Spatially-Explicit Simulation Modeling of Ecological Response to Climate Change: Methodological Considerations in Predicting Shifting Population Dynamics of Infectious Disease Vectors

Abstract

:1. Introduction

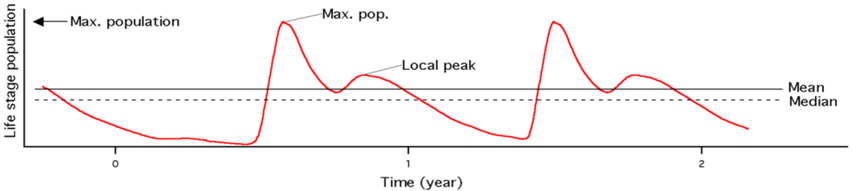

| Absolute Population Features | ||

| Mean &Median | Avg. and median population (3yr) |  |

| Peak Pop. | Avg. of maximum yearly population | |

| Peaks per Year | Avg. no. of peaks per year | |

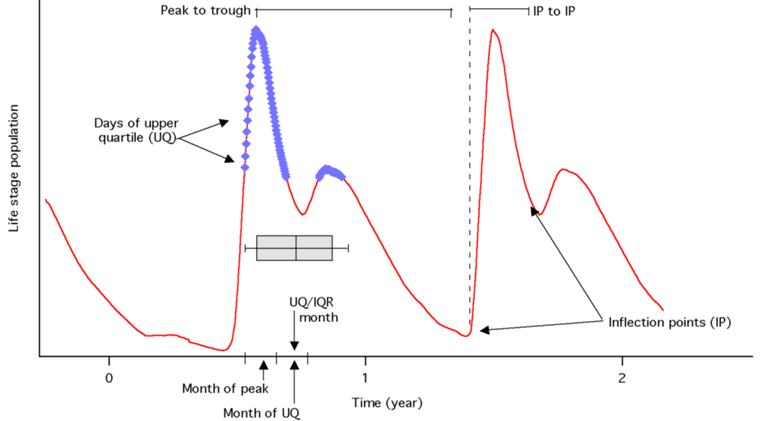

| Timing Population Features | ||

| Peak Month | Month of the yearly peak |  |

| Peak to Trough | No. of days between yearly peak and yearly trough | |

| IP to IP | Time between inflection points (IP) on either side of yearly max. pop. | |

| UQ/IQR | Avg. of month during which the inter-quartile range (IQR) of the upper quartile (UQ) occur | |

| Wave Angle | Wave angle for period = 90.5 days, from continuous wavelet analysis using a complex Morlet waveform (after [33]). | |

| Exposure Population Features | ||

| IP Pop | The summation of tick population for all days included in the IP to IP calculation | |

2. Methods

2.1. Modeling Methodology

2.2. Lyme Model

2.3. Domain and Climate Data

2.4. Dynamic Features of Ixodes Population Response to Seasonality Shifts

2.5. Comparison of DPFs to Observed Data

2.6. Spatial Sensitivity Analysis

and variance τ2∕mi, where i~i′ denotes that county, i, shares a boundary with county i′, and mi is the number of boundary-sharing neighbors for county i. The percent change in β and the magnitude of parameter, τ2, which controls the degree of spatial similarly, were used to assess the improvement in fit provided by the addition of the spatial term to the logistic regression model.

and variance τ2∕mi, where i~i′ denotes that county, i, shares a boundary with county i′, and mi is the number of boundary-sharing neighbors for county i. The percent change in β and the magnitude of parameter, τ2, which controls the degree of spatial similarly, were used to assess the improvement in fit provided by the addition of the spatial term to the logistic regression model.3. Results

3.1. Correlation among DPFs

| Mean | Median | Peak Population | Peaks per Year | Peak Month | Peak to Trough | IP to IP | IP Pop | UQ/IQR | Wave Angle | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Questing Adult | ||||||||||

| Mean | 1 | 0.98 | −0.48 | 0.99 | −0.47 | 0.25 | 0.26 | 0.98 | 0.55 | −0.34 |

| Median | 0.98 | 1 | −0.47 | 0.96 | −0.46 | 0.24 | 0.19 | 0.94 | 0.47 | −0.24 |

| Peak Population | −0.48 | −0.47 | 1 | −0.46 | 0.86 | 0.11 | −0.17 | −0.48 | −0.11 | 0.10 |

| Peaks per Year | 0.99 | 0.96 | −0.46 | 1 | −0.44 | 0.26 | 0.29 | 0.99 | 0.60 | −0.38 |

| Peak Month | −0.47 | −0.46 | 0.86 | −0.44 | 1 | 0.08 | −0.19 | −0.47 | −0.14 | 0.08 |

| Peak to Trough | 0.25 | 0.24 | 0.11 | 0.26 | 0.08 | 1 | 0.09 | 0.23 | 0.47 | −0.33 |

| IP to IP | 0.26 | 0.19 | −0.17 | 0.29 | −0.19 | 0.09 | 1 | 0.40 | 0.48 | −0.38 |

| IP Pop | 0.98 | 0.94 | −0.48 | 0.99 | −0.47 | 0.23 | 0.40 | 1 | 0.63 | −0.41 |

| UQ/IQR | 0.55 | 0.47 | −0.11 | 0.60 | −0.14 | 0.47 | 0.48 | 0.63 | 1 | −0.77 |

| Wave Angle | −0.34 | −0.24 | 0.10 | −0.38 | 0.08 | −0.33 | −0.38 | −0.41 | −0.77 | 1 |

| Questing Nymphs | ||||||||||

| Mean | 1 | 1.00 | −0.42 | 0.99 | 0.20 | 0.17 | 0.99 | 0.37 | 0.60 | −0.45 |

| Median | 1.00 | 1 | −0.41 | 0.98 | 0.21 | 0.18 | 0.98 | 0.38 | 0.62 | −0.47 |

| Peak Population | −0.42 | −0.41 | 1 | −0.43 | −0.59 | −0.01 | −0.43 | −0.11 | −0.10 | 0.02 |

| Peaks per Year | 0.99 | 0.98 | −0.43 | 1 | 0.19 | 0.14 | 0.99 | 0.35 | 0.55 | −0.40 |

| Peak Month | 0.20 | 0.21 | −0.59 | 0.19 | 1 | −0.25 | 0.17 | 0.12 | 0.03 | 0.17 |

| IP to IP | 0.17 | 0.18 | −0.01 | 0.14 | −0.25 | 1 | 0.26 | 0.49 | 0.58 | −0.63 |

| IP Pop | 0.99 | 0.98 | −0.43 | 0.99 | 0.17 | 0.26 | 1 | 0.40 | 0.61 | −0.46 |

| Peak to Trough | 0.37 | 0.38 | −0.11 | 0.35 | 0.12 | 0.49 | 0.40 | 1 | 0.71 | −0.51 |

| UQ/IQR | 0.60 | 0.62 | −0.10 | 0.55 | 0.03 | 0.58 | 0.61 | 0.71 | 1 | −0.82 |

| Wave Angle | −0.45 | −0.47 | 0.02 | −0.40 | 0.17 | −0.63 | −0.46 | −0.51 | −0.82 | 1 |

| Questing Larvae | ||||||||||

| Mean | 1 | 0.96 | −0.43 | 0.98 | 0.20 | −0.52 | 0.97 | 0.50 | 0.55 | 0.36 |

| Median | 0.96 | 1 | −0.37 | 0.90 | 0.17 | −0.65 | 0.88 | 0.44 | 0.70 | 0.27 |

| Peak Population | −0.43 | −0.37 | 1 | −0.43 | −0.57 | 0.17 | −0.43 | 0.03 | −0.09 | 0.13 |

| Peaks per Year | 0.98 | 0.90 | −0.43 | 1 | 0.20 | −0.44 | 0.99 | 0.55 | 0.46 | 0.45 |

| Peak Month | 0.20 | 0.17 | −0.57 | 0.20 | 1 | −0.11 | 0.19 | −0.03 | 0.00 | −0.06 |

| IP to IP | −0.52 | −0.65 | 0.17 | −0.44 | −0.11 | 1 | −0.39 | −0.38 | −0.92 | −0.16 |

| IP Pop | 0.97 | 0.88 | −0.43 | 0.99 | 0.19 | −0.39 | 1 | 0.55 | 0.42 | 0.46 |

| Peak to Trough | 0.50 | 0.44 | 0.03 | 0.55 | −0.03 | −0.38 | 0.55 | 1 | 0.41 | 0.74 |

| UQ/IQR | 0.55 | 0.70 | −0.09 | 0.46 | 0.00 | −0.92 | 0.42 | 0.41 | 1 | 0.17 |

| Wave Angle | 0.36 | 0.27 | 0.13 | 0.45 | −0.06 | −0.16 | 0.46 | 0.74 | 0.17 | 1 |

3.2. Comparison of DPFs to Observed Data

| Observational Data Set / Dichotomization | N | Mean | Median | Peak Population | Number Peaks/Yr | Peak Month | Peak to Trough | IP to IP | IP Pop | UQ/IQR | Wave Angle | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Questing Adults | |||||||||||||

| Lyme disease risk | |||||||||||||

| Minimal vs. Low/Medium/High | 1,683 | 0.47 | 0.48 | 0.73 | 0.45 | 0.70 | 0.60 | 0.56 | 0.45 | 0.62 | 0.51 | ||

| Minimal/Low vs. Medium/High | 1,683 | 0.64 | 0.67 | 0.81 | 0.62 | 0.82 | 0.53 | 0.48 | 0.60 | 0.58 | 0.59 | ||

| Minimal/Low/Medium vs. High | 1,683 | 0.72 | 0.74 | 0.83 | 0.72 | 0.84 | 0.74 | 0.63 | 0.71 | 0.68 | 0.61 | ||

| Minimal vs. High | 844 | 0.71 | 0.73 | 0.90 | 0.70 | 0.89 | 0.69 | 0.61 | 0.68 | 0.63 | 0.60 | ||

| Tick presence | |||||||||||||

| None vs. Reported/Established | 1,683 | 0.52 | 0.52 | 0.69 | 0.54 | 0.67 | 0.60 | 0.54 | 0.54 | 0.61 | 0.53 | ||

| None/Reported vs. Established | 1,683 | 0.48 | 0.49 | 0.67 | 0.47 | 0.67 | 0.53 | 0.52 | 0.46 | 0.57 | 0.52 | ||

| None vs. Established | 1,305 | 0.47 | 0.49 | 0.71 | 0.46 | 0.70 | 0.56 | 0.53 | 0.45 | 0.60 | 0.52 | ||

| Questing Nymphs | |||||||||||||

| Lyme disease risk | |||||||||||||

| Minimal vs. Low/Medium/High | 1,683 | 0.46 | 0.45 | 0.70 | 0.46 | 0.54 | 0.57 | 0.53 | 0.47 | 0.60 | 0.56 | ||

| Minimal/Low vs. Medium/High | 1,683 | 0.70 | 0.70 | 0.79 | 0.68 | 0.76 | 0.61 | 0.71 | 0.71 | 0.76 | 0.79 | ||

| Minimal/Low/Medium vs. High | 1,683 | 0.75 | 0.74 | 0.80 | 0.75 | 0.90 | 0.40 | 0.56 | 0.75 | 0.61 | 0.69 | ||

| Minimal vs. High | 844 | 0.73 | 0.73 | 0.86 | 0.73 | 0.92 | 0.65 | 0.56 | 0.74 | 0.55 | 0.67 | ||

| Tick presence | |||||||||||||

| None vs. Reported/Established | 1,683 | 0.53 | 0.53 | 0.67 | 0.53 | 0.55 | 0.54 | 0.54 | 0.52 | 0.55 | 0.51 | ||

| None/Reported vs. Established | 1,683 | 0.49 | 0.49 | 0.65 | 0.49 | 0.69 | 0.58 | 0.54 | 0.50 | 0.53 | 0.48 | ||

| None vs. Established | 1,305 | 0.48 | 0.52 | 0.69 | 0.48 | 0.68 | 0.58 | 0.55 | 0.49 | 0.54 | 0.49 | ||

| Questing Larvae | |||||||||||||

| Lyme disease risk | |||||||||||||

| Minimal vs. Low/Medium/High | 1,683 | 0.46 | 0.54 | 0.70 | 0.45 | 0.54 | 0.73 | 0.58 | 0.46 | 0.58 | 0.75 | ||

| Minimal/Low vs. Medium/High | 1,683 | 0.69 | 0.73 | 0.79 | 0.66 | 0.76 | 0.52 | 0.75 | 0.65 | 0.78 | 0.46 | ||

| Minimal/Low/Medium vs. High | 1,683 | 0.74 | 0.72 | 0.80 | 0.75 | 0.90 | 0.52 | 0.62 | 0.73 | 0.63 | 0.58 | ||

| Minimal vs. High | 844 | 0.73 | 0.71 | 0.85 | 0.72 | 0.92 | 0.37 | 0.58 | 0.71 | 0.61 | 0.58 | ||

| Tick presence | |||||||||||||

| None vs. Reported/Established | 1,683 | 0.53 | 0.53 | 0.68 | 0.54 | 0.55 | 0.66 | 0.55 | 0.53 | 0.54 | 0.70 | ||

| None/Reported vs. Established | 1,683 | 0.49 | 0.49 | 0.65 | 0.48 | 0.69 | 0.65 | 0.53 | 0.48 | 0.52 | 0.66 | ||

| None vs. Established | 1,305 | 0.52 | 0.52 | 0.69 | 0.47 | 0.68 | 0.69 | 0.55 | 0.47 | 0.53 | 0.71 | ||

3.2.1. Regional Analyses

| Midwest | North | South | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Observational Data Set/Dichotomization | N | Peak Month | Peak Population | N | Peak Month | Peak Population | N | Peak Month | Peak Population | |

| Questing Adults | ||||||||||

| Lyme disease risk | ||||||||||

| Minimal vs. Low/Medium/High | 461 | 0.82 | 0.81 | 214 | 0.68 | 0.67 | 1,008 | 0.60 | 0.64 | |

| Minimal/Low vs. Medium/High | 461 | 0.81 | 0.80 | 214 | 0.75 | 0.73 | 1,008 | 0.72 | 0.71 | |

| Minimal/Low/Medium vs. High | 461 | 0.89 | 0.92 | 214 | 0.72 | 0.71 | 1,008 | 0.70 | 0.70 | |

| Minimal vs. High | 226 | 0.95 | 0.96 | 88 | 0.79 | 0.78 | 530 | 0.77 | 0.78 | |

| Questing Nymphs | ||||||||||

| Lyme disease risk | ||||||||||

| Minimal vs. Low/Medium/High | 461 | 0.82 | 0.81 | 214 | 0.66 | 0.67 | 1,008 | 0.53 | 0.62 | |

| Minimal/Low vs. Medium/High | 461 | 0.81 | 0.80 | 214 | 0.75 | 0.74 | 1,008 | 0.95 | 0.63 | |

| Minimal/Low/Medium vs. High | 461 | 0.91 | 0.91 | 214 | 0.72 | 0.72 | 1,008 | 0.94 | 0.62 | |

| Minimal vs. High | 226 | 0.96 | 0.96 | 88 | 0.78 | 0.78 | 530 | 0.97 | 0.78 | |

| Questing Larvae | ||||||||||

| Lyme disease risk | ||||||||||

| Minimal vs. Low/Medium/High | 461 | 0.82 | 0.81 | 214 | 0.66 | 0.63 | 1,008 | 0.53 | 0.62 | |

| Minimal/Low vs. Medium/High | 461 | 0.81 | 0.80 | 214 | 0.75 | 0.71 | 1,008 | 0.95 | 0.61 | |

| Minimal/Low/Medium vs. High | 461 | 0.91 | 0.90 | 214 | 0.72 | 0.71 | 1,008 | 0.94 | 0.58 | |

| Minimal vs. High | 226 | 0.96 | 0.96 | 88 | 0.78 | 0.76 | 530 | 0.97 | 0.63 | |

3.2.2. Spatial Sensitivity Analysis

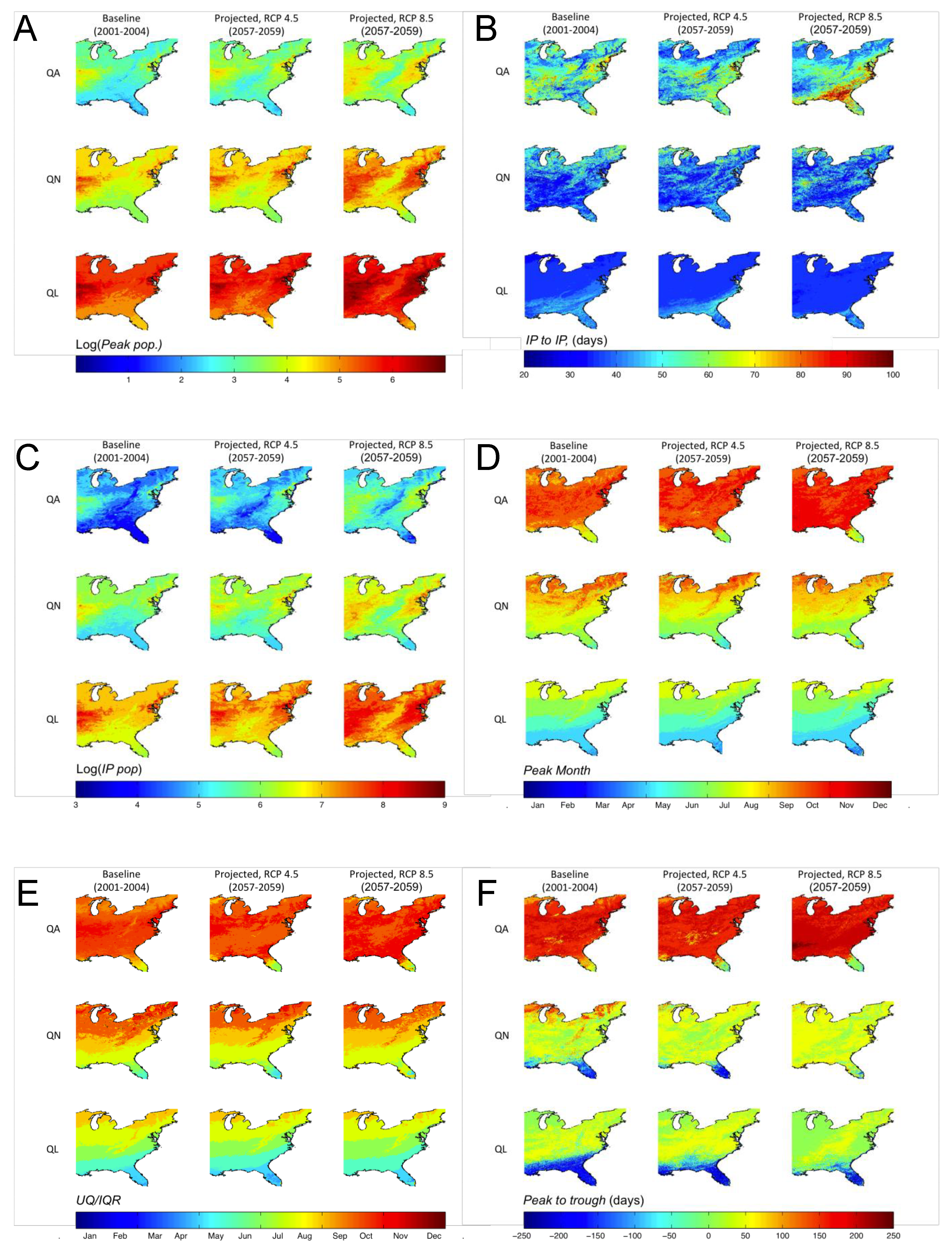

3.3. Shifts in Geographic Distribution of DPFs

4. Discussion and Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Conflict of Interest

References

- Dobson, A. Climate variability, global change, immunity, and the dynamics of infectious diseases. Ecology 2009, 90, 920–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altizer, S.; Dobson, A.; Hosseini, P.; Hudson, P.; Pascual, M.; Rohani, P. Seasonality and the dynamics of infectious diseases. Ecol. Lett. 2006, 9, 467–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kutz, S.J.; Hoberg, E.P.; Polley, L.; Jenkins, E.J. Global warming is changing the dynamics of Arctic host-parasite systems. Proc. Roy. Soc. B-Biol. Sci. 2005, 272, 2571–2576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lafferty, K.D. The ecology of climate change and infectious diseases. Ecology 2009, 90, 888–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Confalonieri, U.; Menne, B.; Akhtar, R.; Ebi, K.L.; Hauengue, M.; Kovats, R.S.; Revich, B.; Woodward, A. Human Health. In Climate Change 2007: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability; Parry, M.L., Canziani, O.F., Palutikof, J.P., van der Linden, P.J., Hanson, C.E., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2007; pp. 391–431. [Google Scholar]

- Ostfeld, R.S. Climate change and the distribution and intensity of infectious diseases. Ecology 2009, 90, 903–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascual, M.; Bouma, M.J. Do rising temperatures matter? Ecology 2009, 90, 906–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Randolph, S.E. Perspectives on climate change impacts on infectious diseases. Ecology 2009, 90, 927–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svoray, T.; Shafran-Nathan, R.; Henkin, Z.; Perevolotsky, A. Spatially and temporally explicit modeling of conditions for primary production of annuals in dry environments. Ecol. Model. 2008, 218, 339–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentz, B.J.; Regniere, J.; Fettig, C.J.; Hansen, E.M.; Hayes, J.L.; Hicke, J.A.; Kelsey, R.G.; Negron, J.F.; Seybold, S.J. Climate change and bark beetles of the western United States and Canada: Direct and indirect effects. Bioscience 2010, 60, 602–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corson, M.S.; Teel, P.D.; Grant, W.E. Microclimate influence in a physiological model of cattle-fever tick (Boophilus spp.) population dynamics. Ecol. Model. 2004, 180, 487–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, N.; Sutherst, R.W.; Hall, N.; Whish-Wilson, P. The vulnerability of the Australian beef industry to impacts of the cattle tick (Boophilus microplus) under climate change. Climatic Change 2003, 61, 157–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erickson, R.A.; Presley, S.M.; Allen, L.J.S.; Long, K.R.; Cox, S.B. A dengue model with a dynamic Aedes albopictus vector population. Ecol. Model. 2010, 221, 2899–2908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobson, A.R.; Provenzale, A.; von Hardenberg, A.; Bassano, B.; Festa-Bianchet, M. Climate forcing and density dependence in a mountain ungulate population. Ecology 2004, 85, 1598–1610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mount, G.A.; Haile, D.G.; Daniels, E. Simulation of blacklegged tick (Acari: Ixodidae) population dynamics and transmission of Borrelia burgdorferi. J. Med. Entomol. 1997, 34, 461–484. [Google Scholar]

- Sauvage, F.; Langlais, M.; Pontier, D. Predicting the emergence of human hantavirus disease using a combination of viral dynamics and rodent demographic patterns. Epidemiol. Infect. 2007, 135, 46–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brownstein, J.S.; Holford, T.R.; Fish, D. Effect of climate change on Lyme disease risk in North America. EcoHealth 2005, 2, 38–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diuk-Wasser, M.A.; Vourc’h, G.; Cislo, P.; Hoen, A.G.; Melton, F.; Hamer, S.A.; Rowland, M.; Cortinas, R.; Hickling, G.J.; Tsao, J.I. Field and climate-based model for predicting the density of host-seeking nymphal Ixodes scapularis, an important vector of tick-borne disease agents in the eastern United States. Global. Ecol. Biogeogr. 2010, 19, 504–514. [Google Scholar]

- Chuine, I. Why does phenology drive species distribution? Phil. Trans. Biol. Sci. 2010, 365, 3149–3160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visser, M.E.; Both, C. Shifts in phenology due to global climate change: The need for a yardstick. Proc. Roy. Soc. B-Biol. Sci. 2005, 272, 2561–2569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Austin, M.P. Spatial prediction of species distribution: an interface between ecological theory and statistical modelling. Ecol. Model. 2002, 157, 101–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guisan, A.; Thuiller, W. Predicting species distribution: Offering more than simple habitat models. Ecol. Lett. 2005, 8, 993–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuine, I.; Beaubien, E.G. Phenology is a major determinant of tree species range. Ecol. Lett. 2001, 4, 500–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitt, J.P.W.; Regniere, J.; Worner, S. Risk assessment of the gypsy moth, Lymantria dispar (L), in New Zealand based on phenology modelling. Int. J. Biometeorol. 2007, 51, 295–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Killilea, M.E.; Swei, A.; Lane, R.S.; Briggs, C.J.; Ostfeld, R.S. Spatial dynamics of Lyme disease: A review. EcoHealth 2008, 5, 167–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonnang, H.E.Z.; Kangalawe, R.Y.M.; Yanda, P.Z. Predicting and mapping malaria under climate change scenarios: The potential redistribution of malaria vectors in Africa. Malar. J. 2010, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebi, K.L.; Hartman, J.; Chan, N.; McConnell, J.; Schlesinger, M.; Weyant, J. Climate suitability for stable malaria transmission in Zimbabwe under different climate change scenarios. Climatic Change 2005, 73, 375–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogden, N.H.; Bigras-Poulin, M.; O’Callaghan, C.J.; Barker, I.K.; Lindsay, L.R.; Maarouf, A.; Smoyer-Tomic, K.E.; Waltner-Toews, D.; Charron, D. A dynamic population model to investigate effects of climate on geographic range and seasonality of the tick Ixodes scapularis. Int. J. Parasitol. 2005, 35, 375–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.N.; Yang, G.J.; Yang, K.; Wang, X.H.; Hong, Q.B.; Sun, L.P.; Malone, J.B.; Kristensen, T.K.; Bergquist, N.R.; Utzinger, J. Potential impact of climate change on schistosomiasis transmission in China. Amer. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2008, 78, 188–194. [Google Scholar]

- Moore, J.; Liang, S.; Akullian, A.; Remais, J. Cautioning the use of degree-day models for climate change projections: Predicting the future distribution of parasite hosts in the presence of parametric uncertainty. Ecol. Appl. 2012, 22, 2237–2247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hales, S.; de Wet, N.; Maindonald, J.; Woodward, A. Potential effect of population and climate changes on global distribution of dengue fever: An empirical model. Lancet 2002, 360, 830–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogden, N.H.; Maarouf, A.; Barker, I.K.; Bigras-Poulin, M.; Lindsay, L.R.; Morshed, M.G.; O’Callaghan, C.J.; Ramay, F.; Waltner-Toews, D.; Charron, D.F. Climate change and the potential for range expansion of the Lyme disease vector Ixodes scapularis in Canada. Int. J. Parasitol. 2006, 36, 63–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dennis, D.T.; Nekomoto, T.S.; Victor, J.C.; Paul, W.S.; Piesman, J. Reported distribution of Ixodes scapularis and Ixodes pacificus (Acari: Ixodidae) in the United States. J. Med. Entomol. 1998, 35, 629–638. [Google Scholar]

- Goddard, J. Ecological studies of Ixodes scapularis (Acari: Ixodidae) in central Mississippi: Lateral movement of adult ticks. J. Med. Entomol. 1993, 30, 824–826. [Google Scholar]

- Lane, R.S.; Mun, J.; Stubbs, H.A. Horizontal and vertical movements of host-seeking Ixodes pacificus (Acari: Ixodidae) nymphs in a hardwood forest. J. Vector Ecol. 2009, 34, 252–266. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, Y.; Fu, J.S.; Drake, J.B.; Liu, Y.; Lamarque, J.F. Projected changes of extreme weather events in the eastern United States based on a high resolution climate modeling system. Environ. Res. Lett. 2012, 7, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Goosse, H.; Barriat, P.Y.; Lefebvre, W.; Loutre, M.F.; Zunz, V. Chapter 6. Future Climate Changes. Introduction to Climate Dynamics and Climate Modeling. Available online: http://www.climate.be/textbook (accessed on 1 March 2012).

- Grenfell, B.T.; Bjornstad, O.N.; Kappey, J. Travelling waves and spatial hierarchies in measles epidemics. Nature 2001, 414, 716–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Recommendations for the Use of Lyme Disease Vaccine: Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices; CDC: Atlanta, GA, USA, 1999; p. 21.

- Lee, D. A comparison of conditional autoregressive models used in Bayesian disease mapping. Spat. Spatio-Temporal Epidemiol. 2011, 2, 78–89. [Google Scholar]

- Perret, J.-L.; Guigoz, E.; Rais, O.; Gern, L. Influence of saturation deficit and temperature on Ixodes ricinus tick questing activity in a Lyme borreliosis-endemic area (Switzerland). Parasitol. Res. 2000, 86, 554–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vail, S.G.; Smith, G. Air temperature and relative humidity effects on behavioral activity of blacklegged tick (Acari: Ixodidae) nymphs in New Jersey. J. Med. Entomol. 1998, 35, 1025–1028. [Google Scholar]

- Bennet, L.; Halling, A.; Berglund, J. Increased incidence of Lyme borreliosis in Southern Sweden following mild winters and during warm, humid summers. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. D. 2006, 25, 426–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogden, N.H.; Bigras-Poulin, M.; Hanincova, K.; Maarouf, A.; O’Callaghan, C.J.; Kurtenbach, K. Projected effects of climate change on tick phenology and fitness of pathogens transmitted by the North American tick Ixodes scapularis. J. Theor. Biol. 2008, 254, 621–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adler, F.R.; Pearce-Duvet, J.M.C.; Dearing, M.D. How host population dynamics translate into time-lagged prevalence: An investigation of Sin Nombre virus in deer mice. Bull. Math. Biol. 2008, 70, 236–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobson, A. Population dynamics of pathogens with multiple host species. Amer. Naturalist 2004, 164, S64–S78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiffner, C.; Zucchini, W.; Schomaker, P.; Vor, T.; Hagedorn, P.; Niedrig, M.; Rühe, F. Determinants of tick-borne encephalitis in counties of southern Germany, 2001–2008. Int. J. Health Geogr. 2010, 9, 42–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostfeld, R.S.; Canham, C.D.; Oggenfuss, K.; Winchcombe, R.J.; Keesing, F. Climate, deer, rodents, and acorns as determinants of variation in Lyme-Disease risk. Plos. Biol. 2006, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lane, R.S.; Quistad, G.B. Borreliacidal factor in the blood of the western Fence Lizard (Sceloporus occidentalis). J. Parasitol. 1998, 84, 29–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, J.H.; Cummins, G.A.; Joiner, M.S. Immature Ixodes scapularis (Acari: Ixodidae) parasitizing lizards from the southeastern USA. J. Parasitol. 1993, 79, 684–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gething, P.; Patil, A.; Smith, D.; Guerra, C.; Elyazar, I.; Johnston, G.; Tatem, A.; Hay, S. A new world malaria map: Plasmodium falciparum endemicity in 2010. Malar. J. 2011, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boender, G.J.; van Roermund, H.J.; de Jong, M.C.; Hagenaars, T.J. Transmission risks and control of foot-and-mouth disease in The Netherlands: spatial patterns. Epidemics 2010, 2, 36–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, D.; Randolph, S. Climate change and vector-borne diseases. Advan. Parasitol. 2006, 62, 345–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniels, T.J.; Falco, R.C.; McHugh, E.E.; Vellozzi, J.; Boccia, T.; Denicola, A.J.; Pound, J.M.; Miller, J.A.; George, J.E.; Fish, D. Acaricidal treatment of white-tailed deer to control Ixodes scapularis (Acari: Ixodidae) in a New York Lyme disease-endemic community. Vector-Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2009, 9, 381–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garnett, J.M.; Connally, N.P.; Stafford, K.C., III; Cartter, M.L. Evaluation of deer-targeted interventions on Lyme disease incidence in Connecticut. Public Health Rep. 2011, 126, 446–454. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, E.B.; Piesman, J. How can we prevent Lyme disease? N. Engl. J. Med. 2003, 348, 2424–2430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2013 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).

Share and Cite

Dhingra, R.; Jimenez, V.; Chang, H.H.; Gambhir, M.; Fu, J.S.; Liu, Y.; Remais, J.V. Spatially-Explicit Simulation Modeling of Ecological Response to Climate Change: Methodological Considerations in Predicting Shifting Population Dynamics of Infectious Disease Vectors. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2013, 2, 645-664. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijgi2030645

Dhingra R, Jimenez V, Chang HH, Gambhir M, Fu JS, Liu Y, Remais JV. Spatially-Explicit Simulation Modeling of Ecological Response to Climate Change: Methodological Considerations in Predicting Shifting Population Dynamics of Infectious Disease Vectors. ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information. 2013; 2(3):645-664. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijgi2030645

Chicago/Turabian StyleDhingra, Radhika, Violeta Jimenez, Howard H. Chang, Manoj Gambhir, Joshua S. Fu, Yang Liu, and Justin V. Remais. 2013. "Spatially-Explicit Simulation Modeling of Ecological Response to Climate Change: Methodological Considerations in Predicting Shifting Population Dynamics of Infectious Disease Vectors" ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information 2, no. 3: 645-664. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijgi2030645

APA StyleDhingra, R., Jimenez, V., Chang, H. H., Gambhir, M., Fu, J. S., Liu, Y., & Remais, J. V. (2013). Spatially-Explicit Simulation Modeling of Ecological Response to Climate Change: Methodological Considerations in Predicting Shifting Population Dynamics of Infectious Disease Vectors. ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information, 2(3), 645-664. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijgi2030645