Abstract

Foxtail millet (Setaria italica L.) is an important crop in northern China’s arid and semi-arid regions. Frequent spring droughts and limited irrigation facilities often cause poor seed germination due to insufficient soil moisture, threatening food security. The irrigation-sowing technique, which creates a localized moist microenvironment around seeds, effectively addresses this issue. However, this technique has been poorly studied, and its effects on foxtail millet seed germination remain unclear. To address this, field experiments were conducted using a two-factor split-plot design, with three drought levels and five irrigation gradients. The results showed that irrigation-sowing increased soil moisture, promoted root–shoot growth coordination, and improved germination characteristics. Transcriptome analysis of seeds under moderate drought compared the optimal irrigation treatment (13.5 m3·hm−2) with the non-irrigated control (0 m3·hm−2), identifying 2169 differentially expressed genes. Seeds receiving irrigation exhibited higher transcript abundance in pathways related to carbohydrate metabolism, energy production, secondary metabolism, and hormone signaling. Physiological measurements further showed increased α/β-amylase activity, while starch, sucrose, and cellulose content decreased. Glycolytic enzyme activity was enhanced, and ATP content increased by 125%. Additionally, phenylpropanoid metabolism was promoted, and proanthocyanidin accumulation increased by 11.5%. Hormone analysis showed that the contents of IAA and GA increased as germination progressed by 29.09% and 54.70%, respectively, while ABA content decreased. Overall, irrigation-sowing serves as an upstream moisture signal that reshapes metabolic and hormonal states associated with improved germination performance.

1. Introduction

Foxtail millet (Setaria italica L.) is an important crop in the arid and semi-arid regions of northern China, with a cultivation history of approximately 8700 years [1]. Its grains and stems serve both as food and fodder, making it an essential crop in dryland agriculture in northern China [2,3]. Foxtail millet primarily grows in arid regions such as the Loess Plateau and hilly areas, where natural precipitation and ample sunlight align well with its drought-tolerant and light-demanding growth characteristics. However, with the intensification of climate change and the increasing issue of water scarcity, frequent spring droughts in northern regions often result in insufficient soil moisture, causing low seedling emergence rate and threatening food security. At the same time, these regions lack irrigation infrastructure, and traditional surface or furrow irrigation is impractical due to the instability of water sources. Advanced systems like drip and sprinkler irrigation, due to their high cost and technical requirements, are difficult to implement in rural areas [4]. Although foxtail millet is a drought-tolerant cereal crop, its seed germination and seedling growth are highly sensitive to water availability, and water deficit often leads to poor germination and reduced seedling vigor [5]. Studies show that the moisture content in the 0–20 cm topsoil is critical for foxtail millet’s germination and early growth. When soil moisture falls below the germination threshold, foxtail millet seeds cannot absorb enough water, leading to delayed or failed germination [6]. Even if some seeds germinate, the rapid depletion of soil moisture can cause seedling desiccation, resulting in sparse and uneven emergence in the field, ultimately leading to insufficient seedling populations and severe yield reductions. Therefore, improving seed germination and seedling vigor is crucial for increasing yield. Once seedlings emerge, foxtail millet can usually rely on natural rainfall for the subsequent growth and yield formation.

To address this challenge, farmers in China have developed irrigation-sowing, a technique that involves applying water around the seeds during sowing to create a localized moist environment that meets the water requirements for early germination, ensuring full emergence [7,8,9,10]. Unlike traditional large-scale irrigation methods, irrigation-sowing focuses on precision irrigation, preventing water wastage and offering a high-efficiency, water-saving alternative [4]. The 2024 Corn Yield Increase Manual by the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs of the People’s Republic of China that irrigation-sowing in Northeast China increases seedling emergence by more than 30% [11], significantly improving emergence uniformity and yield. However, while the technique has shown notable success in other crops like maize [7,8,9,10], its effects on foxtail millet seed germination, especially at the physiological and molecular levels, remain poorly understood.

Water is essential for seed germination, which involves sequential physiological stages of water uptake, metabolic activation, and mobilization of stored reserves for energy production [6,12]. Drought disrupts this process by reducing seed water absorption, leading to lower germination rate and seedling vigor [13]. Drought stress delays water uptake and chromatin activation, which consequently reduces amylase activity and slows starch hydrolysis into soluble sugars, thereby limiting energy availability during germination [12,13,14,15,16,17]. At the metabolic level, drought disturbs the coordination among glycolysis (EMP), the tricarboxylic acid cycle (TCA), and the pentose phosphate pathway (PPP), reducing ATP and NADPH generation and ultimately weakening energy metabolism [18,19]. Meanwhile, the activation of the phenylpropanoid pathway under drought leads to the accumulation of flavonoids, anthocyanins, and lignins that strengthen cell walls and enhance antioxidant capacity [20,21,22], but excessive deposition may hinder cell expansion and radicle emergence.

Hormonal regulation further modulates these drought responses. Drought elevates abscisic acid (ABA) and suppresses gibberellin (GA) synthesis, increasing the ABA/GA ratio and inhibiting germination through the ABI5 and DELLA pathways [23,24,25]. Ethylene can alleviate ABA-induced inhibition by promoting seed coat rupture [26,27], whereas jasmonic acid (JA) and auxin (IAA) can cooperate with ABA under stress conditions such as drought to enhance dormancy maintenance via the ARF10/ARF16–JAZ–ABI5 regulatory module, while the oxylipin OPDA also acts synergistically with ABA to inhibit germination [28,29,30]. In contrast, brassinosteroids (BRs) and cytokinins (CTKs) cooperate with GA to stimulate energy metabolism, cell division, and elongation during seed germination and early seedling growth, although their levels decline under drought stress [31,32,33,34]. Collectively, drought exerts a multi-level inhibitory effect on seed germination by impairing water uptake, disturbing energy and secondary metabolism, and reshaping hormonal homeostasis.

In recent years, field-scale transcriptomics has attracted increasing attention for its ability to elucidate crop stress-response mechanisms under real agricultural conditions. RNA-Seq technology has been successfully applied to field-based stress studies in crops such as maize and sorghum [35], while foxtail millet, with its small genome, low repetitive sequences, and well-annotated genomic information, exhibits unique potential in this field [36,37]. Although numerous drought-responsive genes and pathways have been reported, the enzymes and transcription factors acting downstream of these genes also play indispensable roles in various biological processes. To cope with drought stress, plants have evolved complex adaptive strategies, including metabolic remodeling, epigenetic plasticity, and gene expression reprogramming [38]. Against this background, the integration of field-scale transcriptomic and physiological analyses provides an effective approach to characterize the coordinated physiological and molecular responses of foxtail millet seeds to irrigating-sowing during germination, thereby offering new insights into the basis of drought-resilient seedling establishment in foxtail millet.

This study uses Jingu 21 as the research material, as it is a representative variety of high-quality foxtail millet in China, and the perennial sowing area is large. While irrigation-sowing has shown significant contributions to water conservation and seedling protection in other crops like maize, systematic research on its effects on small-grain drought-tolerant crops like foxtail millet is limited, particularly regarding its physiological and molecular impacts on early germination. The seed germination process begins with water uptake, followed by chromatin remodeling that activates transcription and metabolism for energy production [14,15,16]. These molecular and physiological changes are accompanied by the re-establishment of auxin gradients and the spatial activation of metabolism across different cell types and positions within the embryo [12,13,14,15,16,17]. Considering the important roles of carbohydrate mobilization, energy metabolism, secondary metabolite synthesis, and hormone balance in seed germination, we hypothesize that irrigating-sowing may generate more favorable states of carbohydrate mobilization, energy metabolism, secondary metabolite synthesis and hormone balance that are associated with greater germination vigor of foxtail millet seeds. Accordingly, this study aimed to investigate how irrigating-sowing influences carbohydrate mobilization, energy metabolism, secondary metabolite synthesis and hormone-related traits during millet seed germination.

2. Results

2.1. Effect of Irrigating-Sowing on Seed Germination Characteristics in Foxtail Millet

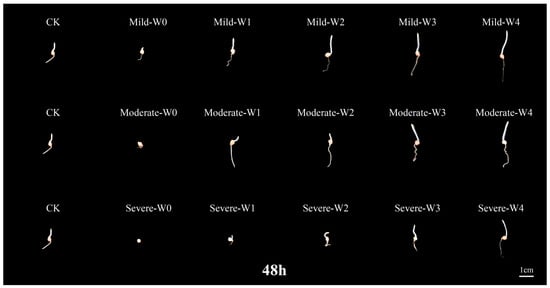

In the 48 h germination period of foxtail millet seeds, seed germination was substantially inhibited as drought severity increased, with inadequate root and shoot development. Under three different drought conditions, increase irrigation improved the seedling growth characteristics, indicating that appropriate irrigation can effectively alleviate the adverse effects of drought stress on seed germination (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Differences in germination morphology of foxtail millet seeds under irrigating-sowing. Drought levels: mild (60% ± 5%), moderate (50% ± 5%), and severe (40% ± 5%) field water holding capacity. Irrigation treatments: W0 (0 m3·hm−2), W1 (4.5 m3·hm−2), W2 (9 m3·hm−2), W3 (13.5 m3·hm−2), and W4 (18 m3·hm−2). CK represents the normal field capacity (70% ± 5%). Seeds were photographed 48 h after sowing, and the scale bar indicates 1 cm.

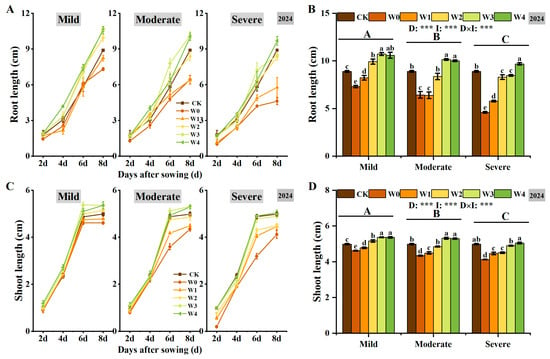

Irrigated sowing significantly influenced root and shoot growth in foxtail millet, with continuous growth observed over time (Figure 2). Root growth was more pronounced than shoot growth (Figure 2A,C), indicating that foxtail millet seeds prioritize root development to enhance water acquisition. Under three different drought conditions, both root and shoot lengths increased with higher irrigation. Under moderate drought, by the 8th day, root length in the W3 increased by 57.74% compared to W0, and shoot length increased by 22.37% (Figure 2B,D). Additionally, higher shoot length was observed on the 6th day, with slower elongation thereafter (Figure 2C), indicating that irrigating-sowing helps promote early rapid shoot elongation.

Figure 2.

Effects of irrigating-sowing on root and shoot growth of foxtail millet. (A,C) Changes in root (A) and shoot (C) length of foxtail millet seedlings at 2, 4, 6, and 8 days after sowing under three drought levels (mild, moderate, and severe) with five irrigation treatments (W0–W4). CK represents the well-watered control (70% ± 5% of field capacity). (B,D) Comparison of root (B) and shoot (D) length on the 8th day under different drought and irrigation treatments. Error bars represent the standard error of the mean (n = 3). Different uppercase letters indicate significant differences among drought levels (p < 0.05), and different lowercase letters indicate significant differences among irrigation treatments within the same drought level (p < 0.05). D, I, and D × I represent the main effects of drought, irrigation, and their interaction, respectively. *, **, and *** indicate significant differences at p < 0.05, p < 0.01, and p < 0.001, respectively.

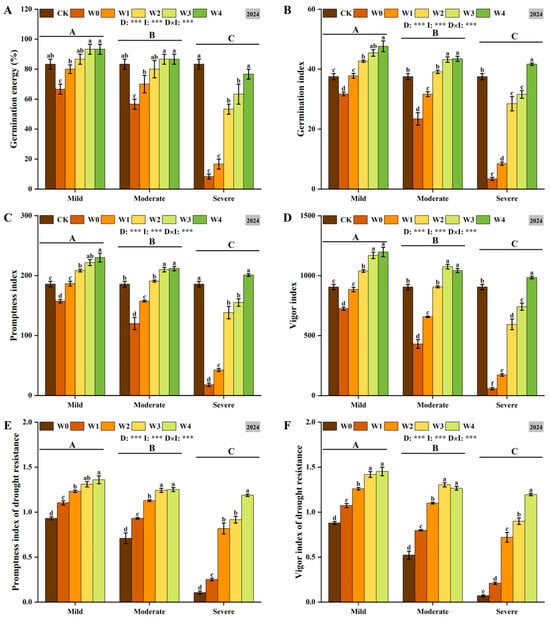

Drought stress significantly inhibited seed germination, and as drought severity increased, germination energy, germination index, promptness index, vigor index, drought resistance germination index, and drought resistance vigor index decreased significantly (Figure 3). Irrigating-sowing effectively alleviated the adverse effects of drought. Under mild and moderate drought conditions, both W3 and W4 significantly improved seed germination characteristics, with no significant difference between them (p < 0.05). Under severe drought conditions, with the increase in irrigation, the effect of alleviating drought stress is more obvious. Furthermore, a significant interaction was observed between drought severity and irrigation level, indicating that both factors coordinately regulate the germination attributes of foxtail millet seeds. These findings demonstrate that optimal irrigation management is crucial for enhancing germination quality.

Figure 3.

The changes in germination energy (A), germination index (B), promptness index (C), vigor index (D), promptness index of drought resistance (E) and vigor index of drought resistance (F) of foxtail millet seeds under irrigating-sowing. Error bars represent the standard error of the mean (n = 3). Different uppercase letters indicate significant differences among drought levels (p < 0.05), and different lowercase letters indicate significant differences among irrigation treatments within the same drought level (p < 0.05). D, I, and D × I represent the main effects of drought, irrigation, and their interaction, respectively. *, **, and *** indicate significant differences at p < 0.05, p < 0.01, and p < 0.001, respectively.

In conclusion, appropriate irrigation optimizes the seed germination environment, effectively alleviates drought stress, promotes the coordinated growth of roots and shoots, and ultimately improves germination quality. Specifically, W3 is optimal under mild and moderate drought, while W4 performs best under severe drought conditions.

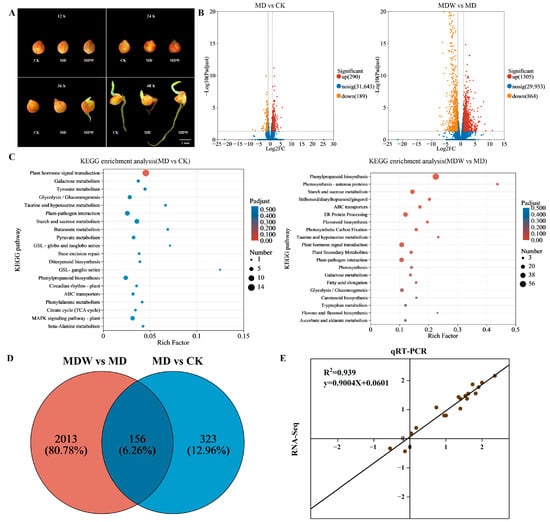

2.2. Transcriptomic Responses of Foxtail Millet Seeds to Irrigating-Sowing During Germination

To further characterize the transcriptional and metabolic responses associated with seeds germinating faster under irrigating-sowing, transcriptome sequencing was performed on foxtail millet seeds germinated for 48 h under three treatments: moderate drought with W0 (MD, 0 m3·hm−2), moderate drought with W3 (MDW, 13.5 m3·hm−2), and CK (field capacity 70% ± 5%). Morphological changes in seeds every 12 h under these treatments are shown in Figure 4A. In the comparisons of MD vs. CK and MDW vs. MD, 479 and 2169 differentially expressed genes (DEGs; |log2 fold change| > 1) were identified, respectively. Among them, 290 and 1305 genes were upregulated, and 189 and 864 were downregulated (Figure 4B). The Venn diagram illustrates the overlap of DEGs between the two comparisons (Figure 4D). KEGG pathway enrichment analysis revealed that these DEGs were mainly enriched in pathways related to plant hormone signal transduction, glycolysis, starch and sucrose metabolism, phenylpropanoid biosynthesis, and flavonoid biosynthesis (Figure 4C). To verify the reliability of the transcriptomic data, six DEGs were randomly selected for qRT-PCR analysis, covering key pathways identified in the study, including carbohydrate metabolism, secondary metabolism, and hormone signaling pathways, to ensure the representativeness of the validation. The results showed a high correlation between RNA-Seq and qRT-PCR data, confirming the accuracy of the transcriptome analysis (Figure 4E).

Figure 4.

Transcriptional reprogramming induced by irrigating-sowing. (A) Changes in seeds per 12 h under CK, MD and MDW. (B) Volcano maps showing differentially expressed genes (DEGs) in different comparisons. (C) KEGG pathway enrichment analysis under different comparisons; the color scale is expressed as a significant level. (D) Venn diagram shows the overlapping DEGs in different comparisons. (E) Validation of transcriptome data by qRT-PCR.

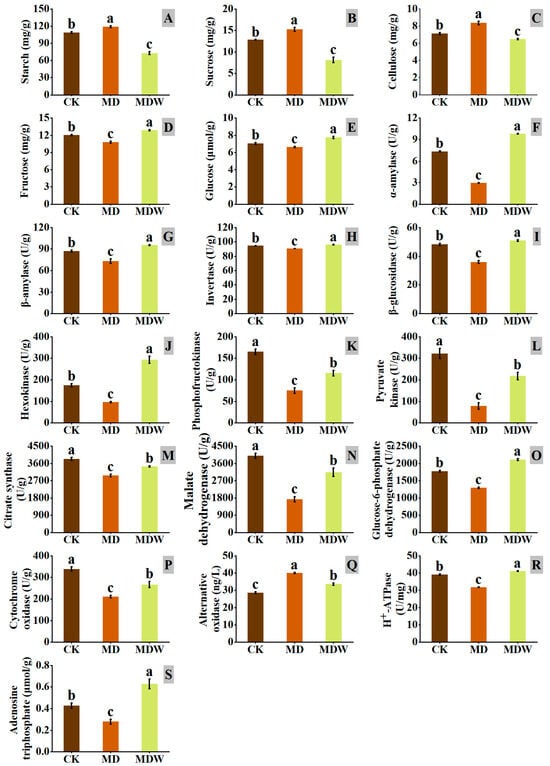

2.3. Carbohydrate and Energy Metabolism Responses to Irrigating-Sowing in Foxtail Millet

Under MDW treatment, carbohydrate metabolism and energy generation pathways changed significantly during foxtail millet seed germination. First, the mobilization of stored carbon sources was significantly enhanced. Compared to MD, MDW significantly increased the activities of AMY and BMY by 231.48% and 30.65%, respectively, while starch content decreased by 38.83%. Additionally, the transcript levels of genes encoding INV and BGL were higher under the MDW treatment (Figure 5), accompanied by increases of 6.03% and 41.64% in their corresponding enzyme activities, and decreases of 46.80% and 22.58% in sucrose and cellulose contents, respectively (Figure 6B,C). Furthermore, MDW significantly upregulated the expression of EG and TPP genes involved in UDP-glucose degradation and trehalose synthesis (Figure 5), and the contents of fructose and glucose increased by 19.53% and 16.93%, respectively, compared to MD (Figure 6D,E), indicating enhanced accumulation of soluble sugars, providing sufficient substrates for downstream energy metabolism.

Figure 5.

Changes in carbohydrate and energy metabolism under irrigating-sowing. The scale represents log2 (fold-change).

Figure 6.

The changes in enzymes and substances related to carbohydrate and energy metabolism under Irrigating-sowing. (A) starch, (B) sucrose, (C) cellulose, (D) fructose, (E) glucose, (F) α-amylase (AMY), (G) β-amylase (BMY), (H) invertase (INV), (I) β-glucosidase (BGL), (J) hexokinase (HK), (K) phosphofructokinase (PFK), (L) pyruvate kinase (PK), (M) citrate synthase (CS), (N) malate dehydrogenase (MDH), (O) glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PDH), (P) cytochrome oxidase (CCO), (Q) alternative oxidase (AOX), (R) plasma membrane H+-ATPase (PM-H+-ATPase), and (S) ATP. The error bars represent the standard error of the mean. Different lowercase letters showed significant differences between different treatments (p < 0.05).

In the glycolysis pathway, MDW significantly upregulated the expression of key enzymes such as FBA, ENO, and PK (Figure 5), and the corresponding enzyme activities were significantly enhanced. PK, PFK, and HK activities increased by 177.78%, 54.00%, and 203.85%, respectively (Figure 6J,K,L), leading to a significant increase in glycolytic flux and enhanced pyruvate production.

In the tricarboxylic acid cycle, MDW significantly increased the activity of CS and MDH by 16.04% and 81.82%, respectively, compared to MD (Figure 6M,N). This resulted in an accelerated rate of pyruvate oxidation and increased generation of NADH and other electron donors, providing sufficient substrates for subsequent oxidative phosphorylation.

In the pentose phosphate pathway, MDW significantly upregulated the expression of the TK gene (Figure 5), and the activity of G6PDH increased by 63.02% (Figure 6O), reflecting an increased rate of NADPH production, which helps maintain cellular redox balance.

During oxidative phosphorylation, MDW significantly increased the expression of ATPs-γ and PMH+-ATPase genes (Figure 5), leading to significant increases in enzyme activities, with cytochrome c oxidase (CCO) and PMH+-ATPase activities increasing by 26.40% and 29.82%, respectively (Figure 6P,R). In contrast, the activity of AOX decreased by 15.93% (Figure 6Q), indicating that more electrons were directed toward high-efficiency synthetic pathways. Finally, ATP content increased by 124.98% compared to MD (Figure 6S), demonstrating that MDW effectively enhanced oxidative phosphorylation efficiency and ATP production capacity.

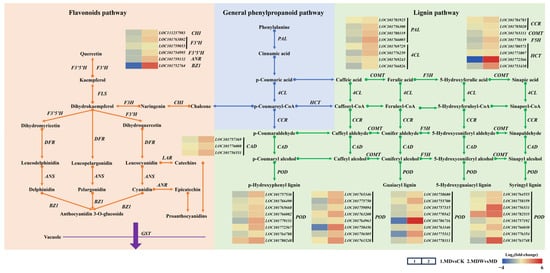

2.4. Secondary Metabolism Responses to Irrigating-Sowing in Foxtail Millet

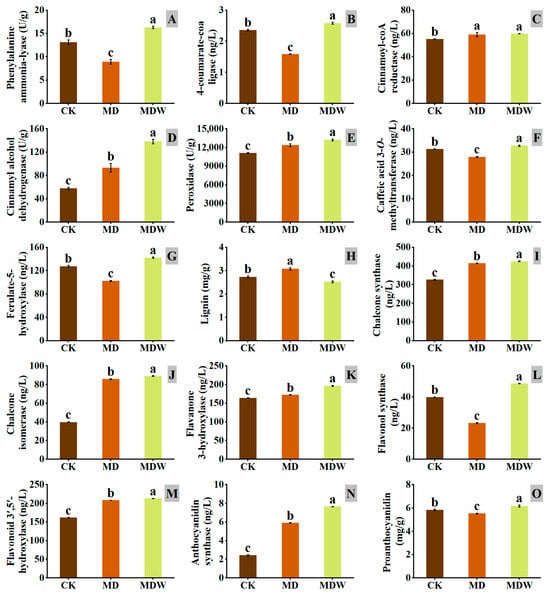

Under drought stress, the expression of genes involved in phenylpropanoid metabolism (PAL, 4CL) was significantly downregulated, but irrigation reversed this change (Figure 7). Specifically, PAL and 4CL enzyme activities increased by 82.58% and 63.00%, respectively, under MDW compared to MD (Figure 8A,B).

Figure 7.

Changes in secondary metabolism under irrigating-sowing. The scale represents log2 (fold-change).

Figure 8.

The changes in enzymes and secondary metabolites under irrigating-sowing. (A) phenylalanine ammonia lyase (PAL), (B) 4-coumarate coenzyme-A-ligase (4CL), (C) cinnamoyl-CoA reductase (CCR), (D) cinnamyl alcohol dehydrogenase (CAD), (E) peroxidase (POD), (F) caffeic acid 3-O-methyltransferase (COMT), (G) ferulic acid-5-hydroxylase (F5H), (H) lignin, (I) chalcone synthase (CHS), (J) chalcone isomerase (CHI), (K) flavanone 3-hydroxylase (F3H), (L) flavonol synthase (FLS), (M) flavonoid 3′,5′-hydroxylase (F3′5′H), (N) anthocyanin synthase (ANS), and (O) proanthocyanidin. The error bars represent the standard error of the mean. Different lowercase letters showed significant differences between different treatments (p < 0.05).

The transcript abundance of CCR, a key gene in lignin biosynthesis, was higher under MDW than MD (Figure 7), corresponding, a 1.36% increase in CCR enzyme activity under MDW (Figure 8C). Drought stress downregulated the expression of other lignin biosynthesis genes (COMT, F5H, HCT, POD), but irrigation reversed this effect. MDW significantly increased COMT, F5H, and POD enzyme activities by 17.20%, 39.04%, and 6.82%, respectively (Figure 8E–G). Additionally, the transcript abundance of CAD was significantly higher under MDW, resulting in a 48.28% increase in CAD enzyme activity (Figure 8D). However, lignin content in MD was 21.89% higher than in MDW (Figure 8H).

In flavonoid biosynthesis-related genes (CHI, F3H, F3′5′H), irrigation significantly upregulated their expression, with transcript abundance being significantly higher under MDW than MD. Furthermore, the enzyme activities of CHS, CHI, F3H, F3′5′H, and FLS increased by 2.53%, 3.88%, 14.07%, 2.24%, and 109.44%, respectively, under MDW compared to MD (Figure 8I–M). Additionally, the transcript abundance of ANR and BZ1, involved in proanthocyanidin biosynthesis, was also significantly increased under MDW, correlating with a 29.82% increase in ANS activity. As a result, proanthocyanidin content increased by 11.46% in MDW compared to MD.

In summary, irrigation-sowing alleviated drought stress and reprogrammed phenylpropanoid metabolism, leading to enhanced activity of key enzymes in lignin biosynthesis and increased accumulation of flavonoids and proanthocyanidins. These changes are likely related to the alleviation of drought stress and the enhancement of seed germination potential, further confirming irrigation’s role in regulating plant secondary metabolism.

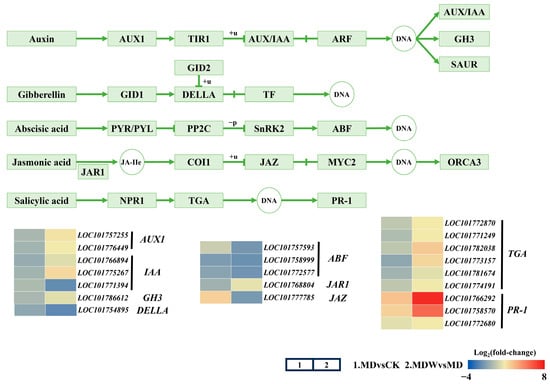

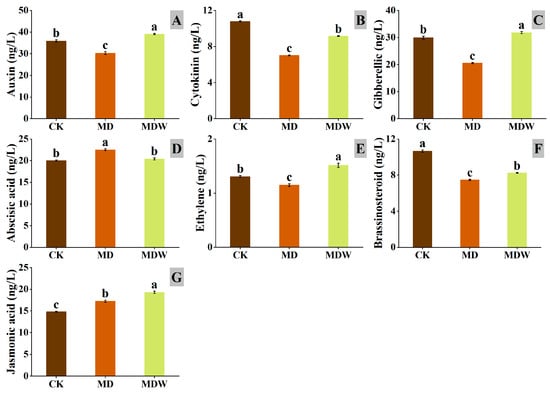

2.5. Changes in Plant Hormone Content and Signaling Pathways Under Irrigating-Sowing

KEGG pathway analysis showed that MDW upregulated the expression of AUX1, IAA, and GH3 in the IAA pathway (Figure 9), enhancing auxin signaling, which supports cell elongation and polar growth. In the GA pathway, DELLA expression was downregulated, promoting GA activity. In the ABA pathway, ABF expression was reduced, indicating inhibition of ABA signaling and promoting germination. In the JA pathway, MDW reversed the downregulation of JAR1 and reduced the expression of JAZ, activating JA signaling, which may regulate defense mechanisms. In the SA pathway, MDW enhanced TGA and PR-1 expression, suggesting irrigation induces stronger defense mechanisms to support germination.

Figure 9.

Changes in hormone signaling under irrigating-sowing. The scale represents log2 (fold-change).

Under MDW, several plant hormones in foxtail millet seeds significantly changed. Compared to MD, IAA, CTK, GA, ETH, BR, JA increased by 29.09%, 30.58%, 54.70%, 31.83%, 10.35%, and 11.85%, respectively, while ABA decreased by 9.35% (Figure 10A–G). These results indicate that irrigating-sowing is associated with altered hormone homeostasis that is consistent with a germination-favorable environment.

Figure 10.

The changes in endogenous hormone contents under irrigating-sowing. (A) auxin (IAA), (B) cytokinin (CTK), (C) gibberellin (GA), (D) abscisic acid (ABA), (E) ethylene (ETH), (F) brassinolide (BR), and (G) jasmonic acid (JA). The error bars represent the standard error of the mean. Different lowercase letters showed significant differences between different treatments (p < 0.05).

In summary, MDW reshapes endogenous hormonal homeostasis by activating germination-promoting pathways (IAA, GA, CTK, JA) and inhibiting ABA signaling, establishing a favorable environment for seed germination. Furthermore, the activation of JA and SA pathways enhances early defense responses, contributing to efficient germination under drought stress.

3. Discussion

3.1. Irrigating-Sowing Enhances Foxtail Millet Seed Germination Quality by Promoting Coordinated Root and Shoot Growth

Drought is a major abiotic stress that limits crop production, severely affecting plant metabolism and growth [39]. The seed germination to seedling emergence stage is the most water-sensitive period for crops [40]. This study systematically investigated the physiological and molecular responses of foxtail millet (Jingu 21) seeds to irrigating-sowing under drought conditions. The results showed that under mild and moderate drought conditions, pre-sowing irrigation of 13.5 m3/hm2 significantly improved germination energy, germination index, and vigor index. Under severe drought, irrigation at 18 m3/hm2 also alleviated the effects, indicating that appropriate irrigation improves soil moisture conditions, enhancing germination and seedling quality under dryland conditions.

Further analysis revealed that irrigating-sowing significantly promoted seed water absorption and metabolic activation, restoring both root and shoot lengths, with a more significant response in root growth. This indicates that under drought, roots exhibit prioritized growth to enhance water acquisition. This finding aligns with Voothuluru et al. [41], who reported that plants often maintain or increase root growth under water stress to improve water use efficiency. Additionally, Yan et al. [42] observed that soil moisture in the 0–20 cm layer directly impacts foxtail millet seedling emergence. Inadequate moisture prevents normal seed imbibition and germination. Our study showed that irrigation enhanced moisture in the sowing row, promoting rapid seed imbibition and successful germination. This demonstrates the practical field applicability of this method.

In conclusion, irrigating-sowing significantly alleviates drought-induced inhibition of seed germination, promotes coordinated root and shoot growth, and ultimately improves germination quality. This conclusion is consistent with the findings of Bayu et al. [43] and Queiroz et al. [13], who observed that a decline in water potential significantly suppresses germination, and further supports the practical effectiveness of pre-sowing irrigation in reversing drought’s adverse effects.

3.2. Irrigating-Sowing Enhances Carbohydrate Mobilization and Energy Metabolism During Seed Germination Under Drought Stress

Irrigation-sowing significantly promoted the degradation and utilization of stored carbohydrates such as starch and sucrose. During germination, starch serves as the main energy source, and its breakdown relies on AMY and BMY activities [17,44], which provide energy for cell division and elongation [45]. In this study, irrigation-sowing increased amylase activity, reduced starch content, and raised glucose and fructose levels. These findings contrast with Bai et al. [46], who reported reduced amylase activity and energy limitation under drought, indicating that irrigation-sowing alleviates drought-induced energy deficiency. Similarly, Song et al. [12] found that enhancing reducing sugar content and amylase activity mitigated drought stress in barley germination. Irrigation-sowing also enhanced INV and BGL activities, accelerating sucrose and cellulose degradation and increasing soluble sugars that act as osmolytes and respiratory substrates [47,48].

Moreover, energy metabolism was activated through higher activities of glycolytic enzymes including HK, PFK, and PK, which accelerated pyruvate formation and ATP production. This agrees with Li et al. [49] and Guo et al. [50], who reported that glycolytic enzymes maintain energy supply under drought conditions. Our results further demonstrate that irrigation-sowing not only sustains but also enhances the activities of these key enzymes, thereby improving the overall efficiency of energy metabolism and supporting rapid seed germination under water-limited conditions. In the tricarboxylic acid cycle, CS and MDH activities increased, enhancing organic acid metabolism and NADH production for the respiratory chain. CCO and plasma membrane H+-ATPase activities were upregulated, while AOX decreased, indicating more efficient electron flow toward ATP synthesis. These results contrast with Analin et al. [51] and Varshikar and Tan [52], who observed impaired electron transport and energy limitation under drought, highlighting the mitigating effect of irrigation-sowing. Additionally, G6PDH activity increased, enhancing PPP flux and NADPH production to maintain redox balance [19]. In summary, irrigation-sowing coordinates glycolysis, the TCA cycle, and the PPP to ensure sufficient and efficient energy supply for seed germination.

3.3. Irrigation-Sowing Regulates Secondary Metabolism to Enhance Stress Adaptation

Irrigation-sowing strengthened the phenylpropanoid pathway and its branches. Under MD, the expression of PAL and 4CL decreased, while lignin content increased, indicating that foxtail millet reinforced cell walls through rapid lignin deposition to cope with stress. However, excessive lignification may restrict cell expansion and hinder germination [21,22]. With irrigation-sowing, lignin content declined, suggesting that carbon flux was redirected from lignin biosynthesis to other phenylpropanoid branches. The upregulation of PAL, 4CL, CCR, and CAD indicated activation of the phenylpropanoid pathway, whereas increased expression of CHS, CHI, F3H, FLS, and ANS facilitated the accumulation of flavonoids, anthocyanins, and proanthocyanidins. These findings are consistent with Vogt [20], who emphasized the central role of the phenylpropanoid pathway in plant stress responses, and contrast with Yu et al. [53], who observed that PEG-induced drought suppressed phenylpropanoid metabolism and caused the accumulation of cinnamic acid derivatives that inhibited germination. The present results further demonstrate that irrigation-sowing restores phenylpropanoid activity and promotes flavonoid biosynthesis, thereby enhancing antioxidant defense while reducing the accumulation of potentially inhibitory metabolites, ultimately creating a more favorable metabolic environment for seed germination. Similarly, Bellaloui et al. [54] reported that phenylpropanoid-derived metabolites play key roles in drought tolerance in soybean, and our findings extend this understanding to the germination stage of foxtail millet under water-deficit conditions.

3.4. Irrigation-Sowing Reconfigures Endogenous Hormone Networks to Promote Germination

Irrigation-sowing significantly changed endogenous hormone content and signaling pathway activity. Drought typically induces ABA accumulation by enhancing its biosynthesis and suppressing its degradation, thereby inhibiting germination [24,55]. In this study, irrigation-sowing reduced ABA levels and the expression of its downstream signaling factor ABF, while increasing germination-promoting hormones such as IAA, GA, CTK, BR, and ETH. The GA signaling repressor DELLA was downregulated, facilitating GA-mediated growth. In the IAA pathway, the upregulation of AUX1, IAA, and GH3 indicated enhanced auxin signaling, promoting cell elongation. Elevated CTK levels likely acted synergistically with GA to stimulate cell division and mesocotyl growth [34]. Moreover, irrigation-sowing enhanced JA and SA signaling, as evidenced by JAZ downregulation and PR1 upregulation, suggesting strengthened defense preparedness during early germination [28]. These results indicate that irrigation-sowing reestablishes a hormonal balance favorable for germination by reducing the ABA/GA ratio and elevating IAA, CTK, and JA levels. This finding aligns with the model proposed by Sun and Gubler [25], in which the ABA/GA balance determines seed dormancy and germination.

It should be noted that the transcriptomic analysis was conducted only in 2024, and therefore the gene expression data reflect the responses of foxtail millet to irrigating-sowing under that specific drought environment. Although field experiments conducted in both 2023 and 2024 exhibited consistent physiological and morphological patterns (Supplementary Figures S1 and S2), the transcriptomic results should be interpreted as conditional rather than universal. Moreover, the RNA-seq data were generated from bulk seed samples collected 48 h after sowing, representing the average transcriptional state across multiple cell types and germination stages. Because seed germination is a highly coordinated multicellular process, variations in transcript abundance may partly reflect shifts in the proportion or activation of different cell types rather than direct transcriptional regulation. Consequently, the present findings reveal overall molecular trends associated with irrigating-sowing rather than cell-specific regulatory events. Future studies incorporating multi-year, multi-environment, and cell-type–resolved transcriptomic analyses will be required to confirm and refine these results.

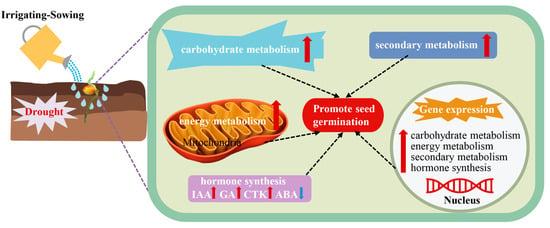

In summary, irrigation-sowing promotes foxtail millet germination under drought by integrating multiple regulatory processes. It improves soil moisture and root growth, activates carbohydrate mobilization and energy metabolism, strengthens phenylpropanoid and flavonoid pathways, and reconfigures hormonal networks (Figure 11). The findings provide new insights into water-mediated germination regulation and offer practical guidance for dryland farming. In arid regions such as the Loess Plateau, irrigation-sowing can substantially improve seedling emergence and establishment, thereby supporting stable foxtail millet production.

Figure 11.

Irrigating-sowing promotes foxtail millet seed germination under drought stress, as reflected by coordinated enhancements in carbohydrate mobilization, energy metabolism, secondary metabolite synthesis, and hormone balance. Red arrows indicate increases, blue arrows indicate decreases, and dashed lines represent associations among processes.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Experimental Materials

In this experiment, high-quality representative foxtail millet variety Jingu 21 was selected as the research material, which was provided by the Institute of Economic Crops, Shanxi Agricultural University, Taigu, China.

4.2. Experimental Site

The experiment was conducted at the Experimental Station of Shanxi Agricultural University (112°55′ E, 37°42′ N, altitude 787.13 m) starting on 12 May 2024. The site is characterized by a semi-arid continental monsoon climate. The soil is classified as sandy loam, with the following properties: soil organic matter content 21.5–24.8 g·kg−1, total nitrogen 1.259–1.363 g·kg−1, total phosphorus 1.099–1.220 g·kg−1, total potassium 14.9–18.1 g·kg−1, available phosphorus 10.3–17.2 mg·kg−1, available potassium 177–245 mg·kg−1, and pH 8.43–8.51. The average daily temperature during the foxtail millet seedling stage was 22.91 °C, with a maximum of 29.24 °C and a minimum of 16.56 °C.

4.3. Experimental Design

The experiment adopted a two-factor split-plot design. The main factor was the soil drought level, categorized according to the agricultural drought classification standards (GB/T 32136-2015) set by the National Agricultural Meteorological Standardization Technical Committee (SAC/TC 539) [56]. Three drought levels were set: mild drought (60%±5% field water holding capacity), moderate drought (50 ± 5%), and severe drought (40 ± 5%). Soil moisture at 0–20 cm depth was measured to confirm that the soil reached severe drought levels before sowing in 2024. The soil bulk density was 1.24 g/cm3, and the maximum field water holding capacity was 25.69%. Based on these measurements, water supplementation was calculated to achieve light and moderate drought conditions (Table 1) [57]. The sub-factor was irrigation volume. Before sowing, water volumes of 0 m3/hm2, 4.5 m3/hm2, 9 m3/hm2, 13.5 m3/hm2, and 18 m3/hm2 were applied to the sowing furrows, labeled as W0, W1, W2, W3, and W4, with field capacity (70% ± 5%) as CK. The irrigation volumes were based on pre-experiment results from 2022 and 2023, as well as references from studies on hill-drop irrigation in foxtail millet [58,59]. Field row spacing was set at 50 cm, with seeds sown at a depth of 3 cm using a drill planting method. Each plot measured 19.25 m2 (5.5 m × 3.5 m) and contained 7 rows. The planting density for Jingu 21 was maintained at 375,000–450,000 plants per hectare. To prevent water infiltration between plots, each plot was surrounded by a 0.5 m partition, and a movable rain shelter was installed to block rain during rainfall while maintaining natural light during other times. The nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium fertilizer application rate was consistent across all treatments, using nitrate phosphate-potassium compound fertilizer (Tianji Coal Chemical Group Co., Ltd., Tianjin, China, N-P2O5-K2O, 22-8-10) at a rate of 600 kg/hm2 (containing 132 kg/hm2 N, 48 kg/hm2 P2O5, and 60 kg/hm2 K2O) as a single basal dose applied to the 0–20 cm soil layer, with no additional fertilizers applied. Other field management practices were consistent with local farmer habits.

Table 1.

Soil water content (%) at 0–20 cm under different drought levels.

4.4. Determination of Seed Germination Characteristics

According to the germination phenotype of foxtail millet, representative seeds from each treatment were photographed and observed for morphological differences. The lengths of roots and shoots were measured with a ruler on Days 2, 4, 6, and 8 after sowing, and the number of germinated seeds was recorded daily. On Day 6, the lengths of the embryo root and coleoptile were measured for germinated seeds. The germination rates on Days 2, 4, 6, and 8 were denoted as nd2, nd4, nd6, and nd8, respectively. Germination parameters were calculated following the method of Bukhari et al. [60].

The promptness index (PI) was calculated as:

PI = 1.00 × nd2 + 0.75 × nd4 + 0.50 × nd6 + 0.25 × nd8

The promptness index of drought resistance (PDI) was determined as:

The vigor index (VI) was calculated as:

where Sx is the average shoot length on Day 6.

VI = GR × Sx

The vigor index of drought resistance (VDI) was calculated as:

The germination energy (GE) was calculated as:

where N4d is the number of seeds germinated by Day 4, and Ntotal is the total number of tested seeds.

The germination index (GI) was calculated as:

where Gt is the number of seeds germinated on day t, and Dt is the corresponding day of germination.

4.5. Determination of Carbohydrate Metabolism

Samples for all biochemical assays, hormone measurements, and transcriptome sequencing were collected 48 h after sowing. The seed coat and pericarps were removed to obtain embryos; for germinated seeds, the embryonic root and coleoptile were separated and immediately stored at −80 °C. Starch content was determined using a starch assay kit (STA20, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) following Dong et al. [61]. Approximately 0.1 g of sample was homogenized in 0.8 mL of distilled water. The activities of α-amylase (AMY) and β-amylase (BMY) were quantified spectrophotometrically at 540 nm using commercial kits (Solarbio, Beijing, China) according to Zhang et al. [62,63] with a UV-2600 spectrophotometer (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan).

The concentrations of sucrose, fructose, and glucose were analyzed by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC, Waters 2695 series, Waters Corp., Milford, MA, USA) following Jia et al. [64] and Liu et al. [65]. Invertase (INV) activity was determined as described by Shahid et al. [66].

Cellulose content was measured using the anthrone colorimetric method [67]. Briefly, 0.2 g of sample was digested with sulfuric acid for 30 min, diluted to 100 mL, and reacted with an anthrone–sulfuric acid reagent. After incubation for 12 min, absorbance was recorded at 620 nm.

The activity of β-glucosidase (BGL) was determined with a commercial kit (Solarbio, Beijing, China). About 0.2 g of sample was homogenized in 1 mL of extraction buffer on ice and centrifuged at 15,000× g for 20 min at 4 °C. The supernatant was used for enzymatic assays according to the manufacturer’s protocol, and absorbance was read at 400 nm.

4.6. Determination of Glycolytic Enzyme Activities

The activities of hexokinase (HK), phosphofructokinase (PFK), and pyruvate kinase (PK) were determined using ELISA kits (Solarbio, Beijing, China) according to the manufacturer’s protocols. Enzyme activities were expressed as μmol·min−1·g−1 fresh weight [68].

The activities of cytochrome c oxidase (CCO) and glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PDH) were measured using commercial kits (BC0940 and BC0260, Solarbio, Beijing, China). For CCO, mitochondria were isolated by differential centrifugation, and absorbance changes were monitored at 550 nm. G6PDH activity was determined from supernatant extracts by measuring NADPH production at 340 nm. The content of alternative oxidase (AOX) was determined using ELISA with absorbance read at 450 nm.

Malate dehydrogenase (MDH) and citrate synthase (CS) activities were assayed following Kumar et al. [69] and Terrier et al. [70], respectively. The MDH assay monitored absorbance at 340 nm, while the CS assay monitored absorbance at 412 nm. Plasma membrane H+-ATPase activity was analyzed according to Li et al. [71] based on inorganic phosphorus release at 660 nm. ATP content was quantified using an ATP assay kit (Solarbio, Beijing, China).

4.7. Determination of Phenylpropanoid Enzymes and Lignin

The activities of phenylalanine ammonia-lyase (PAL) and 4-coumarate-CoA ligase (4CL) were measured following Li et al. [72,73] and Wei et al. [74]. One unit of PAL or 4CL activity was defined as a 0.01 absorbance increase at 290 or 333 nm, respectively.

Peroxidase (POD) activity was assayed according to Phimchan et al. [75] using guaiacol and H2O2 as substrates, and absorbance was recorded at 470 nm.

The contents of ferulate-5-hydroxylase (F5H), cinnamoyl-CoA reductase (CCR), and caffeic acid O-methyltransferase (COMT) were determined using ELISA kits (Solarbio, Beijing, China) at 450 nm, while cinnamyl alcohol dehydrogenase (CAD) activity was assayed spectrophotometrically at 340 nm. Enzyme activities were expressed as U·g−1 fresh weight.

Lignin content was measured following Kim et al. [76]. Samples were sequentially extracted with ethanol and dimethyl sulfoxide, and the final residue was dissolved in NaOH for spectrophotometric determination at 280 nm.

4.8. Determination of Flavonoid and Anthocyanin Pathway Enzyme Activities and Metabolites

Chalcone isomerase (CHI) activity was determined following Lam et al. [77]. Frozen samples were ground in liquid nitrogen, extracted with 0.05 M HEPES–NaOH buffer (pH 7.5), and centrifuged. The reaction mixture contained crude protein, buffer, ethanol, and naringenin chalcone, and absorbance was monitored at 390 nm.

The contents of chalcone synthase (CHS), flavanone 3-hydroxylase (F3H), flavonol synthase (FLS), flavonoid 3′5′-hydroxylase (F3′5′H), and anthocyanidin synthase (ANS) were quantified using ELISA kits (Kebo Biotechnology, China) with absorbance read at 450 nm.

Proanthocyanidins (PAs) were determined following Verardo et al. [78] using HPLC-FLD-ESI-MS after extraction with 80% ethyl acetate and filtration through a 0.2-μm PTFE membrane.

4.9. Determination of Plant Hormones

Plant hormones were extracted and quantified following Wang et al. [68]. Take 0.5 g of the sample, grind it in an ice bath, add 5 mL of 80% (v/v) methanol, centrifuge at 8000× g for 10 min at 4 °C, and collect the supernatant. The concentrations of auxin (IAA), abscisic acid (ABA), cytokinin (CTK), gibberellin (GA), brassinosteroids (BRs), and jasmonic acid (JA) were determined using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kits according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

4.10. RNA Extraction and RNA-Seq Assay

After 48 h of sowing, foxtail millet seeds were sampled and used for RNA-Seq. Total RNA was extracted from the sampled seeds using a TRIzol kit and submitted to Shanghai Majorbio Bio-Pharm Technology Co., Ltd. for sequencing. Quality control was performed with fastp (Version 0.23.4) [79] to obtain clean reads. The clean reads were aligned to the reference genome using HISAT2 (http://ccb.jhu.edu/software/hisat2/index.shtml) (accessed on 1 November 2025) [80]. The Setaria italica reference genome used was GCF_000263155.2_Setaria_italica_v2.0 (https://ftp.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genomes/all/GCF/000/263/155/GCF_000263155.2_Setaria_italica_v2.0/) (accessed on 1 November 2025). Quantification was conducted with RSEM (Version 1.3.3) to obtain gene-level expression. Differentially expressed genes were identified using the DESeq2 R package (v1.42.0) with the criteria FDR < 0.05 and |log2FC| ≥ 1. KEGG annotation was performed using the KEGG database (https://www.genome.jp/kegg/) (accessed on 1 November 2025). KEGG enrichment analysis of significant DEGs was carried out with the Python SciPy package (v1.6.3) (https://scipy.org/install/) (accessed on 1 November 2025) using Fisher’s exact test. To control the false discovery rate, p-values were adjusted by the Benjamini–Hochberg (BH) method, and pathways with adjusted p < 0.05 were considered significantly enriched. Each treatment included three biological replicates. All RNA-Seq data have been deposited in the NCBI Sequence Read Archive (SRA) under BioProject accession number PRJNA1359106 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bioproject/1359106) (accessed on 1 November 2025).

4.11. Quantitative Real-Time PCR Validation

First-strand cDNA was synthesized from total RNA using the Hifair® III 1st Strand cDNA Synthesis SuperMix for qPCR (gDNA digester plus) kit. Quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) was performed with the Hieff® qPCR SYBR Green Master Mix (Low Rox Plus) kit on a Bio-Rad CFX96 system (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). The Actin gene was used as an internal reference, and relative expression levels were calculated using the 2−ΔΔCt method [81]. Six DEGs were randomly selected for qRT-PCR to validate the RNA-seq results. The primer sequences used in this study are listed in Table 2.

Table 2.

qRT-PCR primer sequence.

4.12. Statistical Analysis

Data from three biological replicates are presented as the mean ± standard error (SE). A two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was conducted to evaluate the main effects of drought level, irrigation amount, and their interaction. Significant differences among treatment means were determined using Duncan’s multiple range test at p < 0.05. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS Statistics 26.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Figures were generated with Origin 2021 (OriginLab, Northampton, MA, USA), and heatmaps were visualized using TBtools-II.

5. Conclusions

This study combined field experiments with physiological and transcriptomic analyses to characterize how foxtail millet seeds respond to irrigation-sowing under drought conditions. Irrigation-sowing improved soil moisture and facilitated coordinated root–shoot growth, contributing to better germination quality. Transcriptomic and physiological evidence indicated that irrigated seeds exhibited metabolic states associated with stronger glycolysis, the tricarboxylic acid cycle, and the pentose phosphate pathway, collectively supporting more active energy metabolism. Pathways related to phenylpropanoid and flavonoid metabolism also showed higher activity-associated signatures, accompanied by greater accumulation of antioxidant-related metabolites. In addition, irrigation was associated with a reduced the ABA/GA ratio and increased the relative contents of IAA, CTK, and GA, thereby reestablishing a hormonal balance favorable for germination initiation. In summary, irrigation-sowing functions as an upstream water-supply signal that reshapes metabolic activity and hormonal balance in ways associated with improved early development. This integrated response substantially improves seed germination and seedling establishment under drought, providing theoretical and practical guidance for improving emergence rate and crop stability in arid regions.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/plants14233571/s1, Figure S1: Effects of irrigating-sowing on root and shoot growth of foxtail millet. Figure S2: The changes of germination energy (A), germination index (B), promptness index (C), vigor index (D), promptness index of drought resistance (E) and vigor index of drought resistance (F) of foxtail millet seeds under irrigating-sowing.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.Z. and X.Y.; Methodology, Y.W. and X.Y.; Formal Analysis, B.L. and S.D. (Shide Dan); Resources, S.Y., R.W.; Data Curation, B.L., S.Y. and J.L.; Writing—Original Draft Preparation, B.L. and S.D. (Shide Dan); Writing-Review & Editing J.R., S.D. (Shuqi Dong), Y.W. and X.Y.; Visualization, J.L. and R.W.; Supervision, J.R., S.D. (Shuqi Dong) and L.Z.; Project Administration, X.Y.; Funding Acquisition, X.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Key R&D Plan (2021YFD1901103-5), the China Agriculture Research System of MOF and MARA (CARS-06-14.5-A28), the earmarked fund for Modern Agro-industry Technology Research System of Shanxi Province (2025CYJSTX04), and Shanxi Province Agricultural Key Core Technology Research Sub-project (NYGG03-3).

Data Availability Statement

The data that support this study are available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy.

Acknowledgments

Thank you to all those who helped with this study and to the research projects that sponsored it.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Yang, X.Y.; Wan, Z.W.; Perry, L.; Lu, H.Y.; Wang, Q.; Zhao, C.H.; Li, J.; Xie, F.; Yu, J.C.; Cui, T.X.; et al. Early millet use in northern China. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 3726–3730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diao, X.M.; Schnable, J.; Bennetzen, J.L.; LI, J.Y. Initiation of Setaria as a model plant. Front. Agr. Sci. Eng. 2014, 1, 16–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Q.; Tang, S.; Zhi, H.; Chen, J.F.; Zhang, J.; Liang, H.K.; Alam, O.; Li, H.B.; Zhang, H.; Xing, L.H.; et al. A graph-based genome and pan-genome variation of the model plant Setaria. Nat. Genet. 2023, 55, 1232–1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bai, Y.D.; Xiao, S.; Zhang, Z.C.; Zhang, Y.J.; Sun, H.C.; Zhang, K.; Wang, X.D.; Bai, Z.Y.; Li, C.D.; Liu, L.T. Melatonin improves the germination rate of cotton seeds under drought stress by opening pores in the seed coat. PeerJ 2020, 8, e9450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, W.; Tanveer, M.; Jiang, L.; Wang, L. Pre-soaking foxtail millet seeds with oligosaccharides enhances germination and seedling growth under PEG-induced osmotic stress. Seed Sci. Technol. 2022, 50, 381–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bove, J.; Jullien, M.; Grappin, P. Functional genomics in the study of seed germination. Genome Biol. 2001, 3, reviews1002.1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qing, Y.R.; Che, G.; Wan, L.; Zhang, Y.L.; Qing, Y.G. Research of Irrigating—Sowing Machinery in China. J. Agric. Mech. Res. 2016, 38, 9–14. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Guo, W.D.; Fang, Z.Z.; Liu, J.A. The current situation and prospect draught-resistant irrigation techniques during seeding and its concerned theories. J. Shenyang Agric. Univ. 1996, 12, 58–62. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Sun, S.M.; Liu, G.P.; Zhang, K.; Tao, J.Z.; Jin, X.Y. Study on supplementary sowing technology and supporting equipment in arid area of Heilongjiang province. J. Agric. Mech. Res. 1999, 2, 32–35. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Yin, G.H.; Chen, W.F.; Liu, Z.X.; Zhang, X.D.; Zhang, H.X. Study on Irrigating-sowing with Machine in Semiarid Area of North China. Res. Agric. Mod. 2007, 3, 238–240. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs of the People’s Republic of China. Technical Manual for Large-Scale Corn Yield Improvement Initiative; Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs: Beijing, China, 2024. (In Chinese)

- Song, R.J.; Zhang, X.C.; Feng, C.J.; Zhang, S.; Song, L.Y.; Qi, J.C. Exogenous Hydrogen Promotes Germination and Seedling Establishment of Barley Under Drought Stress by Mediating the ASA-GSH Cycle and Sugar Metabolism. J. Plant Growth Regul. 2023, 42, 2749–2762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Queiroz, M.S.; Oliveira, C.E.S.; Steiner, F.; Zuffo, A.M.; Zoz, T.; Vendruscolo, E.P.; Silva, M.V.; Mello, B.F.F.R.; Cabral, R.C.; Menis, F.T. Drought Stresses on Seed Germination and Early Growth of Maize and Sorghum. J. Agr. Sci. 2019, 11, 310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, F.; Kuo, T.; Rosli, Y.; Liu, M.S.; Wu, L.M.; Chen, L.F.O.; Fletcher, J.C.; Sung, Z.R.; Pu, L. Trithorax Group Proteins Act Together with a Polycomb Group Protein to Maintain Chromatin Integrity for Epigenetic Silencing during Seed Germination in Arabidopsis. Mol. Plant 2018, 11, 659–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Zanten, M.; Koini, M.A.; Geyer, R.; Liu, Y.X.; Brambilla, V.; Bartels, D.; Koornneef, M.; Fransz, P.; Soppe, W.J.J. Seed maturation in Arabidopsis thaliana is characterized by nuclear size reduction and increased chromatin condensation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 20219–20224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perruc, E.; Kinoshita, N.; Lopez-Molina, L. The role of chromatin-remodeling factor PKL in balancing osmotic stress responses during Arabidopsis seed germination. Plant J. 2007, 52, 933–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, M.; Zhang, H.X.; Yan, H.; Qiu, L.; Baskin, C.C. Mobilization and Role of Starch, Protein, and Fat Reserves during Seed Germination of Six Wild Grassland Species. Front. Plant Sci. 2018, 9, 234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.X.; Wang, J.; Lan, H.Y.; Yu, Q.H. Enhanced drought tolerance and photosynthetic efficiency in Arabidopsis by overexpressing phosphoenolpyruvate carboxylase from a single-cell C4 halophyte Suaeda aralocaspica. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1443691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eicks, M.; Maurino, V.; Knappe, S.; Flügge, U.-I.; Fischer, K. The Plastidic Pentose Phosphate Translocator Represents a Link between the Cytosolic and the Plastidic Pentose Phosphate Pathways in Plants. Plant Physiol. 2002, 128, 512–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogt, T. Phenylpropanoid Biosynthesis. Mol. Plant 2010, 3, 2–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, C.Y.; Chen, J.J.; Lv, Z.D.; Gao, X.Z.; Guo, S.N.; Xu, R.; Deng, Z.Y.; Yao, S.H.; Chen, Z.D.; Kang, Y.K.; et al. Staged and repeated drought-induced regulation of phenylpropanoid synthesis confers tolerance to a water deficit environment in Camellia sinensis. Ind. Crops Prod. 2023, 201, 116843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.W.; Zhou, P.; Hu, Z.H.; Teng, R.M.; Wang, Y.X.; Li, T.; Xiong, A.S.; Li, X.H.; Chen, X.; Zhuang, J. CsPAT1, a GRAS transcription factor, promotes lignin accumulation by antagonistic interacting with CsWRKY13 in tea plants. Plant J. 2024, 118, 1312–1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okamoto, M.; Kuwahara, A.; Seo, M.; Kushiro, T.; Asami, T.; Hirai, N.; Kamiya, Y.; Koshiba, T.; Nambara, E. CYP707A1 and CYP707A2, Which Encode Abscisic Acid 8′-Hydroxylases, Are Indispensable for Proper Control of Seed Dormancy and Germination in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2006, 141, 97–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, K.; Liu, X.D.; Xie, Q.; He, Z.H. Two Faces of One Seed: Hormonal Regulation of Dormancy and Germination. Mol. Plant 2016, 9, 34–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, T.P.; Gubler, F. Molecular Mechanism of Gibberellin Signaling in Plants. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2004, 55, 197–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linkies, A.; Müller, K.; Morris, K.; Turečková, V.; Wenk, M.; Cadman, C.S.C.; Corbineau, F.; Strnad, M.; Lynn, J.R.; Finch-Savage, W.E.; et al. Ethylene Interacts with Abscisic Acid to Regulate Endosperm Rupture during Germination: A Comparative Approach Using Lepidium sativum and Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell 2009, 21, 3803–3822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, R.L.; Kim, H.; Bakshi, A.; Binder, B.M. The Ethylene Receptors ETHYLENE RESPONSE1 and ETHYLENE RESPONSE2 Have Contrasting Roles in Seed Germination of Arabidopsis during Salt Stress. Plant Physiol. 2014, 165, 1353–1366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dave, A.; Hernández, M.L.; He, Z.; Andriotis, V.M.E.; Vaistij, F.E.; Larson, T.R.; Graham, I.A. 12-Oxo-Phytodienoic Acid Accumulation during Seed Development Represses Seed Germination in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 2011, 23, 583–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.F.; Hou, Y.X.; Qiu, J.H.; Wang, H.M.; Wang, S.; Tang, L.Q.; Tong, X.H.; Zhang, J. Abscisic acid promotes jasmonic acid biosynthesis via a ‘SAPK10-bZIP72-AOC’ pathway to synergistically inhibit seed germination in rice (Oryza sativa). New Phytol. 2020, 228, 1336–1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mei, S.; Zhang, M.H.; Ye, J.W.; Du, J.C.; Jiang, Y.J.; Hu, Y.R. Auxin contributes to jasmonate-mediated regulation of abscisic acid signaling during seed germination in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 2023, 35, 1110–1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.R.; Yu, D.Q. BRASSINOSTEROID INSENSITIVE2 Interacts with ABSCISIC ACID INSENSITIVE5 to Mediate the Antagonism of Brassinosteroids to Abscisic Acid during Seed Germination in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 2014, 26, 4394–4408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steber, C.M.; McCourt, P. A Role for Brassinosteroids in Germination in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2001, 125, 763–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varbanova, M.; Yamaguchi, S.; Yang, Y.; McKelvey, K.; Hanada, A.; Borochov, R.; Yu, F.; Jikumaru, Y.; Ross, J.; Cortes, D.; et al. Methylation of Gibberellins by Arabidopsis GAMT1 and GAMT2. Plant Cell 2007, 19, 32–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.P.; Li, L.; Ye, T.T.; Zhao, S.J.; Liu, Z.; Feng, Y.Q.; Wu, Y. Cytokinin antagonizes ABA suppression to seed germination of Arabidopsis by downregulating ABI5 expression. Plant J. 2011, 68, 249–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayano-Kanashiro, C.; Calderón-Vázquez, C.; Ibarra-Laclette, E.; Herrera-Estrella, L.; Simpson, J. Analysis of Gene Expression and Physiological Responses in Three Mexican Maize Landraces under Drought Stress and Recovery Irrigation. PLoS ONE 2009, 4, e7531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bennetzen, J.L.; Schmutz, J.; Wang, H.; Percifield, R.; Hawkins, J.; Pontaroli, A.C.; Estep, M.; Feng, L.; Vaughn, J.N.; Grimwood, J.; et al. Reference genome sequence of the model plant Setaria. Nat. Biotechnol. 2012, 30, 555–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.Y.; Liu, X.; Quan, Z.W.; Cheng, S.F.; Xu, X.; Pan, S.K.; Xie, M.; Zeng, P.; Yue, Z.; Wang, W.L.; et al. Genome sequence of foxtail millet (Setaria italica) provides insights into grass evolution and biofuel potential. Nat. Biotechnol. 2012, 30, 549–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, J.H.; Yang, X.X.; Ma, C.Y.; Wang, Y.L.; Zhao, J. Melatonin enhances drought stress tolerance in maize through coordinated regulation of carbon and nitrogen assimilation. Plant Physiol. Bioch. 2021, 167, 958–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, M.S.; Running, S.W. Drought-Induced Reduction in Global Terrestrial Net Primary Production from 2000 Through 2009. Science 2010, 329, 940–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.X.; Xu, L.H.; Shi, Y.; Cheng, T.F.; Tan, W.L.; Zhao, Y.G.; Li, C.S.; Yang, X.Y.; Ouyang, L.J.; Wei, M.K.; et al. Transcriptome profile analysis of Indian mustard (Brassica juncea L.) during seed germination reveals the drought stress-induced genes associated with energy, hormone, and phenylpropanoid pathways. Plant Physiol. Bioch. 2023, 200, 107750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voothuluru, P.; Wu, Y.J.; Sharp, R.E. Not so hidden anymore: Advances and challenges in understanding root growth under water deficits. Plant Cell 2024, 36, 1377–1409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, J.K.; Zhang, N.N.; Zhang, S.Q. Physiological and ecological responses of foxtail millet to drought stress. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2021, 41, 8612–8622. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayu, W.; Rethman, N.F.G.; Hammes, P.S.; Pieterse, P.A.; Grimbeek, J.; Van Der Linde, M. Water stress affects the germination, emergence, and growth of different sorghum cultivars. Sinet: Ethiop. J. Sci. 2005, 28, 119–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betts, N.S.; Wilkinson, L.G.; Khor, S.F.; Shirley, N.J.; Lok, F.; Skadhauge, B.; Burton, R.A.; Fincher, G.B.; Collins, H.M. Morphology, Carbohydrate Distribution, Gene Expression, and Enzymatic Activities Related to Cell Wall Hydrolysis in Four Barley Varieties during Simulated Malting. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 1872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, H.L.; Dou, Z.Y.; Jiang, W.H.; Mahmood, H.; Liao, Z.Q.; Li, Z.J.; Fan, J.L. Optimal Water and Nitrogen Regimes Increased Fruit Yield and Water Use Efficiency by Improving Root Characteristics of Drip-Fertigated Greenhouse Tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.). Agronomy 2024, 14, 2439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, S.S.; Kang, Y.H.; Wan, S.Q. Winter wheat growth and water use under different drip irrigation regimes in the North China Plain. Irrig. Sci. 2020, 38, 321–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, M.; Kumar, J.; Singh, S.; Singh, V.P.; Prasad, S.M. Roles of osmoprotectants in improving salinity and drought tolerance in plants: A review. Rev. Environ. Sci. Biotechnol. 2015, 14, 407–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pommerrenig, B.; Ludewig, F.; Cvetkovic, J.; Trentmann, O.; Klemens, P.A.W.; Neuhaus, H.E. In Concert: Orchestrated Changes in Carbohydrate Homeostasis Are Critical for Plant Abiotic Stress Tolerance. Plant Cell Physiol. 2018, 59, 1290–1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.Z.; Li, C.X.; Han, P.B.; Wang, Y.H.; Ren, Y.Z.; Xin, Z.Y.; Lin, T.B.; Lian, Y.H.; Wang, Z.Q. Propionic Acid Signalling Modulates Stomatal Opening and Drives Energy Metabolism to Enhance Drought Resistance in Wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). Plant Cell Environ. 2025, 48, 6070–6085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, R.; Shi, L.X.; Jiao, Y.; Li, M.X.; Zhong, X.L.; Gu, F.X.; Liu, Q.; Xia, X.; Li, H.R. Metabolic responses to drought stress in the tissues of drought-tolerant and drought-sensitive wheat genotype seedlings. AoB PLANTS 2018, 10, ply016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Analin, B.; Bakka, K.; Challabathula, D. Exacerbation of drought-induced physiological and biochemical changes in leaves of Pisum sativum upon restriction of COX and AOX pathways of mitochondrial oxidative electron transport. J. Biosci. 2024, 49, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varshikar, D.; Tan, F.C. Salt and drought stress affects electron transport chain genes in rice. Int. J. Adv. Appl. Sci. 2017, 4, 106–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, A.L.; Zhao, J.F.; Wang, Z.H.; Cheng, K.; Zhang, P.; Tian, G.; Liu, X.; Guo, E.H.; Du, Y.W.; Wang, Y.W. Transcriptome and metabolite analysis reveal the drought tolerance of foxtail millet significantly correlated with phenylpropanoids-related pathways during germination process under PEG stress. BMC Plant Biol. 2020, 20, 274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bellaloui, N.; Mengistu, A.; Zobiole, L.H.S. Phomopsis Seed Infection Effects on Soybean Seed Phenol, Lignin, and Isoflavones in Maturity Group V Genotypes Differing in Phomopsis Resistance. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2012, 26, 693–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kushiro, T.; Okamoto, M.; Nakabayashi, K.; Yamagishi, K.; Kitamura, S.; Asami, T.; Hirai, N.; Koshiba, T.; Kamiya, Y.; Nambara, E. The Arabidopsis cytochrome P450 CYP707A encodes ABA 8′-hydroxylases: Key enzymes in ABA catabolism. EMBO J. 2004, 23, 1647–1656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- GB/T 32136-2015[S]; Grade of Agricultural Drought. National Technical Committee 539 on Agrometeorology of Standardization Administration of China: Beijing, China; Standards Press of China: Beijing, China, 2015.

- Omidi, H.; Shams, H.; Sahandi, M.S.; Rajabian, T. Balangu (Lallemantia sp.) growth and physiology under field drought conditions affecting plant medicinal content. Plant Physiol. Bioch. 2018, 130, 641–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.J. Experiment on Green Integrated Technology of Dryland Millet in Pinglu District. Agric. Technol. Equip. 2020, 12, 10–12. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.L.; Yu, C.X.; Li, L.J.; Cui, X.X.; Luo, Y.L. Effects of Super Absorbent Polymer to Drought Resistance, Seedling and Yield of Millet. Chin. Agric. Sci. Bull. 2014, 30, 238–244. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Bukhari, M.A.; Shah, A.N.; Fahad, S.; Iqbal, J.; Nawaz, F.; Manan, A.; Baloch, M.S. Screening of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) genotypes for drought tolerance using polyethylene glycol. Arab. J. Geosci. 2021, 14, 2808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, H.; Hu, C.Y.; Liu, C.C.; Wang, J.C.; Zhou, Y.H.; Yu, J.Q. ELONGATED HYPOCOTYL 5 mediates blue light-induced starch degradation in tomato. J. Exp. Bot. 2021, 72, 2627–2641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.R.; Zang, J.; Huo, Y.Q.; Zhang, Z.G.; Chen, H.B.; Chen, X.J.; Liu, J. Identification of the Potential Genes Regulating Seed Germination Speed in Maize. Plants-Basel 2022, 11, 556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.C.; Hua, D.; Xu, J.X.; Yang, L.N.; Zhou, D.Y.; He, Y.T.; Liu, Y.H.; Tang, A.; Lu, B.X.; Liu, H. Pulsed light treatment enhances starch hydrolysis and improves starch physicochemical properties of germinated brown rice. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2023, 104, 1599–1608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jia, H.F.; Chai, Y.M.; Li, C.L.; Lu, D.; Luo, J.J.; Qin, L.; Shen, Y.Y. Abscisic Acid Plays an Important Role in the Regulation of Strawberry Fruit Ripening. Plant Physiol. 2011, 157, 188–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Qi, Z.Y.; Wei, J.S.; Yu, J.Q.; Xia, X.J. Brassinosteroids promote starch synthesis and the implication in low-light stress tolerance in Solanum lycopersicum. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2022, 201, 104990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahid, M.A.; Balal, R.M.; Khan, N.; Zotarelli, L.; Liu, G.D.; Sarkhosh, A.; Fernández-Zapata, J.C.; Martínez Nicolás, J.J.; Garcia-Sanchez, F. Selenium impedes cadmium and arsenic toxicity in potato by modulating carbohydrate and nitrogen metabolism. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2019, 180, 588–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, C.T.; Zhang, L.; Duan, X.W.; Chai, X.R.; Huang, R.M.; Kang, Y.Y.; Yang, X. Effects of exogenous sucrose and selenium on plant growth, quality, and sugar metabolism of pea sprouts. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2021, 102, 2855–2863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Tang, C.J.; Mi, X.; Yao, D.B.; Chen, Z.K.; Guo, C.; Zhao, Y.P.; Xue, X.D.; Chang, W.D.; Li, Y.H. Zinc oxide nanoparticles alleviated vanadium-induced inhibition by regulating plant hormone signal transduction and phenylpropanoid biosynthesis in maize seedlings (Zea mays L.). Environ. Technol. Innov. 2024, 35, 103696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.G.; Shah, K.; Dubey, R.S. Salinity induced behavioural changes in malate dehydrogenase and glutamate dehydrogenase activities in rice seedlings of differing salt tolerance. Plant Sci. 2000, 156, 23–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terrier, N.; Sauvage, F.X.; Ageorges, A.; Romieu, C. Changes in acidity and in proton transport at the tonoplast of grape berries during development. Planta 2001, 213, 20–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.Y.; Zheng, X.L.; Liu, Y.; Zhu, Y.Y. Pre-storage application of oxalic acid alleviates chilling injury in mango fruit by modulating proline metabolism and energy status under chilling stress. Food Chem. 2014, 142, 72–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Limwachiranon, J.; Li, L.; Zhang, L.; Xu, Y.Q.; Fu, M.R.; Luo, Z.S. Hydrogen peroxide accelerated the lignification process of bamboo shoots by activating the phenylpropanoid pathway and programmed cell death in postharvest storage. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2019, 153, 79–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.G.; Xu, Y.H.; Bi, Y.; Zhang, B.; Shen, S.L.; Jiang, T.J.; Zheng, X.L. Melatonin treatment inhibits gray mold and induces disease resistance in cherry tomato fruit during postharvest. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2019, 157, 110962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.Y.; Zhou, D.D.; Peng, J.; Pan, L.Q.; Tu, K. Hot Air Treatment Induces Disease Resistance through Activating the Phenylpropanoid Metabolism in Cherry Tomato Fruit. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2017, 65, 8003–8010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phimchan, P.; Chanthai, S.; Bosland, P.W.; Techawongstien, S. Enzymatic Changes in Phenylalanine Ammonia-lyase, Cinnamic-4-hydroxylase, Capsaicin Synthase, and Peroxidase Activities in Capsicum under Drought Stress. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2014, 62, 7057–7062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.; Jeon, S.J.; Yanders, S.; Park, S.C.; Kim, H.S.; Kim, S. MYB3 plays an important role in lignin and anthocyanin biosynthesis under salt stress condition in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell Rep. 2022, 41, 1549–1560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, P.Y.; Wang, L.X.; Lui, A.C.W.; Liu, H.J.; Takeda-Kimura, Y.; Chen, M.X.; Zhu, F.Y.; Zhang, J.H.; Umezawa, T.; Tobimatsu, Y. Deficiency in flavonoid biosynthesis genes CHS, CHI, and CHIL alters rice flavonoid and lignin profiles. Plant Physiol. 2022, 188, 1993–2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verardo, V.; Cevoli, C.; Pasini, F.; Gómez-Caravaca, A.M.; Marconi, E.; Fabbri, A.; Caboni, M.F. Analysis of Oligomer Proanthocyanidins in Different Barley Genotypes Using High-Performance Liquid Chromatography–Fluorescence Detection–Mass Spectrometry and Near-Infrared Methodologies. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2015, 63, 4130–4137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.F.; Zhou, Y.Q.; Chen, Y.R.; Gu, J. fastp: An ultra-fast all-in-one FASTQ preprocessor. Bioinformatics 2018, 34, i884–i890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.H.; Langmead, B.; Salzberg, S.L. HISAT: A fast spliced aligner with low memory requirements. Nat. Methods 2015, 12, 357–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livak, K.J.; Schmittgen, T.D. Analysis of Relative Gene Expression Data Using Real-Time Quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCT Method. Methods 2001, 25, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).