Natural Product Driven Activation of UCP1 and Tumor Metabolic Suppression: Integrating Thermogenic Nutrient Competition with Cancer Metabolic Reprogramming

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. UCP1 Biology and Thermogenic Mechanisms

3. Signaling Pathways Regulating UCP1 Expression

3.1. β3-Adrenergic Signaling Pathway

3.2. AMPK-SIRT1-PGC1α Metabolic Signaling Pathway

3.3. PRDM16 -PGC1α-EBF2 Transcriptional Pathway

3.4. Endocrine and Paracrine Thermogenic Pathways (BMP7, Irisin, METRNL)

4. Natural Products That Upregulate UCP1 Expression and Thermogenic Programming

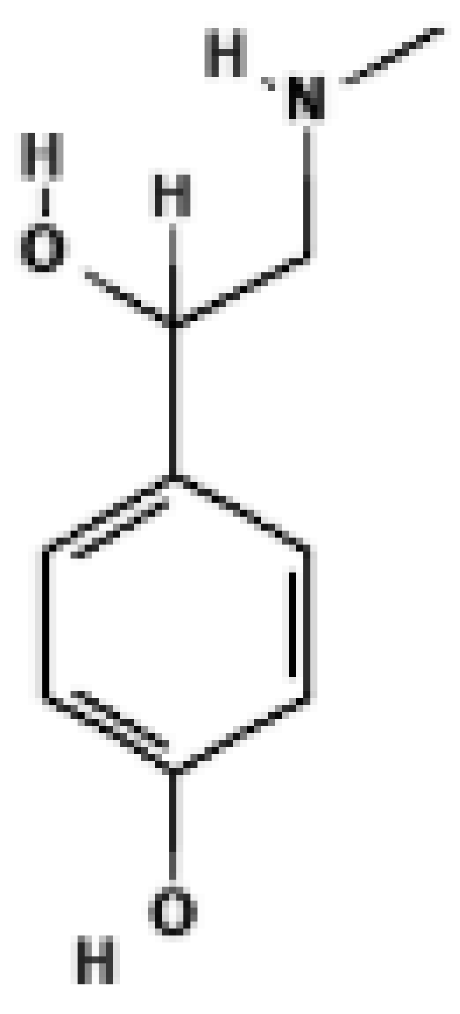

4.1. Natural Products That Mimic β3-Adrenergic Receptor Activation

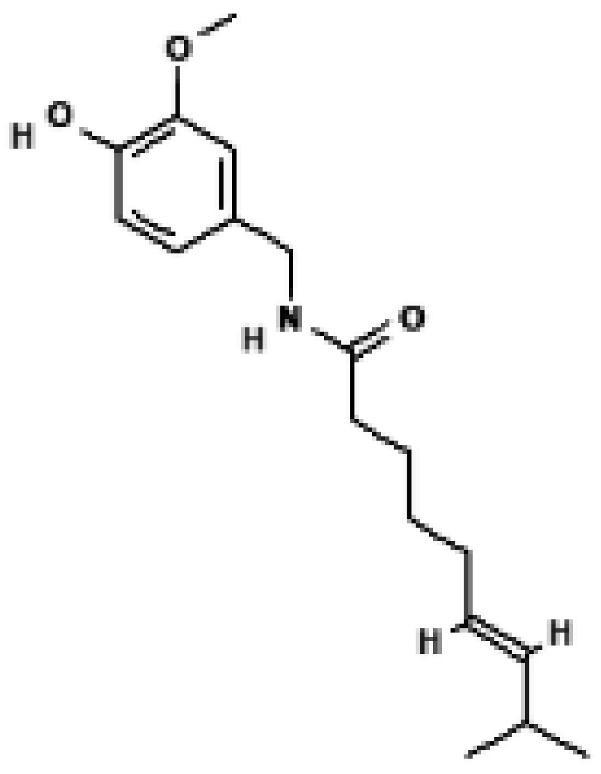

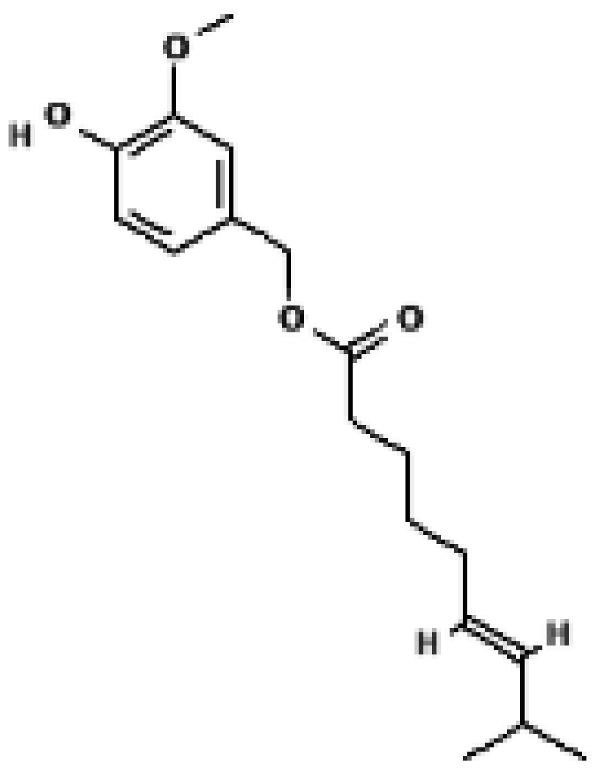

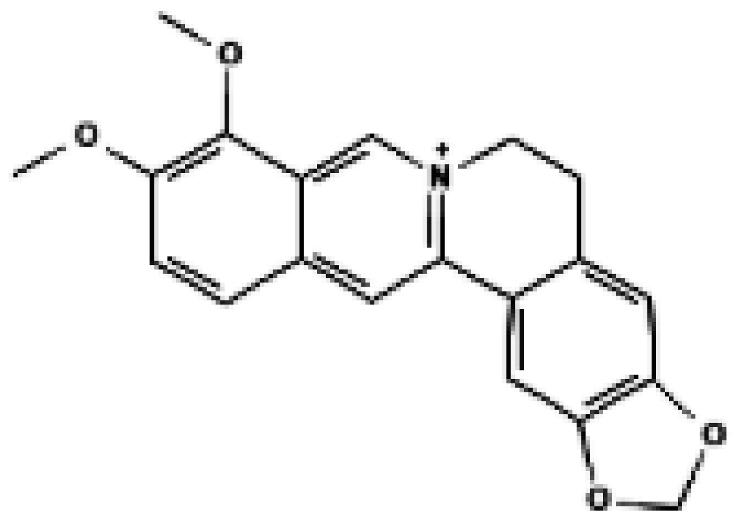

4.2. AMPK Activating Natural Products

4.3. Natural Products That Enhance PRDM16 Centered Transcriptional Programs

4.4. Natural Products That Enhance BMP7–SMAD Pathway or the FNDC5–Irisin Pathway

4.5. Natural Products That Enhance Mitochondrial Biogenesis and Thermogenic Remodeling

5. Structural Basis of UCP1 Regulation

6. Natural Products as Putative Direct Activators of UCP1

7. Cancer Metabolic Reprogramming and Natural Products Targeting Each Pathway

7.1. Enhanced Glucose Uptake and Aerobic Glycolysis

7.2. Pyruvate Utilization and TCA Cycle Flexibility

7.3. Lipid Biosynthesis Driven by Citrate Export

7.4. Increased Nucleotide Biosynthesis

7.5. Glutamine Addiction and Anaplerosis

7.6. ATP Production: Oxidative and Non-Oxidative Contributions

8. Research Gaps and Future Directions

8.1. Existing Evidence Linking Natural Products, Adipose Biology, and Tumor Regulation

8.2. Critical Mechanistic Gap in Natural-Product-Driven Thermogenic Competition

8.3. Proposed Experimental Strategies to Bridge the Gap

9. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hanahan, D.; Weinberg, R.A. Hallmarks of cancer: The next generation. Cell 2011, 144, 646–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, B.S.; Hsu, C.C.; Wu, H.E.; Chen, Y.R.; Zhou, X.; Wang, S.C.; Li, C.Y.; Lin, H.K. Glucose metabolism and its direct action in cancer and immune regulation: Opportunities and challenges for metabolic targeting. J. Biomed. Sci. 2025, 32, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chouchani, E.T.; Kazak, L.; Spiegelman, B.M. New Advances in Adaptive Thermogenesis: UCP1 and Beyond. Cell Metab. 2019, 29, 27–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragni, M.; Ruocco, C.; Nisoli, E. Mitochondrial uncoupling, energy substrate utilization, and brown adipose tissue as therapeutic targets in cancer. NPJ Metab. Health Dis. 2025, 3, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cannon, B.; Nedergaard, J. Brown adipose tissue: Function and physiological significance. Physiol. Rev. 2004, 84, 277–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harms, M.; Seale, P. Brown and beige fat: Development, function and therapeutic potential. Nat. Med. 2013, 19, 1252–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowell, B.B.; Spiegelman, B.M. Towards a molecular understanding of adaptive thermogenesis. Nature 2000, 404, 652–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H.P.; An, K.; Ito, Y.; Kharbikar, B.N.; Sheng, R.; Paredes, B.; Murray, E.; Pham, K.; Bruck, M.; Zhou, X.; et al. Implantation of engineered adipocytes suppresses tumor progression in cancer models. Nat. Biotechnol. 2025, 43, 1979–1995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seki, T.; Yang, Y.; Sun, X.; Lim, S.; Xie, S.; Guo, Z.; Xiong, W.; Kuroda, M.; Sakaue, H.; Hosaka, K.; et al. Brown-fat-mediated tumour suppression by cold-altered global metabolism. Nature 2022, 608, 421–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seale, P.; Conroe, H.M.; Estall, J.; Kajimura, S.; Frontini, A.; Ishibashi, J.; Cohen, P.; Cinti, S.; Spiegelman, B.M. Prdm16 determines the thermogenic program of subcutaneous white adipose tissue in mice. J. Clin. Invest. 2011, 121, 96–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hussain, M.F.; Roesler, A.; Kazak, L. Regulation of adipocyte thermogenesis: Mechanisms controlling obesity. FEBS J. 2020, 287, 3370–3385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bost, F.; Kaminski, L. The metabolic modulator PGC-1α in cancer. Am. J. Cancer Res. 2019, 9, 198–211. [Google Scholar]

- Andrade, J.M.O.; Barcala-Jorge, A.S.; Batista-Jorge, G.C.; Paraíso, A.F.; Freitas, K.M.; Lelis, D.F.; Guimarães, A.L.S.; de Paula, A.M.B.; Santos, S.H.S. Effect of resveratrol on expression of genes involved thermogenesis in mice and humans. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2019, 112, 108634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.J.; Zhang, H.S.; Liu, Y.; Huang, Y.H. Curcumin inhibits Ec109 cell growth via an AMPK-mediated metabolic switch. Life Sci. 2015, 134, 49–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enerbäck, S.; Jacobsson, A.; Simpson, E.M.; Guerra, C.; Yamashita, H.; Harper, M.E.; Kozak, L.P. Mice lacking mitochondrial uncoupling protein are cold-sensitive but not obese. Nature 1997, 387, 90–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyad-Ul-Ferdous, M.; Gul, I.; Raheem, M.A.; Pandey, V.; Qin, P. Mitochondrial UCP1: Potential thermogenic mechanistic switch for the treatment of obesity and neurodegenerative diseases using natural and epigenetic drug candidates. Phytomedicine 2024, 130, 155672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willows, J.W.; Blaszkiewicz, M.; Townsend, K.L. The Sympathetic Innervation of Adipose Tissues: Regulation, Functions, and Plasticity. Compr. Physiol. 2023, 13, 4985–5021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, W.; Daniel, K.W.; Robidoux, J.; Puigserver, P.; Medvedev, A.V.; Bai, X.; Floering, L.M.; Spiegelman, B.M.; Collins, S. p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase is the central regulator of cyclic AMP-dependent transcription of the brown fat uncoupling protein 1 gene. Mol. Cell Biol. 2004, 24, 3057–3067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, W.; Medvedev, A.V.; Daniel, K.W.; Collins, S. beta-Adrenergic activation of p38 MAP kinase in adipocytes: cAMP induction of the uncoupling protein 1 (UCP1) gene requires p38 MAP kinase. J. Biol. Chem. 2001, 276, 27077–27082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leiva, M.; Matesanz, N.; Pulgarín-Alfaro, M.; Nikolic, I.; Sabio, G. Uncovering the Role of p38 Family Members in Adipose Tissue Physiology. Front. Endocrinol. 2020, 11, 572089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robidoux, J.; Cao, W.; Quan, H.; Daniel, K.W.; Moukdar, F.; Bai, X.; Floering, L.M.; Collins, S. Selective activation of mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase kinase 3 and p38alpha MAP kinase is essential for cyclic AMP-dependent UCP1 expression in adipocytes. Mol. Cell Biol. 2005, 25, 5466–5479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bordicchia, M.; Liu, D.; Amri, E.Z.; Ailhaud, G.; Dessì-Fulgheri, P.; Zhang, C.; Takahashi, N.; Sarzani, R.; Collins, S. Cardiac natriuretic peptides act via p38 MAPK to induce the brown fat thermogenic program in mouse and human adipocytes. J. Clin. Invest. 2012, 122, 1022–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jäger, S.; Handschin, C.; St-Pierre, J.; Spiegelman, B.M. AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) action in skeletal muscle via direct phosphorylation of PGC-1alpha. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 12017–12022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mottillo, E.P.; Desjardins, E.M.; Crane, J.D.; Smith, B.K.; Green, A.E.; Ducommun, S.; Henriksen, T.I.; Rebalka, I.A.; Razi, A.; Sakamoto, K.; et al. Lack of Adipocyte AMPK Exacerbates Insulin Resistance and Hepatic Steatosis through Brown and Beige Adipose Tissue Function. Cell Metab. 2016, 24, 118–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seale, P.; Bjork, B.; Yang, W.; Kajimura, S.; Chin, S.; Kuang, S.; Scimè, A.; Devarakonda, S.; Conroe, H.M.; Erdjument-Bromage, H.; et al. PRDM16 controls a brown fat/skeletal muscle switch. Nature 2008, 454, 961–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajakumari, S.; Wu, J.; Ishibashi, J.; Lim, H.W.; Giang, A.H.; Won, K.J.; Reed, R.R.; Seale, P. EBF2 determines and maintains brown adipocyte identity. Cell Metab. 2013, 17, 562–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohno, H.; Shinoda, K.; Ohyama, K.; Sharp, L.Z.; Kajimura, S. EHMT1 controls brown adipose cell fate and thermogenesis through the PRDM16 complex. Nature 2013, 504, 163–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tseng, Y.H.; Kokkotou, E.; Schulz, T.J.; Huang, T.L.; Winnay, J.N.; Taniguchi, C.M.; Tran, T.T.; Suzuki, R.; Espinoza, D.O.; Yamamoto, Y.; et al. New role of bone morphogenetic protein 7 in brown adipogenesis and energy expenditure. Nature 2008, 454, 1000–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boström, P.; Wu, J.; Jedrychowski, M.P.; Korde, A.; Ye, L.; Lo, J.C.; Rasbach, K.A.; Boström, E.A.; Choi, J.H.; Long, J.Z.; et al. A PGC1-α-dependent myokine that drives brown-fat-like development of white fat and thermogenesis. Nature 2012, 481, 463–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rao, R.R.; Long, J.Z.; White, J.P.; Svensson, K.J.; Lou, J.; Lokurkar, I.; Jedrychowski, M.P.; Ruas, J.L.; Wrann, C.D.; Lo, J.C.; et al. Meteorin-like is a hormone that regulates immune-adipose interactions to increase beige fat thermogenesis. Cell 2014, 157, 1279–1291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takagi, M.; Kimura, K.; Nakashima, K.I.; Hirai, T.; Inoue, M. Induction of beige adipocytes by naturally occurring β3-adrenoceptor agonist p-synephrine. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2018, 836, 67–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baskaran, P.; Krishnan, V.; Ren, J.; Thyagarajan, B. Capsaicin induces browning of white adipose tissue and counters obesity by activating TRPV1 channel-dependent mechanisms. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2016, 173, 2369–2389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuse, S.; Endo, T.; Tanaka, R.; Kuroiwa, M.; Ando, A.; Kume, A.; Yamamoto, A.; Kuribayashi, K.; Somekawa, S.; Takeshita, M.; et al. Effects of Capsinoid Intake on Brown Adipose Tissue Vascular Density and Resting Energy Expenditure in Healthy, Middle-Aged Adults: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Study. Nutrients 2020, 12, 2676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Zhang, H.; Li, B.; Meng, X.; Wang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Yao, S.; Ma, Q.; Jin, L.; Yang, J.; et al. Berberine activates thermogenesis in white and brown adipose tissue. Nat. Commun. 2014, 5, 5493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Xia, M.; Duan, Y.; Zhang, L.; Jiang, H.; Hu, X.; Yan, H.; Zhang, Y.; Gu, Y.; Shi, H.; et al. Berberine promotes the recruitment and activation of brown adipose tissue in mice and humans. Cell Death Dis. 2019, 10, 468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

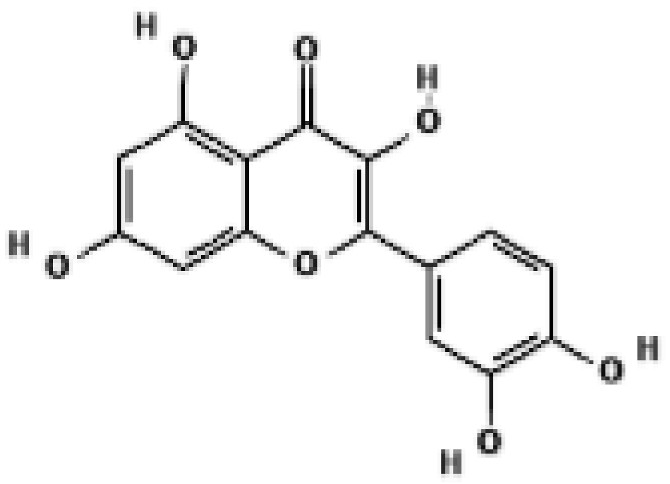

- Kong, L.; Zhang, W.; Liu, S.; Zhong, Z.; Zheng, G. Quercetin, Engelitin and Caffeic Acid of Smilax china L. Polyphenols, Stimulate 3T3-L1 Adipocytes to Brown-like Adipocytes Via β3-AR/AMPK Signaling Pathway. Plant Foods Hum. Nutr. 2022, 77, 529–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

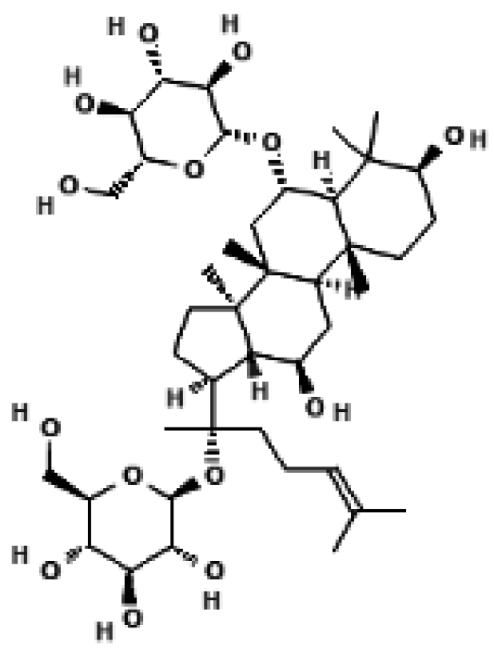

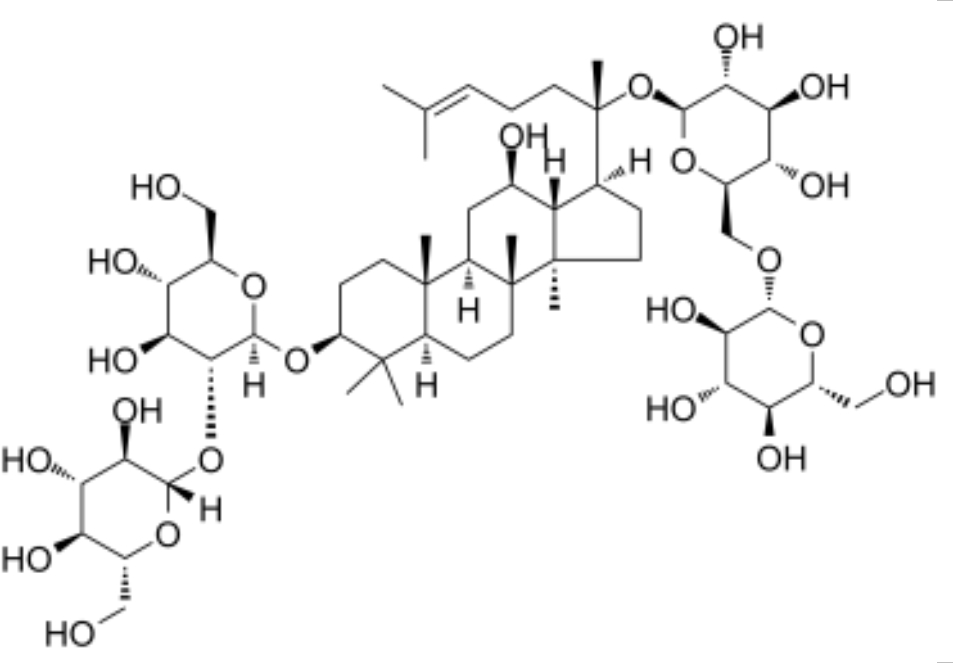

- Lee, K.; Seo, Y.J.; Song, J.H.; Chei, S.; Lee, B.Y. Ginsenoside Rg1 promotes browning by inducing UCP1 expression and mitochondrial activity in 3T3-L1 and subcutaneous white adipocytes. J. Ginseng. Res. 2019, 43, 589–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.J.; Park, M.; Sharma, A.; Kim, K.; Lee, H.J. Black Ginseng and Ginsenoside Rb1 Promote Browning by Inducing UCP1 Expression in 3T3-L1 and Primary White Adipocytes. Nutrients 2019, 11, 2747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

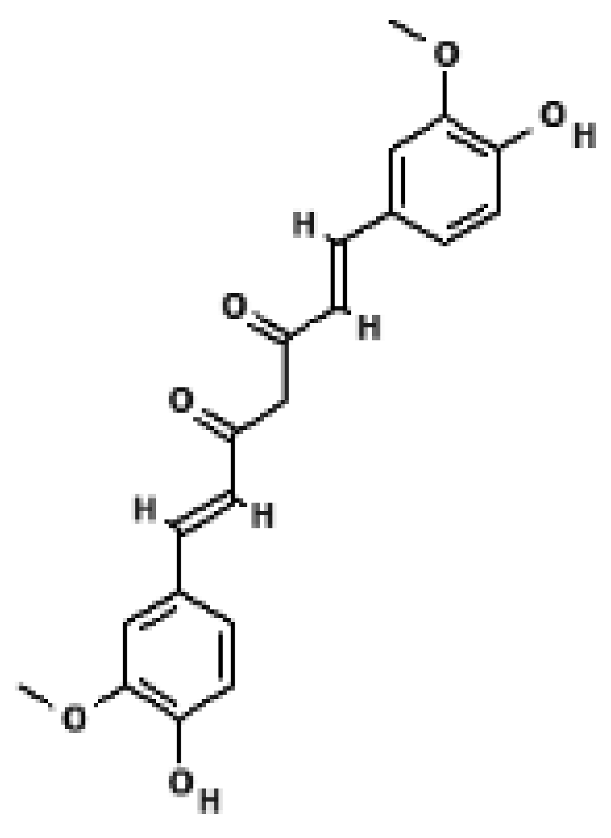

- Lone, J.; Choi, J.H.; Kim, S.W.; Yun, J.W. Curcumin induces brown fat-like phenotype in 3T3-L1 and primary white adipocytes. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2016, 27, 193–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, Z.; Revelo, X.; Shao, W.; Tian, L.; Zeng, K.; Lei, H.; Sun, H.S.; Woo, M.; Winer, D.; Jin, T. Dietary Curcumin Intervention Targets Mouse White Adipose Tissue Inflammation and Brown Adipose Tissue UCP1 Expression. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2018, 26, 547–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagouge, M.; Argmann, C.; Gerhart-Hines, Z.; Meziane, H.; Lerin, C.; Daussin, F.; Messadeq, N.; Milne, J.; Lambert, P.; Elliott, P.; et al. Resveratrol improves mitochondrial function and protects against metabolic disease by activating SIRT1 and PGC-1alpha. Cell 2006, 127, 1109–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Wu, J.Z.; Shen, J.Z.; Chen, L.; He, T.; Jin, M.W.; Liu, H. Pentamethylquercetin induces adipose browning and exerts beneficial effects in 3T3-L1 adipocytes and high-fat diet-fed mice. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, S.A.; Gogoi, P.; Ruprecht, J.J.; King, M.S.; Lee, Y.; Zögg, T.; Pardon, E.; Chand, D.; Steimle, S.; Copeman, D.M.; et al. Structural basis of purine nucleotide inhibition of human uncoupling protein 1. Sci. Adv. 2023, 9, eadh4251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Locke, R.M.; Rial, E.; Scott, I.D.; Nicholls, D.G. Fatty acids as acute regulators of the proton conductance of hamster brown-fat mitochondria. Eur. J. Biochem. 1982, 129, 373–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saraste, M.; Walker, J.E. Internal sequence repeats and the path of polypeptide in mitochondrial ADP/ATP translocase. FEBS Lett. 1982, 144, 250–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pebay-Peyroula, E.; Dahout-Gonzalez, C.; Kahn, R.; Trézéguet, V.; Lauquin, G.J.; Brandolin, G. Structure of mitochondrial ADP/ATP carrier in complex with carboxyatractyloside. Nature 2003, 426, 39–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruprecht, J.J.; Hellawell, A.M.; Harding, M.; Crichton, P.G.; McCoy, A.J.; Kunji, E.R. Structures of yeast mitochondrial ADP/ATP carriers support a domain-based alternating-access transport mechanism. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, E426–E434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crichton, P.G.; Lee, Y.; Ruprecht, J.J.; Cerson, E.; Thangaratnarajah, C.; King, M.S.; Kunji, E.R. Trends in thermostability provide information on the nature of substrate, inhibitor, and lipid interactions with mitochondrial carriers. J. Biol. Chem. 2015, 290, 8206–8217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cavalieri, R.; Hazebroek, M.K.; Cotrim, C.A.; Lee, Y.; Kunji, E.R.S.; Jastroch, M.; Keipert, S.; Crichton, P.G. Activating ligands of Uncoupling protein 1 identified by rapid membrane protein thermostability shift analysis. Mol. Metab. 2022, 62, 101526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garlid, K.D.; Jabůrek, M.; Jezek, P. The mechanism of proton transport mediated by mitochondrial uncoupling proteins. FEBS Lett. 1998, 438, 10–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garlid, K.D.; Orosz, D.E.; Modrianský, M.; Vassanelli, S.; Jezek, P. On the mechanism of fatty acid-induced proton transport by mitochondrial uncoupling protein. J. Biol. Chem. 1996, 271, 2615–2620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jagtap, U.A.; Rathod, S.; Shukla, R.; Paul, A.T. Computational insights into human UCP1 activators through molecular docking, MM-GBSA, and molecular dynamics simulation studies. Comput. Biol. Chem. 2024, 113, 108252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jack, B.U.; Ramharack, P.; Malherbe, C.; Gabuza, K.; Joubert, E.; Pheiffer, C. Cyclopia intermedia (Honeybush) Induces Uncoupling Protein 1 and Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor Alpha Expression in Obese Diabetic Female db/db Mice. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 3868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reyad-Ul-Ferdous, M.; Song, Y. Baicalein modulates mitochondrial function by upregulating mitochondrial uncoupling protein-1 (UCP1) expression in brown adipocytes, cytotoxicity, and computational studies. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2022, 222, 1963–1973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, Y.; Yu, T.J.; Xu, Y.; Ding, R.; Wang, Y.P.; Jiang, Y.Z.; Shao, Z.M. Emerging therapies in cancer metabolism. Cell Metab. 2023, 35, 1283–1303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kooshan, Z.; Cárdenas-Piedra, L.; Clements, J.; Batra, J. Glycolysis, the sweet appetite of the tumor microenvironment. Cancer Lett. 2024, 600, 217156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Y.; Chard Dunmall, L.S.; Cheng, Z.; Wang, Y.; Si, L. Natural products targeting glycolysis in cancer. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 1036502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vander Heiden, M.G.; Cantley, L.C.; Thompson, C.B. Understanding the Warburg effect: The metabolic requirements of cell proliferation. Science 2009, 324, 1029–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.W.; Zheng, C.C.; Huang, Y.N.; Chen, W.Y.; Yang, Q.S.; Ren, J.Y.; Wang, Y.M.; He, Q.Y.; Liao, H.X.; Li, B. Synephrine Hydrochloride Suppresses Esophageal Cancer Tumor Growth and Metastatic Potential through Inhibition of Galectin-3-AKT/ERK Signaling. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2018, 66, 9248–9258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, X.; Zhu, H.; Luo, D.; Ye, L.; Yin, H.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Y. Capsaicin inhibits glycolysis in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma by regulating hexokinase-2 expression. Mol. Med. Rep. 2018, 17, 6116–6121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Pan, L.; Gao, C.; Xu, H.; Li, Y.; Zhang, L.; Ma, L.; Meng, L.; Sun, X.; Qin, H. Quercetin Inhibits the Proliferation of Glycolysis-Addicted HCC Cells by Reducing Hexokinase 2 and Akt-mTOR Pathway. Molecules 2019, 24, 1993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, L.; Huang, S.; Yin, X.; Zan, Y.; Guo, Y.; Han, L. Quercetin suppresses the mobility of breast cancer by suppressing glycolysis through Akt-mTOR pathway mediated autophagy induction. Life Sci. 2018, 208, 123–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, M.; Song, H.Y.; Chen, L. Quercetin acts via the G3BP1/YWHAZ axis to inhibit glycolysis and proliferation in oral squamous cell carcinoma. Toxicol. Mech. Methods 2023, 33, 141–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siddiqui, F.A.; Prakasam, G.; Chattopadhyay, S.; Rehman, A.U.; Padder, R.A.; Ansari, M.A.; Irshad, R.; Mangalhara, K.; Bamezai, R.N.K.; Husain, M.; et al. Curcumin decreases Warburg effect in cancer cells by down-regulating pyruvate kinase M2 via mTOR-HIF1α inhibition. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 8323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brockmueller, A.; Sameri, S.; Liskova, A.; Zhai, K.; Varghese, E.; Samuel, S.M.; Büsselberg, D.; Kubatka, P.; Shakibaei, M. Resveratrol’s Anti-Cancer Effects through the Modulation of Tumor Glucose Metabolism. Cancers 2021, 13, 188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, G.; Zhang, P.; Chen, A.; Deng, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Lu, H.; Zhu, A.; Zhou, C.; Wu, Y.; Li, S. Aerobic glycolysis in colon cancer is repressed by naringin via the HIF1A pathway. J. Zhejiang Univ. Sci. B 2023, 24, 221–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, B.; Zhang, Y.; Hui, Q.; Wang, H.; Tao, K. Naringin suppresses the metabolism of A375 cells by inhibiting the phosphorylation of c-Src. Tumour Biol. 2016, 37, 3841–3850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawley, S.A.; Fullerton, M.D.; Ross, F.A.; Schertzer, J.D.; Chevtzoff, C.; Walker, K.J.; Peggie, M.W.; Zibrova, D.; Green, K.A.; Mustard, K.J.; et al. The ancient drug salicylate directly activates AMP-activated protein kinase. Science 2012, 336, 918–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, S.C.; Kim, S.M.; Choi, J.E.; Kim, C.H.; Duong, H.Q.; Han, S.I.; Kang, H.S. Sodium salicylate switches glucose depletion-induced necrosis to autophagy and inhibits high mobility group box protein 1 release in A549 lung adenocarcinoma cells. Oncol. Rep. 2008, 19, 1165–1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Floridi, A.; Castiglione, S.; Bianchi, C.; Mancini, A. Effect of rhein on the glucose metabolism of Ehrlich ascites tumor cells. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1990, 40, 217–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castiglione, S.; Fanciulli, M.; Bruno, T.; Evangelista, M.; Del Carlo, C.; Paggi, M.G.; Chersi, A.; Floridi, A. Rhein inhibits glucose uptake in Ehrlich ascites tumor cells by alteration of membrane-associated functions. Anticancer Drugs 1993, 4, 407–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, K.X.; Tan, W.S.; Wang, H.Y.; Gao, J.M.; Wang, S.Y.; Xie, M.L.; Deng, W.L. Hesperidin Suppressed Colorectal Cancer through Inhibition of Glycolysis. Chin. J. Integr. Med. 2025, 31, 529–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Korga, A.; Ostrowska, M.; Jozefczyk, A.; Iwan, M.; Wojcik, R.; Zgorka, G.; Herbet, M.; Vilarrubla, G.G.; Dudka, J. Apigenin and hesperidin augment the toxic effect of doxorubicin against HepG2 cells. BMC Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2019, 20, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, D.; Jin, J.; Liu, J.; Wang, Y.; Li, D.; He, Y. Baicalein Inhibits the Progression and Promotes Radiosensitivity of Esophageal Squamous Cell Carcinoma by Targeting HIF-1A. Drug Des. Devel. Ther. 2022, 16, 2423–2436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, J.; Li, X.; Yao, J.; Song, D.; Gu, Z.; Zheng, G.; Tu, C. Mangiferin targets PFKFB3 to inhibit glioblastoma progression by suppressing glycolysis and PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling. Brain Res Bull 2025, 230, 111520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, H.; Inam-Ur-Raheem, M.; Munir, S.; Rabail, R.; Kafeel, S.; Shahid, A.; Mousavi Khaneghah, A.; Aadil, R.M. Therapeutic potential of mangiferin in cancer: Unveiling regulatory pathways, mechanisms of action, and bioavailability enhancements—An updated review. Food Sci. Nutr. 2024, 12, 1413–1429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlova, N.N.; Thompson, C.B. The Emerging Hallmarks of Cancer Metabolism. Cell Metab. 2016, 23, 27–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saunier, E.; Antonio, S.; Regazzetti, A.; Auzeil, N.; Laprévote, O.; Shay, J.W.; Coumoul, X.; Barouki, R.; Benelli, C.; Huc, L.; et al. Resveratrol reverses the Warburg effect by targeting the pyruvate dehydrogenase complex in colon cancer cells. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 6945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pramanik, K.C.; Boreddy, S.R.; Srivastava, S.K. Role of mitochondrial electron transport chain complexes in capsaicin mediated oxidative stress leading to apoptosis in pancreatic cancer cells. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e20151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Chen, X.; Du, Z.; Li, G.; Chen, M.; Chen, X.; Liang, G.; Chen, T. Curcumin suppresses gastric tumor cell growth via ROS-mediated DNA polymerase γ depletion disrupting cellular bioenergetics. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2017, 36, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ming, M.; Sinnett-Smith, J.; Wang, J.; Soares, H.P.; Young, S.H.; Eibl, G.; Rozengurt, E. Dose-Dependent AMPK-Dependent and Independent Mechanisms of Berberine and Metformin Inhibition of mTORC1, ERK, DNA Synthesis and Proliferation in Pancreatic Cancer Cells. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e114573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Röhrig, F.; Schulze, A. The multifaceted roles of fatty acid synthesis in cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2016, 16, 732–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kisková, T.; Kassayová, M. Resveratrol Action on Lipid Metabolism in Cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 2704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, J.Z.; Ma, L.N.; Han, Y.; Liu, J.X.; Yang, W.Q.; Chen, L.; Liu, Y.; Hu, Y.; Jin, M.W. Pentamethylquercetin generates beneficial effects in monosodium glutamate-induced obese mice and C2C12 myotubes by activating AMP-activated protein kinase. Diabetologia 2012, 55, 1836–1846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henamayee, S.; Banik, K.; Sailo, B.L.; Shabnam, B.; Harsha, C.; Srilakshmi, S.; Vgm, N.; Baek, S.H.; Ahn, K.S.; Kunnumakkara, A.B. Therapeutic Emergence of Rhein as a Potential Anticancer Drug: A Review of Its Molecular Targets and Anticancer Properties. Molecules 2020, 25, 2278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.; Yang, L.; Liu, L.; Kong, L.; Sun, H.; Sun, Y.; Yin, F.; Yan, G.; Wang, X. Rhein: An Updated Review Concerning Its Biological Activity, Pharmacokinetics, Structure Optimization, and Future Pharmaceutical Applications. Pharmaceuticals 2024, 17, 1665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aggarwal, V.; Tuli, H.S.; Thakral, F.; Singhal, P.; Aggarwal, D.; Srivastava, S.; Pandey, A.; Sak, K.; Varol, M.; Khan, M.A.; et al. Molecular mechanisms of action of hesperidin in cancer: Recent trends and advancements. Exp. Biol. Med. 2020, 245, 486–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aird, K.M.; Zhang, R. Nucleotide metabolism, oncogene-induced senescence and cancer. Cancer Lett. 2015, 356, 204–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marverti, G.; Ligabue, A.; Lombardi, P.; Ferrari, S.; Monti, M.G.; Frassineti, C.; Costi, M.P. Modulation of the expression of folate cycle enzymes and polyamine metabolism by berberine in cisplatin-sensitive and -resistant human ovarian cancer cells. Int. J. Oncol. 2013, 43, 1269–1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontecave, M.; Lepoivre, M.; Elleingand, E.; Gerez, C.; Guittet, O. Resveratrol, a remarkable inhibitor of ribonucleotide reductase. FEBS Lett. 1998, 421, 277–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Song, J.; Park, S.; Ham, J.; Park, W.; Park, H.; An, G.; Hong, T.; Kim, H.S.; Song, G.; et al. Targeting Thymidylate Synthase and tRNA-Derived Non-Coding RNAs Improves Therapeutic Sensitivity in Colorectal Cancer. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 2158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altman, B.J.; Stine, Z.E.; Dang, C.V. From Krebs to clinic: Glutamine metabolism to cancer therapy. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2016, 16, 619–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, W.H.; Wang, F.C.; Jin, Z.; Zhu, L.; Zhang, J.X. Curcumin Synergizes with Cisplatin to Inhibit Colon Cancer through Targeting the MicroRNA-137-Glutaminase Axis. Curr. Med. Sci. 2022, 42, 108–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Wang, Q.; Lin, Z.; Yang, P.; Dou, K.; Zhang, R. Berberine Inhibits Growth of Liver Cancer Cells by Suppressing Glutamine Uptake. OncoTargets Ther. 2019, 12, 11751–11763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thongpon, P.; Intuyod, K.; Chomwong, S.; Pongking, T.; Klungsaeng, S.; Muisuk, K.; Charoenram, N.; Sitthirach, C.; Thanan, R.; Pinlaor, P.; et al. Curcumin synergistically enhances the efficacy of gemcitabine against gemcitabine-resistant cholangiocarcinoma via the targeting LAT2/glutamine pathway. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 16059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zong, W.X.; Rabinowitz, J.D.; White, E. Mitochondria and Cancer. Mol. Cell 2016, 61, 667–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferraro, M.; Di Vincenzo, S.; Lazzara, V.; Pinto, P.; Patella, B.; Inguanta, R.; Bruno, A.; Pace, E. Formoterol Exerts Anti-Cancer Effects Modulating Oxidative Stress and Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition Processes in Cigarette Smoke Extract Exposed Lung Adenocarcinoma Cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 16088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Qi, Q.; Feng, Z.; Zhang, X.; Huang, B.; Chen, A.; Prestegarden, L.; Li, X.; Wang, J. Berberine induces autophagy in glioblastoma by targeting the AMPK/mTOR/ULK1-pathway. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 66944–66958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Sui, W.; Mu, Z.; Xie, S.; Deng, J.; Li, S.; Seki, T.; Wu, J.; Jing, X.; He, X.; et al. Mirabegron displays anticancer effects by globally browning adipose tissues. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 7610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Yang, G.; Wan, L.; Li, B.; Lu, J.; Yu, Q.; Li, Y.; Han, Y.; Guo, C.; Zhang, J. Serum metabolic profiles reveal the effect of formoterol on cachexia in tumor-bearing mice. Mol. Biosyst. 2013, 9, 3015–3025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kershaw, J.C.; Elzey, B.D.; Guo, X.X.; Kim, K.H. Piceatannol, a Dietary Polyphenol, Alleviates Adipose Tissue Loss in Pre-Clinical Model of Cancer-Associated Cachexia via Lipolysis Inhibition. Nutrients 2022, 14, 2306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Gao, W.Q.; Wang, P.; Wang, T.Q.; Xu, W.C.; Zhu, X.Y.; Liu, H. Pentamethylquercetin Inhibits Hepatocellular Carcinoma Progression and Adipocytes-induced PD-L1 Expression via IFN-γ Signaling. Curr. Cancer Drug Targets 2020, 20, 868–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jang, B.Y.; Shin, M.K.; Han, D.H.; Sung, J.S. Curcumin Disrupts a Positive Feedback Loop between ADMSCs and Cancer Cells in the Breast Tumor Microenvironment via the CXCL12/CXCR4 Axis. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 2627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Xiong, B.; Lu, W.; Cheng, Y.; Zhu, J.; Ai, G.; Zhang, X.; Liu, X.; Cheng, Z. Senolytic drugs dasatinib and quercetin combined with Carboplatin or Olaparib reduced the peritoneal and adipose tissue metastasis of ovarian cancer. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2024, 174, 116474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vander Heiden, M.G.; DeBerardinis, R.J. Understanding the Intersections between Metabolism and Cancer Biology. Cell 2017, 168, 657–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kajimura, S.; Spiegelman, B.M.; Seale, P. Brown and Beige Fat: Physiological Roles beyond Heat Generation. Cell Metab. 2015, 22, 546–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Boström, P.; Sparks, L.M.; Ye, L.; Choi, J.H.; Giang, A.H.; Khandekar, M.; Virtanen, K.A.; Nuutila, P.; Schaart, G.; et al. Beige adipocytes are a distinct type of thermogenic fat cell in mouse and human. Cell 2012, 150, 366–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faubert, B.; Tasdogan, A.; Morrison, S.J.; Mathews, T.P.; DeBerardinis, R.J. Stable isotope tracing to assess tumor metabolism in vivo. Nat. Protoc. 2021, 16, 5123–5145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hensley, C.T.; Faubert, B.; Yuan, Q.; Lev-Cohain, N.; Jin, E.; Kim, J.; Jiang, L.; Ko, B.; Skelton, R.; Loudat, L.; et al. Metabolic Heterogeneity in Human Lung Tumors. Cell 2016, 164, 681–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Natural Product | Cells/Tissues | Dose Concentration | UCP1-Related Findings | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Natural β-adrenergic mimetics | ||||

p-Synephrine | Mouse SVF-derived beige adipocytes | 3.12–12.5 μM | ↑ UCP1 mRNA in a dose-dependent manner; induces beige morphology; effect abolished by β3-AR antagonist | [31] |

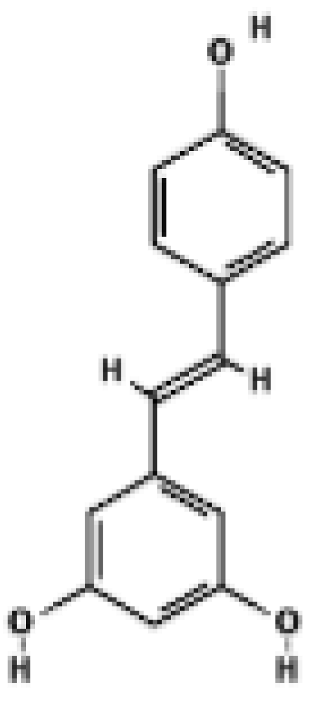

Capsaicin | Primary WAT preadipocytes, EF/SCF (mouse) | 0.1–10 μM (cells), 0.01% diet (mice) | TRPV1-dependent Ca2+ influx → CaMKII/AMPK/SIRT1 activation → ↑ UCP1, ↑ PRDM16, ↑ PGC1α → WAT browning and anti-obesity effect | [32] |

Capsinoid | Human brown adipose tissue (FDG-PET) | 9 mg/day (oral ingestion) | ↑ Whole-body energy expenditure → ↑ Cold-induced BAT activation (FDG uptake) → Activation of UCP1 positive depots | [33] |

| AMPK-activating natural products | ||||

Berberine | Primary brown adipocytes, primary inguinal white adipocytes, C3H10T1/2 adipocytes, BAT, iWAT | 0.5 μM, 2.5 μM (in vitro); 5 mg/kg/day i.p., 4 weeks (in vivo) | ↑ UCP1 mRNA/protein, ↑ PGC1α, ↑ PRDM16, WAT browning, ↑ oxygen consumption, ↑ whole-body thermogenesis | [34] |

| Human NAFLD patients (BAT), Mouse BAT, iWAT, eWAT, Mouse & human primary brown preadipocytes, Mouse BAT-SVF and C3H10-T1/2 cells | In vitro: 0.25~2 μM (dose-dependent), In vivo (mouse): 1.5 mg/kg/day i.p. for 6 weeks, In humans: 0.5 g orally, 3×/day for 1 month | ↑PRDM16 → ↑ UCP1 mRNA and protein in mouse and human brown adipocytes → ↑ Brown adipocyte differentiation → ↑ BAT mass & thermogenic activity | [35] | |

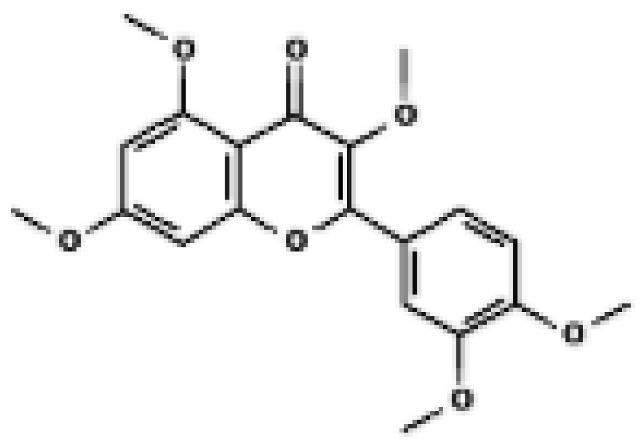

Quercetin | WAT, BAT; 3T3-L1 | 40 μg/mL | ↑ UCP1, ↑ AMPK | [36] |

Ginsenoside Rg1 | 3T3-L1 adipocytes; mouse subcutaneous white adipocytes (scWAT) | 25, 50, 100 μM (dose-dependent), 50 μM used for main experiments | ↑ PRDM16, ↑ PGC1α, ↑ UCP1 protein and mRNA in a dose-dependent manner → promotes adipocyte browning and mitochondrial biogenesis via AMPK activation | [37] |

Black ginseng extract; Ginsenoside Rb1 | 3T3-L1 adipocytes; Primary white adipocytes (PWATs) | 10, 20, 40 µM | ↑ UCP1, ↑ PRDM16, ↑ PGC1α, ↑ p-AMPK → promotes browning of 3T3-L1 and PWATs | [38] |

Curcumin | 3T3-L1 adipocytes; primary white adipocytes | 1–20 μM | ↑ UCP1, ↑ PRDM16, ↑ PGC1α, ↑ mitochondrial biogenesis; AMPK-dependent browning response | [39] |

| C57BL/6J mice (BAT, WAT), RAW264.7 macrophages, rat primary adipocytes, mBAC brown adipocytes | In vitro: 0.25–20 μM (RAW264.7, adipocytes, mBAC) In vivo: 1% dietary curcumin in HFD | ↑ UCP1 mRNA & protein in BAT, ↑ UCP1 promoter activity (PPARα/γ-dependent & independent) | [40] | |

| PRDM16-enhancing natural products | ||||

| Berberine | Human NAFLD patients (BAT), Mouse BAT, iWAT, eWAT, Mouse & human primary brown preadipocytes, Mouse BAT-SVF and C3H10-T1/2 cells | In vitro: 0.25~2 μM (dose-dependent), In vivo (mouse): 1.5 mg/kg/day i.p. for 6 weeks, In humans: 0.5 g orally, 3×/day for 1 month | ↑ PRDM16, ↑ UCP1 | [35] |

| Curcumin | 3T3-L1 adipocytes; primary white adipocytes | 1–20 μM | ↑ PRDM16, ↑ PGC1α, ↑ UCP1 | [39] |

| Ginsenoside Rg1 | 3T3-L1 adipocytes; mouse subcutaneous white adipocytes (scWAT) | 25, 50, 100 μM (dose-dependent), 50 μM used for main experiments | ↑ PRDM16, ↑ UCP1 | [37] |

| Ginsenoside Rb1 | 3T3-L1 adipocytes; Primary white adipocytes (PWATs) | 10, 20, 40 µM | ↑ PRDM16 | [38] |

| Mitochondrial biogenesis enhancers | ||||

Resveratrol | C57BL/6J mice BAT | 200–400 mg/kg/day, 15 weeks (diet) Plasma RSV 10–120 ng/mL | ↑ Mitochondrial size & cristae density in BAT and muscle ↑ mtDNA content (BAT & muscle) ↑ UCP1 mRNA in BAT | [41] |

PMQ | 3T3-L1 adipocytes; Epididymal WAT & BAT of HFD mice | In vitro: 0.1–10 µM (most effects at 10 µM) In vivo: HFD + 0.04% PMQ diet (≈40 mg/kg/day) | ↑ Mitochondrial markers (Cytochrome C) in WAT ↑ UCP1-positive multilocular adipocytes in WAT of HFD mice | [42] |

| Natural Product | Metabolic Pathway Inhibited | Key Targets/Mechanisms | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| p-Synephrine | Indirect inhibition of glycolysis via suppression of metabolic signaling | ↓ Galectin-3–mediated activation of AKT and ERK; inhibition of downstream glycolysis-supportive signaling pathways | [59] |

| Capsaicin | Inhibition of aerobic glycolysis and mitochondrial electron transport chain (ETC) | ↓ HK2, ↓ glucose uptake, ↓ lactate; inhibition of mitochondrial complexes I & III → ROS-mediated apoptosis | [60,79] |

| Berberine | Inhibition of glycolysis and oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) | Mitochondrial depolarization → AMPK activation; ↓ ATP; impaired glycolytic capacity and mitochondrial function | [81,98] |

| Quercetin | Inhibition of aerobic glycolysis | ↓ HK2, ↓ GLUT1, ↓ PKM2; ↓ Akt–mTOR signaling; ↓ glucose uptake, ↓lactate production | [61,62,63] |

| Curcumin | Suppression of glycolysis and mitochondrial respiration | ↓ PKM2 via mTOR–HIF-1α inhibition; ↓ glucose uptake and lactate; POLG depletion → mitochondrial dysfunction | [64,80] |

| Resveratrol | Inhibition of glycolysis and lipid synthesis | ↓ GLUT1, ↓ PFK1, ↓ PKM2, ↓ LDH; inhibition of PI3K–AKT–mTOR and HIF-1α; activation of PDH and mitochondrial oxidation | [65,78,83] |

| PMQ | Indirect inhibition of glycolysis-supportive signaling | ↑ AMPK → ↓ mTOR → ↓ anabolic/glycolytic signaling | [84] |

| Naringin | Inhibition of aerobic glycolysis in cancer cells | HIF-1α ↓ → ENO2 ↓ → glycolysis ↓; c-Src phosphorylation ↓ → glucose metabolism ↓ | [66,67] |

| Salsalate | Inhibition of glycolysis-supportive and anabolic metabolism | ↑ AMPK → ↓ mTOR/anabolic signals; ↑ fatty-acid oxidation; ↓ de novo lipogenesis | [68,69] |

| Rhein | Inhibition of glycolysis (glucose uptake → lactate production) | ↓ glucose transporter function → ↓ glucose uptake → ↓ lactate production | [70,71,85,86] |

| Mirabegron | Indirect modulation of tumour metabolism (via adipose browning) | ↑ β3-AR → ↑ UCP1 → ↑ thermogenesis → systemic fuel redistribution | [99] |

| Formoterol | Indirect modulation of tumour-associated metabolism | ↑ β2-AR → systemic substrate shift (glycolysis/TCA/lipid metabolites altered) | [97,100] |

| Hesperidin | Inhibition of glycolysis | ↓ HK2, ↓ LDHA; ↓ lactate; enhanced chemosensitivity with doxorubicin | [72,73,87] |

| Mangiferin | Inhibition of aerobic glycolysis | ↓ PFKFB3-mediated glycolysis → ↓ PI3K/AKT/mTOR signalling | [75,76] |

| Baicalein | Inhibition of HIF-1α–regulated glycolysis | ↓ HIF-1α → ↓ HIF-1α–controlled glycolytic genes | [74] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Moon, D.O. Natural Product Driven Activation of UCP1 and Tumor Metabolic Suppression: Integrating Thermogenic Nutrient Competition with Cancer Metabolic Reprogramming. Biomolecules 2026, 16, 90. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom16010090

Moon DO. Natural Product Driven Activation of UCP1 and Tumor Metabolic Suppression: Integrating Thermogenic Nutrient Competition with Cancer Metabolic Reprogramming. Biomolecules. 2026; 16(1):90. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom16010090

Chicago/Turabian StyleMoon, Dong Oh. 2026. "Natural Product Driven Activation of UCP1 and Tumor Metabolic Suppression: Integrating Thermogenic Nutrient Competition with Cancer Metabolic Reprogramming" Biomolecules 16, no. 1: 90. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom16010090

APA StyleMoon, D. O. (2026). Natural Product Driven Activation of UCP1 and Tumor Metabolic Suppression: Integrating Thermogenic Nutrient Competition with Cancer Metabolic Reprogramming. Biomolecules, 16(1), 90. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom16010090