A Comprehensive Modelling Framework for Identifying Green Infrastructure Layout in Urban Flood Management of the Yellow River Basin

Abstract

1. Introduction

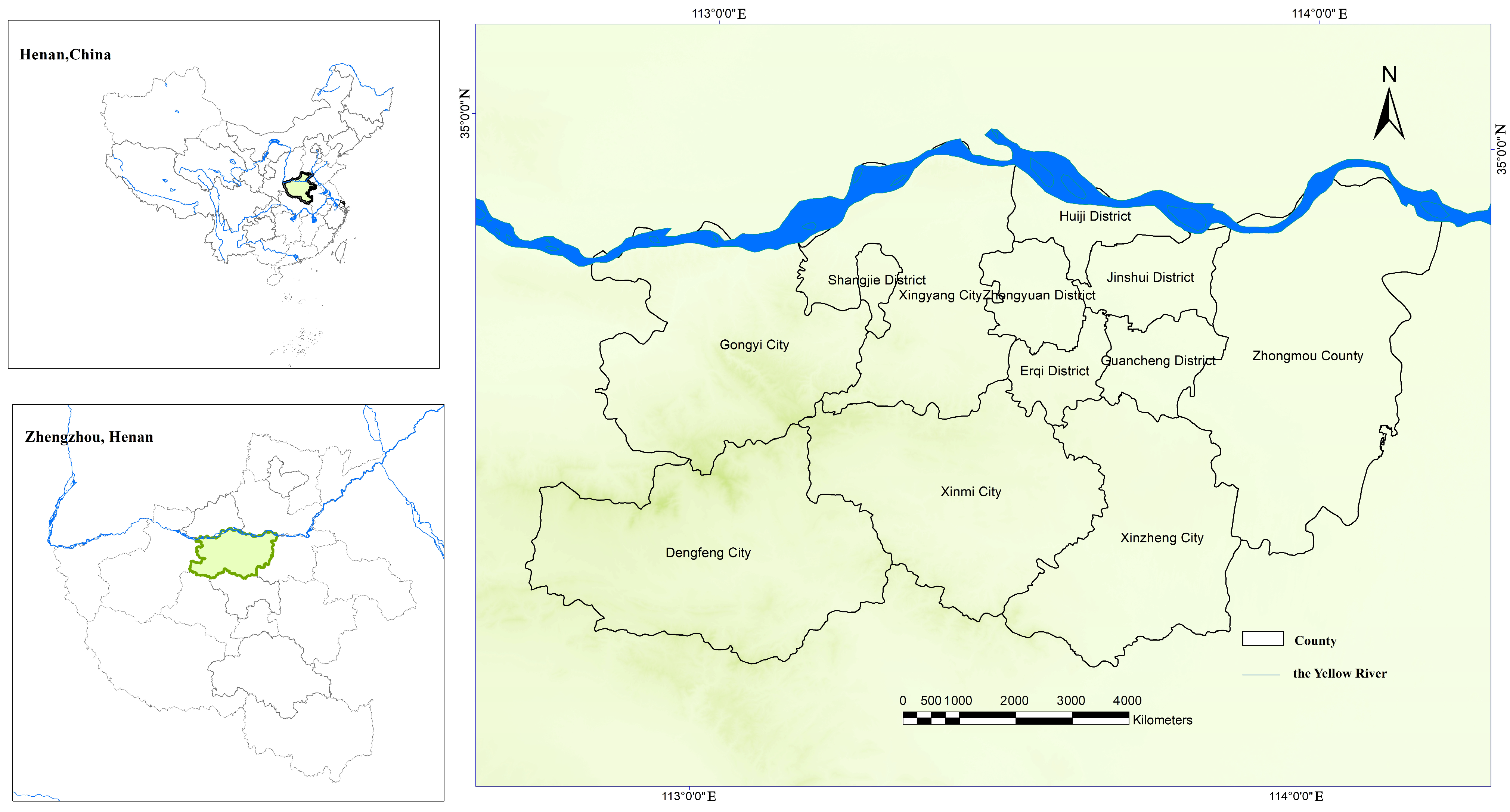

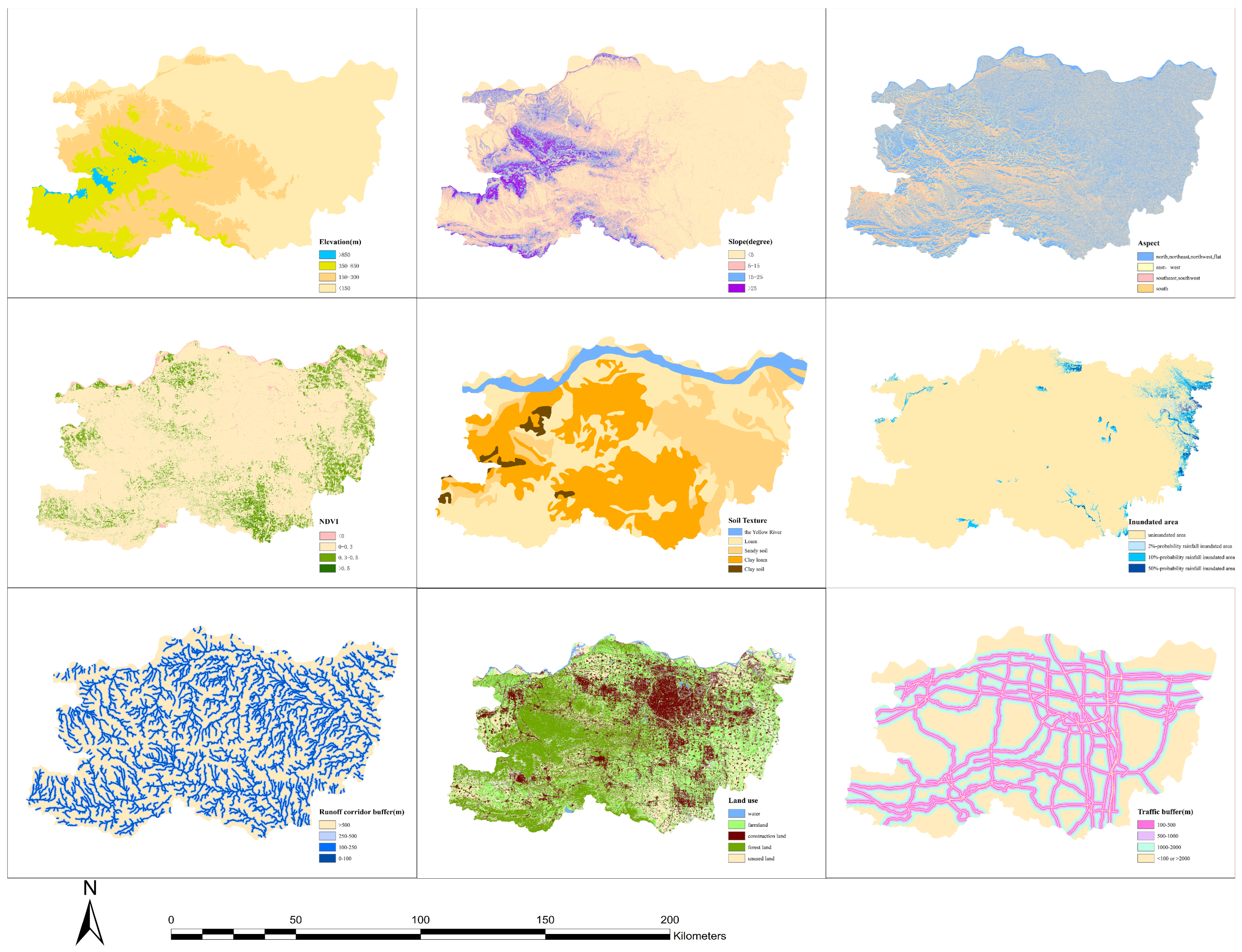

2. Study Area and Data

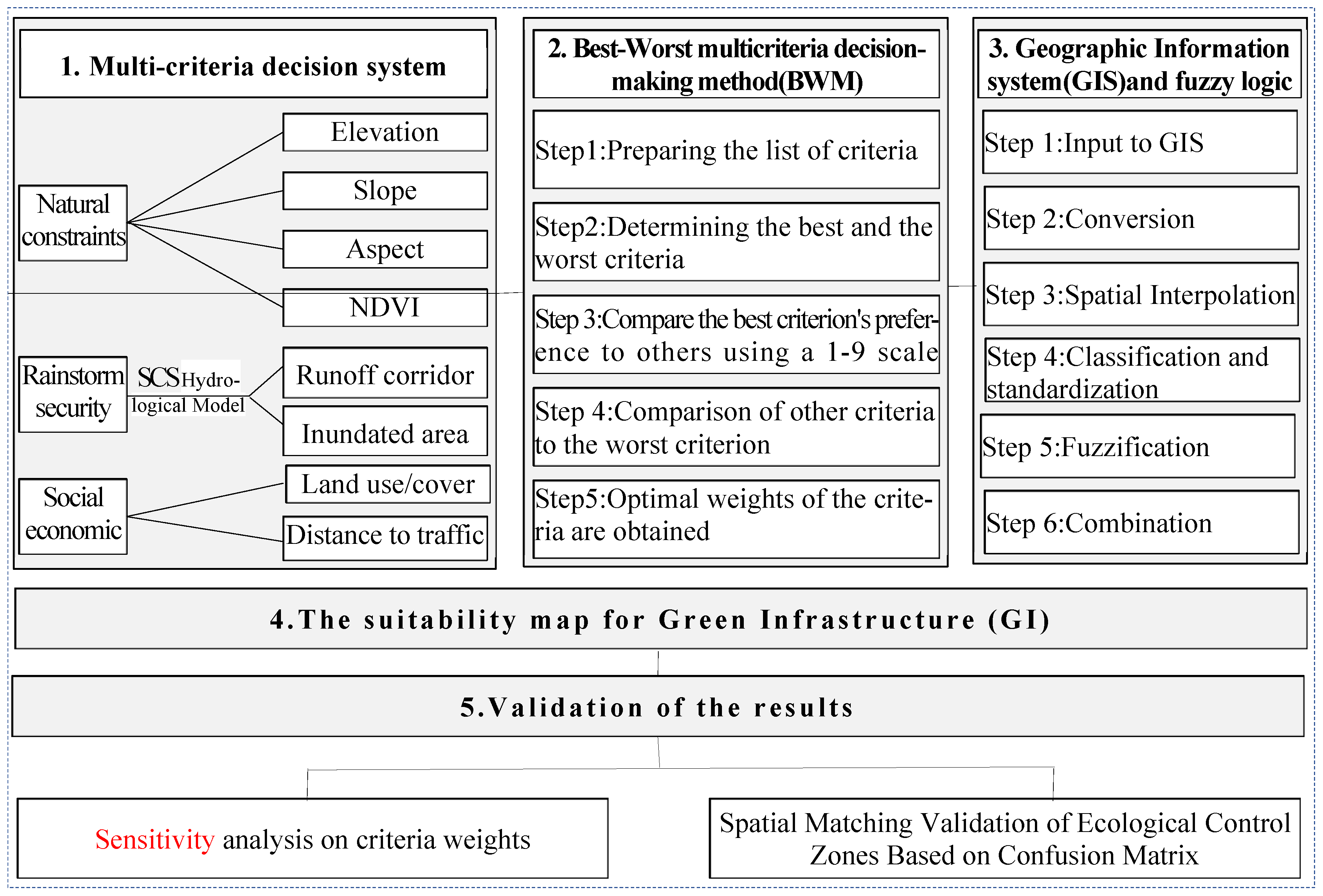

3. Methods

3.1. SCS Model and Calibration

3.1.1. Rainfall–Runoff Relationship

3.1.2. Local Calibration of CN Values

3.2. Rainfall-Flood Simulation

3.2.1. Multi-Duration Design Rainfall Scenarios

3.2.2. Extract Runoff Corridors and Inundated Areas

3.3. Data Selection and Evaluation Criteria

| Criteria | Sub-Criteria | Highly Suitable | Moderately Suitable | Less Suitable | Not Suitable | Range Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flood security | Runoff corridor buffer zone (m) | 0–100 | 100–250 | 250–500 | >500 | Literature and GIS analysis |

| Inundated area | Inundated area under 50% probability rainfall | Inundated area under 10% probability rainfall | Inundated area under 2% probability rainfall | Uninundated area | Literature and GIS analysis | |

| Natural conditions | Elevation (m) | <150 | 150–350 | 350–850 | >850 | Literature and GIS analysis |

| Slope (degree) | <5 | 5–15 | 15–25 | >25 | Literature and GIS analysis | |

| Aspect | North/ northeast/ northwest | East/west | Southeast/ southwest | South | Literature and GIS analysis | |

| NDVI | >0.5 | 0.3–0.5 | 0–0.3 | <0 | Literature and GIS analysis | |

| Soil texture | Sandy soil | Loam | Clay loam | Clay soil | Literature | |

| Social economy | Land use | forest land/ water area | unused land | farmland | construction land | Literature and GIS analysis |

| Distance to provincial road/ urban arterial road (m) | <30 | 30–100 | 100–200 | >200 | Literature and GIS analysis |

3.4. Weighting Criteria

| The Intensity of Importance on an Absolute Scale | Definition | Explanation |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Equal importance | Two activities contribute equally to the objective |

| 3 | Moderate importance of one over another | Experience and judgement strongly favour one option over another |

| 5 | Essential or strong importance | Experience and judgement strongly favour one activity over another |

| 7 | Very high importance | Activity is strongly favoured, and its dominance demonstrated |

| 9 | Extreme importance | The evidence favouring one activity over another is of the highest possible order of affirmation |

3.5. Fuzzy Logic

4. Results

4.1. Weights of Evaluation Criteria

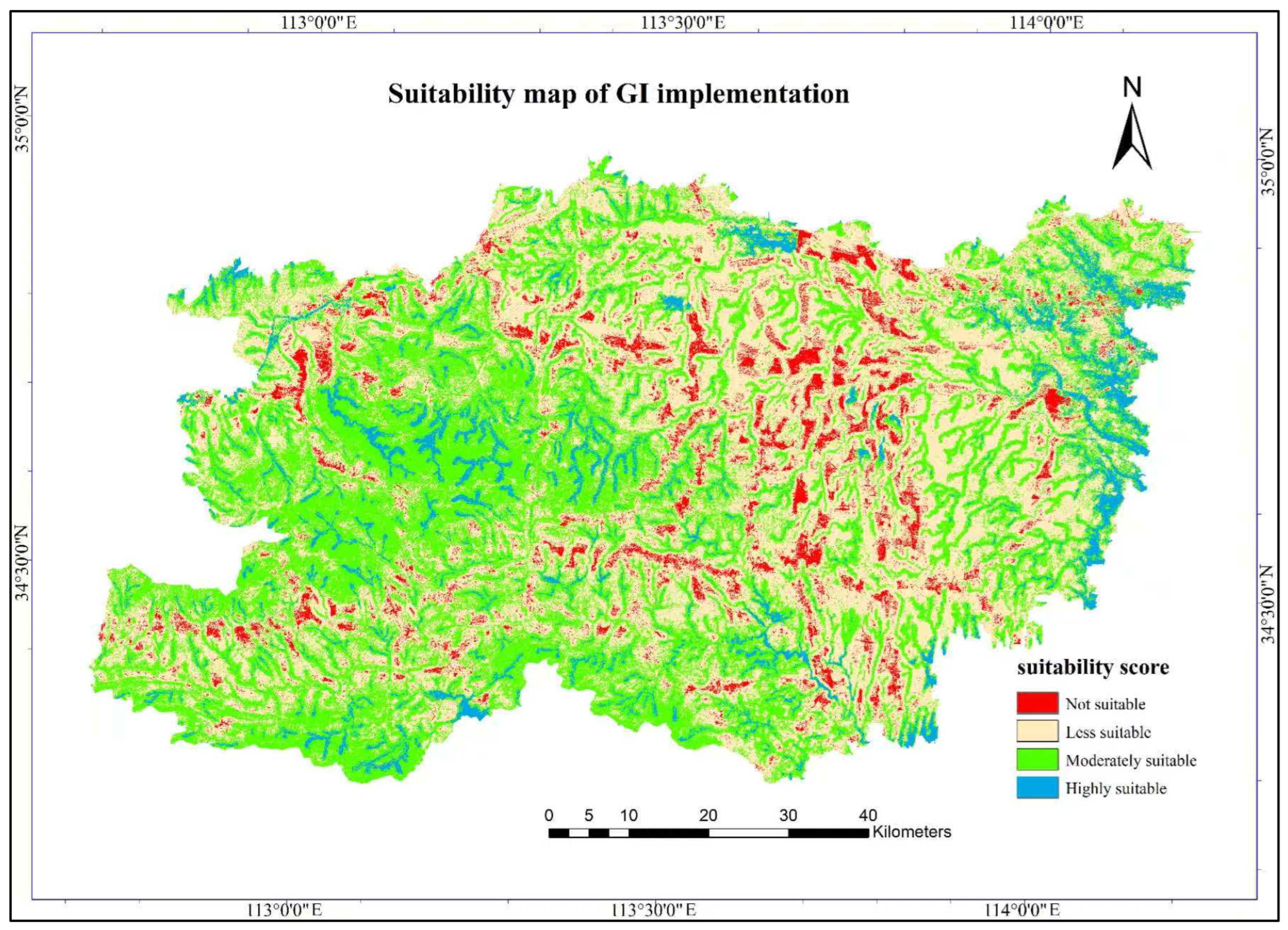

4.2. Suitability Analysis for GI

4.3. Sensitivity Analysis

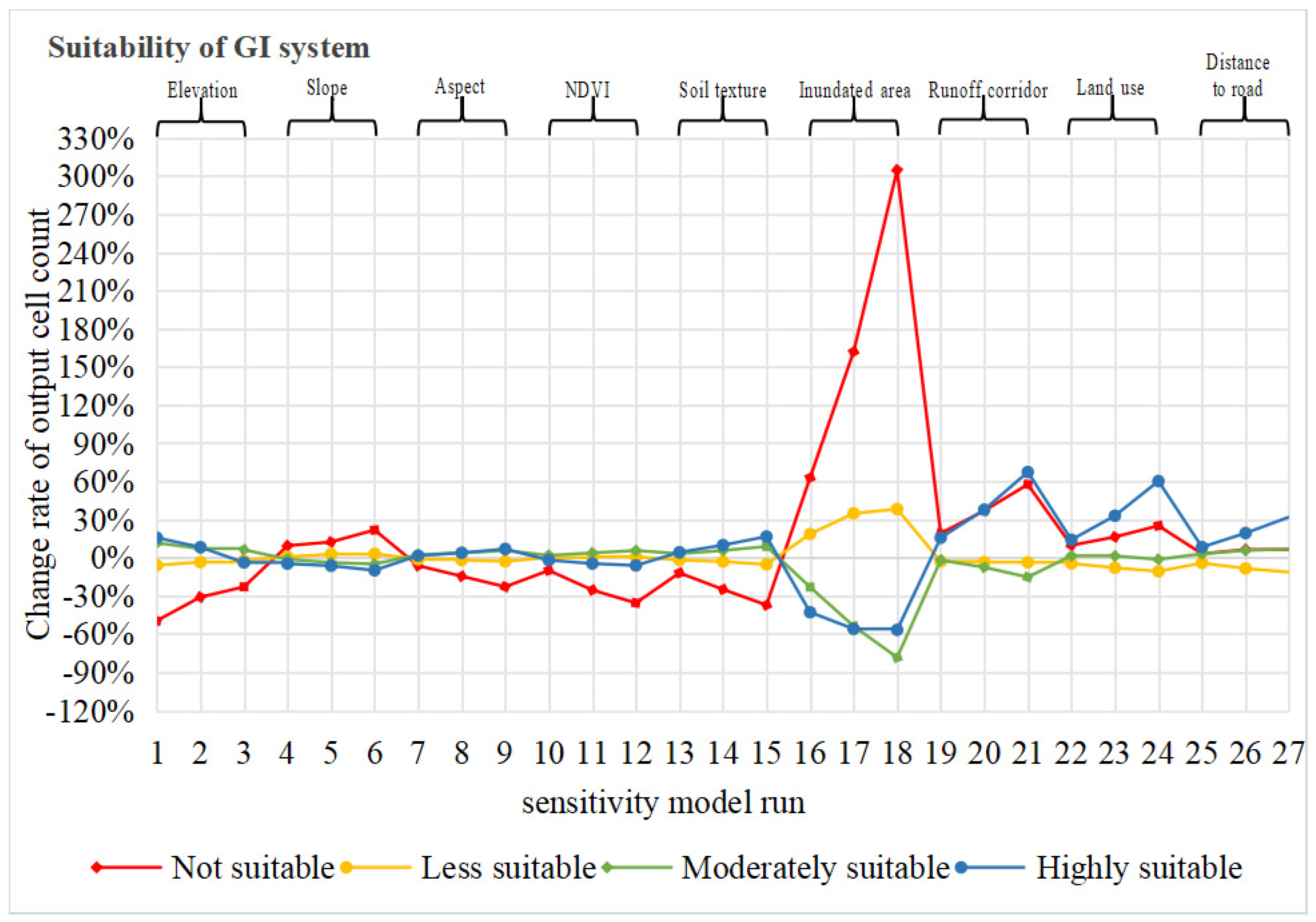

4.3.1. Single-Factor Perturbation Sensitivity Analysis

4.3.2. Multi-Factor Perturbation Sensitivity Analysis

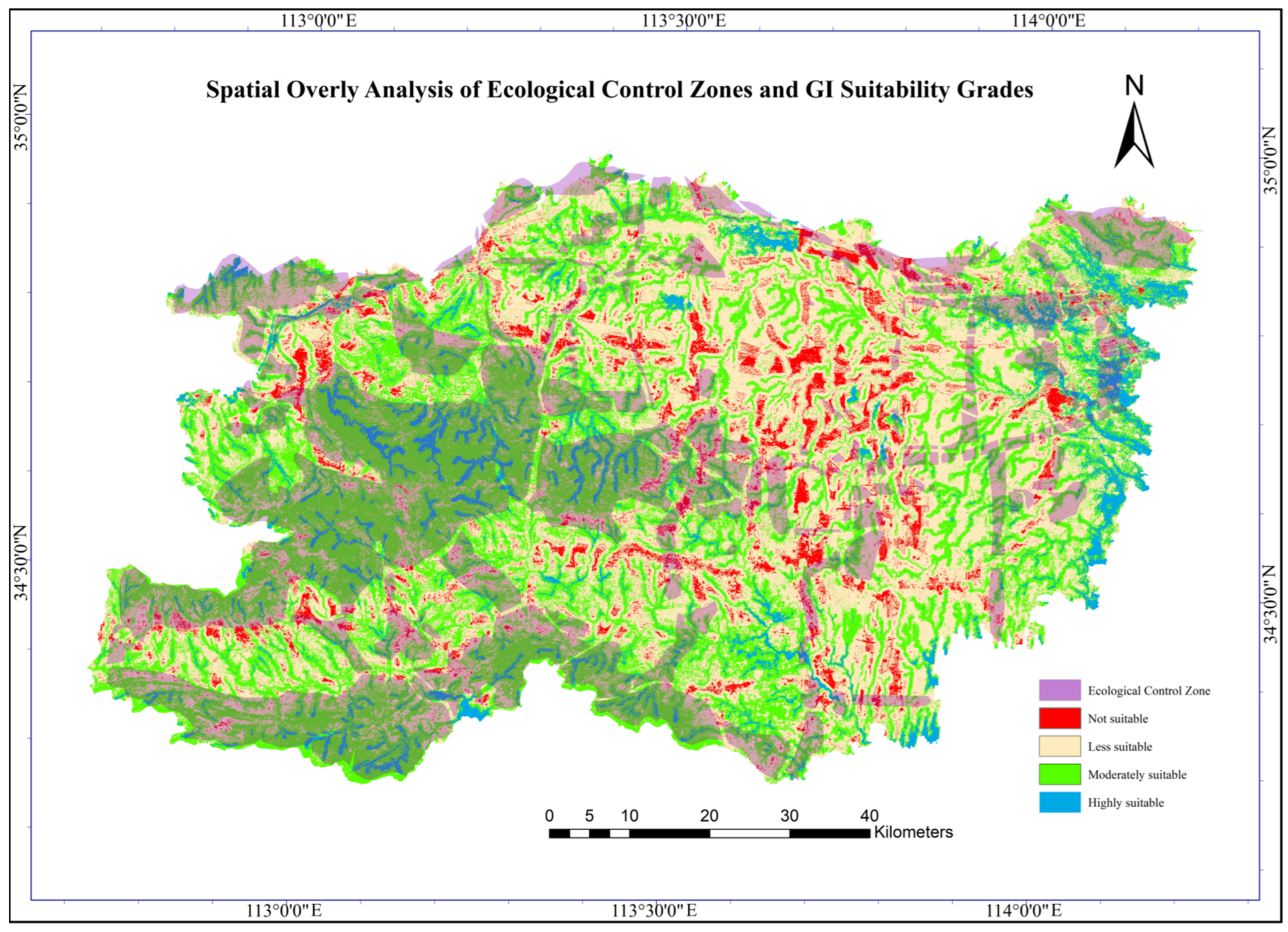

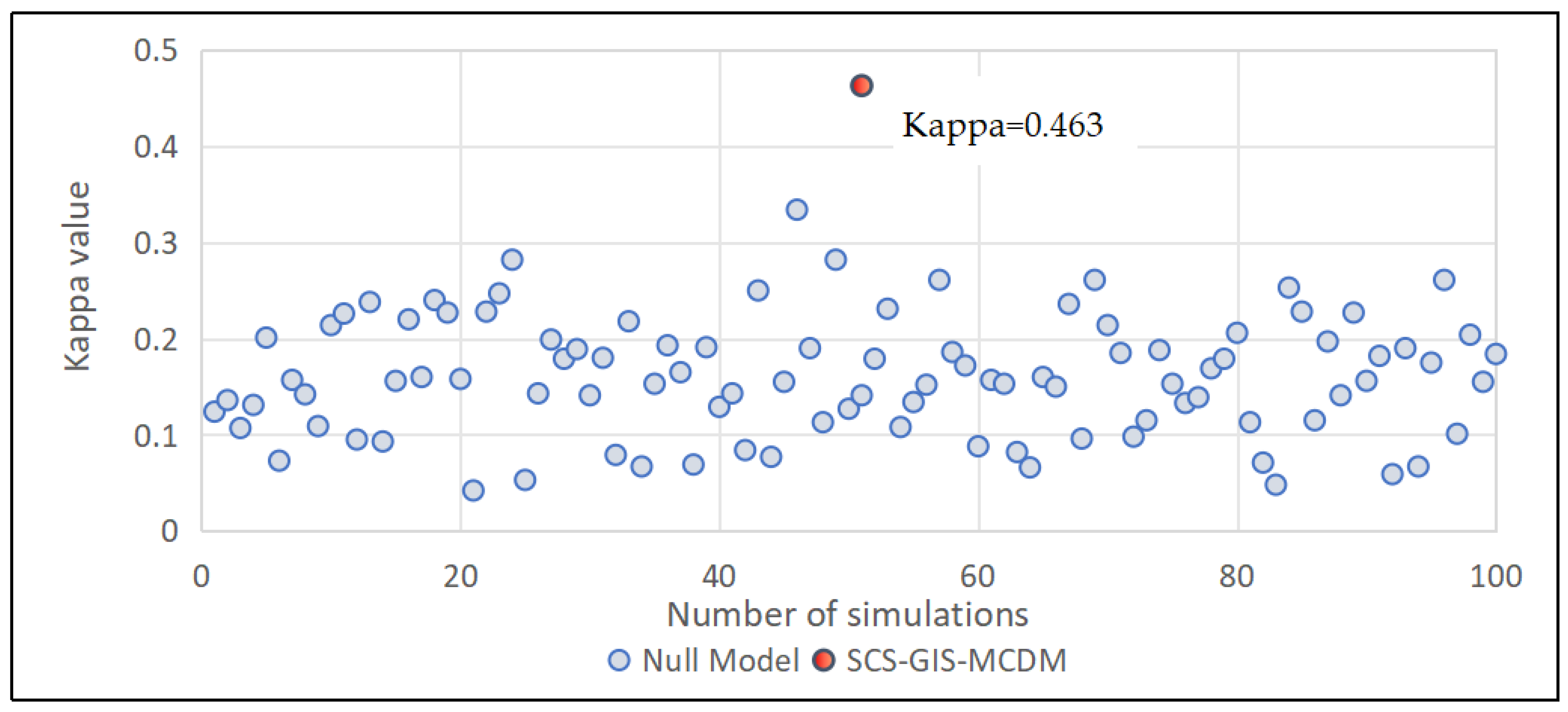

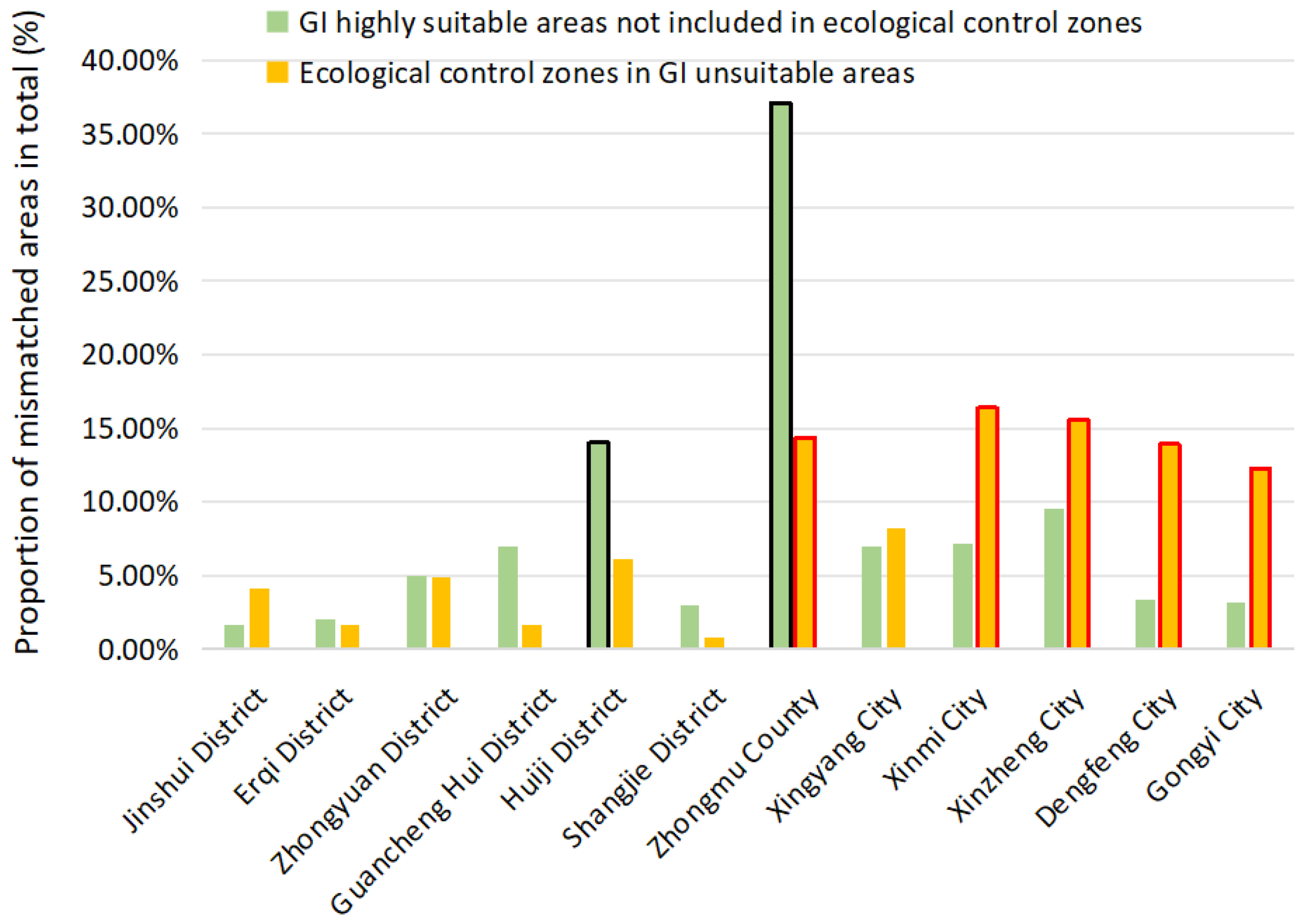

4.4. Spatial Matching Verification

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions and Policy Implications

- (1)

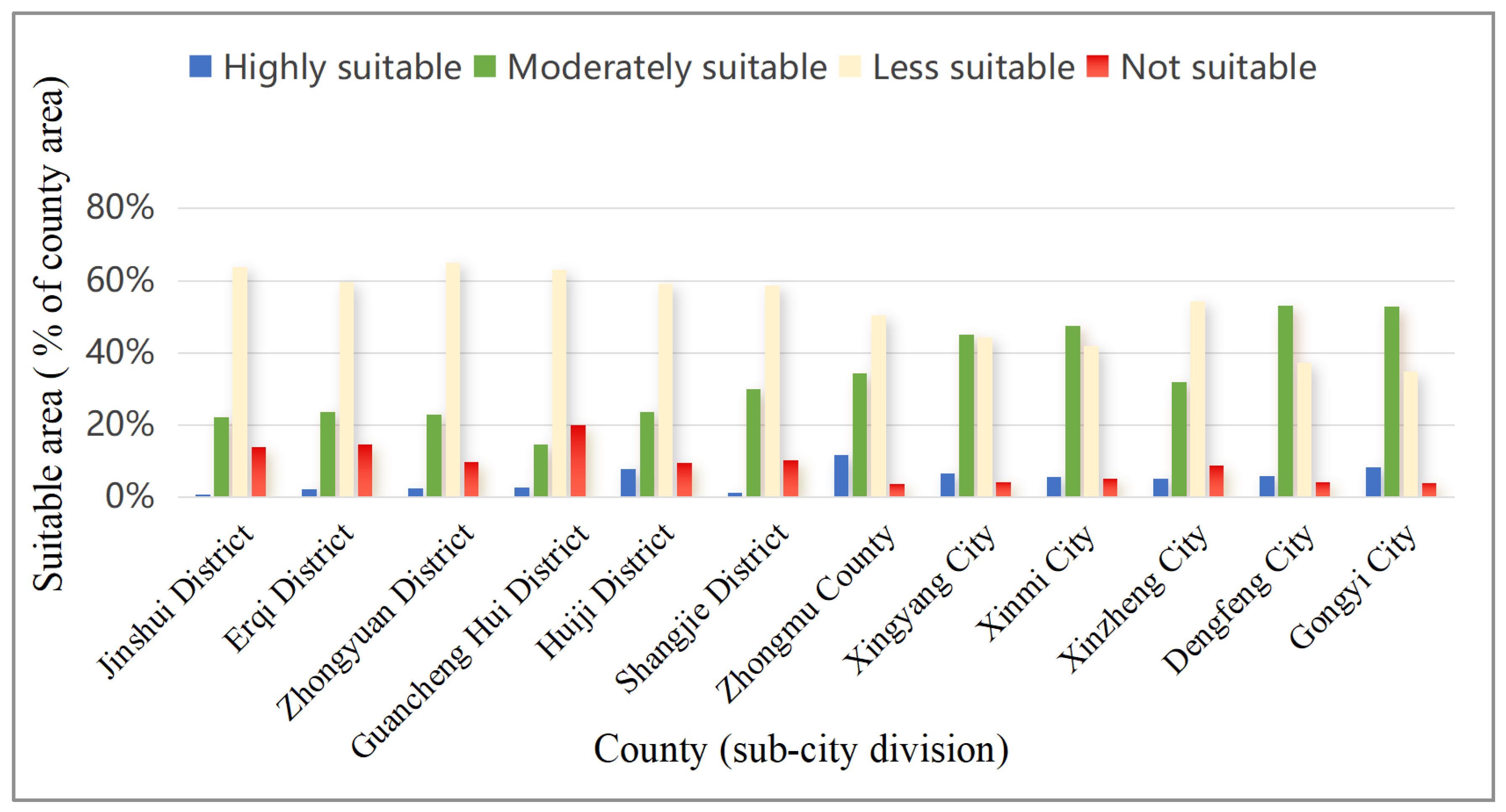

- 6.8% of the land in Zhengzhou is highly suitable for developing GI, while 6% of the land is not suitable. These proportions are not fully comparable to existing studies, mainly due to differing scales and indicator frameworks.

- (2)

- Sensitivity analysis shows that elements of hydrological process simulation are key influencing factors, while elements such as elevation and slope aspect have weak sensitivity.

- (3)

- Confusion matrix comparison between ecological control zones (from green space system planning) and GI suitability zones indicates moderate spatial compatibility, but deviations persist due to static data limitations, insufficient resolution, and modelling assumptions.

- (1)

- Guide spatial planning based on GI suitability zoning and formulate ecological management and control systems. Designate Huiji District and Zhongmu County as “Priority Control Units for Blue–Green Spaces”, incorporate them into the “Yellow River Basin Ecological Protection Plan”, clarify the spatial boundaries for GI construction, and prohibit urban expansion from encroaching on ecologically sensitive areas.

- (2)

- Incorporate the SCS–GIS–MCDM system into blue–green space planning, and promote the quantitative implementation of the three-dimensional constraints of “water security–natural background–socio-economy”.

- (3)

- Promote the upgrading of China’s river basin governance from the single goal of flood control to synergistic development. With GI planning as a link, strive to build a paradigm for sustainable urban and community development.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix A.1. Calibration Results of 10 Rainfall Events in Changzhuang Reservoir Watershed

| Event No. | Date | Rainfall (P, mm) | Observed Q (mm) | Simulated Q (mm) | Relative Error (%) | NSE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 9 July 2016 | 102.1 | 55 | 55.66 | 1.2 | 0.81 |

| 2 | 19 July 2016 | 76.5 | 33.2 | 33.83 | 1.9 | 0.82 |

| 3 | 2 August 2017 | 54.6 | 8.7 | 8.92 | 2.5 | 0.83 |

| 4 | 19 August 2018 | 52.5 | 8.6 | 8.88 | 3.3 | 0.84 |

| 5 | 1 August 2019 | 90.2 | 46 | 47.89 | 4.1 | 0.85 |

| 6 | 4 July 2020 | 56.4 | 9.3 | 9.75 | 4.8 | 0.85 |

| 7 | 7 August 2020 | 88.5 | 40 | 42.48 | 6.2 | 0.86 |

| 8 | 20 July 2021 | 552.5 | 450 | 481.05 | 6.9 | 0.87 |

| 9 | 29 August 2021 | 78.6 | 35 | 37.84 | 8.1 | 0.87 |

| 10 | 25 July 2022 | 44.5 | 7 | 7.69 | 9.8 | 0.88 |

Appendix A.2. Localised CN Values for Land Use–Soil Combinations in Zhengzhou (AMC II)

| Land Use | Soil Texture | CN Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Construction land | Sandy soil | Coarse sand | 68 |

| Fine sand | 70 | ||

| Loam | Sandy loam | 79 | |

| Silt loam | 82 | ||

| Clay loam | Clay loam | 86 | |

| Silty clay loam | 88 | ||

| Clay soil | Heavy clay | 92 | |

| Light clay | 90 | ||

| Farmland | Sandy soil | Coarse sand | 62 |

| Fine sand | 65 | ||

| Loam | Sandy loam | 72 | |

| Silt loam | 75 | ||

| Clay loam | Clay loam | 80 | |

| Silty clay loam | 82 | ||

| Clay soil | Heavy clay | 85 | |

| Light clay | 83 | ||

| Forest land | Sandy soil | Coarse sand | 36 |

| Fine sand | 40 | ||

| Loam | Sandy loam | 55 | |

| Silt loam | 60 | ||

| Clay loam | Clay loam | 70 | |

| Silty clay loam | 72 | ||

| Clay soil | Heavy clay | 77 | |

| Light clay | 75 | ||

| Unused land | Sandy soil | Coarse sand | 77 |

| Fine sand | 80 | ||

| Loam | Sandy loam | 84 | |

| Silt loam | 86 | ||

| Clay loam | Clay loam | 88 | |

| Silty clay loam | 90 | ||

| Clay soil | Heavy clay | 91 | |

| Light clay | 90 | ||

| Water bodies | All soil types | 100 | |

References

- Xi, J. Speech at the Symposium on Ecological Protection and Quality Development of the Yellow River Basin. China Water Resour. 2019, 20, 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Lou, Y.; Yang, D.; Zhang, P.; Zhang, Y.; Song, M.; Huang, Y.; Jing, W. Multi-Scenario Simulation of Land Use Changes with Ecosystem Service Value in the Yellow River Basin. Land 2022, 11, 992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.-P.; Fu, B.-J.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, K.-B.; Zhao, M.M.; Ma, J.-F.; Wu, J.-H.; Xu, C.; Liu, W.-G.; Wang, H. Sustainable development in the Yellow River Basin: Issues and strategies. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 263, 121223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Niu, C.; Li, X.; Quan, L.; Li, W.; Liu, C.; Shi, C.; Soomro, S.-E.; Song, Q.; Hu, C. Modeling and Evaluating the Socio-Economic–Flood Safety–Ecological System of Landong Floodplain Using System Dynamics and the Weighted Coupling Coordination Degree Model. Water 2024, 16, 2366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Sun, X.; Zhang, X.; Wang, Y. Inter-regional ecological compensation in the Yellow River Basin based on the value of ecosystem services. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 322, 116073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Cheng, J.; Yin, C.; Li, Q.; Chen, R.; Fang, J. The extraordinary Zhengzhou flood of 7/20, 2021: How extreme weather and human response compounding to the disaster. Cities 2023, 134, 104168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacKenzie, K.M.; Singh, K.; Binns, A.D.; Whiteley, H.R.; Gharabaghi, B. Effects of urbanization on stream flow, sediment, and phosphorous regime. J. Hydrol. 2022, 612, 128283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IPCC. Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. In Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; IPCC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Q.; Qiao, J.J.; Li, M.J.; Huang, M.J. Spatiotemporal heterogeneity of ecosystem service interactions and their drivers at different spatial scales in the Yellow River Basin. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 908, 168486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, B.; Wu, Z.; Wang, H.; Guo, Y. Study on the Classification of Urban Waterlogging Rainstorms and Rainfall Thresholds in Cities Lacking Actual Data. Water 2020, 12, 3328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berland, A.; Shiflett, S.A.; Shuster, W.D.; Garmestani, A.S.; Goddard, H.C.; Herrmann, D.L.; Hopton, M.E. The role of trees in urban stormwater management. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2017, 162, 167–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, D.; O’Donnell, E.; Johnson, M.; Slater, L.; Thorne, C.; Zheng, S.; Stirling, R.; Chan, F.K.S.; Li, L.; Boothroyd, R.J. Green infrastructure: The future of urban flood risk management? WIREs Water 2021, 8, e21560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, F.; Ishiyama, N.; Yamanaka, S.; Higa, M.; Akasaka, T.; Kobayashi, Y.; Ono, S.; Fuke, N.; Kitazawa, M.; Morimoto, J.; et al. Adaptation to climate change and conservation of biodiversity using green infrastructure. River Res. Appl. 2020, 36, 921–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schubert, J.E.; Burns, M.J.; Fletcher, T.D.; Sanders, B.F. A framework for the case-specific assessment of Green Infrastructure in mitigating urban flood hazards. Adv. Water Resour. 2017, 108, 55–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Bergen, J.M. Green infrastructure for sustainable urban water management: Practices of five forerunner cities. Cities 2018, 74, 126–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pallathadka, A.; Sauer, J.; Chang, H.; Grimm, N.B. Urban flood risk and green infrastructure: Who is exposed to risk and who benefits from investment? A case study of three US Cities. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2022, 223, 104417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semeraro, T.; Scarano, A.; Buccolieri, R.; Santino, A.; Aarrevaara, E. Planning of Urban Green Spaces: An Ecological Perspective on Human Benefits. Land 2021, 10, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derkzen, M.L.; van Teeffelen, A.J.A.; Verburg, P.H. Green infrastructure for urban climate adaptation: How do residents’ views on climate impacts and green infrastructure shape adaptation preferences? Landsc. Urban Plan. 2017, 157, 106–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.; Song, S.-K. The Multifunctional Benefits of Green Infrastructure in Community Development: An Analytical Review Based on 447 Cases. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liberalesso, T.; Cruz, C.O.; Silva, C.M.; Manso, M. Green infrastructure and public policies: An international review of green roofs and green walls incentives. Land Use Policy 2020, 96, 104693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafique, M.; Kim, R. Green stormwater infrastructure with low impact development concept: A review of current research. Desalination Water Treat. 2017, 83, 16–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, R.; Malaviya, P. Management of stormwater pollution using green infrastructure: The role of rain gardens. WIREs Water 2021, 8, e1507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abhijith, K.V.; Kumar, P.; Gallagher, J.; McNabola, A.; Baldauf, R.; Pilla, F.; Broderick, B.; Di Sabatino, S.; Pulvirenti, B. Air pollution abatement performances of green infrastructure in open road and built-up street canyon environments—A review. Atmos. Environ. 2017, 162, 71–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieuwenhuijsen, M.J. Green Infrastructure and Health. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2021, 42, 317–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piracha, A.; Chaudhary, M.T. Urban Air Pollution, Urban Heat Island and Human Health: A Review of the Literature. Sustainability 2022, 14, 9234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomson, M.; Kumar, P.; Barwise, Y.; Perez, P.; Forehead, H.; French, K.; Morawska, L.; Watts, J.F. Green infrastructure for air quality improvement in street canyons. Environ. Int. 2021, 146, 106288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Palma, M.; Rigillo, M.; Leone, M.F. Remote Sensing Technologies for Mapping Ecosystem Services: An Analytical Approach for Urban Green Infrastructure. Sustainability 2024, 16, 6220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korkou, M.; Tarigan, A.K.M.; Hanslin, H.M. The multifunctionality concept in urban green infrastructure planning: A systematic literature review. Urban For. Urban Green. 2023, 85, 127975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeo, O.T.S.; Yusof, M.J.M.; Maruthaveeran, S.; Shafri, H.Z.M.; Saito, K.; Yeo, L.B. ABC of green infrastructure analysis and planning: The basic ideas and methodological guidance based on landscape ecological principle. Urban For. Urban Green. 2022, 73, 127600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartlett, M.S.; Parolari, A.J.; McDonnell, J.J.; Porporato, A. Beyond the SCS-CN method: A theoretical framework for spatially lumped rainfall-runoff response. Water Resour. Res. 2016, 52, 4608–4627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lotz, T.; Sun, Z.; Xue, B. Evaluation of soil-vegetation interaction effects on water fluxes revealed by the proxy of model parameter combinations. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2023, 195, 283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, B.; Wang, Q.-H.; Fan, J.; Han, F.-P.; Dai, Q.-H. Application of the SCS-CN Model to Runoff Estimation in a Small Watershed with High Spatial Heterogeneity. Pedosphere 2011, 21, 738–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arya, S.; Kumar, A. Green Infrastructure for Sustainable Stormwater Management in an Urban Setting Using SWMM-Based Multicriteria Decision-Making Approach. J. Hydrol. Eng. 2024, 29, 04023044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amatya, D.M.; Walega, A.; Callahan, T.J.; Morrison, A.; Vulava, V.; Hitchcock, D.R.; Williams, T.M.; Epps, T. Storm event analysis of four forested catchments on the Atlantic coastal plain using a modified SCS-CN rainfall-runoff model. J. Hydrol. 2022, 608, 127772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, W.; Jiao, J.; Du, P.; Liu, H. Optimizing the soil conservation service curve number model by accounting for rainfall characteristics: A case study of surface water sources in Beijing. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2021, 193, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Zhao, X.; Li, F.; Zhao, W.; Awuku, I.; Ma, W.; Liu, Q.; Liu, B.; Cai, T.; Liu, Y.; et al. Optimized parameters for SCS-CN model in runoff prediction in ridge-furrow rainwater harvesting in semiarid regions of China. Agric. Water Manag. 2025, 310, 109363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunawardena, K.R.; Wells, M.J.; Kershaw, T. Utilising green and bluespace to mitigate urban heat island intensity. Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 584–585, 1040–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norton, B.A.; Coutts, A.M.; Livesley, S.J.; Harris, R.J.; Hunter, A.M.; Williams, N.S.G. Planning for cooler cities: A framework to prioritise green infrastructure to mitigate high temperatures in urban landscapes. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2015, 134, 127–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Davitt-Liu, I.; Erickson, A.J.; Feng, X. Integrating the Spatial Configurations of Green and Gray Infrastructure in Urban Stormwater Networks. Water Resour. Res. 2023, 59, e2023WR034796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeedi, I.; Tabrizi, A.R.M.; Bahremand, A.; Salmanmahiny, A. Planning and optimization of green infrastructures for stormwater management: The case of Tehran West Bus Terminal. Nat. Resour. Model. 2023, 36, e12378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramyar, R.; Ackerman, A.; Johnston, D.M. Adapting cities for climate change through urban green infrastructure planning. Cities 2021, 117, 103316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.; Diao, H.; Wang, J.; Jia, W.; Xu, H.; Xu, X.; Wang, M.; Sun, C.; Qiao, R.; Wu, Z. Multi-stage optimization framework for synergetic grey-green infrastructure in response to long-term climate variability based on shared socio-economic pathways. Water Res. 2025, 274, 123091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garen, D.C.M.; Daniel, S. Curve Number Hydrology in Water Quality Modeling: Uses, Abuses, and Future Directions. J. Am. Water Resour. Assoc. 2005, 41, 377–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, K.X.; Shen, S.; Cheng, C.X.; Song, Y.G. Integrated evaluation and attribution of urban flood risk mitigation capacity: A case of Zhengzhou, China. J. Hydrol.-Reg. Stud. 2023, 50, 101567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhengzhou Municipal Bureau of Statistics. Report on Zhengzhou’s Population Status in 2024; Zhengzhou Municipal Bureau of Statistics: Zhengzhou, China, 2024.

- Jin, Z.; Yu, J.; Dai, K. Topographic Elevation’s Impact on Local Climate and Extreme Rainfall: A Case Study of Zhengzhou, Henan. Atmosphere 2024, 15, 234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Ye, S.; Wu, Q.; Wu, Y.; Qian, S. Analysis and countermeasures of the “7.20” flood in Zhengzhou. J. Asian Archit. Build. Eng. 2023, 22, 3782–3798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Yang, M.; Wang, H.; Liu, K.; Dong, N.; Wang, H.; Zhang, L.; Fan, W. Moisture sources and atmospheric circulation associated with the record-breaking rainstorm over Zhengzhou city in July 2021. Nat. Hazards 2023, 116, 817–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Chen, Y.; Nie, J.; Yan, Z.; Zhai, P.; Feng, J. On the role of anthropogenic warming and wetting in the July 2021 Henan record-shattering rainfall. Sci. Bull. 2022, 67, 2055–2059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- State Council Disaster Investigation Team. Investigation Report on the “7·20” Extraordinary Heavy Rain Disaster in Zhengzhou, Henan; State Council Disaster Investigation Team: Beijing, China, 2022.

- Deshmukh, D.S.; Chaube, U.C.; Hailu, A.E.; Gudeta, D.A.; Kassa, M.T. Estimation and comparision of curve numbers based on dynamic land use land cover change, observed rainfall-runoff data and land slope. J. Hydrol. 2013, 492, 89–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, F.; Deng, Y.; Hu, X.; Weng, Q. Estimating Composite Curve Number Using an Improved SCS-CN Method with Remotely Sensed Variables in Guangzhou, China. Remote Sens. 2013, 5, 1425–1438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tramblay, Y.; Bouvier, C.; Martin, C.; Didon-Lescot, J.-F.; Todorovik, D.; Domergue, J.-M. Assessment of initial soil moisture conditions for event-based rainfall–runoff modelling. J. Hydrol. 2010, 387, 176–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beskow, S.; Mello, C.R.D.; Coelho, G.; Silva, A.M.D.; Viola, M.R. Estimativa do escoamento superficial em uma bacia hidrográfica com base em modelagem dinâmica e distribuída. Rev. Bras. Ciência Solo 2009, 33, 169–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, Y.; Engel, B.A. Spatially distributed long-term hydrologic simulation using a continuous SCS CN method-based hybrid hydrologic model. Hydrol. Process. 2018, 32, 904–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, L.; Yin, J.; Zhang, H.; Wang, H.-M.; Yang, G.; Wu, X. On future flood magnitudes and estimation uncertainty across 151 catchments in mainland China. Int. J. Climatol. 2021, 41, E779–E800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, W.; Hao, Z.; Yuan, F.; Ju, Q.; Hao, J. Regional Frequency Analysis of Precipitation Extremes and Its Spatio-Temporal Patterns in the Hanjiang River Basin, China. Atmosphere 2019, 10, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, H.; Wang, D.; Ji, Q. Research on Urbanization and Ecological Environmental Response: A Case Study of Zhengzhou City. Sustainability 2025, 17, 458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhengzhou Bureau of Natural Resources and Planning. Overall Land and Space Plan of Zhengzhou City (2021–2035); Zhengzhou Bureau of Natural Resources and Planning: Zhengzhou, China, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Costache, R.; Zaharia, L. Flash-flood potential assessment and mapping by integrating the weights-of-evidence and frequency ratio statistical methods in GIS environment—Case study: Basca Chiojdului River catchment (Romania). J. Earth Syst. Sci. 2017, 126, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, S.K.; Singh, S.K.; Gupta, M.; Srivastava, P.K. Morphometric analysis of Upper Tons basin from Northern Foreland of Peninsular India using CARTOSAT satellite and GIS. Geocarto Int. 2014, 29, 895–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svoray, T.; Karnieli, A. Rainfall, topography and primary production relationships in a semiarid ecosystem. Ecohydrology 2011, 4, 56–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, J.; Lin, G.; Huang, G. Evaluation of the cost-effectiveness of Green Infrastructure in climate change scenarios using TOPSIS. Urban For. Urban Green. 2021, 64, 127287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mojaddadi, H.; Pradhan, B.; Nampak, H.; Ahmad, N.; bin Ghazali, A.H. Ensemble machine-learning-based geospatial approach for flood risk assessment using multi-sensor remote-sensing data and GIS. Geomat. Nat. Hazards Risk 2017, 8, 1080–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khosravi, K.; Nohani, E.; Maroufinia, E.; Pourghasemi, H.R. A GIS-based flood susceptibility assessment and its mapping in Iran: A comparison between frequency ratio and weights-of-evidence bivariate statistical models with multi-criteria decision-making technique. Nat. Hazards 2016, 83, 947–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahmati, O.; Pourghasemi, H.R.; Zeinivand, H. Flood susceptibility mapping using frequency ratio and weights-of-evidence models in the Golastan Province, Iran. Geocarto Int. 2016, 31, 42–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grabowski, Z.J.; McPhearson, T.; Pickett, S.T.A. Transforming US urban green infrastructure planning to address equity. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2023, 229, 104591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, J.; Russo, A. Exploring the role of public participation in delivering inclusive, quality, and resilient green infrastructure for climate adaptation in the UK. Cities 2024, 148, 104879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Wang, X.; Wu, X.; Guo, J.; Zhou, Z. Influence of roadside vegetation barriers on air quality inside urban street canyons. Urban For. Urban Green. 2021, 63, 127219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank, L.D.; Hong, A.; Ngo, V.D. Causal evaluation of urban greenway retrofit: A longitudinal study on physical activity and sedentary behavior. Prev. Med. 2019, 123, 109–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, P.; Cao, H.; Sun, W.; Chen, X. Quantitative evaluation of the rebuilding costs of ecological corridors in a highly urbanized city: The perspective of land use adjustment. Ecol. Indic. 2022, 141, 109130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulshad, K.; Szydlowski, M.; Yaseen, A.; Aslam, R.W. A comparative analysis of methods and tools for low impact development (LID) site selection. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 354, 120212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khosravi, K.; Shahabi, H.; Pham, B.T.; Adamowski, J.; Shirzadi, A.; Pradhan, B.; Dou, J.; Ly, H.-B.; Gróf, G.; Ho, H.L.; et al. A comparative assessment of flood susceptibility modeling using Multi-Criteria Decision-Making Analysis and Machine Learning Methods. J. Hydrol. 2019, 573, 311–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, S.; Zhao, H. Fuzzy best-worst multi-criteria decision-making method and its applications. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2017, 121, 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaei, J. Best-worst multi-criteria decision-making method. Omega 2015, 53, 49–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaei, J. Best-worst multi-criteria decision-making method: Some properties and a linear model. Omega 2016, 64, 126–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghaloo, K.; Sharifi, A. A GIS-based agroecological model for sustainable agricultural production in arid and semi-arid areas: The case of Kerman Province, Iran. Curr. Res. Environ. Sustain. 2023, 6, 100230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabati, J.; Nezami, A.; Neamatollahi, E.; Akbari, M. GIS-based agro-ecological zoning for crop suitability using fuzzy inference system in semi-arid regions. Ecol. Indic. 2020, 117, 106646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tirpakova, A.; Vojtekova, J.; Vojtek, M.; Vlkolinska, I. Using Fuzzy Logic to Analyze the Spatial Distribution of Pottery in Unstratified Archaeological Sites: The Case of the Pobedim Hillfort (Slovakia). Land 2021, 10, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haile, M.M. Approaches for Delineating Groundwater Recharge Potential Zone Using Fuzzy Logic Model. Geofluids 2022, 2022, 3637230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baharvand, S.; Rahnamarad, J.; Soori, S.; Saadatkhah, N. Landslide susceptibility zoning in a catchment of Zagros Mountains using fuzzy logic and GIS. Environ. Earth Sci. 2020, 79, 204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borgonovo, E.; Plischke, E. Sensitivity analysis: A review of recent advances. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2016, 248, 869–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pianosi, F.; Beven, K.; Freer, J.; Hall, J.W.; Rougier, J.; Stephenson, D.B.; Wagener, T. Sensitivity analysis of environmental models: A systematic review with practical workflow. Environ. Model. Softw. 2016, 79, 214–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, J.; Zhang, Y.; Xiong, L.; He, S.; Wang, L.; Yu, Z. Opportunities and challenges of the Sponge City construction related to urban water issues in China. Sci. China-Earth Sci. 2017, 60, 652–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Xu, J.; Lu, M.; Ming, H. An integrated modelling framework for optimization of the placement of grey-green-blue infrastructure to mitigate and adapt flood risk: An application to the Upper Ting River Watershed, China. J. Hydrol. Reg. Stud. 2025, 57, 102156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhengzhou Bureau of Natural Resources and Planning. Zhengzhou Territorial Spatial Ecological Restoration Plan (2021–2035); Zhengzhou Bureau of Natural Resources and Planning: Zhengzhou, China, 2024.

- Fan, Y.; Fang, C.; Zhang, Q. Coupling coordinated development between social economy and ecological environment in Chinese provincial capital cities-assessment and policy implications. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 229, 289–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Data Type | Data Name | Year(s) | Resolution/Scale | Data Preprocessing |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Remote Sensing | Landsat 8 | 2017; 2020; 2021 | 30 m | Visual interpretation; Local calibration |

| Topographic | DEM | 2018 | 30 m | Verification |

| Soil | Soil Classification Vector Map | - | 1:200,000 | Soil property table; Reclassification; |

| Meteorological | Extreme Heavy Rainfall Days | 2016–2022 | - | None |

| Hydrological | Water Level and Flood Discharges of Changzhuang Reservoir | (rainstorm days) | - | Calculate inflow volume |

| Socio-economic | Administrative Boundary Map Vector Map of Traffic Network | 2022 2023 | 1:100,000 | Data integration Format conversion |

| Rainfall Frequency | Maximum 1 h Rainfall | Maximum 6 h Rainfall | Maximum 24 h Rainfall |

|---|---|---|---|

| 50% | 39.3 mm | 58.8 mm | 85.2 mm |

| 10% | 75.9 mm | 120.4 mm | 169.9 mm |

| 2% | 111.7 mm | 180.9 mm | 251.1 mm |

| Elevation | Slope | Aspect | NDVI | Soil Texture | Inundated Area | Runoff Corridor | Land Use | Traffic Buffer | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Best-to-Others (BO) | 8 | 6 | 9 | 3 | 7 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 5 |

| Others-to-Worst (OW) | 2 | 3 | 1 | 7 | 5 | 8 | 8 | 7 | 6 |

| Criteria | Sub-Criteria | Weights (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Natural conditions | Elevation | 4.52% |

| Slope | 6.88% | |

| Aspect | 2.91% | |

| NDVI | 11.44% | |

| Soil texture | 5.68% | |

| Flood security | Inundated area | 32.13% |

| Runoff corridor | 15.73% | |

| Social economy | Land use | 12.44% |

| Traffic buffer | 8.26% |

| Suitability Class | Index Type | γ = 0.80 | γ = 0.90 (Benchmark) | γ = 0.95 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Highly Suitable | Area Proportion | 12.5% | 6.8% | 5% |

| Overlap with Benchmark | 100% | - | 74% | |

| Moderately Suitable | Area Proportion | 50.3% | 40.8% | 35.1% |

| Overlap with Benchmark | 86% | - | 82% | |

| Less Suitable | Area Proportion | 35.5% | 46.4% | 50.6% |

| Overlap with Benchmark | 67% | - | 93% | |

| Not Suitable | Area Proportion | 1.7% | 6% | 9.3% |

| Overlap with Benchmark | 28% | - | 100% |

| Criteria | Sub-Criteria | Benchmark Weight Value | Disturbance Range |

|---|---|---|---|

| Flood security | Inundated area | 32.13% | ±10% |

| Flood security | Runoff corridor | 15.73% | ±10% |

| Socio-economic | Land use | 12.44% | ±8% |

| Suitability Class | CV | Variance | Independent Factor Contribution (%) | Synergistic Factor Contribution (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Highly suitable | 0.165 | 0.0102 | Runoff corridor (38%); Land use (32%) | Runoff corridor × Land use (28%) |

| Moderately suitable | 0.103 | 0.0045 | Inundated area (25%); Land use (19%) | Inundated area × Land use (9%) |

| Less suitable | 0.087 | 0.0032 | Runoff corridor (18%); Inundated area (14%) | Runoff corridor × Inundated area (6%) |

| Not suitable | 0.213 | 0.0182 | Inundated area (65%); Land use (12%) | Inundated area × Land use (25%) |

| Ecological Control Zone | Non-Ecological Control Zone | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Highly suitable | 273.6 | 239.1 | 512.7 |

| Moderately suitable | 1922.5 | 1167.4 | 3089.9 |

| Less suitable | 511.7 | 3000.6 | 3512.3 |

| Not suitable | 76.7 | 374.4 | 451.1 |

| Total | 2784.5 | 4781.5 | 7566 |

| Ecological Control Zone (Planning Objective: Adapt to High Suitability) | Non-Ecological Control Zone (Planning Objective: Adapt to Low Suitability) | |

|---|---|---|

| Highly suitable | 1 | 1/9 |

| Moderately suitable | 1 | 1/4 |

| Less suitable | 1/4 | 1 |

| Not suitable | 1/9 | 1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the International Society for Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, K.; Wang, Z.; Fan, Y.; Wu, Y. A Comprehensive Modelling Framework for Identifying Green Infrastructure Layout in Urban Flood Management of the Yellow River Basin. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2025, 14, 414. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijgi14110414

Wang K, Wang Z, Fan Y, Wu Y. A Comprehensive Modelling Framework for Identifying Green Infrastructure Layout in Urban Flood Management of the Yellow River Basin. ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information. 2025; 14(11):414. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijgi14110414

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Kai, Zongyang Wang, Yongming Fan, and Yan Wu. 2025. "A Comprehensive Modelling Framework for Identifying Green Infrastructure Layout in Urban Flood Management of the Yellow River Basin" ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information 14, no. 11: 414. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijgi14110414

APA StyleWang, K., Wang, Z., Fan, Y., & Wu, Y. (2025). A Comprehensive Modelling Framework for Identifying Green Infrastructure Layout in Urban Flood Management of the Yellow River Basin. ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information, 14(11), 414. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijgi14110414