From Mechanism to Medicine: Peptide-Based Approaches for Cancer Diagnosis and Therapy

Abstract

1. Introduction

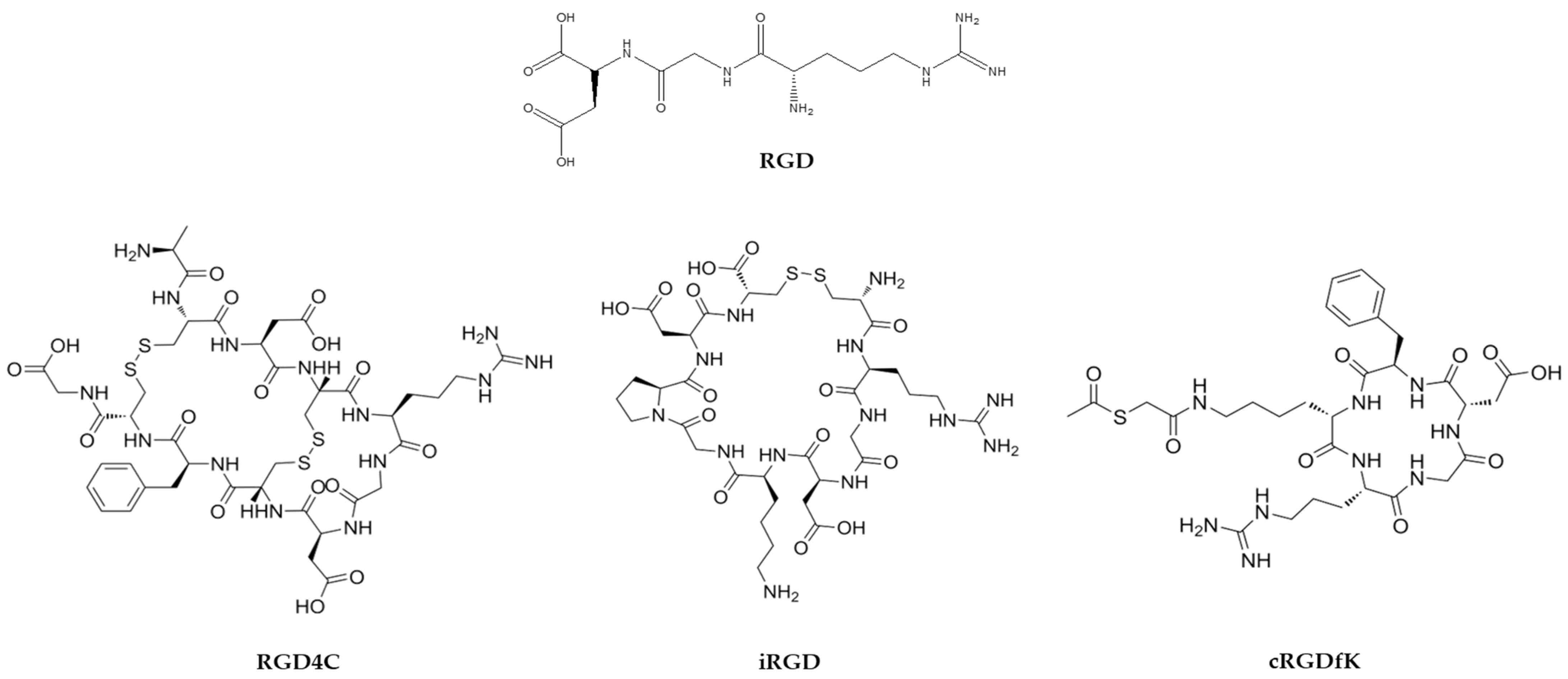

2. Peptide Conjugate Modalities for Target Therapy

2.1. Nanocarrier Peptide Systems

2.2. Peptide Guide Radionuclides

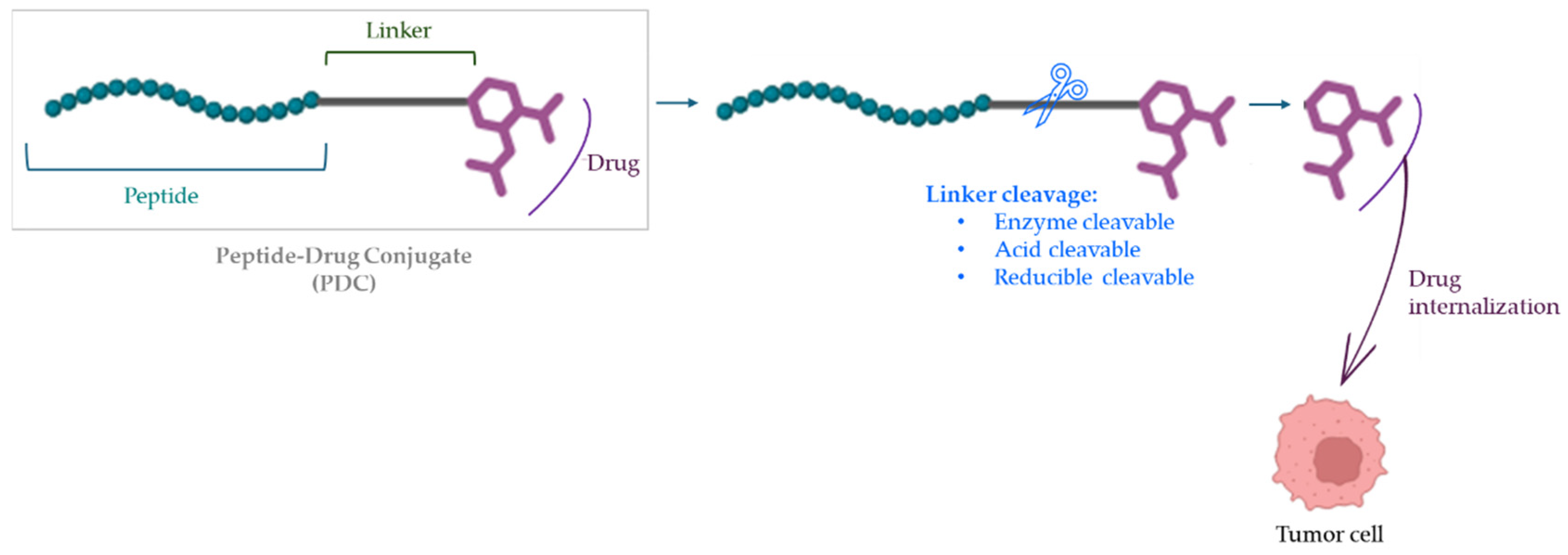

2.3. Peptide–Drug Conjugates (PDCs)

3. Peptides with Intrinsic Antitumor Activity

3.1. Peptide Antagonists/Agonists of Receptor Tyrosine Kinases and Hormone Receptors

3.2. Intracellular Protein–Protein Interactions

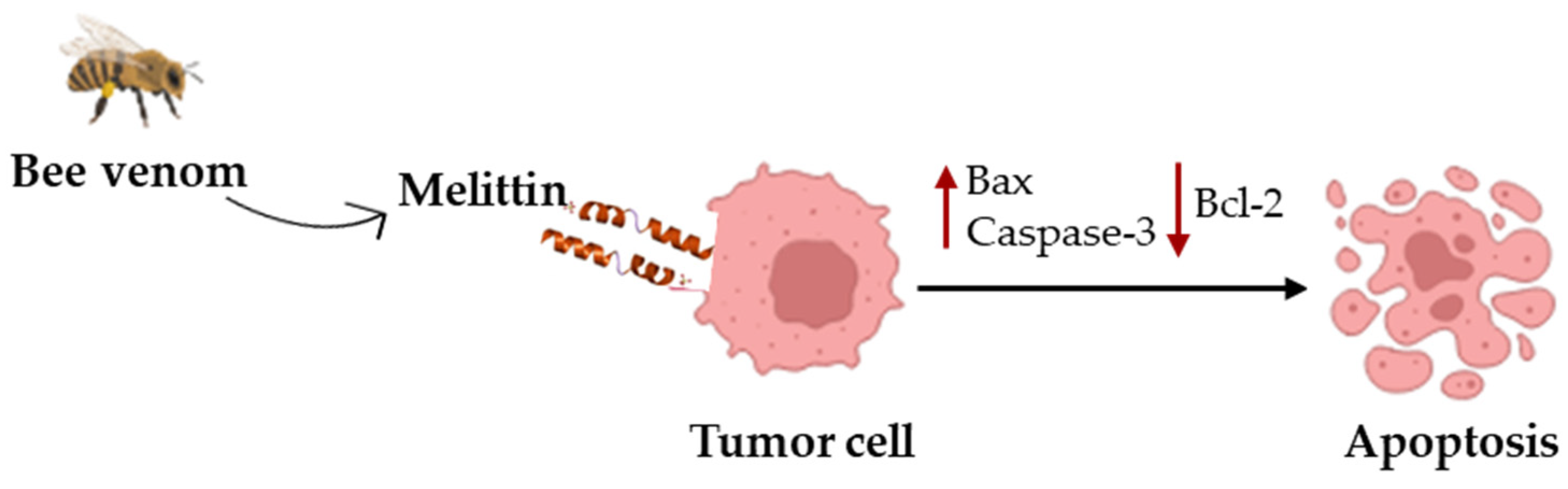

3.3. Cytotoxic Peptides

3.4. Cell-Penetrating Peptides as Therapeutics

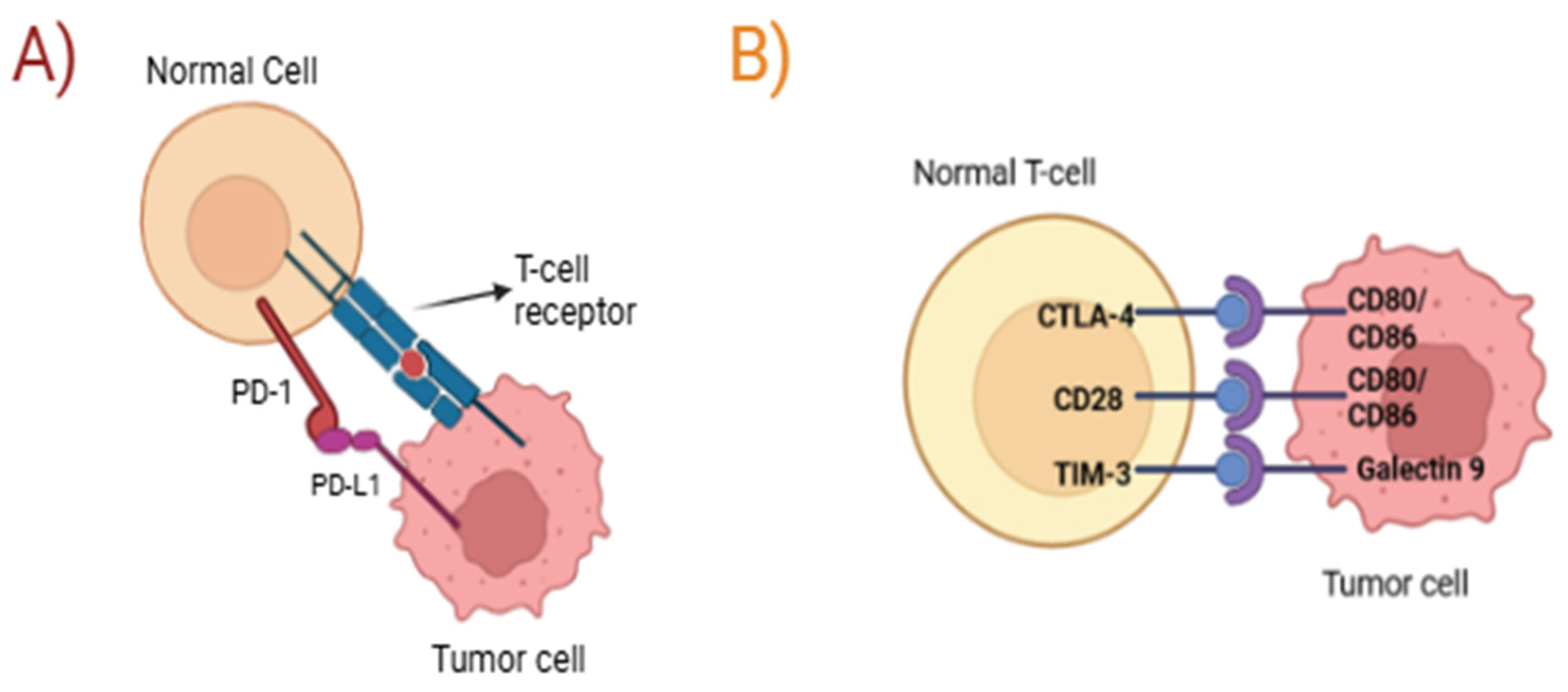

4. Peptide-Based Immune Modulation

4.1. Therapeutic Peptides as Anticancer Vaccines

4.2. Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors

5. Translation Challenges and Clinical Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Marqus, S.; Pirogova, E.; Piva, T.J. Evaluation of the use of therapeutic peptides for cancer treatment. J. Biomed. Sci. 2017, 24, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Available online: https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/understanding/what-is-cancer (accessed on 16 April 2025).

- Moreno-Vargas, L.M.; Prada-Gracia, D. Cancer-Targeting Applications of Cell-Penetrating Peptides. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 26, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yavari, B.; Mahjub, R.; Saidijam, M.; Raigani, M.; Soleimani, M. The Potential Use of Peptides in Cancer Treatment. Curr. Protein Pept. Sci. 2018, 19, 759–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fosgerau, K.; Hoffmann, T. Peptide Therapeutics: Current Status and Future Directions. Drug Discov. Today 2015, 20, 122–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- FDA Guidances. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/drugs/guidance-compliance-regulatory-information/guidances-drugs (accessed on 8 April 2025).

- Bose, D.; Roy, L.; Chatterjee, S. Peptide therapeutics in the management of metastatic cancers. RSC Adv. 2022, 12, 21353–21373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vadevoo, S.M.P.; Gurung, S.; Lee, H.S.; Gunassekaran, G.R.; Lee, S.-M.; Yoon, J.-W.; Lee, Y.-K.; Lee, B. Peptides as Multifunctional Players in Cancer Therapy. Exp. Mol. Med. 2023, 55, 1099–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milewska, S.; Sadowska, A.; Stefaniuk, N.; Misztalewska-Turkowicz, I.; Wilczewska, A.Z.; Car, H.; Niemirowicz-Laskowska, K. Tumor-Homing Peptides as Crucial Component of Magnetic-Based Delivery Systems: Recent Developments and Pharmacoeconomical Perspective. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 6219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thongpon, P.; Tang, M.; Cong, Z. Peptide-Based Nanoparticle for Tumor Therapy. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 1415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Omidian, H.; Cubeddu, L.X.; Wilson, R.L. Peptide-Functionalized Nanomedicine: Advancements in Drug Delivery, Diagnostics, and Biomedical Applications. Molecules 2025, 30, 1572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jadhav, K.; Abhang, A.; Kole, E.B.; Gadade, D.; Dusane, A.; Iyer, A.; Sharma, A.; Rout, S.K.; Gholap, A.D.; Naik, J.; et al. Peptide-Drug Conjugates as Next-Generation Therapeutics: Exploring the Potential and Clinical Progress. Bioengineering 2025, 12, 481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagar, B.; Gupta, S.; Verma, S.K.; Reddy, Y.V.M.; Shukla, S. Navigating cancer therapy: Harnessing the power of peptide-drug conjugates as precision delivery vehicles. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2025, 283, 117131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, W.; Jiang, W.; Chen, Z.; Huang, Y.; Mao, J.; Zheng, W.; Hu, Y.; Shi, J. Advance in peptide-based drug development: Delivery platforms, therapeutics and vaccines. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2025, 10, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Fang, X.; Yang, Y.; Wang, C. Peptide-Enabled Targeted Delivery Systems for Therapeutic Applications. Front. Bioeng. Biotech. 2021, 9, 701504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, N.H.; Nguyen, D.D.; Nguyen, N.M.; Tran, C.; Thi, N.T.N.; Ho, D.T.; Nguyen, H.-N.; Tu, L.N. Dual-targeting exosomes for improved drug delivery in breast cancer. Nanomedicine 2023, 18, 599–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.-C.; Liu, F.-R.; Feng, Q.; Pan, X.-P.; Song, S.-L.; Yang, J.-L. RGD4C Peptide Mediates Anti-p21Ras scFv Entry into Tumor Cells and Produces an Inhibitory Effect on the Human Colon Cancer Cell Line SW480. BMC Cancer 2021, 21, 321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, D.; Lu, Z.; Xu, X.; Liu, W. RGD Peptide-Conjugated Polydopamine Nanoparticles Loaded with Doxorubicin for Combined Chemotherapy and Photothermal Therapy in Thyroid Cancer. Discov. Oncol. 2024, 15, 794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, B.; Tang, D.; Cui, J.; Jiang, H.; Yu, J.; Guo, Z. RGD-Based Self-Assembling Nanodrugs for Improved Tumor Therapy. Front. Pharmacol. 2024, 15, 1477409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheikh, A.; Alhakamy, N.A.; Md, S.; Kesharwani, P. Recent Progress of RGD Modified Liposomes as Multistage Rocket Against Cancer. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 12, 803304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Javid, H.; Oryani, M.A.; Rezagholinejad, N.; Hashemzad, A.; Karimi-Shahri, M.J. Unlocking the Potential pf RGD-Conjugated Gold Nanoparticles: A New Frontier in Targeted Cancer Therapy, Imaging, and Metastasis Inhibition. Mater. Chem. B 2024, 12, 10786–10817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenzoni, S.; Rodríguez-Nogales, C.; Blanco-Prieto, M.J. Targeting Tumor Microenvironment with RGD-Functionalized Nanoparticles for Precision Cancer therapy. Cancer Lett. 2025, 614, 217536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, L.; Li, X.; Wang, R.; Zeng, Y.; Zheng, Z.; Xie, T. Recent Research Progress of RGD Peptide–Modified Nanodrug Delivery Systems in Tumor Therapy. Int. J. Pept. Res. Ther. 2023, 29, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javid, H.; Oryani, M.A.; Rezagholinejad, N.; Esparham, A.; Tajaldini, M.; Karimi-Shahri, M. RGD peptide in cancer targeting: Benefits, challenges, solutions, and possible integrin-RGD interactions. Cancer Med. 2024, 13, e6800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, X.-B.; Ma, Z.; Lai, R.; Lavasanifar, A. The Therapeutic Response to Multifunctional Polymeric Nano-Conjugates in the Targeted Cellular and Subcellular Delivery of Doxorubicin. Biomaterials 2010, 31, 757–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhen, Z.; Tang, W.; Chen, H.; Lin, X.; Todd, T.; Wang, G.; Cowger, T.; Chen, X.; Xie, J. RGD-Modified Apoferritin Nanoparticles for Efficient Drug Delivery to Tumors. ACS Nano 2013, 7, 4830–4837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anders, J.; Cortez, A.G.; Yu, J.; Majumdar, S.; Bhise, A.; Hobbs, R.F.; Nedrwo, J.R. Evaluation of Targeting αVβ3 in Breast Cancers Using RGD Peptide-Based Agents. Nuclear Med. Biol. 2024, 128–129, 108880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sujin, K.; Lee, S.; Park, S. iRGD Peptide as a Tumor-Penetrating Enhancer for Tumor-Targeted Drug Delivery. Polymers 2020, 12, 1906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Li, N.; Li, Y.; Hou, S.; Zhang, W.; Meng, Z.; Wang, S.; Jia, Q.; Tan, J.; Wang, R.; et al. Engineering a HEK-293T exosome-based delivery platform for efficient tumor-targeting chemotherapy/internal irradiation combination therapy. J. Nanobiotech. 2022, 20, 247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meichen, Z.; Xu, H. Peptide-Assembled Nanoparticles Targeting Tumor Cells and Tumor Microenvironment for Cancer Therapy. Front. Chem. 2023, 11, 1115495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Timur, S.S.; Yöyen-Ermiş, D.; Esendağlı, G.; Yonat, S.; Horzum, U.; Esendağlı, G.; Gürsoy, R.N. Efficacy of a novel LyP-1-containing self-microemulsifying drug delivery system (SMEDDS) for active targeting to breast cancer. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2019, 136, 138–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, Z.; Cai, L.; Li, C. Characterization and targeting ability evaluation of cell-penetrating peptide LyP-1 modified alginate-based nanoparticles. RSC Adv. 2020, 10, 32443–32449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adeyemi, S.A.; Choonara, Y.A. In Vitro and In Vivo Evaluation of a Cyclic LyP-1-Modified Nanosystem for Targeted Endostatin Delivery in a KYSE-30 Cell Xenograft Athymic Nude Mice Model. Pharmaceuticals 2022, 15, 353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, G.; Yu, X.; Jun, C.; Yang, F. LyP-1-conjugated nanoparticles for targeting drug delivery to lymphatic metastatic tumors. Int. J. Pharm. 2009, 385, 150–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Li, R.; Dong, Y.; You, C.; Huang, S.; Li, X.; Wang, F.; Zhang, Y. tLyP-1 Peptide Functionalized Human H Chain Ferritin for Targeted Delivery of Paclitaxel. Int. J. Nanomed. 2021, 16, 789–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isha, G.; Thakur, A.; Zhang, K.; Thakur, S.; Hu, X.; Xu, Z.; Kumar, G.; Jaganathan, R.; Iyaswamy, A.; Li, M.; et al. Peptide-Conjugated Vascular Endothelial Extracellular Vesicles Encapsulating Vinorelbine for Lung Cancer Targeted Therapeutics. Nanomaterials 2024, 14, 1669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Cao, Z.; Liu, N.; Gao, G.; Du, M.; Wang, Y.; Cheng, B.; Zhu, M.; Jia, B.; Pan, L.; et al. Kill two birds with one stone: Engineered exosome-mediated delivery of cholesterol modified YY1-siRNA enhances chemoradiotherapy sensitivity of glioblastoma. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 975291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, H.-Y.; Hsieh, C.-H.; Lin, P.-H.; Chen, Y.-T.; Hsu, D.S.-S.; Tai, S.-K.; Chu, P.-Y.; Yang, M.-H. Snail-regulated exosomal microRNA-21 suppresses NLRP3 inflammasome activity to enhance cisplatin resistance. J. Immunother. Cancer 2022, 10, e004832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borrego-Soto, G.; Ortiz-López, R.; Rojas-Martínez, A. Ionizing radiation-induced DNA injury and damage detection in patients with breast cancer. Genet. Mol. Biol. 2015, 38, 420–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eychenne, R.; Bouvry, C.; Bourgeois, M.; Loyer, P.; Benoist, E.; Lepareur, N. Overview of Radiolabeled Somatostatin Analogs for Cancer Imaging and Therapy. Molecules 2020, 25, 4012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trautwein, N.F.; Schwenck, J.; Jacoby, J.; Reischl, G.; Fiz, F.; Zender, L.; Dittmann, H.; Hinterleitner, M.; la Fougère, C. Long-term prognostic factors for PRRT in neuroendocrine tumors. Front. Med. 2023, 10, 1169970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofland, J.; Brabander, T.; Verburg, F.A.; Feelders, R.A.; de Herder, W.W. Peptide Receptor Radionuclide Therapy. J. Clin. End. Metab. 2022, 107, 3199–3208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strosberg, J.R.; Al-Toubah, T.; El-Haddad, G.; Lagunes, D.R.; Bodei, L. Sequencing of Somatostatin-Receptor-Based Therapies in Neuroendocrine Tumor Patients. J. Nucl. Med. 2024, 65, 340–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baum, R.P.; Schuchardt, C.; Singh, A.; Chantadisai, M.; Robiller, F.C.; Zhang, J.; Mueller, D.; Eismant, A.; Almaguel, F.; Zboralski, D.; et al. Feasibility, Biodistribution, and Preliminary Dosimetry in Peptide-Targeted Radionuclide Therapy of Diverse Adenocarcinomas Using 177Lu-FAP-2286: First-in-Humans Results. J. Nucl. Med. 2022, 63, 415–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patell, K.; Kurian, M.; Garcia, J.A.; Mendiratta, P.; Barata, P.C.; Jia, A.Y.; Spratt, D.E.; Brown, J.R. Lutetium-177 PSMA for the treatment of metastatic castrate resistant prostate cancer: A systematic review. Expert Rev. Anticancer Ther. 2023, 23, 731–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Entezari, P.; Gabr, A.; Salem, R.; Lewandowski, R.J. Yttrium-90 for colorectal liver metastasis—The promising role of radiation segmentectomy as an alternative local cure. Int. J. Hyperth. 2022, 39, 620–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otte, A.; Mueller-Brand, J.; Dellas, S.; Nitzsche, E.U.; Herrmann, R.; Maecke, H.R. Yttrium-90 labeled somatostatin-analogue for cancer treatment. Lancet 1998, 351, 417–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Otte, A.; Herrmann, R.; Heppeler, A.; Behe, M.; Jermann, E.; Powell, P.; Maecke, H.R.; Muller, J. Yttrium-90 DOTATOC: First clinical results. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. 1999, 26, 1439–1447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinjamuri, S.; Gilbert, T.M.; Banks, M.; McKane, G.; Maltby, P.; Poston, G.; Weissman, H.; Palmer, D.H.; Vora, J.; Pritchard, D.M.; et al. Peptide Receptor Radionuclide Therapy With 90Y-DOTATATE/90Y-DOTATOC in Patients with Progressive Metastatic Neuroendocrine Tumours: Assessment of Response, Survival and Toxicity. Br. J. Cancer 2013, 108, 1440–1448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Virgolini, I.; Britton, K.; Buscombe, J.; Moncayo, R.; Paganelli, G.; Riva, P. In- and Y-DOTA-lanreotide: Results and implications of the MAURITIUS trial. Semin. Nucl. Med. 2002, 32, 148–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strosberg, J.; El-Haddad, G.; Wolin, E.; Hendifar, A.; Yao, J.; Chasen, B.; Mittra, E.; Kunz, P.L.; Kulke, M.H.; Jacene, H.; et al. NETTER-1 Trial Investigators. Phase 3 Trial of 177Lu-Dotatate for Midgut Neuroendocrine Tumors. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 376, 125–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoogenkamp, D.S.; de Wit-van der Veen, L.J.; Huizing, D.M.V.; Tesselaar, M.E.T.; van Leeuwaarde, R.S.; Stokkel, M.P.M.; Lam, M.G.E.H.; Braat, A.J.A.T. Advances in Radionuclide Therapies for Patients with Neuro-endocrine Tumors. Curr. Oncol. Rep. 2024, 26, 551–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merola, E.; Grana, C.M. Peptide Receptor Radionuclide Therapy (PRRT): Innovations and Improvements. Cancers 2023, 15, 2975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alas, M.; Saghaeidehkordi, A.; Kaur, K. Peptide-Drug Conjugates with Different Linkers for Cancer Therapy. J. Med. Chem. 2021, 64, 216–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, B.M.; Iegre, J.; O’Donovan, D.H.; Halvarsson, M.O.; Spring, D.R. Peptides as a platform for targeted therapeutics for cancer: Peptide–drug conjugates (PDCs). Chem. Soc. Rev. 2021, 50, 1480–1494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balogh, B.; Ivánczi, M.; Nizami, B.; Beke-Somfai, T.; Mándity, I.M. ConjuPepDB: A database of peptide-drug conjugates. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021, 49, D1102–D1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripodi, A.A.P.; Tóth, S.; Enyedi, K.N.; Scholosser, G.; Szakács, G.; Mező, G. Development of novel cyclic NGR peptide–daunomycin conjugates with dual targeting property. J. Org. Chem. 2018, 14, 911–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Ding, Z.; Li, X.; Wei, H.; Chen, Y. Research Progress of Radiolabeled Asn-GlyArg (NGR) Peptides for Imaging and Therapy. Mol. Imaging 2020, 19, 1536012120934957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziaei, E.; de Paiva, I.M.; Yao, S.-J.; Sarrami, N.; Mehinrad, P.; Lai, J.; Lavasanifar, A.; Kaur, K. Peptide-Drug Conjugate Targeting Keratin 1 Inhibits Triple-Negative Breast Cancer in Mice. Mol. Pharmacol. 2023, 20, 3570–3577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, K.; Song, X.; Yang, L.; Li, L.; Wan, Z.; Sun, X.; Gong, T.; Lin, Q.; Zhang, Z. Enhanced antitumor and anti-metastasis efficacy against aggressive breast cancer with a fibronectin-targeting liposomal doxorubicin. J. Control. Release 2018, 271, 21–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delavari, B.; Bigdeli, B.; Khazeni, S.; Varamini, P. Nanodiamond-Protein hybrid Nanoparticles: LHRH receptor targeted and co-delivery of doxorubicin and dasatinib for triple negative breast cancer therapy. Int. J. Pharm. 2025, 675, 125544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Emons, G.; Gorchev, G.; Harter, P.; Wimberger, P.; Stähle, A.; Hanker, L.; Hilpert, F.; Beckmann, M.W.; Dall, P.; Gründker, C.; et al. Efficacy and safety of AEZS-108 (LHRH agonist linked to doxorubicin) in women with advanced or recurrent endometrial cancer expressing LHRH receptors: A multicenter phase 2 trial (AGO-GYN5). Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 2014, 24, 260–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Available online: https://www.clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT01767155?tab=results#outcome-measures (accessed on 5 December 2025).

- Xie, M.-H.; Fu, Z.-L.; Hua, A.-L.; Zhou, J.-F.; Chen, Q.; Li, J.-B.; Yao, S.; Cai, X.-J.; Ge, M.; Zhou, L.; et al. A new core-shell-type nanoparticle loaded with paclitaxel/norcantharidin and modified with APRPG enhances anti-tumor effects in hepatocellular carcinoma. Front. Oncol. 2022, 12, 932156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, C.; Yu, L.; Miao, Y.; Liu, X.; Yu, Z.; Wei, M. Peptide-drug conjugates (PDCs): A novel trend of research and development on targeted therapy, hype or hope? Acta Pharm. Sin. B 2023, 13, 498–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coburn, F.; Nsereko, Y.; Armstrong, A.; Musaimi, O.A. Peptide inhibitors: Breaking cancer code. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2025, 297, 117961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wintgens, J.P.; Wichert, S.P.; Popovic, L.; Rossner, M.J.; Wehr, M.C. Monitoring activities of receptor tyrosine kinases using a universal adapter in genetically encoded split TEV assays. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 2019, 76, 1185–1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, C.; Wei, Y.; Wei, X. AXL receptor tyrosine kinase as a promising anti-cancer approach: Functions, molecular mechanisms and clinical applications. Mol. Cancer 2019, 18, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amato, J.G.; Erinn, B.R.; Jennifer, R.C.; Douglas, J.; Mihalis, K.; Katherine, F.; Yu, M.; Susan, H. Modified AXL Peptides and Their Use in Inhibition of AXL Signaling in Anti-Metastatic Therapy. HK1256071B, 27 November 2018. Available online: https://patents.google.com/patent/HK1256071B/en (accessed on 2 October 2025).

- Amato, J.G.; Erinn, B.R.; Jennifer, R.C.; Douglas, J.; Mihalis, K.; Katherine, F.; Yu, M.; Susan, H. Modified AXL Peptides and Their Use in Inhibition of AXL Signaling in Anti-Metastatic Therapy. US9822347B2, 12 December 2013. Available online: https://patents.google.com/patent/US9822347B2/en#:~:text=translated%20from.%20Compositions%20and%20methods%20are%20provided,MER%20or%20Tyro3%20and%20its%20ligand%20GAS6 (accessed on 2 October 2025).

- William, A.D.; Flanagan, J.U. Inhibitors of Discoidin Domain Receptor (DDR) Kinases for Cancer and Inflammation. Biomolecules 2021, 11, 1671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, D.; Yeom, J.-H.; Lee, B.; Lee, K.; Bae, J.; Rhee, S. Inhibition of discoidin domain receptor 2-mediated lung cancer cells progression by gold nanoparticle-aptamer-assisted delivery of peptides containing transmembrane-juxtamembrane 1/2 domain. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Comm. 2015, 464, 392–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borza, C.M.; Bolas, G.; Zhang, X.; Browning Monroe, M.B.; Zhang, M.Z.; Meiler, J.; Skwark, M.J.; Harris, R.C.; Lapierre, L.A.; Goldenring, J.R.; et al. The Collagen Receptor Discoidin Domain Receptor 1b Enhances Integrin β1-Mediated Cell Migration by Interacting with Talin and Promoting Rac1 Activation. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2022, 10, 836797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carafoli, F.; Bihan, D.; Stathopoulos, S.; Konitsiotis, A.D.; Kvansakul, M.; Farndale, R.W.; Leitinger, B.; Hohenester, E. Crystallographic Insight into Collagen Recognition by Discoidin Domain Receptor 2. Structure 2009, 17, 1573–1581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosselot, C.; Li, Y.; Wang, P.; Alvarsson, A.; Beliard, K.; Lu, G.; Kang, R.; Li, R.; Liu, H.; Gillespie, V.; et al. Harmine and exendin-4 combination therapy safely expands human β cell mass in vivo in a mouse xenograft system. Sci. Transl. Med. 2024, 16, eadg3456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, R.K.; Shukla, S.; Ramanand, S.G.; Somnay, V.; Bridges, A.J.; Lawrence, T.S.; Nyati, M.K. Disruptin, a cell-penetrating peptide degrader of EGFR: Cell-Penetrating Peptide in Cancer Therapy. Transl. Oncol. 2021, 14, 101140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahsan, A.; Ramanand, S.G.; Bergin, I.L.; Zhao, L.; Whitehead, C.E.; Rehemtulla, A.; Ray, D.; Pratt, W.B.; Lawrence, T.S.; Nyati, M.K. Efficacy of an EGFR-specific peptide against EGFR-dependent cancer cell lines and tumor xenografts. Neoplasia 2014, 16, 105–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Zhao, C.; Wang, L.; Cao, X.; Li, J.; Huang, R.; Lao, Q.; Yu, H.; Li, Y.; Du, H.; et al. A VEGFR1 antagonistic peptide inhibits tumor growth and metastasis through VEGFR1-PI3K-AKT signaling pathway inhibition. Am. J. Cancer Res. 2015, 5, 3149–3161. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Farzaneh Behelgardi, M.; Zahri, S.; Mashayekhi, F.; Mansouri, K.; Asghari, S.M. A peptide mimicking the binding sites of VEGF-A and VEGF-B inhibits VEGFR-1/-2 driven angiogenesis, tumor growth and metastasis. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 17924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.S.; Tocheny, C.E.; Shaw, L.M. The Insulin-like Growth Factor Signaling Pathway in Breast Cancer: An Elusive Therapeutic Target. Life 2022, 12, 1992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iams, W.T.; Lovly, C.M. Molecular Pathways: Clinical Applications and Future Direction of Insulin-like Growth Factor-1 Receptor Pathway Blockade. Clin. Cancer Res. 2015, 21, 4270–4277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamad, N.-V.; Ima-Nirwana, S.; Chin, K.-Y. The Skeletal Effects of Gonadotropin-Releasing Hormone Antagonists: A Concise Review. Endocr. Metab. Immune Disord. Drug Targets 2021, 21, 1713–1720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Connolly, R.M.; Carducci, M.A.; Antonarakis, E.S. Use of androgen deprivation therapy in prostate cancer: Indications and prevalence. Asian J. Androl. 2012, 14, 177–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonadotropin Releasing Hormone (GnRH) Analogues. In LiverTox: Clinical and Research Information on Drug-Induced Liver Injury; National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases: Bethesda, MD, USA, 2012.

- Zhao, J.; Chen, J.; Sun, G.; Shen, P.; Zeng, H. Luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone receptor agonists and antagonists in prostate cancer: Effects on long-term survival and combined therapy with next-generation hormonal agents. Cancer Biol. Med. 2024, 21, 1012–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tombal, B.; Collin, S.; Morgans, A.K.; Hunsche, E.; Brown, B.; Zhu, E.; Bossi, A.; Shore, N. Impact of Relugolix Versus Leuprolide on the Quality of Life of Men with Advanced Prostate Cancer: Results from the Phase 3 HERO Study. Eur. Urol. 2023, 84, 579–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perlmutter, M.A.; Lepor, H. Androgen deprivation therapy in the treatment of advanced prostate cancer. Rev. Urol. 2007, 9, S3–S8. [Google Scholar]

- Patel, H.K.; Bihani, T. Selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERMs) and selective estrogen receptor degraders (SERDs) in cancer treatment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2018, 186, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, J.A.; Mesfin, F.B.; Andersen, T.T.; Gierthy, J.F.; Jacobson, H.I. A peptide derived from α-fetoprotein prevents the growth of estrogen-dependent human breast cancers sensitive and resistant to tamoxifen. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2002, 99, 2211–2215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Speltz, T.E.; Danes, J.M.; Stender, J.D.; Frasor, J.; Moore, T.W. A Cell-Permeable Stapled Peptide Inhibitor of the Estrogen Receptor/Coactivator Interaction. ACS Chem. Biol. 2018, 13, 676–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joufrre, B.; Acramel, A.; Belnou, M.; Santolla, M.F.; Talia, M.; Lappano, R.; Nemati, F.; Decaudin, D.; Khemtemourian, L.; Lui, W.-Q.; et al. Identification of a human estrogen receptor α tetrapeptidic fragment with dual antiproliferative and anti-nociceptive action. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lappano, R.; Mallet, C.; Rizzuti, B.; Grande, F.; Galli, G.R.; Byrne, C.; Broutin, I.; Boudieu, L.; Eschalier, A.; Jacquot, Y.; et al. The Peptide ERα17p Is a GPER Inverse Agonist that Exerts Antiproliferative Effects in Breast Cancer Cells. Cells 2019, 8, 590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wander, S.A.; Cohen, O.; Gong, X.; Johnson, G.N.; Buendia-Buendia, J.E.; Lloyd, M.R.; Kim, D.; Luo, F.; Mao, P.; Helvie, K.; et al. The Genomic Landscape of Intrinsic and Acquired Resistance to Cyclin-Dependent Kinase 4/6 Inhibitors in Patients with Hormone Receptor-Positive Metastatic Breast Cancer. Cancer Discov. 2020, 10, 1174–1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamza, S.; Garanina, E.E.; Alsaadi, M.; Khaiboullina, S.F.; Tezcan, G. Blocking the Hormone Receptors Modulates NLRP3 in LPS-Primed Breast Cancer Cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 4846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadal-Bufí, F.; Chan, L.Y.; Mohammad, H.H.; Mason, J.M.; Salomon, C.; Lai, A.; Thompson, E.W.; Craik, D.J.; Kaas, Q.; Henriques, S.T. Peptide-based LDH5 inhibitors enter cancer cells and impair proliferation. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 2022, 79, 606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, N.; Liang, Y.; Yang, P.; Jiang, L. Flurbiprofen inhibits cell proliferation in thyroid cancer through interrupting HIP1R-induced endocytosis of PTN. Eur. J. Med. Res. 2022, 27, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Yao, H.; Li, C.; Shi, H.; Lan, J.; Li, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Liang, L.; Fang, J.-Y.; Xu, J. HIP1R targets PD-L1 to lysosomal degradation to alter T cell-mediated cytotoxicity. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2019, 15, 42–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Zhan, M.; Liu, J.; Liu, Z.; Shen, M.; Yang, F.; Kang, Y.; Yin, F.; Li, Z. Structure-Based Design, Optimization, and Evaluation of Potent Stabilized Peptide Inhibitors Disrupting MTDH and SND1 Interaction. J. Med. Chem. 2022, 65, 12188–12199, Erratum in J. Med. Chem. 2023, 66, 7668. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jmedchem.3c00892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, H.; Zhan, M.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, J.; Wang, R.; An, Y.; Gao, Z.; Jiang, L.; Xing, Y.; Kang, Y.; et al. Intracellular Delivery of Stabilized Peptide Blocking MTDH-SND1 Interaction for Breast Cancer Suppression. JACS Au 2023, 4, 139–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Zhou, W.; Zhou, B.; Liu, L.; Chern, T.R.; Chinnaswamy, K.; Lu, J.; Bernard, D.; Yang, C.Y.; Li, S.; et al. High-Affinity Peptidomimetic Inhibitors of the DCN1-UBC12 Protein-Protein Interaction. J. Med. Chem. 2018, 61, 1934–1950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, X.; Li, D.; Kottur, J.; Shen, Y.; Kim, S.H.; Park, K.-S.; Tsai, Y.-H.; Gong, W.; Wng, J.; Suzuki, K.; et al. A selective WDR5 degrader inhibits acute myeloid leukemia in patient-derived mouse models. Sci. Transl. Med. 2021, 13, eabbj1578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luan, X.; Wu, Y.; Shen, Y.-W.; Zhang, H.; Zhou, Y.-D.; Chen, H.-Z.; Nagle, D.G.; Zhang, W.-D. Cytotoxic and antitumor peptides as novel chemotherapeutics. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2021, 38, 7–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kourie, J.I.; Shorthouse, A.A. Properties of cytotoxic peptide-formed ion channels. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2000, 278, C1063–C1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haque, S.; Hussain, A.; Joshi, H.; Sharma, U.; Sharma, B.; Aggarwal, D.; Rani, I.; Ramniwas, S.; Gupta, M.; Tuli, H.S. Melittin: A possible regulator of cancer proliferation in preclinical cell culture and animal models. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 2023, 149, 17709–17726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pandey, P.; Khan, F.; Khan, M.A.; Kumar, R.; Upadhyay, T.K. An Updated Review Summarizing the Anticancer Efficacy of Melittin from Bee Venom in Several Models of Human Cancers. Nutrients 2023, 15, 3111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duffy, C.; Sorolla, A.; Wang, E.; Golden, E.; Woodward, E.; Davern, K.; Ho, D.; Johnstone, E.; Pfleger, K.; Redfern, A.; et al. Honeybee venom and melittin suppress growth factor receptor activation in HER2-enriched and triple-negative breast cancer. NPJ Precis. Oncol. 2020, 4, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Zhao, B.; Huang, C.; Meng, X.-M.; Bian, E.-B.; Li, J. Melittin Restores PTEN Expression by Down-Regulating HDAC2 in Human Hepatocelluar Carcinoma HepG2 Cells. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e95520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, J.; Liu, S.; Ai, M.; Wang, Z.; Wang, D.; Li, X.; Hu, K.; Gao, X.; Yang, Y. A novel melittin nano-liposome exerted excellent anti-hepatocellular carcinoma efficacy with better biological safety. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2017, 10, 71, Erratum in J. Hematol. Oncol. 2022, 15, 130. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13045-022-01277-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, H.; Lei, M. 124P Melittin inhibits the growth of hepatocellular carcinoma Huh7 cells by downregulating LARS2 and ZNF19. Eur. Soc. Med. Oncol. 2025, 10, 105477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Chen, W.-Q.; Zhang, S.-Q.; Bai, J.-X.; Lau, C.-L.; Sze, S.C.-W.; Yung, K.K.-L.; Ko, J.K.-S. The human cathelicidin peptide LL-37 inhibits pancreatic cancer growth by suppressing autophagy and reprogramming of the tumor immune microenvironment. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 906625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Zou, X.; Qi, G.; Tang, Y.; Guo, Y.; Si, J.; Liang, L. Roles and Mechanisms of Human Cathelicidin LL-37 in Cancer. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 2018, 47, 1060–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anghel, R.; Jitaru, D.; Bădescu, L.; Bădescu, M.; Ciocoiu, M. The cytotoxic effect of magainin II on the MDA-MB-231 and M14K tumour cell lines. BioMed Res. Int. 2013, 2013, 831709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehmann, J.; Retz, M.; Sidhu, S.S.; Suttmann, H.; Sell, M.; Paulsen, F.; Harder, J.; Unteregger, G. Antitumor Activity of the Antimicrobial Peptide Magainin II against Bladder Cancer Cell Lines. Eur. Urol. 2006, 50, 141–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Yang, H.; Cheng, J.; Lu, X. Penetratin-Mediated Delivery Enhances the Antitumor Activity of the Cationic Antimicrobial Peptide Magainin II. Cancer Biother. Radiopharm. 2013, 28, 289–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, M.A.; Maloy, W.L.; Zasloff, M.; Jacob, L.S. Anticancer efficacy of Magainin2 and analogue peptides. Cancer Res. 1993, 53, 3052–3057. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Pandurangi, R.; Karwa, A.; Sagaram, U.S.; Henzler-Wildman, K.; Shah, D. Medicago Sativa Defensin1 as a tumor sensitizer for improving chemotherapy: Translation from antifungal agent to a potential anti-cancer agent. Front. Oncol. 2023, 13, 1141755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amaral, V.S.G.D.; Santos, S.A.C.S.; de Andrade, P.C.; Nowatzki, J.; Júnior, N.S.; de Medeiros, L.N.; Gitirana, L.B.; Pascutti, P.G.; Almeida, V.H.; Monteiro, R.Q.; et al. Pisum sativum Defensin 1 Eradicates Mouse Metastatic Lung Nodules from B16F10 Melanoma Cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 2662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baxter, A.; Poon, I.; Hulett, M. The plant defensin NaD1 induces tumor cell death via a non-apoptotic, membranolytic process. Cell Death Discov. 2017, 3, 16102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandurangi, R.; Sekar, T.; Paulmurugan, R. Restoration of the Lost Human Beta Defensin-1 Protein in Cancer as a Strategy to Improve the Efficacy of Chemotherapy. J. Med. Chem. 2024, 67, 14200–14209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, C.Q.; Arnold, R.S.; Hsieh, C.L.; Dorin, J.R.; Lian, F.; Li, Z.; Petros, J.A. Discovery and mechanisms of host defense to oncogenesis: Targeting the β-defensin-1 peptide as a natural tumor inhibitor. Cancer Biol. Ther. 2019, 20, 774–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adyns, L.; Proost, P.; Struyf, S. Role of defensins in tumor biology. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 5268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, C.A.; Markovic-Lipkovski, J.; Klatt, T.; Gamper, J.; Schwarz, G.; Beck, H.; Deeg, M.; Kalbacher, H.; Widmann, S.; Wessels, J.T.; et al. Human alpha-defensins HNPs-1, -2, and -3 in renal cell carcinoma: Influences on tumor cell proliferation. Am. J. Pathol. 2002, 160, 1311–1324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Semple, F.; Dorin, J.R. β-Defensins: Multifunctional modulators of infection, inflammation and more? J. Innate Immun. 2012, 4, 337–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagib, M.; Sayed, A.M.; Korany, A.H.; Abdelkader, K.; Shari, F.H.; Mackay, W.G.; Rateb, M.E. Human Defensins: Structure, Function, and Potential as Therapeutic Antimicrobial Agents with Highlights Against SARS CoV-2. Probiotics Antimicrob. Proteins 2025, 17, 1563–1583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Wan, L.; Zhang, J.; Liu, C.; Sun, H. Effect of BMAP-28 on human thyroid cancer TT cells is mediated by inducing apoptosis. Oncol. Lett. 2015, 10, 2620–2626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, M.-C.; Wang, E.Y.; Lai, T.W. TAT peptide at treatment-level concentrations crossed brain endothelial cell monolayer independent of receptor-mediated endocytosis or peptide-inflicted disruption. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0292681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Lu, H.; Zhao, Y. Development of an autophagy activator from Class III PI3K complexes, Tat-BECN1 peptide: Mechanisms and applications. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2022, 10, 851166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- di Polidoro, A.C.; Cafarchio, A.; Vecchione, D.; Donato, P.; de Nola, F.; Torino, E. Revealing Angiopep-2/LRP1 Molecular Interaction Optimal Delivery to Glioblastoma (GBM). Molecules 2022, 27, 6696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumthekar, P.; Tang, S.-C.; Brenner, A.J.; Kesari, S.; Piccioni, D.E.; Anders, C.; Carrillo, J.; Chalasani, P.; Kabos, P.; Puhalla, S.; et al. ANG1005, a Brain-Penetrating Peptide-Drug Conjugate, Shows Activity in Patients with Breast Cancer with Leptomeningeal Carcinomatosis and Recurrent Brain Metastases. Clin. Cancer Res. 2020, 26, 2789–2799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dmello, C.; Brenner, A.; Piccioni, D.; Wen, P.Y.; Drappatz, J.; Mrugala, M.; Lewis, L.D.; Schiff, D.; Fadul, C.E.; Chamberlain, M.; et al. Phase II trial of blood-brain barrier permeable peptide-paclitaxel conjugate ANG1005 in patients with recurrent high-grade glioma. Neuro-Oncol. Adv. 2024, 6, vdae186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, Y.; Liu, J.; Bai, Y.; Zheng, C.; Wang, D. Peptides as Versatile Regulators in Cancer Immunotherapy: Recent Advances, Challenges, and Future Prospects. Pharmaceutics 2025, 17, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anilkumar, A.S.; Thomas, S.M.; Veerabathiran, R. Next-generation cancer vaccines: Targeting cryptic and non-canonical antigens for precision immunotherapy. Explor. Target. Antitumor Ther. 2025, 6, 1002338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, D.; Liu, L.; Li, X.; Wang, S.; Wu, G.; Che, X. Advancements and Challenges in Peptide-Based Cancer Vaccination: A Multidisciplinary Perspective. Vaccines 2024, 12, 950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamley, I.W. Peptides for Vaccine Development. ACS Appl. Bio Mater. 2022, 5, 905–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, M.; Whi, A.; Sharma, P.; Nagpal, P.; Raina, N.; Kaurav, M.; Bhattacharya, J.; Rodrigues Oliveuram, S.M.; Dolma, K.G.; Paul, A.L.; et al. Recent Advances in Cancer Vaccines: Challenges, Achievements, and Futuristic Prospects. Vaccines 2022, 10, 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Tang, H.; Li, L.; Wang, X.; Yu, Z.; Li, J. Peptide-based therapeutic cancer vaccine: Current trends in clinical application. Cell Prolif. 2021, 54, e13025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd-Aziz, N.; Poh, C.L. Development of Peptide-Based Vaccines for Cancer. J. Oncol. 2022, 2022, 9749363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hongo, F.; Ueda, T.; Takasha, N.; Tamada, S.; Nakatani, T.; Miki, T.; Ukimura, O. Phase I/II study of multipeptide cancer vaccine IMA901 after single-dose cyclophosphamide in Japanese patients with advanced renal cell cancer with long-term follow up. Int. J. Urol. 2023, 30, 176–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Shea, A.E.; Clifton, G.T.; Qiao, N.; Heckman-Stoddard, B.M.; Wojtowicz, M.; Dimond, E.; Bedrosian, I.; Weber, D.; Garber, J.E.; Husband, A.; et al. Phase II Trial of Nelipepimut-S Peptide Vaccine in Women with Ductal Carcinoma In Situ. Cancer Prev. Res. 2023, 16, 333–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, Z.; Zhou, W.; Weng, J.; Feng, H.; Liang, P.; Li, Y.; Shi, F. Application of HER2 peptide vaccines in patients with breast cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancer Cell Int. 2021, 21, 489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mittendorf, E.A.; Ardavanis, A.; Litton, J.K.; Shumway, N.M.; Hale, D.F.; Murray, J.L.; Perez, S.A.; Ponniah, S.; Baxevanis, C.N.; Papamichail, M.; et al. Primary analysis of a prospective, randomized, single-blinded phase II trial evaluating the HER2 peptide GP2 vaccine in breast cancer patients to prevent recurrence. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 66192–66201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneble, E.J.; Perez, S.A.; Murray, J.L.; Berry, J.S.; Trappey, A.F.; Vreeland, T.J.; Hale, D.F.; Mittendorf, E.A. Primary analysis of the prospective, randomized, phase II trial of GP2+GM-CSF vaccine versus GM-CSF alone administered in the adjuvant setting to high-risk breast cancer patients. J. Clin. Oncol. 2014, 32, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clifton, G.; Litton, J.K.; Arrington, K.; Ponniah, S.; Ibrahim, N.K.; Gall, V.; Alatrash, G.; Peoples, G.E.; Mittendorf, E.A. Results of a Phase Ib Trial of Combination Immunotherapy with a CD8+ T Cell Eliciting Vaccine and Trastuzumab in Breast Cancer Patients. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2017, 24, 2161–2167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, T.A.; Mittendorf, E.A.; Hale, D.F.; Myers, J.W.; Peace, K.M.; Jackson, D.O.; Greene, J.M.; Vreeland, T.J.; Clifton, G.T.; Ardavanis, A.; et al. Prospective, randomized, single-blinded, multi-center phase II trial of two HER2 peptide vaccines, GP2 and AE37, in breast cancer patients to prevent recurrence. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2020, 181, 391–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- CenterWatch Study. Available online: https://www.centerwatch.com/clinical-trials/listings/NCT05232916/phase-3-study-to-evaluate-the-efficacy-and-safety-of-her2-neu-peptide-glsi-100-gp2-gm-csf-in-her2neu-positive-subjects?utm= (accessed on 7 October 2025).

- Kim, Y.; Lee, D.; Go, C.; Yang, J.; Kang, D.; Kang, J.S. GV1001 interacts with androgen receptor to inhibit prostate cell proliferation in benign prostatic hyperplasia by regulating expression of molecules related to epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Aging 2021, 13, 3202–3217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunsvig, P.F.; Kyte, J.A.; Kersten, C.; Sundstrom, S.; Moller, M.; Nyakas, M.; Hansen, G.L.; Gaudernack, G.; Aamdal, S. Telomerase Peptide Vaccination in NSCLC: A Phase II Trial in Stage III Patients Vaccinated after Chemoradiotherapy and an 8-Year Update on a Phase I/II Trial. Clin. Cancer Res. 2011, 17, 6847–6857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negrini, S.; De Palma, R.; Filaci, G. Anti-Cancer Immunotherapies Targeting Telomerase. Cancers 2020, 1, 2260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.H.; Cho, Y.R.; Ahn, E.K.; Kim, S.; Han, S.; Kim, S.J.; Bae, G.U.; Oh, J.S.; Seo, D.W. A novel telomerase-derived peptide GV1001-mediated inhibition of angiogenesis: Regulation of VEGF/VEGFR-2 signaling pathways. Transl. Oncol. 2022, 26, 101546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vahidi, S.; Zabeti Touchaei, A. Telomerase-based vaccines: A promising frontier in cancer immunotherapy. Cancer Cell Int. 2024, 24, 421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Shin, K.; Kim, S.; Shon, W.; Kim, R.H.; Park, N.; Kang, M.K. hTERT peptide fragment GV1001 demonstrates radioprotective and antifibrotic effects through suppression of TGF-β signaling. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2018, 41, 3211–3220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, J.H.; Kim, Y.T.; Choi, H.S.; Kim, H.G.; Lee, H.S.; Choi, Y.W.; Kim, D.U.; Lee, K.H.; Lim, E.J.; Han, J.-H.; et al. Efficacy of GV1001 with gemcitabine/capecitabine in previously untreated patients with advanced pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma having high serum eotaxin levels (KG4/2015): An open-label, randomised, Phase 3 trial. Br. J. Cancer 2024, 130, 43–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Middleton, G.; Silcocks, P.; Cox, T.; Valle, J.; Wadsley, J.; Propper, D.; Coxon, F.; Ross, P.; Madhusudan, S.; Roques, T.; et al. Gemcitabine and capecitabine with or without telomerase peptide vaccine GV1001 in patients with locally advanced or metastatic pancreatic cancer (TeloVac): An open-label, randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2014, 15, 829–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.Y.; Yang, D.W.; Kim, S.; Choi, J.G. Retrospective Analysis of the Clinical Characteristics of Patients with Breast Cancer Treated with Telomerase Peptide Immunotherapy Combined with Cytotoxic Chemotherapy. Breast Cancer 2023, 15, 955–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.J.; Dougan, S.K.; Dougan, M. Immune mechanisms of toxicity from checkpoint inhibitors. Trends Cancer 2023, 9, 543–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cook, S.L.; Amin, M.A.; Bari, S.; Poonnen, P.J.; Khasraw, M.; Johnson, M.O. Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors in Geriatric Oncology. Curr. Oncol. Rep. 2024, 26, 562–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagasaki, J.; Ishino, T.; Togashi, T. Mechanisms of resistance to immune checkpoint inhibitors. Cancer Sci. 2022, 113, 3303–3312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wabitsch, S.; Tandon, M.; Ruf, B.; Zhang, Q.; McCallen, J.D.; McVey, J.C.; Ma, C.; Green, B.L.; Diggs, L.P.; Heinrich, B.; et al. Anti-PD-1 in Combination with Trametinib Suppresses Tumor Growth and Improves Survival of Intrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma in Mice. Cell. Mol. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2021, 12, 1166–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, H.; Zhao, Z.; Zhang, L.; Li, Y.; Jain, A.; Barve, A.; Jun, W.; Liu, Y.; Fetse, J.; Cheng, K. Discovery of low-molecular weight anti-PD-L1 peptides for cancer immunotherapy. J. Immunother. Cancer 2019, 7, 270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, A.B.; Lin, B.; Liu, C.; Morshed, A.; Hu, J.; Xu, H. Design and Synthesis of A PD-1 Binding Peptide and Evaluation of Its Anti-Tumor Activity. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, T.; Zhao, C.; Wang, S.; Tao, D.; Ma, S.; Shou, C. The biologically functional identification of a novel TIM3-binding peptide P26 in vitro and in vivo. Cancer Chem. Pharmacol. 2020, 86, 783–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Wang, P.; Shi, G.; Tang, C.; Xue, H. AUNP-12 Near-Infrared Fluorescence Probes across NIR-I to NIR-II Enable In Vivo Detection of PD-1/PD-L1 Axis in the Tumor Microenvironment. Bioconjugate Chem. 2024, 35, 1064–1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podlesnykh, S.V.; Abramova, K.E.; Gordeeva, A.; Khlebnikov, A.I. Peptide Blocking CTLA-4 and B7-1 Interaction. Molecules 2021, 26, 253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, B.; Wang, X.; Guo, M.; Tzeng, C.-M. Therapeutic Peptides: Recent Advances in Discovery, Synthesis, and Clinical Translation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 5131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, W.; Maki, M.A.; Mani, V.R.M.; Kumar, P.V. Functional Peptides in Targeted Cancer Therapy: Mechanisms, Delivery Strategies, and Clinical Perspectives. Int. J. Pept. Res. Ther. 2025, 31, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chavda, V.P.; Solanki, H.K.; Davidson, M.; Apostolopoulos, V.; Bojarska, J. Peptide-Drug Conjugates: A New Hope for Cancer Management. Molecules 2022, 27, 7232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teleanu, R.I.; Preda, M.D.; Niculescu, A.G.; Vladâcenco, O.; Radu, C.I.; Grumezescu, A.M.; Teleanu, D.M. Current Strategies to Enhance Delivery of Drugs across the Blood-Brain Barrier. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, H.; Wang, J.; Chen, J.; Peng, Y.; Wang, X.; Chen, Y.; Kaplan, D.L.; Wang, Q. Challenges and opportunities in delivering oral peptides and proteins. Expert. Opin. Drug Deliv. 2023, 20, 1349–1369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Available online: https://www.genscript.com/recommended_peptide_purity.html#:~:text=Peptides%20with%20purity%20greater%20than,are%20excellent%20for%20quantitative%20analysis (accessed on 7 December 2025).

- Liu, M.; Svirskis, D.; Proft, T.; Loh, J.; Yin, N.; Li, H.; Zhou, Y.; Chen, S.; Song, L.; Chen, G.; et al. Progress in peptide and protein therapeutics: Challenges and strategies. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 2025, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, A.J.; de Campos, L.J.; Xing, H.; Conda-Sheridan, M. Peptide-based therapeutics: Challenges and solutions. Med. Chem. Res. 2024, 33, 1275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| THP | Sequence | Target | Target Disease | Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| iRGD | CRGDCKGDC | αvβ3 integrin | Breast Cancer, Carcinoma | [24,29] |

| tLyP-1 | CGNKRTRGC | p32 | Breast Cancer | [24] |

| GE11 | YHWYGYTPQNVI | EGFR | Lung Cancer | [30] |

| T7 | HAIYPRH | TfR | Glioblastoma | [31] |

| Peptide | Radionuclide | Target | Cancer Type | Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FAP-2286 | 177Lu | Fibroblast activation protein | Pancreatic, ovarian and colorectal cancer | [44] |

| PSMA-targeted peptide | 177Lu | Prostate-specific membrane antigen | Prostate cancer | [45] |

| Various peptides | 90Y | Tumor-specific receptors | Colorectal cancer and liver metastases | [46] |

| Octreotide | 90Y, 177Lu | Somatostatin receptor subtype 2 | Neuroendocrine neoplasms and GH-secreting tumors | [47,48,49,50] |

| Class | Examples (Peptide Drugs) | Mechanism of Action | Clinical Features | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GnRH Agonists | Leuprolide, Goserelin, Triptorelin, Buserelin | Initially stimulate pituitary GnRH receptors → transient surge in LH, FSH, testosterone (flare) → receptor desensitization with continuous use → suppression of gonadotropins and androgens | Widely used in prostate and premenopausal breast cancer | Long clinical track record; effective androgen suppression; various formulations (injections, implants) | Tumor flare effect (requires antiandrogen co-therapy); slower onset of castration |

| GnRH Antagonists | Degarelix, Cetrorelix, Relugolix (oral, non-peptide) | Competitively block GnRH receptors at pituitary → immediate suppression of LH/FSH → rapid fall in testosterone without flare | Increasing use in advanced/metastatic prostate cancer; relugolix shown safer in cardiovascular risk patients | Immediate effect; avoids tumor flare; oral option (relugolix); favorable safety profile | Higher cost (in some cases); shorter history of clinical use compared to agonists |

| Peptide Vaccine | Target Antigen | Mechanism of Action | Cancer Type | Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IMA901 | Multiple TUMAPs | Induces T cell response | Renal cell carcinoma | [138] |

| NeuVax (E75) | HER2 | Stimulates CD8+ T cells via GM-CSF | Breast cancer | [139] |

| GP2 | Her2 | Induces HER2-specific CD8+ T cells | Breast cancer | [140,141,142,143,144,145,146] |

| GV1001 | hTERT | Penetrates cells, inhibiting proliferation and inflammation | Prostate and pancreatic cancer and melanoma | [135,136,137,138] |

| Checkpoint Target | Peptide (Sequence) | Mechanism of Action | Key Findings/Outcomes | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PD-L1 | CLP002 (WHRSYYTWNLNT) | Binds PD-L1 with high affinity, blocks PD-L1/CD80 interaction | Restores T cell proliferation and survival; prevents apoptosis of tumor-infiltrating T cells | [159] |

| PD-L1 | AUNP-12 (LKEKKLGEFGKAKGLGKDGK) | Competitive antagonist derived from PD-1 extracellular domain | Blocks PD-1/PD-L1; restores T cell activation; also used in near-infrared imaging probes for PD-L1 monitoring in vivo | [162] |

| PD-L1/PD-1 | YT-16 (YRCMISYGGADYKCIT) | Cyclic peptide antagonist identified via virtual screening | Enhances T cell cytokine secretion and cytotoxicity | [160] |

| TIM-3 | P26 (GLIPLTTMHIGK) | Competes with Galectin-9 for TIM-3 binding | Restores T cell function; in vivo antitumor activity | [161] |

| CTLA-4 | p334 (ARHPSWYRPFEGCG) | Mimics CTLA-4 loop region binding to B7 ligands | Blocks CTLA-4/B7 interaction; potential CTLA-4 antagonist | [163] |

| Peptide/ Modality | Target | Payload/ Adjuvant | Indication | Trial Phase | Identifier (NCT) | Outcome/Status (Summary) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ANG1005 (GRN1005)—PDC (angiopep-2–paclitaxel) | LRP1 (LRP-1 mediated transcytosis) | 3 × paclitaxel (conjugate) | Brain metastases/glioma | I/II → III program | NCT03613181 | Demonstrated BBB penetration and signals of activity in early trials; progressed to larger trials exploring brain mets/leptomeningeal disease. Evidence supports BBB transport but mixed efficacy signals; safety manageable with hematologic DLTs reported. |

| GP2 (vaccine) FLAMINGO-01 | HER2 (E75 family peptide fragment) | GM-CSF adjuvant | HER2 + BC (adjuvant therapy) | Phase III | NCT05232916 | Designed to assess disease-free survival in adjuvant patient subset; prior phase I/II data supportive of immunogenicity; phase III active. |

| NeuVax/(E75) peptide vaccine | HER2 (E75) | GM-CSF adjuvant | Early-stage HER2+ BC | Phase II/III | NCT01479244 (ongoing) | Large phase trials produced mixed/limited efficacy signals; some arms terminated or re-focused (important lesson on HLA restriction and adjuvant dependence). |

| GV1001 telomerase peptide vaccine | hTERT | Various adjuvant regimens (clinical trials varied) | NSCLC, pancreatic cancer, melanoma (multiple trials) | Phase I/II | NCT03184467 (example recent trial) | Induces immune responses; mixed clinical efficacy in larger trials; some positive signals in immune responders but overall inconsistent survival benefit. |

| 177Lu -FAP-2286 peptide-guided radionuclide | Fibroblast activation protein (FAP) | 177Lu radioligand payload | Various advanced solid tumors with FAP expression | Early clinical (first-in-human/expansion cohorts) | NCT04939610 (and related early-phase studies) | Shows selective tumor uptake; preliminary antitumor activity reported in small cohorts; further trials underway to define efficacy/toxicity profile. |

| Selected PRRT examples (benchmark) somatostatin analogues | SSTR2 | 177Lu, 90Y, 111In labeled analogues | Neuroendocrine tumors (NETs) | Established clinical use (approved regimens) | many NCTs/registries (e.g., Lutetium-177DOTATATE programs) | Strongest clinical evidence among peptide modalities—durable disease control in selected NET patients; established safety profile and regulatory approvals. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Gouveia, M.J.; Campanhã, J.; Barbosa, F.; Vale, N. From Mechanism to Medicine: Peptide-Based Approaches for Cancer Diagnosis and Therapy. Biomolecules 2026, 16, 27. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom16010027

Gouveia MJ, Campanhã J, Barbosa F, Vale N. From Mechanism to Medicine: Peptide-Based Approaches for Cancer Diagnosis and Therapy. Biomolecules. 2026; 16(1):27. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom16010027

Chicago/Turabian StyleGouveia, Maria João, Joana Campanhã, Francisca Barbosa, and Nuno Vale. 2026. "From Mechanism to Medicine: Peptide-Based Approaches for Cancer Diagnosis and Therapy" Biomolecules 16, no. 1: 27. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom16010027

APA StyleGouveia, M. J., Campanhã, J., Barbosa, F., & Vale, N. (2026). From Mechanism to Medicine: Peptide-Based Approaches for Cancer Diagnosis and Therapy. Biomolecules, 16(1), 27. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom16010027