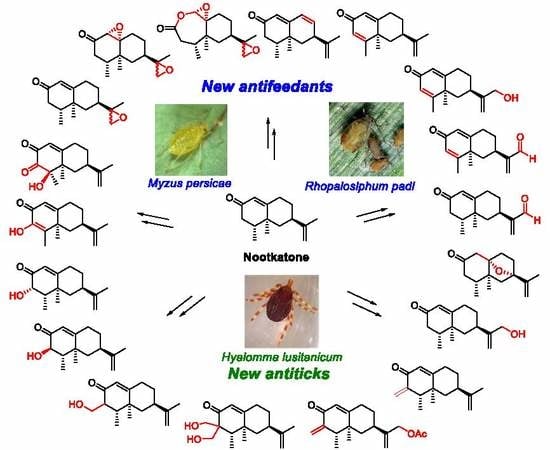

Novel Insect Antifeedant and Ixodicidal Nootkatone Derivatives

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Experimental

2.1. Chemicals and Instrument

2.2. Synthesis of Nootkatone Derivatives (See Table 1, Scheme 1)

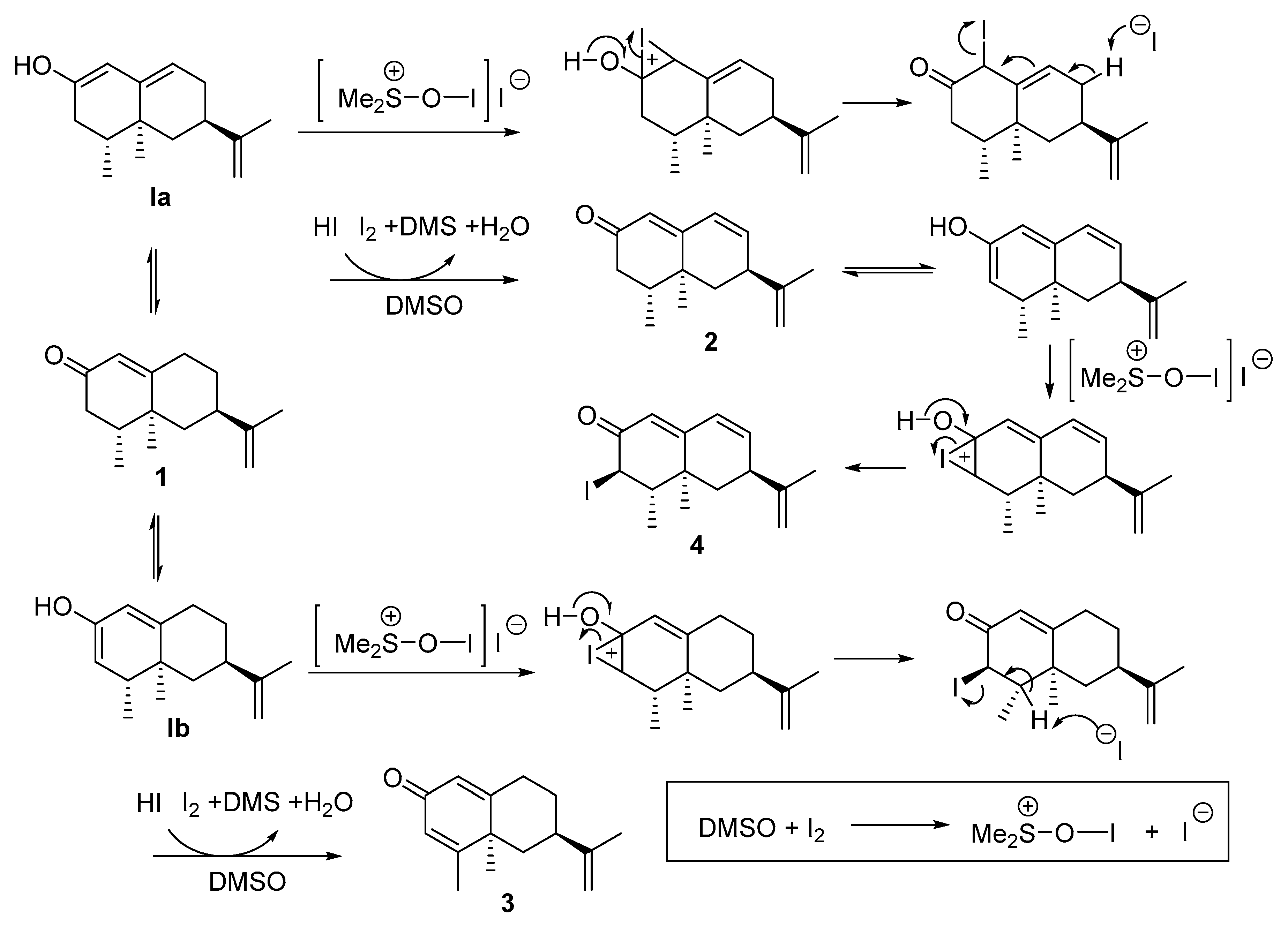

2.2.1. Dehydrogenation of Nootkatone with the System I2/Dimethysulfoxide (DMSO)

2.2.2. Dehydrogenation of 1 with 2,3-dichloro-5,6-dicyanobenzoquinone (DDQ)

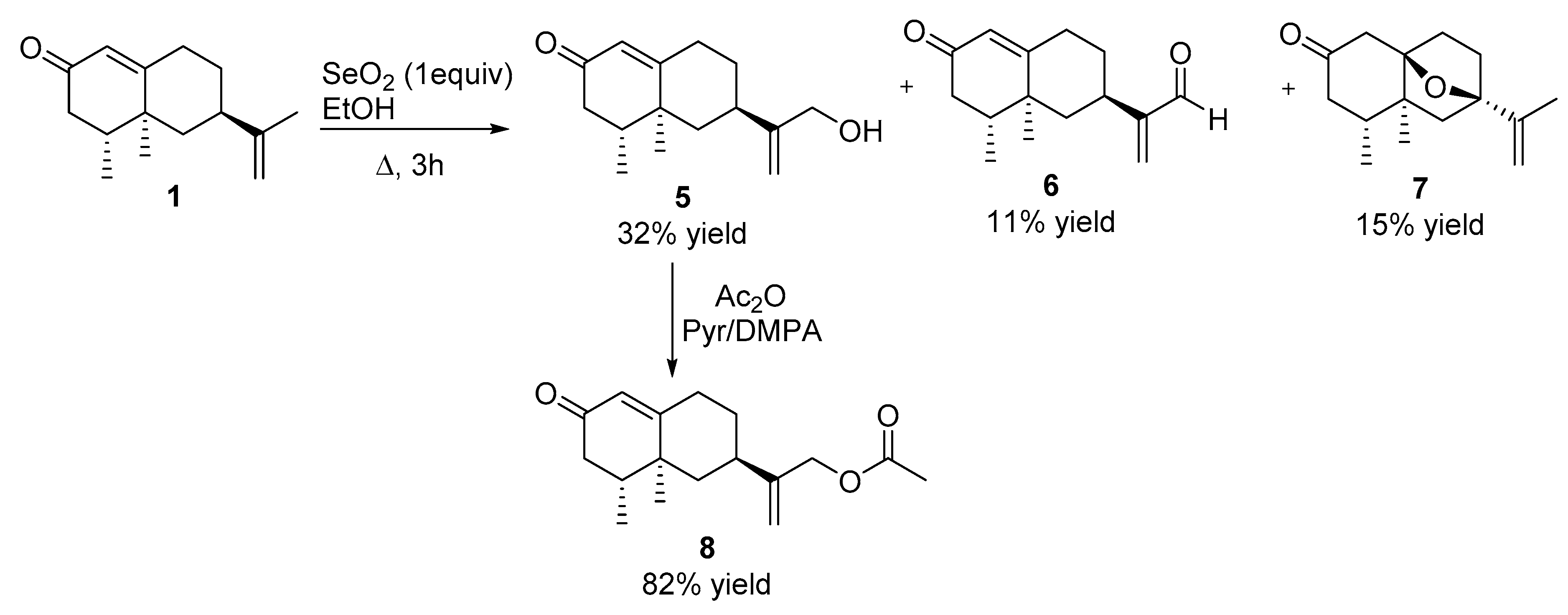

2.2.3. Reaction of Nootkatone with SeO2 (See Scheme 2)

2.2.4. Acetylation of Compound 5

2.2.5. Reaction of Compound 3 with SeO2 (See Scheme 3)

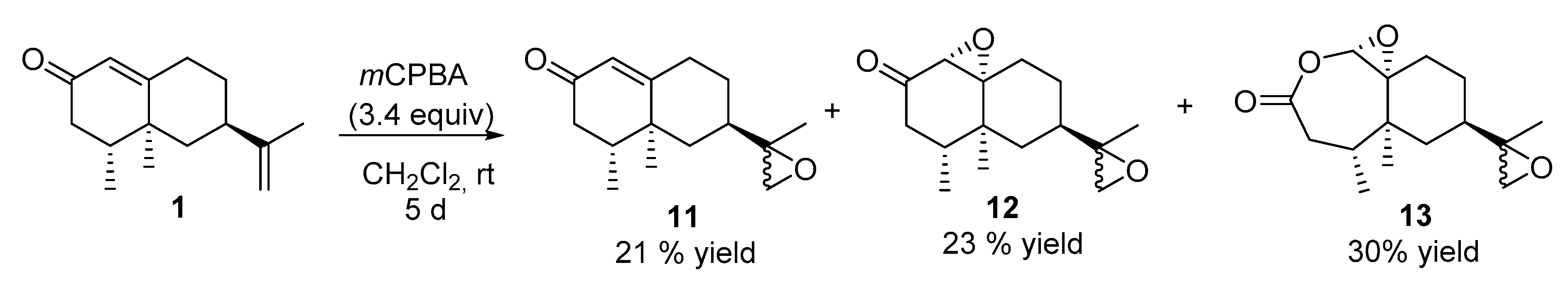

2.2.6. Reaction of Nootkatone with mchloroperbenzoic Acid (mCPBA) (See Scheme 4)

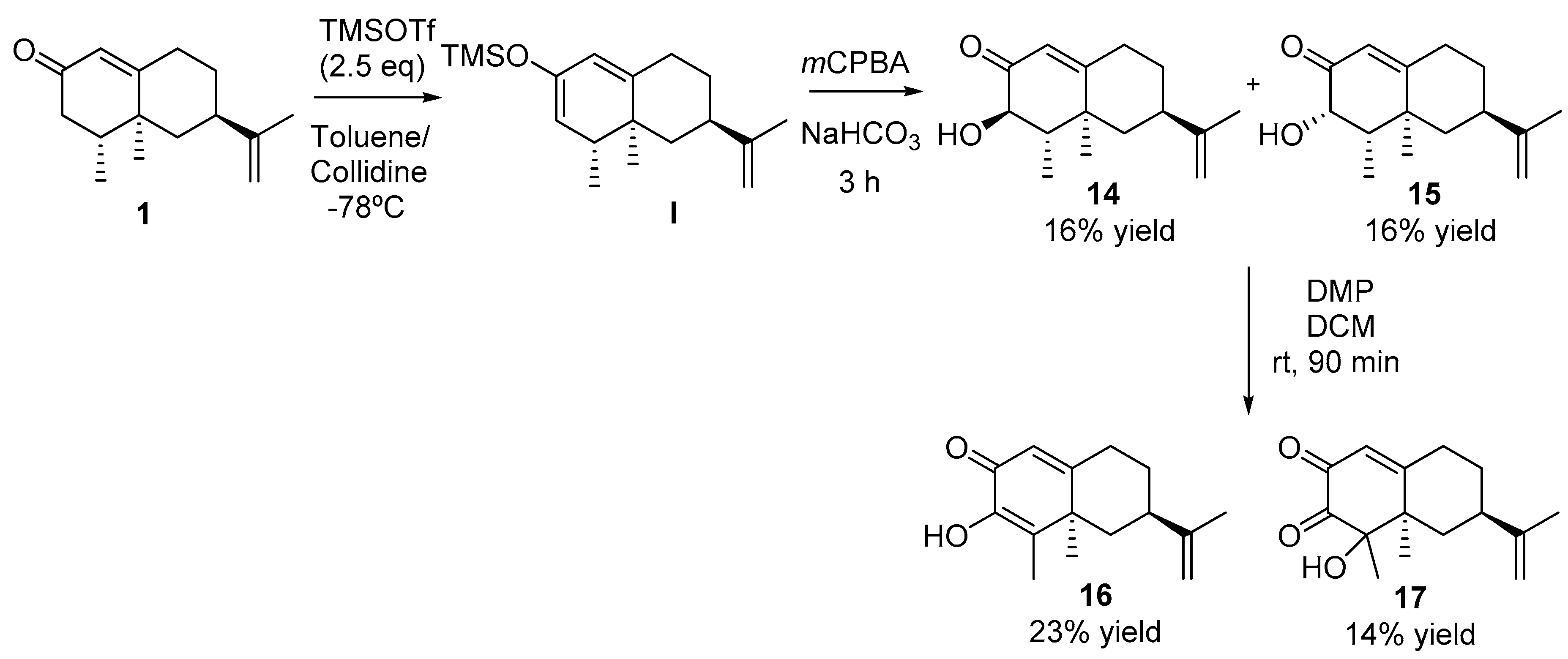

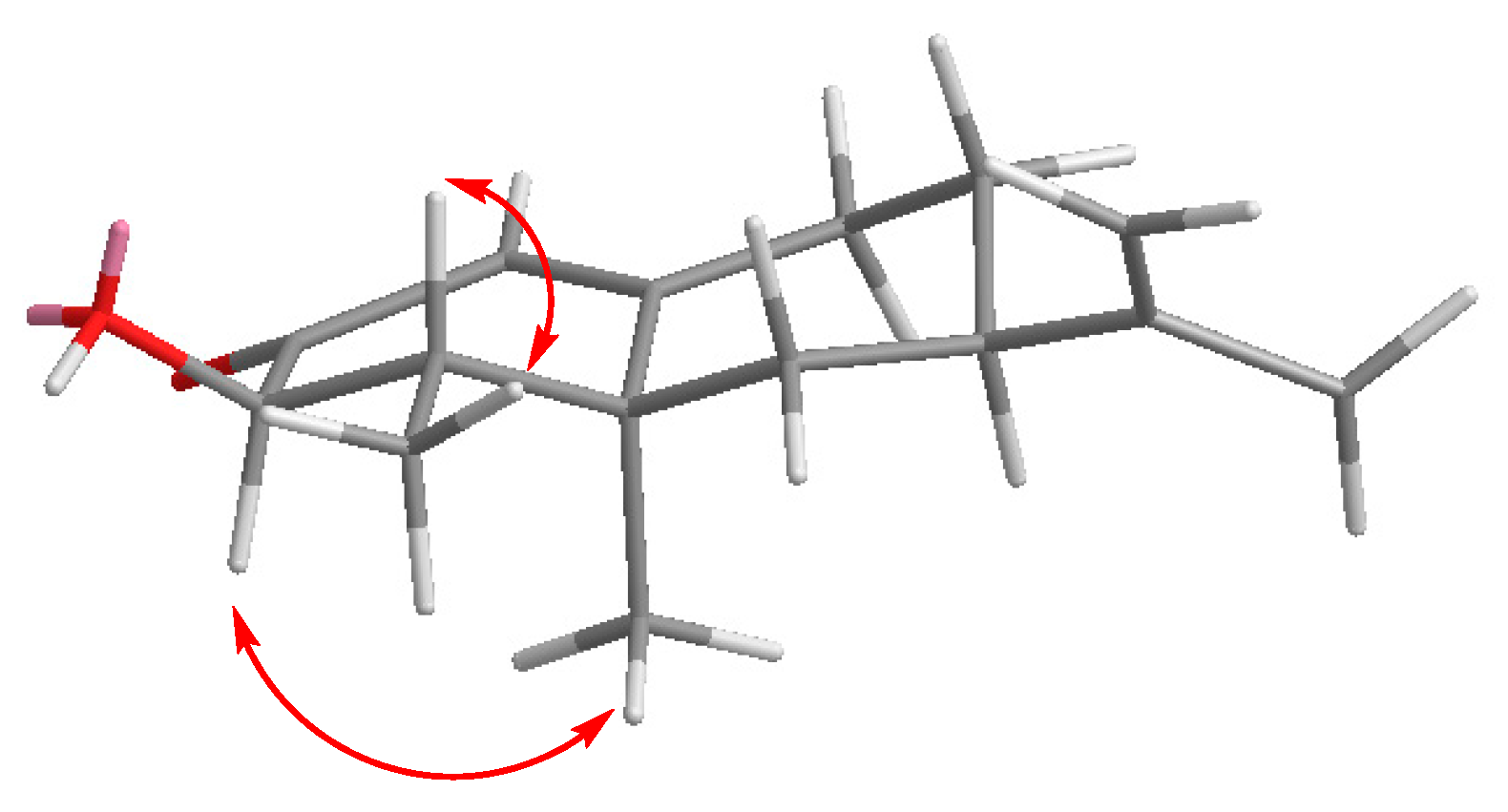

2.2.7. Synthesis of Compounds 14 and 15 (See Scheme 5)

2.2.8. Synthesis of Compounds 16 and 17

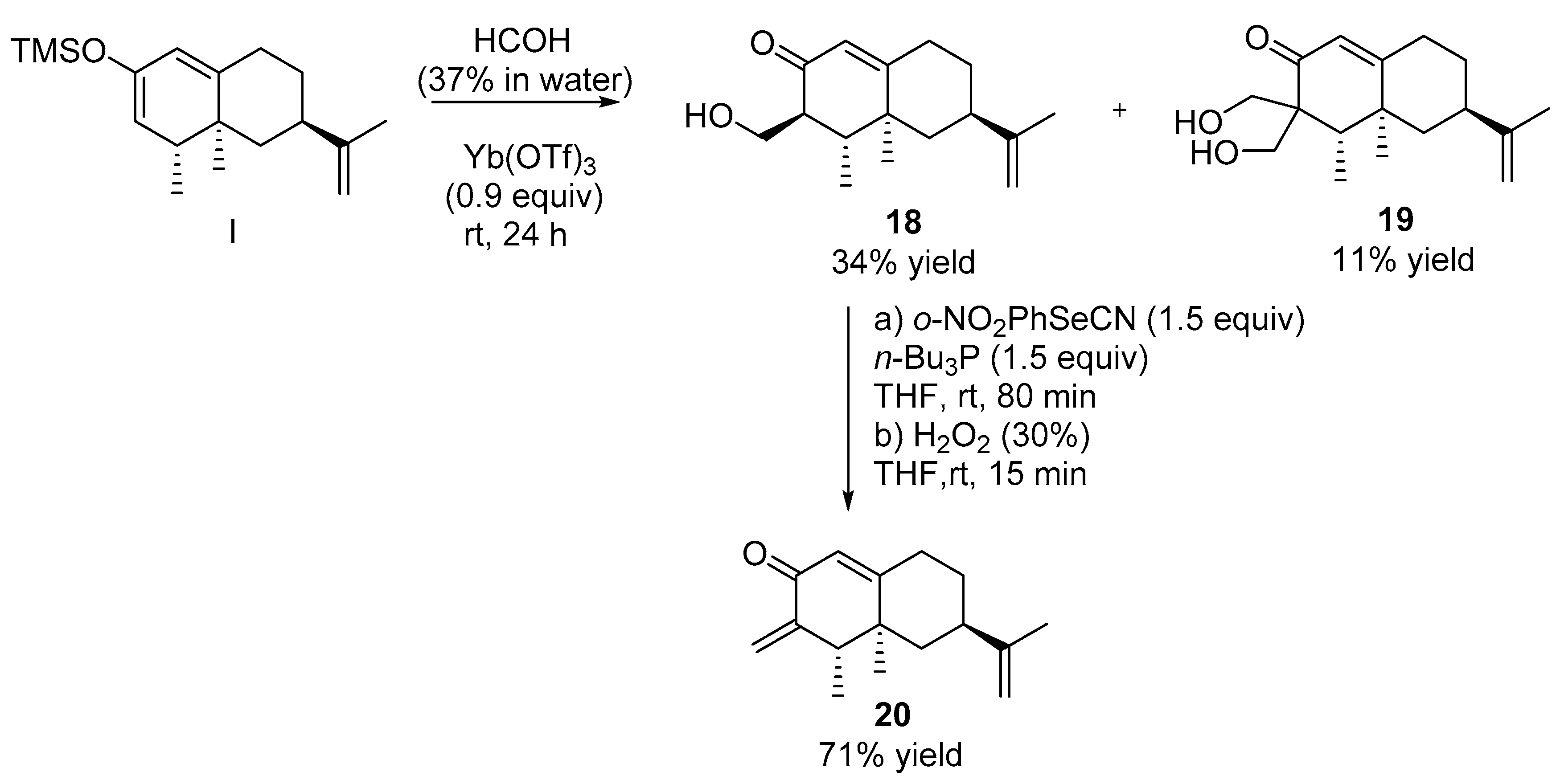

2.2.9. Synthesis of Compounds 18 and 19 (See Scheme 6)

2.2.10. Synthesis of Compound 20

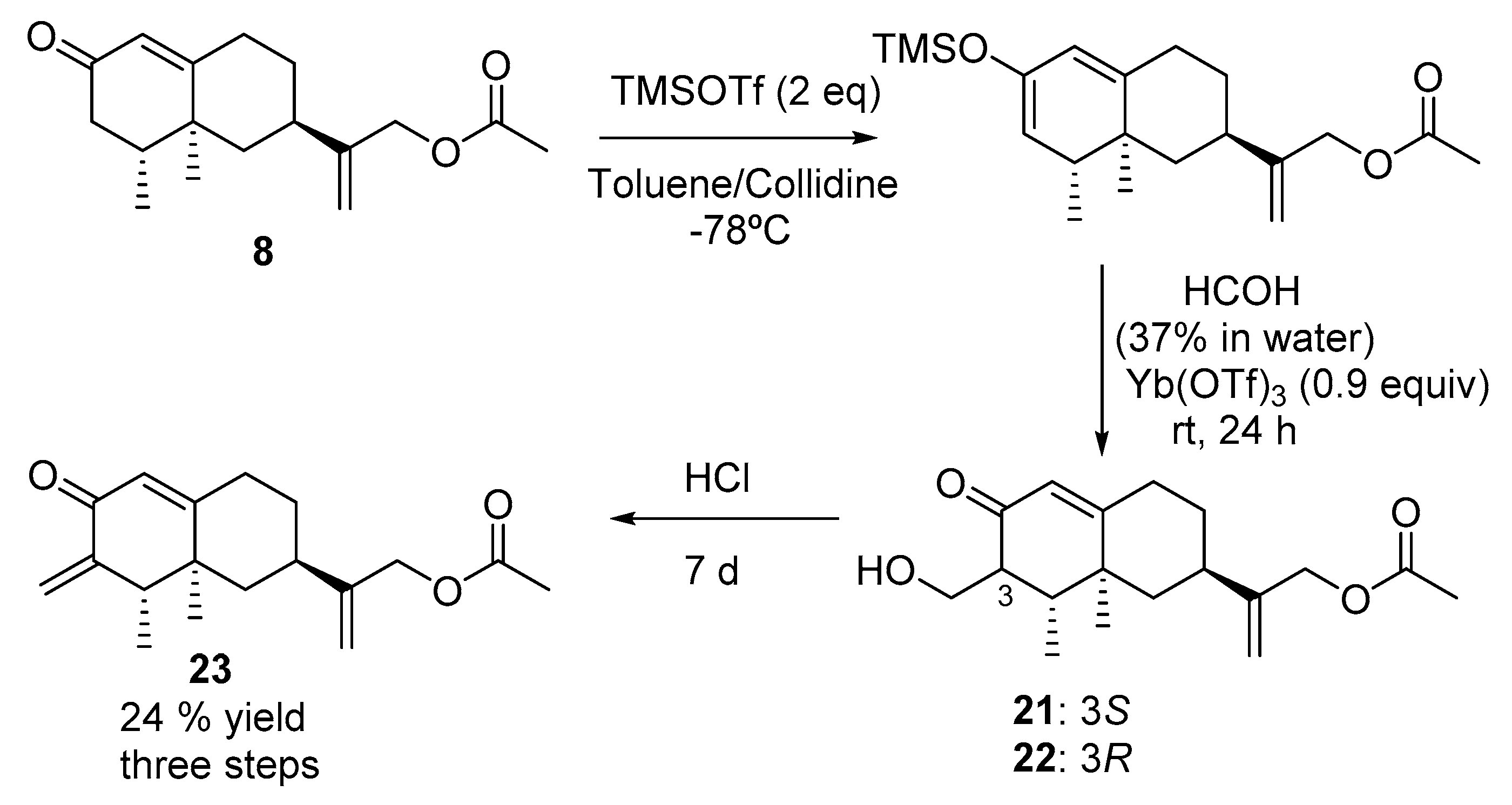

2.2.11. Synthesis of Compounds 21 and 22 (See Scheme 7)

2.2.12. Synthesis of Compound 23 (See Scheme 7)

2.3. Antifeedant Activity

2.4. Ixodicidal Activity

3. Results and Discussion

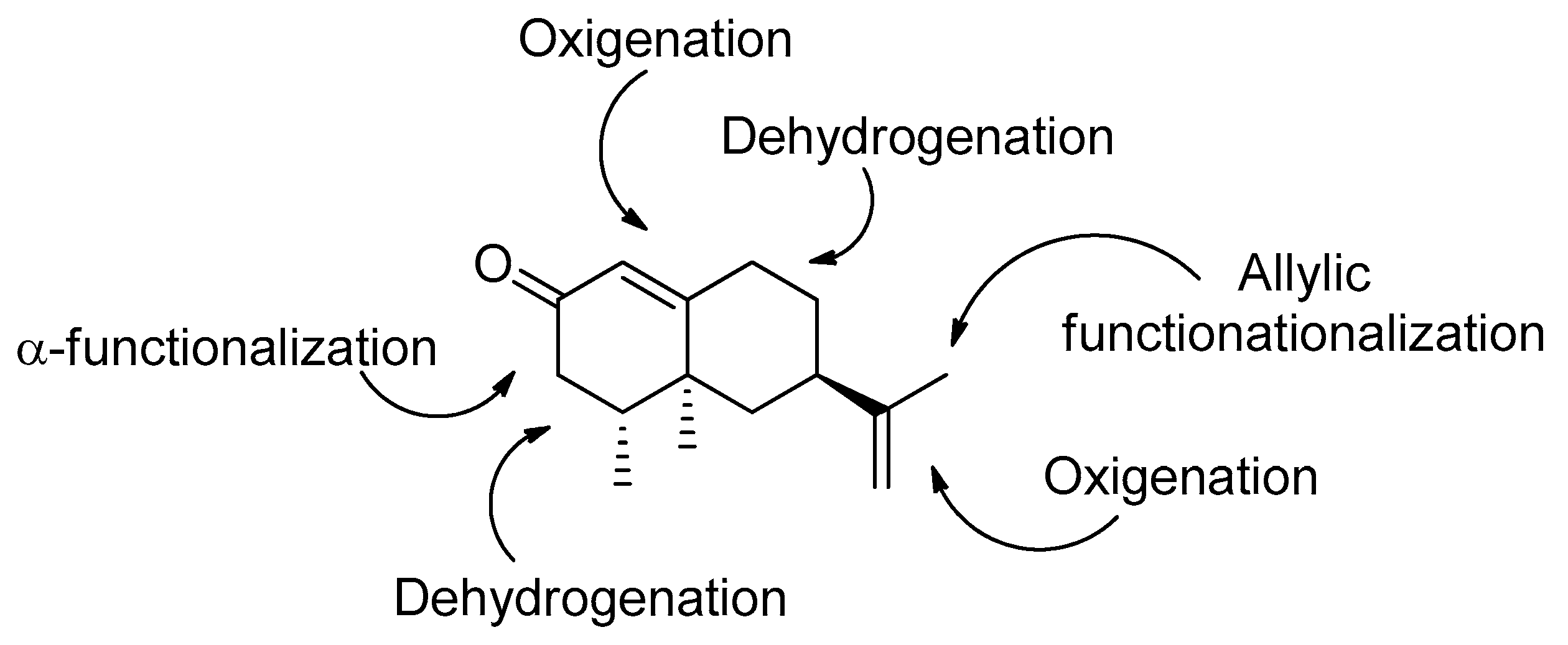

3.1. Synthesis of Nootkatone Derivatives

3.2. Antifeedant Activity

3.3. Ixodicidal Activity

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Marrone, P.G. Pesticidal natural products – status and future potential. Pest Manag. Sci. 2019, 75, 2325–2340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cantrell, C.L.; Dayan, F.E.; Duke, S.O. Natural products as sources for new pesticides. J. Nat. Prod. 2012, 75, 1231–1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erdtman, H.; Hirose, Y. The chemistry of the natural order Cupressales. XLVI. The structure of nootkatone. Acta Chem. Scand. 1962, 16, 1311–1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karchesy, J.J.; Kelsey, R.G.; González-Hernández, M.P. Yellow-Cedar, Callitropsis (Chamaecyparis) nootkatensis, secondary metabolites, biological activities, and chemical ecology. J. Chem. Ecol. 2018, 44, 510–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahrilas, G.A.; Wally, L.M.; Fredrick, S.J.; Hiskey, M.; Prieto, A.L.; Owens, J.E. Microwave-assisted green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using orange peel extract. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2014, 2, 367–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, N.H. Biogenetic implications of the antipodal sesquiterpenes of vetiver oil. Phytochemistry 1970, 9, 145–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zorn, H.; Taupp, D.E.; Huelsdau, B.; Scheibner, M.; Fraatz, M.A.; Berger, R.G. “Bioflavors”—An excursion from the garlic mushroom to raspberry aroma. In Proceedings of the Recent Highlights Flavor Chemistry and Biology, Eisenach, Germany, 27 February–2 March 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Panella, N.A.; Dolan, M.C.; Karchesy, J.J.; Xiong, Y.; Peralta-Cruz, J.; Khasawneh, M.; Montenieri, J.A.; Maupin, G.O. Use of novel compounds for pest control: insecticidal and acaricidal activity of essential oil components from heartwood of Alaska yellow cedar. J. Med. Entomol. 2005, 42, 352–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, B.C.R.; Henderson, G.; Chen, F.; Maistrello, L.; Laine, R.A. Nootkatone is a repellent for formosan subterranean termite (Coptotermes formosanus). J. Chem. Ecol. 2001, 27, 523–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Julien, B.N.; Dolan, M.C.; Bradbury, R.S. Nootkatone compositions and methods for repelling and killing ticks and detachment of feeding ticks. PCT Int. Appl. 2017. WO 2017162886 A1 20170928. [Google Scholar]

- Addesso, K.M.; Oliver, J.B.; O’Neal, P.A.; Youssef, N. Efficacy of nootka oil as a biopesticide for management of imported fire ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). J. Econ. Entomol. 2017, 110, 1547–1555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Vásquez, L.; Olmeda, A.S.; Zúñiga, G.; Villarroel, L.; Echeverri, L.F.; González-Coloma, A.; Reina, M. Insect antifeedant and ixodicidal compounds from Senecio adenotrichius. Chem. Biodivers. 2017, 14, e1600155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Liu, Z.; Bao, C.; Fan, J.; Yang, R. Non-food bioactive products: Design and semisynthesis of novel (+)-nootkatone derivatives containing isoxazoline moiety as insecticide candidates. Ind. Crops Prod. 2019, 140, 111706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handore, K.L.; Kalmode, H.P.; Sayyad, S.; Seetharamsingh, B.; Gathalkar, G.; Padole, S.; Pawar, P.V.; Joseph, M.; Sen, A.; Reddy, D.S. Insect-repellent and mosquitocidal effects of noreremophilane- and nardoaristolone-based compounds. ACS Omega 2019, 4, 2188–2195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradbury, R.S.; Amick, J.D. Nootkatone insecticidal emulsion for repelling, knocking down, or killing pests. PCT Int. Appl. 2018. WO 2018100113 A1 20180607. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, J.A.; Coats, J.R. Acetylcholinesterase inhibition by nootkatone and carvacrol in arthropods. Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 2012, 102, 124–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munoz, L.; Rosell, G.; Quero, C.; Guerrero, A. Biosynthetic pathways of the pheromone of the Egyptian armyworm Spodoptera littoralis. Physiol. Entomol. 2008, 33, 275–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.H.; Jander, G. Myzus persicae (green peach aphid) feeding on Arabidopsis induces the formation of a deterrent indole glucosinolate. Plant J. 2007, 49, 1008–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenslade, A.F.C.; Ward, J.L.; Martin, J.L.; Corol, D.I.; Clark, S.J.; Smart, L.E.; Aradottir, G.I. Triticum monococcum lines with distinct metabolic phenotypes and phloem-based partial resistance to the bird cherry-oat aphid Rhopalosiphum padi. Ann. Appl. Biol. 2016, 168, 435–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ECDC. European Centre for disease prevention and control. Hyalomma marginatum. Available online: https://ecdc.europa.eu/en/disease-vectors/facts/tick-factsheets/hyalomma-marginatum (accessed on 13 October 2019).

- Galloway, W.R.J.D.; Isidro-Llobet, A.; Spring, D.R. Diversity-oriented synthesis as a tool for the discovery of novel biologically active small molecules. Nat. Commun. 2010, 1, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demole, E.; Enggist, P. Further investigation of grapefruit juice flavor components (Citrus paradisi MACFAYDEN). Valencane- and eudesmane-type sesquiterpene ketones. Helv. Chim. Acta 1983, 66, 1381–1391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caine, D.; Chu, C.-Y.; Graham, S.L. Photochemical pathways for the interconversion of nootkatane and spirovetivane sesquiterpenes. J. Org. Chem. 1980, 45, 3790–3797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tateba, H.; Morita, K.; Tada, M. Photochemical reaction of nootkatone under various conditions. J. Chem. Res. Synopses 1992, 140–141. [Google Scholar]

- Furusawa, M.; Hashimoto, T.; Noma, Y.; Asakawa, Y. Biotransformation of citrus aromatics nootkatone and valencene by microorganisms. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2005, 53, 1423–1429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khasawneh, M.A.; Xiong, Y.; Peralta-Cruz, J.; Karchesy, J.J. Biologically important eremophilane sesquiterpenes from Alaska cedar keartwood essential oil and their semi-synthetic Derivatives. Molecules 2011, 16, 4775–4785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santana, O.; Andrés, M.F.; Sanz, J.; Errahmani, N.; Abdeslam, L.; González-Coloma, A. Valorization of essential oils from Moroccan aromatic plants. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2014, 9, 1109–1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domingo, V.; Prieto, C.; Castillo, A.; Silva, L.; Quilez del Moral, J.F.; Barrero, A.F. Iodine-promoted metal-free aromatization: Synthesis of biaryls, oligo p-phenylenes and A-ring modified steroids. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2015, 357, 3359–3364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domingo, V.; Prieto, C.; Silva, L.; Rodilla, J.M.L.; Quilez del Moral, J.F.; Barrero, A.F. Iodine, a mild reagent for the aromatization of terpenoids. J. Nat. Prod. 2016, 79, 831–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, L.; Ding, G.; Guo, B.; Wenhua, W.; Zhang, X.; Sun, Z.; Shi, X. New sesquiterpenoids and a diterpenoid from Alpinia oxyphylla. Molecules 2015, 20, 1551–1559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolev, J.N.; Zaengle, J.M.; Ravikumar, R.; Fasan, R. Enhancing the Efficiency and regioselectivity of P450 oxidation catalysts by unnatural amino acid mutagenesis. ChemBioChem 2014, 15, 1001–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, H.; Bradley, S.A.; Krishnamurthy, K. Extending the limits of the selective 1D NOESY experiment with an improved selective TOCSY edited preparation function. J. Magn. Reson. 2004, 171, 201–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furusawa, M.; Hashimoto, T.; Noma, Y.; Asakawa, Y. Highly efficient production of nootkatone, the grapefruit aroma from valencene, by biotransformation. Chem. Pharm. Bull. (Tokyo). 2005, 53, 1513–1514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rubottom, G.M.; Vazquez, M.A.; Pelegrina, D.R. Peracid oxidation of trimethylsilyl enol ethers: A facile α-hydroxylation procedure. Tetrahedron Lett. 1974, 15, 4319–4322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arseniyadis, S.; Ferreira, M.d.R.R.; Quı́lez del Moral, J.; Martı́n Hernando, J.I.; Potier, P.; Toupet, L. Studies towards the total synthesis of taxoids: a rapid entry into bicyclo[6.4.0]dodecane ring system. Part 1. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry 1998, 9, 4055–4071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grieco, P.A.; Gilman, S.; Nishizawa, M. Organoselenium chemistry. A facile one-step synthesis of alkyl aryl selenides from alcohols. J. Org. Chem. 1976, 41, 1485–1486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan, R.A.; Schulze, T.L.; Dolan, M.C. Efficacy of plant-derived and synthetic compounds on clothing as repellents against Ixodes scapularis and Amblyomma americanum (Acari: Ixodidae). J. Med. Entomol. 2012, 49, 101–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Federal Laboratory Consortium for Technology Transfer (FLC) (2018) Formulation of nootkatone as repellent and pesticide products against mosquitoes and ticks. Available online: https://www.federallabs.org/successes/success-stories/formulation-of-nootkatone-as-repellent-and-pesticide-products-against (accessed on 13 October 2019).

| |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entry | Iodine (equiv) | Time (h) | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 1 | 0.1 | 30 | 14 | 51 | 16 |

| 2 | 0.2 | 6 | 50 | 28 | – |

| 3 | 1 | 2 | 28 | 6 | 25 |

| Product | M. persicae | R. padi | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 50 (µg /cm2) a | EC50 b | 50 (µg /cm2) a | EC50 b | |

| 1 | 50.7 ± 9.1 | ~50 | 57.7 ± 10.2 | ~50 |

| 2 | 35.4 ± 9.0 | >50 | 86.0 ± 3.6 * | 17.4 (14.4–20.9) |

| 3 | 24.6 ± 7.5 | >50 | 77.1 ± 4.5 * | 27.1 (20.7–35.4) |

| 5 | 49.4 ± 10.9 | ~50 | 40.9 ± 8.2 | >50 |

| 6 | 57.2 ± 10.1 | ~50 | 30.7 ± 6.8 | >50 |

| 7 | 79.9 ± 5.4 * | ~25 | 30.8 ± 6.5 | >50 |

| 8 | 37.8 ± 9.8 | >50 | 31.4 ± 5.9 | >50 |

| 9 | 34.2 ± 8.5 | >50 | 44.2 ± 9.2 | >50 |

| 10 | 80.6 ± 4.8 * | 23.5 (16.6–33.3) | 36.95 ± 8.5 | >50 |

| 11 | 49.0 ± 9.4 | ~50 | 69.4 ± 7.6 * | ~25 |

| 12 | 59.1 ± 7.0 | ~50 | 51.8 ± 5.7 | ~50 |

| 13 | 29.0 ± 4.5 | >50 | 19.85 ± 6.5 | >50 |

| 14 | 91.2 ± 5.3 * | 30–40 | 83.8 ± 4.9 * | 30–40>50 |

| 15 | 54.5 ± 8.0 | ~50 | 78.81 ± 4.4 | 8.3 (5.5–12.7) |

| 16 | 63.9 ± 7.4 * | ~50 | 37.3 ± 7.3 | >50 |

| 17 | 40.6 ± 6.9 | >50 | 34.2 ± 7.9 | >50 |

| 18 | 60.4 ± 7.1 * | ~50 | 44.4 ± 9.0 | >50 |

| 19 | 35.4 ± 7.6 | >50 | 19.8 ± 5.6 | >50 |

| 20 | 92.1± 2.5 ** | 16.3 (13.6–19.7) | 93.9 ± 4.2 * | 7.1 (5.4–9.4) |

| 23 | 62.3 ± 9.2 | ~50 | 17.5 ± 6.7 | >50 |

| Product | % Mortality a (20 μg/mg) | Lethal Dose (μg/mg) b | |

|---|---|---|---|

| LD50 | LD90 | ||

| 1 | 85.9 ± 2.2 | 4.02 (1.92–7.42) | 18.02 (13.60–29.16) |

| 2 | 100 ± 0 | 5.36 (4.94–5.90) | 4.31(3.93–4.82) |

| 3 | 98.3 ± 0.4 | 2.94 (2.54–3.38) | 5.72 (5.0–6.80) |

| 5 | 100 ± 0 | 0.96 (0.88–1.04) | 1.28 (1.18–1.38) |

| 6 | 47.3 ± 14.3 | ||

| 7 | 100 ± 0 | 5.04 (4.56–5.64) | 8.04 (7.20–9.22) |

| 8 | 32.2 ± 3.0 | ||

| 9 | 42.6 ± 2.2 | ||

| 10 | 8.5 ± 1.0 | ||

| 11 | 88.5 ± 1.6 | 5.60 (4.88–6.44) | 10.84 (9.50–12.8) |

| 12 | 1.5 ± 1.6 | ||

| 13 | 7.7 ± 10.8 | ||

| 14 | 46.3 ± 8.7 | ||

| 15 | 100 ± 0 | 8.74 (8.10–9.40) | 11.52 (10.68–12.8) |

| 16 | 23.4 ± 3.5 | ||

| 17 | 11.7 ± 7.3 | ||

| 18 | 96.7 ± 1.6 | 7.06 (6.20–8.10) | 12.94 (11.34–15.36) |

| 19 | 17.7 ± 1.3 | ||

| 20 | 100 ± 0 | 1.34 (1.20–1.50) | 2.14 (1.92–2.44) |

| 23 | 11.5 ± 1.3 | ||

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Galisteo Pretel, A.; Pérez del Pulgar, H.; Olmeda, A.S.; Gonzalez-Coloma, A.; Barrero, A.F.; Quílez del Moral, J.F. Novel Insect Antifeedant and Ixodicidal Nootkatone Derivatives. Biomolecules 2019, 9, 742. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom9110742

Galisteo Pretel A, Pérez del Pulgar H, Olmeda AS, Gonzalez-Coloma A, Barrero AF, Quílez del Moral JF. Novel Insect Antifeedant and Ixodicidal Nootkatone Derivatives. Biomolecules. 2019; 9(11):742. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom9110742

Chicago/Turabian StyleGalisteo Pretel, Alberto, Helena Pérez del Pulgar, A. Sonia Olmeda, Azucena Gonzalez-Coloma, Alejandro F. Barrero, and José Francisco Quílez del Moral. 2019. "Novel Insect Antifeedant and Ixodicidal Nootkatone Derivatives" Biomolecules 9, no. 11: 742. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom9110742

APA StyleGalisteo Pretel, A., Pérez del Pulgar, H., Olmeda, A. S., Gonzalez-Coloma, A., Barrero, A. F., & Quílez del Moral, J. F. (2019). Novel Insect Antifeedant and Ixodicidal Nootkatone Derivatives. Biomolecules, 9(11), 742. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom9110742