A Possible Role for the Vagus Nerve in Physical and Mental Health

Abstract

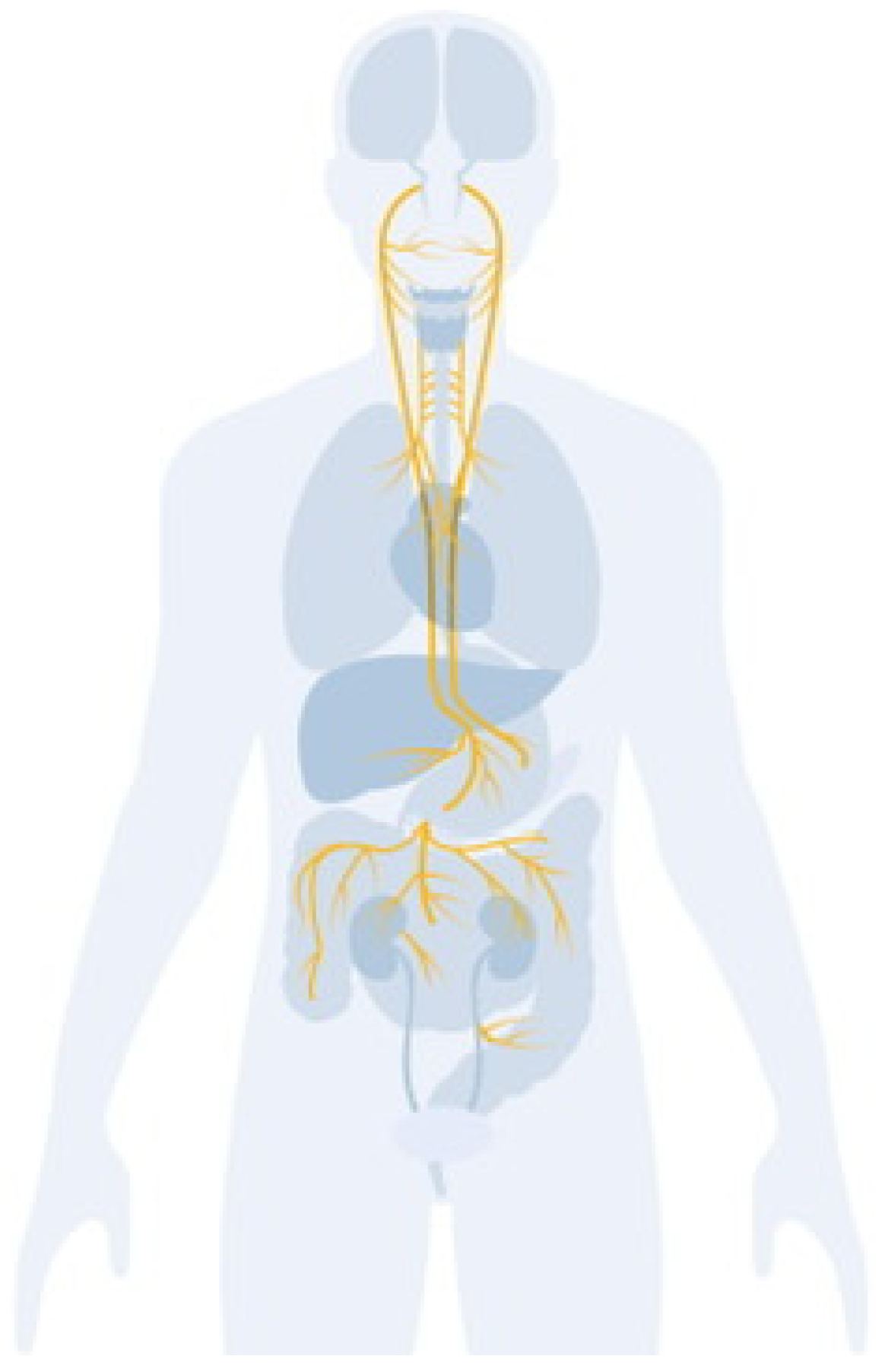

1. Introduction

2. Historical Background and Early Discoveries

3. Mechanistic Insights and Serendipitous Discoveries

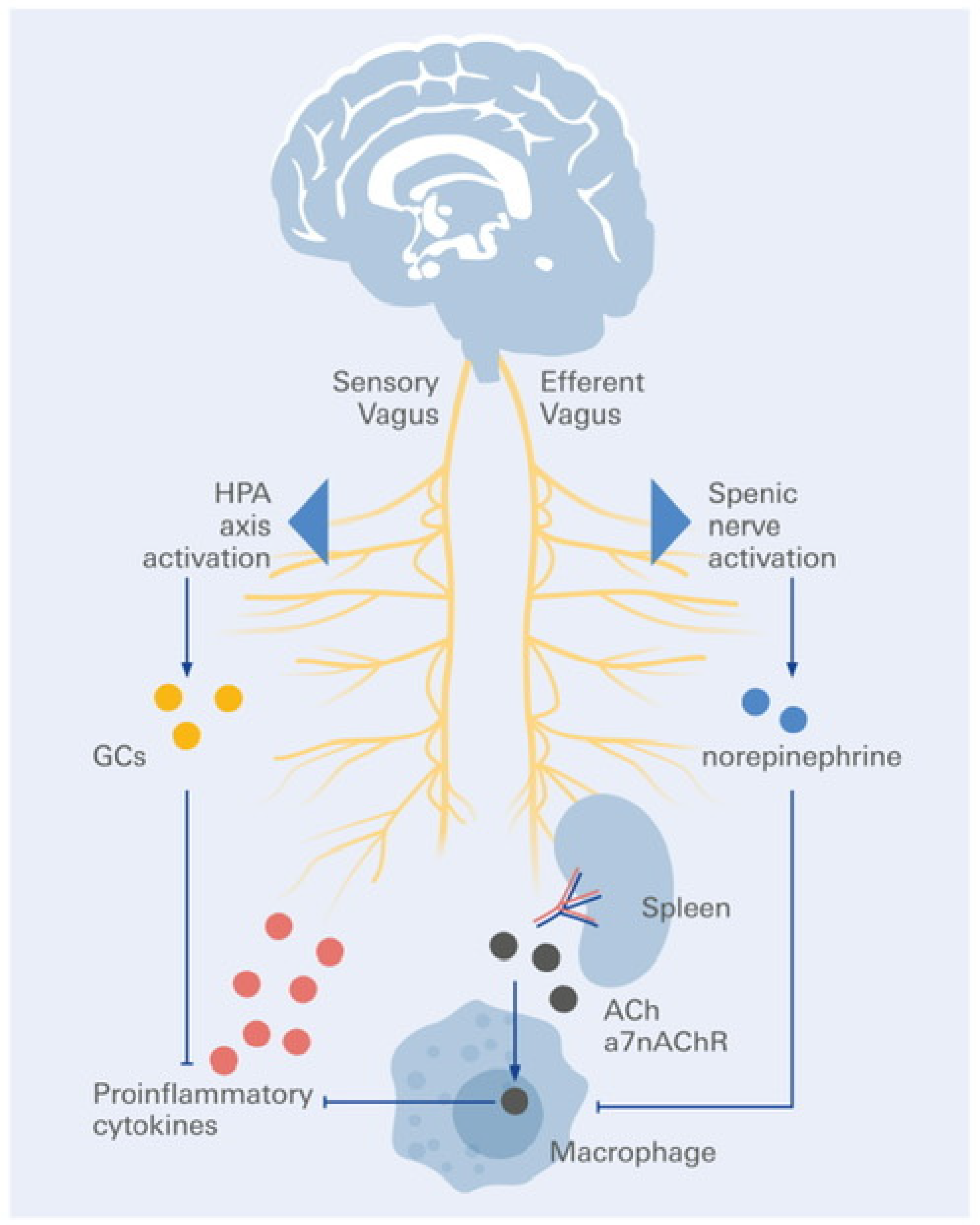

4. Clinical Evidence: VNS in Depression

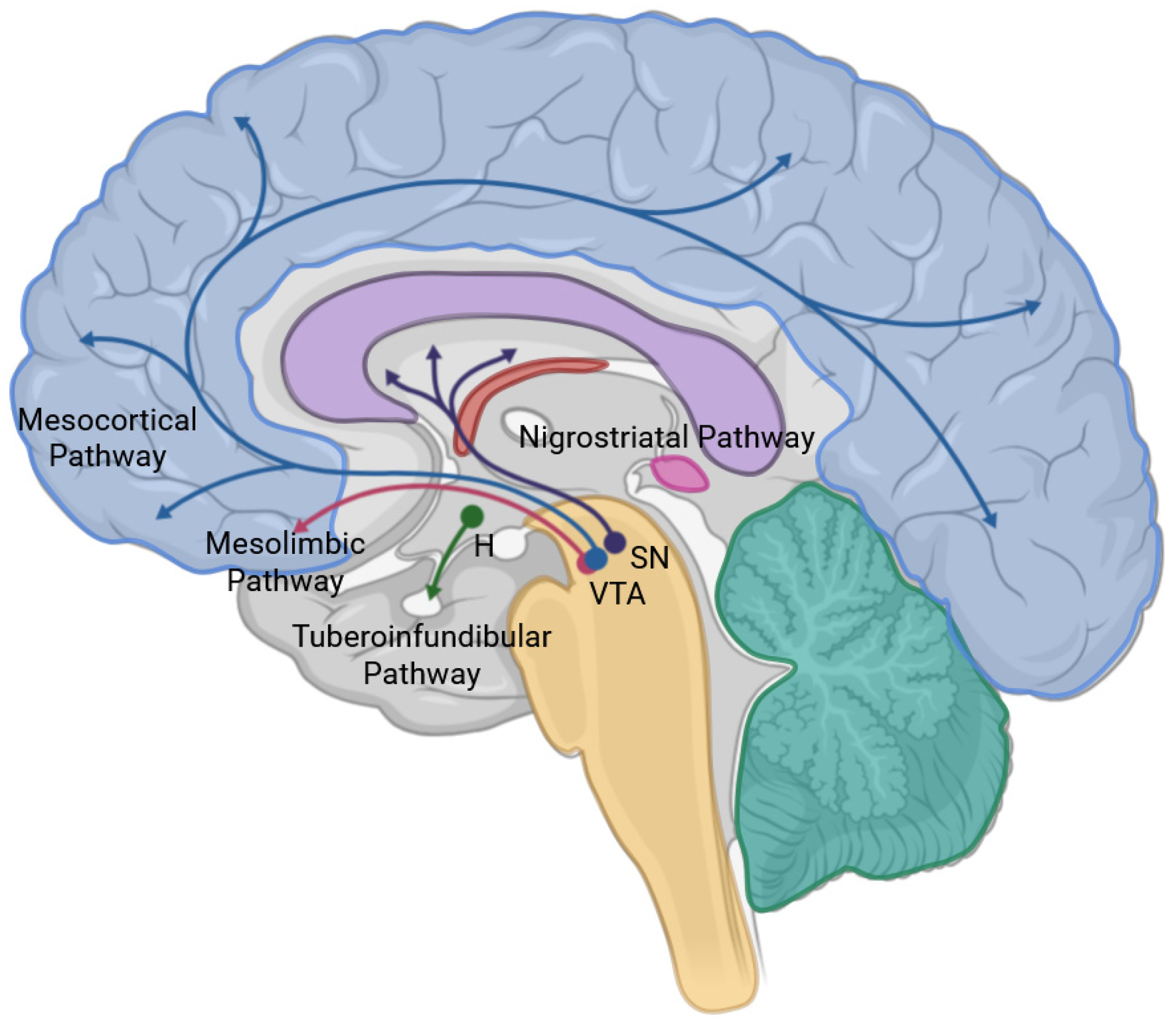

5. Inflammation, Neuroimmune Interfaces, and VNS

6. Neuroimaging and Neurochemical Correlations

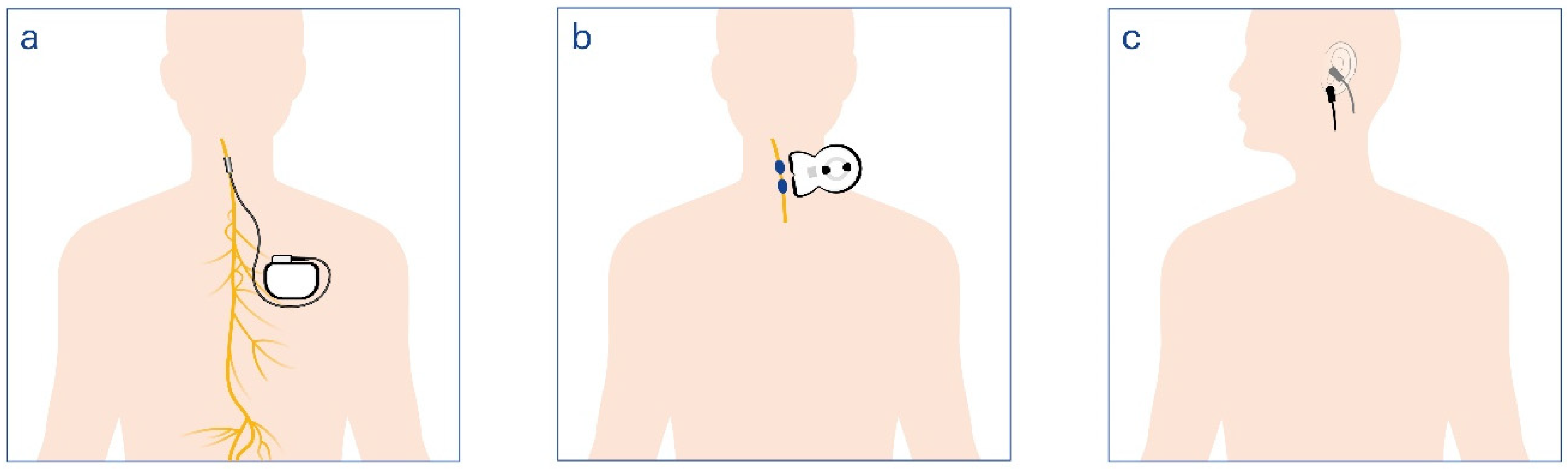

7. Vagal Pathways Linking Gut Microbiota to Motivation and Mood: Implications for taVNS

8. Technological Advances and Future Directions

9. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| VNS | Vagus Nerve Stimulation |

| tVNS | Transcutaneous Vagus Nerve Stimulation |

| FDA | Food and Drug Administration |

| SPARC | Stimulating Peripheral Activity to Relieve Conditions |

| CMS | Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services |

| BDNF | Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor |

| PTSD | Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder |

References

- Berthoud, H.-R.; Neuhuber, W.L. Functional and Chemical Anatomy of the Afferent Vagal System. Auton. Neurosci. 2000, 85, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prescott, S.L.; Liberles, S.D. Internal Senses of the Vagus Nerve. Neuron 2022, 110, 579–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Groves, D.A.; Brown, V.J. Vagal Nerve Stimulation: A Review of Its Applications and Potential Mechanisms That Mediate Its Clinical Effects. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2005, 29, 493–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dawson, J.; Abdul-Rahim, A.H.; Kimberley, T.J. Neurostimulation for Treatment of Post-Stroke Impairments. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2024, 20, 259–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yakunina, N.; Kim, S.S.; Nam, E.-C. Optimization of Transcutaneous Vagus Nerve Stimulation Using Functional MRI. Neuromodulation Technol. Neural Interface 2017, 20, 290–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tracey, K.J. The Inflammatory Reflex. Nature 2002, 420, 853–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-Menachem, E. Vagus-Nerve Stimulation for the Treatment of Epilepsy. Lancet Neurol. 2002, 1, 477–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frangos, E.; Ellrich, J.; Komisaruk, B.R. Non-Invasive Access to the Vagus Nerve Central Projections via Electrical Stimulation of the External Ear: fMRI Evidence in Humans. Brain Stimulat. 2015, 8, 624–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imam, F.T.; Gillespie, T.H.; Ziogas, I.; Surles-Zeigler, M.C.; Tappan, S.; Ozyurt, B.I.; Boline, J.; De Bono, B.; Grethe, J.S.; Martone, M.E. Developing a Multiscale Neural Connectivity Knowledgebase of the Autonomic Nervous System. Front. Neuroinform. 2025, 19, 1541184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surles-Zeigler, M.C.; Sincomb, T.; Gillespie, T.H.; De Bono, B.; Bresnahan, J.; Mawe, G.M.; Grethe, J.S.; Tappan, S.; Heal, M.; Martone, M.E. Extending and Using Anatomical Vocabularies in the Stimulating Peripheral Activity to Relieve Conditions Project. Front. Neuroinform. 2022, 16, 819198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonaz, B.; Sinniger, V.; Pellissier, S. Therapeutic Potential of Vagus Nerve Stimulation for Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. Front. Neurosci. 2021, 15, 650971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, M.W.Z.; Ahmad, M.; Qudrat, S.; Afridi, F.; Khan, N.A.; Afridi, Z.; Fahad; Azeem, T.; Ikram, J. Vagal Nerve Stimulation for the Management of Long COVID Symptoms. Infect. Med. 2024, 3, 100149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koopman, F.A.; Chavan, S.S.; Miljko, S.; Grazio, S.; Sokolovic, S.; Schuurman, P.R.; Mehta, A.D.; Levine, Y.A.; Faltys, M.; Zitnik, R.; et al. Vagus Nerve Stimulation Inhibits Cytokine Production and Attenuates Disease Severity in Rheumatoid Arthritis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, 8284–8289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Straube, A.; Ellrich, J.; Eren, O.; Blum, B.; Ruscheweyh, R. Treatment of Chronic Migraine with Transcutaneous Stimulation of the Auricular Branch of the Vagal Nerve (Auricular t-VNS): A Randomized, Monocentric Clinical Trial. J. Headache Pain 2015, 16, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breit, S.; Kupferberg, A.; Rogler, G.; Hasler, G. Vagus Nerve as Modulator of the Brain–Gut Axis in Psychiatric and Inflammatory Disorders. Front. Psychiatry 2018, 9, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandel, E.R.; Koester, J.D.; Mack, S.H.; Siegelbaum, S.A. (Eds.) Principles of Neural Science, 6th ed.; McGraw-Hill’s Access Neurology; McGraw-Hill Education LLC: New York, NY, USA, 2021; ISBN 978-1-259-64223-4. [Google Scholar]

- Lanska, D.J. J.L. Corning and Vagal Nerve Stimulation for Seizures in the 1880s. Neurology 2002, 58, 452–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zabara, J. Inhibition of Experimental Seizures in Canines by Repetitive Vagal Stimulation. Epilepsia 1992, 33, 1005–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penry, J.K.; Dean, J.C. Prevention of Intractable Partial Seizures by Intermittent Vagal Stimulation in Humans: Preliminary Results. Epilepsia 1990, 31, S40–S43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandalaneni, K.; Rayi, A.; Jillella, D.V. Stroke Reperfusion Injury. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Huerta, T.S.; Chen, A.C.; Chaudhry, S.; Tynan, A.; Morgan, T.; Park, K.; Adamovich-Zeitlin, R.; Haider, B.; Li, J.H.; Nagpal, M.; et al. Neural Representation of Cytokines by Vagal Sensory Neurons. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 3840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bratton, B.O.; Martelli, D.; McKinley, M.J.; Trevaks, D.; Anderson, C.R.; McAllen, R.M. Neural regulation of inflammation: No neural connection from the vagus to splenic sympathetic neurons. Exp. Physiol. 2012, 97, 1180–1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Labar, D.; Murphy, J.; Tecoma, E.; The E VNS Study Group Vagus. Nerve Stimulation for Medication-Resistant Generalized Epilepsy. Neurology 1999, 52, 1510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okonogi, T.; Kuga, N.; Yamakawa, M.; Kayama, T.; Ikegaya, Y.; Sasaki, T. Stress-Induced Vagal Activity Influences Anxiety-Relevant Prefrontal and Amygdala Neuronal Oscillations in Male Mice. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holt, M.K.; Pomeranz, L.E.; Beier, K.T.; Reimann, F.; Gribble, F.M.; Rinaman, L. Synaptic Inputs to the Mouse Dorsal Vagal Complex and Its Resident Preproglucagon Neurons. J. Neurosci. 2019, 39, 9767–9781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riters, L.V. Pleasure Seeking and Birdsong. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2011, 35, 1837–1845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedner, J. Neuropharmacological Aspects of Central Respiratory Regulation. An Experimental Study in the Rat. Acta Physiol. Scand. Suppl. 1983, 524, 1–109. [Google Scholar]

- Homma, S.; Yamazaki, Y.; Karakida, T. Blood Pressure and Heart Rate Relationships during Cervical Sympathetic and Vagus Nerve Stimulation in Streptozotocin Diabetic Rats. Brain Res. 1993, 629, 342–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diebolt, M.; Bucher, B.; Andriantsitohaina, R. Wine Polyphenols Decrease Blood Pressure, Improve NO Vasodilatation, and Induce Gene Expression. Hypertension 2001, 38, 159–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, T.A.; Perry, M.L.; Getsoian, A.G.; Monteleon, C.L.; Cogen, A.L.; Standiford, T.J. Increased Mortality and Dysregulated Cytokine Production in Tumor Necrosis Factor Receptor 1-Deficient Mice Following Systemic Klebsiella Pneumoniae Infection. Infect. Immun. 2003, 71, 4891–4900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández Cruz, A.; Garcia-Jimenez, S.; Zucatelli Mendonça, R.; Petricevich, V.L. Pro- and Anti-Inflammatory Cytokines Release in Mice Injected with Crotalus Durissus Terrificus Venom. Mediators Inflamm. 2008, 2008, 874962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burek, M.; Salvador, E.; Förster, C.Y. Generation of an Immortalized Murine Brain Microvascular Endothelial Cell Line as an In Vitro Blood Brain Barrier Model. J. Vis. Exp. 2012, 66, e4022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borovikova, L.V.; Ivanova, S.; Zhang, M.; Yang, H.; Botchkina, G.I.; Watkins, L.R.; Wang, H.; Abumrad, N.; Eaton, J.W.; Tracey, K.J. Vagus Nerve Stimulation Attenuates the Systemic Inflammatory Response to Endotoxin. Nature 2000, 405, 458–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Furman, D.; Campisi, J.; Verdin, E.; Carrera-Bastos, P.; Targ, S.; Franceschi, C.; Ferrucci, L.; Gilroy, D.W.; Fasano, A.; Miller, G.W.; et al. Chronic Inflammation in the Etiology of Disease across the Life Span. Nat. Med. 2019, 25, 1822–1832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capuron, L.; Miller, A.H. Immune System to Brain Signaling: Neuropsychopharmacological Implications. Pharmacol. Ther. 2011, 130, 226–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlov, V.A.; Tracey, K.J. The Vagus Nerve and the Inflammatory Reflex—Linking Immunity and Metabolism. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2012, 8, 743–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raison, C.L.; Capuron, L.; Miller, A.H. Cytokines Sing the Blues: Inflammation and the Pathogenesis of Depression. Trends Immunol. 2006, 27, 24–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dantzer, R.; O’Connor, J.C.; Freund, G.G.; Johnson, R.W.; Kelley, K.W. From Inflammation to Sickness and Depression: When the Immune System Subjugates the Brain. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2008, 9, 46–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capuron, L.; Miller, A.H. Cytokines and Psychopathology: Lessons from Interferon-α. Biol. Psychiatry 2004, 56, 819–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harsanyi, S.; Kupcova, I.; Danisovic, L.; Klein, M. Selected Biomarkers of Depression: What Are the Effects of Cytokines and Inflammation? Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 24, 578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michopoulos, V.; Powers, A.; Gillespie, C.F.; Ressler, K.J.; Jovanovic, T. Inflammation in Fear- and Anxiety-Based Disorders: PTSD, GAD, and Beyond. Neuropsychopharmacology 2017, 42, 254–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sackeim, H. Vagus Nerve Stimulation (VNSTM) for Treatment-Resistant Depression Efficacy, Side Effects, and Predictors of Outcome. Neuropsychopharmacology 2001, 25, 713–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conway, C.R.; Olin, B.; Aaronson, S.T.; Sackeim, H.A.; Bunker, M.; Kriedt, C.; Greco, T.; Broglio, K.; Vestrucci, M.; Rush, A.J. A Prospective, Multi-Center Randomized, Controlled, Blinded Trial of Vagus Nerve Stimulation for Difficult to Treat Depression: A Novel Design for a Novel Treatment. Contemp. Clin. Trials 2020, 95, 106066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marwaha, S.; Palmer, E.; Suppes, T.; Cons, E.; Young, A.H.; Upthegrove, R. Novel and Emerging Treatments for Major Depression. Lancet 2023, 401, 141–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-Menachem, E.; Revesz, D.; Simon, B.J.; Silberstein, S. Surgically Implanted and Non-invasive Vagus Nerve Stimulation: A Review of Efficacy, Safety and Tolerability. Eur. J. Neurol. 2015, 22, 1260–1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perera, T.; George, M.S.; Grammer, G.; Janicak, P.G.; Pascual-Leone, A.; Wirecki, T.S. The Clinical TMS Society Consensus Review and Treatment Recommendations for TMS Therapy for Major Depressive Disorder. Brain Stimulat. 2016, 9, 336–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finniss, D.G.; Kaptchuk, T.J.; Miller, F.; Benedetti, F. Biological, Clinical, and Ethical Advances of Placebo Effects. Lancet 2010, 375, 686–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lisanby, S.H. Electroconvulsive Therapy for Depression. N. Engl. J. Med. 2007, 357, 1939–1945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UK Ect Review Group. Efficacy and Safety of Electroconvulsive Therapy in Depressive Disorders: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Lancet 2003, 361, 799–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Förster, C.Y. Transcutaneous Non-Invasive Vagus Nerve Stimulation: Changing the Paradigm for Stroke and Atrial Fibrillation Therapies? Biomolecules 2024, 14, 1511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blecharz, K.G.; Haghikia, A.; Stasiolek, M.; Kruse, N.; Drenckhahn, D.; Gold, R.; Roewer, N.; Chan, A.; Förster, C.Y. Glucocorticoid Effects on Endothelial Barrier Function in the Murine Brain Endothelial Cell Line cEND Incubated with Sera from Patients with Multiple Sclerosis. Mult. Scler. J. 2010, 16, 293–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ji, H.; Rabbi, M.F.; Labis, B.; Pavlov, V.A.; Tracey, K.J.; Ghia, J.E. Central Cholinergic Activation of a Vagus Nerve-to-Spleen Circuit Alleviates Experimental Colitis. Mucosal Immunol. 2014, 7, 335–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiweck, C.; Sausmekat, S.; Zhao, T.; Jacobsen, L.; Reif, A.; Edwin Thanarajah, S. No Consistent Evidence for the Anti-Inflammatory Effect of Vagus Nerve Stimulation in Humans: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Brain. Behav. Immun. 2024, 116, 237–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiweck, C.; Dalile, B.; Balliet, A.; Aichholzer, M.; Reinken, H.; Erhardt, F.; Freiling, J.; Bouzouina, A.; Uckermark, C.; Reif, A.; et al. Circulating Short Chain Fatty Acids Are Associated with Depression Severity and Predict Remission from Major Depressive Disorder. Brain Behav. Immun. Health 2025, 48, 101070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, J.; Egorova, N.; Rong, P.; Liu, J.; Hong, Y.; Fan, Y.; Wang, X.; Wang, H.; Yu, Y.; Ma, Y.; et al. Early Cortical Biomarkers of Longitudinal Transcutaneous Vagus Nerve Stimulation Treatment Success in Depression. NeuroImage Clin. 2017, 14, 105–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Fang, J.; Wang, Z.; Rong, P.; Hong, Y.; Fan, Y.; Wang, X.; Park, J.; Jin, Y.; Liu, C.; et al. Transcutaneous Vagus Nerve Stimulation Modulates Amygdala Functional Connectivity in Patients with Depression. J. Affect. Disord. 2016, 205, 319–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.-H.; Yang, M.-H.; Zhang, G.-Z.; Wang, X.-X.; Li, B.; Li, M.; Woelfer, M.; Walter, M.; Wang, L. Neural Networks and the Anti-Inflammatory Effect of Transcutaneous Auricular Vagus Nerve Stimulation in Depression. J. Neuroinflamm. 2020, 17, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manta, S.; Dong, J.; Debonnel, G.; Blier, P. Enhancement of the Function of Rat Serotonin and Norepinephrine Neurons by Sustained Vagus Nerve Stimulation. J. Psychiatry Neurosci. 2009, 34, 272–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conway, C.R.; Sheline, Y.I.; Chibnall, J.T.; George, M.S.; Fletcher, J.W.; Mintun, M.A. Cerebral Blood Flow Changes during Vagus Nerve Stimulation for Depression. Psychiatry Res. Neuroimaging 2006, 146, 179–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brougher, J.; Aziz, U.; Adari, N.; Chaturvedi, M.; Jules, A.; Shah, I.; Syed, S.; Thorn, C.A. Self-Administration of Right Vagus Nerve Stimulation Activates Midbrain Dopaminergic Nuclei. Front. Neurosci. 2021, 15, 782786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, T.-Y.; Kim, J.; Koo, J.W. Transcutaneous Auricular Vagus Nerve Stimulation in Anesthetized Mice Induces Antidepressant Effects by Activating Dopaminergic Neurons in the Ventral Tegmental Area. Mol. Brain 2024, 17, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foster, J.A.; McVey Neufeld, K.-A. Gut–Brain Axis: How the Microbiome Influences Anxiety and Depression. Trends Neurosci. 2013, 36, 305–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Rong, P.; Wang, Y.; Jin, G.; Hou, X.; Li, S.; Xiao, X.; Zhou, W.; Wu, Y.; Liu, Y.; et al. Comparative Effectiveness of Transcutaneous Auricular Vagus Nerve Stimulation vs Citalopram for Major Depressive Disorder: A Randomized Trial. Neuromodulation Technol. Neural Interface 2022, 25, 450–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koenig, J.; Parzer, P.; Haigis, N.; Liebemann, J.; Jung, T.; Resch, F.; Kaess, M. Effects of Acute Transcutaneous Vagus Nerve Stimulation on Emotion Recognition in Adolescent Depression. Psychol. Med. 2021, 51, 511–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osanlouy, M.; Bandrowski, A.; De Bono, B.; Brooks, D.; Cassarà, A.M.; Christie, R.; Ebrahimi, N.; Gillespie, T.; Grethe, J.S.; Guercio, L.A.; et al. The SPARC DRC: Building a Resource for the Autonomic Nervous System Community. Front. Physiol. 2021, 12, 693735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thal, S.C.; Shityakov, S.; Salvador, E.; Förster, C.Y. Heart Rate Variability, Microvascular Dysfunction, and Inflammation: Exploring the Potential of taVNS in Managing Heart Failure in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Biomolecules 2025, 15, 499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tovbis, D.; Lee, E.; Koh, R.G.L.; Jeong, R.; Agur, A.; Yoo, P.B. Enhancing the Selective Electrical Activation of Human Vagal Nerve Fibers: A Comparative Computational Modeling Study with Validation in a Rat Sciatic Model. J. Neural Eng. 2023, 20, 066012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mylavarapu, R.V.; Kanumuri, V.V.; De Rivero Vaccari, J.P.; Misra, A.; McMillan, D.W.; Ganzer, P.D. Importance of Timing Optimization for Closed-Loop Applications of Vagus Nerve Stimulation. Bioelectron. Med. 2023, 9, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerman, I.; Bu, Y.; Singh, R.; Silverman, H.A.; Bhardwaj, A.; Mann, A.J.; Widge, A.; Palin, J.; Puleo, C.; Lim, H. Next Generation Bioelectronic Medicine: Making the Case for Non-Invasive Closed-Loop Autonomic Neuromodulation. Bioelectron. Med. 2025, 11, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, H.; Li, M.; Jeong, E.; Castro-Martinez, F.; Zuker, C.S. A Body–Brain Circuit That Regulates Body Inflammatory Responses. Nature 2024, 630, 695–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Förster, C.Y.; Shityakov, S. A Possible Role for the Vagus Nerve in Physical and Mental Health. Biomolecules 2026, 16, 121. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom16010121

Förster CY, Shityakov S. A Possible Role for the Vagus Nerve in Physical and Mental Health. Biomolecules. 2026; 16(1):121. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom16010121

Chicago/Turabian StyleFörster, Carola Y., and Sergey Shityakov. 2026. "A Possible Role for the Vagus Nerve in Physical and Mental Health" Biomolecules 16, no. 1: 121. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom16010121

APA StyleFörster, C. Y., & Shityakov, S. (2026). A Possible Role for the Vagus Nerve in Physical and Mental Health. Biomolecules, 16(1), 121. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom16010121