From Latent Manifolds to Targeted Molecular Probes: An Interpretable, Kinome-Scale Generative Machine Learning Framework for Family-Based Kinase Ligand Design

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Sets of Protein Kinase Ligands and Small Molecules

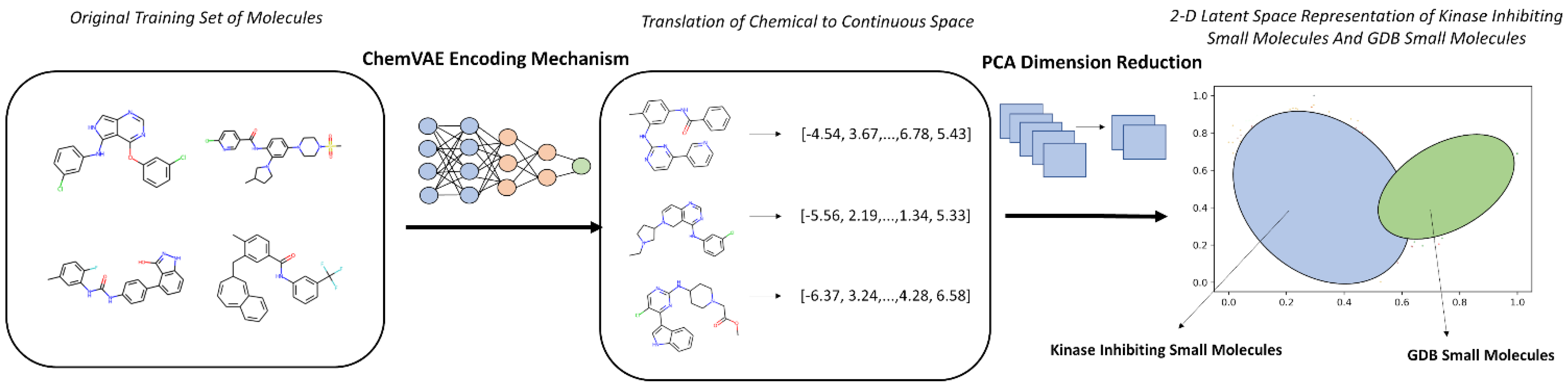

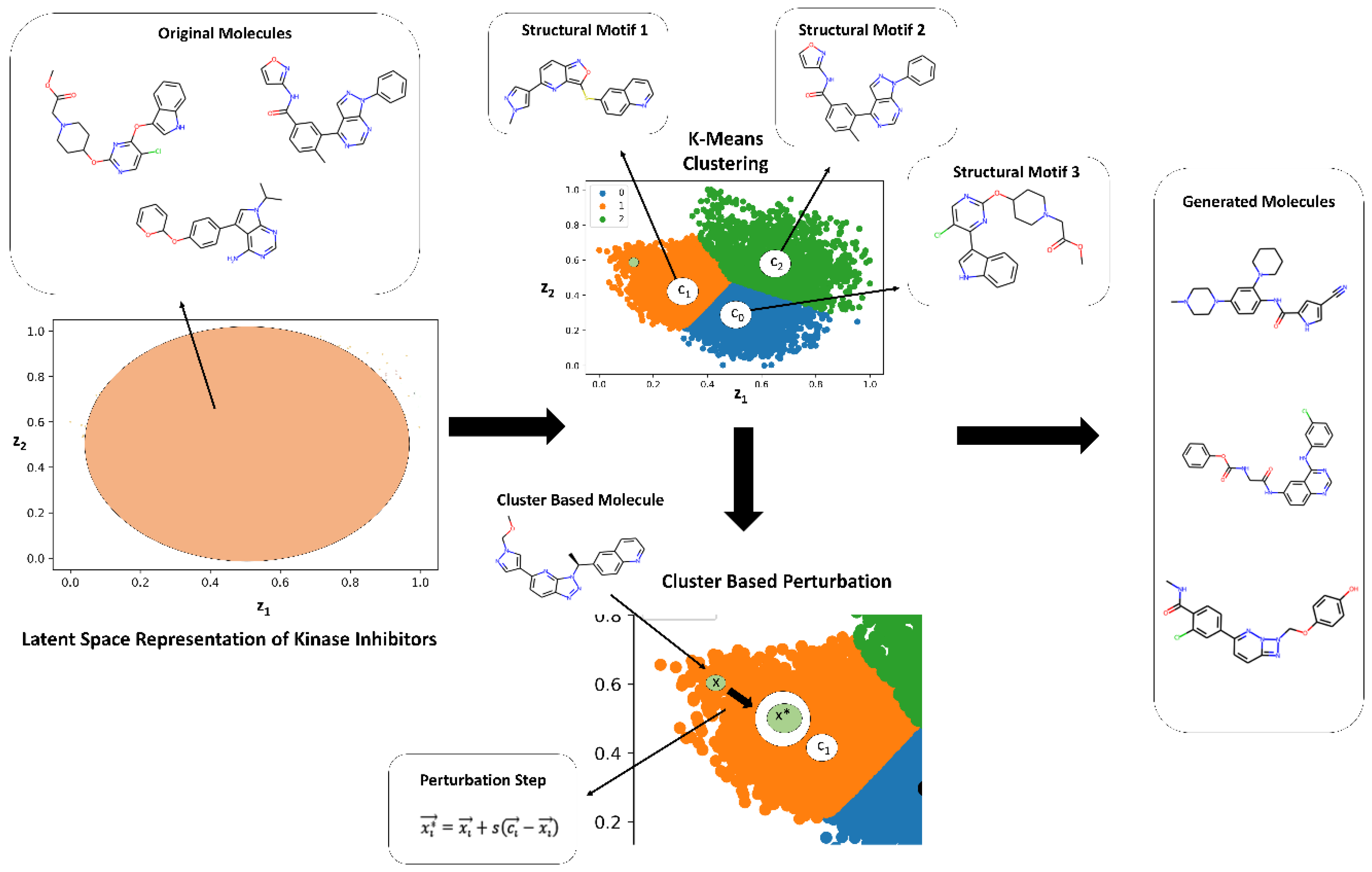

2.2. Guided Remodeling of Latent Neighborhoods via Cluster-Directed Sampling

2.3. Kinase Association Likelihood Classifier

2.4. Bayesian Optimization for Global Exploration of Latent Space

3. Results and Discussion

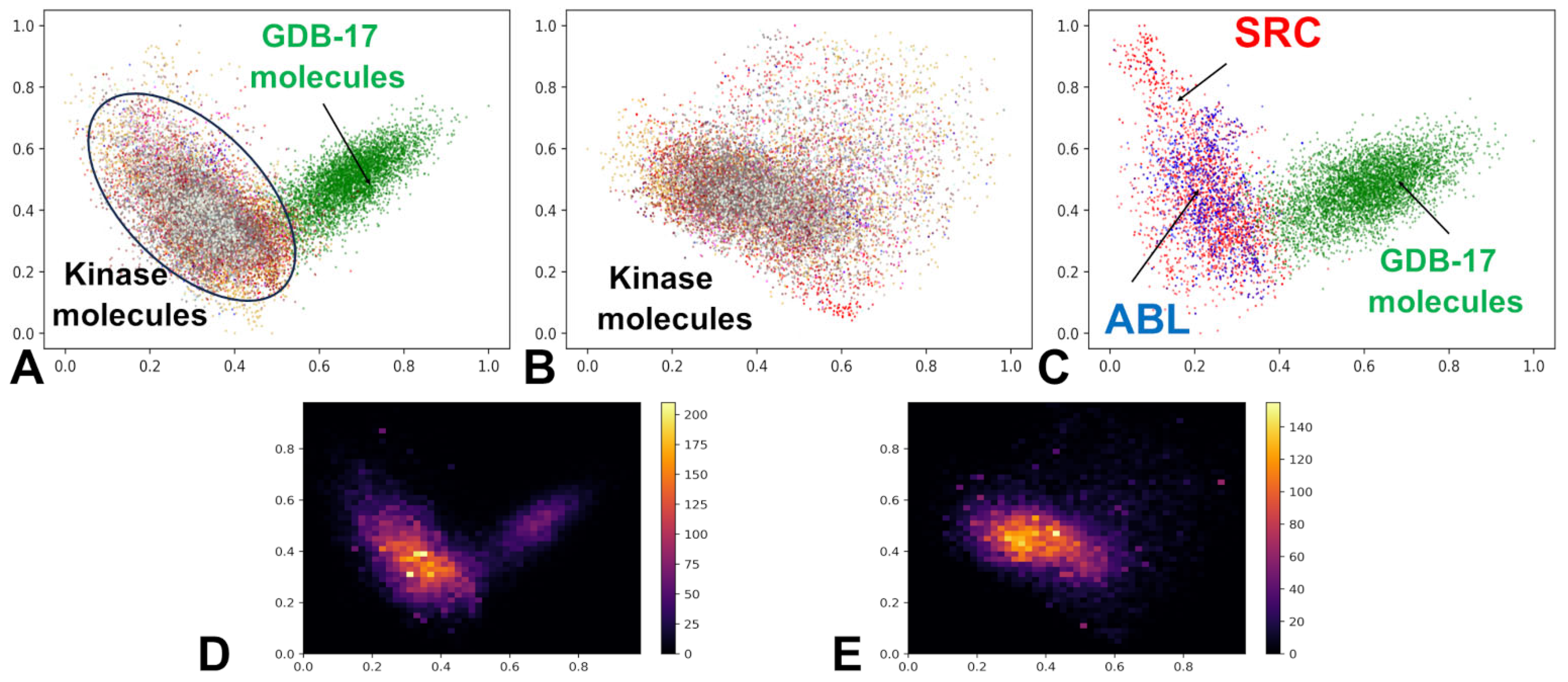

3.1. The Kinase Ligand Dataset and Its Embedding Reveals Organized Kinome Manifold in Latent Space

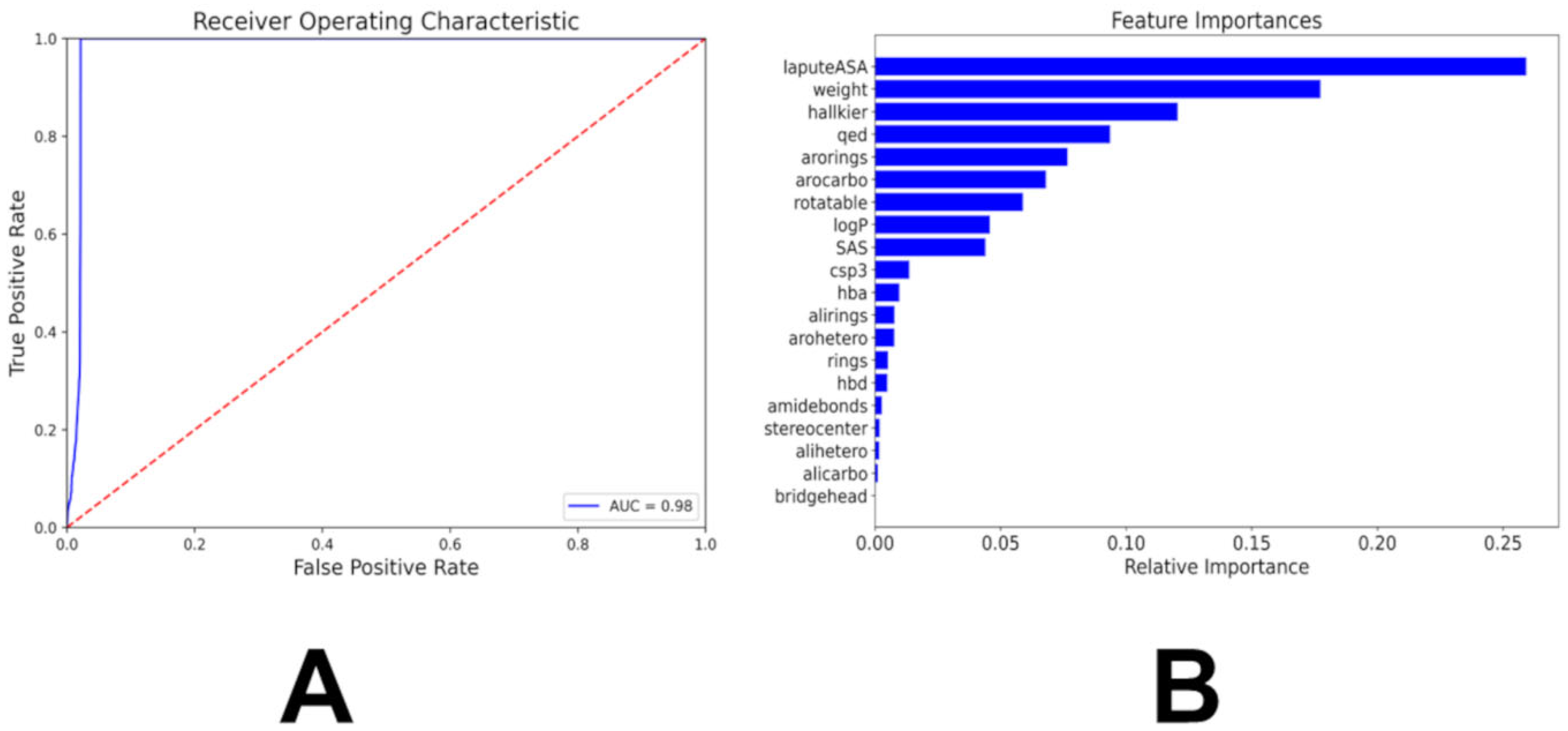

3.2. Multiclass and Binary Kinase Association Likelihood Classifiers

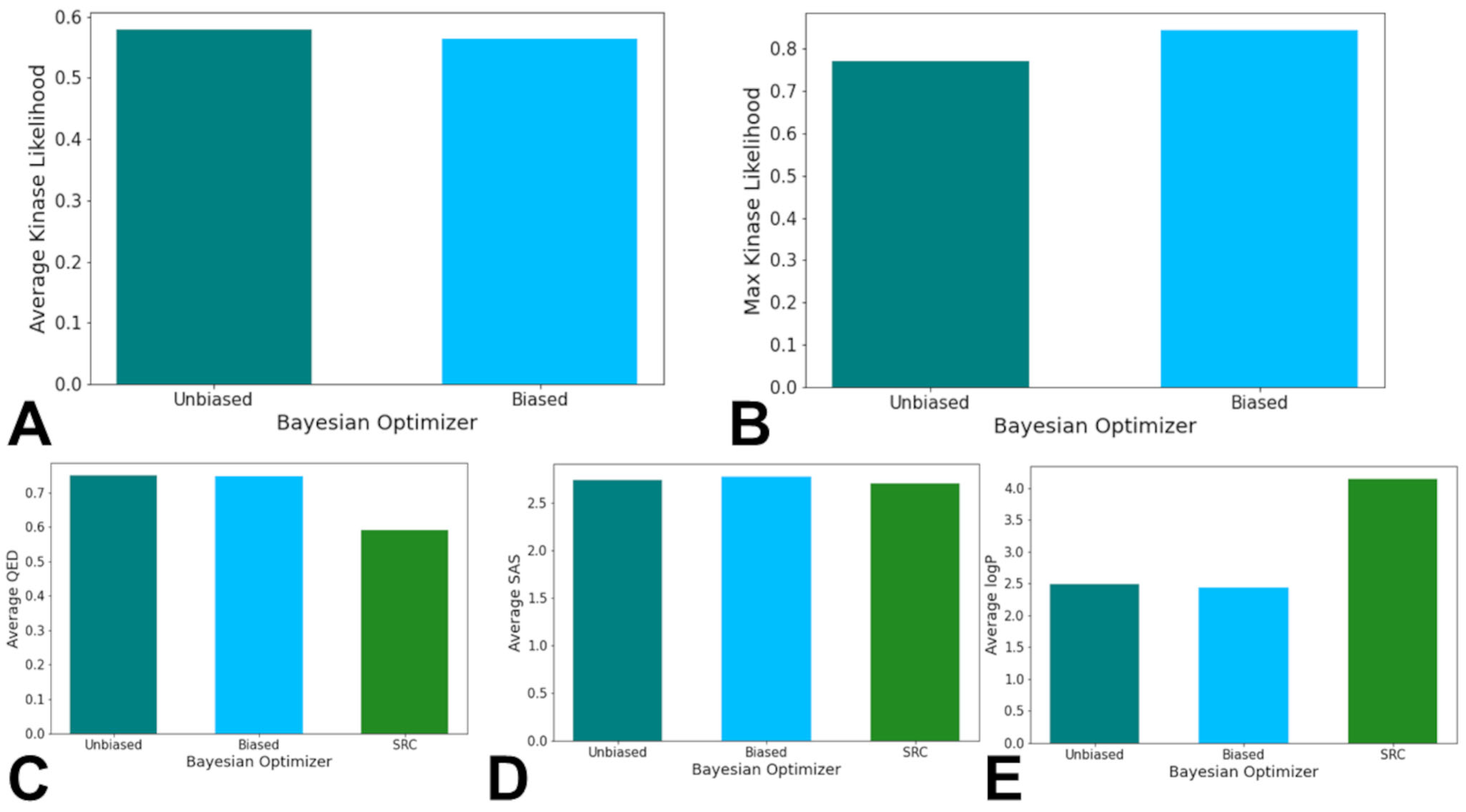

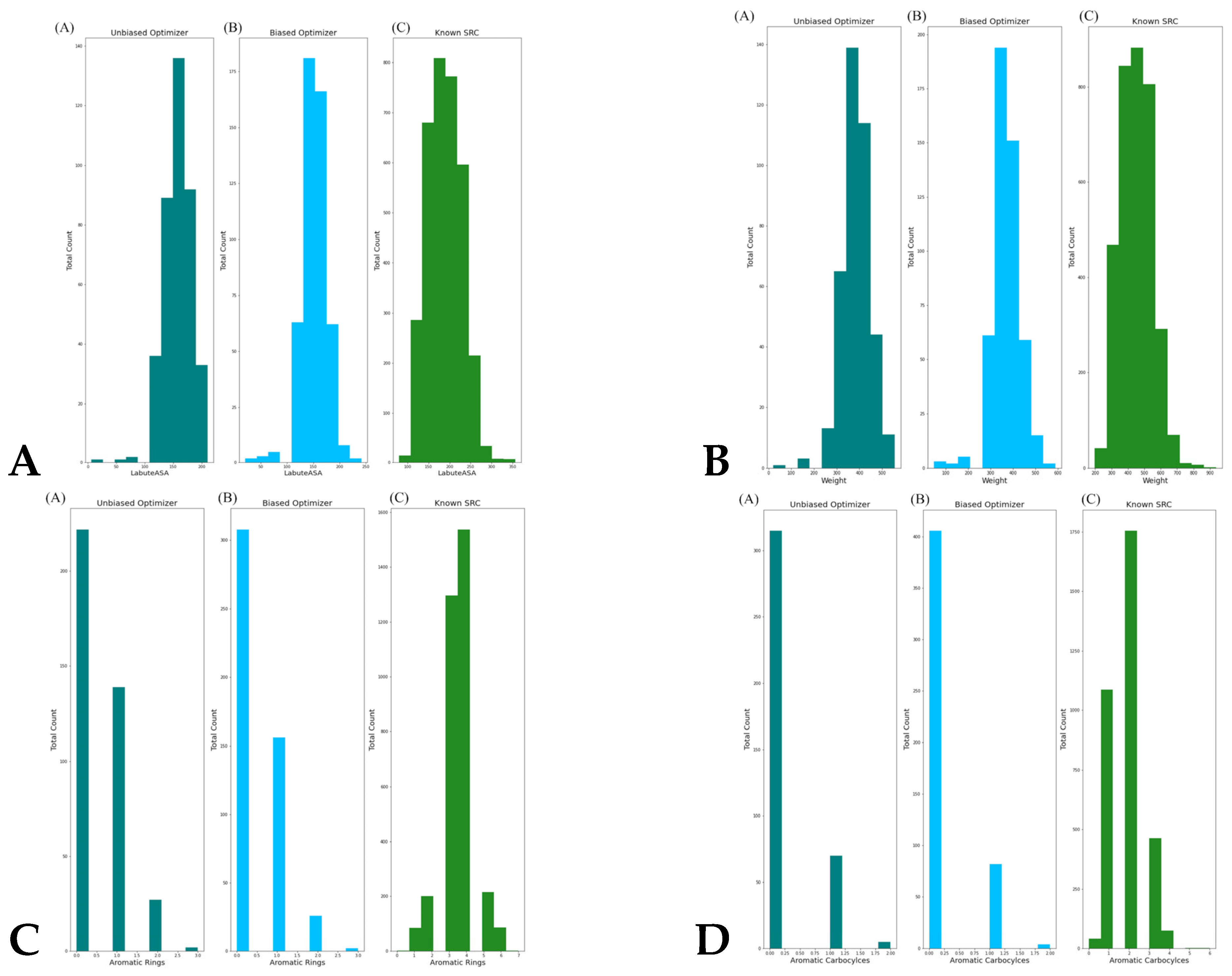

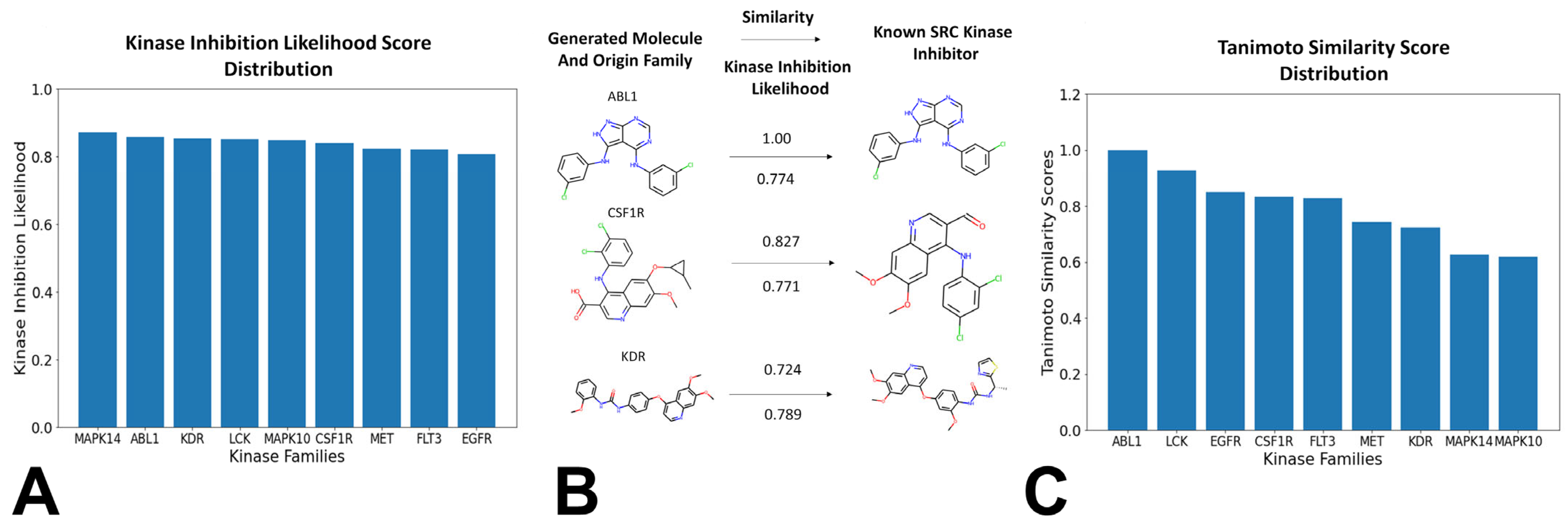

3.3. Bayesian Optimization Enables Efficient Exploration of SRC Kinase Ligand Chemical Space

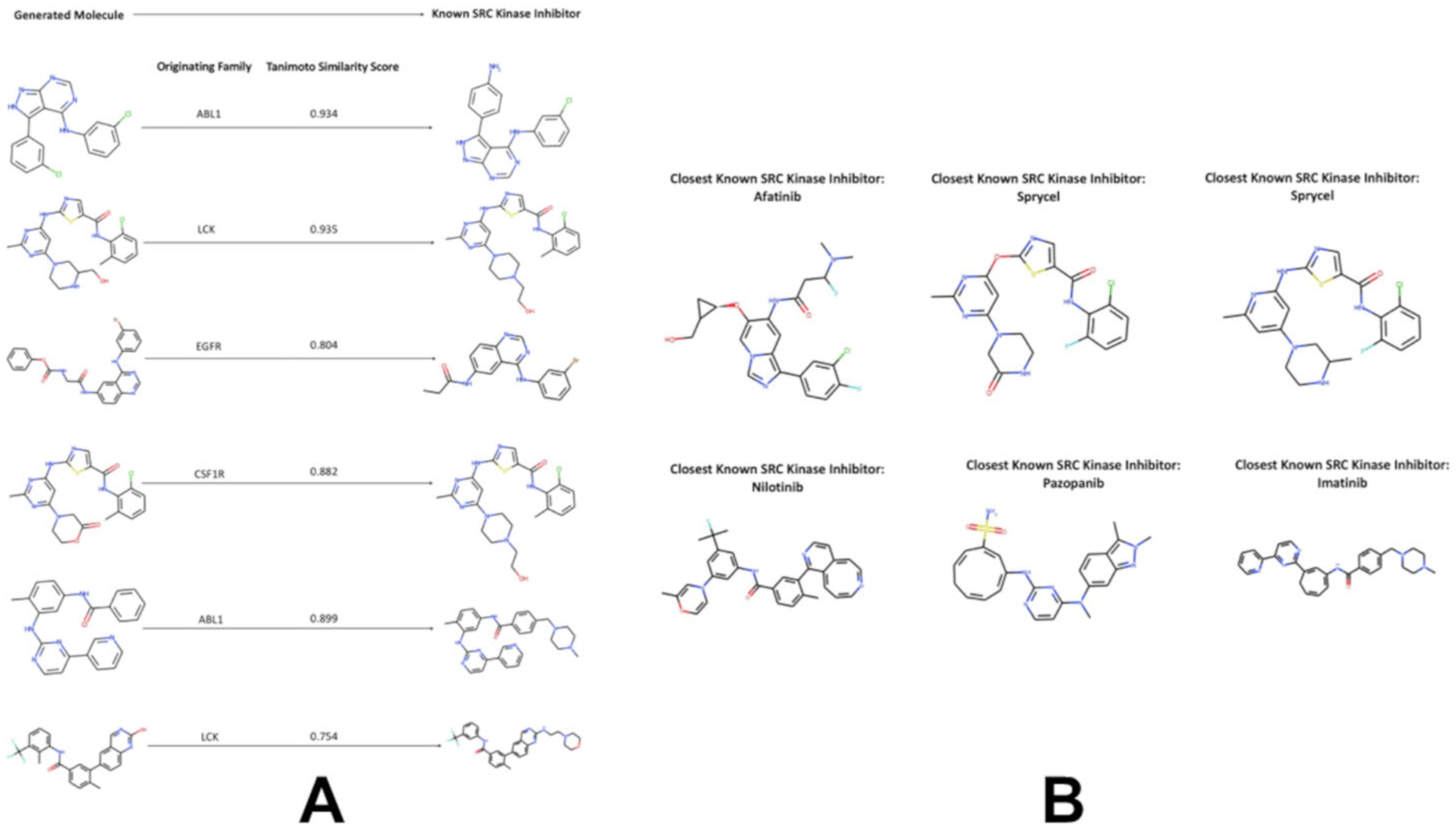

3.4. Targeted Local Latent Neighborhood Sampling Recovers Pharmacophoric Complexity

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- White, D.; Wilson, R.C. Generative models for chemical structures. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2010, 50, 1257–1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goh, G.B.; Hodas, N.O.; Vishnu, A. Deep learning for computational chemistry. J. Comput. Chem. 2017, 38, 1291–1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mater, A.C.; Coote, M.L. Deep Learning in Chemistry. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2019, 59, 2545–2559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, H.; Engkvist, O.; Wang, Y.; Olivecrona, M.; Blaschke, T. The rise of deep learning in drug discovery. Drug Discov. Today 2018, 23, 1241–1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popova, M.; Isayev, O.; Tropsha, A. Deep reinforcement learning for De Novo drug design. Sci. Adv. 2018, 4, eaap7885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitrov, T.; Kreisbeck, C.; Becker, J.S.; Aspuru-Guzik, A.; Saikin, S.K. Autonomous Molecular Design: Then and Now. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2019, 11, 24825–24836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korotcov, A.; Tkachenko, V.; Russo, D.P.; Ekins, S. Comparison of Deep Learning with Multiple Machine Learning Methods and Metrics Using Diverse Drug Discovery Data Sets. Mol. Pharm. 2017, 14, 4462–4475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Lengeling, B.; Aspuru-Guzik, A. Inverse molecular design using machine learning: Generative models for matter engineering. Science 2018, 361, 360–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez-Bombarelli, R.; Wei, J.N.; Duvenaud, D.; Hernández- Lobato, J.M.; Sanchez- Lengeling, B.; Sheberla, D.; Aguilera-Iparraguirre, J.; Hirzel, T.D.; Adams, R.P.; Aspuru-Guzik, A. Automatic Chemical Design Using a Data-Driven Continuous Representation of Molecules. ACS Cent. Sci. 2018, 4, 268–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, W.; Jiang, D.; Nambiar, D.K.; Liew, L.P.; Hay, M.P.; Bloomstein, J.; Lu, P.; Turner, B.; Le, Q.-T.; Tibshirani, R.; et al. Chemical Space Mimicry for Drug Discovery. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2017, 57, 875–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segler, M.H.; Kogej, T.; Tyrchan, C.; Waller, M.P. Generating focused molecule libraries for drug discovery with recurrent neural networks. ACS Cent. Sci. 2018, 4, 120–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elton, D.C.; Boukouvalas, Z.; Fuge, M.D.; Chung, P.W. Deep learning for molecular design—A review of the state of the art. Mol. Syst. Des. Eng. 2019, 4, 828–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bian, Y.; Xie, X.-Q. Generative chemistry: Drug discovery with deep learning generative models. J. Mol. Model. 2021, 27, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, F.; Diao, X.; Chang, S.; Xu, L. Recent Progress of Deep Learning in Drug Discovery. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2021, 27, 2088–2096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vamathevan, J.; Clark, D.; Czodrowski, P.; Dunham, I.; Ferran, E.; Lee, G.; Li, B.; Madabhushi, A.; Shah, P.; Spitzer, M.; et al. Applications of machine learning in drug discovery and development. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2019, 18, 463–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, T.; Correia, J.; Pereira, V.; Rocha, M. Generative Deep Learning for Targeted Compound Design. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2021, 61, 5343–5361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodfellow, I.; Pouget-Abadie, J.; Mirza, M.; Xu, B.; Warde-Farley, D.; Ozair, S.; Courville, A.; Bengio, Y. Generative Adversarial Nets. Adv. Neural Inf. Proc. Syst. 2014, 2, 2672−2680. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, L.; Zhang, W.; Wang, J.; Yu, Y. SeqGAN: Sequence Generative Adversarial Nets with Policy Gradient. In Proceedings of the Thirty-First AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence (AAAI-17), San Francisco, CA, USA, 4–9 February 2017; pp. 2852–2858. [Google Scholar]

- Guimaraes, G.L.; Sanchez-Lengeling, B.; Outeiral, C.; Farias, P.L.C.; Aspuru-Guzik, A. Objective-reinforced generative adversarial networks (ORGAN) for sequence generation models. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1705.10843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olivecrona, M.; Blaschke, T.; Engkvist, O.; Chen, H. Molecular de-novo design through deep reinforcement learning. J. Cheminform. 2017, 9, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Lengeling, B.; Outeiral, C.; Guimaraes, G.L.; Aspuru-Guzik, A. Optimizing distributions over molecular space. An Objective-Reinforced Generative Adversarial Network for Inverse-design Chemistry (ORGANIC). ChemRxiv 2017, 5309668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prykhodko, O.; Johansson, S.V.; Kotsias, P.C.; Arús-Pous, J.; Bjerrum, E.J.; Engkvist, O.; Chen, H. A De Novo molecular generation method using latent vector based generative adversarial network. J. Cheminform. 2019, 11, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kadurin, A.; Nikolenko, S.; Khrabrov, K.; Aliper, A.; Zhavoronkov, A. druGAN: An Advanced Generative Adversarial Autoencoder Model for De Novo Generation of New Molecules with Desired Molecular Properties in Silico. Mol. Pharm. 2017, 14, 3098–3104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Putin, E.; Asadulaev, A.; Ivanenkov, Y.; Aladinskiy, V.; Sanchez-Lengeling, B.; Aspuru-Guzik, A.; Zhavoronkov, A. Reinforced Adversarial Neural Computer for De Novo Molecular Design. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2018, 58, 1194–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Putin, E.; Asadulaev, A.; Vanhaelen, Q.; Ivanenkov, Y.; Aladinskaya, A.V.; Aliper, A.; Zhavoronkov, A. Adversarial Threshold Neural Computer for Molecular De Novo Design. Mol. Pharm. 2018, 15, 4386–4397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.; Muller, A.T.; Huisman, B.J.H.; Fuchs, J.A.; Schneider, P.; Schneider, G. Generative Recurrent Networks for De Novo Drug Design. Mol. Inform. 2018, 37, 1700111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadurin, A.; Aliper, A.; Kazennov, A.; Mamoshina, P.; Vanhaelen, Q.; Khrabrov, K.; Zhavoronkov, A. The cornucopia of meaningful leads: Applying deep adversarial autoencoders for new molecule development in oncology. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 10883–10890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polykovskiy, D.; Zhebrak, A.; Vetrov, D.; Ivanenkov, Y.; Aladinskiy, V.; Mamoshina, P.; Bozdaganyan, M.; Aliper, A.; Zhavoronkov, A.; Kadurin, A. Entangled Conditional Adversarial Autoencoder for De Novo Drug Discovery. Mol. Pharm. 2018, 15, 4398–4405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, N.; Kipf, T. MolGAN: An implicit generative model for small molecular graphs. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1805.11973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.-Y.; Park, T.; Isola, P.; Efros, A.A. Unpaired Image-to-Image Translation using Cycle-Consistent Adversarial Networks. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1703.10593v6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maziarka, L.; Pocha, A.; Kaczmarczyk, J.; Rataj, K.; Warchol, M. Mol-CycleGAN—A generative mode, for molecular optimization. J. Cheminform. 2020, 12, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Racz, A.; Bajusz, D.; Heberger, K. Multi-Level Comparison of Machine Learning Classifiers and Their Performance Metrics. Molecules 2019, 24, 2811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olson, R.S.; La Cava, W.; Orzechowski, P.; Urbanowicz, R.J.; Moore, J.H. PMLB: A large benchmark suite for machine learning evaluation and comparison. BioData Min. 2017, 10, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polykovskiy, D.; Zhebrak, A.; Sanchez-Lengeling, B.; Golovanov, S.; Tatanov, O.; Belyaev, S.; Kurbanov, R.; Artamonov, A.; Aladinskiy, V.; Veselov, M.; et al. Molecular Sets (MOSES): A Benchmarking Platform for Molecular Generation Models. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 11, 565644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preuer, K.; Renz, P.; Unterthiner, T.; Hochreiter, S.; Klambauer, G. Fréchet ChemNet Distance: A Metric for Generative Models for Molecules in Drug Discovery. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2018, 58, 1736–1741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, N.; Fiscato, M.; Segler, M.H.S.; Vaucher, A.C. GuacaMol: Benchmarking Models for De Novo Molecular Design. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2019, 59, 1096–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bickerton, G.R.; Paolini, G.V.; Besnard, J.; Muresan, S.; Hopkins, A.L. Quantifying the chemical beauty of drugs. Nat. Chem. 2012, 4, 90–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ertl, P.; Schuffenhauer, A. Estimation of synthetic accessibility score of drug-like molecules based on molecular complexity and fragment contributions. J. Cheminform. 2009, 1, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchwald, P.; Bodor, N. Octanol-water partition: Searching for predictive models. Curr. Med. Chem. 1998, 5, 353–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blaschke, T.; Arús-Pous, J.; Chen, H.; Margreitter, C.; Tyrchan, C.; Engkvist, O.; Papadopoulos, K.; Patronov, A. REINVENT 2.0: An AI Tool for De Novo Drug Design. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2020, 60, 5918–5922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loeffler, H.H.; He, J.; Tibo, A.; Janet, J.P.; Voronov, A.; Mervin, L.H.; Engkvist, O. Reinvent 4: Modern AI–Driven Generative Molecule Design. J. Cheminform. 2024, 16, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhavoronkov, A.; Ivanenkov, Y.A.; Aliper, A.; Veselov, M.S.; Aladinskiy, V.A.; Aladinskaya, A.V.; Terentiev, V.A.; Polykovskiy, D.A.; Kuznetsov, M.D.; Asadulaev, A.; et al. Deep learning enables rapid identification of potent DDR1 kinase inhibitors. Nat. Biotechnol. 2019, 37, 1038–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dollar, O.; Joshi, N.; Beck, D.A.C.; Pfaendtner, J. Attention-based generative models for De Novo molecular design. Chem. Sci. 2021, 12, 8362–8372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winter, R.; Montanari, F.; Noé, F.; Clevert, D.A. Learning continuous and data-driven molecular descriptors by translating equivalent chemical representations. Chem. Sci. 2018, 10, 1692–1701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winter, R.; Montanari, F.; Steffen, A.; Briem, H.; Noé, F.; Clevert, D.A. Efficient multi-objective molecular optimization in a continuous latent space. Chem. Sci. 2019, 10, 8016–8024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winter, R.; Retel, J.; Noé, F.; Clevert, D.A.; Steffen, A. Grünifai: Interactive multiparameter optimization of molecules in a continuous vector space. Bioinformatics 2020, 36, 4093–4094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoffman, S.C.; Chenthamarakshan, V.; Wadhawan, K.; Cen, P.-Y.; Das, P. Optimizing molecules using efficient queries from property evaluations. Nat. Mach. Intell. 2022, 4, 21–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Sun, H.; Wang, J.; Pang, J.; Chai, X.; Xu, L.; Li, H.; Cao, D.; Hou, T. Comprehensive assessment of deep generative architectures for De Novo drug design. Brief. Bioinform. 2022, 23, bbab544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Guo, Y.; Wang, Y.; Sun, H.; Huang, J. Smiles-Bert: Large scale unsupervised pre-training for molecular property prediction. In Proceedings of the 10th ACM International Conference on Bioinformatics, Computational Biology and Health Informatics, Niagara Falls, NY, USA, 7–10 September 2019; pp. 429–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irwin, R.; Dimitriadis, S.; He, J.; Bjerrum, E.J. Chemformer: A Pre-Trained Transformer for Computational Chemistry. Mach. Learn. Sci. Technol. 2022, 3, 015022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westerlund, A.M.; Manohar Koki, S.; Kancharla, S.; Tibo, A.; Saigiridharan, L.; Kabeshov, M.; Mercado, R.; Genheden, S. Do Chemformers Dream of Organic Matter? Evaluating a Transformer Model for Multistep Retrosynthesis. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2024, 64, 3021–3033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Kearnes, S.; Li, L.; Zare, R.N.; Riley, P. Author Correction: Optimization of Molecules via Deep Reinforcement Learning. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 10478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Lin, K.; Wang, S.; Wang, L.; Cai, C.; Song, C.; Lai, L.; Pei, J. Deep learning for molecular generation. Future Med. Chem. 2019, 11, 567–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Chen, H. De Novo Molecule Design Using Molecular Generative Models Constrained by Ligand-Protein Interactions. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2022, 62, 3291–3306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Pei, J.; Lai, L. Structure-based De Novo drug design using 3D deep generative models. Chem. Sci. 2021, 12, 13664–13675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, W.; Wang, F.; Li, Y.; Lai, L.; Pei, J. Advances and Challenges in De Novo Drug Design Using Three-Dimensional Deep Generative Models. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2022, 62, 2269–2279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gilmer, J.; Schoenholz, S.S.; Riley, P.F.; Vinyals, O.; Dahl, G.E. Neural Message Passing for Quantum Chemistry. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1704.01212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kearnes, S.; McCloskey, K.; Berndl, M.; Pande, V.; Riley, P. Molecular Graph Convolutions: Moving beyond Fingerprints. J. Comput.-Aided Mol. Des. 2016, 30, 595–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veličković, P.; Cucurull, G.; Casanova, A.; Romero, A.; Liò, P.; Bengio, Y. Graph Attention Networks. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1710.10903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, K.; Swanson, K.; Jin, W.; Coley, C.; Eiden, P.; Gao, H.; Guzman-Perez, A.; Hopper, T.; Kelley, B.; Mathea, M.; et al. Analyzing Learned Molecular Representations for Property Prediction. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2019, 59, 3370–3388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, W.; Barzilay, R.; Jaakkola, T. Junction Tree Variational Autoencoder for Molecular Graph Generation. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1802.04364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, C.; Xu, M.; Zhu, Z.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, M.; Tang, J. GraphAF: A Flow-Based Autoregressive Model for Molecular Graph Generation. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2001.09382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bengio, E.; Jain, M.; Korablyov, M.; Precup, D.; Bengio, Y. Flow network based generative models for non-iterative diverse candidate generation. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 34: Proceedings of the Neural Information Processing Systems Conference (NeurIPS 2021), Virtual, 6–14 December 2021; pp. 7924–7936. [Google Scholar]

- Jain, M.; Deleu, T.; Hartford, J.; Liu, C.-H.; Hernandez-Garcia, A.; Bengio, Y. GFlowNets for AI-Driven Scientific Discovery. Digit. Discov. 2023, 2, 557–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schütt, K.T.; Kindermans, P.-J.; Sauceda, H.E.; Chmiela, S.; Tkatchenko, A.; Müller, K.R. SchNet: A continuous-filter convolutional neural network for modeling quantum interactions. In Proceedings of the NIPS’17: Proceedings of the 31st International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, Long Beach, CA, USA, 4–9 December 2017; pp. 992–1002. [Google Scholar]

- Schütt, K.T.; Arbabzadah, F.; Chmiela, S.; Müller, K.R.; Tkatchenko, A. Quantum-Chemical Insights from Deep Tensor Neural Networks. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 13890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gasteiger, J.; Groß, J.; Günnemann, S. Directional Message Passing for Molecular Graphs. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2003.03123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gasteiger, J.; Giri, S.; Margraf, J.T.; Günnemann, S. Fast and Uncertainty-Aware Directional Message Passing for Non-Equilibrium Molecules. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2011.14115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stärk, H.; Ganea, O.-E.; Pattanaik, L.; Barzilay, R.; Jaakkola, T. EquiBind: Geometric Deep Learning for Drug Binding Structure Prediction. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2202.05146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, W.; Wu, Q.; Zhang, J.; Rao, J.; Li, C.; Zheng, S. TANKBind: Trigonometry-Aware Neural NetworKs for Drug-Protein Binding Structure Prediction. bioRxiv 2022, 495043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Wang, H.; Liu, W.; Lasenby, J.; Guo, H.; Tang, J. Pre-Training Molecular Graph Representation with 3D Geometry. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2110.07728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stärk, H.; Beaini, D.; Corso, G.; Tossou, P.; Dallago, C.; Günnemann, S.; Liò, P. 3D Infomax Improves GNNs for Molecular Property Prediction. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2110.04126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhao, H.; Tu, W.; Yao, Q. Automated 3D Pre-Training for Molecular Property Prediction. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2306.07812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, M.; Yu, L.; Song, Y.; Shi, C.; Ermon, S.; Tang, J. GeoDiff: A Geometric Diffusion Model for Molecular Conformation Generation. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2203.02923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, H.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, M.; Zhong, B.; Li, Q.; Zhong, Y.; Wu, Y.; Ying, T.; Tang, J. Pretrainable Geometric Graph Neural Network for Antibody Affinity Maturation. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 7785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jing, B.; Corso, G.; Chang, J.; Barzilay, R.; Jaakkola, T. Torsional Diffusion for Molecular Conformer Generation. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2206.01729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corso, G.; Stärk, H.; Jing, B.; Barzilay, R.; Jaakkola, T. DiffDock: Diffusion Steps, Twists, and Turns for Molecular Docking. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2210.01776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corso, G.; Deng, A.; Fry, B.; Polizzi, N.; Barzilay, R.; Jaakkola, T. Deep Confident Steps to New Pockets: Strategies for Docking Generalization. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2402.18396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.; Yi, H.-C.; You, Z.-H. Equivariant 3D-Conditional Diffusion Model for De Novo Drug Design. IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inform. 2025, 29, 1805–1816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, J.L.; Juergens, D.; Bennett, N.R.; Trippe, B.L.; Yim, J.; Eisenach, H.E.; Ahern, W.; Borst, A.J.; Ragotte, R.J.; Milles, L.F.; et al. De Novo Design of Protein Structure and Function with RFdiffusion. Nature 2023, 620, 1089–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dauparas, J.; Anishchenko, I.; Bennett, N.; Bai, H.; Ragotte, R.J.; Milles, L.F.; Wicky, B.I.M.; Courbet, A.; de Haas, R.J.; Bethel, N.; et al. Robust Deep Learning–Based Protein Sequence Design Using ProteinMPNN. Science 2022, 378, 49–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, T.; Rao, R.; Akin, H.; Sofroniew, N.J.; Oktay, D.; Lin, Z.; Verkuil, R.; Tran, V.Q.; Deaton, J.; Wiggert, M.; et al. Simulating 500 Million Years of Evolution with a Language Model. Science 2025, 387, 850–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingraham, J.B.; Baranov, M.; Costello, Z.; Barber, K.W.; Wang, W.; Ismail, A.; Frappier, V.; Lord, D.M.; Ng-Thow-Hing, C.; Van Vlack, E.R.; et al. Illuminating Protein Space with a Programmable Generative Model. Nature 2023, 623, 1070–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fey, M.; Lenssen, J.E. Fast Graph Representation Learning with PyTorch Geometric. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1903.02428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Zheng, D.; Ye, Z.; Gan, Q.; Li, M.; Song, X.; Zhou, J.; Ma, C.; Yu, L.; Gai, Y.; et al. Deep Graph Library: A Graph-Centric, Highly-Performant Package for Graph Neural Networks. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1909.01315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, K.; Fu, T.; Gao, W.; Zhao, Y.; Roohani, Y.; Leskovec, J.; Coley, C.W.; Xiao, C.; Sun, J.; Zitnik, M. Therapeutics Data Commons: Machine Learning Datasets and Tasks for Drug Discovery and Development. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2102.09548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnan, K.; Kassab, R.; Agajanian, S.; Verkhivker, G. Interpretable Machine Learning Models for Molecular Design of Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors Using Variational Autoencoders and Perturbation-Based Approach of Chemical Space Exploration. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 11262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davies, M.; Nowotka, M.; Papadatos, G.; Dedman, N.; Gaulton, A.; Atkinson, F.; Bellis, L.; Overington, J.P. ChEMBL web services: Streamlining access to drug discovery data and utilities. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015, 43, W612–W620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wishart, D.S.; Feunang, Y.D.; Guo, A.C.; Lo, E.J.; Marcu, A.; Grant, J.R.; Sajed, T.; Johnson, D.; Li, C.; Sayeeda, Z.; et al. DrugBank 5.0: A major update to the DrugBank database for 2018. Nucleic Acids Res 2018, 46, D1074–D1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knox, C.; Wilson, M.; Klinger, C.M.; Franklin, M.; Oler, E.; Wilson, A.; Pon, A.; Cox, J.; Chin, N.E.L.; Strawbridge, S.A.; et al. DrugBank 6.0: The DrugBank Knowledgebase for 2024. Nucleic Acids Res. 2024, 52, D1265–D1275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Hwang, L.; Burley, S.K.; Nitsche, C.I.; Southan, C.; Walters, W.P.; Gilson, M.K. BindingDB in 2024: A FAIR Knowledgebase of Protein-Small Molecule Binding Data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2025, 53, D1633–D1644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, A.; Smith, R.D.; Clark, J.J.; Dunbar, J.B., Jr.; Carlson, H.A. Recent improvements to Binding MOAD: A resource for protein-ligand binding affinities and structures. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015, 43, D465–D469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hastings, J.; de Matos, P.; Dekker, A.; Ennis, M.; Harsha, B.; Kale, N.; Muthukrishnan, V.; Owen, G.; Turner, S.; Williams, M.; et al. The ChEBI reference database and ontology for biologically relevant chemistry: Enhancements for 2013. Nucleic Acids Res 2013, 41, D456–D463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irwin, J.J.; Sterling, T.; Mysinger, M.M.; Bolstad, E.S.; Coleman, R.G. ZINC: A free tool to discover chemistry for biology. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2012, 52, 1757–1768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterling, T.; Irwin, J.J. ZINC 15--Ligand Discovery for Everyone. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2015, 55, 2324–2337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Irwin, J.J.; Tang, K.G.; Young, J.; Dandarchuluun, C.; Wong, B.R.; Khurelbaatar, M.; Moroz, Y.S.; Mayfield, J.; Sayle, R.A. ZINC20—A Free Ultralarge-Scale Chemical Database for Ligand Discovery. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2020, 60, 6065–6073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruddigkeit, L.; van Deursen, R.; Blum, L.C.; Reymond, J.L. Enumeration of 166 billion organic small molecules in the chemical universe database GDB-17. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2012, 52, 2864–2875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruddigkeit, L.; Blum, L.C.; Reymond, J.L. Visualization, and virtual screening of the chemical universe database GDB-17. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2013, 53, 56–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visini, R.; Awale, M.; Reymond, J.L. Fragment Database FDB-17. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2017, 57, 700–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xerxa, E.; Bajorath, J. Data Sets of Human and Mouse Protein Kinase Inhibitors with Curated Activity Data Including Covalent Inhibitors. Future Sci. OA 2023, 9, FSO892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koch, S.; Kullmann, E.; Bajorath, J. Opportunities for Protein Kinase Drug Discovery—2025 Update on the Chemically Underexplored Human Kinome. Eur. J. Med. Chem. Rep. 2025, 15, 100305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, H.; Laufkötter, O.; Miljković, F.; Bajorath, J. Data set of competitive and allosteric protein kinase inhibitors confirmed by X-ray crystallography. Data Brief. 2021, 35, 106816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laufkötter, O.; Hu, H.; Miljković, F.; Bajorath, J. Structure- and Similarity-Based Survey of Allosteric Kinase Inhibitors, Activators, and Closely Related Compounds. J. Med. Chem. 2022, 65, 922–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, H.; Laufkötter, O.; Miljković, F.; Bajorath, J. Systematic comparison of competitive and allosteric kinase inhibitors reveals common structural characteristics. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2021, 214, 113206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanev, G.K.; de Graaf, C.; Westerman, B.A.; de Esch, I.J.P.; Kooistra, A.J. KLIFS: An Overhaul after the First 5 Years of Supporting Kinase Research. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021, 49, D562–D569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xerxa, E.; Laufkötter, O.; Bajorath, J. Systematic Analysis of Covalent and Allosteric Protein Kinase Inhibitors. Molecules 2023, 28, 5805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bento, A.P.; Hersey, A.; Félix, E.; Landrum, G.; Gaulton, A.; Atkinson, F.; Bellis, L.J.; De Veij, M.; Leach, A.R. An open-source chemical structure curation pipeline using RDKit. J. Cheminform. 2020, 12, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruger, F.; Stiefl, N.; Landrum, G.A. rdScaffoldNetwork: The Scaffold Network Implementation in RDKit. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2020, 60, 3331–3335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abadi, M.; Agarwal, A.; Barham, P.; Brevdo, E.; Chen, Z.; Citro, C.; Corrado, G.S.; Davis, A.; Dean, J.; Devin, M.; et al. TensorFlow: A System for Large-Scale Machine Learning. In Proceedings of the 12th USENIX Symposium on Operating Systems Design and Implementation (OSDI 16), Savannah, GA, USA, 2–4 November 2016; Volume 16, pp. 265–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boulesteix, A.; Janitza, S.; Kruppa, J.; König, I. Overview of random forest methodology and practical guidance with emphasis on computational biology and bioinformatics. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Data Min. Knowl. Discov. 2012, 2, 493–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godden, J.W.; Xue, L.; Bajorath, J. Combinatorial preferences affect molecular similarity/diversity calculations using binary fingerprints and Tanimoto coefficients. J. Chem. Inf. Comput. Sci. 2000, 40, 163–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Family | Min Range | Max Range | Min Average | Max Average | Min Stand Dev | Max Stand Dev |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ABL1 | −5.89215 | 5.97272 | −1.34594 | 1.2609 | 0.78482 | 1.46389 |

| SRC | −5.89215 | 6.20087 | −1.38016 | 1.30248 | 0.86567 | 1.63218 |

| CSF1R | −5.19233 | 6.84467 | −1.19730 | 1.21217 | 0.65711 | 1.46416 |

| EGFR | −6.18875 | 6.55361 | −1.25954 | 1.22010 | 0.82409 | 1.39603 |

| FLT3 | −5.00162 | 6.45221 | −1.17921 | 1.15374 | 0.69147 | 1.42987 |

| KDR | −6.15671 | 7.05822 | −1.37088 | 1.32073 | 0.80067 | 1.35351 |

| LCK | −6.15671 | 6.62534 | −1.38279 | 1.39623 | 0.81684 | 1.55863 |

| MAPK10 | −5.08671 | 5.98541 | −1.16237 | 1.14753 | 0.68575 | 1.29511 |

| MAPK14 | −6.15671 | 6.89392 | −1.52617 | 1.44791 | 0.73652 | 1.29781 |

| MET | −6.13674 | 6.49813 | −1.45546 | 1.52347 | 0.79279 | 1.53428 |

| Precision | Recall | F1-Score | Support | |

| 0 | 0.99 | 0.98 | 0.98 | 23,530 |

| 1 | 0.71 | 0.86 | 0.78 | 1502 |

| Macro Avg | 0.85 | 0.92 | 0.88 | 25,032 |

| Weighted Avg | 0.97 | 0.97 | 0.97 | 25,032 |

| Precision | Recall | F1-Score | Support | |

| ABL1 | 0.51 | 0.58 | 0.55 | 409 |

| SRC | 0.57 | 0.56 | 0.56 | 660 |

| CSF1R | 0.69 | 0.54 | 0.61 | 142 |

| EGFR | 0.69 | 0.74 | 0.71 | 795 |

| FLT3 | 0.55 | 0.46 | 0.50 | 194 |

| KDR | 0.58 | 0.59 | 0.58 | 916 |

| LCK | 0.47 | 0.41 | 0.44 | 313 |

| MAPK10 | 0.77 | 0.55 | 0.64 | 163 |

| MAPK14 | 0.75 | 0.80 | 0.78 | 722 |

| MET | 0.74 | 0.72 | 0.73 | 421 |

| Macro Avg | 0.63 | 0.59 | 0.61 | 4735 |

| Weighted Avg | 0.63 | 0.63 | 0.63 | 4735 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Verkhivker, G.; Kassab, R.; Krishnan, K. From Latent Manifolds to Targeted Molecular Probes: An Interpretable, Kinome-Scale Generative Machine Learning Framework for Family-Based Kinase Ligand Design. Biomolecules 2026, 16, 209. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom16020209

Verkhivker G, Kassab R, Krishnan K. From Latent Manifolds to Targeted Molecular Probes: An Interpretable, Kinome-Scale Generative Machine Learning Framework for Family-Based Kinase Ligand Design. Biomolecules. 2026; 16(2):209. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom16020209

Chicago/Turabian StyleVerkhivker, Gennady, Ryan Kassab, and Keerthi Krishnan. 2026. "From Latent Manifolds to Targeted Molecular Probes: An Interpretable, Kinome-Scale Generative Machine Learning Framework for Family-Based Kinase Ligand Design" Biomolecules 16, no. 2: 209. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom16020209

APA StyleVerkhivker, G., Kassab, R., & Krishnan, K. (2026). From Latent Manifolds to Targeted Molecular Probes: An Interpretable, Kinome-Scale Generative Machine Learning Framework for Family-Based Kinase Ligand Design. Biomolecules, 16(2), 209. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom16020209