1. Introduction

Fare evasion is a problem that affects public transport companies all over the world. It is not only an economic issue but also a social issue because it generates insecurity. This problem is usually tackled by deploying inspection actions, which can help decrease the number of transgressions and improve the feeling of security due to the presence of the inspectors [

1]. However, the efficiency of inspection actions on fare evasion is far from being consensual and the debate on its payoffs is vigorous [

2]. Results from [

3,

4] did not find a direct relationship between the percentage of fare evasions and the percentage of passengers inspected, but this was questioned by [

5,

6], who showed a that a positive correlation exists between the number of fare evasions and the number of inspections. Moreover, authors such as [

7] confirmed that an increase in the level of inspection reduces fare evasion but warn that this correlation has limits. Once a certain number of inspections has been reached, the probability of being inspected no longer works as a deterrent to fare evasion. The works developed so far are based on the standard ratio between the number of inspection actions and the number of inspection actions assuming that these two variables have a linear relationship, on a unidirectional perspective [

8]. There are some exceptions, e.g., [

9], which brought a new perspective by developing an empirical mathematical model that demonstrated that fare evasion and inspection actions could have a bidirectional relationship.

Another issue is that the samples are usually quite small, which raises questions about their representativity. The small sample size is an obstacle to detailed studies and the exact location of the problems. The extensive review of [

10] identified several works focused on deterrence and the largest sample belonged to a work that checked 75,000 passengers [

11]. More recently, reference [

12] addressed these issues based on a very large sample, having found that, alongside the inspection/detection nexus, spatial factors also play a role in predicting evasion detection. The authors of [

13,

14,

15,

16] concur with the spatial dimension of fare evasion, having identified hotspots in their studies, defined as passenger volumes versus fare evasion levels.

Given that evidence mounts on the existence of a relationship between inspection actions and detected evasion and its spatial dependence, the question of how it can be used to improve the effectiveness and efficiency of inspection policies arises. Harnessing the potential of spatial statistics is a possible next step towards mitigating the phenomenon, a step that, to the best of the authors’ knowledge, has not yet been taken in the literature. Accordingly, the present article proposes a methodology that can help fill this literature gap.

Starting from the database of [

12] on bus lines fare evasion, the extent of the association between inspection and detection is firstly tested spatially, after which the marginal gains of inspective actions are derived, and inspector (re)allocation is analyzed on that basis. In particular, this article intends to answer the following research questions:

Q1. Is the association between inspective actions and detected fare evasion widespread in the city of Lisbon, Portugal, or are there locations where it is not locally supported?

Q2. How should inspector teams be relocated, considering the spatial heterogeneity in the effectiveness of inspection actions, to improve detection counts and thereby strengthen their deterrent effect?

The answers to these questions serve two research objectives: to contribute to the literature regarding fare evasion and to provide policy feedback to public transport companies about the impacts of inspection actions and how can inspectors be best distributed throughout the territory. Note that scheduling inspector teams under realistic conditions is an important line of research, as recognized in [

8]. The present article rises to this need for developing scientifically sound and practical, scalable methods to do so.

The proposed methodology makes use of two spatial statistics methods, namely, entropy-based local bivariate relationships (LBR) [

17] and geographically weighted regression (GWR), which are applied to a very large database consisting of 1.84 million inspection actions carried out in the year of 2019 in Lisbon, Portugal. It should be noted that this sample is significantly larger than those used in previous works, making it possible to separate the analysis by time periods and determine whether they play a role.

4. Results

In applying the methodology, calculations were carried out in Esri ArcGIS Pro 3.1.0 and R 4.4.1. The former was used to present the results in map format.

Both the LBR and GWR used a bandwidth of the closest 30 neighbours, a commonly used value for these methods that is further justified by the fact that adding more neighbours would incorporate observations from increasingly heterogeneous geographic contexts, which might dilute local patterns. The weighting schemes were minimum spanning trees for LBR [

17] and Gaussian weighting for GWR.

In defining the closest neighbours, straight-line distance was adopted because it provides a more parsimonious representation of local proximity. Network-based distances would require additional behavioural assumptions regarding movement and access that could not be justified a priori. While network distance may be relevant in some contexts, straight-line distance was considered more appropriate for characterizing local neighbourhood effects in this study.

Concerning data curation, bus stops with zero inspections were removed and data for each stop and time slot was aggregated into a tuple containing the cumulative counts of inspection actions and detected evaders throughout the whole year of 2019.

4.1. Local Bivariate Relationships (LBR)

Figure 2 maps exhibit LBR findings on the inspections/detections association and

Table 2 summarizes them. In the map, dots correspond to bus stops where inspections were carried out, and their colour represents the statistical significance of the association between the two variables. The threshold for significance was set at 5%.

Two main observations emerge from the maps. The first is that, indeed, inspection actions and detected evasion are strongly associated overall, with highly significant p-values in all but a few locations. This global trend can be loosely described as “discovery bias”, meaning the more one looks for evasion, the more evasion one will find.

The second observation concerns the places where the LBR association is not as strong as the general tendency. Small pockets of lower significance and non-significance can be found in the evening periods (17–20 h, 20–0 h). The breaking down of the association suggests that changing the number of inspections might not directly translate into more or less detected evaders. For the 17–20 h slot, there are two locations at which this happens (southwest, near Restelo/Ajuda, and northeast, near Oriente), suggesting there may be a spatial reason for it. In the Restelo/Ajuda area, the reason might be the presence of a large nearby urban park, which leads to spatially sparser inspections. As such, larger neighbourhoods form around each stop (recall that 30 nearest neighbours are needed), mixing more local trends and thus making it harder to identify a well-defined relationship. In the Oriente area, bus stop density is higher, so non-significance there might be structural or perhaps due to the border effects mentioned below in

Section 4.2. For 20–0 h, the Restelo/Ajuda cluster shifts to the west and again likely appears due to sparsity. Other non-significant locations appear to be somewhat scattered around the city, suggesting isolated reasons for it.

Recall that local entropy uses information from neighbours, so non-significance (or significance, for that matter) tends to form clusters, as the maps confirm. Note also that higher levels of entropy correspond to a decrease in the ability to predict the number of evasions.

Table 2 shows that entropy values tend to be low, as association is strong overall, signalling that inspection actions have a high capacity to predict detected evasion.

In a nutshell, the LBR found widespread significant association between inspections and detections, showing that the next step of running a GWR to find the strength of that association rests on solid grounds and can be relied upon, with some reservation around the non-significant clusters.

4.2. Geographically Weighted Regression (GWR)

After running the linear and quadratic GWR, their respective local corrected AIC values were calculated, and the rule of expressions (2) was applied. This led to the linear GWR being the preferred model, except for a very small number of cases scattered throughout the city.

Figure 3 shows the outcome in map form, which exhibits very little clustering of locations where the quadratic GWR was preferred. This suggests that non-linear spots could be appearing due to statistical fluctuations, rather than being related to some spatial pattern. The fact that the vast majority of bus stops are compatible with a linear GWR is evidence that inspection frequency is relatively low overall, away from a transition to non-linear saturation effects that might stem from more intensive inspection actions.

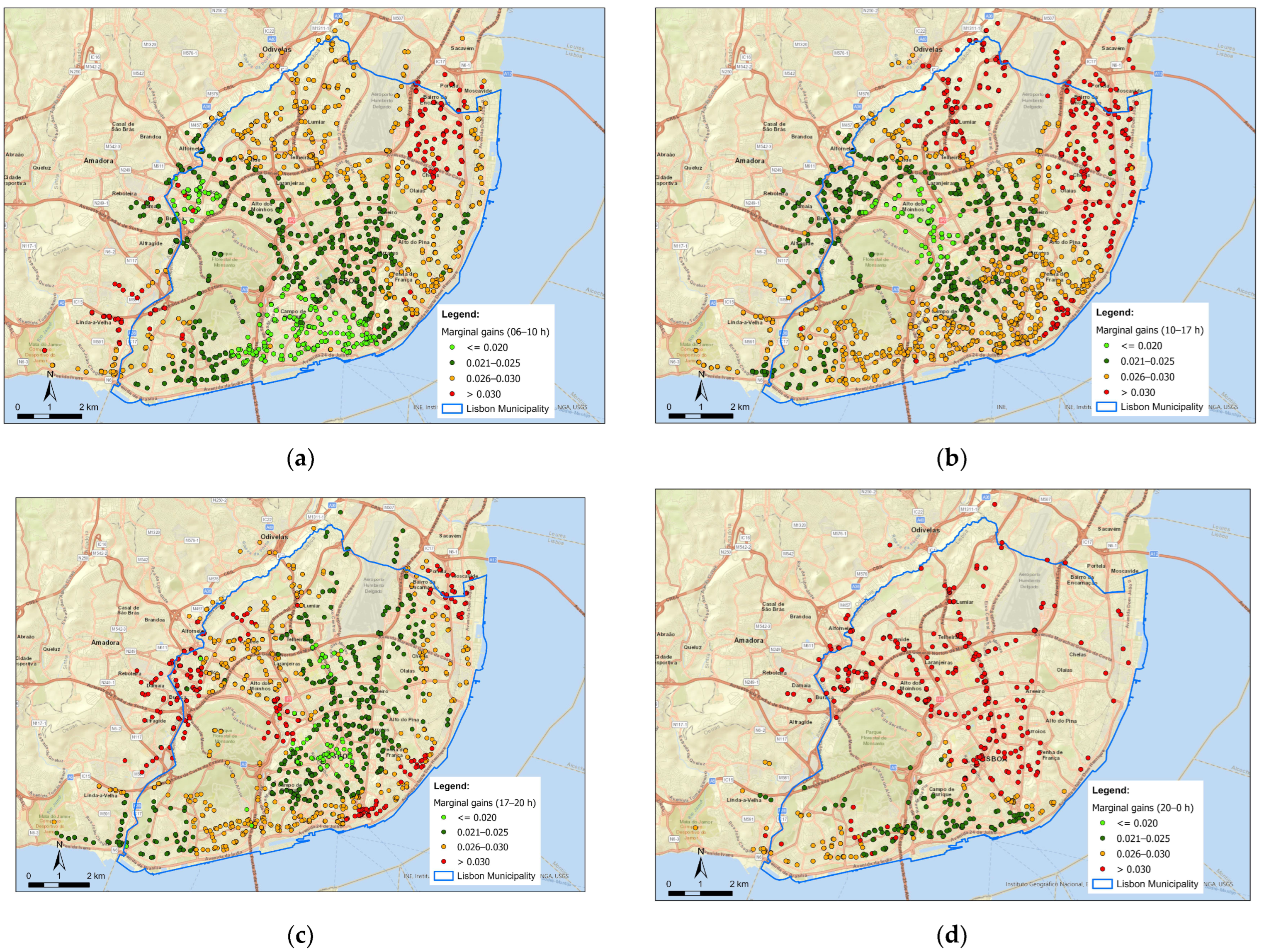

Marginal gains for each location were then calculated depending on the nature of the GWR model selected for that location (linear/quadratic) by applying expressions (3a) and (3b), leading to the maps of

Figure 4, and the summarizing statistics of

Table 3. Note that statistics on adjusted

R2 values indicate that the GWR model is a good fit to the data.

A global overview of the maps reveals smaller marginals at centre of the city for the daytime slots, suggesting higher deterrence in the kernel of the city, and supporting, in general, some relocation to the outskirts and east riverside. For the early night (20–0 h) time slot, the situation is different, and this time the centre appears to be under surveillance. This pattern shift in the early night suggests dynamic effects are present and that spatial drivers of evasion need to be complemented to obtain the full picture. This is discussed in more detail in

Section 5.

As is common in spatial analyses, the results could have potential biases due to border effects. Bus stops near the borders have their neighbourhoods formed mostly from interior points, which might distort local estimates. Nevertheless,

Figure 2,

Figure 3 and

Figure 4 show no clear evidence of pronounced border effects, so any resulting imprecisions and uncertainties are likely to be small.

Note also that bus stop density is variable, which can lead to some neighbourhoods stretching out to locations with different socio-economic contexts. However, since the weight of far-away locations is smaller in GWR, this effect is also expected to be limited.

Finally, as may occur with GWR methods, some residual spatial autocorrelation may persist. However, as reported in [

12] using alternative methods, its influence is likely mild.

5. Discussion

The critical analysis of the outcome requires first combining the LBR findings with the GWR results and then observing the marginal gains spatial patterns and formulating possible improvements to the inspection strategies. The final step is to formulate general value judgements on the spatial non-stationarity and heterogeneity of marginal gains.

5.1. Connecting LBR and GWR Results

The strong association between inspections and detections found by the LBR suggests that globally the GWR applies to the whole of the city for all time slots, with some caution warranted for the early night period (20–0 h). This provides a tentative answer to research question Q1: “Yes, the association is widespread in Lisbon, with just a few exceptions”. The same conclusion was already reached by most of the literature and what the present research adds is that, in general, the bias seems to be widespread spatially, i.e., it is systemic regardless of city or country. Thus, the degree of trust one can put on GWR results is reinforced since the LBR supports statistically significant association.

However, and more specifically, the existence of some LBR clusters of non-significance in the evening rush hour (17–20 h) and early night (20–0 h) alerts the decision-maker to be cautious about GWR results in those neighbourhoods, even if GWR goodness-of-fit indicators are acceptable (e.g., local adjusted-R2). For practical purposes, this means that inspector relocation decisions on LBR non-significant clusters might be premature, despite GWR suggesting some sort of action.

One possible managerial decision for overcoming non-significance may be to intensify and/or densify inspection actions at the corresponding locations in order to assess whether a significant association develops when more data are considered.

5.2. Spatial Patterns of Marginal Gains: Type of Relationship

With the above proviso, the general picture can be obtained from the maps of

Figure 3 and

Figure 4. Concerning the type of association, the landscape shown by the GWR is that of a ubiquitous linear relation between inspections and detections. The current situation is thus far from the saturation found by [

7] and further inspections are likely to increase detection counts proportionally.

On the locations for which a quadratic model was preferred, the situation is slightly different, with negative suggesting saturation and positive suggesting reinforcing inspections. However, the number of locations with quadratic GWR is generally small and scattered and therefore should be complemented with more evidence before making decisions.

5.3. Spatial Patterns of Marginal Gains: Inspection Allocation Strategies

Marginal gains maps, which apply to both GWR types, are the main tool for designing inspector relocation strategies.

An overall look at all the time slots of

Figure 4 shows that, except for the early night slot (20–0 h), the marginal gains on the centre of Lisbon are smaller than next to the riverside. The situation on the outskirts, i.e., locations next to the municipality line, is variable and will be analyzed case-by-case below. Before suggesting inspector relocations, it is useful to look at the actual values of marginal gains. These mostly oscillate around ± 0.01 (see legends), which translate into 1 extra detection per 100 inspection actions. It is up to the transport companies to assess the corresponding operational impact, knowing that this nevertheless corresponds to ±50% effectiveness of the inspection actions, i.e., marginals of 0.02 (light green dots) as compared to 0.03 (red dots).

Moving on to a more detailed analysis and starting with the morning rush hour (6–10 h), the low marginals of downtown areas around south riverside might be explained by the presence of several public transport multimodal hubs. While this is a natural location to allocate inspectors in the morning because of commuting, it is possible that the company is overdoing it, as higher gains might be had in the east riverside area, where another large multimodal hub exists.

For the 10–17 h slot, some relocation from the centre to the east riverside and to the northern Lumiar/Odivelas zone might be advisable. Although the map for this time slot appears somewhat different to the eye, the relocation advice is actually similar.

For the 17–20 h slot, a pattern similar to the earlier time slots emerges, in that the centre has smaller marginals. The relocation suggestion here is towards the western Damaia/Buraca outskirts and southeast riverside. The east riverside zone also might also lead to more detections, but given that the 17–20 h LBR is non-significant for several bus stops of this zone, it is probably best to concentrate efforts on the other locations first and monitor the evolution of the situation for the east riverside.

Finally, for the 20–0 h slot, the pattern is somewhat the opposite of the previous one: marginals in the south riverside are lower and it is along the centre that the most potential gains lie. It might be that the transport company is focusing too much on the south riverside, possibly in response to population flows to that area, which has many touristic and nightlife amenities, neglecting the centre in the process and leaving it more prone to opportunistic evaders. The LBR is non-significant in a few spots in this time slot, but overall, it does not change the suggestion to move some inspectors back to the centre.

The pattern differences between all time slots show that it is important to consider the time element whenever the databases are large enough to permit splitting the data into day periods. As the above considerations show, the plus-value of doing so lies in the design of time-specific adjustment strategies which match the transport company operational schedules.

Summarizing the above, and answering research question Q2 in the process, i.e., “How should inspector teams be relocated?”, the maps of

Figure 4 provide a general picture of how that relocation might be performed: from green to red spots. A finer-grained analysis is possible, which is to sort the marginal gains and move inspectors from the

N stops with the lowest marginal values to the

N stops with the highest values. Note that these relocation schemes are very practical and scalable and can therefore be used by just about every transport company around the world, adding to the value of the present research.

5.4. Spatial Non-Stationarity and Heterogeneity Considerations

Looking at all patterns from a spatial perspective, the daytime periods (6–20 h) exhibit a similar spatial structure of marginal gains, suggesting that the outskirts and suburbs warrant a reinforcement of inspection actions. It might be tempting to interpret this as an intrinsic tendency of higher evasion rates in those locations, but the early night period (20–0 h) shows the opposite trend, a trend which should not be ignored but rather interpreted in context. By doing this and taking a broader view, a picture forms: the results arguably suggest that the spatial patterns uncovered by the GWR-estimated marginal gains exhibit dynamic non-stationarity, in that the effectiveness of inspection actions varies across space and time rather than just space alone. This indicates the presence of context-dependent enforcement regimes that shift by time of day. In other words, spatial non-stationarity in inspection effectiveness emerges from the interaction between inspection strategies, local urban context, and time of day, rather than reflecting a fixed spatial mechanism. From the point of view of law enforcement, this interplay warns transport companies not to rely solely on spatial factors for planning inspection strategies and be attentive of evidence obtained in the field to constantly adjust those strategies.

Note that accounting for time dependence was very important in reaching the above picture: bundling all time periods into a single model would mask these contextual differences and could lead to misleading conclusions for both spatial drivers of evasion and inspector allocation.

5.5. Inspection Policy Implications

The results support two main policy implications for the transport company. One is that the overwhelming dominance of linear relationships between inspections and detections gives justification for hiring new inspectors. Indeed, just about everywhere in the city, the data shows that the number of inspection actions is far from saturation. Therefore, the addition of inspectors will, in all likelihood, lead to proportionally more detections. However, it is worth noting that making inspection actions more visible may also increase the deterrent effect. As [

9] argued, deterrence comes primarily from passengers’ perception of inspection, that is, if they feel there is a high probability of being inspected and fined if transgressing. Given that inspection actions by this particular transport operator typically have high visibility among passengers, it is likely that the increasing the number of inspections can per se augment such perception. Nevertheless, a strategy of making inspections more visible and impactful may be an alternative route to reach saturation without having to recruit more inspectors. The transition from linear to non-linear behaviour could be monitored by creating delimited study areas with increased inspection rates. This would offer insights into when and how saturation may set in more generally.

The other implication is that the proposed methodology gives the decision-maker a statistical summary, i.e., a long-exposure shot of the events that took place during the data collection period. It provides guidelines for relocating inspectors and where to deploy new inspectors, should this workforce grow. However, given that a substantial share of fare evasion is opportunistic, the relocation or reinforcement of inspectors will not have a lasting effect, as opportunistic evaders are bound to shift their ways onto locations that become less surveyed. Since the inspection/detection nexus is a highly dynamic interplay that causes spatial patterns of evasion to shift constantly (sometimes even along the day), inspection strategies must adjust accordingly, and the recommendation is that the methodology is repeatedly applied on a convenient time scale. This frequent reapplication is the key for the transport company to not fall too far behind evasion patterns.

6. Conclusions

6.1. Outlook and Summary

This article set out to investigate the connection between inspection actions and detected fare evasion in the bus network of Lisbon, Portugal, and proposed a methodology based on spatial statistical methods to do so. Feeding on a large database of inspection actions by Carris, the bus transport company of Lisbon, comprising all the actions that took place in the year of 2019, the application of entropy-based local bivariate relationships (LBR) showed that inspection and detection are indeed associated almost all around the city, strengthening previous evidence on the connection between the two. Then, a geographically weighted regression (GWR) showed that the relationship is essentially linear, thus far from saturation, suggesting that additional inspectors could be incorporated into the workforce, provided the corresponding financials work in the company’s favour. Using regression results to plot marginal gains of inspection actions allowed visualizing locations where (existing or new) inspectors could be relocated to other locations with higher evasion rates, thus contributing to improved deterrence where it matters most.

The methodology proposed is a tool for transport companies to improve the effectiveness of their inspective efforts. Its pre-requisites are only databases consisting of logs of inspection actions and evasion detected, which most companies have. Given the parsimony of its requirements, it is therefore an appealing tool, with ample potential for practical use.

From a more theoretical viewpoint, results show that spatial patterns of marginal gains do exist but are very dynamic because they are the outcome of an interaction between factors such as spatial effects, time-dependent population flows, and inspection strategies. Transport companies are thus suggested to frequently update databases and revise their strategies for maximum efficiency.

6.2. Limitations and Future Work

The main limitation of the methodology is that it does not use any financial input, e.g., revenue from fines, inspector cost, evasion cost, etc., so it cannot be used from a cost–benefit perspective to find the optimal number of inspectors to assign to each location. It only suggests the origins and destinations of deployments, regardless of the origin being existing or new inspectors. The cost–benefit analysis is particularly important to consider when hiring new inspectors, so the policy implication of

Section 5.1 of reinforcing the inspection teams does not apply automatically. But if no new inspectors enter the workforce, then the methodology can be used without further ado. It should also be noted that redeploying inspectors to the suburbs can introduce operational issues that might decrease inspection efficiency, e.g., sparsity of bus stops implies more time moving between them, potentially offsetting gains from extra detections. Carrying out a full cost–benefit analysis is an interesting line of future research.

Another limitation is that the methodology cannot be applied in a static way. Since it is based on empirical data rather than first principles, and because reality is very dynamic, it requires frequent updates to the databases and model re-runs to monitor the effectiveness of inspector relocation strategies and adapt them accordingly. From a sociological point of view, since the methodology was applied to 2019, it reflects a pre-COVID reality. It would be interesting to repeat the analysis for more recent years and see what might have changed, keeping in mind that results are always an exposure shot of a very dynamic reality. Updating the study with late night periods (0–6 h) and weekend days could also shed light on fare evasion in these (far less understood) time periods.

A more theoretical approach, based on identifying spatial trends of fare evasion, could pinpoint locations where fare evasion is likely to persist, making it necessary to schedule a certain number of inspection actions to keep evasion in those places under control. This is another possible direction of research, which we hope to get back to soon.