conditions in rice (Oryza sativa L.). Plant Sci. 2008, 174, 71–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, V.; Verma, R.K.; Dey, P.; Chetia, S.; Baruah, A.; Modi, M. QTLs associated with yield attributing traits under drought stress in upland rice cultivar of Assam. Oryza-An Int. J. Rice 2017, 54, 253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.-Y.; Ali, J.; Fu, B.-Y.; Xu, J.-L.; Zhao, M.-F.; Jiang, Y.-Z.; Zhu, L.-H.; Shi, Y.-Y.; Yao, D.-N.; Gao, Y.-M.; et al. Detection of Drought-Related Loci in Rice at Reproductive Stage Using Selected Introgressed Lines. Agric. Sci. China 2011, 10, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, S.-P.; Yang, H.; Zou, G.-H.; Liu, H.-Y.; Liu, G.-L.; Mei, H.-W.; Cai, R.; Li, M.-S.; Luo, L.-J. Relationship Between Coleoptile Length and Drought Resistance and Their QTL Mapping in Rice. Rice Sci. 2007, 14, 13–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manickavelu, A.; Nadarajan, N.; Ganesh, S.K.; Gnanamalar, R.P.; Babu, R.C. Drought tolerance in rice: Morphological and molecular genetic consideration. Plant Growth Regul. 2006, 50, 121–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saikumar, S.; Gouda, P.K.; Saiharini, A.; Varma, C.M.K.; Vineesha, O.; Padmavathi, G.; Shenoy, V. Major QTL for enhancing rice grain yield under lowland reproductive drought stress identified using an O. sativa/O. glaberrima introgression line. Field Crop Res. 2014, 163, 119–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barik, S.; Pandit, E.; Mohanty, S.; Pradhan, S. QTL mapping for traits at reproductive stage drought stress in rice using single marker analysis. Oryza-An Int. J. Rice 2018, 55, 134–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sellamuthu, R.; Ranganathan, C.; Serraj, R. Mapping QTLs for Reproductive-Stage Drought Resistance Traits using an Advanced Backcross Population in Upland Rice. Crop Sci. 2015, 55, 1524–1536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.T.T.; Klueva, N.; Chamareck, V.; Aarti, A.; Magpantay, G.; Millena, A.C.M.; Pathan, M.S.; Nguyen, H.T. Saturation mapping of QTL regions and identification of putative candidate genes for drought tolerance in rice. Mol. Genet. Genom. 2004, 272, 35–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Mei, H.; Liu, H.; Yu, X.; Zou, G.; Luo, L. Sensitivities of rice grain yield and other panicle characters to late-stage drought stress revealed by phenotypic correlation and QTL analysis. Mol. Breed. 2009, 25, 603–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.L.; Pathan, M.S.; Zhang, J.; Bai, G.; Sarkarung, S.; Nguyen, H.T. Mapping QTLs for root traits in a recombinant inbred population from two indica ecotypes in rice. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2000, 101, 756–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernier, J.; Kumar, A.; Ramaiah, V.; Spaner, D.; Atlin, G. A Large-Effect QTL for Grain Yield under Reproductive-Stage Drought Stress in Upland Rice. Crop Sci. 2007, 47, 507–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Courtois, B.; Shen, L.; Petalcorin, W.; Carandang, S.; Mauleon, R.; Li, Z. Locating QTLs controlling constitutive root traits in the rice population IAC 165 × Co39. Euphytica 2003, 134, 335–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, J.; Yin, X.; Struik, P.C.; Stomph, T.J.; Wang, H. Using chromosome introgression lines to map quantitative trait loci for photosynthesis parameters in rice (Oryza sativa L.) leaves under drought and well-watered field conditions. J. Exp. Bot. 2011, 63, 455–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemamalini, G.; Shashidhar, H.; Hittalmani, S. Molecular marker assisted tagging of morphological and physiological traits under two contrasting moisture regimes at peak vegetative stage in rice (Oryza sativa L.). Euphytica 2000, 112, 69–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horii, H.; Nemoto, K.; Miyamoto, N.; Harada, J. Quantitative trait loci for adventitious and lateral roots in rice. Plant Breed. 2006, 125, 198–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamoshita, A.; Wade, L.; Ali, M.; Pathan, M.; Zhang, J.; Sarkarung, S.; Nguyen, H. Mapping QTLs for root morphology of a rice population adapted to rainfed lowland conditions. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2002, 104, 880–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamoshita, A.; Zhang, J.; Siopongco, J.; Sarkarung, S.; Nguyen, H.T.; Wade, L.J. Effects of Phenotyping Environment on Iden-tification of Quantitative Trait Loci for Rice Root Morphology under Anaerobic Conditions. Crop Sci. 2002, 42, 255–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kato, Y.; Hirotsu, S.; Nemoto, K.; Yamagishi, J. Identification of QTLs controlling rice drought tolerance at seedling stage in hydroponic culture. Euphytica 2007, 160, 423–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.; Venuprasad, R.; Atlin, G. Genetic analysis of rainfed lowland rice drought tolerance under naturally-occurring stress in eastern India: Heritability and QTL effects. Field Crop Res. 2007, 103, 42–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanceras, J.C.; Pantuwan, G.; Jongdee, B.; Toojinda, T. Quantitative Trait Loci Associated with Drought Tolerance at Reproductive Stage in Rice. Plant Physiol. 2004, 135, 384–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Mu, P.; Li, C.; Zhang, H.; Li, Z.; Gao, Y.; Wang, X. QTL mapping of root traits in a doubled haploid population from a cross between upland and lowland japonica rice in three environments. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2005, 110, 1244–1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacMillan, K.; Emrich, K.; Piepho, H.-P.; Mullins, C.E.; Price, A.H. Assessing the importance of genotype × environment interaction for root traits in rice using a mapping population II: Conventional QTL analysis. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2006, 113, 953–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez, S.M.; Boopathi, N.M.; Kumar, S.S.; Ramasubramanian, T.; Chengsong, Z.; Jeyaprakash, P.; Senthil, A.; Babu, R.C. Molecular mapping and location of QTLs for drought-resistance traits in indica rice (Oryza sativa L.) lines adapted to target environments. Acta Physiol. Plant. 2009, 32, 355–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palanog, A.D.; Swamy, B.M.; Shamsudin, N.A.A.; Dixit, S.; Hernandez, J.E.; Boromeo, T.H.; Cruz, P.C.S.; Kumar, A. Grain yield QTLs with consistent-effect under reproductive-stage drought stress in rice. Field Crop Res. 2014, 161, 46–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, A.H.; Steele, K.A.; Moore, B.J.; Barraclough, P.P.; Clark, L.J. A combined RFLP and AFLP linkage map of upland rice (Oryza sativa L.) used to identify QTLs for root-penetration ability. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2000, 100, 49–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, A.H.; Steele, K.A.; Moore, B.J.; Jones, R.G.W. Upland Rice Grown in Soil-®lled Chambers and Exposed to Contrasting Water-De®cit Regimes II. Mapping Quantitative Trait Loci for Root Morphology and Distribution. Field Crops Res. 2002, 76, 25–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prince, S.J.; Beena, R.; Gomez, S.M.; Senthivel, S.; Babu, R.C. Mapping Consistent Rice (Oryza sativa L.) Yield QTLs under Drought Stress in Target Rainfed Environments. Rice 2015, 8, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redofia, E.D.; Mackill, D.J. Mapping Quantitative Trait Loci for Seedling Vigor in Rice Using RFLPs. Theor. Appl. Genet. 1996, 92, 395–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabar, M.; Shabir, G.; Shah, S.M.; Aslam, K.; Naveed, S.A.; Arif, M. Identification and mapping of QTLs associated with drought tolerance traits in rice by a cross between Super Basmati and IR55419-04. Breed. Sci. 2019, 69, 169–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sandhu, N.; Jain, S.; Kumar, A.; Mehla, B.S.; Jain, R. Genetic variation, linkage mapping of QTL and correlation studies for yield, root, and agronomic traits for aerobic adaptation. BMC Genet. 2013, 14, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, L.; Courtois, B.; McNally, K.L.; Robin, S.; Li, Z. Evaluation of near-isogenic lines of rice introgressed with QTLs for root depth through marker-aided selection. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2001, 103, 75–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solis, J.; Gutierrez, A.; Mangu, V.; Sanchez, E.; Bedre, R.; Linscombe, S.; Baisakh, N. Genetic Mapping of Quantitative Trait Loci for Grain Yield under Drought in Rice under Controlled Greenhouse Conditions. Front. Chem. 2018, 5, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripathy, J.N.; Zhang, J.; Robin, S.; Nguyen, T.T.; Nguyen, H.T. QTLs for cell-membrane stability mapped in rice (Oryza sativa L.) under drought stress. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2000, 100, 1197–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.G.; Li, X.Q.; Xue, Y.; Huang, Y.W.; Gao, J.; Xing, Y.Z. Comparison of quantitative trait loci controlling seedling characteristics at two seedling stages using rice recombinant inbred lines. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2004, 109, 640–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, B.; Xue, W.; Xiong, L.; Yu, X.; Luo, L.; Cui, K.; Jin, D.; Xing, Y.; Zhang, Q. Genetic Basis of Drought Resistance at Reproductive Stage in Rice: Separation of Drought Tolerance from Drought Avoidance. Genetics 2006, 172, 1213–1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- You, J.; Li, Q.; Yue, B.; Xue, W.-Y.; Luo, L.-J.; Xiong, L.-Z. Identification of Quantitative Trait Loci for ABA Sensitivity at Seed Germination and Seedling Stages in Rice. Acta Genet. Sin. 2006, 33, 532–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yue, B.; Xue, W.; Luo, L.; Xing, Y. Identification of quantitative trait loci for four morphologic traits under water stress in rice (Oryza sativa L.). J. Genet. Genom. 2008, 35, 569–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, B.; Xiong, L.; Xue, W.; Xing, Y.; Luo, L.; Xu, C. Genetic analysis for drought resistance of rice at reproductive stage in field with different types of soil. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2005, 111, 1127–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zheng, H.G.; Aarti, A.; Pantuwan, G.; Nguyen, T.T.; Tripathy, J.N.; Sarial, A.K.; Robin, S.; Babu, R.C.; Nguyen, B.D.; et al. Locating genomic regions associated with components of drought resistance in rice: Comparative mapping within and across species. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2001, 103, 19–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, B.S.; Yang, L.; Zhang, W.P.; Mao, C.Z.; Wu, Y.R.; Yi, K.K.; Liu, F.Y.; Wu, P. Mapping QTLs and candidate genes for rice root traits under different water-supply conditions and comparative analysis across three populations. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2003, 107, 1505–1515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, H.; Babu, M.R.C.; Pathan, M.S.; Ali, L.; Huang, N.; Courtois, B.; Nguyen, H.T. Quantitative Trait Loci for Root-Penetration Ability and Root Thickness in Rice: Comparison of Genetic Backgrounds. Genome 2000, 43, 53–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, B.; Yang, L.; Mao, C.; Huang, Y.; Wu, P. Comparison of QTLs for rice seedling morphology under different water supply conditions. J. Genet. Genom. 2008, 35, 473–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Li, S.; Du, H.; Cui, J.; Xu, S.; Wang, J.; Liu, H.; Zou, D.; Lu, W.; Zheng, H. The Identification of Drought Tolerance Candidate Genes in Oryza Sativa L. Ssp. Japonica Seedlings through Genome-Wide Association Study and Linkage Mapping. Agriculture 2024, 14, 603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadam, N.N.; Struik, P.C.; Rebolledo, M.C.; Yin, X.; Jagadish, S.V.K. Genome-Wide Association Reveals Novel Genomic Loci Controlling Rice Grain Yield and Its Component Traits under Water-Deficit Stress during the Reproductive Stage. J. Exp. Bot. 2018, 69, 4017–4032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhandari, A.; Sandhu, N.; Bartholome, J.; Cao-Hamadoun, T.-V.; Ahmadi, N.; Kumari, N.; Kumar, A. Genome-Wide Association Study for Yield and Yield Related Traits under Reproductive Stage Drought in a Diverse Indica-Aus Rice Panel. Rice 2020, 13, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthukumar, C.; Subathra, T.; Aiswarya, J.; Gayathri, V.; Babu, R.C. Comparative Genome-Wide Association Studies for Plant Production Traits under Drought in Diverse Rice (Oryza Sativa L.) Lines Using SNP and SSR Markers. CURRENT SCIENCE 2015, 109. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/24905698 (accessed on 29 May 2025).

- Sakhare, A.S.; Kumar, S.; Ellur, R.K.; Prahalada, G.D.; Kota, S.; Kumar, R.R.; Ray, S.; Mandal, B.N.; Chinnusamy, V. Genome-Wide Association Study on Root Traits under Non-Stress and Osmotic Stress Conditions to Improve Drought Tolerance in Rice (Oryza Sativa Lin.). Acta Physiol. Plant 2025, 47, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Gao, Z.; Zhang, W.; Qian, Y.; Bai, D.; Zhao, X.; Bao, Y.; Zheng, Z.; Wang, X.; Li, J.; et al. Genome-Wide Association Analysis Reveals the Gene Loci of Yield Traits under Drought Stress at the Rice Reproductive Stage. Agronomy 2023, 13, 2096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, Y.; Hassan, M.A.; Cheng, X.; Li, Y.; Liu, H.; Fang, W.; Zhu, Q.; Wang, S. QTL Mapping and Analysis for Drought Tolerance in Rice by Genome-Wide Association Study. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1223782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, J.; Peng, X.; Guo, S.; Lu, J.; Shi, X.; Sun, Y.; Yang, J. Innovation and Implement of Green Technology in Rice Production to Increase Yield and Resource Use Efficiency. Front. Agric. Sci. Eng. 2025, 12, 478–492. [Google Scholar]

- Hua, J.; Xing, Y.; Wu, W.; Xu, C.; Sun, X.; Yu, S.; Zhang, Q. Single-locus heterotic effects and dominance by dominance interactions can adequately explain the genetic basis of heterosis in an elite rice hybrid. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2003, 100, 2574–2579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, B.; Sleper, D.A.; Lu, P.; Shannon, J.G.; Nguyen, H.T.; Arelli, P.R. QTLs Associated with Resistance to Soybean Cyst Nematode in Soybean: Meta-Analysis of QTL Locations. Crop Sci. 2006, 46, 595–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loni, F.; Ismaili, A.; Nakhoda, B.; Ramandi, H.D.; Shobbar, Z.-S. The genomic regions and candidate genes associated with drought tolerance and yield-related traits in foxtail millet: An integrative meta-analysis approach. Plant Growth Regul. 2023, 101, 169–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eweda, M.A.; Yabes, J. Molecular and Physiological Characterizations of Roots under Drought Stress in Rice: A Comprehensive Review. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2025, 225, 110012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goyal, S.; Sandhu, D. Defining Genomic Landscape for Identification of Potential Candidate Resistance Genes Associated with Major Rice Diseases through MetaQTL Analysis. J. Biosci. 2024, 49, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devanna, B.N.; Sucharita, S.; Sunitha, N.C.; Anilkumar, C.; Singh, P.K.; Pramesh, D.; Samantaray, S.; Behera, L.; Katara, J.L.; Parameswaran, C.; et al. Refinement of rice blast disease resistance QTLs and gene networks through meta-QTL analysis. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 16458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khahani, B.; Taghavi, E. Meta-QTL and Ortho-MQTL Analyses Identified Genomic Regions Controlling Rice Yield, Yield-Related Traits and Root Architecture under Water Deficit Conditions. Sci. Rep. 2011, 11, 6942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daryani, P.; Amirbakhtiar, N.; Soorni, J.; Loni, F.; Ramandi, H.D.; Shobbar, Z.-S. Uncovering the Genomic Regions Associated with Yield Maintenance in Rice Under Drought Stress Using an Integrated Meta-Analysis Approach. Rice 2024, 17, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Y.; Zhang, W.; Lin, X.; Xu, S.; Xu, J.; Li, Z. Simultaneous Improvement and Genetic Dissection of Drought Tolerance Using Selected Breeding Populations of Rice. Front. Plant Sci. 2018, 9, 320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Lin, X.-F.; Li, L.; Piao, R.-H.; Wu, S.; Song, A.; Gao, M.; Jin, Y.-M. CRISPR/Cas9-mediated knockout of Bsr-d1 enhances the blast resistance of rice in Northeast China. Plant Cell Rep. 2024, 43, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, T.-C.; Chen, R.-J.; Yu, R.-R.; Zeng, H.-L.; Zhang, D.-P. Differential global genomic changes in rice root in response to low-, middle-, and high-osmotic stresses. Acta Physiol. Plant. 2009, 31, 773–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, S.; Liu, X.; Huang, Y.; Ma, Z.; Wang, W.; Li, N.; Liu, Z.; Yang, H.; Zhang, X. The Effect of Simulated Drought on Root System in Rice Cultivars with Differential Drought Stress Tolerance. Mol. Plant Breed. 2024. Available online: https://link.cnki.net/urlid/46.1068.S.20240312.1350.014 (accessed on 28 May 2024). (In Chinese).

- Ma, X.; Xia, H.; Liu, Y.; Wei, H.; Zheng, X.; Song, C.; Chen, L.; Liu, H.; Luo, L. Transcriptomic and Metabolomic Studies Disclose Key Metabolism Pathways Contributing to Well-maintained Photosynthesis under the Drought and the Consequent Drought-Tolerance in Rice. Front. Plant Sci. 2016, 7, 1886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Chung, Y.S.; Lee, E.; Tripathi, P.; Heo, S.; Kim, K.-H. Root Response to Drought Stress in Rice (Oryza sativa L.). Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 1513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fonta, J.E.; Giri, J.; Vejchasarn, P.; Lynch, J.P.; Brown, K.M. Spatiotemporal responses of rice root architecture and anatomy to drought. Plant Soil 2022, 479, 443–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, H.; Yu, J.; Miao, J.; Li, J.; Zhang, H.; Wang, X.; Liu, P.; Zhao, Y.; Jiang, C.; Yin, Z.; et al. Natural Variation in OsLG3 Increases Drought Tolerance in Rice by Inducing ROS Scavenging. Plant Physiol. 2018, 178, 451–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nadarajah, K.K. ROS Homeostasis in Abiotic Stress Tolerance in Plants. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 5208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, X.; He, Z.; Chen, N.; Tang, Z.; Wang, Q.; Cai, Y. The Roles of Environmental Factors in Regulation of Oxidative Stress in Plant. BioMed Res. Int. 2019, 2019, 9732325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, H.; Wu, B.; Amin, B.; Li, J.; Chen, Z.; Shi, J.; Huang, W.; Fang, Z. Amino Acid Regulation in Rice: Integrated Mechanisms and Agricultural Applications. Rice 2025, 18, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babitha, M.P.; Bhat, S.G.; Prakash, H.S.; Shetty, H.S. Differential induction of superoxide dismutase in downy mildew-resistant and -susceptible genotypes of pearl millet. Plant Pathol. 2002, 51, 480–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Zhu, P.; Yu, X.; Xu, J.; Liu, G. Physiological and Molecular Mechanisms of Rice Tolerance to Salt and Drought Stress: Advances and Future Directions. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 9404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Liu, L.; Zhou, T.; Chen, Y.; Zhou, H.; Lyu, J.; Zhang, D.; Shi, X.; Yuan, D.; Ye, N.; et al. Chalcone isomerase gene (OsCHI3) increases rice drought tolerance by scavenging ROS via flavonoid and ABA metabolic pathways. Crop J. 2025, 13, 372–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dossa, G.S.; Torres, R.; Henry, A.; Oliva, R.; Maiss, E.; Cruz, C.V.; Wydra, K. Rice response to simultaneous bacterial blight and drought stress during compatible and incompatible interactions. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 2016, 147, 115–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, Z.; Zhu, L.; Li, H.; Sun, B.; Liu, X.; Li, D.; Hu, W.; Wang, S.; Miao, X.; Shi, Z. ACL1-ROC4/5 complex reveals a common mechanism in rice response to brown planthopper infestation and drought. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 8107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghorbanzadeh, Z.; Hamid, R.; Jacob, F.; Zeinalabedini, M.; Salekdeh, G.H.; Ghaffari, M.R. Comparative metabolomics of root-tips reveals distinct metabolic pathways conferring drought tolerance in contrasting genotypes of rice. BMC Genom. 2023, 24, 15–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Fu, K.; Guo, W.; Zhang, X.; Li, C.; Li, C. Starch and Sugar Metabolism Response to Post-Anthesis Drought Stress During Critical Periods of Elite Wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) Endosperm Development. J. Plant Growth Regul. 2023, 42, 5476–5494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Yu, Q.; Fang, W.; Chen, M.; Li, T.; Liu, Y.; Liu, Z.; Chen, L.; Yu, S.; et al. Co-ordination of Growth and Drought Responses by GA-ABA Signaling in Rice. New Phytol. 2023, 240, 1149–1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Auler, P.A.; Souza, G.M.; Engela, M.R.G.d.S.; Amaral, M.N.D.; Rossatto, T.; da Silva, M.G.Z.; Furlan, C.M.; Maserti, B.; Braga, E.J.B. Stress memory of physiological, biochemical and metabolomic responses in two different rice genotypes under drought stress: The scale matters. Plant Sci. 2021, 311, 110994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Zhang, F.; Zhai, F.; Su, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Ge, Z.; Tilak, P.; Eirich, J.; Finkemeier, I.; Fu, L.; et al. Rice GLUTATHIONE PEROXIDASE1-mediated oxidation of bZIP68 positively regulates ABA-independent osmotic stress signaling. Mol. Plant 2022, 15, 651–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthuramalingam, P.; Krishnan, S.R.; Pothiraj, R.; Ramesh, M. Global Transcriptome Analysis of Combined Abiotic Stress Signaling Genes Unravels Key Players in Oryza sativa L.: An In silico Approach. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashyal, B.M.; Parmar, P.; Zaidi, N.W.; Aggarwal, R. Molecular Programming of Drought-Challenged Trichoderma harzianum-Bioprimed Rice (Oryza sativa L.). Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 655165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosugi, T.; Ohue, M. Design of Cyclic Peptides Targeting Protein–Protein Interactions Using AlphaFold. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 13257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Zhang, C.; Cai, M.; Luo, C.; Zhu, F.; Liang, Z. FuncPhos-STR: An integrated deep neural network for functional phosphosite prediction based on AlphaFold protein structure and dynamics. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 266, 131180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Darvasi, A.; Soller, M. A Simple Method to Calculate Resolving Power and Confidence Interval of QTL Map Location. Behav. Genet. 1997, 27, 125–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sosnowski, O.; Charcosset, A.; Joets, J. BioMercator V3: An upgrade of genetic map compilation and quantitative trait loci meta-analysis algorithms. Bioinformatics 2012, 28, 2082–2083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arcade, A.; Labourdette, A.; Falque, M.; Mangin, B.; Chardon, F.; Charcosset, A.; Joets, J. BioMercator: Integrating genetic maps and QTL towards discovery of candidate genes. Bioinformatics 2004, 20, 2324–2326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chardon, F.; Virlon, B.; Moreau, L.; Falque, M.; Joets, J.; Decousset, L.; Murigneux, A.; Charcosset, A. Genetic Architecture of Flowering Time in Maize as Inferred from Quantitative Trait Loci Meta-analysis and Synteny Conservation with the Rice Genome. Genetics 2004, 168, 2169–2185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daryani, P.; Ramandi, H.D.; Dezhsetan, S.; Mansuri, R.M.; Salekdeh, G.H.; Shobbar, Z.-S. Pinpointing genomic regions associated with root system architecture in rice through an integrative meta-analysis approach. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2021, 135, 81–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parents | Population Type a | Population Size | No. of Markers | Marker Type b | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IR77298-5-6-18/2*Sabitri | BC1 | 294 | 124 | SSR | (Yadaw et al. 2013) [19] |

| Xiaobaijingzi/Kongyu 131 | F2:7 RILs | 220 | 104 | SSR | (Xing, Zhao, and Zou 2014) [20] |

| Samgang/Nagdong | DH | 101 | 185 | SSR, STS | (Kim et al. 2017) [21] |

| IR64 X APO | BILs | 50 | 25 | SSR | (Baghyalakshmi et al. 2016) [22] |

| Kali Aus/2*IR64,Kali Aus/2*MTU1010 | BC1F4 | 300 | 600 | SSR | (Sandhu et al. 2014) [23] |

| IR55419-04/2*TDK1 | BC1F3:4 | 365 | 600 | SSR | (Dixit et al. 2014) [24] |

| Miyang 23/Jileng 1 | RIL | 253 | 291 | SSR | (Chen et al. 2023) [25] |

| CT9993-5-10-1-M/IR62266-42-6-2 | DH | 154 | 280 | RELP, AFLP, SSR | (Songping et al. 2011) [26] |

| CR 143-2-2/Krishnahamsa | RILs | 190 | 21 | SSR | (Barik et al., n.d.) [27] |

| Gharib/Sepidroud | F2:4 | 148 | 575 | SSR | (Zahra Mardani-2013) [28] |

| Zheshan97B/IRAT109 | F10 | 187 | 213 | SSRs | (G.L. Liu-2008) [29] |

| Banglami/Ranjit | F4 | 90 | 94 | SSR | (Vinay Sharma-2017) [30] |

| IR64/Khazar | BC2F2 | 208 | 83 | SSR | (CHEN Man-yuan-2011) [31] |

| Zhenshan 97B/IRAT109 | RILs | 195 | 213 | SSR | (HU Song-ping-2007) [32] |

| IR 58821/IR 52561 | RILs | 148 | 399 | RFLP, AFLP | (A. Manickavelu-2006) [33] |

| Swarna/WAB 450-I-B-P-157-2-1 | BIL | 202 | 412 | SSR | (Saikumar et al. 2014) [34] |

| CR143-2-2/Krishnahamsa | RIL | 190 | 201 | SSR | (Barik et al. 2018) [35] |

| Apo/Moroberekan | BC1F3 | 289 | 108 | SSR, STS | (Reena Sellamuthu-2015) [36] |

| CT9993-510-1-M/IR62266-42-6-2 | DH | 154 | 315 | RELP, AFLP, SSR | (Nguyen et al. 2004) [37] |

| Zheshan97B/IRAT109 | RILs | 187 | 213 | SSR | (Liu et al. 2010) [38] |

| IR58821–23-B-1–2-1/IR52561-UBN-1–1-2 | RIL | 166 | 399 | AFLP, RFLP | (Ali et al. 2000) [39] |

| Vandana/Way Rarem | F3 | 436 | 126 | SSR | (Bernier et al. 2007) [40] |

| IAC 165/CO39 | RIL | 125 | 182 | RFLP, SSR | (Courtois et al. 2003) [41] |

| Shennong265/Haogelao | RIL | 94 | 130 | SSR | (Gu et al. 2012) [42] |

| IR64/Azucena | DH | 56 | 175 | RFLP | (Hemamalini, Shashidhar, and Hittalmani 2000) [43] |

| Akihikari/IRAT109 | BILs | 106 | 113 | SSR | (Horii et al. 2006) [44] |

| CT9993/IR62266 | RILs | 184 | 399 | RFLP, AFLP | (Kamoshita et al. 2002) [45] |

| CT9993/IR62266 | DH | 220 | 315 | RELP, AFLP | (Kamoshita et al. 2002) [46] |

| Akihikari/IRAT109 | BILs | 106 | 57 | SSR | (Kato et al. 2008) [47] |

| CT9993/IR62266 | DH | 154 | 315 | AFLP | (Kumar, Venuprasad, and Atlin 2007) [48] |

| CT9993/IR62266 | DH | 154 | 315 | RFLP, AFLP, SSR | (Lanceras et al. 2004) [49] |

| IRAT109/Yuefu | DH | 116 | 336 | RELP, SSR | (Li et al. 2005) [50] |

| Bala/Azucena | RILs | 205 | 1151 | SSR | (MacMillan et al. 2006) [51] |

| Nootripathu/IR20 | RIL | 250 | 79 | SSR | (Michael Gomez et al. 2010) [52] |

| KaliAus X IR64 KaliAus X MTU1010 | BC | 300 | 600 | SSR | (Palanog et al. 2014) [53] |

| Bala/Azucena | RILs | 205 | 135 | RELP, AFLP | (Price et al. 2000) [54] |

| Bala/Azucena | RILs | 140 | 6 | SSR | (Price et al. 2002) [55] |

| Nootripathu/IR20 | RIL | 397 | 79 | SSR | (Prince et al. 2015) [56] |

| Labelle/Black Gora | F2 | 204 | 117 | RELP | (Redofia and Mackill, n.d.) [57] |

| IR55419-04/Super Basmati | F2 | 418 | 73 | SSR | (Sabar et al. 2019) [58] |

| HKR47/MAS26,MASARB25/Pusa Basmati | F2:3 | 1460 | 300 | SSR | (Sandhu et al. 2013) [59] |

| IR64/Azucena | BC3F2 | 29 | 60 | SSR | (Shen et al. 2001) [60] |

| Vandana/Cocodrie | F2:3 | 187 | 213 | InDels, SNP, SSR | (Solis et al. 2018) [61] |

| CT9993/IR62266 | DH | 104 | 315 | RFLP, AFLP, SSR | (Tripathy et al. 2000) [62] |

| Zhenshan97/Minghui63 | F2 RIL | 240 | 221 | RFLP, SSR | (Xu et al. 2004) [63] |

| Zhenshan97/IRAT109 | RIL | 180 | 245 | SSR | (Yue et al. 2006) [64] |

| IRAT109/Zhenshan97 | RIL | 154 | 220 | SSR | (You et al. 2006) [65] |

| IRAT109/Zhenshan97 | RIL | 180 | 220 | SSR | (Yue et al. 2008) [66] |

| Zhenshan97/IRAT109 | RIL | 180 | 220 | SSR | (Yue et al. 2005) [67] |

| IR1552/Azucena | RILs | 150 | 107 | RFLP, AFLP | (Zhang et al. 2001) [68] |

| R1552/Azucena | RILs | 96 | 103 | SSR | (Zheng et al. 2003) [69] |

| IR64/Azucena | DH | 135 | 135 | RFLP | (Zheng et al. 2000) [70] |

| Azucena/IR64 | DH | 96 | 189 | RFLP, SSR | (Zheng et al. 2008) [71] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jin, Y.; Dou, W.; Wang, T.; Jin, Z.; Wu, S. An Integrated Meta-QTL and Transcriptome Analysis Provides Candidate Genes Associated with Drought Tolerance in Rice Seedlings. Plants 2025, 14, 3645. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14233645

Jin Y, Dou W, Wang T, Jin Z, Wu S. An Integrated Meta-QTL and Transcriptome Analysis Provides Candidate Genes Associated with Drought Tolerance in Rice Seedlings. Plants. 2025; 14(23):3645. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14233645

Chicago/Turabian StyleJin, Yinji, Weize Dou, Tianhao Wang, Zhuo Jin, and Songquan Wu. 2025. "An Integrated Meta-QTL and Transcriptome Analysis Provides Candidate Genes Associated with Drought Tolerance in Rice Seedlings" Plants 14, no. 23: 3645. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14233645

APA StyleJin, Y., Dou, W., Wang, T., Jin, Z., & Wu, S. (2025). An Integrated Meta-QTL and Transcriptome Analysis Provides Candidate Genes Associated with Drought Tolerance in Rice Seedlings. Plants, 14(23), 3645. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14233645