Rolling Leaf 2 Controls Leaf Rolling by Regulating Adaxial-Side Bulliform Cell Number and Size in Rice

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Materials

2.2. Measurement of Leaf-Rolling Index and Agronomic Traits

2.3. Histology and Microscopic Observation

2.4. Genetic Analysis and Map-Based Cloning of RLL2

2.5. Phylogenetic Analysis

2.6. RNA Extraction and qRT-PCR

2.7. RNA-Seq Analysis

2.8. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

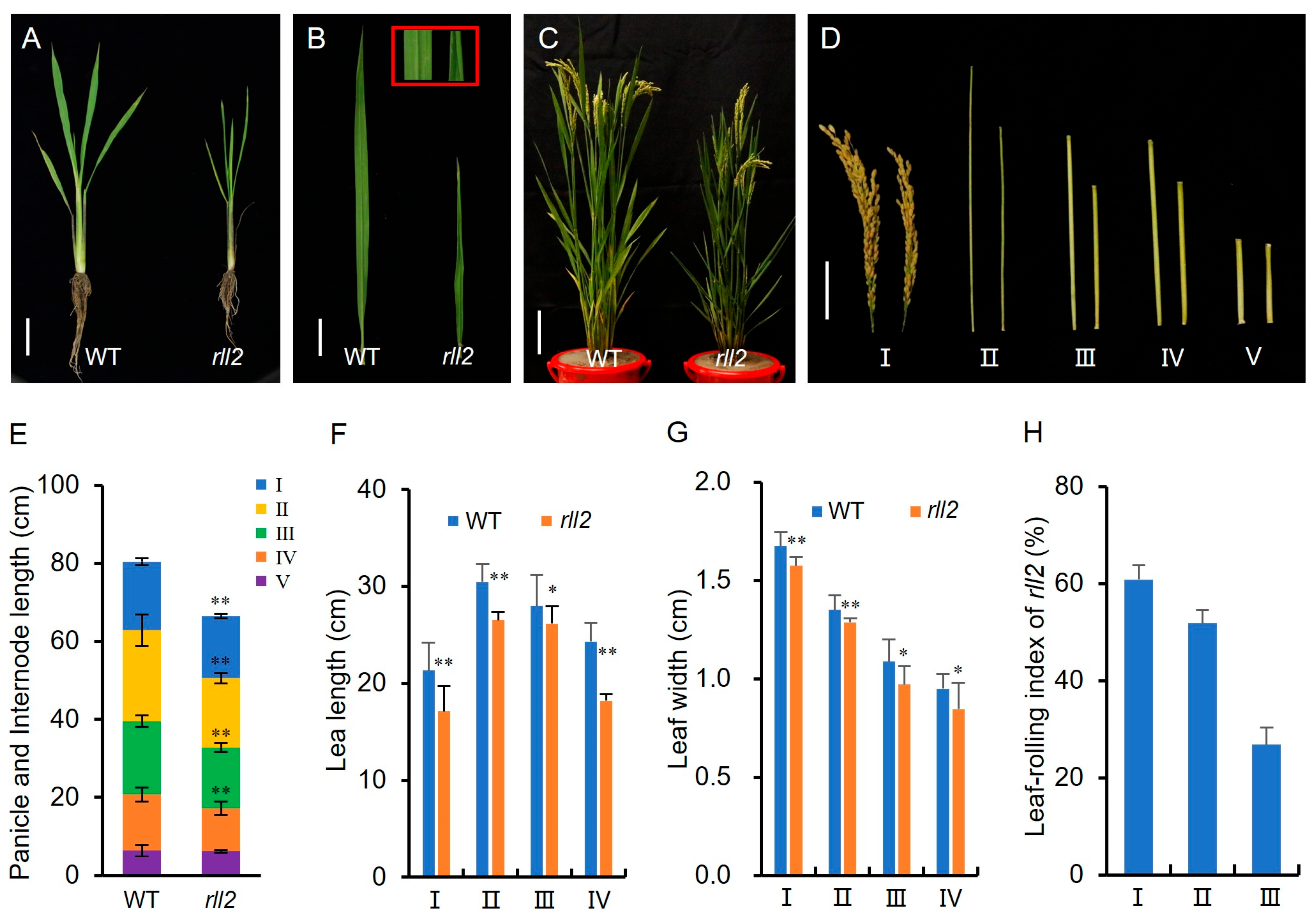

3.1. Phenotypic Characterization of the rll2 Mutant

3.2. Bulliform Cell Number and Size Are Increased in rll2

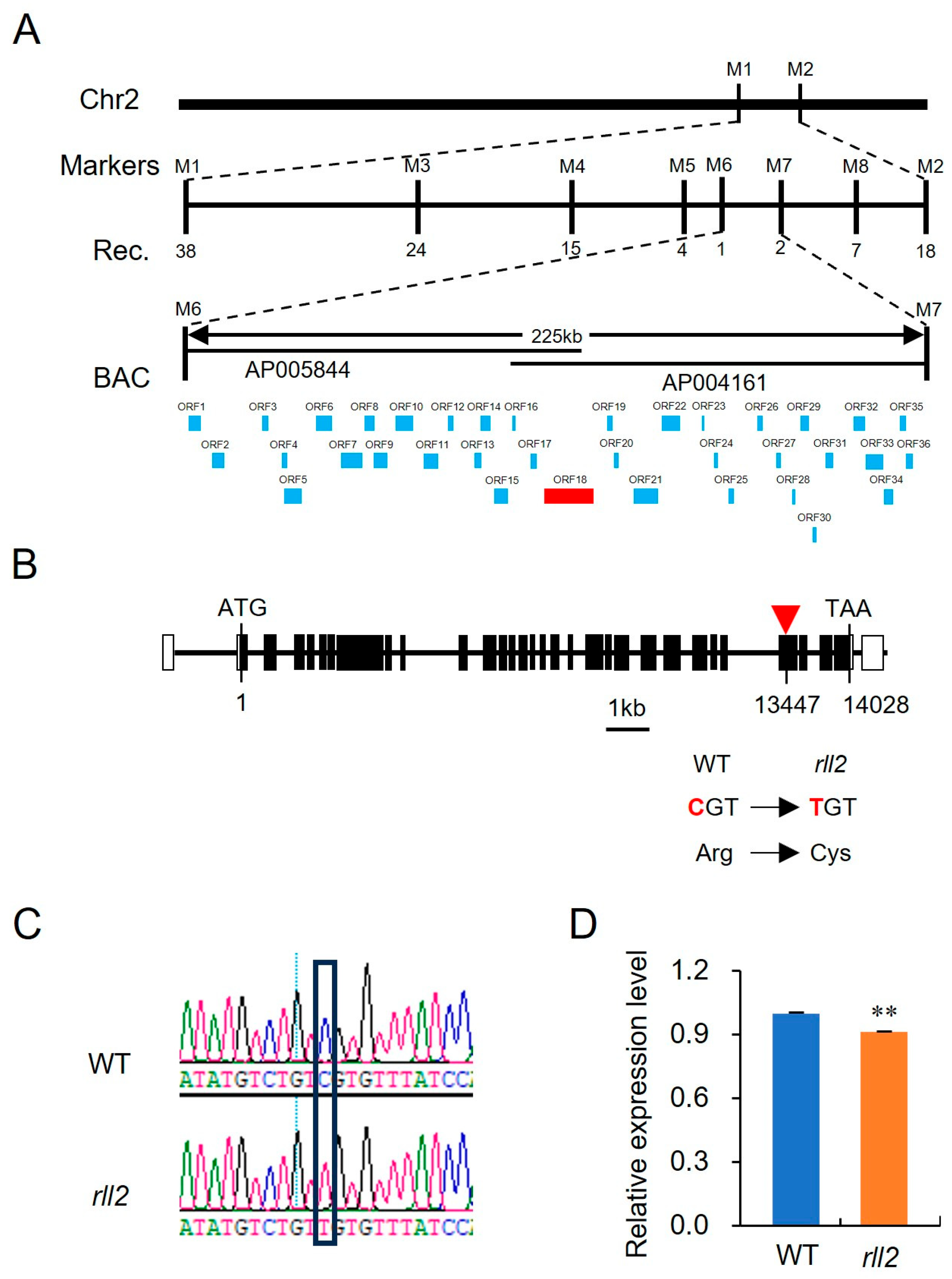

3.3. Map-Based Cloning of RLL2

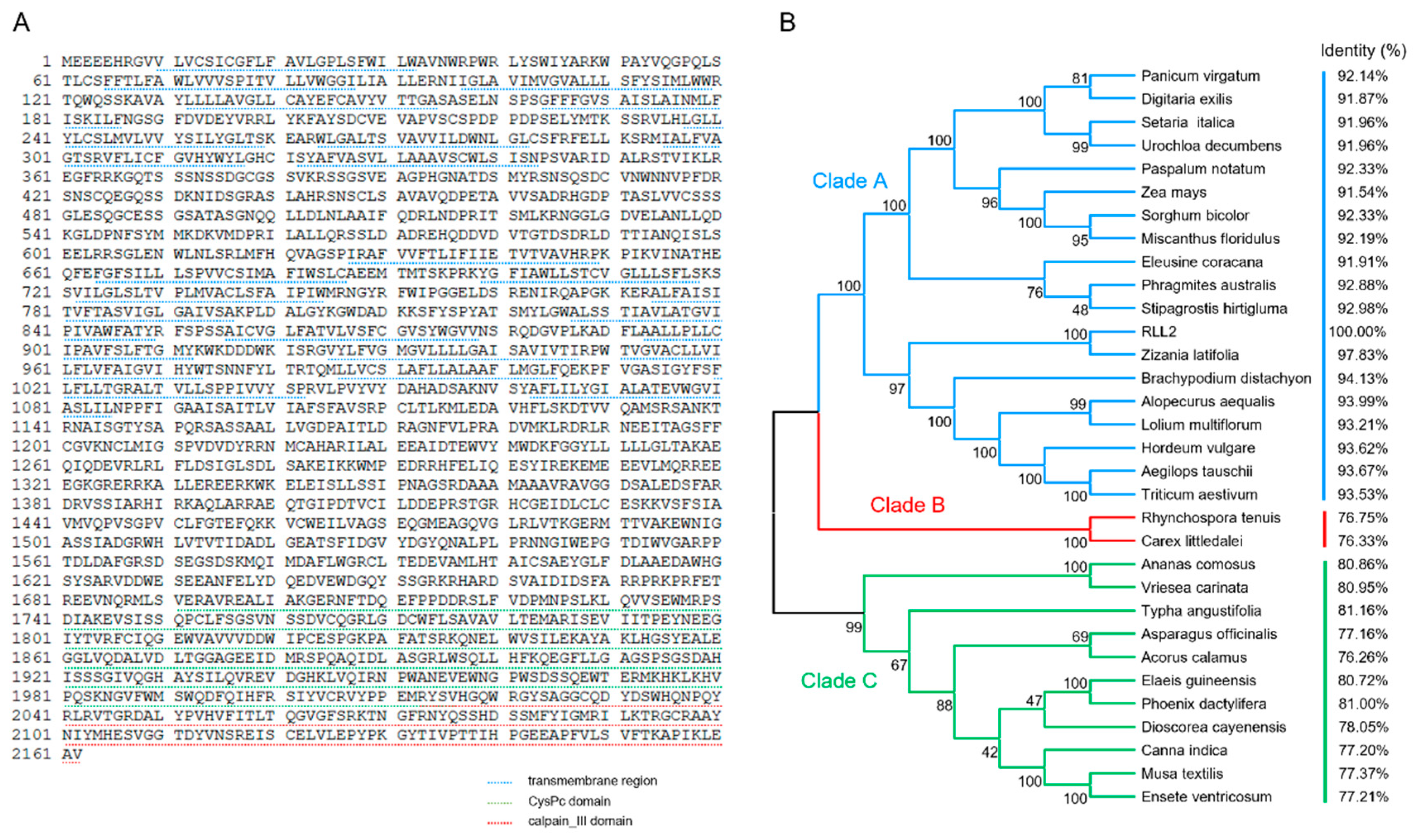

3.4. RLL2 Encodes a Conserved and Plant-Specific Protein

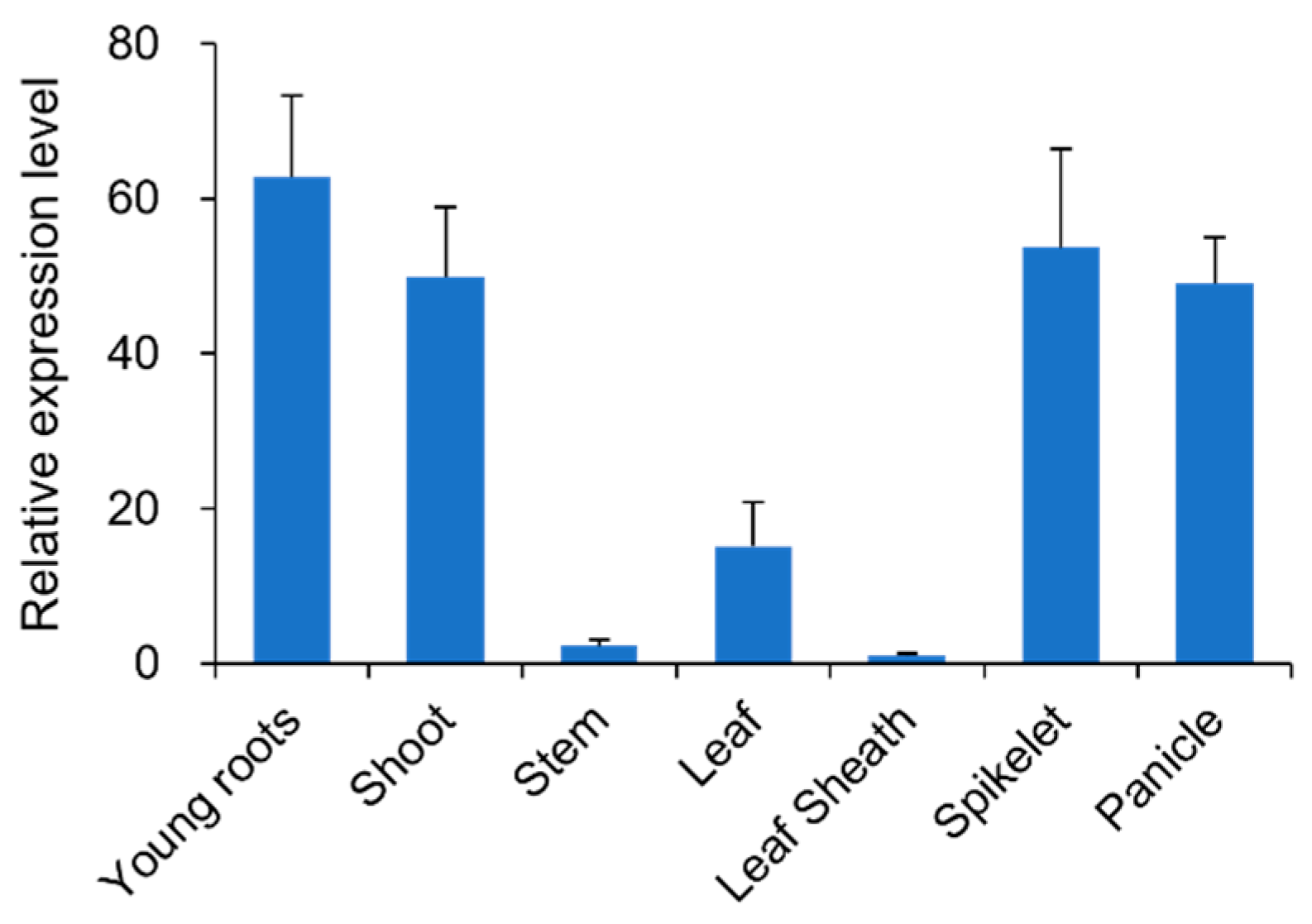

3.5. Expression Patterns of RLL2

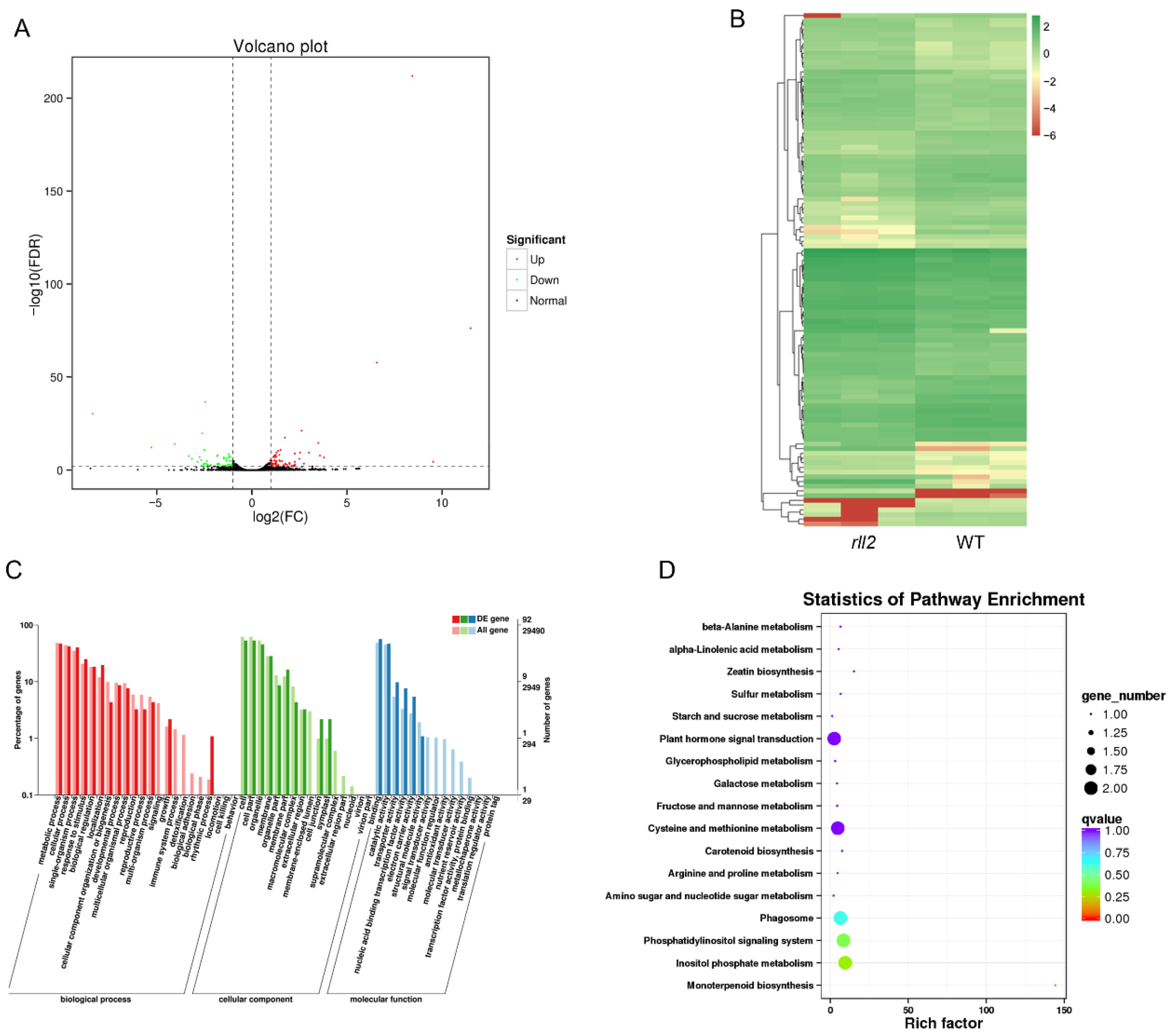

3.6. GO and KEGG Analyses of Rolling Leaf Regulation via RLL2

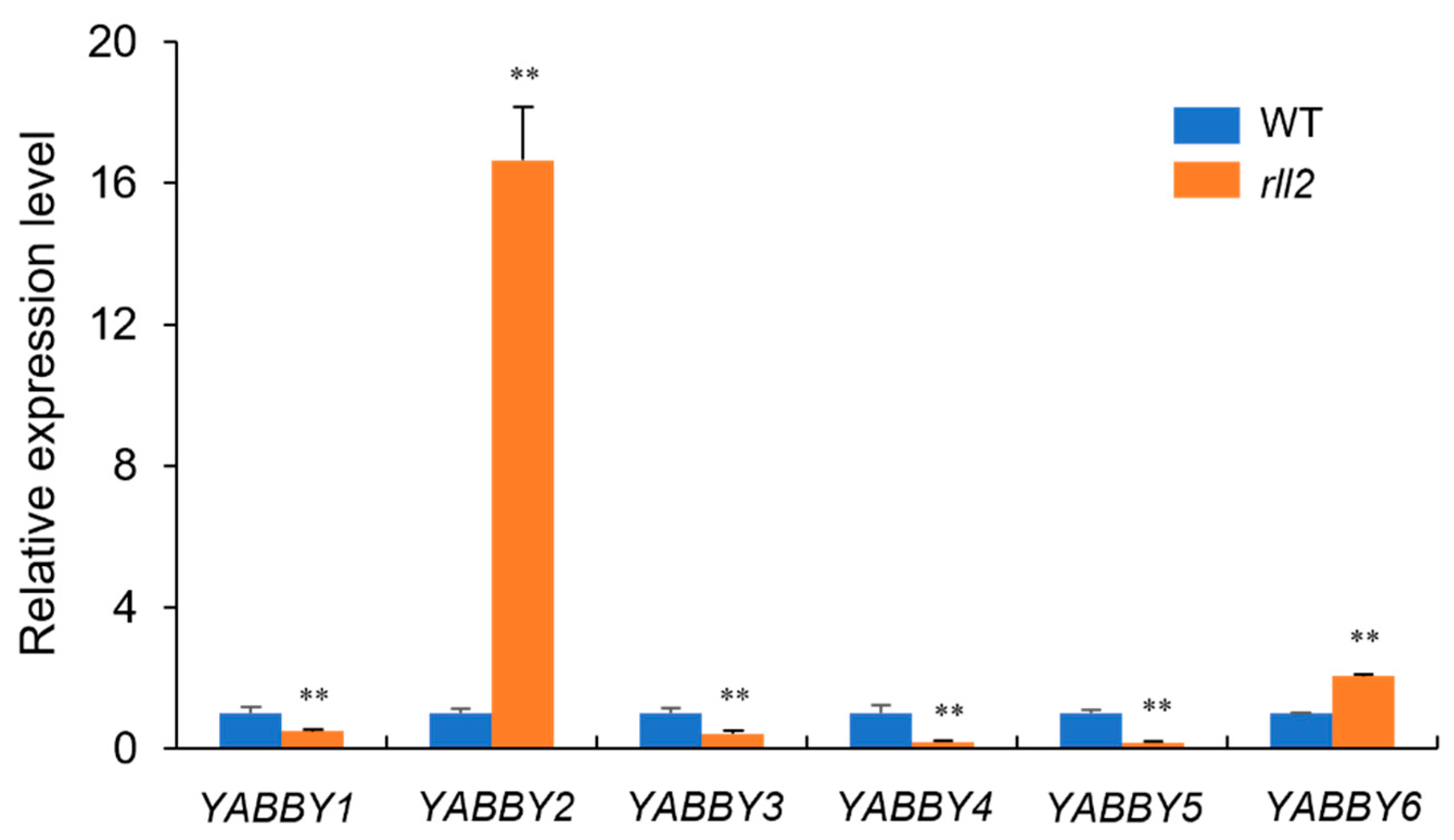

3.7. RLL2 Affects the Expression Levels of Leaf Development-Related Genes

4. Discussion

4.1. RLL2 Plays an Important Role in Regulating the Size and Number of Leaf Bulliform Cells in Rice

4.2. RLL2 Is a New Allelic Variant of ADL1

4.3. Transcription Factor Genes Participate in the Development of Leaves in RLL2

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gong, X.; Chen, J.; Chen, Y.; He, Y.; Jiang, D. Advancements in Rice Leaf Development Research. Plants 2024, 13, 904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Li, M.; Liu, K.; Tang, D.; Sun, M.; Li, Y.; Shen, Y.; Du, G.; Cheng, Z. Semi-Rolled Leaf2 modulates rice leaf rolling by regulating abaxial side cell differentiation. J. Exp. Bot. 2016, 67, 2139–2150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Xu, J.; Wang, L.; Zhou, M.; Nian, J.; Chen, M.; Lu, X.; Liu, X.; Wang, Z.; Cen, J.; et al. SEMI-ROLLED LEAF 10 stabilizes catalase isozyme B to regulate leaf morphology and thermotolerance in rice (Oryza sativa L.). Plant Biotechnol. J. 2023, 21, 819–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moulia, B. Leaves as shell structures: Double curvature, auto stresses, and minimal mechanical energy constraints on leaf rolling in grasses. J. Plant Growth Regul. 2000, 19, 19–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Kong, F.; Zhou, C. From genes to networks: The genetic control of leaf development. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2021, 63, 1181–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, F.; Guan, C.; Jiao, Y. Molecular mechanisms of leaf morphogenesis. Mol. Plant 2018, 11, 1117–1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, W.; Sun, J.; Xiao, Z.; Feng, P.; Zhang, T.; He, G.; Sang, X. Narrow and stripe leaf 2 regulates leaf width by modulating cell cycle progression in rice. Rice 2023, 16, 20–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasson, A.; Blein, T.; Laufs, P. Leaving the meristem behind: The genetic and molecular control of leaf patterning and morphogenesis. Comptes Rendus Biol. 2010, 333, 350–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, J.; Hake, S. How a leaf gets its shape. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2011, 14, 24–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.H.; Xu, Q.; Zhu, X.D.; Qian, Q.; Xue, H.W. SHALLOT-LIKE1 is a KANADI transcription factor that modulates rice leaf rolling by regulating leaf abaxial cell development. Plant Cell 2009, 21, 719–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, S.; Yan, C.J.; Zeng, X.H.; Yang, Y.C.; Fang, Y.W.; Tian, C.Y.; Sun, Y.W.; Cheng, Z.K.; Gu, M.H. ROLLED LEAF 9, encoding a GARP protein, regulates the leaf abaxial cell fate in rice. Plant Mol. Biol. 2008, 68, 239–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.J.; Wu, S.Y.; Jiang, L.; Wang, J.L.; Zhang, X.; Guo, X.P.; Wu, C.Y.; Wan, J.M. A detailed analysis of the leaf rolling mutant sll2 reveals complex nature in regulation of bulliform cell development in rice (Oryza sativa L.). Plant Biol. 2015, 17, 437–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, J.J.; Zhang, G.H.; Qian, Q.; Xue, H.W. Semi-rolled leaf 1 encodes a putative glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchored protein and modulates rice leaf rolling by regulating the formation of bulliform cells. Plant Physiol. 2012, 159, 1488–1500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.Q.; Zhang, M.J.; Gan, P.F.; Qiao, L.; Yang, S.Q.; Miao, H.; Wang, G.F.; Zhang, M.M.; Liu, W.T.; Li, H.F.; et al. CLD1/SRL1 modulates leaf rolling by affecting cell wall formation, epidermis integrity and water homeostasis in rice. Plant J. 2017, 92, 904–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Shi, Z.Y.; Li, L.; Shen, G.Z.; Wang, X.Q.; An, L.S.; Zhang, J.L. Overexpression of ACL1 (abaxially curled leaf 1) increased bulliform cells and induced abaxial curling of leaf blades in rice. Mol. Plant 2010, 3, 807–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Zhu, L.; Zeng, D.; Gao, Z.; Guo, L.; Fang, Y.; Zhang, G.; Dong, G.; Yan, M.; Liu, J.; et al. Identification and characterization of NARROW AND ROLLED LEAF 1, a novel gene regulating leaf morphology and plant architecture in rice. Plant Mol. Biol. 2010, 73, 283–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fujino, K.; Matsuda, Y.; Ozawa, K.; Nishimura, T.; Koshiba, T.; Fraaije, M.W.; Sekiguchi, H. NARROW LEAF 7 controls leaf shape mediated by auxin in rice. Mol. Genet. Genomics 2008, 279, 499–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, L.K.; Zhao, F.M.; Cong, Y.F.; Sang, X.; Du, Q.; Wang, D.; Li, Y.; Ling, Y.; Yang, Z.; He, G. Rolling-leaf14 is a 2OG-Fe (II) oxygenase family protein that modulates rice leaf rolling by affecting secondary cell wall formation in leaves. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2012, 10, 524–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hibara, K.; Obara, M.; Hayashida, E.; Abe, M.; Ishimaru, T.; Satoh, H.; Itoh, J.I.; Nagato, Y. The ADAXIALIZED LEAF 1 gene functions in leaf and embryonic pattern formation in rice. Dev. Biol. 2009, 334, 345–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Yang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Li, D.; Zhao, Y.; Li, Z.; Liu, Y.; Jiang, D.; Li, J.; Zhou, H. Overexpression of OsAGO1b induces adaxially rolled leaves by affecting leaf abaxial sclerenchymatous cell development in rice. Rice 2019, 12, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Xie, Q.; Gao, J.; Wang, W.; Sun, B.; Liu, B.; Zhu, H.; Peng, H.; Zhao, H.; Liu, C.; et al. Characterization of Rolled and Erect Leaf 1 in regulating leave morphology in rice. J. Exp. Bot. 2015, 66, 6047–6058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Zou, X.; Zhang, C.; Shao, Q.; Liu, J.; Liu, B.; Li, H.; Zhao, T. OsLBD3-7 overexpression induced adaxially rolled leaves in rice. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0156413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Long, Q.; Huang, J.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, K.; Zheng, M.; Sun, J.; Chen, H.; Chen, S.; et al. Overexpression of OsZHD1, a zinc finger homeodomain class homeobox transcription factor, induce abaxially curled and drooping leaf in rice. Planta 2014, 239, 803–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, R.H.; Li, S.B.; He, S.; Waßmann, F.; Yu, C.; Qin, G.; Schreiber, L.; Qu, L.J.; Gu, H. CFL1, a WW domain protein, regulates cuticle development by modulating the function of HDG1, a class IV homeodomain transcription factor, in rice and Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 2011, 23, 3392–3411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.Y.; Shen, A.; Xiong, W.; Sun, Q.L.; Luo, Q.; Song, T.; Li, Z.L.; Luan, W.J. Overexpression of OsHox32 results in pleiotropic effects on plant type architecture and leaf development in rice. Rice 2016, 9, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zou, L.P.; Sun, X.H.; Zhang, Z.G.; Liu, P.; Wu, J.X.; Tian, C.J.; Qiu, J.L.; Lu, T.G. Leaf rolling controlled by the homeodomain leucine zipper Class IV gene Roc5 in rice. Plant Physiol. 2011, 156, 1589–1602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, J.; Cui, X.; Teng, S.; Zhao, K.; Wang, Y.; Chen, Z.; Sun, X.; Wu, J.; Ai, P.; Quick, W.P.; et al. HD-ZIP IV gene Roc8 regulates the size of bulliform cells and lignin content in rice. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2020, 18, 2559–2572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, X.; Wang, J.; Mao, X.; Li, C.; Li, L.; Xue, Y.; He, L.; Jing, R. A locus controlling leaf rolling degree in wheat under drought stress identified by bulked segregant analysis. Plants 2022, 11, 2076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Stecher, G.; Suleski, M.; Sanderford, M.; Sharma, S.; Tamura, K. MEGA12: Molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 12 for adaptive and green computing. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2024, 41, msae263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livak, K.J.; Schmittgen, T.D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real time quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCT method. Methods 2001, 25, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.; Chen, X.; Wang, Z.; Wang, S.; Wang, Y.; Zhu, Q.; Li, S.; Xiang, C. Arabidopsis Enhanced Drought Tolerance1/HOMEODOMAIN GLABROUS11 confers drought tolerance in transgenic rice without yield penalty. Plant Physiol. 2013, 162, 1378–1391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grabherr, M.G.; Haas, B.J.; Yassour, M.; Levin, J.Z.; Thompson, D.A.; Amit, I.; Adiconis, X.; Fan, L.; Raychowdhury, R.; Zeng, Q. Trinity: Reconstructing a full-length transcriptome without a genome from RNA-Seq data. Nat. Biotechnol. 2011, 29, 644–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, M.Q.; Hu, Y.F.; Zhao, Y.; Liu, H.F.; Zhou, D.X. A WUSCHEL-LIKE HOMEOBOX gene represses a YABBY gene expression required for rice leaf development. Plant Physiol. 2007, 144, 380–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stahle, M.I.; Kuehlich, J.; Staron, L.; von Arnim, A.G.; Golz, J.F. YABBYs and the transcriptional corepressors LEUNIG and LEUNIG_HOMOLOG maintain leaf polarity and meristem activity in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 2009, 21, 3105–3118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarojam, R.; Sappl, P.G.; Goldshmidt, A.; Efroni, I.; Floyd, S.K.; Eshed, Y.; Bowman, J.L. Differentiating Arabidopsis shoots from leaves by combined YABBY activities. Plant Cell 2010, 22, 2113–2130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, W.; Toriba, T.; Ohmori, Y.; Yoshida, A.; Kawai, A.; Mayama-Tsuchida, T.; Ichikawa, H.; Mitsuda, N.; Ohme-Takagi, M.; Hirano, H.Y. The YABBY gene TONGARI-BOUSHI1 is involved in lateral organ development and maintenance of meristem organization in the rice spikelet. Plant Cell 2012, 24, 80–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, P.; Ali, A.; Han, B.; Wu, X. Current advances in molecular basis and mechanisms regulating leaf morphology in rice. Front. Plant Sci. 2018, 9, 1528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, L. Super-high yield hybrid rice breeding. Hybrid. Rice 1997, 12, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Inukai, S.; Kock, K.H.; Bulyk, M.L. Transcription factor–DNA binding: Beyond binding site motifs. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 2017, 27, 110–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Li, D.; Liu, X.; Ji, C.; Hao, L.; Zhao, X.; Li, X.; Chen, C.; Cheng, Z.; Zhu, L. OsMYB103L, an R2R3-MYB transcription factor, influences leaf rolling and mechanical strength in rice (Oryza sativa L.). BMC Plant Biol. 2014, 14, 158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckardt, N.A. YABBY genes and the development and origin of seed plant leaves. Plant Cell 2010, 22, 2103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, C.M.; Jun, J.H.; Fletcher, J.C. Control of Arabidopsis leaf morphogenesis through regulation of the YABBY and KNOX families of transcription factors. Genetics 2010, 186, 197–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toriba, T.; Harada, K.; Takamura, A.; Nakamura, H.; Ichikawa, H.; Suzaki, T.; Hirano, H.Y. Molecular characterization the YABBY gene family in Oryza sativa and expression analysis of OsYABBY1. Mol. Genet. Genomics 2007, 277, 457–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, H.L.; Xu, Y.Y.; Xu, Z.H.; Chong, K. A rice YABBY gene, OsYABBY4, preferentially expresses in developing vascular tissue. Dev. Genes. Evol. 2007, 217, 629–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamaguchi, T.; Nagasawa, N.; Kawasaki, S.; Matsuoka, M.; Nagato, Y.; Hirano, H.Y. The YABBY gene DROOPING LEAF regulates carpel specification and midrib development in Oryza sativa. Plant Cell 2004, 16, 500–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ogo, Y.; Itai, R.N.; Nakanishi, H.; Inoue, H.; Kobayashi, T.; Suzuki, M.; Takahashi, M.; Mori, S.; Nishizawa, N.K. Isolation and characterization of IRO2, a novel iron-regulated bHLH transcription factor in graminaceous plants. J. Exp. Bot. 2006, 57, 2867–2878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Li, L.; Ying, Y.; Wang, J.; Shao, J.F.; Yamaji, N.; Whelan, J.; Ma, J.F.; Shou, H. A transcription factor OsbHLH156 regulates Strategy II iron acquisition through localising IRO2 to the nucleus in rice. New Phytol. 2020, 225, 1247–1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, X.; Zhang, J.; Liu, W.; Yan, S.; Liu, Q.; Fu, H.; Zhao, J.; Huang, W.; Dong, J.; Zhang, S.; et al. The MKKK62-MKK3-MAPK7/14 module negatively regulates seed dormancy in rice. Rice 2019, 12, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haga, K.; Iino, M. Phytochrome-mediated transcriptional up-regulation of ALLENE OXIDE SYNTHASE in rice seedlings. Plant Cell Physiol. 2004, 45, 119–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pramanik, M.H.R.; Imai, R. Functional identification of a trehalose 6-phosphate phosphatase gene that is involved in transient induction of trehalose biosynthesis during chilling stress in rice. Plant Mol. Biol. 2005, 58, 751–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.; Zhang, H.; Li, Z.; Huang, T.; Akihiro, T.; Xu, J.; Xu, H.; Lin, F. An amino acid transporter-like protein (OsATL15) facilitates the systematic distribution of thiamethoxam in rice for controlling the brown planthopper. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2022, 20, 1888–1901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Mei, E.; Tian, X.; He, M.; Tang, J.; Xu, M.; Liu, J.; Song, L.; Li, X.; Wang, Z.; et al. OsMKKK70 regulates grain size and leaf angle in rice through the OsMKK4-OsMAPK6-OsWRKY53 signaling pathway. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2021, 63, 2043–2057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.H.; Choi, D. Characterization of genes encoding ABA 8′-hydroxylase in ethylene-induced stem growth of deepwater rice (Oryza sativa L.). Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2006, 350, 685–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaish, M.W.; El-kereamy, A.; Zhu, T.; Beatty, P.H.; Good, A.G.; Bi, Y.M.; Rothstein, S.J. The APETALA-2-Like transcription factor OsAP2-39 controls key interactions between abscisic acid and gibberellin in Rice. PLoS Genet. 2010, 6, e1001098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosugi, S.; Ohashi, Y. PCF1 and PCF2 specifically bind to cis elements in the rice proliferating cell nuclear antigen gene. Plant Cell 1997, 9, 1607–1619. [Google Scholar]

- Dubouzet, J.G.; Sakuma, Y.; Ito, Y.; Kasuga, M.; Dubouzet, E.G.; Miura, S.; Seki, M.; Shinozaki, K.; Yamaguchi-Shinozaki, K. OsDREB genes in rice, Oryza sativa L., encode transcription activators that function in drought-, high-salt- and cold-responsive gene expression. Plant J. 2003, 33, 751–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, M.; Meng, X.; Song, X.; Zhang, D.; Kou, L.; Zhang, J.; Jing, Y.; Liu, G.; Liu, H.; Huang, X.; et al. Chilling-induced phosphorylation of IPA1 by OsSAPK6 activates chilling tolerance responses in rice. Cell Discov. 2022, 8, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, X.; Zhang, L.; Wei, X.; Zhou, Y.; Dai, Y.; Zhu, Z. OsJAZ13 negatively regulates jasmonate signaling and activates hypersensitive cell death response in rice. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 4379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, C.; Liang, G.; Chong, K.; Xu, Y. The COG1-OsSERL2 complex senses cold to trigger signaling network for chilling tolerance in japonica rice. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 3104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Z.; Zhang, Z.L.; Zou, X.; Huang, J.; Ruas, P.; Thompson, D.; Shen, Q.J. Annotations and functional analyses of the rice WRKY gene superfamily reveal positive and negative regulators of abscisic acid signaling in aleurone cells. Plant Physiol. 2005, 137, 176–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Bai, X.; Wang, X.; Chu, C. OsWRKY71, a rice transcription factor, is involved in rice defense response. J. Plant Physiol. 2007, 164, 969–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, R.; Ishimaru, Y.; Nakanishi, H.; Nishizawa, N.K. Role of the iron transporter OsNRAMP1 in cadmium uptake and accumulation in rice. Plant Signal. Behav. 2011, 6, 1813–1816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, R.; Zhao, W.; Meng, X.; Wang, M.; Peng, Y. Rice gene OsNAC19 encodes a novel NAC-domain transcription factor and responds to infection by Magnaporthe grisea. Plant Sci. 2007, 172, 120–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, T.; Nagano, A.J.; Nishizawa, N.K. Iron deficiency-inducible peptide-coding genes OsIMA1 and OsIMA2 positively regulate a major pathway of iron uptake and translocation in rice. J. Exp. Bot. 2021, 72, 2196–2211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, J.; Pei, W.; He, L.; Ma, B.; Tang, C.; Zhu, L.; Wang, L.; Zhong, Y.; Chen, G.; Wang, Q.; et al. ZmEREB92 plays a negative role in seed germination by regulating ethylene signaling and starch mobilization in maize. PLoS Genet. 2023, 19, e1011052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sperotto, R.A.; Ricachenevsky, F.K.; Duarte, G.L.; Boff, T.; Lopes, K.L.; Sperb, E.R.; Grusak, M.A.; Fett, J.P. Identification of up-regulated genes in flag leaves during rice grain filling and characterization of OsNAC5, a new ABA-dependent transcription factor. Planta 2009, 230, 985–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakata, M.; Kuroda, M.; Ohsumi, A.; Hirose, T.; Nakamura, H.; Muramatsu, M.; Ichikawa, H.; Yamakawa, H. Overexpression of a rice TIFY gene increases grain size through enhanced accumulation of carbohydrates in the stem. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2012, 76, 2129–2134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutha, L.R.; Reddy, A.R. Rice DREB1B promoter shows distinct stress-specific responses, and the overexpression of cDNA in tobacco confers improved abiotic and biotic stress tolerance. Plant Mol. Biol. 2008, 68, 533–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Ma, Y.Q.; Huang, X.X.; Mu, T.J.; Li, Y.J.; Li, X.K.; Liu, X.; Hou, B.K. Overexpression of OsUGT3 enhances drought and salt tolerance through modulating ABA synthesis and scavenging ROS in rice. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2021, 192, 104653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, E.; Bhatnagar, A.; Bhaskar, A.; Majee, S.M.; Kieffer, M.; Kepinski, S.; Khurana, P.; Khurana, J.P. Stress-induced F-Box protein-coding gene OsFBX257 modulates drought stress adaptations and ABA responses in rice. Plant Cell Environ. 2023, 46, 1207–1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philippe, R.; Courtois, B.; McNally, K.L.; Mournet, P.; El-Malki, R.; Paslier, M.C.L.; Fabre, D.; Billot, C.; Brunel, D.; Glaszmann, J.C.; et al. Structure, allelic diversity and selection of Asr genes, candidate for drought tolerance, in Oryza sativa L. and wild relatives. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2010, 121, 769–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Jing, W.; Xiao, L.; Jin, Y.; Shen, L.; Zhang, W. The rice high-affinity potassium transporter1;1 is involved in salt tolerance and regulated by an MYB-Type transcription factor. Plant Physiol. 2015, 168, 1076–1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, H.; Yoon, J.; Kim, H.Y.; Min, M.K.; Kim, J.A.; Choi, E.H.; Lan, W.Z.; Bae, Y.M.; Luan, S.; Cho, H.; et al. Unique features of two potassium channels, OsKAT2 and OsKAT3, expressed in rice guard cells. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e72541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.K.; Redillas, M.C.F.R.; Jung, H.; Choi, S.; Kim, Y.S.; Kim, J.K. A nitrogen molecular sensing system, comprised of the ALLANTOINASE and UREIDE PERMEASE 1 genes, can be used to monitor N status in rice. Front. Plant Sci. 2018, 9, 444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Guo, Z.; Gu, F.; Ke, S.; Sun, D.; Dong, S.; Liu, W.; Huang, M.; Xiao, W.; Yang, G.; et al. 4-coumarate-CoA ligase-like gene OsAAE3 negatively mediates the rice blast resistance, floret development and lignin biosynthesis. Front. Plant Sci. 2016, 7, 2041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, Y.; Shao, G.; Jiao, G.; Sheng, Z.; Xie, L.; Hu, S.; Tang, S.; Wei, X.; Hu, P. Targeted mutagenesis of POLYAMINE OXIDASE 5 that negatively regulates mesocotyl elongation enables the generation of direct-seeding rice with improved grain yield. Mol. Plant 2021, 14, 344–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlessi, M.; Mariotti, L.; Giaume, F.; Fornara, F.; Perata, P.; Gonzali, S. Targeted knockout of the gene OsHOL1 removes methyl iodide emissions from rice plants. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 17010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwamoto, M.; Baba-Kasal, A.; Kiyota, S.; Hara, N.; Takano, M. ACO1, a gene for aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylate oxidase: Effects on internode elongation at the heading stage in rice. Plant Cell Environ. 2010, 33, 805–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.Y.; Chung, Y.S.; Ok, S.H.; Lee, S.G.; Chung, W.I.; Kim, I.Y.; Shin, J.S. Characterization of the full-length sequences of phospholipase A2 induced during flower development. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1999, 1489, 389–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zan, X.; Zhou, Z.; Wan, J.; Chen, H.; Zhu, J.; Xu, H.; Zhang, J.; Li, X.; Gao, X.; Chen, R.; et al. Overexpression of OsHAD3, a member of HAD superfamily, decreases drought tolerance of rice. Rice 2023, 16, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, X.; Wu, J.; Chen, T.; Tie, W.; Chen, H.; Zhou, F.; Lin, Y. Loss-of-function mutation of rice SLAC7 decreases chloroplast stability and induces a photoprotection mechanism in rice. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2015, 57, 1063–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Traits | Wild Type | rll2 |

|---|---|---|

| Plant height (cm) | 80.4 ± 5.56 | 66.5 ± 1.02 ** |

| Tillering number | 9.6 ± 1.19 | 9.0 ± 0.76 ** |

| Primary branch number | 11.8 ± 1.16 | 8.6 ± 0.92 ** |

| Secondary branch number | 33.0 ± 2.00 | 24.6 ± 4.93 ** |

| Grain number per panicle | 182.0 ± 12.76 | 135.8 ± 23.36 ** |

| Grain length (mm) | 7.6 ± 0.37 | 7.4 ± 0.28 ** |

| Grain width (mm) | 3.5 ± 0.30 | 3.4 ± 0.30 ** |

| Grain thickness (mm) | 2.4 ± 0.03 | 2.4 ± 0.02 |

| Thousand-grain weight (g) | 28.6 ± 0.46 | 26.1 ± 0.36 ** |

| Cross Combination | F1 | F2 | χ2 (3:1) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wild-Type Phenotype | rll2 Phenotype | Wild-Type Phenotype | rll2 Phenotype | ||

| rll2/IR36 | 36 | 0 | 483 | 169 | 0.2945 |

| IR36/rll2 | 28 | 0 | 363 | 109 | 0.9153 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Leng, Y.-J.; Qiang, S.-Y.; Zhou, W.-Y.; Lu, S.; Tao, T.; Zhang, H.-C.; Cui, W.-X.; Zheng, Y.-F.; Liu, H.-B.; Yang, Q.-Q.; et al. Rolling Leaf 2 Controls Leaf Rolling by Regulating Adaxial-Side Bulliform Cell Number and Size in Rice. Plants 2025, 14, 3373. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14213373

Leng Y-J, Qiang S-Y, Zhou W-Y, Lu S, Tao T, Zhang H-C, Cui W-X, Zheng Y-F, Liu H-B, Yang Q-Q, et al. Rolling Leaf 2 Controls Leaf Rolling by Regulating Adaxial-Side Bulliform Cell Number and Size in Rice. Plants. 2025; 14(21):3373. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14213373

Chicago/Turabian StyleLeng, Yu-Jia, Shi-Yu Qiang, Wen-Yu Zhou, Shuai Lu, Tao Tao, Hao-Cheng Zhang, Wen-Xiang Cui, Ya-Fan Zheng, Hong-Bo Liu, Qing-Qing Yang, and et al. 2025. "Rolling Leaf 2 Controls Leaf Rolling by Regulating Adaxial-Side Bulliform Cell Number and Size in Rice" Plants 14, no. 21: 3373. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14213373

APA StyleLeng, Y.-J., Qiang, S.-Y., Zhou, W.-Y., Lu, S., Tao, T., Zhang, H.-C., Cui, W.-X., Zheng, Y.-F., Liu, H.-B., Yang, Q.-Q., Zhang, M.-Q., Yang, Z.-D., Xu, F.-X., Huan, H.-D., Wei, X., Cai, X.-L., Jin, S.-K., & Gao, J.-P. (2025). Rolling Leaf 2 Controls Leaf Rolling by Regulating Adaxial-Side Bulliform Cell Number and Size in Rice. Plants, 14(21), 3373. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14213373