Wheat Class I TCP Transcription Factor TaTCP15 Positively Regulates Cutin and Cuticular Wax Biosynthesis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Materials and Growth Conditions

2.2. Accession Numbers

2.3. Gene Silencing Assay

2.4. Gene Expression Analysis

2.5. Transcriptional Activation Analysis

2.6. Cuticular Lipid Composition Analysis

2.7. Wheat Leaf Cuticle Permeability Analysis

2.8. Analyses of Protein Enrichment at Gene Promoter Regions

2.9. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

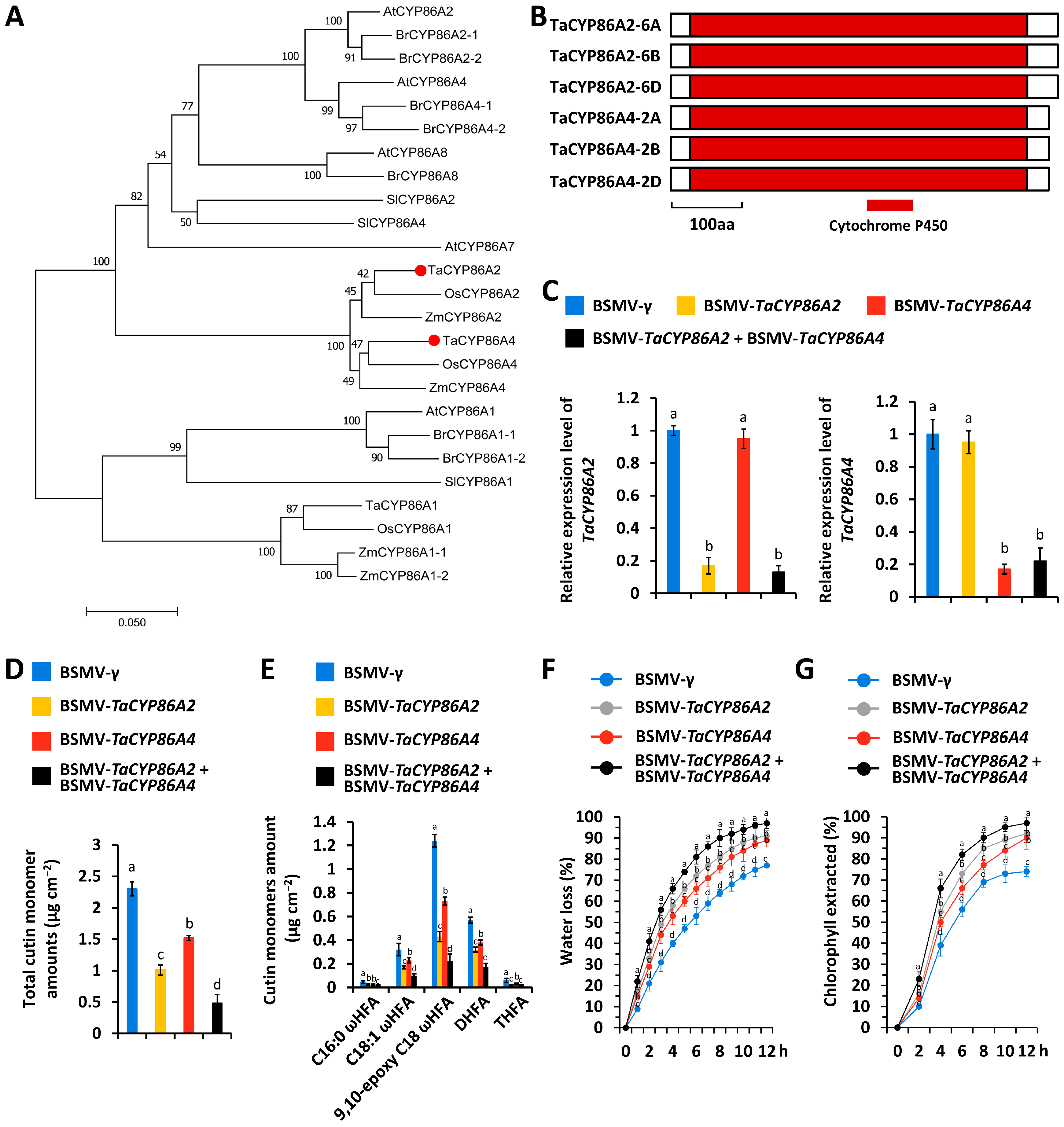

3.1. Characterization of TaCYP86A2 and TaCYP86A4 Genes Essential for Wheat Cutin Biosynthesis

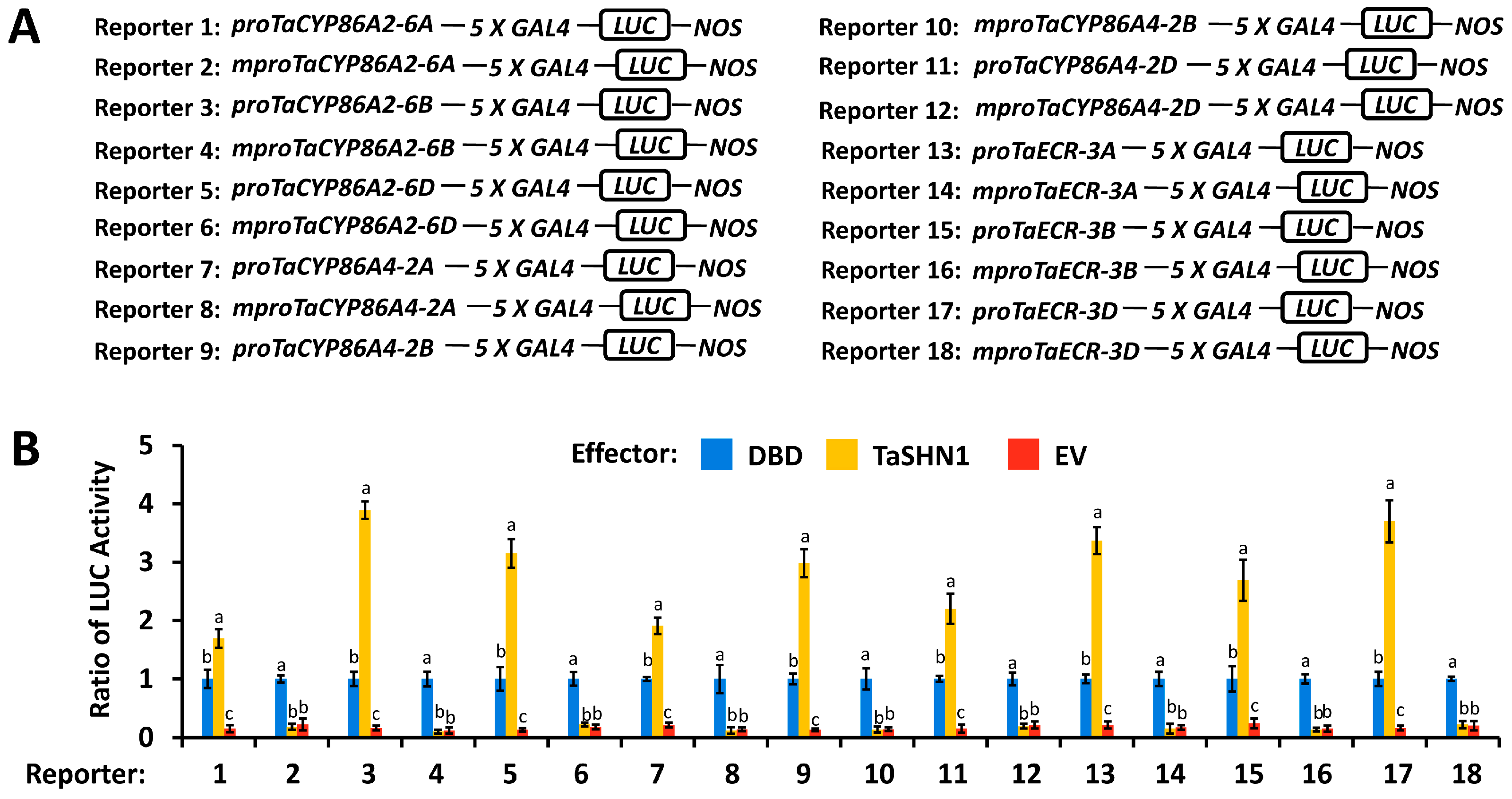

3.2. Transcriptional Regulation of Cutin Biosynthesis Genes TaCYP86A2 and TaCYP86A4 and Wax Biosynthesis Gene TaECR by Transcription Factor TaSHN1 and Mediator Subunit TaCDK8

3.3. Identification of Transcription Factor TaTCP15 as a Transcriptional Regulator of the TaSHN1 Gene

3.4. Functional Characterization of the TaTCP15 Gene in Cutin and Wax Biosynthesis

4. Discussion

4.1. CYP86A Family Cytochrome P450 Enzyme TaCYP86A2 and TaCYP86A4 Proteins Show Partially Redundant Contributions to Wheat Cutin Biosynthesis

4.2. Wheat Transcription Factor TaSHN1 and Its Interactor Mediator Subunit TaCDK8 Directly Regulate Transcription of Cutin Biosynthesis Genes TaCYP86A2 and TaCYP86A4

4.3. Wheat TCP-Type Transcription Factor TaTCP15 Transactivates the TaSHN1 Gene and Stimulates Cutin and Wax Biosynthesis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Li, H.; Chang, C. Evolutionary insight of plant cuticle biosynthesis in bryophytes. Plant Signal. Behav. 2021, 16, 1943921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berhin, A.; de Bellis, D.; Franke, R.B.; Buono, R.A.; Nowack, M.K.; Nawrath, C. The root cap cuticle: A cell wall structure for seedling establishment and lateral root formation. Cell 2019, 176, 1367–1378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Domínguez, E.; Heredia-Guerrero, J.A.; Heredia, A. The plant cuticle: Old challenges, new perspectives. J. Exp. Bot. 2017, 68, 5251–5255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lewandowska, M.; Keyl, A.; Feussner, I. Wax biosynthesis in response to danger: Its regulation upon abiotic and biotic stress. New Phytol. 2020, 227, 698–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, L.; Wang, X.; Chang, C. Toward a smart skin: Harnessing cuticle biosynthesis for crop adaptation to drought, salinity, temperature, and ultraviolet stress. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 961829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández, V.; Guzmán-Delgado, P.; Graça, J.; Santos, S.; Gil, L. Cuticle structure in relation to chemical composition: Re-assessing the prevailing model. Front. Plant Sci. 2016, 7, 427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingram, G.; Nawrath, C. The roles of the cuticle in plant development: Organ adhesions and beyond. J. Exp. Bot. 2017, 68, 5307–5321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeats, T.H.; Rose, J.K. The formation and function of plant cuticles. Plant Physiol. 2013, 163, 5–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.B.; Suh, M.C. Advances in the understanding of cuticular waxes in Arabidopsis thaliana and crop species. Plant Cell Rep. 2015, 34, 557–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.B.; Suh, M.C. Regulatory mechanisms underlying cuticular wax biosynthesis. J. Exp. Bot. 2022, 73, 2799–2816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samuels, L.; Kunst, L.; Jetter, R. Sealing plant surfaces: Cuticular wax formation by epidermal cells. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2008, 59, 683–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonaventure, B.; Salas, J.J.; Pollard, M.R.; Ohlrogge, J.B. Disruption of the FATB gene in Arabidopsis demonstrates an essential role of saturated fatty acids in plant growth. Plant Cell 2003, 15, 1020–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnurr, J.; Shockey, J.; Browse, J. The acyl-CoA synthetase encoded by LACS2 is essential for normal cuticle development in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 2004, 16, 629–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lü, S.; Song, T.; Kosma, D.K.; Parsons, E.P.; Rowland, O.; Jenks, M.A. Arabidopsis CER8 encodes LONG-CHAIN ACYL-COA SYNTHETASE 1 (LACS1) that has overlapping functions with LACS2 in plant wax and cutin synthesis. Plant J. 2009, 59, 553–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, H.; Molina, I.; Shockey, J.; Browse, J. Organ fusion and defective cuticle function in a lacs1 lacs2 double mutant of Arabidopsis. Planta 2010, 231, 1089–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurdyukov, S.; Faust, A.; Trenkamp, S.; Bär, S.; Franke, R.; Efremova, N.; Tietjen, K.; Schreiber, L.; Saedler, H.; Yephremov, A. Genetic and biochemical evidence for involvement of HOTHEAD in the biosynthesis of long-chain alpha-,omega-dicarboxylic fatty acids and formation of extracellular matrix. Planta 2006, 224, 315–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sauveplane, V.; Kandel, S.; Kastner, P.E.; Ehlting, J.; Compagnon, V.; Werck-Reichhart, D.; Pinot, F. Arabidopsis thaliana CYP77A4 is the first cytochrome P450 able to catalyze the epoxidation of free fatty acids in plants. FEBS J. 2009, 276, 719–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, W.; Simpson, J.P.; Li-Beisson, Y.; Beisson, F.; Pollard, M.; Ohlrogge, J.B. A land-plant-specific glycerol-3-phosphate acyltransferase family in Arabidopsis: Substrate specificity, sn-2 preference, and evolution. Plant Physiol. 2012, 160, 638–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, F.; Goodwin, S.M.; Xiao, Y.; Sun, Z.; Baker, D.; Tang, X.; Jenks, M.A.; Zhou, J.M. Arabidopsis CYP86A2 represses Pseudomonas syringae type III genes and is required for cuticle development. EMBO J. 2004, 23, 2903–2913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millar, A.A.; Clemens, S.; Zachgo, S.; Giblin, E.M.; Taylor, D.C.; Kunst, L. CUT1, an Arabidopsis gene required for cuticular wax biosynthesis and pollen fertility, encodes a very-long-chain fatty acid condensing enzyme. Plant Cell 1999, 11, 825–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todd, J.; Post-Beittenmiller, D.; Jaworski, J.G. KCS1 encodes a fatty acid elongase 3-ketoacyl-CoA synthase affecting wax biosynthesis in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 1999, 17, 119–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiebig, A.; Mayfield, J.A.; Miley, N.L.; Chau, S.; Fischer, R.L.; Preuss, D. Alterations in CER6, a gene identical to CUT1, differentially affect long-chain lipid content on the surface of pollen and stems. Plant Cell 2000, 12, 2001–2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hooker, T.S.; Millar, A.A.; Kunst, L. Significance of the expression of the CER6 condensing enzyme for cuticular wax production in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2002, 129, 1568–1580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, H.; Rowland, O.; Kunst, L. Disruptions of the Arabidopsis Enoyl-CoA reductase gene reveal an essential role for very-long-chain fatty acid synthesis in cell expansion during plant morphogenesis. Plant Cell 2005, 17, 1467–1481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bach, L.; Michaelson, L.V.; Haslam, R.; Bellec, Y.; Gissot, L.; Marion, J.; Da Costa, M.; Boutin, J.P.; Miquel, M.; Tellier, F.; et al. The very-long-chain hydroxy fatty acyl-CoA dehydratase PASTICCINO2 is essential and limiting for plant development. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 14727–14731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaudoin, F.; Wu, X.; Li, F.; Haslam, R.P.; Markham, J.E.; Zheng, H.; Napier, J.A.; Kunst, L. Functional characterization of the Arabidopsis beta-ketoacyl-coenzyme A reductase candidates of the fatty acid elongase. Plant Physiol. 2009, 150, 1174–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.B.; Jung, S.J.; Go, Y.S.; Kim, H.U.; Kim, J.K.; Cho, H.J.; Park, O.K.; Suh, M.C. Two Arabidopsis 3-ketoacyl CoA synthase genes, KCS20 and KCS2/DAISY, are functionally redundant in cuticular wax and root suberin biosynthesis, but differentially controlled by osmotic stress. Plant J. 2009, 60, 462–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.; Jung, J.H.; Lee, S.B.; Go, Y.S.; Kim, H.J.; Cahoon, R.; Markham, J.E.; Cahoon, E.B.; Suh, M.C. Arabidopsis 3-ketoacyl-coenzyme a synthase9 is involved in the synthesis of tetracosanoic acids as precursors of cuticular waxes, suberins, sphingolipids, and phospholipids. Plant Physiol. 2013, 162, 567–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aarts, M.G.; Keijzer, C.J.; Stiekema, W.J.; Pereira, A. Molecular characterization of the CER1 gene of Arabidopsis involved in epicuticular wax biosynthesis and pollen fertility. Plant Cell 1995, 7, 2115–2127. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X.; Goodwin, S.M.; Boroff, V.L.; Liu, X.; Jenks, M.A. Cloning and characterization of the WAX2 gene of Arabidopsis involved in cuticle membrane and wax production. Plant Cell 2003, 15, 1170–1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowland, O.; Lee, R.; Franke, R.; Schreiber, L.; Kunst, L. The CER3 wax biosynthetic gene from Arabidopsis thaliana is allelic to WAX2/YRE/FLP1. FEBS Lett. 2007, 581, 3538–3544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rowland, O.; Zheng, H.; Hepworth, S.R.; Lam, P.; Jetter, R.; Kunst, L. CER4 encodes an alcohol-forming fatty acyl-coenzyme A reductase involved in cuticular wax production in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2006, 142, 866–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greer, S.; Wen, M.; Bird, D.; Wu, X.; Samuels, L.; Kunst, L.; Jetter, R. The cytochrome P450 enzyme CYP96A15 is the midchain alkane hydroxylase responsible for formation of secondary alcohols and ketones in stem cuticular wax of Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2007, 145, 653–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bourdenx, B.; Bernard, A.; Domergue, F.; Pascal, S.; Léger, A.; Roby, D.; Pervent, M.; Vile, D.; Haslam, R.P.; Napier, J.A.; et al. Overexpression of Arabidopsis ECERIFERUM1 promotes wax very-long-chain alkane biosynthesis and influences plant response to biotic and abiotic stresses. Plant Physiol. 2011, 156, 29–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernard, A.; Domergue, F.; Pascal, S.; Jetter, R.; Renne, C.; Faure, J.D.; Haslam, R.P.; Napier, J.A.; Lessire, R.; Joubès, J. Reconstitution of plant alkane biosynthesis in yeast demonstrates that Arabidopsis ECERIFERUM1 and ECERIFERUM3 are core components of a very-long-chain alkane synthesis complex. Plant Cell 2012, 24, 3106–3118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascal, S.; Bernard, A.; Deslous, P.; Gronnier, J.; Fournier-Goss, A.; Domergue, F.; Rowland, O.; Joubès, J. Arabidopsis CER1-LIKE1 functions in a cuticular very-long-chain alkane-forming complex. Plant Physiol. 2019, 179, 415–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, X.; Zhao, H.; Kosma, D.K.; Tomasi, P.; Dyer, J.M.; Li, R.; Liu, X.; Wang, Z.; Parsons, E.P.; Jenks, M.A.; et al. The acyl desaturase CER17 is involved in producing wax unsaturated primary alcohols and cutin monomers. Plant Physiol. 2017, 173, 1109–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bird, D.; Beisson, F.; Brigham, A.; Shin, J.; Greer, S.; Jetter, R.; Kunst, L.; Wu, X.; Yephremov, A.; Samuels, L. Characterization of Arabidopsis ABCG11/WBC11, an ATP binding cassette (ABC) transporter that is required for cuticular lipid secretion. Plant J. 2007, 52, 485–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bessire, M.; Borel, S.; Fabre, G.; Carraça, L.; Efremova, N.; Yephremov, A.; Cao, Y.; Jetter, R.; Jacquat, A.C.; Métraux, J.P.; et al. A member of the PLEIOTROPIC DRUG RESISTANCE family of ATP binding cassette transporters is required for the formation of a functional cuticle in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 2011, 23, 1958–1970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Lee, S.B.; Kim, H.J.; Min, M.K.; Hwang, I.; Suh, M.C. Characterization of glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchored lipid transfer protein 2 (LTPG2) and overlapping function between LTPG/LTPG1 and LTPG2 in cuticular wax export or accumulation in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell Physiol. 2012, 53, 1391–1403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panikashvili, D.; Savaldi-Goldstein, S.; Mandel, T.; Yifhar, T.; Franke, R.B.; Höfer, R.; Schreiber, L.; Chory, J.; Aharoni, A. The Arabidopsis DESPERADO/AtWBC11 transporter is required for cutin and wax secretion. Plant Physiol. 2007, 145, 1345–1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panikashvili, D.; Shi, J.X.; Schreiber, L.; Aharoni, A. The Arabidopsis ABCG13 transporter is required for flower cuticle secretion and patterning of the petal epidermis. New Phytol. 2011, 190, 113–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McFarlane, H.E.; Shin, J.J.; Bird, D.A.; Samuels, A.L. Arabidopsis ABCG transporters, which are required for export of diverse cuticular lipids, dimerize in different combinations. Plant Cell 2010, 22, 3066–3075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McFarlane, H.E.; Watanabe, Y.; Yang, W.; Huang, Y.; Ohlrogge, J.; Samuels, A.L. Golgi- and trans-Golgi network-mediated vesicle trafficking is required for wax secretion from epidermal cells. Plant Physiol. 2014, 164, 1250–1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pighin, J.A.; Zheng, H.; Balakshin, L.J.; Goodman, I.P.; Western, T.L.; Jetter, R.; Kunst, L.; Samuels, A.L. Plant cuticular lipid export requires an ABC transporter. Science 2004, 306, 702–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buda, G.J.; Barnes, W.J.; Fich, E.A.; Park, S.; Yeats, T.H.; Zhao, L.; Domozych, D.S.; Rose, J.K. An ATP binding cassette transporter is required for cuticular wax deposition and desiccation tolerance in the moss Physcomitrella patens. Plant Cell 2013, 25, 4000–4013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samain, E.; van Tuinen, D.; Jeandet, P.; Aussenac, T.; Selim, S. Biological control of Septoria leaf blotch and growth promotion in wheat by Paenibacillus sp. Strain B2 and Curtobacterium plantarum Strain EDS. Biol. Control 2017, 114, 87–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, L.; Chang, C. Suppression of wheat TaCDK8/TaWIN1 interaction negatively affects germination of Blumeria graminis f.sp. tritici by interfering with very-long-chain aldehyde biosynthesis. Plant Mol. Biol. 2018, 96, 165–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhi, P.; Chen, W.; Zhang, W.; Ge, P.; Chang, C. Wheat topoisomerase VI positively regulates the biosynthesis of cuticular wax and cutin. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2024, 72, 25560–25573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Fu, Y.; Zhi, P.; Liu, X.; Ge, P.; Zhang, W.; Chen, W.; Chang, C. The SAGA histone acetyltransferase complex functions in concert with RNA processing machinery to regulate wheat wax biosynthesis. Plant Physiol. 2025, 198, kiaf153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, C.; Li, C.; Yan, L.; Jackson, A.O.; Liu, Z.; Han, C.; Yu, J.; Li, D. A high throughput barley stripe mosaic virus vector for virus induced gene silencing in monocots and dicots. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e26468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potter, C.J.; Tasic, B.; Russler, E.V.; Liang, L.; Luo, L. The Q system: A repressible binary system for transgene expression, lineage tracing, and mosaic analysis. Cell 2010, 141, 536–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansjakob, A.; Riederer, M.; Hildebrandt, U. Wax matters: Absence of very-long-chain aldehydes from the leaf cuticular wax of the glossy11 mutant of maize compromises the prepenetration processes of Blumeria graminis. Plant Pathol. 2011, 60, 1151–1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lolle, S.J.; Berlyn, G.P.; Engstrom, E.M.; Krolikowski, K.A.; Reiter, W.D.; Pruitt, R.E. Developmental regulation of cell interactions in the Arabidopsis fiddlehead-1 mutant: A role for the epidermal cell wall and cuticle. Dev. Biol. 1997, 189, 311–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kosma, D.K.; Bourdenx, B.; Bernard, A.; Parsons, E.P.; Lü, S.; Joubès, J.; Jenks, M.A. The impact of water deficiency on leaf cuticle lipids of Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2009, 151, 1918–1929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Camoirano, A.; Arce, A.L.; Ariel, F.D.; Alem, A.L.; Gonzalez, D.H.; Viola, I.L. Class I TCP transcription factors regulate trichome branching and cuticle development in Arabidopsis. J. Exp. Bot. 2020, 71, 5438–5453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Fang, L.; Wang, X.; Li, H.; Liu, J.; Zhi, P.; Chang, C. Wheat Class I TCP Transcription Factor TaTCP15 Positively Regulates Cutin and Cuticular Wax Biosynthesis. Biomolecules 2026, 16, 192. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom16020192

Fang L, Wang X, Li H, Liu J, Zhi P, Chang C. Wheat Class I TCP Transcription Factor TaTCP15 Positively Regulates Cutin and Cuticular Wax Biosynthesis. Biomolecules. 2026; 16(2):192. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom16020192

Chicago/Turabian StyleFang, Linzhu, Xiaoyu Wang, Haoyu Li, Jiao Liu, Pengfei Zhi, and Cheng Chang. 2026. "Wheat Class I TCP Transcription Factor TaTCP15 Positively Regulates Cutin and Cuticular Wax Biosynthesis" Biomolecules 16, no. 2: 192. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom16020192

APA StyleFang, L., Wang, X., Li, H., Liu, J., Zhi, P., & Chang, C. (2026). Wheat Class I TCP Transcription Factor TaTCP15 Positively Regulates Cutin and Cuticular Wax Biosynthesis. Biomolecules, 16(2), 192. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom16020192