Melatonin Administration Attenuates High-Fat-Diet-Induced Renal Damage in Wistar Rats

Abstract

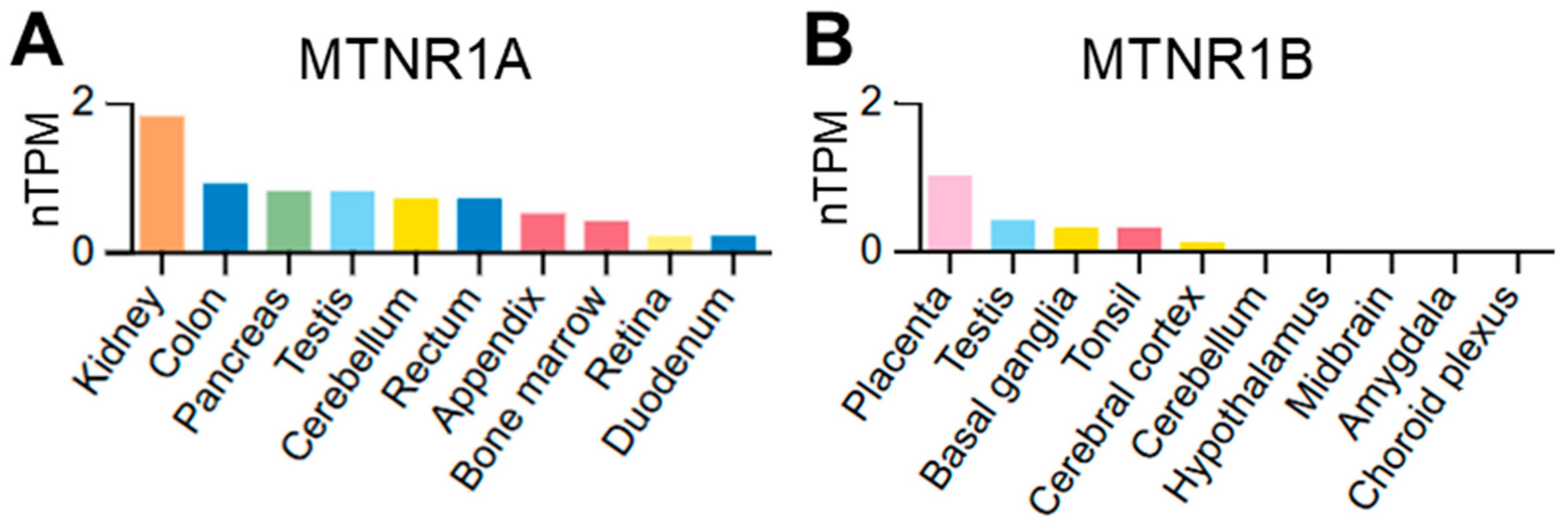

1. Introduction

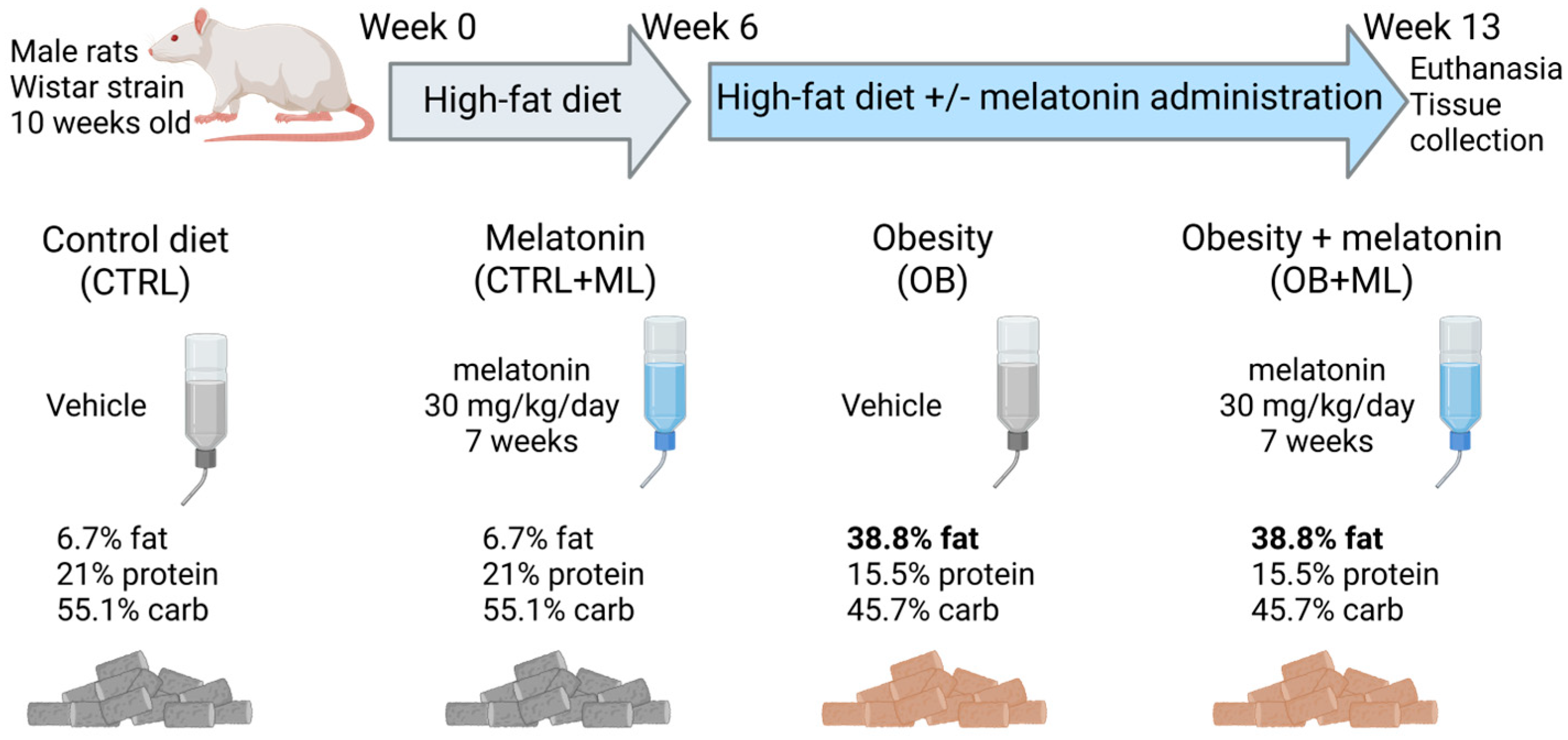

2. Materials and Methods

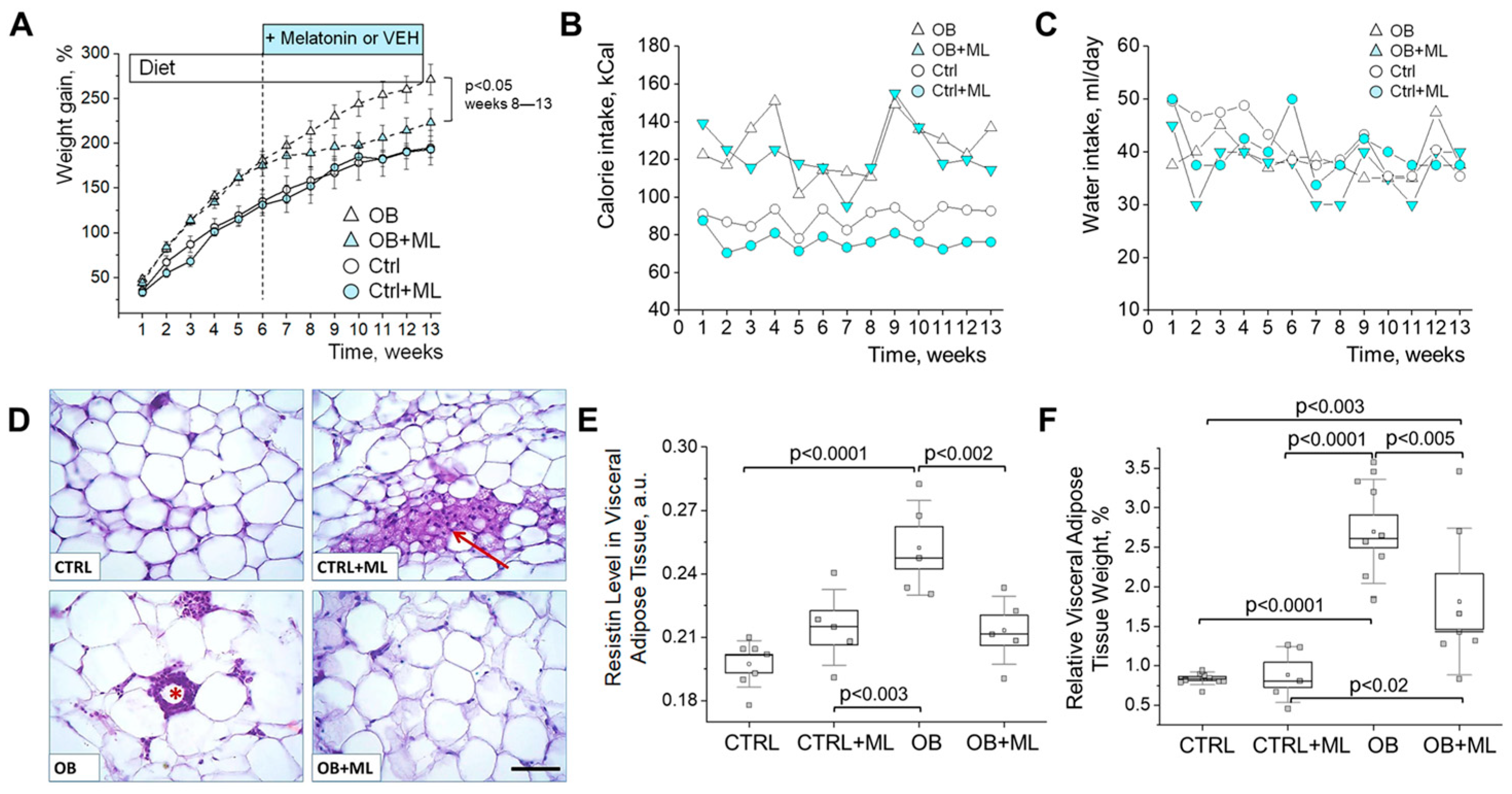

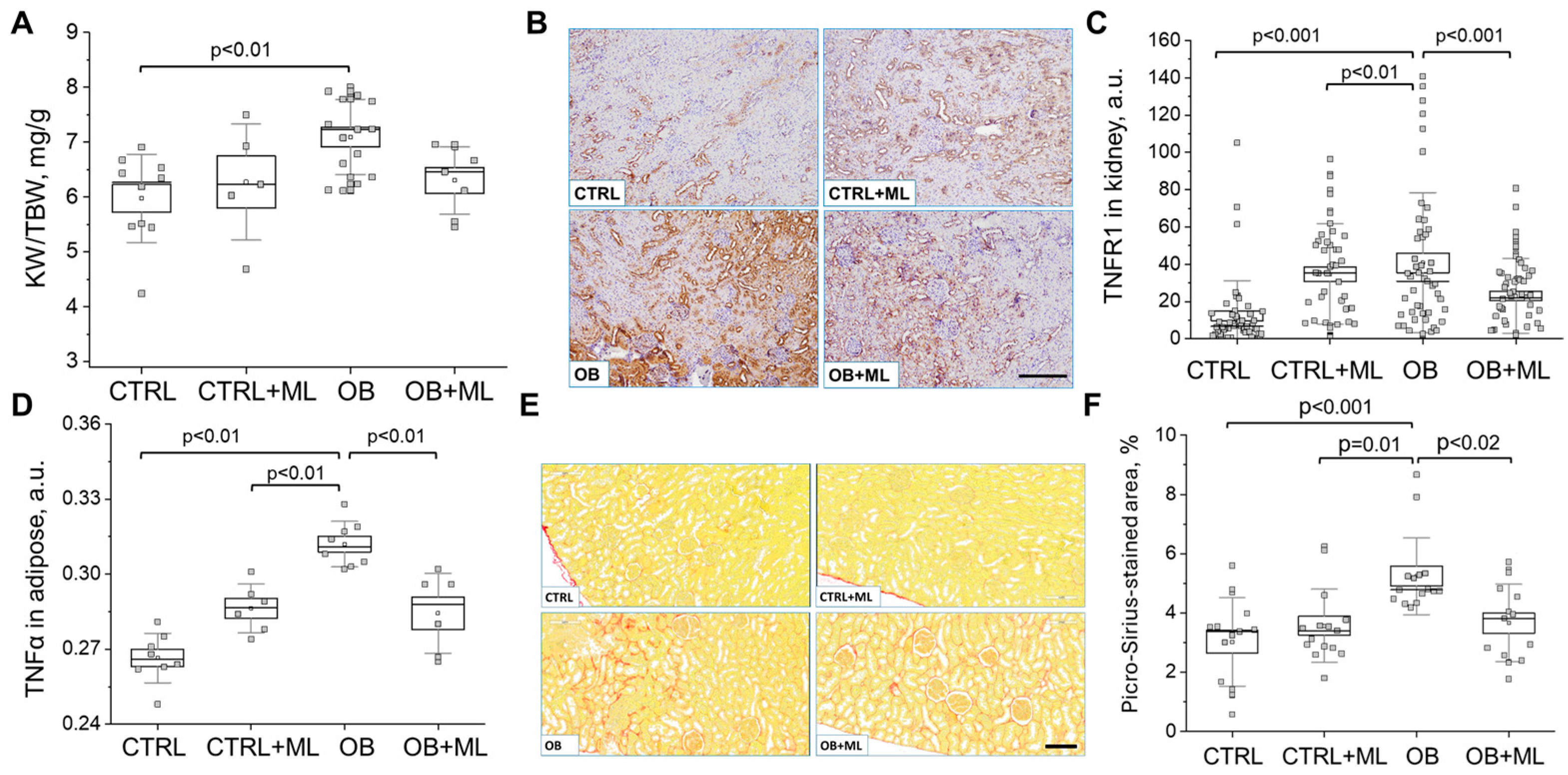

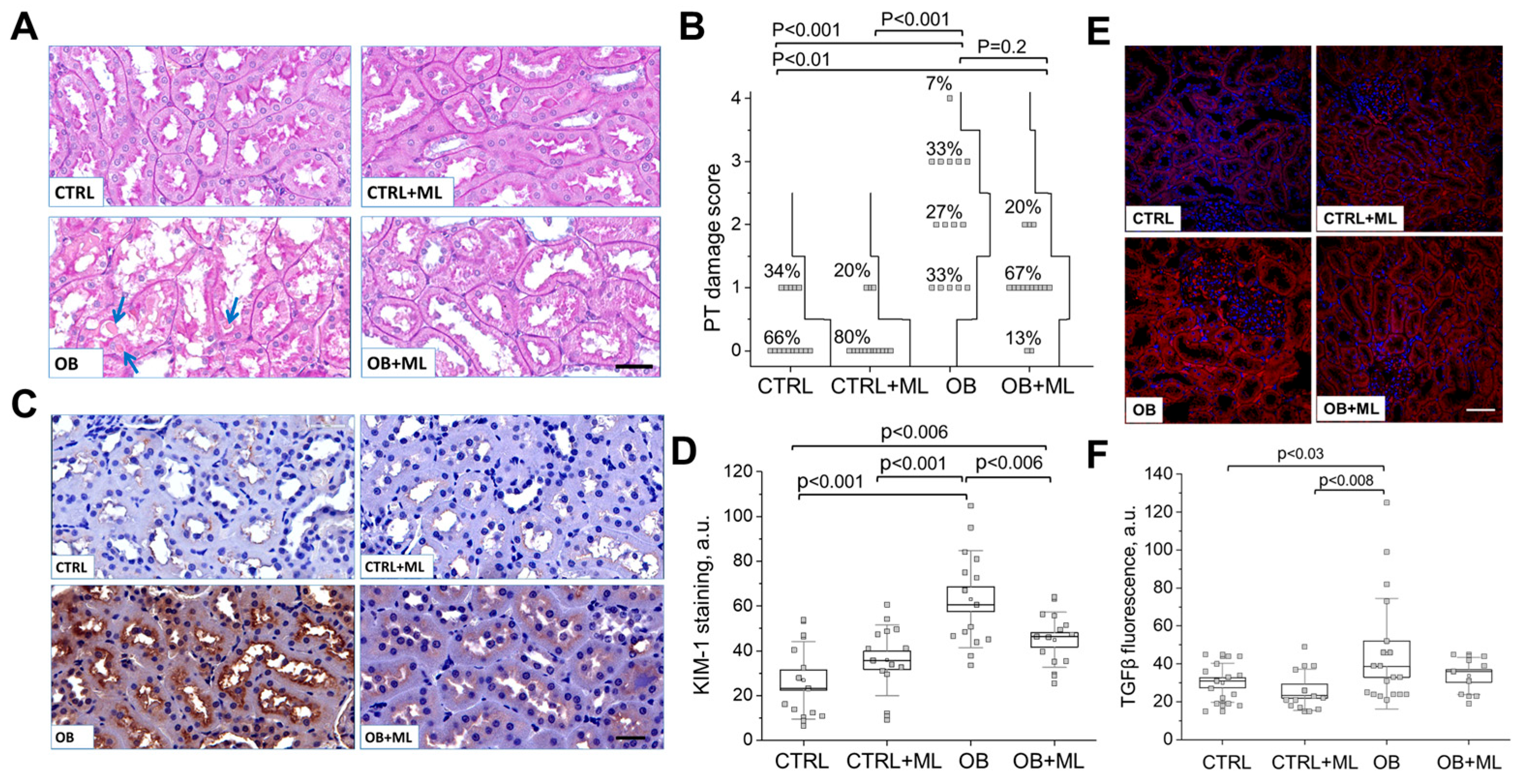

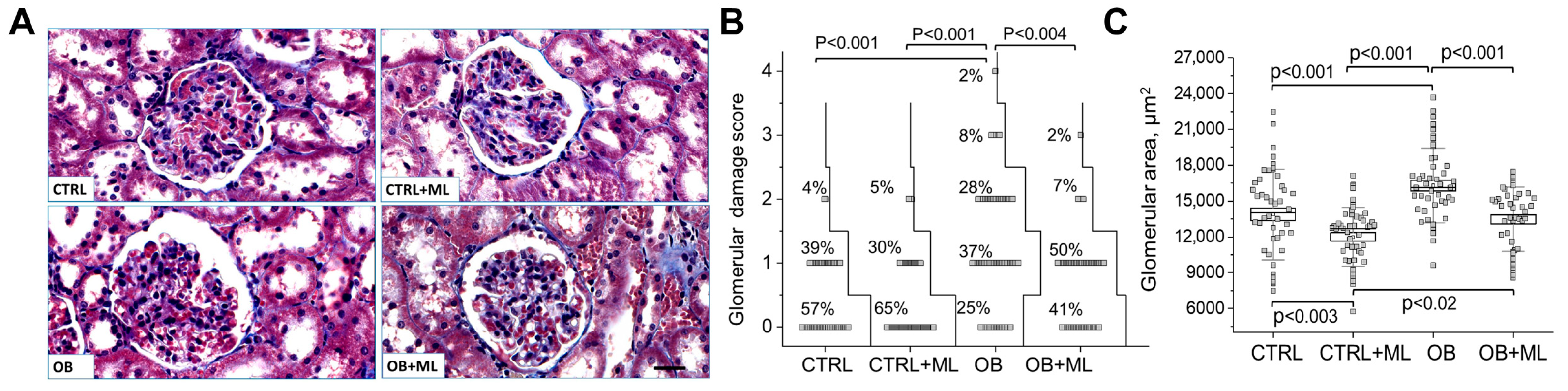

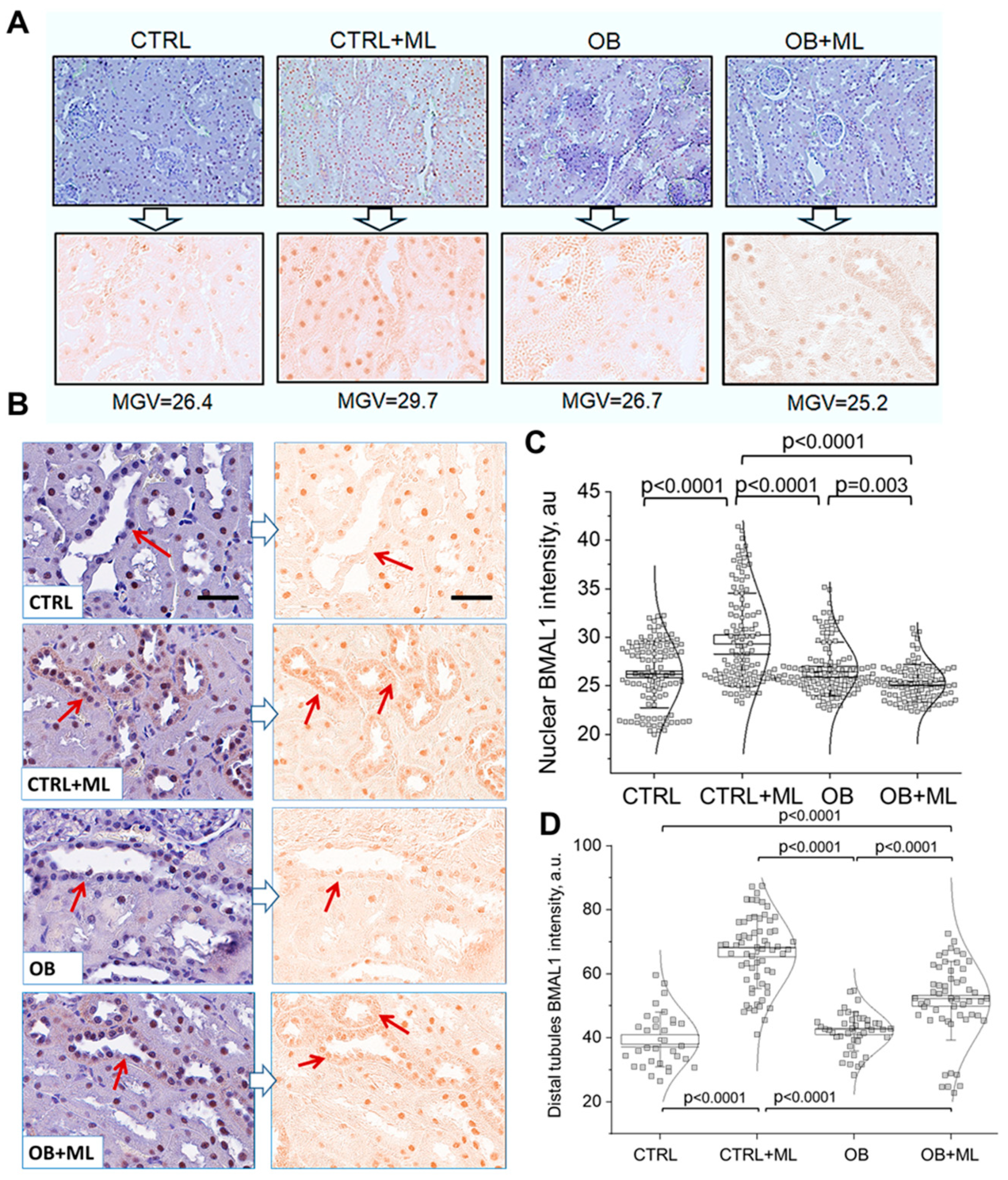

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| IDO | indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase |

| AKI | acute kidney injury |

| SCN | suprachiasmatic nucleus |

| MT1 | melatonin receptor 1 |

| MT2 | melatonin receptor 2 |

References

- Karamitri, A.; Jockers, R. Melatonin in type 2 diabetes mellitus and obesity. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2019, 15, 105–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zagajewski, J.; Wojcik-Grzybek, D.; Brzozowski, B.; Majka, J.; Magierowski, M.; Placha, W.; Lasota, M.; Laidler, P.M.; Brzozowski, T. Simultaneous detection of melatonin and six metabolites of L-tryptophan pathway in rat gastric mucosa. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 2021, 72, 987–998. [Google Scholar]

- Zakrocka, I.; Zaluska, W. Kynurenine pathway in kidney diseases. Pharmacol. Rep. 2022, 74, 27–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wee, H.N.; Liu, J.J.; Ching, J.; Kovalik, J.P.; Lim, S.C. The Kynurenine Pathway in Acute Kidney Injury and Chronic Kidney Disease. Am. J. Nephrol. 2021, 52, 771–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saliba, A.; Debnath, S.; Tamayo, I.; Lee, H.J.; Ragi, N.; Das, F.; Montellano, R.; Tumova, J.; Maddox, M.; Trevino, E.; et al. Quinolinic acid potentially links kidney injury to brain toxicity. JCI Insight 2025, 10, e180229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.; Liu, J.; Li, H.; Yan, Y. Melatonin attenuates ischemia-reperfusion-induced acute kidney injury by regulating abnormal autophagy and pyroptosis through SIRT1-mediated p53 deacetylation. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2025, 162, 115092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Yang, J.; Liu, G. Melatonin Protects Against Diabetic Kidney Disease via the SIRT1/NLRP3 Signalling Pathway. Nephrology 2025, 30, e70073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusirisin, P.; Apaijai, N.; Noppakun, K.; Kuanprasert, S.; Chattipakorn, S.C.; Chattipakorn, N. Protective Effects of Melatonin on Kidney Function Against Contrast Media-Induced Kidney Damage in Patients with Chronic Kidney Disease: A Prospective, Randomized, Double-Blinded, Placebo-Controlled Trial. J. Pineal Res. 2025, 77, e70031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bryan, S.; Afful, J.; Carroll, M.; Te-Ching, C.; Orlando, D.; Fink, S.; Fryar, C. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2017-March 2020 Prepandemic Data Files-Development of Files and Prevalence Estimates for Selected Health Outcomes. Natl. Health Stat. Rep. 2021, 158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powell-Wiley, T.M.; Poirier, P.; Burke, L.E.; Despres, J.P.; Gordon-Larsen, P.; Lavie, C.J.; Lear, S.A.; Ndumele, C.E.; Neeland, I.J.; Sanders, P.; et al. Obesity and Cardiovascular Disease: A Scientific Statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2021, 143, e984–e1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gumz, M.L.; Shimbo, D.; Abdalla, M.; Balijepalli, R.C.; Benedict, C.; Chen, Y.; Earnest, D.J.; Gamble, K.L.; Garrison, S.R.; Gong, M.C.; et al. Toward Precision Medicine: Circadian Rhythm of Blood Pressure and Chronotherapy for Hypertension—2021 NHLBI Workshop Report. Hypertension 2023, 80, 503–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benjamin, J.I.; Pollock, D.M. Current perspective on circadian function of the kidney. Am. J. Physiol.-Ren. Physiol. 2024, 326, F438–F459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Begemann, K.; Rawashdeh, O.; Olejniczak, I.; Pilorz, V.; de Assis, L.V.M.; Osorio-Mendoza, J.; Oster, H. Endocrine regulation of circadian rhythms. npj Biol. Timing Sleep 2025, 2, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, S.B.; Ali, A.; Bilal, M.; Rashid, S.M.; Wani, A.B.; Bhat, R.R.; Rehman, M.U. Melatonin and Health: Insights of Melatonin Action, Biological Functions, and Associated Disorders. Cell Mol. Neurobiol. 2023, 43, 2437–2458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Li, D.; Li, H.; Zhang, O.; Huang, Y.; Shao, H.; Wang, Y.; Cai, S.; Zhu, Y.; Jin, S.; et al. Suppression of obesity by melatonin through increasing energy expenditure and accelerating lipolysis in mice fed a high-fat diet. Nutr. Diabetes 2022, 12, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mendes, L.; Queiroz, M.; Sena, C.M. Melatonin and Vascular Function. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunt, A.E.; Al-Ghoul, W.M.; Gillette, M.U.; Dubocovich, M.L. Activation of MT(2) melatonin receptors in rat suprachiasmatic nucleus phase advances the circadian clock. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2001, 280, C110-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pevet, P.; Challet, E. Melatonin: Both master clock output and internal time-giver in the circadian clocks network. J. Physiol. Paris. 2011, 105, 170–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardeland, R. Chronobiology of Melatonin beyond the Feedback to the Suprachiasmatic Nucleus—Consequences to Melatonin Dysfunction. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2013, 14, 5817–5841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abedini, A.; Sanchez-Navaro, A.; Wu, J.; Klotzer, K.A.; Ma, Z.; Poudel, B.; Doke, T.; Balzer, M.S.; Frederick, J.; Cernecka, H.; et al. Single-cell transcriptomics and chromatin accessibility profiling elucidate the kidney-protective mechanism of mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists. J. Clin. Investig. 2024, 134, e157165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tiwari, R.; Kravtsova, O.; Dissanayake, L.V.; Lowe, M.; Xu, B.; Levchenko, V.; Didik, S.; Bohovyk, R.; Ilatovskaya, D.V.; Palygin, O.; et al. Longitudinal Multi-Organ Transcriptomic Atlas of Salt-Induced Hypertension. bioRxiv 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beker, M.C.; Caglayan, B.; Caglayan, A.B.; Kelestemur, T.; Yalcin, E.; Caglayan, A.; Kilic, U.; Baykal, A.T.; Reiter, R.J.; Kilic, E. Interaction of melatonin and Bmal1 in the regulation of PI3K/AKT pathway components and cellular survival. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 19082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schrader, L.A.; Ronnekleiv-Kelly, S.M.; Hogenesch, J.B.; Bradfield, C.A.; Malecki, K.M. Circadian disruption, clock genes, and metabolic health. J. Clin. Investig. 2024, 134, e170998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaikin, C.A.; Thakkar, A.V.; Steffeck, A.W.T.; Pfrender, E.M.; Hung, K.; Zhu, P.; Waldeck, N.J.; Nozawa, R.; Song, W.; Futtner, C.R.; et al. Control of circadian muscle glucose metabolism through the BMAL1-HIF axis in obesity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2025, 122, e2424046122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jouffe, C.; Weger, B.D.; Martin, E.; Atger, F.; Weger, M.; Gobet, C.; Ramnath, D.; Charpagne, A.; Morin-Rivron, D.; Powell, E.E.; et al. Disruption of the circadian clock component BMAL1 elicits an endocrine adaption impacting on insulin sensitivity and liver disease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2022, 119, e2200083119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Pollock, D.M. Circadian regulation of kidney function: Finding a role for Bmal1. Am. J. Physiol.-Ren. Physiol. 2018, 314, F675–F678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheer, F.A.; Van Montfrans, G.A.; van Someren, E.J.; Mairuhu, G.; Buijs, R.M. Daily nighttime melatonin reduces blood pressure in male patients with essential hypertension. Hypertension 2004, 43, 192–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalra, S.; Agrawal, S.; Sahay, M. The reno-pineal axis: A novel role for melatonin. Indian J. Endocrinol. Metab. 2012, 16, 192–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cagnacci, A.; Cannoletta, M.; Renzi, A.; Baldassari, F.; Arangino, S.; Volpe, A. Prolonged melatonin administration decreases nocturnal blood pressure in women. Am. J. Hypertens. 2005, 18, 1614–1618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirdas, A.; Naziroglu, M.; Unal, G.O. Agomelatine reduces brain, kidney and liver oxidative stress but increases plasma cytokine production in the rats with chronic mild stress-induced depression. Metab. Brain Dis. 2016, 31, 1445–1453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, A.; Hasan, A.U.; Kobori, H. Melatonin in chronic kidney disease: A promising chronotherapy targeting the intrarenal renin-angiotensin system. Hypertens. Res. 2019, 42, 920–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishigaki, S.; Ohashi, N.; Matsuyama, T.; Isobe, S.; Tsuji, N.; Iwakura, T.; Fujikura, T.; Tsuji, T.; Kato, A.; Miyajima, H.; et al. Melatonin ameliorates intrarenal renin-angiotensin system in a 5/6 nephrectomy rat model. Clin. Exp. Nephrol. 2018, 22, 539–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohashi, N.; Ishigaki, S.; Isobe, S. The pivotal role of melatonin in ameliorating chronic kidney disease by suppression of the renin-angiotensin system in the kidney. Hypertens. Res. 2019, 42, 761–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, Y.; He, X.; Liu, Z.; Miao, L.; Zhu, B. The potential of melatonin in sepsis-associated acute kidney injury: Mitochondrial protection and cGAS-STING signaling pathway. Heliyon 2025, 11, e41501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherngwelling, R.; Pengrattanachot, N.; Swe, M.T.; Thongnak, L.; Promsan, S.; Phengpol, N.; Sutthasupha, P.; Lungkaphin, A. Agomelatine protects against obesity-induced renal injury by inhibiting endoplasmic reticulum stress/apoptosis pathway in rats. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2021, 425, 115601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milletsever, A.; Asci, H.; Taner, R.; Ozmen, O. Protective effects of tasimelteon on kidney injury in a traumatic brain injury rat model: A histopathological and immunohistochemical study. Eur. J. Trauma Emerg. Surg. 2025, 51, 241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, P.; Liu, W.; Wei, Y. Ramelteon attenuates renal ischemia and reperfusion injury through reducing mitochondrial fission and fusion and inflammation. Transl. Androl. Urol. 2023, 12, 1859–1870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Yin, J.; Yang, G. Melatonin upregulates BMAL1 to attenuate chronic sleep deprivation-related cognitive impairment by alleviating oxidative stress. Brain Behav. 2023, 13, e2836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardinali, D.P.; Vigo, D.E. Melatonin; mitochondria, and the metabolic syndrome. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 2017, 74, 3941–3954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uhlen, M.; Fagerberg, L.; Hallstrom, B.M.; Lindskog, C.; Oksvold, P.; Mardinoglu, A.; Sivertsson, A.; Kampf, C.; Sjostedt, E.; Asplund, A.; et al. Tissue-based map of the human proteome. Science 2015, 347, 1260419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sert, N.P.D.; Hurst, V.; Ahluwalia, A.; Alam, S.; Avey, M.T.; Baker, M.; Browne, W.J.; Clark, A.; Cuthill, I.C.; Dirnagl, U.; et al. The ARRIVE guidelines 2.0: Updated guidelines for reporting animal research. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2020, 177, 3617–3624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Speed, J.S.; Hyndman, K.A.; Roth, K.; Heimlich, J.B.; Kasztan, M.; Fox, B.M.; Johnston, J.G.; Becker, B.K.; Jin, C.; Gamble, K.L.; et al. High dietary sodium causes dyssynchrony of the renal molecular clock in rats. Am. J. Physiol.-Ren. Physiol. 2018, 314, F89–F98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kielkopf, C.L.; Bauer, W.; Urbatsch, I.L. Bradford Assay for Determining Protein Concentration. Cold Spring Harb. Protoc. 2020, 2020, 102269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cherezova, A.; Sudarikova, A.; Vasileva, V.; Iurchenko, R.; Nikiforova, A.; Spires, D.R.; Zamaro, A.S.; Jones, A.C.; Schibalski, R.S.; Dong, Z.; et al. The effects of the atrial natriuretic peptide deficiency on renal cortical mitochondrial bioenergetics in the Dahl SS rat. FASEB J. 2024, 38, e23891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palygin, O.; Spires, D.; Levchenko, V.; Bohovyk, R.; Fedoriuk, M.; Klemens, C.A.; Sykes, O.; Bukowy, J.D.; Cowley, A.W., Jr.; Lazar, J.; et al. Progression of diabetic kidney disease in T2DN rats. Am. J. Physiol.-Ren. Physiol. 2019, 317, F1450–F1461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, J.G.; Speed, J.S.; Becker, B.K.; Kasztan, M.; Soliman, R.H.; Rhoads, M.K.; Tao, B.; Jin, C.; Geurts, A.M.; Hyndman, K.A.; et al. Diurnal Control of Blood Pressure Is Uncoupled from Sodium Excretion. Hypertension 2020, 75, 1624–1634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kravtsova, O.; Bohovyk, R.; Levchenko, V.; Palygin, O.; Klemens, C.A.; Rieg, T.; Staruschenko, A. SGLT2 inhibition effect on salt-induced hypertension, RAAS, and Na(+) transport in Dahl SS rats. Am. J. Physiol.-Ren. Physiol. 2022, 322, F692–F707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schindelin, J.; Arganda-Carreras, I.; Frise, E.; Kaynig, V.; Longair, M.; Pietzsch, T.; Preibisch, S.; Rueden, C.; Saalfeld, S.; Schmid, B.; et al. Fiji: An open-source platform for biological-image analysis. Nat. Methods 2012, 9, 676–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sung, W.W.; Lin, Y.M.; Wu, P.R.; Yen, H.H.; Lai, H.W.; Su, T.C.; Huang, R.H.; Wen, C.K.; Chen, C.Y.; Chen, C.J.; et al. High nuclear/cytoplasmic ratio of Cdk1 expression predicts poor prognosis in colorectal cancer patients. BMC Cancer 2014, 14, 951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gentle, M.E.; Shi, S.; Daehn, I.; Zhang, T.; Qi, H.; Yu, L.; D’Agati, V.D.; Schlondorff, D.O.; Bottinger, E.P. Epithelial cell TGFbeta signaling induces acute tubular injury and interstitial inflammation. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2013, 24, 787–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Z.; Qi, X.; Yang, W.; Xia, L.; Wu, Y. Melatonin Ameliorates Renal Fibrosis Through the Inhibition of NF-kappaB and TGF-beta1/Smad3 Pathways in db/db Diabetic Mice. Arch. Med. Res. 2020, 51, 524–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taguchi, S.; Azushima, K.; Yamaji, T.; Urate, S.; Suzuki, T.; Abe, E.; Tanaka, S.; Tsukamoto, S.; Kamimura, D.; Kinguchi, S.; et al. Effects of tumor necrosis factor-alpha inhibition on kidney fibrosis and inflammation in a mouse model of aristolochic acid nephropathy. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 23587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omote, K.; Gohda, T.; Murakoshi, M.; Sasaki, Y.; Kazuno, S.; Fujimura, T.; Ishizaka, M.; Sonoda, Y.; Tomino, Y. Role of the TNF pathway in the progression of diabetic nephropathy in KK-A(y) mice. Am. J. Physiol.-Ren. Physiol. 2014, 306, F1335–F1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benjamin, J.I.; Pati, P.; Luong, T.; Liu, X.; De Miguel, C.; Pollock, J.S.; Pollock, D.M. Chronic mistimed feeding results in renal fibrosis and disrupted circadian blood pressure rhythms. Am. J. Physiol.-Ren. Physiol. 2024, 327, F683–F696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jung-Hynes, B.; Huang, W.; Reiter, R.J.; Ahmad, N. Melatonin resynchronizes dysregulated circadian rhythm circuitry in human prostate cancer cells. J. Pineal Res. 2010, 49, 60–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Kalmukova, O.; Zavora, A.; Cherezova, A.; Savchuk, O.; Stefanenko, M.; Fedoriuk, M.; Jones, A.C.; Nepomnyashchy, V.; Dzerzhynskyi, M.; Semenikhina, M.; et al. Melatonin Administration Attenuates High-Fat-Diet-Induced Renal Damage in Wistar Rats. Biomolecules 2026, 16, 36. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom16010036

Kalmukova O, Zavora A, Cherezova A, Savchuk O, Stefanenko M, Fedoriuk M, Jones AC, Nepomnyashchy V, Dzerzhynskyi M, Semenikhina M, et al. Melatonin Administration Attenuates High-Fat-Diet-Induced Renal Damage in Wistar Rats. Biomolecules. 2026; 16(1):36. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom16010036

Chicago/Turabian StyleKalmukova, Olesia, Anastasiia Zavora, Alena Cherezova, Olexiy Savchuk, Mariia Stefanenko, Mykhailo Fedoriuk, Adam C. Jones, Valentyn Nepomnyashchy, Mykola Dzerzhynskyi, Marharyta Semenikhina, and et al. 2026. "Melatonin Administration Attenuates High-Fat-Diet-Induced Renal Damage in Wistar Rats" Biomolecules 16, no. 1: 36. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom16010036

APA StyleKalmukova, O., Zavora, A., Cherezova, A., Savchuk, O., Stefanenko, M., Fedoriuk, M., Jones, A. C., Nepomnyashchy, V., Dzerzhynskyi, M., Semenikhina, M., Ilatovskaya, D. V., & Palygin, O. (2026). Melatonin Administration Attenuates High-Fat-Diet-Induced Renal Damage in Wistar Rats. Biomolecules, 16(1), 36. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom16010036