Integrative Single-Cell and Machine Learning Analysis Develops a Glutamine Metabolism–Based Prognostic Model and Identifies MSMO1 as a Therapeutic Target in Osteosarcoma

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Source

2.2. scRNA Analysis

2.3. Identification of Prognostic Genes in OS

2.4. Construction of Prognostic Model

2.5. Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA)

2.6. Immune Infiltration Analysis

2.7. Drug Sensitivity Analysis and Prediction

2.8. Pseudotime Analysis and Cell Communication

2.9. Cell Culture

2.10. Reverse Transcription-Quantitative Real-Time PCR (RT-qPCR)

2.11. Western Blot

2.12. Lentiviral Production and Transfection

2.13. CCK-8, Wound-Healing Assay, and Transwell Analysis

2.14. Annexin V-FITC/PI Stain

2.15. GS, GLS, and α-Ketoglutarate (α-KG) Assay

2.16. Statistical Analysis

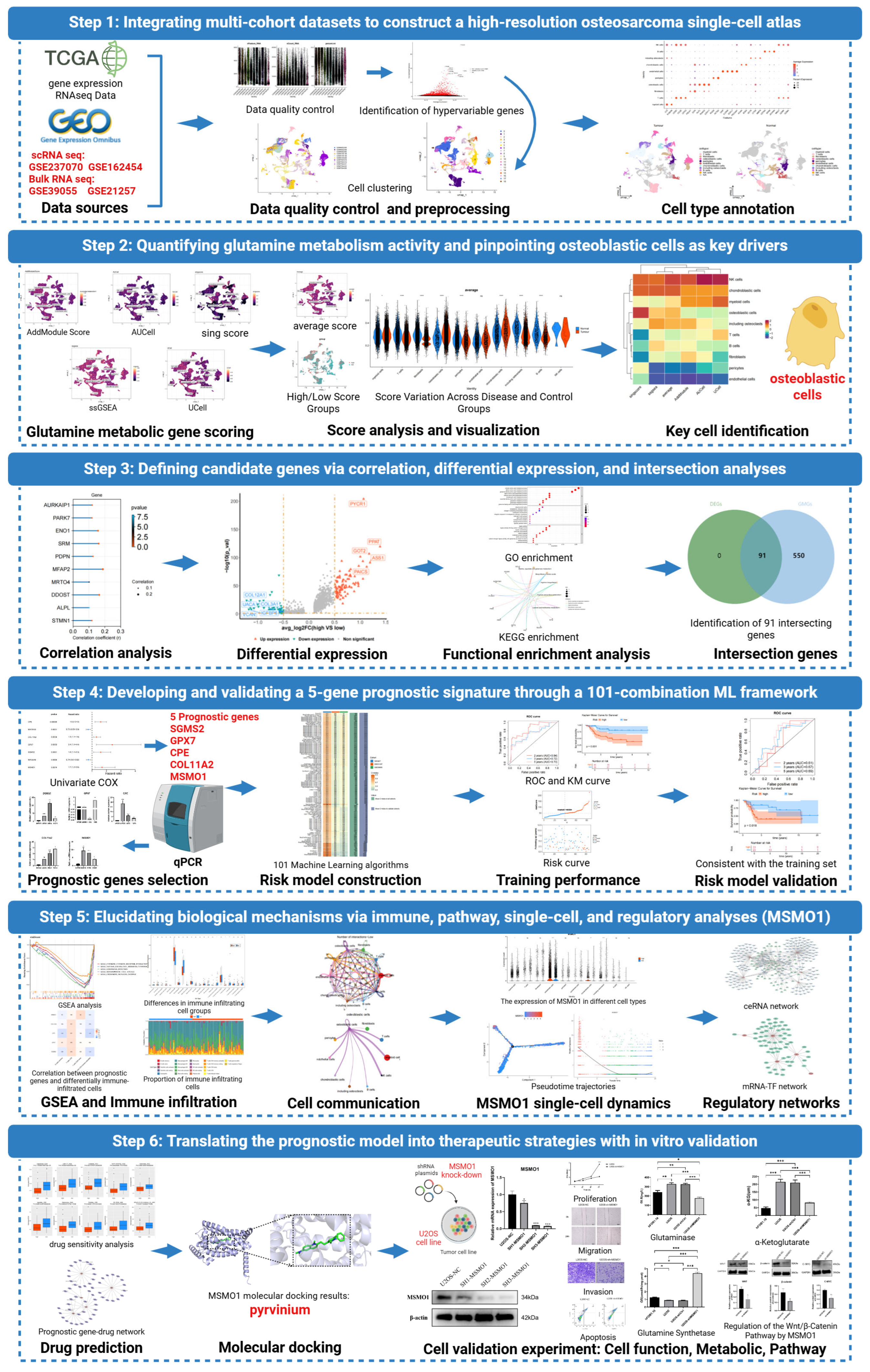

3. Results

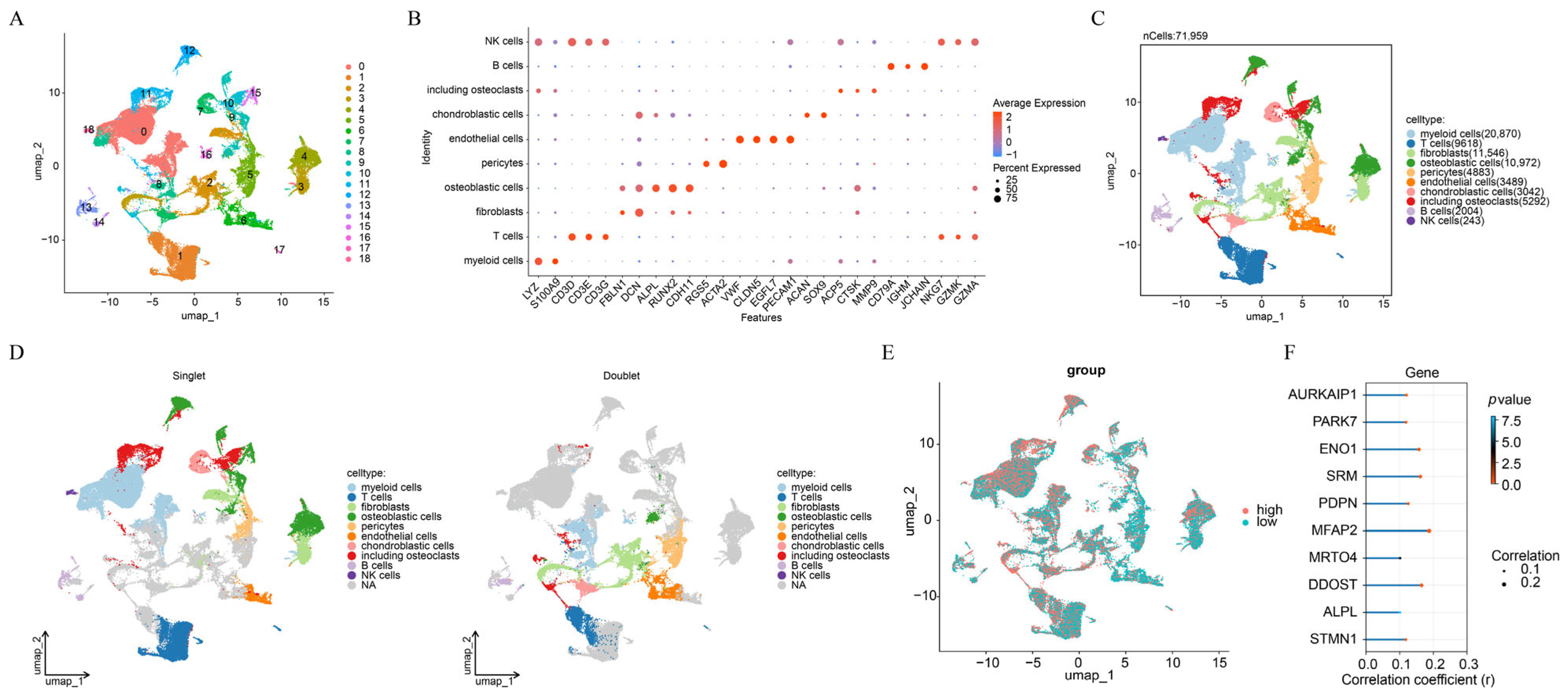

3.1. A Total of 10 Cell Types Were Annotated in OS

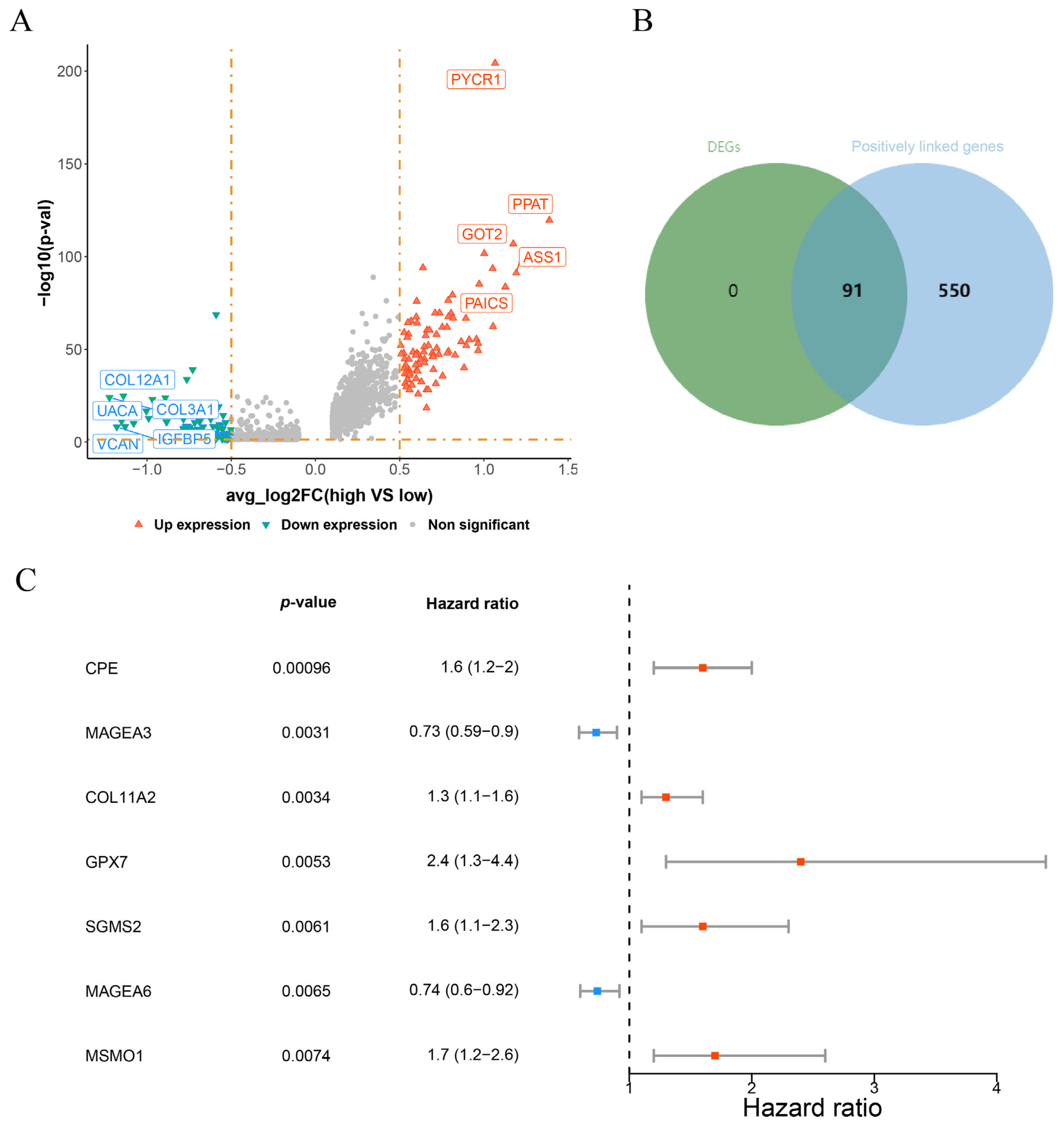

3.2. CPE, COL11A2, GPX7, SGSM2, MSMO1 Were Identified as Prognostic Genes in OS

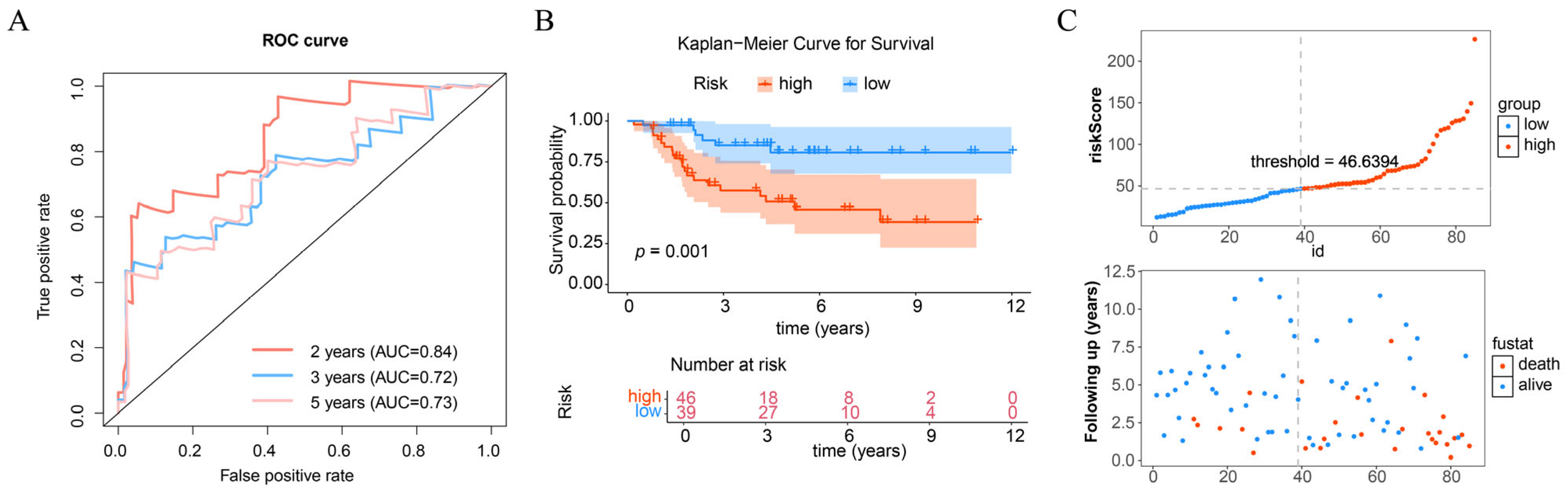

3.3. Prognostic Model Effectively Predicts the Risk of OS

3.4. The Close Correlation of Immune with OS

3.5. MSMO1 Was Identified as a Key Gene in OS

3.6. MSMO1-Mediated Regulation of the Bone Microenvironment and Potential Targeted Therapy for OS

3.7. Knock Down of MSMO1 Inhibited the Activity of U2OS Cells

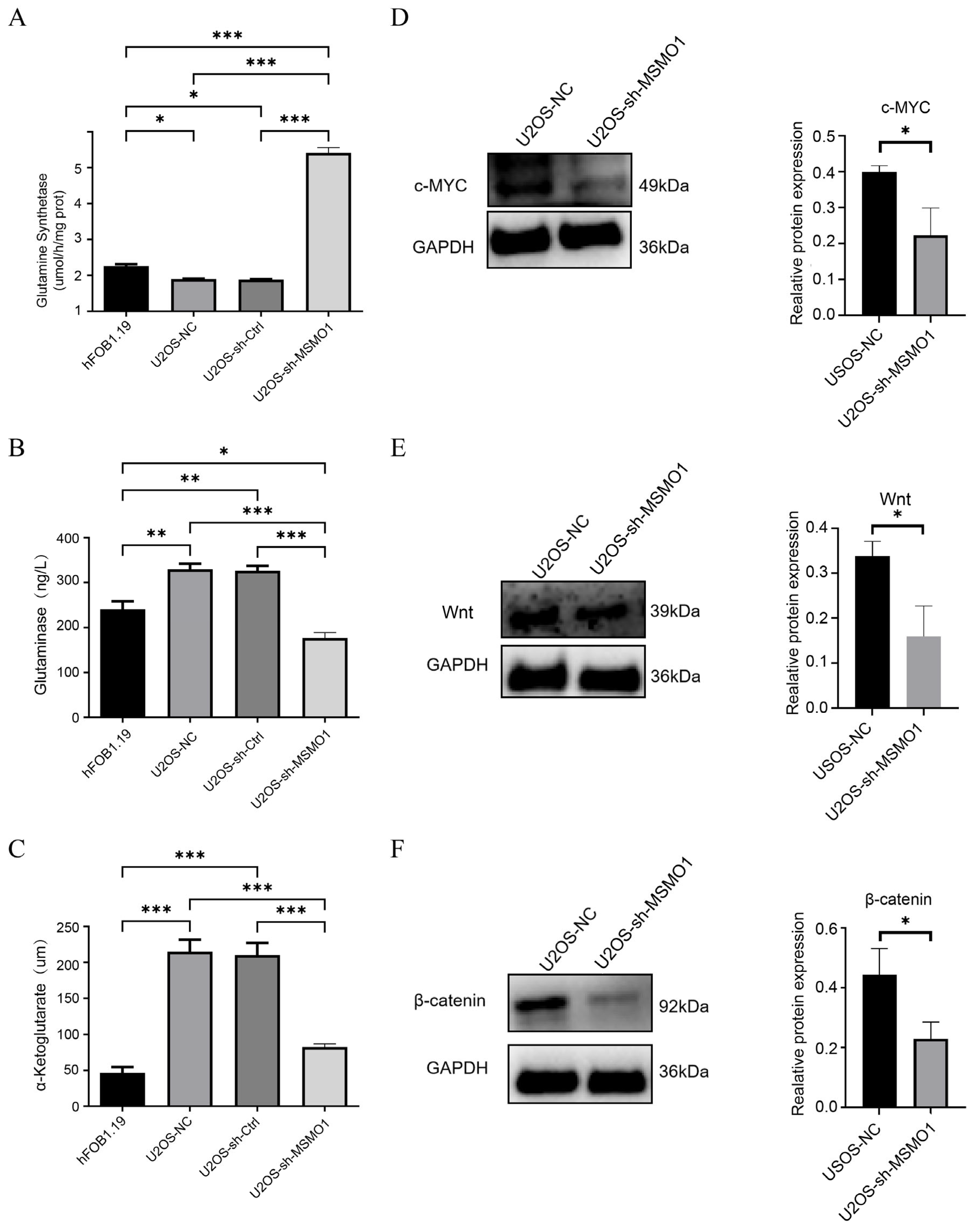

3.8. MSMO1 Regulated Glutamine Metabolism via Wnt/β-Catenin Pathway

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| OS | Osteosarcoma |

| scRNA seq | Single cell RNA sequencing |

| GS | Glutamine synthetase |

| GLS | Glutaminase |

| TME | Tumor microenvironment |

| GEO | Gene expression omnibus |

| GRGs | Glutamine metabolism-related genes |

| DEGs | Differentially expressed genes |

| KEGG | Kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes |

| GSEA | Gene set enrichment analysis |

| GDSC | Genomics of drug sensitivity in cancer |

| shRNA | short hairpin RNA |

| α-KG | α-ketoglutarate |

| MSMO1 | Methylsterol monooxygenase 1 |

| GPX7 | Glutathione peroxidase 7 |

| COL11A2 | Collagen type XI alpha 2 chain |

| CPE | Carboxypeptidase E |

| SGMS2 | Sphingomyelin synthase 2 |

| PI3K | Phosphatidylinositol-3 kinase |

| AKT | AKT serine/Threonine kinase |

| mTOR | Mechanistic target of rapamycin |

| PCs | Principal components |

| PCA | Principal component analysis |

| STRING | Search tool for the retrieval of interacting genes/proteins |

| PDB | Protein data bank |

| GAPDH | Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase |

| RIPA | Radioimmunoprecipitation assay |

| PMSF | Phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride |

| PVDF | Polyvinylidene difluoride |

| SD | Standard deviation |

References

- Rossi, M.; Del Fattore, A. Molecular and translational research on bone tumors. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 1946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skubitz, K.M.; D’Adamo, D.R. Sarcoma. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2007, 82, 1409–1432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beird, H.C.; Bielack, S.S.; Flanagan, A.M.; Gill, J.; Heymann, D.; Janeway, K.A.; Livingston, J.A.; Roberts, R.D.; Strauss, S.J.; Gorlick, R. Osteosarcoma. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2022, 8, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gill, J.; Gorlick, R. Advancing therapy for osteosarcoma. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2021, 18, 609–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, S.; Yao, X. Advances on immunotherapy for osteosarcoma. Mol. Cancer 2024, 23, 192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortés-Ciriano, I.; Lee, J.J.-K.; Xi, R.; Jain, D.; Jung, Y.L.; Yang, L.; Gordenin, D.; Klimczak, L.J.; Zhang, C.-Z.; Pellman, D.S.; et al. Comprehensive analysis of chromothripsis in 2,658 human cancers using whole-genome sequencing. Nat. Genet. 2020, 52, 331–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Espejo Valle-Inclan, J.; De Noon, S.; Trevers, K.; Elrick, H.; van Belzen, I.A.E.M.; Zumalave, S.; Sauer, C.M.; Tanguy, M.; Butters, T.; Muyas, F.; et al. Ongoing chromothripsis underpins osteosarcoma genome complexity and clonal evolution. Cell 2025, 188, 352–370.e322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finley, L.W. What is cancer metabolism? Cell 2023, 186, 1670–1688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, J.; Byun, J.-K.; Choi, Y.-K.; Park, K.-G. Targeting glutamine metabolism as a therapeutic strategy for cancer. Exp. Mol. Med. 2023, 55, 706–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Xia, K.; Wei, Z.; Liu, W.; Wei, Z.; Guo, W. SLC38A5 suppresses ferroptosis through glutamine-mediated activation of the PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling in osteosarcoma. J. Transl. Med. 2024, 22, 1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, Z.; Zou, P.; Yang, Z.; Xiong, T.; Deng, Z.; Chen, Q. Single-cell multi-omics elucidates the role of RPS27-RPS24 fusion gene in osteosarcoma chemoresistance and metabolic regulation. Cell Death Discov. 2025, 11, 197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, R.; Cooper, D.E.; Kadakia, K.T.; Allen, A.; Duan, L.; Luo, L.; Williams, N.T.; Liu, X.; Locasale, J.W.; Kirsch, D.G. Targeting glutamine metabolism improves sarcoma response to radiation therapy in vivo. Commun. Biol. 2024, 7, 608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mereu, E.; Lafzi, A.; Moutinho, C.; Ziegenhain, C.; McCarthy, D.J.; Álvarez-Varela, A.; Batlle, E.; Sagar, N.; Gruen, D.; Lau, J.K. Benchmarking single-cell RNA-sequencing protocols for cell atlas projects. Nat. Biotechnol. 2020, 38, 747–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.; Zhang, X.; Yu, L.; Zhang, G.; Liu, X.; Ren, W. Integrated immunological analysis of single-cell and bulky tissue transcriptomes reveals the role of prognostic value of T cell-related genes in cervical cancer. Comput. Methods Biomech. Biomed. Eng. 2025, 28, 1333–1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potter, S.S. Single-cell RNA sequencing for the study of development, physiology and disease. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 2018, 14, 479–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Wang, L.; Guo, H.; Zhang, W.; Shao, Z. Single-cell transcriptomics reveals the regulative roles of cancer associated fibroblasts in tumor immune microenvironment of recurrent osteosarcoma. Theranostics 2022, 12, 5877–5887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Hu, H.; Shao, Z.; Lv, X.; Zhang, Z.; Deng, X.; Song, Q.; Han, Y.; Guo, T.; Xiong, L.; et al. Characterizing the tumor microenvironment at the single-cell level reveals a novel immune evasion mechanism in osteosarcoma. Bone Res. 2023, 11, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, Y.; Guo, S.; Liao, Y.; Chen, W.; Chen, Z.; Chen, J.; Wen, L.; Xie, X. Ceramide metabolism-related prognostic signature and immunosuppressive function of ST3GAL1 in osteosarcoma. Transl. Oncol. 2024, 40, 101840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, X.; Liu, Y.; Xu, J.; Zhu, J.; Zheng, Y.; Qi, Q. A novel hypoxia-and lactate metabolism-related prognostic signature to characterize the immune landscape and predict immunotherapy response in osteosarcoma. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1467052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hao, Y.; Hao, S.; Andersen-Nissen, E.; Mauck, W.M., 3rd; Zheng, S.; Butler, A.; Lee, M.J.; Wilk, A.J.; Darby, C.; Zager, M.; et al. Integrated analysis of multimodal single-cell data. Cell 2021, 184, 3573–3587.e3529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; He, M.; Tang, H.; Xie, T.; Lin, Y.; Liu, S.; Liang, J.; Li, F.; Luo, K.; Yang, M.; et al. Single-cell and spatial transcriptomics reveal metastasis mechanism and microenvironment remodeling of lymph node in osteosarcoma. BMC Med. 2024, 22, 200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, S.; Luo, M.; Huang, H.; Huang, X.; Peng, Z.; Zheng, S.; Tan, J. New insights into the role of mitophagy related gene affecting the metastasis of osteosarcoma through scRNA-seq and CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing. Cell Commun. Signal. 2024, 22, 592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGinnis, C.S.; Murrow, L.M.; Gartner, Z.J. DoubletFinder: Doublet Detection in Single-Cell RNA Sequencing Data Using Artificial Nearest Neighbors. Cell Syst. 2019, 8, 329–337.e324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Qi, H.; Jiang, L.; Sun, S.; Zhang, J.; Yu, J.; Liu, F.; Zhang, Y.; Du, S. Integrating single-cell RNA-Seq and machine learning to dissect tryptophan metabolism in ulcerative colitis. J. Transl. Med. 2024, 22, 1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Li, H.; Zeng, T.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Wan, Y.; Shi, Z.; Cao, R.; Tang, H. Integrated bulk and single-cell transcriptomes reveal pyroptotic signature in prognosis and therapeutic options of hepatocellular carcinoma by combining deep learning. Brief. Bioinform. 2024, 25, bbad487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreatta, M.; Carmona, S.J. UCell: Robust and scalable single-cell gene signature scoring. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 2021, 19, 3796–3798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mao, Y.; Gide, T.N.; Adegoke, N.A.; Quek, C.; Maher, N.; Potter, A.; Patrick, E.; Saw, R.P.M.; Thompson, J.F.; Spillane, A.J.; et al. Cross-platform comparison of immune signatures in immunotherapy-treated patients with advanced melanoma using a rank-based scoring approach. J. Transl. Med. 2023, 21, 257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, Y.; Wang, Z.; He, D.; Zhu, Y.; Chen, X.; Cao, K. Identification of novel subtypes based on ssGSEA in immune-related prognostic signature for tongue squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Med. 2021, 10, 8693–8707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, Y.; Li, M.; Wen, J.; Kong, X.; Li, J. Single-cell characteristics and malignancy regulation of alpha-fetoprotein-producing gastric cancer. Cancer Med. 2023, 12, 12018–12033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, M.; Li, M.; Zhang, Y.; Gu, X.; Gao, W.; Zhang, S.; Liu, J. Exploring the mechanism of PPCPs on human metabolic diseases based on network toxicology and molecular docking. Environ. Int. 2025, 196, 109324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spytek, M.; Krzyziński, M.; Langbein, S.H.; Baniecki, H.; Wright, M.N.; Biecek, P. survex: An R package for explaining machine learning survival models. Bioinformatics 2023, 39, btad723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, H.; Yuan, X.; Liu, G.; Fan, W. Identifying and Validating GSTM5 as an Immunogenic Gene in Diabetic Foot Ulcer Using Bioinformatics and Machine Learning. J. Inflamm. Res. 2023, 16, 6241–6256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, J.; Wu, L.; Zheng, M.; Pan, F. Exploring Programmed Cell Death-Related Biomarkers and Disease Therapy Strategy in Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma Using Transcriptomics. Front. Biosci. 2024, 29, 240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Wang, Y.; Dong, H.; Niu, K.; Zhang, W.; Feng, K.; Yang, R.; Zhang, Y. Crosstalk of ferroptosis regulators and tumor immunity in pancreatic adenocarcinoma: Novel perspective to mRNA vaccines and personalized immunotherapy. Apoptosis 2023, 28, 1423–1435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robles-Jimenez, L.E.; Aranda-Aguirre, E.; Castelan-Ortega, O.A.; Shettino-Bermudez, B.S.; Ortiz-Salinas, R.; Miranda, M.; Li, X.; Angeles-Hernandez, J.C.; Vargas-Bello-Pérez, E.; Gonzalez-Ronquillo, M. Worldwide Traceability of Antibiotic Residues from Livestock in Wastewater and Soil: A Systematic Review. Animals 2022, 12, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.; Hu, E.; Xu, S.; Chen, M.; Guo, P.; Dai, Z.; Feng, T.; Zhou, L.; Tang, W.; Zhan, L.; et al. clusterProfiler 4.0: A universal enrichment tool for interpreting omics data. Innovation 2021, 2, 100141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, A.M.; Liu, C.L.; Green, M.R.; Gentles, A.J.; Feng, W.; Xu, Y.; Hoang, C.D.; Diehn, M.; Alizadeh, A.A. Robust enumeration of cell subsets from tissue expression profiles. Nat. Methods 2015, 12, 453–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butcher, S.J.; Manole, V.; Karhu, N.J. Lipid-containing viruses: Bacteriophage PRD1 assembly. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2012, 726, 365–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Chao, P.; Zhang, L.; Xu, L.; Cui, X.; Wang, S.; Wusiman, M.; Jiang, H.; Lu, C. Single-cell RNA and transcriptome sequencing profiles identify immune-associated key genes in the development of diabetic kidney disease. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1030198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Li, W.; Ji, W.; Bing, D.; Liu, M.; Liu, K.; Chen, B.; Zhao, Z.; Gu, Y.; Li, X.; et al. GTSE1-expressed osteoblastic cells facilitate formation of pro-metastatic tumor microenvironment in osteosarcoma. Genes Dis. 2025, 12, 101591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rubio, R.; Gutierrez-Aranda, I.; Sáez-Castillo, A.I.; Labarga, A.; Rosu-Myles, M.; Gonzalez-Garcia, S.; Toribio, M.L.; Menendez, P.; Rodriguez, R. The differentiation stage of p53-Rb-deficient bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells imposes the phenotype of in vivo sarcoma development. Oncogene 2013, 32, 4970–4980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutsaers, A.J.; Walkley, C.R. Cells of origin in osteosarcoma: Mesenchymal stem cells or osteoblast committed cells? Bone 2014, 62, 56–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roessner, A.; Lohmann, C.; Jechorek, D. Translational cell biology of highly malignant osteosarcoma. Pathol. Int. 2021, 71, 291–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Duan, J.J.; Guo, Y.F.; Chen, J.J.; Chen, T.Q.; Wang, J.; Yu, S.C. Targeting the glutamine-arginine-proline metabolism axis in cancer. J. Enzym. Inhib Med. Chem. 2024, 39, 2367129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Cao, Y.; Gou, Y.; Wang, H.; Liang, Z.; Wu, Q.; Tan, J.; Liu, J.; Li, Z.; Cui, J.; et al. IGF2BP3 promotes glutamine metabolism of endometriosis by interacting with UCA1 to enhances the mRNA stability of GLS1. Mol. Med. 2024, 30, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meltzer, P.S.; Helman, L.J. New Horizons in the Treatment of Osteosarcoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 385, 2066–2076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, D.; Wan, B.; Cheng, Y.; Luo, Y.; Bai, X.; Guo, J.; Li, G.; Jin, T.; Nie, J.; Liu, W. Carboxypeptidase E is a prognostic biomarker co-expressed with osteoblastic genes in osteosarcoma. PeerJ 2023, 11, e15814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Lacerda, D.A.; Warman, M.L.; Beier, D.R.; Yoshioka, H.; Ninomiya, Y.; Oxford, J.T.; Morris, N.P.; Andrikopoulos, K.; Ramirez, F.; et al. A fibrillar collagen gene, Col11a1, is essential for skeletal morphogenesis. Cell 1995, 80, 423–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, D.; Liu, Z.; Deng, N.; Tan, T.Z.; Huang, R.Y.-J.; Taylor-Harding, B.; Cheon, D.-J.; Lawrenson, K.; Wiedemeyer, W.R.; Walts, A.E.; et al. A COL11A1-correlated pan-cancer gene signature of activated fibroblasts for the prioritization of therapeutic targets. Cancer Lett. 2016, 382, 203–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.I.; Wei, P.C.; Hsu, J.L.; Su, F.Y.; Lee, W.H. NPGPx (GPx7): A novel oxidative stress sensor/transmitter with multiple roles in redox homeostasis. Am. J. Transl. Res. 2016, 8, 1626–1640. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Cao, Y. The sphingomyelin synthase family: Proteins, diseases, and inhibitors. Biol. Chem. 2017, 398, 1319–1325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, K.; Chen, Z.; Feng, H.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, C.; Yu, J.; Luo, Y.; Zhao, L.; Jiang, X.; Shi, F. Sphingomyelin synthase 2 promotes an aggressive breast cancer phenotype by disrupting the homoeostasis of ceramide and sphingomyelin. Cell Death Dis. 2019, 10, 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pekkinen, M.; Terhal, P.A.; Botto, L.D.; Henning, P.; Mäkitie, R.E.; Roschger, P.; Jain, A.; Kol, M.; Kjellberg, M.A.; Paschalis, E.P.; et al. Osteoporosis and skeletal dysplasia caused by pathogenic variants in SGMS2. JCI Insight 2019, 4, e126180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simigdala, N.; Gao, Q.; Pancholi, S.; Roberg-Larsen, H.; Zvelebil, M.; Ribas, R.; Folkerd, E.; Thompson, A.; Bhamra, A.; Dowsett, M.; et al. Cholesterol biosynthesis pathway as a novel mechanism of resistance to estrogen deprivation in estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. 2016, 18, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, R.; Zhang, Z.; Tian, C.; Sheng, W.; Dong, Q.; Dong, M. Down-regulation of MSMO1 promotes the development and progression of pancreatic cancer. J. Cancer 2022, 13, 3013–3021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kodama, M.; Oshikawa, K.; Shimizu, H.; Yoshioka, S.; Takahashi, M.; Izumi, Y.; Bamba, T.; Tateishi, C.; Tomonaga, T.; Matsumoto, M.; et al. A shift in glutamine nitrogen metabolism contributes to the malignant progression of cancer. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lourenco, C.; Resetca, D.; Redel, C.; Lin, P.; MacDonald, A.S.; Ciaccio, R.; Kenney, T.M.; Wei, Y.; Andrews, D.W.; Sunnerhagen, M. MYC protein interactors in gene transcription and cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2021, 21, 579–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leone, R.D.; Zhao, L.; Englert, J.M.; Sun, I.M.; Oh, M.H.; Sun, I.H.; Arwood, M.L.; Bettencourt, I.A.; Patel, C.H.; Wen, J.; et al. Glutamine blockade induces divergent metabolic programs to overcome tumor immune evasion. Science 2019, 366, 1013–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, S.; Ming, Y.; Wu, J.; Cui, G. Cellular metabolism regulates the differentiation and function of T-cell subsets. Cell. Mol. Immunol. 2024, 21, 419–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, L.; Ruiz-Rodado, V.; Dowdy, T.; Huang, S.; Issaq, S.H.; Beck, J.; Wang, H.; Tran Hoang, C.; Lita, A.; Larion, M.; et al. Glutaminase-1 (GLS1) inhibition limits metastatic progression in osteosarcoma. Cancer Metab. 2020, 8, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, A.R.; Rathmell, W.K.; Rathmell, J.C. The tumor microenvironment as a metabolic barrier to effector T cells and immunotherapy. eLife 2020, 9, e55185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bröer, A.; Gauthier-Coles, G.; Rahimi, F.; van Geldermalsen, M.; Dorsch, D.; Wegener, A.; Holst, J.; Bröer, S. Ablation of the ASCT2 (SLC1A5) gene encoding a neutral amino acid transporter reveals transporter plasticity and redundancy in cancer cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2019, 294, 4012–4026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cormerais, Y.; Massard, P.A.; Vucetic, M.; Giuliano, S.; Tambutté, E.; Durivault, J.; Vial, V.; Endou, H.; Wempe, M.F.; Parks, S.K.; et al. The glutamine transporter ASCT2 (SLC1A5) promotes tumor growth independently of the amino acid transporter LAT1 (SLC7A5). J. Biol. Chem. 2018, 293, 2877–2887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stefani, S.; Thomas, F.G. A new paradigm for tumor immune escape: β-catenin-driven immune exclusion. J. Immunother. Cancer 2015, 3, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Tang, F.; Zhang, J.; He, M.; Xie, T.; Tang, H.; Liu, J.; Luo, K.; Lu, S.; Liu, Y.; et al. High GNG4 predicts adverse prognosis for osteosarcoma: Bioinformatics prediction and experimental verification. Front. Oncol. 2023, 13, 991483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strauss, S.J.; Frezza, A.M.; Abecassis, N.; Bajpai, J.; Bauer, S.; Biagini, R.; Bielack, S.; Blay, J.Y.; Bolle, S.; Bonvalot, S.; et al. Bone sarcomas: ESMO-EURACAN-GENTURIS-ERN PaedCan Clinical Practice Guideline for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann. Oncol. 2021, 32, 1520–1536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, D.; Zhang, Z.; Mi, Z.; Tao, W.; Liu, D.; Fu, J.; Fan, H. Deciphering the heterogeneity and immunosuppressive function of regulatory T cells in osteosarcoma using single-cell RNA transcriptome. Comput. Biol. Med. 2023, 165, 107417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Wang, T.; Gong, H.; Jiang, R.; Zhou, W.; Sun, H.; Huang, R.; Wang, Y.; Wu, Z.; Xu, W.; et al. A novel molecular classification method for osteosarcoma based on tumor cell differentiation trajectories. Bone Res. 2023, 11, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truong, D.D.; Weistuch, C.; Murgas, K.A.; Admane, P.; King, B.L.; Chauviere Lee, J.; Lamhamedi-Cherradi, S.-E.; Swaminathan, J.; Daw, N.C.; Gordon, N. Mapping the single-cell differentiation landscape of osteosarcoma. Clin. Cancer Res. 2024, 30, 3259–3272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Z.; Li, W.; Zhang, D.; Zhang, C.; Jiang, X.; Guo, R.; Wang, Z.; Yang, C.; Yan, H.; Zhang, Z.; et al. Development of a Chemoresistant Risk Scoring Model for Prechemotherapy Osteosarcoma Using Single-Cell Sequencing. Front. Oncol. 2022, 12, 893282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tannir, N.M.; Agarwal, N.; Porta, C.; Lawrence, N.J.; Motzer, R.; McGregor, B.; Lee, R.J.; Jain, R.K.; Davis, N.; Appleman, L.J.; et al. Efficacy and Safety of Telaglenastat Plus Cabozantinib vs Placebo Plus Cabozantinib in Patients With Advanced Renal Cell Carcinoma: The CANTATA Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Oncol. 2022, 8, 1411–1418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Use in Study | Accession | Source | Samples Size (n) | Note |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Training set | TARGET-OS | UCSC Xena | 84 | Overall survival time/status, age, sex, et al. |

| Validation set | GSE39055 | GEO | 37 | 37 surgical resection specimens |

| GSE21257 | GEO | 53 | 34 metastatic/19 non-metastatic | |

| Sc RNA seq | GSE237070 | GEO | 5 | 2 OS and 3 control samples |

| GSE162454 | GEO | 6 | 6 OS samples | |

| GRG set | GRGs | MSigDB | 80 genes | glutamine metabolism-related genes |

| ID | p Value |

|---|---|

| CPE | 0.222603810060145 |

| MAGEA3 | 0.559377399103922 |

| COL11A2 | 0.0860725731817447 |

| GPX7 | 0.510907341076549 |

| SGMS2 | 0.47011708773789 |

| MAGEA6 | 0.470480197168624 |

| MSMO1 | 0.269433637199621 |

| Gene | PDB | Chemical Name | kcal/mol |

|---|---|---|---|

| MSMO1 | Q15800 | pyrvinium | −10.7 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ma, H.; Zhang, H.; Bajgai, J.; Rahman, M.H.; Pham, T.T.; Mo, C.; Cao, B.; Choi, Y.-e.; Kim, C.-S.; Lee, K.-J. Integrative Single-Cell and Machine Learning Analysis Develops a Glutamine Metabolism–Based Prognostic Model and Identifies MSMO1 as a Therapeutic Target in Osteosarcoma. Biomolecules 2025, 15, 1664. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom15121664

Ma H, Zhang H, Bajgai J, Rahman MH, Pham TT, Mo C, Cao B, Choi Y-e, Kim C-S, Lee K-J. Integrative Single-Cell and Machine Learning Analysis Develops a Glutamine Metabolism–Based Prognostic Model and Identifies MSMO1 as a Therapeutic Target in Osteosarcoma. Biomolecules. 2025; 15(12):1664. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom15121664

Chicago/Turabian StyleMa, Hui, Haiyang Zhang, Johny Bajgai, Md. Habibur Rahman, Thu Thao Pham, Chaodeng Mo, Buchan Cao, Yeong-eun Choi, Cheol-Su Kim, and Kyu-Jae Lee. 2025. "Integrative Single-Cell and Machine Learning Analysis Develops a Glutamine Metabolism–Based Prognostic Model and Identifies MSMO1 as a Therapeutic Target in Osteosarcoma" Biomolecules 15, no. 12: 1664. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom15121664

APA StyleMa, H., Zhang, H., Bajgai, J., Rahman, M. H., Pham, T. T., Mo, C., Cao, B., Choi, Y.-e., Kim, C.-S., & Lee, K.-J. (2025). Integrative Single-Cell and Machine Learning Analysis Develops a Glutamine Metabolism–Based Prognostic Model and Identifies MSMO1 as a Therapeutic Target in Osteosarcoma. Biomolecules, 15(12), 1664. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom15121664