A GIS-Based Approach to Analyzing Traffic Accidents and Their Spatial and Temporal Distribution: A Case Study of the Antalya City Center

Abstract

1. Introduction

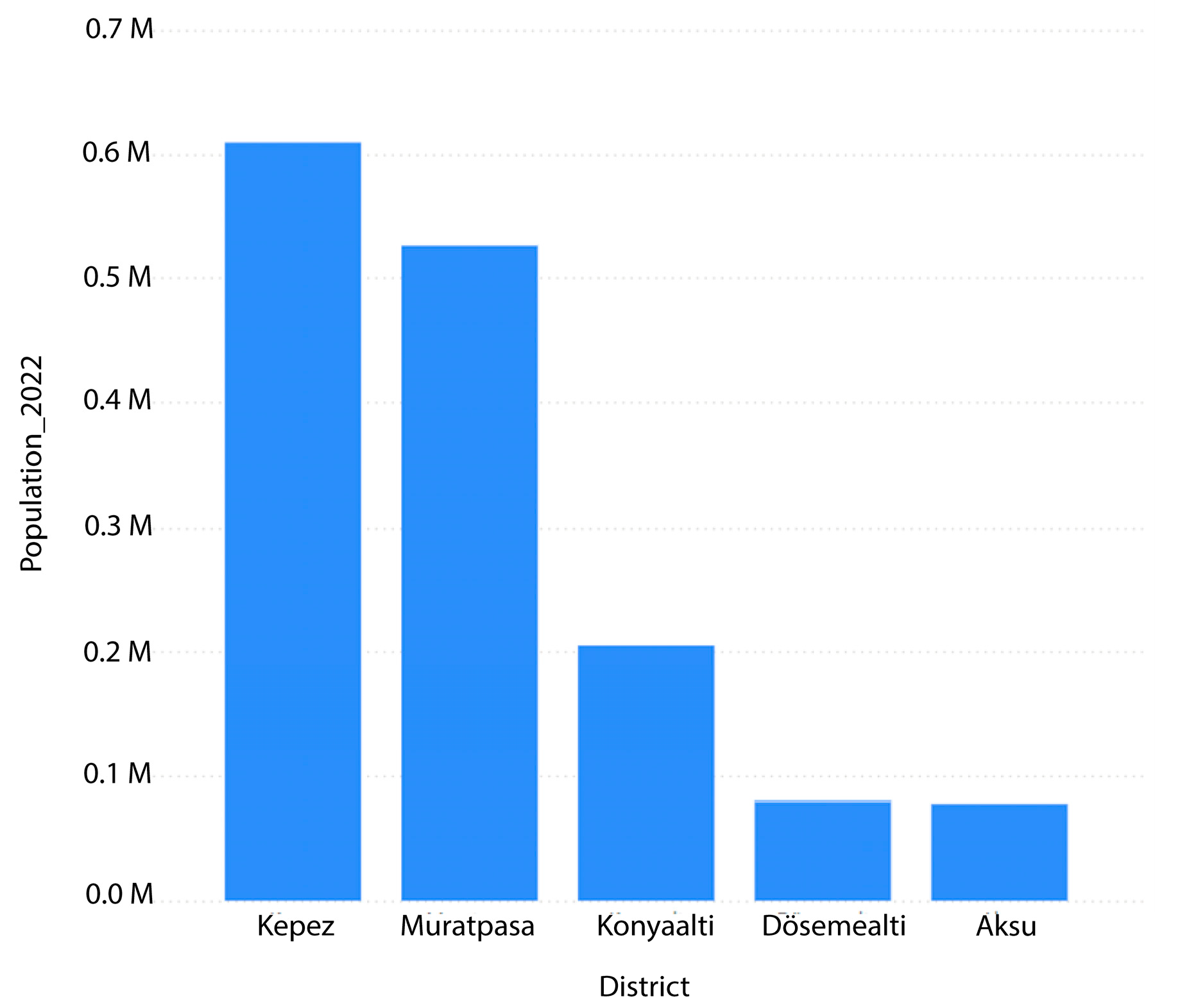

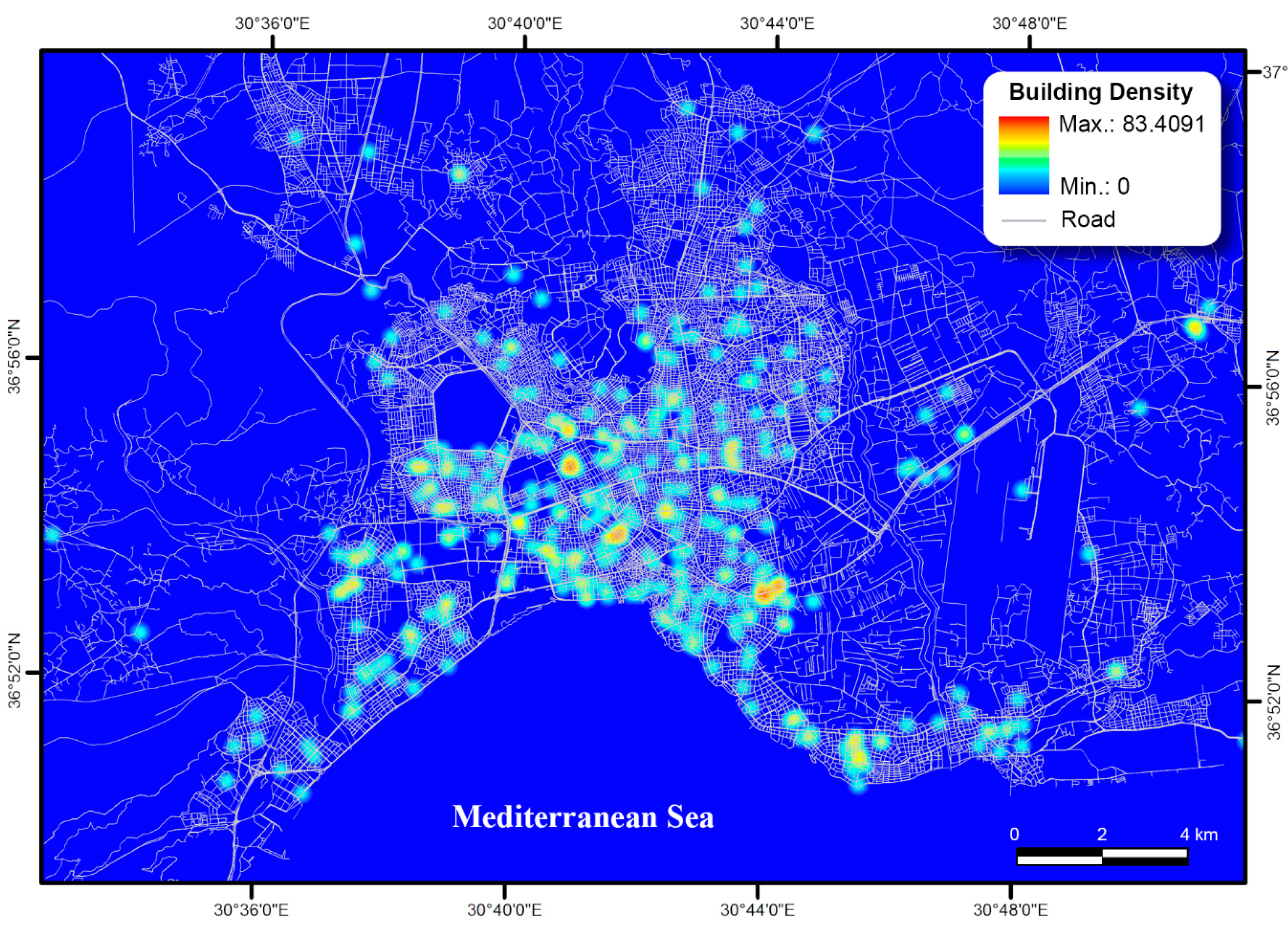

2. Study Area and Datasets

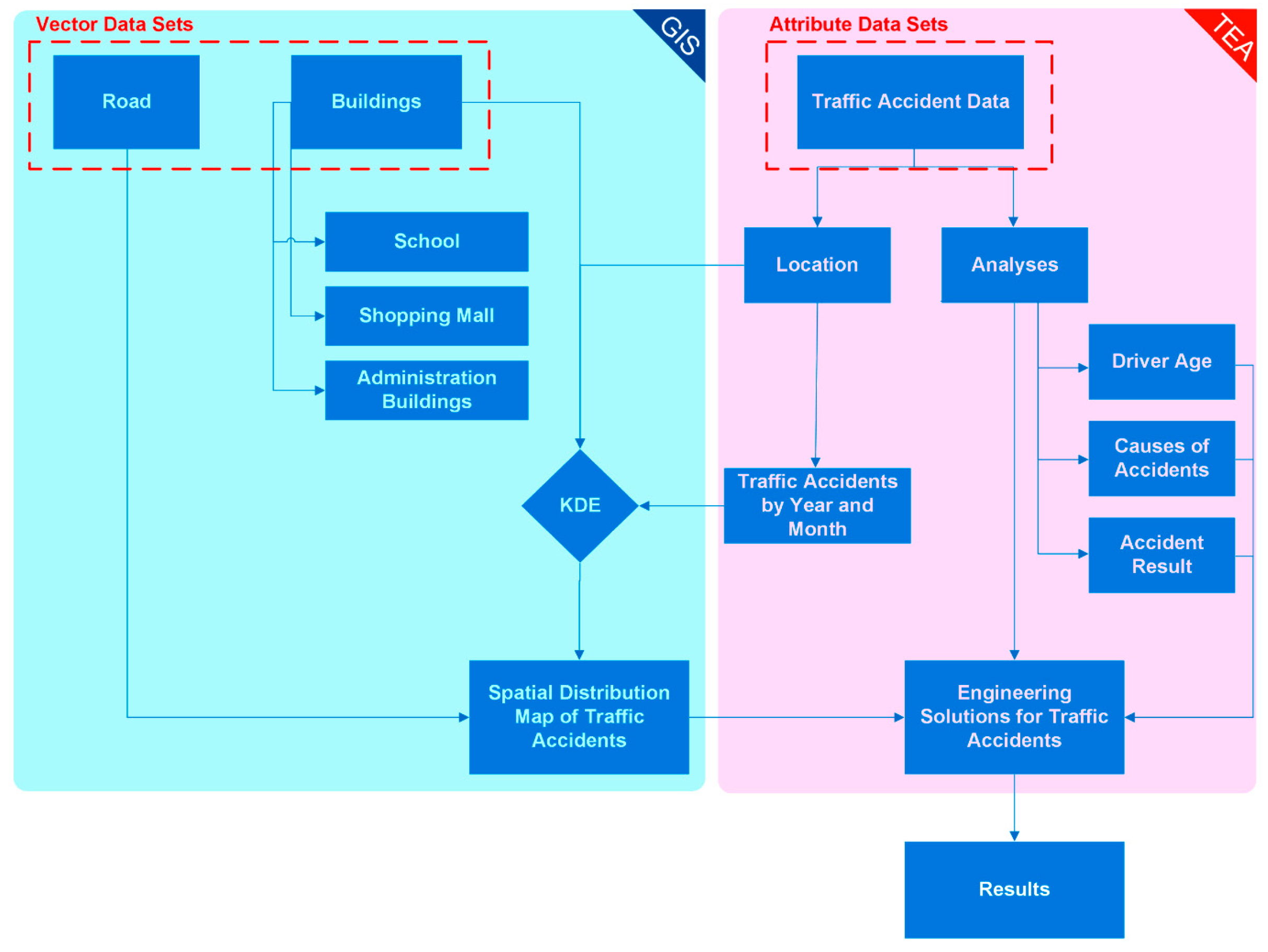

3. Methodology

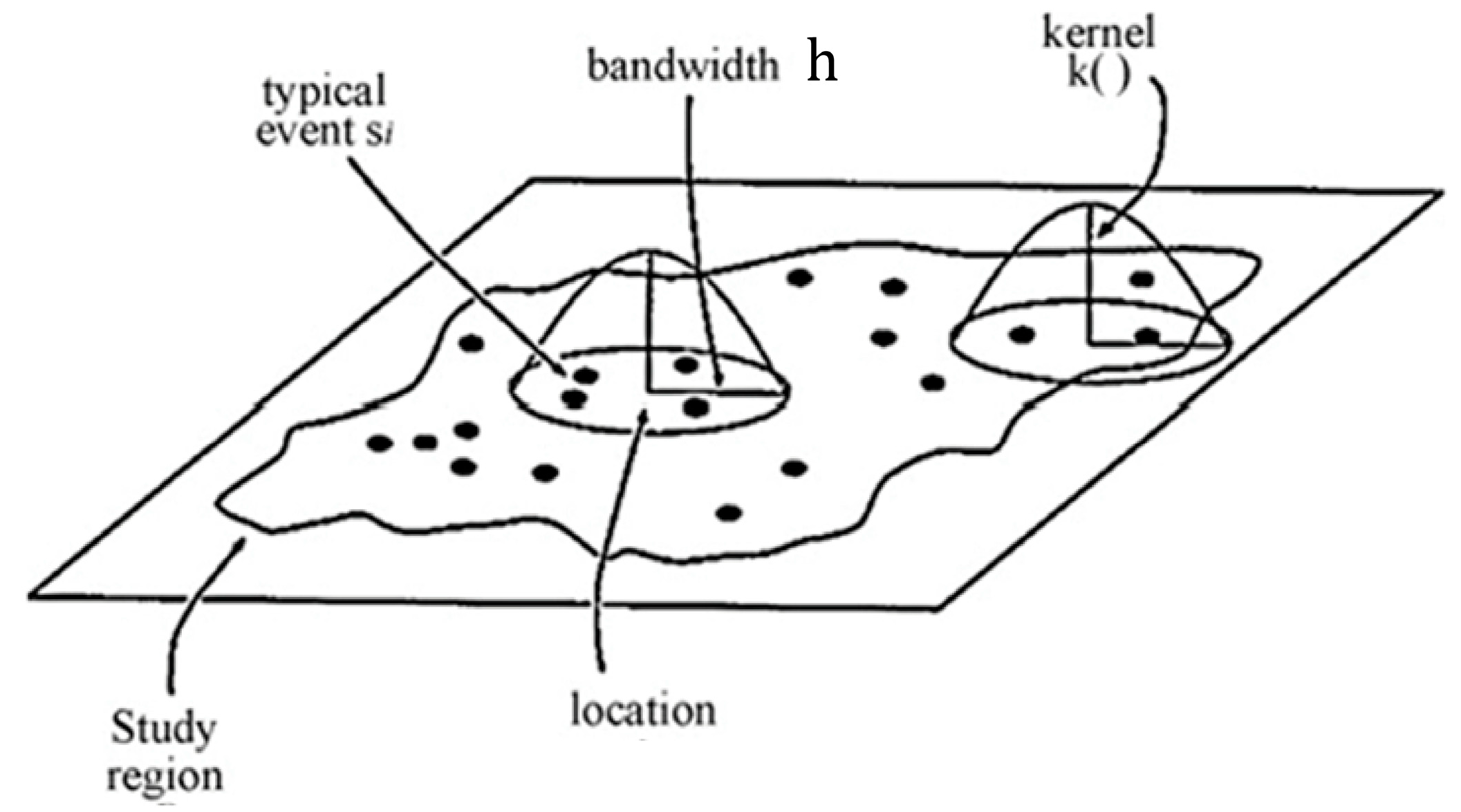

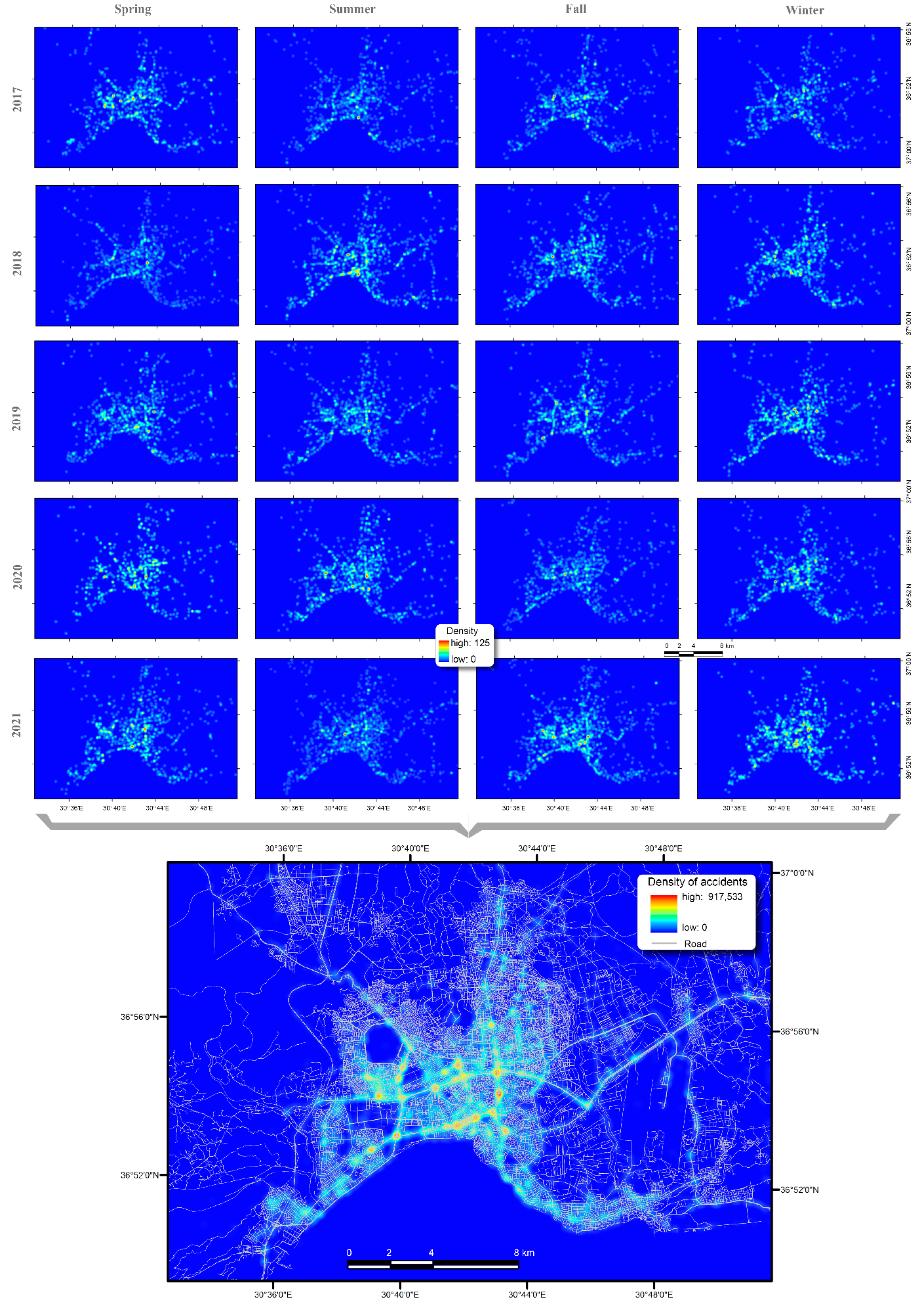

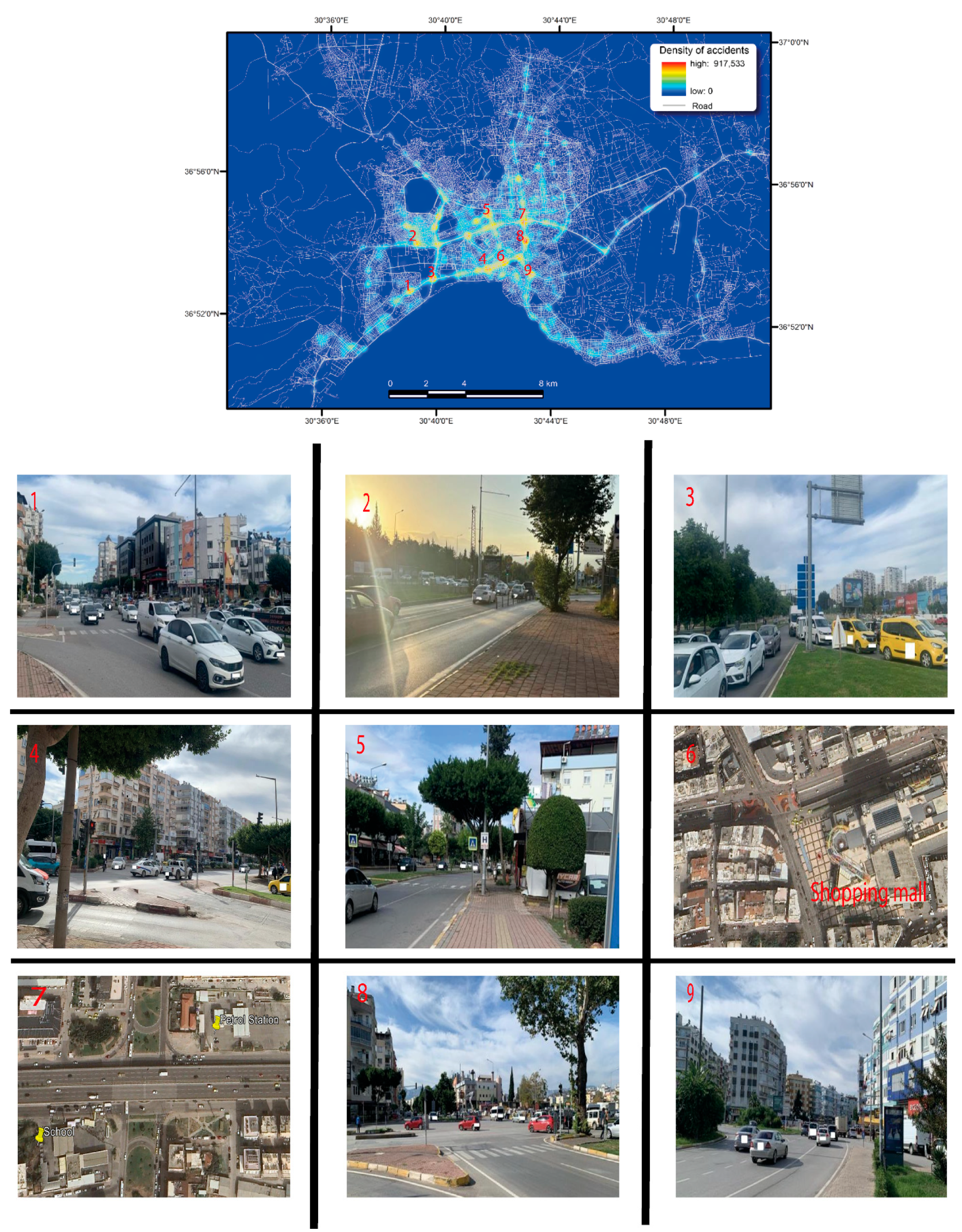

3.1. Spatial Analysis of Trafic Accidents

3.2. Statistical Analysis

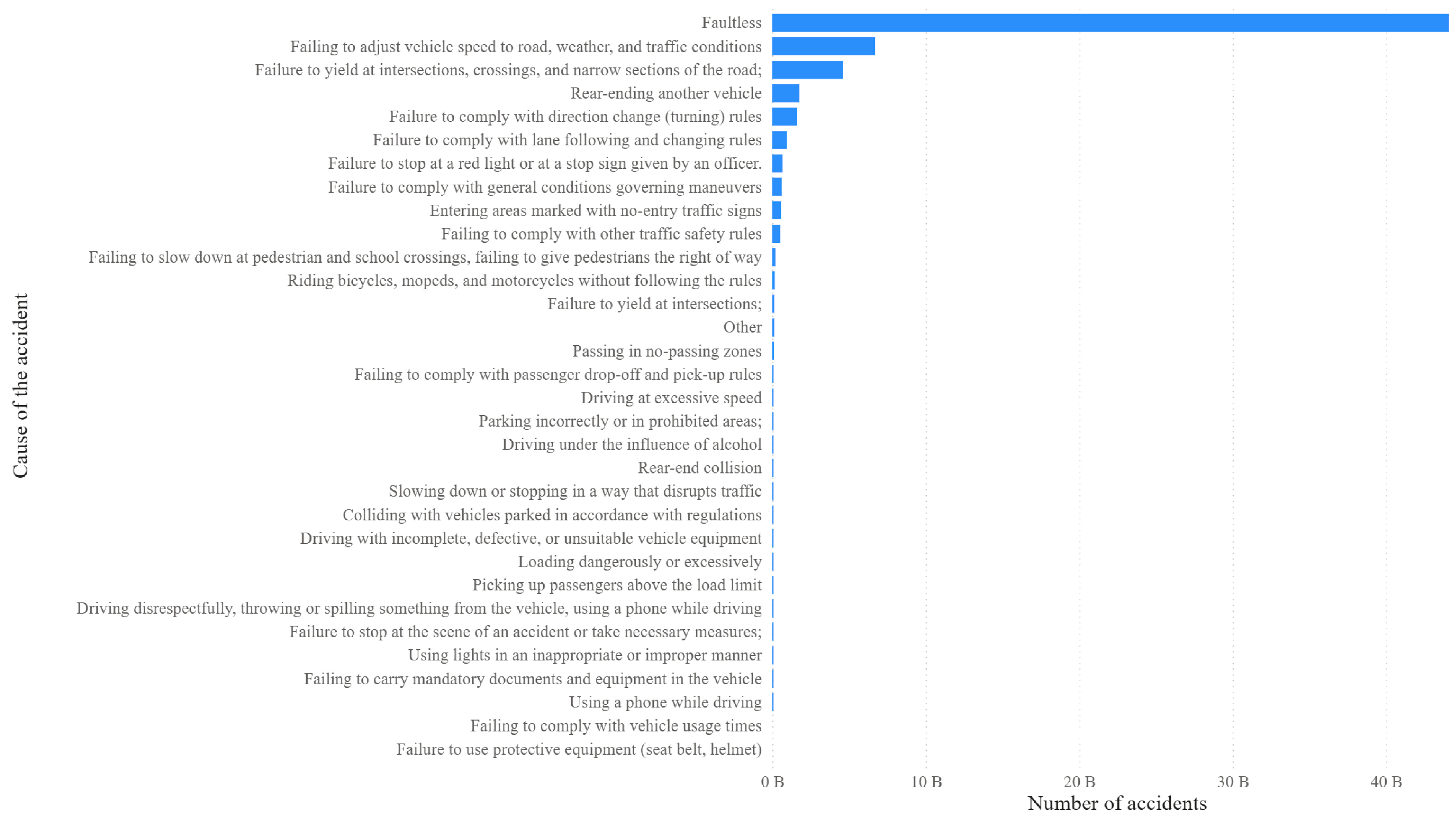

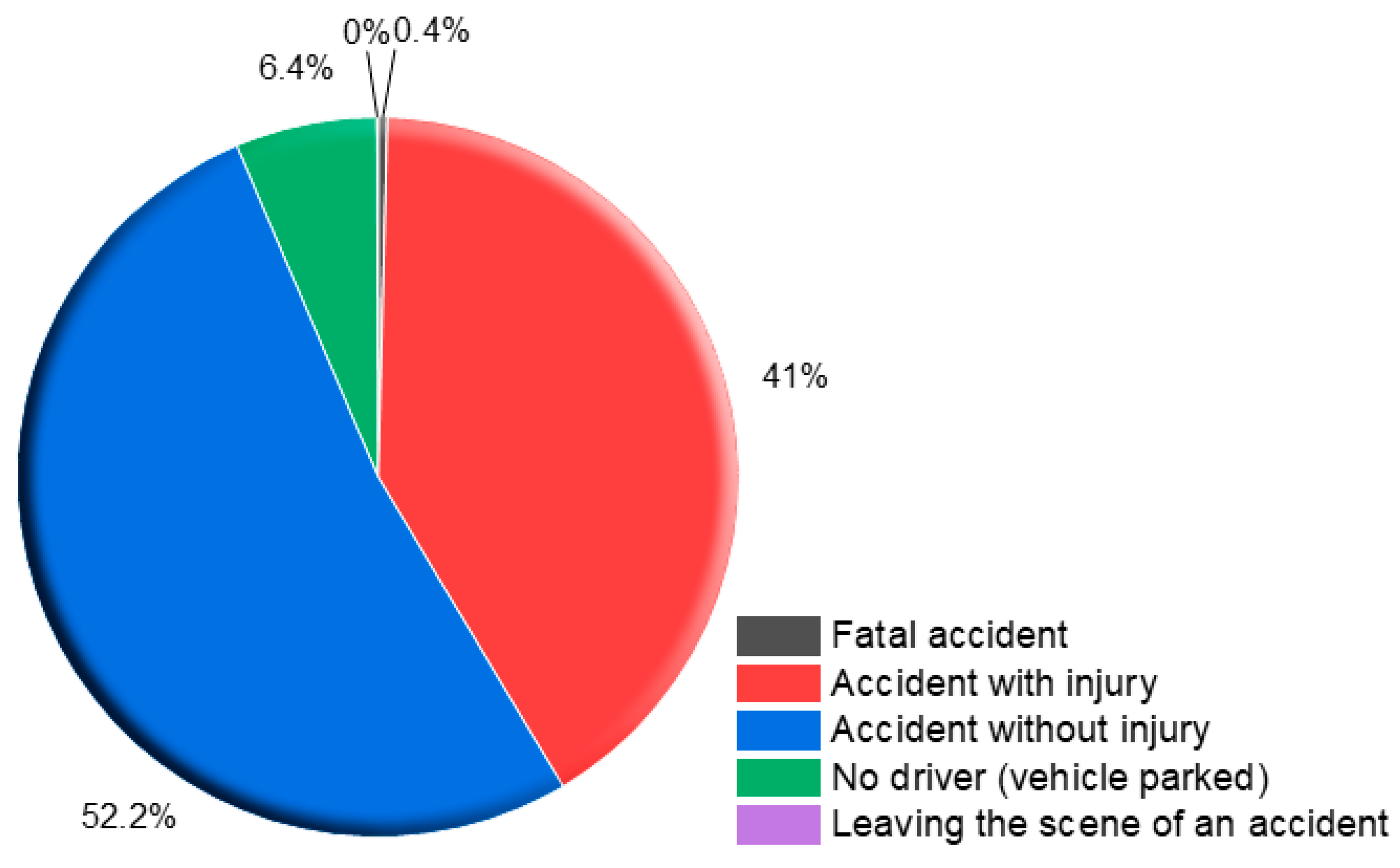

3.2.1. An Analysis of the Causes of Accidents and the Situation Resulting from Accidents

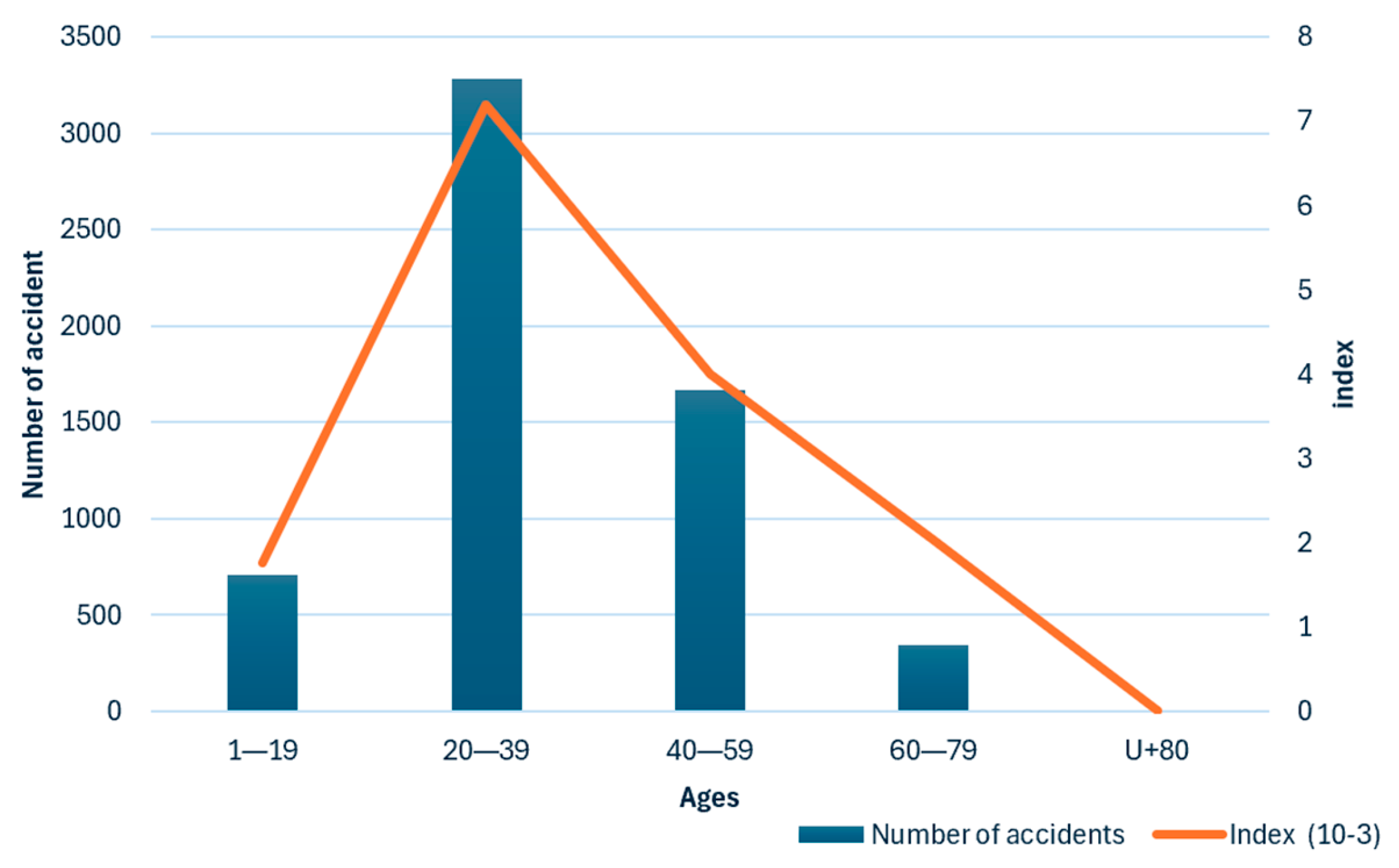

3.2.2. Distribution of Accidents by Age

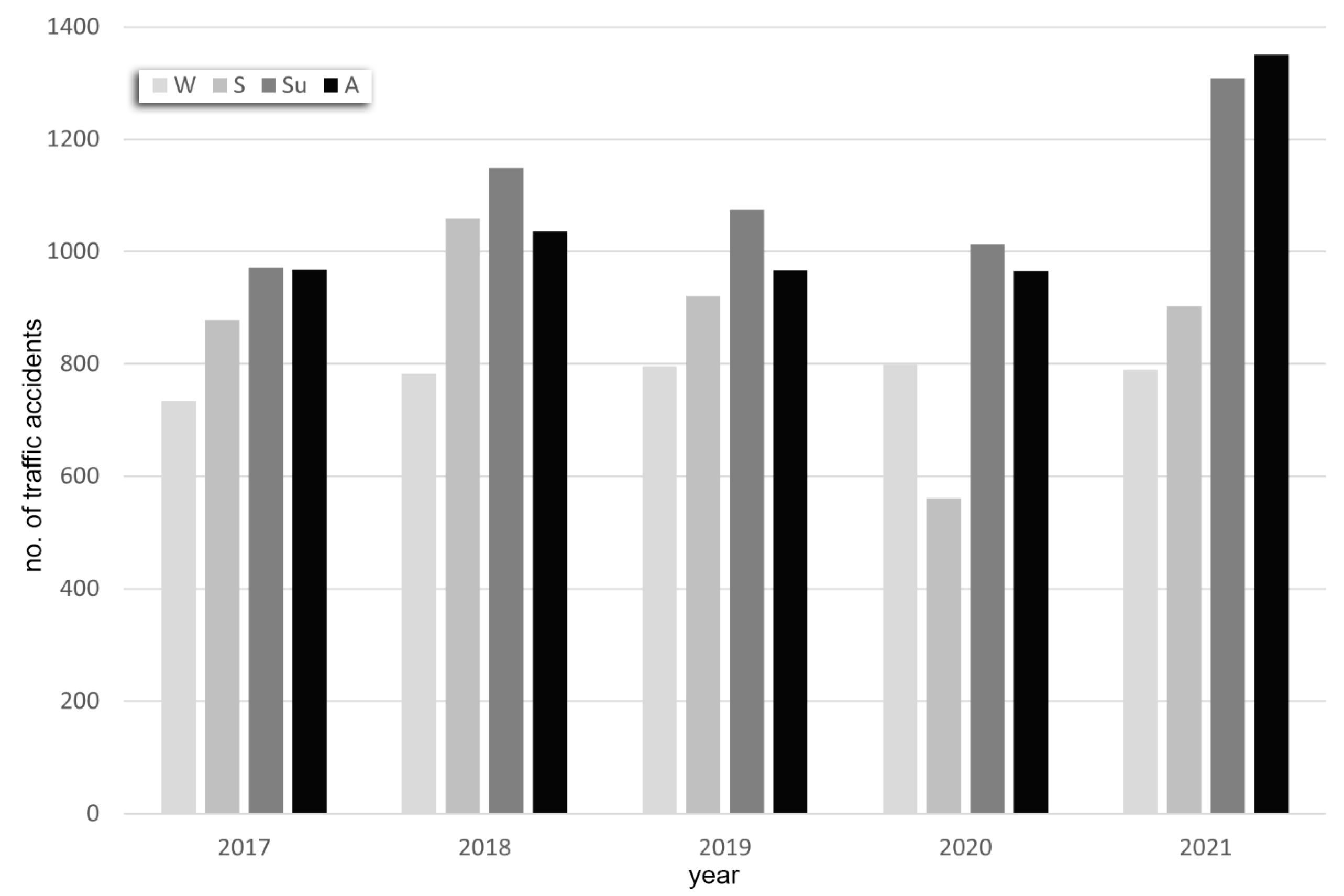

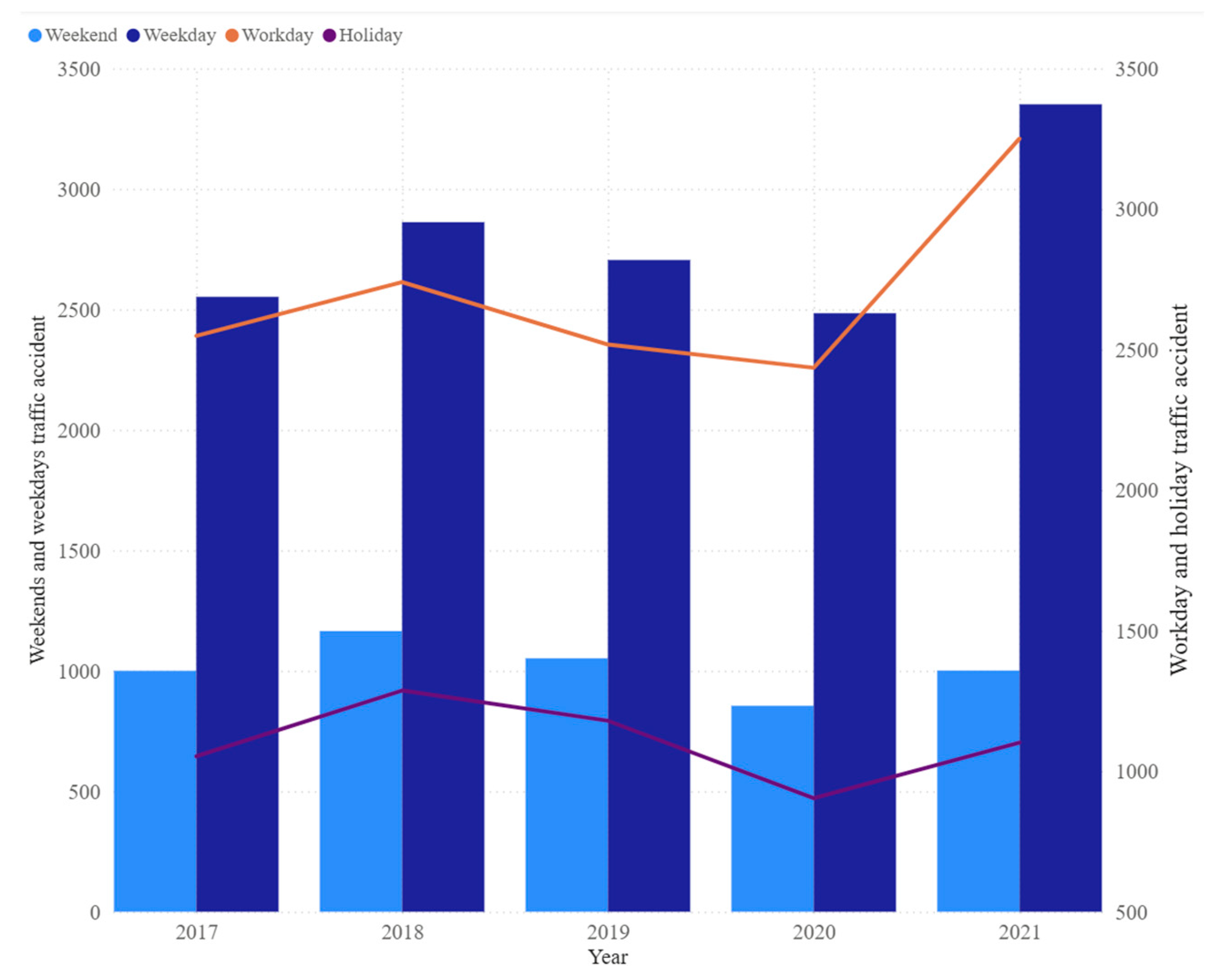

3.2.3. Periodic Analysis

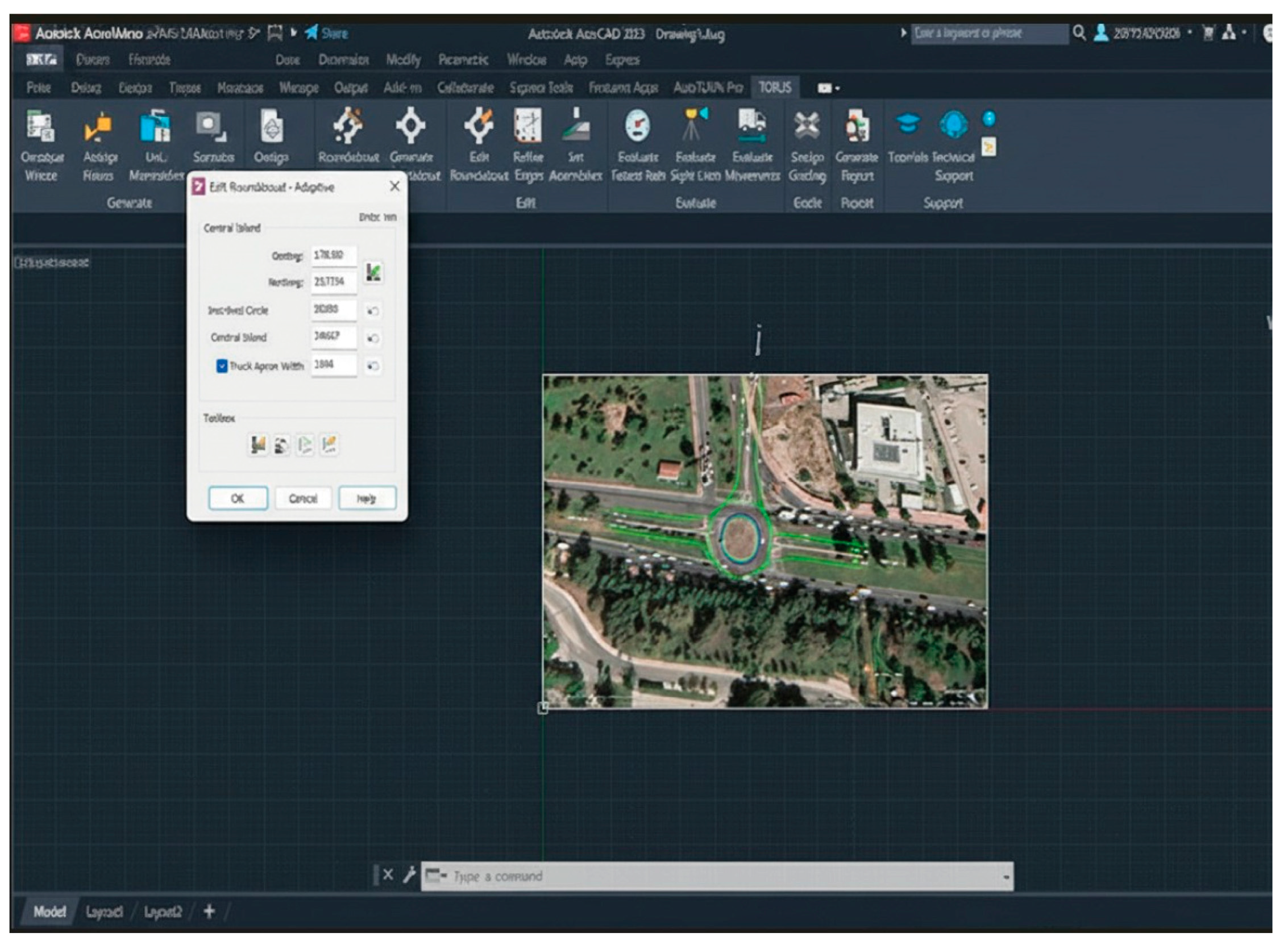

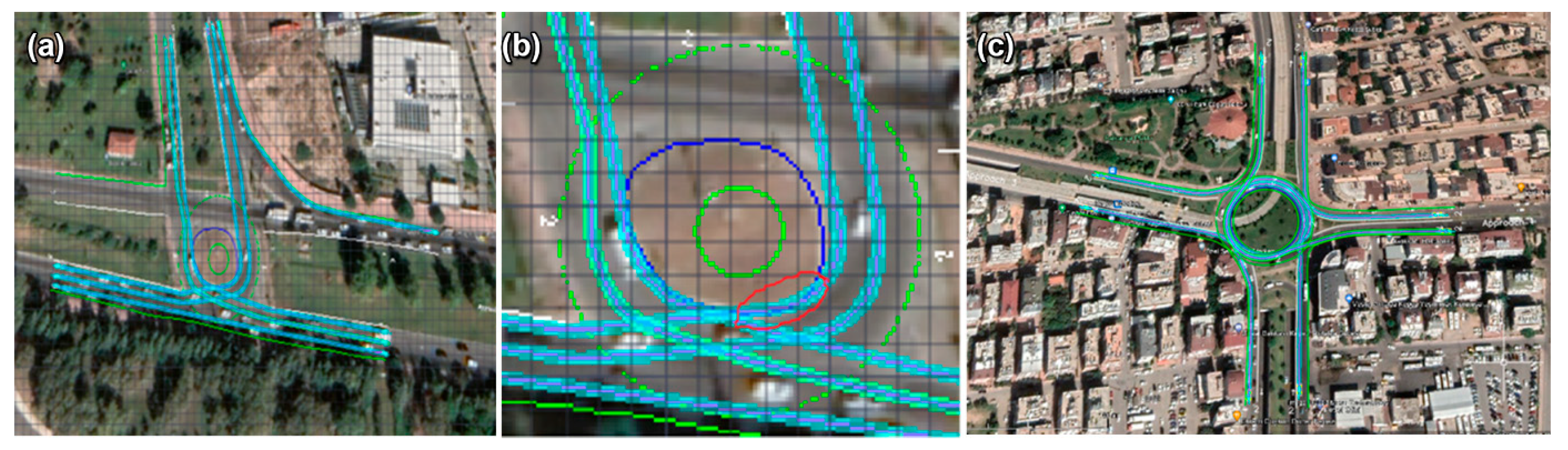

3.3. Designing Roundabout

3.4. Stopping Sight Distance

4. Results

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| GIS | Geographic Information Systems |

| GDS | General Directorate of Security |

| KDF | Kernel Density Estimation |

| Su | Summer |

| S | Spring |

| A | Autumn |

| W | Winter |

References

- Aksoy, E.; San, B.T. Geographical Information Systems (GIS) and Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis (MCDA) Integration for Sustainable Landfill Site Selection Considering Dynamic Data Source. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 2019, 78, 779–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebot Eno Akpa, N.A.; Booysen, M.J.; Sinclair, M. A Comparative Evaluation of the Impact of Average Speed Enforcement (ASE) on Passenger and Minibus Taxi Vehicle Drivers on the R61 in South Africa. J. S. Afr. Inst. Civ. Eng. 2016, 58, 2–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beyazit, E. Achieving Sustainable Mobility—Everyday and Leisure-Time Travel in the EU. Transp. Rev. 2011, 31, 807–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loo, B.P.Y. Validating Crash Locations for Quantitative Spatial Analysis: A GIS-Based Approach. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2006, 38, 879–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivaraman, S.; Trivedi, M.M. Looking at Vehicles on the Road: A Survey of Vision-Based Vehicle Detection, Tracking, and Behavior Analysis. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2013, 14, 1773–1795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, G.; Bangdiwala, S.; Saraswat, A.; Gaurav, S. Survival Analysis: Pedestrian Risk Exposure at Signalized Intersections. Transp. Res. Part F Traffic Psychol. Behav. 2007, 10, 77–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, Q.; Alhajyaseen, W.K.M.; Brijs, K.; Pirdavani, A.; Reinolsmann, N.; Brijs, T. Drivers’ Estimation of Their Travelling Speed: A Study on an Expressway and a Local Road. Int. J. Inj. Control. Saf. Promot. 2019, 26, 216–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anonim Accidents and Injuries Statistics. Available online: https://ec-europa-eu.translate.goog/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Accidents_and_injuries_statistics&_x_tr_sl=en&_x_tr_tl=tr&_x_tr_hl=tr&_x_tr_pto=tc (accessed on 15 December 2025).

- TürkStat—Data Portal. Available online: https://data.tuik.gov.tr/Kategori/GetKategori?p=Nufus-ve-Demografi-109 (accessed on 10 December 2025).

- Clifton, K.J.; Kreamer-Fults, K. An Examination of the Environmental Attributes Associated with Pedestrian-Vehicular Crashes near Public Schools. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2007, 39, 708–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gundogdu, I.B. Applying Linear Analysis Methods to GIS-Supported Procedures for Preventing Traffic Accidents: Case Study of Konya. Saf. Sci. 2010, 48, 763–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Raemdonck, K.; Macharis, C. The Road Accident Analyzer: A Tool to Identify High-Risk Road Locations. J. Transp. Saf. Secur. 2014, 6, 130–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geymen, A.; Dedeoğlu, O.K. Coğrafi Bilgi Sistemlerinden Yararlanılarak Trafik Kazalarının Azaltılması: Kahramanmaraş Ili Örneği. Iğdır Üniversitesi Fen. Bilim. Enstitüsü Derg. 2016, 6, 79–88. [Google Scholar]

- Aghajani, M.A.; Dezfoulian, R.S.; Arjroody, A.R.; Rezaei, M. Applying GIS to Identify the Spatial and Temporal Patterns of Road Accidents Using Spatial Statistics (Case Study: Ilam Province, Iran). Transp. Res. Procedia 2017, 25, 2126–2138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayidso, T.H.; Gemeda, D.O.; Abraham, A.M. Identifying Road Traffic Accidents Hotspots Areas Using GIS in Ethiopia: A Case Study of Hosanna Town. Transp. Telecommun. 2019, 20, 123–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pleerux, N. Gis-based analysis to detect road accident hotspots using network kernel density estimation. Suranaree J. Sci. Technol. 2021, 28, 030056. [Google Scholar]

- Macedo, M.R.O.B.C.; Maia, M.L.A.; Kohlman Rabbani, E.R.; Lima Neto, O.C.C.; Andrade, M. Traffic Accident Prediction Model for Rural Highways in Pernambuco. Case Stud. Transp. Policy 2022, 10, 278–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, M.S.; Tabassum, N.J. Spatial Pattern Identification and Crash Severity Analysis of Road Traffic Crash Hot Spots in Ohio. Heliyon 2023, 9, e16303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilim, A. Identifying Unsafe Locations for Pedestrians in Konya with Spatio-Temporal Analyses. Cities 2025, 156, 105523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colak, H.E.; Memisoglu, T.; Erbas, Y.S.; Bediroglu, S. Hot Spot Analysis Based on Network Spatial Weights to Determine Spatial Statistics of Traffic Accidents in Rize, Turkey. Arab. J. Geosci. 2018, 11, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dereli, M.A.; Erdogan, S. A New Model for Determining the Traffic Accident Black Spots Using GIS-Aided Spatial Statistical Methods. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pr. 2017, 103, 106–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, K.G.; Liu, P.; Lin, L.T. Determining the Road Traffic Accident Hotspots Using GIS-Based Temporal-Spatial Statistical Analytic Techniques in Hanoi, Vietnam. Geo-Spat. Inf. Sci. 2020, 23, 153–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazmi, S.S.A.; Ahmed, M.; Mumtaz, R.; Anwar, Z. Spatiotemporal Clustering and Analysis of Road Accident Hotspots by Exploiting GIS Technology and Kernel Density Estimation. Comput. J. 2022, 65, 155–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdogan, S.; Yilmaz, I.; Baybura, T.; Gullu, M. Geographical Information Systems Aided Traffic Accident Analysis System Case Study: City of Afyonkarahisar. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2008, 40, 174–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karniadakis, G.E.; Kevrekidis, I.G.; Lu, L.; Perdikaris, P.; Wang, S.; Yang, L. Physics-Informed Machine Learning. Nat. Rev. Phys. 2021, 3, 422–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidey-Gibbons, J.A.M.; Sidey-Gibbons, C.J. Machine Learning in Medicine: A Practical Introduction. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2019, 19, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arikan Yalcin, M.; Ugur Kockal, N.I. Prediction of Properties of Fiber-Reinforced Composite Materials Using Fuzzy Method. Montes Taurus J. Pure Appl. Math. 2025, 7, 45–54. [Google Scholar]

- Li, C.; Zhang, B.; Wang, Z.; Yang, Y.; Zhou, X.; Pan, S.; Yu, X. Interpretable Traffic Accident Prediction: Attention Spatial-Temporal Multi-Graph Traffic Stream Learning Approach. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2024, 25, 15574–15586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ou, J.; Xia, J.; Wang, Y.; Wang, C.; Lu, Z. A Data-Driven Approach to Determining Freeway Incident Impact Areas with Fuzzy and Graph Theory-Based Clustering. Comput.-Aided Civ. Infrastruct. Eng. 2020, 35, 178–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Pu, Z.; Cui, Z.; Lee, S.; Guo, X.; Ngoduy, D. Inferring Heterogeneous Treatment Effects of Crashes on Highway Traffic: A Doubly Robust Causal Machine Learning Approach. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2024, 160, 104537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Zheng, Z.; Chen, X.; Ma, W.; Yang, H. Modeling the Evolution of Incident Impact in Urban Road Networks by Leveraging the Spatiotemporal Propagation of Shockwaves. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2024, 164, 104668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manap, H.S.; San, B.T. Data Integration for Lithological Mapping Using Machine Learning Algorithms. Earth Sci. Inform. 2022, 15, 1841–1859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balsak, A.; San, B.T. Evaluation of the Effect of Spatial and Temporal Resolutions for Digital Change Detection: Case of Forest Fire. Nat. Hazards 2023, 119, 1799–1818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aksoy, E.; San, B.T. Using mcda and gis for landfill site selection: Central districts of Antalya province. Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2016, XLI-B2, 151–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selim, S.; San, B.T.; Koc-San, D.; Selim, C. A Two-Level Approach to Geospatial Identification of Optimal Pitaya Cultivation Sites Using Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2025, 105, 5851–5862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- TürkStat Population Data Portal. Available online: https://www.tuik.gov.tr/ (accessed on 1 December 2023).

- Arikan Yalcin, M. Analysis of Traffic Accidents Based on Geographic Information Systems: Example of Antalya Province Central Distircts; Akdeniz University, Institute of Science: Antalya, Turkey, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, Z.; Yan, J. Detecting Traffic Accident Clusters with Network Kernel Density Estimation and Local Spatial Statistics: An Integrated Approach. J. Transp. Geogr. 2013, 31, 64–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, T.K. Kernel Density Estimation and K-Means Clustering to Profile Road Accident Hotspots. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2009, 41, 359–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anonim General Directorate of Population and Citizenship Affairs—Driver’s License. Available online: https://www.nvi.gov.tr/ssss-surucu-belgesi (accessed on 11 December 2025).

- Yayla, N. Road Engineering; Birsen Publishing House: Istanbul, Turkey, 2004; ISBN 975-511-287-1. [Google Scholar]

- Amiri, A.M.; Nadimi, N.; Khalifeh, V.; Shams, M. GIS-Based Crash Hotspot Identification: A Comparison among Mapping Clusters and Spatial Analysis Techniques. Int. J. Inj. Contr Saf. Promot. 2021, 28, 325–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamh, H.; Alyami, S.H.; Khattak, A.; Alyami, M.; Almujibah, H. Exploring Road Traffic Accidents Hotspots Using Clustering Algorithms and GIS-Based Spatial Analysis. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 60944–60954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira-Vanegas, C.M.; Velez, J.I.; Garcia-Llinas, G.A. Analytical Methods and Determinants of Frequency and Severity of Road Accidents: A 20-Year Systematic Literature Review. J. Adv. Transp. 2022, 2022, 7239464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; He, J.; Wang, H.; Ye, Y.; Yan, X.; Wang, C.; Zhang, X. A Systematic Review of the Application and Prospect of Road Accident Blackspots Identification Approaches. Transp. Lett. 2025, 17, 1114–1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, C.; Chang, N.; Dong, C.; Chang, N. Overview of the Identification of Traffic Accidentprone Locations Driven by Big Data. Digit. Transp. Saf. 2023, 2, 67–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, D.; Zhang, B.; Chen, Z.; Xu, X.; Du, B. Connecting Tradition with Modernity: Safety Literature Review. Digit. Transp. Saf. 2023, 2, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Q.; Huang, G.; Tang, X. GIS-Based Analysis of Spatial–Temporal Correlations of Urban Traffic Accidents. Eur. Transp. Res. Rev. 2021, 13, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsahfi, T. Spatial and Temporal Analysis of Road Traffic Accidents in Major Californian Cities Using a Geographic Information System. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf 2024, 13, 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iamtrakul, P.; Chayphong, S. GIS-Based Analysis of Spatio-Temporal Clustering of Road Traffic Accidents in Bangkok Metropolitan Region (BMR), Thailand from 2012 to 2021. Transp. Res. Interdiscip. Perspect. 2025, 31, 101489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krukowicz, T.; Firlag, K.; Chrobot, P. Spatiotemporal Analysis of Road Crashes with Animals in Poland. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benedek, J.; Ciobanu, S.M.; Man, T.C. Hotspots and Social Background of Urban Traffic Crashes: A Case Study in Cluj-Napoca (Romania). Accid. Anal. Prev. 2016, 87, 117–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aati, K.; Houda, M.; Alotaibi, S.; Khan, A.M.; Alselami, N.; Benjeddou, O. Analysis of Road Traffic Accidents in Dense Cities: Geotech Transport and ArcGIS. Transp. Eng. 2024, 16, 100256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, N.; Katiyar, S.K. Application of Geographical Information System (GIS) in Reducing Accident Blackspots and in Planning of a Safer Urban Road Network: A Review. Ecol. Inf. 2021, 66, 101436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahzad, M. Review of Road Accident Analysis Using GIS Technique. Int. J. Inj. Contr Saf. Promot. 2020, 27, 472–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doğru, E.; Aydın, F. Analyzing of the Traffic Accident by the Geographic Information Systems (GIS): Karabük Merkez District Example. International Geography Symposium on the 30th Anniversary of TUCAUM, Ankara, Turkey, 3–6 October 2018; pp. 3–6. [Google Scholar]

- Choudhary, A.; Mishra, V.; Garg, R.D.; Jain, S.S. Spatio–Temporal Analysis of Traffic Crash Hotspots- an Application of GIS-Based Technique in Road Safety. Appl. Geomat. 2025, 17, 129–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ugural, M.N.; Aghili, S.; Burgan, H.I. Adoption of Lean Construction and AI/IoT Technologies in Iran’s Public Construction Sector: A Mixed-Methods Approach Using Fuzzy Logic. Buildings 2024, 14, 3317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Regions | Number of Traffic Accidents | Cause of Accident |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 41 | Drivers’ error: Red light violation |

| 2 | 32 | Road geometry error: Inappropriate intersection curve |

| 3 | 128 | Road geometry error: Insufficient length of connecting road |

| 4 | 34 | Irregularities in the signal plan |

| 5 | 24 | Driver and road geometry error: Drivers making incorrect “U” turns and insufficient storage distance for left turns. |

| 6 | 54 | Pedestrian error: Pedestrians crossing the road uncontrolled |

| 7 | 57 | Road geometry error: Drivers do not have sufficient stopping-visibility distance due to bridge abutments |

| 8 | 59 | Drivers’ error: Red light violation |

| 9 | 72 | Road geometry error: Skidding of vehicles on a narrow radius horizontal curve when entering an underpass with a steep descent ramp |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the International Society for Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Yalcin, M.A.; Kofteci, S.; San, B.T.; Burgan, H.I. A GIS-Based Approach to Analyzing Traffic Accidents and Their Spatial and Temporal Distribution: A Case Study of the Antalya City Center. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2026, 15, 19. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijgi15010019

Yalcin MA, Kofteci S, San BT, Burgan HI. A GIS-Based Approach to Analyzing Traffic Accidents and Their Spatial and Temporal Distribution: A Case Study of the Antalya City Center. ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information. 2026; 15(1):19. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijgi15010019

Chicago/Turabian StyleYalcin, Mehmet Arikan, Sevil Kofteci, Bekir Taner San, and Halil Ibrahim Burgan. 2026. "A GIS-Based Approach to Analyzing Traffic Accidents and Their Spatial and Temporal Distribution: A Case Study of the Antalya City Center" ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information 15, no. 1: 19. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijgi15010019

APA StyleYalcin, M. A., Kofteci, S., San, B. T., & Burgan, H. I. (2026). A GIS-Based Approach to Analyzing Traffic Accidents and Their Spatial and Temporal Distribution: A Case Study of the Antalya City Center. ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information, 15(1), 19. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijgi15010019