Effect of the Icelandic Mutation APPA673T in the Murine APP Gene on Phenotype of Line 66 Tau Mice

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Animals

2.3. Behavioural Testing

2.3.1. Rotarod

2.3.2. PhenoTyper

2.3.3. Nest Building Test

2.3.4. Sucrose Preference

2.3.5. Buried Cookie Test

2.3.6. Social Interaction

2.4. Tissue Collection

2.5. Immunohistochemistry (IHC) and Quantification of Tau

2.6. Protein Extraction

2.7. Quantification of Tau, Aβ, and Synaptic Proteins Using ELISA

2.8. Data Analysis

3. Results

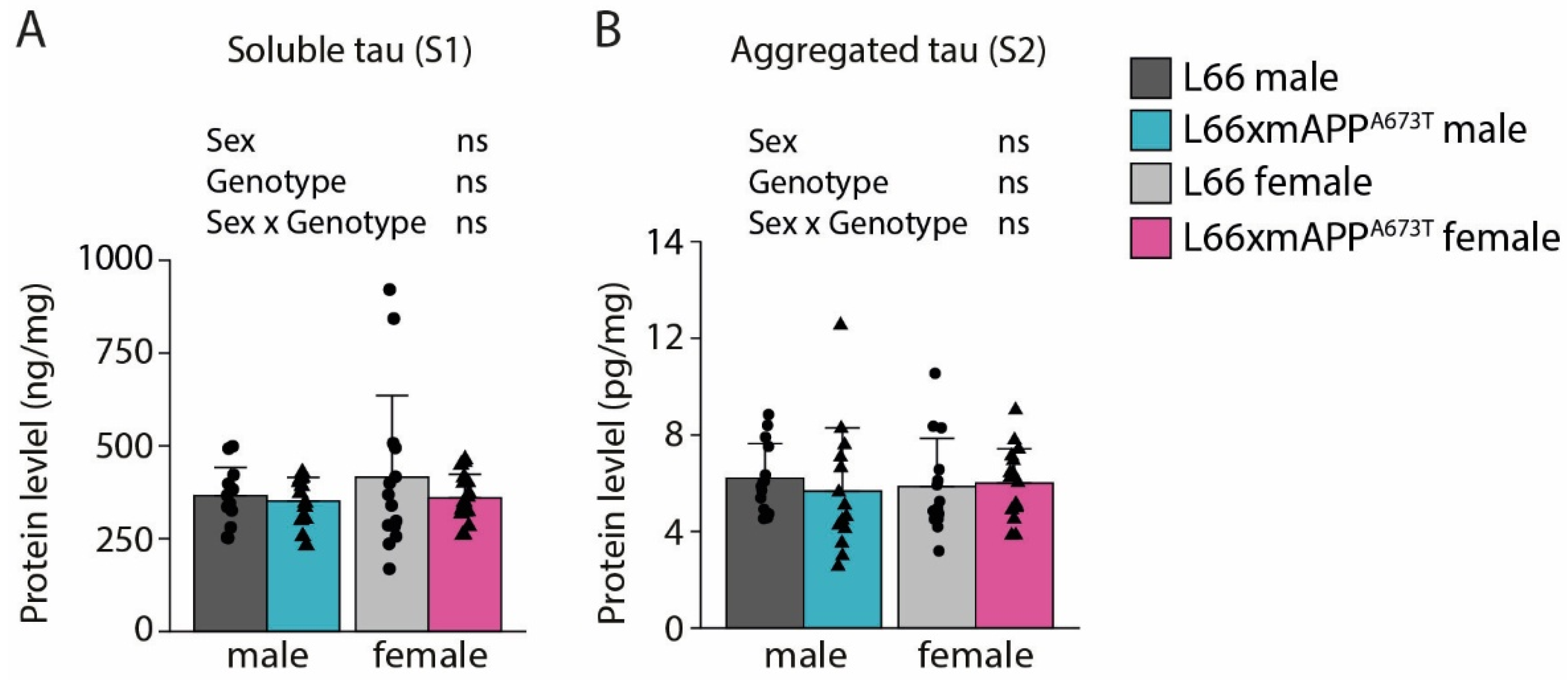

3.1. Icelandic Mutation and Tau Pathology

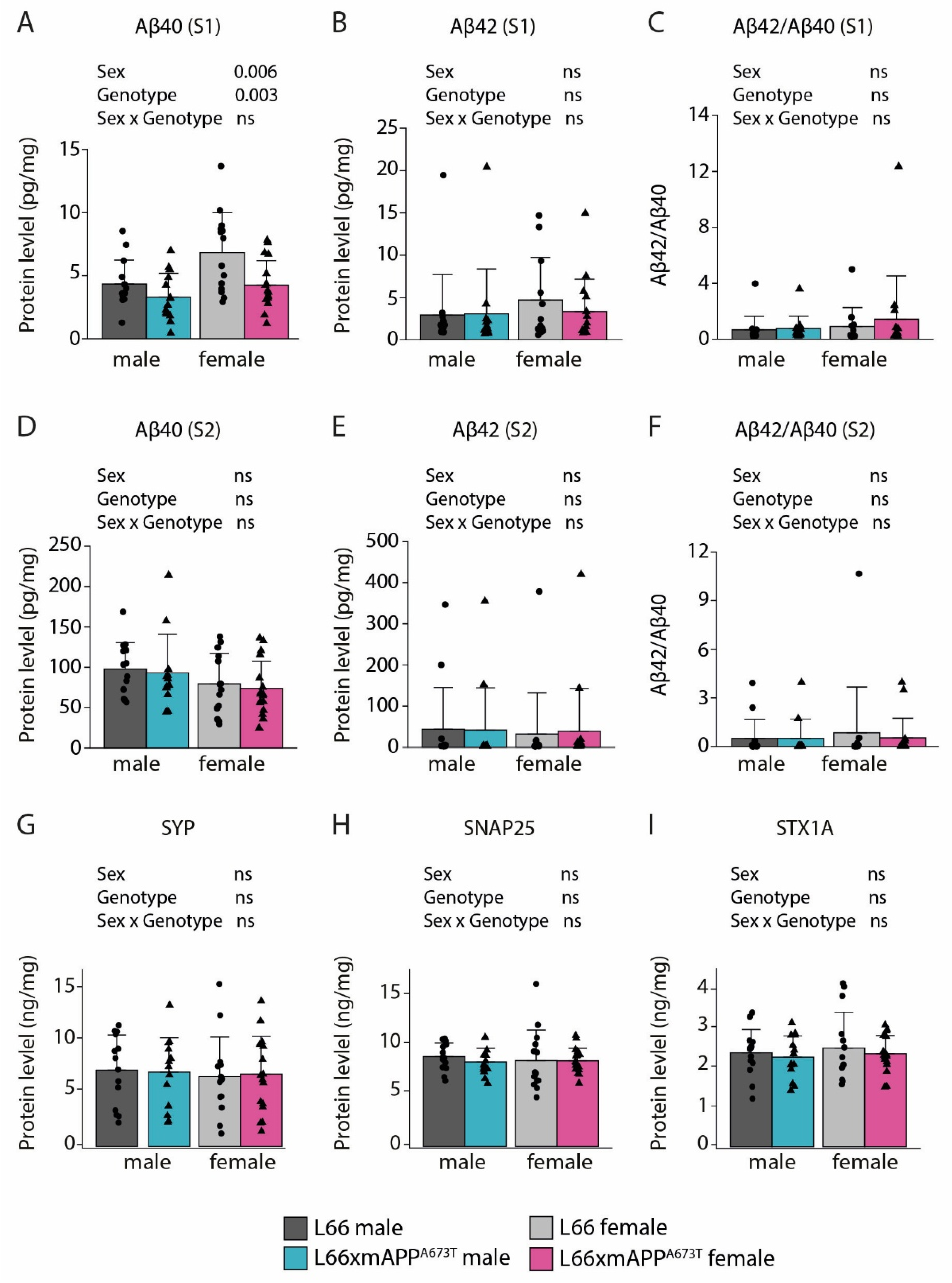

3.2. Icelandic Mutation, Aβ, and Synaptic Proteins

3.3. Icelandic Mutation and Behaviour

4. Discussion

4.1. mA673T Aβ Has a Marginal Impact on Tau Pathology and Soluble Aβ40 Levels in L66 Mice In Vivo

4.2. mA673T Aβ Does Not Modify Synaptic Protein Expression in L66 In Vivo

4.3. mA673T Aβ Does Not Modulate Motor and Neuropsychiatric Phenotypes in L66 Tau Transgenic Mice

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

References

- Scott, K.R.; Barrett, A.M. Dementia syndromes: Evaluation and treatment. Expert Rev. Neurother. 2007, 7, 407–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzheimer, A. Über eine eigenartige Erkrankung der Hirnrinde. Allg. Z. Psychiatr. Psych.-Gerichtl. Med. 1907, 64, 146–148. [Google Scholar]

- Goedert, M.; Wischik, C.M.; Crowther, R.A.; Walker, J.E.; Klug, A. Cloning and sequencing of the cDNA encoding a core protein of the paired helical filament of Alzheimer disease: Identification as the microtubule-associated protein tau (molecular pathology/neurodegenerative disease/neurofibriliary tangles). Proc. Nati. Acad. Sci. USA 1988, 85, 4051–4055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wischik, C.M.; Crowtber, R.A. Subunit Structure of the Alzheimer Tangle. Br. Med. Bull. 1986, 42, 51–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wischik, C.M.; Crowther, R.A.; Stewart, M.; Roth, M. Subunit structure of paired helical filaments in Alzheimer’s disease. J. Cell Biol. 1985, 100, 1905–1912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wischik, C.M.; Novak, M.; Edwards, P.C.; Klug, A.; Tichelaar, W.; Crowther, R.A. Structural characterization of the core of the paired helical filament of Alzheimer disease (molecular pathology/neurodegenerative disease/neurofibrillary tangles/snnng transmission electron microscopy). Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1988, 85, 4884–4888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wischik, C.M.; Novák, M.; Thøgersen, H.C.; Edwards, P.C.; Runswick, M.J.; Jakes, R.; Walker, J.E.; Milstein, C.; Roth, M.; Klug, A. Isolation of a fragment of tau derived from the core of the paired helical filament of Alzheimer disease (molecular pathology/neurodegenerative disease/neurofibrillary tangles). Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1988, 85, 4506–4510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eanes, E.D.; Glenner, G.G. X-ray diffraction studies on amyloid filaments. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 1968, 16, 673–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glenner, G.G.; Wong, C.W. Alzheimer’s disease: Initial report of the purification and characterization of a novel cerebrovascular amyloid protein. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1984, 120, 885–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masters, C.L.; Simms, G.; Weinman, N.A.; Multhaupt, G.; Mcdonald, B.L.; Beyreuthert, K. Amyloid plaque core protein in Alzheimer disease and Down syndrome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1985, 82, 4245–4249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weingarten, M.D.; Lockwood, A.H.; Hwo, S.Y.; Kirschner, M.W. A Protein Factor Essential for Microtubule Assembly (tau factor/tubulin/electron microscopy/phosphocellulose). Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1975, 72, 1858–1862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mietelska-Porowska, A.; Wasik, U.; Goras, M.; Filipek, A.; Niewiadomska, G. Tau protein modifications and interactions: Their role in function and dysfunction. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2014, 15, 4671–4713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bishop, G.M.; Robinson, S.R. Physiological Roles of Amyloid-β and Implications for its Removal in Alzheimer’s Disease. Drugs Aging 2004, 21, 621–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coulson, E.J.; Paliga, K.; Beyreuther, K.; Masters, C.L. What the evolution of the amyloid protein precursor supergene family tells us about its function. Neurochem. Int. 2000, 36, 175–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harada, A.; Oguchi, K.; Okabe, S.; Kuno, J.; Terada, S.; Ohshima, T.; Sato-Yoshitake, R.; Takei, Y.; Noda, T.; Hirokawa, N. Altered microtubule organization in small-calibre axons of mice lacking tau protein. Nature 1994, 369, 488–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikegami, S.; Harada, A.; Hirokawa, N. Muscle weakness, hyperactivity, and impairment in fear conditioning in tau-de®cient mice. Neurosci. Lett. 2000, 279, 129–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, H.; Jiang, M.; Trumbauer, M.E.; Sirinathsinghji, D.J.; Hopkins, R.; Smith, D.W.; Heavens, R.P.; Dawson, G.R.; Boyce, S.; Conner, M.W.; et al. Beta-Amyloid Precursor Protein-Deficient Mice Show Reactive Gliosis and Decreased Locomotor Activity. Cell 1995, 81, 525–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Götz, J.; Probst, A.; Spillantini, M.; Schäfer, T.; Jakes, R.; Bürki, K.; Goedert, M. Somatodendritic localization and hyperphosphorylation of tau protein in transgenic mice expressing the longest human brain tau isoform. EMBO J. 1995, 14, 1304–1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Probst, A.; Götz, J.; Wiederhold, K.H.; Tolnay, M.; Mistl, C.; Jaton, A.; Hong, M.; Ishihara, T.; Lee, V.M.-Y.; Trojanowski, J.Q.; et al. Axonopathy and amyotrophy in mice transgenic for human four-repeat tau protein. Acta Neuropathol. 2000, 99, 469–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spittaels, K.; Van Den Haute, C.; Dorpe, J.; Van, Bruynseels, K.; Vandezande, K.; Laenen, I.; Geerts, H.; Mercken, M.; Sciot, R.; Lommel, A.; et al. Prominent Axonopathy in the Brain and Spinal Cord of Transgenic Mice Overexpressing Four-Repeat Human tau Protein. Am. J. Pathol. 1999, 155, 2153–2165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodart, J.-C.; Meziane, H.; Mathis, C.; Bales, K.R.; Paul, S.M. Behavioral Disturbances in Transgenic Mice Overexpressing the V717F β-Amyloid Precursor Protein. Behav. Neurosci. 1999, 113, 982–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Games, D.; Adams, D.; Alessandrini, R.; Barbour, R.; Borthelette, P.; Blackwell, C.; Carr, T.; Clemens, J.; Donaldson, T.; Gillespie, F.; et al. Alzheimer-type neuropathology in transgenic mice overexpressing V717F beta amyloid precursor protein. Nature 1995, 373, 523–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sturchler-Pierrat, C.; Abramowski, D.; Wiederhold, K.-H.; Mistl, C.; Rothacher, S.; Ledermann, B.; Bürkibürki, K.; Frey, P.; Paganetti, P.A.; Waridel, C.; et al. Two amyloid precursor protein transgenic mouse models with Alzheimer disease-like pathology. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1997, 94, 13287–13292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Citron, M.; Vigo-Pelfreyt, C.; Teplow, D.B.; Miller, C.; Schenkt, D.; Johnstont, J.; Winblad, B.; Venizelost, N.; Lannfelt, L.; Selkoe, D.J. Excessive production of amyloid β-protein by peripheral cells of symptomatic and presymptomatic patients carrying the Swedish familial Alzheimer disease mutation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1994, 91, 11993–11997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’souza, I.; Poorkaj, P.; Hong, M.; Nochlin, D.; Lee, V.M.-Y.; Bird, T.D.; Schellenberg, G.D. Missense and silent tau gene mutations cause frontotemporal dementia with parkinsonism-chromosome 17 type, by affecting multiple alternative RNA splicing regulatory elements. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1999, 96, 5598–5603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giaccone, G.; Morbin, M.; Moda, F.; Botta, M.; Mazzoleni, G.; Uggetti, A.; Catania, M.; Moro, M.L.; Redaelli, V.; Spagnoli, A.; et al. Neuropathology of the recessive A673V APP mutation: Alzheimer disease with distinctive features. Acta Neuropathol. 2010, 120, 803–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goate, A.; Chartier-Harlin, M.C.; Mullan, M.; Brown, J.; Crawford, F.; Fidani, L.; Giuffra, L.; Haynes, A.; Irving, N.; James, L. Segregation of a missense mutation in the amyloid precursor protein gene with familial Alzheimer’s disease. Nature 1991, 349, 704–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goedert, M. Tau gene mutations and their effects. Mov. Disord. 2005, 20, S45–S52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshida, H.; Crowther, R.A.; Goedert, M. Functional effects of tau gene mutations ΔN296 and N296H. J. Neurochem. 2002, 80, 548–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rapoport, M.; Dawson, H.N.; Binder, L.I.; Vitek, M.P.; Ferreira, A. Tau is essential to-amyloid-induced neurotoxicity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2002, 99, 6364–6369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberson, E.D.; Scearce-Levie, K.; Palop, J.J.; Yan, F.; Cheng, I.H.; Wu, T.; Gerstein, H.; Yu, G.Q.; Mucke, L. Reducing endogenous tau ameliorates amyloid beta-induced deficits in an Alzheimer’s disease mouse mode. Science 2007, 316, 750–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leroy, K.; Ando, K.; Laporte, V.; Dedecker, R.; Suain, V.; Authelet, M.; Héraud, C.; Pierrot, N.; Yilmaz, Z.; Octave, J.N.; et al. Lack of tau proteins rescues neuronal cell death and decreases amyloidogenic processing of APP in APP/PS1 mice. Am. J. Pathol. 2012, 181, 1928–1940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bright, J.; Hussain, S.; Dang, V.; Wright, S.; Cooper, B.; Byun, T.; Ramos, C.; Singh, A.; Parry, G.; Stagliano, N.; et al. Human secreted tau increases amyloid-beta production. Neurobiol. Aging 2015, 36, 693–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, G.; Ran, Y.; Fromholt, S.E.; Fu, C.; Yachnis, A.T.; Golde, T.E.; Borchelt, D.R. Murine Aβ over-production produces diffuse and compact Alzheimer-type amyloid deposits. Acta Neuropathol. Commun. 2015, 3, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahler, J.; Morales-Corraliza, J.; Stolz, J.; Skodras, A.; Radde, R.; Duma, C.C.; Eisele, Y.S.; Mazzella, M.J.; Wong, H.; Klunk, W.E.; et al. Endogenous murine Aβ increases amyloid deposition in APP23 but not in APPPS1 transgenic mice. Neurobiol. Aging 2015, 36, 2241–2247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemke, N.; Melis, V.; Lauer, D.; Magbagbeolu, M.; Neumann, B.; Harrington, C.R.; Riedel, G.; Wischik, C.M.; Theuring, F.; Schwab, K. Differential compartmental processing and phosphorylation of pathogenic human tau and native mouse tau in the line 66 model of frontotemporal dementia. J. Biol. Chem. 2020, 295, 18508–18523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melis, V.; Zabke, C.; Stamer, K.; Magbagbeolu, M.; Schwab, K.; Marschall, P.; Veh, R.W.; Bachmann, S.; Deiana, S.; Moreau, P.H.; et al. Different pathways of molecular pathophysiology underlie cognitive and motor tauopathy phenotypes in transgenic models for Alzheimer’s disease and frontotemporal lobar degeneration. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2015, 72, 2199–2222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, L.; Dreesen, E.; Mondesir, M.; Harrington, C.; Wischik, C.; Riedel, G. Apathy-like behaviour in tau mouse models of Alzheimer’s disease and frontotemporal dementia. Behav. Brain Res. 2024, 456, 114707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwab, K.; Melis, V.; Harrington, C.R.; Wischik, C.M.; Magbagbeolu, M.; Theuring, F.; Riedel, G. Proteomic Analysis of Hydromethylthionine in the Line 66 Model of Frontotemporal Dementia Demonstrates Actions on Tau-Dependent and Tau-Independent Networks. Cells 2021, 10, 2162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwab, K.; Robinson, L.; Annschuetz, A.; Dreesen, E.; Magbagbeolu, M.; Melis, V.; Theuring, F.; Harrington, C.R.; Wischik, C.M.; Riedel, G. Rivastigmine interferes with the pharmacological activity of hydromethylthionine on presynaptic proteins in the line 66 model of frontotemporal dementia. Brain Res. Bull. 2025, 220, 111172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spillantini, M.G.; Bird, T.D.; Ghetti, B. Frontotemporal dementia and Parkinsonism linked to chromosome 17: A new group of tauopathies. Brain Pathol. 1998, 8, 387–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jonsson, T.; Atwal, J.K.; Steinberg, S.; Snaedal, J.; Jonsson, P.V.; Bjornsson, S.; Stefansson, H.; Sulem, P.; Gudbjartsson, D.; Maloney, J.; et al. A mutation in APP protects against Alzheimer‘s disease and age-related cognitive decline. Nature 2012, 488, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martiskainen, H.; Herukka, S.K.; Stančáková, A.; Paananen, J.; Soininen, H.; Kuusisto, J.; Laakso, M.; Hiltunen, M. Decreased plasma β-amyloid in the Alzheimer’s disease APP A673T variant carriers. Ann. Neurol. 2017, 82, 128–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blennow, K.; De Leon, M.J.; Zetterberg, H. Alzheimer’s disease. Lancet 2006, 368, 368–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hampel, H.; Hardy, J.; Blennow, K.; Chen, C.; Perry, G.; Kim, S.H.; Villemagne, V.L.; Aisen, P.; Vendruscolo, M.; Iwatsubo, T.; et al. The Amyloid-β pathway in Alzheimer’s diseasea. Mol. Psychiatry 2021, 26, 5481–5503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Q.; Yang, X.; Shi, J.; Liu, Z.; Peng, Y.; Wang, W.; Li, B.; Zhao, Y.; Xiao, J.; Huang, L.; et al. The Protective A673T mutation of amyloid precursor protein (APP) in Alzheimer’s disease. Mol. Neurobiol. 2021, 58, 4038–4050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimohama, S.; Fujioka, R.; Mihira, N.; Sekiguchi, M.; Sartori, L.; Joho, D.; Saito, T.; Saido, T.C.; Nakahara, J.; Hino, T.; et al. The Icelandic mutation (APP-A673T) is protective against amyloid pathology in vivo. J. Neurosci. 2024, 44, e0223242024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Célestine, M.; Jacquier-Sarlin, M.; Borel, E.; Petit, F.; Lante, F.; Bousset, L.; Hérard, A.S.; Buisson, A.; Dhenain, M. Transmissible long-term neuroprotective and pro-cognitive effects of 1–42 beta-amyloid with A2T icelandic mutation in an Alzheimer’s disease mouse model. Mol. Psychiatry 2024, 29, 3707–3721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- du Sert, N.P.; Hurst, V.; Ahluwalia, A.; Alam, S.; Avey, M.T.; Baker, M.; Browne, W.J.; Clark, A.; Cuthill, I.C.; Dirnagl, U.; et al. The arrive guidelines 2.0: Updated guidelines for reporting animal research. PLoS Biol. 2020, 18, e3000410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deacon, R. Assessing burrowing, nest construction, and hoarding in mice. J. Vis. Exp. 2012, 59, 2607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paxinos, G.; Franklin, K. The Mouse Brain in Stereotaxic Coordinates, 5th ed.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Berg, S.; Kutra, D.; Kroeger, T.; Straehle, C.N.; Kausler, B.X.; Haubold, C.; Schiegg, M.; Ales, J.; Beier, T.; Rudy, M.; et al. ilastik: Interactive machine learning for (bio)image analysis. Nat. Methods 2019, 16, 1226–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schindelin, J.; Arganda-Carreras, I.; Frise, E.; Kaynig, V.; Longair, M.; Pietzsch, T.; Preibisch, S.; Rueden, C.; Saalfeld, S.; Schmid, B.; et al. Fiji: An open-source platform for biological-image analysis. Nat. Methods 2012, 9, 676–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kay, M.; Wobbrock, J. Aligned Rank Transform for Nonparametric Factorial ANOVAs. R Package Version 0.11.1. 2020. Available online: https://github.com/mjskay/ARTool (accessed on 31 July 2025).

- Jennrich, R.I. An Asymptotic χ2 Test for the Equality of Two Correlation Matrices. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1970, 65, 904–912. [Google Scholar]

- Grieco, F.; Bernstein, B.J.; Biemans, B.; Bikovski, L.; Burnett, C.J.; Cushman, J.D.; van Dam, E.A.; Fry, S.A.; Richmond-Hacham, B.; Homberg, J.R.; et al. Measuring behavior in the home cage: Study design, applications, challenges, and perspectives. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 2021, 15, 735387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cranston, A.L.; Kraev, I.; Stewart, M.G.; Horsley, D.; Santos, R.X.; Robinson, L.; Dreesen, E.; Armstrong, P.; Palliyil, S.; Harrington, C.R.; et al. Rescue of synaptosomal glutamate release defects in tau transgenic mice by the tau aggregation inhibitor Hydromethylthionine. Cell. Signal. 2024, 121, 111269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tambini, M.D.; Norris, K.A.; D’Adamio, L. Opposite changes in APP processing and human aβ levels in rats carrying either a protective or a pathogenic APP mutation. eLife 2020, 9, e52612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, R.Y.K.; Harrington, C.R.; Wischik, C.M. Absence of a role for phosphorylation in the tau pathology of Alzheimer’s disease. Biomolecules 2016, 6, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, A.; Biernat, J.; von Bergen, M.; Mandelkow, E.; Mandelkow, E.M. Phosphorylation that detaches tau protein from microtubules (Ser262, Ser214) also protects it against aggregation into Alzheimer paired helical filaments. Biochemistry 1999, 38, 3549–3558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wittrahm, R.; Takalo, M.; Kuulasmaa, T.; Mäkinen, P.M.; Mäkinen, P.; Končarević, S.; Fartzdinov, V.; Selzer, S.; Kokkola, T.; Antikainen, L.; et al. Protective Alzheimer’s disease-associated APP A673T variant predominantly decreases sAPPβ levels in cerebrospinal fluid and 2D/3D cell culture models. Neurobiol. Dis. 2023, 182, 106140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penny, L.K.; Arastoo, M.; Lofthouse, R.; Abdallah, A.; Imoesi, P.I.; Schwab, K.; Shiells, H.; Melis, V.; Riedel, G.; Harrington, C.R.; et al. Timing matters: Early administration of a high-affinity antibody targeting the tau repeat domain prevents aggregation in a mouse tauopathy model. Alzheimer’s Res. Ther. 2025; submitted. [Google Scholar]

- Busche, M.A.; Hyman, B.T. Synergy between amyloid-β and tau in Alzheimer’s disease. Nat. Neurosci. 2020, 23, 1183–1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vanden Dries, V.; Stygelbout, V.; Pierrot, N.; Yilmaz, Z.; Suain, V.; De Decker, R.; Buée, L.; Octave, J.N.; Brion, J.P.; Leroy, K. Amyloid precursor protein reduction enhances the formation of neurofibrillary tangles in a mutant tau transgenic mouse model. Neurobiol. Aging 2017, 55, 202–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anschuetz, A.; Schwab, K.; Harrington, C.R.; Wischik, C.M.; Riedel, G. A Meta-Analysis on Presynaptic Changes in Alzheimer’s Disease. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2024, 97, 145–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Wilde, M.C.; Overk, C.R.; Sijben, J.W.; Masliah, E. Meta-analysis of synaptic pathology in Alzheimer’s disease reveals selective molecular vesicular machinery vulnerability. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2016, 12, 633–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spires-Jones, T.L.; Hyman, B.T. The intersection of amyloid beta and tau at synapses in Alzheimer’s disease. Neuron 2014, 82, 756–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anschuetz, A.; Schwab, K.; Harrington, C.R.; Wischik, C.M.; Riedel, G. Proteomic and non-proteomic changes of presynaptic proteins in animal models of Alzheimer’s disease: A meta-analysis 2015–2023. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2025, 107, 452–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kero, M.; Paetau, A.; Polvikoski, T.; Tanskanen, M.; Sulkava, R.; Jansson, L.; Myllykangas, L.; Tienari, P.J. Amyloid precursor protein (APP) A673T mutation in the elderly Finnish population. Neurobiol. Aging 2013, 34, 1518.e1–1518.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantu’, L.; Colombo, L.; Stoilova, T.; Demé, B.; Inouye, H.; Booth, R.; Rondelli, V.; Di Fede, G.; Tagliavini, F.; Del Favero, E.; et al. The A2V mutation as a new tool for hindering Aβ aggregation: A neutron and x-ray diffraction study. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 5510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Fede, G.; Catania, M.; Morbin, M.; Rossi, G.; Suardi, S.; Mazzoleni, G.; Merlin, M.; Giovagnoli, A.R.; Prioni, S.; Erbetta, A.; et al. A recessive mutation in the APP gene with dominant-negative effect on amyloidogenesis. Science 2009, 323, 1473–1477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diomede, L.; Zanier, E.R.; Moro, F.; Vegliante, G.; Colombo, L.; Russo, L.; Cagnotto, A.; Natale, C.; Xodo, F.M.; De Luigi, A.; et al. Aβ1-6A2V(D) peptide, effective on Aβ aggregation, inhibits tau misfolding and protects the brain after traumatic brain injury. Mol. Psychiatry 2023, 28, 2433–2444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plucińska, K.; Crouch, B.; Koss, D.; Robinson, L.; Siebrecht, M.; Riedel, G.; Platt, B. Knock-in of human BACE1 cleaves murine APP and reiterates Alzheimer-like phenotypes. J. Neurosci. 2014, 34, 10710–10728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| N Male (Cohort 1 and Cohort 2) | N Female (Cohort 1 and Cohort 2) | |

|---|---|---|

| L66 | 14 (7 and 7) | 14 (7 and 7) |

| L66 x mA673T | 14 (7 and 7) | 17 (9 and 8) |

| N—Total | ∑ 59 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Anschuetz, A.; Robinson, L.; Mondesir, M.; Melis, V.; Platt, B.; Harrington, C.R.; Riedel, G.; Schwab, K. Effect of the Icelandic Mutation APPA673T in the Murine APP Gene on Phenotype of Line 66 Tau Mice. Biomolecules 2026, 16, 28. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom16010028

Anschuetz A, Robinson L, Mondesir M, Melis V, Platt B, Harrington CR, Riedel G, Schwab K. Effect of the Icelandic Mutation APPA673T in the Murine APP Gene on Phenotype of Line 66 Tau Mice. Biomolecules. 2026; 16(1):28. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom16010028

Chicago/Turabian StyleAnschuetz, Anne, Lianne Robinson, Miguel Mondesir, Valeria Melis, Bettina Platt, Charles R. Harrington, Gernot Riedel, and Karima Schwab. 2026. "Effect of the Icelandic Mutation APPA673T in the Murine APP Gene on Phenotype of Line 66 Tau Mice" Biomolecules 16, no. 1: 28. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom16010028

APA StyleAnschuetz, A., Robinson, L., Mondesir, M., Melis, V., Platt, B., Harrington, C. R., Riedel, G., & Schwab, K. (2026). Effect of the Icelandic Mutation APPA673T in the Murine APP Gene on Phenotype of Line 66 Tau Mice. Biomolecules, 16(1), 28. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom16010028