A Review of the Ethnomedicine, Phytochemistry, Pharmacology and Toxicological Studies on Ptaeroxylon obliquum (Thunb.) Radlk. (Rutaceae)

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

2.1. Inclusion Criteria

- Published and peer-reviewed articles, theses, and published abstracts on traditional uses, phytochemistry, secondary metabolites, and pharmacological activities of P. obliquum.

- English full-text articles or of other languages with options for translation to English.

- All available data that included P. obliquum, prior to 31 January 2025.

2.2. Exclusion Criteria

- Non-English articles lacking comprehensive translations were not included (articles that require translation from other languages to English).

- Articles containing details about the plant, but beyond the scope of this review.

3. Results

3.1. Traditional Uses

| Plant Part | Traditional Uses | References |

|---|---|---|

| Wood | Anthrax remedy for ticks in cattle | [31] |

| Bark | Bark is used to cure fevers, arthritis, and rheumatism. recreational and therapeutic remedy for headache relief. Cattle treatment for ticks | [22,23] |

| Leaves | Gastro-intestinal parasites, anthrax, myiasis, and wounds for goats. Crop diseases. For humans, it is used to treat headaches, hypertension, and toothaches. Rituals. | [11,12,23,25,30,32,33] |

| Bark, leaves | Myasis, wounds, removing body odor | [22,25,34,35] |

| Roots | Hypertension, arthritis, fever | [24,26] |

| Leaves, bark, stem, and roots | Livestock treatment for diarrhea, intestinal parasites, Newcastle, scabies, timpanism, wounds | [20] |

| Fodder | Contagious pleauropneumonia (cattle, goats) | [21] |

3.2. Phytochemistry

3.2.1. Phytochemical Analysis of P. obliquum

3.2.2. Essential Oils Identified from P. obliquum

3.2.3. Isolated and Tentatively Identified Compounds from P. obliquum

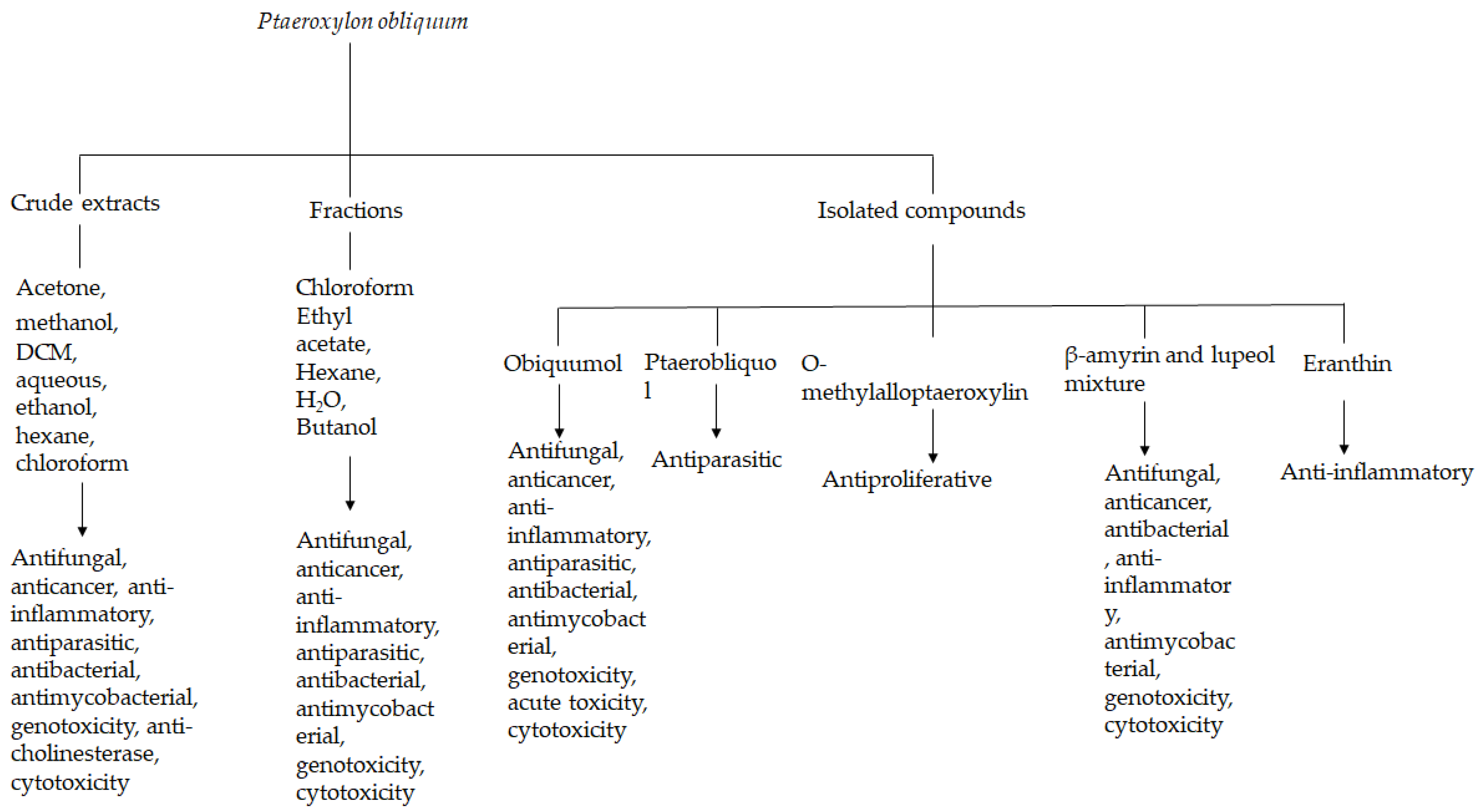

3.3. Pharmacological Activities

3.3.1. Antibacterial Activity

3.3.2. Antifungal Activity

3.3.3. Antimycobacterial Activities

3.3.4. Antioxidant Activities

3.3.5. Anti-Inflammatory Activities

3.3.6. Antiparasitic Activities

3.3.7. In Silico Studies

3.3.8. Anti-Cholinesterase Activities

3.3.9. In Vivo Studies

3.4. Toxicological Studies

3.4.1. Cytotoxicity

3.4.2. Genotoxicity

4. Discussion and Future Perspectives

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- McCabe, P.H.; McCrindle, R.; Murray, R.D.H. Constituents of sneezewood, Ptaeroxylon obliquum (Thunb.) Radlk. Part I. Chromones. J. Chem. Soc. C Org. 1967, 145–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulholland, D.A.; Kotsos, M.; Mahomed, H.A.; Randrianarivelojosia, M. The chemistry of the Ptaeroxylaceae. Niger. J. Nat. Prod. Med. 1999, 3, 15–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liau, S.S. A chemotaxonomic study of the Rutales of Scholz. Master’s Thesis, McGill University, Montreal, QC, Canada, 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Pennington, T.D.; Styles, B.T. A generic monograph of the Meliaceae. Blumea Biodivers. Evol. Biogeogr. Plants 1975, 22, 419–540. [Google Scholar]

- Dean, F.M.; Taylor, D.A.H. Extractives from East African timbers. Part II. Ptæroxylon obliquum. J. Chem. Soc. C Org. 1966, 114–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Eck, H.; Ham, C.; Van Wyk, G. Survey of indigenous tree uses and preferences in the Eastern Cape Province. S. Afr. For. J. 1997, 180, 61–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wirminghaus, J.O.; Downs, C.T.; Symes, C.T.; Perrin, M.R. Fruiting in two afromontane forests in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa: The habitat type of the endangered Cape Parrot Poicephalus robustus. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2001, 67, 325–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grace, O.M.; Prendergast, H.D.V.; Jäger, A.K.; Van Staden, J.; Van Wyk, A.E. Bark medicines used in traditional healthcare in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa: An inventory. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2003, 69, 301–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Archer, R.; Reynolds, Y. Ptaeroxylon obliquum (Thunb) Radlk; National Biodiversity Institute: Cape Town, South Africa, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Nyahangare, E.T.; Mvumi, B.M.; Mutibvu, T. Ethnoveterinary plants and practices used for ecto-parasite control in semi-arid smallholder farming areas of Zimbabwe. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2015, 11, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cocks, M.L.; Wiersum, K.F. The significance of plant diversity to rural households in Eastern Cape province of South Africa. For. Trees Livelihoods 2003, 13, 39–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maphosa, V.; Masika, P.J. Ethnoveterinary uses of medicinal plants: A survey of plants used in the ethnoveterinary control of gastro-intestinal parasites of goats in the Eastern Cape Province, South Africa. Pharm. Biol. 2010, 48, 697–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cock, I.E.; Van Vuuren, S.F. Anti-Proteus activity of some South African medicinal plants: Their potential for the prevention of rheumatoid arthritis. Inflammopharmacology 2014, 22, 23–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramadwa, T.E.; McGaw, L.J.; Adamu, M.; Madikizela, B.; Eloff, J.N. Anthelmintic, antimycobacterial, antifungal, larvicidal and cytotoxic activities of acetone leaf extracts, fractions and isolated compounds from Ptaeroxylon obliquum (Rutaceae). J. Ethnopharmacol. 2021, 280, 114365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nomtshongwana, N.; Lawes, M.J.; Mander, M. Indigenous plant use in Gxalingenwa and KwaYili forests in the Southern Drakensberg, KwaZulu-Natal. Master’s Thesis, University of Natal, Durban, South Africa, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Lawes, M.J.; Griffiths, M.E.; Boudreau, S. Colonial logging and recent subsistence harvesting affect the composition and physiognomy of a podocarp dominated Afrotemperate forest. For. Ecol. Manag. 2007, 247, 48–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Flora Online. Available online: https://www.worldfloraonline.org/search?query=Ptaeroxylon (accessed on 24 April 2025).

- Makwarela, T.G.; Nyangiwe, N.; Masebe, T.; Mbizeni, S.; Nesengani, L.T.; Djikeng, A.; Mapholi, N.O. Tick diversity and distribution of hard (Ixodidae) cattle ticks in South Africa. Microbiol. Res. 2023, 14, 42–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adenubi, O.T.; Fasina, F.O.; McGaw, L.J.; Eloff, J.N.; Naidoo, V. Plant extracts to control ticks of veterinary and medical importance: A review. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2016, 150, 178–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solazzo, D.; Moretti, M.V.; Tchamba, J.J.; Rafael, M.F.F.; Tonini, M.; Fico, G.; Basterrecea, T.; Levi, S.; Marini, L.; Bruschi, P. Preserving ethnoveterinary medicine (EVM) along the transhumance routes in southwestern Angola: Synergies between international cooperation and academic research. Plants 2024, 13, 670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruschi, P.; Urso, V.; Solazzo, D.; Tonini, M.; Signorini, M.A. Traditional knowledge on ethno-veterinary and fodder plants in South Angola: An ethnobotanic field survey in Mopane woodlands in Bibala, Namibe province. J. Agric. Environ. Int. Dev. 2017, 111, 105–121. [Google Scholar]

- Moyo, B.; Masika, P.J. Tick control methods used by resource-limited farmers and the effect of ticks on cattle in rural areas of the Eastern Cape Province, South Africa. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 2009, 41, 517–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selogatwe, K.M.; Asong, J.A.; Struwig, M.; Ndou, R.V.; Aremu, A.O. A review of ethnoveterinary knowledge, biological activities and secondary metabolites of medicinal woody plants used for managing animal health in South Africa. Vet. Sci. 2021, 8, 228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Wet, H.; Ramulondi, M.; Ngcobo, Z.N. The use of indigenous medicine for the treatment of hypertension by a rural community in northern Maputaland, South Africa. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2016, 103, 78–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sewani-Rusike, C.R.; Mammen, M. Medicinal plants used as home remedies: A family survey by first year medical students. Afr. J. Tradit. Complement. Altern. Med. 2014, 11, 67–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Semenya, S.S.; Maroyi, A. Ethnobotanical study of plants used medicinally by Bapedi traditional healers to treat sinusitis and related symptoms in the Limpopo province, South Africa. J. Appl. Bot. Food Qual. 2018, 91, 287–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawal, I.O.; Grierson, D.S.; Afolayan, A.J. Phytotherapeutic information on plants used for the treatment of tuberculosis in Eastern Cape Province, South Africa. Evid.-Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2014, 2014, 735423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papo, L.A.; Van Vuuren, S.F.; Moteetee, A.N. The ethnobotany and antimicrobial activity of selected medicinal plants from Ga-Mashashane, Limpopo Province, South Africa. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2022, 149, 196–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maroyi, A. Use of herbal formulations for the treatment of circumcision wounds in Eastern and Southern Africa. Plant Sci. Today 2021, 8, 517–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGaw, L.J.; Eloff, J.N. Ethnoveterinary use of southern African plants and scientific evaluation of their medicinal properties. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2008, 119, 559–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutchings, A.; van Staden, J. Plants used for stress-related ailments in traditional Zulu, Xhosa and Sotho medicine. Part 1: Plants used for headaches. J. Ethnopharmacol. 1994, 43, 89–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGaw, L.J.; Famuyide, I.M.; Khunoana, E.T.; Aremu, A.O. Ethnoveterinary botanical medicine in South Africa: A review of research from the last decade (2009 to 2019). J. Ethnopharmacol. 2020, 257, 112864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mwinga, J.L.; Otang-Mbeng, W.; Kubheka, B.P.; Aremu, A.O. Ethnobotanical survey of plants used by subsistence farmers in mitigating cabbage and spinach diseases in OR Tambo Municipality, South Africa. Plants 2022, 11, 3215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mzimba, N.F.; Moteetee, A.; Van Vuuren, S. Southern African plants used as soap substitutes; phytochemical, antimicrobial, toxicity and formulation potential. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2023, 163, 673–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afolayan, A.J.; Grierson, D.S.; Mbeng, W.O. Ethnobotanical survey of medicinal plants used in the management of skin disorders among the Xhosa communities of the Amathole District, Eastern Cape, South Africa. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2014, 153, 220–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oyedemi, S.O.; Oyedemi, B.O.; Falowo, A.B.; Fayemi, P.O.; Coopoosamy, R.M. Antibacterial and ciprofloxacin modulating activity of Ptaeroxylon obliquum (Thunb.) Radlk leaf used by the Xhosa people of South Africa for the treatment of wound infections. Biotechnol. Biotechnol. Equip. 2016, 30, 1006–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Vásquez, L.; Ruiz Mesia, L.; Caballero Ceferino, H.D.; Ruiz Mesia, W.; Andrés, M.F.; Díaz, C.E.; Gonzalez-Coloma, A. Antifungal and herbicidal potential of piper essential oils from the peruvian amazonia. Plants 2022, 11, 1793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agostinho, D.; Boudesocque, L.; Thery-Kone, I.; Debierre-Grockiego, F.; Gueiffier, A.; Enguehard-Gueiffier, C.; Allouchi, H. A new meroterpenoid isolated from roots of Ptaeroxylon obliquum Radlk. Phytochem. Lett. 2013, 6, 560–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dean, F.M.; Robinson, M.L. The heartwood chromones of Cedrelopsis grevei. Phytochemistry 1971, 10, 3221–3227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballantyne, M.M.; McCabe, P.H.; Murray, R.D.H. Claisen rearrangements—II: Synthesis of six natural coumarins. Tetrahedron 1971, 27, 871–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muscarella, M.; Kimber, M.C.; Moody, C.J. Synthesis of ptaeroxylin (desoxykarenin): An unusual chromone from the sneezewood tree Ptaeroxylon obliquum. Synlett 2008, 2008, 2101–2102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruder, M.; Haseler, P.L.; Muscarella, M.; Lewis, W.; Moody, C.J. Synthesis of the oxepinochromone natural products ptaeroxylin (desoxykarenin), ptaeroxylinol, and eranthin. J. Org. Chem. 2010, 75, 353–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahluwalia, V.K.; Jain, A.; Gupta, R. A convenient synthesis of linear 2-methylpyranochromones. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 1982, 55, 2649–2652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okorie, D.A. Chromones and limonoids from Harrisonia abyssinica. Phytochemistry 1982, 21, 2424–2426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langenhoven, J.H.; Breytenbach, J.C.; Gerritsma-Van der Vijver, L.M.; Fourie, T.G. An antihypertensive chromone from Ptaeroxylon obliquum. Planta Med. 1988, 54, 373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Wyk, C.; Botha, F.S.; Vleggaar, R.; Eloff, J.N. Obliquumol, a novel antifungal and a potential scaffold lead compound, isolated from the leaves of Ptaeroxylon obliquum (sneezewood) for treatment of Candida albicans infections. Suid-Afr. Tydskr. Vir Natuurwetenskap En Tegnol. 2018, 37, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Ramadwa, T.E.; Awouafack, M.D.; Sonopo, M.S.; Eloff, J.N. Antibacterial and antimycobacterial activity of crude extracts, fractions, and isolated compounds from leaves of sneezewood, Ptaeroxylon obliquum (rutaceae). Nat. Prod. Commun. 2019, 14, 1934578X19872927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khunoana, E.T.; Eloff, J.N.; Ramadwa, T.E.; Nkadimeng, S.M.; Selepe, M.A.; McGaw, L.J. In vitro antiproliferative activity of Ptaeroxylon obliquum leaf extracts, fractions and isolated compounds on several cancer cell lines. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 11004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojo, M.C.; Mosa, R.A.; Osunsanmi, F.O.; Revaprasadu, N.; Opoku, A.R. In silico and in vitro assessment of the anti-β-amyloid aggregation and anti-cholinesterase activities of Ptaeroxylon obliquum and Bauhinia bowkeri extracts. Electron. J. Biotechnol. 2024, 68, 67–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramadwa, T.E.; Dzoyem, J.P.; Adebayo, S.A.; Eloff, J.N. Ptaeroxylon obliquum leaf extracts, fractions and isolated compounds as potential inhibitors of 15-lipoxygenase and lipopolysaccharide-induced nitric oxide production in RAW 264.7 macrophage cells. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2022, 147, 192–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramadwa, T.E.; Selepe, M.A.; Sonopo, M.S.; McGaw, L.J.; Eloff, J.N. Eloff. Quantitative UPLC-MS/MS analysis of obliquumol from Ptaeroxylon obliquum (Thunb.) Radlk. extracts and biological activities of its semi-synthesised derivative ptaeroxylinol. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2023, 156, 35–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junior, P. Eranthin und eranthin-β-D-glucosid: Zwei neue chromone aus Eranthis hiemalis. Phytochemistry 1979, 18, 2053–2054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramadwa, T.E.; McGaw, L.J.; Madikizela, B.; Eloff, J.N. Acute animal toxicity and genotoxicity of obliquumol, a potential new framework antifungal compound isolated from Ptaeroxylon obliquum (Rutaceae) leaf extracts. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2024, 172, 175–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGaw, L.J.; Makhafola, T.J.; Udom, O.O.; Mayekiso, K.T.V.; Eloff, J.N. Antimycobacterial activity, cytotoxicity and genotoxicity studies of Ptaeroxylon obliquum and Sideroxylon inerme leaf extracts. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2012, 79, 199–200. [Google Scholar]

- Clarkson, C.; Maharaj, V.J.; Crouch, N.R.; Grace, O.M.; Pillay, P.; Matsabisa, M.G.; Bhagwandin, N.; Smith, P.J.; Folb, P.I. In vitro antiplasmodial activity of medicinal plants native to or naturalised in South Africa. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2004, 92, 177–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nielsen, T.R.; Kuete, V.; Jäger, A.K.; Meyer, J.J.M.; Lall, N. Antimicrobial activity of selected South African medicinal plants. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2012, 12, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Famuyide, I.M.; Eloff, J.N.; McGaw, L.J. Antibacterial, antibiofilm activity and cytotoxicity of crude extracts of Ptaeroxylon obliquum (Ptaeroxylaceae) used in South African ethnoveterinary medicine against Bacillus anthracis Sterne vaccine strain. FASEB J. 2020, 34, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimba, H.; Coenders-Gerrits, M.; Banda, K.; Schilperoort, B.; van de Giesen, N.; Nyambe, I.; Savenije, H.H. Phenophase-based comparison of field observations to satellite-based actual evaporation estimates of a natural woodland: Miombo woodland, southern Africa. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2023, 27, 1695–1722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botha, F.S.; Van Wyk, C.; Bagla, V.; Eloff, J.N. The in vitro inhibitory effect of Ptaeroxylon obliquum (Thunb.) Radlk. on adhesion of Candida albicans to human buccal epithelial cells (HBEC). S. Afr. J. Bot. 2012, 79, 179. [Google Scholar]

- Khumalo, G.P.; Nguyen, T.; Van Wyk, B.E.; Feng, Y.; Cock, I.E. Inhibition of pro-inflammatory cytokines by selected southern African medicinal plants in LPS-stimulated RAW 264.7 macrophages. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2024, 319, 117268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGaw, L.J.; Jäger, A.K.; van Staden, J. Prostaglandin synthesis inhibitory activity in Zulu, Xhosa and Sotho medicinal plants. Phytother. Res. Int. J. Devoted Med. Sci. Res. Plants Plant Prod. 1997, 11, 113–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maharaj, R.; Maharaj, V.; Crouch, N.R.; Bhagwandin, N.; Folb, P.I.; Pillay, P.; Gayaram, R. Screening for adulticidal bioactivity of South African plants against Anopheles arabiensis. Malar. J. 2011, 10, 233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokoka, T.A.; Zimmermann, S.; Julianti, T.; Hata, Y.; Moodley, N.; Cal, M.; Adams, M.; Kaiser, M.; Brun, R.; Koorbanally, N.; et al. In vitro screening of traditional South African malaria remedies against Trypanosoma brucei rhodesiense, Trypanosoma cruzi, Leishmania donovani, and Plasmodium falciparum. Planta Med. 2011, 77, 1663–1667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malefo, M.S.; Ramadwa, T.E.; Famuyide, I.M.; McGaw, L.J.; Eloff, J.N.; Sonopo, M.S.; Selepe, M.A. Selepe. Synthesis and antifungal activity of chromones and benzoxepines from the leaves of Ptaeroxylon obliquum. J. Nat. Prod. 2020, 83, 2508–2517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| No. | Compounds | Molecular Formula | Molecular Weight (g/mol) | Area (%) | Retention Time |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Bicyclogermacrene | C15H24 | 204.35 | 7.9 | 15.24 |

| 2 | 10-Epi-elemol | C15H26O | 222.37 | 7.3 | 16.31 |

| 3 | Caryophyllene | C15H24 | 204.35 | 6.8 | 13.61 |

| 4 | α-Pinene | C10H16 | 136.23 | 6.0 | 3.82 |

| 5 | β-Pinene | C10H16 | 136.23 | 5.1 | 4.42 |

| 6 | α-Gurjunene | C15H24 | 204.35 | 1.3 | 13.37 |

| 7 | Caryophyllene oxide | C15H24O | 220.35 | 0.4 | 17.06 |

| 8 | Camphene | C10H16 | 136.23 | 4.4 | 4.03 |

| 9 | Limonene | C10H16 | 136.23 | 1.2 | 5.22 |

| 10 | (-)-cis-β-Elemene | C15H24 | 204.35 | 0.6 | 11.72 |

| 11 | α-Cubebene | C15H24 | 204.35 | 0.3 | 12.03 |

| 12 | Copaene | C15H24 | 204.35 | 1.2 | 12.61 |

| 13 | β-Bourbonene | C15H24 | 204.35 | 0.4 | 12.82 |

| 14 | β-Elemene | C15H24 | 204.35 | 0.6 | 12.93 |

| 15 | (-)-β-Copaene isomer | C15H24 | 204.35 | 0.7 | 13.79 |

| 16 | (+)-Bromadendrene | C15H24 | 204.35 | 1.2 | 14.02 |

| 17 | α-Humulene | C15H24 | 204.35 | 2.1 | 14.35 |

| 18 | Neoalloocimene | C10H16 | 136.23 | 0.5 | 14.51 |

| 19 | Eudesma-3,7-(11)-diene | C15H24 | 204.35 | 1.4 | 14.78 |

| 20 | Germacrene-D | C15H24 | 204.35 | 3.5 | 14.91 |

| 21 | (+)-β-Selinene | C15H24 | 204.35 | 0.4 | 15.05 |

| 22 | ץ-Cadinene | C15H26 | 204.35 | 1.5 | 15.59 |

| 23 | δ-Cadinene | C15H24 | 204.35 | 4.1 | 15.76 |

| 24 | Guaiol | C15H26O | 222.35 | 3.1 | 17.32 |

| 25 | Humulene epoxide | C15H24O | 220.35 | 0.3 | 17.59 |

| 26 | α-Eudesmol | C15H26O | 222.35 | 4.5 | 18.01 |

| 27 | τ-Muurolol | C15H26O | 222.35 | 3.1 | 18.28 |

| 28 | Neointermedeol | C15H26O | 222.35 | 2.9 | 18.46 |

| No. | Compounds | Plant Part | Detection/Isolation Method | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 29 | Ptaeroxylinol acetate | Roots | Isolated; IR, NMR | [2,38] |

| 30 | Peucenin | Heartwood or bark, roots | Isolated; HPLC, NMR | [2,38] |

| 31 | Prenyletin | Heartwood or bark, roots | Isolated; HPLC NMR | [38,39] |

| 32 | Scopoletin | Heartwood, roots | Isolated; HPLC, NMR | [2,39] |

| 33 | Ptaerobliquol | Heartwood | Isolated; Crystal X-ray analysis, UV, IR, NMR | [38] |

| 34 | Nieshoutin/Cyclo-obliquetin | Heartwood | Isolated; UV, NMR | [39,40] |

| 35 | Nieshoutol | Heartwood | Isolated; UV, NMR | [39,40] |

| 36 | Obliquetin | Heartwood | Isolated; NMR | [38,39] |

| 37 | Aesculetin | Heartwood | Isolated; UV, NMR | [40] |

| 38 | Obliquin | Heartwood | Isolated; NMR | [39,40] |

| 39 | Umtatin | Heartwood | Isolated; NMR | [5,39] |

| 40 | Heteropeucenin 7-methyl ether | Heartwood | Isolated; NMR | [39] |

| 41 | Heteropeucenin | Wood | Isolated; UV, NMR | [39] |

| 42 | Heteropeucenin dimethyl ether | Wood | Isolated; UV, NMR | [39] |

| 43 | Alloptaeroxylin | Wood | Isolated; UV, NMR | [39] |

| 44 | Ptaerochromenol | Wood | Isolated; UV, NMR | [39] |

| 45 | Peucenin 7-methyl ether | Wood | Isolated; UV, NMR | [39] |

| 46 | Dehydroptaeroxylin | Wood | Isolated; UV, NMR | [39] |

| 47 | Ptaeroglycol | Wood | Isolated; UV, NMR | [39] |

| 48 | Ptaerocyclin | Wood | Isolated; UV, NMR | [39] |

| 49 | Ptaeroxylone | Wood | Isolated; UV, NMR | [39] |

| 50 | Obliquol | Heartwood | Isolated; NMR | [5,39] |

| 51 | Obliquetol | Wood | Isolated; UV, NMR | [39] |

| 52 | Ptaeroxylin (desoxykarenin) | Heartwood | Isolated; NMR, X-ray | [5,39,42] |

| 53 | Obliquumol | Leaves | Isolated; NMR, UPLC-MS | [46,48,50,51] |

| 54 | β-Amyrin | Leaves | Isolated; NMR | [46,48,50,51] |

| 55 | Lupeol | Leaves | Isolated; NMR | [46,47] |

| 56 | Eranthin | Leaves | Isolated; NMR | [42,47,52] |

| 57 | O-Methylalloptaeroxylin | Leaves | Isolated; NMR | [43,44,45,48] |

| 58 | Guaia-1(10),11-diene | Stem bark | Tentatively identified; GC-MS | [49] |

| 59 | Gamma-Gurjuneneperoxide-(2) | Stem bark | Tentatively identified; GC-MS | [49] |

| 60 | Bicyclo [5.2.0] nonane, 2-methylene-4,8,8-trim ethyl-4-vinyl- | Stem bark | Tentatively identified; GC-MS | [49] |

| 61 | Spathulenol | Stem bark | Tentatively identified; GC-MS | [49] |

| 62 | Epiglobulol | Stem bark | Tentatively identified; GC-MS | [49] |

| 63 | Cycloheptane, 4-methylene-1-methyl-2-(2-methyl-1-propen-1-y1)-1-vinyl- | Stem bark | Tentatively identified; GC-MS | [49] |

| 64 | Gigantol | Stem bark | Tentatively identified; GC-MS | [49] |

| 65 | Cyclohexane, 1-ethenyl-1-methyl-2,4-bis(1-methylethenyl)-, [1S-(1α,2β,4β)]- | Stem bark | Tentatively identified; GC-MS | [49] |

| 66 | 1,5,9-Cyclotetradecatriene, 1,5,9-trim ethyl-12-(1-methylethenyl)- | Stem bark | Tentatively identified; GC-MS | [49] |

| 67 | Thunbergol | Stem bark | Tentatively identified; GC-MS | [49] |

| 68 | n-Hexadecanoic acid | Stem bark | Tentatively identified; GC-MS | [49] |

| 69 | 9,12,15-Octadecatrienoic acid,2,3-dihydroxypropyl ester, (Z,Z,Z)- | Stem bark | Tentatively identified; GC-MS | [49] |

| 70 | Vaccenic acid, cis- | Stem bark | Tentatively identified; GC-MS | [49] |

| 71 | Octadecanoic acid,2-[2-[2-(2-hydroxyethoxy) ethoxy] ethyl ester | Stem bark | Tentatively identified; GC-MS | [49] |

| 72 | Hexadecenoic acid, ethyl ester | Stem bark | Tentatively identified; GC-MS | [49] |

| 73 | Isopropyl Linoleate | Stem bark | Tentatively identified; GC-MS | [49] |

| 74 | 7-Hexadecenal, (Z)- | Stem bark | Tentatively identified; GC-MS | [49] |

| 75 | Phenol, 2,5-bis (1,1-dimethyl ethyl)- | Stem bark | Tentatively identified; GC-MS | [49] |

| 76 | 1,3,6,10-Cyclotetradecatetraene,3,7,11-trimethyl-14-(1-methylethyl)- | Stem bark | Tentatively identified; GC-MS | [36] |

| 77 | Dodecane, 1-fluoro- | Stem bark | Tentatively identified; GC-MS | [36] |

| 78 | Hentriacontane | Stem bark | Tentatively identified; GC-MS | [36] |

| 79 | Sulfurous acid, 2-ethylhexyl hexadecyl ester | Stem bark | Tentatively identified; GC-MS | [36] |

| 80 | Hexacosyl acetate | Stem bark | Tentatively identified; GC-MS | [36] |

| Plant Part | Crude Extracts/Fractions/Compound | Pharmacological Activities | Bioassay Model | Results | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Leaves | Acetone extracts | Antifungal | MIC | A. niger, C. gloeosporioides and P. digitatum had MICs of 80 μg/mL. | [49] |

| Cytotoxicity | MTT | Toxic against Vero cells with CC50 = 14.2 μg/mL and IC50 of 16.1 μg/mL. | [14,48] | ||

| Antibacterial | MIC | MIC of 4 µg/mL against S. sonnei and 16.4 µg/mL against S. pneumoniae and P. mirabilis. | [36] | ||

| Anticancer | MTT | IC50 of 8.6 ± 0.8 µg/mL on HEG2 and 23.3 ± 6.6 µg/mL on MCF7. | [48] | ||

| Antioxidant | DPPH ABTS | IC50 of 150.6 ± 1.2 µg/mL IC50 of 251.2 ± 50 µg/mL | |||

| Genotoxicity | Ames test | Non mutagenic against all tested strains S. typhimurium strains (TA98, TA100, and TA 102). | [53,54] | ||

| Antimycobacterial | MIC | MIC of 20 μg/mL against M. fortuitum. MICs of ≤100 μg/mL against M. aurum and M. bovi | [14,47] | ||

| Antiparasitic | Egg hatch assay (EHA), larval development test (LDT) | LC50 of 3.08 ± 0.05 mg/mL on EHA and 2.21 ± 0.18 mg/mL on LDT | [14] | ||

| Aqueous extracts | Antiproliferative | MTT | IC50 of 136.6 ± 17.8 µg/mL against A549 cells. | [48] | |

| Antioxidant | DPPH ABTS | IC50 of 43.4 ± 6.1 µg/mL. IC50 of 21.5 ± 0.2 µg/mL | [48] | ||

| Antiparasitic | Anti-plasmodial activity (P. falciparum D10) | IC50 of ˃100 µg/mL against P. falciparum D10. | [55] | ||

| Antibacterial | MIC | MIC of 487 µg/mL against P. mirabilis. | [13] | ||

| Chloroform fraction | Antifungal | MIC | MIC of 45 µg/mL against C. albicans strain. | [46] | |

| Anticancer | MTT assay | IC50 of 33.5 ± 3 µg/mL against HepG2. | [48] | ||

| Antibacterial | MIC | MIC of 80 µg/mL against P. aeruginosa. | [47] | ||

| Antioxidant | DPPH ABTS | IC50 of 387.4 ± 27.3 µg/mL IC50 of 214.2 ± 13.1 µg/mL | [48] | ||

| Anti-inflammatory | 15-LOX inhibition assay, NO inhibition assay | IC50 of 3.03 mg/mL on lipoxygenase enzyme | [50] | ||

| Cytotoxicity | MTT | LC50 of 28.6 µg/mL against mouse fibroblast cells | [46] | ||

| Genotoxicity | Ames test | Non mutagenic against S. typhimurium strains TA98, TA100, and TA102. | [53] | ||

| Ethyl acetate fraction | Antifungal | MIC | MIC = 300 µg/mL on C. albicans. | [46] | |

| Cytotoxicity | MTT | IC50 of 229.7 µg/mL against fibroblast cells | |||

| Hexane fraction | Genotoxicity | Ames test | Not genotoxic on S. typhimurium strains (TA98, TA100, and TA 102) tested. | [53] | |

| Antioxidant | DPPH ABTS | IC50 = 236.5 ± 42.1 µg/mL IC50 = 143.7 ± 3.3 µg/mL. | [47] | ||

| Antifungal | MIC | MIC = 180 µg/mL against A. fumigatus. | [14] | ||

| H2O fraction | Antifungal | MIC | MIC = 2500.0 µg/mL against A. fumigatus, A. niger, F. oxysporum and C. gloeosporioides | [14,53] | |

| Cytotoxicity | LC50 of 0.08 µg/mL against mouse fibroblast cells. | [46] | |||

| Butanol fraction | Antifungal | MIC | MIC of 320 µg/mL against C. gloeosporioides and 630 µg/mL against A. niger | [53] | |

| Antibacterial | MIC | MIC of 630 µg/mL of S. aureus | [47] | ||

| Anti-inflammatory | 15-LOX inhibition assay | IC50 of 6.55 mg/mL against 15-LOX enzyme. | [50] | ||

| 30% H2O–MeOH fraction | Antimycobacterial | MIC | MIC of 40 µg/mL against M. fortuitum. | [47] | |

| Antibacterial | MIC | MIC of 320 µg/mL against S. aureus and E. faecalis. | [47] | ||

| Antifungal | MIC | MIC of 160 µg/mL against A. fumigatus | [47] | ||

| Anti-inflammatory | 15-LOX inhibition assay | IC50 of 5.24 mg/mL against 15-LOX enzyme. | [50] | ||

| Cytotoxicity | MTT | CC50 of 49.6 ± 0.002 µg/mL against Vero cells. | [14] | ||

| Genotoxicity | Ames test | Not genotoxic against S. typhimurium strains TA98, TA100, and TA 102. | [53] | ||

| Obliquumol (53) | Antifungal | MIC | MIC of 2 µg/mL against C. albicans and 8 µg/mL against C. neoformans. | [14] | |

| Anticancer | MTT | IC50 of 52.7 ± 4.8 µg/mL against HepG2 cells | [48] | ||

| Anti-inflammatory | 15-LOX inhibition assay | IC50 = 1.39 µg/mL against 15-LOX enzyme. | [50] | ||

| Antiparasitic | Egg hatch assay (EHA), larval development test (LDT) | LC50 of 0.22 ± 0.03 mg/mL against EHA and 0.095 ± 0.002 mg/mL against LDT on H. contortus. | [14] | ||

| Antibacterial | MIC | MIC of 31.5 µg/mL against S. aureus and P. aeruginosa. | [47] | ||

| Cytotoxicity | MTT | CC50 of ˃200 µg/mL against Vero and C3A cells. LC50 of 7.2 µg/mL against mouse fibroblast cells. | [46,47] | ||

| Antimycobacterial | MIC | MIC of 8 µg/mL against M. fortuitum and 16 µg/mL against M. smegmatis. MIC of 63 µg/mL against pathogenic M. tuberculosis ATCC 25177 | [14,46] | ||

| Genotoxicity | Ames test | Not genotoxic against S. typhimurium strains TA98, TA100, and TA 102. | [53] | ||

| In vivo animal studies | Acute toxicity (OECD 423 guidelines) | LD50 > 2000 mg/kg since no mouse mortalities occurred after 14 days. | [53] | ||

| β-Amyrin (54) and lupeol (55) mixture | Antifungal | MIC | Lowest MIC of 16 µg/mL against C. albicans and C. neoformans. | [14] | |

| Anticancer | MTT | IC50 of 122.6 ± 1.8 µg/mL against HepG2 cells. | [48] | ||

| Antibacterial | MIC | MIC of 62.5 µg/mL against S. aureus and P. aeruginosa. | [47] | ||

| Anti-inflammatory | 15-LOX inhibition assay | IC50 of 7.4 µg/mL against 15-LOX enzyme. | [51] | ||

| Antimycobacterial | MIC | MIC of 62.5 µg/mL against M. fortuitum and M. smegmatis. MIC = 125 µg/mL against pathogenic M. bovis ATCC 27290 and M. tuberculosis ATCC 25177. | [14,47] | ||

| Cytotoxicity | MTT | LC50 of 0.001 µg/mL against fibroblast cells. | [53] | ||

| Genotoxicity | Ames test | Non mutagenic against S. typhimurium strains TA98, TA100, and TA 102. | [53] | ||

| Eranthin (56) | Anti-inflammatory | 15-LOX inhibition assay | LC50 = 7.5 µg/mL | [50] | |

| DCM extracts | Antiparasitic | Anti-plasmodial activity | IC50 = 19.5 µg/mL against P. falciparum D10. | [55] | |

| DCM–MeOH extracts | Antiparasitic | Anti-plasmodial activity | IC50 = 22.8 µg/mL against P. falciparum D10. | ||

| MeOH extracts | Antibacterial | MIC | MIC of 4 µg/mL against S. sonnei and 32 µg/mL against S. aureus and P. vulgaris. | [36] | |

| Antimycobacterial | MIC | MIC = ˃2500 µg/mL against M. smegmatis, | [56] | ||

| Antifungal | MIC | MIC = 156.25 µg/mL against C. albicans | |||

| Antioxidant | DPPH | IC50 of ˂150 µg/mL | [36] | ||

| O-methylalloptaeroxylin (57) | Antiproliferative | MTT | IC50 of 212.7 ± 1.8 µg/mL against HeLa cells and 151.5 ± 38.7 µg/mL on Vero cells. | [48] | |

| Ethanol extracts | Antibacterial | MIC | MIC of 4 µg/mL against S. sonnei. | [36] | |

| Chloroform extracts | Antibacterial | MIC | MIC = 8 µg/mL against S. sonnei and P. mirabilis | [36] | |

| Stem | DCM–MeOH extracts | Antiparasitic | Antiplasmodial activity | IC50 = 5.5 µg/mL against P. falciparum D10. | [55] |

| DCM extracts | Antiparasitic | Antiplasmodial activity | IC50 = 17 µg/mL against P. falciparum D10. | [55] | |

| Aqueous extracts | Antiparasitic | Antiplasmodial activity | IC50 > 100 µg/mL against P. falciparum D10. | [55] | |

| Roots | DCM–MeOH extracts | Antiparasitic | Antiplasmodial activity | IC50 = 17 µg/mL against P. falciparum D10. | [55] |

| DCM extracts | Antiparasitic | Antiplasmodial activity | IC50 = 19 µg/mL against P. falciparum D10. | ||

| Aqueous extracts | Antiparasitic | Antiplasmodial activity | IC50 > 100 µg/mL against P. falciparum D10. | ||

| Ptaerobliquol (33) | Antiparasitic | Antiplasmodial activity | Toxoplasma gondii had moderate activity with an IC50 of 5.13 µM | [38] | |

| Bark | MeOH extracts | Antibacterial | MIC | MIC of 78.12 µg/mL against E. coli. | [56] |

| Antifungal | MIC (C. albicans and M. audouinii) | MIC range from 78.12 µg/mL to 312.50 µg/mL | [56] | ||

| Aqueous extracts | Antiparasitic | In vitro repellence and contact bio-assay models | A total of 40% reduction in R. appendiculatus and R. microplus by 26.8% and 11%, respectively | [22] | |

| Anti-inflammatory | MTT | Aqueous extracts significantly decreased (p < 0.0005) IL-6 and MCP-1 levels compared to the control. | [48] | ||

| Ethanol extracts | Cytotoxicity | MTT | RAW 264.7 murine macrophages and human dermal fibroblasts had cell viability of >100% and >80%, respectively. | [48] | |

| Anti-inflammatory | MTT | Significantly decreased (p < 0.0005) IL-6 and TNF-α levels compared to the control. | [49] | ||

| Stem bark | Hexane extract | Anti-cholinesterase | Cholinesterase inhibitory activity assay | Had good butyrylcholinesterase activity with an IC50 of 4.79 µg/mL. Had acetylcholinesterase inhibitory activity with an IC50 of 77.01 µg/mL. | [49] |

| DCM extracts | Anti-cholinesterase | Cholinesterase inhibitory activity assay | Had butyrylcholinesterase inhibitory activity with an IC50 of 1.77 µg/mL and acetylcholinesterase inhibitory activity of 66.59 µg/mL. | [49] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Makumbane, N.; Nkadimeng, S.M.; Khunoana, E.T.; Ramadwa, T.E. A Review of the Ethnomedicine, Phytochemistry, Pharmacology and Toxicological Studies on Ptaeroxylon obliquum (Thunb.) Radlk. (Rutaceae). Plants 2025, 14, 1746. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14121746

Makumbane N, Nkadimeng SM, Khunoana ET, Ramadwa TE. A Review of the Ethnomedicine, Phytochemistry, Pharmacology and Toxicological Studies on Ptaeroxylon obliquum (Thunb.) Radlk. (Rutaceae). Plants. 2025; 14(12):1746. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14121746

Chicago/Turabian StyleMakumbane, Ntanganedzeni, Sanah Malomile Nkadimeng, Edward Thato Khunoana, and Thanyani Emelton Ramadwa. 2025. "A Review of the Ethnomedicine, Phytochemistry, Pharmacology and Toxicological Studies on Ptaeroxylon obliquum (Thunb.) Radlk. (Rutaceae)" Plants 14, no. 12: 1746. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14121746

APA StyleMakumbane, N., Nkadimeng, S. M., Khunoana, E. T., & Ramadwa, T. E. (2025). A Review of the Ethnomedicine, Phytochemistry, Pharmacology and Toxicological Studies on Ptaeroxylon obliquum (Thunb.) Radlk. (Rutaceae). Plants, 14(12), 1746. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14121746