Cattle Manure Fertilizer and Biostimulant Trichoderma Application to Mitigate Salinity Stress in Green Maize Under an Agroecological System in the Brazilian Semiarid Region

Abstract

1. Introduction

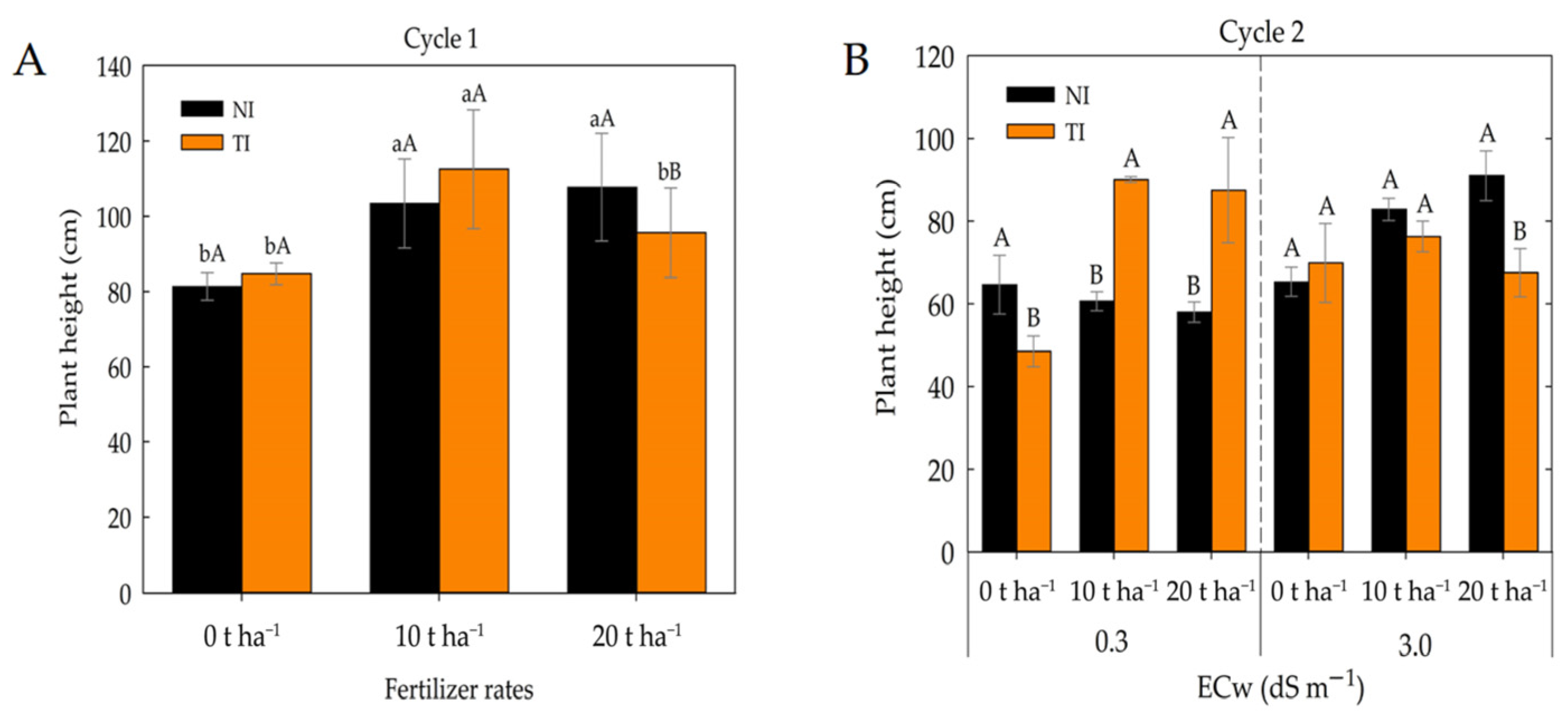

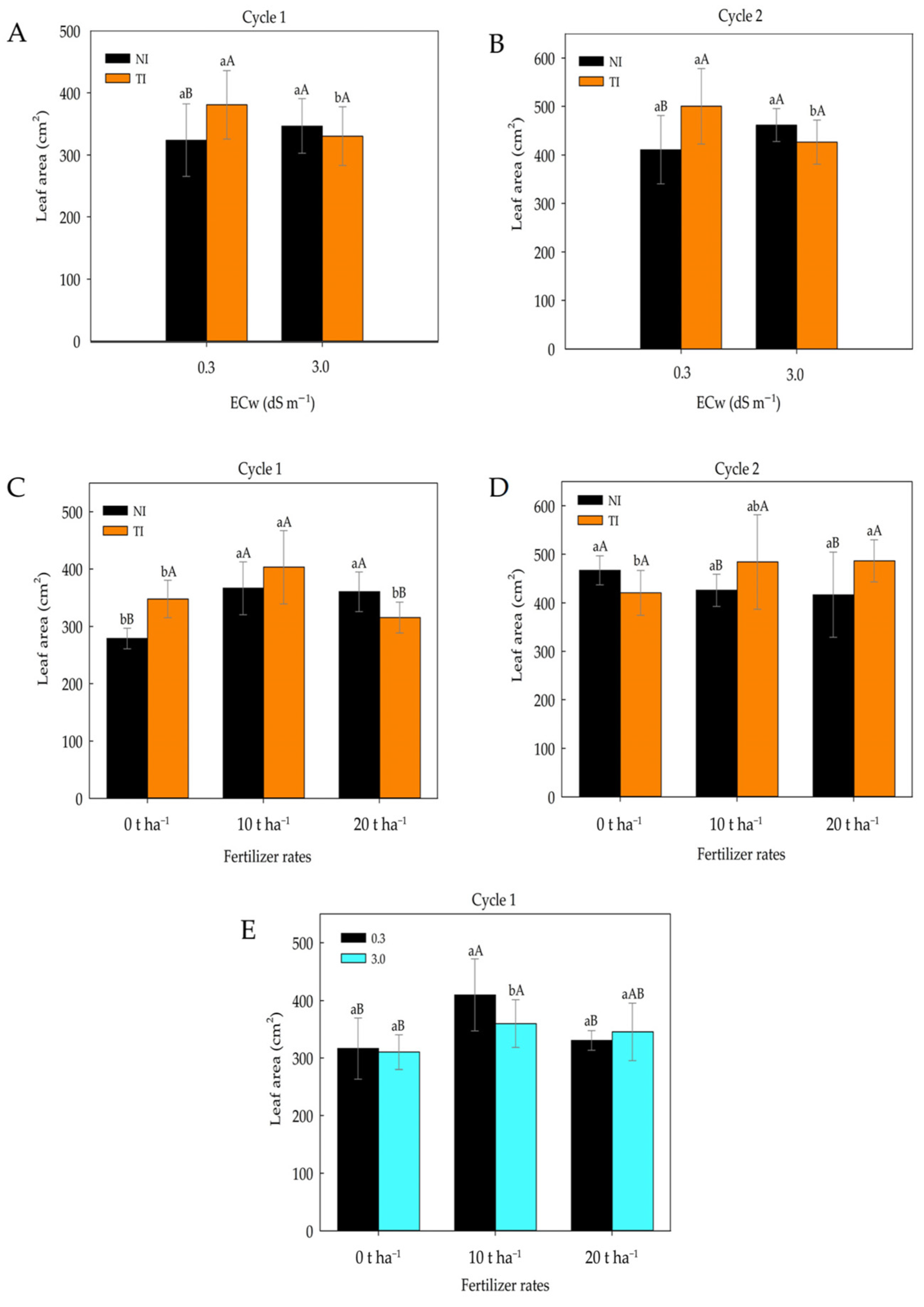

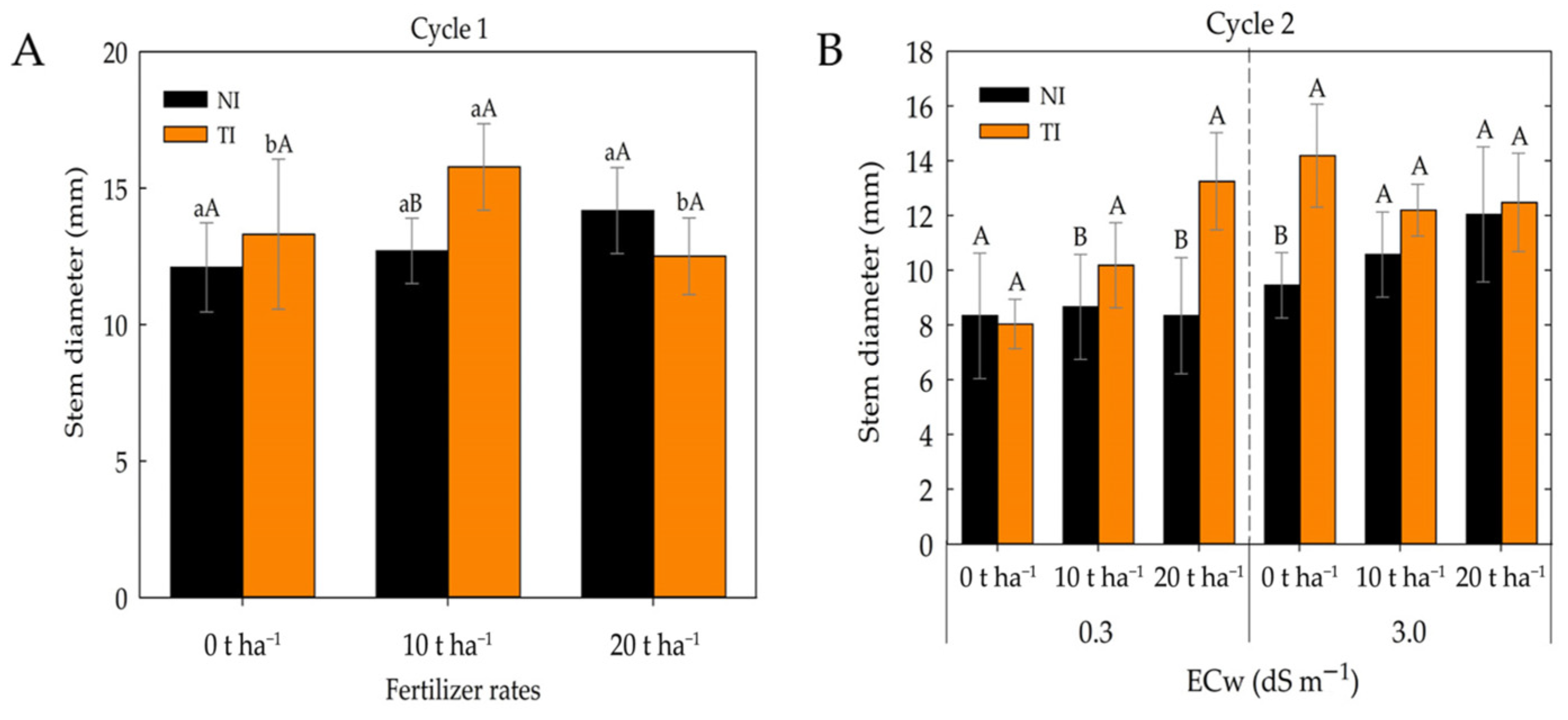

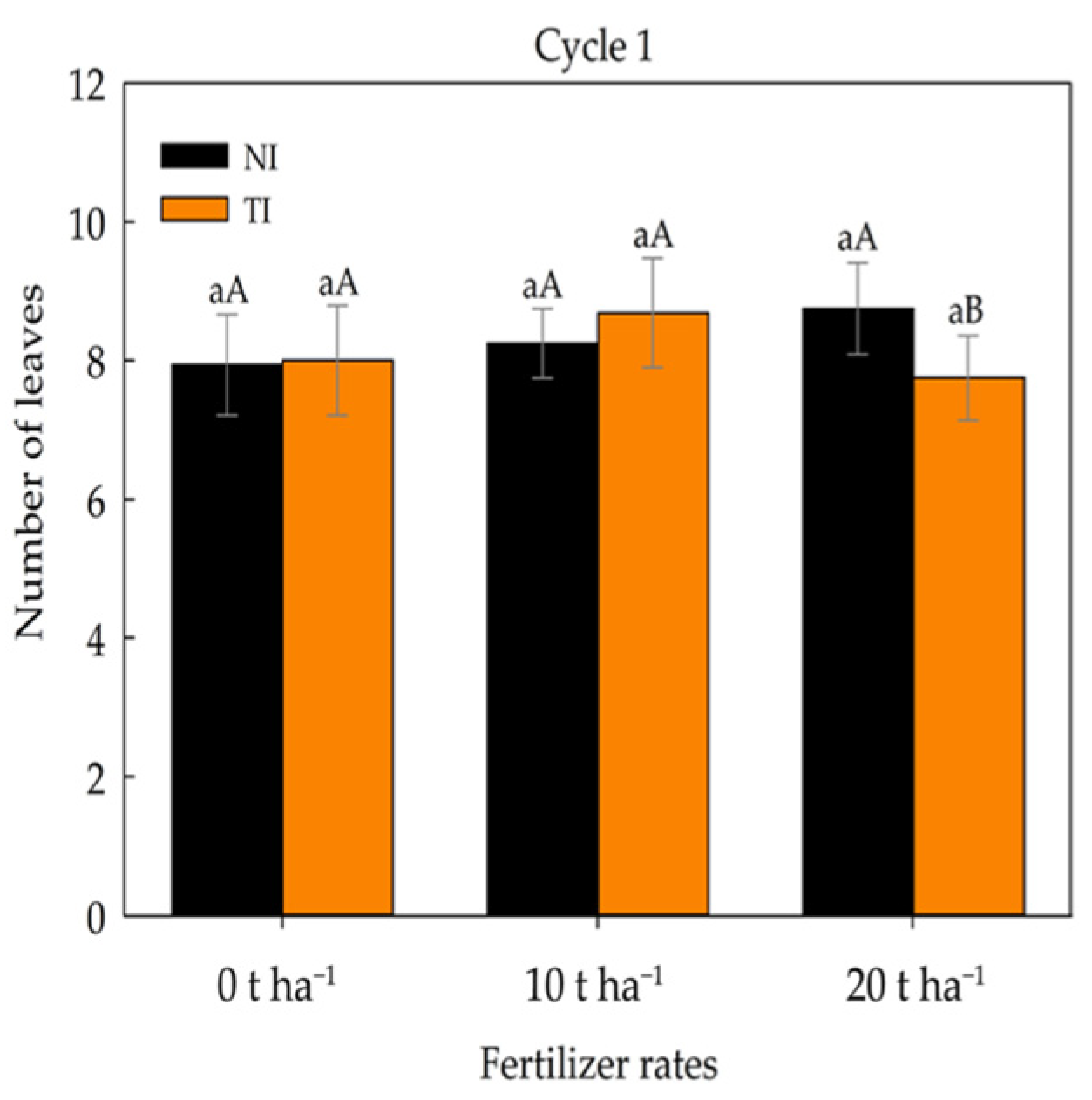

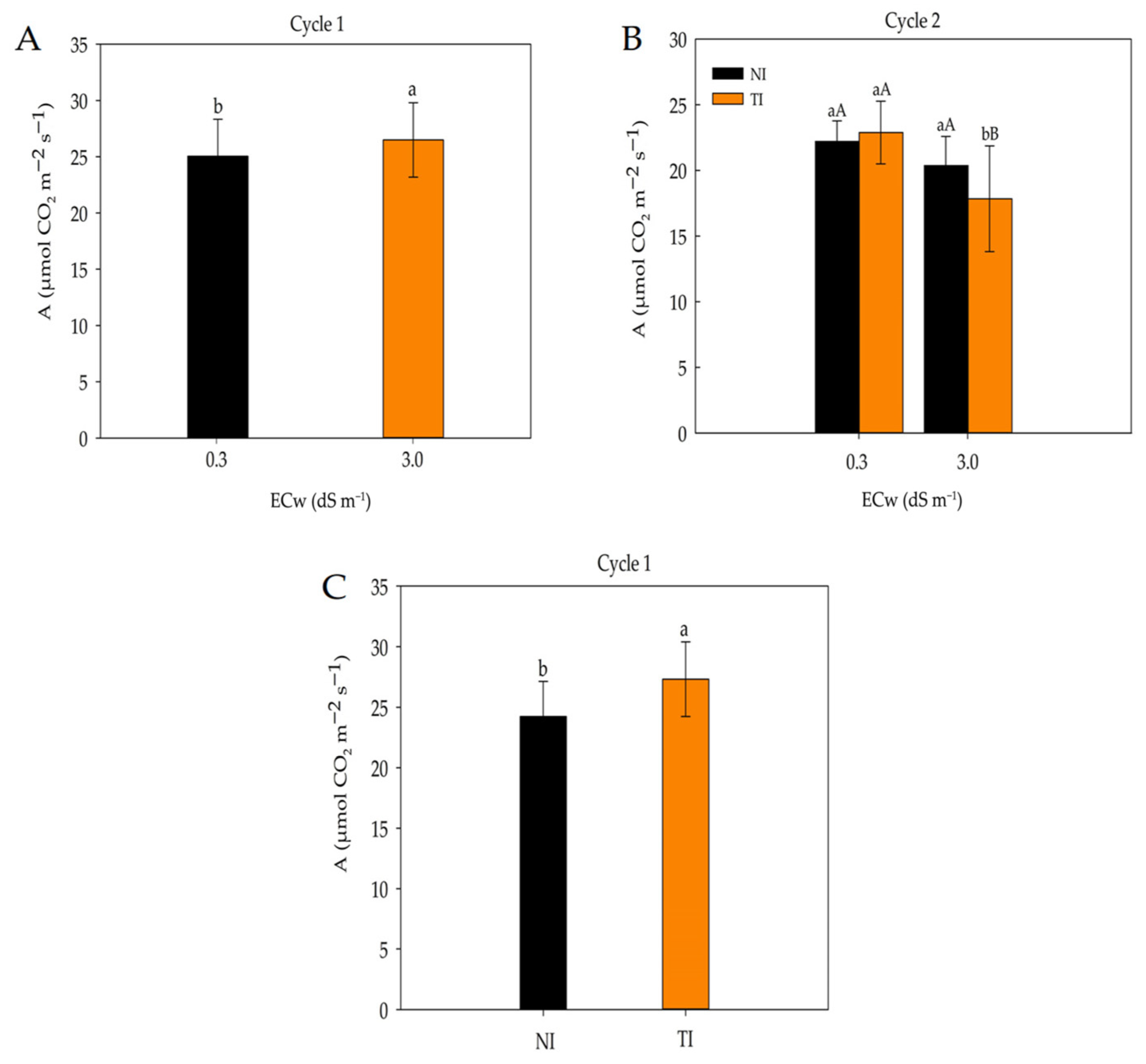

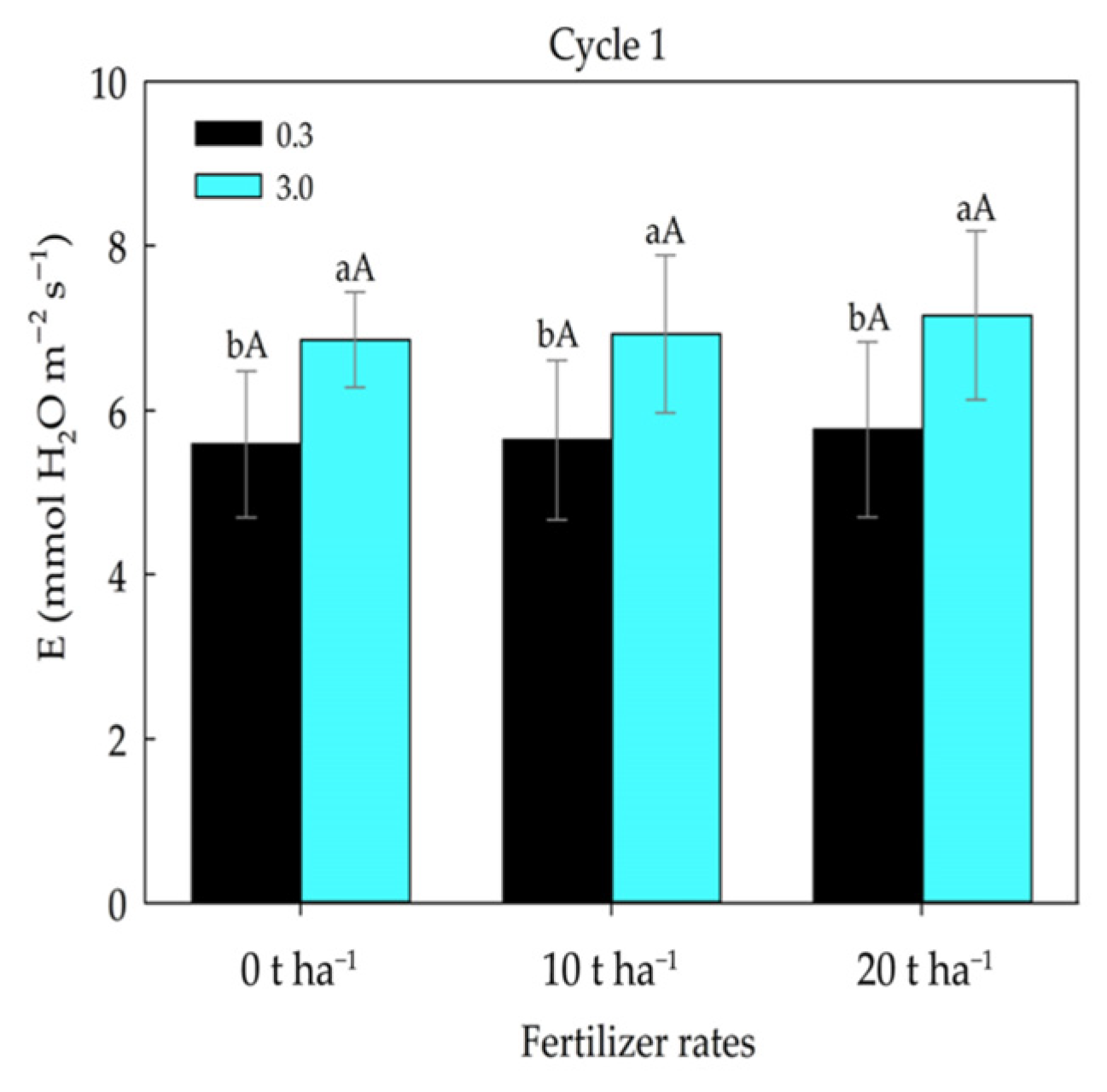

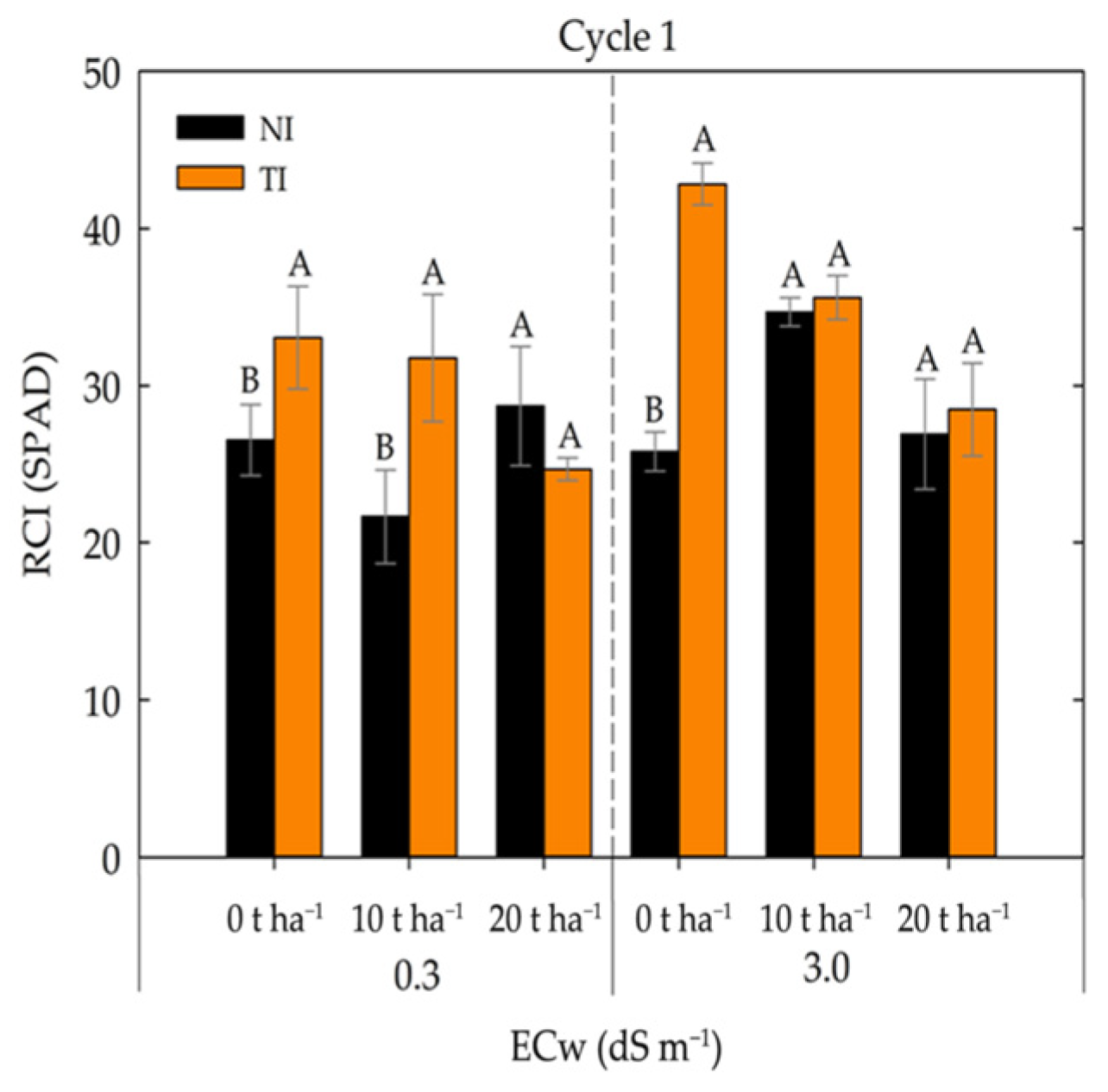

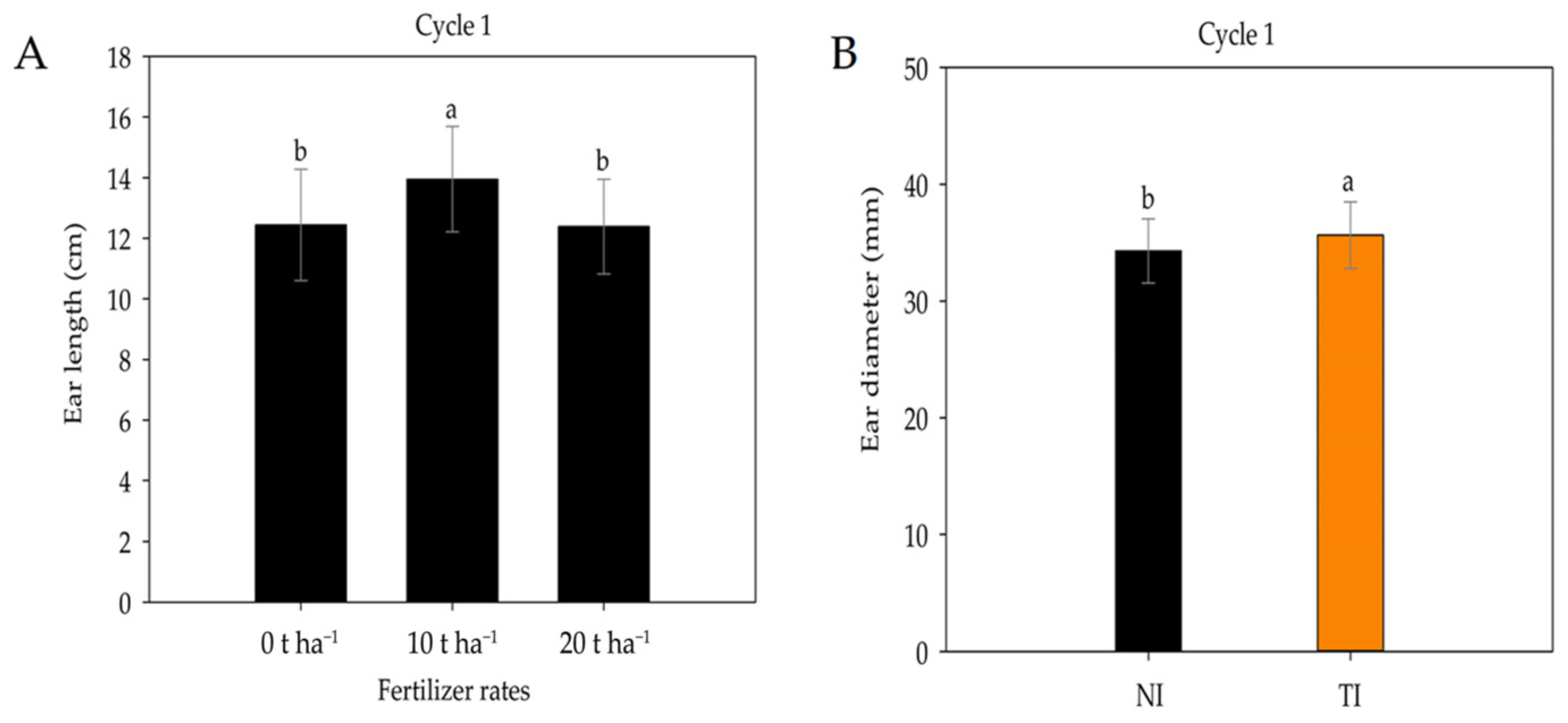

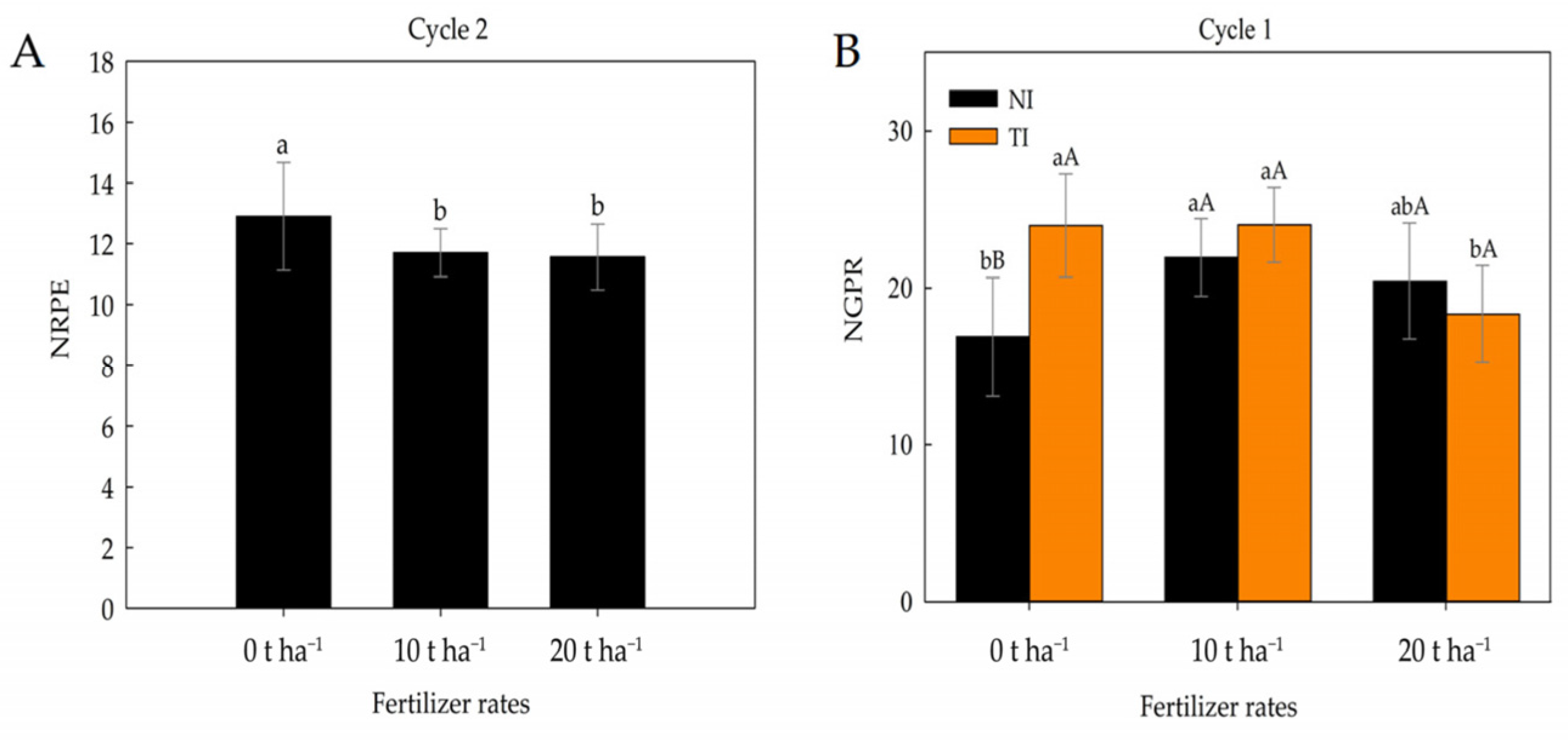

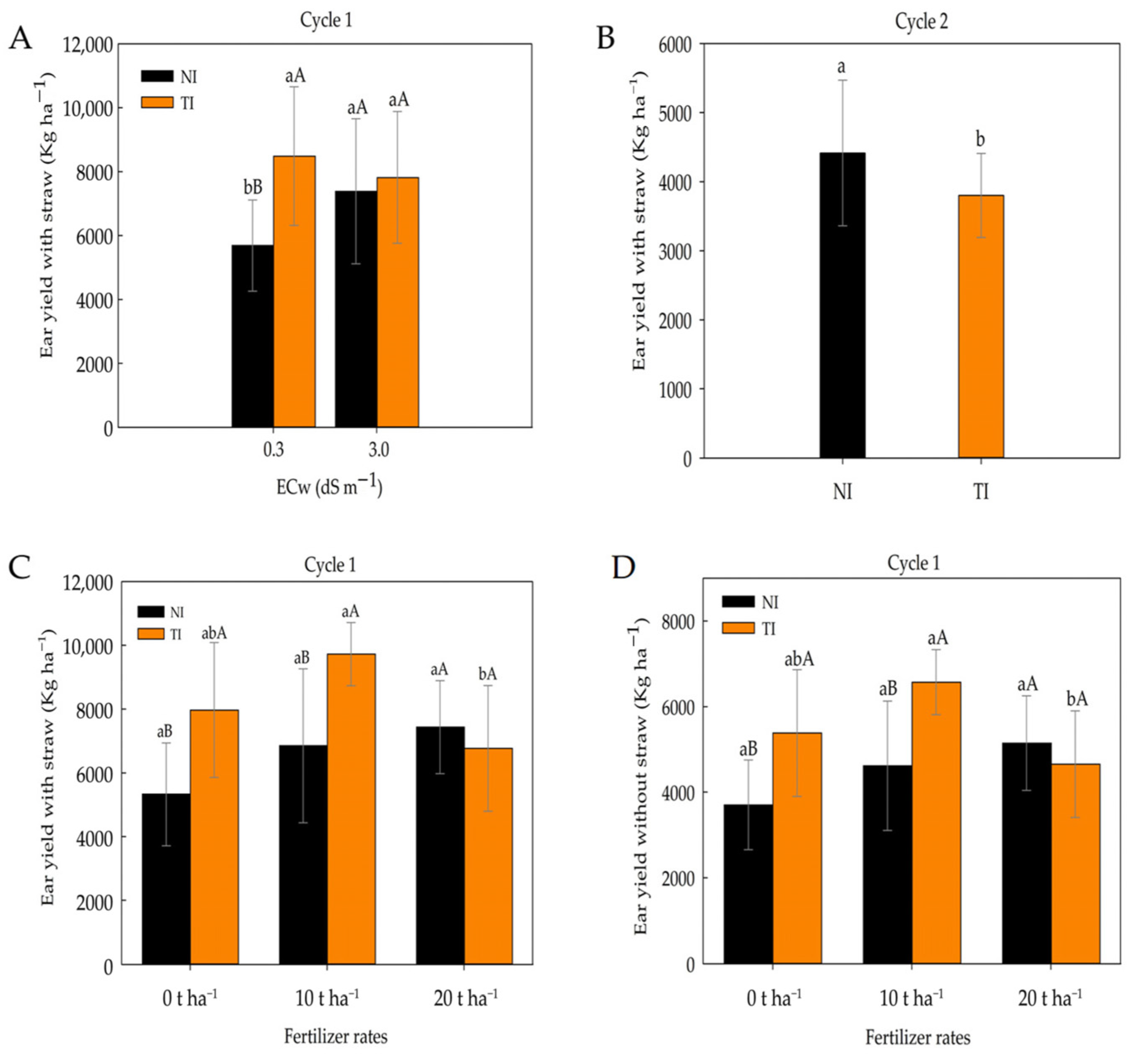

2. Results

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

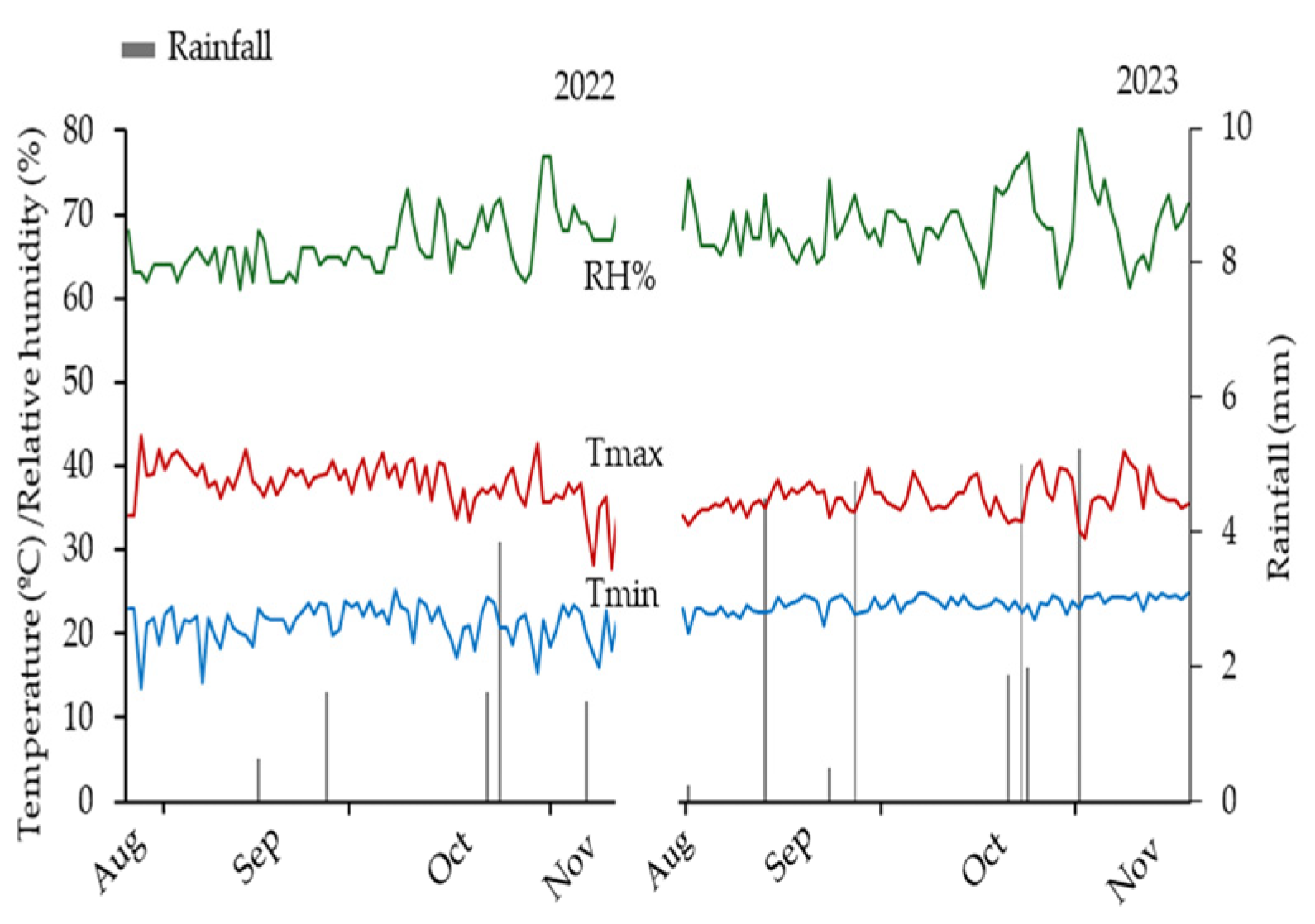

4.1. Study Area

4.2. Experimental Design

4.3. Irrigation Management

- ETc—crop evapotranspiration, in mm day−1;

- ECA—evaporation measured in the class A pan, in mm/day−1;

- Kp—class A pan coefficient, dimensionless;

- Kc—crop coefficient, dimensionless.

- It—irrigation time (min);

- ETc—crop evapotranspiration for the period (mm);

- Sd—spacing between emitters (m);

- Sl—lateral spacing (m);

- Af—application efficiency (0.92);

- q—flow rate (L h−1).

4.4. Experiment Conduction

4.5. Inoculant and Fertilizer Strategy

4.6. Analysed Atributes

4.6.1. Plant Growth

4.6.2. Gas Exchange and SPAD Index

4.6.3. Crop Yield

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ribeiro, B.S.M.R.; Zanon, A.J.; Streck, N.A.; Friedrich, E.D.; Pilecco, I.B.; Alves, A.F.; Puntel, S.; Sarmento, L.F.V.; Streck, I.L.; Inkliman, V.B.; et al. Ecofisiologia do Milho Visando Altas Produtividades. SN Publisher: Santa Maria, RS, Brasil, 2020; p. 230. [Google Scholar]

- Arruda, F.P.; Matos, M.H.M.; Cruz, A.L.F.; Farias, E.R. Indicadores de produção de cultivares de milho verde em diferentes densidades de população. Rev. Caatinga 2022, 35, 331–339. [Google Scholar]

- Park, H.J.; Kim, W.Y.; Yun, D.J. A New Insight of Salt Stress Signalingin Plant. Mol. Cells 2016, 39, 447–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, J.; Xue, X.; Huang, C.; You, Q.; Guo, P.; Yang, R.; Da, F.; Duan, Z.W.; Peng, F. Effect of salinization on soil properties and mechanisms beneficial to microorganisms in salinized soil remediation—A review. Res. Cold Arid Reg. 2024, 16, 121–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khondoker, M.; Mandal, S.; Gurav, R.; Hwang, S. Freshwater shortage, salinity increase, and global food production: A need for sustainable irrigation water desalination—A scoping review. Earth 2023, 4, 223–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, M.; Wang, H.; Fan, J.; Wang, X.; Sun, X.; Yang, L.; Zhang, S.; Xiang, Y.; Zhang, F. Crop yield and water productivity under salty water irrigation: A global meta-analysis. Agric. Water Manag. 2021, 256, 107105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.; Liu, X.; Zhang, L.; Zhou, W. Drip irrigation in agricultural saline-alkali land controls soil salinity and improves crop yield: Evidence from a global meta-analysis. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 880, 163226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, J.R.I.; Souza, R.M.S.; Santos, W.A.; Almeida, A.Q.; Souza, E.S.; Antonino, A.C.D. Aplicação do método de Budyko para modelagem do balanço hídrico no semiárido brasileiro. Sci. Plena 2017, 13, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakeri, E.; Emam, Y.; Pessarakli, M.; Tabatabaei, S.A. Biochemical traits associated with growing sorghum genotypes with saline water in the field. J. Plant Nutr. 2020, 43, 1136–1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, H.C.; Sousa, G.G.; Viana, T.V.A.; Pereira, A.P.A.; Lessa, C.I.N.; Souza, M.V.P.; Guilherme, J.M.S.; Goes, G.F.; Alves, F.G.S.; Gomes, S.P.; et al. Bacillus aryabhattai Mitigates the Effects of Salt and Water Stress on the Agronomic Performance of Maize under an Agroecological System. Agriculture 2023, 13, 1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayers, R.S.; Westcot, D.W. A qualidade da Água na Agricultura. Campina Grande; UFPB: João Pessoa, Brazil; Estudos FAO (Irrigação e Drenagem): Rome, Italy, 1991; Volume 29, 218p. [Google Scholar]

- Lacerda, F.H.; Pereira, F.H.; Silva, F.D.A.D.; Queiroga, F.M.D.; Brito, M.E.; Medeiros, J.E.D.; Dias, M.D.S. Fisiologia e crescimento do milho sob salinidade da água e aplicação de peróxido de hidrogênio. Rev. Bras. Eng. Agríc. Ambient. 2022, 26, 771–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, V.D.S.; Sousa, G.G.D.; Soares, S.D.C.; Leite, K.N.; Ceita, E.D.; Sousa, J.T.M.D. Trocas gasosas e conteúdo mineral de culturas de milho irrigadas com água salina. Rev. Ceres 2021, 68, 453–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freire, M.H.D.C.; Viana, T.V.D.A.; Sousa, G.G.D.; Azevedo, B.M.D.; Sousa, H.C.; Goes, G.F.; Lessa, C.I.N.; Silva, F.D. Organic fertilizer and salt stress on the agronomic performance of maize crop. Rev. Bras. Eng. Agríc. Ambient. 2022, 26, 848–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nascimento, L.S.; Silva, F.D.B.; Nogueira, R.S.; Cia, S.N.; Sousa, H.M.A.; Sousa, G.G.; Sousa, H.C.; Moraes, J.G.L.; Ribeiro, J.F.; Goes, G.F.; et al. Organic fertilization strategies and use of Trichoderma in the agronomic performance of green maize. Braz. J. Biol. 2025, 85, e287513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlson, J.; Saxena, J.; Basta, N.; Hundal, L.; Busalacchi, D.; Dick, R.P. Application of organic amendments to restore degraded soil: Effects on soil microbial properties. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2015, 187, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, M.V.P.; Sousa, G.G.; Silva Sales, J.R.; Costa Freire, M.H.; Silva, G.L.; Araújo Viana, T.V. Saline water and biofertilizer from bovine and goat manure in the Lima bean crop. Rev. Bras. Cienc. Agrar. 2019, 14, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bettiol, W.; da Silva, J.C.; de Castro, M.L.M.P. Uso atual e perspectivas do Trichoderma no Brasil. Em Trichoderma Uso na Agricultura; Meyer, M.C., Mazaro, S.M., Silva, J.C., Eds.; Embrapa: Brasília, Brasil, 2019; pp. 21–43. [Google Scholar]

- Contreras-Cornejo, H.A.; Schmoll, M.; Esquivel-Ayala, B.A.; González-Esquivel, C.E.; Rocha-Ramírez, V.; Larsen, J. Mechanisms for plant growth promotion activated by Trichoderma in natural and managed terrestrial ecosystem. Microbiol. Res. 2024, 281, 127621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asghar, W.; Kataoka, R. Effect of co-application of Trichoderma spp. with organic composts on plant growth enhancement, soil enzymes and fungal community in soil. Arch. Microbiol. 2021, 203, 4281–4291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eleduma, A.F.; Aderibigbe, A.T.B.; Obabire, S.O. Effect of cattle manure on the performances of maize (Zea mays L.) grown in forest-savannah transition zone Southwest Nigeria. Int. J. Agric. Sci. Food Technol. 2020, 6, 110–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, J.L.; Ribeiro, E.A.; Oliveira, R.S.; Luz, J.H.S.; Nunes, B.H.D.N.; Oliveira, H.P.; Sarmento, R.A.; Silva, R.R.; Chagas, A.F. Volatile organic compounds produced by Trichoderma sp. Morphophysiologically altered maize growth at initial stages. Aust. J. Crop Sci. 2021, 15, 215–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Wang, Y.; Liu, C.; Chen, F.; Ge, H.; Tian, F.; Yang, T.; Zhang, Y. Trichoderma harzianum mitigates salt stress in cucumber via multiple responses. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2019, 170, 436–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daliakopoulos, I.N.; Apostolakis, A.; Wagner, K.; Deligianni, A.; Koutskoudis, D.; Stamatakis, A.; Tsanis, I.K. Effectiveness of Trichoderma harzianum in soil and yield conservation of tomato crops under saline irrigation. Catena 2019, 175, 144–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collado, M.B.; Aulicino, M.B.; Arturi, M.J.; Molina, M.D.C. Seleção de genótipos de milho com tolerância ao estresse osmótico associado à salinidade. Ciênc. Agrár. 2016, 7, 82–92. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, K.; Manigundan, K.; Amaresan, N. Increase in maize productivity through by Trichoderma harzianum inoculation. J. Basic Microbiol. 2017, 57, 141–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Worlu, C.W.; Nwauzoma, A.B.; Chuku, E.C.; Ajuru, M.G. Comparative effects of Trichoderma species on Growth Parameters and Yield of Zea mays (L.). GPH-Int. J. Biol. Med. Sci. 2022, 5, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, W.; Yuan, W.; Zhang, R.; Xi, X. Cattle manure application and combined straw mulching enhance maize (Zea mays L.) growth and water use for rain-fed cropping system of coastal saline soils. Agriculture 2021, 11, 745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreira, V.O.G.; Assis Júnior, R.N.; Aragão, T.C. Crescimento e fotossíntese do milho cultivado sob estresse salino com esterco e polímero superabsorvente. Irriga 2020, 25, 603–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, E.P.; Silva, J.E.V.C.; Malaquias, M.F.; Ferreira, L.E. Bioinsumos no crescimento e produção de plantas de milho. Rev. Ibero-Am. Cienc. Ambient. 2021, 12, 82–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, X.; Yang, Y.; Guan, P.; Geng, L.; Ma, L.; Di, H.; Liu, W.; Li, B. Remediation of organic amendments on soil salinization: Focusing on the relationship between soil salts and microbial communities. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2022, 239, 113616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steffen, G.P.K.; Tomazzi, D.J.; Steffen, R.B.; Gabe, N.L.; Silva, R.F.; Mortari, J.L.M.; Maldaner, J.; Santos, G.F.P. Increase in maize productivity through by Trichoderma Harzianum inoculation. Braz. J. Dev. 2021, 7, 4455–4468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.; Yang, H.; Hu, J.; Li, H.; Zhao, Z.; Wu, Y.; Li, J.; Zhou, Y.; Yang, K.; Yang, H. Trichoderma harzianum inoculation promotes sweet sorghum growth in the saline soil by modulating rhizosphere available nutrients and bacterial Community. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1258131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araújo, T.B.; Schuelter, A.R.; Souza, I.R.P.; Coelho, S.R.M.; Christ, D. Growth promotion in maize inoculated with Trichoderma harzianum. Braz. J. Maize Sorghum. 2023, 22, e1269. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Z.; Li, J.L.; Liu, L.N.; Xie, Q.; Sui, N. Photosynthetic Regulation Under Salt Stress and Salt-Tolerance Mechanism of Sweet Sorghum. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 10, 1722. [Google Scholar]

- Silva, F.D.D.A.; Pereira, F.H.F.; Júnior, J.E.C.; Nobrega, J.S.; Santos Dias, M. Aplicação foliar de prolina no crescimento e fisiologia do milho verde cultivado em solo salinizado. Colloq. Agrar. 2020, 16, 23–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acosta-Motos, J.R.; Penella, C.; Hernández, J.A.; Díaz-Vivancos, P.; Sánchez-Blanco, M.J.; Navarro, J.M.; Gómez-Bellote, M.J.; Barba-Espín, G. Towards a sustainable agriculture: Strategies involving phytoprotectants against salt stress. Agronomy 2020, 10, 194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doni, F.; Isahak, A.; Zain, C.R.C.M.; Wan Yusoff, W.M. Physiological and growth response of rice plants (Oryza sativa L.) to Trichoderma spp. inoculants. AMB Express 2014, 4, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estévez-Geffriaud, V.; Vicente, R.; Vergara-Díaz, O.; Narváez Reinaldo, J.J.; Trillas, M.I. Application of Trichoderma asperellum T34 on maize (Zea mays) seeds protects against drought stress. Plants 2020, 252, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vennam, R.R.; Bheemanahalli, R.; Reddy, K.R.; Dhillon, J.; Zhang, X.; Adeli, A. Early-season maize responses to salt stress: Morpho-physiological, leaf reflectance, and mineral composition. J. Agric. Food Res. 2024, 15, 100994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Q.; Gu, S.; Kang, S.; Du, T.; Tong, L.; Wood, J.D.; Ding, R. Mild water and salt stress improve water use efficiency by decreasing stomatal conductance via osmotic adjustment in field maize. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 805, 150364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yasmeen, R.; Siddiqui, Z.S. Ameliorative effects of Trichoderma harzianum on monocot crops under hydroponic saline environment. Acta Physiol. Plant. 2018, 40, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, J.; Wang, Y.F.; Liu, Z.H.; Li, Z.T.; Yang, K.J. Trichoderma asperellum alleviates the effects of saline–alkaline stress on maize seedlings via the regulation of photosynthesis and nitrogen metabolism. Plant Growth Regul. 2018, 85, 363–374. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, L.; Xu, Z.; Zhou, X.Q. The application of Trichoderma species enhances plant resistance to salinity: A bibliometric analysis and meta-analysis. J. Soils Sediments 2023, 23, 2641–2653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikram, M.; Ali, N.; Jan, G.; Iqbal, A.; Hamayun, M.; Gul Jan, F. Trichoderma reesei improved the nutritional status of wheat crop under salinity stress. J. Plant Interact. 2019, 14, 590–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reina, E.; Reina, E.; Afférri, F.S.; Carvalho, E.V.; Dotto, M.A.; Peluzio, J.M. Efeito de doses de esterco bovino na linha de semeadura na produtividade de milho. Rev. Verde Agroecol. Desenvolv. Sustent. 2010, 5, 158–164. [Google Scholar]

- Santos, P.R.; Silva Costa, K.D.; Carvalho, I.D.E.; Silva, J.P.; Ferreira, P.V. Desempenho de genótipos de milho, Zea mays l., submetidos a dois tipos de adubação. Rev. Verde de Agro. e Desenv. Sust. 2014, 9, 210–215. [Google Scholar]

- Guerra, A.M.N.M.; Ferreira, J.B.A.; Vieira, T.S.; Franco, J.R.; Costa, A.C.M.; Tavares, P.R.F. Avaliação da produtividade de grãos e de biomassa em dois híbridos de milho submetidos à duas condições de adubação no município de Santarém-PA. Rev. Bras. de Agro. Sust. 2017, 7, 20–27. [Google Scholar]

- Mei, H.; Li, T.; Wu, H.; Xia, Y.; Huang, Q.; Liu, D.; Shen, Q. Transcriptomic Profiling Reveals Key Gene in Trichoderma guizhouense NJAU4742 Enhancing Tomato Tolerance Under Saline Conditions. Agriculture 2025, 15, 610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syamsiyah, J.; Herdiansyah, G.; Hartati, S. Use of Trichoderma as an Effort to Increase Growth and Productivity of Maize Plants. Série de conferências do IOP. Earth Environ. Sci. 2023, 1165, 012020. [Google Scholar]

- Alvares, C.A.; Stape, J.L.; Sentelhas, P.C.; Moraes Gonçalves, J.L.; Sparovek, G. Köppen’s climate classification map for Brazil. Meteorol. Z. 2013, 22, 711–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, P.C.; Donagema, G.K.; Fontana, A.; Teixeira, W.G. Manual de Métodos de Análise do Solo, 3rd ed.; Embrapa: Brasília, Brasil, 2017; p. 573. [Google Scholar]

- Santos, H.G.; Jacomine, P.K.T.; Anjos, L.H.C.; Oliveira, V.A.; Lumbreras, J.F.; Coelho, M.R.; Almeida, J.A.; Araujo Filho, J.C.; Oliveira, J.B.; Cunha, T.J.F. Sistema Brasileiro de Classificação de Solos, 5th ed.; Embrapa Informação Tecnológica: Brasília, Brasil, 2018; p. 356. [Google Scholar]

- Keller, J.; Karmeli, D. Trickle Irrigation Design; Rain Bird Sprinkler Manufacturing Corporation: Glendora, CA, USA, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Souza, L.S.B.; Moura, M.S.B.; Sediyama, G.C.; Silva, T.G.F. Requerimento hídrico e coeficiente de cultura do milho e feijão-caupi em sistemas exclusivos e consorciados. Rev. Caatinga 2015, 28, 151–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernardo, S.; Mantovani, E.C.; Silva, D.D.; Soares, A.A. Manual de Irrigação, 9th ed.; UFV: Viçosa, Brasil, 2019; p. 545. [Google Scholar]

- Medeiros, J.F. Qualidade da Água de Irrigação Utilizada nas Propriedades Assistidas pelo “GAT” nos Estados do RN, PB, CE e Avaliação da Salinidade dos Solos. Master’s Thesis (Mestrado em Engenharia Agrícola: Área de Concentração Irrigação e Drenagem), Universidade Federal de Campina Grande, Campina Grande, PB, USA, November 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes, V.L.B.; Aquino, A.B.; Aquino, B.F. Recomendações de Adubação e Calagem para o Estado do Ceará; UFC: Fortaleza, Brasil, 1993; p. 248. [Google Scholar]

- Richards, L.A. Diagnosis and Improvement of Saline and Alkali Soils. In USDA Agriculture Handbook; US Government Printing Office: Washington, DC, USA, 1954; p. 60. [Google Scholar]

- Nascimento, L.S. Uso do Trichoderma e da adubação orgânica no cultivo do milho verde. Trabalho de conclusão de curso. Curso de Agronomia, Instituto de Desenvolvimento Rural (IDR). Universidade da Integração Internacional da Lusofonia Afro-Brasileira. Redenção-CE, 2022. Available online: https://repositorio.unilab.edu.br/jspui/handle/123456789/3866 (accessed on 8 January 2025).

- Pereira, A.R. Estimativa da área foliar em milharal. Bragantia 1987, 46, 147–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritchie, S.W.; Hanway, J.J.; Benson, G.O. How a Corn Plant Develops; Iowa States University of Science and Technology: Ames, IA, USA, 1993; p. 26. [Google Scholar]

- Silva, F.D.A.S.; de Azevedo, C.A.V. The Assistat Software Version 7.7 and its use in the analysis of experimental data. Afr. J. Agric. Res. 2016, 11, 3733–3740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Source of Variation | DF | Mean | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PH | LA | SD | NL | PH | LA | SD | NL | ||

| Cycle 1 | Cycle 2 | ||||||||

| Blocks | 3 | 67.26 ns | 653.41 ns | 1.79 ns | 0.57 ns | 22.58 ns | 1906.40 ns | 7.74 ns | 1.13 ns |

| Water electrical conductivity (ECw) | 1 | 1710.04 * | 2271.17 ns | 0.35 ns | 0.33 ns | 630.75 * | 1566.66 ns | 66.43 * | 2.75 ns |

| Error | 3 | 61.21 | 471.97 | 5.03 | 0.47 | 42.36 | 4651.07 | 6.010 | 0.53 |

| Fertilizer rates (FR) | 2 | 2691.70 ** | 21,029.08 ** | 9.58 ns | 1.00 ns | 1150.40 ** | 544.33 ns | 9.97 * | 0.14 ns |

| Error | 12 | 147.72 | 1022.33 | 5.00 | 0.80 | 30.35 | 2740.89 | 2.20 | 0.52 |

| Inoculation (I) | 1 | 0.25 ns | 4939.16 ns | 9.12 ns | 0.33 ns | 98.61 ns | 8926.93 ns | 55.66 ** | 0.04 ns |

| Error | 18 | 80.79 | 1792.39 | 2.63 | 0.39 | 64.91 | 2876.39 | 4.54 | 0.88 |

| ECw x FR | 2 | 365.10 ns | 4374.69 * | 8.11 ns | 1.03 ns | 48.26 ns | 10,645.36 ns | 5.15 ns | 0.09 ns |

| ECw x I | 1 | 3.79 | 16,061.31 ** | 1.74 ns | 0.02 ns | 1552.68 ** | 46,626.97 ** | 0.14 ns | 0.63 ns |

| FE x I | 2 | 480.19 * | 13,735.02 ** | 22.81 ** | 2.22 * | 295.03 * | 16,325.54 * | 1.22 ns | 0.48 ns |

| ECw x FR x I | 2 | 13.32 ns | 426.72 ns | 1.37 ns | 0.19 ns | 1487.18 ** | 5575.24 ns | 22.63 * | 0.13 ns |

| CV (%)-ECw | 8.02 | 6.29 | 16.7 | 8.35 | 9.06 | 15.16 | 23.04 | 8.37 | |

| CV (%)-FR | 12.46 | 9.26 | 16.67 | 10.91 | 7.67 | 11.63 | 13.97 | 8.35 | |

| CV (%)-I | 9.22 | 12.26 | 12.09 | 7.61 | 11.22 | 11.92 | 20.02 | 10.8 | |

| Source of Variation | DF | Mean | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | E | gs | SPAD | A | E | gs | SPAD | ||

| Cycle 1 | Cycle 2 | ||||||||

| Blocks | 3 | 4.40 ns | 5.76 ** | 0.45 ns | 6.23 ns | 9.56 ns | 1.00 ns | 0.36 ns | 10.23 ns |

| Water electrical conductivity (ECw) | 1 | 25.30 * | 20.81 ** | 0.05 ns | 259.93 ** | 142.07 ns | 0.23 ns | 36.16 * | 39.42 ns |

| Error | 3 | 1.76 | 0.17 | 0.15 | 4.170 | 20.89 | 1.35 | 1.07 | 37.42 |

| Fertilizer rates (FR) | 2 | 15.54 ns | 0.24 ns | 0.86 ** | 103.58 ** | 7.34 ns | 0.01 ns | 0.00 * | 6.44 ns |

| Error | 12 | 4.75 | 0.75 | 0.05 | 5.29 | 10.22 | 0.39 | 1.03 | 11.83 |

| Inoculation (I) | 1 | 114.54 ** | 2.28 * | 0.21 ns | 344.00 ** | 10.36 ns | 0.36 ns | 0.43 ns | 2.38 ns |

| Error | 18 | 10.080 | 0.50 | 0.06 | 13.23 | 5.20 | 0.18 | 0.72 | 8.88 |

| ECw x FR | 2 | 16.05 ns | 0.01 * | 0.029 ns | 55.36 ** | 6.33 ns | 0.10 ns | 0.13 ns | 4.57 ns |

| ECw x I | 1 | 1.53 ns | 0.14 ns | 0.59 ** | 15.98 ns | 31.04 * | 0.10 ns | 0.39 ns | 2.85 ns |

| F x I | 2 | 8.32 ns | 0.25 ns | 1.31 ** | 169.07 ** | 6.15 ns | 0.09 ns | 9.95 ** | 0.10 ns |

| ECw x FR x I | 2 | 33.88 ns | 1.27 ns | 1.31 * | 104.90 ** | 2.67 ns | 0.05 ns | 11.27 ** | 16.73 ns |

| CV (%)-ECw | 5.16 | 6.6 | 38.02 | 6.8 | 21.94 | 33.07 | 38.73 | 24.47 | |

| CV (%)-FR | 8.46 | 13.73 | 21.93 | 7.66 | 15.35 | 17.75 | 29.67 | 13.76 | |

| CV (%)-I | 12.32 | 11.21 | 24.75 | 12.1 | 10.9 | 12.14 | 27.69 | 11.92 | |

| Cycle 1 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Source of Variation | DF | Mean | |||||

| ED | EL | NRPE | NGPR | EYWH | EYH | ||

| Blocks | 3 | 0.81 ns | 1.51 ns | 1.29 ns | 8.99 ns | 474,952.30 ns | 1,622,053.66 ns |

| Water electrical conductivity (ECw) | 1 | 50.98 ns | 0.005 ns | 3.03 ns | 40.60 ns | 2,115,040.98 ns | 3,170,344.29 ns |

| Error | 3 | 7.05 | 4.93 | 0.89 | 23.01 | 1,351,729.72 | 2,370,675.00 |

| Fertilizer (F) | 2 | 17.05 ns | 12.64 * | 1.64 ns | 54.67 * | 4,570,054.97 ns | 11,474,622.9 ns |

| Error | 12 | 10.5 | 2.57 | 0.98 | 9.01 | 2,101,188.29 | 4,247,645.59 |

| Inoculation (I) | 1 | 24.65 * | 3.40 ns | 0.08 ns | 66.58 * | 13,151,278.20 ** | 31,328,848.00 ** |

| Error | 18 | 5.410 | 3.23 | 0.51 | 11.86 | 1,546,104.74 | 3,599,564.47 |

| ECw x F | 2 | 0.86 ns | 2.12 ns | 0.01 ns | 0.82 ns | 943,167.51 ns | 2,030,409.7 ns |

| ECw x I | 1 | 9.78 ns | 5.29 ns | 0.45 ns | 9.39 ns | 6,260,221.05 ns | 16,901,545.17 * |

| F x I | 2 | 13.94 ns | 8.93 ns | 0.12 ns | 84.64 ** | 7,166,876.59 * | 15,687,688.93 * |

| ECw x F x I | 2 | 1.26 ns | 1.20 ns | 0.98 ns | 5.93 ns | 1,356,593.65 ns | 3,846,194.34 ns |

| CV (%)-ECw | 7.61 | 17.19 | 7.81 | 22.91 | 23.19 | 20.96 | |

| CV (%)-F | 9.28 | 12.4 | 8.22 | 14.34 | 28.91 | 28.05 | |

| CV (%)-I | 6.66 | 13.9 | 5.91 | 16.45 | 24.8 | 25.83 | |

| Cycle 2 | |||||||

| Source of Variation | DF | Mean | |||||

| ED | EL | NRPE | NGPR | EYWH | EYH | ||

| Blocks | 3 | 5.73 ns | 8.43 ns | 0.84 ns | 3.76 ns | 607,497.91 ns | 298,367.42 ns |

| Water electrical conductivity (ECw) | 1 | 0.00 ns | 4.74 ns | 0.001 ns | 0.50 ns | 511,404.72 ns | 2,656,205.87 ns |

| Error | 3 | 0.78 | 4.32 | 0.3 | 10.63 | 283,766.43 | 454,567.73 |

| Fertilizer (F) | 2 | 3.25 ns | 0.52 ns | 8.64 * | 1.20 ns | 459,253.10 ns | 356,415.74 ns |

| Error | 12 | 2.18 | 2.29 | 1.56 | 3.86 | 276,397.56 | 709,774.58 |

| Inoculation (I) | 1 | 1.70 ns | 6.02 ns | 3.91 ns | 2.50 ns | 1,290,267.48 ns | 4,516,546.50 * |

| Error | 18 | 5.73 | 1.91 | 1.92 | 4.97 | 597,237.75 | 798,665.38 |

| ECw x F | 2 | 3.84 ns | 1.28 ns | 2.66 ns | 0.82 ns | 205,430.39 ns | 243,914.55 ns |

| ECw x I | 1 | 0.46 ns | 1.24 ns | 3.39 ns | 0.001 ns | 2942.85 ns | 114,488.18 ns |

| F x I | 2 | 5.11 ns | 0.09 ns | 2.33 ns | 1.00 ns | 573,823.21 ns | 1,026,472.65 ns |

| ECw x F x I | 2 | 2.080 ns | 1.51 ns | 2.40 ns | 4.54 ns | 1,169,818.44 ns | 2,140,985.88 ns |

| CV (%)-ECw | 2.75 | 20.24 | 4.59 | 23.36 | 18.09 | 16.41 | |

| CV (%)-F | 4.58 | 14.74 | 10.37 | 14.08 | 17.86 | 20.51 | |

| CV (%)-I | 7.43 | 13.48 | 11.5 | 15.99 | 26.25 | 21.76 | |

| Attributes | Seasons | |

|---|---|---|

| 2022 | 2023 | |

| ECe (dS m−1) | 0.76 | 0.56 |

| pH (H2O) | 5.6 | 6.4 |

| OM (g kg−1) | 11.59 | 16.07 |

| N (g kg−1) | 0.71 | 0.99 |

| P (mg dm−3) | 20 | 21 |

| K+ (cmolc dm−3) | 0.17 | 0.19 |

| Na+ (cmolc dm−3) | 0.07 | 0.12 |

| Ca2+ (cmolc dm−3) | 3.2 | 5.9 |

| Mg2+ (cmolc dm−3) | 2.6 | 0.7 |

| H+ + Al3+ (cmolc dm−3) | 2.15 | 1.82 |

| Al3+ (cmolc dm−3) | 0.35 | 0.05 |

| SB (cmolc dm−3) | 6.04 | 6.9 |

| CEC (cmolc dm−3) | 8.19 | 8.72 |

| V (%) | 74 | 79 |

| m (%) | 5 | 1 |

| ESP (%) | 0.85 | 1.38 |

| Sand (%) | 507 | 358 |

| Silt (%) | 133 | 189 |

| Clay (%) | 77 | 132 |

| Ca2+ | Mg2+ | K+ | Na+ | Cl− | HCO3- | pH | ECw | SAR | Class |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (mmolc L−1) | (mmolc L−1) | _ | (dS m−1) | _ | _ | ||||

| 8.1 | 2.5 | 0.1 | 25.8 | 33.8 | 2.4 | 6.5 | 3.0 | 11.21 | C4S3 |

| Ca2+ | Mg2+ | K+ | Na+ | Cl- | HCO3- | pH | ECw | SAR | Class |

| (mmolc L−1) | (mmolc L−1) | _ | (dS m−1) | _ | _ | ||||

| 1.2 | 1.6 | 0.1 | 0.7 | 3.1 | 0.4 | 7.2 | 0.34 | 0.42 | C2S1 |

| Cattle Manure | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | P | K | Ca | Mg | Fe | Cu | Zn |

| -----------------------------------------------------g·kg−1------------------------------------------------- | |||||||

| 19.60 | 4.95 | 0.67 | 1.38 | 3.85 | 0.55 | 0.04 | 0.10 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Souza, M.V.P.d.; Sousa, G.G.d.; Pereira, A.P.d.A.; Sousa, H.C.; Garcia, K.G.V.; Sousa, L.V.d.; Silva, G.F.d.; Silva, Ê.F.d.F.e.; Silva, T.G.F.d.; Silva, A.O.d. Cattle Manure Fertilizer and Biostimulant Trichoderma Application to Mitigate Salinity Stress in Green Maize Under an Agroecological System in the Brazilian Semiarid Region. Plants 2025, 14, 3643. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14233643

Souza MVPd, Sousa GGd, Pereira APdA, Sousa HC, Garcia KGV, Sousa LVd, Silva GFd, Silva ÊFdFe, Silva TGFd, Silva AOd. Cattle Manure Fertilizer and Biostimulant Trichoderma Application to Mitigate Salinity Stress in Green Maize Under an Agroecological System in the Brazilian Semiarid Region. Plants. 2025; 14(23):3643. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14233643

Chicago/Turabian StyleSouza, Maria Vanessa Pires de, Geocleber Gomes de Sousa, Arthur Prudêncio de Araujo Pereira, Henderson Castelo Sousa, Kaio Gráculo Vieira Garcia, Leonardo Vieira de Sousa, Gerônimo Ferreira da Silva, Ênio Farias de França e Silva, Thieres George Freire da Silva, and Alexsandro Oliveira da Silva. 2025. "Cattle Manure Fertilizer and Biostimulant Trichoderma Application to Mitigate Salinity Stress in Green Maize Under an Agroecological System in the Brazilian Semiarid Region" Plants 14, no. 23: 3643. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14233643

APA StyleSouza, M. V. P. d., Sousa, G. G. d., Pereira, A. P. d. A., Sousa, H. C., Garcia, K. G. V., Sousa, L. V. d., Silva, G. F. d., Silva, Ê. F. d. F. e., Silva, T. G. F. d., & Silva, A. O. d. (2025). Cattle Manure Fertilizer and Biostimulant Trichoderma Application to Mitigate Salinity Stress in Green Maize Under an Agroecological System in the Brazilian Semiarid Region. Plants, 14(23), 3643. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14233643