1. Introduction

Geographical Information Systems (GISs) play a pivotal role in modern science and decision-making [

1], offering powerful tools for visualizing, analyzing, and interpreting spatial data [

2,

3]. The potential applications of GISs are extensive, ranging from urban planning and environmental monitoring to disaster management and logistics [

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9]. The insights derived from GISs are instrumental in informing evidence-based decisions [

10,

11]. The ability to analyze spatial patterns, model complex processes, and visualize relationships within a geographical context has made GISs an indispensable component of various fields, including public health [

12,

13], transportation [

14], and natural resource management [

15,

16]. GIS has become a cornerstone of modern analytical frameworks by allowing users to connect spatial data with real-world phenomena [

17,

18,

19,

20].

Nevertheless, despite their extensive capabilities, traditional GIS platforms face notable limitations in terms of flexibility and adaptability [

21,

22,

23]. The majority of GIS software is designed with predefined workflows and rigid interfaces, which are often tailored to specific tasks. While this approach ensures efficiency for routine operations, it restricts users when attempting to address nonstandard or highly complex spatial questions [

24,

25]. The execution of such tasks frequently necessitates the implementation of bespoke solutions, the possession of extensive technical expertise, and a profound comprehension of GIS functionalities [

25,

26]. Traditional GISs, with their steep technical requirements, have often excluded users without specialized knowledge in spatial analysis, programming, or database management [

25]. This exclusion has curtailed the potential of GIS insights to inform a broader range of disciplines and decision-making contexts. The general approach to the resolution of geographical problems involves the sequential combination of various GIS tools [

27,

28,

29,

30]. The employment of these tools is intended to address specific sub-goals, which collectively contribute to the identification of an optimal solution [

31].

The advent of Large Language Models (LLMs) represents a transformative opportunity to overcome these limitations. LLMs, with their exceptional natural language understanding and reasoning abilities [

32,

33], have demonstrated significant potential to address challenges in various fields [

34,

35,

36]. LLMs, when trained on extensive datasets, have been shown to possess proficiency in interpreting unstructured text, generating contextually relevant outputs, and engaging in complex problem-solving tasks [

32,

37,

38]. The integration of the chain-of-thought strategy has further augmented the planning and reasoning capabilities of LLMs, empowering them to address complex tasks with greater efficacy [

31,

39,

40] as this provided us motivation to look into the direction of an open-source solution which posses such capability. This approach encourages LLMs to methodically reason through problems, generating a sequence of intermediate reasoning steps to arrive at a solution, rather than providing a direct answer or solving the problem in a single step [

41,

42]. These characteristics position LLMs as powerful tools for improving the flexibility of GISs, enabling them to better address the needs of spatial analysis [

43] and also be useful in terms of detecting minor errors though such reasoning. The integration of LLMs into GIS applications represents a pivotal development, as it addresses long-standing challenges that have historically limited the accessibility, adaptability, and innovation of the field [

44,

45,

46]. By enabling natural language interactions, LLMs serve to reduce the technical barriers that have historically limited the uptake of GISs by users from diverse backgrounds, including policymakers, educators, and community planners. These users can now engage with GIS tools and leverage the potential of spatial data without the need for extensive training [

10,

47], with additional benefits if they are provided with a simple user interface. Additionally, LLMs enhance GIS platforms by addressing the complexity and flexibility required to tackle non-standard queries [

44,

48,

49]. Many real-world spatial problems resist rigid workflows or predefined commands, demanding nuanced reasoning and iterative exploration. LLMs excel at interpreting complex, context-rich inquiries and providing users with guidance through adaptive, conversational workflows [

50,

51]. This capability enables users to refine their queries, explore alternative approaches, and engage in deeper analysis, aligning more closely with their specific objectives. Consequently, LLMs have the potential to provide a more dynamic and responsive GIS experience [

26,

31,

52] that is better equipped to handle the breadth of modern spatial inquiries. LLMs have the capacity to function as a pivotal conduit between GIS experts and non-specialists [

53,

54], thereby facilitating collaboration and communication across diverse teams [

55]. By translating technical outputs into comprehensible language, LLMs ensure that spatial insights are both comprehensible and actionable [

33,

52], thereby fostering better decision-making and promoting cross-disciplinary partnerships. These enhancements, therefore, not only increase access to GIS tools but also elevate their relevance in addressing complex challenges in science, governance, and industry [

56,

57].

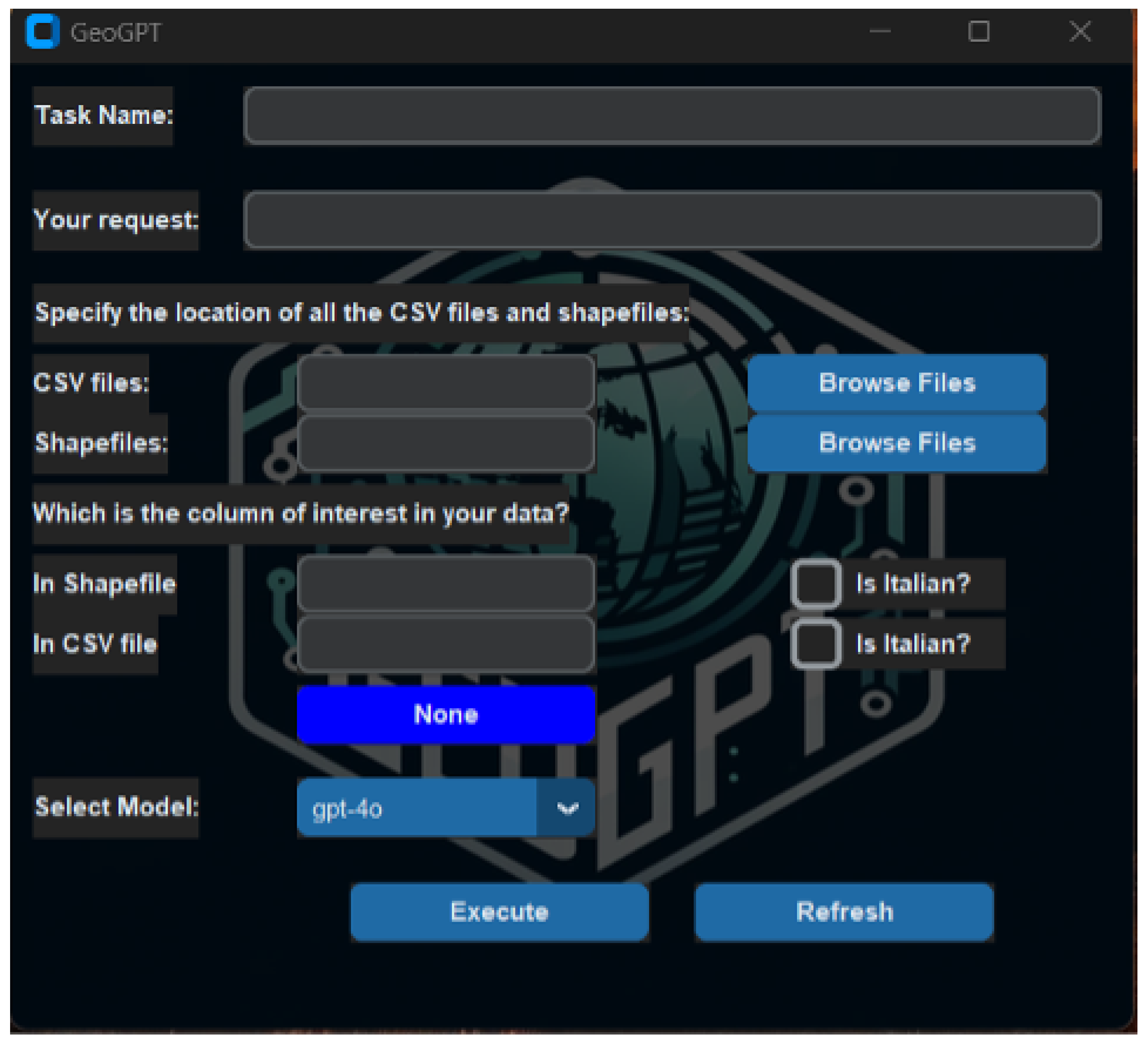

In this context, we propose an approach based on the methodology introduced by [

31], an innovative AI-driven framework aimed at transforming GISs by integrating LLMs, specifically GPT-4 and the open-source DeepSeek-R1-70B, to automate and simplify geospatial analysis. The primary objective is to enhance accessibility of GIS workflows by eliminating manual coding and allowing users to interact with the system through natural language. To achieve this, our system automatically translates user instructions into executable GIS workflows, reducing complexity and minimizing human error. A distinctive feature of our approach is the intuitive graphical user interface (GUI), developed with CustomTkinter, enabling users to configure analyses, select dataset locations, and visualize results in real-time, all without detailed technical knowledge of traditional GIS software.

Our system is distinct from general-purpose frameworks such as LangChain or SmolAgents that generate and run code from natural language, our system introduces several domain adaptations tailored for GIS tasks. First, we use GIS-specific prompts and structured requirement rather than relying on the base LLM alone. This ensures every generated script follows correct spatial data handling practices (for example, using gpdṙead_file for shapefiles or maintaining projection consistency). Second, the system performs multi-stage validation and auto-debugging. It does not stop at code generation, but actively reviews and debugs the code using the LLM in a loop until the code executes without errors. This level of automated error correction is often absent in simpler agent frameworks. Third, we incorporate a workflow graph construction phase, the LLM’s plan is captured as a graph of operations and data, using NetworkX to manage execution flow. Typical agents treat each user query in isolation, but our graph-based approach gives the user transparency (they can inspect the graph of how their task will be performed) and allows better control over complex multi-step processes. Together, these innovations contribute to a system that is more reliable and domain-aligned than off-the-shelf code generation agents. In other words, our framework explicitly addresses GIS domain requirements and robustness, thereby reducing common failures (such as data misalignment or hallucinated functions) that one might encounter if using a generic agent without such adaptations.

A major technical contribution of this research is the integration of dynamic prompt engineering directly within a lightweight GUI. Specifically, we developed an interactive front-end using CustomTkinter that empowers users to naturally specify geospatial analysis requests. Unlike conventional static prompting methods, our system dynamically constructs context-sensitive prompts by capturing real-time user inputs, including dataset paths, columns of interest (optional), language preferences, and customized task instructions. This real-time prompt generation significantly enhances user interaction, ensuring accurate, context-aware execution by the underlying language models. The GUI also supports flexible selection of language models based an open-source or paid API’s, robust error detection, and automated workflow generation, effectively bridging technical gaps and making complex GIS analyses accessible to a broad range of users. Our system also incorporates automatic error correction mechanisms as mentioned before, for example, missing coordinates or misaligned reference systems, thereby improving analytical reliability. To evaluate our method, we conducted a case study utilizing urban data from Pesaro, Italy, where the attribute names in the dataset were in both English and Italian, which was the reason for adding the options of selecting the language and the column. The automated system generated building height maps and complex shape files, analysed historical urban development, and computed distance buffers from the urban centre. These results were directly compared to the outcomes of identical tasks manually conducted by 10 GIS experts using QGIS software. This comparative analysis being a part of evaluation process indicated that our automated approach substantially reduces task completion time while maintaining accuracy. Subjective feedback from the GIS experts was also collected to assess usability, perceived accuracy, and challenges encountered during manual operations. The evaluation provided clear evidence of the automated system’s practical advantages, highlighting its potential to enhance efficiency, speed, and the accessibility of geospatial analysis for expert and non-expert users alike. In-depth details of the case study are included in

Section 4.

The main contributions of the paper can be summarized as follows:

- 1.

LLM-powered GIS workflow automation—we developed a method to translate natural language GIS queries into executable geoprocessing workflows. Our system integrates state-of-the-art LLMs (GPT-4 and the open-source DeepSeek-R1-70B, released under an MIT license) with a suite of GIS operations. It features an intuitive GUI for specifying tasks and viewing results, and it automates data preparation and error-handling (e.g., shapefile validation, CSV integration, and iterative code debugging via the LLM). This approach greatly reduces the need for coding or GIS expertise, minimizes human error, and enables even non-expert users to perform complex spatial analyses.

- 2.

Comprehensive evaluation—we rigorously evaluated the system through an urban GIS case study (Pesaro, Italy). We compared the LLM-driven workflow against traditional manual GIS processing by 10 domain experts, assessing performance, accuracy, and efficiency. The results show a significant reduction in task completion time without compromising accuracy. Furthermore, we systematically tested the system’s factual reliability on 30 diverse geospatial queries.

2. Related Works

The integration of LLMs with geospatial analysis has emerged as a rapidly evolving field, driven by the increasing demand to process and interpret spatial data through natural language. Recent studies have focused particularly on natural language interfaces for GISs, the adaptation of LLMs to geospatial workflows, and the evaluation of their reliability in geospatial reasoning.

One of the primary challenges of applying LLMs to geospatial tasks is their lack of inherent spatial awareness. While general-purpose LLMs like GPT-4 exhibit strong natural language understanding, they are not explicitly trained to handle geospatial semantics, relationships, or reasoning tasks. To address this, several studies have focused on fine-tuning or extending LLMs with domain-specific data and methodologies. The work of Zhang et al. [

58] is foundational to demonstrate how LLMs can be adapted for geospatial applications. This study proposes a framework that incorporates spatial reasoning tasks, geographic entity embeddings, and geospatial taxonomies into the training pipeline, significantly improving performance over baseline LLMs. By leveraging GIS datasets, the model is able to perform entity recognition, spatial relationship extraction, and location-based inference with greater accuracy than general LLMs. Building upon these advancements, Zhang et al. [

31] extend this approach by integrating an interactive framework that enables users to query and manipulate geospatial data using natural language. This system incorporates geospatial knowledge retrieval, task execution, and visualization capabilities, offering a practical solution for applying LLMs in GIS-related workflows. The ability to interpret queries, retrieve relevant data, and execute multi-step operations directly informs our own approach of generating executable workflows.

A critical challenge in geospatial AI is the gap between unstructured natural language and structured spatial databases. While LLMs have proven effective in processing text, they encounter significant challenges when it comes to directly interfacing with geospatial data infrastructures such as GISs, spatial databases, and remote sensing platforms. Addressing this challenge is the focus of the study by Naveen et al. [

25] which proposes the development of sophisticated natural language understanding techniques specifically designed for geospatial queries. The proposed approach involves a structured query translation technique, whereby LLMs are trained to interpret natural language queries into formalized geospatial query languages, such as SQL-based GIS queries or spatial filtering commands. The results of the study demonstrate a significant enhancement in the capacity of LLMs to interact with existing geospatial infrastructures, thereby reducing the barriers to entry for non-expert users who require access to spatial data. Similarly, Roberts et al. [

59] investigated the internal representations of geographic entities in LLMs. By analysing the manner in which models encode spatial relationships, such as proximity, containment, and topological relations, this study explores the extent to which LLMs can “understand” geography without explicit geospatial training. The findings suggest that while LLMs capture certain spatial patterns through statistical correlations, they require additional fine-tuning or external knowledge integration to achieve robust geographic reasoning. This work provides key insights into the limitations of existing LLMs and the need for more structured geospatial training paradigms.

The increasing use of LLMs in geospatial applications necessitates the establishment of rigorous evaluation frameworks to assess their performance. Mooney et al. [

44] systematically evaluated ChatGPT’s ability to handle a variety of geospatial tasks, including location-based question answering, geographic entity disambiguation, and spatial reasoning. The study employs a controlled testing framework, benchmarking ChatGPT against standard GIS tools and domain-specific models. While the results highlight ChatGPT’s potential in handling basic geospatial queries, they also expose weaknesses in multi-step reasoning and spatial inference tasks, underscoring the need for more specialized training. In addition to this evaluation, Manvi et al. [

60] explore techniques for distilling geospatial knowledge from pre-trained models. The study finds that while LLMs can recognize and generate geographic data with an acceptable level of accuracy, their ability to perform complex geospatial reasoning remains limited. To address this, the authors propose fine-tuning strategies and knowledge enhancement mechanisms that increase the model’s ability to retrieve and apply geospatial knowledge in diverse scenarios.

Two comprehensive reviews provide a broader context for the rapid advancements in geospatial AI. In particular, the review by Hadi et al. [

34] presents an extensive analysis of the current state of LLM research, detailing significant breakthroughs, emerging challenges, and anticipated future developments. The review highlights the increasing role of LLMs in specialized domains, including geospatial analysis, and underscores the necessity for continued research in multimodal learning, model interpretability, and domain-specific adaptation. Focusing specifically on geospatial AI, Wang et al. [

61] provide a structured examination of existing studies on LLMs in GIS applications. By synthesizing findings from multiple research efforts, this review identifies core research themes; persistent challenges, such as the integration of structured spatial data with unstructured textual inputs; and future directions for improving geospatial AI systems. These studies illustrate a rapidly maturing field in which LLMs are increasingly adapted to geospatial tasks through domain-specific training, improved natural language interfaces, and advanced evaluation frameworks. The progression from basic language understanding to more sophisticated geospatial reasoning is evident in works such as BB-GeoGPT, GeoGPT, and GeoNLU, while interpretability studies like GPT4GEO and GEOLLM shed light on the underlying capabilities and limitations of existing models. Within this context, our work contributes by operationalizing NL–GIS requests through an lightweight and easy interface into executable workflows, integrating error-handling and CRS safeguards, and empirically validating performance against human experts.

3. Materials

and Methods

3.1. Overview of Our System Framework

The proposed GIS automation system integrates advanced LLMs with a modular geospatial operations library to translate natural language queries into fully executable GIS workflows The source code is available at:

https://github.com/NikhilMuralikrishna/GIS-LLM_Project accessed on 6 October 2025. The system has been developed on the basis of the GeoGPT framework [

31]. It has been designed to enhance natural language interpretation, extend automation capabilities, and introduce a user-friendly interface for handling diverse datasets, including shapefiles and CSV files. The system is utilised by users via a GUI that is based on CustomTkinter, which captures task descriptions, datasets, selected attributes, and user preferences such as the desired output language. This input is then programmatically transformed into structured prompts for the LLM. The model interprets the query, identifies the necessary geospatial operations, and generates both a Python script and an intermediate workflow graph, detailing each analytical step. The system enables the review of these intermediate steps prior to execution, thereby ensuring transparency and verification of the generated workflow. Internally, a dedicated solution class orchestrates the process, combining user inputs with predefined system instructions (prompts) to guide the LLM.

The core workflow consists of three integrated modules: natural language processing, dynamic workflow generation, and geospatial task execution. LLMs such as GPT-4 or the open-source DeepSeek-R1-70B parse queries expressed in natural language and map them to structured GIS operations, leveraging the system’s curated library for both basic and advanced spatial analysis.

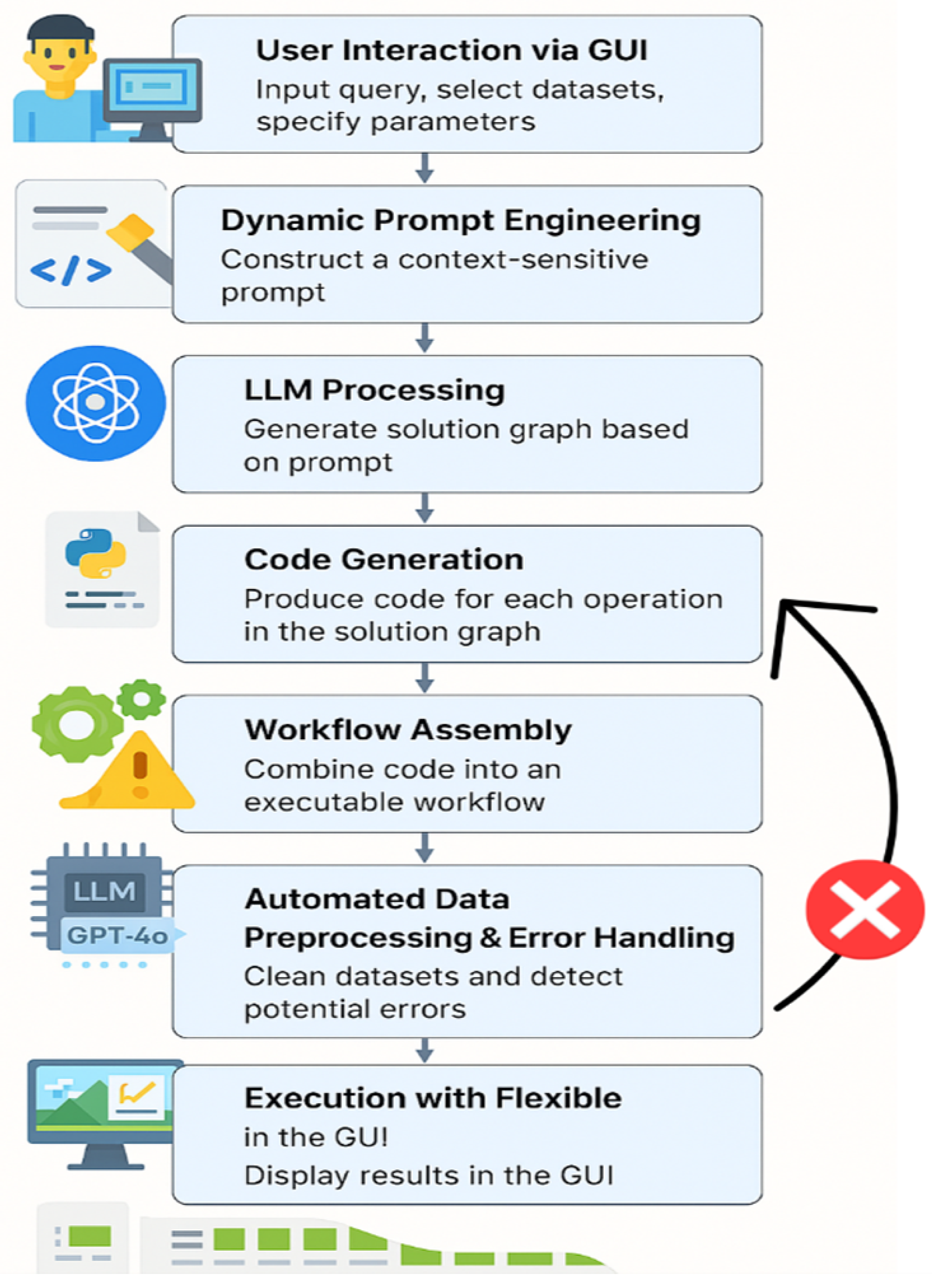

The flowchart in

Figure 1 illustrates the logical sequence and interactions among the key components of our system. The workflow begins with the user interacting with the CustomTkinter-based GUI, where tasks are specified in natural language along with a task name. The GUI captures user inputs, including datasets, relevant attributes, and task-specific parameters, which are then dynamically transformed into context-sensitive prompts. These prompts are processed by either GPT-4 or DeepSeek-R1, depending on the selected model. The LLM interprets the user’s instructions, identifies the necessary geospatial operations, and generates structured workflows represented as solution graphs. Each solution graph explicitly defines the geospatial processing steps, such as spatial joins, buffering, and thematic mapping, which are subsequently converted into executable Python scripts via the execution engine. The generated outputs undergo robust error detection and correction procedures to automatically handle inconsistencies or inaccuracies. Once validated, results—including shapefiles, maps, and tables—are saved in the designated directory and displayed through the GUI, enabling immediate visualization. Users can iteratively refine their tasks via dynamic prompt updates, ensuring flexibility and precision in subsequent workflow executions.

3.2. System Architecture and Component Interactions

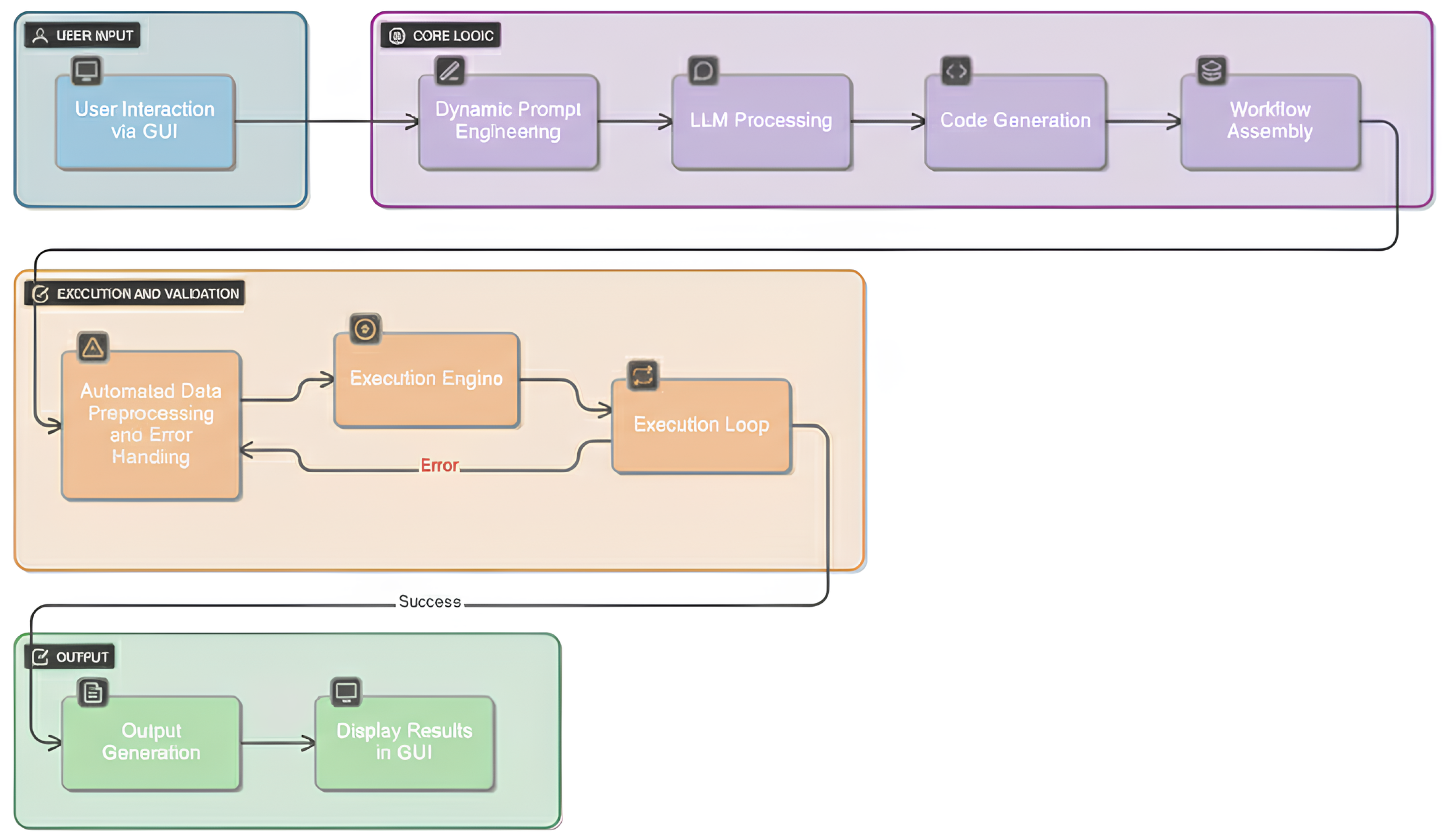

The architecture of the proposed LLM-powered GIS is illustrated in

Figure 2. The workflow is organized into four stages: (i) user input through a graphical interface, (ii) core logic driven by dynamic prompt engineering and LLM processing, (iii) execution and validation with automated preprocessing and error handling, and (iv) output generation and visualization.

3.2.1. Language Model Integration

The integration of LLMs into our GIS enables the automated interpretation of natural language queries and their translation into structured geospatial workflows. LLMs, such as GPT-4 and DeepSeek-R1-70B, process user inputs by extracting semantic meaning, identifying relevant spatial entities, and understanding contextual relationships within the data. For example, a query like “Show areas of high vegetation density near rivers’’ is decomposed into actionable elements, including dataset selection, spatial buffering, attribute filtering, and visualization, which form the building blocks of the geospatial workflow. The system leverages the LLM’s chain-of-thought reasoning to construct solution graphs, which are sequential representations of GIS operations necessary to fulfil the user’s request. These graphs ensure that the generated workflows are logically sound, scalable, and adaptable to varying complexities of geospatial tasks.

The integration of GIS domain expertise in our system is achieved through careful prompt engineering and structured knowledge injection, rather than by altering the LLM’s parameters. In practice, the system’s back end provides the LLM with prompts that reflect geospatial terminology, constraints, and best practices. For example, the prompt templates explicitly instruct the model on GIS-specific requirements, such as ensuring map layers use consistent projections, dropping entries with missing coordinates, and using appropriate spatial join methods. We also embed domain rules and metadata (e.g., known coordinate reference systems or common join keys) into either the prompt or a validation layer, so that the model’s output aligns with established GIS procedures. This approach allows us to leverage the general LLM while ensuring its solutions exhibit GIS-specific expertise.

3.2.2. GIS Operation Library

The GIS operations library forms the computational backbone of our system, providing a carefully curated set of geospatial tools and algorithms that enable both fundamental tasks and advanced analysis. The library covers a wide range of operations, from essential procedures such as coordinate projection, spatial joins, and attribute queries, to more sophisticated processes such as buffering, clustering, spatial interpolation, and time trend analysis. All tools are implemented through widely adopted Python libraries, such as GeoPandas and Shapely, ensuring not only high compatibility with heterogeneous geospatial datasets, but also adherence to established standards in the geoinformatics community. The modular nature of the library enables our system to dynamically assemble workflows tailored to specific tasks, which will be demonstrated in case studies in

Section 4.

3.2.3. Execution Engine

The execution engine is responsible for the whole task implementation process. It dynamically converts the solution graphs generated by the LLM into executable Python (version 3) scripts, which are then run to process geospatial data and produce results. The generated python scripts for our tasks are provided in

Appendix B. This module ensures the main communication between the interpreted user query, the GIS operation library, and the data inputs. It handles task-specific requirements, such as data validation, spatial alignment, and error handling. Additionally, the execution engine incorporates iterative debugging mechanisms, allowing it to refine scripts and resolve issues autonomously (explained in the below sections), thereby ensuring the reliability of outputs even for complex tasks. Before any metric operation (e.g., buffers, lengths, and areas), the engine automatically reprojects the relevant layers to an appropriate projected metric CRS for the study area, performs the computation in metres and then reprojects results back to the target display CRS (typically WGS84 or EPSG:4326). This is enforced in the generated code via explicit

to_crs(<metric EPSG>) calls prior to metric calculations.

3.3. Geospatial Data Management

Efficient geospatial data management is crucial to our system’s overall performance. The framework was designed to support diverse GIS datasets, streamline analysis, and ensure compatibility across operations. The system accepts two main types of data as inputs: CSV files, used to contain tabular information on attributes (for example, demographic data, or building heights), and shapefiles, which provide geometric information in the form of points, lines, or polygons. The loading pipeline integrates validation procedures aimed at ensuring the consistency and integrity of the datasets. Specifically, the completeness of tabular attributes and the correctness of spatial geometries are verified, reducing the risk of propagating errors in subsequent analytical phases.

Once validated, the data is transformed to enable full interoperability between different formats and information levels. This process includes spatial joining, reference system alignment (CRS), and field standardization. Particular attention is paid to the correct management of projections—all layers are harmonized in a common CRS for overlay and join operations, while for metric measurements (distances, areas, and lengths), the data is temporarily reprojected into an appropriate projected system (e.g., UTM) and subsequently transferred to the final display CRS. This procedure ensures the accuracy of calculations and the comparability of results, as demonstrated in the Pesaro case study (

Section 4), where building data were integrated with urban structure shapefiles to produce city development maps.

To ensure reliability and accuracy in geospatial analyses, the system applies data cleansing and preprocessing procedures at multiple stages of the workflow. These include handling missing values, validating and correcting geometries, aligning CRSs, verifying join keys and data types, and eliminating duplicate records.

3.4. Task Automation, Workflow Generation, and Output Management

The system automates the execution of GIS workflows and generates task-specific Python scripts, thereby enabling even users with limited technical expertise to perform complex analyses. The user request is translated into an operation graph, which is represented as a directed acyclic graph (DAG) using the NetworkX library. Nodes in this context represent GIS operations or datasets, while edges describe data flows and dependencies between operations. This representation facilitates the generation of modular, reusable scripts that can be adapted for related analyses.

The processed data can be visualised using a variety of techniques, including thematic maps, temporal visualisations, and overlay maps. The ability to customise layouts, colours, labels, and filters allows the user to focus on the most relevant attributes. The ability to export outputs in various formats (images, shapefiles, CSV, and Excel) is fundamental to ensuring compatibility with further processing.

In order to ensure reliability and accuracy, the system integrates error detection and iterative debugging mechanisms. The code generated by the LLM is subject to automatic review, and in the event of execution errors, the system captures exceptions and tracebacks, calls the LLM to suggest corrections, and automatically retries execution until successful completion. Upon completion, the output is validated, thereby verifying the presence of the expected files and reporting any anomalies.

3.5. Graphical User Interface Design and Implementation

The GUI represents a central component of our system, facilitating intuitive interaction with geospatial data and simplifying tasks that would otherwise require extensive GIS expertise. The GUI has been designed for utilisation by both GIS professionals and non-expert users. It integrates natural language input with automated backend processing to facilitate spatial analysis. The interface has been implemented using CustomTkinter, a lightweight Python library that enhances the user experience through a modern, interactive, and easily customisable design (see

Figure 3). The GUI facilitates efficient data selection, task execution, model selection, and result visualisation, thereby ensuring a seamless workflow from query input to output generation.

The selection of columns within the GUI is optional, addressing scenarios where datasets may contain ambiguous or multilingual attribute names. Allowing users to specify relevant columns helps guide the LLM and reduce ambiguity during code generation, while straightforward datasets can bypass this step to streamline operations.

Furthermore, the GUI provides language selection between English and Italian to accommodate datasets with multilingual metadata and attribute names. This feature enhances the system’s reliability and response time, particularly when processing datasets with mixed language content.

In addition to this, the interface offers a range of user-friendly features that enable efficient geospatial analyses without requiring extensive GIS expertise. The key functionalities of the GUI are summarized in

Table 1.

In addition to the main functionalities outlined in

Table 1, the GUI incorporates features to enhance the user experience. Depending on the user’s preference, the framework has the capacity to either call the OpenAI API for GPT-4 or run an instance of DeepSeek-R1-70B. This offers the user the choice of the cutting-edge performance of GPT-4 and the accessibility of an open-source alternative within one integrated system. Throughout the execution, the GUI’s progress indicators inform the user of the current stage, and once the task is completed, the results are presented.

To support these capabilities, the GUI has been constructed using a robust and contemporary technological framework, designed to ensure efficiency, scalability, and a seamless user experience. The key components of the technological framework are listed in

Table 2.

Our system aims to enhance user experience through the GUI and revolutionizes geospatial analysis by offering the following:

- -

A “low-code AI” GIS workflow, reducing reliance on scripting.

- -

Customizable data input settings, supporting multilingual datasets.

- -

Adaptive AI-driven task execution for faster processing.

- -

An aesthetically refined UI with modern themes and responsive components.

3.6. Integration of an Open-Source LLM: DeepSeek-R1-70B

To explore the flexibility and deployment options of our system, we integrated a state-of-the-art open-source LLM into our framework. We selected DeepSeek-R1-70B, a 70-billion-parameter model derived from LLaMA 3.3-70B-Instruct and developed by DeepSeek, a company specializing in open-source AI models. DeepSeek-R1-70B is released under the MIT License [

62,

63], which allows for free use and modification. Notably, this model is designed for advanced reasoning tasks and achieves performance comparable to leading proprietary LLMs. Its adoption aligns with our goal of keeping the GIS automation approach accessible and independent of closed-source services.

The model was deployed locally using Ollama (version 0.5.7), a framework facilitating the installation and execution of LLMs on personal computing hardware. Local deployment provides several practical advantages, including enhanced data privacy, reduced operational costs by eliminating cloud service fees, lower latency due to avoidance of network calls, offline accessibility for secure or remote environments, and the potential for domain-specific customization of the AI behaviour (

Table 3).

The integration of DeepSeek-R1-70B demonstrates that offline, open-source LLMs can serve as a reliable and cost-effective alternative to proprietary models in GIS automation. Empirical evaluations indicate that the system maintains high performance and produces outputs of comparable quality when the backend model is replaced with this open-source LLM. Such flexibility is particularly relevant for organizations requiring on-premises AI solutions or for those preferring to avoid exclusive reliance on commercial models, thereby enhancing reproducibility, accessibility, and operational independence.

All experiments employed GPT-4 via the OpenAI API and DeepSeek-R1-70B through local execution. Geospatial scripts and model inference were run on a Windows workstation with the specifications listed in

Table 4, targeting Python 3.10 with standard geospatial libraries. Comparable hardware was used for QGIS-based experiments to avoid performance bottlenecks. Environment configurations and prompt templates are provided in the project repository to ensure reproducibility.

4. Case Study and Evaluations: Urban Analysis in Pesaro

We demonstrate the effectiveness of our LLM-assisted GIS workflow on real urban data from Pesaro, Italy. A series of typical geospatial analysis tasks—including validating and repairing shapefiles, merging datasets, cartographic visualization, and buffer analysis—were performed to showcase the system’s performance and accuracy. These tasks mirror common workflows in QGIS (v3.36) and were chosen to evaluate whether our automated approach can minimize manual effort, preserve analytical rigour (even with data irregularities like outliers or null values), and improve accessibility through natural language interaction. By integrating building attribute data (e.g., heights, construction years) from CSV files with geographic shapefiles, our system streamlines data-intensive processes into a single automated workflow, making spatial analysis more time-efficient and user-friendly. In addition to this case study, we conducted a focused evaluation of the system’s factual reliability (hallucination tendency) using a set of 30 diverse queries, which is described later in

Section 4.4.

4.1. Dataset Description

The evaluation uses a comprehensive geospatial dataset representing the urban environment of Pesaro. The data encompasses multiple layers, including building footprints (over 21,000 building polygons with attributes such as construction year, height, and footprint area), address points (geocoded street addresses with coordinates linking buildings to locations), administrative boundaries at the neighbourhood and district levels (polygons with official names/codes and area metrics), the road network (with street names, classifications, lengths, and construction/modification dates), and protected monumental areas (heritage zones with area and perimeter attributes). Together, these layers provide a rich spatial context for analysis at various scales. All data covers the entire city and surroundings of Pesaro. For reproducibility, the dataset is available in our project repository. This diverse urban dataset allowed us to test the system on realistic tasks such as linking building records, summarizing by administrative units, and performing distance-based queries.

4.2. Evaluation: Human vs. Machine

To evaluate our system’s performance against traditional GIS workflows, we conducted a comparative study pitting our automated LLM-based system against human experts performing the same tasks manually. We recruited 10 experienced GIS analysts and had each expert independently execute a series of representative spatial analysis tasks in QGIS (version 3.36). They followed their typical procedures for data preparation, analysis, and mapping, and we recorded the time taken for each task, any errors or inconsistencies encountered, and the final outputs (e.g., cleaned datasets and generated maps). The same tasks were then given to our system via natural language prompts. The system automatically generated and ran Python scripts (using libraries like GeoPandas for GIS operations and Matplotlib for visualization) to perform each task on the Pesaro data. Both approaches used the same dataset and task definitions to ensure a fair comparison. By examining the execution times, output accuracy, and user effort required for the manual vs. automated methods, we assess whether the LLM-driven workflow can match or surpass the effectiveness of manual analysis.

4.3. Experimental Design

For the manual workflow, each of the 10 GIS experts performed the tasks using QGIS 3.36, employing standard tools and their personal expertise to address any data issues (such as geometry errors or missing values) and to produce the required maps or analyses. For the automated workflow, our system was used to interpret each task described in plain language and execute it without human intervention beyond providing the query. The outputs from the two approaches were then compared for consistency. We paid particular attention to execution time (how quickly the task was completed, excluding any setup or loading time common to both), accuracy of results (whether the spatial outputs and values matched the ground truth or manual result), and user effort (the level of GIS expertise or manual steps required). The core question was whether the LLM-driven system could achieve the same results as a human GIS analyst, in less time and with less manual effort.

4.4. Core Tasks and Observations

We defined six main tasks spanning data preprocessing, spatial analysis, and map generation, each critical to the overall workflow. These tasks were chosen to represent typical stages in a geospatial analysis process, ensuring a comprehensive evaluation of both manual and automated approaches as shown in

Table 5. Below there is a description of each task, highlighting the approximate time investments required, the specific techniques or tools involved, and the key takeaways from our analysis.

Figure 4.

Comparison of shapefiles and maps of building heights: (a) QGIS shapefile, (b) shapefile generated with our system, (c) map generated with GeoGPT, (d) map generated with DeepSeek-R1.

Figure 4.

Comparison of shapefiles and maps of building heights: (a) QGIS shapefile, (b) shapefile generated with our system, (c) map generated with GeoGPT, (d) map generated with DeepSeek-R1.

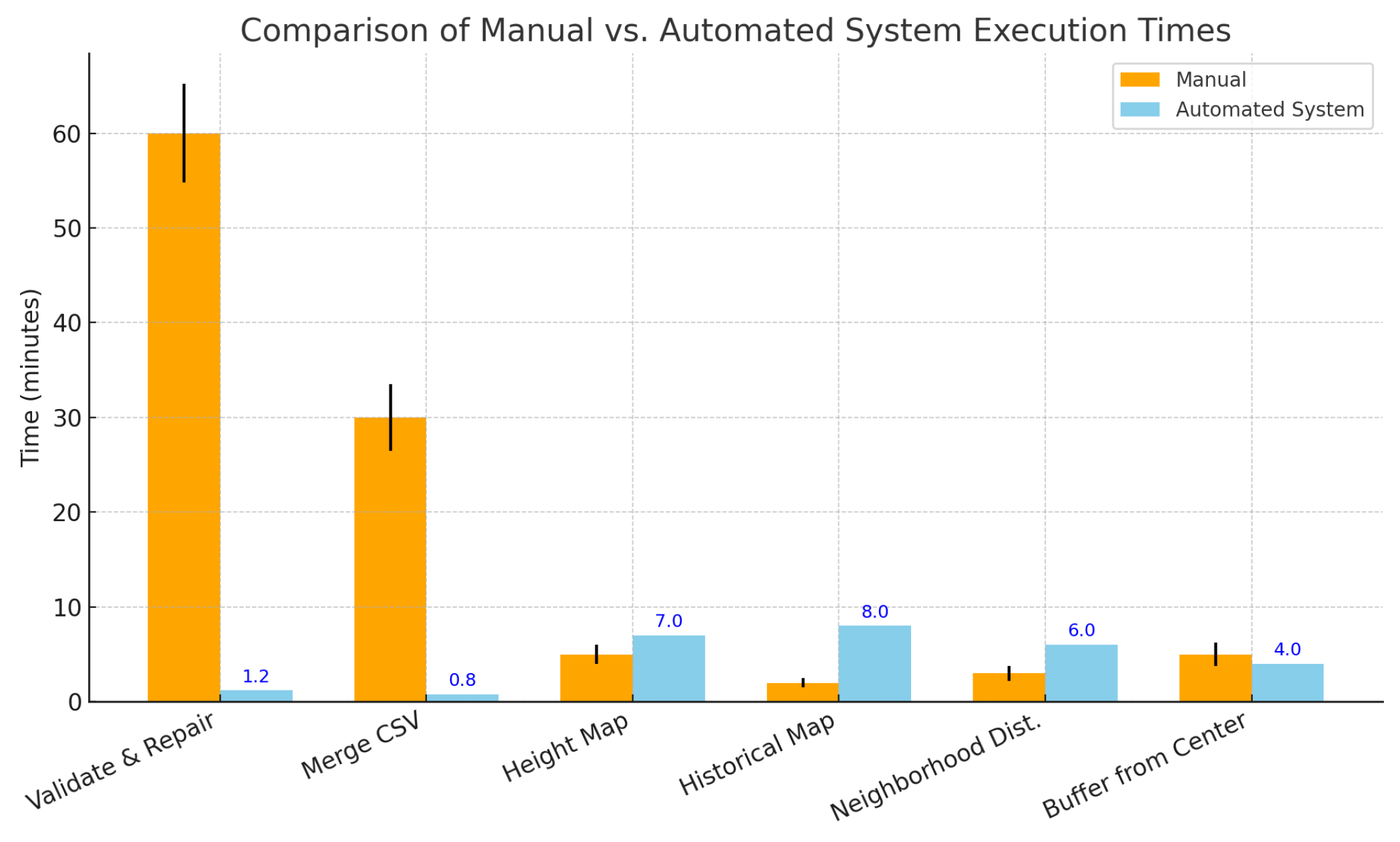

We measured per-task and total completion times across 10 experts, reporting results as mean ± standard deviation (SD) and range. On average, manual execution of all tasks required min (range: 95–115 min; approximately 1 h and 45 min). In contrast, the automated system completed the same set of tasks in just 27.0 min. Across individual tasks, the automated approach consistently reduced time compared to manual processing, often by an order of magnitude. A Mann–WhitneyU test comparing total manual versus automated times confirmed that the difference was highly significant (), demonstrating that the automated workflow substantially accelerates task completion without compromising output quality. All automated timings were measured on a local workstation (Intel i9-14900, 128 GB RAM, 2×RTX 6000 Ada, total 95 GB VRAM; Windows 11 Pro 24H2), while GPT-4 runs used the OpenAI API).

To provide a visual and immediate comparison of the time required to perform each individual task between the GIS experts and our system, we present the histogram shown in

Figure 8. This visualization allows for a clear side-by-side evaluation of the performance, helping to highlight the differences in execution time for each task. By examining the data, one can easily assess the efficiency of our system relative to traditional manual methods.

Figure 5.

Comparison of shapefiles and maps of building construction years: (a) QGIS shapefile, (b) shapefile generated with our system, (c) map generated with our system, and (d) map generated with DeepSeek-R1.

Figure 5.

Comparison of shapefiles and maps of building construction years: (a) QGIS shapefile, (b) shapefile generated with our system, (c) map generated with our system, and (d) map generated with DeepSeek-R1.

Figure 6.

Comparison of shapefiles and maps for buildings in Pesaro’s neighbourhood: (a) shapefile generated with QGIS, (b) shapefile generated with our system, (c) map generated with our system, (d) map generated with DeepSeek-R1 (buildings), and (e) map generated with DeepSeek-R1 (neighbourhood).

Figure 6.

Comparison of shapefiles and maps for buildings in Pesaro’s neighbourhood: (a) shapefile generated with QGIS, (b) shapefile generated with our system, (c) map generated with our system, (d) map generated with DeepSeek-R1 (buildings), and (e) map generated with DeepSeek-R1 (neighbourhood).

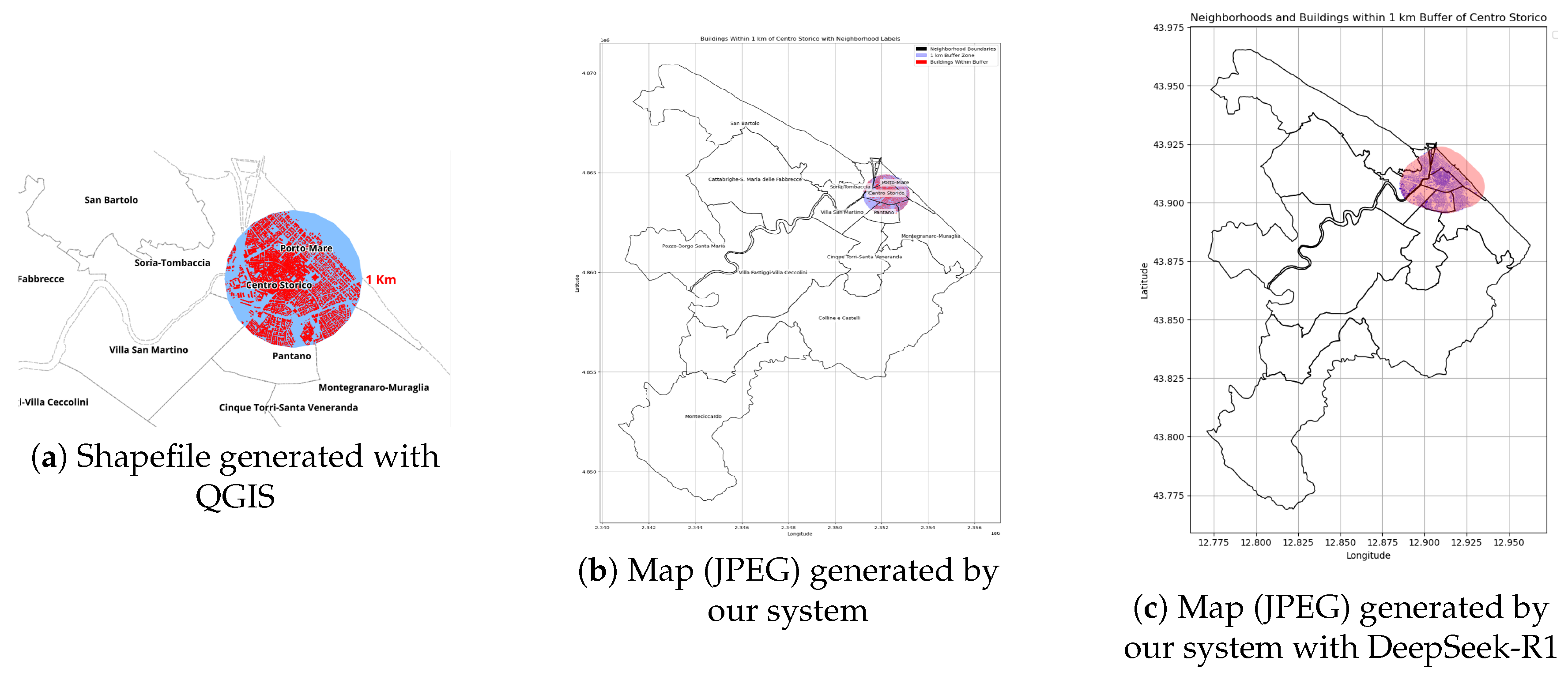

Figure 7.

Comparison of shapefile and maps with a 1 km buffer from the city centre: (a) shapefile generated with QGIS, (b) map generated by our system, and (c) map generated with DeepSeek-R1.

Figure 7.

Comparison of shapefile and maps with a 1 km buffer from the city centre: (a) shapefile generated with QGIS, (b) map generated by our system, and (c) map generated with DeepSeek-R1.

Figure 8.

Time comparison for tasks executed by human experts vs. our system.

Figure 8.

Time comparison for tasks executed by human experts vs. our system.

4.5. Performance and Usability Findings

In evaluating the efficiency and usability of our system versus traditional manual GIS workflows, we assessed key factors such as execution time, error handling, and accessibility. By comparing both approaches in real-world scenarios, we aimed to determine how effectively our system automates complex geospatial tasks while minimizing human effort. Below, we break down our findings across three key dimensions:

- -

Overall Execution Time: Summing all tasks, the manual approach took min (range 95–115; approximately 1 h 45 m) to complete, including data validation, symbology decisions, and iterative error corrections. In contrast, our system finished the combined tasks in significantly less time, thanks to automated script generation and robust error-handling routines.

- -

Error handling and robustness: When we introduced deliberate data errors—such as missing coordinates, incorrect CRSs, or duplicate records—the manual approach required careful inspection in QGIS to diagnose and resolve each issue. Our system, however, was able to detect and correct most of these errors automatically, significantly reducing the need for user intervention.

- -

Ease of use and accessibility: Qualitative feedback from the 10 GIS experts confirmed notable usability benefits of the LLM-driven system. The experts reported that the natural language interface and automation of workflows made the process of performing complex GIS analyses much more accessible. They noted a substantial reduction in tedious manual steps—for instance, repetitive tasks like individually checking for data errors or manually configuring joins and buffers were handled by the system, which they found to be a major convenience. The experts also highlighted that the GUI was intuitive to navigate. After minimal training on how to phrase queries, they could obtain the desired results without writing any code or going through the multi-step processes normally required in GIS software. In terms of perceived accuracy, the experts expressed confidence in the system’s outputs after reviewing them, given that the results closely matched what they would produce manually. A few experts mentioned that the system’s choice of symbology or formatting in maps was different from their personal style, but they acknowledged those are easily adjusted cosmetic details. Importantly, the success of the automated approach in completing the tasks led several experts to believe that even colleagues with less GIS experience could use the system to get meaningful results. This feedback underscores that the integration of GPT-4 and DeepSeek-R1-70B in our GIS workflow not only improves efficiency but also offers a user-friendly experience that lowers the barrier to entry for performing advanced spatial analysis.

4.6. Evaluation: Hallucination

To further assess the reliability of our open-source LLM approach, we conducted a systematic evaluation of DeepSeek-R1 with respect to hallucination, focusing on its factual accuracy when executing a diverse set of GIS queries. For this purpose, we compiled a benchmark of 30 unique geospatial questions derived from the Pesaro dataset, encompassing a different level of complexity, from simple attribute lookups to multi-step reasoning tasks which are listed in-detail in

Table A1 of

Appendix A. Each query was mapped to a known correct outcome, enabling objective accuracy assessment. DeepSeek-R1 was tasked with autonomously planning and executing the necessary GIS operations to answer each query, and its results were evaluated against the ground-truth answers. Overall, the model demonstrated high robustness, producing correct (non-hallucinated) results for 27 out of 30 queries, yielding an accuracy of 90%. Specifically, all simple queries were answered correctly (100% accuracy), while only a single error occurred among moderate queries (90% accuracy), and two errors were observed among the most complex tasks (80% accuracy), as shown in

Table 6. This indicates that hallucinations in DeepSeek-R1 are rare and primarily arise in cases requiring extended chains of spatial operations or multi-stage reasoning. An examination of individual outcomes revealed that errors were limited to three of the most demanding queries, which required the model to coordinate multiple spatial filters or integrate several intermediate computations, circumstances known to challenge current LLM agents. Furthermore, as shown in

Table 7, a breakdown by the number of actions required to solve each query confirms that DeepSeek-R1 achieves perfect accuracy on all single-action and three-action queries, with minor drops for longer reasoning chains involving four or more steps. The full set of queries, including outcome, number of GIS tools invoked, and action sequence, is detailed in

Appendix A. These results demonstrate that DeepSeek-R1, as an open-source alternative, achieves factual reliability on par with leading proprietary models such as GPT-4, and is particularly robust for the majority of practical GIS workflows.

Protocol and scoring: A result was marked

correct if it exactly matched an independently derived ground truth. Numeric answers required exact values; set/list answers required all and only the correct items. Adjudication was performed blinded to the LLM identity. We release the full list of 30 queries, expected answers, system outputs, and action counts in

Appendix A and in machine-readable form in the project repository.

The complete list of queries, the number of GIS tools and actions invoked, and the outcome for each is provided in

Appendix A.

5. Discussion

As geospatial data grows in scale and complexity, the need for more autonomous strategies to manage GIS tasks without the burden of manual scripting emerges. The proposed system addresses this need by combining a domain-aware LLM with a modular set of GIS operations. Key contributions include (1) a prompt-engineering scheme capable of translating natural language instructions into robust GIS workflows, and (2) a CustomTkinter-based interface that reduces the programming burden for both experienced and novice users.

Traditional GIS tools, such as ArcGIS ModelBuilder or QGIS plugins, enable visual scripting but still require a basic understanding of GIS concepts, data formats, and software specifications. Our approach interprets user queries (e.g., “find all buildings with more than 10 stories within 500 m of a highway”) and automatically constructs task sequences, including buffers, spatial joins, and attribute filtering. This reduces the gap between conceptual tasks and geospatial outputs, minimizing repetitive manual interventions.

Accessibility is a key strength. CustomTkinter interfaces simplify the installation of additional software and the learning of specialized scripting languages, integrating data selection, parameter configuration, and visualization in a consistent and intuitive environment. User testing confirms that this solution broadens accessibility to non-expert users, including policymakers, urban planners, and environmental scientists.

The system also leverages rapid engineering techniques to manage the complexities of the geospatial domain. LLMs, while powerful, can encounter difficulties with specialized terminology or ambiguous instructions. The use of contextual hints in prompts (e.g., synonyms and clarifications on attributes vs. geometric components) enables automatic disambiguation, reducing interpretation errors and increasing workflow reliability.

Another contribution involves automatic iterative debugging, which corrects errors such as missing attributes or inconsistencies in coordinate systems. This reduces operational disruptions and manual limitations, a crucial aspect in high-risk applications such as disaster management or urban planning. The combination of domain-aware LLMs and an intuitive interface accelerates complex tasks such as data merging, map generation, and urban buffering, while maintaining high analytical accuracy. Comparable results were observed with both GPT-4 and the open-source DeepSeek-R1-70B model, highlighting the feasibility of non-proprietary solutions and the framework’s flexibility.

The “drag-and-drop” or “click-and-run” approaches represent an important step toward democratizing advanced GIS analysis, allowing non-programmers to access operations that previously required specialized training. While eliminating the need for programming skills, effective use requires a minimum level of spatial literacy, such as an understanding of layers, attributes, and coordinate systems. The modularity of the system structure also allows for the rapid integration of specialized modules for hydrology, epidemiology, or advanced remote sensing. The use of open-source models and advanced templates allows the system’s intelligence to be adapted to regional constraints, organizational requirements, and data specificities, improving accuracy in critical applications such as flood risk assessment or historical land use analysis. This flexibility paves the way for community-driven improvements and greater transparency in geospatial query interpretation, providing viable alternatives for those with privacy, cost, or proprietary service constraints.

Finally, the quantitative evaluation of hallucinations (

Section 4.6) confirms the reliability of DeepSeek-R1 for most GIS queries, with errors limited to the most complex and multi-stage analytical tasks. Comparison with manually written pipelines in GeoPandas or QGIS highlights that, while these may have similar or faster execution times, they require significant specialized effort. Automating authoring via LLM allows for significant end-to-end gains without requiring manual programming.

6. Conclusions, Limitations and Future Directions

The system introduced in this paper represents a promising step forward in simplifying geospatial analysis by combining advanced LLMs with a user-friendly interface. By automating complex workflows and reducing the need for manual scripting, the system allows both novice and expert users to perform sophisticated geospatial analyses with greater ease. The integration of a refined prompt-engineering system ensures that user queries are accurately translated into robust GIS workflows, while the CustomTkinter-based interface reduces technical barriers and improves accessibility. In conclusion, this paper introduces an innovative AI-driven framework designed to transform GISs through the integration of LLMs like GPT-4 and the open-source DeepSeek-R1. The system aims to streamline the processing, analysis, and visualization of geospatial data, making these tasks more accessible and user-friendly for both GIS professionals and those with minimal technical experience. By automating geospatial workflows and translating user queries into executable Python code, the system minimizes human error, boosts productivity, and enables users without programming knowledge to carry out sophisticated GIS analyses. Additionally, the intuitive and the usability of lightweight graphical interface simplifies task configuration, dataset selection, and real-time result visualization. Our system addresses many of the inefficiencies typically seen in traditional GIS workflows by generating adaptable, user-driven workflows, allowing for greater flexibility in managing diverse tasks. It also automates the cleaning, alignment, and integration of data from various sources, ensuring consistency and accuracy in spatial analysis. The potential real-world applications of this system are broad, with significant benefits for fields like urban planning, environmental management, infrastructure development, and disaster response. To assess the system’s effectiveness, as we conducted a series of experiments comparing the performance of the automated system with traditional manual workflows. In these experiments, 10 GIS analysts used QGIS to perform identical tasks, and we measured key aspects such as accuracy, quality, processing time, and user experience. The results demonstrated that our system not only matched the accuracy and quality of manual methods but also outperformed them in speed, efficiency, and accessibility. This success was observed with both GPT-4 and the open-source DeepSeek-R1-70B, underscoring that our approach remains effective even with non-proprietary LLMs—an important factor for flexibility and wider adoption. These findings provide a clear picture of how LLM-driven automation can simplify and enhance geospatial analysis for a broad range of users.

However, there are still many challenges that need to be solved:

- -

Ambiguity in user prompts: Although the enriched prompting architecture mitigates many simple misunderstandings, user queries lacking basic details can still result in suboptimal workflows (e.g., “Show me flood zones” with no specified data on rainfall, topography, or historical flooding). LLM-based clarifications help, but advanced strategies—like knowledge graphs or domain-specific language models—may further reduce confusion [

64].

- -

Scalability and performance: Processing large or complex datasets (e.g., multi-gigabyte nationwide raster mosaics or continuous sensor feeds) can overwhelm the current approach if parallelization is not employed. Techniques like distributed computing or streaming-based microservices would be necessary to handle time-sensitive tasks or handle real-time updates efficiently.

- -

Contextual domain knowledge: The system’s LLM, however advanced, remains a general-purpose language model. Tasks that require deep domain reasoning—such as advanced hydrological modelling or socio-economic corridor analysis—could yield incomplete or incorrect results if the LLM’s knowledge does not encompass specialized frameworks or the user fails to supply relevant detail.

- -

Adoption and integration: Although the CustomTkinter interface lowers barriers, widespread organizational adoption may demand integration with existing enterprise GIS platforms like ArcGIS or QGIS. For some institutions, tight coupling with their standard data catalogues, credential systems, or security protocols is essential, requiring additional technical overhead.

Future work on the system will focus on improving usability, automation, and flexibility. A key priority is enhancing the user interface by introducing a visual workflow editor, similar to ArcGIS ModelBuilder [

65], allowing users to modify analysis steps without coding. Additionally, refining prompt engineering with context-aware questioning and local knowledge graphs will reduce ambiguities and improve GIS workflow accuracy. To address concerns over cost and data security, future iterations may integrate other open-source language models like LLaMA or Gemini, enabling organizations to fine-tune models on local datasets while maintaining data privacy. Another critical advancement is real-time data integration, ensuring the system can handle live updates from IoT sensors, satellite imagery, or traffic data while using parallel computing and caching techniques to optimize performance. Expanding beyond text-based inputs, the system could support OCR for scanned documents, LiDAR and drone data processing, and interactive dashboards, making GIS workflows more versatile. While the system aims to simplify geospatial analysis, introducing an “Advanced editing mode” would allow power users to fine-tune parameters, integrate version control, and facilitate collaborative research. Moreover, the presence of ambiguous joins or misclassifications is indicated by the LLM during the code generation or review process. However, there is not yet an explicit Python module that automatically inspects and flags these issues after script execution. It is evident that logic-based post-processing holds significant value, and it is therefore planned that a dedicated Python validation module will be implemented in future releases of the system. This will enhance the reliability and robustness of the system to a greater extent. Furthermore, given the significant enhancement to evaluation that the incorporation of quantitative metrics would effect, it is intended that they be included in future work. This will be achieved by employing standardised benchmarks and spatial accuracy metrics to more rigorously evaluate model performance across different types of GIS tasks. However, we recognise that a more comprehensive and methodical evaluation is necessary to assess the system’s scalability, robustness and generalisability. This issue will consequently be addressed in forthcoming research through the creation of a structured evaluation framework encompassing multiple datasets, spatial contexts, and task complexities. Finally, we will define a set of benchmark tasks and quantitative metrics (e.g., task completion rate and the accuracy of generated workflows) that will allow us to summarise system performance across different scenarios. Overall, these improvements will enhance the system’s accessibility, efficiency, and adaptability, making GIS workflows more intuitive and effective for both novices and experts.