Using Prospective Methods to Identify Fieldwork Locations Favourable to Understanding Divergences in Health Care Accessibility

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Research Aim

1.2. Prospecting

1.3. Measuring Accessibility

1.4. Combining Spatial and Non-Spatial Measures of Accessibility

1.5. Accessibility Studies in a Sub-Saharan African (SSA) Context

1.6. The Added Value of Our Approach

- (1)

- We examine accessibility for people in a low-income country that must walk long distances to obtain health care. Prior healthcare accessibility research in resource-poor settings has utilized Tobler’s [39] hiking function, as we do, to measure geographic accessibility to health care centres in Mozambique [38] but where all travels are being restricted to main, secondary or tertiary roads. We measure accessibility, represented by walking time, using a sophisticated path analysis involving both horizontal and vertical impedance.

- (2)

- We measure pedestrian travel time using datasets with the currently finest resolution available. While SSA is often considered as a data scarce environment, our study also demonstrates that high resolution elevation data, land use data, and crowdsourced datasets (i.e., use of the OpenStreetMap) that are globally available make sophisticated access analysis possible in countries without a well-developed national spatial data infrastructure.

- (3)

- Although studies on health care and health outcomes in Africa are not that limited as they were almost 20 years ago [40], a weakness in most of them is that they do not take people’s perception of access into account. One exception is [41], who combined physical distance to the nearest immunization centre, with mothers’ perceptions of distance as determinants of child immunization in Nigeria, where the perception of distance turned out to be a more robust determinant than actual distance. This highlights the need to combine people’s perceptions of barriers to health care with more objective measures of accessibility to identify causes for poor access.

- (4)

- While several studies tend to emphasize that barriers to health care are linked to specific socio-economic characteristics of the individuals [42], our departure is that barriers to health care are also linked to individual vulnerability factors such as functional limitations. For a person with relatively good health, having to walk to get health care may not be an obstacle. However, for a person with disabilities, having to walk even a short distance could effectively deter access. Hence, this article considers the interaction between individual and contextual characteristics since individual factors of vulnerability may moderate or mediate the impact of physical barriers on access, and vice versa.

- (5)

- Our study is based on a utilization dataset and measures actual geographical accessibility based on a large sample of individual level data (n = 2221), and thus differs from common approaches that examine potential accessibility using aggregated information [3] or approaches that measure travel distances to the nearest health centre (e.g., [15,35]).

- (6)

- Our approach is that barriers to health access are best investigated using a combination of quantitative and qualitative research methods and that a qualitative fieldwork is needed to uncover the most important barriers to health access. A key contribution with this article is a research design for where such a fieldwork should be carried out.

2. Materials and Methods

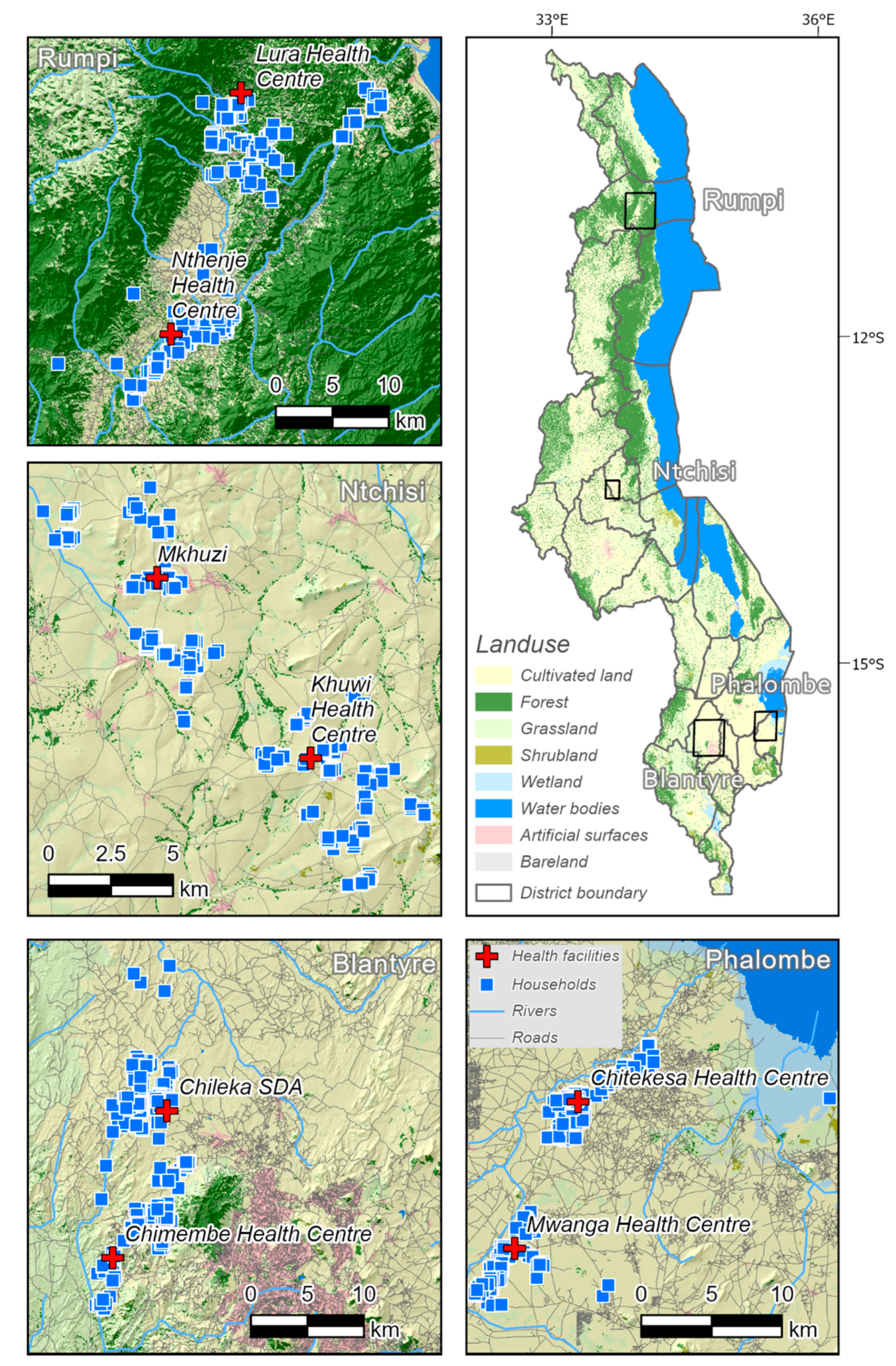

2.1. Health Facilities

2.2. Generating a Composite Variable for Perceived Accessibility

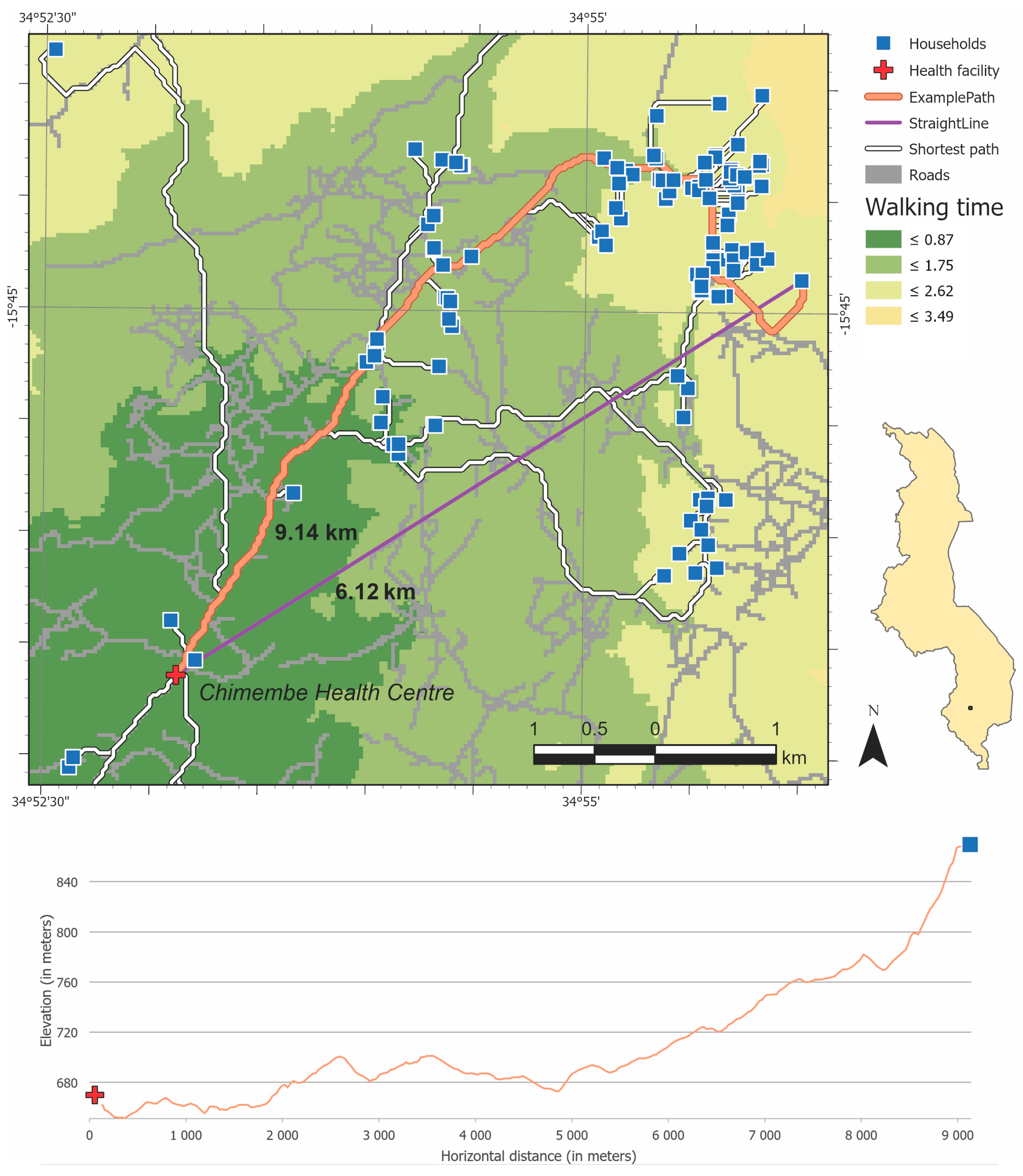

2.3. Generating a Variable for Measured Accessibility (Walking Time)

2.4. Regression and Residual Analysis

2.5. Local Spatial Statistics

3. Results

3.1. Survey Summary

3.2. Path Analysis Results

3.3. Using Local Spatial Statistics to Identify Significant Clusters

4. Discussion

4.1. Interpersonal Relationship

4.2. Prospecting Being Developed as a Spatial Method within Archaeology

4.3. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- CESCR. General Comment No. 14: The Right to the Highest Attainable Standard of Health (Art. 12 of the Covenant); UN Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (CESCR): Geneva, Switzerland, 2000; Available online: https://www.refworld.org/docid/4538838d0.html (accessed on 19 February 2019).

- Akin, J.S.; Guilkey, D.K.; Hazel, E. Quality of services and demand for health care in Nigeria: A multinomial probit estimation. Soc. Sci. Med. 1995, 40, 1527–1537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casas, I.; Delmelle, E.; Delmelle, E.C. Potential versus revealed access to care during a dengue fever outbreak. J. Transport. Health 2017, 4, 18–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akin, J.S.; Hutchinson, P. Health-care Facility Choice and the Phenomenon of Bypassing. Health Policy Plan. 1999, 14, 135–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Stein, M. Your Place or Mine: The Geography of Social Research. In The SAGE Handbook of Fieldwork; Hobbs, D., Wright, R., Eds.; Sage: London, UK, 2006; pp. 59–75. [Google Scholar]

- Räsänen, A.; Lensu, A.M.; Tomppo, E.O.; Kuitunen, M.T. Comparing conservation value maps and mapping methods in a rural landscape in southern Finland. Landsc. Online 2015, 44, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espa, G.; Benedetti, R.; De Meo, A.; Ricci, U.; Espa, S. GIS based models and estimation methods for the probability of archaeological site location. J. Cult. Herit. 2006, 7, 147–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilli, M.; Kuitunen, M.T. Testing the Use of a Land Cover Map for Habitat Ranking in Boreal Forests. Environ. Manag. 2005, 35, 505–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, W.; Wang, F. Measures of Spatial Accessibility to Health Care in a GIS Environment: Synthesis and a Case Study in the Chicago Region. Environ. Plan. Plan. Des. 2003, 30, 865–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Radke, J.; Mu, L. Spatial Decompositions, Modeling and Mapping Service Regions to Predict Access to Social Programs. Geogr. Inf. Sci. 2000, 6, 105–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, W.; Qi, Y. An enhanced two-step floating catchment area (E2SFCA) method for measuring spatial accessibility to primary care physicians. Health Place 2009, 15, 1100–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wan, N.; Zou, B.; Sternberg, T. A three-step floating catchment area method for analyzing spatial access to health services. Int. J. Geogr. Inf. Sci. 2012, 26, 1073–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asare-Akuffo, F.; Twumasi-Boakye, R.; Appiah-Opoku, S.; Sobanjo, J.O. Spatial accessibility to hospital facilities: The case of Kumasi, Ghana. Afr. Geogr. Rev. 2020, 39, 120–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haynes, R.; Jones, A.P.; Sauerzapf, V.; Zhao, H. Validation of travel times to hospital estimated by GIS. Int. J. Health Geogr. 2006, 5, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Aoun, N.; Matsuda, H.; Sekiyama, M. Geographical accessibility to healthcare and malnutrition in Rwanda. Soc. Sci. Med. 2015, 130, 135–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rutherford, M.E.; Mulholland, K.; Hill, P.C. How access to health care relates to under-five mortality in sub-Saharan Africa: Systematic review. Trop. Med. Int. Health 2010, 15, 508–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, D.; Wrigley, H.; Barnett, S.; Roderick, P. Increasing the sophistication of access measurement in a rural healthcare study. Health Place 2002, 8, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Taiar, A.; Clark, A.; Longenecker, J.C.; Whitty, C.J. Physical accessibility and utilization of health services in Yemen. Int. J. Health Geogr. 2010, 9, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Weiss, D.J.; Nelson, A.; Gibson, H.S.; Temperley, W.; Peedell, S.; Lieber, A.; Hancher, M.; Poyart, E.; Belchior, S.; Fullman, N.; et al. A global map of travel time to cities to assess inequalities in accessibility in 2015. Nature 2018, 553, 333–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanser, F.; Gijsbertsen, B.; Herbst, K. Modelling and understanding primary health care accessibility and utilization in rural South Africa: An exploration using a geographical information system. Soc. Sci. Med. 2006, 63, 691–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Páez, A.; Anjum, Z.; Dickson-Anderson, S.E.; Schuster-Wallace, C.J.; Martín Ramos, B.; Higgins, C.D. Comparing distance, time, and metabolic energy cost functions for walking accessibility in infrastructure-poor regions. J. Transport. Geogr. 2020, 82, 102564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, S.R.; Collet, C.; Lugon, R. Least Cost Path Analysis for Predicting Glacial Archaeological Site Potential in Central Europe. In Across Space and Time. Papers from the 41st Conference on Computer Applications and Quantitative Methods in Archaeology Perth; Traviglia, A., Ed.; Amsterdam University Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2017; pp. 261–275. [Google Scholar]

- Higgs, G. A Literature Review of the Use of GIS-Based Measures of Access to Health Care Services. Health Serv. Outcomes Res. Methodol. 2004, 5, 119–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghorbanzadeh, M.; Kim, K.; Ozguven, E.E.; Horner, M.W. A comparative analysis of transportation-based accessibility to mental health services. Transp. Res. Part. Transport. Environ. 2020, 81, 102278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trani, J.-F.; Browne, J.; Kett, M.; Bah, O.; Morlai, T.; Bailey, N.; Groce, N. Access to health care, reproductive health and disability: A large scale survey in Sierra Leone. Soc. Sci. Med. 2011, 73, 1477–1489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Luo, W. Assessing spatial and nonspatial factors for healthcare access: Towards an integrated approach to defining health professional shortage areas. Health Place 2005, 11, 131–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryan, M.; Lin, T.; Xia, J.; Robinson, T. Comparison of perceived and measured accessibility between different age groups and travel modes at Greenwood Station, Perth, Australia. Eur. J. Transport. Infrastruct. Res. 2016, 16, 406–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawthorne, T.L.; Kwan, M.-P. Using GIS and perceived distance to understand the unequal geographies of healthcare in lower-income urban neighbourhoods. Geogr. J. 2012, 178, 18–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comber, A.J.; Brunsdon, C.; Radburn, R. A spatial analysis of variations in health access: Linking geography, socio-economic status and access perceptions. Int. J. Health Geogr. 2011, 10, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Noor, A.M.; Zurovac, D.; Hay, S.I.; Ochola, S.A.; Snow, R.W. Defining equity in physical access to clinical services using geographical information systems as part of malaria planning and monitoring in Kenya. Trop. Med. Int. Health 2003, 8, 917–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tanser, F.; Wilkinson, D. Spatial implications of the tuberculosis DOTS strategy in rural South Africa: A novel application of geographical information system and global positioning system technologies. Trop. Med. Int. Health 1999, 4, 634–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tanser, F.; LeSueur, D.; Solarsh, G.; Wilkinson, D. HIV heterogeneity and proximity of homestead to roads in rural South Africa: An exploration using a geographical information system. Trop. Med. Int. Health 2000, 5, 40–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Scott, D.; Curtis, B.; Twumasi, F.O. Towards the creation of a health information system for cancer in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Health Place 2002, 8, 237–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stock, R. Distance and the utilization of health facilities in rural Nigeria. Soc. Sci. Med. 1983, 17, 563–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huerta Munoz, U.; Källestål, C. Geographical accessibility and spatial coverage modeling of the primary health care network in the Western Province of Rwanda. Int. J. Health Geogr. 2012, 11, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Blanford, J.I.; Kumar, S.; Luo, W.; MacEachren, A.M. It’s a long, long walk: Accessibility to hospitals, maternity and integrated health centers in Niger. Int. J. Health Geogr. 2012, 11, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vale, D.S.; Saraiva, M.; Pereira, M. Active accessibility: A review of operational measures of walking and cycling accessibility. J. Transport. Land Use 2016, 9, 209–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- dos Anjos Luis, A.; Cabral, P. Geographic accessibility to primary healthcare centers in Mozambique. Int. J. Equity Health 2016, 15, 173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tobler, W.R. Three Presentations on Geographical Analysis and Modeling: Non-isotropic Geographic Modeling, Speculations on the Geometry of Geography and, Global Spatial Analysis; National Center for Geographic Information and Analysis, UC Santa Barbara: Santa Barbara, CA, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Tanser, F.C.; le Sueur, D. The application of geographical information systems to important public health problems in Africa. Int. J. Health Geogr. 2002, 1, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monguno, A.K. Socio Cultural and Geographical Determinants of Child Immunisation in Borno State, Nigeria. J. Public Health Afr. 2013, 4, e10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wilson, K.; Rosenberg, M.W. Accessibility and the Canadian health care system: Squaring perceptions and realities. Health Policy 2004, 67, 137–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maina, J.; Ouma, P.O.; Macharia, P.M.; Alegana, V.A.; Mitto, B.; Fall, I.S.; Noor, A.M.; Snow, R.W.; Okiro, E.A. A spatial database of health facilities managed by the public health sector in sub Saharan Africa. Sci. Data 2019, 6, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Eide, A.H.; Mannan, H.; Khogali, M.; van Rooy, G.; Swartz, L.; Munthali, A.; Hem, K.-G.; MacLachlan, M.; Dyrstad, K. Perceived Barriers for Accessing Health Services among Individuals with Disability in Four African Countries. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0125915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Penchansky, R.; Thomas, J.W. The Concept of Access: Definition and Relationship to Consumer Satisfaction. Med. Care 1981, 19, 127–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.; Chen, J.; Liao, A.; Cao, X.; Chen, L.; Chen, X.; He, C.; Han, G.; Peng, S.; Lu, M.; et al. Global land cover mapping at 30m resolution: A POK-based operational approach. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote. Sens. 2015, 103, 7–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Macharia, P.M.; Odera, P.A.; Snow, R.W.; Noor, A.M. Spatial models for the rational allocation of routinely distributed bed nets to public health facilities in Western Kenya. Malar. J. 2017, 16, 367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Alegana, V.A.; Wright, J.A.; Pentrina, U.; Noor, A.M.; Snow, R.W.; Atkinson, P.M. Spatial modelling of healthcare utilisation for treatment of fever in Namibia. Int. J. Health Geogr. 2012, 11, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tadono, T.; Ishida, H.; Oda, F.; Naito, S.; Minakawa, K.; Iwamoto, H. Precise Global DEM Generation by ALOS PRISM. ISPRS Ann. Photogramm. Remote. Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2014, II-4, 71–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tripcevich, N. ANTHRO 128M Geospatial Archaeology-11.2 Cost Distance. Available online: https://bcourses.berkeley.edu/courses/1289761/pages/in-class-exercise-11-dot-2-cost-distance (accessed on 22 October 2017).

- Irmischer, I.J.; Clarke, K.C. Measuring and modeling the speed of human navigation. Cartogr. Geogr. Inf. Sci. 2018, 45, 177–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ESRI Path Distance. Available online: http://desktop.arcgis.com/en/arcmap/latest/tools/spatial-analyst-toolbox/path-distance.htm (accessed on 2 November 2019).

- WG Washington Group on Disability Statistics. Available online: http://www.washingtongroup-disability.com/ (accessed on 30 June 2020).

- WHO. International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Madans, J.H.; Loeb, M.E.; Altman, B.M. Measuring disability and monitoring the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities: The work of the Washington Group on Disability Statistics. BMC Public Health 2011, 11, S4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Getis, A.; Ord, J.K. The Analysis of Spatial Association by Use of Distance Statistics. Geogr. Anal. 1992, 24, 189–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ESRI How Hot Spot Analysis (Getis-Ord Gi*) Works. Available online: https://desktop.arcgis.com/en/arcmap/10.7/tools/spatial-statistics-toolbox/h-how-hot-spot-analysis-getis-ord-gi-spatial-stati.htm (accessed on 13 April 2020).

- ESRI What Is a z-Score? What Is a p-Value? Available online: https://desktop.arcgis.com/en/arcmap/latest/tools/spatial-statistics-toolbox/what-is-a-z-score-what-is-a-p-value.htm (accessed on 16 December 2019).

- Konijn, E.E. The Lived Experiences of Female Heads in Malawi. An. Exploration of their Health Care Accessibility by Making Use of a Triangulated Access Model; NTNU: Trondheim, Norway, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Halvorsen, T.; Munthali, A.; Braathen, S.H.; Rød, J.K.; Eide, A.H. Using locational data in a novel mixed-methods sequence design: Identifying critical health care barriers for people with disabilities in Malawi. Soc. Sci. Med. 2021, 283, 114127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haggett, P. Locational Analysis in Human Geography; Edward Arnold: London, UK, 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Portugali, J. Location theory in geography and archaeology. Geogr. Res. Forum 1984, 7, 43–60. [Google Scholar]

| Considering Your Own Experience, Tell Me Whether the Following Make It Difficult for You to Get Health Care: | |

|---|---|

| 1 | Lack of transport from home to health facility |

| 2 | No services available |

| 3 | Physical access to facility |

| 4 | Due to faith/belief |

| 5 | Negative attitudes among health workers |

| 6 | There is no accommodation at the health facility |

| 7 | Communication with health workers |

| 8 | Standard of the health facility |

| 9 | The journey to the health care is dangerous |

| 10 | You did not know where to go |

| 11 | Could not afford the cost of the visit |

| 12 | Do not have the necessary document (health card/passport) |

| 13 | You thought you were not sick enough |

| 14 | You tried but were denied health care |

| 15 | The health care provider’s drugs or equipment were inadequate |

| 16 | Could not take time off work or had other commitments |

| 17 | You were previously treated badly |

| 18 | Could not afford the cost of transport |

| 1 | Do you have difficulty seeing, even if wearing glasses? |

| 2 | Do you have difficulty hearing, even if using a hearing aid? |

| 3 | Do you have difficulty walking or climbing steps? |

| 4 | Do you have difficulty remembering or concentrating? |

| 5 | Do you have difficulty with self-care such as washing all over or dressing? |

| 6 | Using your usual (customary) language, do you have difficulty communicating, for example, understanding or being understood? |

| 7 | Do you have a problem with nervousness, sadness or depression? |

| 8 | Do you have a problem performing tasks that are expected of people your age? |

| Gi_Bin Values | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Catchment | Region | N | −3 | −2 | −1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| Chileka | Blantyre | 284 | 3 (1.1) | 6 (2.1) | 4 (1.4) | 265 (93.3) | 0 (0) | 2 (0.7) | 4 (1.4) |

| Chimembe | Blantyre | 305 | 0 (0) | 22 (7.2) | 11 (3.6) | 180 (59.0) | 79 (25.9) | 13 (4.3) | 0 (0) |

| Chitekesa | Phalombe | 231 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 231 (100) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Khuwi | Phalombe | 302 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 275 (91.0) | 18 (6.0) | 9 (3.0) | 0 (0) |

| Lura | Rumphi | 321 | 0 (0) | 23 (7.2) | 0 (0) | 298 (92.8) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Mkhuzi | Ntchisi | 299 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 2 (0.7) | 277 (92.6) | 3 (1.0) | 17 (5.7) | 0 (0) |

| Mwanga | Phalombe | 188 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 188 (100) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Nthenje | Rumphi | 279 | 0 (0) | 32 (11.5) | 13 (4.7) | 206 (73.8) | 3 (1.1) | 25 (9.0) | 0 (0) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rød, J.K.; Eide, A.H.; Halvorsen, T.; Munthali, A. Using Prospective Methods to Identify Fieldwork Locations Favourable to Understanding Divergences in Health Care Accessibility. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2021, 10, 506. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijgi10080506

Rød JK, Eide AH, Halvorsen T, Munthali A. Using Prospective Methods to Identify Fieldwork Locations Favourable to Understanding Divergences in Health Care Accessibility. ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information. 2021; 10(8):506. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijgi10080506

Chicago/Turabian StyleRød, Jan Ketil, Arne H. Eide, Thomas Halvorsen, and Alister Munthali. 2021. "Using Prospective Methods to Identify Fieldwork Locations Favourable to Understanding Divergences in Health Care Accessibility" ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information 10, no. 8: 506. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijgi10080506

APA StyleRød, J. K., Eide, A. H., Halvorsen, T., & Munthali, A. (2021). Using Prospective Methods to Identify Fieldwork Locations Favourable to Understanding Divergences in Health Care Accessibility. ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information, 10(8), 506. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijgi10080506