Integrated Metabolomics and Transcriptomics Analyses Reveal the Critical Role of Caffeic Acid in Potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) Cold Tolerance

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Growth Conditions

2.2. Experimental Design for Phenotyping with Statistical Evaluation

2.3. Measurement of Caffeic Acid and Cinnamic Acid Levels Using Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay

2.4. Physiological Indicators Analysis

2.5. Metabolomic and Transcriptomic Analysis

2.5.1. Sample Preparation for Metabolomic and Transcriptomic Analysis

2.5.2. Metabolomic Analysis

2.5.3. Transcriptomic Analysis

2.6. Quantitative Reverse Transcription Polymerase Chain Reaction Analysis

2.7. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Cold Stress-Induced Phenotypic Variation in Potatoes

3.2. Alterations in Small Molecule Indicator and Physiological Parameters in Potatoes Under Cold Stress

3.3. Metabolome Profiling of Potatoes Exposed to Cold Stress

3.4. Transcriptomic Analysis of Potatoes in Response to Cold Stress

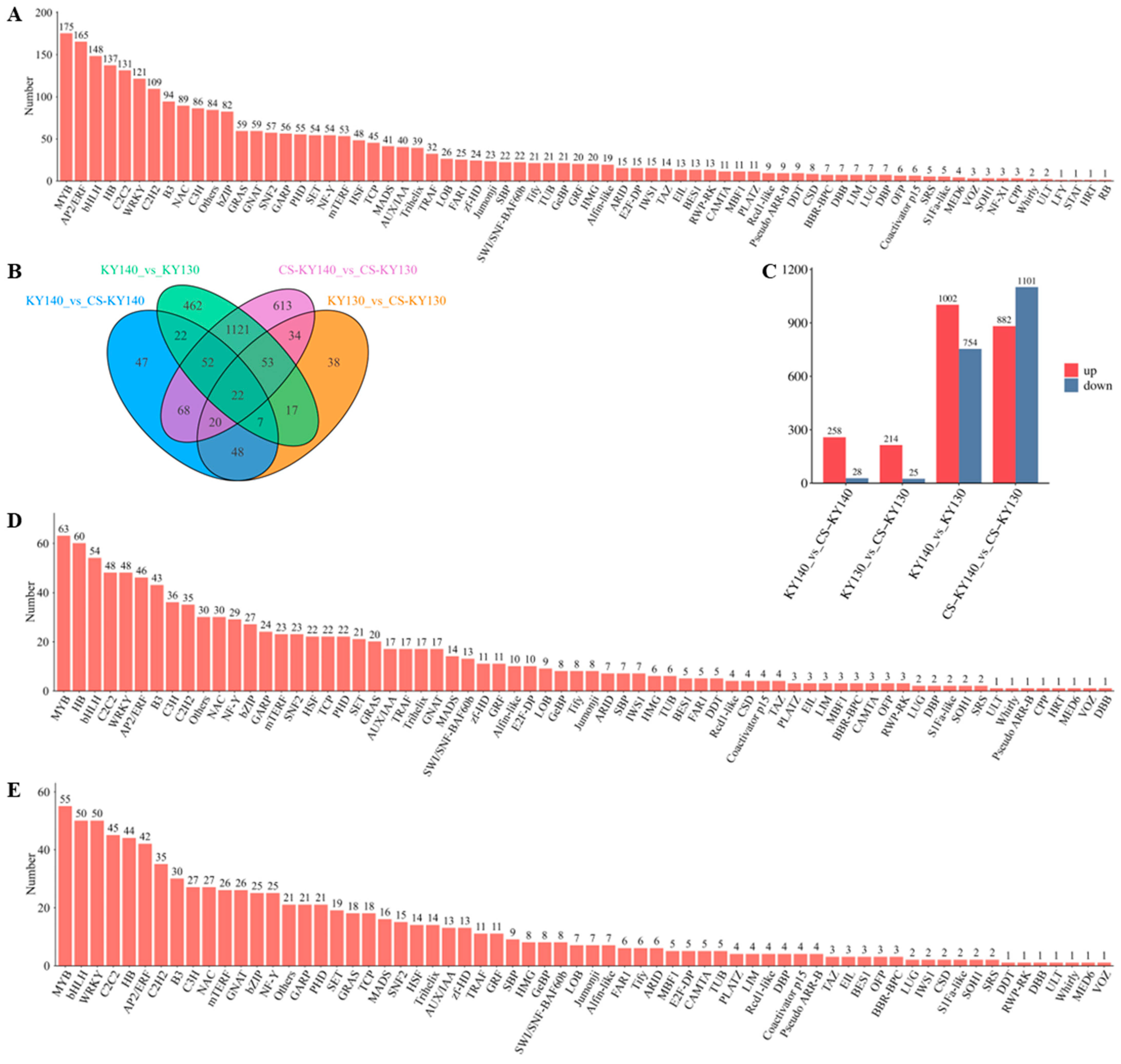

3.5. Identification and Expression Analysis of Transcription Factors Involved in Cold Stress Response

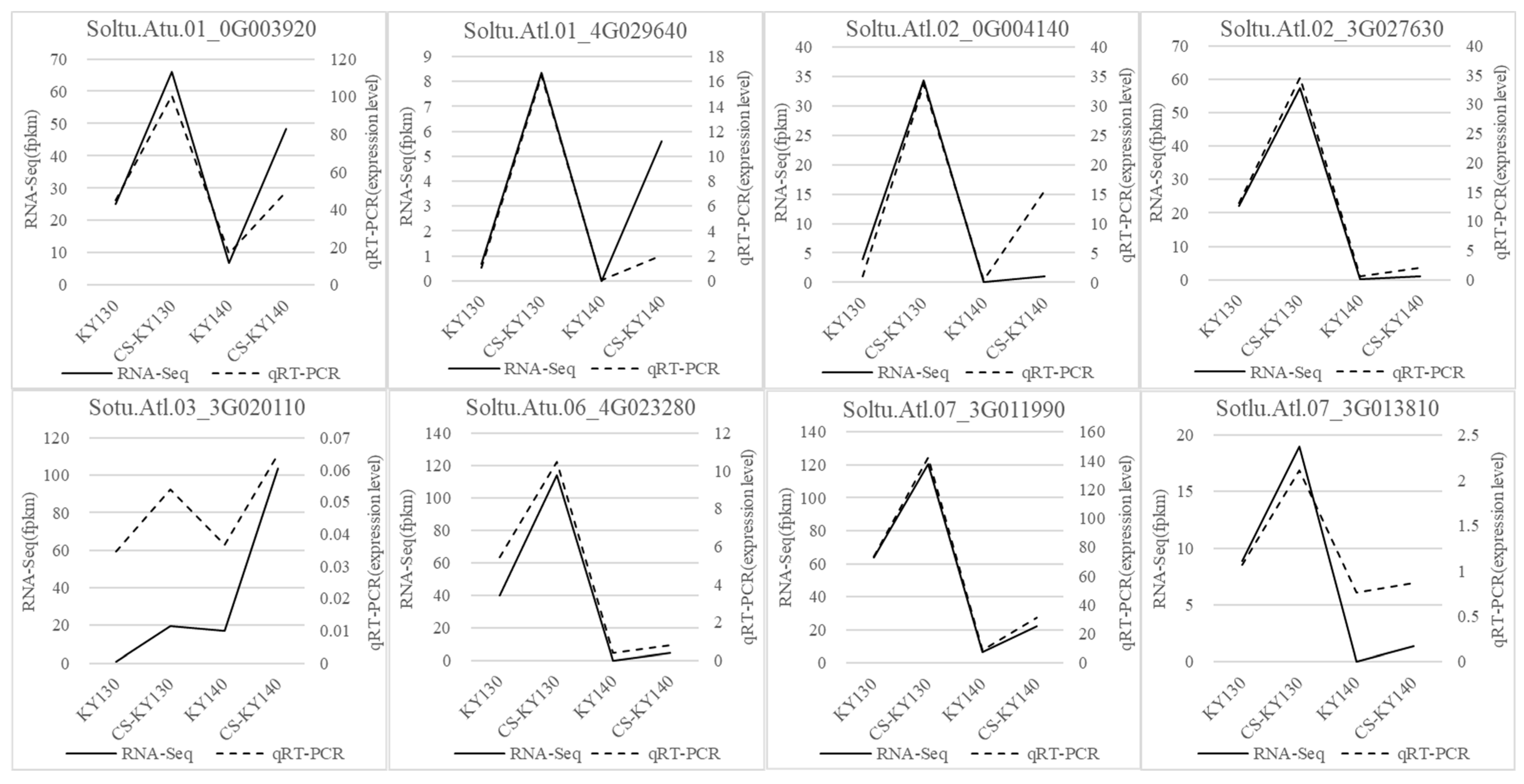

3.6. RNA-Seq Data Validation via Quantitative Reverse Transcription Polymerase Chain Reaction

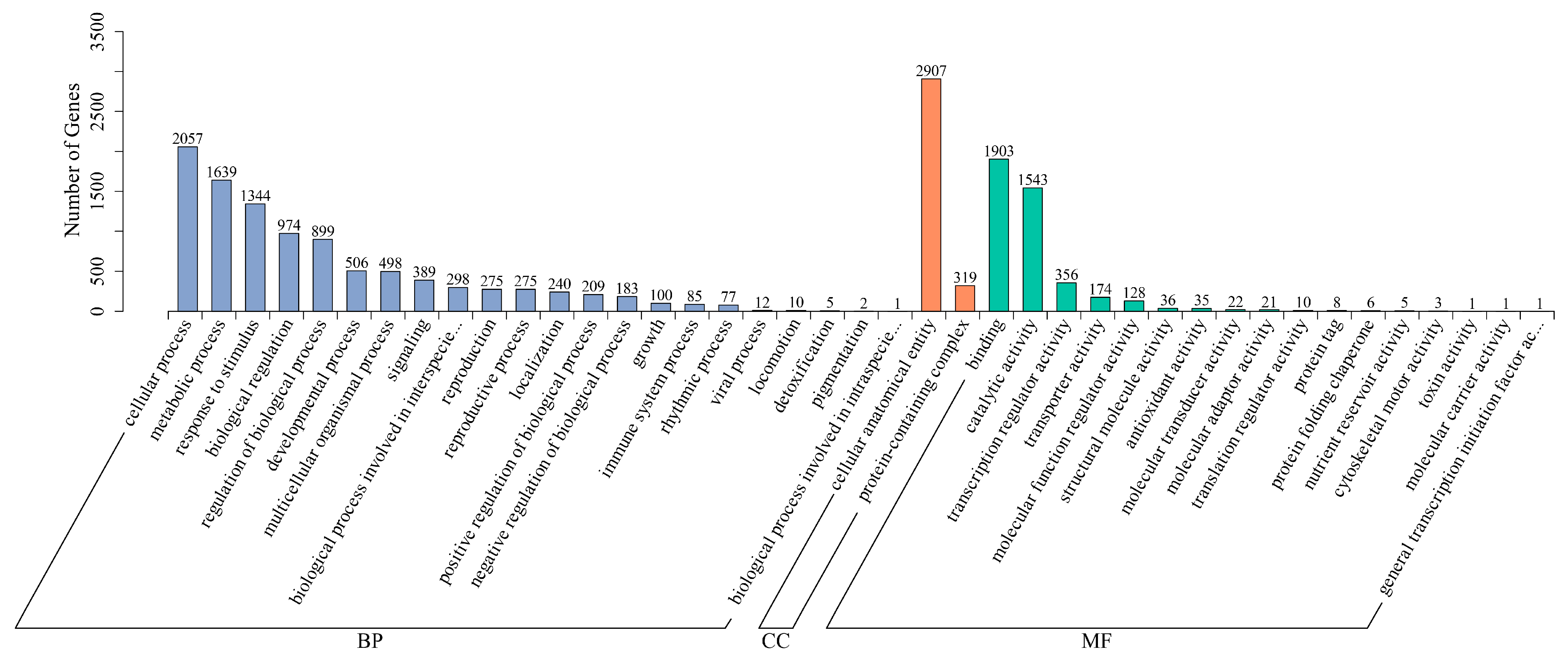

3.7. Gene Ontology Enrichment Analysis

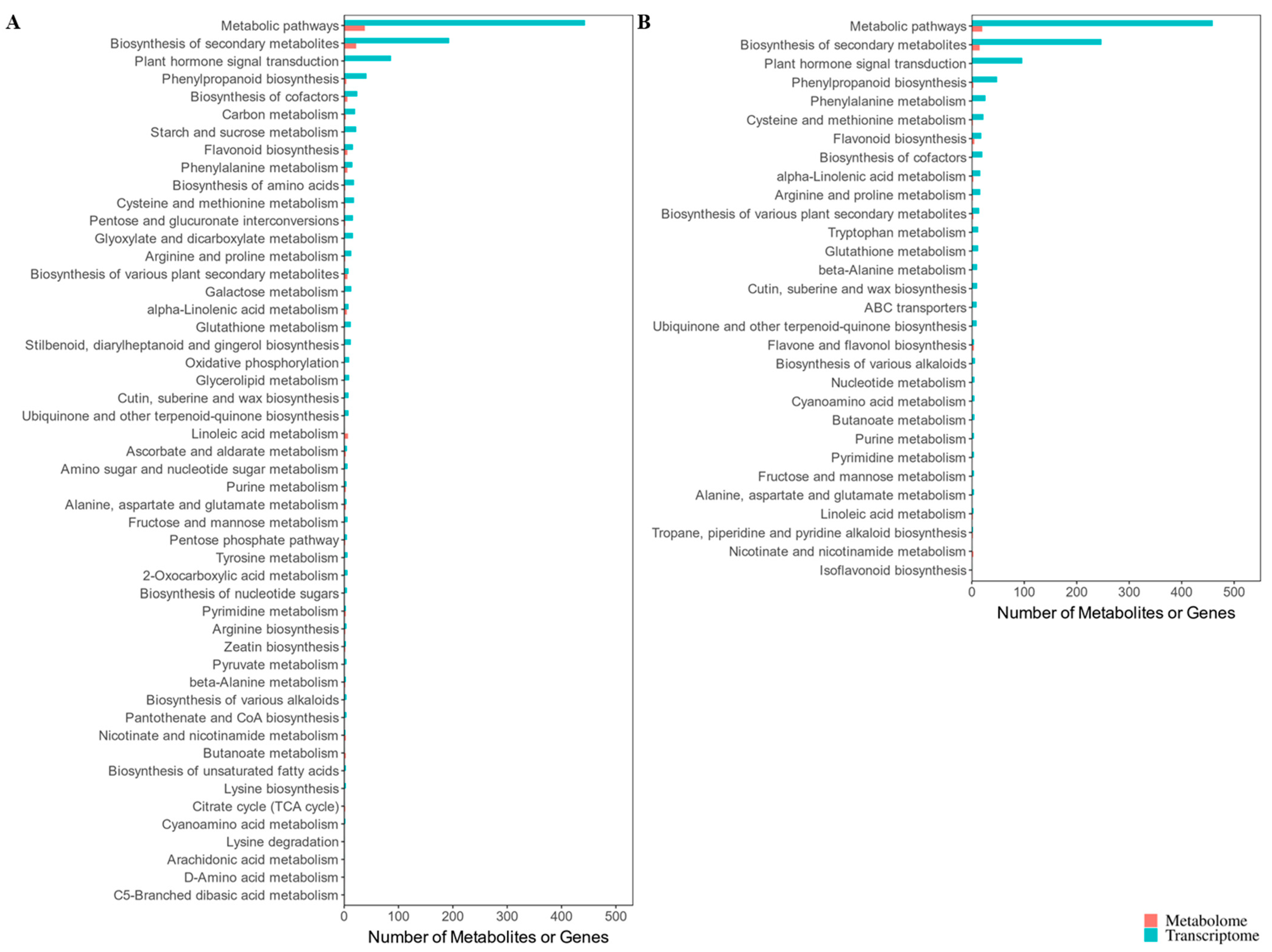

3.8. Integrated Metabolomic and Transcriptomic Analysis to Reveal Crucial Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes Pathways Responsive to Cold Stress

3.9. “Flavonoid-Related Metabolism” in Response to Cold Stress

3.10. “Lipid Metabolism” in Response to Cold Stress

3.11. “Amino Acid Metabolism” in Response to Cold Stress

4. Discussion

4.1. Role of Osmotic Regulating Substances and Antioxidant Enzyme Systems in Potato Cold Resistance

4.2. Functional Implications of Differentially Accumulated Metabolites in Potatoes Under Cold Stress

4.3. Investigation of Transcription Factors in the Cold Stress Response of Potatoes

4.4. Key Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes Pathways Identified Through the Combined Analysis

4.5. Flavonoid-Related Metabolism Plays an Important Role in Potato Response to Low Temperatures

4.6. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Qiu, J.; Zhu, H.; Liu, P.; Wang, J.; Sun, J.M. Analysis on nutrients of main cultivars of colored fleshed potatoes in China. Food Nutr. China 2018, 24, 10–14. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.T.; Suo, H.C.; Li, C.C.; Wang, L.; Shan, J.W.; An, K.; Li, X.B. Research progress in potato cold resistance. Guangdong Agric. Sci. 2020, 47, 73–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, Q.Q.; Luo, X.B.; Li, F.; Luo, C.; Feng, W.H.; Chen, M.J.; Cao, Z.J. Identification and selection for cold resistance of potato. Seed 2023, 42, 121–126, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodziewicz, P.; Swarcewicz, B.; Chmielewska, K.; Wojakowska, A.; Stobiecki, M. Influence of abiotic stresses on plant proteome and metabolome changes. Acta Physiol. Plant 2014, 36, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, X.M.; Zhou, Q.; Luo, F.; Wei, B.D.; Wang, Y.J.; Sun, H.J.; Zhao, Y.B.; Ji, S.J. Transcriptome analysis of harvested bell peppers (Capsicum annuum L.) in response to cold stress. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2019, 139, 314–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, B.; Zhang, B.; Ding, L.; Li, P.Y.; Shen, L.; Zhang, J.X. Physiological change and transcriptome analysis of Chinese wild Vitis amurensis and Vitis vinifera in response to cold stress. Plant Mol. Biol. Report. 2020, 38, 478–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, D.F.; Ma, C.; Xue, L.; Li, Z.; Wang, C.; Lei, J.J.; Yuan, X.F. Transcriptome and de novo analysis of Rosa xanthina f. spontanea in response to cold stress. BMC Plant Biol. 2021, 21, 472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.L.; Qu, W.J.; Li, X.F. Experimental Guidance on Plant Physiology, 4th ed.; Higher Education Press: Beijing, China, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, X.C.; Tan, Q.L.; Hu, C.X.; Gan, Q.Q.; Yi, C.C. Effects of molybdenum on antioxidative enzymes in winter wheat under low temperature stress. Sci. Agric. Sin. 2006, 39, 952–959. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, J.; Zheng, X.; Yan, H.F.; Tang, X.H.; Xiong, J.; Wei, M.Z.; Qin, W.Z.; Li, W.L. Physiological responses of different potato varieties to cold stress at seedling stage. J. South. Agric. 2016, 47, 1837–1943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.X.; Mei, C.; Song, Q.N.; Wang, H.J.; Wu, S.Y.; Feng, R.Y. Evaluation on cold tolerance of six potato seedlings in tissue culture under low temperature stress. J. Shanxi Agric. Sci. 2021, 49, 1502–1506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raza, A.; Tabassum, J.; Kudapa, H.; Varshney, R.K. Can omics deliver temperature resilient ready-to-grow crops? Crit. Rev. Biotechnol. 2021, 41, 1209–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchholz, A.; Hurlebaus, J.; Wandrey, C.; Takors, R. Metabolomics: Quantification of intracellular metabolite dynamics. Biomol. Eng. 2002, 19, 5–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preti, G. Metabolomics comes of age? Scientist 2005, 19, 8–12. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, C.B.; Yang, H.Z.; Xu, Q.J.; Wang, Y.L.; Sang, Z.; Yuan, H.J. Comparative metabolomics analysis of the response to cold stress of resistant and susceptible Tibetan hulless barley (Hordeum distichon). Phytochemistry 2020, 174, 112346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, P.; Li, Y.X.; Cui, C.K.; Huo, Y.R.; Lu, G.Q.; Yang, H.Q. Proteomic and metabolic profile analysis of low-temperature storage responses in Ipomoea batata Lam. tuberous roots. BMC Plant Biol. 2020, 20, 435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, S.G.; Cui, M.; Cai, Y.L.; Xue, A.; Hao, Y.B.; Huang, X.Y.; Liu, L.H.; Luo, L.P. Metabolomic analysis of chilling response in rice (Oryza sativa L.) seedlings by extractive electrospray ionization mass spectrometry. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2020, 180, 104231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Sui, N.; Lin, L.; Yang, Z.; Zhang, Y.H. Transcriptomic profiling revealed genes involved in response to cold stress in maize. Funct. Plant Biol. 2019, 46, 830–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Jiang, C.J.; Ren, J.Y.; Dong, J.L.; Shi, X.L.; Zhao, X.H.; Wang, X.G.; Wang, J.; Zhong, C.; Zhao, S.L.; et al. An advanced lipid metabolism system revealed by transcriptomic and lipidomic analyses plays a central role in peanut cold tolerance. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehmood, S.S.; Lu, G.Y.; Luo, D.; Hussain, M.A.; Raza, A.; Zafar, Z.; Zhang, X.K.; Cheng, Y.; Zou, X.L.; Lv, Y. Integrated analysis of transcriptomics and proteomics provides insights into the molecular regulation of cold response in Brassica napus. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2021, 187, 104480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, J.J.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, J.F.; Liu, P.P.; Chen, X.; Li, Z.F.; Xu, Y.L.; Lu, P.; Cao, P.J. Integrated transcriptomics and metabolomics analysis to characterize cold stress responses in Nicotiana tabacum. BMC Genom. 2017, 18, 496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Zhou, M.; Xu, K.; Li, J.H.; Li, S.S.; Zhang, S.H.; Yang, X.J. Integrated transcriptomics and metabolomics analyses provide insights into cold stress response in wheat. Crop J. 2019, 7, 857–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.X.; Liu, C.; Li, M.D.; Li, Y.M.; Yan, Z.H.; Feng, G.J.; Liu, D.J. Integrated transcriptomics and metabolomics analysis reveals key regulatory network that response to cold stress in common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.). BMC Plant Biol. 2023, 23, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.L. Identification of Cold Hardiness Related Phenotypes and Analysis of Characteristic Metabolites in Eight Potato Genotypes. Master’s Thesis, Huazhong Agricultural University, Wuhan, China, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, H.J.; Wang, X.Y.; Wu, X.; Yuan, L.; Zhao, Q.B.; Gao, J.L.; Guo, L.; Zhu, G.T. Transcriptome analysis of wild potato species S. commersonii under low temperature. J. Yunnan Norm. Univ. (Nat. Sci. Ed.) 2024, 44, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kou, S.; Chen, L.; Tu, W.; Scossa, F.; Wang, Y.M.; Liu, J.; Fernie, A.R.; Song, B.T.; Xie, C.H. The arginine decarboxylase gene ADC1, associated to the putrescine pathway, plays an important role in potato cold-acclimated freezing tolerance as revealed by transcriptome and metabolome analyses. Plant J. 2018, 96, 1283–1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bao, Y.F.; Shen, X.C.; Wang, F. The research progress and development prospects of biosynthesis, structure activity relationship and biological activity of caffeic acid and its main types of derivatives. Nat. Prod. Res. Dev. 2018, 30, 1825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, L.J.; Dong, C.; Liu, Y.P.; Zhao, A.J.; Zhang, Y.L.; Li, H.; Chen, X.Y. Transcription-associated metabolomic profiling reveals the critical role of frost tolerance in wheat. BMC Plant Biol. 2022, 22, 333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zheng, Z.Z.; Zhou, Y.; Yang, S.L.; Su, W.; Guo, H.; Ye, G.J.; Wang, J. Metabolome and transcriptome analyses reveal molecular responses of two potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) cultivars to cold stress. Front. Plant Sci. 2025, 16, 1543380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, S. Native RNA-sequencing throws its hat into the transcriptomics ring. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2018, 43, 225–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, Q.Q.; Luo, X.B.; Li, F.; Luo, C. Research progress on cold resistance of potato. Plant Physiol. J. 2021, 57, 1171–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, J.X.; Hou, L.X.; Bao, H.H.; Wang, X.M.; Zheng, H.J.; Zhu, G.T.; Guo, L. Effects of low temperature stress on physiological indexes related to cold resistance of potato seedlings. J. Yunnan Norm. Univ. (Nat. Sci. Ed.) 2022, 42, 20–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chobot, V.; Hadacek, F.; Bachmann, G.; Weckwerth, W.; Kubicova, L. Pro- and antioxidant activity of three selected flavan type flavonoids: Catechin, eriodictyol and taxifolin. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016, 17, 1986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, K.; Zhang, Z.P.; Ding, L.; Chen, Y.R.; Zhang, X.Y. Advances in biosynthesis of dihydroquercetin. China Biotechnol. 2024, 44, 126–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rice-Evans, C.A.; Miller, N.J.; Paganga, G. Structure-antioxidant activity relationships of flavonoids and phenolic acids. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 1996, 20, 933–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larson, R.A. Naturally Occurring Antioxidants, 1st ed.; CRG Press LLC: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 1997; Volume 3, 195p. [Google Scholar]

- Pietta, P.G. Flavonoids as antioxidants. J. Nat. Prod. 2000, 63, 1035–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, B.; Kotani, A.; Arai, K.; Kusu, F. Estimation of the antioxidant activities of flavonoids from their oxidation potentials. Anal. Sci. 2001, 17, 599–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farkas, O.; Jakus, J.; Heberger, K. Quantitative structure - antioxidant activity relationships of flavonoid compounds. Molecules 2004, 9, 1079–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, S.H.; Fang, J.B.; Lin, M.M.; Hu, C.G.; Qi, X.J.; Chen, J.Y.; Zhong, Y.P.; Muhammad, A.; Li, Z.; Li, Y.K. Comparative metabolomic and transcriptomic studies reveal key metabolism pathways contributing to freezing tolerance under cold stress in Kiwifruit. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 628969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.H.; Tian, Q.H.; Wang, Z.Y.; Li, J.; Liu, S.Y.; Chang, R.F.; Chen, H.; Liu, G.J. Integrated analysis of transcriptomics and metabolomics of peach under cold stress. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1153902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, T.; Zhang, J.G.; Cao, J.S.; Li, X.; Li, S.N.; Liu, C.H.; Wang, L.S. Metabolic insight into cold stress response in two contrasting maize lines. Life 2022, 12, 282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferri, M.; Happel, A.; Zanaroli, G.; Bertolini, M.; Chiesa, S.; Commisso, M.; Guzzo, F.; Tassoni, A. Advances in combined enzymatic extraction of ferulic acid from wheat bran. New Biotechnol. 2019, 56, 38–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.X.; Ma, Y.; Ma, X.J.; Meng, S.H.; Zhao, J.S.; Zhang, D.Q.; Huang, X.Q.; Wang, T.L.; Li, T.G. Research Progress in the Preparation of Ferulic Acid and Its Complexes. Food Res. Dev. 2025, 46, 176–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Chen, F.; Li, J.M. Research Progress on 2-phenylethanol Biosynthesis in Plants. Acta Hortic. Sin. 2010, 37, 1690–1694. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, S.F.; Yang, Z.F.; Cai, Y.T.; Zheng, Y.H. Fatty acid composition and antioxidant system in relation to susceptibility of loquat fruit to chilling injury. Food Chem. 2011, 127, 1777–1783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gwak, Y.; Hwang, Y.S.; Wang, B.B.; Kim, M.J.; Jeong, J.; Lee, C.G.; Hu, Q.; Han, D.X.; Jin, E.S. Comparative analyses of lipidomes and transcriptomes reveal a concerted action of multiple defensive systems against photooxidative stress in Haematococcus pluvialis. J. Exp. Bot. 2014, 65, 4317–4334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Q.; Zheng, Q.; Shen, W.Y.; Cram, D.; Fowler, D.B.; Wei, Y.D.; Zou, J.T. Understanding the biochemical basis of temperature-induced lipid pathway adjustments in plants. Plant Cell. 2015, 27, 86–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barrero-Sicilia, C.; Silvestre, S.; Haslam, R.P.; Michaelson, L.V. Lipid remodelling: Unravelling the response to cold stress in Arabidopsis and its extremophile relative Eutrema salsugineum. Plant Sci. 2017, 263, 194–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noblet, A.; Leymarie, J.; Bailly, C. Chilling temperature remodels phospholipidome of Zea mays seeds during imbibition. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 8886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.L.; Xin, W.; Wang, Y.L.; Zhang, D.Z.; Wang, J.G.; Zheng, H.L.; Yang, L.M.; Nie, S.J.; Zou, D.T. An integrated analysis of the rice transcriptome and lipidome reveals lipid metabolism plays a central role in rice cold tolerance. BMC Plant Biol. 2022, 22, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.P.; Gui, Z.H.; Huang, Y.X.; Yang, H.Z.; Luo, J.; Zeng, X.Q. Integrated transcriptomics and metabolomics analyses provide insights into qingke in response to cold stress. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2023, 71, 18345–18358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.J.; Yang, A.F.; Zhang, X.C.; Gao, F.; Zhang, J.R. Improving freezing tolerance of transgenic tobacco expressing sucrose: Sucrose 1-fructosyltransferase gene from Lactuca sativa. Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult. 2007, 89, 37–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Lin, L.; Zhang, Y.H.; Sui, N. ZmMYB31, a R2R3-MYB transcription factor in maize, positively regulates the expression of CBF genes and enhances resistance to chilling and oxidative stress. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2019, 46, 3937–3944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, Y.Y.; Zhou, L.J.; Geng, L.F.; Jiang, L.; Sui, Y.J.; Luo, L.; Pan, H.T.; Zhang, Q.X.; Yu, C. Genome-wide identification of the bHLH transcription factor family in Rosa persica and response to low-temperature stress. PeerJ 2024, 12, e16568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.G.; Dong, B.; Wang, N.N.; Zheng, Z.F.; Yang, L.Y.; Zhong, S.W.; Fang, Q.; Xiao, Z.; Zhao, H.B. A WRKY transcription factor PmWRKY57 from Prunus mume improves cold tolerance in Arabidopsis thaliana. Mol. Biotechnol. 2023, 65, 1359–1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Li, D.J.; Deng, Z. Advances in research of transcriptional regulatory network in response to cold stress in plants. Sci. Agric. Sin. 2014, 47, 3523–3533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raza, A.; Su, W.; Hussain, M.A.; Mehmood, S.S.; Zhang, X.K.; Cheng, Y.; Zou, X.L.; Lv, Y. Integrated analysis of metabolome and transcriptome reveals insights for cold tolerance in rapeseed (Brassica napus L.). Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 721681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Liu, Y.; Han, Z.K.; Chen, Y.N.; Huai, D.X.; Kang, Y.P.; Wang, Z.H.; Yan, L.Y.; Jiang, H.F.; Lei, Y.; et al. Integrated transcriptomics and metabolomics analysis reveal key metabolism pathways contributing to cold tolerance in peanut. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 752474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, S.X.; Zhang, Y.; Guo, K.L.; Wang, L.; Yuan, H.Y. Cloning and expression analysis of a flavonol synthase gene from Camellia sinensis. Plant Physiol. Commun. 2009, 45, 1093–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Gene ID | Forward Primer (5′-3′) | Reverse Primer (5′-3′) |

|---|---|---|

| Soltu.Atl.01_0G003920 | CACAGGCACAACTTGCACTC | GACGCCATCGAACCTGAGAA |

| Soltu.Atl.01_4G029640 | CGAATCATCTTCAGAAGCTTTCAT | ACTGCAGCTTGGCAAGTAGT |

| Soltu.Atl.02_0G004140 | TCCCCTGCTAATTCATGGCG | TCACACACTTGGGATTCAGCA |

| Soltu.Atl.02_3G027630 | CCTTGGCTGCTGATTCCAGA | AAGCAGTGTGATGCCTTCCA |

| Soltu.Atl.03_3G020110 | GTGCTGGAGTTGCAGTACCT | AGCTGAGTCTTCGACGTACC |

| Soltu.Atl.06_4G023280 | AGGTGCGAGTTAATGGTCCG | TGCTGGAACCGAGAAAACCA |

| Soltu.Atl.07_3G011990 | AGAGGCAGAGGAAAGTACACA | AAGCACTTGCAATTGGATCAC |

| Soltu.Atl.07_3G013810 | CAAATTCACTCGCACACGGC | AGCGTGCGTCAACAGTAAAG |

| StActin | AGATGCTTACGCTGGATGGAATGC | TTCCGGTGTGGTTGGATTCTGTTC |

| Preincubation (1 Cycle) | 2 Step Amplification (45 Cycle) | Melting (1 Cycle) | Cooling (1 Cycle) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 95 °C for 600 s | 95 °C for 10 s | 95 °C for 10 s | 37 °C for 30 s |

| Tm°C for 30 s | 65 °C for 60 s | ||

| 97 °C for 1 s |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, X.; Fang, G.; Ma, Y.; Su, W.; Yang, S.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, J. Integrated Metabolomics and Transcriptomics Analyses Reveal the Critical Role of Caffeic Acid in Potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) Cold Tolerance. Plants 2025, 14, 3447. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14223447

Li X, Fang G, Ma Y, Su W, Yang S, Zhou Y, Zhang Y, Wang J. Integrated Metabolomics and Transcriptomics Analyses Reveal the Critical Role of Caffeic Acid in Potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) Cold Tolerance. Plants. 2025; 14(22):3447. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14223447

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Xiang, Guonan Fang, Yongzhen Ma, Wang Su, Shenglong Yang, Yun Zhou, Yanping Zhang, and Jian Wang. 2025. "Integrated Metabolomics and Transcriptomics Analyses Reveal the Critical Role of Caffeic Acid in Potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) Cold Tolerance" Plants 14, no. 22: 3447. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14223447

APA StyleLi, X., Fang, G., Ma, Y., Su, W., Yang, S., Zhou, Y., Zhang, Y., & Wang, J. (2025). Integrated Metabolomics and Transcriptomics Analyses Reveal the Critical Role of Caffeic Acid in Potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) Cold Tolerance. Plants, 14(22), 3447. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14223447