Geospatial Impacts of Land Allotment at the Standing Rock Reservation, USA: Patterns of Gain and Loss

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Historical Overview

2.1. The Indian Problem and Land Allotment

“… the President of the United States … hereby is, authorized, whenever in his opinion any reservation or any part thereof of such Indians is advantageous for agricultural and grazing purposes, to cause said reservation, or any part thereof, to be surveyed, or resurveyed if necessary, and to allot the lands in said reservation in severalty to any Indian located thereon”.[20] (Section 1)

2.2. Allotment at Standing Rock

3. Goals and Research Questions

We view our findings here as setting the stage for further study into understanding the complex spatio-temporal patterns of land holding that took form at Standing Rock because of allotment. We envision that the next stage of research will combine our allotment databases with the powerful mapping and analytical capabilities of geographic information systems (GIS) to visualize and dynamically explore the impacts of allotment.[2] (p. 433)

3.1. Overall Patterns of Allotment

3.2. Tribal Patterns

3.3. Individual Patterns of Allotment

3.4. Family Patterns of Allotment

4. Methodology

4.1. Research Context

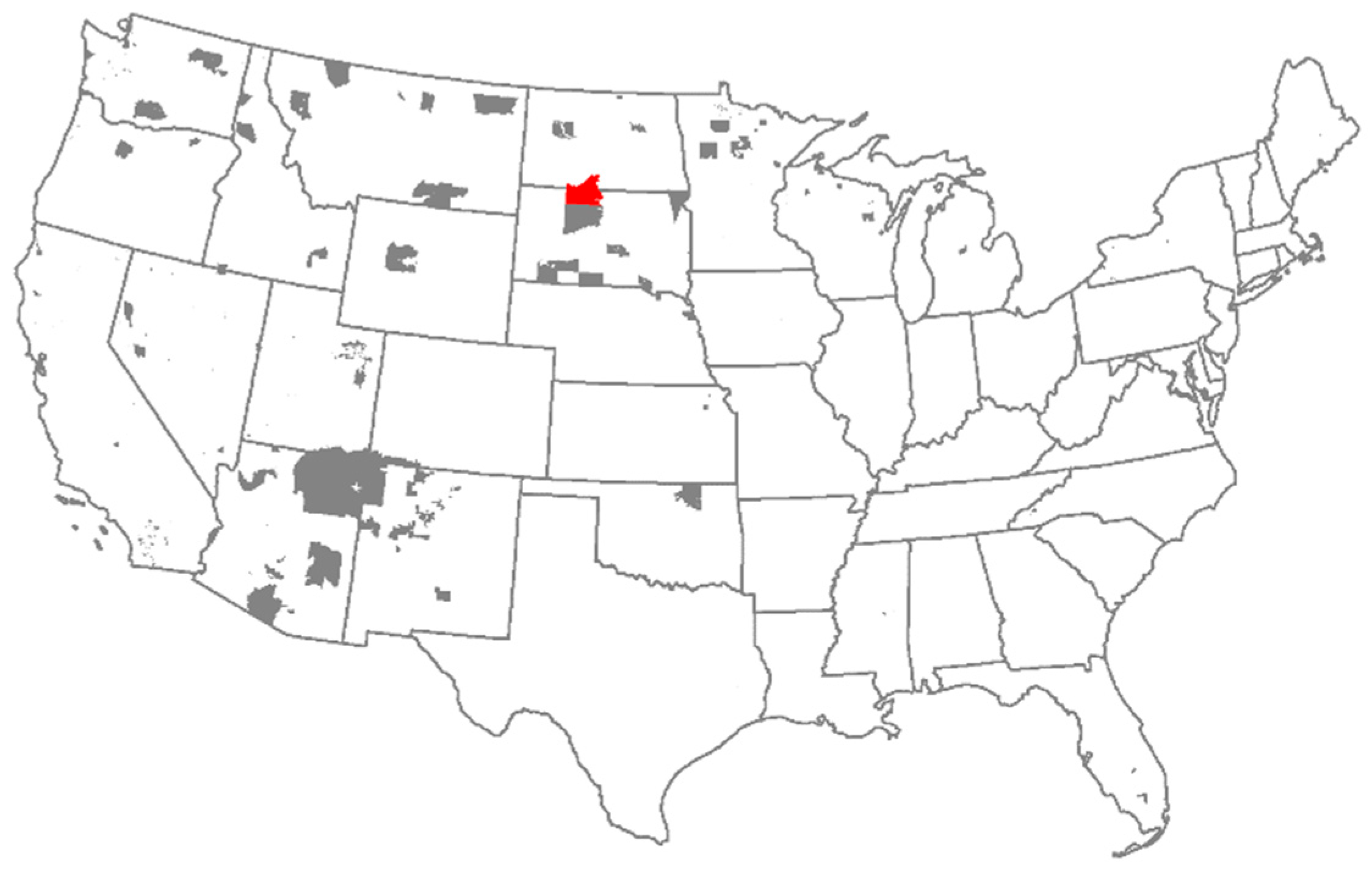

4.2. Study Area

4.3. Data and Methods

5. Results and Discussion

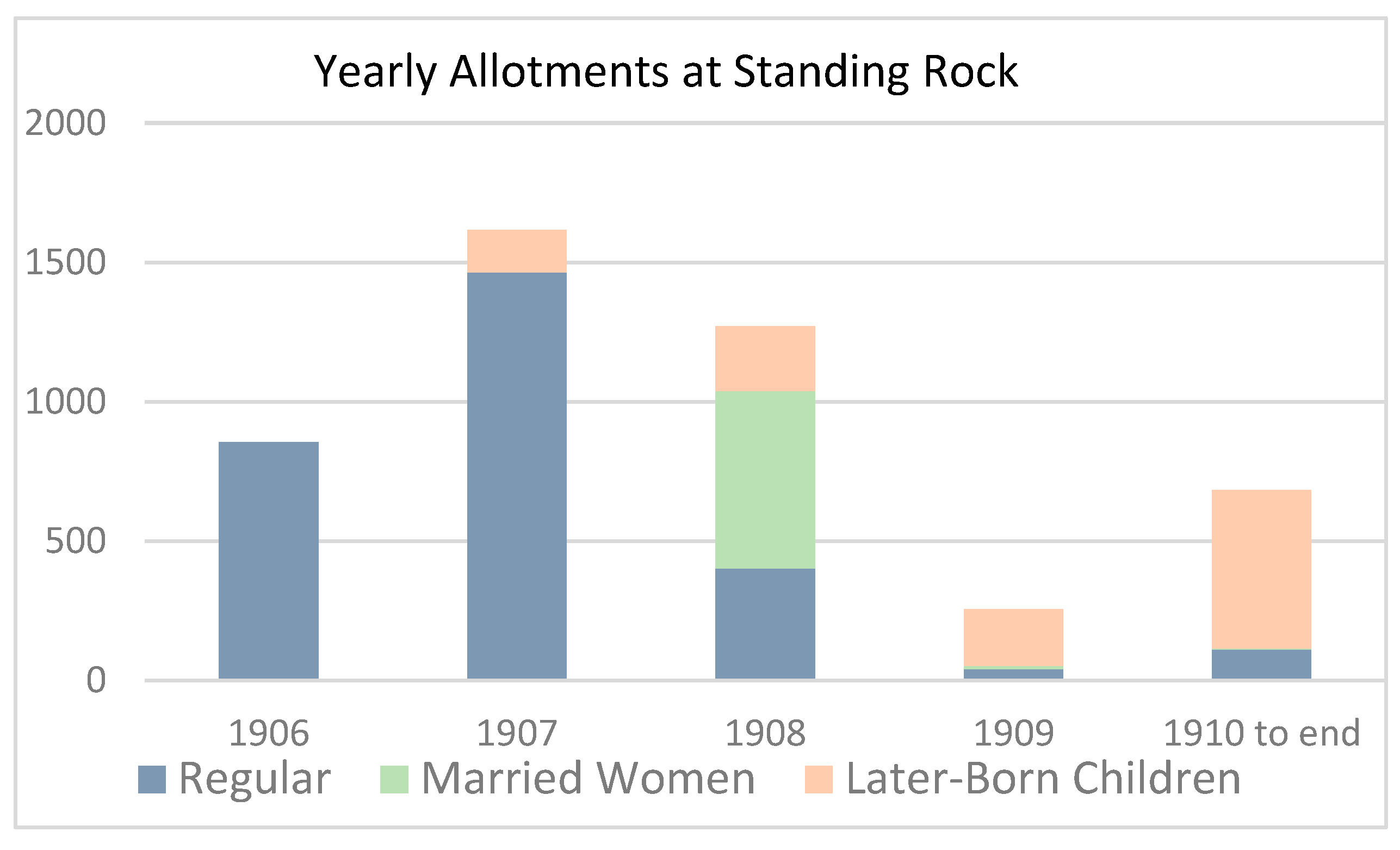

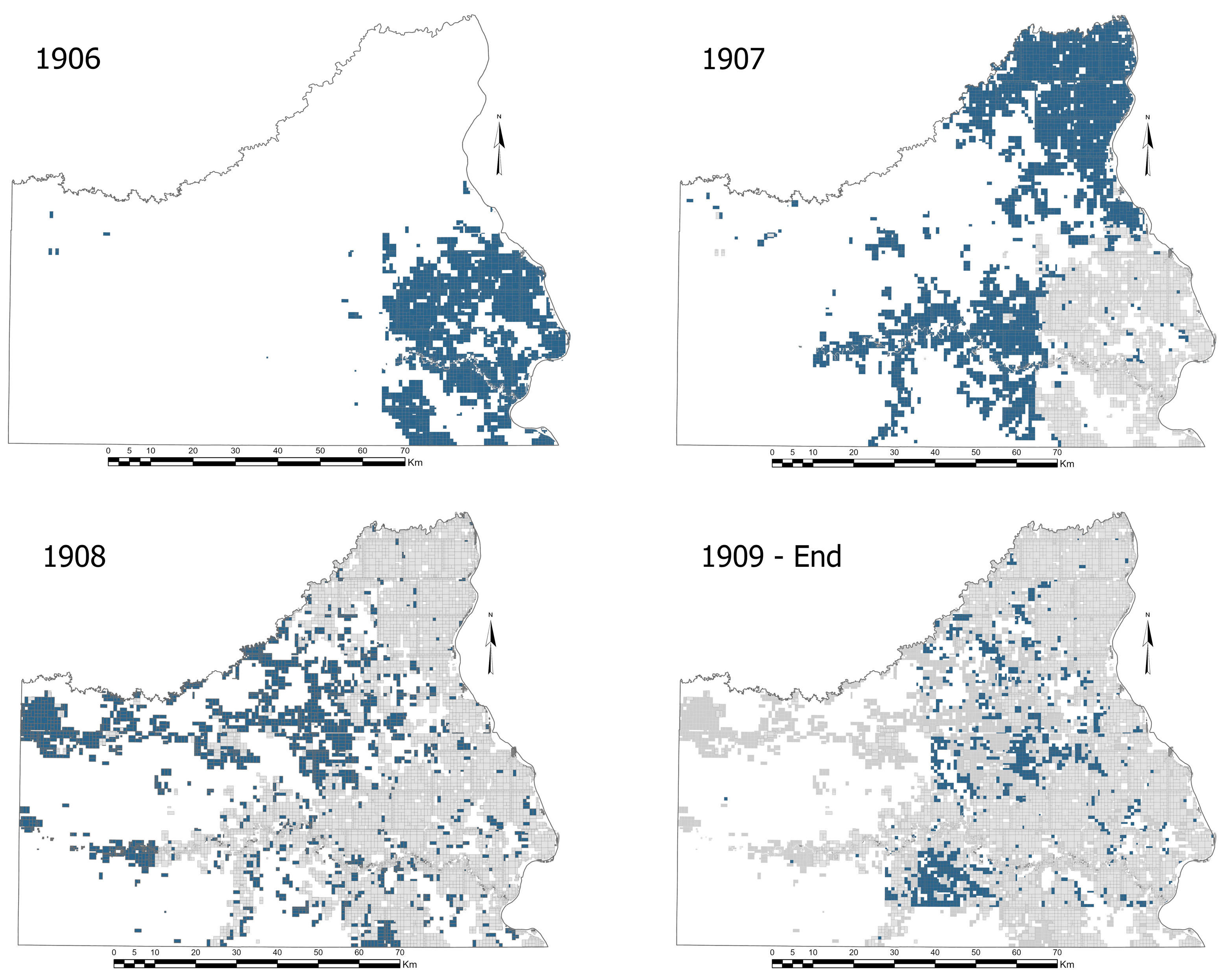

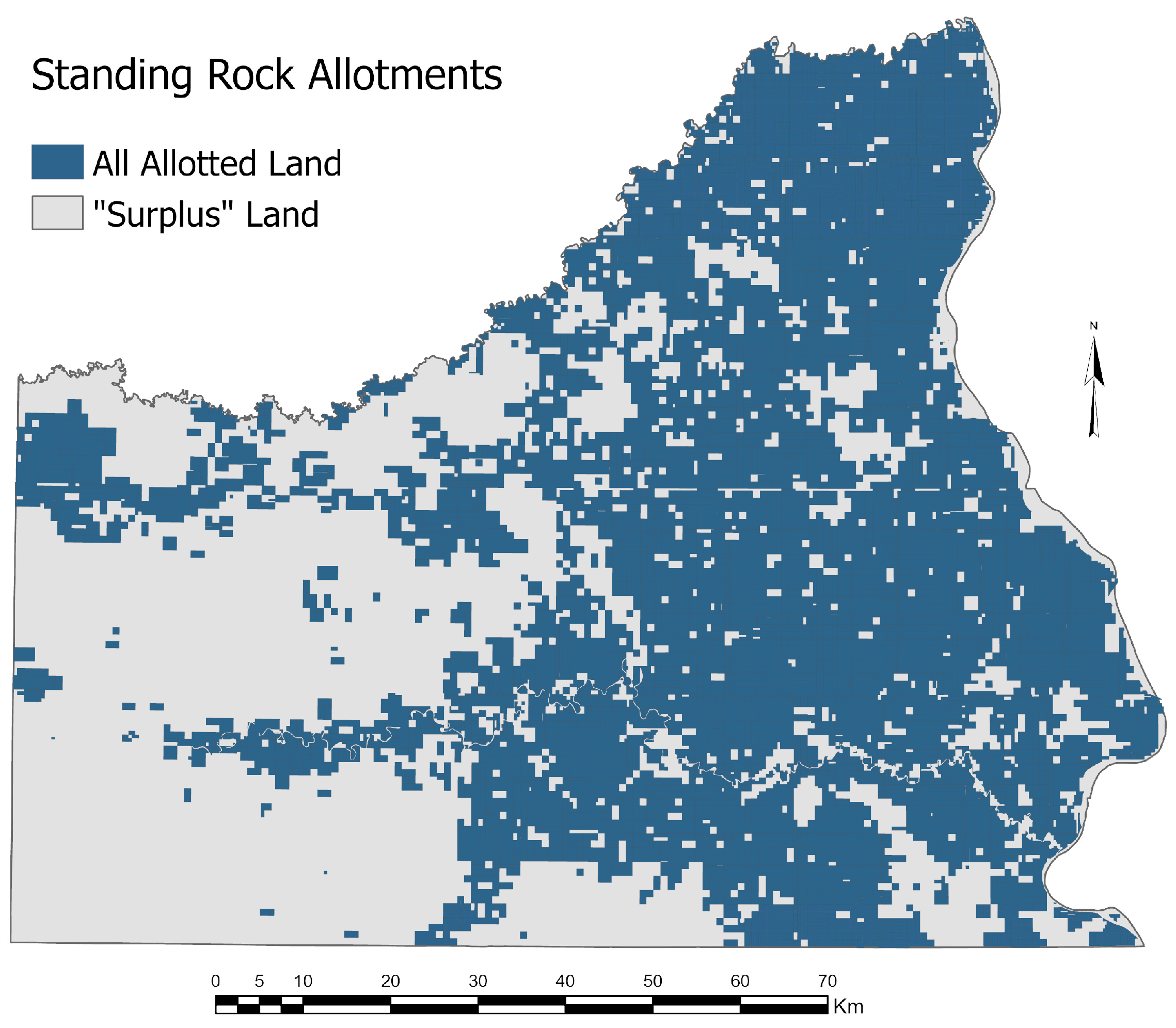

5.1. Overall Patterns of Allotment

5.2. Allotment Concentrations by Tribe

5.2.1. Clues from the Historical Record at Standing Rock

“[T]he Lower Yanktonai Indians have cultivated nearly 200 acres on the eastern side of the Missouri River, about 40 miles above the agency. The Blackfeet Sioux also cultivated one hundred acres of land near the Moreau River, about 25 miles south of the Agency. The Upper Yanktonai wish to farm at a spot fifty miles above the agency on the west side of the river”.[56]

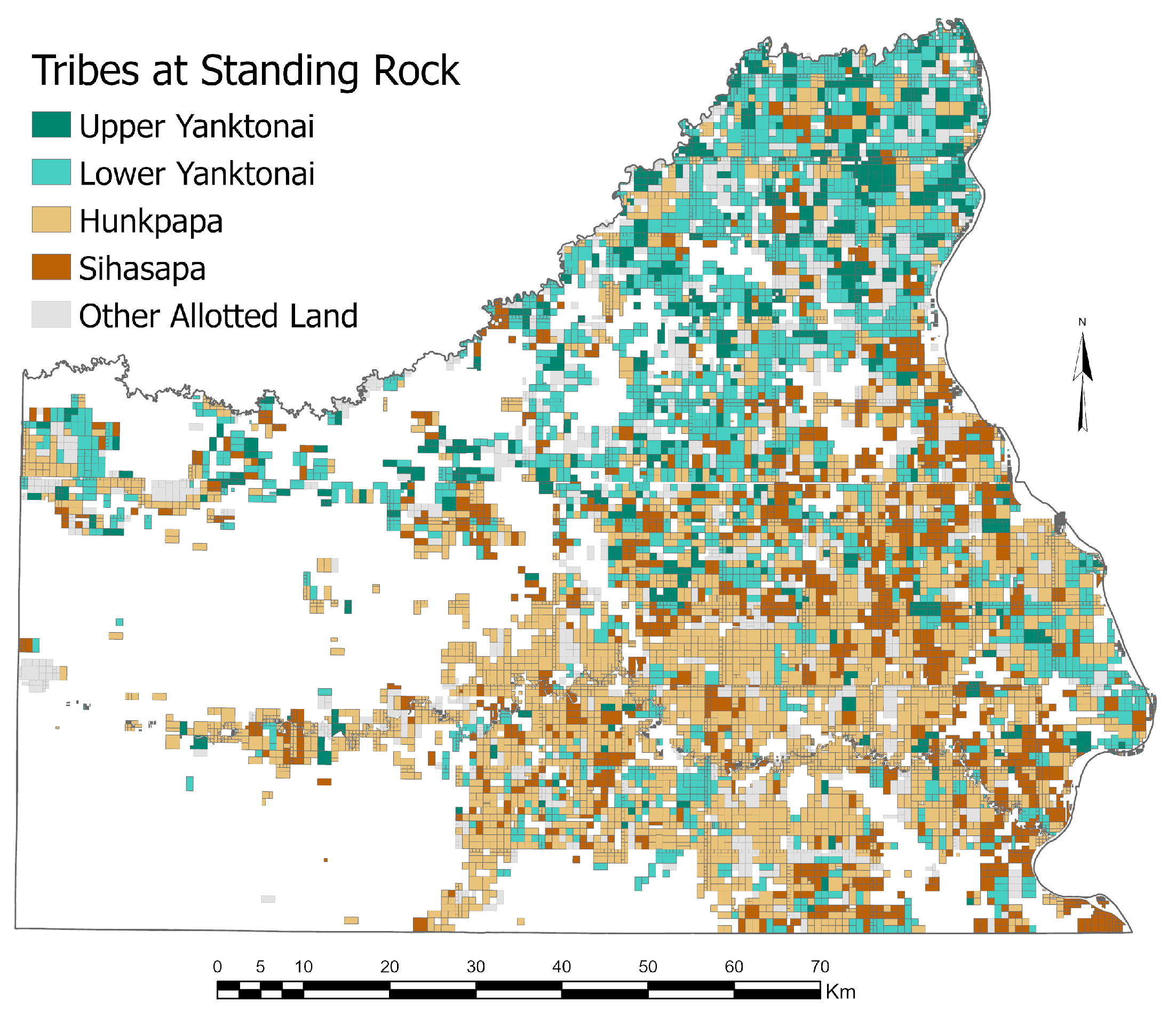

5.2.2. Mapped Patterns of Allotments by Tribe

5.3. Allotment Patterns of Individuals

5.3.1. Land Allotted to Individuals by Sex and Age

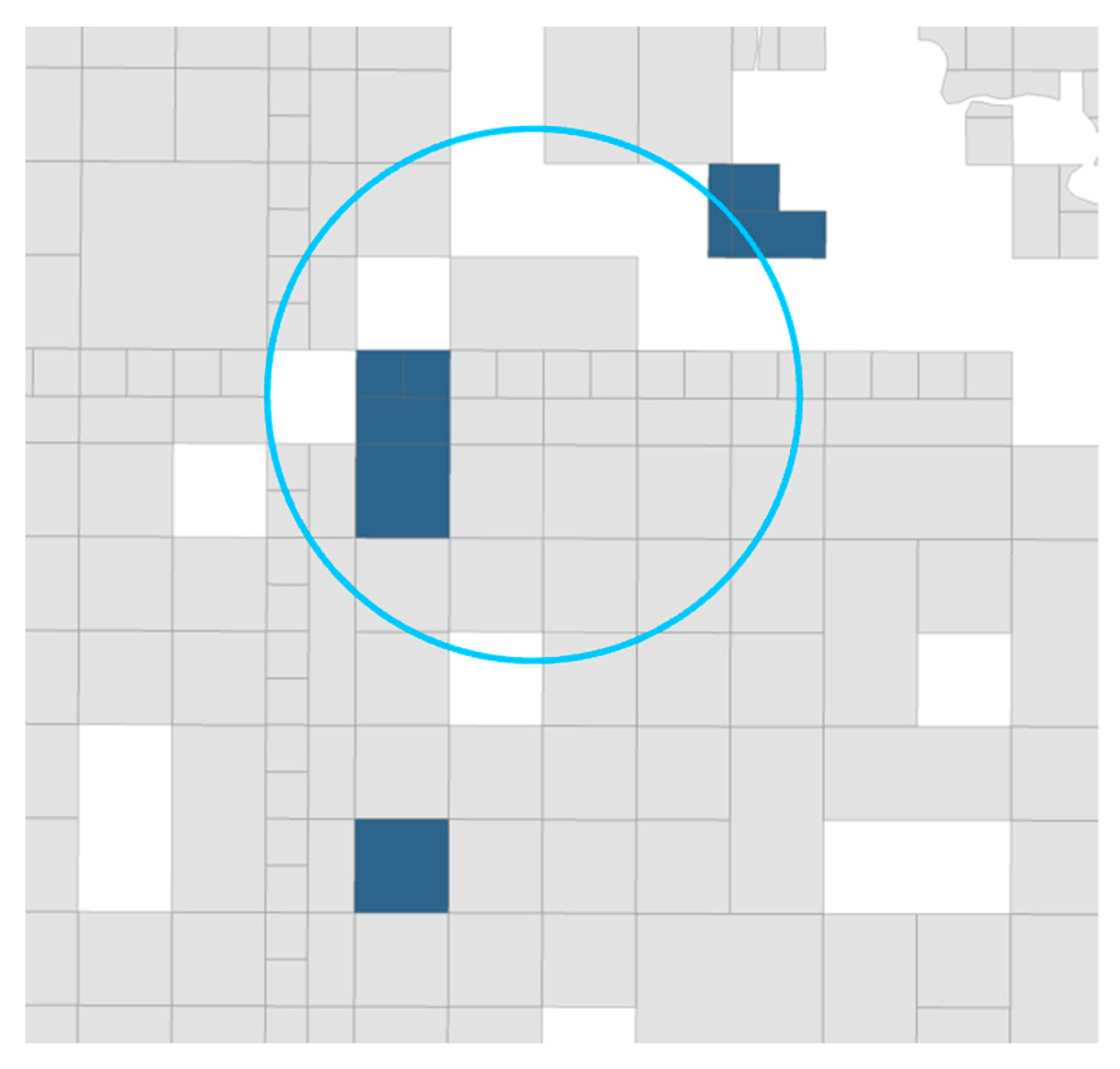

5.3.2. Number of Parcels per Allottee

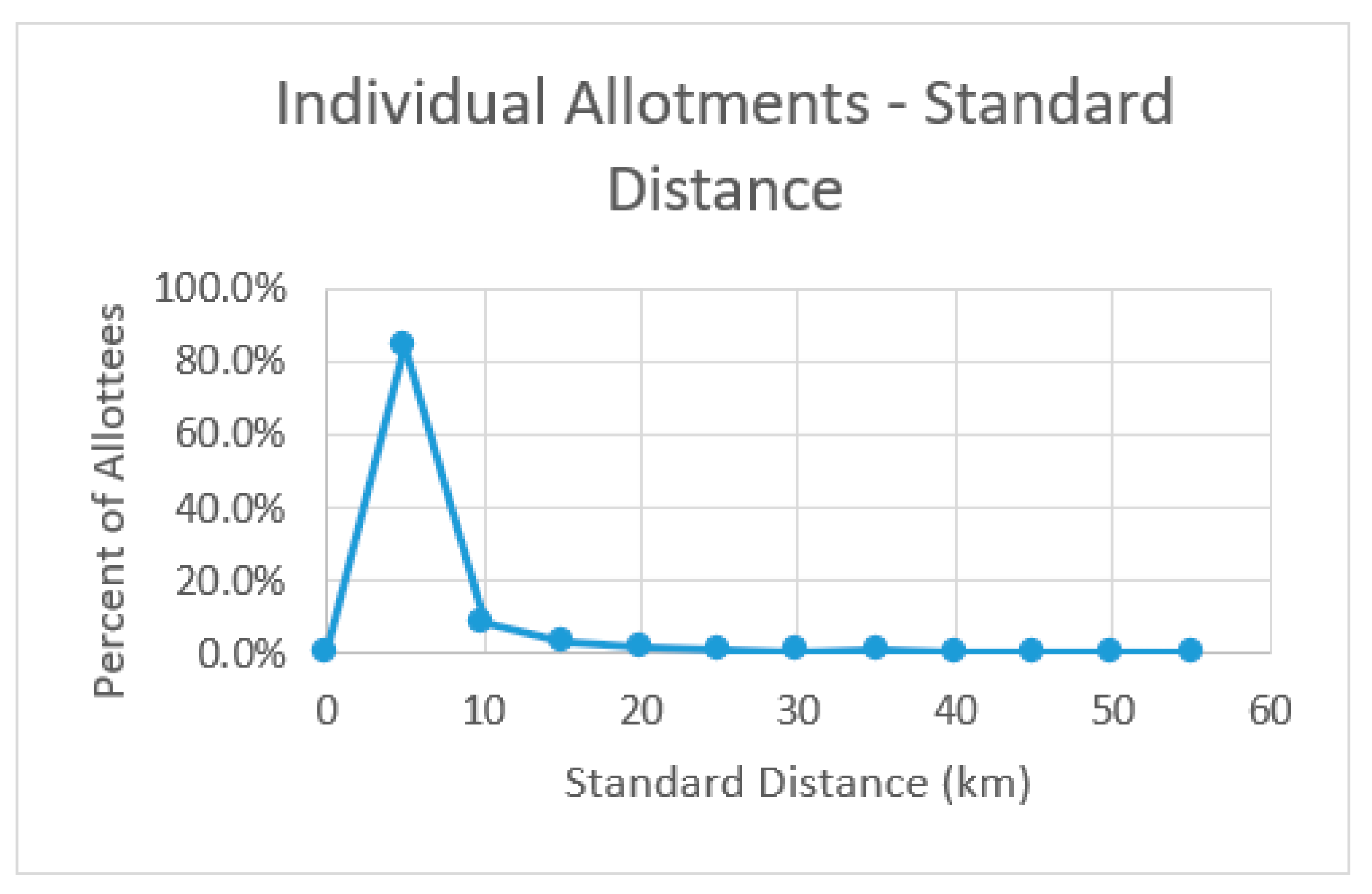

5.3.3. Patterns of Individual Allotments

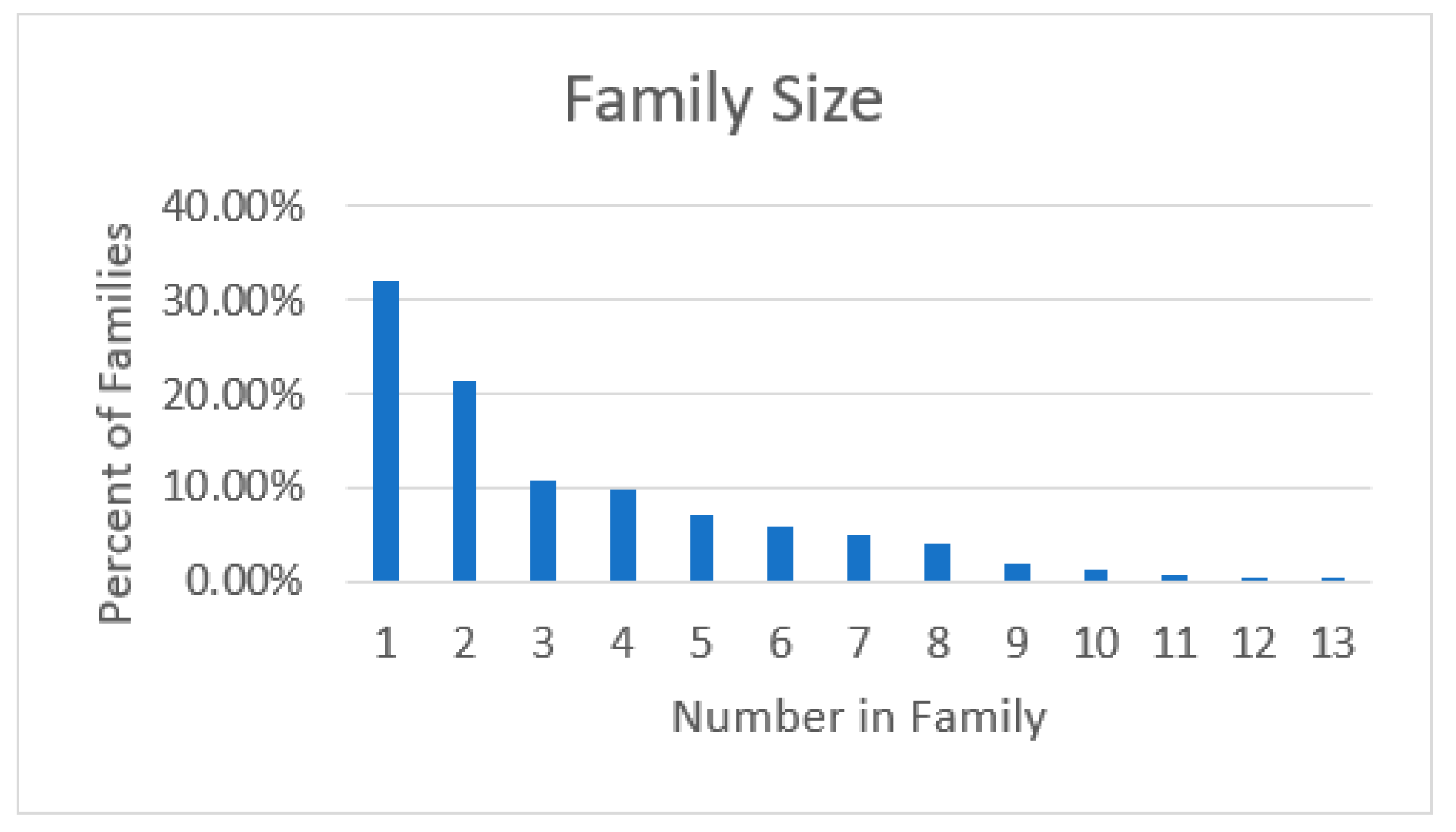

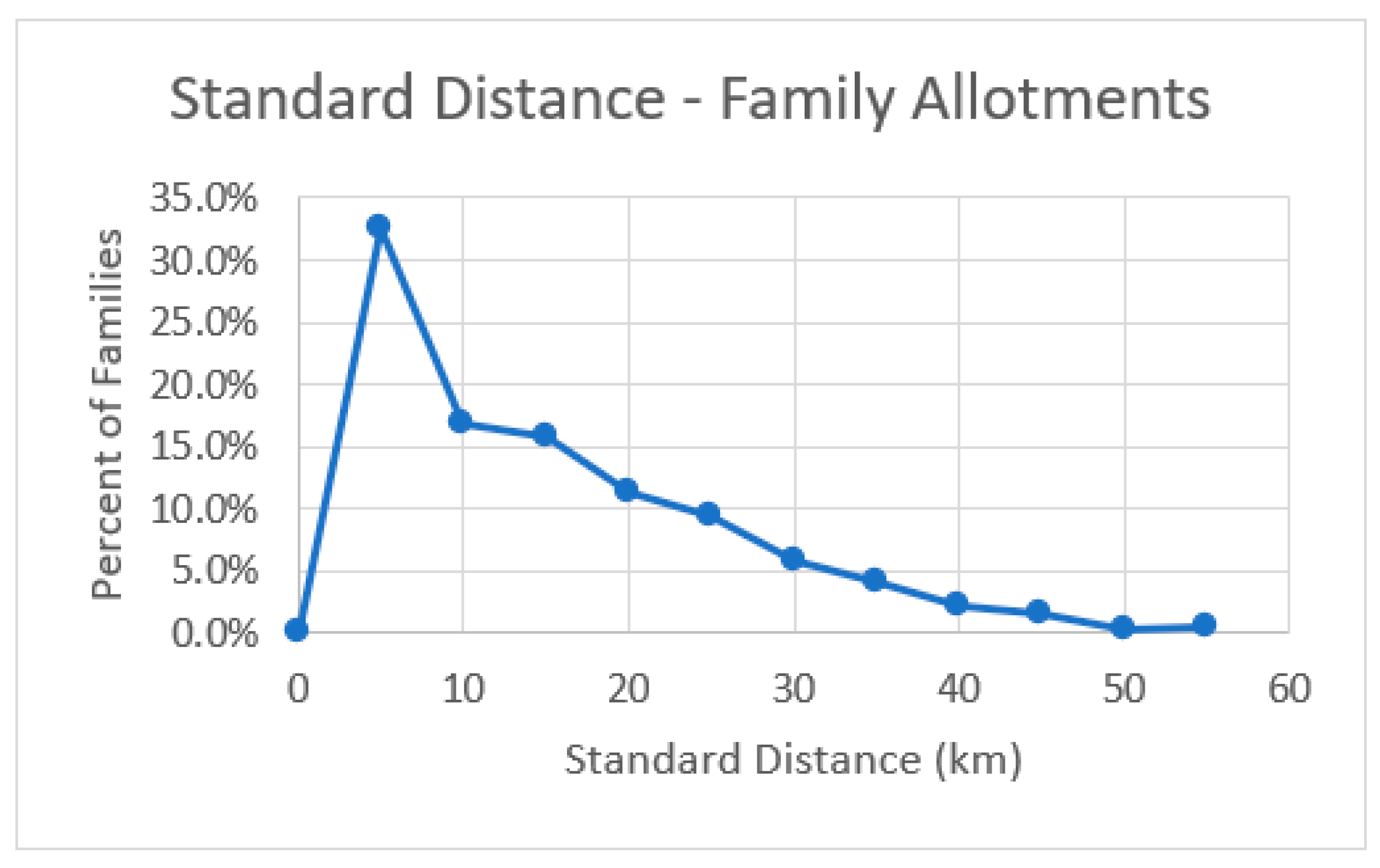

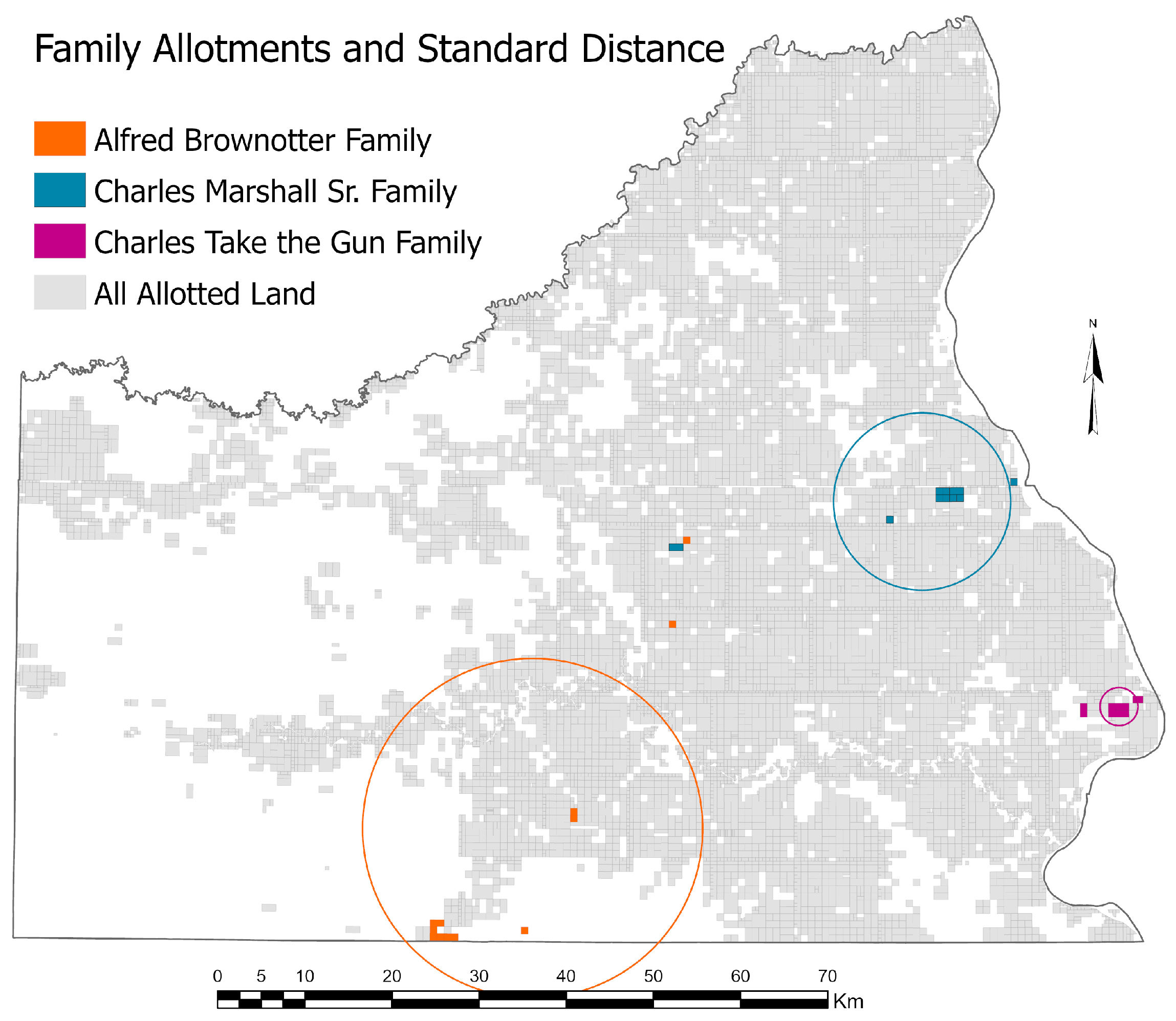

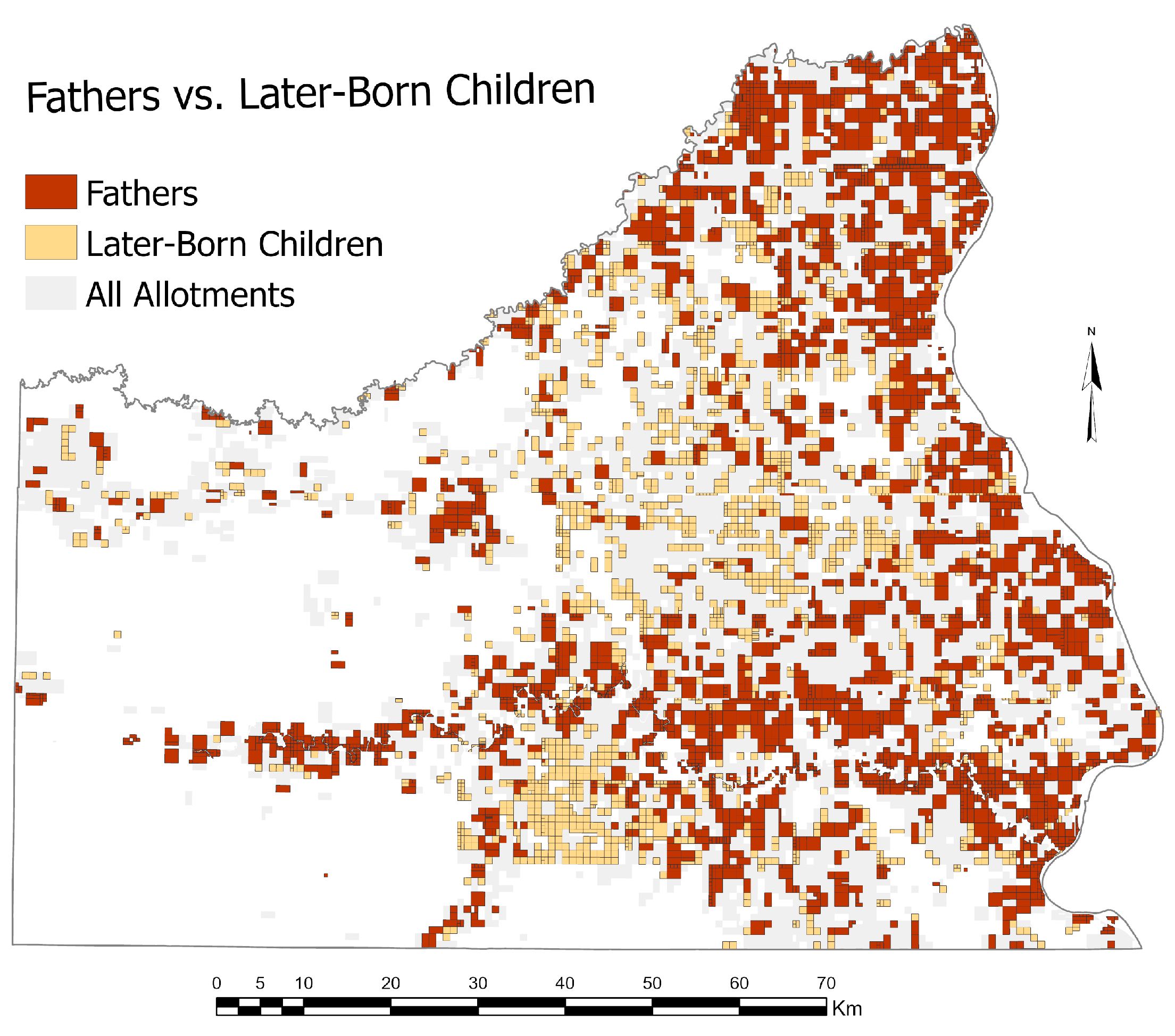

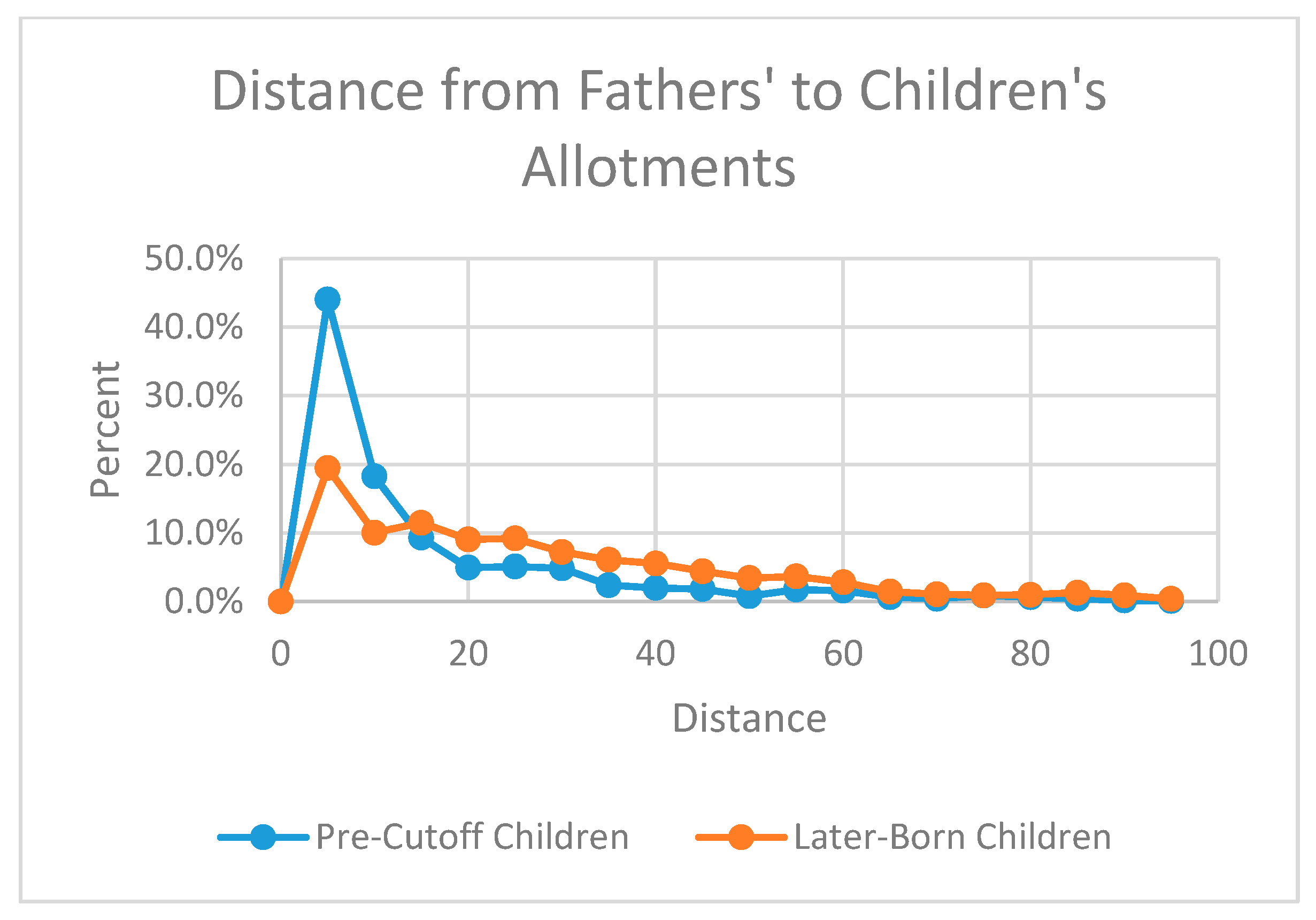

5.4. Family Patterns

5.4.1. Overall Family Patterns

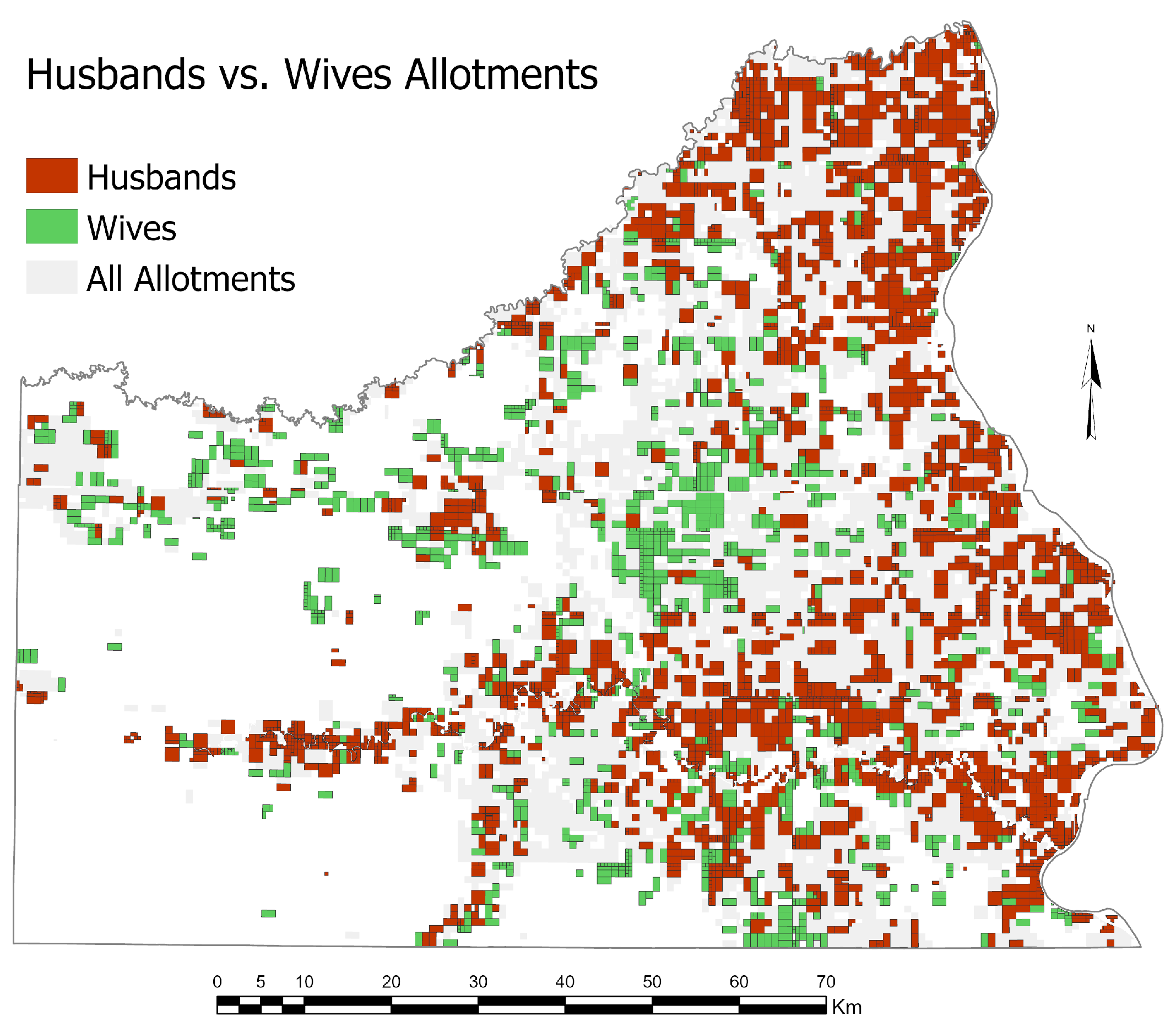

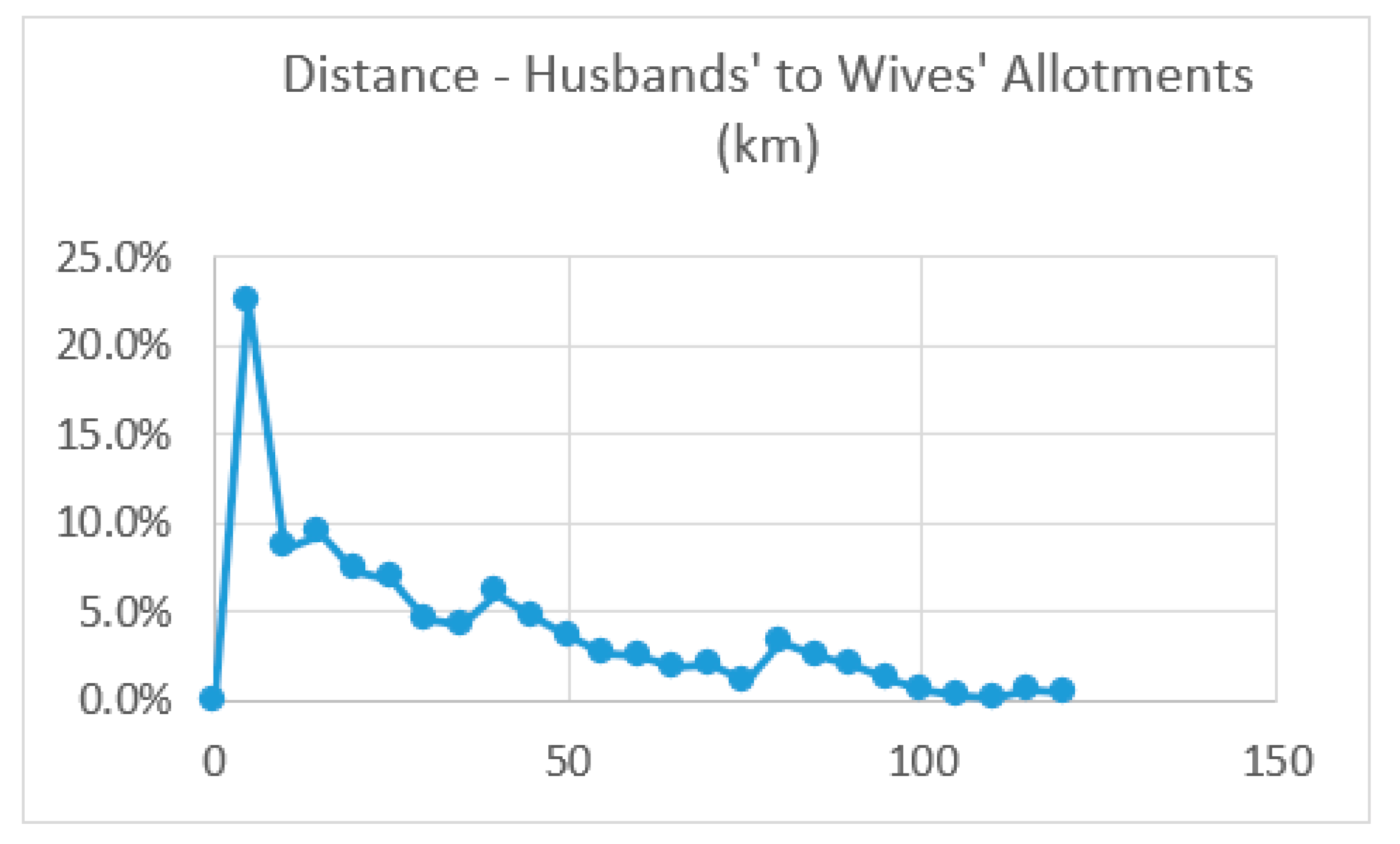

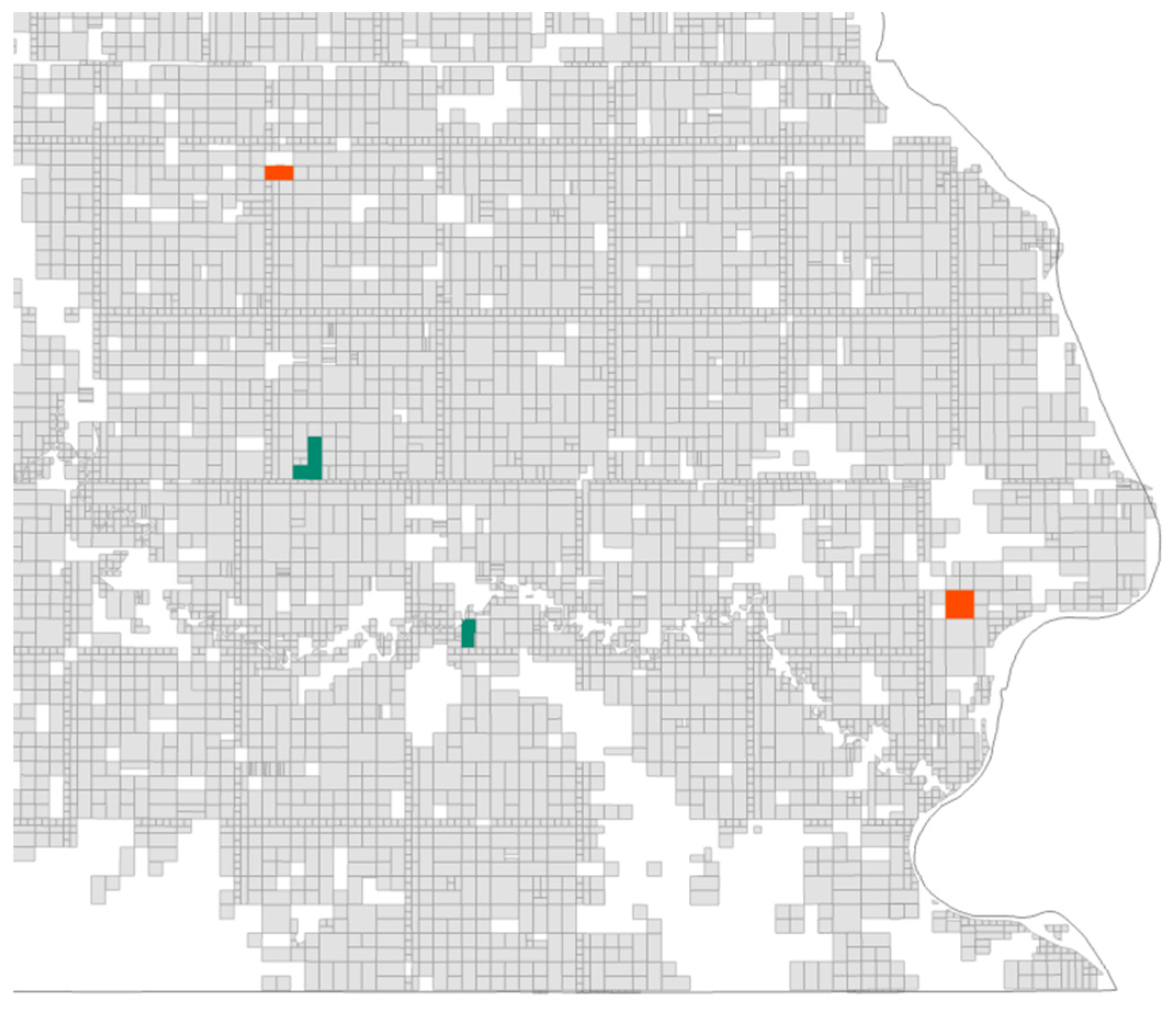

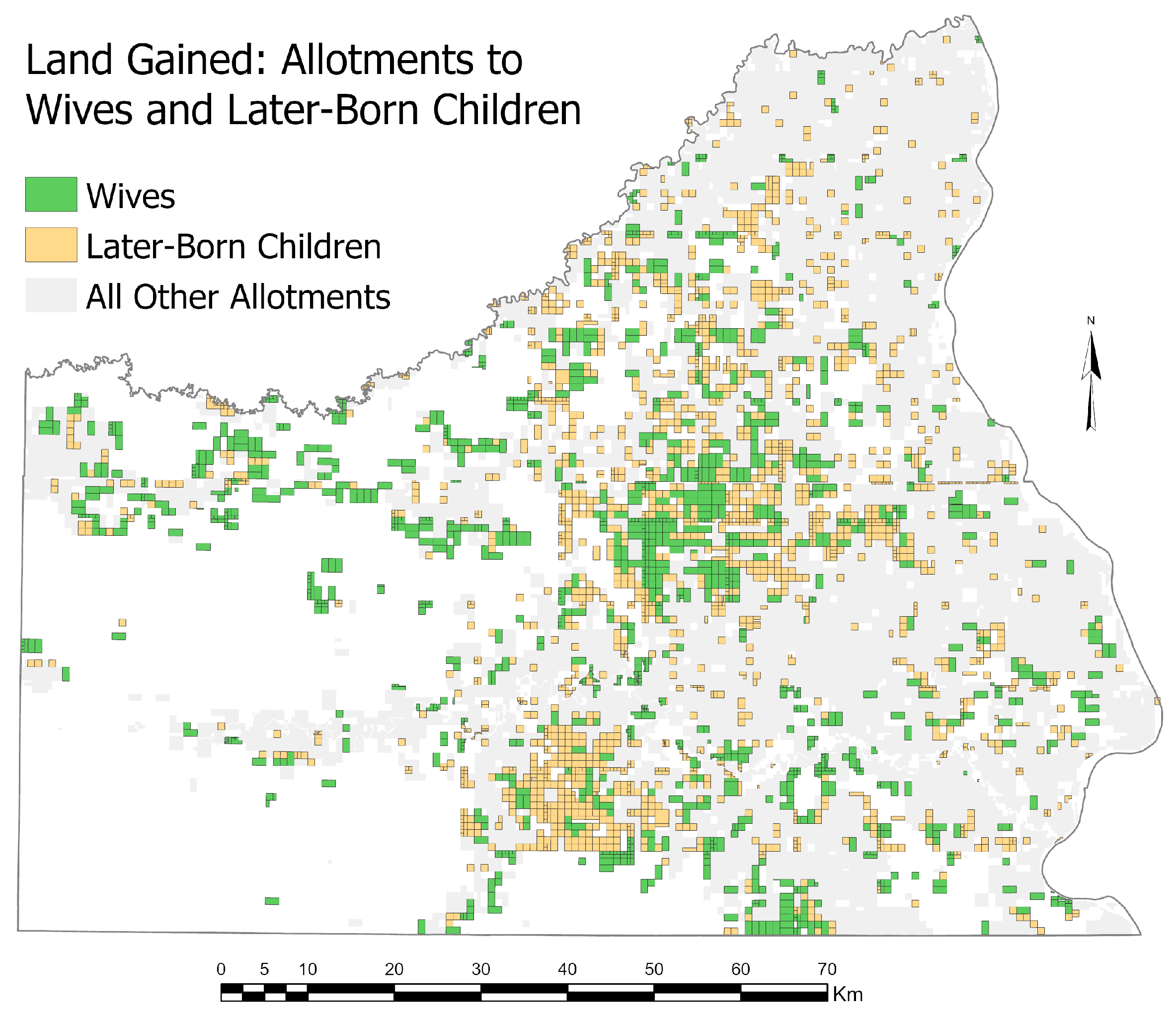

5.4.2. Allotments to Married Women

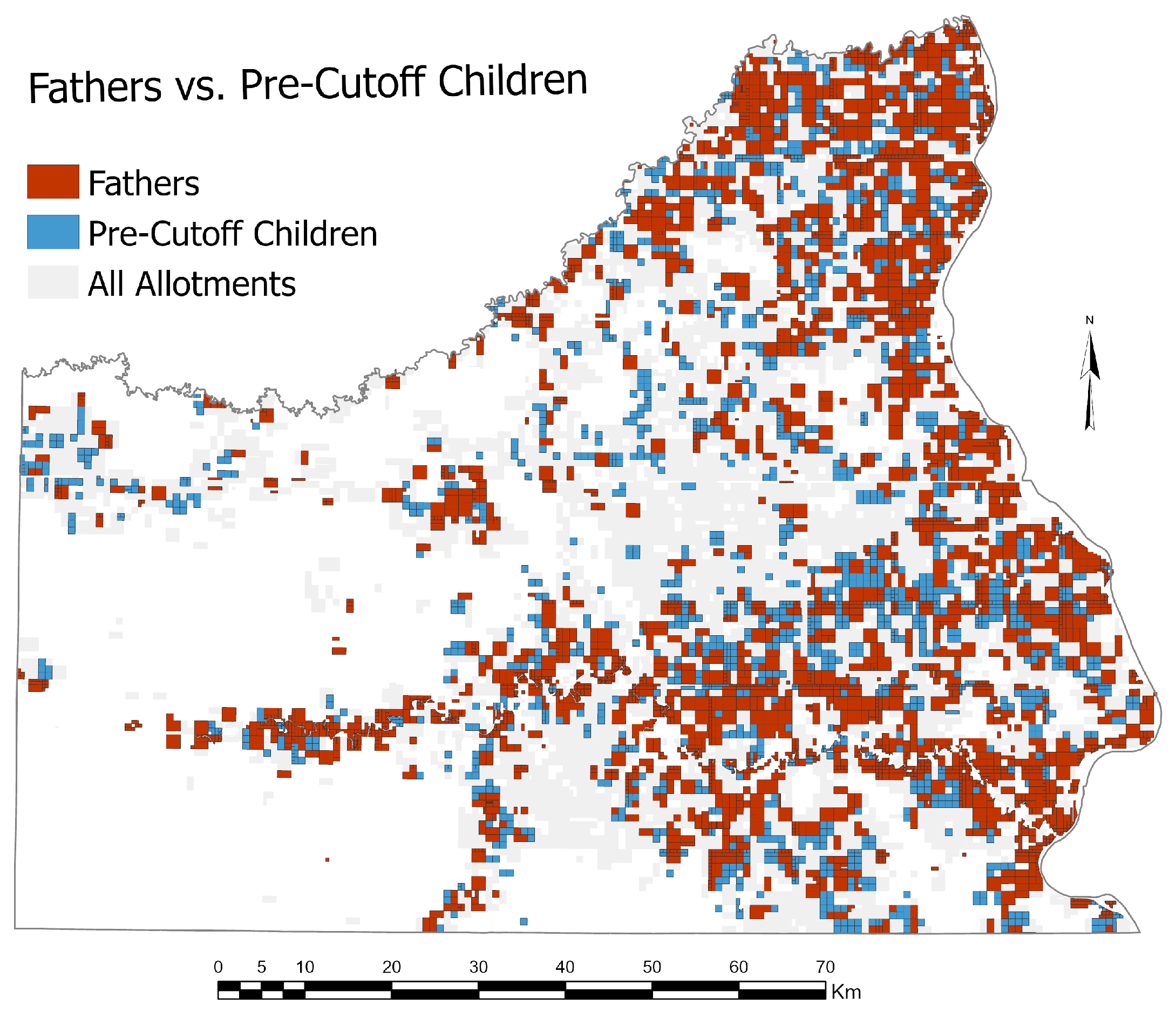

5.4.3. Allotments to Pre-Cutoff Children

5.4.4. Allotments to Later-Born Children

6. Conclusions and Future Research

6.1. Conclusions

- Overall allotment patterns. Our findings confirmed what we had earlier surmised in [2], namely that, where possible, people appear to have selected allotments on land they had already occupied for years and even decades. As expected, these lands favored proximity to rivers, streams, and timber resources and were therefore focused in the eastern portions of the reservation and along the rivers and streams that are more abundant in that part of the reservation. However, an important caveat is that, as we note above, “the overall pattern of allotments themselves was a reflection not only of the existing settlement patterns and preferences of the people but of the conditions and terms of allotment imposed by the U.S. government”.

- Tribal allotment patterns. As we had hypothesized, the allotment selections of members of the two major related tribal groups, the Lakota and Dakota, tended to be clustered in separate areas of the reservation, with the Dakota (Upper Yanktonai and Lower Yanktonai) in the north and the Lakota (Hunkpapa and Sihsapa) in the south, although there was a large degree of intermingling.

- Individual allotment patterns. We confirmed that individual patterns of allotments agreed with Gunderson’s claim that the majority of allottees were taking their allotments “in a compact body”, with nearly two-thirds of allottees (64.5%) selecting only a single parcel of land. Even when allottees were required by geographical or other circumstances to select multiple parcels, the parcels were almost always clustered together, either adjacent to each other or nearby.

- Family patterns of allotment. We confirmed that total allotments to families were swelled substantially by allotments to married women and later-born children due to legislation passed by Congress in 1907 at the insistence of the people at Standing Rock and with the support of the Special Allotting Agent and the Office of Indian Affairs. In all, nearly 400,000 acres (approx. 160,000 ha) of land were allotted to individuals who otherwise would have been landless (Figure 21).

6.2. Unanswered Questions–Future Research Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

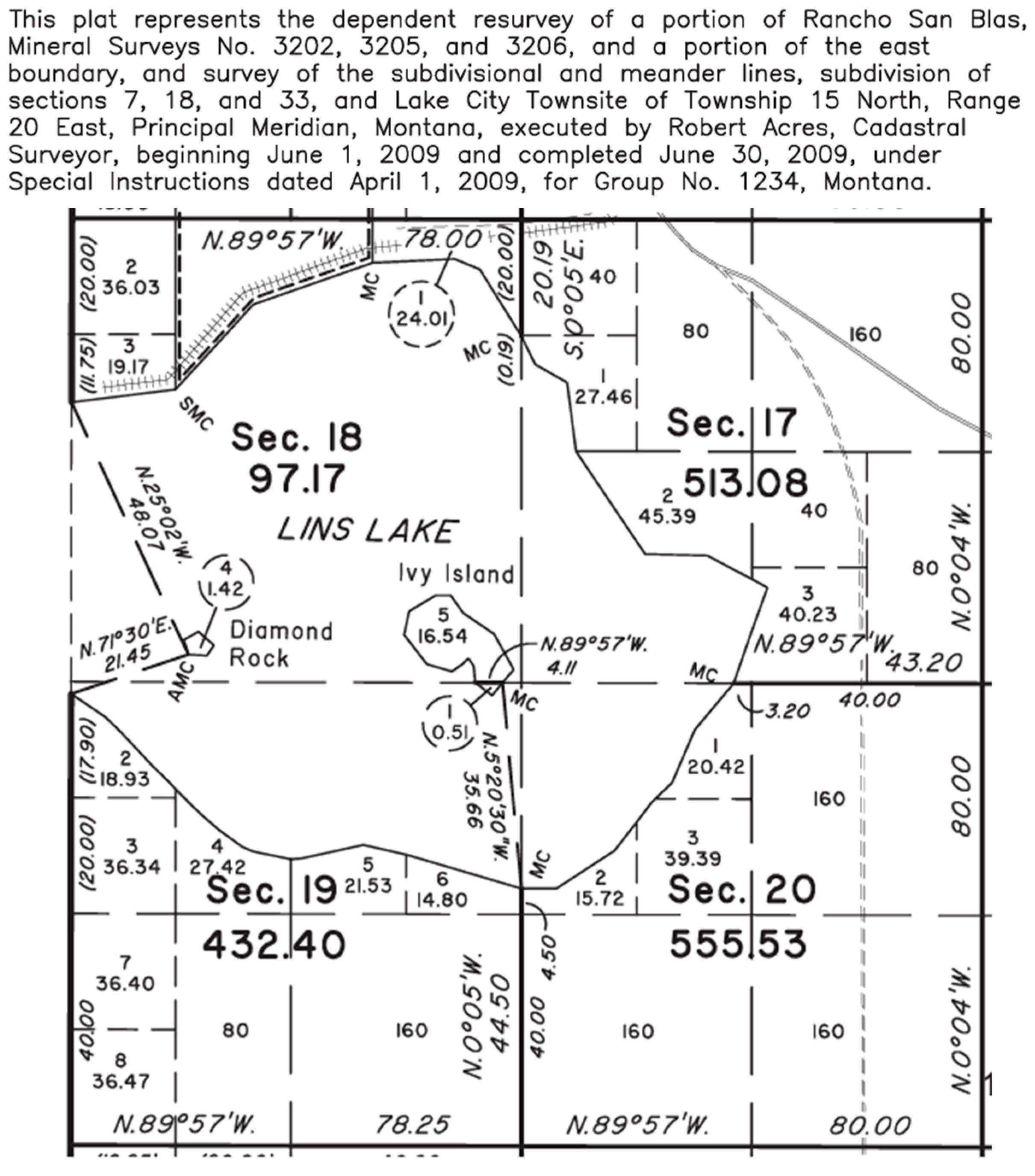

Appendix A. Example Map of Government Lots

Appendix B. Regular Allotments to Females and Males, by Age and Relationship Category

| Female | Child < 18 | Adult ≥ 18 | ||||

| Relationship Category | Number Allottees | Total Acres | Mean Acres | Number Allottees | Total Acres | Mean Acres |

| Wife | 4 | 839 | 210 | 655 | 210,177 | 321 |

| Mother | 1 | 320 | 320 | 26 | 10,064 | 387 |

| Divorced | 0 | 0 | --- | 1 | 320 | 320 |

| Widow | 3 | 950 | 317 | 213 | 80,583 | 378 |

| Second Wife | 0 | 0 | --- | 6 | 2212 | 369 |

| Wife of White Man | 0 | 0 | --- | 2 | 1281 | 640 |

| Head (F) | 4 | 2093 | 523 | 33 | 19,219 | 582 |

| Present Wife | 1 | 160 | 160 | 0 | 0 | --- |

| Grandmother | 0 | 0 | --- | 2 | 641 | 321 |

| Aunt | 0 | 0 | --- | 3 | 962 | 321 |

| Sister | 9 | 2231 | 248 | 6 | 2241 | 373 |

| Daughter | 1224 | 197,337 | 161 | 82 | 26,040 | 318 |

| Stepdaughter | 31 | 4950 | 160 | 3 | 961 | 320 |

| Granddaughter | 13 | 3515 | 270 | 0 | 0 | --- |

| Single (F) | 9 | 1922 | 214 | 62 | 20,460 | 330 |

| Orphan (F) | 7 | 1760 | 251 | 1 | 320 | 320 |

| Adopted (Daughter) | 3 | 955 | 318 | 0 | 0 | --- |

| Mother-in-law | 0 | 0 | --- | 3 | 960 | 320 |

| Niece | 3 | 480 | 160 | 0 | 480 | --- |

| Total Female | 1312 | 217,513 | 166 | 1098 | 376,921 | 343 |

| Male | Child < 18 | Adult ≥ 18 | ||||

| Relationship Category | Number Allottees | Total Acres | Mean Acres | Number Allottees | Total Acres | Mean Acres |

| Husband | 3 | 1279 | 426 | 649 | 389,086 | 600 |

| Father | 1 | 651 | 651 | 14 | 7795 | 557 |

| Widower | 0 | 0 | --- | 29 | 13,710 | 473 |

| Head (M) | 0 | 0 | --- | 72 | 40,057 | 556 |

| Brother | 7 | 1601 | 229 | 7 | 2237 | 320 |

| Nephew | 2 | 320 | 160 | 1 | 320 | 320 |

| Son | 1158 | 190,755 | 165 | 129 | 41,327 | 320 |

| Stepson | 29 | 4850 | 167 | 11 | 3542 | 322 |

| Grandson | 8 | 1762 | 220 | 2 | 639 | 319 |

| Adopted | 1 | 169 | 169 | 0 | 0 | --- |

| Single (M) | 12 | 2231 | 186 | 113 | 36,368 | 322 |

| Orphan (M) | 9 | 2738 | 304 | 0 | 0 | --- |

| Total Male | 1230 | 206,357 | 168 | 1027 | 535,081 | 521 |

References

- Meisel, J.J.; Egbert, S.L.; Brewer, J.P., II; Li, X. Automated Mapping of Historical Native American Land Allotments at the Standing Rock Sioux Reservation Using Geographic Information Systems. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2021, 10, 183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egbert, S.L.; Meisel, J.J. “The Indians Complain, and with Good Cause”: Allotting Standing Rock—U.S. Policy Meets a Tribe’s Assertion of Rights. Geographies 2024, 4, 411–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banner, S. How the Indians Lost Their Land: Law and Power on the Frontier, 1st ed.; The Belknap Press of the Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2005; ISBN 067402396X. [Google Scholar]

- Fritz, H.E. The Movement for Indian Assimilation: 1860–1890; University of Pennsylvania Press: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1963. [Google Scholar]

- Genetin-Pilawa, C.J. Crooked Paths to Allotment: The Fight over Federal Indian Policy After the Civil War; The University of North Carolina Press: Chapel Hill, NC, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Hoxie, F.E. A Final Promise: The Campaign to Assimilate the Indians, 1880–1920; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- McDonnell, J.A. The Dispossession of the American Indian, 1887–1934; Indiana University Press: Bloomington, IN, USA, 1991; ISBN 0253336287. [Google Scholar]

- Otis, D.S. The Dawes Act and the Allotment of Indian Lands, 1st ed.; University of Oklahoma Press: Norman, OK, USA, 1973; ISBN 0806110392. [Google Scholar]

- Sutton, I. Cartographic Review of Indian Land Tenure and Territoriality: A Schematic Approach. Am. Indian Cult. Res. J. 2002, 26, 63–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Washburn, W.E. The Assault on Indian Tribalism: The General Allotment Law (Dawes Act) of 1887; Hyman, H.M., Ed.; J.B. Lippincott: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Debo, A. And Still the Waters Run; Reprint Edition; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Gates, P.W. Fifty Million Acres: Conflicts over Kansas Land Policy, 1854–1890; Cornell University Press: Ithaca, NY, USA, 1954. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, M.L. The White Earth Tragedy: Ethnicity and Dispossession at a Minnesota Anishinaabe Reservation, 1889–1920; University of Nebraska Press: Lincoln, NE, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Paulson, H.W. The Allotment of Land in Severalty to the Dakota Indians before the Dawes Act. South Dak. Hist. 1971, 1, 132–153. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, C. Making Native Space: Colonialism, Resistance, and Reserves in British Columbia; UBC Press: Vancouver, BC, Canada, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Herlihy, P.H.; Knapp, G. Maps of, by, and for the peoples of Latin America. Hum. Organ. 2003, 62, 303–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chernela, J. Lex Talionis: Recent Advances and Retreats in Indigenous Rights in Brazil. J. Lat. Am. Anthropol. 2006, 11, 138–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brennan, S. Terra nullius, aboriginal sovereignty and land rights in Australia. Political Geogr. 1993, 12, 319–346. [Google Scholar]

- Byrnes, G. Boundary Markers: Land Surveying and the Colonisation of New Zealand; Bridget Williams Books: Wellington, New Zealand, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Congress. U.S. Statutes at Large, Volume 24—1887, 49th Congress. United States—1887. An Act to Provide for the Allotment of Lands in Severalty to Indians—On the Various Reservations, and to Extend the Protection of the Laws of the United States and the Territories over the Indians, and for Other Purposes. Retrieved from the Library of Congress. 1887. Available online: https://www.loc.gov/item/llsl-v24/ (accessed on 14 July 2025).

- U.S. Congress. U.S. Statutes at Large, Volume 12—1861, 36th and 37th Congress. United States—1861. Chap. 75. An Act to Secure Homesteads to Actual Settlers on the Public Domain. Retrieved from the Library of Congress. Available online: https://www.loc.gov/item/llsl-v12/ (accessed on 14 July 2025).

- U.S. Congress. U.S. Statutes at Large, Volume 41–1921, 66th Congress. United States, 1919–1921. Chap 224, Section 6. An Act To Provide for the Allotment of Lands of the Crow Tribe, for the Distribution of Tribal Funds, and for Other Purposes. Retrieved from the Library of Congress. Available online: https://www.loc.gov/item/llsl-v41/ (accessed on 14 July 2025).

- U.S. Congress. U.S. Statutes at Large, Volume 34—1907, 59th Congress. United States—1907. Chap. 2285. An Act Making Appropriations for the Current and Contingent Expenses of the Indian Department, for Fulfilling Treaty Stipulations with Various Indian Tribes, and for Other Purposes, for the Fiscal Year Ending June Thirtieth, Nineteen Hundred and Eight. Retrieved from the Library of Congress. 1907. Available online: https://www.loc.gov/item/llsl-v34/ (accessed on 14 July 2025).

- United States v. Powers, 305 U.S. 527, 1939. Retrieved from: JUSTIA: U.S. Supreme Court. Available online: https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/305/527/ (accessed on 14 July 2025).

- Sherman, W.T.; Harney, W.S.; Terry, A.H.; Augur, C.C.; Henderson, J.B.; Taylor, N.G.; Sanborn, J.B.; Tappan, S.F. Treaty with the Sioux–Brule, Oglala, Miniconjou, Yanktonai, Hunkpapa, Blackfeet, Cuthead, Two Kettle, San Arcs, and Santee and Arapaho [Fort Laramie Treaty], 29 April 1868; Record on File at National Archives and Records Administration; General Records of the United States Government, Record Group: Washington, DC, USA; Indian Treaties: Washington, DC, USA, 1868; pp. 1722–1869.

- U.S. Congress. U.S. Statutes at Large, Volume 25—1889, 50th Congress. United States—1889. [Periodical] Chap 405. An Act to Divide a Portion of the Reservation of the Sioux Nation of Indians in Dakota into Separate Reservations and to Secure the Relinquishment of the Indian Title to the Remainder, and for Other Purposes. March 2, 1889, pp. 888–899. Retrieved from the Library of Congress. 1889. Available online: https://www.loc.gov/item/llsl-v25/ (accessed on 14 July 2025).

- Standing Rock Agency. Copies of Correspondence Received, 1869–1910. Record on File at National Archives and Records Administration, Kansas City Branch (NARA-KC) USA, ARC ID: 1986649, Record Group 75, Boxes 23–68; Department of the Interior, Office of Indian Affairs: Washington, DC, USA, 1986.

- Stretton, T.; Kesselring, K.J. Introduction: Coverture and Continuity. In Married Women and the Law: Coverture in England and the Common Law World; Stretton, T., Kesselring, K.J., Eds.; Montreal and Kingston: Kingston, ON, Canada, 2013; p. 3. [Google Scholar]

- Ireland, E. Re-examining the Presumption: Coverture and ‘Legal Impossibilities’ in Early Modern English Criminal Law. J. Leg. Hist. 2022, 43, 187–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Congress. U.S. Statutes at Large, Volume 35—1909, 60th Congress. United States—1909. [Periodical] Chap. 218. An Act to Authorize the Sale and Disposition of a Portion of the Surplus and Unallotted Lands in the Cheyenne River and Standing Rock Indian Reservations in the States of South Dakota and North Dakota, and Making Appropriation and Provision to Carry the Same into Effect. Retrieved from the Library of Congress. 1908. Available online: https://www.loc.gov/item/llsl-v35/ (accessed on 14 July 2025).

- Sun Eagle, C. Spatial and Temporal Patterns of Land Allotment on the Pawnee Reservation. Master’s Thesis, University of Kansas, Lawrence, KS, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Moore, J.H. Aboriginal Indian Residence Patterns Preserved in Censuses and Allotments. Science 1980, 207, 201–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moore, J.H. The Cheyenne Nation: A Social and Demographic History; University of Nebraska Press: Lincoln, NE, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Standing Rock Agency. Copies of Correspondence Sent by the Special Allotting Agent, 1906–1910; [Gunderson Letters]; Department of the Interior, Office of Indian Affairs, Record on File at National Archives and Records Administration, Kansas City Branch (NARA-KC) USA, ARC ID: 5634369, Record Group 75, Box 735; Standing Rock Agency: Washington, DC, USA, 1910. Available online: https://catalog.archives.gov/id/5634369 (accessed on 21 August 2025).

- U.S. Library of Congress, Research Guides. Reservations and Allotments, in Native American Spaces: Cartographic Resources at the Library of Congress. Available online: https://guides.loc.gov/native-american-spaces/cartographic-resources/reservations-allotments (accessed on 21 August 2025).

- Hoffmeister, H. The Consolidated Ute Indian Reservation. Geogr. Rev. 1945, 35, 601–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Middleton, E.R. Seeking Spatial Representation: Reflections on Participatory Ethnohistorical GIS Mapping of Maidu Allotment Lands. Ethnohistory 2010, 57, 363–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenwald, E. Allotment in Severalty: Decision-making During the Dawes Act Era on the Nez Perce, Jicarilla Apache, and Cheyenne River Sioux Reservations. Ph.D. Thesis, Yale University, New Haven, CT, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Greenwald, E. Reconfiguring the Reservation: The Nez Perce, Jicarilla Apaches, and the Dawes Act, 1st ed.; University of New Mexico Press: Albuquerque, NM, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Greenwald, E. (Historical Research Associates, Inc., Missoula, MT, USA). Personal communication, 2020.

- Palmer, M. Sold! The Loss of Kiowa Allotment in the Post-Indian Reorganization Era. Am. Indian Cult. Res. J. 2011, 35, 37–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kretzler, I. Archives of Native Presence: Land Tenure Research on the Grand Ronde Reservation. Am. Indian Cult. Res. J. 2017, 41, 45–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kretzler, I. An Archaeology of Survivance on the Grand Ronde Reservation: Telling Stories of Enduring Native Presence. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Washington, Seattle, WA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Egbert, S.; Smith, P. “Great Frauds and Grievous Wrongs”: Mapping the Loss of Kickapoo Allotment Lands. In Native American Symposium, Representations and Realities; Southeastern Oklahoma State University: Durant, OK, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, A.G. Allotting the Omaha Reservation: Patterns and Impacts, 1884–1940. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Kansas, Lawrence, KS, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Dippel, C.; Frye, D. The Effect of Land Allotment on Native American Households During the Assimilation Era. 2021; unpublished manuscript. Available online: https://dustindfrye.com/files/dawes_.pdf (accessed on 13 July 2025).

- Dippel, C.; Frye, D.; Leonard, B. Property Rights Without Transfer Rights: A Study of Indian Land Allotment, 67 pp. Natl. Bur. Econ. Res. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Village Earth Native Lands Advocacy Project. Pine Ridge Land Information System. Available online: https://nativeland.info/maps/pine-ridge-land-information-system-prlis/ (accessed on 21 August 2025).

- Webb, W.P. The Great Plains; Ginn and Company: Boston, MA, USA, 1931. [Google Scholar]

- Brooks, A.; Jacon, S.; Bedeau, M. (Eds.) Homesteading and Agricultural Development Context; South Dakota State Historical Preservation Center: Vermillion, SD, USA, 1994.

- Bureau of Land Management. General Land Office Records. Bureau of Land Management. Available online: www.glorecords.blm.gov (accessed on 28 June 2025).

- United States, Bureau of Indian Affairs. Indian Census Rolls, 1885–1940. National Archives and Records Administration. Available online: https://www.archives.gov/research/census/native-americans/1885-1940.html (accessed on 28 June 2025).

- ESRI. ArcGIS Pro. Standard Distance. Available online: https://pro.arcgis.com/en/pro-app/latest/tool-reference/spatial-statistics/standard-distance.htm (accessed on 23 August 2025).

- White, C.A. A History of the Rectangular Survey System; Department of the Interior, Bureau of Land Management: Washington, DC, USA, 1983.

- Wishart, D.J. An Unspeakable Sadness: The Dispossession of the Nebraska Indians; University of Nebraska Press: Lincoln, NE, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- United States Department of the Interior. Annual Report of the Commissioner of Indian Affairs to the Secretary of the Interior for the Year 1871; GPO: Washington, DC, USA, 1871; Retrieved from the University of Wisconsin Digital Collections. Available online: https://search.library.wisc.edu/digital/AGUE2MXEEDR2LD8B (accessed on 14 July 2025).

- United States Department of the Interior. Annual Report of the Commissioner of Indian Affairs to the Secretary of the Interior for the Year 1872; GPO: Washington, DC, USA, 1872; Retrieved from the University of Wisconsin Digital Collections. Available online: https://search.library.wisc.edu/digital/ASDQ2JVRPCCT2N8T (accessed on 14 July 2025).

- United States Department of the Interior. Annual Report of the Commissioner of Indian Affairs to the Secretary of the Interior for the Year 1883; GPO: Washington, DC, USA, 1883; Retrieved from the University of Wisconsin Digital Collections. Available online: https://search.library.wisc.edu/digital/AUSIINXBHKS3GO8P (accessed on 14 July 2025).

- United States Department of the Interior. Annual Report of the Commissioner of Indian Affairs to the Secretary of the Interior for the Year 1885; GPO: Washington, DC, USA, 1885; Retrieved from the University of Wisconsin Digital Collections. Available online: https://search.library.wisc.edu/digital/AC5UOFLSZHEGOL8A (accessed on 14 July 2025).

- Jensen, J.M. Native American women and agriculture: A Seneca case study. Sex Roles 1977, 3, 423–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bobroff, K.H. Retelling Allotment: Indian Property Rights and the Myth of Common Ownership. Vanderbilt Law Rev. 2001, 54, 1557–1624. Available online: https://scholarship.law.vanderbilt.edu/vlr/vol54/iss4/2 (accessed on 14 July 2025).

- Strong, W. Quoted in Prucha, F.P. The Great Father: The United States Government and the American Indians; University of Nebraska Press: Lincoln, NE, USA, 1984; Volume 1, p. 672. [Google Scholar]

- Randell, H.; Curley, A. Dams and Tribal Land Loss in the United States. Environ. Res. Lett. 2023, 18, 094011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lawson, M.L. Dammed Indians: The Pick-Sloan Plan and the Missouri River Sioux, 1944–1980; University of Oklahoma Press: Norman, OK, USA, 1982; ISBN 0-8061-2672-8. [Google Scholar]

- Indian Land Tenure Foundation. Land Issues. Available online: https://iltf.org/land-issues/issues/ (accessed on 11 September 2025).

- Royster, J.V. The Legacy of Allotment. Ariz. State Law J. 1995, 27, 1–78. [Google Scholar]

- Shoemaker, J.A. Like Snow in the Spring Time: Allotment, Fractionation, and the Indian Land Tenure Problem. Wis. Law Rev. 2003, 4, 729–788. [Google Scholar]

- Cobell v. Salazar. 573 F.3d 808, United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit, 2009. Retrieved from FindLaw. Available online: https://caselaw.findlaw.com/court/us-dc-circuit/1385636.html (accessed on 14 July 2025).

- United States Department of the Interior. Land Buy-Back Program for Tribal Nations. U.S. Department of the Interior. 25 April 2016. Available online: www.doi.gov/buybackprogram (accessed on 14 July 2025).

| Year | Allottee Roll Numbers | Annual Number of Allotments | Cumulative Number of Allotments | Percent | Cum. % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1906 | 1–871 | 871 | 871 | 18.5% | 18.5% |

| 1907 | 872–2494 | 1623 | 2494 | 34.5% | 53.0% |

| 1908 | 2495–3768 | 1274 | 3766 | 27.1% | 80.1% |

| 1909 | 3769–4026 | 258 | 4026 | 5.5% | 85.6% |

| 1910 to end | 4027–4726 | 673 | 4699 | 14.3% | 99.9% |

| Tribe | Allottees | % of Allotments | Acres Allotted | Hectares | % of Land Allotted Allotted |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blackfoot | 780 | 17% | 221,548 | 89,657 | 16% |

| Hunkpapa | 1679 | 36% | 491,112 | 198,746 | 36% |

| Lower Yanktonai | 1168 | 25% | 326,420 | 132,097 | 25% |

| Upper Yanktonai | 415 | 9% | 120,488 | 48,760 | 9% |

| Other/Blank | 657 | 14% | 183,184 | 74,132 | 15% |

| Total | 4699 | ------- | 1,342,752 | 543,392 | - |

| Age and Sex Category | Number | Acres | Ha | Mean Acres | Mean Ha |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adult Men ≥ 18 | 1028 | 535,401 | 216,669 | 521 | 210.8 |

| Boys < 18 | 1231 | 206,516 | 83,574 | 168 | 68.0 |

| Adult Women ≥ 18 | 1102 | 378,036 | 152,986 | 343 | 138.8 |

| Girls < 18 | 1319 | 218,794 | 88,542 | 166 | 67.2 |

| Not reported | 19 | 4005 | 1621 | 211 | 85.4 |

| Total | 4699 | 1,342,752 | 543,392 | 286 | 115.7 |

| Num. of Parcels | Num. of Allottees | Percent |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 3030 | 64.48% |

| 2 to 6 | 1351 | 28.75% |

| ≥7 | 318 | 6.77% |

| Measure (km) | 1906 | 1907 | 1908 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Median | 5.28 | 5.20 | 27.55 |

| Standard Deviation | 9.17 | 14.98 | 23.52 |

| Measure (km) | 1907 | 1908 | 1909 | Post-1909 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median | 5.25 | 20.81 | 26.70 | 21.53 |

| Standard Deviation | 15.54 | 26.63 | 21.49 | 20.00 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the International Society for Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Egbert, S.L.; Meisel, J.J. Geospatial Impacts of Land Allotment at the Standing Rock Reservation, USA: Patterns of Gain and Loss. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2025, 14, 363. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijgi14090363

Egbert SL, Meisel JJ. Geospatial Impacts of Land Allotment at the Standing Rock Reservation, USA: Patterns of Gain and Loss. ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information. 2025; 14(9):363. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijgi14090363

Chicago/Turabian StyleEgbert, Stephen L., and Joshua J. Meisel. 2025. "Geospatial Impacts of Land Allotment at the Standing Rock Reservation, USA: Patterns of Gain and Loss" ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information 14, no. 9: 363. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijgi14090363

APA StyleEgbert, S. L., & Meisel, J. J. (2025). Geospatial Impacts of Land Allotment at the Standing Rock Reservation, USA: Patterns of Gain and Loss. ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information, 14(9), 363. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijgi14090363