The Neuro-Melanoma Singularity: Convergent Evolution of Neural and Melanocytic Networks in Brain Metastatic Adaptation

Abstract

1. The Emergence of Neuro-Melanoma Convergence

Purpose, Methods, and Organization of This Review

2. Developmental Roots: Neural Crest Memory and Lineage Reactivation

2.1. Legacy of Neural Crest Developmental Innovation

2.2. Transcriptional and Epigenetic Reactivation in the Brain Microenvironment

2.3. Environmental Stimulation and Functional Consequences of Lineage Reactivation

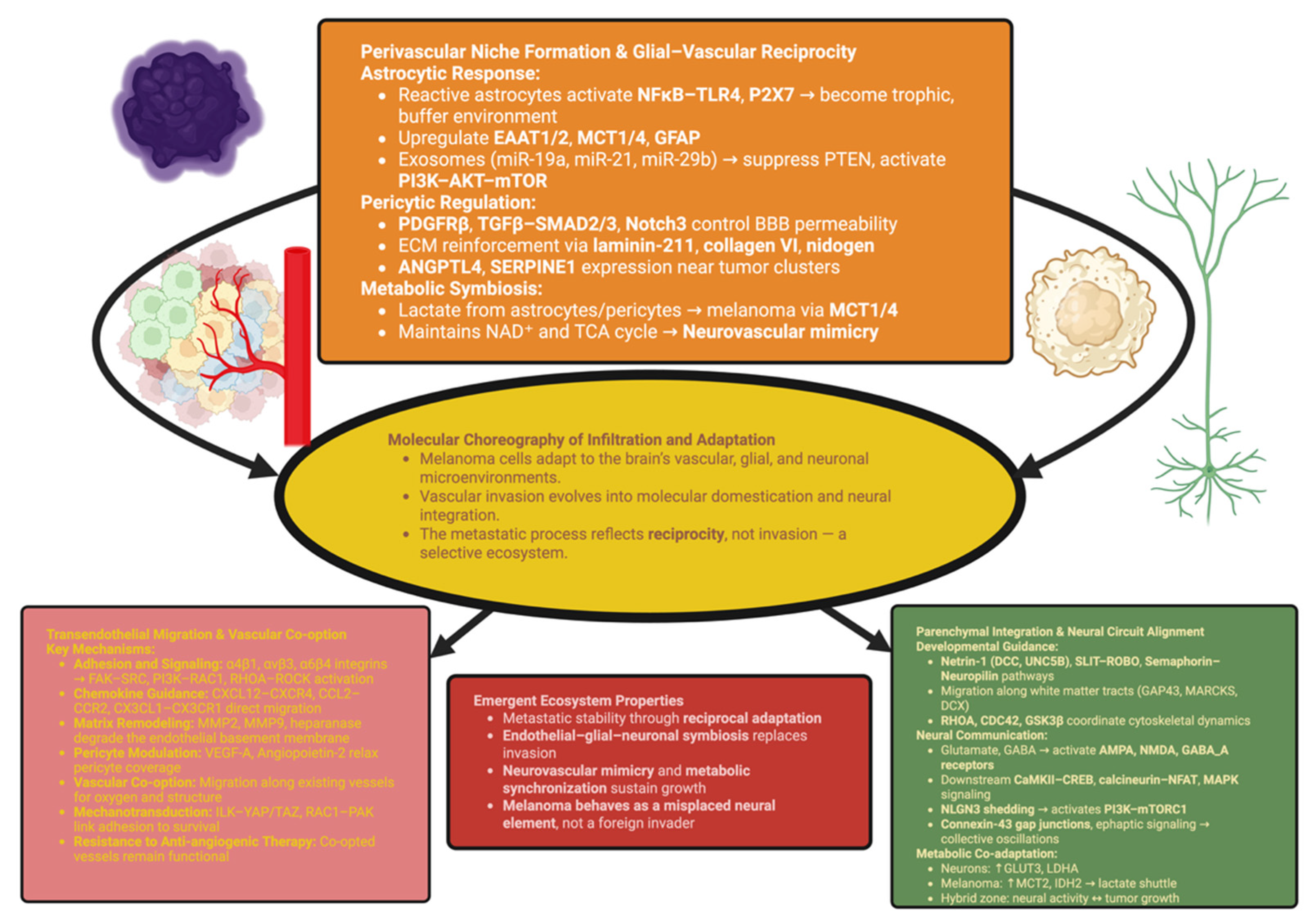

3. The Brain as a Selective Ecosystem: Molecular Choreography of Infiltration and Adaptation

3.1. Transendothelial Migration and Vascular Co-Option

3.2. Perivascular Niche Formation and Glial–Vascular Reciprocity

3.3. Parenchymal Integration and Neural Circuit Alignment

4. Synaptic Mimicry and Electrophysiological Coupling

4.1. Molecular Architecture of Melanoma–Neuron Junctions

4.2. Bioelectric Coupling and Network Synchronization

- Gap junction networks based on connexin. Connexin-43/30 heterotypic channels enable melanoma cells to communicate with astrocytes and establish equilibrium of local potassium and distribute second messengers (IP3 and cAMP) [99].

- Ephaptic microdomains. Tight juxtaposition of melanoma cell membranes to adjacent axon membranes facilitates contactless current transfer. Synchronous firing of neighboring axons imparts low-frequency potentials to melanoma membranes and thus synchronizes the timing of Ca2+ spikes [12].

- Purinergic lattices. Release of ATP from neurons and astrocytes activates P2X4/P2X7 on melanoma cells, generating rapid inward currents that regulate vesicle fusion and signaling related to the inflammasome; activation of metabotropic P2Y receptors regulates longer-term plasticity via activation of PLC-DAG-IP3 pathways [100].

- Adrenergic/cholinergic modulation. α7-nAChR microdomains on melanoma cells produce Ca2+ microtransients with high fidelity to cholinergic tone; β-adrenergic inputs regulate the PKA-EPAC axes that control the metabolic and electrical states of melanoma cells during arousal cycles [101].

4.3. Information Flow, Plasticity, and Circuit-Level Consequences

Synthesis

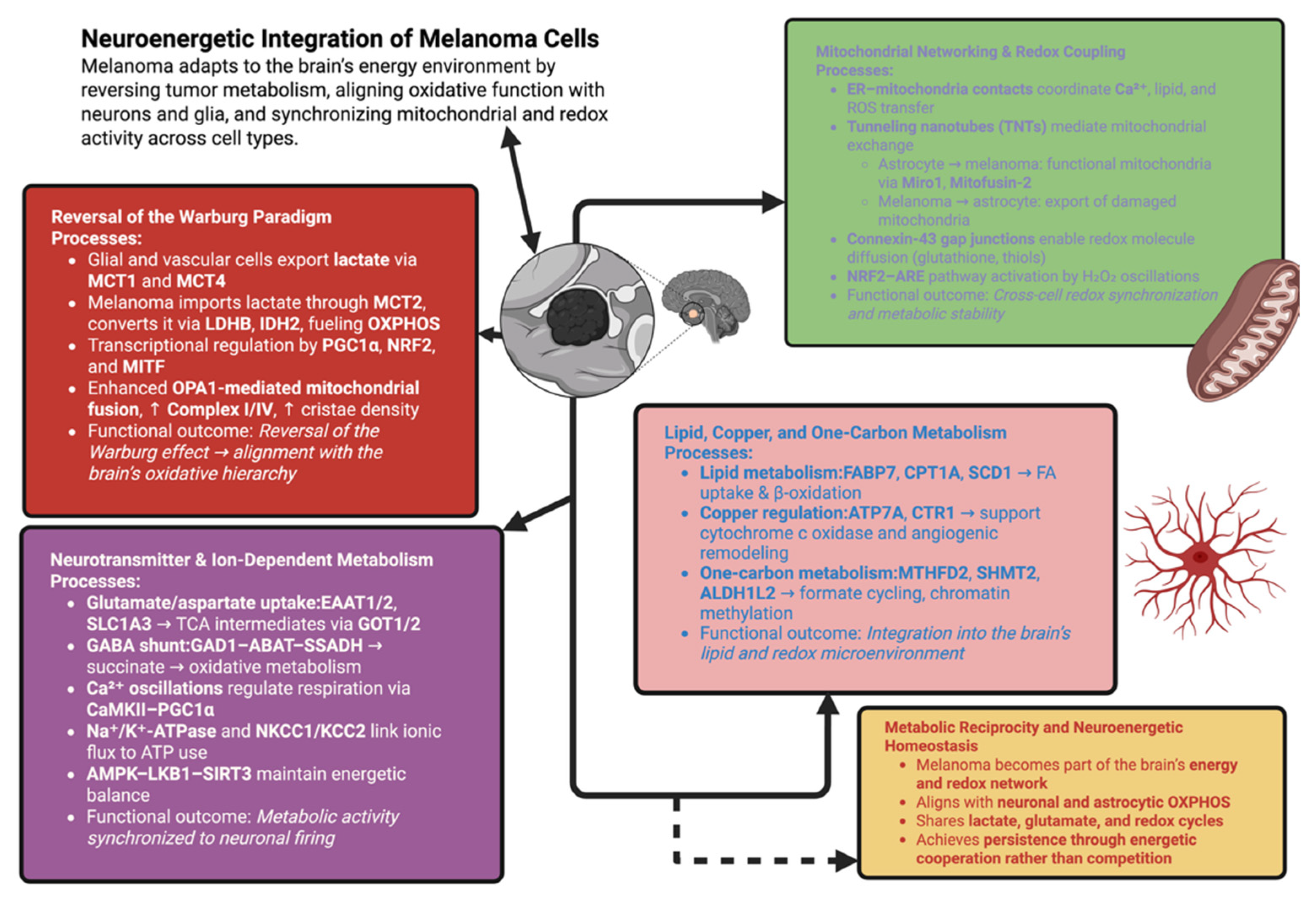

5. Metabolic Reprogramming and Neuroenergetic Integration

5.1. Reversal of the Warburg Paradigm in the Brain Microenvironment

5.2. Mitochondrial Networking and Redox Coupling

5.3. Neurotransmitter-Derived and Ion-Dependent Metabolism

5.4. Lipid, Copper, and One-Carbon Metabolism in Neural Adaptation

Synthesis

6. Immune Cross-Talk and Neuro-Immune Modulation

6.1. The Immunological Architecture of the Brain

6.2. Synaptic Immunity and Checkpoint Signaling

6.3. Micro-Glial and Astrocytic Reprogramming

6.4. Peripheral–Central Immune Interfaces

6.5. Neurotransmitter Modulation of Immunity

- Glutamate acts through mGluR3 and mGluR5 on micro-glial cells to decrease phagocytic activity and cytokine production, establishing an anti-inflammatory environment [165].

- Norepinephrine and dopamine, present in perivascular areas, interact with D2 and beta2-adrenergic receptors on immune cells to decrease antigen presentation and cytotoxic responses [166].

- Serotonin (5-HT) acting through 5-HT2A/1B regulates the release of cytokines and the activity of micro-glial cells, resulting in lower sensitivity to immune stimuli during periods of neural activity [167].

Synthesis

7. Network Thermodynamics and the Physics of Cognitive Stability

7.1. Targeting the Neuro-Melanocytic Interface

7.2. Modulation of Electro-Metabolic Coupling

7.3. Reawakening Immunity Through Neuro-Synaptic Checkpoint Control

7.4. Synthetic Vulnerabilities in Mitochondrial and Redox Networks

7.5. Circuit-Level and Chronobiological Interventions

Synthesis

8. Conclusions: The Quiet Architecture of Return

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rice, R.; Cebra-Thomas, J.; Haugas, M.; Partanen, J.; Rice, D.P.C.; Gilbert, S.F. Melanoblast Development Coincides with the Late Emerging Cells from the Dorsal Neural Tube in Turtle Trachemys Scripta. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 12063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tempone, M.H.; Borges-Martins, V.P.; César, F.; Alexandrino-Mattos, D.P.; de Figueiredo, C.S.; Raony, Í.; dos Santos, A.A.; Duarte-Silva, A.T.; Dias, M.S.; Freitas, H.R.; et al. The Healthy and Diseased Retina Seen through Neuron–Glia Interactions. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceol, C.J. Microenvironmental GABA Signaling Regulates Melanomagenesis through Reciprocal Melanoma–Keratinocyte Communication. Cancer Discov. 2023, 13, 2128–2130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Végh, A.G.; Fazakas, C.; Nagy, K.; Wilhelm, I.; Molnár, J.; Krizbai, I.A.; Szegletes, Z.; Váró, G. Adhesion and Stress Relaxation Forces between Melanoma and Cerebral Endothelial Cells. Eur. Biophys. J. EBJ 2012, 41, 139–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, P.; Goodrich, C.; Fu, C.; Dong, C. Melanoma Upregulates ICAM-1 Expression on Endothelial Cells through Engagement of Tumor CD44 with Endothelial E-Selectin and Activation of a PKCα–P38–SP-1 Pathway. FASEB J. 2014, 28, 4591–4609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruan, J.; McKee, K.K.; Yurchenco, P.D.; Yao, Y. Exogenous Laminin Exhibits a Unique Vascular Pattern in the Brain via Binding to Dystroglycan and Integrins. Fluids Barriers CNS 2022, 19, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stejerean-Todoran, I.; Zimmermann, K.; Gibhardt, C.S.; Vultur, A.; Ickes, C.; Shannan, B.; Bonilla del Rio, Z.; Wölling, A.; Cappello, S.; Sung, H.; et al. MCU Controls Melanoma Progression through a Redox-controlled Phenotype Switch. EMBO Rep. 2022, 23, e54746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balinda, H.U.; Sedgwick, A.; D’Souza-Schorey, C. Mechanisms Underlying Melanoma Invasion as a Consequence of MLK3 Loss. Exp. Cell Res. 2022, 415, 113106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nickerson, K.R.; Sammoura, F.M.; Zhou, Y.; Jaworski, A. Slit-Robo Signaling Supports Motor Neuron Avoidance of the Spinal Cord Midline through DCC Antagonism and Other Mechanisms. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2025, 13, 1563403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caruso, G.; Garcia Moreira, C.G.; Iaboni, E.; Tripodo, M.; Ferrarotto, R.; Abbritti, R.V.; Conte, L.; Caffo, M. Tumor Microenvironment in Melanoma Brain Metastasis: A New Potential Target? Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 5018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pu, T.; Sun, J.; Ren, G.; Li, H. Neuro-Immune Crosstalk in Cancer: Mechanisms and Therapeutic Implications. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2025, 10, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spurling, D.; Anchan, A.; Hucklesby, J.; Finlay, G.; Angel, C.E.; Graham, E.S. Melanoma Cells Produce Large Vesicular-Bodies That Cause Rapid Disruption of Brain Endothelial Barrier-Integrity and Disassembly of Junctional Proteins. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 6082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Maio, V.; Ventriglia, F.; Santillo, S. A Model of Cooperative Effect of AMPA and NMDA Receptors in Glutamatergic Synapses. Cogn. Neurodyn. 2016, 10, 315–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramachandran, R.; Jeans, A.F. Breaking Down Glioma-Microenvironment Crosstalk. Neuroscientist 2025, 31, 177–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marrapodi, R.; Kovacs, D.; Migliano, E.; Caputo, S.; Papaccio, F.; Pallara, T.; Cota, C.; Bellei, B. Melanoma–Keratinocyte Crosstalk Participates in Melanoma Progression with Mechanisms Partially Overlapping with Those of Cancer-Associated Fibroblasts. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 7901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Yan, T.; Huang, C.; Xu, Z.; Wang, L.; Jiang, E.; Wang, H.; Chen, Y.; Liu, K.; Shao, Z.; et al. Melanoma Cell-Secreted Exosomal miR-155-5p Induce Proangiogenic Switch of Cancer-Associated Fibroblasts via SOCS1/JAK2/STAT3 Signaling Pathway. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2018, 37, 242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strackeljan, L.; Baczynska, E.; Cangalaya, C.; Baidoe-Ansah, D.; Wlodarczyk, J.; Kaushik, R.; Dityatev, A. Microglia Depletion-Induced Remodeling of Extracellular Matrix and Excitatory Synapses in the Hippocampus of Adult Mice. Cells 2021, 10, 1862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biermann, J.; Melms, J.C.; Amin, A.D.; Wang, Y.; Caprio, L.A.; Karz, A.; Tagore, S.; Barrera, I.; Ibarra-Arellano, M.A.; Andreatta, M.; et al. Dissecting the Treatment-Naïve Ecosystem of Human Melanoma Brain Metastasis. Cell 2022, 185, 2591–2608.e30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radke, J.; Schumann, E.; Onken, J.; Koll, R.; Acker, G.; Bodnar, B.; Senger, C.; Tierling, S.; Möbs, M.; Vajkoczy, P.; et al. Decoding Molecular Programs in Melanoma Brain Metastases. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 7304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fager, A.; Samuelsson, M.; Olofsson Bagge, R.; Pivodic, A.; Bjursten, S.; Levin, M.; Jespersen, H.; Ny, L. Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor Therapy Is Associated with a Decreased Risk of Developing Melanoma Brain Metastases. BJC Rep. 2025, 3, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorodetska, I.; Schulz, A.; Behre, G.; Dubrovska, A. Confronting Melanoma Radioresistance: Mechanisms and Therapeutic Strategies. Cancers 2025, 17, 2648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonzano, E.; Barruscotti, S.; Chiellino, S.; Montagna, B.; Bonzano, C.; Imarisio, I.; Colombo, S.; Guerrini, F.; Saddi, J.; La Mattina, S.; et al. Current Treatment Paradigms for Advanced Melanoma with Brain Metastases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 3828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Liu, F.; Cai, Q.; Deng, L.; Ouyang, Q.; Zhang, X.H.-F.; Zheng, J. Invasion and Metastasis in Cancer: Molecular Insights and Therapeutic Targets. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2025, 10, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levin, M. The Computational Boundary of a “Self”: Developmental Bioelectricity Drives Multicellularity and Scale-Free Cognition. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 2688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabău, A.-H.; Tinca, A.-C.; Niculescu, R.; Cocuz, I.G.; Cozac-Szöke, A.R.; Lazar, B.A.; Chiorean, D.M.; Budin, C.E.; Cotoi, O.S. Cancer Stem Cells in Melanoma: Drivers of Tumor Plasticity and Emerging Therapeutic Strategies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 7419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Méndez-Maldonado, K.; Vega-López, G.A.; Aybar, M.J.; Velasco, I. Neurogenesis from Neural Crest Cells: Molecular Mechanisms in the Formation of Cranial Nerves and Ganglia. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2020, 8, 635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knyazeva, A.; Dyachuk, V. Neural Crest and Sons: Role of Neural Crest Cells and Schwann Cell Precursors in Development and Gland Embryogenesis. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2024, 12, 1406199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baloiu, A.I.; Filipoiu, F.; Toader, C.; Covache-Busuioc, R.-A.; Munteanu, O.; Serban, M. Sphenoid Sinus Hyperpneumatization: Anatomical Variants, Molecular Blueprints, and AI-Augmented Roadmaps for Skull Base Surgery. Front. Endocrinol. 2025, 16, 1634206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, K.J.; Niessen, C.M.; Rübsam, M.; Perez White, B.E.; Broussard, J.A. The Desmosome-Keratin Scaffold Integrates ErbB Family and Mechanical Signaling to Polarize Epidermal Structure and Function. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2022, 10, 903696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hon, G.C.; Rajagopal, N.; Shen, Y.; McCleary, D.F.; Yue, F.; Dang, M.D.; Ren, B. Adult Tissue Methylomes Harbor Epigenetic Memory at Embryonic Enhancers. Nat. Genet. 2013, 45, 1198–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spinella, F.; Caprara, V.; Cianfrocca, R.; Rosanò, L.; Di Castro, V.; Garrafa, E.; Natali, P.G.; Bagnato, A. The Interplay between Hypoxia, Endothelial and Melanoma Cells Regulates Vascularization and Cell Motility through Endothelin-1 and Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor. Carcinogenesis 2014, 35, 840–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Avitabile, M.; Succoio, M.; Testori, A.; Cardinale, A.; Vaksman, Z.; Lasorsa, V.A.; Cantalupo, S.; Esposito, M.; Cimmino, F.; Montella, A.; et al. Neural Crest-Derived Tumor Neuroblastoma and Melanoma Share 1p13.2 as Susceptibility Locus That Shows a Long-Range Interaction with the SLC16A1 Gene. Carcinogenesis 2020, 41, 284–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nygaard, V.; Prasmickaite, L.; Vasiliauskaite, K.; Clancy, T.; Hovig, E. Melanoma Brain Colonization Involves the Emergence of a Brain-Adaptive Phenotype. Oncoscience 2014, 1, 82–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rembiałkowska, N.; Rekiel, K.; Urbanowicz, P.; Mamala, M.; Marczuk, K.; Wojtaszek, M.; Żywica, M.; Radzevičiūtė-Valčiukė, E.; Novickij, V.; Kulbacka, J. Epigenetic Dysregulation in Cancer: Implications for Gene Expression and DNA Repair-Associated Pathways. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 6531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, L.B.; Van Swearingen, A.E.D.; Lee, M.R.; Rogers, L.W.; Sibley, A.B.; Sheng, J.; Zhang, D.; Qin, X.; Lipp, E.S.; Kumar, S.; et al. A Comprehensive, Multi-Center, Immunogenomic Analysis of Melanoma Brain Metastases. Acta Neuropathol. Commun. 2025, 13, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jäger, K.; Larribère, L.; Wu, H.; Weiss, C.; Gebhardt, C.; Utikal, J. Expression of Neural Crest Markers GLDC and ERRFI1 Is Correlated with Melanoma Prognosis. Cancers 2019, 11, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McConnell, A.M.; Mito, J.K.; Ablain, J.; Dang, M.; Formichella, L.; Fisher, D.E.; Zon, L.I. Neural Crest State Activation in NRAS Driven Melanoma, but Not in NRAS-Driven Melanocyte Expansion. Dev. Biol. 2019, 449, 107–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voicu, V.; Toader, C.; Șerban, M.; Covache-Busuioc, R.-A.; Ciurea, A.V. Systemic Neurodegeneration and Brain Aging: Multi-Omics Disintegration, Proteostatic Collapse, and Network Failure Across the CNS. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, X.; Luan, C.; Zhang, Z.; Wessely, A.; Heppt, M.V.; Berking, C.; Vera, J. SOX10, MITF, and microRNAs: Decoding Their Interplay in Regulating Melanoma Plasticity. Int. J. Cancer 2025, 157, 1277–1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunoh, S.; Nakashima, H.; Nakashima, K. Epigenetic Regulation of Neural Stem Cells in Developmental and Adult Stages. Epigenomes 2024, 8, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeinelabdeen, Y.; Abaza, T.; Yasser, M.B.; Elemam, N.M.; Youness, R.A. MIAT LncRNA: A Multifunctional Key Player in Non-Oncological Pathological Conditions. Non-Coding RNA Res. 2024, 9, 447–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiNapoli, S.E.; Martinez-McFaline, R.; Shen, H.; Doane, A.S.; Perez, A.R.; Verma, A.; Simon, A.; Nelson, I.; Balgobin, C.A.; Bourque, C.T.; et al. Histone 3 Methyltransferases Alter Melanoma Initiation and Progression Through Discrete Mechanisms. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2022, 10, 814216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alammari, F.; Al-Hujaily, E.M.; Alshareeda, A.; Albarakati, N.; Al-Sowayan, B.S. Hidden Regulators: The Emerging Roles of lncRNAs in Brain Development and Disease. Front. Neurosci. 2024, 18, 1392688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Váraljai, R.; Horn, S.; Sucker, A.; Piercianek, D.; Schmitt, V.; Carpinteiro, A.; Becker, K.A.; Reifenberger, J.; Roesch, A.; Felsberg, J.; et al. Integrative Genomic Analyses of Patient-Matched Intracranial and Extracranial Metastases Reveal a Novel Brain-Specific Landscape of Genetic Variants in Driver Genes of Malignant Melanoma. Cancers 2021, 13, 731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toader, C.; Serban, M.; Munteanu, O.; Covache-Busuioc, R.-A.; Enyedi, M.; Ciurea, A.V.; Tataru, C.P. From Synaptic Plasticity to Neurodegeneration: BDNF as a Transformative Target in Medicine. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 4271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Kuan, A.T.; Wang, W.; Herbert, Z.T.; Mosto, O.; Olukoya, O.; Adam, M.; Vu, S.; Kim, M.; Tran, D.; et al. Astrocyte-Neuron Crosstalk through Hedgehog Signaling Mediates Cortical Synapse Development. Cell Rep. 2022, 38, 110416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tagliaferro, M.; Ponti, D. The Signaling of Neuregulin-Epidermal Growth Factor Receptors and Its Impact on the Nervous System. Neuroglia 2023, 4, 253–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maneshi, M.M.; Toth, A.B.; Ishii, T.; Hori, K.; Tsujikawa, S.; Shum, A.K.; Shrestha, N.; Yamashita, M.; Miller, R.J.; Radulovic, J.; et al. Orai1 Channels Are Essential for Amplification of Glutamate-Evoked Ca2+ Signals in Dendritic Spines to Regulate Working and Associative Memory. Cell Rep. 2020, 33, 108464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trujillo, C.A.; Gao, R.; Negraes, P.D.; Gu, J.; Buchanan, J.; Preissl, S.; Wang, A.; Wu, W.; Haddad, G.G.; Chaim, I.A.; et al. Complex Oscillatory Waves Emerging from Cortical Organoids Model Early Human Brain Network Development. Cell Stem Cell 2019, 25, 558–569.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.-Q.; Dong, Z.-K.; Wang, Y.-F.; Jin, W.-L. Reprogramming Neural-Tumor Crosstalk: Emerging Therapeutic Dimensions and Targeting Strategies. Mil. Med. Res. 2025, 12, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinto, M.; Violante, S.; Cascão, R.; Faria, C.C. Unlocking the Role of Metabolic Pathways in Brain Metastatic Disease. Cells 2025, 14, 707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulesa, P.M.; Morrison, J.A.; Bailey, C.M. The Neural Crest and Cancer: A Developmental Spin on Melanoma. Cells Tissues Organs 2013, 198, 12–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, W.; Xu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Gao, D.; King, J.; Xu, Y.; Liang, F.-S. Investigating Crosstalk between H3K27 Acetylation and H3K4 Trimethylation in CRISPR/dCas-Based Epigenome Editing and Gene Activation. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 15912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Șerban, M.; Toader, C.; Covache-Busuioc, R.-A. CRISPR and Artificial Intelligence in Neuroregeneration: Closed-Loop Strategies for Precision Medicine, Spinal Cord Repair, and Adaptive Neuro-Oncology. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 9409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pronot, M.; Kieffer, F.; Gay, A.-S.; Debayle, D.; Forquet, R.; Poupon, G.; Schorova, L.; Martin, S.; Gwizdek, C. Proteomic Identification of an Endogenous Synaptic SUMOylome in the Developing Rat Brain. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2021, 14, 780535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Lu, F.; He, H.; Shen, J.; Messina, J.; Mathew, R.; Wang, D.; Sarnaik, A.A.; Chang, W.-C.; Kim, M.; et al. STIM1- and Orai1-Mediated Ca2+ Oscillation Orchestrates Invadopodium Formation and Melanoma Invasion. J. Cell Biol. 2014, 207, 535–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGrath, T.; Baskerville, R.; Rogero, M.; Castell, L. Emerging Evidence for the Widespread Role of Glutamatergic Dysfunction in Neuropsychiatric Diseases. Nutrients 2022, 14, 917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saltarin, F.; Wegmüller, A.; Bejarano, L.; Ildiz, E.S.; Zwicky, P.; Vianin, A.; Spadin, F.; Soukup, K.; Wischnewski, V.; Engelhardt, B.; et al. Compromised Blood-Brain Barrier Junctions Enhance Melanoma Cell Intercalation and Extravasation. Cancers 2023, 15, 5071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izraely, S.; Ben-Menachem, S.; Sagi-Assif, O.; Meshel, T.; Malka, S.; Telerman, A.; Bustos, M.A.; Ramos, R.I.; Pasmanik-Chor, M.; Hoon, D.S.B.; et al. The Melanoma Brain Metastatic Microenvironment: Aldolase C Partakes in Shaping the Malignant Phenotype of Melanoma Cells—A Case of Inter-tumor Heterogeneity. Mol. Oncol. 2021, 15, 1376–1390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toader, C.; Dumitru, A.V.; Eva, L.; Serban, M.; Covache-Busuioc, R.-A.; Ciurea, A.V. Nanoparticle Strategies for Treating CNS Disorders: A Comprehensive Review of Drug Delivery and Theranostic Applications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 13302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamiak-Nikolouzou, K.; Słomiński, A.T.; Skalska, Z.; Inkielewicz-Stępniak, I. Therapeutic Use of Integrin Signaling in Melanoma Cells: Physical Link with the Extracellular Matrix (ECM). Cancers 2025, 17, 3037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Bian, Y.; Chu, T.; Wang, Y.; Man, S.; Song, Y.; Wang, Z. The Role of Angiogenesis in Melanoma: Clinical Treatments and Future Expectations. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 1028647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanai, R.; Norton, E.; Stern, P.; Hynes, R.O.; Lamar, J.M. Identification of a Gene Signature That Predicts Dependence upon YAP/TAZ-TEAD. Cancers 2024, 16, 852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barkovskaya, A.; Buffone, A.; Žídek, M.; Weaver, V.M. Proteoglycans as Mediators of Cancer Tissue Mechanics. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2020, 8, 569377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anfuso, C.D.; Longo, A.; Distefano, A.; Amorini, A.M.; Salmeri, M.; Zanghì, G.; Giallongo, C.; Giurdanella, G.; Lupo, G. Uveal Melanoma Cells Elicit Retinal Pericyte Phenotypical and Biochemical Changes in an in Vitro Model of Coculture. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 5557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadhan, R.; Nath, K.; Basu, S.; Isidoro, C.; Song, Y.S.; Dhanasekaran, D.N. Decoding Lysophosphatidic Acid Signaling in Physiology and Disease: Mapping the Multimodal and Multinodal Signaling Networks. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2025, 10, 337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niveau, C.; Sosa Cuevas, E.; Saas, P.; Aspord, C. Glycans in Melanoma: Drivers of Tumour Progression but Sweet Targets to Exploit for Immunotherapy. Immunology 2024, 173, 33–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brás, M.M.; Radmacher, M.; Sousa, S.R.; Granja, P.L. Melanoma in the Eyes of Mechanobiology. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2020, 8, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Șerban, M.; Toader, C.; Covache-Busuioc, R.-A. The Collapse of Brain Clearance: Glymphatic-Venous Failure, Aquaporin-4 Breakdown, and AI-Empowered Precision Neurotherapeutics in Intracranial Hypertension. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 7223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashemi, G.; Dight, J.; Khosrotehrani, K.; Sormani, L. Melanoma Tumour Vascularization and Tissue-Resident Endothelial Progenitor Cells. Cancers 2022, 14, 4216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toader, C.; Serban, M.; Covache-Busuioc, R.-A.; Radoi, M.P.; Aljboor, G.S.R.; Costin, H.P.; Corlatescu, A.D.; Glavan, L.-A.; Gorgan, R.M. Cerebellar Cavernoma Resection: Case Report with Long-Term Follow-Up. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 7525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, W.; Wang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Guo, Y.; Li, Q.; Wei, X. Exosomal miR-130b-3p Promotes Progression and Tubular Formation Through Targeting PTEN in Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9, 616306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelsalam, M.; Ahmed, M.; Osaid, Z.; Hamoudi, R.; Harati, R. Insights into Exosome Transport through the Blood–Brain Barrier and the Potential Therapeutical Applications in Brain Diseases. Pharmaceuticals 2023, 16, 571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Cortés, M.; Delgado-Bellido, D.; Bermúdez-Jiménez, E.; Paramio, J.M.; O’Valle, F.; Vinckier, S.; Carmeliet, P.; Garcia-Diaz, A.; Oliver, F.J. PARP Inhibition Promotes Endothelial-like Traits in Melanoma Cells and Modulates Pericyte Coverage Dynamics during Vasculogenic Mimicry. J. Pathol. 2023, 259, 318–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Indini, A.; Grossi, F.; Mandalà, M.; Taverna, D.; Audrito, V. Metabolic Interplay between the Immune System and Melanoma Cells: Therapeutic Implications. Biomedicines 2021, 9, 607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Untiveros, G.; Raskind, A.; Linares, L.; Dotti, A.; Strizzi, L. Netrin-1 Stimulates Migration of Neogenin Expressing Aggressive Melanoma Cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 12751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luty, M.; Szydlak, R.; Pabijan, J.; Zemła, J.; Oevreeide, I.H.; Prot, V.E.; Stokke, B.T.; Lekka, M.; Zapotoczny, B. Tubulin-Targeted Therapy in Melanoma Increases the Cell Migration Potential by Activation of the Actomyosin Cytoskeleton─An In Vitro Study. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2024, 10, 7155–7166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krummel, D.A.P.; Nasti, T.H.; Kaluzova, M.; Kallay, L.; Bhattacharya, D.; Melms, J.C.; Izar, B.; Xu, M.; Burnham, A.; Ahmed, T.; et al. Melanoma Cell Intrinsic GABAA Receptor Enhancement Potentiates Radiation and Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor Response by Promoting Direct and T Cell-Mediated Anti-Tumor Activity. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2021, 109, 1040–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Șerban, M.; Toader, C.; Covache-Busuioc, R.-A. Blueprint of Collapse: Precision Biomarkers, Molecular Cascades, and the Engineered Decline of Fast-Progressing ALS. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 8072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keskinov, A.A.; Tapias, V.; Watkins, S.C.; Ma, Y.; Shurin, M.R.; Shurin, G.V. Impact of the Sensory Neurons on Melanoma Growth In Vivo. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0156095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paunikar, S.; Tamagnone, L. Connexin-43 in Cancer: Above and Beyond Gap Junctions! Cancers 2024, 16, 4191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Șerban, M.; Toader, C.; Covache-Busuioc, R.-A. Anatomy-Guided Microsurgical Resection of a Dominant Frontal Lobe Tumor Without Intraoperative Adjuncts: A Case Report from a Resource-Limited Context. Diagnostics 2025, 15, 2393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farah, C.; Mignion, L.; Jordan, B.F. Metabolic Profiling to Assess Response to Targeted and Immune Therapy in Melanoma. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 1725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nowacka, A.; Fajkiel-Madajczyk, A.; Ohla, J.; Woźniak-Dąbrowska, K.; Liss, S.; Gryczka, K.; Smuczyński, W.; Ziółkowska, E.; Bożiłow, D.; Śniegocki, M.; et al. Current Treatment of Melanoma Brain Metastases. Cancers 2023, 15, 4088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toader, C.; Tataru, C.P.; Munteanu, O.; Covache-Busuioc, R.-A.; Serban, M.; Ciurea, A.V.; Enyedi, M. Revolutionizing Neuroimmunology: Unraveling Immune Dynamics and Therapeutic Innovations in CNS Disorders. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 13614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tenchov, R.; Sasso, J.M.; Wang, X.; Zhou, Q.A. Aging Hallmarks and Progression and Age-Related Diseases: A Landscape View of Research Advancement. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2024, 15, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abate-Daga, D.; Ramello, M.C.; Smalley, I.; Forsyth, P.A.; Smalley, K.S.M. The Biology and Therapeutic Management of Melanoma Brain Metastases. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2018, 153, 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buga, A.-M.; Docea, A.O.; Albu, C.; Malin, R.D.; Branisteanu, D.E.; Ianosi, G.; Ianosi, S.L.; Iordache, A.; Calina, D. Molecular and Cellular Stratagem of Brain Metastases Associated with Melanoma. Oncol. Lett. 2019, 17, 4170–4175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuomela, K.; Ambrose, A.R.; Davis, D.M. Escaping Death: How Cancer Cells and Infected Cells Resist Cell-Mediated Cytotoxicity. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 867098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Liao, Q.; Wen, X.; Fan, J.; Yuan, T.; Tong, X.; Jia, R.; Chai, P.; Fan, X. Hijacking of the Nervous System in Cancer: Mechanism and Therapeutic Targets. Mol. Cancer 2025, 24, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrugia, B.L.; Melrose, J. The Glycosaminoglycan Side Chains and Modular Core Proteins of Heparan Sulphate Proteoglycans and the Varied Ways They Provide Tissue Protection by Regulating Physiological Processes and Cellular Behaviour. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 14101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toader, C.; Serban, M.; Covache-Busuioc, R.-A.; Radoi, M.P.; Aljboor, G.S.R.; Costin, H.P.; Ilie, M.-M.; Popa, A.A.; Gorgan, R.M. Single-Stage Microsurgical Clipping of Multiple Intracranial Aneurysms in a Patient with Cerebral Atherosclerosis: A Case Report and Review of Surgical Management. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maidorn, M.; Olichon, A.; Rizzoli, S.O.; Opazo, F. Nanobodies Reveal an Extra-Synaptic Population of SNAP-25 and Syntaxin 1A in Hippocampal Neurons. mAbs 2019, 11, 305–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costas-Insua, C.; Seijo-Vila, M.; Blázquez, C.; Blasco-Benito, S.; Rodríguez-Baena, F.J.; Marsicano, G.; Pérez-Gómez, E.; Sánchez, C.; Sánchez-Laorden, B.; Guzmán, M. Neuronal Cannabinoid CB1 Receptors Suppress the Growth of Melanoma Brain Metastases by Inhibiting Glutamatergic Signalling. Cancers 2023, 15, 2439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Roemeling, C.A.; Radisky, D.C.; Marlow, L.A.; Cooper, S.J.; Grebe, S.K.; Anastasiadis, P.Z.; Tun, H.W.; Copland, J.A. Neuronal Pentraxin 2 Supports Clear Cell Renal Cell Carcinoma by Activating the AMPA-Selective Glutamate Receptor-4. Cancer Res. 2014, 74, 4796–4810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toader, C.; Brehar, F.-M.; Radoi, M.P.; Serban, M.; Covache-Busuioc, R.-A.; Glavan, L.-A.; Ciurea, A.V.; Dobrin, N. The Microsurgical Resection of an Arteriovenous Malformation in a Patient with Thrombophilia: A Case Report and Literature Review. Diagnostics 2024, 14, 2613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alqabandi, J.A.; David, R.; Abdel-Motal, U.M.; ElAbd, R.O.; Youcef-Toumi, K. An Innovative Cellular Medicine Approach via the Utilization of Novel Nanotechnology-Based Biomechatronic Platforms as a Label-Free Biomarker for Early Melanoma Diagnosis. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 30107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sinha, M.; Narayanan, R. HCN Channels Enhance Spike Phase Coherence and Regulate the Phase of Spikes and LFPs in the Theta-Frequency Range. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, E2207–E2216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orellana, J.A.; Froger, N.; Ezan, P.; Jiang, J.X.; Bennett, M.V.L.; Naus, C.C.; Giaume, C.; Sáez, J.C. ATP and Glutamate Released via Astroglial Connexin 43 Hemichannels Mediate Neuronal Death through Activation of Pannexin 1 Hemichannels. J. Neurochem. 2011, 118, 826–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bockstiegel, J.; Engelhardt, J.; Weindl, G. P2X7 Receptor Activation Leads to NLRP3-Independent IL-1β Release by Human Macrophages. Cell Commun. Signal. 2023, 21, 335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bychkov, M.L.; Kirichenko, A.V.; Mikhaylova, I.N.; Paramonov, A.S.; Kirpichnikov, M.P.; Shulepko, M.A.; Lyukmanova, E.N. Extracellular Vesicles Derived from Metastatic Melanoma Cells Transfer A7-nAChR mRNA, Thus Increasing the Surface Expression of the Receptor and Stimulating the Growth of Normal Keratinocytes. Acta Nat. 2022, 14, 95–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiang, Y.; Artoni, P.; Seo, K.J.; Culaclii, S.; Hogan, V.; Zhao, X.; Zhong, Y.; Han, X.; Wang, P.-M.; Lo, Y.-K.; et al. Transparent Arrays of Bilayer-Nanomesh Microelectrodes for Simultaneous Electrophysiology and Two-Photon Imaging in the Brain. Sci. Adv. 2018, 4, eaat0626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toader, C.; Serban, M.; Covache-Busuioc, R.-A.; Radoi, M.P.; Ciurea, A.V.; Dobrin, N. Comprehensive Management of a Giant Left Frontal AVM Coexisting with a Bilobed PComA Aneurysm: A Case Report Highlighting Multidisciplinary Strategies and Advanced Neurosurgical Techniques. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abbasian, V.; Davoudi, S.; Vahabzadeh, A.; Maftoon-Azad, M.J.; Janahmadi, M. Astroglial Kir4.1 and AQP4 Channels: Key Regulators of Potassium Homeostasis and Their Implications in Autism Spectrum Disorders. Cell. Mol. Neurobiol. 2025, 45, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abreu, D.S.; Gomes, J.I.; Ribeiro, F.F.; Diógenes, M.J.; Sebastião, A.M.; Vaz, S.H. Astrocytes Control Hippocampal Synaptic Plasticity through the Vesicular-Dependent Release of D-Serine. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2023, 17, 1282841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Șerban, M.; Toader, C.; Covache-Busuioc, R.-A. Ruptured Posterior Inferior Cerebellar Artery Aneurysms: Integrating Microsurgical Expertise, Endovascular Challenges, and AI-Driven Risk Assessment. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 5374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagy-Pál, P.; Veres, J.M.; Fekete, Z.; Karlócai, M.R.; Weisz, F.; Barabás, B.; Reéb, Z.; Hájos, N. Structural Organization of Perisomatic Inhibition in the Mouse Medial Prefrontal Cortex. J. Neurosci. 2023, 43, 6972–6987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes-García, S.E.; Escobar, M.L. Calcineurin Participation in Hebbian and Homeostatic Plasticity Associated with Extinction. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2021, 15, 685838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Z.; Ogata, D.; Roszik, J.; Qin, Y.; Kim, S.-H.; Tetzlaff, M.T.; Lazar, A.J.; Davies, M.A.; Ekmekcioglu, S.; Grimm, E.A. iNOS Associates with Poor Survival in Melanoma: A Role for Nitric Oxide in the PI3K-AKT Pathway Stimulation and PTEN S-Nitrosylation. Front. Oncol. 2021, 11, 631766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, F.; Wu, X.; Zhou, J.; Lin, Y.; He, Y.; Fan, C.; Zeng, Z.; Xiong, W. Mitochondrial Transfer in Tunneling Nanotubes—A New Target for Cancer Therapy. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2024, 43, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mierke, C.T. Extracellular Matrix Cues Regulate Mechanosensing and Mechanotransduction of Cancer Cells. Cells 2024, 13, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andoh, M.; Shinoda, N.; Taira, Y.; Araki, T.; Kasahara, Y.; Takeuchi, H.; Miura, M.; Ikegaya, Y.; Koyama, R. Nonapoptotic Caspase-3 Guides C1q-Dependent Synaptic Phagocytosis by Microglia. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, W.; Liu, Z.; Jiang, X.; Chen, M.B.; Dong, H.; Liu, J.; Südhof, T.C.; Quake, S.R. Spatial Transcriptomics Reveal Neuron-Astrocyte Synergy in Long-Term Memory. Nature 2024, 627, 374–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Autréaux, F.; Chalazonitis, A.; Arumugam, D.; Gershon, T.; Gershon, M.D. Contribution of Neuroligin and Neurexin Alternative Splicing to the Establishment of Enteric Neuronal Synaptic Specificity. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2025, 329, G140–G158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalyana Sundaram, R.V.; Jin, H.; Li, F.; Shu, T.; Coleman, J.; Yang, J.; Pincet, F.; Zhang, Y.; Rothman, J.E.; Krishnakumar, S.S. Munc13 Binds and Recruits SNAP25 to Chaperone SNARE Complex Assembly. FEBS Lett. 2021, 595, 297–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, H.; Feng, Y.; Tang, J.; Yu, F.; Wang, Z.; Xu, J.; Hai, C.; Jiang, M.; Cheng, Y.; Shao, Z.; et al. Astrocyte-Secreted Cues Promote Neural Maturation and Augment Activity in Human Forebrain Organoids. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 2845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motori, E.; Atanassov, I.; Kochan, S.M.V.; Folz-Donahue, K.; Sakthivelu, V.; Giavalisco, P.; Toni, N.; Puyal, J.; Larsson, N.-G. Neuronal Metabolic Rewiring Promotes Resilience to Neurodegeneration Caused by Mitochondrial Dysfunction. Sci. Adv. 2020, 6, eaba8271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodner, O.; Radzishevsky, I.; Foltyn, V.N.; Touitou, A.; Valenta, A.C.; Rangel, I.F.; Panizzutti, R.; Kennedy, R.T.; Billard, J.M.; Wolosker, H. D-Serine Signaling and NMDAR-Mediated Synaptic Plasticity Are Regulated by System A-Type of Glutamine/D-Serine Dual Transporters. J. Neurosci. Off. J. Soc. Neurosci. 2020, 40, 6489–6502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, L.Y.; Cockshell, M.P.; Moore, E.; Myo Min, K.K.; Ortiz, M.; Johan, M.Z.; Ebert, B.; Ruszkiewicz, A.; Brown, M.P.; Ebert, L.M.; et al. Vasculogenic Mimicry Structures in Melanoma Support the Recruitment of Monocytes. Oncoimmunology 2022, 11, 2043673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gkintoni, E.; Vassilopoulos, S.P.; Nikolaou, G. Brain-Inspired Multisensory Learning: A Systematic Review of Neuroplasticity and Cognitive Outcomes in Adult Multicultural and Second Language Acquisition. Biomimetics 2025, 10, 397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, I.J.; Parikh, A.K.; Cohen, B.A. Melanoma Metabolism: Molecular Mechanisms and Therapeutic Implications in Cutaneous Oncology. Cancer Med. 2024, 13, e70386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pouyan, A.; Ghorbanlo, M.; Eslami, M.; Jahanshahi, M.; Ziaei, E.; Salami, A.; Mokhtari, K.; Shahpasand, K.; Farahani, N.; Meybodi, T.E.; et al. Glioblastoma Multiforme: Insights into Pathogenesis, Key Signaling Pathways, and Therapeutic Strategies. Mol. Cancer 2025, 24, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toader, C.; Brehar, F.M.; Radoi, M.P.; Serban, M.; Covache-Busuioc, R.-A.; Aljboor, G.S.; Gorgan, R.M. The Management of a Giant Convexity En Plaque Anaplastic Meningioma with Gerstmann Syndrome: A Case Report of Surgical Outcomes in a 76-Year-Old Male. Diagnostics 2024, 14, 2566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mancini, S.J.C.; Balabanian, K.; Corre, I.; Gavard, J.; Lazennec, G.; Le Bousse-Kerdilès, M.-C.; Louache, F.; Maguer-Satta, V.; Mazure, N.M.; Mechta-Grigoriou, F.; et al. Deciphering Tumor Niches: Lessons from Solid and Hematological Malignancies. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 766275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Șerban, M.; Toader, C.; Covache-Busuioc, R.-A. Precision Neuro-Oncology in Glioblastoma: AI-Guided CRISPR Editing and Real-Time Multi-Omics for Genomic Brain Surgery. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 7364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, S.; Yang, B. The Diverse Roles of Mitochondria in Regulating Cancer Metastasis. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2025, 47, 760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- In, G.K.; Ribeiro, J.R.; Yin, J.; Xiu, J.; Bustos, M.A.; Ito, F.; Chow, F.; Zada, G.; Hwang, L.; Salama, A.K.S.; et al. Multi-Omic Profiling Reveals Discrepant Immunogenic Properties and a Unique Tumor Microenvironment among Melanoma Brain Metastases. Npj Precis. Oncol. 2023, 7, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colby, L.; Preskitt, C.; Ho, J.S.; Balsara, K.; Wu, D. Brain Metastasis: A Literary Review of the Possible Relationship Between Hypoxia and Angiogenesis in the Growth of Metastatic Brain Tumors. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 7541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barba, I.; Carrillo-Bosch, L.; Seoane, J. Targeting the Warburg Effect in Cancer: Where Do We Stand? Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 3142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, F.; Yang, L.; Liu, J.; Wang, J.; Fan, L.; Duangmano, S.; Liu, H.; Liu, M.; Wang, J.; Zhong, X.; et al. The Role of Mitochondria in the Resistance of Melanoma to PD-1 Inhibitors. J. Transl. Med. 2023, 21, 345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toader, C.; Brehar, F.-M.; Radoi, M.P.; Serban, M.; Covache-Busuioc, R.-A.; Aljboor, G.S.; Gorgan, R.M. Stroke and Pulmonary Thromboembolism Complicating a Kissing Aneurysm in the M1 Segment of the Right MCA. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sassano, M.L.; Felipe-Abrio, B.; Agostinis, P. ER-Mitochondria Contact Sites; a Multifaceted Factory for Ca2+ Signaling and Lipid Transport. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2022, 10, 988014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannitti, G.; Paganoni, A.J.J.; Marchesi, S.; Garavaglia, R.; Fontana, F. Mitochondrial Bioenergetics and Networks in Melanoma: An Update. Apoptosis 2025, 30, 2042–2056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toader, C.; Tataru, C.P.; Munteanu, O.; Serban, M.; Covache-Busuioc, R.-A.; Ciurea, A.V.; Enyedi, M. Decoding Neurodegeneration: A Review of Molecular Mechanisms and Therapeutic Advances in Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, and ALS. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 12613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, L.; Qin, C.; Wu, J.; Jiang, H.; Xu, Q.; Chen, J.; Xu, X.; Zhang, X.; Guan, M.; Deng, X. The Crosstalk between Glutathione Metabolism and Non-Coding RNAs in Cancer Progression and Treatment Resistance. Redox Biol. 2025, 84, 103689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Șerban, M.; Toader, C.; Covache-Busuioc, R.-A. The Redox Revolution in Brain Medicine: Targeting Oxidative Stress with AI, Multi-Omics and Mitochondrial Therapies for the Precision Eradication of Neurodegeneration. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 7498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaconescu, I.B.; Dumitru, A.V.; Tataru, C.P.; Toader, C.; Șerban, M.; Covache-Busuioc, R.-A.; Eva, L. From Electron Imbalance to Network Collapse: Decoding the Redox Code of Ischemic Stroke for Biomarker-Guided Precision Neuroprotection. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 10835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apryatin, S.A. The Neurometabolic Function of the Dopamine–Aminotransferase System. Metabolites 2025, 15, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tagore, M.; Hergenreder, E.; Perlee, S.C.; Cruz, N.M.; Menocal, L.; Suresh, S.; Chan, E.; Baron, M.; Melendez, S.; Dave, A.; et al. GABA Regulates Electrical Activity and Tumor Initiation in Melanoma. Cancer Discov. 2023, 13, 2270–2291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elias, A.F.; Lin, B.C.; Piggott, B.J. Ion Channels in Gliomas—From Molecular Basis to Treatment. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 2530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil, D.; Laidler, P.; Zarzycka, M.; Dulińska-Litewka, J. Inhibition Effect of Chloroquine and Integrin-Linked Kinase Knockdown on Translation in Melanoma Cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 3682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aloia, A.; Müllhaupt, D.; Chabbert, C.D.; Eberhart, T.; Flückiger-Mangual, S.; Vukolic, A.; Eichhoff, O.; Irmisch, A.; Alexander, L.T.; Scibona, E.; et al. A Fatty Acid Oxidation-Dependent Metabolic Shift Regulates the Adaptation of BRAF-Mutated Melanoma to MAPK Inhibitors. Clin. Cancer Res. Off. J. Am. Assoc. Cancer Res. 2019, 25, 6852–6867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chrzan, N.; Hartman, M.L. Copper in Melanoma: At the Crossroad of Protumorigenic and Anticancer Roles. Redox Biol. 2025, 81, 103552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lionaki, E.; Ploumi, C.; Tavernarakis, N. One-Carbon Metabolism: Pulling the Strings behind Aging and Neurodegeneration. Cells 2022, 11, 214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tincu (Iurciuc), C.-E.; Andrițoiu, C.V.; Popa, M.; Ochiuz, L. Recent Advancements and Strategies for Overcoming the Blood–Brain Barrier Using Albumin-Based Drug Delivery Systems to Treat Brain Cancer, with a Focus on Glioblastoma. Polymers 2023, 15, 3969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Ta, Y.-N.N.; Chen, Y. Nanotechnology-Enhanced Immunotherapies for Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma: Challenges and Opportunities. Drug Deliv. Transl. Res. 2025, 15, 4067–4097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pallarés-Moratalla, C.; Bergers, G. The Ins and Outs of Microglial Cells in Brain Health and Disease. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1305087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogéa, G.M.R.; Silva-Carvalho, A.É.; Filiú-Braga, L.D.d.C.; Neves, F.d.A.R.; Saldanha-Araujo, F. The Inflammatory Status of Soluble Microenvironment Influences the Capacity of Melanoma Cells to Control T-Cell Responses. Front. Oncol. 2022, 12, 858425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geltz, A.; Geltz, J.; Kasprzak, A. Regulation and Function of Tumor-Associated Macrophages (TAMs) in Colorectal Cancer (CRC): The Role of the SRIF System in Macrophage Regulation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 5336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z.; Zhou, F.; Jin, H.; Wu, X. Crosstalk between CXCL12/CXCR4/ACKR3 and the STAT3 Pathway. Cells 2024, 13, 1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Covache-Busuioc, R.-A.; Toader, C.; Rădoi, M.P.; Șerban, M. Precision Recovery After Spinal Cord Injury: Integrating CRISPR Technologies, AI-Driven Therapeutics, Single-Cell Omics, and System Neuroregeneration. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 6966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kciuk, M.; Yahya, E.B.; Mohamed Ibrahim Mohamed, M.; Rashid, S.; Iqbal, M.O.; Kontek, R.; Abdulsamad, M.A.; Allaq, A.A. Recent Advances in Molecular Mechanisms of Cancer Immunotherapy. Cancers 2023, 15, 2721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arese, M.; Bussolino, F.; Pergolizzi, M.; Bizzozero, L. An Overview of the Molecular Cues and Their Intracellular Signaling Shared by Cancer and the Nervous System: From Neurotransmitters to Synaptic Proteins, Anatomy of an All-Inclusive Cooperation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 14695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.-T.; Wang, Y.-L.; Wang, S.; Li, J.-J.; He, W.; Fan, X.-J.; Wan, X.-B. Turning Cold Tumors into Hot Tumors to Ignite Immunotherapy. Mol. Cancer 2025, 24, 254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habibi, M.A.; Mirjani, M.S.; Ahmadvand, M.H.; Delbari, P.; Eftekhar, M.S.; Ghazizadeh, Y.; Ghezel, M.A.; Rad, R.H.; Vakili, K.G.; Lotfi, S.; et al. Anti-PD-1/PD-L1 Inhibitor Therapy for Melanoma Brain Metastases: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Neurosurg. Rev. 2024, 47, 434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanis, M.R.; Kim, S.; Schneck, J.P. Hydrogels in the Immune Context: In Vivo Applications for Modulating Immune Responses in Cancer Therapy. Gels 2025, 11, 889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karkempetzaki, A.I.; Schatton, T.; Barthel, S.R. Galectin-9—An Emerging Glyco-Immune Checkpoint Target for Cancer Therapy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 7998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koupourtidou, C.; Schwarz, V.; Aliee, H.; Frerich, S.; Fischer-Sternjak, J.; Bocchi, R.; Simon-Ebert, T.; Bai, X.; Sirko, S.; Kirchhoff, F.; et al. Shared Inflammatory Glial Cell Signature after Stab Wound Injury, Revealed by Spatial, Temporal, and Cell-Type-Specific Profiling of the Murine Cerebral Cortex. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 2866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Q.; Li, Z.; Li, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Gui, R.; Cui, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Qian, L.; Xiong, Y.; et al. Exosome-Derived microRNA: Implications in Melanoma Progression, Diagnosis and Treatment. Cancers 2022, 15, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doron, H.; Amer, M.; Ershaid, N.; Blazquez, R.; Shani, O.; Lahav, T.G.; Cohen, N.; Adler, O.; Hakim, Z.; Pozzi, S.; et al. Inflammatory Activation of Astrocytes Facilitates Melanoma Brain Tropism via the CXCL10-CXCR3 Signaling Axis. Cell Rep. 2019, 28, 1785–1798.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sikorski, H.; Żmijewski, M.A.; Piotrowska, A. Tumor Microenvironment in Melanoma—Characteristic and Clinical Implications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 6778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, F.; Wang, R.; Yi, Z.; Luo, P.; Liu, W.; Xie, Y.; Liu, Z.; Xia, Z.; Zhang, H.; Cheng, Q. Tissue Macrophages: Origin, Heterogenity, Biological Functions, Diseases and Therapeutic Targets. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2025, 10, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toader, C.; Serban, M.; Covache-Busuioc, R.-A.; Radoi, M.P.; Aljboor, G.S.R.; Glavan, L.-A.; Corlatescu, A.D.; Ilie, M.-M.; Gorgan, R.M. Navigating the Rare and Dangerous: Successful Clipping of a Superior Cerebellar Artery Aneurysm Against the Odds of Uncontrolled Hypertension. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 7430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, K.M.; Amouzgar, M.; Pfeiffer, S.M.; Howes, T.R.; Medina, E.; Travers, M.; Steiner, G.; Weber, J.S.; Wolchok, J.D.; Larkin, J.; et al. Prior Anti-CTLA-4 Therapy Impacts Molecular Characteristics Associated with Anti-PD-1 Response in Advanced Melanoma. Cancer Cell 2023, 41, 791–806.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balbi, M.; Bonanno, G.; Bonifacino, T.; Milanese, M. The Physio-Pathological Role of Group I Metabotropic Glutamate Receptors Expressed by Microglia in Health and Disease with a Focus on Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 5240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodo, T.W.; de Aquino, M.T.P.; Shimamoto, A.; Shanker, A. Critical Neurotransmitters in the Neuroimmune Network. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 1869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, N.; Zhang, L.; Zhuang, Y.; Xin, Q.; Gu, X.; Jiang, C.; Wu, J. Serotonin (5-Hydroxytryptamine): Metabolism, Signaling, Biological Functions, Diseases, and Emerging Therapeutic Opportunities. MedComm 2025, 6, e70383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Wu, Y.; Lv, X.; Liu, S.; Yuan, Z.; Chen, Y.; Ding, X.; Li, Z.; Wang, X. Neurotransmitters: An Emerging Target for Therapeutic Resistance to Tumor Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors. Mol. Cancer 2025, 24, 216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Baena, F.J.; Marquez-Galera, A.; Ballesteros-Martinez, P.; Castillo, A.; Diaz, E.; Moreno-Bueno, G.; Lopez-Atalaya, J.P.; Sanchez-Laorden, B. Microglial Reprogramming Enhances Antitumor Immunity and Immunotherapy Response in Melanoma Brain Metastases. Cancer Cell 2025, 43, 413–427.e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poljsak, B.; Kovac, V.; Dahmane, R.; Levec, T.; Starc, A. Cancer Etiology: A Metabolic Disease Originating from Life’s Major Evolutionary Transition? Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2019, 2019, 7831952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Internò, V.; Sergi, M.C.; Metta, M.E.; Guida, M.; Trerotoli, P.; Strippoli, S.; Circelli, S.; Porta, C.; Tucci, M. Melanoma Brain Metastases: A Retrospective Analysis of Prognostic Factors and Efficacy of Multimodal Therapies. Cancers 2023, 15, 1542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prakash, R.; Izraely, S.; Thareja, N.S.; Lee, R.H.; Rappaport, M.; Kawaguchi, R.; Sagi-Assif, O.; Ben-Menachem, S.; Meshel, T.; Machnicki, M.; et al. Regeneration Enhances Metastasis: A Novel Role for Neurovascular Signaling in Promoting Melanoma Brain Metastasis. Front. Neurosci. 2019, 13, 297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toader, C.; Brehar, F.M.; Radoi, M.P.; Covache-Busuioc, R.A.; Serban, M.; Ciurea, A.V.; Dobrin, N. Challenging Management of a Rare Complex Cerebral Arteriovenous Malformation in the Corpus Callosum and Post-Central Gyrus: A Case Study of a 41-Year-Old Female. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 7494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacome, M.A.; Wu, Q.; Chen, J.; Mohamed, Z.S.; Mokhtari, S.; Piña, Y.; Etame, A.B. Molecular Underpinnings of Brain Metastases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 2307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isaak, A.J.; Clements, G.R.; Buenaventura, R.G.M.; Merlino, G.; Yu, Y. Development of Personalized Strategies for Precisely Battling Malignant Melanoma. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 5023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tittarelli, A.; Pereda, C.; Gleisner, M.A.; López, M.N.; Flores, I.; Tempio, F.; Lladser, A.; Achour, A.; González, F.E.; Durán-Aniotz, C.; et al. Long-Term Survival and Immune Response Dynamics in Melanoma Patients Undergoing TAPCells-Based Vaccination Therapy. Vaccines 2024, 12, 357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putnam, A.J.; Schulz, V.V.; Freiter, E.M.; Bill, H.M.; Miranti, C.K. Src, PKCα, and PKCδ Are Required for Avβ3 Integrin-Mediated Metastatic Melanoma Invasion. Cell Commun. Signal. 2009, 7, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, N.-N.; Li, X.-B.; Zhang, M.; Han, C.; Fan, X.-Y.; Huang, S.-H. NLGN3 Upregulates Expression of ADAM10 to Promote the Cleavage of NLGN3 via Activating the LYN Pathway in Human Gliomas. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9, 662763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuzaka, Y.; Yashiro, R. Classification and Molecular Functions of Heparan Sulfate Proteoglycans and Their Molecular Mechanisms with the Receptor. Biologics 2024, 4, 105–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Duan, M.; Lu, Q.; Liu, J.; He, M.; Zhang, Y. Advances in Neuroscientific Mechanisms and Therapies for Glioblastoma. iScience 2025, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Wang, T.; Jiang, X.; Li, M.; He, X.; Ma, Y.; Li, X.; Jin, W.; Jiao, Z. Integrating Neuroscience and Oncology: Neuroimmune Crosstalk in the Initiation and Progression of Digestive System Tumors. Mol. Cancer 2025, 24, 215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koda, S.; Hu, J.; Ju, X.; Sun, G.; Shao, S.; Tang, R.-X.; Zheng, K.-Y.; Yan, J. The Role of Glutamate Receptors in the Regulation of the Tumor Microenvironment. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1123841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boxer, E.E.; Aoto, J. Neurexins and Their Ligands at Inhibitory Synapses. Front. Synaptic Neurosci. 2022, 14, 1087238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumann, E.K. Spatial Multiomics Toward Understanding Neurological Systems. J. Mass Spectrom. 2025, 60, e5143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomaszewski, W.H.; Waibl-Polania, J.; Chakraborty, M.; Perera, J.; Ratiu, J.; Miggelbrink, A.; McDonnell, D.P.; Khasraw, M.; Ashley, D.M.; Fecci, P.E.; et al. Neuronal CaMKK2 Promotes Immunosuppression and Checkpoint Blockade Resistance in Glioblastoma. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 6483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koltai, T.; Fliegel, L. Exploring Monocarboxylate Transporter Inhibition for Cancer Treatment. Explor. Target. Anti-Tumor Ther. 2024, 5, 135–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koren, T.; Rolls, A. Immunoception: Defining Brain-Regulated Immunity. Neuron 2022, 110, 3425–3428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.S.; Yassin, S.; Lin, A.Y. Utilization of Exosome-Based Therapies to Augment Anti-PD-1/PD-L1 Therapies. J. Immunother. Cancer 2025, 13, e010603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- León-Rodríguez, A.; Grondona, J.M.; Marín-Wong, S.; López-Aranda, M.F.; López-Ávalos, M.D. Long-Term Reprogramming of Primed Microglia after Moderate Inhibition of CSF1R Signaling. Glia 2025, 73, 175–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.-F.; Wang, T.-T.; Huang, R.-Z.; Tan, Y.-T.; Chen, D.-L.; Ju, H.-Q. PANoptosis in Cancer: Bridging Molecular Mechanisms to Therapeutic Innovations. Cell. Mol. Immunol. 2025, 22, 996–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pujalte-Martin, M.; Belaïd, A.; Bost, S.; Kahi, M.; Peraldi, P.; Rouleau, M.; Mazure, N.M.; Bost, F. Targeting Cancer and Immune Cell Metabolism with the Complex I Inhibitors Metformin and IACS-010759. Mol. Oncol. 2024, 18, 1719–1738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nardin, C.; Peres, C.; Putti, S.; Orsini, T.; Colussi, C.; Mazzarda, F.; Raspa, M.; Scavizzi, F.; Salvatore, A.M.; Chiani, F.; et al. Connexin Hemichannel Activation by S-Nitrosoglutathione Synergizes Strongly with Photodynamic Therapy Potentiating Anti-Tumor Bystander Killing. Cancers 2021, 13, 5062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Șerban, M.; Toader, C.; Covache-Busuioc, R.-A. Brain Tumors, AI and Psychiatry: Predicting Tumor-Associated Psychiatric Syndromes with Machine Learning and Biomarkers. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 8114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toader, C.; Serban, M.; Eva, L.; Costea, D.; Covache-Busuioc, R.-A.; Radoi, M.P.; Ciurea, A.V.; Dumitru, A.V. Large Pontine Cavernoma with Hemorrhage: Case Report on Surgical Approach and Recovery. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 2358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guerra, A.; Bologna, M. Low-Intensity Transcranial Ultrasound Stimulation: Mechanisms of Action and Rationale for Future Applications in Movement Disorders. Brain Sci. 2022, 12, 611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, A.L.; Benguigui, M.; Fornetti, J.; Goddard, E.; Lucotti, S.; Insua-Rodríguez, J.; Wiegmans, A.P. Current Challenges in Metastasis Research and Future Innovation for Clinical Translation. Clin. Exp. Metastasis 2022, 39, 263–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bravo, F.; Glogowski, J.; Stamatakis, E.A.; Herfert, K. Dissonant Music Engages Early Visual Processing. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2024, 121, e2320378121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Level of Organization | Key Features and Mechanisms | Physiological/Pathophysiological Context | Experimental or Clinical Correlates | Representative References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Epigenetic and transcriptional reactivation | Reopening of neural crest enhancers via H3K27ac deposition and SWI/SNF (BAF53B and ACTL6B) remodeling; cyclic SOX10–MITF–BRN2 triad maintains metastable melanocytic–neuroadaptive states | Reactivation of developmental chromatin landscapes under neural morphogen exposure (WNT7A, SHH, BDNF) | ATAC-seq, ChIP-seq, and scRNA-seq showing enhancer reactivation and lineage cycling in brain metastases | [53] |

| Transcriptional circuitry and non-coding regulation | Coordinated expression of proneural (ASCL1 and NEUROD1) and neural crest (SOX10, PAX3, FOXD3) genes; regulation by lncRNAs (SAMMSON and NEAT1) and miRNAs (miR-211 and miR-182/183/96) | Balances oxidative stress, migration, and neuroplastic signaling Within the brain microenvironment | Multi-omics and CRISPR perturbation studies revealing ncRNA–transcription factor coupling | [54] |

| Neuroadaptive proteomic convergence | De novo expression of synaptic proteins (NLGN3, CNTNAP2, SYN1, STXBP1) and vesicular fusion machinery (VAMP2 and RIM1) | Enables pseudo-synaptic coupling and neurotransmitter-mediated communication between melanoma and neurons | Proteomics and EM imaging demonstrating synaptic mimicry in intracranial metastases | [55] |

| Electrochemical and biomechanical signaling | ORAI1–STIM1 and TRPM7/TRPV4-mediated Ca2+ oscillations; integrin–laminin–FAK axis restores polarity and guides perivascular migration | Electric and mechanical feedback synchronizes melanoma clusters with local neuronal rhythms | Microelectrode array recordings and live-cell calcium imaging in co-culture systems | [56] |

| Systems-level integration and metastasis phenotype | Emergence of hybrid “neural–melanocytic” state capable of neurotransmitter release (glutamate and ATP) and metabolic coupling with glia | Establishes partially integrated neural subsystems that exploit neuronal circuitry for survival and spread | In vivo imaging and metabolic tracing of functional connectivity within metastases | [57] |

| Phase | Core Mechanisms and Molecular Features | Functional Integration Within Neural Microenvironment | Emergent Biological Consequences | Representative References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| I. Junctional Genesis | Assembly of neurexin–neuroligin, LRRTM, and Slitrk complexes; selective heparan sulfate editing modulates adhesion specificity; bidirectional Eph–ephrin signaling organizes actin geometry and intercellular spacing | Establishes pseudo-synaptic interfaces that recapitulate excitatory and inhibitory synaptic architectures | Anchors melanoma cells to neuronal membranes and primes bidirectional neurotransmission | [114] |

| II. Vesicular Autonomy | SNARE-driven vesicle priming (syntaxin-1A, SNAP25, VAMP2) with Munc13/UNC13 scaffolding; PSD enrichment (DLG4, CaMKII, calcineurin); dual glutamatergic and GABAergic receptor sets | Enables semi-autonomous vesicle cycling and receptor-dependent responsiveness to neuronal activity | Melanoma gains capacity for chemical signaling and feedback modulation of local circuits | [115] |

| III. Astrocytic Maturation and Matrix Remodeling | Co-option of thrombospondin-1/2, hevin, and glypican 4/6; neuronal pentraxins increase receptor density; tumor-secreted metalloproteases reshape perisynaptic ECM (brevican and aggrecan) | Astrocyte-derived cues drive functional maturation of hybrid junctions and diffusion-regulated signal stability | Produces structurally competent and electrically responsive tumor–neuron synapses | [116] |

| IV. Bioelectric Coupling and Metabolic Synchrony | Connexin-43/30 gap junctions enable astrocytic cross-talk; ephaptic coupling mediates field transfer; Ca2+ dynamics via ORAI1–STIM1 and TRPM7/TRPV4; mitochondrial oscillations through OPA1–DRP1 feedback | Establishes electro-metabolic coherence, synchronizing ionic flux with mitochondrial ATP output | Enables sustained signaling and mesoscopic synchronization with neighboring neuronal populations | [117] |

| V. Circuit Plasticity and Information Exchange | Melanoma-mediated release of D-serine, glutamate, and ATP modulates dendritic thresholds; Hebbian-like plasticity (CaMKII–stargazin, calcineurin); TNT-mediated long-range coupling; LOX-driven mechanoelectrical tuning | Melanoma participates in dynamic circuit adaptation and feedback regulation of excitatory–inhibitory balance | Hybrid motifs (neuron–melanoma–astrocyte) sustain tumor survival while preserving circuit homeostasis | [118] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Atanasescu, V.-P.; Breazu, A.; Oprea, S.; Porosnicu, A.-L.; Oproiu, A.; Rădoi, M.-P.; Munteanu, O.; Pantu, C. The Neuro-Melanoma Singularity: Convergent Evolution of Neural and Melanocytic Networks in Brain Metastatic Adaptation. Biomolecules 2025, 15, 1683. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom15121683

Atanasescu V-P, Breazu A, Oprea S, Porosnicu A-L, Oproiu A, Rădoi M-P, Munteanu O, Pantu C. The Neuro-Melanoma Singularity: Convergent Evolution of Neural and Melanocytic Networks in Brain Metastatic Adaptation. Biomolecules. 2025; 15(12):1683. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom15121683

Chicago/Turabian StyleAtanasescu, Vlad-Petre, Alexandru Breazu, Stefan Oprea, Andrei-Ludovic Porosnicu, Anamaria Oproiu, Mugurel-Petrinel Rădoi, Octavian Munteanu, and Cosmin Pantu. 2025. "The Neuro-Melanoma Singularity: Convergent Evolution of Neural and Melanocytic Networks in Brain Metastatic Adaptation" Biomolecules 15, no. 12: 1683. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom15121683

APA StyleAtanasescu, V.-P., Breazu, A., Oprea, S., Porosnicu, A.-L., Oproiu, A., Rădoi, M.-P., Munteanu, O., & Pantu, C. (2025). The Neuro-Melanoma Singularity: Convergent Evolution of Neural and Melanocytic Networks in Brain Metastatic Adaptation. Biomolecules, 15(12), 1683. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom15121683