Enduring Effects of Humanin on Mitochondrial Systems in TBI Pathology

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals

2.2. Fluid Percussion Injury

2.3. Barnes Maze Test

2.4. RT-PCR

2.5. Western Blot Analysis

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Effect of HN on Cognitive Function Post-TBI

3.2. Effects of HN on Metabolic Markers Post-TBI

3.3. Effects of HN on Mitochondria Post-TBI

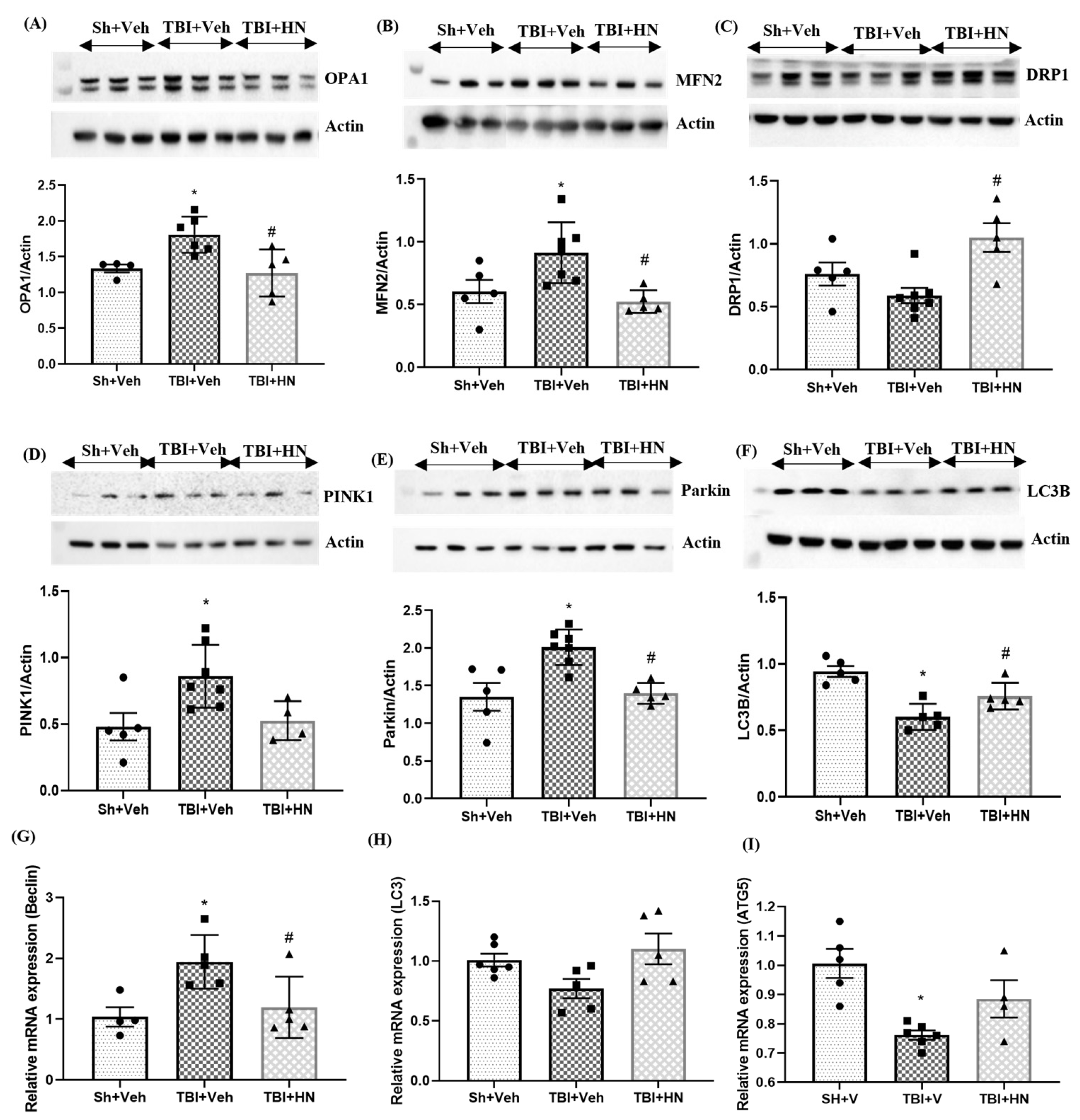

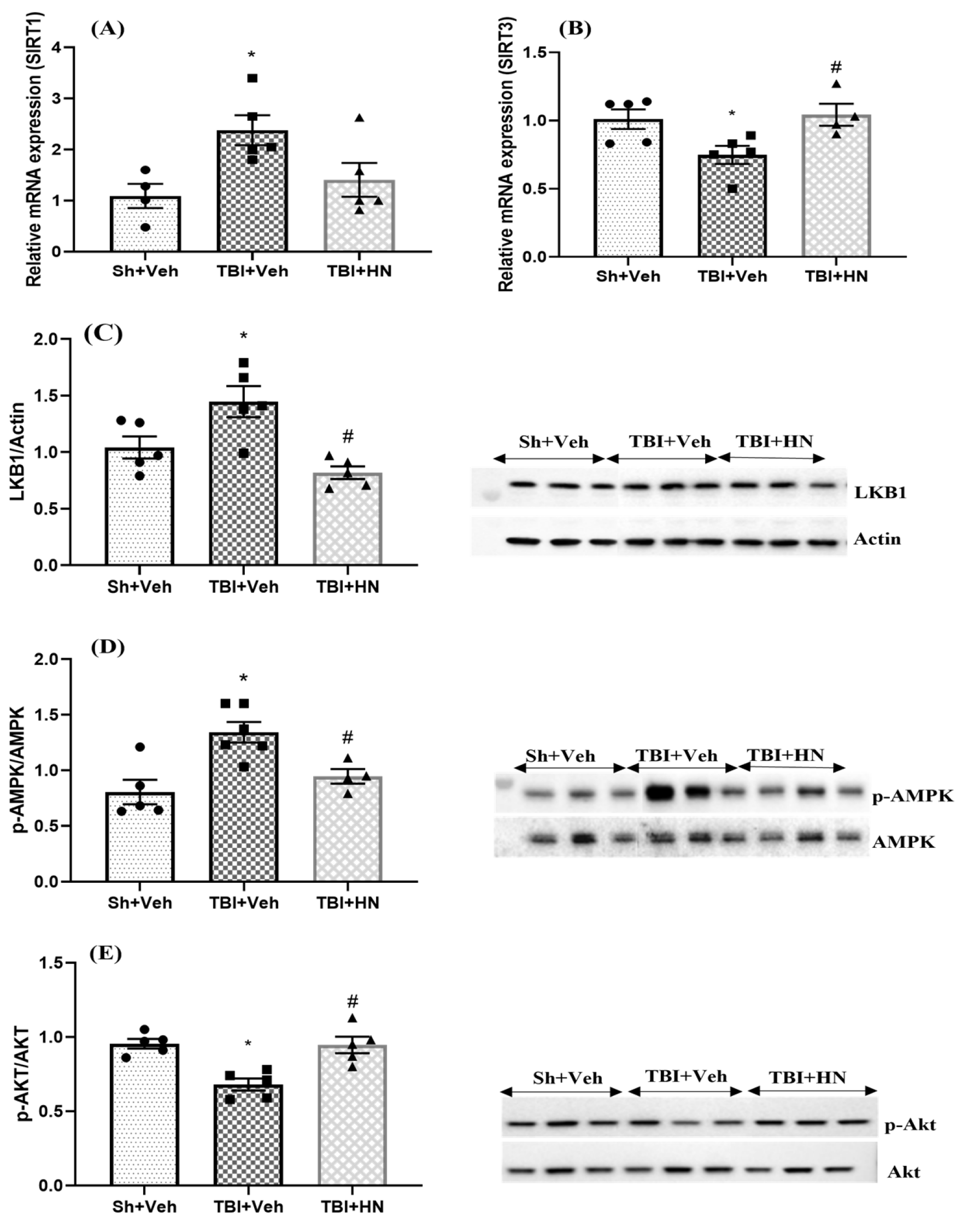

3.4. Effects of HN on Markers Associated with Mitochondrial Fusion, Fission, and Mitophagy Post-TBI

3.5. Effects of HN on Microglia and Astrocytes Post-TBI

3.6. Effects of HN on Mitochondrial Biogenesis, Antioxidant, and Apoptotic Marker Post-TBI

4. Discussion

4.1. Effects of HN on Metabolic Homeostasis After TBI

4.2. Effects of HN on Mitochondrial Dynamics; Bioenergetic, Fusion, Fission, and Mitophagy

4.3. Effects of TBI and HN on Cognitive Function

4.4. Effects of HN on Microglial and Astrocytes Post-TBI

4.5. Study Limitations and Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Thapak, P.; Gomez-Pinilla, F. The Bioenergetics of Traumatic Brain Injury and Its Long-Term Impact for Brain Plasticity and Function. Pharmacol. Res. 2024, 208, 107389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- James, S.L.; Theadom, A.; Ellenbogen, R.G.; Bannick, M.S.; Montjoy-Venning, W.C.; Lucchesi, L.R.; Abbasi, N.; Abdulkader, R.; Abraha, H.N.; Adsuar, J.C.; et al. Global, Regional, and National Burden of Traumatic Brain Injury and Spinal Cord Injury, 1990–2016: A Systematic Analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet Neurol. 2019, 18, 56–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlovic, D.; Pekic, S.; Stojanovic, M.; Popovic, V. Traumatic Brain Injury: Neuropathological, Neurocognitive and Neurobehavioral Sequelae. Pituitary 2019, 22, 270–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomez-Pinilla, F.; Thapak, P. Exercise Epigenetics Is Fueled by Cell Bioenergetics: Supporting Role on Brain Plasticity and Cognition. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2024, 220, 43–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hashimoto, Y.; Kurita, M.; Aiso, S.; Nishimoto, I.; Matsuoka, M. Humanin Inhibits Neuronal Cell Death by Interacting with a Cytokine Receptor Complex or Complexes Involving CNTF Receptor α/WSX-1/Gp130. Mol. Biol. Cell 2009, 20, 2864–2873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamiya, T.; Ukai, M. [Gly14]-Humanin Improved the Learning and Memory Impairment Induced by Scopolamine in Vivo. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2001, 134, 1597–1599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Chua, C.C.; Gao, J.; Chua, K.-W.; Wang, H.; Hamdy, R.C.; Chua, B.H.L. Neuroprotective Effect of Humanin on Cerebral Ischemia/Reperfusion Injury Is Mediated by a PI3K/Akt Pathway. Brain Res. 2008, 1227, 12–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, M.; Bao, H.; Liu, W.; Wang, Y.; Wang, L.; Dai, D.; Chang, P.; Dong, W.; et al. [Gly14]-Humanin Reduces Histopathology and Improves Functional Outcome after Traumatic Brain Injury in Mice. Neuroscience 2013, 231, 70–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.-T.; Zhao, L.; Li, J.-H. Neuroprotective Peptide Humanin Inhibits Inflammatory Response in Astrocytes Induced by Lipopolysaccharide. Neurochem. Res. 2013, 38, 581–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Xiao, J.; Wan, J.; Cohen, P.; Yen, K. Mitochondrially Derived Peptides as Novel Regulators of Metabolism. J. Physiol. 2017, 595, 6613–6621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, S.; Hu, X.; Bennett, S.; Xu, J.; Mai, Y. The Molecular Structure and Role of Humanin in Neural and Skeletal Diseases, and in Tissue Regeneration. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2022, 10, 823354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yen, K.; Lee, C.; Mehta, H.; Cohen, P. The Emerging Role of the Mitochondrial-Derived Peptide Humanin in Stress Resistance. J. Mol. Endocrinol. 2013, 50, R11–R19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, W.; Zhang, W.; Li, Z.; Hao, J.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, L.; Mao, N.; Miao, J.; Zhang, L. S14G-Humanin Improves Cognitive Deficits and Reduces Amyloid Pathology in the Middle-Aged APPswe/PS1dE9 Mice. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 2012, 100, 361–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thapak, P.; Ying, Z.; Palafox-Sanchez, V.; Zhang, G.; Yang, X.; Gomez-Pinilla, F. Humanin Ameliorates TBI-Related Cognitive Impairment by Attenuating Mitochondrial Dysfunction and Inflammation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA)—Mol. Basis Dis. 2024, 1870, 166937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thapak, P.; Smith, G.; Ying, Z.; Paydar, A.; Harris, N.; Gomez-Pinilla, F. The BDNF Mimetic R-13 Attenuates TBI Pathogenesis Using TrkB-Related Pathways and Bioenergetics. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA)—Mol. Basis Dis. 2023, 1869, 166781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, T.D.; Hylin, M.J.; Zhao, J.; Moore, A.N.; Waxham, M.N.; Dash, P.K. Altered Mitochondrial Dynamics and TBI Pathophysiology. Front. Syst. Neurosci. 2016, 10, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.-M.; Lee, D.-H.; Kim, D.-H. Redefining the Role of AMPK in Autophagy and the Energy Stress Response. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 2994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benito-Cuesta, I.; Ordóñez-Gutiérrez, L.; Wandosell, F. AMPK Activation Does Not Enhance Autophagy in Neurons in Contrast to MTORC1 Inhibition: Different Impact on β-Amyloid Clearance. Autophagy 2021, 17, 656–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, J.; Bissa, B.; Brecht, L.; Allers, L.; Choi, S.W.; Gu, Y.; Zbinden, M.; Burge, M.R.; Timmins, G.; Hallows, K.; et al. AMPK, a Regulator of Metabolism and Autophagy, Is Activated by Lysosomal Damage via a Novel Galectin-Directed Ubiquitin Signal Transduction System. Mol. Cell 2020, 77, 951–969.e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Wang, H. Autophagy in Traumatic Brain Injury: A New Target for Therapeutic Intervention. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2018, 11, 190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Kroemer, G.; Kepp, O. Mitophagy: An Emerging Role in Aging and Age-Associated Diseases. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2020, 8, 200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arneson, D.; Zhang, G.; Ying, Z.; Zhuang, Y.; Byun, H.R.; Ahn, I.S.; Gomez-Pinilla, F.; Yang, X. Single Cell Molecular Alterations Reveal Target Cells and Pathways of Concussive Brain Injury. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 3894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, I.N.; Sullivan, P.G.; Deng, Y.; Mbye, L.H.; Hall, E.D. Time Course of Post-Traumatic Mitochondrial Oxidative Damage and Dysfunction in a Mouse Model of Focal Traumatic Brain Injury: Implications for Neuroprotective Therapy. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2006, 26, 1407–1418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krishna, G.; Agrawal, R.; Zhuang, Y.; Ying, Z.; Paydar, A.; Harris, N.G.; Royes, L.F.F.; Gomez-Pinilla, F. 7,8-Dihydroxyflavone Facilitates the Action Exercise to Restore Plasticity and Functionality: Implications for Early Brain Trauma Recovery. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA)—Mol. Basis Dis. 2017, 1863, 1204–1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaidya, B.; Kaur, H.; Thapak, P.; Sharma, S.S.; Singh, J.N. Pharmacological Modulation of TRPM2 Channels via PARP Pathway Leads to Neuroprotection in MPTP-Induced Parkinson’s Disease in Sprague Dawley Rats. Mol. Neurobiol. 2022, 59, 1528–1542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovács-Öller, T.; Zempléni, R.; Balogh, B.; Szarka, G.; Fazekas, B.; Tengölics, Á.J.; Amrein, K.; Czeiter, E.; Hernádi, I.; Büki, A.; et al. Traumatic Brain Injury Induces Microglial and Caspase3 Activation in the Retina. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 4451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burguillos, M.A.; Deierborg, T.; Kavanagh, E.; Persson, A.; Hajji, N.; Garcia-Quintanilla, A.; Cano, J.; Brundin, P.; Englund, E.; Venero, J.L.; et al. Caspase Signalling Controls Microglia Activation and Neurotoxicity. Nature 2011, 472, 319–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, J.E.; Sun, G.; Bautista Garrido, J.; Obertas, L.; Mobley, A.S.; Ting, S.-M.; Zhao, X.; Aronowski, J. The Mitochondria-Derived Peptide Humanin Improves Recovery from Intracerebral Hemorrhage: Implication of Mitochondria Transfer and Microglia Phenotype Change. J. Neurosci. 2020, 40, 2154–2165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suomalainen, A.; Nunnari, J. Mitochondria at the Crossroads of Health and Disease. Cell 2024, 187, 2601–2627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pineda, J.A.; Wang, K.K.W.; Hayes, R.L. Biomarkers of Proteolytic Damage Following Traumatic Brain Injury. Brain Pathol. 2004, 14, 202–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kampfl, A.; Posmantur, R.M.; Zhao, X.; Schmutzhard, E.; Clifton, G.L.; Hayes, R.L. Mechanisms of Calpain Proteolysis Following Traumatic Brain Injury: Implications for Pathology and Therapy: A Review and Update. J. Neurotrauma 1997, 14, 121–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musyaju, S.; Modi, H.R.; Shear, D.A.; Scultetus, A.H.; Pandya, J.D. Time Course of Mitochondrial Antioxidant Markers in a Preclinical Model of Severe Penetrating Traumatic Brain Injury. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glushakova, O.Y.; Glushakov, A.O.; Borlongan, C.V.; Valadka, A.B.; Hayes, R.L.; Glushakov, A.V. Role of Caspase-3-Mediated Apoptosis in Chronic Caspase-3-Cleaved Tau Accumulation and Blood–Brain Barrier Damage in the Corpus Callosum after Traumatic Brain Injury in Rats. J. Neurotrauma 2018, 35, 157–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knoblach, S.M.; Nikolaeva, M.; Huang, X.; Fan, L.; Krajewski, S.; Reed, J.C.; Faden, A.I. Multiple Caspases Are Activated after Traumatic Brain Injury: Evidence for Involvement in Functional Outcome. J. Neurotrauma 2002, 19, 1155–1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, V.E.; Stewart, J.E.; Begbie, F.D.; Trojanowski, J.Q.; Smith, D.H.; Stewart, W. Inflammation and White Matter Degeneration Persist for Years after a Single Traumatic Brain Injury. Brain 2013, 136, 28–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balasubramanian, N.; Jadhav, G.; Sakharkar, A.J. Repeated Mild Traumatic Brain Injuries Perturb the Mitochondrial Biogenesis via DNA Methylation in the Hippocampus of Rat. Mitochondrion 2021, 61, 11–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, P.; Gupta, R.; Sen, T.; Sen, N. Activation of Cyclin D1 Affects Mitochondrial Mass Following Traumatic Brain Injury. Neurobiol. Dis. 2018, 118, 108–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cantó, C.; Auwerx, J. PGC-1α, SIRT1 and AMPK, an Energy Sensing Network That Controls Energy Expenditure. Curr. Opin. Lipidol. 2009, 20, 98–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Y.; Chen, J.; Chen, P.; Hao, Q.; Cheong, L.-K.; Tang, M.; Hong, L.-L.; Hu, X.-Y.; Yap, C.T.; Bay, B.-H.; et al. Oxidative Stress-Mediated AMPK Inactivation Determines the High Susceptibility of LKB1-Mutant NSCLC Cells to Glucose Starvation. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2021, 166, 128–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauhan, A.S.; Zhuang, L.; Gan, B. Spatial Control of AMPK Signaling at Subcellular Compartments. Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2020, 55, 17–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.-S.; Jiang, B.; Li, M.; Zhu, M.; Peng, Y.; Zhang, Y.-L.; Wu, Y.-Q.; Li, T.Y.; Liang, Y.; Lu, Z.; et al. The Lysosomal V-ATPase-Ragulator Complex Is a Common Activator for AMPK and MTORC1, Acting as a Switch between Catabolism and Anabolism. Cell Metab. 2014, 20, 526–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, A.; Walker, C.L. The Role of LKB1 and AMPK in Cellular Responses to Stress and Damage. FEBS Lett. 2011, 585, 952–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muraleedharan, R.; Dasgupta, B. AMPK in the Brain: Its Roles in Glucose and Neural Metabolism. FEBS J. 2022, 289, 2247–2262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, V.; Giacomello, M.; Hudec, R.; Lopreiato, R.; Ermak, G.; Lim, D.; Malorni, W.; Davies, K.J.A.; Carafoli, E.; Scorrano, L. Mitochondrial Fission and Cristae Disruption Increase the Response of Cell Models of Huntington’s Disease to Apoptotic Stimuli. EMBO Mol. Med. 2010, 2, 490–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Archer, S.L. Mitochondrial Dynamics—Mitochondrial Fission and Fusion in Human Diseases. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013, 369, 2236–2251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Pietro, V.; Lazzarino, G.; Amorini, A.M.; Signoretti, S.; Hill, L.J.; Porto, E.; Tavazzi, B.; Lazzarino, G.; Belli, A. Fusion or Fission: The Destiny of Mitochondria In Traumatic Brain Injury of Different Severities. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 9189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youle, R.J.; van der Bliek, A.M. Mitochondrial Fission, Fusion, and Stress. Science 2012, 337, 1062–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westermann, B. Bioenergetic Role of Mitochondrial Fusion and Fission. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA)—Bioenerg. 2012, 1817, 1833–1838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bohovych, I.; Chan, S.S.L.; Khalimonchuk, O. Mitochondrial Protein Quality Control: The Mechanisms Guarding Mitochondrial Health. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2015, 22, 977–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Youle, R.J.; Karbowski, M. Mitochondrial Fission in Apoptosis. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2005, 6, 657–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashrafi, G.; Schwarz, T.L. The Pathways of Mitophagy for Quality Control and Clearance of Mitochondria. Cell Death Differ. 2013, 20, 31–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koyano, F.; Yamano, K.; Kosako, H.; Tanaka, K.; Matsuda, N. Parkin Recruitment to Impaired Mitochondria for Nonselective Ubiquitylation Is Facilitated by MITOL. J. Biol. Chem. 2019, 294, 10300–10314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Zhao, H.; Li, Y. Mitochondrial Dynamics in Health and Disease: Mechanisms and Potential Targets. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2023, 8, 333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.H. Intranasal Delivery of Mitochondrial Protein Humanin Rescues Cell Death and Promotes Mitochondrial Function in Parkinson’s Disease. Theranostics 2023, 13, 3330–3345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Li, F.; Xu, H.-B.; Luo, C.-X.; Wu, H.-Y.; Zhu, M.-M.; Lu, W.; Ji, X.; Zhou, Q.-G.; Zhu, D.-Y. Treatment of Cerebral Ischemia by Disrupting Ischemia-Induced Interaction of NNOS with PSD-95. Nat. Med. 2010, 16, 1439–1443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirza, F.J.; Zahid, S. The Role of Synapsins in Neurological Disorders. Neurosci. Bull. 2018, 34, 349–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guan, J.-S.; Haggarty, S.J.; Giacometti, E.; Dannenberg, J.-H.; Joseph, N.; Gao, J.; Nieland, T.J.F.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, X.; Mazitschek, R.; et al. HDAC2 Negatively Regulates Memory Formation and Synaptic Plasticity. Nature 2009, 459, 55–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donat, C.K.; Scott, G.; Gentleman, S.M.; Sastre, M. Microglial Activation in Traumatic Brain Injury. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2017, 9, 208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz-Ballester, C.; Robel, S. Astrocyte-mediated Mechanisms Contribute to Traumatic Brain Injury Pathology. WIREs Mech. Dis. 2023, 15, e1622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhong, Y.; Gu, L.; Ye, Y.; Zhu, H.; Pu, B.; Wang, J.; Li, Y.; Qiu, S.; Xiong, X.; Jian, Z. JAK2/STAT3 Axis Intermediates Microglia/Macrophage Polarization During Cerebral Ischemia/Reperfusion Injury. Neuroscience 2022, 496, 119–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Z.; Zhang, W.; Cao, Q.; Zou, L.; Fan, X.; Qi, C.; Yan, Y.; Song, B.; Wu, B. JAK2/STAT3 Pathway Regulates Microglia Polarization Involved in Hippocampal Inflammatory Damage Due to Acute Paraquat Exposure. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2022, 234, 113372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, X.; Qiu, Y.; Wight, A.E.; Kim, H.-J.; Cantor, H. Definition of a Mouse Microglial Subset That Regulates Neuronal Development and Proinflammatory Responses in the Brain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2022, 119, e2116241119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krasemann, S.; Madore, C.; Cialic, R.; Baufeld, C.; Calcagno, N.; El Fatimy, R.; Beckers, L.; O’Loughlin, E.; Xu, Y.; Fanek, Z.; et al. The TREM2-APOE Pathway Drives the Transcriptional Phenotype of Dysfunctional Microglia in Neurodegenerative Diseases. Immunity 2017, 47, 566–581.e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karve, I.P.; Taylor, J.M.; Crack, P.J. The Contribution of Astrocytes and Microglia to Traumatic Brain Injury. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2016, 173, 692–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sofroniew, M.V. Molecular Dissection of Reactive Astrogliosis and Glial Scar Formation. Trends Neurosci. 2009, 32, 638–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michinaga, S.; Koyama, Y. Pathophysiological Responses and Roles of Astrocytes in Traumatic Brain Injury. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 6418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulut, F.; Adam, M.; Özgen, A.; Hekim, M.G.; Ozcan, S.; Canpolat, S.; Ozcan, M. Protective Effects of Chronic Humanin Treatment in Mice with Diabetic Encephalopathy: A Focus on Oxidative Stress, Inflammation, and Apoptosis. Behav. Brain Res. 2023, 452, 114584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Primers | Forward | Reverse |

|---|---|---|

| mt-ND2 | GGGTGTGAGGGATTTCATCGT | TGCATGGCTCTGGTTACCTC |

| TFAM | GTCGCATCCCCTCGTCTATC | TTTCTGGTAGCTCCCTCCACA |

| HDAC2 | GTCTCGCTGGTGTTTTGCG | GCAGCCCTTCCATTTGAACC |

| SIRT1 | CGGCTACCGAGGTCCATATAC | AAC ATG GCT TGA GGG TCT GG |

| SIRT3 | GACTGGTCACGTAGCCTCAAG | ACAGAGGGATATGGGCCTTCT |

| NLRP3 | CAGCGATCAACAGGCGAGAC | AGAGATATCCCAGCAAACCTATCCA |

| Beclin | GCCTCTGAAACTGGACACGA | TAGCCTCTTCCTCCTGGGTC |

| SALL1 | TGTCAAGTTCCCAGAAATGTTCCA | ATGCCGCCGTTCTGAATGA |

| ITGAX(Cd11c) | CTGGATAGCCTTTCTTCTGCTG | GCACACTGTGTCCGAACTCA |

| Actin | ATGCTCCCCGGGCTGTAT | CATAGGAGTCCTTCTGACCCATTC |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Thapak, P.; Ying, Z.; Gomez-Pinilla, F. Enduring Effects of Humanin on Mitochondrial Systems in TBI Pathology. Biomolecules 2025, 15, 1705. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom15121705

Thapak P, Ying Z, Gomez-Pinilla F. Enduring Effects of Humanin on Mitochondrial Systems in TBI Pathology. Biomolecules. 2025; 15(12):1705. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom15121705

Chicago/Turabian StyleThapak, Pavan, Zhe Ying, and Fernando Gomez-Pinilla. 2025. "Enduring Effects of Humanin on Mitochondrial Systems in TBI Pathology" Biomolecules 15, no. 12: 1705. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom15121705

APA StyleThapak, P., Ying, Z., & Gomez-Pinilla, F. (2025). Enduring Effects of Humanin on Mitochondrial Systems in TBI Pathology. Biomolecules, 15(12), 1705. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom15121705