1. Introduction

Accurate and reliable indoor positioning on smartphones serves as a key point for a wide range of applications, including path planning, navigation, and emergency response [

1]. However, due to limited access to global navigation satellite system (GNSS) signals, indoor localization accuracy often deteriorates substantially, resulting in low positioning reliability. Therefore, developing robust indoor localization solutions that can operate effectively without GNSS signals has become a research focus.

Indoor infrastructure-based data sources, such as ultra-wideband (UWB) [

2], Wi-Fi [

3], low energy bluetooth (BLE) [

4], and beacons [

5], can fill the gap of inaccessibility of GNSS signals, providing relative distance and angle measurements for smartphones to estimate motion. These solutions are stable and accurate but require site surveys and continuous access to the data sources. An alternative approach to the previously mentioned techniques is to utilize perception-based navigation solutions, such as vision-aided and light detection and ranging (LiDAR)-aided positioning systems. These solutions can extract both semantic and geometric features and track the user’s trajectory [

6]. However, the positioning performance is often constrained under challenging environmental conditions, such as varying illumination or low-texture surfaces.

In contrast, inertial measurement units (IMUs), which comprise tri-axial accelerometers and gyroscopes (with optional magnetometers), are equipped on every smartphone and can provide continuous, low–latency measurements. By capturing motion data, IMUs are regarded as important sensors in smartphone-based applications. However, inertial-only estimation cannot estimate the pose accurately even in a short period of time, suffering from rapidly growing errors due to the noise integration. Pedestrian dead-reckoning (PDR)-based solutions reduce drifting by modelling human locomotion. In these methods, step detection and stride length estimation are achieved using accelerometer data, while heading values are estimated from gyroscope yaw increments. With the support of motion constraints, such as zero-velocity updates (ZUPTs), PDR approaches have been widely deployed on foot-mounted sensors. However, attaching smartphones to the user’s foot is difficult. Without the availability of ZUPT for the handheld device-based navigation, the device-to-body orientation and intrinsic parameters vary unpredictably, resulting in errors in the estimation of device’s heading and step length. Therefore, for the PDR using IMUs, non-Gaussian uncertainties should be accounted for during the estimation of step length, heading, and orientation alignment.

Due to the challenges mentioned above, particle filters (PF) are widely utilized to address optimization problems involving non-Gaussian uncertainties [

7,

8]. Further, these filters have the advantage of handling non-linear motion and observation models. While other filter-based methods, such as the Kalman Filter (KF) and its variants [

9,

10,

11], can provide positioning solutions, PFs yield more stable and reliable estimates. A long history of research has demonstrated that smartphone PDR based on PF can estimate user’s motion accurately and achieve good performance in various indoor environments [

12,

13,

14].

PF and other dynamic Bayesian networks consist of two main steps: prediction and update. In the prediction step, the poses of the particles are estimated using the measurements from IMUs. In the update step, the predicted poses are corrected. Numerous update strategies have been proposed in the past. These strategies can be categorized into two groups: wireless signal-aided updates and map-aided updates. For the wireless-signal aided approach, the distance, angle of arrival, or received signal strength of the smartphone with respect to the beacons are measured and integrated with IMU readings via PFs [

15,

16]. Improved versions of PFs with optimized resampling strategies, such as approaches in [

15,

17], have also been proposed in the past. Other works, such as [

18,

19], utilized geomagnetic signals for further improvements. In summary, integrating wireless data sources can significantly eliminate drifting; however, performance is affected by sources of errors, such as non-line of sight (NLOS), multi-path signals, and transmission power variations [

20].

Alternatively, the pose updates can be provided to a PF with the help of maps. Map-aided PF-based solutions enable the system to extract constraints and utilize them to remove particles when they move into inaccessible areas [

21,

22,

23]. Compared to other types of indoor maps (e.g., point cloud maps and voxel maps), which can occupy large computational memory, the floor plan comprises a vector-based lightweight model. Such a floor plan contains information that can be used to constrain the PFs by setting the structural boundaries. Numerous map-aided PF solutions have been proposed in the past. For example, in [

24,

25], particles that move to inaccessible areas are eliminated. In [

26], the map is improved by involving a priori information, which is represented using the human motion likelihood map. In [

27,

28], accessibility information provided by doors and walls is considered. In [

29], map-aided constraints prevented particles from crossing into inaccessible areas. These results demonstrate that involving structural information from vectorized floor maps can significantly reduce drifting in the estimated location of the user, without relying on data collected from wireless infrastructure.

Despite the mentioned progress in map-aided PF solutions, the computational cost of PF remains a challenge. Such a computational cost increases with the number of state-space dimensions. The large state-space dimensionality is a problem for PDR, since the state includes the position (three parameters), velocity (three parameters), attitude (three parameters using Euler angles), and sensor biases (three parameters for the gyroscope, and three parameters for the accelerometers). In order to reduce such a large state dimension, in PF-PDR implementation, it is assumed that the user is moving on a plane (two parameters) with only an unknown heading (one parameter) and the corresponding gyro bias (one parameter). Such a dimensionality reduction contributes significantly towards on-device (smartphone) implementation of map-aided PF-PDR. However, these assumptions can reduce accuracy. For example, estimating a reliable heading from handheld smartphones is difficult, leading to a wide particle spread. To address high uncertainty, particularly under non-linear dynamics and non-Gaussian error distributions in the state parameters, existing approaches typically employ large particle populations, which increases the computational cost.

Addressing the mentioned issue, this paper proposes a map-aided adaptive PF-PDR with a reduced state space. The improvements comprise two points. In order to address the challenges with larger particle requirements, the developed method utilizes a cross-entropy distance-based test to reduce the number of the particle. In this approach, the distribution of the particles is compared to a Gaussian with the help of cross-entropy distance. If this distance is smaller than a certain threshold, the number of particles is reduced. This reduction is only possible if particles are approaching a Gaussian distribution; thus, eliminating the requirement for a large number of particles to represent multi-modal distributions. The second contribution of this paper is the dimensionality reduction in the user’s navigation state while preserving the accuracy. This reduction is achieved by estimating the user’s angular rate on a virtual plane parallel to the ground. With this approach, it becomes possible to estimate the user’s trajectory in 2D along with the heading. The measurement projection to this virtual plane is performed by levellng gyroscope coordinate frame using accelerometer readings. Since accelerometers can estimate roll and pitch from the gravity vector at the current epoch, this leveling is independent for each gyroscope measurement. Summarizing the discussion above, the contributions of this paper can be summarized as follows:

- (1)

Cross-entropy test for particle number reduction. A particle reduction based on cross-entropy distance between the particle distribution and Gaussian is proposed. This strategy significantly reduces the number of particles while preserving the accuracy and improving the computation efficiency.

- (2)

Particle dimensionality reduction. Computational cost of a PF relies on the state-space dimensionality and in order to reduce this space, we only use the heading in the attitude representation. It is shown that such a reduction in dimensionality can be achieved without accuracy loss, using sensor levelling.

- (3)

Real-world tests. Experiments are implemented on a real-world dataset collected using a smartphone, demonstrating the accuracy and robustness of the proposed solution.

2. Method

In this section, the proposed map-aided PDR framework is described in detail, with a particular focus on how the adaptive PF enhances efficiency through the incorporation of map constraints. The developed PF framework, does not assume any initial location or heading for the user. The initial location of the particles are sampled using the boundary of the 2D map where particles are selected at fixed intervals. Starting positioning tracking, the proposed method employs a cross-entropy criterion to switch to a reduced PF. Switching occurs if the distribution of the particles closely resembles a Gaussian with a user-defined standard deviation. In the switching phase, the particles are sorted according to their weights, and the particles with the highest weights are selected. The remaining particles are discarded for the rest of the trajectory estimation to reduce the computational cost of the algorithm.

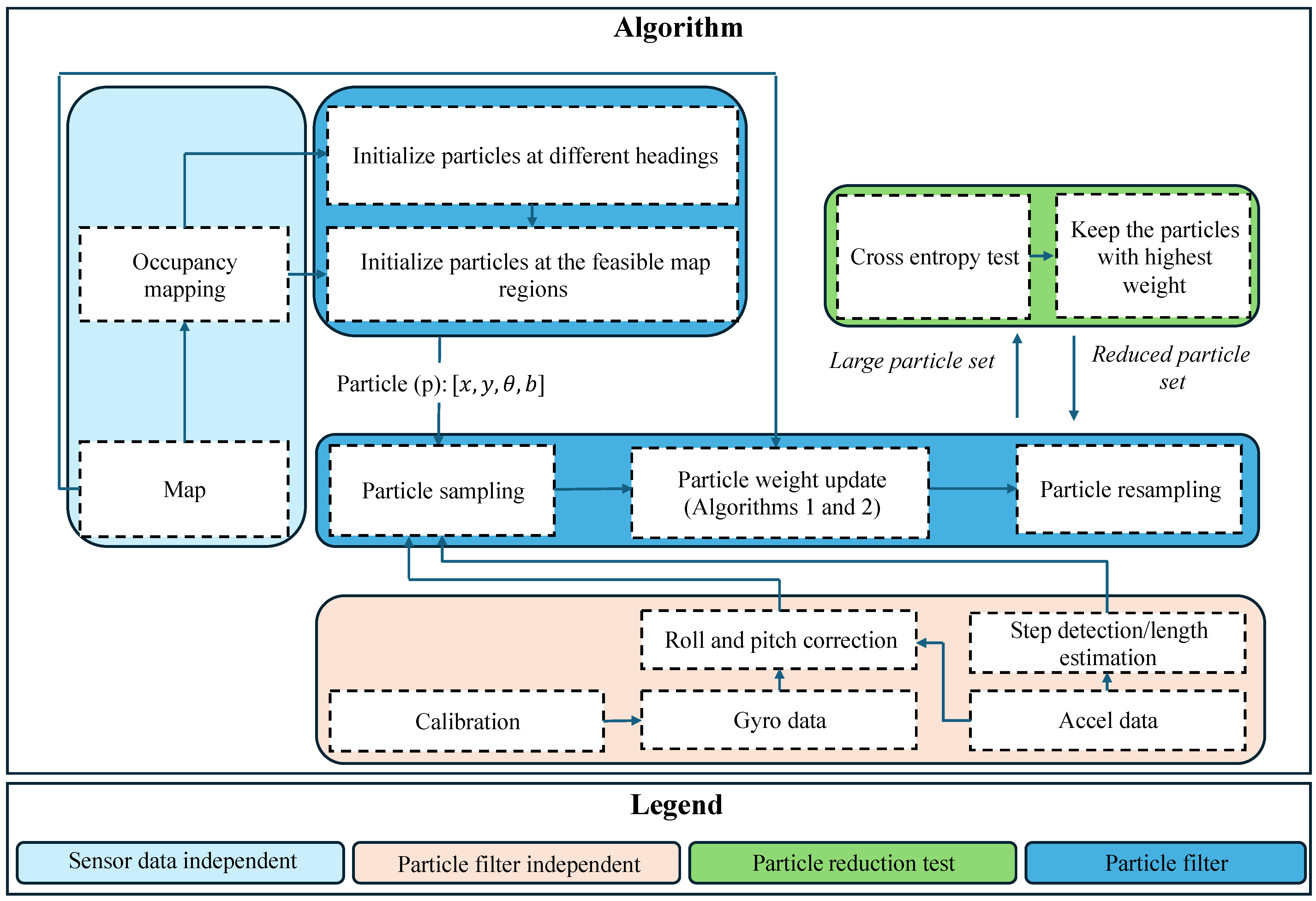

Figure 1 shows an overview of the developed adaptive PF-PDR algorithm. PFs can suffer from a phenomenon known as particle degeneracy. Particle degeneracy occurs when most of the weight of the particles is concentrated on a few particles, while many particles carry weights close to zero. This large discrepancy in particle weights arises due to the stochastic nature of PFs [

30]. To eliminate or reduce particle degeneracy, particle resampling strategy has been introduced in the literature [

30]. In the resampling step, new particles are drawn based on the weights of the previous particles. In this process, particles with higher weights are more likely to be selected again, while particles with lower weights are more likely to be eliminated. In this study, we have used a multinomial resampling strategy for particle filter implementation [

31].

The PF-PDR developed includes four states. These states are the position in

and

directions of the map, heading

with respect to the map coordinates, and bias of the gyroscope

. It is common to include all three attitude parameters (roll, pitch, and heading) in a typical implementation of PDR. However, this can substantially increase the dimensionality. Instead, in the proposed approach, the necessary roll and pitch corrections are applied using the accelerometer data before passing the gyroscope readings to PF. After gyroscope axes levelling, only the angle corresponding to the heading direction is utilized. This heading correction can be seen as particle filter independent module in

Figure 1. The heading correction is based on the current accelerometer measurement. This measurement is independent of the filter predictions. Thus, such a correction does not require any information from PF-PDR algorithm, and the state vector can be kept at lower dimensions by excluding direct particle sampling of roll and pitch. The state vector (

) is shown as follows:

where

denotes the index of the particle. In a PDR problem, user’s displacements in the

x and

y directions are not independent of each other and the estimated heading. The displacements in

x and

y are related through the step length (

). To reflect this in the estimation, sampling is first applied to the step length. The step length and the current heading estimate are used to determine the user’s plausible next position. This approach takes advantage of the correlation between the

x and

y directions, avoiding the need to sample each direction independently. Further, the proposed algorithm samples the gyroscope bias error. For low-cost MEMS gyroscopes, bias instability is a well-known issue. It is often addressed with ZUPTs; however, in our study, we assume no such periods are available. Instead, the map-matching algorithm successfully updates the gyroscope bias by providing a reliable correction to tracked bias. The estimated bias is then used to update the raw gyroscope measurements and subsequently refine the heading estimation. The particle resampling process is illustrated in the particle filter module in

Figure 1. The corresponding equations for position estimation are shown below:

where the subscript

denotes an epoch. An epoch is an interval of time where at least one measurement is obtained from accelerometers and gyroscopes. Since measurements do not correspond to the same timestamp, an interpolation is often required. In Equation (

2), the time difference between two consecutive epochs (

k and

) is denoted as

. In Equation (

3) the symbol

denotes the noise. It is assumed that the noise is a Gaussian distribution (

) with a standard deviation of

. If user does not take a step in the current epoch,

is set to zero and only the heading update applies.

The predicted position and heading estimation of the particles are matched with the map for the weight update. The map matching module is activated when the user takes a step. If a user step is detected, the algorithm first finds particles falling outside of the map and assigns a low weight to these. The weights (

) are normalized to one after this step. The pseudocode of this step is shown in Algorithm 1.

| Algorithm 1 Map Matching and Weight Update Triggered by Step Detection. |

- Require:

Set of particles , map boundaries, step detection flag - 1:

if a step is detected then - 2:

for to N do - 3:

if () is inside the map boundaries then - 4:

- 5:

else - 6:

- 7:

end if - 8:

end for - 9:

// Normalize weights - 10:

- 11:

for to N do - 12:

- 13:

end for - 14:

end if

|

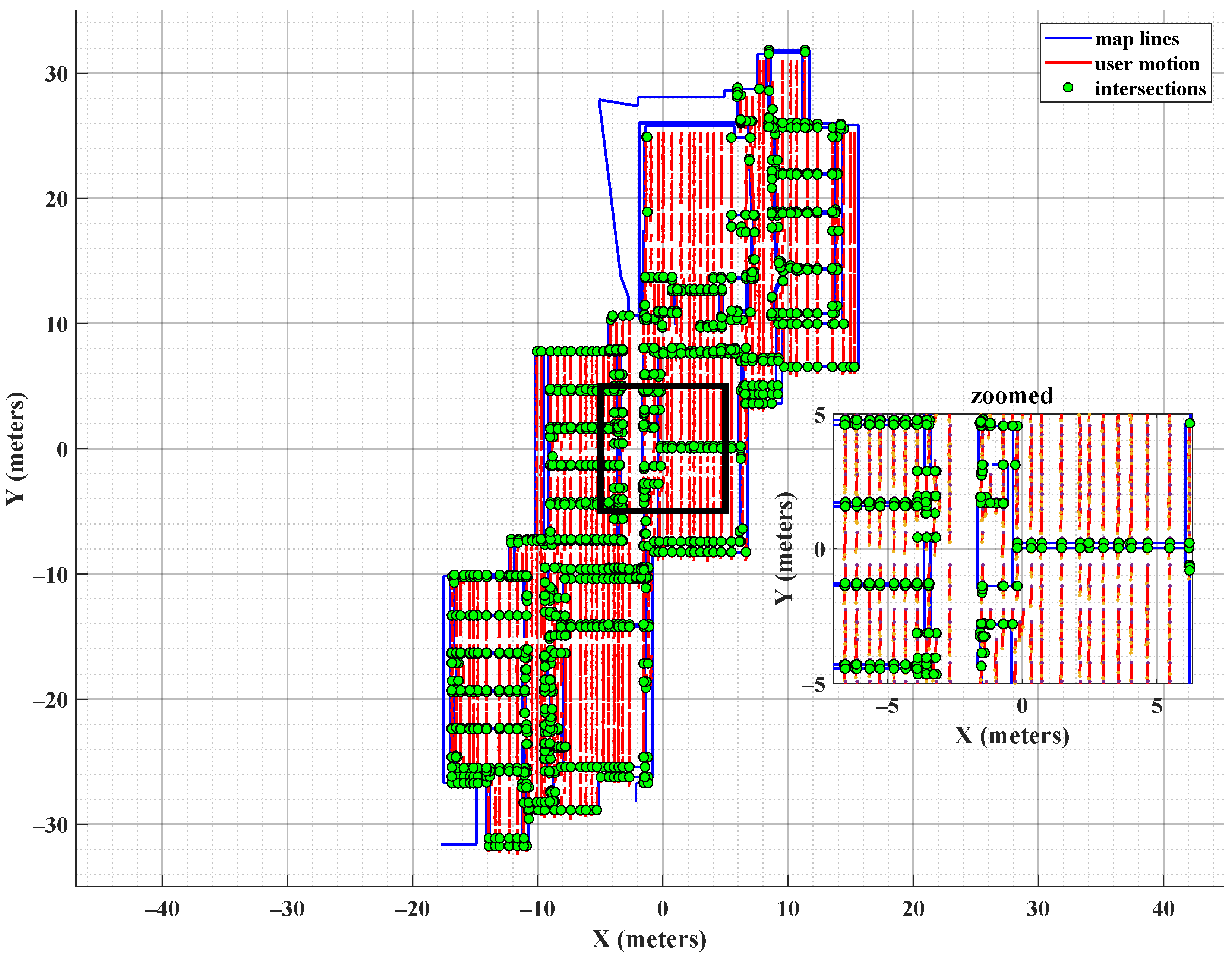

After the first update, a second update is achieved using the lines in the map. In this update, a line-segment is first drawn from the previous location of the particles to their current location. If this line crosses any map line, the corresponding particle receives a very low weight. Similarly to the previous step, the weights of the particles are normalized to one. Pseudocode of the second update is provided in Algorithm 2, where

h corresponds to the epoch of the previous step.

Figure 2 illustrates the intersection of the user’s step with the map-lines as green points (here, the user’s step is aligned with negative y-axis). The corresponding particles are assigned to a lower weight.

| Algorithm 2 Line-Crossing Based Map Matching and Weight Update. |

- Require:

Set of particles , map lines - 1:

for to N do - 2:

- 3:

- 4:

line crossing - 5:

if cross any map lines then - 6:

- 7:

else - 8:

- 9:

end if - 10:

end for - 11:

// Normalize weights - 12:

// Normalize weights - 13:

- 14:

for to N do - 15:

- 16:

end for

|

At each iteration, the distribution of the particles is compared to a Gaussian using cross entropy criterion. The cross entropy (

) of the two distributions is calculated using the equation shown in the following, where the distribution of a PF is represented with

and the Gaussian distribution is sampled as

.

While the distribution

is sampled from a Gaussian, the mean of this distribution should be estimated for the current epoch using the particles. In Equation (

7), the mean value of the target Gaussian distribution (

) is estimated with the help of the current particles. Equation (

8) shows the logarithm of the Gaussian distribution, which corresponds to the discrete distribution

shown in Equation (

6). The covariance in this distribution is denoted by

, and the dimensionality is denoted as

d (this value is four, given the state vector). Finally, the cross-entropy of the PF with the Gaussian target distribution is shown in Equation (

9). The proposed PF and cross-entropy check are shown in

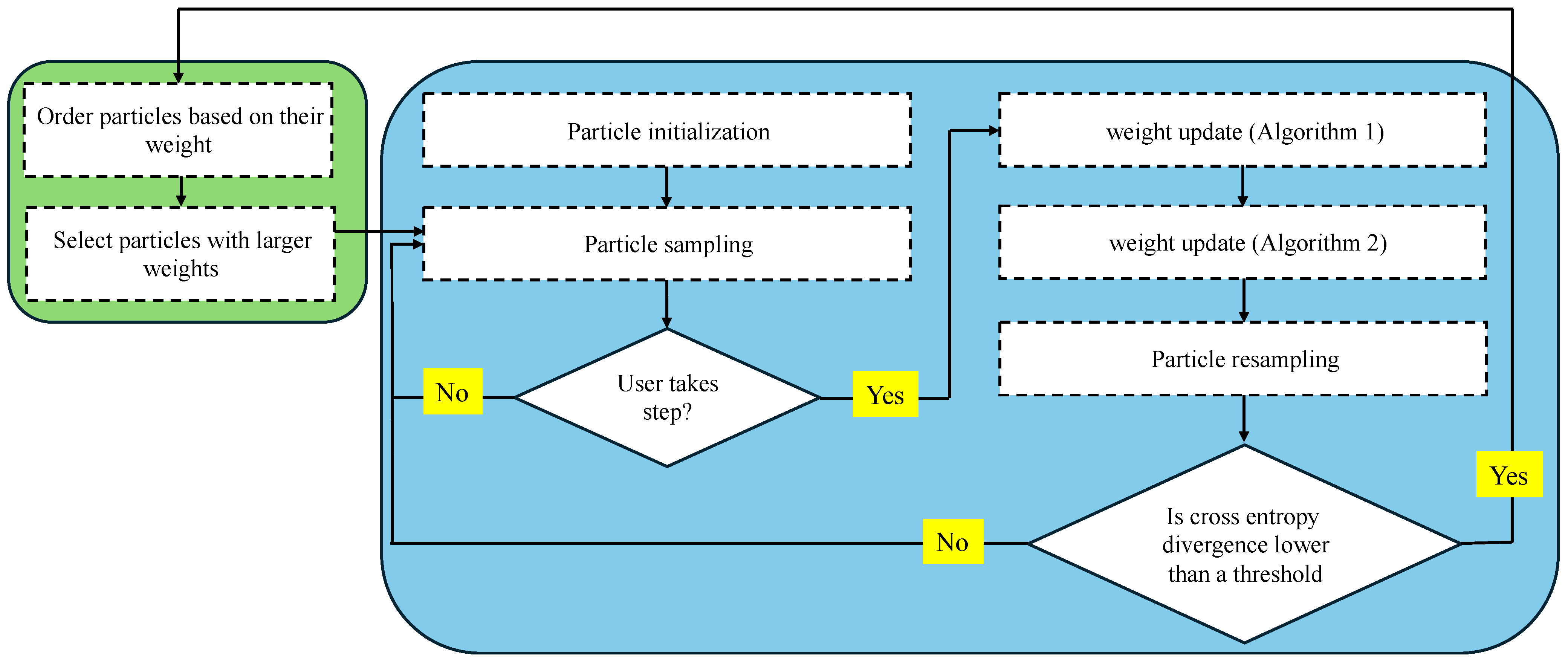

Figure 3.

The cross-entropy test explained above requires defining the target distribution (here, a Gaussian). To determine the covariance in this distribution, information from the 2D floor plan should be utilized. For the tests performed in the next section, we used the width of the hallway as the uncertainty in the target distribution along the x and y directions. The width of the hallway represents the shortest wall-to-wall distance. Particles that fall inside the hallway and move along its boundaries are valid and cannot be removed through map updates. Therefore, we expect the precision of the proposed method to match this width and the covariance matrix () of the target distribution is set based on the hallway width. If the covariance matrix is set to much smaller values, particle reduction will not occur, since the cross-entropy distance will not fall below the required threshold. On the other hand, if the covariance is set to a much larger value, particle reduction will happen too early, increasing the risk of particle impoverishment. Based on the discussion above, the covariance matrix of the target distribution can be set according to the specific structure of the environment.

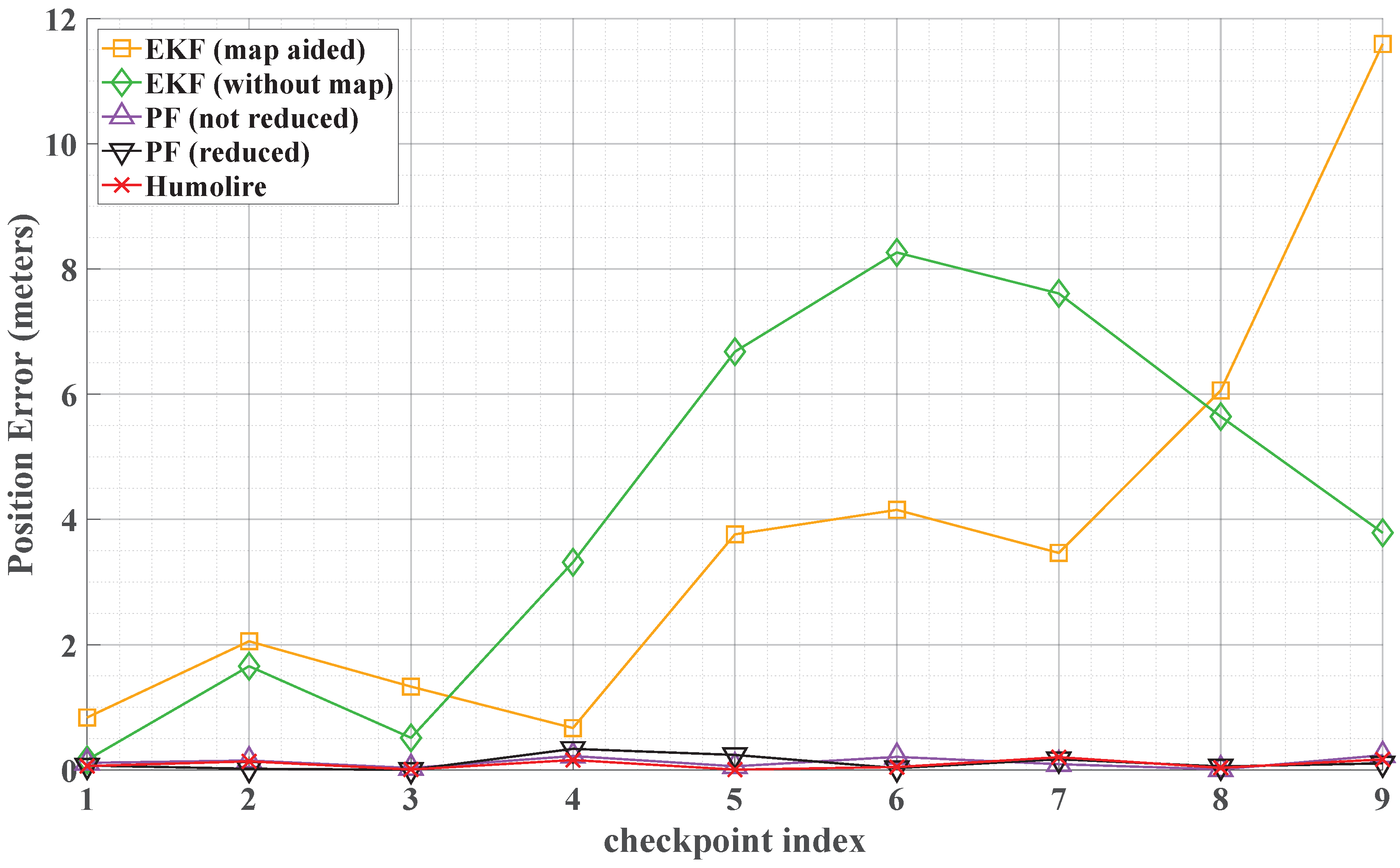

3. Results

In this section, the accuracy of the developed method is evaluated using waypoints and other filtering-based solutions. To obtain a reference estimate of the user’s location along the trajectory, the user stops at specific points on the map, referred to as waypoints. The positions of these waypoints are extracted from the CAD model of the building. These stops can be easily detected in the dataset using the gyroscope measurements. At each waypoint, the user also aligns with a nearby wall in the hallway, and the corresponding hallway direction is used to estimate the heading. The proposed reduced PF is compared against classical PF (without particle reduction), extended Kalman filter (without map aid), extended Kalman filter (map-aided), and Humolire [

26]. The map-aided Kalman filter incorporates the orientation of nearby walls in the update step to correct the heading.

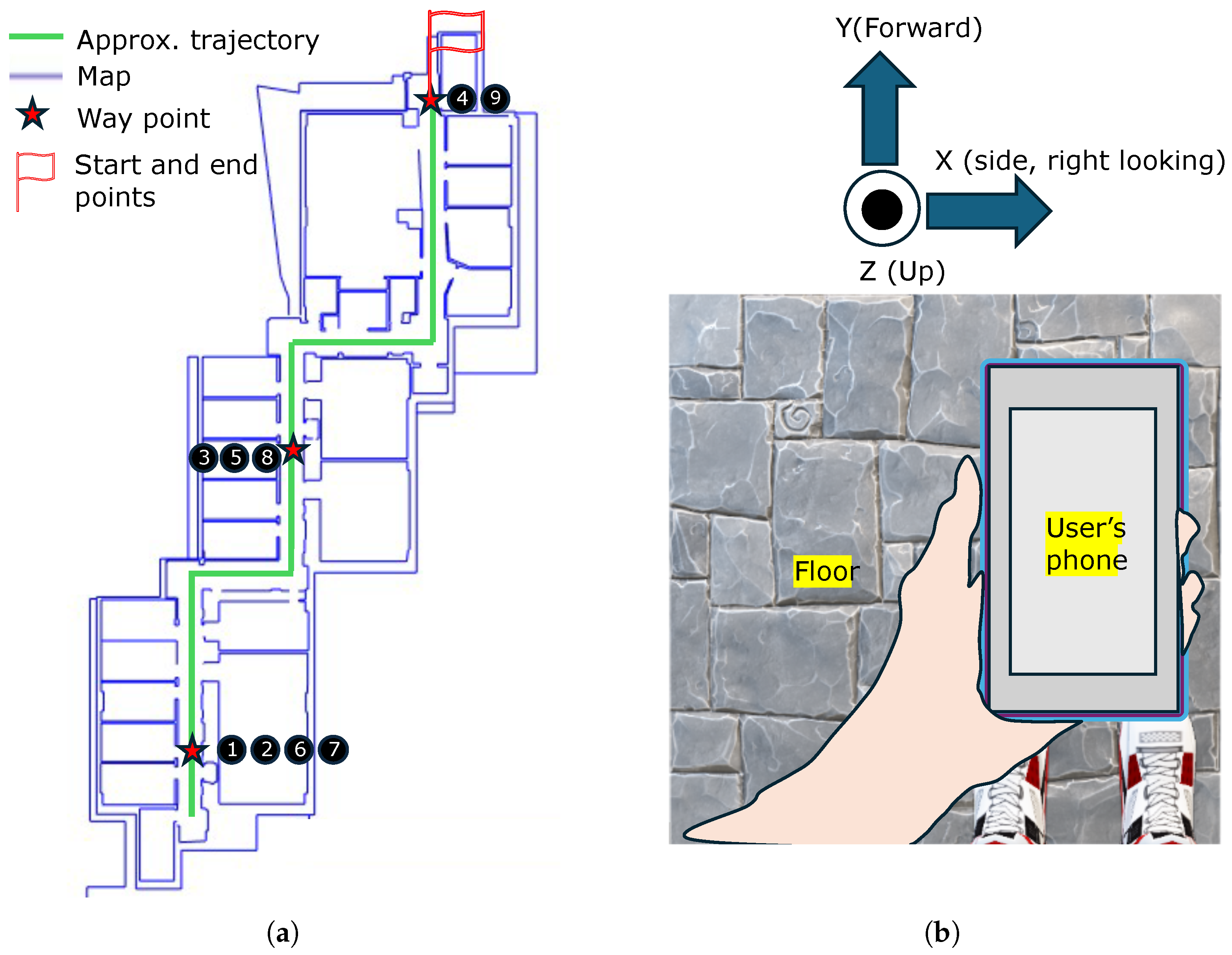

Figure 4a shows the waypoints used for accuracy evaluation. In this figure, the start and end points are marked with a red flag. The CAD map of the environment is shown in blue lines, and the waypoints are represented as stars (nine waypoints in total). The user completes two loops before stopping at the same location as the start point. Data are collected using a Samsung A16 phone, which the user holds in hand during navigation, as shown in

Figure 4b.

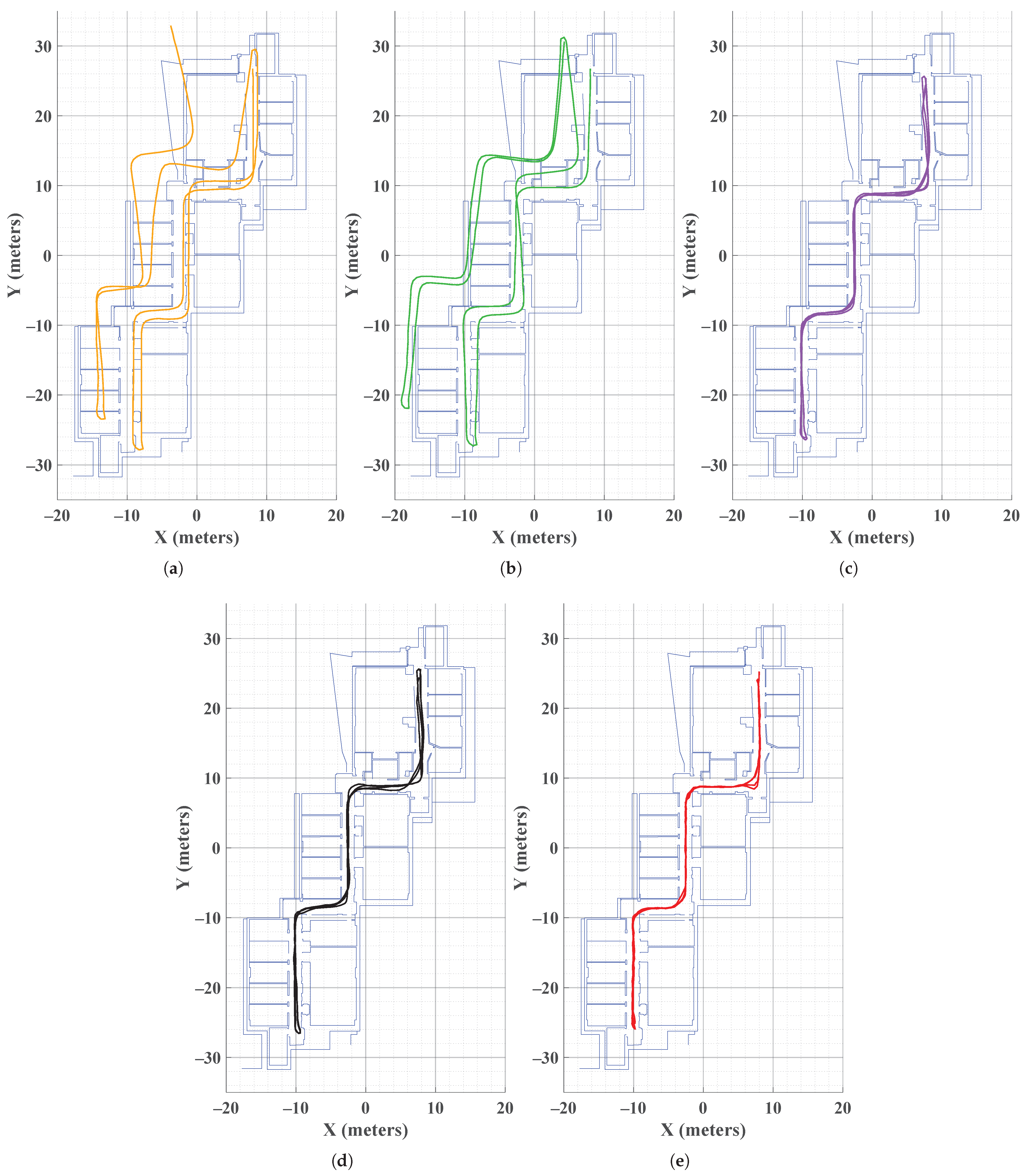

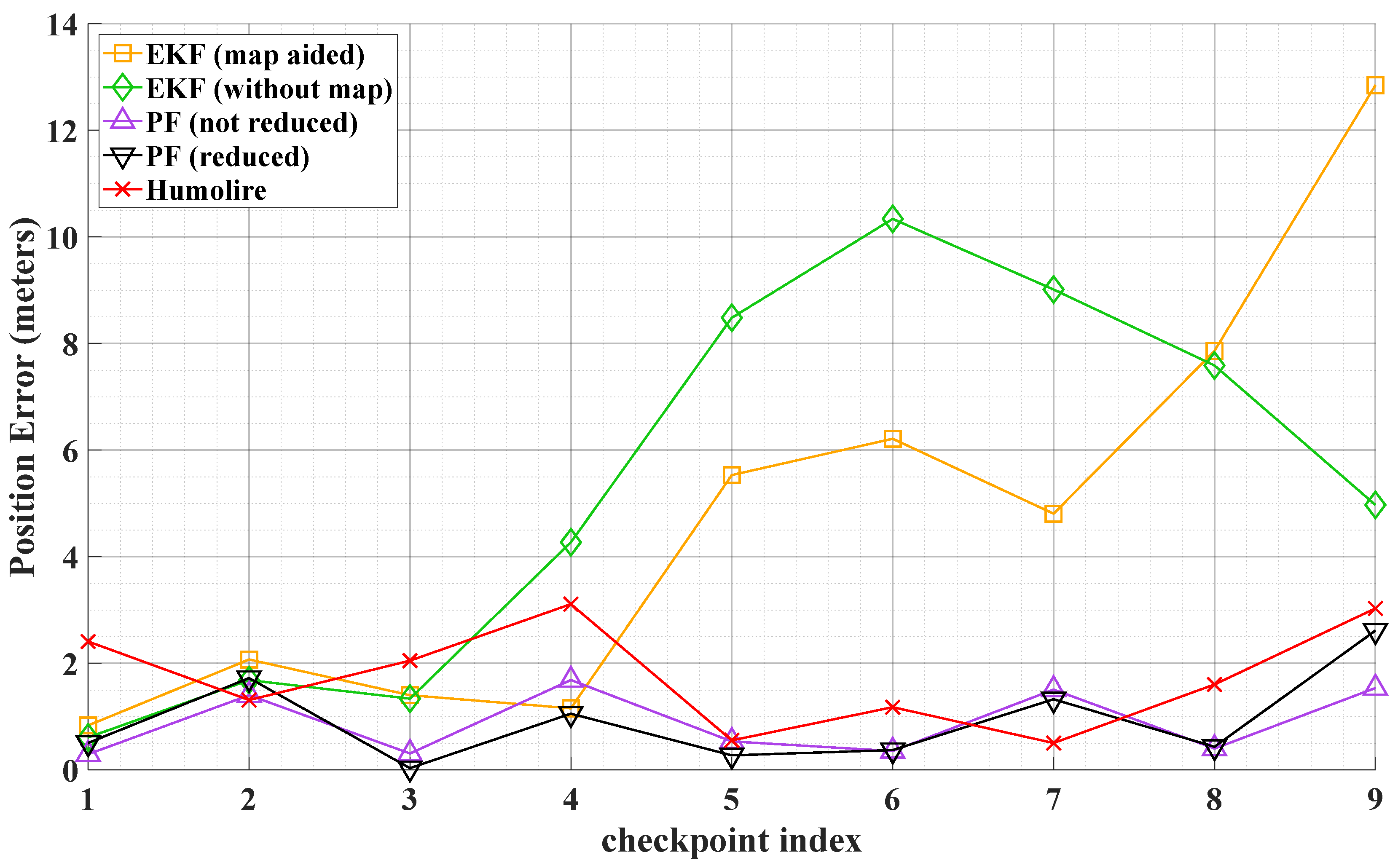

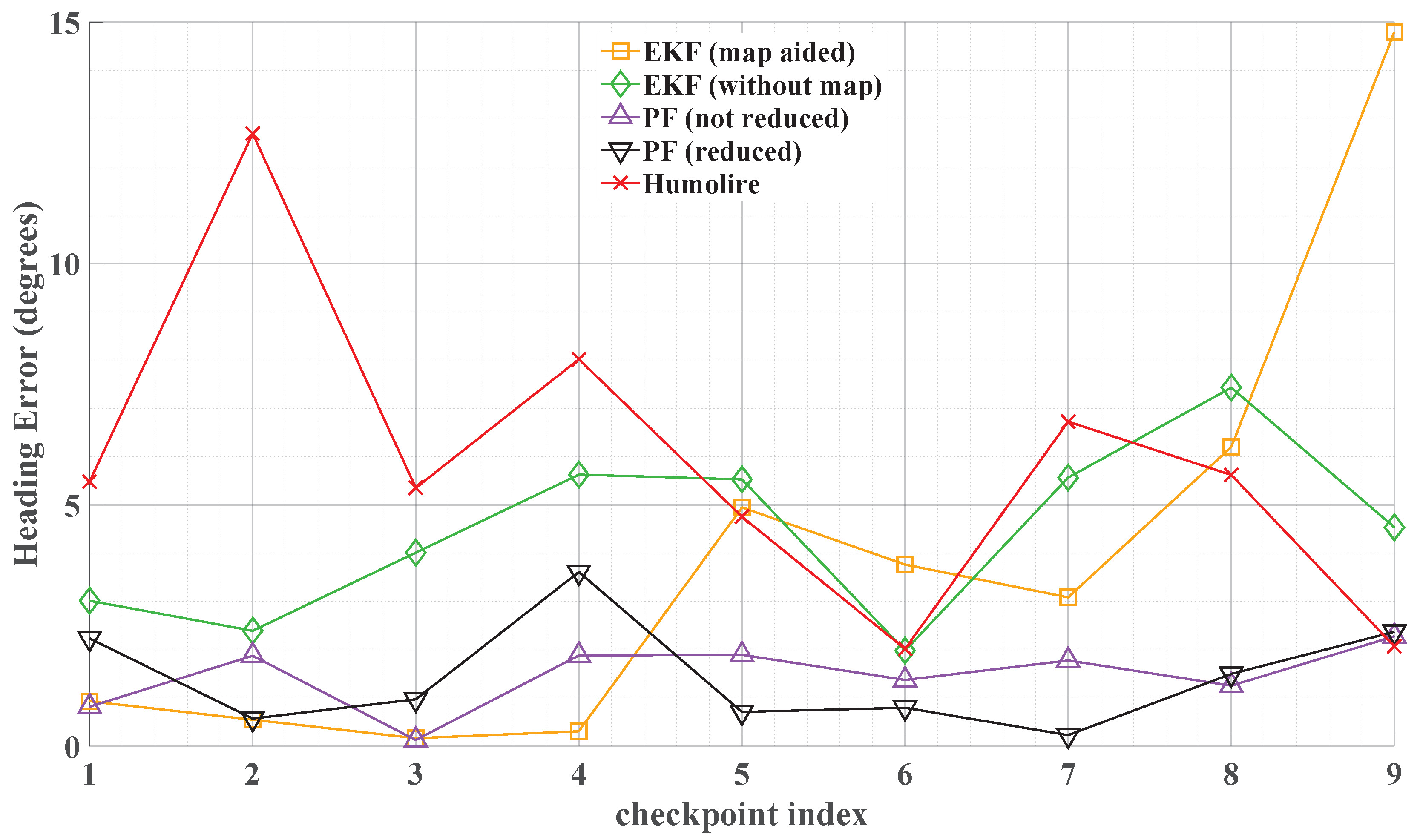

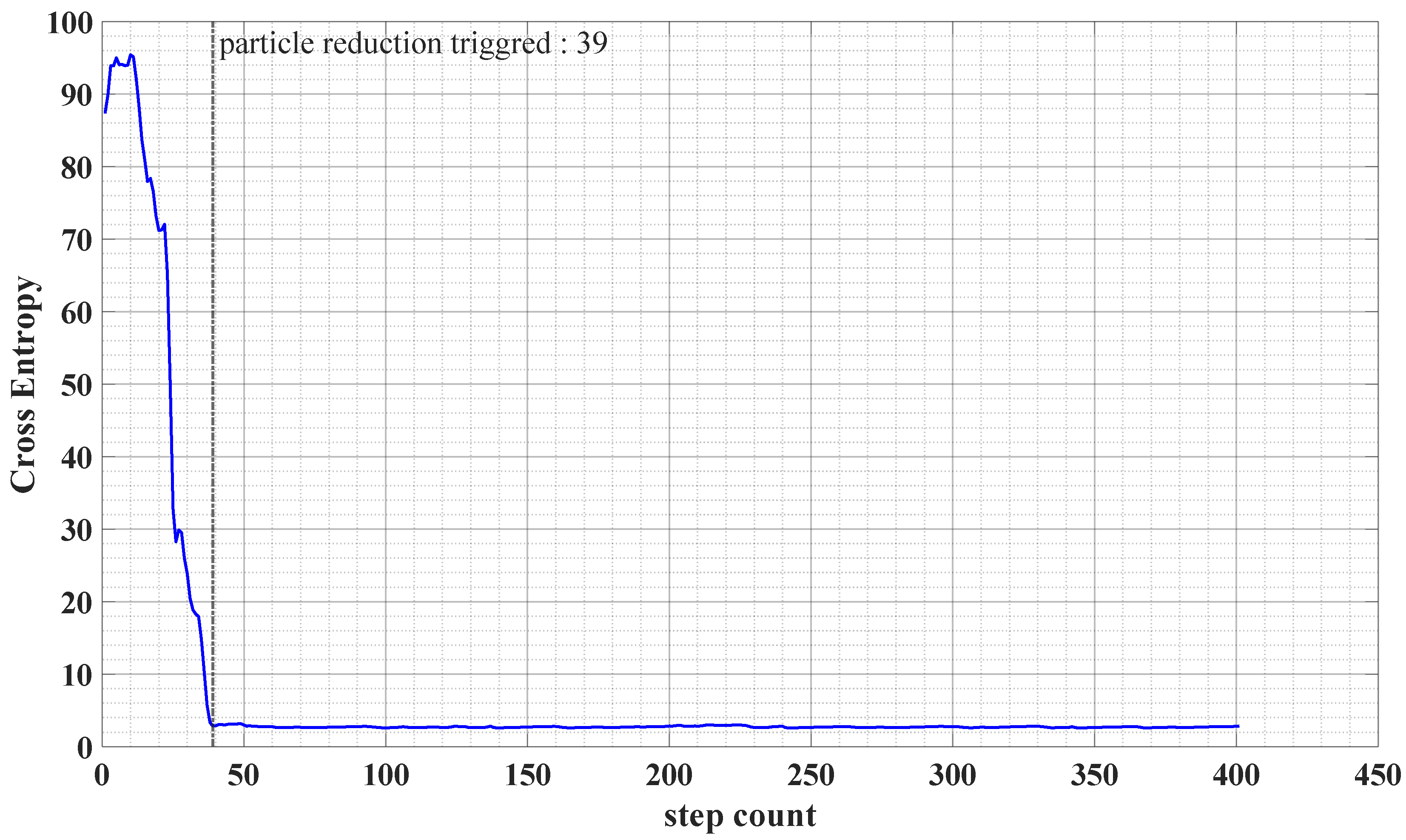

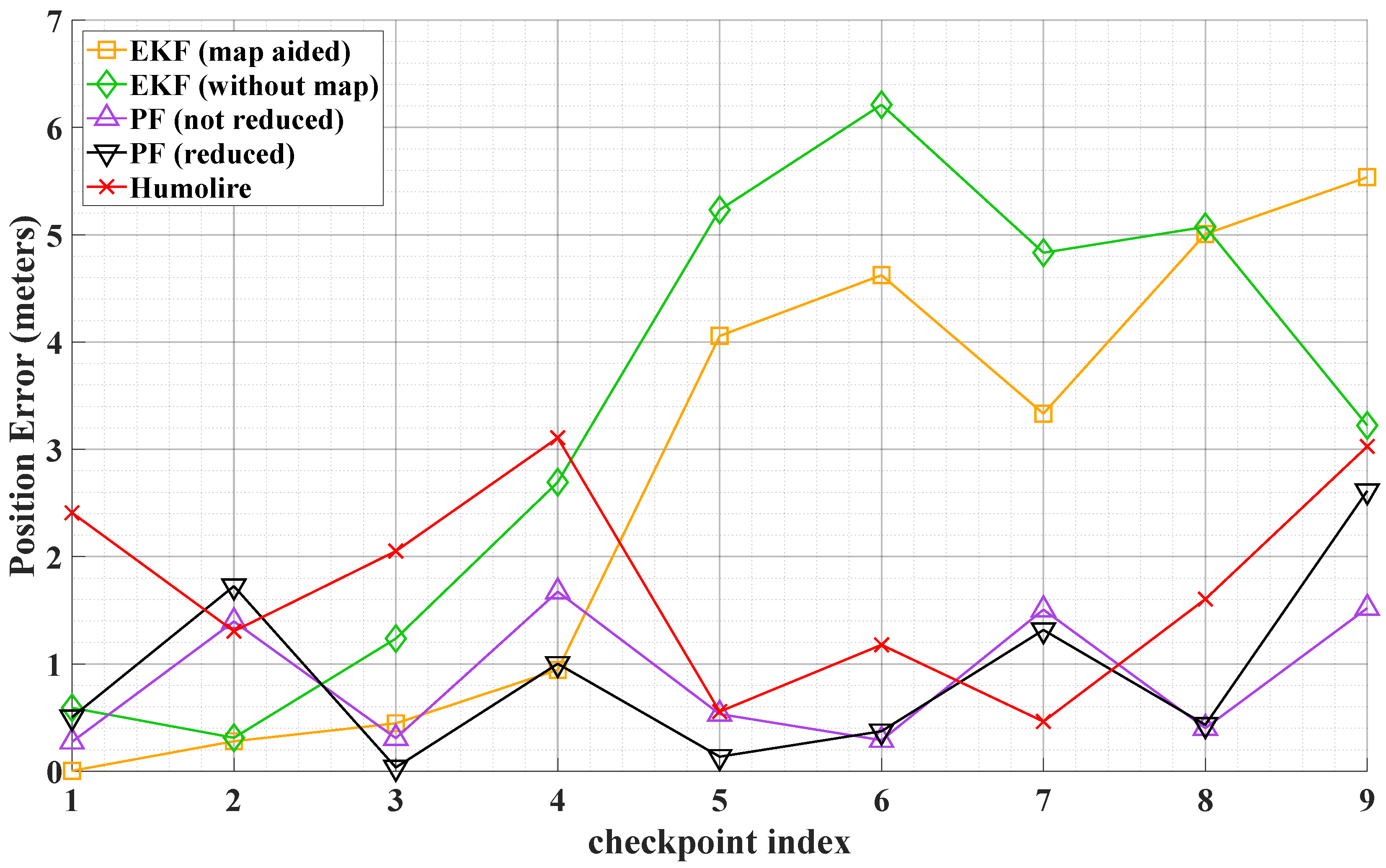

Figure 5 compares the estimated trajectories of the five methods. Based on these trajectories, the PF, Humolire, and the proposed reduced PF demonstrate better performance compared to the Kalman filtering–based approaches. The map-aided extended Kalman filter achieves higher position error initially; however, its accuracy degrades over time due to error accumulation throughout the user’s motion. These results indicate that extended Kalman filtering is not suitable for indoor navigation because of the highly non-Gaussian nature of trajectory estimation errors. A quantitative analysis of the results, including the errors at each waypoint, is presented in

Figure 6 (position error) and

Figure 7 (heading error). These results show that the proposed reduced PF outperforms Humolire, particularly in heading estimation, where Humolire exhibits significantly larger errors at the beginning of the navigation. The quantitative results of the position error (in meters) are summarized in

Table 1, which further confirm that the proposed reduced PF outperforms both the Kalman filter and Humolire. Moreover, reducing the number of particles did not result in a significant loss of accuracy.

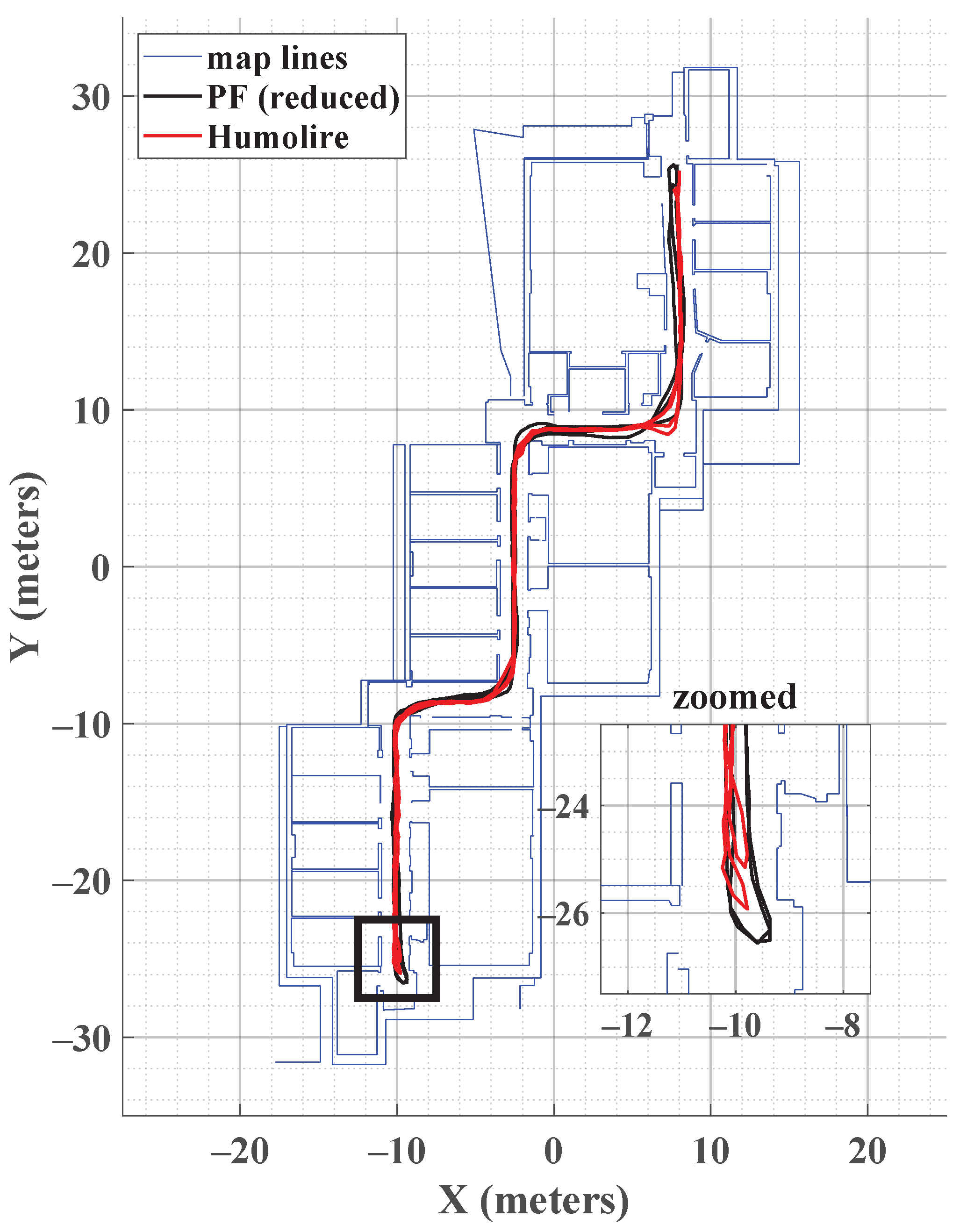

The reduced PF and Humolire trajectories are compared in more detail in

Figure 8. During the two loops, the user follows a similar trajectory when turning at the corner (denoted as “zoomed”). The figure shows that the reduced PF estimates the trajectory accurately in both loops, with the results closely matching. In contrast, Humolire exhibits larger discrepancies and therefore lower accuracy.

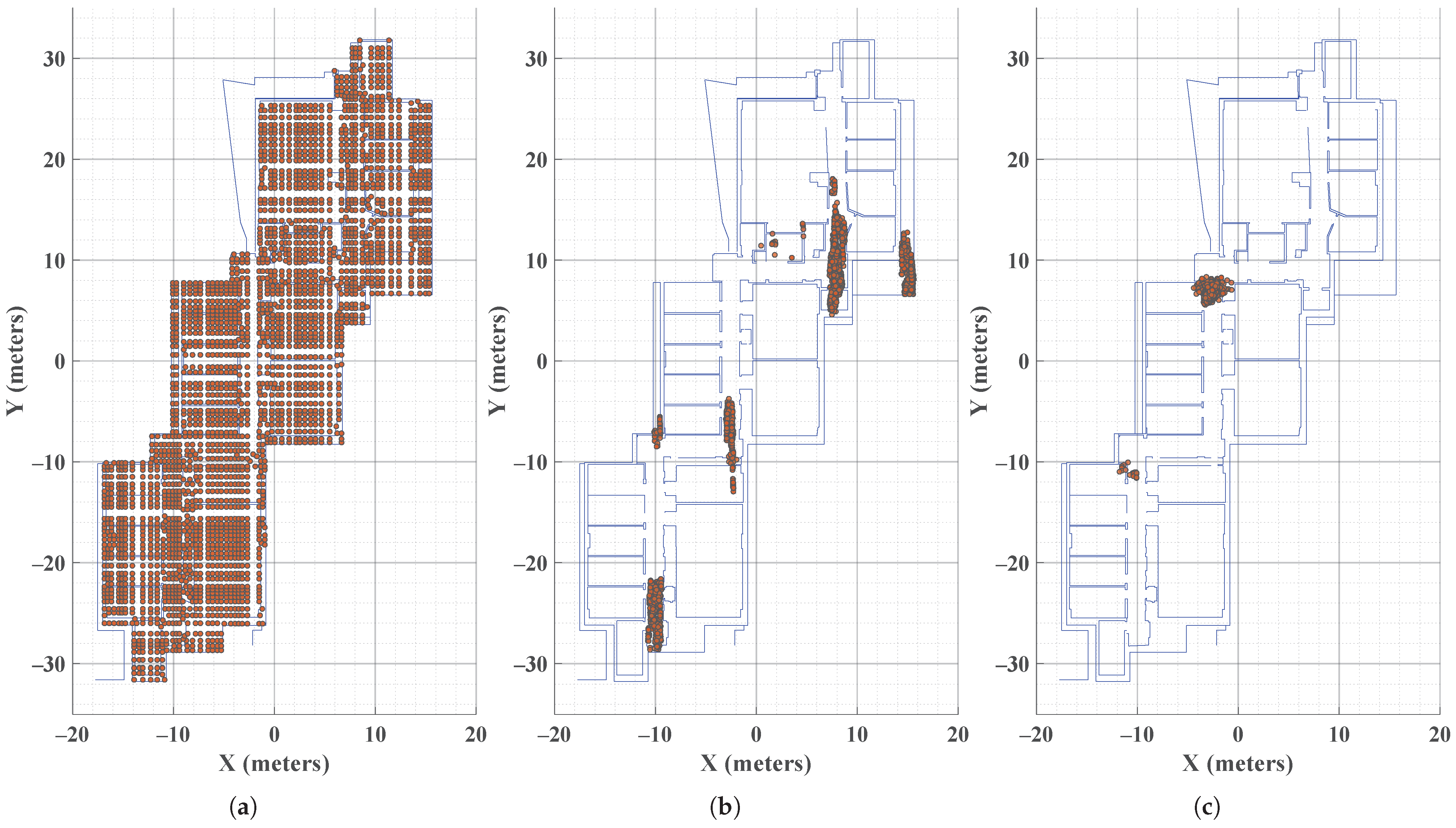

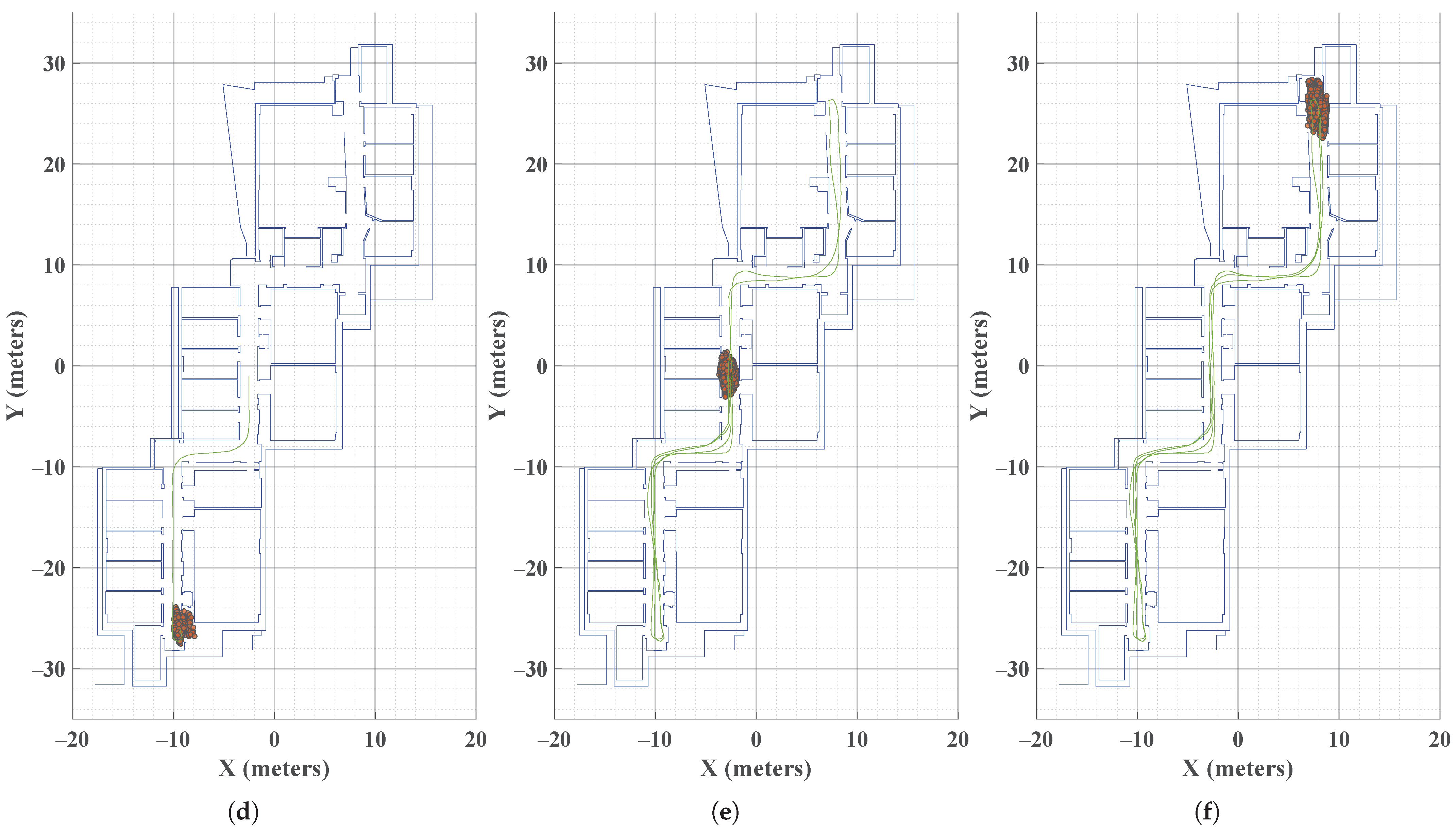

To investigate the effectiveness of cross-entropy in triggering the particle reduction phase, the particle distribution during the user’s motion and the corresponding cross-entropy values are shown in

Figure 9 and

Figure 10. It can be observed that the cross-entropy decreases as the uncertainty in the particle locations approaches a uni-modal Gaussian distribution. The particle reduction step is marked in

Figure 10, corresponding to

Figure 9c.

The position errors in the x and y axes are often different, depending on the geometry of the solution. Geometry is an important concept in areas such as outdoor navigation using GNSS and indoor navigation using beacons. It refers to the relative positions of the sensors with respect to landmarks (such as satellites or, in this case, map lines) and can either improve or reduce accuracy in different directions. For example, in GNSS-based positioning, the vertical direction typically has weaker geometry, leading to lower accuracy. Geometry plays a key role when using other sensors for navigation, such as LiDAR, where poor accuracy is often observed along the direction of hallways in indoor environments.

For the problem of map-aided indoor PDR, geometry also plays a crucial role. While user motion is generally not restricted along hallways (the

y direction), as shown in

Figure 9, motion in the

x direction is constrained. Therefore, it is expected that the map provides a more significant update in

x due to better geometry.

Figure 9 shows that once the particles converge (subfigures d, e, and f), they are more scattered in

y compared to

x. This discrepancy in geometry is further examined in

Figure 11 and

Figure 12. While all PF solutions yield highly accurate results in the

x direction, the accuracy in the

y direction is comparatively poor.

An important assessment criterion for smartphone applications is computational cost, as user-based navigation requires real-time solutions. The runtime of the proposed method is shown in

Table 2. To obtain these evaluations, the execution time was recorded for particle prediction, particle updates (Algorithms 1 and 2), and particle resampling in the proposed method. Similarly, the runtimes of Humolire and the Kalman filters were recorded for their prediction and update steps. Each filter processed approximately 15,000 measurement epochs from the accelerometer and gyroscope. The IMU data were sampled at 60 Hz, corresponding to approximately 250 s of user motion. The processing rate of the proposed approach is about 37 Hz, which is suitable for real-time applications. We further measured and compare the time required for the cross-entropy test with particle prediction and update reported above. Overall, the cross-entropy test takes only

of the total time for particle prediction and update. Therefore, this test does not lead to challenges for an online deployment of the algorithm.

Gyroscope leveling using accelerometer readings is an important step in the proposed algorithm (see

Figure 1, particle filter independent module). Leveling corrects the roll and pitch of the device, which is essential for accurately estimating the user’s heading. To investigate the contribution of the leveling step, rotation offsets of

,

,

, and

were applied along the x-axis (see

Figure 4). This is equivalent to tilting the smartphone up or down relative to the gravity vector. The estimated mean positions before and after levelling are provided in

Table 3. The results indicate that, for smaller rotations (e.g.,

), leveling has little impact on the results. However, for larger rotations, position accuracy decreases when leveling is not applied. In the case of a

rotation offset, the scenario without gyroscope leveling fails to produce a solution due to particle impoverishment.

4. Conclusions

This paper presents a novel map-aided PF-PDR framework that tackles a long-standing challenge in PF-based trajectory estimation: computational inefficiency. The proposed method reduces the overall computational cost by using a two-stage PF. In the first phase, particles are initialized within the pre-built map. The number of particles is significantly reduced once convergence toward a Gaussian distribution is detected using the cross-entropy distance. Further improvement in the computational cost is achieved by using only the heading in the motion estimation. The heading is estimated successfully by levelling the gyroscope measurement to a virtual plane parallel to the floor plane. By utilizing gyroscope measurements and incorporating a cross-entropy-based sampling strategy, the proposed method attains faster and more stable convergence while preserving computational efficiency suitable for real-time positioning applications. Experimental evaluations on a collected dataset demonstrate that the approach achieves high accuracy, with an average positioning error of 0.9 m and an average processing rate of 37.0 Hz. Importantly, the framework operates without reliance on additional wireless signals or vision-based sensors, underscoring the feasibility of accurate and reliable indoor localization using only smartphone IMU data. Compared with traditional EKF-PDR, PF-PDR approaches and state of the art (Humolire), this research work provides a more accurate solution with improved computational efficiency.

This research work still has several limitations. First, the proposed solution relies on the availability of a pre-built floor map; therefore, trajectory estimation cannot be improved in large open areas which lack structural constraints. Second, the proposed PDR framework is limited to single-floor scenarios, as it only considers 2D motion without estimating vertical displacement along the z-axis. Future research will address the following aspects. First, the current solution will be extended to a positioning framework that dynamically adapts to the reliability and availability of maps. Moreover, we plan to explore the use of 3D and semantically enriched map representations to support multi-floor navigation.