A Graph Data Model for CityGML Utility Network ADE: A Case Study on Water Utilities

Abstract

1. Introduction

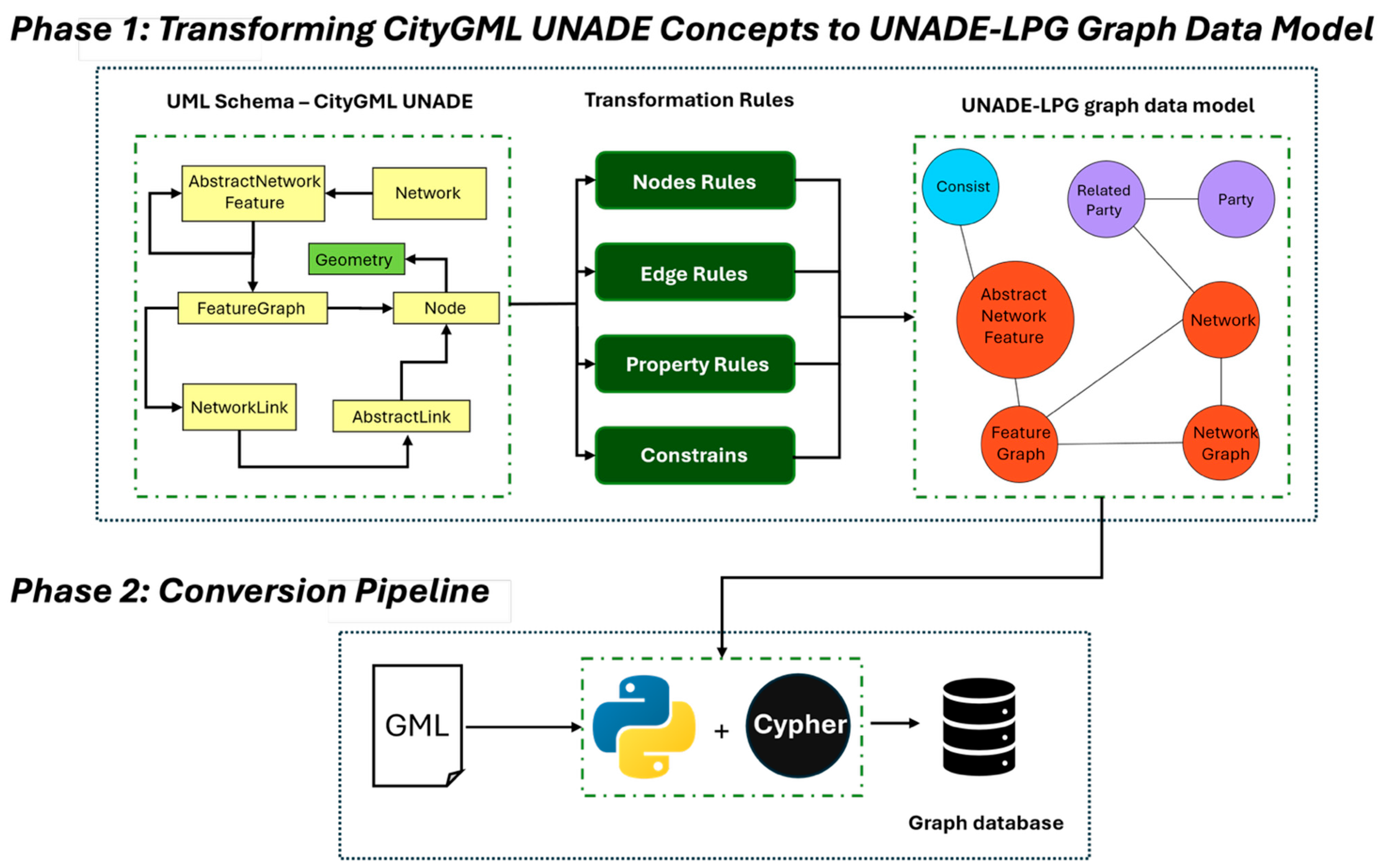

- A generalisable UNADE-LPG graph data model for the CityGML UNADE, aligning its UML-based schema with the LPG formalism.

- A conversion pipeline that transforms standardised CityGML GML files into LPG instances, enabling the population of graph databases with semantically enriched, topologically structured utility network data.

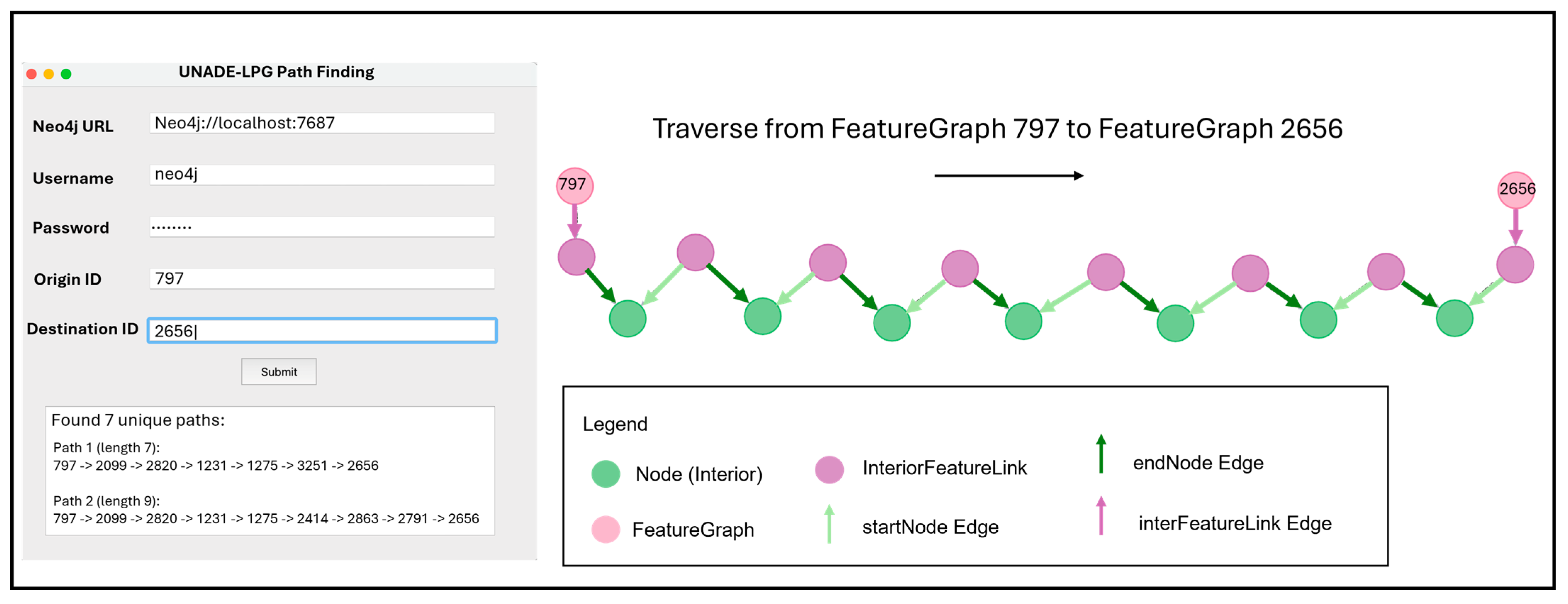

- Feasibility of the proposed UNADE-LPG graph data model is demonstrated through two use cases: (i) a schematic example scenario and (ii) a real-world water network, together with validation covering structural checks, topological continuity, classification behaviour, descriptive graph statistics, and an analytical path-finding query.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Relational Database 3D Urban Spatial Models

2.2. Graph-Based 3D Urban Spatial Model

2.2.1. RDF-Based Approaches

2.2.2. LPG-Based Approaches

2.3. Identified Gaps and Motivation for UNADE-LPG

3. Methodology

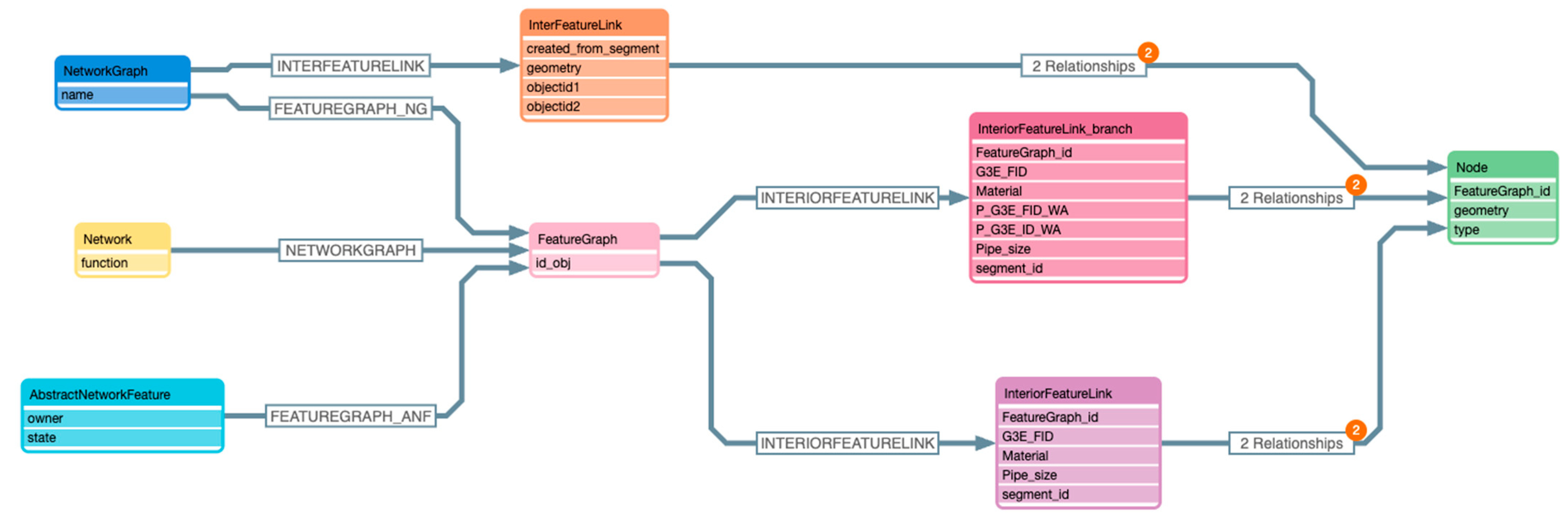

3.1. Phase 1—Transforming CityGML UNADE Concepts to UNADE-LPG Graph Data Model

3.1.1. Nodes Rules

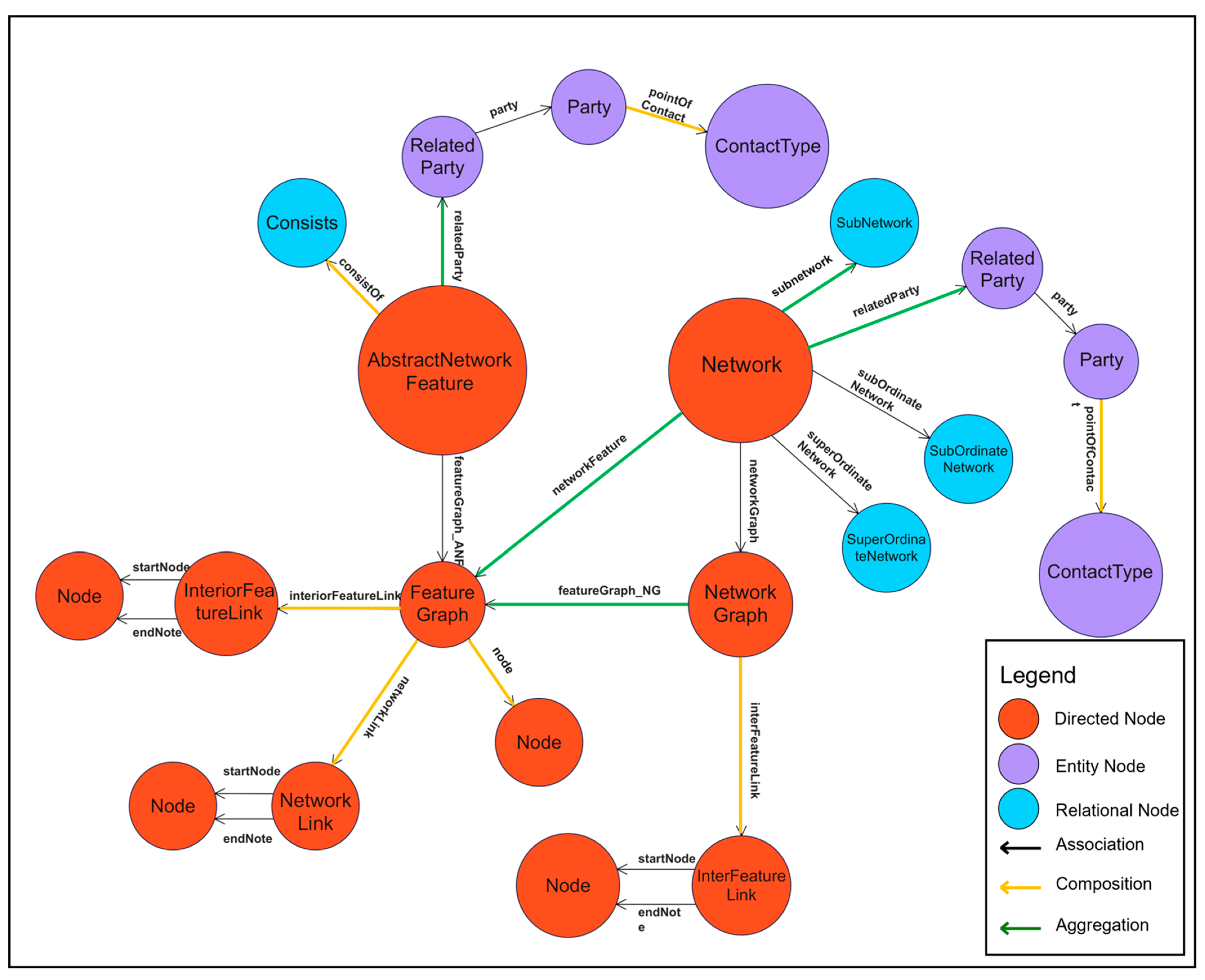

- Directed Nodes

- Directed Nodes are derived from specific FeatureTypes in the CityGML UNADE schema. In CityGML, FeatureTypes define domain-specific entities such as pipes, valves, or network connections, along with their associated properties and relationships. Directed Nodes represent the FeatureTypes that inherently convey directional relationships within the utility network. For example, in the UNADE Core module, InterFeatureLink and NetworkGraph are transformed into Directed Nodes as they structurally define connections between components with an identifiable source and target. In the resulting graph data model, each Directed Node has a label corresponding to its original FeatureType, thereby preserving the semantic role defined in the UML schema within the LPG representation.

- Entity Nodes

- Entity Nodes are generated from properties in a FeatureType that refer to other DataTypes or FeatureTypes, particularly when the referenced elements possess their own attributes or internal structure. In the CityGML schema, DataTypes are reusable class-like constructs that group related attributes but are not standalone spatial features. They typically represent complex attribute structures within a feature. Entity Nodes in the graph data model do not represent directional flow; instead, they hold critical metadata and hierarchical relationships. For instance, the Network feature includes a property relatedParty: RelatedParty [0..*]. Rather than treating this as a primitive attribute, it is modelled as a separate RelatedParty node, with attributes such as role: RoleValue and share: Scale. Furthermore, the party: Party property within RelatedParty refers to another feature, so it is modelled as a separate Party node. This Party node may include attributes such as url: URL [0..1] and connects to a pointOfContact node, which stores contact information (e.g., email, phone, contactRole, etc.).

- Relational Nodes

- In the proposed UNADE-LPG graph data model, Relational Nodes are introduced as an additional modelling construct to explicitly represent key relationships within the utility network that benefit from being treated as first-class entities in the graph. In the original UML schema of CityGML UNADE, such relationships are defined as associations between FeatureTypes. However, when these associations are semantically meaningful, occur frequently, or require metadata (e.g., timestamps, roles, or status), the proposed model represents them as nodes to support richer querying and semantic interpretation. A representative example is the subnetwork relationship, which logically connects a group of infrastructure components (e.g., pipes, valves, and pumps) within the same Network feature. In this case, a Subnetwork node is introduced to serve as an intermediary, linking all participating features. This approach not only maintains semantic clarity but also enables more sophisticated querying. For instance, users can efficiently retrieve all assets belonging to a specific subnetwork, filter based on subnetwork type or function, and perform topological traversals constrained within or across subnetworks. Table 1 presents all node types derived from the CityGML UNADE UML schema and their corresponding representations in the proposed UNADE-LPG graph data model. As shown, different types of nodes are generated from FeatureType, DataType, and Association or Composition relationships defined in the UML schema. This mapping reflects a transformation process that is guided both by the semantic structure embedded in the UML model and the practical requirements of querying utility networks within graph database systems.

3.1.2. Edges Rules

- RelatedParty Relationship

- Party and ContactType Relationship

3.1.3. Property (Attribute) Rules

- AbstractLink

- Node

- Cardinality

- in-edge-(ConnectedNode): Specifies the maximum or exact number of incoming edges from a given node type (e.g., in-edge-InteriorFeatureGraph defines the allowable number of incoming connections from InteriorFeatureGraph to the current node).

- out-edge-(ConnectedNode): Specifies the maximum or exact number of outgoing edges from the current node to a given node type (e.g., out-edge-FeatureGraph indicates the allowable number of outgoing connections from the current node to FeatureGraph).

3.1.4. Constraints

- Composition Rules

- In UML, composition represents a whole–part dependency in which the child’s lifecycle is bound to the parent. In the LPG model, this principle is retained: if a parent node in a composition relationship is deleted, all dependent child nodes must also be removed. However, if a child node maintains other valid connections beyond the composition, it remains in the graph to preserve those relationships. This approach ensures that deletion operations reflect UML semantics without introducing unnecessary data loss.

- 2.

- Aggregation and Association Rules

- In UML, aggregation and association represent weaker dependencies than composition, where the child node can exist independently of the parent. In the LPG model, these relationships do not trigger automatic deletion if the parent node is removed. Instead, the relationship type (aggregation or association), inherited from UML semantics, is stored as a property to preserve its meaning. This distinction is important in utility networks, where shared resources must be modelled correctly. For example, a RelatedParty node may be linked to multiple Network or AbstractNetworkFeature nodes, and it should not be deleted simply because one of those features is removed.

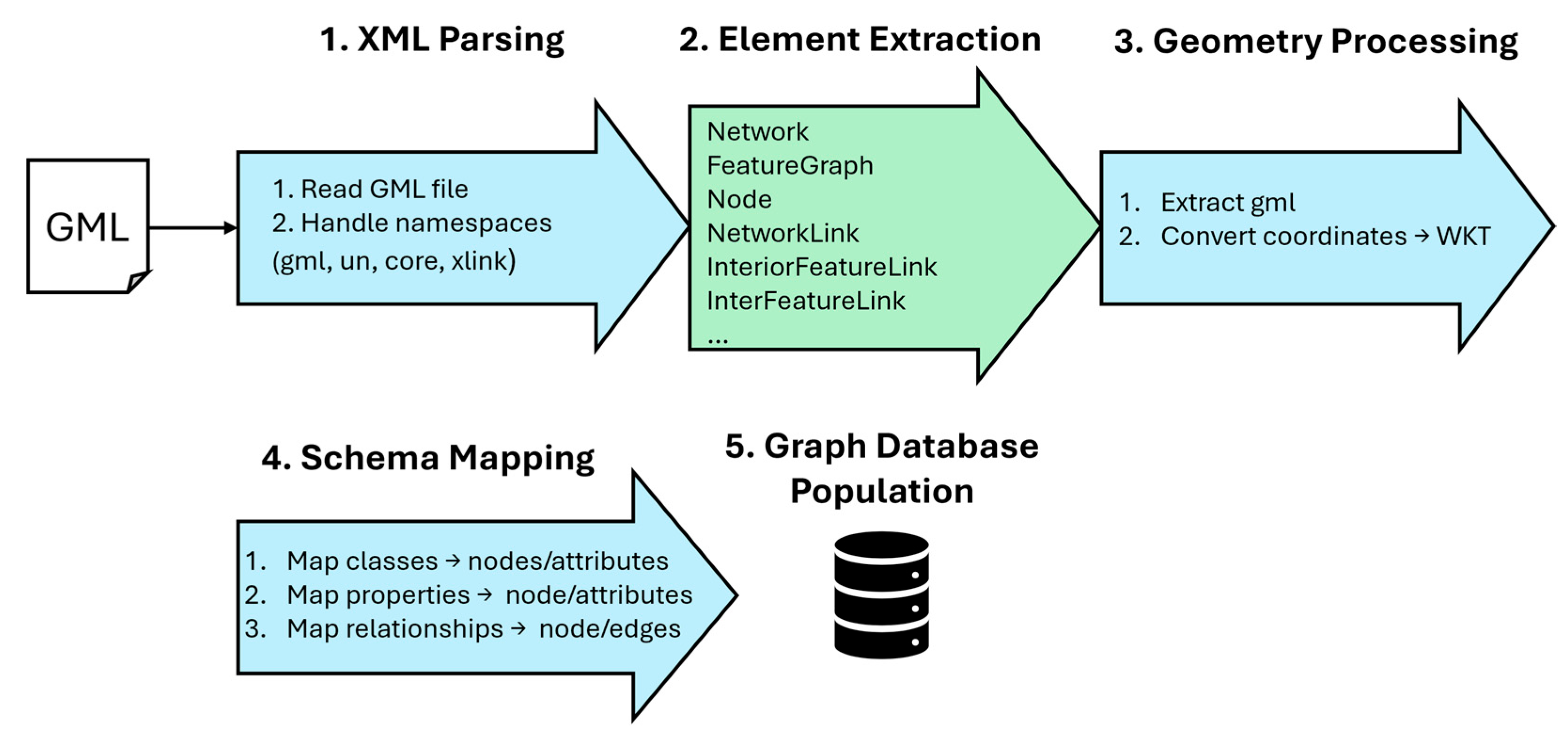

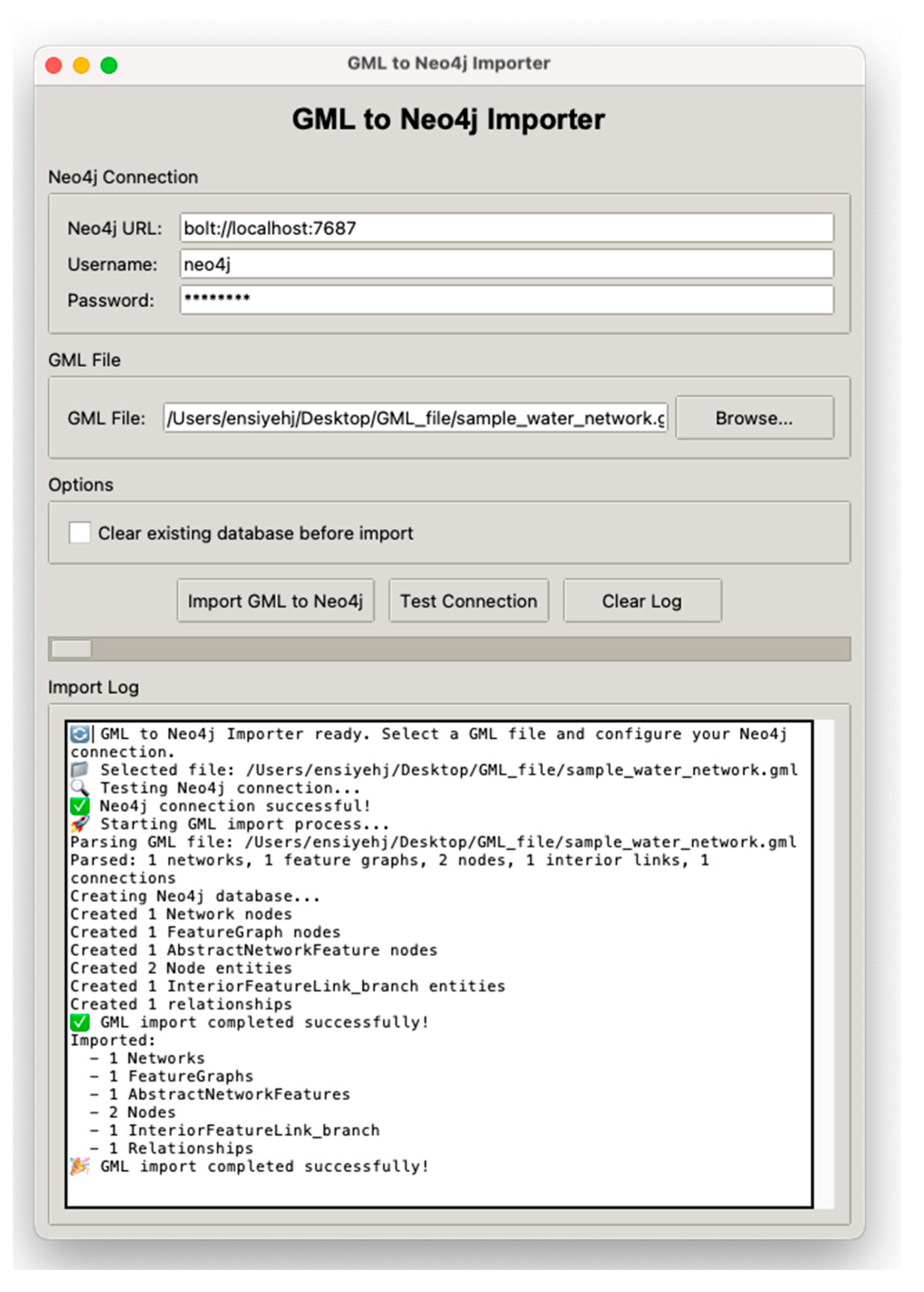

3.2. Phase 2—Conversion Pipeline

4. Implementation and Results

4.1. Implementation Overview

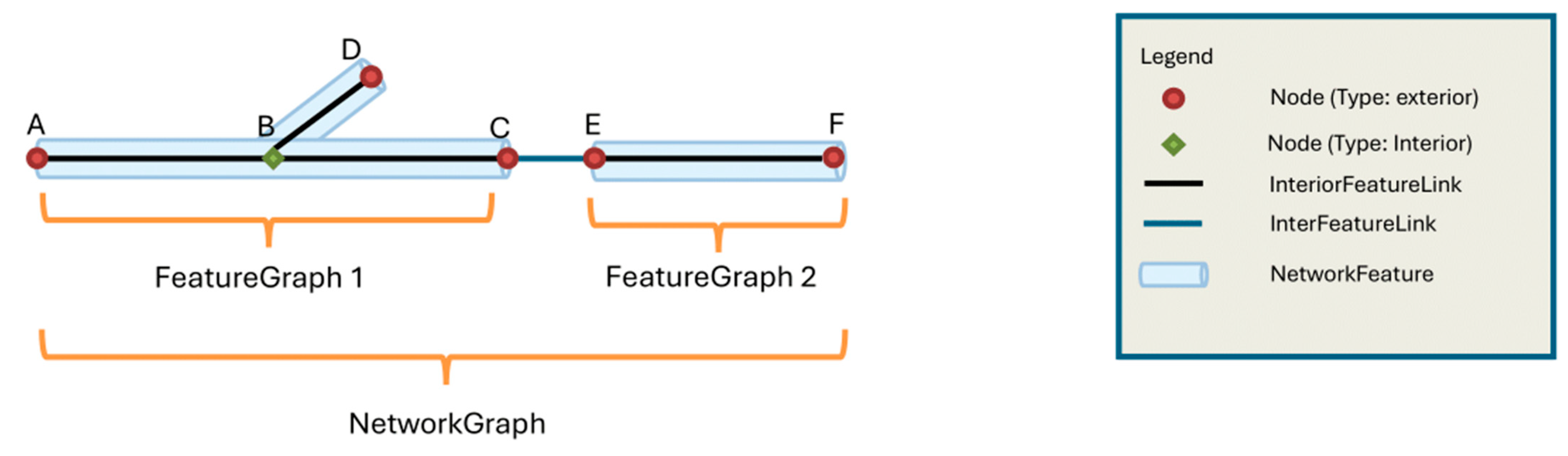

4.2. Case Study 1: Schematic Example

- Inter-pipeline connectivity between two separate pipeline segments, each represented by a distinct FeatureGraph, connected via an InterFeatureLink.

- Branching within a pipeline, modelled using an InteriorFeatureLink with a shared interior node.

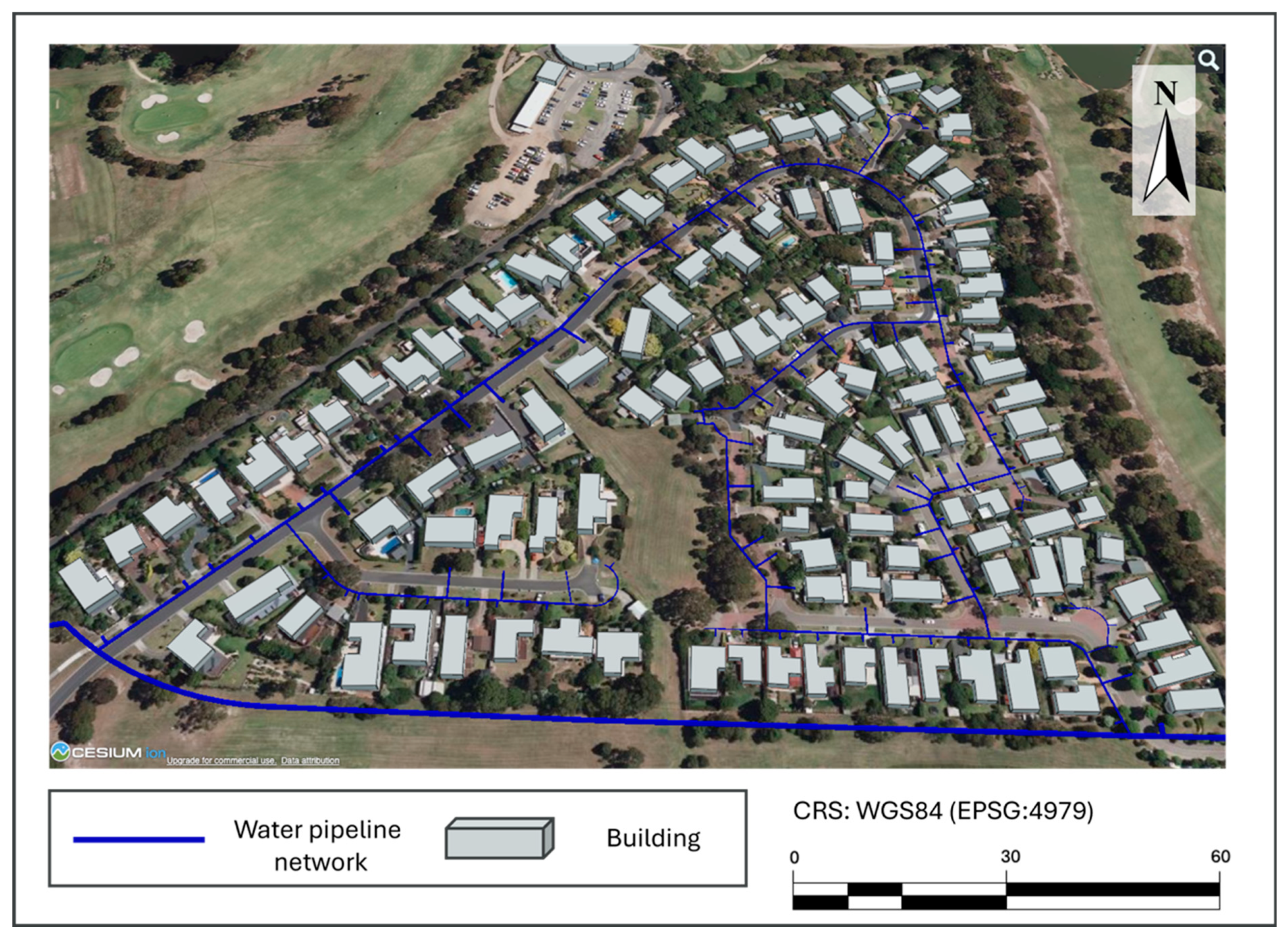

4.3. Case Study 2: CityGML UNADE GML File

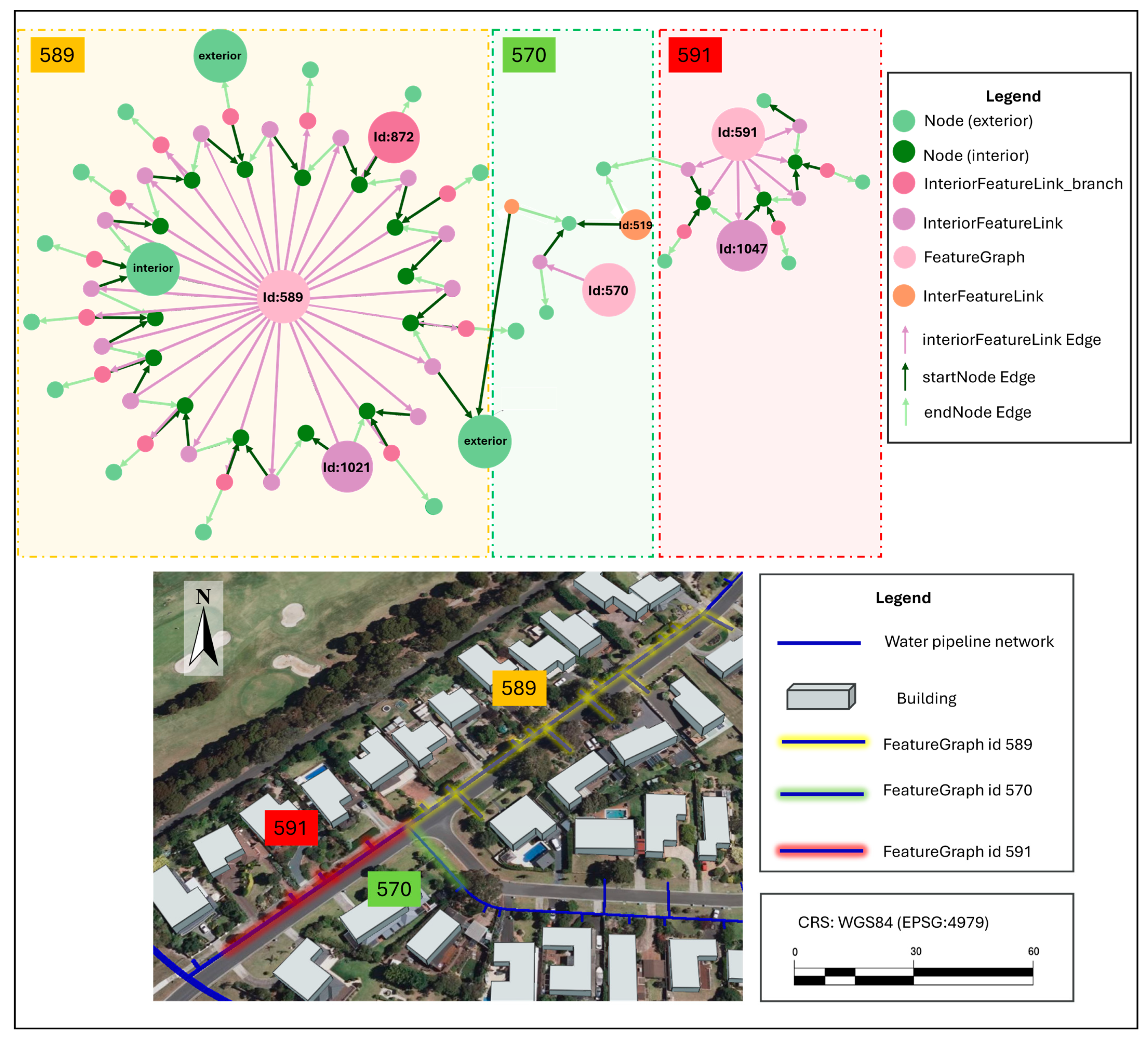

- Orange nodes denote InterFeatureLink elements, which explicitly capture intersections between the three pipelines. In this example, two InterFeatureLinks connect the yellow, red, and green networks.

- Pink nodes represent FeatureGraph elements, which group pipeline segments (InteriorFeatureLinks) and their associated branches under a common identifier. For instance, the yellow pipeline includes 13 branch connections, each modelled as InteriorFeatureLink_branch nodes attached to the same FeatureGraph.

- InteriorFeatureLink nodes correspond to individual pipeline segments between branches, preserving the real-world structure within the graph.

- Green nodes correspond to Node elements that capture 3D geometry for pipeline start and end points. Shared nodes represent interior junctions where segments meet, while exterior nodes mark free ends that either terminate or connect to other pipelines.

4.4. Validation

4.4.1. Structural Conformance

- Rule 1: Isolated Nodes Rule

- Valid Case: A Node representing a junction is connected to two InteriorFeatureLinks, ensuring it contributes to the continuity of the pipeline.

- Invalid Case: A Node appears in the graph with no edges (e.g., a junction geometry imported without connecting pipelines).

- Rule 2: Node Degree Rule

- Valid Case: A branch segment links its parent FeatureGraph and two geometry nodes.

- Invalid Case: A pipeline segment missing a connection with Node (degree < 3).Check 2: Node Degree

- Valid Case: A node connects exactly two InteriorFeatureLinks at an intersection.

- Invalid Case: An exterior node with degree 0 (no pipeline attached).

- Valid Case: An InterFeatureLink connects exterior nodes of two pipelines and the overarching NetworkGraph.

- Invalid Case: An InterFeatureLink connected to only one exterior node.

4.4.2. Topological Consistency

- Rule 3: Topological Consistency Rule

- Check 1: Exclusive Membership

- Valid Case: A pipeline segment is linked only to its parent FeatureGraph.

- Invalid Case: A pipeline segment connected to two different FeatureGraphs, creating ambiguity in network ownership.

- Check 2: Segment Alignment

- Valid Case: Two segments meet at a shared Node, with their end and start coordinates exactly matching.

- Invalid Case: Two segments are connected in the graph, but their coordinates are misaligned, producing a geometric gap or overlap.

- Check 3: Branch Geometry

- Valid Case: A branch pipeline joins a main pipeline at a node shared by both.

- Invalid Case: A branch segment connected in the graph without matching the spatial coordinates of the main pipeline, resulting in a “floating” connection.

4.4.3. Graph Database Integrity

- Rule 4: Normalisation Rule

- Check 1: Duplicate Geometry Nodes

- Valid Case: Two pipelines intersect at the same junction, represented by a single shared node.

- Invalid Case: Two separate nodes with identical coordinates represent the same junction, causing redundancy.

- Check 2: Coincident Nodes at a Junction

- Valid Case: A junction is represented by one node reused in multiple pipeline connections.

- Invalid Case: Two distinct nodes, both connected to different segments, occupy the same location and fragment connectivity.

- Check 3: Reuse of Shared Points

- Valid Case: Two InteriorFeatureLinks use the same node for their shared endpoint.

- Invalid Case: Each segment introduces a new endpoint node at the same location, breaking continuity.

- Check 4: Unique Start and End Nodes

- Valid Case: A segment starts at Node A and ends at Node B, representing a real pipeline.

- Invalid Case: A segment starts and ends at the same node, creating a zero-length segment.

- Rule 5: Classification Rule

- Valid Case: All SEW-owned pipelines are classified as reticulation mains, while private pipelines are classified as fire service.

- Invalid Case: A reticulation main is classified as privately owned, contradicting the operational reality.

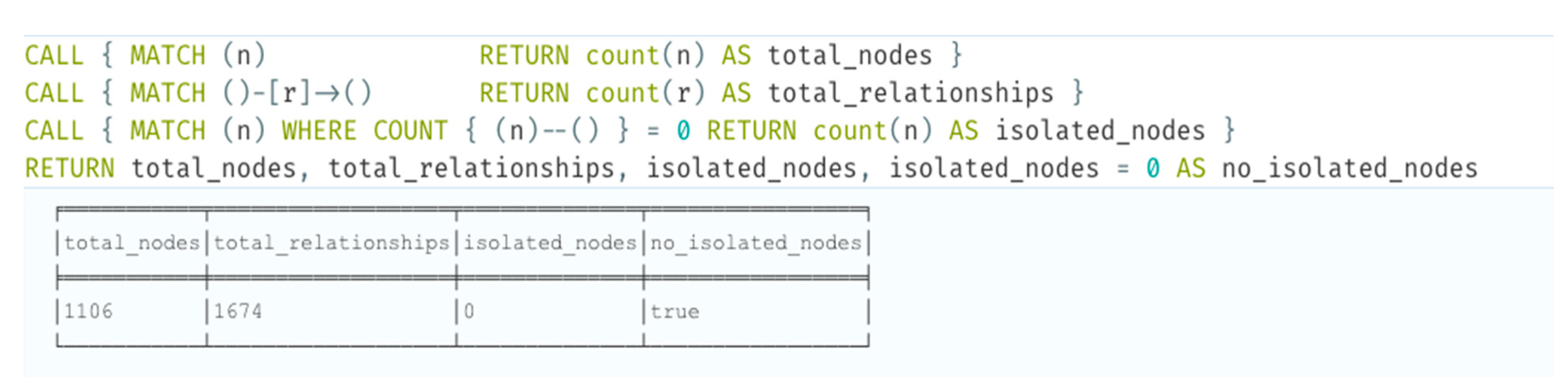

4.4.4. Descriptive Graph Statistics

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Software Availability

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- OpenGeospatialConsortium. OGC City Geography Markup Language (CityGML) Part 1: Conceptual Model Standard. 2021. Available online: https://docs.ogc.org/is/20-010/20-010.html (accessed on 8 December 2025).

- Kutzner, T.; Kolbe, T.H. Extending semantic 3D city models by supply and disposal networks for analysing the urban supply situation. In Proceedings of the Lösungen für eine Welt im Wandel, Dreiländertagung der SGPF, DGPF und OVG, 36. Wissenschaftlich-Technische Jahrestagung der DGPF, Bern, Germany, 7–9 July 2016; pp. 382–394. [Google Scholar]

- Javaherian Pour, E.; Atazadeh, B.; Rajabifard, A.; Sabri, S. Review and assessment of 3D spatial data models for managing underground utility networks. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2025, 157, 106219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duijn, X.d.; Agugiaro, G.; Zlatanova, S. Modelling Below- and Above-Ground Utility Network Features with the CityGML Utility Network ADE: Experiences From Rotterdam. In Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Smart Data and Smart Cities, Delft, The Netherlands, 4–5 October 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Vishnu, E.; Sameer, S. OGC CityGML 3D City Models Enriched with Utility Infrastructures for Developing Countries. J. Indian Soc. Remote Sens. 2021, 49, 813–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anuyah, S.; Bolade, V.; Agbaakin, O. Understanding graph databases: A comprehensive tutorial and survey. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2411.09999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bechberger, D.; Perryman, J. Graph Databases in Action; Manning Publications Co.: Shelter Island, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Ilonen, J. A Case Study on Transitioning from Relational Data models to Graph Data models in an Industrial Context. Master’s Thesis, Åbo Akademi University, Turku, Finland, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Javaherian Pour, E.; Atazadeh, B.; Rajabifard, A.; Sabri, S. Developing a CityGML-based Graph Data Model for Utility Infrastructure in Smart Cities. ISPRS Ann. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2025, X-G-2025, 405–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, Q. Geospatial Inference and Management of Utility Infrastructure Networks. Ph.D. Thesis, Newcastle University, Newcastle upon Tyne, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Dunn, S.; Holmes, M. Development of a hierarchical approach to analyse interdependent infrastructure system failures. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2019, 191, 106530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Rui, Y.; Zhu, H.; Lu, L.; Li, X. Comprehensive digital twin for infrastructure: A novel ontology and graph-based modelling paradigm. Adv. Eng. Inform. 2024, 62, 102747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, F.-L.; Qiao, Y.-K.; Yang, C. Building a knowledge graph for operational hazard management of utility tunnels. Expert Syst. Appl. 2023, 223, 119901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, S.H.; Kolbe, T.H. A multi-perspective approach to interpreting spatio-semantic changes of large 3D city models in citygml using a graph database. ISPRS Ann. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spatial Inf. Sci. 2020, VI-4/W1-2020, 143–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, S.H.; Yao, Z.; Kolbe, T.H. Spatio-semantic comparison of large 3D city models in CityGML using a graph database. ISPRS Ann. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2017, 4, 99–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasprzyk, J.-P.; Nys, G.-A.; Billen, R. Towards a multi-database CityGML environment adapted to big geodata issues of urban digital twins. Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2024, 48, 101–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Z.; Kolbe, T.H. Dynamically extending spatial databases to support CityGML application domain extensions using graph transformations. Kult. Erbe Erfassen Und Bewahr.-Von Der Dok. Zum Virtuellen Rundgang 2017, 37, 316–331. [Google Scholar]

- Tsai, B.-S. Extending the 3D City Database 5.0 to Support CityGML Application in QGIS. Master’s Thesis, Delft University of Technology, Delft, The Netherlands, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Sadavare, A.; Kulkarni, R. A review of application of graph theory for network. Int. J. Comput. Sci. Inf. Technol. 2012, 3, 5296–5300. [Google Scholar]

- Bonifati, A.; Fletcher, G.; Voigt, H.; Yakovets, N. Querying Graphs; Springer Nature: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Kousis, A. Managing Smart City Linked Data with Graph Databases: An Integrative Literature Review. In Graph Databases; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2023; pp. 118–141. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, L.; Xiao, G.; Pano, A.; Fumagalli, M.; Chen, D.; Feng, Y.; Calvanese, D.; Fan, H.; Meng, L. Integrating 3D city data through knowledge graphs. Geo-Spat. Inf. Sci. 2025, 28, 780–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahu, S.; Mhedhbi, A.; Salihoglu, S.; Lin, J.; Özsu, M.T. The ubiquity of large graphs and surprising challenges of graph processing: Extended survey. VLDB J. 2020, 29, 595–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angles, R.; Thakkar, H.; Tomaszuk, D. RDF and Property Graphs Interoperability: Status and Issues. AMW 2019, 2369, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Arenas, M.; Gutierrez, C.; Pérez, J. Foundations of RDF databases. In Reasoning Web International Summer School; Tessaris, S., Franconi, E., Eiter, T., Gutierrez, C., Handschuh, S., Rousset, M.-C., Schmidt, R.A., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2009; pp. 158–204. [Google Scholar]

- Vinasco-Alvarez, D.; Samuel, J.; Servigne, S.; Gesquière, G. Towards an Automated Transformation of an nD Urban Data Model to a Computational Ontology Network: From UML to OWL, From CityGML 3.0 to “CityOWL”. ISPRS Ann. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2024, X-4/W4-2024, 231–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, P.D.; Gu, B.H.; Lam, H.K.; Ok, S.Y.; Lee, S.H. Digital Twin Smart City: Integrating IFC and CityGML with Semantic Graph for Advanced 3D City Model Visualization. Sensors 2024, 24, 3761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chadzynski, A.; Li, S.; Grišiute, A.; Chua, J.; Hofmeister, M.; Yan, J. Semantic 3D city interfaces—Intelligent interactions on dynamic geospatial knowledge graphs. Data-Centric Eng. 2023, 4, e20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donkers, A.; Yang, D.; Baken, N. Linked Data for Smart Homes: Comparing RDF and Labeled Property Graphs. In Proceedings of the LDAC2020—8th Linked Data in Architecture and Construction Workshop, Dublin, Ireland, 17–19 June 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Gelling, E.; Fletcher, G.; Schmidt, M. Bridging graph data models: RDF, RDF-star, and property graphs as directed acyclic graphs. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2304.13097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hor, A.H.; Sohn, G.; Claudio, P.; Jadidi, M.; Afnan, A. A semantic graph database for BIM-GIS integrated information model for an intelligent urban mobility web application. ISPRS Ann. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2018, 4, 89–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agoub, A.; Kunde, F.; Kada, M. Potential of graph databases in representing and enriching standardized Geodata. Tagungsband Der 2016, 36, 208–216. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Z.; Pouliot, J.; Hubert, F. A Hierarchy of Levels of Detail for 3D Utility Network Models. In Proceedings of the International 3D GeoInfo Conference, Munich, Germany, 12–14 September 2023; pp. 543–561. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, I.; Webber, J.; Eifrem, E. Graph Databases: New Opportunities for Connected Data; O’Reilly Media, Inc.: Sebastopol, CA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Angles, R.; Gutierrez, C. Survey of graph database models. ACM Comput. Surv. (CSUR) 2008, 40, 1–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, T.; Nagel, C.; Kolbe, T.H. Integrated 3D modeling of multi-utility networks and their interdependencies for critical infrastructure analysis. In Advances in 3D Geo-Information Sciences; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011; pp. 1–20. [Google Scholar]

| UML Element Type | UML Class Name | Mapped UNADE-LPG Graph Data Model |

|---|---|---|

| FeatureType | AbstractNetworkFeature | Directed Nodes |

| Network | ||

| NetworkGraph | ||

| FeatureGraph | ||

| Node | ||

| InteriorFeatueLink | ||

| InterFeatureLink | ||

| NetowrkLink | ||

| DataType | RelatedParty | Entity Nodes |

| ContactType | ||

| FeatureType | Party | |

| Association | subOrdinateNetwork | Relational Nodes |

| superOrdinateNetwork | ||

| subNetwork | ||

| Composition | consistsOf |

| UNADE-LPG Graph Data Model Node Source | UNADE-LPG Graph Data Model Node Target | UNADE-LPG Graph Data Model Edge Label | UNADE-LPG Graph Data Model Edge Attribute |

|---|---|---|---|

| NetworkGraph | FeatureGraph | featureGraph-NG | Aggregation |

| Network | FeatureGraph | networkFeature | |

| Network | SubNetwork | subnetwork | |

| Network | RelatedParty | relatedparty | |

| AbstractNetworkFeature | RelatedParty | relatedparty | |

| AbstractNetworkFeature | ConsistOf | consistof | Composition |

| FeatureGraph | InteriorFeatueLink | interiorFeatueLink | |

| FeatureGraph | NetworkLink | networkLink | |

| FeatureGraph | Node | node | |

| NetworkGraph | InterFeatureLink | interFeatureLink | |

| Party | ContactType | pointOfContact | |

| AbstractNetworkFeature | FeatureGraph | featureGraph_ANF | Association |

| InteriorFeatueLink | Node | startNode/endNode | |

| NetowrkLink | Node | startNode/endNode | |

| InterFeatureLink | Node | startNode/endNode | |

| Network | SuperOrdinateNetwork | superOrdinateNetwork | |

| Network | SubOrdinate Network | subOrdinateNetwork | |

| Network | NetworkGraph | networkGraph | |

| RelatedParty | Party | party |

| Validation Type | Rule | Total Node | Nodes with Degree 1 | Nodes with Degree 2 | Nodes with Degree 3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| InteriorFeatureLink | Expected degree: 3 (connects to FeatureGraph, Node) | 387 | 0 | 0 | 387 |

| InteriorFeatureLink_branch | Expected degree: 3 (connects to FeatureGraph, Node) | 113 | 0 | 0 | 113 |

| Node (type:interior) | Expected degree: 2 (connects two InteriorFeatureLinks) or 3 (connects two InteriorFeatureLinks and one InteriorFeatureLink_branch) | 348 | 0 | 238 | 110 |

| InterFeatureLink | Expected degree: 3 (connects two Nodes and one NetworkGraph) | 16 | 0 | 0 | 16 |

| Checks | Expected Condition | Violations | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Exclusive membership | Each InteriorFeatureLink belongs to exactly one FeatureGraph | 0 | All 387 segments correctly assigned |

| Segment alignment | End coordinates of segment A coincide with start coordinates of segment B | 0 | No gaps or overlaps observed |

| Branch geometry | InteriorFeatureLink_branch shares junction node with its connected InteriorFeatureLink | 0 | All 113 branch links are correctly aligned |

| Checks | Tolerance (ε) | Violations |

|---|---|---|

| Duplicate geometry nodes | 0.001 m | 0 |

| Coincident but distinct nodes at a junction | 0.001 m | 0 |

| Reuse of shared points | N/A | 0 |

| Unique start and end nodes | N/A | 0 |

| Query | Reticulation Main | Fire Service | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Owner: SEW | 40 | 0 | 40 |

| Owner: Private | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| Total | 40 | 2 | 42 |

| Statistic | Value |

|---|---|

| Total nodes | 1106 |

| Total Edges | 1674 |

| Number of connected components | 2 (SEW network + private fire-service network) |

| Nodes in reticulation main (SEW) | 1073 |

| Edges in reticulation main (SEW) | 1528 |

| Nodes in fire-service network (private) | 13 |

| Edges in fire-service network (private) | 14 |

| SEW-owned nodes | 1073 |

| Private-owned nodes | 13 |

| Nodes in operational (OPR) state | 206 |

| Nodes in migration (MIG) state | 881 |

| Highest-degree node | 58 |

| Lowest degree node | 1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the International Society for Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Javaherian Pour, E.; Atazadeh, B.; Rajabifard, A.; Sabri, S.; Norris, D. A Graph Data Model for CityGML Utility Network ADE: A Case Study on Water Utilities. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2025, 14, 493. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijgi14120493

Javaherian Pour E, Atazadeh B, Rajabifard A, Sabri S, Norris D. A Graph Data Model for CityGML Utility Network ADE: A Case Study on Water Utilities. ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information. 2025; 14(12):493. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijgi14120493

Chicago/Turabian StyleJavaherian Pour, Ensiyeh, Behnam Atazadeh, Abbas Rajabifard, Soheil Sabri, and David Norris. 2025. "A Graph Data Model for CityGML Utility Network ADE: A Case Study on Water Utilities" ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information 14, no. 12: 493. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijgi14120493

APA StyleJavaherian Pour, E., Atazadeh, B., Rajabifard, A., Sabri, S., & Norris, D. (2025). A Graph Data Model for CityGML Utility Network ADE: A Case Study on Water Utilities. ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information, 14(12), 493. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijgi14120493