1. Introduction

With some 12 million sheep, Romania holds the second-largest sheep population in the European Union [

1], also being a significant global supplier of live sheep. In 2023, it was the world’s second-largest exporter [

2], confirming the long-term growth trend in exports for more than 20 years. More than a third of these animals are found in the counties overlapping the Carpathians [

3], one of the best preserved mountain ecosystems in Europe [

4].

Sheep breeding in Europe’s mountains, just as elsewhere in the world, has been a way of life for millennia, as well as a historical element that shaped landscapes, cultures, traditions, and economies. It relied on transhumance, a seasonal migration of flocks, with significant environmental benefits and outstanding importance for maintain local identities. Hence, in 2023, Alpine transhumance in 10 European countries, including Romania, was secured on the UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage, elevating this traditional practice to heritage to be actively safeguarded, keeping landscapes alive [

5].

A landscape and its structure are usually described along two main axes, composition and configuration; they have been shaped by patterns and intensity of land use as a result of the number and distribution of the population within a given area. Within the mountainous areas, traditional land-use practices employed by hundreds of generations shape a multifunctional and sustainable agricultural landscape [

6]. Landscapes generated by sheep husbandry in particular are a significant component of the cultural landscape, being quite resilient to changes [

7]. Since animals spend the entire summer on the mountain pastures and are tended by shepherds, there is a long tradition of building dwellings—huts, shelters, sheepfolds—that give a particular feature to the landscape.

A series of studies conducted for high-altitude villages and farms throughout Europe highlight the changes in the rural landscape in recent decades [

8,

9,

10,

11] and the perception of these changes [

12], following a common trend of abandonment of mountain farming [

13,

14] and traditional practices. This phenomenon was documented for all the mountain ranges in Europe: while in the Italian Alps, the abandonment of traditional land use is ‘less evident’ (mainly in areas with significant level of self-governance) [

15], it is ‘pervasive’ in the Pyrenees [

13] and ‘widespread’ in the Polish Carpathians [

16], where traditional landscapes are vanishing rapidly [

17]. It is also documented in the Romanian Carpathians [

18,

19], where the highest rate of abandonment occurred between 1990 and 2000 [

20,

21]. Consequently, the agricultural mountain landscape in the Romanian Carpathians changed from variety and individuality to simplification and uniformization [

22]. This phenomenon is the result of population aging which has affected Europe on the whole and rural, remote areas even more [

23,

24,

25], due to increased migration to cities nearby [

26,

27] and the younger generation’s loss of interest in traditional practices [

28,

29]. Although its extent and drivers may vary from place to place, the abandonment of traditional agricultural land in mountainous areas is a systemic challenge that the entire European Carpathians is facing, which highlights the urgency of recording and understanding it in this research area.

Settlements in the Carpathians and the land use around them are of particular importance not only as cultural heritage, but also from a biodiversity point of view on several levels: interspecific biodiversity, ecodiversity, and agrobiodiversity [

30]. The abandonment of traditional forms of land use endangers the grasslands’ biodiversity; mowing and grazing hay meadows have been hailed as a complex farming system for grassland conservation [

31]. A recent study carried out in the Northern Carpathians indicates that, in the near future, as a result of farming abandonment, almost half of the meadows located above 750 m high would be permanently degraded by forest succession [

32].

Pastoralism in the Southern Carpathians has been widely examined within Romanian scholarship [

19,

33,

34,

35], providing a substantial basis for understanding mountain mobility, land use, and seasonal settlement systems. Research from Mărginimea Sibiului [

36,

37,

38,

39,

40] focuses on the persistence and reconfiguration of transhumance, the functioning and organization of sheepfolds, and the economic importance of animal husbandry. Studies conducted in other Carpathians massifs such as Fagaras, Lotru, and Sureanu offer detailed evaluations of alpine and subalpine grasslands, pastoral value, and grazing effects on biodiversity [

41,

42,

43]. Ethnographic [

44,

45,

46] and geographical work focusing on various other representative Romanian areas (Rucăr-Bran, Hateg County and Jiu corridor, Maramureș) provides further insight into the cultural dimensions of shepherding, points of tension with tourism, and the reorganization of seasonal routes. The current literature on the topic shows that pastoral mobility and temporary pastoral dwellings such as shelters and sheepfolds are a keystone of high-mountain social, economic, and ecological systems since they dictate where, when, and how grazing pressure occurs, while also impacting rural livelihoods. Yet, they are not included in any official datasets as they are often informal and poorly recorded. Despite the depth of existing ethnographic, historical, and geographic studies, particularly in areas such as Marginimea Sibiului, no research has produced a spatially explicit, region-wide documentation of high-altitude pastoral infrastructure. Addressing this gap, the present study analyzes the non-permanent high-altitude dwellings in the central part of the Southern Carpathians, providing a systematic inventory of shelters and sheepfolds. It focuses on the distribution of these temporary pastoral dwellings, the correlation between the two types (shelters and sheepfolds) and the land use (hay lands, meadows, cultivated lands). Parang Mountains are a representative mountain ecological system for the Southern Carpathians and lessons can be tailored to other mountains. The paper transforms qualitative knowledge into a comprehensive geospatial dataset.

To systematically understand the spatial organization of these temporary settlements and the factors driving them, this research aims to answer the following three questions:

Q1. Are pastoral settlements clustered in certain areas (platforms, valleys) or more evenly distributed across the mountainous area under study?

Q2. How do traditional practices and land use influence the spatial distribution of these temporary pastoral settlements?

Q3. How does the current spatial distribution of shelters and sheepfolds in the area compare to the traditional historical areas for sheep breeding?

The paper is structured as follows: first, the conceptual lens through which data are analyzed are discussed, namely pastoralism and land use, economic, social, and cultural perspectives of mountain areas, and the changes these areas face. The study area subchapter presents both the physical setting, the social context that influences the location of these temporary settlements, and the historical conditions, followed by data collection and analysis. The results section focuses on the two main types of temporary pastoral settlements representative for this mountain area, namely shelters and sheepfolds, while the last section addresses the ecological and environmental impact of grazing in the area, conflict mitigation, and livestock protection as well as the cultural dimension of these traditional activities.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

In the central part of the Southern Carpathians, the Parâng-Cindrel Mountains stand out as one of the tallest and largest Romanian Carpathian groups. With the highest altitude of 2519 m, it covers 38% of the Southern Carpathians (5530 km

2), being considered as the most important hydrographic and orographic node in the area (

Figure 1).

The characteristic features of this group are its massiveness and relatively wild forest areas preserved in spite of intensive population and related human activities favored by large planation surfaces. This area also holds the longest system of interfluves in the Romanian Carpathians, marked by broad planation surfaces at various altitudes. A lower Carpathian erosion platform is located at 700–1000 m, as a peripheral step, wider on the northern side and narrower on the southern side [

47]. This lower Carpathian planation surface has offered good conditions for the emergence and development of rural settlements, both permanent and temporary. It is called Platforma Luncanilor (Luncani’s Platform) [

48] in the west, within the Șureanu Mountains or Săliște Surface [

49] in the northeast, within the Cindrel Mountains.

The Southern Carpathians feature a mountain climate with significant variations by altitude. At elevations above 2000 m, the climate is very cold, with freezing average annual temperatures and precipitation exceeding 1200 mm. On the wide ridges and small plateaus, there are alpine pastures with numerous cold-resistant plants. Between 1200 and 1700 m, average temperatures range from 2 to 3 °C, with 1000–1200 mm of precipitation, where mostly coniferous forests are found. Sometimes, the forests were cleared and converted into pastures. In the lower mountain zone, at 900–1000 m, average annual temperatures are 4–5 °C and precipitation totals 800–1000 mm. Here, the easily accessible terrain, with broad, gentle ridges, enabled extensive forest clearing in the Șureanu, Cindrel, and Lotru Mountains, giving rise to pastures, hayfields, and cultivated land scattered with temporary seasonal dwellings. Driven largely by longstanding pastoral practices, these grasslands steadily expanded into former forest and dwarf-pine areas. Over time, they supported a highly developed pastoral system, unparalleled elsewhere in the Romanian Carpathians [

50]. During the 20th century, some 10% of the forest fund within Parang-Cindrel Mountains was lost through land-use conversion, resulting in the current areas cultivated with cereals and fruit trees or occupied by hayfields and pastures [

51]. This is a very sparsely populated area, with only scattered villages located on the north-western part of the study area, on the gentle slopes of the Sureanu and Cindrel Mountains.

With a rather stormy history that caused almost 80% of the Carpathian area to be ruled by the Austro-Hungarian Empire [

52] and only a smaller part by Romania until WWI, the study area was located between two different political regimes. Hence, different historical conditions and ethnic influences shaped local identities and practices. In this unique mountain area, the area came into contact local communities from Mărginimea Sibiului (Hermannstädter Randgebiet) [

36], Loviștea Country [

53], Luncani Platform (Hațeg Country—Wallenthal; Sebeș area—Mühlbach) [

40,

54], Petroșani Region [

55], and Oltenia at the Mountains’ Feet [

48], each one having its own ethnological, cultural, and architectural heritage, as well as its own typology for settlements and land use. During the feudal period, transhumance appeared and reached its peak during the 18th and 19th centuries [

37,

56]. Consequently, these mountains were colonized by the local peasants at the mountains’ foot areas as an alternative strategy to ‘maximize use of the higher surfaces for subsistence by establishing permanent hamlet settlements [

57]; hence, temporary dwellings/shelters called

sălașe—an outlying grazing station used seasonally by some family members—dotted these mountains. In some cases, these temporary dwellings duplicated the household from the village, having the same functions during the warm period of the year [

58]. These shelters, together with sheepfolds, account for the “pastoral type of humanization” within the Carpathians, which is characterized by its own forms of non-permanent dwellings [

40,

56].

The shelters represent those high-altitude dwellings that are used only temporarily during certain periods of the year and that have large areas of hayfields around them (

Figure 2) and small patches cultivated mainly with potatoes and sometimes other vegetables as well. They have different regional names depending on the area where they are located because the main watershed/interfluves constituted the border between different historical regions. Thus, shelters are called “sălașe” in Transylvania (from szállás/Hungarian), “conace” in northern Oltenia, “colibe” in the Petroșani Depression, and “hatchlets, odăi” in Țara Oltului and Valea Lotrului. All these terms designate the temporary high-altitude dwellings that are analyzed and for which a type of semi-transhumance specific to each region is practiced. A correlation is highlighted between the density of these types of shelters and land use.

There is a traditional land-use model in which mountain livestock farming is practiced by rotation on the favorable lands of each season. Thus, the animals winter in the village hearth where there is a minimum area for the number of animals owned by each family. During the spring, when the snow disappears for the first time on the middle step of the mountains (on average at 850–1250 m), sheep climb to this altitude where they graze freely for a period of 5–7 weeks before going further, for the summer period, to the sheepfolds in the high area (1770–2165 m).

From the shelters with better accessibility, the hay harvested during the summer is transported to the village households in the winter (this traditional transport of hay on wooden supports by dragging on the snow is locally called “târs”). Also, for a period of five to seven weeks, cattle stay around the dwellings with some of the family members, who eat only the vegetables traditionally grown there in the spring (“holda”, meaning the harvest from the mountains). Then, for approximately 3 months, the meadow around the huts switches from pasture to hayfield, after which, during the fall, hayfield–pasture alternation is performed once more (a short grazing in early fall and a new mowing for the late fall grass called “otava”). This is the small transhumance/pendulation that has become frequent in the last 30 years due to the sharp decrease in the number of animals alongside the socio-economic changes and the restitution of lands in the lower areas to the former owners. This fact has greatly limited the large transhumance practiced with sheep, especially in the 19th century and the first half of the 20th century, as a pendulum between the Carpathians and the Danube.

In the vicinity of these haylofts, dwellings are built, usually consisting of a room that serves as both a bedroom and a kitchen, 1–3 stables, and pens/fences for cattle (

Figure 3). There are also dwellings with 2–3 rooms, which are sometimes permanently inhabited, especially by the third generation of the family (Țara Hațegului).

More than 50 years ago, the inhabitants of these shelters had an autonomy of approximately 3 months following the subsistence agriculture on small areas and provision of firewood/fuel from their own patches of forest). Currently, the stay in the temporary shelters has been reduced to an average period of 7 weeks per year.

In the mountainous area, for most of the time, the inhabitants’ almost exclusive occupation was mountain agriculture. Throughout Romania, the Carpathians have been the domain of pastoral communities [

26], and the study area contains the most significant pastoral region in Romania, Mărginimea Sibiului [

37], with a unique intensity of the pastoral life [

38], along with other areas for traditional agriculture and pastoral activities. For centuries, these vast mountains were shared by various communities, common lands supporting local livelihoods [

59], with transhumant pastoralism being the mainstay of life for the area. While, nowadays, transhumant pastoralism has declined considerably, the central part of the Southern Carpathians is one of the few regions either in Romania or in Europe where it still exists [

46], particularly in some villages from the iconic Mărginimea Sibiului in the north-eastern part of the study area [

37]. The most widespread pastoral movement is pendulation [

19,

33,

35]. The pastoral management activity practiced here is similar to what is found in Bulgaria, Poland, or France—sheep grazing in open unenclosed pastures, accompanied by shepherds [

7].

2.2. Data Collection

For the current study, data collection was based on ethnography combined with remote sensing and GIS, so as to obtain qualitative, quantitative, and spatial data. Ethnographic data collection implied participant observation and fieldwork in the central part of the Southern Carpathians for more than 30 years, with time spent by one of the authors in pastoral communities within the Parâng and Cindrel Mountains, observing how temporary dwellings are used and maintained, what the daily practices are, discussing with local farmers, elders and shepherds about the practices, pastoral traditions, advantages, and hardships. Although ethnographic data are highly relevant, they cannot explicitly contribute to a thorough mapping of temporary dwellings. This study introduces a methodological contribution by transforming qualitative knowledge into a comprehensive geospatial dataset, by integrating multiple cartographic sources and field verification.

The main cartographic sources used for the current study include high-resolution orthophotos, topographic maps of Romania at a scale of 1:25,000, Google Earth satellite images and Corine Land Cover (CLC) seamless vector data version 13 (European Commission program to Coordinate Information on the Environment).

High-resolution orthophotos, scale 1:5000, published by the National Agency for Cadastre and Land Registration (

https://www.ancpi.ro/pnccf/ accessed on 4 July 2019), for the 2008–2018 period were used for the primary acquisition of data (

Figure 4). Their main advantage for mapping settlements stems from the fact that they provide a geometrically corrected, uniform-scale aerial image, enabling spatial analysis; as a result, they have been widely used in many fields [

60]. Topographic maps of regional and/or national areas continue to be significant products in the era of digital cartography [

61]. CLC data constitute a widely used dataset among researchers in geography, remote sensing, and numerous other disciplines with varied research objectives [

62], since CLC data contribute to monitoring settlement dynamics, land fragmentation, ecosystem mapping, and assessment [

63]. With a rather high diversity of CLC land classes (38), CLC data represents a solid basis for settlements mapping research [

64].

During this initial stage, two steps were taken: digitizing shelters and sheepfolds from 1:5000-scale orthophotos and topographic maps. Ambiguous features were registered for ground validation/field check. In case of poor visibility, 1:25,000 topographic maps were used, and compared with field data or satellite images.

Our methodological approach relying on manual interpretation supported by field validation for mapping temporal dwelling was driven by the need to ensure the highest possible positional accuracy when mapping small, diverse, and informal temporary structures. Within the study area, shelters differ widely in size, building material, and visibility, being often partially concealed by vegetation and used only seasonally, making automated extraction methods less reliable at present. Under these conditions, manual interpretation remains the most dependable means of producing the first complete and validated geospatial inventory of such features. However, we do acknowledge that although manual digitization ensures high accuracy, it is very time-consuming, which is a considerable shortcoming. Automated techniques, including deep learning and object-detection methods, offer a promising avenue for future work. As a subsequent step, the dataset we have generated can serve as a strong foundation for training and validating these models.

Several limitations stemming from the input sources had to be addresses, namely scale and temporal mismatch for 1:5000 orthophotos and topographic maps. The present study employed a comprehensive inventory and spatial localization of sheepfolds and summer shelters using a single layer for each. This approach encompasses in several areas both older-generation settlements digitized from topographic maps and modifications that occurred after Romania’s accession to the EU (2007), with post-2007 digitization based on available orthophotos. This common spatial footprint approach was adopted to provide a general overview of temporary settlements over time, rather than focusing solely on those in continuous seasonal use, considering that some older settlements can be reactivated at any moment and exhibit pronounced temporal dynamics, as observed by the authors in the field over the past 30 years and throughout the successive digitization processes.

The level of utilization may fluctuate substantially over a decade and cannot be inferred from existing cartographic sources, nor can the structural condition of the settlements be assessed from them.

In the case of sheepfolds, a map showing only active ones would be valid solely for the year of field observation and would require additional data regarding the leasing of associated pastures. This temporal variability is primarily driven by the dynamic process of pasture leasing managed by local authorities (UATs), with frequent changes such as new lessees, fluctuations in livestock numbers, or new pasture concessions awarded through auctions. Larger farmers, supported by EU subsidies for livestock and pasture management, possess more efficient means to renovate and reactivate abandoned sheepfolds, sometimes converting them into ecological sheepfolds. Improved accessibility via newly constructed forest roads further contributes to the reactivation of some sheepfolds and shelters; however, unauthorized road construction is one of the most concerning phenomena in mountain areas, including Natura 2000 sites, with profound negative impacts, as documented through long-term discussions with local residents and farmers.

For summer shelters, usage patterns are similar. Older shelters, particularly those not heavily deteriorated, can be reactivated through sale to other farmers or, in some cases, integrated into the tourism circuit.

The limitations of this cumulative mapping approach are related to the geographic reality of both active and inactive structures in terms of seasonal occupancy, some of which are highly deteriorated.

Regarding the interpretation bias in digitizing [

65], field verification was carried out using the methodology detailed by Olofsson et al. [

66] and Stehman [

67] regarding sampling for field validation, with reference labels to be used in the field using a LUCAS-style protocol [

68], adapted for the mountainous terrain. Validation points were collected, accounting for approximately 10% of all identified dwellings from each type. Sampling followed a stratified design considering the three altitude classes, land-use types (hay meadows, pastures, transitional woodland) and visibility (clear/ambiguous) of features in orthophotos. Selected points were in the categories: shelter, sheepfold, abandoned structure, or misidentified object. Field validation was extensive, but inevitably selective due to terrain.

Although temporal inconsistencies exist between different time periods’ orthophotos, high-altitude pastoral settlements in the Parâng–Cindrel massif exhibit stable spatial locations over time. Data were therefore compiled using a common spatial footprint approach, including both active and potentially reusable abandoned sites, as field observations confirmed that new structures are typically built on the same locations as older ones. The digitized dataset provides a reliable representation of pastoral infrastructure over the analyzed period, suitable for mapping and density visualization purposes. It captures both active and potentially reusable abandoned sites and reflects the persistent spatial distribution of high-altitude pastoral settlements.

Our approach allowed for a reliable validation of the digitized dataset.

2.3. Data Processing

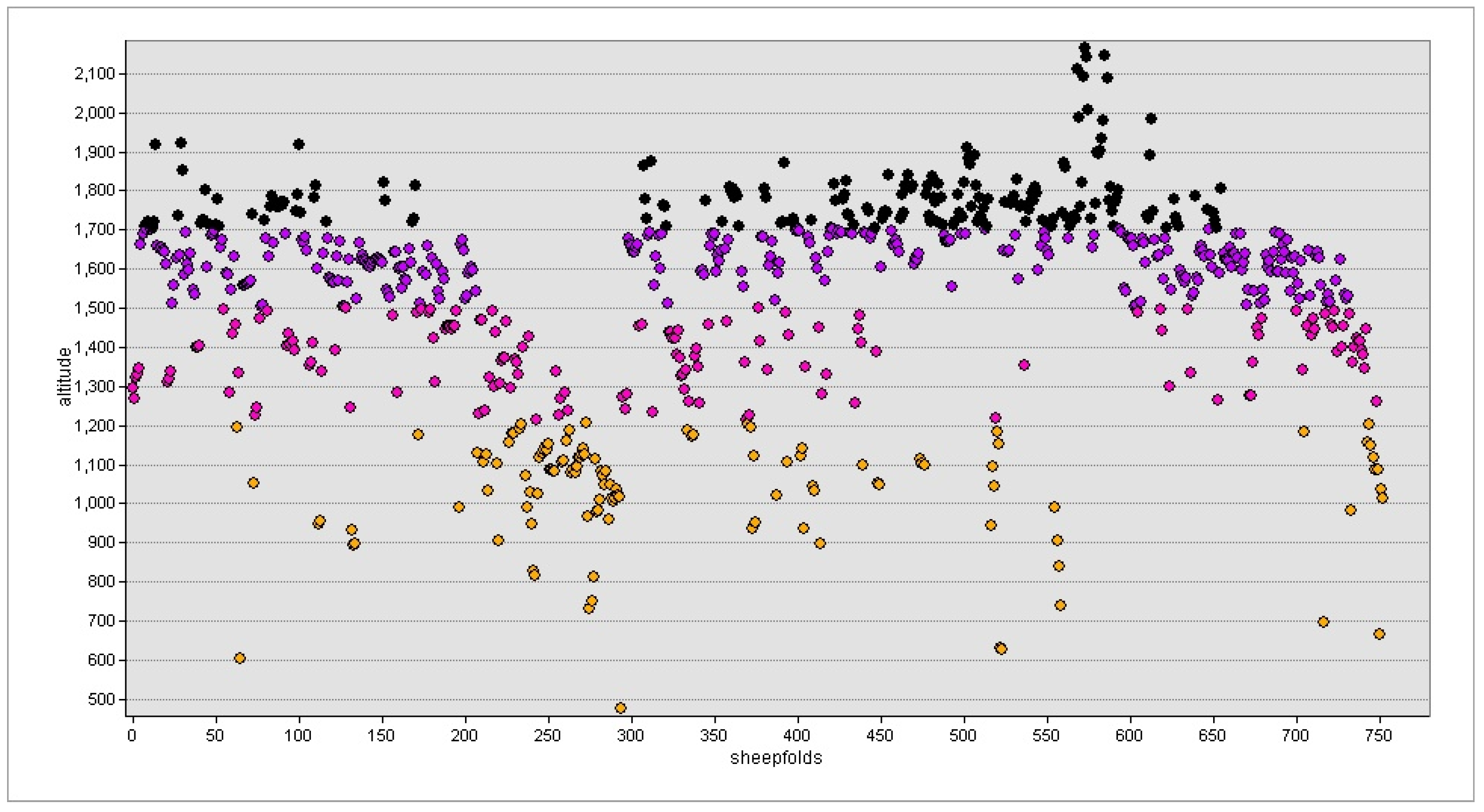

Dwellings (sheepfolds and shelters) were compiled by digitizing point features from high-resolution orthophotos (2008–2018), 1:25,000 topographic maps (1970s–1980s), and field verification undertaken in 2023. The dataset includes both active and historically (potentially reusable) sites; the sheepfold and shelter locations were stored as two standardized shapefile layers, ensuring spatial consistency across sources. Furthermore, each point dataset was visualized through a dedicated cartographic representation. The sheepfolds were mapped against a hypsometric DEM background, with elevation classes corresponding to their altitudinal classes. In contrast, the shelters were displayed on a thematic land-use background derived from CORINE Land Cover, highlighting their spatial relationship with agricultural terrain.

Altitude values were extracted from a 25 m resolution digital elevation model de-rived from SRTM data and validated against 1:25,000 topographic maps. Elevation extraction used the Spatial Analyst—Extract Values to Points in ArcMap 10.8, producing for each point (shelter and sheepfold) an elevation attribute.

The shelter and sheepfold point datasets were further processed to generate altitudinal distribution plots, illustrating the elevation characteristics of these pastoral features. These visualizations are displayed as separate figures, thematically linked to their respective spatial maps.

Spatial density patterns of the dwellings were analyzed using Kernel Density implemented in ArcMap Spatial Analyst. KD rasters were generated separately for the two types of dwellings.

The density raster extent covers the minimum bounding rectangle of all points in the X (easting) and Y (northing) directions, resulting in NoData values outside the area where dwellings occur. Kernel density was performed on the point datasets using a 300 m output cell size, ensuring sufficient spatial granularity for meso-scale visualization.

Given the large number of shelters (almost 5400), to enable clear identification of areas of high concentration, a 10,000 m search radius was selected, while for the less numerous sheepfolds (around 750), the search radius was set to 5000 m, representing the inferred spatial influence of each sheepfold point based on traditional herd-mobility patterns. This parameterization follows common KD implementations in spatial point-pattern analysis, where the bandwidth reflects the functional activity range of the phenomenon being modeled.

The spatial analysis of temporal pastoral settlements was carried out in ArcGIS Desk-top 10.8, employing functionalities from Data Management, Spatial Analyst, and Conversion Tools, together with raster-based geoprocessing. All operations were conducted within the Stereo 70 (EPSG:31700) projected coordinate system to ensure positional accuracy and consistency across datasets.

Although methods were tailored considering the specific social, cultural, and environmental conditions of the central part of the Southern Carpathians, the workflow—interpretation of high-resolution orthophotos, field validation, and GIS-based spatial analysis provide a replicable methodological framework for other alpine pastoral systems, particularly in regions characterized by dispersed temporary dwellings, seasonal mobility of animal stock, and limited official datasets.

4. Discussion

This paper focuses on the inventory and distribution of temporary pastoral dwellings, namely shelters and sheepfolds, which are highly relevant for the traditional livelihoods of the rural population and the economy of the study area on one hand, and sustainable agricultural practices and land use on the other hand.

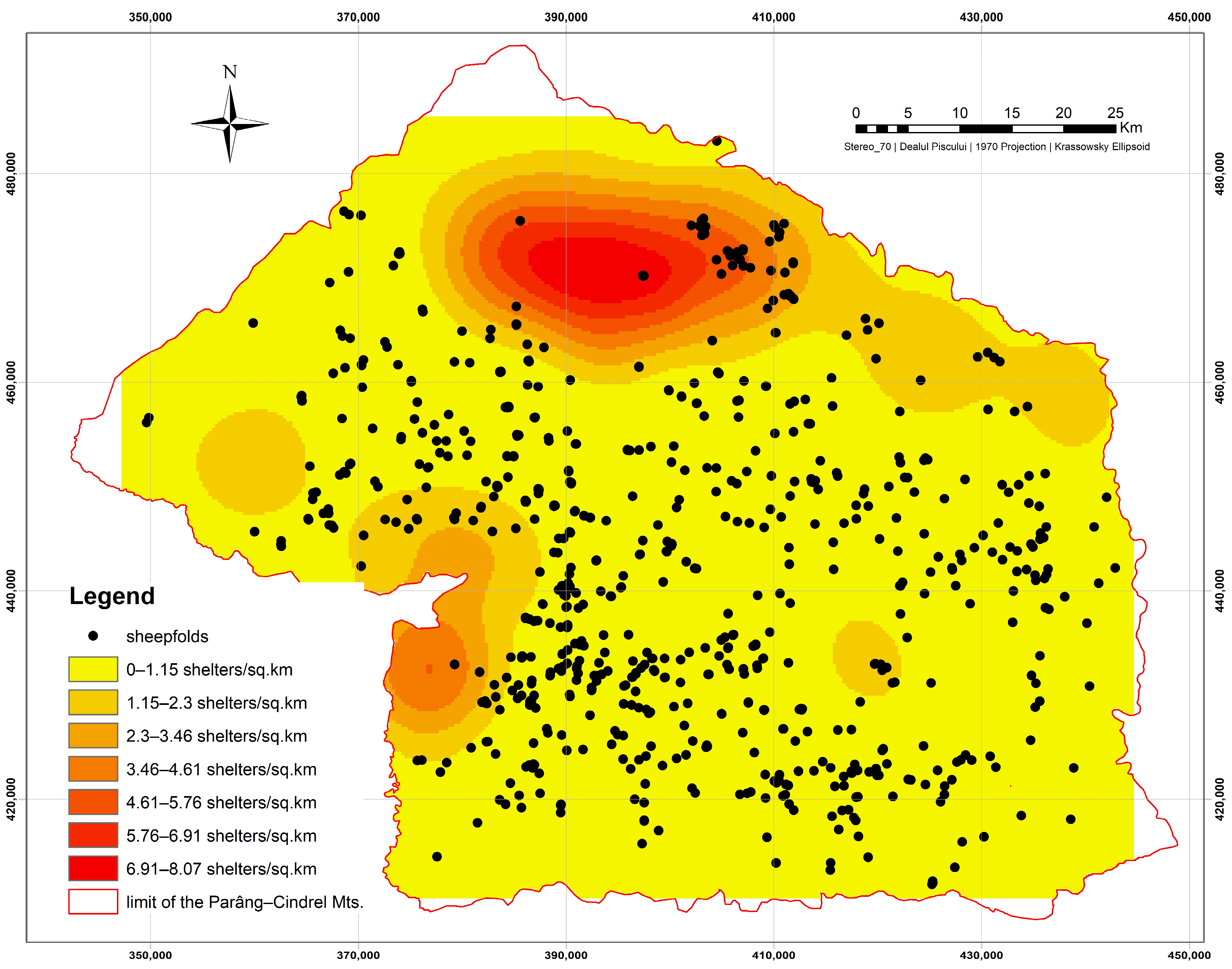

The first research question addresses the clustering of pastoral settlement and the current results highlight the fact that shelters are definitely clustered: the largest cluster, with the highest density of shelters (more than 8 shelters/km2) is found in the northern part, within the Șureanu-Cindrel Mountains, where the largest areas with pastures and grasslands are also found. A second high-density cluster is located on the south-western area (next to the Jiu valley), although it is smaller. Sheepfolds are less clustered than shelters, but their spatial distribution still highlights a continuous north–south and west–east strip with high density within the central-western part of the study area. They also form a significant local cluster in the north-east. Thus, their distribution is not even; it shows a particular pattern related to land use, altitude, and accessibility.

Regarding the second research question, specific traditional pastoral practices produce distinct spatial patterns. Pastoral mobility is directly linked to vertical distribution of temporary dwellings: for spring grazing, mainly shelters at lower altitudes (850–1250 m) are used, while for summer grazing, sheepfolds at higher altitudes (above 1700 m) are fundamental. Shelters usually cluster around productive grasslands, with northwestern areas having the highest shelter density. Accessibility as well as historical ownership patterns—forest roads, land restitution, pendulation patterns—considerably influence where pastoral dwellings persist or decline.

There is also a direct correlation between land use and the distribution of pastoral settlements: shelters are usually clustered in areas with natural grasslands and hayfields; historical land-use changes have also impacted this distribution, with the traditional forest cleanings during the 19th–20th centuries explaining today’s pasture belts and location of pastoral dwellings. Sheepfolds are generally found near the upper forest limit which provides for wood and are closely connected to water sources’ availability.

The paper maps the temporary dwellings in the five historical pastoral areas within the central part of the Southern Carpathians, namely Marginimea Sibiului (north-est), Luncani Platform (north-west), Petrosani (south-west), Oltenia at the Mountains’ Feet (south), and Lovistea Country (east). The highest density of shelters is found within Sureanu-Cindrel Mountains, where the longstanding historical traditional pastoral zones such as Marginimea Sibiului, Sebes, and Luncani are found. The north–south and west–east strips of sheepfold correspond to formal transhumance routes and traditional grazing plateaus, thus confirming the third research question that the current spatial distribution is consistent with the traditional pastoral areas. Still, there are some changes that we acknowledge.

For the last 20 years, there has been an obvious decline in the number of sheepfolds, estimated at 22–25%, as well as abandonment of the associated pastures and shelters of about 18–20%. Sheepfolds that are not easily accessible by road, and which are generally located above 2000 m high, are the first to decline. Also, those managed by a small number of associated sheep owners are also greatly decreasing, with the owners gradually giving up raising animals. This is consistent with situations reported in Maramureș [

19] or Rucăr-Bran [

69], which are also important traditional pastoral regions in Romania. We analyzed this decline for the last 18 years (beginning with 2007 when Romania became part of the European Union), a period in which we have records reported by the Agency for Payments and Intervention for Agriculture (APIA) [

70], the agency that manages community subsidies. The result for the rural settlements in the central part of the Southern Carpathians (27 LAUs), during the mentioned period, was an average decrease of 38% for the sheep herd and 11% for the cattle herd within the study area. Data were compiled for individual animal owners receiving community subsidies, excluding large farms with one or more shareholders. There are, however, large farms, which have considerably developed in the last two decades, which compensate for the deficit by relocating from the mountainous area to the hilly and plain areas where the yield is higher. These large farms maintain Romania as one of the most important exporters of live sheep in the European Union.

While the current study focuses particularly on shelters and sheepfolds as a particular type of land use and traditional agriculture activities, it supports findings from studies focusing on land use in the mountainous area. Abandonment of agricultural land, including grassland, has been documented throughout the Carpathians, both in Romania [

18,

19] as well as Poland [

16,

32], Slovakia [

6,

28], or Ukraine [

71]. The land around the abandoned sheepfolds is affected by invasive ruderal species (e.g.,

Rumex alpinus) (

Figure 10). Their territory is gradually occupied through expansion by

Pinus montana (

Figure 12). This poses great threats for conservation and biodiversity of grasslands. The sustainability of the pastures and sheepfolds in the study area faces a medium and long-term challenge through the abandonment of large areas of meadows and pastures, the floristic composition of which is currently affected (and it will be more so in the future) by ruderal and invasive species; the stratified structure predominantly made up of grass species (

Poaceae) will be replaced by associations of shrubs and subshrubs (including invasive species). However, in the short term, mountain agriculture still holds out, but land use is maintained in a fragile balance between tradition, sustainability, and abandonment. Only the most conservative communities in the region, who do not want to give up the tradition of raising sheep and cattle, maintain the biodiversity, composition, and structure of the meadow phytocenoses around the settlements through regular mowing. In these communities, one can experience the local lifestyle (agritourism) and they are also the ones that still have a viable rural economy that keeps agro-mountain food products on the market.

Although the number of small herds has been gradually decreasing, that is not to say that there is no grassland degradation due to overgrazing. On the contrary, previous studies have highlighted that there is a substantial overlapping of mountain grassland area with overstocking and overgrazing, especially in the central part of the study area [

41] and even in protected areas that are part of the Natura 2000 network [

43].

The abandonment of traditional practices and pastoral activities has a negative impact not only from the point of view of biodiversity, but also from the local and regional identity stance. Pastoralism is deeply ingrained in the Romanian culture [

34] and shepherds are a central figure for the Romanian identity, having a particular place in the history and culture of Romania and their identity still carrying a degree of influence in society [

72]. They form a ‘specific social-historic institution with a unique and culturally particular set of practices and history’ [

46]. Within the study area, they bear different appellatives (within Mărginimea Sibiului, they are called

mocani, Gebirgswalachen’ or ‘Die Tzuzuianen’ [

37]; in the south-western part, along the Jiu valley, they are called

momârlani [

73]). In Jina, one of the iconic villages for sheep breeding not only from the study area, but from the entire country, this traditional activity is the most important economic activity, with a major role for keeping the community together [

34]. Shepherds from the western part of the study area, called momârlani, greatly value land, animal stock, and their knowledge of traditional occupations, making great efforts to remain sheep breeders despite other more profitable alternatives [

73]. Unfortunately, the Romanian shepherd has gradually become an economically and socially marginal figure [

72] due to several reasons: on one hand, aging of shepherds, generation gap—young adults being reluctant to still practice traditional shepherding [

73]; on the other hand, the need to adapt to a competitive market with new and constraining rules also triggers changes. Just like in other well-known Romanian pastoral areas, the shepherds, once called

stăpânii de munte (literally ‘mountains owners’), struggle to find employees that are dedicated and familiar with the activity [

69].

However, large farms were established in the study area, which are better adapted to coping with regulations and surviving in the market. The changes occur against the backdrop of the impoverishment of the population in a large part of the rural mountainous area, a population that has switched to a subsistence economy due to the accelerated development of much more profitable large farms, the high increase in imports of dairy and meat products (local products are harder to sell), and the migration of young people to cities in search for better paying jobs.

While population aging and youth out-migration remain the dominant drivers of land abandonment in high-altitude pastoral areas, these demographic processes interact with national and EU-level policy frameworks that influence the viability of mountain farming. Romania’s mountain agriculture struggles to benefit from EU CAP payments, due to restrictive eligibility criteria and demanding administrative requirements. Policy support is often perceived as insufficient to counterbalance the structural socio-demographic decline. Generally, local-level policy focus is more oriented toward tourism than strengthening pastoral infrastructure or generational renewal.

Changes observed within the Parâng-Cândrel Mountains mirror broader pastoral transformation across the Romanian Carpathians. For example, in Maramures, Ivascu&Iuga [

19] report a similar decline in traditional sheepfolds and seasonal dwelling as a result of population aging, land restitution and decreasing economic viability of small herds. Just like in Parang-Cindrel Mountains, Maramures also exhibits a mixed pattern of localized clustering of high-altitude sheepfolds and gradual abandonment of less accessible structures. However, unlike our study area, in Maramures, many villagers switched sheep breeding with cow breeding following subsidies from APIA.

Likewise, within Rucăr-Bran corridor, which is another well-known pastoral region, David [

69] highlights a reduction in active sheepfold and increasing vegetation encroachment around abandoned pastoral structures, mirroring our findings. In both regions, accessibility plays a key role: high-altitude sheepfolds, with poor accessibility, are the first to be abandoned.

These parallels suggests that the processes identified in the southern Carpathians reflect wider transformations across the Romanian Carpathians and that the pastoral systems face similar pressures. Beyond Romania, a similar process of pastoral contraction has been documented in the Polish and Slovak Carpathians, which situates the Parang-Cindrel Mountains within a broader European context in which traditional mountain pastoralism faces demographic and economic pressures.

Limitations. This study has several limitations, including the reliance on manual digitization and temporal inconsistencies among input datasets. The paper provides a static snapshot of temporary pastoral dwelling in the central part of the Southern Carpathians, which may limit broader generalization and also make it impossible to assess the conservation or renovation status of individual structures, as well as the difficulty of identifying temporary interruptions in pastoral activity at certain sites or the reactivation of older ones—limitations that are particularly evident in the case of sheepfolds. Improved accessibility via newly constructed forest roads has enabled the reactivation of some sheepfolds and shelters, supporting the continuation of traditional pastoral practices. Nevertheless, unauthorized road construction remains a major concern in mountain areas, including Natura 2000 sites, causing significant environmental impacts. Long-term discussions with local residents and farmers highlight these issues, emphasizing the need for careful planning and regulation to ensure that increased accessibility does not compromise the conservation of fragile mountain ecosystems.

Secondly, spatial patterns were examined using density, altitudinal range, and clustering to address the first research question focusing on the regional distribution of temporary dwellings. Nevertheless, several landscape pattern metrics such as aggregation index and landscape fragmentation index could further quantify spatial configuration and would complement the results presented here. The database created by the current study offers the possibility for future analyses that employ these metrics, to have more formal quantification of pastoral dwellings.

This paper contributes to the existing literature by providing the first inventory of temporary dwellings in the central part of the Southern Carpathians, focusing on the number and location of shelters and sheepfolds, directly related to traditional mountain agriculture that has shaped the landscape while sustaining biodiversity and rural economies. The novelty of this research lies in its methodological framework. While earlier studies documented pastoral traditions, mobility patterns, and cultural practices through ethnography or historical reconstruction, they did not produce a spatially explicit representation of the built pastoral infrastructure. By integrating high-resolution orthophotos, historical maps, field campaigns, and GIS-based spatial modeling, this study provides the first quantitative evidence and detailed map of how temporary pastoral dwellings are distributed across elevation zones, land-use types, and morphological units.

The results of the current study have direct policy relevance for the management of protected areas and local administrations as well as tourism and heritage stakeholders. The Parâng-Cindrel Mountains partially overlap three national parks, two natural parks, and several Natura 2000 sites, with almost half of their surface being protected. However, management plans of protected areas or even municipal spatial plans rarely, if ever, have thorough knowledge about the number, clustering, and proper functioning of these temporary dwellings. Their spatial distribution (especially sheepfolds) may also influence the water quality near springs. Hence, a proper inventory and typology may contribute to better zoning and seasonal access.

Findings can also be used by Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) measures to support farmers in this particular rural area (eco-schemes, income support, development initiatives, waste management).

The central part of the Southern Carpathians, with rich natural landscapes and biodiversity, iconic ethnographic zones directly linked to traditional pastoral activities, a particular cultural heritage, and a large number of temporary dwellings that dot the mountains, are the key elements that could support a smart regional development, linking cultural landscapes, pastoral livelihoods, local products, and tourism. Heritage trails capitalizing on these temporary dwellings and local products (including branded quality schemes) could greatly benefit local communities, without degrading sensitive habitats.

5. Conclusions

This study focused on the inventory and distribution of temporary pastoral dwellings—namely shelters and sheepfolds—which are highly relevant both to the traditional livelihoods of the rural population and to the economy of the study area, as well as to sustainable agricultural practices and land use. The study documents the existence of more than 5400 shelters and over 750 sheepfolds in the central part of the Southern Carpathians. The research provides the first comprehensive inventory of non-permanent settlements in the Parâng–Cindrel Mountains, the analyzed area representing almost 40% of the total surface of the Southern Carpathians and constituting the most favorable mountain group for livestock-based pastoralism.

Core Findings and driving factors. The distribution of temporary settlements is shaped by land-use patterns, confirming that shelters are intrinsically linked to natural grasslands and to traditional yearly pastoral practices, while sheepfolds are generally situated at the upper forest limit, providing access to firewood, in areas with abundant water sources and in close proximity to alpine pastures. Shelters emerged and multiplied as a result of a combination of key factors, including terrain accessibility, soil characteristics, the presence of water (rivers and springs), vegetation cover, and changes in land ownership. Their simple morphostructure reflects a subsistence economy based on pastoral activities and the cultivation of small plots for household consumption.

The main driving factors shaping the distribution patterns of shelters are, first, the differing pastoral traditions and the varying extent of transhumance in the six distinctive regions. A second explanation for the distribution pattern is the unequal size of sheep and cattle herds owned by local communities, with the northern and especially the north-western (Transylvanian) areas holding the largest livestock numbers. More than 80% of the analyzed shelters are located at elevations between 900 and 1200 m.

The results highlight two clear clusters of shelters: (1) the largest cluster, with the highest density (over 8 shelters/km2), is located in the northern sector, within the Șureanu–Cindrel Mountains (Mărginimea Sibiului-Sebeș Valley), which also contain the most extensive hayfield areas; (2) a second high-density cluster is found in the south-western area (near the Jiu Valley), although it is smaller. Sheepfolds are less clustered than shelters.

The spatial distribution of sheepfolds reveals continuous north–south and west–east high-density bands in the central-western part of the study area and another significant local cluster in the north-east. The study further identifies the spatial patterns of sheepfolds (altitudinal distribution and density), grouped into three elevation categories.

The main driving factors influencing the distribution of low-altitude sheepfolds (467–1207 m) include the insufficient availability of hayfields required for shelter-type dwellings—resulting in the interspersion of shelters and sheepfolds (less than 10% of the total)—and the possibility for small flocks to remain in these areas.

Medium-altitude sheepfolds (1208–1500 m) are generally located within the coniferous belt and represent the most developed habitation structures (as summer grazing with entire families is common, requiring substantial amounts of firewood and building materials). They are more frequent in forested areas with numerous clearings or where forests were converted to pastures in the last century, representing around 15% of all sheepfolds. The majority of sheepfolds (over 75%) are high-altitude structures (1501–2165 m), situated at the upper forest limit (1500–1750 m) or higher, in rocky areas. Their presence is explained by easy access both to wood resources and to alpine pastures. Sheepfolds located in rocky terrain are generally used for separating milk-producing flocks from non-milking animals (dry ewes, rams). In terms of density, the highest values recorded in the central Southern Carpathians occur in the Șureanu, Parâng, and Căpățâna massifs, with a maximum of 0.86 sheepfolds per km2.

Temporary pastoral dwellings emerged and multiplied due to the combination of key factors, namely accessibility of the terrain, soil characteristics, water (rivers and springs), vegetation cover, and changes in land ownership. The simple morphostructure expresses a minor economy based on pastoral activities and cultivation of small plots for family consumption.