Abstract

This study investigates residential segregation and housing types in Craiova, Romania, with a particular focus on the disparities shaped by historical and contemporary urban developments. Using collected data from former hostels built for young workers during the communist era, this research maps and analyzes the spatial distribution and living conditions of these housing types at a neighborhood level. Key metrics such as the number of inhabitants, the surface area of rooms, the current occupancy rates, and the number of unoccupied rooms were collected. Additionally, residential segregation is measured using indices of dissimilarity, isolation, exposure, concentration, and centralization, providing a comprehensive view of the socio-spatial divides within the city. The findings indicate significant disparities between these buildings with unsuitable living conditions and the newer residential developments, revealing a clear urban divide. No differences have been identified in terms of access to urban services like education, health, green areas, banks, or supermarkets, despite the appropriate location differences being noted in access to water and gas supply, and internet services. This study contributes to the understanding of how housing types and access to services in Craiova shape patterns of residential segregation, and it suggests policy interventions aimed at mitigating the negative impacts of these urban divides.

1. Introduction

For the last several decades, the focus on housing has increased considerably, being at the forefront of debates led by researchers, governments, and NGOs alike. On one hand, housing is viewed as a social good, i.e., a basic human need and a right that should be accessible to all, regardless of income. On the other hand, it is increasingly considered a commodity for profit, a vehicle for wealth accumulation. Eurostat publishes statistics on living conditions and housing regularly, highlighting the major differences within European countries in terms of the size of housing and its quality. Thus, while more than two-thirds of Europeans own their home, in Romania, their share peaks at a staggering 95% [1], with the young generations, just like their parents and grandparents, dreaming of owning their homes [2]. However, the size of the housing in Romania is the smallest within the EU, and the overcrowding rate is among the highest [1], thus impinging on the overall quality of housing.

The current paper focuses on a particular type of dwelling in Romania that was built during the socialist period in all the industrial cities, namely the dormitories for young workers, which were the smallest types of dwellings and, hence, were overcrowded for the longest period of time and offered the poorest living conditions. Dormitories were built by factories to provide accommodation for the young male workers coming from further villages or cities, crowding up to 10 people in a room with no bathroom or kitchen, in conditions resembling the army [3]. The case study presents the current situation of these dormitories in Craiova, one of the second-tier cities in Romania. The main research question of the current study focuses on how historical legacies of socialist-era housing policies shape contemporary residential segregation in post-socialist cities. The primary objective of this study is to analyze the spatial distribution of former dormitories for young workers in Craiova, so as to quantify the extent of residential segregation using a range of indices. The second objective is to analyze these dwellings from the point of view of adequate housing, as defined by UN-HABITAT, and to explore the socio-economic factors driving these patterns.

2. Theoretical Background

Housing rights have been the focus of numerous organizations and international covenants, with the Universal Declaration of Human Rights ([4], art. 25) and the International Covenant on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights being the staples in this domain. Despite the fact that international organizations, transnational commissions, and governments alike work for incorporating housing rights in their legislation, housing is still at the core of spatial injustice and territorial unevenness [5].

2.1. Adequate Housing

The right to adequate housing is among the core human rights stipulated by international laws. Ever more researchers point to the fact that this should be enshrined in the Constitution of each country [6]. In order for housing to be adequate, several key elements have been identified by the UN, such as affordability, habitability, availability of services and infrastructure, accessibility for marginalized groups, and location [7]. The right to adequate housing is one of the major focuses for the European Commission, which calls for housing to be of an adequate standard, affordable, and accessible to all [8].

Adequate housing has been recognized as one of the key dimensions of quality of life. Thus, the OECD’s Better Life Index ranks housing among 11 dimensions, including indicators such as housing expenditure, rooms per person, households without basic facilities, and affordability [9]. Adequate housing has proven to be, to a large extent, only a desideratum, since all over the world, there are low-income households where scarce family resources must cover the need for food, medical care, housing, and other necessities. Quite frequently, these unmet needs lead to the emergence of poverty neighborhoods and eventually segregation.

2.2. Residential Segregation

The concept of urban segregation was been addressed for the first time more than a century ago by scholars from the Chicago School of Sociology, who analyzed immigrant settlements and has considerably evolved into a complex and multi-dimensional process, with some peculiarities from region to region. The main focus is on social differences in Europe, race and ethnicities in the US, class in Latin America, or religious segregation places such as Belfast, Nicosia, or Israel [10]. For the European context, a vast amount of research has shown the importance of specific regional histories and contexts of interventions [11,12,13] due to four structural factors, namely social inequalities, global city status, welfare regime, and the housing system [14]. However, throughout Europe, the welfare state plays a great role in reducing social inequality and, hence, residential segregation [14].

The existing literature outlines that residential segregation is a multidimensional phenomenon encompassing five distinct dimensions: evenness, exposure, concentration, centralization, and clustering [15], with the index of dissimilarity and exposure index being traditionally used [16,17]. However, recent advancements include spatial, global, and local versions of segregation indices, allowing for a multiscale analysis [18]. The local spatial entropy-based diversity index (SHi) and local spatial isolation index (Si) are recommended to capture evenness and isolation dimensions at the neighborhood level [19].

Urban divides, in terms of the differences and inequalities of various social, economic, and demographic groups distributed across different neighborhoods of a city, can manifest in the form of socioeconomic status, housing types, access to services, ethnic or racial segregation, or spatial segregation. Recent research on urban divides, like residential segregation, highlights their multifaceted nature and evolving dynamics. Studies emphasize the importance of spatial factors in measuring segregation and the need for models incorporating social dynamics to understand its causes and consequences [20]. Income-based segregation has gained attention, with research examining its dimensions in urban Canada and potential impacts on access to opportunities [21]. Current research trends focus on tracing the evolution of segregation theories, analyzing characteristics of urban residential segregation, exploring driving mechanisms, and providing future perspectives to support urban planning and policy development [22]. These studies highlight the complexity and ongoing relevance of residential segregation in shaping urban landscapes and social outcomes.

Residential segregation, a persistent feature of urban environments, reflects socio-economic and historical divisions within cities. It emerged especially with the rise of industrial capitalism, separating workplaces from residences and creating a distinct housing market that mirrored class relations in urban spaces [23]. Globally, patterns of segregation have evolved in response to industrialization, urbanization, and socio-political forces. In contemporary Europe, while segregation levels remain relatively modest compared to other parts of the world [12,13,14,24], the spatial gap between rich and poor is widening across capital cities. This trend is attributed to factors such as welfare and housing regimes [24]. Many European countries have stronger social welfare systems and more robust public or social housing policies [11,25], while in the US, policies like redlining and urban renewal exacerbated racial and class segregation [26]. Other factors include globalization, economic restructuring, rising inequality, and historical development paths [24], such as urban development patterns, as well as racial history and immigration. European cities grew around dense historical centers long before the car, making walkability and mixed-use neighborhoods more common. Moreover, most European cities became increasingly diverse only after WWII immigration, not having the same legacy of slavery and institutional racism [27]. In Eastern Europe, including Romania, urban spaces were profoundly shaped by the socialist period, when large-scale housing projects were built for industrial workers. After 1990, the transition to a market economy exacerbated the socio-economic inequalities, which in turn, have reshaped urban spaces.

Residential segregation is often analyzed using several key indices that describe distinct dimensions of spatial and social division within urban areas. The most used indices are the dissimilarity index (D), the isolation index (P), the exposure index (xP), and the concentration (C) and centralization (Ce) indices. Used initially in research describing segregation patterns in the United States, they have been used lately in other studies. The index of dissimilarity (D) is widely used to measure the evenness of the distribution of two groups across neighborhoods, indicating the percentage of one group that would need to move to achieve an even distribution. This index has been applied globally to assess racial, ethnic, or socioeconomic segregation patterns [15], helping researchers understand the distribution of minority groups compared to majority populations. The isolation index (P), which measures the likelihood that a member of a particular group will interact with others from the same group within their neighborhood, shows that high isolation values reflect both physical clustering and social isolation of minority groups. It has been frequently used to examine minority segregation in metropolitan areas [28]. In contrast, the exposure index (xP) captures the probability that members of one group will come into contact with members of another group, often used to assess intergroup contact in various spatial settings [15].

The concentration index (C) quantifies the extent to which a minority group is spatially concentrated in a limited area, with higher values indicating that the group occupies a smaller, densely populated space. Researchers often apply this index to examine whether groups are segregated into defined neighborhoods, particularly in discussions about urban poverty and marginalized communities [29]. Finally, the centralization index (Ce) evaluates whether a group is concentrated toward the urban center or spread toward the periphery, with higher values indicating greater centralization. This measure is frequently used to explore historical processes of ghettoization or suburbanization [30]. The concentration index (C) and centralization index (Ce) are important measures of spatial segregation. Egan et al., 1998, identified mathematical and conceptual issues with Massey and Denton’s relative concentration index, which influenced segregation research and Census Bureau analyses. Massey et al., 1996, reaffirmed the multidimensional nature of residential segregation, including concentration and centralization, but found that some indices performed less effectively in 1990 compared to 1980. They recommended maintaining the same indices for continuity. Folch and Rey, 2016, introduced a local segregation measure that is applicable to any location within a metropolitan area, which can identify the group more concentrated around a reference point and determine the statistical significance. This measure allows for the creation of hot spot maps and can prompt investigations into why certain groups are significantly concentrated in specific areas [31,32,33].

These indices have been applied in various international studies to examine ethnic, racial, and socioeconomic segregation patterns, and although they are less frequently used in Romania, they hold the potential for understanding similar dynamics in post-communist urban restructuring [34].

The last decades saw a surge in research focused on the peculiarities of segregation within former socialist countries, which had a less segregated and spatially compact city with socially mixed neighborhoods [14,35,36,37] due to the socialist past. However, most of the research focuses on capital cities in the East [12,14,35,36]. The Romanian capital city provides good grounds for documenting spatial segregation [38,39], as well as vertical separation, showcasing clear patterns of within high-rise apartment building segregation based on socio-economic status and demographic characteristics [37,40]. When second-tier cities are considered, most often the focus is on the ethnic segregation of Roma people [41,42,43,44]. This research is significant, as it provides a detailed analysis of residential segregation in a post-socialist urban context for a second-tier city, focusing on the former dormitories built for young workers that have now become collective housing for families with a low income. By highlighting the socio-spatial characteristics of former dormitories for young workers within Craiova city, this study contributes to the broader research on urban inequality and segregation in Eastern Europe. The findings can be used in local government strategies to address housing inequalities, providing a more correct access to basic utilities and promoting more inclusive urban development.

2.3. Overview of the Socialist Outlook on Housing

The housing sector in Romania, just like elsewhere in socialist countries, was characterized by uniformity and standardization of new construction [45]. However, it was not as resource cost-conscious [46], despite the government’s intention to maximize its economic efficiency following the typified design [47].

Housing access and housing quality in cities have been problematic in Romania throughout almost the entire 20th century, up to the late 70s [48]. Although housing was one of the major intervention programs of the communists, it was clearly secondary to collectivization and the nationalization of the industry [49]. After a short period of confusion and transition in Romanian architecture in the 1950s, the party leadership eventually clarified the situation [50]. The architectural conception was no longer an individual pursuit. The individual house was replaced with collective mass housing, and thus, architecture was transformed into urban planning [51], which led to ‘a trauma of a profession’ despite some major accomplishments [47].

In the 1950s and 1960s, the solution to the housing problem for the increasing urban population was to establish the minimum dwelling area at 8 sqm per person [52] and standardize the two room apartment to an area of 24 sqm—the ‘quintessence of comfortable and economical contemporary living for a three-member family’ [53]. As [54] argues, there was no ‘communist comfort’; ‘you could have either communism or comfort’. The authorities acknowledged that it was quite drastic, but that was the only solution at that time, and exceptions could be made. In the words of the then Prime Minister Petru Groza: ‘we will grow out of this phase. We won’t make cages for everybody’ [55]. Exceptions from this norm were made for the heroes of socialist work and other categories, their dwelling area increasing by 10 to 20 sqmeters [56]. In the 1970s, while the average rate of house building (7.1 dwellings per 1000 inhabitants) reached levels similar to the highest rates registered by Western countries, the quality of the homes that were built was incomparably worse [57].

Beginning in 1981, a new law (216/3 August 1981) modified the standards for both public and private housing (built by citizens that borrowed money from the bank), stipulating the standard size for each type of apartment and the norm of dwelling space per person (10 sqm). The small size of apartments, together with the rural exodus and pronatalist policy of the government, led to overcrowding in most of the urban dwellings [58]. Overcrowding has been a major communist legacy in all of the Eastern European countries [59], and according to international statistics, it still is a problem for most households in Romania, where 40.5% of the population lives in an overcrowded home [60]. While during the last three decades the overcrowding rate in the country has decreased, one-room units are definitely the most likely to face severe overcrowding [45]. The workers’ dormitories, sometimes called hostels for young workers—one room units—are the epitome of overcrowded and poor housing conditions in Romania.

Dormitories for young workers have been generally included in the slum category, and can be found in all Romanian cities, no matter the size or economic profile [61]. Each large industrial unit built its own dormitories in the city, in the proximity of the factory, where the young workers who were single (hence their Romanian name ‘camine de nefamilisti’) and moving from the rural area to the city were accommodated until they became married. The newly built communist city no longer allowed for any sort of divides, with highly educated people living close to the less skilled ones. Moreover, differences in wealth were quite mitigated in quite a short period of time. The city helped the communists to ‘shuffle people’ as one would cards, gathering ‘packets’ of different forms and colors [62], with state housing promoting a socio-economic mix [63]. In the same neighborhood, one could find the socialist blocks of flats with low and high levels of comfort, as well as workers’ dormitories with the lowest living standard [64].

These dormitories usually had five floors, with each level having a common bathroom, toilet room, and kitchen. The rooms varied in terms of comfort and size, allowing for the accommodation of 2, 4, 5–10, or more than 10 persons. Only the smaller rooms, destined for two or four persons maximum, could have their own toilet room. According to the law [65], they were considered third-grade comfort dwellings. In the early 1990s, there were some 3700 such units in Romania, including 4680 buildings totaling more than 521,000 bed places, with an average of 3.9 persons/room [66]. The average area of such a room was around 18 sqm, which means only half of the mean area of urban dwellings (34 sqm in 1992) [66]. Although they were destined for the same categories of urban workers, there are slight differences regarding the average area of a room in such hostels: around 19–20 sqm in Craiova, Constanta, and Galati, and only 15 sqm in Timisoara. This may be due to the somewhat different timeframes for their construction and the regulations in place.

In the 1990s, with the collapse of industry and increasing unemployment, many workers who were fired and who resided in these dormitories returned to their native villages, with the decaying dormitories becoming ‘withdrawing places for the poor people’ [61]. With the disintegration of industries, the property rights for these buildings were something of a grey area, sometimes being occupied by new undocumented informal dwellers in need of shelter [3,67]. The managers of the newly privatized industrial units took different decisions regarding these dormitories, and in the 2000s, the syntagm dormitories for young single workers/camine de nefamilisti pointed to quite different realities [68]. Some of them were completely abandoned and rapidly decayed [3,68,69], while others were taken by the local administrations, partially upgraded and turned into social housing [3,64,68,70]. Meanwhile, others were sold to former tenants [68,69,70,71] or to private investors who initially allowed former employees who rented the rooms to stay. During the transition period, they formed ‘islands’ of extremely precarious dwelling conditions in the cities [68,72], being disconnected from basic facilities and oftentimes illegally connected to some facilities (mainly electricity) [67]. Hence, they were frequently labeled as ‘(Roma) ghettos’ [3,67,69,71] or the ‘slums of Romania’ [73], since they did not provide the minimum bare necessities for their inhabitants (in terms of floor area, lack of kitchen, bathroom and building materials or access to basic utilities).

The number of units that were registered as dormitories for single workers that were still inhabited fell considerably during the transition period. The pace was somewhat slower in the 1990s, but increased considerably in the early 2000s. The census in 2011 registered only 331 units with 417 buildings, which means only 5% of the stock in 1992 (Table 1).

Table 1.

Single workers’ dormitories in Romania.

After 1990, the state was no longer a developer of the housing stock, but it still assumed a central role in the market due to legislation and its institutions [5]. The blocks of flats erected during the socialist period have considerably influenced the life and dynamics of cities, also during the post-communist period [74]. The privatization of the public housing stock took place rapidly and without the interim step of transferring to the local government, as elsewhere in the socialist countries [75]. This process was highly favorable for the tenants, in just a short period, allowing many households to own their homes free of debt. This ‘give-away’ privatization [63,76] caused the transfer of ‘a significant share of national wealth to private households’ [45]. Consequently, it was generally assumed that housing would be very important for the economic restructuring of the former socialist countries since no other sector directly affected the lives of so many people [75]. In Romania, housing is super-commodified and is an important financial asset [77], despite the fact that most of the dwellings are 40 to 60 years old, requiring investments for upgrading and providing adequate living conditions [78].

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Study Area

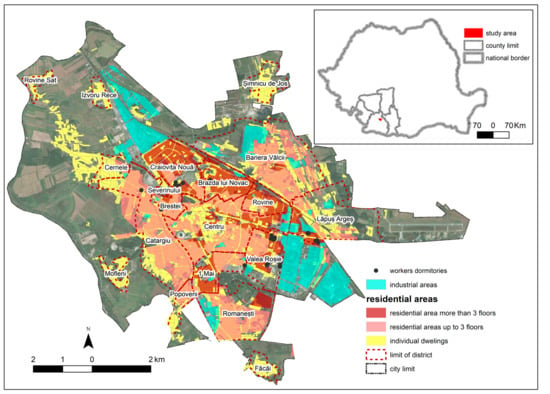

Craiova, located in the southwestern part of the country, is one of the second-tier cities in Romania, and for the last five centuries, it has been one of the major demographic and economic centers in this part of the country, sometimes ranking second after the capital city, Bucharest [79]. Although it emerged in the Middle Ages as a center with important administrative functions and later added commercial functions, it was mainly an agricultural town until the socialist period. Beginning with the 1950s, massive investments toward industrialization brought the city completely new functions. Craiova became the leading center for the automotive industry, with several major factories—Electroputere, manufacturing electric engines, high voltage transformers (75% of the national production), and electric Diesel locomotives (60% of the national output) [80]; 7th November manufacturing tractors and agricultural machinery; and OltCit, a joint venture with Citroen, producing passenger cars. All these factories were located at the outskirts of the city, in the eastern part, with the industrial platform stretching over ha. There were also other industrial units here, such as the Heavy Machinery Factory and the Factory for Repairing Rolling Equipment. In the western part, there was another major industrial platform where some of the leading chemical and thermal power plants in the country were functioning. Each and every one of these industrial units employed thousands of workers. The largest one, Electroputere, had more than 11,000 employees in the late 1980s, with an average age of only 26.5 years old [80]. Most of these workers were rural migrants who needed a place to live. Hence, in line with the dwelling policy at that time, every major industrial unit had entire neighborhoods built nearby to accommodate this workforce. The younger ones who were still single were entitled only to a bed in a room in the workers’ dormitories. Consequently, in the eastern part of the city, there were the most numerous such buildings. Some of them (those from Valea Rosie neighborhood) were built in the 1950s, which makes them some of the first and oldest dwellings built during the socialist period. All these dormitories were built before the 1977 earthquake. None of them were located at the outskirts of the city (Figure 1), and in less than a decade, they were surrounded by numerous other blocks of flats with varying degrees of comfort.

Figure 1.

Location of the study area.

3.2. Data Collection and Analysis

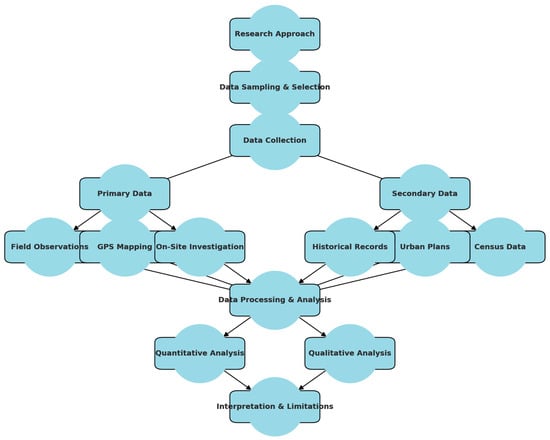

This study uses a mixed-methods approach that combines a quantitative spatial analysis with qualitative historical insights. This allows for a thorough exploration of the socio-spatial patterns in the city. The research includes several key elements: data sampling, data collection, ethical considerations, and data analysis (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Methodological flowchart.

The present study focused on the location and analysis of the living conditions in the collective residential buildings built during the communist era for former industrial workers, namely the workers’ dormitories. Currently, the rooms in these dormitories continue to be lived in, being bought by some of the former tenants who could only afford to buy this type of dwelling, and transformed into a tiny studio apartment. The location of these collective buildings was mapped together with the new collective residential complexes, analyzing the facilities, as well as the access to the main urban services, as the location is very close to the two housing types. However, the study focuses on the former dormitories for young workers, not any other types of collective or individual housing in Craiova.

For data collection, both primary and secondary data are used to create a comprehensive dataset. Field observations were conducted to assess the access to services and the physical condition of the housing units, including the general apartment building characteristics (age, size, layout, orientation, and exterior), structural features (story height and construction technology), common building areas (entrance, corridors, and stairs), building lot (parcel conditions and presence and quality of common areas), and other characteristics (utilities, roof condition, and fire escape), as detailed by [81]. GPS mapping is used to record the locations of the analyzed residential areas. Secondary data are collected from the national census information, official urban plans, and historical records detailing the development of worker housing during the communist era. Data on the height regime of the residential buildings and functional areas of the city were retrieved from the Urban General Plan of Craiova city. The number and limits of the city districts and the number of residents for each district were established based on existing documents and information provided by the Regional Bureau of Statistics and City Hall. Twenty-six collective buildings that belong to former industrial workers were identified on site based on reviews of previous studies [82], information provided by former employees of the City Hall, and a firefighter who periodically verifies some of these places. Data about the number, surface area, and current occupancy of these apartments were collected on site in July–August 2024 by investigating the lists of current expenses. Spatial mapping techniques were employed to visualize the distribution of these housing types across Craiova’s districts.

The criteria for housing adequacy are those used by UN-HABITAT [7], namely (i) legal security of tenure—documents that guarantee occupants legal protection against forced eviction and other threats; (ii) availability of services, materials, facilities, and infrastructure (safe drinking water, adequate sanitation, energy for cooking, heating and lightning, sanitation and washing facilities, etc.; (iii) affordability—housing costs do not threaten the occupants’ other human rights; (iv) habitability—adequate floor space, protection against cold, damp, heat, rain, or health and structural hazards; (v) accessibility for marginalized groups; (vi) location so as to allow access to employment, healthcare, and schools; (vii) cultural adequacy.

To quantify residential segregation in Craiova, five key indices were employed: dissimilarity, isolation, exposure, concentration, and centralization (Table 2). These indices provide the statistical framework to assess the socio-spatial divides in housing distribution, particularly between the former industrial worker residences built during the communist era. The indices, used in other research studies, were calculated using the following equations.

Table 2.

Selected segregation indices.

The segregation group (X) considered in this study is represented by the residents of the 26 building blocks selected and the reference group (Y), which depending on the calculated index, is the whole population of the city (Y) or the population within the neighborhood where each former dormitory is located (Yi). We focused on this special type of collective housing, as it originated as a form of temporary housing for former non-family industrial workers. Another reason was that, currently, the rooms have become private property after being purchased by the former tenants and are also inhabited by families with children, who continue to use the kitchens and bathrooms in the corridors on each floor as common spaces. Despite the small living spaces also present in other blocks (built in the same communist period), no other form of collective housing in Craiova has shared kitchens or bathrooms, aspects which point to a lower quality of living. For these reasons, all 26 former dormitories for young workers were considered representative of a particular social profile and selected for this case study.

On the other hand, for the same reasons mentioned above, the surrounding reference population was considered to be different from that living in the workers’ hostels and treated as being relatively homogeneous across the city. As this is not entirely true, differences in living quality exist between collective buildings, especially in terms of living space. We focused only on the residents of the selected buildings as shared spaces, and limited access to utilities (water and gas) makes up an important part of living quality.

The data analysis includes both quantitative and qualitative approaches. The quantitative analysis focuses on spatial segregation and includes the calculation of standard indices, such as dissimilarity, isolation, exposure, concentration, and centralization. These indices help quantify the socio-spatial divides within Craiova. Geographic Information System (GIS) tools are used to map the distribution of housing types. The qualitative analysis highlights the residents’ experiences of housing conditions and access to services. A historical analysis is also conducted to provide background on Craiova’s housing patterns, shaped by industrialization and communist-era policies.

Despite the robust design, the methodology does have limitations due to limited access or non-existent information on the number of inhabitants, the surfaces of new residential complexes, or the amenities of individual housing. The information about the revenues of the inhabitants of different housing types is not available. It is also important to note that research choices, such as geographical boundaries and grouping systems, can significantly influence segregation measurements [18]. Additionally, the study captures a snapshot in time, and future research will need to account for changes in urban dynamics over the long term.

4. Results

Urban divides in Craiova are strongly tied to housing types and their construction period. Most of the collective residential units were built between 1965 and 1985. New residential buildings, built especially after 2010, are scattered all over the city, occupying former industrial lands or located at the borderline between blocks and houses.

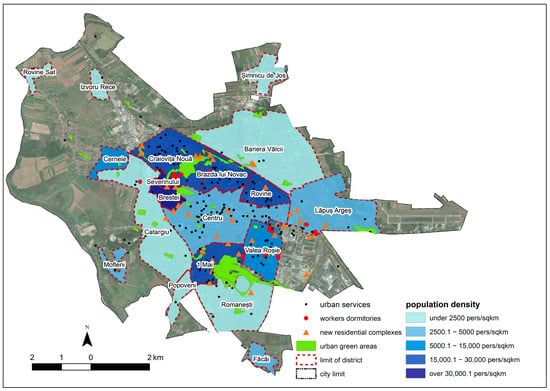

The site investigations led to the identification of 26 buildings initially functioning as dormitories for young workers. They are mainly located in areas with collective buildings and high population densities (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Location of former dormitories for young workers and new residential complexes.

4.1. Adequate Housing

Currently, only one of them is administered by the local authorities, offering social housing. It is the only one having much larger dwellings (65 sqm). The remaining 25 buildings are private property, and there are no issues regarding the security of tenure. Since they are not located on the outskirts of the city, but rather quite close to the city center and within the oldest neighborhoods, basic urban services, leisure facilities, and good connections to the transport infrastructure are available. Other research on urban service access highlights issues related to affordability and service reliability. In their study, Crețan and Turnock [87] discuss marginalization within Romanian cities, pointing out that older worker accommodations, such as these dormitories, tend to suffer from inadequate infrastructure and social segregation [87]. Additionally, Vincze, 2015, examines how precarious housing conditions contribute to spatial deprivation, particularly for lower-income workers [88]. These studies underline the disparities in service provision and the role of collective and individual responsibilities in maintaining urban utilities.

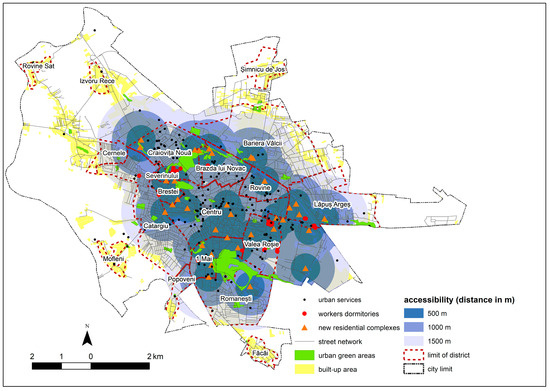

Moreover, location can be considered one of the main characteristics for adequate housing in this case, since they are located within walking distance of public transport stations, schools, and medical facilities. Location, in this case, does not impinge on employment possibilities (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Access to key urban services.

The main issue these former dormitories for young workers face is related to habitability, i.e., adequate space for their inhabitants and protection against cold, damp, and heat. These dormitories were historically designed to provide temporary accommodation for workers, and their infrastructure has often remained outdated. The provision of essential services, such as water, electricity, and heating, in these dormitories follows a dual system. Some utilities are accessed individually, while others are managed collectively. This division of responsibility influences both the stability of access and the financial burden on the residents. In the case of electricity, it is commonly provided on an individual basis, with each unit or room having its own electricity meter. This means that residents are responsible for their own consumption and timely payment of bills. Failure to pay results in service disconnection for the individual unit, rather than for the entire building. In contrast, water supply and heating systems are often managed collectively, with costs divided among all tenants. This collective approach implies that non-payment by some residents can affect the entire building, leading to potential service disruptions, which was often observed for some of the collective units located especially in Valea Roșie and Craiovița Nouă. Consequently, tensions may arise within these communities, as responsible payers might suffer from the negligence of others. A better solution for providing access to utilities may be a system that introduces a prepaid service supply for water and heating systems or alternative billing mechanisms. Unfortunately, this type of system is not common for any type of housing in Craiova. This could also be a good solution to mitigate conflicts between individual and collective responsibilities. Addressing these issues is crucial for improving living conditions in former worker dormitories and ensuring equitable access to essential urban services.

The usual size of a dwelling is generally 20–21 sqm, with only one building with much larger rooms, reaching up to 65 sqm. The average area is around 23 sqm/dwelling. On average, there are 1.58 persons/dwelling and an average living area of 14.84 sqm/person (the surfaces of uninhabited rooms were excluded), which is below the national urban threshold for precarious living conditions (15.33 sqm/person), qualifying them as overcrowded dwellings [82]. These buildings still preserve common toilets, showers, and kitchens, although in many cases (half of the buildings), the owners improvised in their apartments small toilets and kitchenettes. Protection against the cold is one of the major problems, since less than a fifth of them are connected to the heating system provided by the municipality, and even fewer are connected to the gas lines. Hence, for most of these dwellings, there is no central heating system, with everybody relying on air conditioners and some electric heaters.

Overall, the former workers’ dormitories in Craiova fall short of the United Nations Human Settlements Programme (UN-Habitat)’s criteria for adequate housing. Only half of the key dimensions are met: security of tenure (these are not informal settlements; There is legal recognition of the property rights, and residents do not face evictions), location, and accessibility. The availability of services and infrastructure is quite debatable. In principle, they have access to all essential services and infrastructure, provided they can afford it. Affordability and habitability are the main issues faced by these residents. Housing costs in Romania have risen rapidly due to utility and energy price liberalization, placing additional financial strain on low-income households. Many families spend a higher share of their income on housing expenses, exacerbating the issues of affordability.

4.2. Residential Segregation

The values obtained after calculating the selected indices for residential segregation in Craiova indicate a multifaceted picture of spatial inequality and social division across the city. The highest values were obtained for the dissimilarity, exposure, and centralization indices, while the other two indices, the isolation and concentration indices, have low values (Table 3).

Table 3.

Indices of residential segregation.

The dissimilarity index (D), if found to be high (0.550), indicates that former industrial worker residences remain distinct from the rest of the residential buildings, suggesting persistent spatial divisions. This would align with the findings in other post-socialist cities such as Bucharest and Budapest, where former state-provided housing units remained segregated from new developments catering to middle- and upper-income groups [89]. The value obtained for the study area suggests a moderate segregation between the two different population groups: residents from the former hostels built for young workers and the rest of the city residents. A score of 0.550 indicates that 55% of the residents from one group would need to relocate to another district for an even distribution across the city. This points to a noticeable, though not extreme, division in residential patterns.

The isolation index (P) was used to reveal whether the present residents living in the former hostels remain within self-contained communities, having limited exposure to other social groups. The low value obtained for the isolation index (0.003) signifies a minimal interaction between specific groups within their own neighborhoods. This suggests that people living in these former hostels, despite segregation, are living in mixed areas rather than being spatially isolated in enclaves. This is the case for Craiova city, as around most of these poor living areas, new residential complexes have been built (Figure 4). Conversely, the exposure index (xP) quantifies the likelihood of cross-group interaction. In the case of Craiova city, a very high value registered for the exposure index (0.967) indicates that residents from the dominant group are highly exposed to others within their same group. This points to a pattern where the majority groups in Craiova largely live among themselves, reinforcing social homogeneity in certain neighborhoods like Valea Roșie and Lăpuș Argeș. The low concentration index (0.066) suggests that marginalized populations are not concentrated into a few spatially constrained areas, evidencing a more even spatial distribution, which has been seen in cities such as Prague, where policies promoting housing diversification have led to more mixed-use neighborhoods [90]. While segregation exists, it is not marked by a high-density clustering of disadvantaged populations. The last indicator, the centralization index (accessibility to urban core) has a relatively high value (0.636), which emphasizes that a substantial proportion of segregated, likely disadvantaged, populations live closer to the city center, suggesting that these units have retained their location advantage within the urban core, similar to patterns observed in socialist-era housing estates in Moscow, where working-class housing remains in central districts due to state-ownership transitions [91]. Most people living in disadvantaged buildings are at a distance of 1.5 to a maximum of 2 km from the city center. This suggests that socioeconomically vulnerable groups may inhabit centrally located districts, which could have implications for access to services and employment but may also reflect historically entrenched housing inequalities. This mirrors the experience of other post-socialist cities, where privatization and uneven development have reinforced existing spatial inequalities [92].

Overall, Craiova exhibits moderate levels of residential segregation, with socio-spatial divisions that do not isolate marginalized social groups completely but reflect a pattern of centralization and uneven exposure. Further investigation into the seven areas with inadequate housing conditions would provide deeper insight into the nature of this segregation and its impacts on urban inequality, which may suggest that former industrial worker housing remains segregated due to historical factors and economic constraints. Moreover, the city does not present any aspect of Roma ghettoization that was identified in Bucharest [69,71] or in other settlements in Romania [3,64,93] where former hostels for single workers exist.

This analysis contributes to understanding how segregation shapes urban divides in Craiova, revealing how population distribution intersects with housing quality and access to urban opportunities.

5. Discussion

The housing stock during the 20th century evolved in response to industrialization, urbanization, and changing social and economic conditions. As the number of immigrants to the cities skyrocketed in the early and mid-20th century, both in many Western countries and developing countries, the issue of housing, i.e., a sufficient number of dwellings and good quality dwellings, became ever more acute. The problem was worse for the less-skilled, poorer people, who often lived in overcrowded, poorly ventilated dwellings, with minimum amenities and limited privacy due to shared common areas and small rooms. Each country struggled to cope with this demand as best as it could, depending on its economic or political system. Many socialist countries built workers’ dormitories/hostels for young single workers, where more people working for the same factory shared a room and amenities. The privatization and/or bankruptcy of the industrial units that also owned and managed these dormitories led to changes in the purpose served and demographic characteristics of the current inhabitants of these hostels. Nowadays, workers’ dormitories still exist and are strongly reinforced in Asian countries, mainly in China, with the dormitory labor regime (DLR), where there are two forms of employer housing provisions, namely units for whole families outside the factories and housing for single-sex workers within the factory or close to it [94], with the focus on maximizing utilization of the temporary migrant workers [95], as well as in India where these regimes are part of a globalized strategy for controlling the migrant labour force [96]. The US also has a similar form of housing, namely single-room occupancy (SRO) hotels [97], which date back to the early 1900s and originated to accommodate transient urban workers who needed to stay close to urban jobs. They offer similar conditions to those in the hostels for single workers in Romania, i.e., small room/“partial rooms”, which lack complete private kitchens and plumbing facilities [98], and tenants sharing bathroom facilities located in the common areas of the buildings [99]. These SROs still exist in the US and are the most basic form of housing available in major cities such as New York, ‘the housing of last resort, the safety net at the bottom of the market providing shelter for the poor and near-poor’ [99], that still provide a significant share of America’s urban homes, with hotel residents numbering between 1 and 2 million people [100]. In a similar manner, these former hostels for single workers provide the cheapest urban dwellings, but in most cases in Craiova, the dwellers own the rooms. They are not tenants.

Among the EU countries, Romania ranks first regarding the share of people living in households owning their home, with a staggering 95%, but it is last in terms of the size of housing, measured as the average number of rooms per person: 1.1 in Romania compared to an average 1.6 rooms per person in the EU in 2022 [60]. Moreover, the overcrowding rate is also among the highest, reaching 41%. The size of the dwellings is also much smaller than in other EU countries, with less than 50 sqm/dwelling compared to the EU average of just above 100 sqm [101], hence an average floor area per capita of just 21 sqm [102]. This is mainly the result of the socialist ‘legacy’. Beginning with the late 1950s, the Romanian government issued laws that strictly regulated the standard areas for dwellings. The concept of standardized minimal dwelling was not exclusively communist. It was addressed in the 19th century by Western early industrialized countries, and later on, Weimar Germany established the 14 square meter minimum of living space [103] At the second International Congress of Modern Architecture that took place in Frankfurt in 1929, the question of the minimum dwelling was the top issue on the agenda [104,105,106]. The German concept of ‘Housing for Subsistence Living’ (Die Wohnung für das Existenzminimum) [105] was used to describe affordable housing with a minimum of quality, ensuring ‘a dignified and healthy existence’ [106,107]. However, in Romania, the average living area was established at only 8 and later on 10 sqm/person for all of the dwellings that were built. Not only were the dwellings built during the socialist period small, but also those built during the last three decades. Thus, the average area of an urban dwelling in Romania increased from 31 sqm in 1977 and 34.1 in 1992 to 48 in 2021. The average area of a dwelling in Bucharest was only 47 sqm (2021), similar to that in Iasi and Galati (around 45 sqm) but lower than those in Craiova and Timisoara (around 53 sqm). The dwellings from former hotel dormitories in Craiova have an average area of 21 sqm, which is undoubtedly small by most standards. However, the last decades have sparked debates and support for ‘condensed dwellings’ reduced to the bare minimum (a bed, a cooking appliance, a small toilet, and some storage) [104], found in global cities from Asia or North America as a result of rising rental prices and housing shortages. Apartments in some of these cities are much smaller than a dwelling in the analyzed former hostels for workers in Craiova, reaching only 10 sqm in Tokyo [104,105], not to mention the 2.4 sqm Haibu development in Paris and Barcelona [108]. Still, this does not mean that what micro-living proponents ‘reframe as an aspirational lifestyle choice’ is truly an innovative solution [108] or the only possible solution for the poorer citizens.

The hostels for young workers offered the smallest living space per person, with a bedroom of 20 sqm housing initially four or six young workers. In the 1990s and early 2000s, as the industrial units that owned and managed these buildings underwent major restructuring and privatization, these hostels faced a double problem. On one hand, many of the tenants were laid off, so unemployment and poverty surged. On the other hand, funds for the administration and maintenance of these buildings were scarce, so the buildings and technical infrastructure gradually decayed. Once these buildings were also privatized, the profile of the dwellers also changed. In most cases, these buildings were bought by private investors, who then rented and subsequently sold the rooms one by one. So, the owners of dwellings in these former workers’ dormitories, despite being among the poorest urban citizens, did not benefit from the ‘give-away’ privatization of the housing stock [63,109] as most of the urban dwellers in Romanian cities and former socialist countries did. Initially, whole families inhabited these rooms, and quite often, there were at least two generations living in the same room. Some of them were previous tenants of those rooms, others were new residents who could only afford such a place in the city. Throughout Romania, they were emblematic of precarious living conditions, since they featured all the traits of precarity/poverty: overcrowding, lack of amenities, decaying technical infrastructure, and degrading common areas [68]. The dormitories for young workers in Craiova were no exception to that rule. However, 30 years later, the situation has changed.

Severe overcrowding is no longer one of the main characteristics of these one-room units. The current study revealed a relatively high number of empty rooms (29.4%). A possible explanation may be related to the fact that the site investigation to collect data on the residents was conducted during the summer period. Many rooms are rented by students, as they are close to most of the facilities and have more affordable prices. While one-third of the occupied rooms accounted for one person, a significant number had two persons (19.5%). For only about 10% of these tiny rooms, we identified three, four, or more than four persons living in the same room. The highest number of persons was eight, but in a dwelling of 65 sqm, while other cases registered five or six persons living in a room of 21 sqm. However, these are only isolated instances. The results of the current paper support the findings of previous research [110], arguing that overcrowding has decreased in all housing types and especially in urban flats during the last two decades in Romania. This phenomenon is particularly more intense with respect to one-room units, as is the case with the former workers’ dormitories.

According to the Atlas of Urban Marginalized Areas in Romania, 2014 [82], which used data from the 2011 Population and Housing Census and municipal declarations, 1.76% of Craiova’s population resided in areas officially designated as “disadvantaged due to habitation conditions”, which includes areas where residents experience precarious living conditions, such as overcrowding, lack of infrastructure (e.g., absence of access to water or sewerage), or housing insecurity, all of which align with the conditions observed for communities residing in former dormitories, allowing for a comparative analysis of housing-related segregation. According to the findings of the current study, a decade later, approximately half of those living in historically documented marginalized housing conditions currently reside in these former workers’ dormitories. This validates the analytical choice to focus on this particular housing form as emblematic of urban segregation processes, particularly in post-socialist contexts where social housing reform has been slow or uneven, providing at the same time a complementary micro-level insight into urban segregation. Furthermore, the Atlas [82] supports the notion that these marginalized zones are not merely physical but also socially stigmatized spaces, highlighting that such areas are often associated with concentrated poverty, low formal education levels among adults, high school abandonment rates, and informal or insecure housing tenure. These characteristics closely mirror the conditions in the dormitories analyzed in the current study, reinforcing their relevance as indicators of socio-spatial exclusion.

Access to facilities and utilities is the prerequisite for a decent living. Throughout the entire city, the network of water pipes has been upgraded, and gas lines exist in all of the neighborhoods. However, only eight buildings are connected to the gas lines due to the high costs associated with initial work, as well as consumption. One of the most pressing issues is that of running water. Despite the fact that there is a proper infrastructure for a water supply and sewage system, there are instances when entire blocks of dwellings are still disconnected from the utilities due to major debts incurred by the residents. Even if initially, there were hardly rooms with their own bathroom or kitchenette, gradually, the owners managed to pay so as to extend the pipe network to each room and have a sort of individual running water and sewage system. But for some of them, the costs incurred were too high, and they could no longer pay. As the debts of the condominium accumulated month after month, they were finally disconnected. At the time we carried out our research, there were only two buildings that were no longer connected to the water supply from the city. Unlike other cases, the poor living conditions are not linked to a reduced access to key services like educational and health units, green urban areas or transportations (Figure 3) but to lack of access mainly to amenities and services like internet, current potable water and gas lines, although the rest of the surrounding buildings benefit from them.

Another issue related to these dwellings is affordability. While Romania ranks third among the EU countries regarding the affordability of owner-occupied housing (estimated as the number of average gross annual salaries required to pay for a standard new home with a floor area of 70 square meters) [111] and the fact that a dwelling in a former hostel for workers is the cheapest urban dwelling, the cost of living in the cities has been increasing steadily, including the price of utilities. Hence, access to affordable housing is quite problematic, especially for low-income people. It comes as no surprise that there are many instances when residents can no longer pay the costs associated with utilities. The share of individuals with rent or utility arrears is one of the indicators related to affordability [6], with arrears on utility bills being a manifestation of financial hardship and the deterioration of living conditions [112]. Except for one building, all the hostels featured between 10 and 25% of the tenants who had considerable utility arrears, exceeding at least a year’s worth of accumulated debt. While gas and electricity providers can and do proceed to disconnect each household when beneficiaries no longer pay, water shut-offs are a completely different story. There are no individual contracts for water supply. The contract is made between the water company and the condominium, so there is no possibility for individual disconnection. When the debts to the water company become staggering, residents are urged to pay. In September 2024, for instance, one of the condominiums in Craiova was summoned to pay a debt totaling EUR 135,000 that covered a 4-year period to the water company.

This study acknowledges several limitations that influence the scope and accuracy of its findings. One major constraint lies in the availability of socioeconomic data, as the absence of detailed information on household income, employment status, and educational attainment restricts the ability to establish direct correlations between economic factors and segregation patterns. Unlike studies conducted in Western contexts, where comprehensive census data are readily accessible [113], demographic and economic data in Craiova remain fragmented, presenting a challenge to quantifying the relationship between economic marginalization and residential segregation. The geographical boundaries chosen for analysis also present limitations, as the administrative boundaries of neighborhoods used as the units of measurement may not fully capture the micro-scale manifestations of segregation. Since spatial divisions can emerge at finer resolutions, future research could employ more detailed, neighborhood-level or vertical segregation analyses to enhance precision in measuring socio-spatial disparities.

Additionally, the study provides a static representation of segregation patterns in 2024, limiting its ability to account for dynamic urban transformations. The absence of longitudinal data makes it difficult to assess whether spatial divisions are deepening or whether urban policies are fostering greater integration over time. A more comprehensive understanding would require comparative assessments over multiple time periods to capture the evolution of segregation processes. Furthermore, while qualitative data are integrated to contextualize the numerical indices, the study does not include extensive resident interviews or ethnographic fieldwork. The exclusion of firsthand narratives limits insight into the lived experiences of segregation, particularly in terms of perceived access to services, social mobility, and neighborhood interactions.

While the current research presents a static analysis for 2024, the incorporation of the data provided by a previous national study [82] enables a rudimentary temporal dimension by illustrating continuity in patterns of spatial segregation over at least a decade. However, a comprehensive longitudinal analysis would require harmonized data from multiple census periods—data which remains largely inaccessible in Romania. Therefore, future research should aim to leverage administrative archives, municipal housing records, or participatory mapping initiatives to reconstruct the evolution of urban segregation more robustly.

Despite these limitations, the study introduces several novel contributions to the field of urban segregation research. By integrating historical analysis with contemporary spatial mapping techniques, it advances the understanding of how past urban planning decisions continue to shape present-day socio-spatial inequalities. This approach distinguishes it from conventional studies that primarily focus on statistical segregation metrics [11,15], offering a more comprehensive perspective on the persistence of spatial divisions. The application of segregation indices to a post-socialist secondary city also enhances the existing body of literature, which has predominantly focused on large metropolitan areas. While urban segregation has been extensively examined in cities such as Berlin, London, and New York, fewer studies have explored its dynamics in mid-sized Eastern European cities undergoing post-industrial transitions. The current focus on residents of former social dormitories does not negate the broader landscape of urban segregation in Craiova but highlights a specific and representative segment within it. Their share cannot be overlooked when placed into historical context and reinforces the importance of analyzing how inherited urban forms perpetuate inequality. By demonstrating how classical segregation indices can be effectively employed in this context, the study validates their applicability in urban environments, where economic transformation occurs at a slower pace.

Another significant contribution lies in its focus on the spatial distribution of former industrial worker housing, a group often overlooked in contemporary segregation debates. While much of the existing research has centered on ethnic and racial segregation, this study highlights the long-term effects of socialist-era housing policies on socio-spatial exclusion. The persistence of segregated worker housing in Craiova underscores how spatial marginalization can endure beyond periods of direct state intervention, aligning with the findings from other post-socialist cities while introducing regionally specific insights. The use of GIS-based mapping further enhances the methodological approach, allowing for a data-driven visualization of housing disparities. By employing a combination of statistical indices and spatial analysis, this study provides a replicable model for assessing residential segregation in similar urban contexts, contributing to the development of more inclusive housing policies.

6. Conclusions

The hostels for young workers, often dilapidated, present clearly different living conditions compared to the new residential complexes built after 2010 [58] or any other residential areas. Some of these buildings lack access to permanent running water due to high debts, are not connected to gas lines, internet providers refuse the connection, or lack any recreational facilities.

Residential segregation in Craiova can be attributed to multiple causes, including historical legacies of industrial development, economic disparities, and post-socialist urban restructuring. During the communist era, housing was provided based on employment in industrial sectors, creating worker enclaves. After 1990, economic liberalization and privatization led to uneven development, with newer residential complexes, some of which were built on former industrial sites and owned by wealthier segments of the population. In contrast, many of the older industrial apartments remain occupied by lower-income groups, creating distinct socio-economic divisions.

The consequences of residential segregation are far-reaching, affecting mainly quality of life and social cohesion, but not access to urban services. In Craiova, inhabitants of the former hostels, with overcrowded dwellings, often face poor living conditions, with limited access to running water and gas, and having common-use spaces like toilets, showers, and kitchens. Most of these residents are students or people with low employment opportunities, with missing or incomplete education, while residents of newer complexes benefit from better infrastructure and amenities (playgrounds, underground parking, and entrance barriers for increased safety). This spatial divide exacerbates socio-economic inequalities and limits upward mobility for lower-income groups, reinforcing cycles of poverty.

Globally, policy interventions aimed at reducing residential segregation include affordable housing programs, urban regeneration projects, and inclusive zoning policies. In Craiova, potential interventions could focus on improving the living conditions in residential segregated areas through renovation programs, increasing access to services in disfavored buildings, and promoting mixed-income housing developments to encourage more socio-spatial integration.

Author Contributions

Both authors contributed equally to this paper. Conceptualization, Cristiana Vîlcea and Liliana Popescu; methodology, Cristiana Vîlcea and Liliana Popescu; formal analysis, Cristiana Vîlcea and Liliana Popescu; investigation, Cristiana Vîlcea and Liliana Popescu; data curation, Cristiana Vîlcea; writing—original draft preparation, Cristiana Vîlcea and Liliana Popescu; writing—review and editing, Cristiana Vîlcea and Liliana Popescu. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- EUROSTAT. Digitalisation in Europe. Eurostat. 2023. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/interactive-publications/digitalisation-2023 (accessed on 12 July 2024).

- Hotnews. Românii și visul european de a avea o casă. Surprinzătoarea vârstă la care reușim noi să fim proprietari—HotNews.ro. HotNews. 2023. Available online: https://hotnews.ro/romnii-si-visul-european-de-a-avea-o-casa-surprinzatoarea-vrsta-la-care-reusim-noi-sa-fim-proprietari-68752 (accessed on 15 October 2024).

- Vincze, E. Ghettoization: The Production of Marginal Spaces of Housing and the Reproduction of Racialized Labour. In Racialized Labour in Romania; Palgrave Macmillan: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 63–95. [Google Scholar]

- OHCHR Universal Declaration of Human Rights. 1949. Available online: https://www.ohchr.org/en/human-rights/universal-declaration/translations/english (accessed on 15 October 2024).

- Vincze, E.; Hossu, I.-E.; Bădiță, C. Incomplete Housing Justice in Romania under Neoliberal Rule. Justice Spatiale Spat Justice 2019, 10, 1–32. [Google Scholar]

- Russell, H.; Privalko, I.; McGinnity, F.; Enright, S. Monitoring Adequate Housing in Ireland; ESRI and Irish Human Rights and Equality Commission (IHREC): Dublin, Ireland, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN-HABITAT. The Human Right to Adequate Housing; UN-HABITAT: Geneva, Switzerland, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Council of Europe. The (Revised) European Social Charter. 1996. Available online: https://www.coe.int/en/web/european-social-charter (accessed on 15 October 2024).

- OECD. How’s Life? 2020: Measuring Well-Being; OECD: Paris, France, 2020; Available online: https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/how-s-life/volume-/issue-_9870c393-en/full-report.html (accessed on 15 October 2024).

- Vaughan, L.; Arbaci, S. The Challenges of Understanding Urban Segregation. Built Environ. 2011, 37, 128–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musterd, S.; Ostendorf, W.J.M. Urban Segregation and the Welfare State: Inequality and Exclusion in Western Cities; Taylor and Francis: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Musterd, S.; Marcińczak, S.; Van Ham, M.; Tammaru, T. Socioeconomic segregation in European capital cities. Increasing separation between poor and rich. Urban. Geogr. 2017, 38, 1062–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tammaru, T. Socio-Economic Segregation in European Capital Cities: East Meets West; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2019; Available online: https://www.routledge.com/Socio-Economic-Segregation-in-European-Capital-Cities-East-meets-West/Tammaru-Marcinczak-vanHam-Musterd/p/book/9780367870201 (accessed on 2 March 2025).

- Van Ham, M.; Marcińczak, S.; Tammaru, T.; Musterd, S. A multi-factor approach to understanding socio-economic segregation in European capital cities. In Socio-Economic Segregation in European Capital Cities; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 1–29. [Google Scholar]

- Massey, D.S.; Denton, N.A. The Dimensions of Residential Segregation. Soc. Forces 1988, 67, 281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elbers, B. Trends in U.S. Residential Racial Segregation, 1990 to 2020. Socius Sociol. Res. Dyn. World 2021, 7, 23780231211053982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feitosa, F.F.; Câmara, G.; Monteiro, A.M.V.; Koschitzki, T.; dos Santos Silva, M.P. Spatial Measurement of Residential Segregation. In Proceedings of the VI Brazilian Symposium on Geoinformatics, Campos do Jordão, São Paulo, Brazil, 22–24 November 2004; pp. 59–74. [Google Scholar]

- Barros, J.; Feitosa, F.F. Uneven geographies: Exploring the sensitivity of spatial indices of residential segregation. Environ. Plan. B Urban. Anal. City Sci. 2018, 45, 1073–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oka, M.; Wong, D.W.S. Capturing the Two Dimensions of Residential Segregation at the Neighborhood Level for Health Research. Front. Public Health 2014, 2, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Royuela, V.; Vargas, M. Residential Segregation: A Literature Review; Universidad Diego Portales: Santiago, Chile, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Ross, N.A.; Houle, C.; Dunn, J.R.; Aye, M. Dimensions and dynamics of residential segregation by income in urban Canada, 1991–1996. Can. Geogr. Géographies Can. 2004, 48, 433–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, X.; Wang, Y.; Li, W.; Wu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Ma, Z. Research Progress and Trends in Urban Residential Segregation. Buildings 2024, 14, 1962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, R. Residential Segregation and Class Formation in the Capitalist City: A Review and Directions for Research. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 1984, 8, 26–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tammaru, T.; Marcińczak, S.; Ham, M.; UvA-DARE (Digital Academic Repository). Inequality and rising levels of socio-economic segregation: Lessons from a pan-European comparative study. In Socio-Economic Segregation in European Capital Cities: East Meets West; Taylor & Francis: Abingdon, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Stephens, M.; Lux, M.; Sunega, P. Post-Socialist Housing Systems in Europe: Housing Welfare Regimes by Default? Hous. Stud. 2015, 30, 1210–1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, B.; Franco, J. HOLC “Redlining” Maps: The Persistent Structure of Segregation and Economic Inequality; National Community Reinvestment Coalition: Washington, DC, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Nightingale, C.H. Segregation: A Global History of Divided Cities; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2012; Available online: https://books.google.com/books/about/Segregation.html?hl=ro&id=EMq4RbJHCJ0C (accessed on 29 April 2025).

- Cutler, D.M.; Glaeser, E.L.; Vigdor, J.L. The Rise and Decline of the American Ghetto. J. Polit. Econ. 1999, 107, 455–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iceland, J.; Weinberg, D.H.; Steinmetz, E. Racial and Ethnic Residential Segregation in the United States: 1980–2000; U.S. Government Printing Office: Washington, DC, USA, 2002.

- Duncan, O.D.; Duncan, B. A Methodological Analysis of Segregation Indexes. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1955, 20, 210–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egan, K.L.; Anderton, D.L.; Weber, E. Relative Spatial Concentration among Minorities: Addressing Errors in Measurement. Soc. Forces 1998, 76, 1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folch, D.C.; Rey, S.J. The centralization index: A measure of local spatial segregation*. Pap. Reg. Sci. 2016, 95, 555–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massey, D.S.; White, M.J.; Phua, V.-C. The Dimensions of Segregation Revisited. Sociol. Methods Res. 1996, 25, 172–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovács, Z. New post-socialist urban landscapes: The emergence of gated communities in East Central Europe. Cities 2014, 36, 179–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcińczak, S. The evolution of spatial patterns of residential segregation in Central European Cities: The Łódź Functional Urban Region from mature socialism to mature post-socialism. Cities 2012, 29, 300–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spevec, D.; Bogadi, S.K. Croatian Cities Under Transformation: New Tendencies in Housing and Segregation. Tijdschr. Voor Econ. En. Soc. Geogr. 2009, 100, 454–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcińczak, S.; Hess, D.B. Chapter 12: Vertical separation in high-rise apartment buildings: Evidence from Bucharest and Budapest under state socialism. In Vertical Cities; Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2022; pp. 173–188. [Google Scholar]

- Marcińczak, S.; Gentile, M.; Rufat, S.; Chelcea, L. Urban Geographies of Hesitant Transition: Tracing Socioeconomic Segregation in Post-Ceauşescu Bucharest. Int. J. Urban. Reg. Res. 2014, 38, 1399–1417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gentile, M.; Marcińczak, S. Housing inequalities in Bucharest: Shallow changes in hesitant transition. GeoJournal 2014, 79, 449–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcińczak, S.; Hess, D.B. Vertical segregation of apartment building dwellers during late state socialism in Bucharest, Romania. Urban. Geogr. 2020, 41, 823–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creţan, R.; Tuţă, A.; Dragan, A. Towards a more inclusive perception of a territorially stigmatized area? Evidence from an East-Central European city. Cities 2025, 158, 105658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creţan, R.; Kupka, P.; Powell, R.; Walach, V. EVERYDAY ROMA STIGMATIZATION: Racialized Urban Encounters, Collective Histories and Fragmented Habitus. Int. J. Urban. Reg. Res. 2022, 46, 82–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mereine-Berki, B.; Málovics, G.; Creţan, R. “You become one with the place”: Social mixing, social capital, and the lived experience of urban desegregation in the Roma community. Cities 2021, 117, 103302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Málovics, G.; Creţan, R.; Berki, B.M.; Tóth, J. Urban Roma, segregation and place attachment in Szeged, Hungary. Area 2019, 51, 72–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conway, F.; Katsura, H.; Budisteanu, I.; Pascal, I. The Transition to a Market-BAsed Housing Sector in Romania; The Urban Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, A.; Buckley, R.M.; Budovitch, M.M.; Luca, O.; Manchanda, S.; Martin, R.; Batog, M.R.; Rai, M.; Manjusha, D.; Walley, S.C. Housing in Romania: Towards a National Housing Strategy (Vol. 2): Harmonizing Public Investments; Pdf Final Report; The World Development Bank: Bucharest, Romania, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Zahariade, A.M. Architecture in the Communist Project; Simetria: Bucharest, Romania, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Stănescu, I. Quality of Life in Romania 1918–2018: An Overview. Calitatea Vieții 2018, 29, 107–144. [Google Scholar]

- Serban, M. The Exceptionalism of Housing in the Ideology and Politics of Early Communist Romania (1945–1965). Eur-Asia Stud. 2015, 67, 443–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Răuţă, R.-A.; Heynen, H. Shifting meanings of modernism: Parallels and contrasts between Karel Teige and Cezar Lăzărescu. J. Archit. 2009, 14, 27–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maxim, J. Mass housing and collective experience: On the notion of microraion in Romania in the 1950s and 1960s. J. Archit. 2009, 14, 7–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marea Adunare Nationala. Decree No. 78 from 05/04/1952. Official Bulletin 17. Available online: https://legislatie.just.ro/Public/DetaliiDocument/20001 (accessed on 10 October 2024).

- Mărginean, M. From Printed Word to Bureaucratic Negotiation. Housing Projects for Workers during the 1950s in Romania. Stud. Hist. Theory Archit. 2013, 1, 120–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reid, S.E. Communist Comfort: Socialist Modernism and the Making of Cosy Homes in the Khrushchev Era. Gend. Hist. 2009, 21, 465–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Culiciu, C. Urbanismul în era ‘de stat’: Sistematizarea Oradiei în comunism; Muzeul Tarii Crisurilor: Oradea, Romania, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Ivan, R. ‘Transformarea Socialistă’: Politici ale Regimului Comunist între Ideologie și Administrație; Polirom: Bucharest, Romania, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Alpopi, C.; Iacoboaea, C.; Stănescu, A. Analysis of the Current Housing Situation in Romania in the European Context. Transylv. Rev. Adm. Sci. 2014, 10, 5–24. [Google Scholar]

- Voiculescu, S.; Creţan, R.; Ianăș, A.-N.; Satmari, A. The Romanian Post-Socialist City: Urban Renewal and Gentrification; Editura Universității de Vest: Timisoara, Romania, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Soaita, A.M. Overcrowding and ‘Underoccupancy’ in Romania: A Case Study of Housing Inequality. Environ. Plan. A 2014, 46, 203–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eurostat. Housing in Europe; European Comission: Brusells, Belgium, 2023; Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/interactive-publications/housing-2023#size-of-housing (accessed on 9 October 2024).

- Iacoboaea, C. Slums in Romania. Theor. Empir. Res. Urban. Manag. 2009, 1, 101–113. [Google Scholar]

- Pitulac, T. Continuum-ul comunism—Post comunism. România urbana in secolul al XXI-lea. Sfera Polit. 2013, 21, 125–134. [Google Scholar]

- Turcu, C. Mind the Poorest: Social Housing Provision in Post-crisis Romania. Crit. Hous. Anal. 2017, 4, 54–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vincze, E. Residualized Public Housing in Romania: Peripheralization of ‘the Social’ and the Racialization of ‘Unhouseables’. Int. J. Urban. Reg. Res. 2024, 48, 403–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Council of Ministers. Decree No. 585/1971 on Building Urban Covered by the Centralized Government Funds. 1971. Available online: https://lege5.ro/gratuit/gyydcnju/hotararea-nr-585-1971-privind-construirea-de-locuinte-de-tip-urban-din-fondurile-de-stat-centralizate (accessed on 28 February 2025).

- National Statistics Institute. Population and Households Census. 1992. Available online: https://www.recensamantromania.ro/rezultate-recensamant-1992/ (accessed on 28 February 2025).

- Florea, I.; Dumitriu, M. Living on the Edge: The Ambiguities of Squatting and Urban Development in Bucharest. In Public Goods versus Economic Interests; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 188–210. [Google Scholar]

- Niţulescu, D.C.; Constantinescu, M.; Bajenaru, C. Areas of precarious dwelling conditions in România—A general analysis. Calitatea Vieţii 2005, XVI, 65–85. [Google Scholar]

- Botonogu, F. Comunitati Ascunse: Aleea Livezilor Ferentari; Editura Expert: Bucharest, Romania, 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vincze, E. The making of a racialized surplus population. Focaal—J. Glob. Hist. Anthropol. 2023, 97, 63–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cătună, V. Locuire colectivă şi solidaritate în zonele de tip “ghetou”. Cămine din aleea Nehoiu. In Collective Living and Solidarity in the Areas of “Ghetto”. Hostels in Nehoiu Alley/ De la Stradă la Ansambluri Rezidenţiale. Opt Ipostaze ale Locuirii în Bucureştiul Contemporan; Pro Universitaria: Bucharest, Romania, 2016. [Google Scholar]