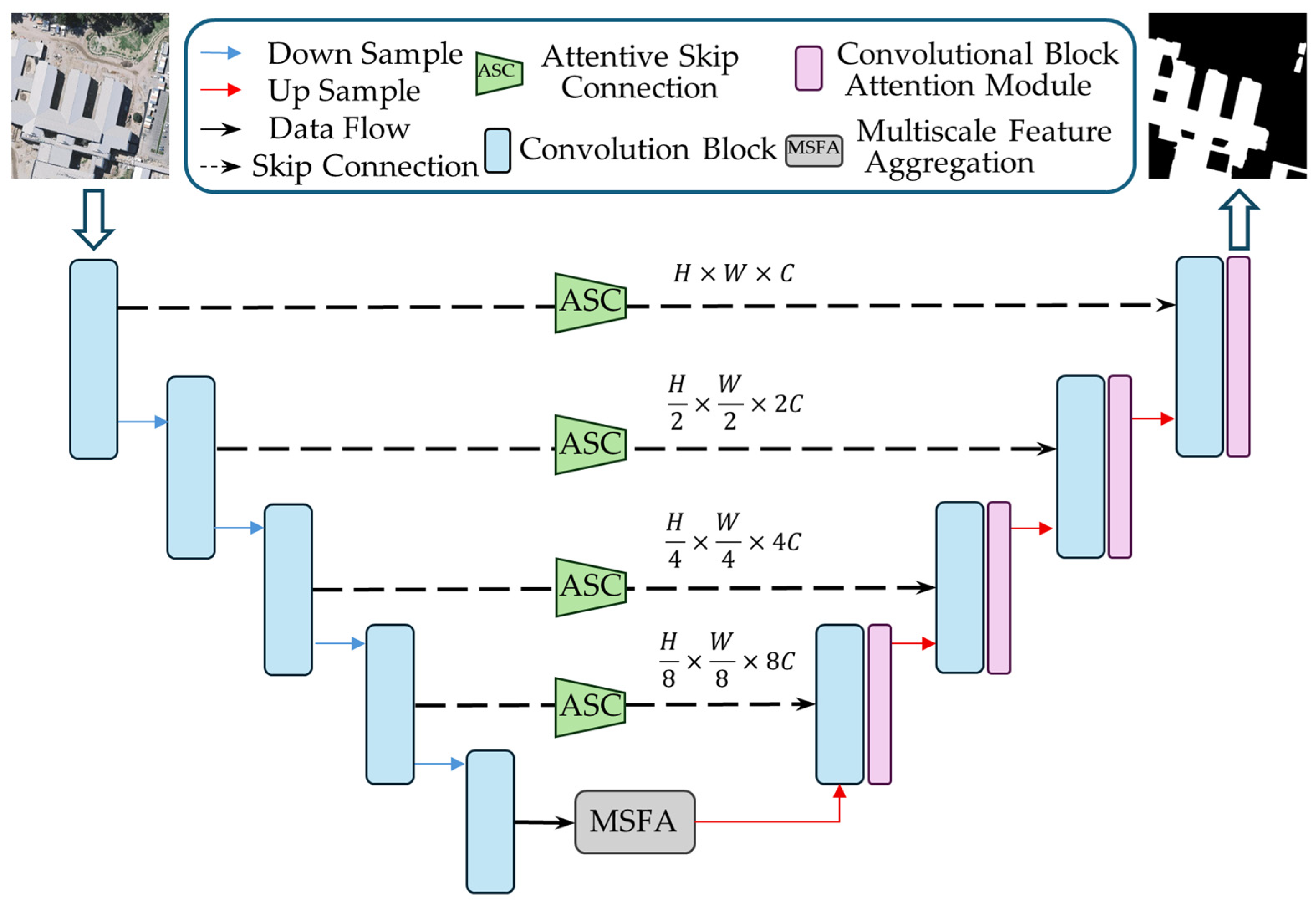

MSA-UNet: Multiscale Feature Aggregation with Attentive Skip Connections for Precise Building Extraction

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

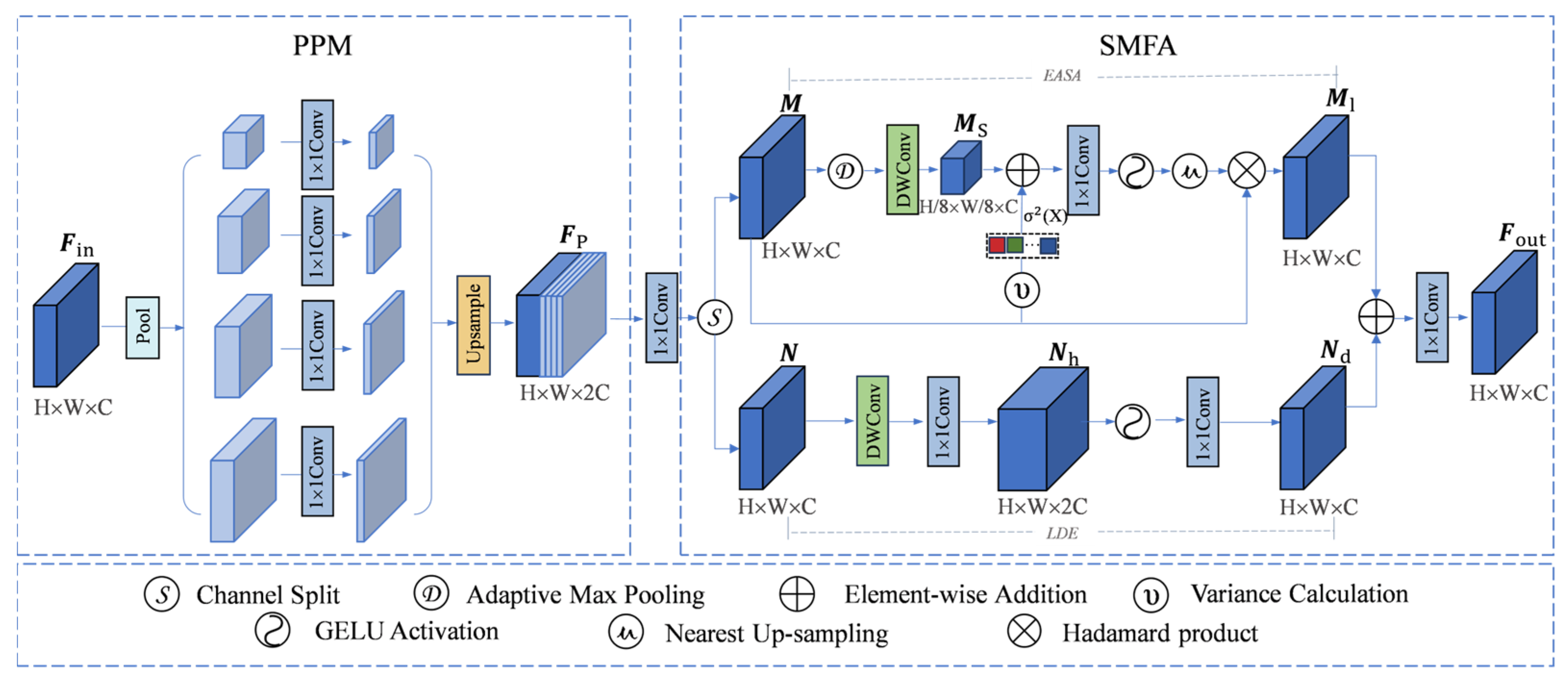

- We design a multiscale feature aggregation (MSFA) module that jointly captures local and nonlocal information and aggregates multiscale context, thereby enhancing high-level feature representation.

- (2)

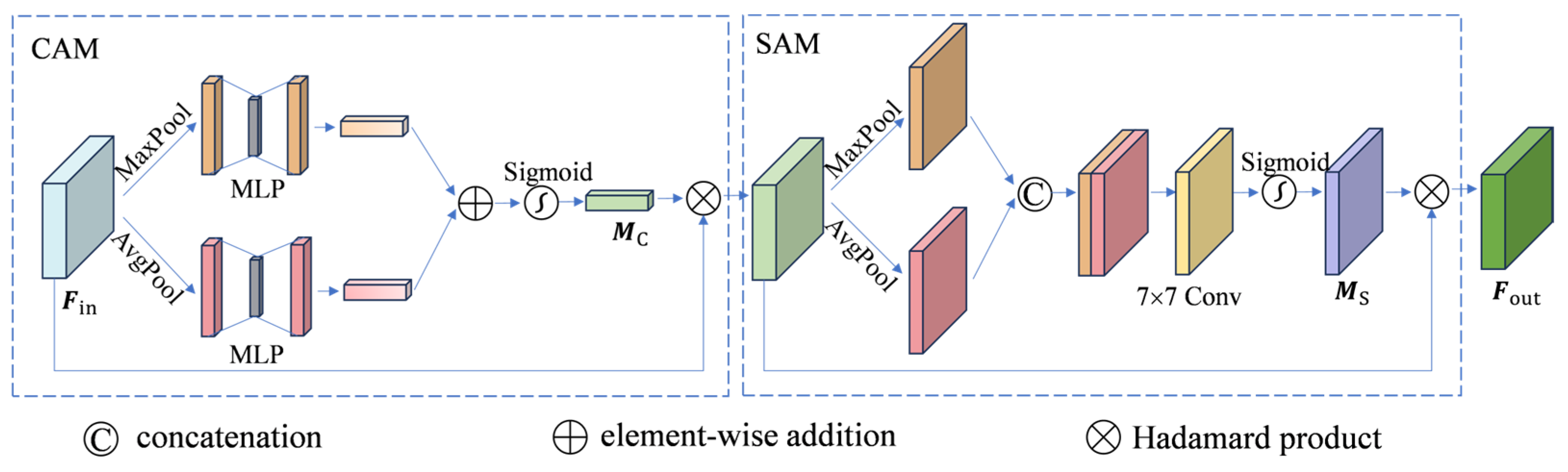

- We integrate a convolutional block attention module (CBAM) into the decoder to adaptively reweight spatial locations and channels, thereby suppressing noise from irrelevant background regions and improving the response to building regions.

- (3)

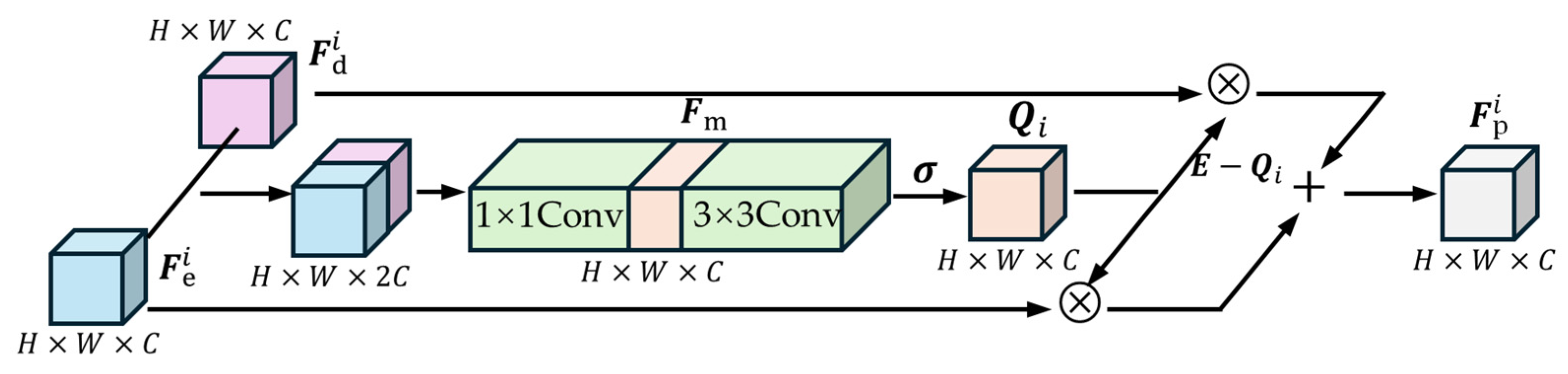

- We design an attentive skip connection (ASC) to dynamically emphasize salient features by computing attention-based correlations between encoder and decoder features, which strengthens multi-level feature fusion and refines building boundaries.

2. Methodology

2.1. MSFA Module

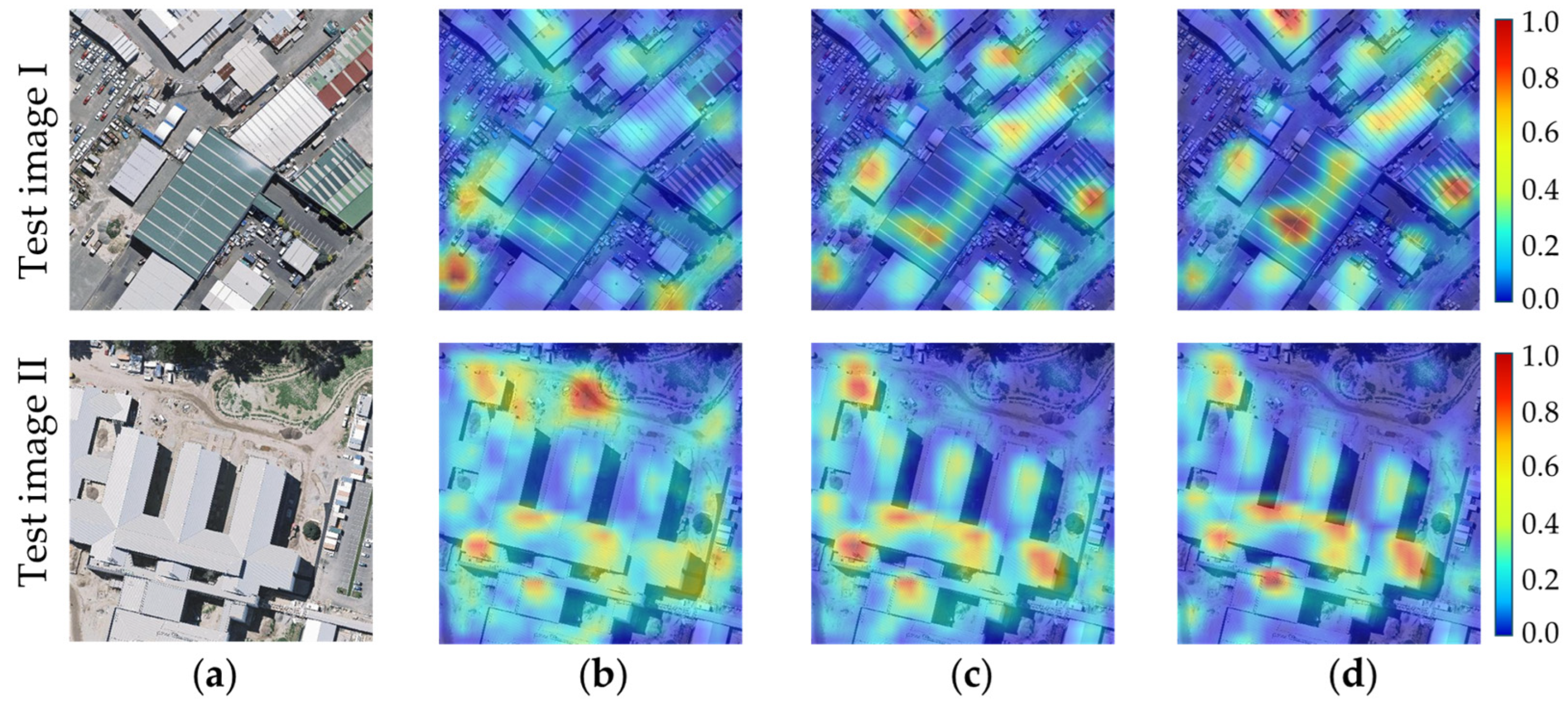

2.2. Attention-Enhanced Feature Refinement

2.3. ASC Module

2.4. Joint Loss Function

3. Experimental Setup and Evaluation

3.1. Experimental Data

3.2. Experimental Details and Environment Settings

3.3. Evaluation Metrics

4. Experimental Results and Analysis

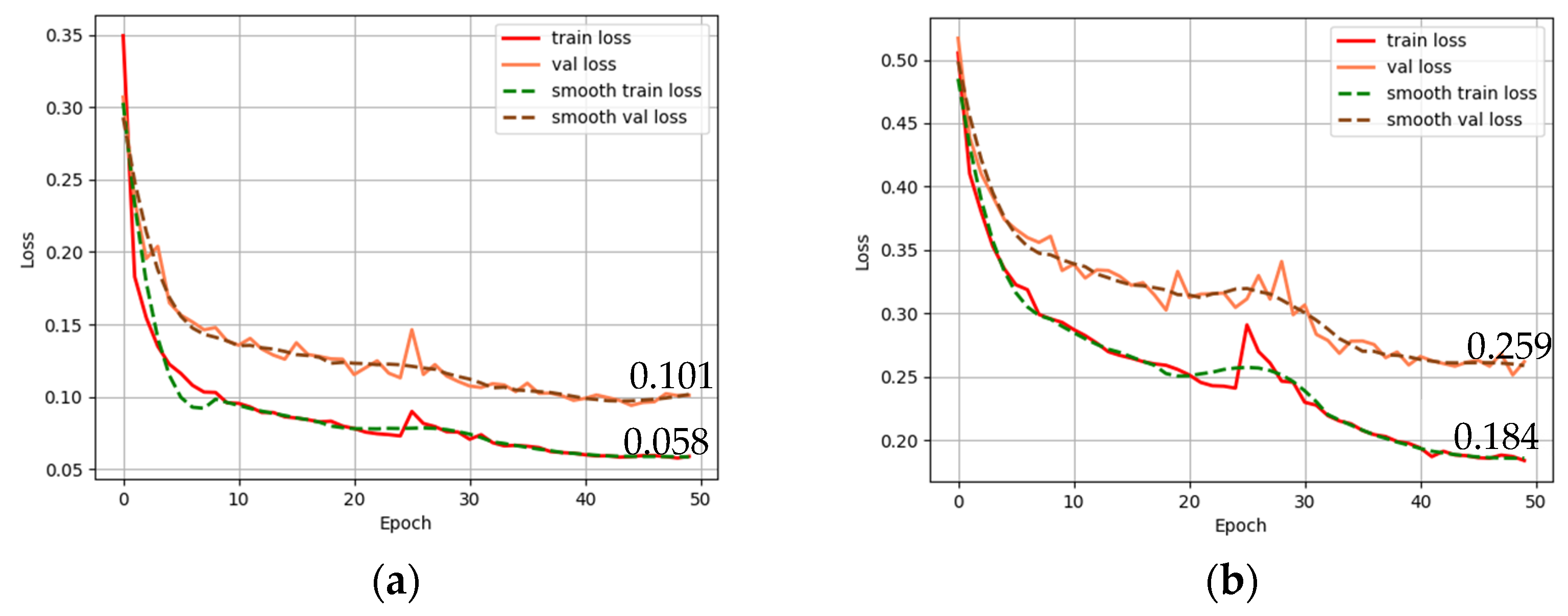

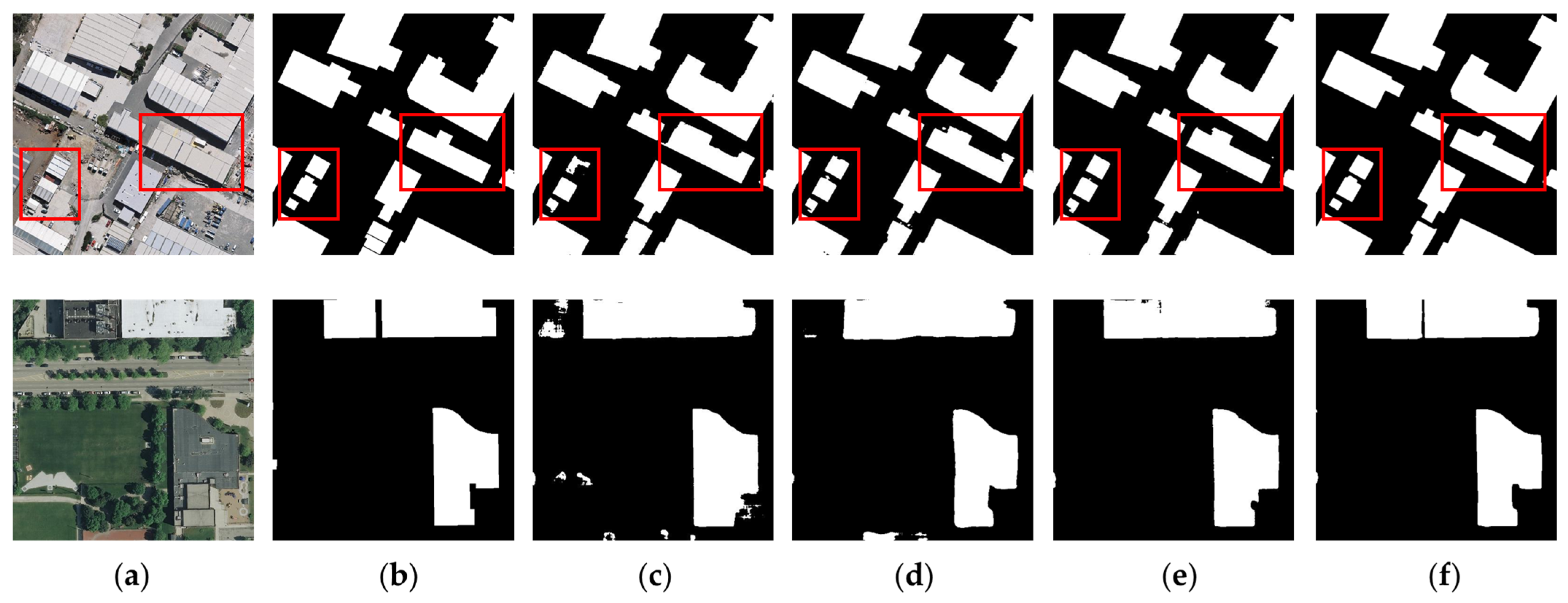

4.1. Ablation Study

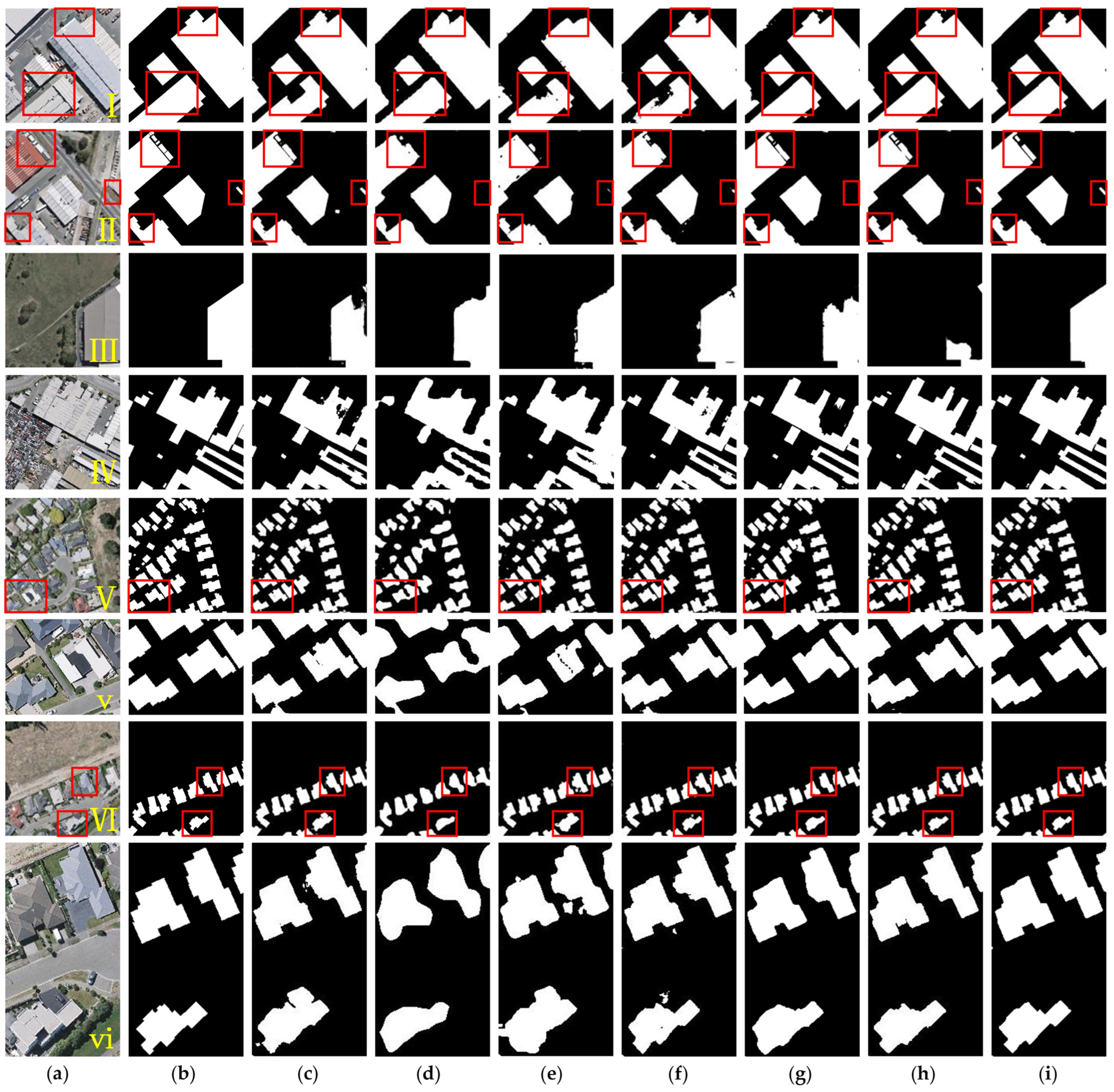

4.2. Comparative Experiments and Analysis

4.2.1. WHU Dataset Results and Analysis

4.2.2. Inria Dataset Results and Analysis

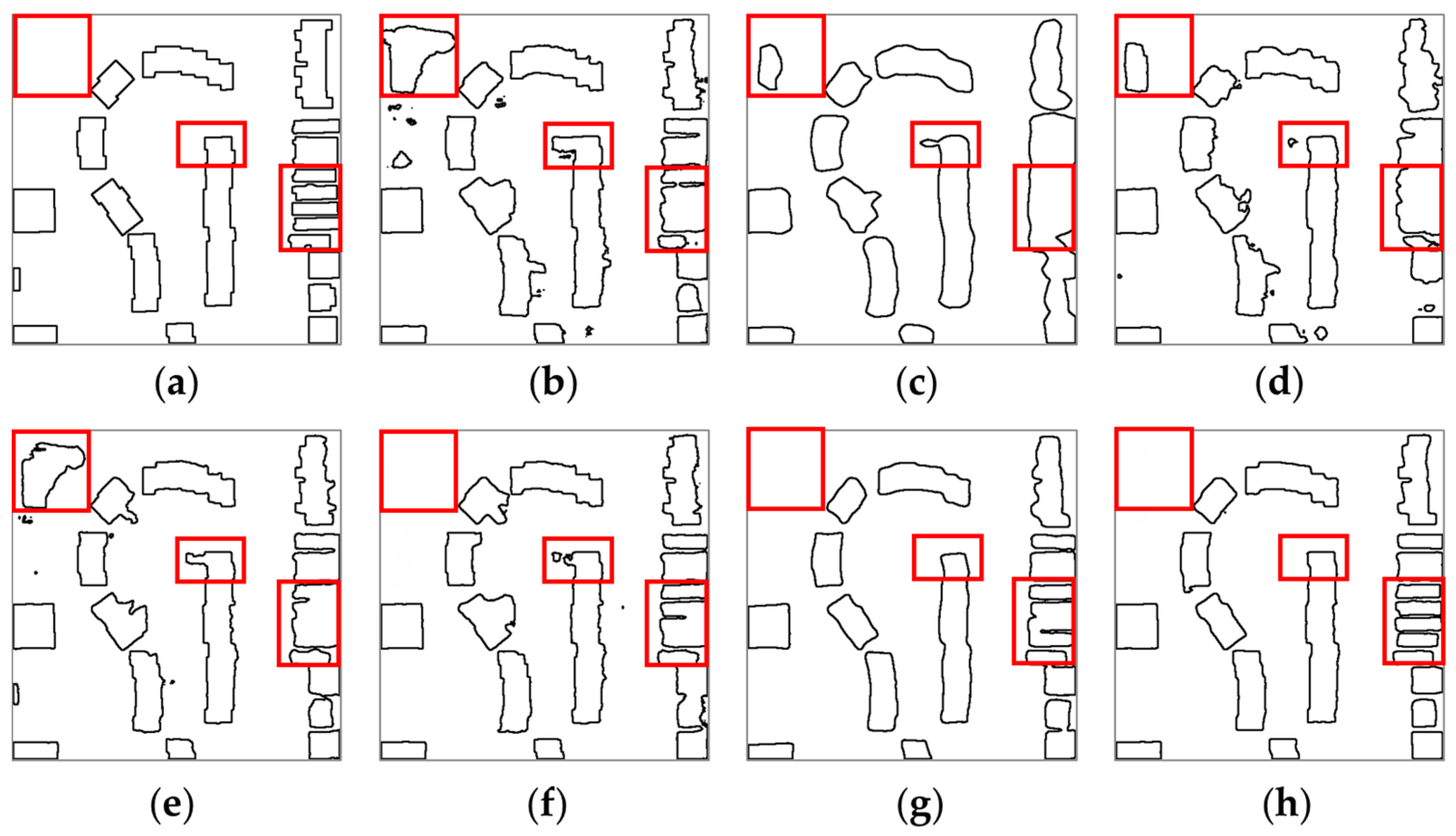

4.2.3. Accuracy Analysis of Building Boundary Extraction

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yang, D.; Gao, X.; Yang, Y.; Guo, K.; Han, K.; Xu, L. Advances and future prospects in building extraction from high-resolution remote sensing images. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2025, 18, 6994–7016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Zhang, L. Photogrammetric engineering & remote sensing. Photogramm. Eng. Remote Sens. 2011, 77, 721–732. [Google Scholar]

- Turker, M.; Koc-San, D. Building extraction from high-resolution optical spaceborne images using the integration of support vector machine (SVM) classification, Hough transformation and perceptual grouping. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2015, 34, 58–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Roffey, M.; Leblanc, S.G. A novel framework for rapid detection of damaged buildings using pre-event LiDAR data and shadow change information. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 3297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, S.; Lee, K.; Lee, W.H. Object-based high-rise building detection using morphological building index and digital map. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Liu, B.; Xu, K. Semantic segmentation of high-resolution images. Sci. China Inf. Sci. 2017, 60, 123101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shelhamer, E.; Long, J.; Darrell, T. Fully convolutional networks for semantic segmentation. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2017, 39, 640–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronneberger, O.; Fischer, P.; Brox, T. U-Net: Convolutional networks for biomedical image segmentation. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention (MICCAI 2015), Munich, Germany, 5–9 October 2015; pp. 234–241. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, H.; Shi, J.; Qi, X.; Wang, X.; Jia, J. Pyramid scene parsing network. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017; pp. 6230–6239. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, L.-C.; Papandreou, G.; Schroff, F.; Adam, H. Rethinking atrous convolution for semantic image segmentation. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1706.05587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.-C.; Papandreou, G.; Kokkinos, I.; Murphy, K.; Yuille, A.L. DeepLab: Semantic image segmentation with deep convolutional nets, atrous convolution, and fully connected CRFs. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2018, 40, 834–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.-C.; Zhu, Y.; Papandreou, G.; Schroff, F.; Adam, H. Encoder-decoder with atrous separable convolution for semantic image segmentation. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), Munich, Germany, 8–14 September 2018; pp. 833–848. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, H.; Wang, Y.; Chen, J.; Jiang, D.; Zhang, X.; Tian, Q.; Wang, M. Swin-Unet: Unet-like pure transformer for medical image segmentation. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), Tel Aviv, Israel, 23–27 October 2022; pp. 205–218. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, E.; Wang, W.; Yu, Z.; Anandkumar, A.; Alvarez, J.M.; Luo, P. SegFormer: Simple and efficient design for semantic segmentation with transformers. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2105.15203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Zou, Z.; Shi, Z. Building extraction from remote sensing images with sparse token transformers. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 4441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Wan, Z.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, G. DSAT-Net: Dual spatial attention transformer for building extraction from aerial images. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2023, 20, 6008405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, L.; Mi, S.; Zhang, J.; Luo, J.; Shen, Z.; Cheng, Y. Dual-stream feature extraction network based on CNN and transformer for building extraction. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 2689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oktay, O.; Schlemper, J.; Le Folgoc, L.; Lee, M.; Heinrich, M.; Misawa, K.; Mori, K.; McDonagh, S.; Hammerla, N.Y.; Kainz, B.; et al. Attention U-Net: Learning where to look for the pancreas. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1804.03999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Z.; Fu, Y.; Gan, M.; Deng, J.; Comber, A.; Wang, K. Building extraction from very high resolution aerial imagery using joint attention deep neural network. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 2970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.; Hao, M.; Luo, W.; Yu, H.; Zheng, N. BEARNet: A novel buildings edge-aware refined network for building extraction from high-resolution remote sensing images. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2023, 20, 6005305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, H.; Liu, K.; Wang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Huang, C.; Wang, P.; Li, L. MAD-UNet: A multi-region UAV remote sensing network for rural building extraction. Sensors 2024, 24, 2393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.; Bian, L.; Hu, W.; Li, J.; Ni, H.; Huang, X. DSNet: A novel way to use atrous convolutions in semantic segmentation. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 2025, 35, 3679–3692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, B.; Shao, W.; Shao, P.; Wang, J.; Xiong, J.; Qi, C. DHI-Net: A novel detail-preserving and hierarchical interaction network for building extraction. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2024, 21, 2504605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simonyan, K.; Zisserman, A. Very deep convolutional networks for large-scale image recognition. arXiv 2014, arXiv:1409.1556. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, M.; Sun, L.; Dong, J.; Pan, J. SMFANet: A lightweight self-modulation feature aggregation network for efficient image super-resolution. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), Milan, Italy, 29 September–4 October 2024; pp. 321–338. [Google Scholar]

- Woo, S.; Park, J.; Lee, J.Y.; Kweon, I.S. CBAM: Convolutional block attention module. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), Munich, Germany, 8–14 September 2018; pp. 3–19. [Google Scholar]

- Ji, S.; Wei, S.; Lu, M. Fully convolutional networks for multisource building extraction from an open aerial and satellite imagery data set. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2019, 57, 574–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maggiori, E.; Tarabalka, Y.; Charpiat, G.; Alliez, P. Can semantic labeling methods generalize to any city? The INRIA aerial image labeling benchmark. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium (IGARSS), Fort Worth, TX, USA, 23–28 July 2017; pp. 3226–3229. [Google Scholar]

| Component | Original U-Net | MSA-UNet |

|---|---|---|

| Encoder | Stacked simple convolutional blocks | Pretrained VGG16 as backbone encoder |

| Multiscale Feature Fusion | Not included | PPM (pyramid pooling module) + SMFA (self-modulation feature aggregation) |

| Decoder | Transposed convolution for upsampling | Bilinear interpolation with dual-attention modules for dependency modeling |

| Skip Connections | Direct concatenation of encoder–decoder features | Attentive skip connections (ASC) for adaptive feature fusion |

| Dataset | Modules | mIoU/% | Acc/% | F1/% | mPA/% | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MSFA | CBAM | ASC | |||||

| WHU | 92.85 | 97.70 | 95.70 | 96.36 | |||

| ✓ | 93.56 | 97.95 | 96.12 | 96.45 | |||

| ✓ | ✓ | 94.00 | 98.10 | 96.31 | 96.66 | ||

| ✓ | ✓ | 93.67 | 97.99 | 96.30 | 96.54 | ||

| ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 94.26 | 98.32 | 96.57 | 96.85 | |

| Inria | 84.05 | 94.28 | 89.93 | 90.65 | |||

| ✓ | 85.39 | 94.75 | 91.31 | 91.99 | |||

| ✓ | ✓ | 85.77 | 95.04 | 91.40 | 92.14 | ||

| ✓ | ✓ | 85.21 | 94.66 | 91.00 | 92.05 | ||

| ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 85.92 | 95.24 | 91.50 | 92.26 | |

| Model | Params/M | FLOPs/G |

|---|---|---|

| Baseline UNet | 24.90 | 92.04 |

| Baseline + MSFA | 27.79 | 97.43 |

| Baseline + MSFA + CBAM | 27.92 | 98.50 |

| Baseline + MSFA + CBAM + ASC (MSA-UNet) | 28.44 | 102.05 |

| Model | mIoU/% | Accuracy/% | F1/% | mPA/% | Params/M | Runtime/(min/epoch) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| U-Net | 92.85 | 97.70 | 95.70 | 96.36 | 24.90 | 3.42 |

| PSPNet | 89.12 | 96.46 | 93.42 | 93.54 | 49.07 | 4.78 |

| DeepLabV3+ | 90.96 | 96.76 | 94.05 | 93.83 | 41.22 | 4.30 |

| Attention U-Net | 93.12 | 97.82 | 95.63 | 95.96 | 35.60 | 7.42 |

| STTNet | 93.31 | 97.90 | 95.85 | 96.37 | 18.74 | 3.16 |

| DSATNet | 93.92 | 98.06 | 96.40 | 96.78 | 48.50 | 7.02 |

| MSA-UNet | 94.26 | 98.32 | 96.57 | 96.95 | 28.44 | 6.83 |

| Model | mIoU/% | Accuracy/% | F1/% | mPA/% | Params/M | Runtime/(min/epoch) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| U-Net | 84.05 | 94.28 | 89.93 | 90.65 | 24.90 | 6.35 |

| PSPNet | 83.10 | 93.93 | 89.20 | 89.78 | 49.07 | 8.98 |

| DeepLabV3+ | 82.38 | 93.52 | 88.46 | 87.70 | 41.22 | 8.27 |

| Attention U-Net | 84.37 | 94.52 | 90.53 | 91.21 | 35.60 | 13.85 |

| STTNet | 84.86 | 94.69 | 90.76 | 91.64 | 18.74 | 5.94 |

| DSATNet | 85.51 | 95.02 | 91.24 | 91.98 | 48.50 | 13.20 |

| MSA-UNet | 85.92 | 95.24 | 91.50 | 92.26 | 28.44 | 12.93 |

| Model | WHU Dataset | Inria Dataset | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mIoU/% | Acc/% | F1/% | mPA/% | HD/Pixel | mIoU/% | Acc/% | F1/% | mPA/% | HD/Pixel | |

| U-Net | 39.5 | 98.2 | 63.6 | 50.7 | 100.3 | 26.7 | 95.0 | 47.5 | 40.1 | 93.7 |

| PSPNet | 27.8 | 96.3 | 52.3 | 35.5 | 112.2 | 16.7 | 94.4 | 36.3 | 25.2 | 111.8 |

| DeepLabV3+ | 28.1 | 97.3 | 58.8 | 37.9 | 108.7 | 16.9 | 94.1 | 36.1 | 26.5 | 106.4 |

| Attention U-Net | 40.1 | 98.3 | 74.1 | 50.7 | 101.1 | 26.0 | 95.0 | 47.2 | 39.0 | 95.5 |

| STTNet | 39.8 | 98.3 | 77.0 | 48.9 | 90.6 | 22.7 | 94.9 | 42.9 | 33.7 | 95.2 |

| DSATNet | 42.6 | 98.4 | 79.3 | 51.6 | 84.5 | 28.5 | 95.5 | 51.0 | 39.8 | 86.3 |

| MSA-UNet | 42.9 | 98.5 | 78.6 | 52.7 | 86.2 | 29.1 | 95.2 | 51.1 | 42.8 | 85.1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the International Society for Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yao, G.; Chen, Y.; Sun, W.; Zhang, Z.; Tang, Y.; Bi, J. MSA-UNet: Multiscale Feature Aggregation with Attentive Skip Connections for Precise Building Extraction. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2025, 14, 497. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijgi14120497

Yao G, Chen Y, Sun W, Zhang Z, Tang Y, Bi J. MSA-UNet: Multiscale Feature Aggregation with Attentive Skip Connections for Precise Building Extraction. ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information. 2025; 14(12):497. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijgi14120497

Chicago/Turabian StyleYao, Guobiao, Yan Chen, Wenxiao Sun, Zeyu Zhang, Yifei Tang, and Jingxue Bi. 2025. "MSA-UNet: Multiscale Feature Aggregation with Attentive Skip Connections for Precise Building Extraction" ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information 14, no. 12: 497. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijgi14120497

APA StyleYao, G., Chen, Y., Sun, W., Zhang, Z., Tang, Y., & Bi, J. (2025). MSA-UNet: Multiscale Feature Aggregation with Attentive Skip Connections for Precise Building Extraction. ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information, 14(12), 497. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijgi14120497