1. Introduction

Current advances in parallel robots are driven by the development of complex robotic systems that integrate the advantages of different types of mechanisms. These advantages include an extended workspace [

1], unlimited rotational capabilities about specific axes [

2], a remote center of motion (RCM) [

3], and high load-bearing capacity [

4].

Scholars have proposed and studied various parallel mechanisms with different numbers of degrees of freedom (DOFs) that have these and other properties [

5]. In practice, it is often not necessary to have six DOFs for the desired operation. For instance, many tasks, such as machining, require only three translational and two rotational DOFs (a 3T2R motion type) [

6], while ankle rehabilitation typically uses 3-DOF spherical motion [

7].

Parallel mechanisms with four DOFs and a 3R1T motion type are often used in applications where it is necessary to insert a tool rotating about a fixed center of rotation (a pivot point) or displace this center [

8]. Therefore, the 3R motion in these mechanisms usually means a spherical motion about this pivot point, although non-spherical 3R1T mechanisms also exist [

9,

10]. The pivot point may be either fixed or moving; thus, 3R1T mechanisms can be classified into two groups based on this condition. Mechanisms of the first group, with a fixed pivot point, are also known as SP-equivalent mechanisms or RCM mechanisms [

11,

12,

13,

14], whose typical application is minimally invasive surgery.

In the second and less diverse group of mechanisms, the pivot point translates along a specific axis. This motion can be achieved in various ways. For example, a parallel mechanism in [

15] included a passive constraining PS kinematic chain, which provided the desired motion type, complemented by four actuated U

PS chains (P, U, and S indicate prismatic, universal, and spherical joints, respectively; the underline indicates the actuated joint). A similar design was used in [

16], where the mechanism included one actuated

PS and three actuated U

PS chains. There are also mechanisms without PS chains, such as a 4-

RRCR mechanism [

17] and parallel mechanisms with an articulated moving platform [

18] (R and C indicate revolute and cylindrical joints, respectively).

One major issue of parallel mechanisms, including the 3R1T mechanisms discussed above, is their limited workspace, i.e., limited displacements and rotations of their output link. Introducing a circular rail helps to resolve this issue by providing unlimited rotation about the rail axis [

2]. Several studies have analyzed parallel mechanisms with a circular rail, confirming their increased workspace. For example, in [

19], the authors used a geometrical approach to determine the workspace of a 3-

RRP planar mechanism. A geometrical approach was also applied to a 3-

RR

PS spatial mechanism [

20]. Iterative methods were used to analyze the workspaces of 3-

RRRS and 3-

RRSR mechanisms in [

21], and for the Eclipse robot with a 3-

RPRS architecture in [

22]. In [

23], the authors analyzed the workspace of a 6-

RUS mechanism by studying its kinematic equations and geometry. This approach was similarly used in [

24] to construct the maximal workspace of a 3-

RRR spherical mechanism, while paper [

25] analyzed the workspace of a 3-

RRS spherical mechanism using an iterative approach. In [

26], the same approach was applied to a 3-

RPSR mechanism. Finally, the authors of [

27] used computer-aided design (CAD) tools to construct the workspace of a 3-

RR

RS foldable mechanism.

In the studies mentioned above, joint constraints were the primary factors limiting the workspace. However, other factors also influence its shape and size. Notably, link interference is a significant problem, as examined in [

28,

29]. This factor was also included in the workspace analysis of the Eclipse [

30,

31] and Eclipse II [

32,

33] mechanisms.

Singularities represent another major issue that limits the workspace of parallel mechanisms and degrades their performance. In a singular configuration, the mechanism may lose or gain DOFs or even change its motion type [

5]. Therefore, it is essential to analyze singularities when evaluating the workspace. In [

34], the authors performed such an analysis for a 6-

RUS mechanism with a circular rail. A similar method was used to calculate the workspace of a mechanism with two circular rails [

35]. Furthermore, singularity-free workspaces were analyzed for 3-DOF spherical mechanisms in [

36,

37], and for a 6-DOF spatial mechanism in [

38].

The literature review reveals a diversity of parallel mechanisms with a circular rail and studies devoted to their workspace and singularity analysis. Most existing mechanisms, however, have either three or six DOFs. To our knowledge, there were no 4-DOF parallel mechanisms with a circular rail and a 3R1T motion type until paper [

39], where we proposed a family of such mechanisms for the first time. That paper and subsequent works [

40,

41,

42] focused on the mobility, position, and kinetostatic analysis of these mechanisms, while their workspace and singularity issues remain unaddressed.

This article continues our previous research and contributes to the further development of 3R1T mechanisms with a circular rail and a movable pivot point. It focuses on a specific mechanism with a 1-SPS/3-RRRRR architecture, performing a detailed workspace and singularity analysis. The major contributions of this paper are as follows:

The reachable rotation angles of the mechanism, including the full-twist workspace of its output link, are computed using an iterative method. The analysis is performed for various positions of the pivot point, both with and without joint constraints.

Singular configurations of the mechanism and its singularity-free regions of rotations are determined using screw theory techniques. The results are compared with other similar mechanisms and show that the full-twist singularity-free workspace is independent of the pivot point position.

The rest of the paper has the following organization.

Section 2 discusses the design of the 4-DOF 3R1T parallel mechanism.

Section 3 is dedicated to the inverse kinematics of the mechanism.

Section 4 presents a workspace analysis with and without considering joint constraints.

Section 5 focuses on a singularity analysis.

Section 6 discusses the results of the workspace and singularity analysis and compares them with other similar mechanisms.

Section 7 concludes the paper and mentions directions for future work.

2. Mechanism Description

In previous work [

43], we proposed a 3-DOF spherical parallel mechanism with a circular rail, which was subsequently extended to a family of 4-DOF 3R1T mechanisms [

39]. These mechanisms may have kinematic decoupling between the spherical (3R) and translational (1T) motions. They can also operate as reconfigurable spherical mechanisms because of the kinematic chain with a

PS or S

PS architecture, which controls the position of the pivot point. In this article, we consider the mechanism with an S

PS kinematic chain and extend its prior geometric modeling [

41] by introducing iterative workspace construction and screw-theory-based singularity analysis.

Figure 1 shows two CAD models of the mechanism. The design features the S

PS central kinematic chain and three identical

RRRRR side kinematic chains that connect platform 6 (output link) to base 1. Each side chain consists of carriage 2, levers 3 and 4 forming a planar RRR dyad, and small coupler 5. Base 1 incorporates circular rail 1′ and external ring gear 1″. Each carriage contains spur gear 2′, which engages with ring gear 1″, and rollers 2″, which clamp the carriage to rail 1′ from both sides. Platform 6 has shaft 6′ that rests on the spherical joint of the central kinematic chain, which includes piston 7 and cylinder 8. Both mechanisms are driven by four actuators: three drives

D1 coupled with gears 2′, and a fourth drive

D2 located at the prismatic joint between the piston and cylinder.

In both mechanisms shown in

Figure 1, the axes of the platform revolute joints intersect at a common point

, which always lies on the axis of the circular rail. This point serves as the center of spherical motion (the pivot point) and can be located either above (

Figure 1a) or below (

Figure 1b) the platform [

40]. The first variant requires simultaneous operation of all four drives to maintain a fixed pivot point, while the second achieves kinematic decoupling between the 3R and 1T motions. Another key design feature of these mechanisms is the circular rail, which provides the platform with an unlimited rotation around the rail axis.

This paper focuses on the mechanism design shown in

Figure 1a, as it appears more suitable for real-world applications. For example, in rehabilitation medicine, the pivot point should be positioned above the platform and aligned with the center of the ankle joint, thereby providing a patient’s foot with three rotational DOFs [

44]. Subsequent sections address the inverse kinematics, workspace, and singularity analysis for this specific configuration.

3. Inverse Kinematics

The workspace analysis relies on solving the inverse kinematic problem, i.e., finding active joint coordinates for a given set of the moving platform coordinates. For both mechanisms, the orientation of the moving platform can be described by rotation matrix

, which in turn depends on three independent parameters (for example, the Euler angles). Assuming that pivot point

lies on the

axis of stationary reference frame

(

Figure 2a), vertical position of the platform can be described by single coordinate

. For the discussed mechanism, there are four active joint coordinates: three angles

, which describe the position of the carriages on the circular rail, and length

of the central chain. For the sake of clarity, only

is shown in

Figure 2a.

Let

be the vector containing coordinates

,

, and

of point

in moving reference frame

attached to the moving platform:

. Coordinates

of the same point in

can be found as follows:

where

is the vector containing the coordinates of point

in the

reference frame.

Since by the design all joints of any

-th chain always remain in the same vertical plane (

Figure 2b), we can find angles

using the atan2 function:

The rest of the inverse kinematics is straightforward. First, from the design of the moving platform, we know vector

containing the coordinates of point

in

. Coordinates

of the same point in

can be computed as follows:

Since vector

containing the coordinates of point

in

is known by the mechanism design, length

of the central chain can be calculated using the Euclidean norm:

Using Equations (2) and (4), we can solve the inverse kinematics of the mechanism; that is, we can calculate the active joint coordinates. To fully describe the mechanism spatial configuration, we also need to find the coordinates of points

. We start by calculating distance

between points

and

:

where

, with

being the radius of the circular rail and

being the height of points

above the

plane.

Next, we compute angle

using the law of cosines for triangle

(

Figure 2c):

where

and

are the lengths of links

and

.

Let

be the unit vector parallel to line

:

Now, we can compute vector

, which contains the coordinates of point

, by rotating vector

around the axis of joint

by angle

:

where

is the matrix that describes the rotation mentioned above. Assuming that the rotation around the axis of joint

is counterclockwise, the “plus” sign in Equation (8) indicates that the corresponding chain “folds” towards the center of the circular rail, while the “minus” sign corresponds to the chain folding away from the center of the rail. In this work, we focus on the latter case, as it prevents interference between the side chains and the central chain. Matrix

can be derived using the Rodrigues formula:

where

is the 3 × 3 identity matrix;

is the skew-symmetric matrix representation of unit vector

parallel to the axis of joint

:

By observing the geometry of the mechanism, we can deduce this vector:

Thus, equations derived in this section fully describe the spatial configuration of the mechanism, including its intermediate links, for a given orientation and height of the moving platform, specified by rotation matrix and parameter .

4. Workspace Analysis

After solving the inverse kinematics, we can analyze the workspace of the mechanism. Its geometrical parameters match the CAD model presented in

Section 2 and have the following values (in millimeters):

Link dimensions: ; ; .

Coordinates of points: ; , , ; , , ; , , ; ; , .

4.1. Representation of the Platform Orientation

By specifying

,

, and

for all three side chains, we implicitly define the initial orientation of the moving platform, for which the rotation matrix is the 3 × 3 identity matrix, i.e.,

. For the numerical values listed above, the moving platform is horizontal in the initial orientation. In addition, let

be a unit vector indicating the initial direction for the tilt axis of the moving platform. This vector can be chosen arbitrarily, and we select

for convenience. We can now define a different direction for the platform tilt axis using its initial direction

and azimuthal angle

:

where

is a unit vector representing the direction of the tilt axis;

is the matrix of a counterclockwise rotation around the

axis by angle

(

Figure 3). In our case:

Although the circular rail provides unlimited rotation around the axis, the kinematic performance of the moving platform may vary depending on the tilt axis direction. Therefore, it is crucial to analyze multiple directions of this axis rather than focusing on a single direction corresponding to .

Now, we can define tilt angle

of the platform, which is the angle of its rotation around the tilt axis. Additionally, we define twist angle

, describing the rotation of the moving platform around its axis of symmetry. The direction of this axis can be represented by unit vector

:

where

is the rotation matrix around the tilt axis by angle

;

is a unit vector corresponding to the direction of vector

in the initial orientation of the platform. In our case,

. Rotation matrix

can be calculated using the Rodrigues formula with a skew-symmetric matrix representation

of vector

:

Finally, by using the skew-symmetric matrix representation

of vector

, we can apply the Rodrigues formula to obtain matrix

, which describes the rotation of the moving platform around the axis defined by vector

:

Now, we can express the orientation of the moving platform in terms of two consecutive rotations: a tilt by angle

around the axis defined by vector

followed by a twist by angle

around the axis defined by vector

. Therefore, rotation matrix

can be defined as follows:

After defining angles , , and and establishing their relationship with rotation matrix , we can use an iterative process to analyze the mechanism workspace.

4.2. Iterative Workspace Analysis

We begin by selecting the limits and iteration steps for azimuthal angle and tilt angle . In this study, varies from −180° to 180°, and varies from 0° to 180°, both with a step size of 1°. For each combination of these angles, we set and attempt to solve the inverse kinematics. If no real-number solution exists, the corresponding orientation of the moving platform is infeasible. If a solution exists, we increment from 0 in steps of 20° until the solution becomes complex. We then reduce the step size to 10° and repeat the process, starting from the last value that yielded a real solution. This procedure is repeated with progressively smaller step sizes of 5°, 2°, and 1°, matching the discretization step for and . By completing this sequence for both counterclockwise (positive) and clockwise (negative) twists of the moving platform, we determine limit values and of angle , where the sign in the superscript indicates the direction of the platform twist.

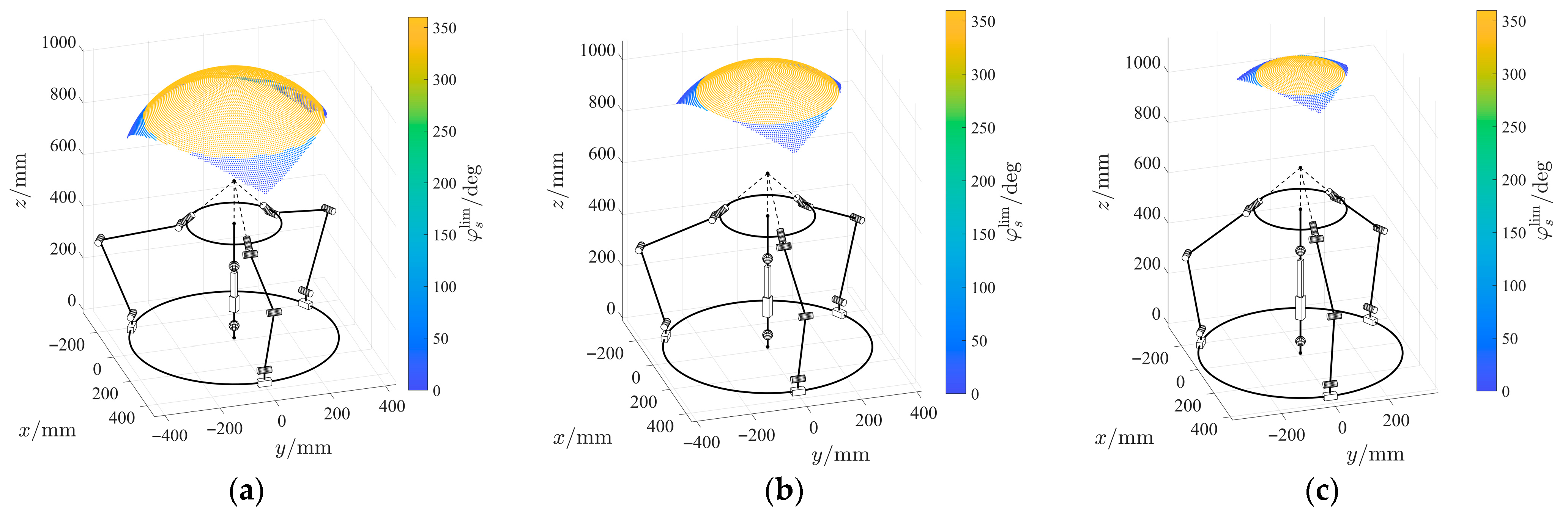

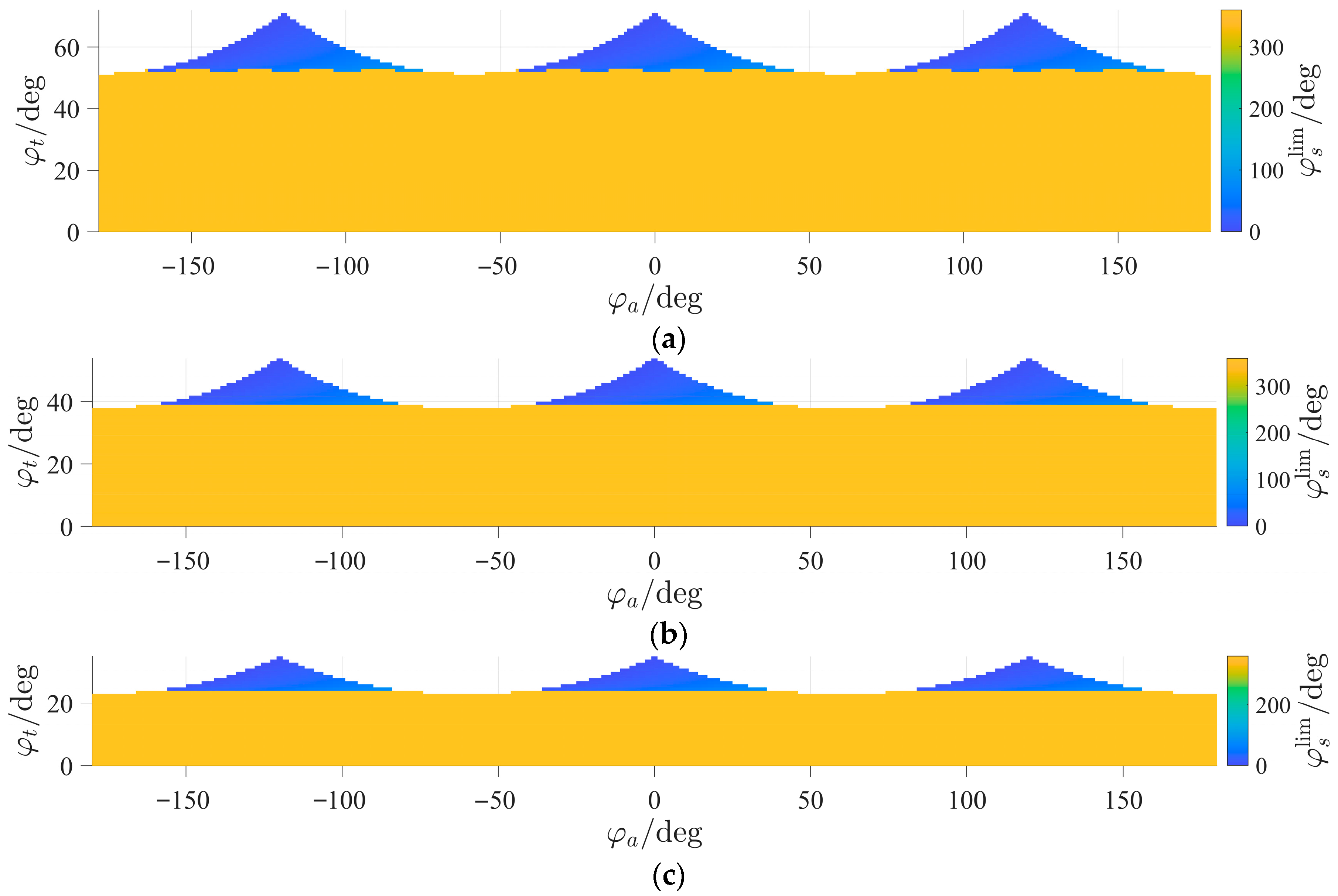

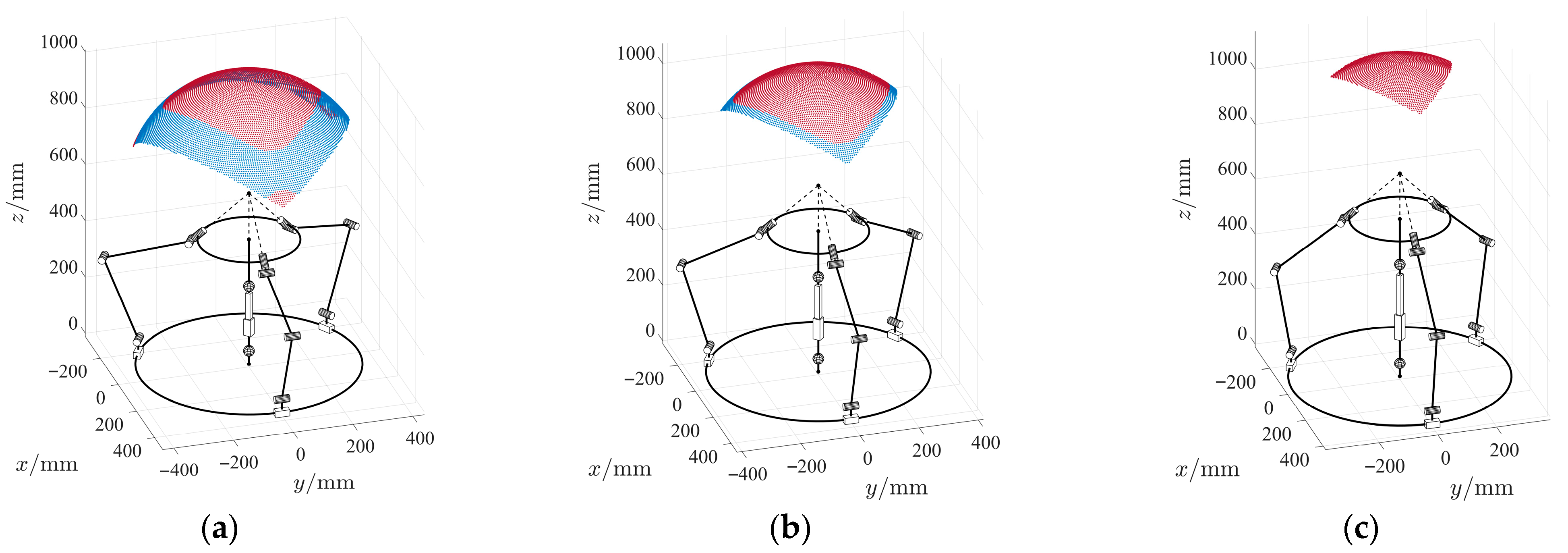

Using MATLAB software (version R2023a), we performed the analysis according to the algorithm described above for three different values of

: 607 mm, 672 mm, and 737 mm. The results were visualized on a spherical surface with a radius of 400 mm (

Figure 4) and as a 2D map of this surface in

–

coordinates (

Figure 5). In all cases, the values of

and

were identical and denoted as

, visualized using a color scale. All calculations were performed on a laptop equipped with an Intel i7-12650H (2.70 GHz) CPU and 16 GB of RAM, taking an average of 30 s to complete.

A total of 65,341 combinations of and were examined. The number of feasible combinations was 21,229 for mm, 15,849 for mm, and 10,008 for mm. In all cases, there is a region of the workspace where, for any feasible orientation of the moving platform, its rotation around the axis defined by is unrestricted. This region is bounded by values of 51° for mm, 38° for mm, and 23° for mm. The maximum feasible tilt angles were 71°, 54°, and 35° for the respective values of mentioned above.

4.3. Workspace Analysis Considering Joint Constraints

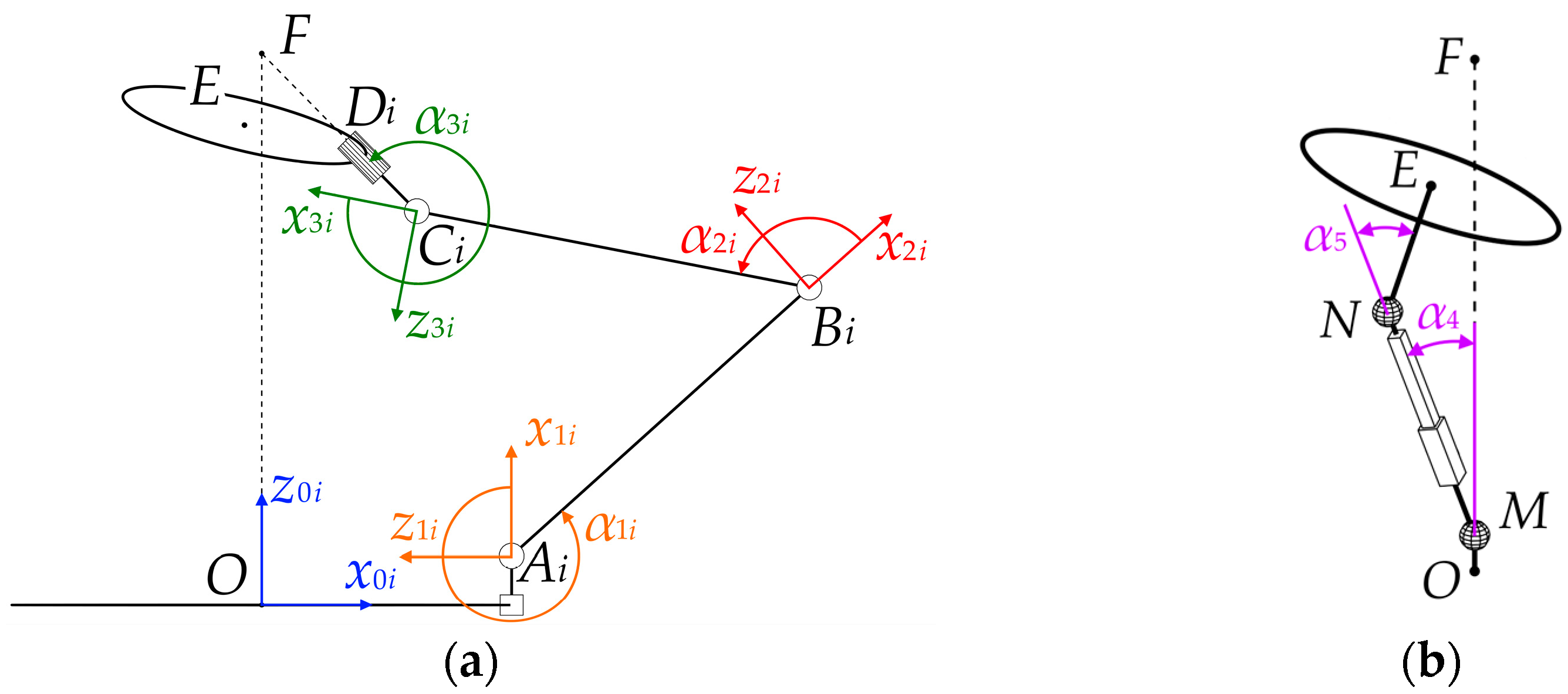

The previous analysis does not account for possible joint constraints. To study these constraints, we should first establish an algorithm for determining the angles between neighboring links of the mechanism (

Figure 6).

We begin by analyzing one of the side kinematic chains. A two-dimensional planar reference frame can be associated with each link, as shown in

Figure 6a. For the

-th chain, the coordinates of a point in the

reference frame can be transformed into the

reference frame using the following rotation matrix:

Since the

coordinate is not relevant in this case, we can define the two-dimensional vectors of points

,

,

, and

in the

reference frame as follows:

We can find vectors

,

, and

, which contain the coordinates of points

,

, and

in the

reference frame as follows:

where

Using the components of vector

, we can calculate angle

by the atan2 function:

Next, we use this angle to find vectors

and

, which contain the coordinates of points

and

in the

reference frame:

where

Angle

can then be found using the components of vector

and the atan2 function:

Lastly, we follow the same approach to calculate vector

, which contains the coordinates of point

in the

reference frame:

and, after that, we compute angle

:

For the central chain, we should determine tilt angles

and

in the spherical joints (

Figure 6b). We calculate these angles using the law of cosines for triangle

:

where

,

, and

are the distances between the corresponding points.

The CAD model of the mechanism provides us with the design constraints for the joint angles computed above (in degrees): , , , , . These values match the ranges of the atan2 and acos functions in MATLAB, which are equal to [–π, π] and [0, π] rad, respectively. In addition, we select the feasible range for length to be [230, 360] mm.

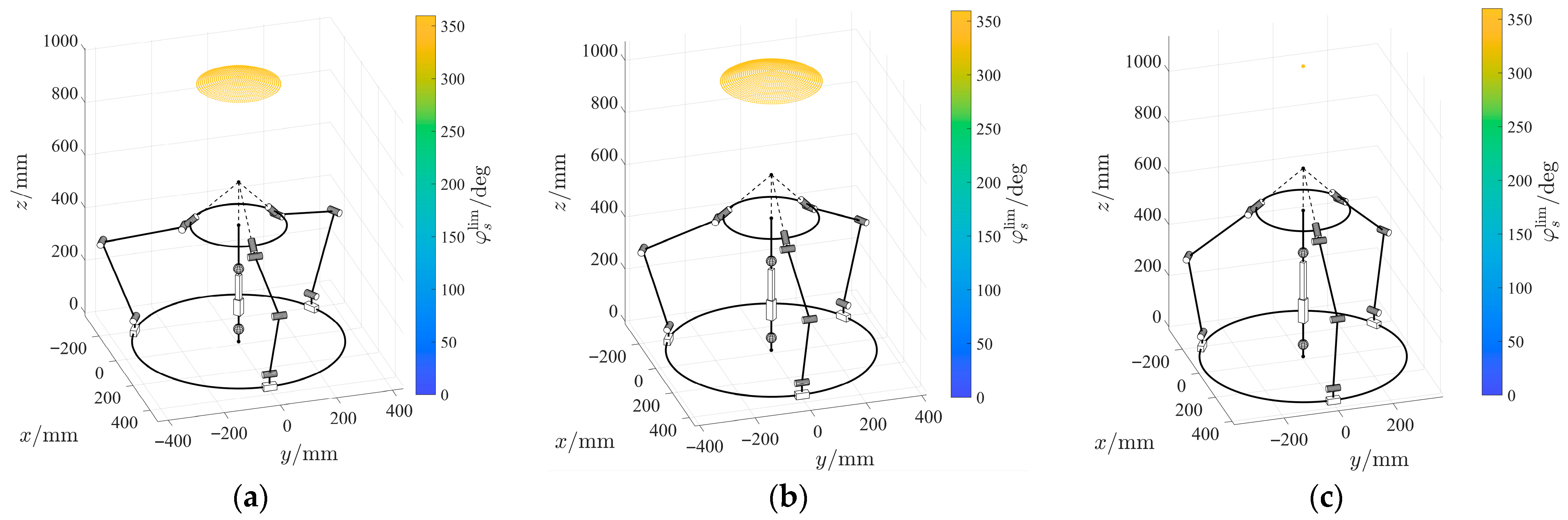

After taking the joint constraints into consideration, we performed the iterative analysis of the workspace with the same parameters as before. The results visualized on a spherical surface are shown in

Figure 7.

We can observe a significant difference compared to the results obtained without considering the joint constraints. For mm, the workspace forms a spherical cap bounded by values of 21°. When mm, the boundary shifts to 26°, and at mm, the moving platform can only be in a horizontal orientation. The latter result is expected since the sum of mm, mm, and the largest feasible value of mm equals exactly 737 mm. Therefore, any tilt of the moving platform increases length beyond the maximum allowed value, and cannot be achieved.

To verify this result, we compared it with the tilt angle limits measured on the CAD model of the mechanism. The measured values were 21.938° when mm (constrained by the maximum allowable angle of the top spherical joint), and 26.261° when mm (constrained by the maximum allowable length of ). By adjusting the range of to [21°, 22°] or [26°, 27°], respectively, and setting the corresponding discretization step to 0.01°, we obtained the values of 21.93° and 26.26° from the iterative analysis in MATLAB.

The analysis performed in this section shows that the proposed mechanism has an important feature: its moving platform has an unconstrained rotation around its axis of symmetry within a certain range of tilt angle . The results also indicate that for the specified dimensions, the workspace size primarily depends on the joint constraints of the central chain, while constraints in the side chains have no effect. Therefore, maximizing the allowable joint angle ranges in the central chain is crucial when designing the actual mechanism.

5. Singularity Analysis

Workspace analysis of parallel mechanisms often requires investigating singular configurations, where its mobility changes instantaneously, resulting in a loss of DOFs or uncontrolled motion of the output link. There are two main approaches to analyzing such configurations. The first approach is based on analyzing the mechanism Jacobian matrix and identifying cases when this matrix becomes singular [

45]. This approach depends on the representation of the rotation matrix and is not always feasible for spherical mechanisms, where the gimbal lock phenomenon may arise. In this case, the Jacobian matrix can become singular even if the mechanism itself is not in a singular configuration. Moreover, this approach does not allow for analyzing constraint singularities [

46], since the Jacobian matrix only considers DOFs of the mechanism corresponding to its mobility in non-singular configurations. Therefore, we adopt the second approach based on screw theory and examine the behavior of the twist and wrench systems of the mechanism [

47].

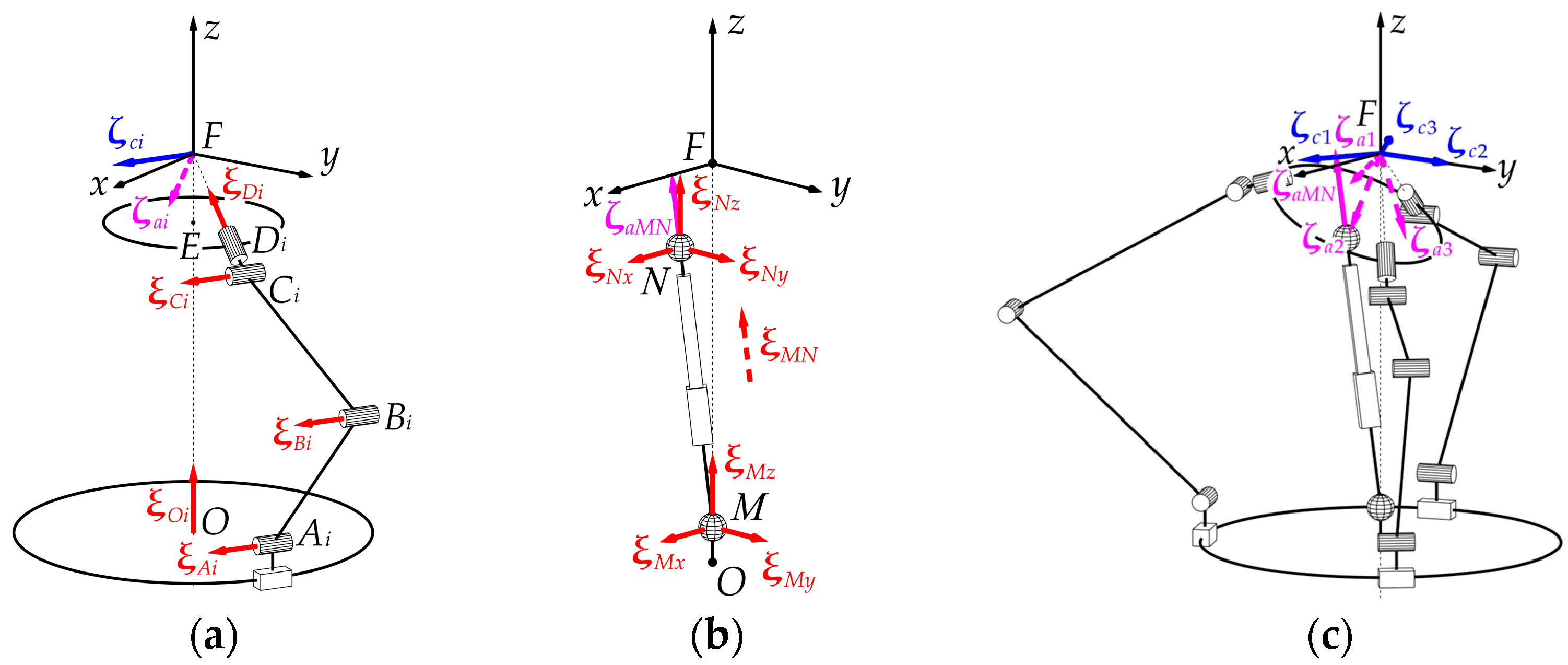

5.1. Twists and Wrenches of the Mechanism

The screw systems of the discussed mechanism were previously identified in [

39] and are shown in

Figure 8.

First, we examine the screws of one of the side chains (

Figure 8a). There are five (unit) zero-pitch twists corresponding to the joints of the chain. The coordinates of these twists are as follows:

where

is the unit vector directed along the

axis of the

reference frame;

is the unit vector parallel to the axis of joint

;

.

In each chain, there is a zero-pitch constraint wrench

, reciprocal to all twists of the chain, and infinite-pitch actuation wrench

, reciprocal only to the twists of the chain passive joints:

For the central chain (

Figure 8b), there is one infinite-pitch twist corresponding to the active prismatic joint and six zero-pitch twists (three for each spherical joint):

where

;

;

is the unit vector directed along line

.

Since the central chain does not impose any constraints on the moving platform, there are no constraint wrenches associated with the chain. The actuation wrench of the chain has the following coordinates:

5.2. Conditions for Different Types of Singular Configurations

There are three main types of singularities: serial, parallel, and constraint. By analyzing the screw systems of the mechanism, we can identify the conditions corresponding to each type of singularity.

When a parallel mechanism is in a serial singularity, its moving platform loses one or more DOFs. In the case of the discussed mechanism, the platform linear motion is possible only along the axis, as any translation in the horizontal plane is constrained by wrenches of the side chains. Vertical motion is realized solely through the prismatic pair in the central chain. Therefore, the translational DOF is lost only if the central chain lies entirely in the horizontal plane, causing vector to have a zero component. This scenario is unlikely in the actual mechanism because of the joint constraints. On the other hand, the rotational DOFs can be constrained only by the side chains, since the spherical joints of the central chain permit this type of motion of the moving platform. By examining the twist system of the side chain, we conclude that the mechanism loses a rotational DOF if vectors , , and become linearly dependent in at least one chain —that is, if they are parallel to the same plane. In this case, all joint axes will be parallel to this plane. By design, is constant and is always orthogonal to both and . Therefore, the vectors lie in the same plane only if is collinear with . This means the mechanism is in a serial singularity if the axis of joint of any side chain aligns with the axis of the reference frame. The moving platform loses the ability to rotate around the axis defined by vector .

Parallel and constraint singularities occur when either the system of actuation wrenches or the system of constraint wrenches loses rank, respectively (

Figure 8c). In the former case, the moving platform exhibits uncontrollable motion consistent with one of its permitted DOFs, whereas in the latter case, the platform gains a new uncontrollable DOF. The constraint wrenches are generated only by the side chains, and this system of wrenches is inherently singular because all these wrenches have a zero pitch, and their axes lie in the same plane, intersecting at point

. Therefore, a constraint singularity can only arise if all three axes of the constraint wrenches are collinear, i.e.,

. This condition can only be met if all links of the three side chains lie in the same plane, which is physically impossible in a real mechanism because of the link interference.

Finally, we examine the system of actuation wrenches. Since wrenches of the side chains have an infinite pitch and wrench of the central chain has a zero pitch, can never become linearly dependent on wrenches . Therefore, the rank of the actuation wrench system can only decrease if the wrenches of the side chains become linearly dependent. This occurs if vectors of all three chains are parallel to the same plane.

5.3. Iterative Workspace Analysis Concerning Parallel Singularities

Unlike serial singularities, parallel singularities have more detrimental effects on mechanism performance. Even approaching singular configurations can lead to a significant decrease in mechanism stiffness, while the loads on the mechanism links and drives increase [

48]. Therefore, it is crucial to identify points in the workspace that correspond to parallel singularities. To achieve this, we analyze the behavior of 3 × 3 matrix

formed from vectors

of the side chains:

If the mechanism is in a parallel singularity, then

, and it changes sign as the mechanism crosses this singularity. We can use the same iterative approach as before to identify the points in the workspace where

, as well as the points where

. The boundary between the regions containing points with different signs of

indicates the loci of parallel singularities. To make the analysis more representative, we perform it without considering the joint constraints.

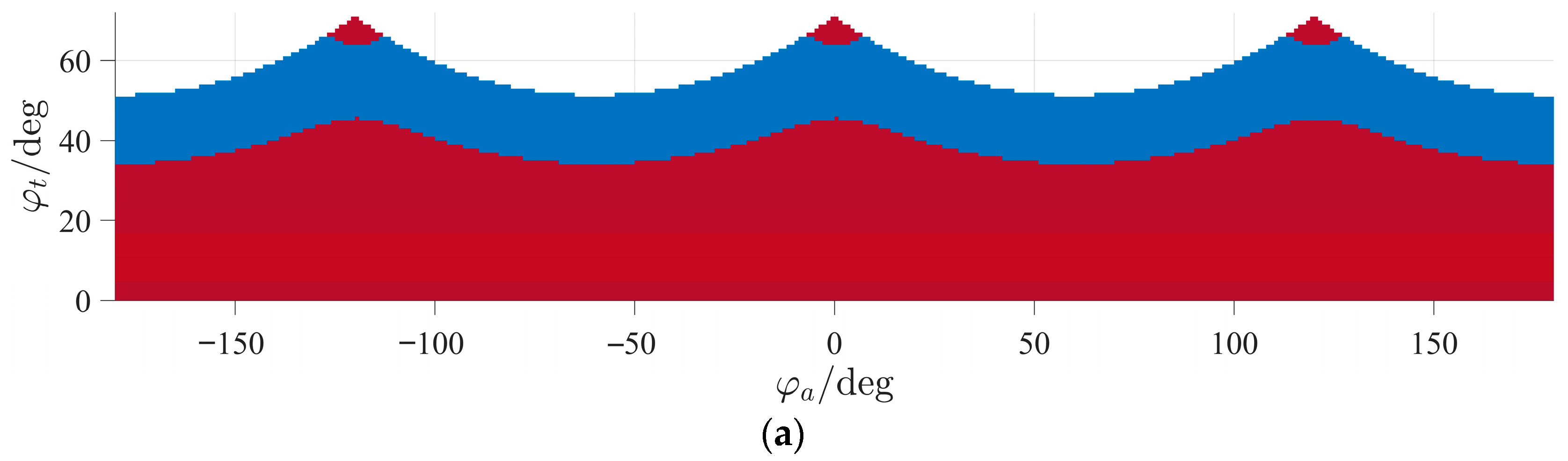

Figure 9 and

Figure 10 show the results for

.

We observe that when mm or mm, the size and shape of the central region, where , remain unchanged. However, at mm, the workspace size is actually smaller than this region (the maximum tilt angle ranges from 33° to 45°, depending on the tilt axis orientation). Therefore, we conclude that the loci of parallel singularities do not depend on . This result is expected since the coordinates of the actuation wrenches depend only on the orientation of the moving platform and its geometry.

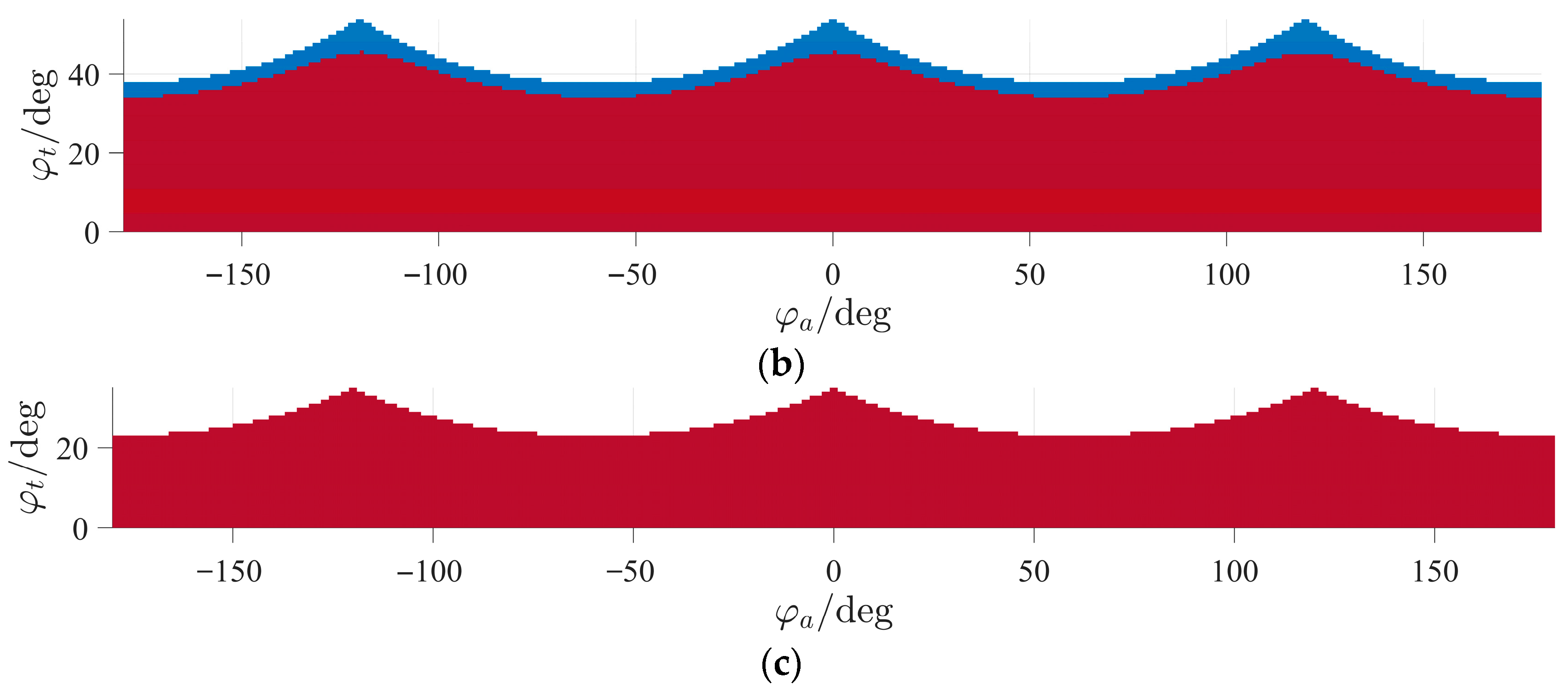

To investigate the behavior of

when twist angle

is not equal to 0°, we examined the values of the determinant for different

,

, and

. We found that

for all

values, as long as tilt angle

does not exceed 33°. If we change azimuth angle

, the plot of

as a function of

“shifts” horizontally without altering its sign (

Figure 11). The function is periodic with a period of 120°. This result holds for all values of

, because vectors

do not depend on this parameter.

Finally, it is also worth mentioning that the previously discussed serial singularity, when becomes horizontal, is simultaneously a parallel singularity. In this case, actuation wrench and constraint wrenches become linearly dependent, providing the moving platform with an uncontrollable vertical translation.

6. Discussion

Workspace and singularity analysis demonstrate that with the specified geometrical parameters and without joint constraints, the moving platform of the mechanism achieves a full twist for tilt angles varying from 23° to 51° (

Figure 5). The value of the maximum tilt angle depends on the height of the pivot point: the higher this point, the lower this value. At the same time, the region of singularity-free tilts with a full twist is limited to 33° (

Figure 11) and does not depend on this height. If we include the joint constraints in the analysis, the maximum tilt angles are reduced further; for example, at an average height of 672 mm, the maximum tilt is 26° (

Figure 7b). This means that the mechanism has a singularity-free workspace where its moving platform can twist unlimitedly. Relaxing the joint constraints increases the maximum tilt angles but decreases the singularity-free region with full twists.

To our knowledge, there are no other 4-DOF parallel mechanisms with a circular rail and a 3R1T motion type. The only mechanism with a similar architecture and motion type found in the literature is a 1-PS/4-

RSS mechanism with coaxial revolute joints [

49], which are kinematically equivalent to a circular rail. The maximum tilt angles of this mechanism also depend on the height of the pivot point. With geometrical parameters optimized for maximum workspace, the tilt angles reach 26° (considering angle constraints in the spherical joints). It is unclear, however, if the moving platform can twist unlimitedly at these tilts, as the optimization was performed for a single twist angle equal to zero. This architecture was inspired by a 1-S/3-

RSS spherical mechanism with coaxial revolute joints [

50], where tilt angles reach 50° (without joint constraints) and 30° (with joint constraints) for any twists within the [–90°, 90°] range. The capability of performing a full twist was also not explicitly stated for this mechanism.

Because of the scarcity of works devoted to 3R1T parallel mechanisms with a circular rail, we find it reasonable to compare our mechanism with spherical mechanisms, which can be considered 3R1T mechanisms with a fixed translational DOF. Among other spherical parallel mechanisms with a circular rail [

2], only a few studies have reported the results of the workspace and singularity analysis. One notable example is a 3-

RRR mechanism [

51], which has a singularity-free workspace with full twist capabilities for tilt angles of at least 45°. This design was later modified into a 3-

RRR mechanism with an adjustable height of the pivot point [

24]. Subsequent studies [

37] show that its tilt angles can reach 90° depending on this height, although singularity-free full-twist tilts are limited to 60°. Identical results were also reported in [

52], where the circular rail was replaced with coaxial revolute joints. All these mechanisms had no joint constraints that could limit their workspace. By contrast, in a similar 3-

RRR mechanism analyzed in [

53], the joint constraints and link interference reduced the tilt angles of singularity-free full twists to 39°. Finally, we should mention a 1-S/3-

RRR mechanism [

54], where the central chain increases the stiffness but limits the maximum tilt angles to 55°. Within this range, the mechanism avoids singular configurations and can perform a full twist.

The comparison results are summarized in

Table 1, where the first row corresponds to the mechanism considered in this work. The table lists the maximum tilt angles reachable by the moving platform with and without joint constraints, along with the maximum tilt angles within a singularity-free workspace. The last column indicates whether the full twist is feasible at the maximum tilt angle. The proposed 1-S

PS/3-

RRRRR mechanism surpasses the 1-PS/4-

RSS mechanism in terms of the maximum singularity-free full-twist workspace, but is outperformed by other spherical mechanisms. This outcome can be attributed to two main factors. First, the joint constraints of the S

PS chain limit the rotational capabilities of the mechanism. Second, its geometrical parameters are derived from the CAD model, whose design has not been optimized yet. This limitation will be addressed in our future studies.

Even with non-optimal geometrical parameters, the singularity-free workspace of the mechanism meets the requirements of ankle rehabilitation procedures [

44], which represents a potential application of the mechanism, as discussed in

Section 2. In this case, the S

PS chain serves a dual purpose: it allows adjusting the height of the moving platform depending on the patient and supports the foot weight. The mechanism can also be used as a waist joint in humanoid robots [

55,

56] to help maintain balance during walking. Unlike the 3-

RRR mechanism with adjustable height [

37], which has also been applied for this purpose, the

RRRRR kinematic chains are less susceptible to bending deformations, as the primary load is supported by the S

PS chain.

7. Conclusions

In this article, we studied the workspace and singularities of a 4-DOF 3R1T spherical parallel mechanism with a circular rail and four kinematic chains: three RRRRR side chains and one central SPS chain.

First, we provided a detailed description of the mechanism along with its CAD model. The main feature of the mechanism is a circular rail, which ensures unlimited rotation of the moving platform around the vertical axis. The central chain supports the weight of the platform and controls the height of the spherical motion center (pivot point).

Next, we presented the closed-form solution to the inverse kinematics. The proposed algorithm allows calculating the active joint coordinates and the coordinates of all points in the stationary reference frame for the specified configuration of the moving platform. Using this algorithm, we can fully describe the spatial configuration of the mechanism.

The inverse kinematics solution algorithm was applied to analyze the workspace through an iterative approach. Based on the geometrical parameters derived from the CAD model, we performed the analysis for three different heights of the pivot point and identified workspace regions with a full twist around the platform axis of symmetry. The results demonstrate that the maximum tilt angles with a full twist vary from 23° to 51°, depending on the pivot point height. After introducing the joint constraints, these values are reduced to 26° at an average height.

Lastly, using the screw theory-based approach, we identified the conditions for serial, parallel, and constraint singularities. The analysis shows that the constraint singularities will not be met in a real mechanism because of the link interference, making parallel singularities the primary concern. Using the same iterative approach as before, we identified the boundary of the singularity-free region within the workspace. For the specified geometrical parameters, the singularity-free full-twist tilt angles are limited to 33° and do not depend on the height of the pivot point.

The results obtained in this study establish a foundation for future research, design optimization, and prototyping of the mechanism. In particular, we will address its parametric synthesis to maximize a singularity-free workspace where the moving platform can perform a full twist.