The Resilience and Change in the Biocultural Heritage of Wild Greens Foraging Among the Arbëreshë Communities in Argolis and Corinthia Areas, Peloponnese, Greece

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

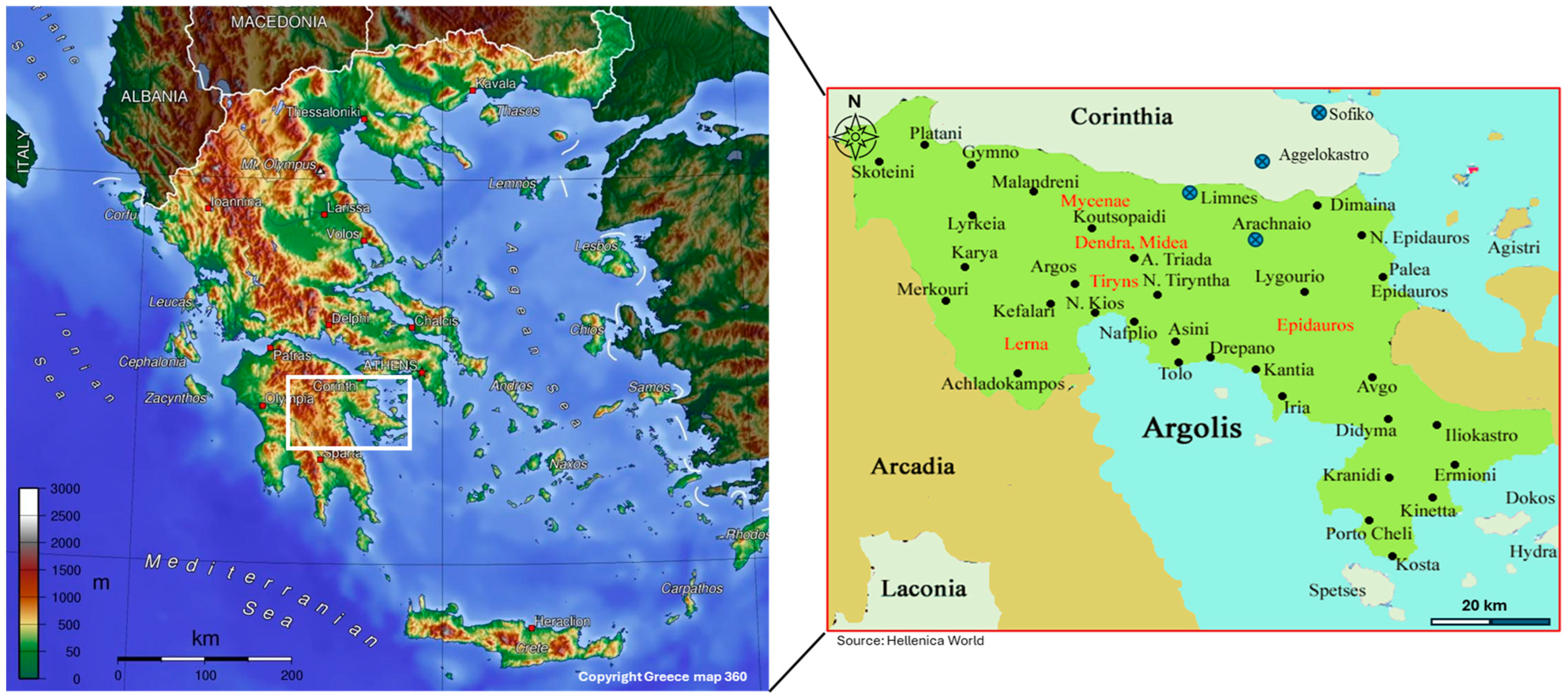

2.1. Study Area and Data Collection

2.2. Historical Reference Dataset (1970)

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

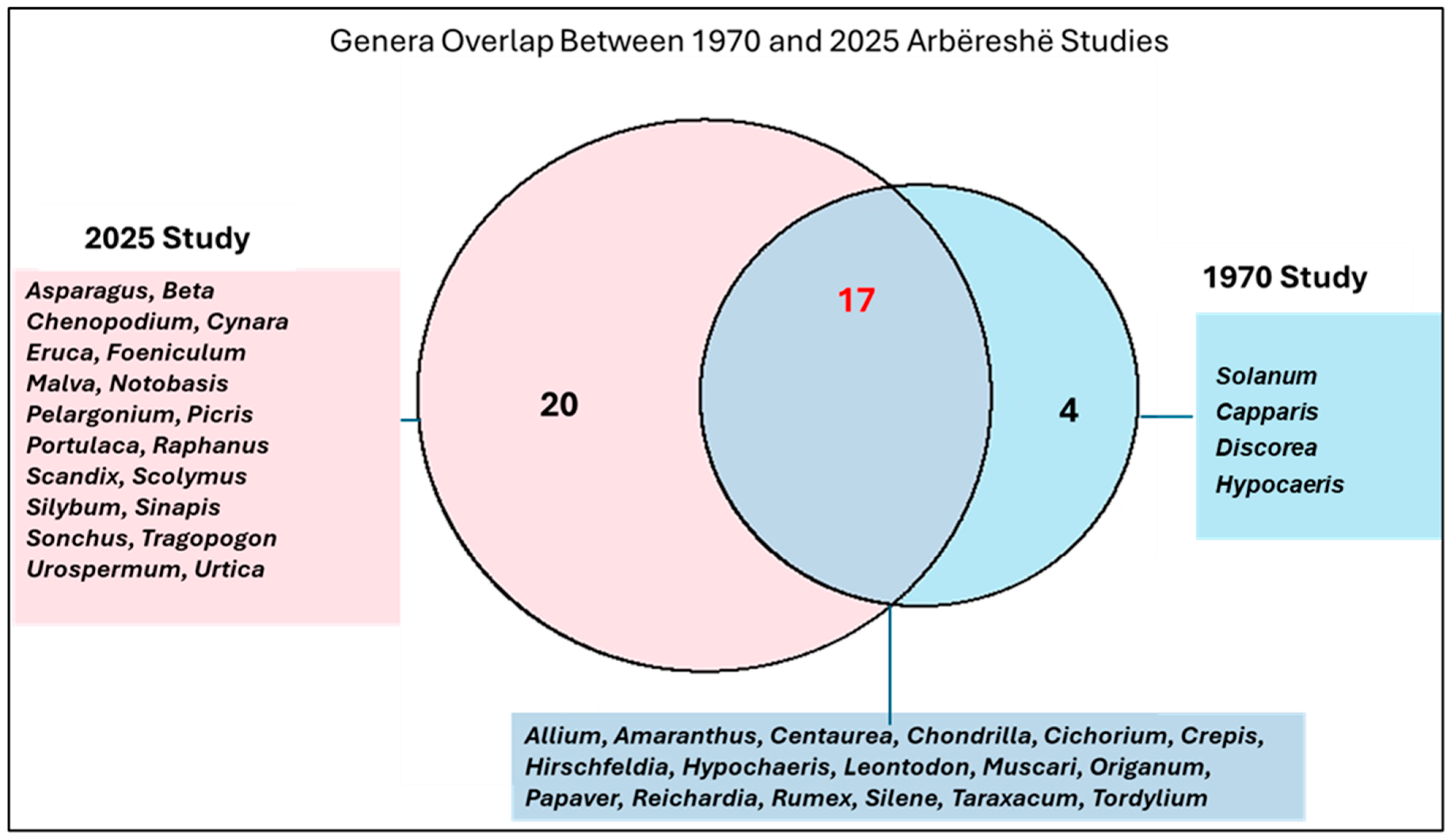

3.1. Botanical Diversity Change and Culinary Traditions Among the Greek Albanians

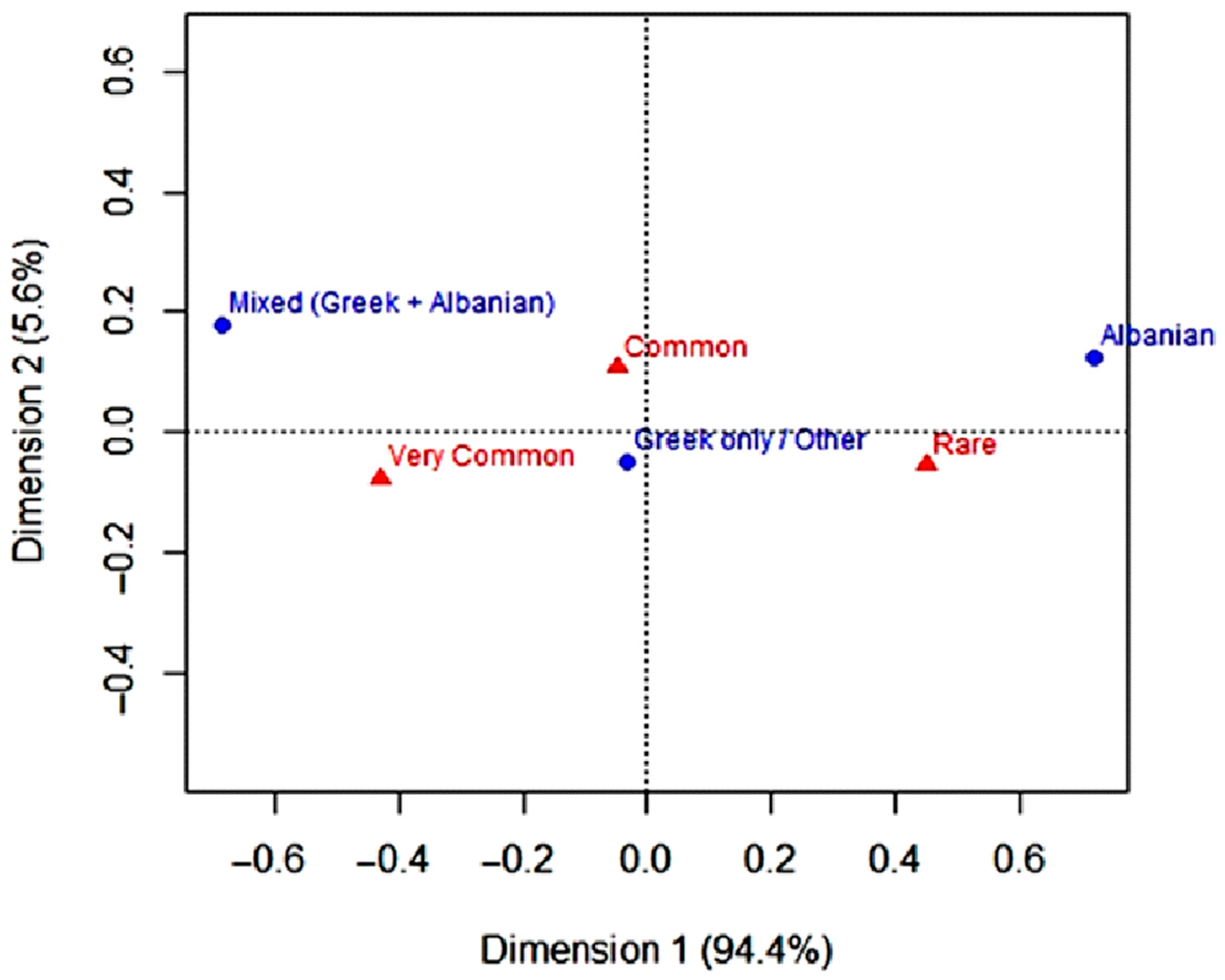

3.2. Ethnolinguistic Origins and Citation Frequency

4. Discussion

4.1. Botanical Diversity Change

4.2. Continuity and Transformation of Wild Greens-Centred Culinary Practices

4.3. Cultural Resilience and Linguistic Dynamics in Albanian Wild Greens Knowledge

4.4. Implications for Biocultural Conservation

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Koçollari, I. Arvanitët; Shtëpia Botuese Albin: Tirana, Albania, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Kahl, T.; Kahl, T. The Ethnicity of Aromanians after 1990: The Identity of a Minority That Behaves like a Majority. Ethnol. Balk. 2002, 6, 145–169. [Google Scholar]

- Lloshi, X. Handbuch der Südosteuropa Linguistik. 1999. Available online: https://archive.org/details/HandbuchDerSdosteuropaLinguistikXhevatLloshi1999 (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- Baltsiotis, L. The Muslim Chams of Northwestern Greece. Eur. J. Turk. Stud. Soc. Sci. Contemp. Turk. 2011, 8, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsitsipis, L. A Linguistic Anthropology of Praxis and Language Shift: Arvanítika (Albanian) and Greek in Contact; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Kahl, T. Aromanians in Greece: Minority or Vlach-Speaking Greeks; Slavica Verlag Kovač: Munich, Germany, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Grimes, B.F. Ethnologue: Languages of the World; SIL International: Dallas, TX, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Mandalà, M.; Knittlová, K. The Arbëresh: A Brief History of an Ancient Linguistic Minority in Italy. Kult. Stud. 2024, 23, 137–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çabej, E. Studime gjuhësore: Hyrje në historinë e gjuhës shqipe; Shtëpia Botuese Rilindja: Pristina, Kosovo, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Doja, A. Bektashism in Albania: Political History of a Religious Movement; AIIS: Tirana, Albania, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Fishman, J.A. Reversing Language Shift: Theoretical and Empirical Foundations of Assistance to Threatened Languages; Multilingual Matters: Clevedon, UK, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Grenoble, L.A.; Whaley, L.J. Saving Languages: An Introduction to Language Revitalization, 1st ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Pretty, J. The Intersections of Biological Diversity and Cultural Diversity: Towards Integration. Conserv. Soc. 2009, 7, 100–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmermann, P.; Tasser, E.; Leitinger, G.; Tappeiner, U. Effects of Land-Use and Land-Cover Pattern on Landscape-Scale Biodiversity in the European Alps. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2010, 139, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, N.J.; Turner, K.L. “Where Our Women Used to Get the Food”: Cumulative Effects and Loss of Ethnobotanical Knowledge and Practice; Case Study from Coastal British Columbia. Proc. Bot. 2008, 86, 103–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balée, W.L. (Ed.) Advances in Historical Ecology; Columbia University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2002; pp. 1–448. [Google Scholar]

- Berkes, F.; Colding, J.; Folke, C. Rediscovery of Traditional Ecological Knowledge as Adaptive Management. Ecol. Appl. 2000, 10, 1251–1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zent, S. Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK) and Biocultural Diversity: A Close-Up Look at Linkages, De-learning Trends, and Changing Patterns of Transmission. In Learning and Knowing in Indigenous Societies Today; Bates, P., Chiba, M., Kube, S., Nakashima, D., Eds.; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2009; pp. 39–57. [Google Scholar]

- Maffi, L. Linguistic, Cultural, and Biological Diversity. Annu. Rev. Anthropol. 2005, 34, 599–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sulaiman, N.; Alrhmoun, M.; Corvo, P.; Polesny, Z.; Pieroni, A. “L’Identità di Lungro”: Histo-cultural and Gender Perspectives of Yerba Maté Consumption among Arbëreshë Community in Lungro, Southern Italy. J. Ethnobiol. 2025; under review. [Google Scholar]

- Pieroni, A.; Vandebroek, I. Traveling Cultures and Plants: The Ethnobiology and Ethnopharmacy of Human Migrations; Berghahn Books: New York, NY, USA; Oxford, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Austin, P.K.; Sallabank, J. (Eds.) The Cambridge Handbook of Endangered Languages; Cambridge Handbooks in Language and Linguistics; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Nabhan, G. Cultures of Habitat: On Nature, Culture, and Story. Available online: https://www.lafeltrinelli.it/cultures-of-habitat-on-nature-libro-inglese-gary-paul-nabhan/e/9781887178969?srsltid=AfmBOoo_PxcB62HXl4e17Q5Qud0VcuT1xmSPx4ptXqbZTiZ_fm94gSTG (accessed on 15 November 2024).

- International Society of Ethnobiology (ISE). The ISE Code of Ethics. Available online: https://www.ethnobiology.net/what-we-do/core-programs/ise-ethics-program/code-of-ethics/ (accessed on 15 November 2024).

- Strid, A. Atlas of the Hellenic Flora; Broken Hill Publishers: Nicosia, Cyprus, 2024; Volume 3. [Google Scholar]

- World Flora Online (WFO). World Flora Online. Published on the Internet. 2025. Available online: https://www.worldfloraonline.org/ (accessed on 15 November 2024).

- Sejdiu, S.H. Fjalorth etnobotanik i shqipes; Rilindja: Prishtinë, Kosovo, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Rey, R. New Challenges and Opportunities for Mountain Agri-Food Economy in South Eastern Europe. A Scenario for Efficient and Sustainable Use of Mountain Product, Based on the Family Farm, in an Innovative, Adapted Cooperative Associative System Horizon 2040. Procedia Econ. Financ. 2015, 22, 723–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alrhmoun, M.; Sulaiman, N.; Pieroni, A. What Drives Herbal Traditions? The Influence of Ecology and Cultural Exchanges on Wild Plant Teas in the Balkan Mountains. Land 2024, 13, 2146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pieroni, A.; Quave, C. Ethnobotany and Biocultural Diversities in the Balkans; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014; pp. 1–453. [Google Scholar]

- Łukasz, Ł. Changes in the Utilization of Wild Green Vegetables in Poland since the 19th Century: A Comparison of Four Ethnobotanical Surveys. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2010, 128, 395–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pieroni, A.; Sõukand, R.; Bussmann, R.W. The Inextricable Link Between Food and Linguistic Diversity: Wild Food Plants among Diverse Minorities in Northeast Georgia, Caucasus. Econ. Bot. 2020, 74, 379–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johns, T.; Sthapit, B.R. Biocultural Diversity in the Sustainability of Developing-Country Food Systems. Food Nutr. Bull. 2004, 25, 143–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johns, T.; Powell, B.; Maundu, P.; Eyzaguirre, P.B. Agricultural Biodiversity as a Link between Traditional Food Systems and Contemporary Development, Social Integrity and Ecological Health. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2013, 93, 3433–3442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albuquerque, U.P.; Cantalice, A.S.; Oliveira, D.V.; Oliveira, E.S.; dos Santos, E.B.; dos Santos, F.I.R.; Soldati, G.T.; da Silva Lima, I.; Silva, J.V.M.; Abreu, M.B.; et al. Why Is Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK) Maintained? An Answer to Hartel et al. (2023). Biodivers. Conserv. 2024, 33, 859–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes-García, V.; Broesch, J.; Calvet-Mir, L.; Fuentes-Peláez, N.; Mcdade, T.; Parsa, S.; Tanner, S.; Huanca, T.; Leonard, W.; Martinez-Rodriguez, M.-R. Cultural Transmission of Ethnobotanical Knowledge and Skills: An Empirical Analysis from an Amerindian Society. Evol. Hum. Behav. 2009, 30, 274–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandebroek, I.; Reyes-García, V.; Albuquerque, U.; Bussmann, R.; Pieroni, A. Local Knowledge: Who Cares? J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2011, 7, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pieroni, A.; Quave, C.L. Traditional Pharmacopoeias and Medicines among Albanians and Italians in Southern Italy: A Comparison. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2005, 101, 258–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chukwurah, G.O.; Okeke, F.O.; Isimah, M.O.; Enoguanbhor, E.C.; Awe, F.C.; Nnaemeka-Okeke, R.C.; Guo, S.; Nwafor, I.V.; Okeke, C.A. Cultural Influence of Local Food Heritage on Sustainable Development. World 2025, 6, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liuzzi, A. Old and New Minorities: The Case of the Arbëreshë Communities and the Albanian Immigrants in Southern Italy. Migr. Lett. 2016, 13, 258–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinton, L.; Hale, K. The Green Book of Language Revitalization in Practice; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2001; Available online: https://www.scirp.org/reference/referencespapers?referenceid=650391 (accessed on 5 August 2025).

- Ankli, A.; Sticher, O.; Heinrich, M. Yucatec Maya Medicinal Plants Versus Nonmedicinal Plants: Indigenous Characterization and Selection. Hum. Ecol. 1999, 27, 557–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazarea, V.D. Cultural Memory and Biodiversity; University of Arizona Press: Tucson, AZ, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Alexiades, M. Collecting Ethnobotanical Data: An Introduction to Basic Concepts and Techniques. In Selected Guidelines for Ethnobotanical Research: A Field Manual; New York Botanical Garden: Bronx, NY, USA, 1996; pp. 53–94. [Google Scholar]

- Berlin, B. Ethnobiological Classification: Principles of Categorization of Plants and Animals in Traditional Societies; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Pieroni, A.; Rexhepi, B.; Nedelcheva, A.; Hajdari, A.; Mustafa, B.; Kolosova, V.; Cianfaglione, K.; Quave, C.L. One Century Later: The Folk Botanical Knowledge of the Last Remaining Albanians of the Upper Reka Valley, Mount Korab, Western Macedonia. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2013, 9, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pardo-de-Santayana, M.; Tardío, J.; Morales, R. The gathering and consumption of wild edible plants in Spain: Ethnobotanical perspectives. Econ. Bot. 2005, 59, 387–403. [Google Scholar]

- Pieroni, A.; Quave, C.L. Traditional pharmacopoeias and the importance of wild plants: Comparative study in southern Italy. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2005, 99, 327–342. [Google Scholar]

- Quave, C.L.; Pieroni, A. Integrating folk plant knowledge and historical migration patterns: A case study of southern European minorities. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2015, 11, 37. [Google Scholar]

- Telci, I.; Öztürk, M.; Yılmaz, M.; Dirmenci, T.; Dönmez, A.A.; Koyuncu, M.; Kaya, E.; Yıldırım, E.; Çakılcıoğlu, U.; Öztürk, G.; et al. Ethnobotanical notes on wild edible plants in the Balkan region. Flora Mediterr. 2006, 16, 5–18. [Google Scholar]

- Bonet, M.A.; Valles, J. Use of wild edible plants in rural Mediterranean communities. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 2002, 53, 89–95. [Google Scholar]

- Pieroni, A.; Guarrera, P.M.; De Martino, E.; Sacchetti, G.; Toppino, L.; Sõukand, R.; Papp, N.; Kalle, R.; Cindrić, I.; Kovačić, S.; et al. Traditional ecological knowledge among Italian ethnic minorities: Wild food plants. Hum. Ecol. 2002, 30, 161–185. [Google Scholar]

- Tardío, J.; Pardo-de-Santayana, M.; Morales, R. Ethnobotanical review of wild edible plants in Europe. Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 2006, 152, 63–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinh Vien, T.T. Transnational Cultural Identity Through Everyday Practices of Foraging and Consuming Local Wild Plants Among Vietnamese Migrants in Japan and Germany. Cult. Agric. Food Environ. 2024, 46, 77–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunn, E.; Brown, C. Linguistic Ethnobiology 319 v 20. Cognitive Studies in Ethnobiology: What Can We Learn About the Mind as Well as Human Environmental Interaction? In Ethnobiology; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2011; pp. 319–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pieroni, A.; Price, L. Eating and Healing: Traditional Food as Medicine, 1st ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, L. Walking on Our Lands Again: Turning to Culturally Important Plants and Indigenous Conceptualizations of Health in a Time of Cultural and Political Resurgence. Int. J. Indig. Health 2020, 16, 165–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meighan, P.J. Indigenous language revitalization using TEK-nology: How can traditional ecological knowledge (TEK) and technology support intergenerational language transmission? J. Multiling. Multicult. Dev. 2022, 45, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Botanical Taxon or Taxa | Botanical Family | Voucher Specimen Number, Starts with UVVETBOT | Local Plant Name(s) | Used Parts | Culinary Prepraration(s) | Quotation Frequency |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Allium ampeloprasum L. | Amaryllidaceae | GRARB31 | Hudhra e egër, Skordo | Whole plants | Seasoning | R |

| Amaranthus blitum L. and possibly other Amaranthus spp. | Amaranthaceae | GRARB27 | Nena, Vlita | Tender aerial parts | Boiled | VC |

| Asparagus aphyllus L. | Asparagaceae | GRARB15 | Sfaraghia, Sparaghia, Srokalià, Sporaghie, Spuraghie | Shoots | Cooked | VC |

| Beta vulgaris L. | Amaranthaceae | GRARB34 | Spanakë e egër | Aerial parts | Lakra | C |

| Centaurea raphanina Sibth. & Sm. | Asteraceae | GRARB21 | Aginarkai, Agriaginara, Iannides e egër | Young whorls | Lakra | VC |

| Chenopodium album L. | Amaranthaceae | GRARB20 | Llabotë | Young aerial parts | Boiled | R |

| Cichorium intybus L. | Asteraceae | Radiki, Radiki e kuqe | Young aerial parts | Lakra | C | |

| Chondrilla juncea L. | Asteraceae | GRARB34 | Radiki | Young aerial parts | Lakra | R |

| Crepis bursifolia L. | Asteraceae | GRARB09 | Prikrada, Radiki | Young aerial parts | Lakra | VC |

| Crepis capillaris (L.) Wallr. | Asteraceae | Radiki e kuqe | Young whorls | Lakra | VC | |

| Cynara cardunculus L. | Asteraceae | Bukë e ljepuri, Iannides | Flower receptacles | Snack | C | |

| Eruca vesicaria (L.) Cav. | Brassicaceae | GRARB14 | Ruqë, Rukò | Young aerial parts | Salads | C |

| Foeniculum vulgare Mill. | Apiaceae | GRARB11 | Anitho, Marathee, Maratho, Sidra | Aerial parts | Seasoning, Lakra | VC |

| Hirschfeldia incana (L.) Lagr.-Foss. | Brassicaceae | GRARB04 | Ghinarides, Vruva | Young aerial parts | Lakra | VC |

| Leontodon spp. | Asteraceae | Glykoradiki | Young aerial parts | Lakra | C | |

| Malva sylvestris L. | Malvaceae | GRARB28 | Mallagë, Moaga, Molaga, Molocha | Leaves | Lakra | R |

| Leopoldia comosa (L.) Parl. | Asparagaceae | Vorvi, Vrovi, Vulvià, Vulvulli | Bulbs | Cooked, pickled | C | |

| Notobasis syriaca (L.) Cass. | Asteraceae | Glim e egër | Stems | Snack | R | |

| Origanum vulgare L. | Lamiaceae | Iasmo, Riganee | Flowering tops | Seasoning | C | |

| Papaver rhoeas L. | Papaveraceae | Paparuna, Lule e kuqe | Young whorls | Lakra | R | |

| Pelargonium graveolens L’Hér. | Geraniaceae | Arbarodisa | Leaves | Seasoning for jams and sweet preserves | C | |

| Helminthotheca echioides (L.) Holub | Asteraceae | Radiki | Young aerial parts | Lakra | C | |

| Pleurotus spp. (Fungi) | Pleurotaceae | Kepurdhë | Fruiting body | Cooked | C | |

| Portulaca oleracea L. | Portulacaceae | Adrakla, Andrakla | Aerial parts | Salads | C | |

| Raphanus spp. | Brassicaceae | Rapanidee | Aerial parts | Lakra | R | |

| Reichardia picroides (L.) Roth | Asteraceae | GRARB05 | Bukë ljepuri, Ghieres, Kochinida, Lagomomachi | Aerial parts | Salads, Lakra | VC |

| Rumex spp. | Polygonaceae | Lahana | Leaves | Lakra, dolmades | C | |

| Scandix pecten-veneris L. | Apiaceae | GRARB29 | Marillida, Miridis | Aerial parts | Lakra | C |

| Scolymus hispanicus L. | Asteraceae | Glim | Stems | Cooked | R | |

| Silene vulgaris (Moench) Garcke | Caryophyllaceae | Bathëz | Young shoots | Lakra | C | |

| Silybum marianum (L.) Gaertn. | Asteraceae | GRARB08 | Glim e gomari | Stems | Snack | R |

| Sinapis alba L. | Brassicaceae | GRARB12 | Chichibetra, Ghinarides, Piperica, Vruva, Vruvi | Young aerial parts | Lakra | VC |

| Sonchus oleraceus L. | Asteraceae | GRARB07 | Rreshellë, Rreshillë, Rushellë | Young aerial parts | Lakra | VC |

| Taraxacum campylodes G.E.Haglund | Asteraceae | GRARB33 | Radiki, Taraxako | Young whorls | Lakra | VC |

| Tordylium apulum L. | Apiaceae | GRARB13 | Kalkafidha, Kafkalithra, Marallida, Skarkalithra | Aerial parts | Lakra | VC |

| Tragopogon porrifolius L. | Asteraceae | GRARB25 | Bukë cjapi, Bukë qapi, Brokolë e egër | Young shoots | Salads, Lakra | C |

| Urospermum spp. | Asteraceae | Radiki | Young whorls | Lakra | R | |

| Urtica urens L. | Urticaceae | GRARB19 | Hith, Hithra | Leaves | Lakra | R |

| Linguistic Origin | Number of Taxa | Percentage (%) | Genera |

|---|---|---|---|

| Albanian only | 5 | 13.5% | Beta, Chenopodium, Silene, Sonchus, Urtica |

| Greek only | 23 | 62.16% | Arbutus, Capparis, Chondrilla, Foeniculum, Hirschfeldia, Leontodon, Muscari, Notobasis, Origanum, Pelargonium, Picris, Portulaca, Pyrus, Quercus, Raphanus, Rumex, Scandix, Scolymus, Silybum, Sinapis, Satureja, Taraxacum, Tordylium |

| Hybrid (Albanian and Greek) | 9 | 24.32% | Amaranthus, Allium, Centaurea, Crepis, Cynara, Eruca, Malva, Papaver, Reichardia, Tragopogon |

| Quotation Frequency | Number of Genera | Percentage (%) | Genera (List) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Common (C) | 14 | 37.8% | Beta, Cichorium, Cynara, Eruca, Leontodon, Muscari, Origanum, Pelargonium, Picris, Pleurotus, Portulaca, Rumex, Scandix, Silene, Tragopogon |

| Very Common (VC) | 12 | 32.4% | Amaranthus, Asparagus, Centaurea, Crepis (2), Foeniculum, Hirschfeldia, Reichardia, Sinapis, Sonchus, Taraxacum, Tordylium |

| Rare (R) | 11 | 29.7% | Allium, Chenopodium, Chondrilla, Malva, Notobasis, Papaver, Raphanus, Scolymus, Silybum, Urospermum, Urtica |

| Linguistic Origin | Very Common (VC) | Common (C) | Rare (R) | Total Genera |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Albanian only | Sonchus | Beta, Silene | Chenopodium, Urtica | 5 |

| Greek only | Asparagus, Foeniculum Hirschfeldia, Sinapis, Taraxacum, Tordylium | Cichorium, Leontodon, Muscari, Origanum, Pelargonium, Picris, Portulaca, Rumex, Scandix, | Chondrilla, Notobasis, Raphanus, Scolymus, Silybum, Urospermum | 25 |

| Hybrid (Albanian and Greek) | Amaranthus, Centaurea, Crepis, Reichardia, | Cynara, Eruca, Tragopogon | Allium, Malva, Papaver, | 10 |

| Total | 12 | 14 | 11 | 37 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Alrhmoun, M.; Sulaiman, N.; Bajrami, A.; Hajdari, A.; Pieroni, A.; Sõukand, R. The Resilience and Change in the Biocultural Heritage of Wild Greens Foraging Among the Arbëreshë Communities in Argolis and Corinthia Areas, Peloponnese, Greece. Plants 2025, 14, 3371. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14213371

Alrhmoun M, Sulaiman N, Bajrami A, Hajdari A, Pieroni A, Sõukand R. The Resilience and Change in the Biocultural Heritage of Wild Greens Foraging Among the Arbëreshë Communities in Argolis and Corinthia Areas, Peloponnese, Greece. Plants. 2025; 14(21):3371. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14213371

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlrhmoun, Mousaab, Naji Sulaiman, Ani Bajrami, Avni Hajdari, Andrea Pieroni, and Renata Sõukand. 2025. "The Resilience and Change in the Biocultural Heritage of Wild Greens Foraging Among the Arbëreshë Communities in Argolis and Corinthia Areas, Peloponnese, Greece" Plants 14, no. 21: 3371. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14213371

APA StyleAlrhmoun, M., Sulaiman, N., Bajrami, A., Hajdari, A., Pieroni, A., & Sõukand, R. (2025). The Resilience and Change in the Biocultural Heritage of Wild Greens Foraging Among the Arbëreshë Communities in Argolis and Corinthia Areas, Peloponnese, Greece. Plants, 14(21), 3371. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14213371