Mesothelial Cells in Fibrosis: Focus on Intercellular Crosstalk

Abstract

1. Mesothelial Cells Characteristics and Functions

2. Mesothelial-to-Mesenchymal Transition (MMT)

3. Mesothelial Cells in Tissue Repair

4. Mesothelial Cells in Fibrosis

4.1. Pleural Fibrosis

4.2. Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis

4.3. Peritoneal Fibrosis Caused by Peritoneal Dialysis

4.4. Postoperative Adhesions

4.5. Cardiac Fibrosis

4.6. Molecular Mechanisms of Fibrosis and Mesothelial Cell Contribution

5. Mesothelial Crosstalk in Fibrosis

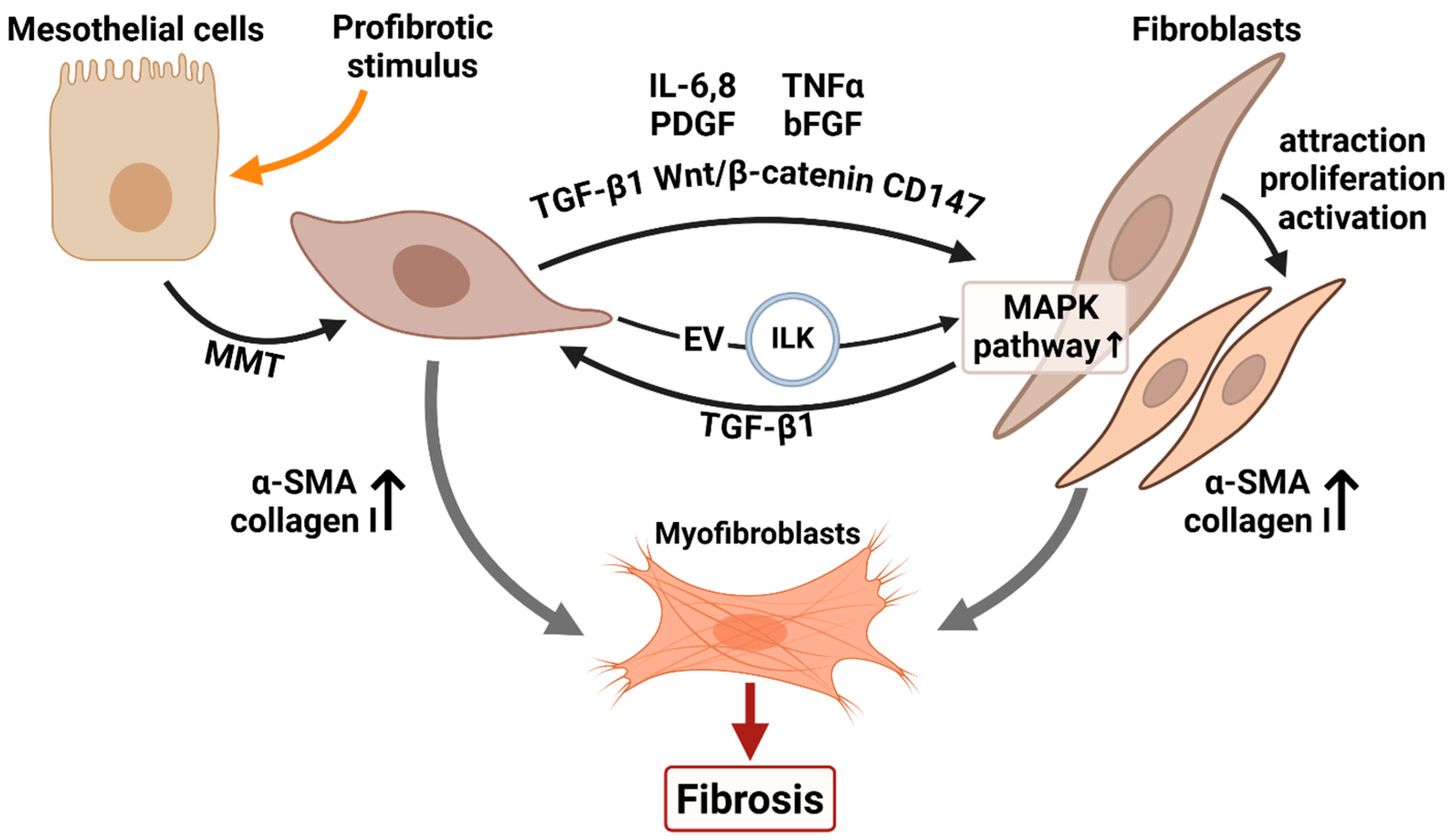

5.1. Interplay Between Mesothelial Cells and Fibroblasts

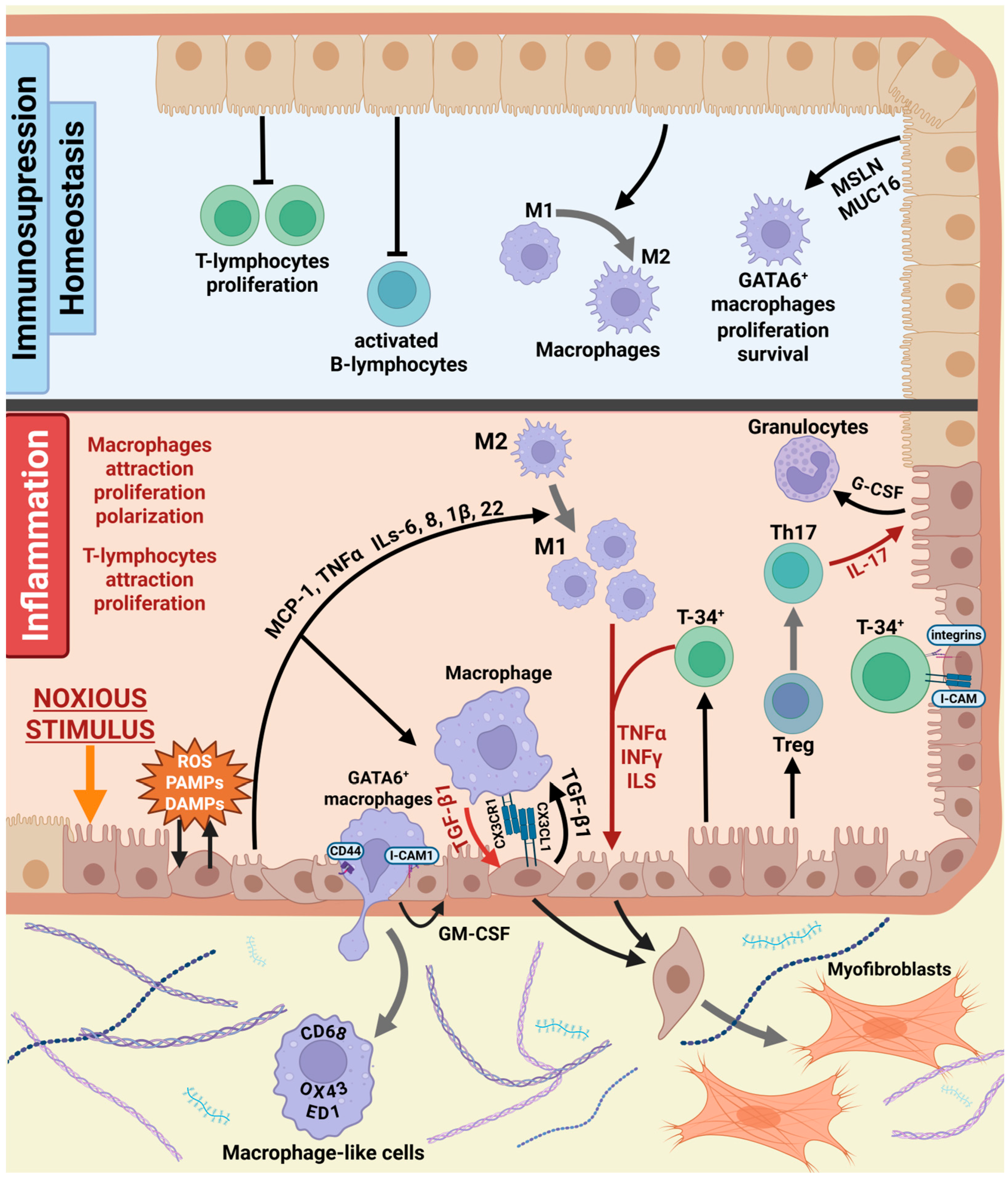

5.2. Communication Between Mesothelial and Immune Cells

5.3. Crosstalk Between Mesothelial and Endothelial Cells

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Karl, J.; Capel, B. Sertoli Cells of the Mouse Testis Originate from the Coelomic Epithelium. Dev. Biol. 1998, 203, 323–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitaker, D.; Papadimitriou, J.M.; Walters, M.N.-I. The Mesothelium: A Histochemical Study of Resting Mesothelial Cells. J. Pathol. 1980, 132, 273–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutsaers, S.E. The Mesothelial Cell. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2004, 36, 9–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kawanishi, K. Diverse Properties of the Mesothelial Cells in Health and Disease. Pleura Peritoneum 2016, 1, 79–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mutsaers, S.E. Mesothelial Cells: Their Structure, Function and Role in Serosal Repair. Respirology 2002, 7, 171–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutsaers, S.E.; Wilkosz, S. Structure and Function of Mesothelial Cells. Cancer Treat. Res. 2007, 134, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batra, H.; Antony, V.B. Pleural Mesothelial Cells in Pleural and Lung Diseases. J. Thorac. Dis. 2015, 7, 964–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metelmann, I.B.; Kraemer, S.; Steinert, M.; Langer, S.; Stock, P.; Kurow, O. Novel 3D Organotypic Co-Culture Model of Pleura. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0276978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagiwara, Y.; Hamada, Y.; Kuwahara, M.; Maeda, M.; Segawa, T.; Ishikawa, K.; Hino, O. Establishment of a Novel Specific ELISA System for Rat N- and C-ERC/Mesothelin. Rat ERC/Mesothelin in the Body Fluids of Mice Bearing Mesothelioma. Cancer Sci. 2008, 99, 666–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; Yamashita, Y.; Toyokuni, S. A Novel Method for Efficient Collection of Normal Mesothelial Cells In Vivo. J. Clin. Biochem. Nutr. 2010, 46, 265–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulyás, M.; Hjerpe, A. Proteoglycans and WT1 as Markers for Distinguishing Adenocarcinoma, Epithelioid Mesothelioma, and Benign Mesothelium. J. Pathol. 2003, 199, 479–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yung, S.; Chan, T.M. Hyaluronan—Regulator and Initiator of Peritoneal Inflammation and Remodeling. Int. J. Artif. Organs 2007, 30, 477–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, H.L.; Nie, H.G. Electrolyte and Fluid Transport in Mesothelial Cells. J. Epithel. Biol. Pharmacol. 2008, 1, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutsaers, S.E.; Prêle, C.M.A.; Pengelly, S.; Herrick, S.E. Mesothelial Cells and Peritoneal Homeostasis. Fertil. Steril. 2016, 106, 1018–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrick, S.E.; Wilm, B. Post-Surgical Peritoneal Scarring and Key Molecular Mechanisms. Biomolecules 2021, 11, 692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutsaers, S.E.; Birnie, K.; Lansley, S.; Herrick, S.E.; Lim, C.B.; Prêle, C.M. Mesothelial Cells in Tissue Repair and Fibrosis. Front. Pharmacol. 2015, 6, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mierzejewski, M.; Korczynski, P.; Krenke, R.; Janssen, J.P. Chemical Pleurodesis—A Review of Mechanisms Involved in Pleural Space Obliteration. Respir. Res. 2019, 20, 247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rougier, J.P.; Guia, S.; Hagège, J.; Nguyen, G.; Ronco, P.M. PAI-1 Secretion and Matrix Deposition in Human Peritoneal Mesothelial Cell Cultures: Transcriptional Regulation by TGF-Β1. Kidney Int. 1998, 54, 87–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bottles, K.D.; Laszik, Z.; Morrissey, J.H.; Kinasewitz, G.T. Tissue Factor Expression in Mesothelial Cells: Induction Both In Vivo and In Vitro. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 1997, 17, 164–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lüdemann, W.M.; Heide, D.; Kihm, L.; Zeier, M.; Scheurich, P.; Schwenger, V.; Ranzinger, J. TNF Signaling in Peritoneal Mesothelial Cells: Pivotal Role of CflipL. Perit. Dial. Int. 2017, 37, 250–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonjić, N.; Peri, G.; Bernasconi, S.; Sciacca, F.L.; Colotta, F.; Pelicci, P.; Lanfrancone, L.; Mantovani, A. Expression of Adhesion Molecules and Chemotactic Cytokines in Cultured Human Mesothelial Cells. J. Exp. Med. 1992, 176, 1165–1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acencio, M.M.P.; Soares, B.; Marchi, E.; Silva, C.S.R.; Teixeira, L.R.; Broaddus, V.C. Inflammatory Cytokines Contribute to Asbestos-Induced Injury of Mesothelial Cells. Lung 2015, 193, 831–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jantz, M.A.; Antony, V.B. Pathophysiology of the Pleura. Respiration 2008, 75, 121–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.H.; Lee, T.Y.; Lin, C.Y. Integrins Mediate Adherence and Migration of T Lymphocytes on Human Peritoneal Mesothelial Cells. Kidney Int. 2008, 74, 808–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visser, C.E.; Brouwer-Steenbergen, J.J.; Schadee-Eestermans, I.L.; Meijer, S.; Krediet, R.T.; Beelen, R.H. Ingestion of Staphylococcus Aureus, Staphylococcus Epidermidis, and Escherichia Coli by Human Peritoneal Mesothelial Cells. Infect. Immun. 1996, 64, 3425–3428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, B.J.; Lindau, D.; Ripper, D.; Stierhof, Y.D.; Glatzle, J.; Witte, M.; Beck, H.; Keppeler, H.; Lauber, K.; Rammensee, H.G.; et al. Phagocytosis of Dying Tumor Cells by Human Peritoneal Mesothelial Cells. J. Cell Sci. 2011, 124, 1644–1654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, T.J.; Zhang, X.Y.; Huo, Z.; Robertson, D.; Lovell, P.A.; Dalgleish, A.G.; Barton, D.P.J. Human Peritoneal Mesothelial Cells Display Phagocytic and Antigen-Presenting Functions to Contribute to Intraperitoneal Immunity. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 2016, 26, 833–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hausmann, M.J.; Rogachev, B.; Weiler, M.; Chaimovitz, C.; Douvdevani, A. Accessory Role of Human Peritoneal Mesothelial Cells in Antigen Presentation and T-Cell Growth. Kidney Int. 2000, 57, 476–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rennard, S.I.; Jaurand, M.C.; Bignon, J.; Kawanami, O.; Ferrans, V.J.; Davidson, J.; Crystal, R.G. Role of Pleural Mesothelial Cells in the Production of the Submesothelial Connective Tissue Matrix of Lung. Am. Rev. Respir. Dis. 1984, 130, 267–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, C.; Tarnuzzer, R.W.; Chegini, N. Expression of Matrix Metalloproteinases and Tissue Inhibitor of Matrix Metalloproteinases in Mesothelial Cells and Their Regulation by Transforming Growth Factor-β1. Wound Repair. Regen. 1999, 7, 477–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, L.; Sun, L.; Liu, F.; Peng, Y.; Duan, S. Connective Tissue Growth Factor Knockdown Attenuated Matrix Protein Production and Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor Expression Induced by Transforming Growth Factor-β1 in Cultured Human Peritoneal Mesothelial Cells. Ther. Apher. Dial. 2010, 14, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Cabrera, M. Mesenchymal Conversion of Mesothelial Cells Is a Key Event in the Pathophysiology of the Peritoneum during Peritoneal Dialysis. Adv. Med. 2014, 2014, 473134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yáñez-Mó, M.; Siljander, P.R.-M.; Andreu, Z.; Bedina Zavec, A.; Borràs, F.E.; Buzas, E.I.; Buzas, K.; Casal, E.; Cappello, F.; Carvalho, J.; et al. Biological Properties of Extracellular Vesicles and Their Physiological Functions. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2015, 4, 27066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Namvar, S.; Woolf, A.S.; Zeef, L.A.; Wilm, T.; Wilm, B.; Herrick, S.E. Functional Molecules in Mesothelial-to-mesenchymal Transition Revealed by Transcriptome Analyses. J. Pathol. 2018, 245, 491–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramundo, V.; Zanirato, G.; Aldieri, E. The Epithelial-to-Mesenchymal Transition (EMT) in the Development and Metastasis of Malignant Pleural Mesothelioma. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 12216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeisberg, M.; Hanai, J.; Sugimoto, H.; Mammoto, T.; Charytan, D.; Strutz, F.; Kalluri, R. BMP-7 Counteracts TGF-Β1–Induced Epithelial-to-Mesenchymal Transition and Reverses Chronic Renal Injury. Nat. Med. 2003, 9, 964–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nasreen, N.; Mohammed, K.A.; Mubarak, K.K.; Baz, M.A.; Akindipe, O.A.; Fernandez-Bussy, S.; Antony, V.B. Pleural Mesothelial Cell Transformation into Myofibroblasts and Haptotactic Migration in Response to TGF-Β1 in Vitro. Am. J. Physiol.-Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 2009, 297, L115–L124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pérez-Lozano, M.L.; Sandoval, P.; Rynne-Vidal, Á.; Aguilera, A.; Jiménez-Heffernan, J.A.; Albar-Vizcaíno, P.; Majano, P.L.; Sánchez-Tomero, J.A.; Selgas, R.; López-Cabrera, M. Functional Relevance of the Switch of VEGF Receptors/Co-Receptors during Peritoneal Dialysis-Induced Mesothelial to Mesenchymal Transition. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e60776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aashaq, S.; Batool, A.; Mir, S.A.; Beigh, M.A.; Andrabi, K.I.; Shah, Z.A. TGF-β Signaling: A Recap of SMAD-independent and SMAD-dependent Pathways. J. Cell Physiol. 2022, 237, 59–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debnath, P.; Huirem, R.S.; Dutta, P.; Palchaudhuri, S. Epithelial–Mesenchymal Transition and Its Transcription Factors. Biosci. Rep. 2022, 42, BSR20211754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.H.; Massagué, J. TGF-β in Developmental and Fibrogenic EMTs. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2022, 86, 136–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strippoli, R.; Moreno-Vicente, R.; Battistelli, C.; Cicchini, C.; Noce, V.; Amicone, L.; Marchetti, A.; del Pozo, M.A.; Tripodi, M. Molecular Mechanisms Underlying Peritoneal EMT and Fibrosis. Stem Cells Int. 2016, 2016, 3543678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saitoh, M. Transcriptional Regulation of EMT Transcription Factors in Cancer. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2023, 97, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, J.; Jain, S.; Azad, A.K.; Xu, X.; Yu, H.C.; Xu, Z.; Godbout, R.; Fu, Y. Notch and TGFβ Form a Positive Regulatory Loop and Regulate EMT in Epithelial Ovarian Cancer Cells. Cell. Signal. 2016, 28, 838–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakalenko, N.; Kuznetsova, E.; Malashicheva, A. The Complex Interplay of TGF-β and Notch Signaling in the Pathogenesis of Fibrosis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 10803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Yang, L.; Mei, J.; Li, Z.; Huang, Y.; Sun, H.; Zheng, K.; Kuang, H.; Luo, W. Knockdown of Notch Suppresses Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition and Induces Angiogenesis in Oral Submucous Fibrosis by Regulating TGF-Β1. Biochem. Genet. 2024, 62, 1055–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, F.; Li, T.; Qiu, F.; Fan, J.; Zhou, Q.; Ding, X.; Nie, J.; Yu, X. Preventive Effect of Notch Signaling Inhibition by a γ-Secretase Inhibitor on Peritoneal Dialysis Fluid-Induced Peritoneal Fibrosis in Rats. Am. J. Pathol. 2010, 176, 650–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, C.; Qin, C.; Sun, Y.; Liu, Y.; Tang, G.; Liao, Z.; Zhao, C.; Wu, C.; Wang, L. Bioceramics-Enhanced Patch Activates Epicardial Epithelial-to-Mesenchymal Transition via Notch Pathway for Cardiac Repair. Sci. Adv. 2025, 11, eads5978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeisberg, M.; Kalluri, R. The Role of Epithelial-to-Mesenchymal Transition in Renal Fibrosis. J. Mol. Med. 2004, 82, 175–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiskirchen, R. BMP-7 Counteracting TGF-Beta1 Activities in Organ Fibrosis. Front. Biosci. 2013, 18, 1407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piccolo, S.; Dupont, S.; Cordenonsi, M. The Biology of YAP/TAZ: Hippo Signaling and Beyond. Physiol. Rev. 2014, 94, 1287–1312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strippoli, R.; Sandoval, P.; Moreno-Vicente, R.; Rossi, L.; Battistelli, C.; Terri, M.; Pascual-Antón, L.; Loureiro, M.; Matteini, F.; Calvo, E.; et al. Caveolin1 and YAP Drive Mechanically Induced Mesothelial to Mesenchymal Transition and Fibrosis. Cell Death Dis. 2020, 11, 647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lua, I.; Balog, S.; Asahina, K. TAZ/WWTR1 Mediates Liver Mesothelial–Mesenchymal Transition Induced by Stiff Extracellular Environment, TGF-β1, and Lysophosphatidic Acid. J. Cell Physiol. 2022, 237, 2561–2573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koopmans, T.; Rinkevich, Y. Mesothelial to Mesenchyme Transition as a Major Developmental and Pathological Player in Trunk Organs and Their Cavities. Commun. Biol. 2018, 1, 170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Sun, Q.; Davis, F.; Mao, J.; Zhao, H.; Ma, D. Epithelial–Mesenchymal Transition in Organ Fibrosis Development: Current Understanding and Treatment Strategies. Burn. Trauma 2022, 10, tkac011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Que, J.; Wilm, B.; Hasegawa, H.; Wang, F.; Bader, D.; Hogan, B.L.M. Mesothelium Contributes to Vascular Smooth Muscle and Mesenchyme during Lung Development. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 16626–16630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilm, B.; Ipenberg, A.; Hastie, N.D.; Burch, J.B.E.; Bader, D.M. The Serosal Mesothelium Is a Major Source of Smooth Muscle Cells of the Gut Vasculature. Development 2005, 132, 5317–5328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rinkevich, Y.; Mori, T.; Sahoo, D.; Xu, P.X.; Bermingham, J.R.; Weissman, I.L. Identification and Prospective Isolation of a Mesothelial Precursor Lineage Giving Rise to Smooth Muscle Cells and Fibroblasts for Mammalian Internal Organs, and Their Vasculature. Nat. Cell Biol. 2012, 14, 1251–1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braitsch, C.M.; Combs, M.D.; Quaggin, S.E.; Yutzey, K.E. Pod1/Tcf21 Is Regulated by Retinoic Acid Signaling and Inhibits Differentiation of Epicardium-Derived Cells into Smooth Muscle in the Developing Heart. Dev. Biol. 2012, 368, 345–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Tuyn, J.; Atsma, D.E.; Winter, E.M.; van der Velde-van Dijke, I.; Pijnappels, D.A.; Bax, N.A.M.; Knaän-Shanzer, S.; Gittenberger-de Groot, A.C.; Poelmann, R.E.; van der Laarse, A.; et al. Epicardial Cells of Human Adults Can Undergo an Epithelial-to-Mesenchymal Transition and Obtain Characteristics of Smooth Muscle Cells In Vitro. Stem Cells 2007, 25, 271–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lachaud, C.C.; López-Beas, J.; Soria, B.; Hmadcha, A. EGF-Induced Adipose Tissue Mesothelial Cells Undergo Functional Vascular Smooth Muscle Differentiation. Cell Death Dis. 2014, 5, e1304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lachaud, C.C.; Pezzolla, D.; Domínguez-Rodríguez, A.; Smani, T.; Soria, B.; Hmadcha, A. Functional Vascular Smooth Muscle-like Cells Derived from Adult Mouse Uterine Mesothelial Cells. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e55181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lansley, S.M.; Searles, R.G.; Hoi, A.; Thomas, C.; Moneta, H.; Herrick, S.E.; Thompson, P.J.; Mark, N.; Sterrett, G.F.; Prêle, C.M.; et al. Mesothelial Cell Differentiation into Osteoblast- and Adipocyte-like Cells. J. Cell Mol. Med. 2011, 15, 2095–2105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lua, I.; Asahina, K. The Role of Mesothelial Cells in Liver Development, Injury, and Regeneration. Gut Liver 2016, 10, 166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mutsaers, S.E.; Whitaker, D.; Papadimitriou, J.M. Mesothelial Regeneration Is Not Dependent on Subserosal Cells. J. Pathol. 2000, 190, 86–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapiro, L.; Holste, J.L.; Muench, T.; diZerega, G. Rapid Reperitonealization and Wound Healing in a Preclinical Model of Abdominal Trauma Repair with a Composite Mesh. Int. J. Surg. 2015, 22, 86–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foley-Comer, A.J.; Herrick, S.E.; Al-Mishlab, T.; Prêle, C.M.; Laurent, G.J.; Mutsaers, S.E. Evidence for Incorporation of Free-Floating Mesothelial Cells as a Mechanism of Serosal Healing. J. Cell Sci. 2002, 115, 1383–1389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jantz, M.A.; Antony, V.B. Pleural Fibrosis. Clin. Chest Med. 2006, 27, 181–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raghu, G.; Chen, S.-Y.; Hou, Q.; Yeh, W.-S.; Collard, H.R. Incidence and Prevalence of Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis in US Adults 18–64 Years Old. Eur. Respir. J. 2016, 48, 179–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raghu, G.; Collard, H.R.; Egan, J.J.; Martinez, F.J.; Behr, J.; Brown, K.K.; Colby, T.V.; Cordier, J.-F.; Flaherty, K.R.; Lasky, J.A.; et al. An Official ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT Statement: Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis: Evidence-Based Guidelines for Diagnosis and Management. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2011, 183, 788–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zolak, J.S.; Jagirdar, R.; Surolia, R.; Karki, S.; Oliva, O.; Hock, T.; Guroji, P.; Ding, Q.; Liu, R.M.; Bolisetty, S.; et al. Pleural Mesothelial Cell Differentiation and Invasion in Fibrogenic Lung Injury. Am. J. Pathol. 2013, 182, 1239–1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yung, S.; Chan, T.M. Pathophysiological Changes to the Peritoneal Membrane during PD-Related Peritonitis: The Role of Mesothelial Cells. Mediat. Inflamm. 2012, 2012, 484167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J. Molecular Mechanisms of AGE/RAGE-Mediated Fibrosis in the Diabetic Heart. World J. Diabetes 2014, 5, 860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, M.; Xiang, F.L.; Braitsch, C.M.; Yutzey, K.E. Epicardium-Derived Fibroblasts in Heart Development and Disease. J. Mol. Cell Cardiol. 2016, 91, 23–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wynn, T.A.; Ramalingam, T.R. Mechanisms of Fibrosis: Therapeutic Translation for Fibrotic Disease. Nat. Med. 2012, 18, 1028–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, R.; Guo, T.; Li, J. Mechanisms of Peritoneal Mesothelial Cells in Peritoneal Adhesion. Biomolecules 2022, 12, 1498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, B.C.; Santana, A.; Xu, Q.P.; Petersen, M.J.; Campbell, E.J.; Hoidal, J.R.; Welgus, H.G. Metalloproteinases and Tissue Inhibitor of Metalloproteinases in Mesothelial Cells. Cellular Differentiation Influences Expression. J. Clin. Investig. 1993, 91, 1792–1799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ishimura, T.; Ishii, A.; Yamada, H.; Osaki, K.; Toda, N.; Mori, K.P.; Ohno, S.; Kato, Y.; Handa, T.; Sugioka, S.; et al. Matrix Metalloproteinase-10 Deficiency Has Protective Effects against Peritoneal Inflammation and Fibrosis via Transcription Factor NFκΒ Pathway Inhibition. Kidney Int. 2023, 104, 929–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merkle, M.; Ribeiro, A.; Sauter, M.; Ladurner, R.; Mussack, T.; Sitter, T.; Wörnle, M. Effect of Activation of Viral Receptors on the Gelatinases MMP-2 and MMP-9 in Human Mesothelial Cells. Matrix Biol. 2010, 29, 202–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukudome, K.; Fujimoto, S.; Sato, Y.; Hisanaga, S.; Eto, T. Peritonitis Increases MMP-9 Activity in Peritoneal Effluent from CAPD Patients. Nephron 2001, 87, 35–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bajaj, M.S.; Pendurthi, U.; Koenig, K.; Pueblitz, S.; Idell, S. Tissue Factor Pathway Inhibitor Expression by Human Pleural Mesothelial and Mesothelioma Cells. Eur. Respir. J. 2000, 15, 1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idell, S.; Zwieb, C.; Kumar, A.; Koenig, K.B.; Johnson, A.R. Pathways of Fibrin Turnover of Human Pleural Mesothelial Cells In Vitro. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 1992, 7, 414–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivarsson, M.L.; Holmdahl, L.; Falk, P.; Mölne, J.; Risberg, B. Characterization and Fibrinolytic Properties of Mesothelial Cells Isolated from Peritoneal Lavage. Scand. J. Clin. Lab. Investig. 1998, 58, 195–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koninckx, P.R.; Gomel, V.; Ussia, A.; Adamyan, L. Role of the Peritoneal Cavity in the Prevention of Postoperative Adhesions, Pain, and Fatigue. Fertil. Steril. 2016, 106, 998–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Honjo, K.; Munakata, S.; Tashiro, Y.; Salama, Y.; Shimazu, H.; Eiamboonsert, S.; Dhahri, D.; Ichimura, A.; Dan, T.; Miyata, T.; et al. Plasminogen Activator Inhibitor-1 Regulates Macrophage-dependent Postoperative Adhesion by Enhancing EGF-HER1 Signaling in Mice. FASEB J. 2017, 31, 2625–2637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wight, T.N.; Potter-Perigo, S. The Extracellular Matrix: An Active or Passive Player in Fibrosis? Am. J. Physiol.-Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2011, 301, G950–G955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baum, J.; Duffy, H.S. Fibroblasts and Myofibroblasts: What Are We Talking About? J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 2011, 57, 376–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Younesi, F.S.; Miller, A.E.; Barker, T.H.; Rossi, F.M.V.; Hinz, B. Fibroblast and Myofibroblast Activation in Normal Tissue Repair and Fibrosis. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2024, 25, 617–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, A.H.; Chen, J.Y.; Lin, J.K. Myofibroblastic Conversion of Mesothelial Cells. Kidney Int. 2003, 63, 1530–1539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brønnum, H.; Andersen, D.C.; Schneider, M.; Yaël Nossent, A.; Nielsen, S.B.; Sheikh, S.P. Islet-1 Is a Dual Regulator of Fibrogenic Epithelial-to-Mesenchymal Transition in Epicardial Mesothelial Cells. Exp. Cell Res. 2013, 319, 424–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Yu, F.; Lu, Y.Z.; Cheng, P.P.; Liang, L.M.; Wang, M.; Chen, S.J.; Huang, Y.; Song, L.J.; He, X.L.; et al. Crosstalk between Pleural Mesothelial Cell and Lung Fibroblast Contributes to Pulmonary Fibrosis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA)—Mol. Cell Res. 2020, 1867, 118806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lua, I.; Li, Y.; Pappoe, L.S.; Asahina, K. Myofibroblastic Conversion and Regeneration of Mesothelial Cells in Peritoneal and Liver Fibrosis. Am. J. Pathol. 2015, 185, 3258–3273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilm, T.P.; Tanton, H.; Mutter, F.; Foisor, V.; Middlehurst, B.; Ward, K.; Benameur, T.; Hastie, N.; Wilm, B. Restricted Differentiative Capacity of Wt1-Expressing Peritoneal Mesothelium in Postnatal and Adult Mice. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 15940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sontake, V.; Kasam, R.K.; Sinner, D.; Korfhagen, T.R.; Reddy, G.B.; White, E.S.; Jegga, A.G.; Madala, S.K. Wilms’ Tumor 1 Drives Fibroproliferation and Myofibroblast Transformation in Severe Fibrotic Lung Disease. JCI Insight 2018, 3, e121252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadri, S.; Fischer, A.; Mück-Häusl, M.; Han, W.; Kadri, A.; Lin, Y.; Yang, L.; Hu, S.; Ye, H.; Ramesh, P.; et al. A Mesothelial Differentiation Gateway Drives Fibrosis. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 8295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kis, K.; Liu, X.; Hagood, J.S. Myofibroblast Differentiation and Survival in Fibrotic Disease. Expert Rev. Mol. Med. 2011, 13, e27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kramann, R.; DiRocco, D.P.; Humphreys, B.D. Understanding the Origin, Activation and Regulation of Matrix-Producing Myofibroblasts for Treatment of Fibrotic Disease. J. Pathol. 2013, 231, 273–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Micallef, L.; Vedrenne, N.; Billet, F.; Coulomb, B.; Darby, I.A.; Desmoulière, A. The Myofibroblast, Multiple Origins for Major Roles in Normal and Pathological Tissue Repair. Fibrogenesis Tissue Repair 2012, 5, S5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Homps-Legrand, M.; Crestani, B.; Mailleux, A.A. Origins of Pathological Myofibroblasts in Lung Fibrosis: Insights from Lineage Tracing Mouse Models in the Single-Cell RNA Sequencing Era. Am. J. Physiol.-Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 2023, 324, L737–L746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, X.; Nikolic-Paterson, D.J.; Lan, H.Y. TGF-β: The Master Regulator of Fibrosis. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 2016, 12, 325–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, C.; Huang, J.Q.; Light, R.W. The Effects of Erythromycin on the Viability and the Secretion of TNF-α and TGF-β1 and Expression of Connexin43 by Human Pleural Mesothelial Cells. Respirology 2005, 10, 567–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saed, G.M.; Kruger, M.; Diamond, M.P. Expression of Transforming Growth Factor-β and Extracellular Matrix by Human Peritoneal Mesothelial Cells and by Fibroblasts from Normal Peritoneum and Adhesions: Effect of Tisseel. Wound Repair Regen. 2004, 12, 557–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saed, G.M.; Zhang, W.; Diamond, M.P.; Chegini, N.; Holmdahl, L. Transforming Growth Factor Beta Isoforms Production by Human Peritoneal Mesothelial Cells after Exposure to Hypoxia. Am. J. Reprod. Immunol. 2000, 43, 285–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antony, V.B.; Sahn, S.A.; Mossman, B.; Gail, D.B.; Kalica, A. Pleural Cell Biology in Health and Disease. Am. Rev. Respir. Dis. 1992, 145, 1236–1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yue, X.; Shan, B.; Lasky, J.A. TGF-β: Titan of Lung Fibrogenesis. Curr. Enzym. Inhib. 2010, 6, 10.2174/10067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vallée, A.; Lecarpentier, Y. TGF-β in Fibrosis by Acting as a Conductor for Contractile Properties of Myofibroblasts. Cell Biosci. 2019, 9, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biernacka, A.; Dobaczewski, M.; Frangogiannis, N.G. TGF-β Signaling in Fibrosis. Growth Factors 2011, 29, 196–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, R.; Raines, E.W.; Bowen-Pope, D.F. The Biology of Platelet-Derived Growth Factor. Cell 1986, 46, 155–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pierce, G.F.; Mustoe, T.A.; Altrock, B.W.; Deuel, T.F.; Thomason, A. Role of Platelet-derived Growth Factor in Wound Healing. J. Cell Biochem. 1991, 45, 319–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.T.; Chang, Y.T.; Pan, S.Y.; Chou, Y.H.; Chang, F.C.; Yeh, P.Y.; Liu, Y.H.; Chiang, W.C.; Chen, Y.M.; Wu, K.D.; et al. Lineage Tracing Reveals Distinctive Fates for Mesothelial Cells and Submesothelial Fibroblasts during Peritoneal Injury. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2014, 25, 2847–2858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamson, I.Y.; Prieditis, H.; Young, L. Lung Mesothelial Cell and Fibroblast Responses to Pleural and Alveolar Macrophage Supernatants and to Lavage Fluids from Crocidolite-Exposed Rats. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 1997, 16, 650–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierce, G.F.; Mustoe, T.A.; Lingelbach, J.; Masakowski, V.R.; Griffin, G.L.; Senior, R.M.; Deuel, T.F. Platelet-Derived Growth Factor and Transforming Growth Factor-Beta Enhance Tissue Repair Activities by Unique Mechanisms. J. Cell Biol. 1989, 109, 429–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antony, V.B.; Nasreen, N.; Mohammed, K.A.; Sriram, P.S.; Frank, W.; Schoenfeld, N.; Loddenkemper, R. Talc Pleurodesis. Chest 2004, 126, 1522–1528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, Y.S.; Tsai, S.Y.; Lin, S.L.; Chen, Y.T.; Tsai, P.S. Methylglyoxal-Stimulated Mesothelial Cells Prompted Fibroblast-to-Proto-Myofibroblast Transition. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lv, L.L.; Feng, Y.; Wu, M.; Wang, B.; Li, Z.L.; Zhong, X.; Wu, W.J.; Chen, J.; Ni, H.F.; Tang, T.T.; et al. Exosomal MiRNA-19b-3p of Tubular Epithelial Cells Promotes M1 Macrophage Activation in Kidney Injury. Cell Death Differ. 2020, 27, 210–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, M.; Shi, J.; Sheng, M. Exosomes: The New Mediator of Peritoneal Membrane Function. Kidney Blood Press. Res. 2018, 43, 1010–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Q.; Sun, Y.; Peng, L.; Sun, J.; Sha, Z.; Lin, H.; Li, Y.; Li, C.; Li, H.; Shang, H.; et al. Extracellular Vesicle-packaged ILK from Mesothelial Cells Promotes Fibroblast Activation in Peritoneal Fibrosis. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2023, 12, e12334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, M.W.; Rossi, D.; Peterson, M.; Smith, K.; Sikström, K.; White, E.S.; Connett, J.E.; Henke, C.A.; Larsson, O.; Bitterman, P.B. Fibrotic Extracellular Matrix Activates a Profibrotic Positive Feedback Loop. J. Clin. Investig. 2014, 124, 1622–1635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrera, J.; Henke, C.A.; Bitterman, P.B. Extracellular Matrix as a Driver of Progressive Fibrosis. J. Clin. Investig. 2018, 128, 45–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, H.; Zou, R.; Su, J.; Chen, X.; Yang, H.; An, N.; Yang, C.; Tang, J.; Liu, H.; Yao, C. Sterile Inflammation of Peritoneal Membrane Caused by Peritoneal Dialysis: Focus on the Communication between Immune Cells and Peritoneal Stroma. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1387292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, K.N.; Leung, J.C.K. Inflammation in Peritoneal Dialysis. Nephron Clin. Pract. 2010, 116, c11–c18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helmke, A.; Nordlohne, J.; Balzer, M.S.; Dong, L.; Rong, S.; Hiss, M.; Shushakova, N.; Haller, H.; von Vietinghoff, S. CX3CL1–CX3CR1 Interaction Mediates Macrophage-Mesothelial Cross Talk and Promotes Peritoneal Fibrosis. Kidney Int. 2019, 95, 1405–1417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, V.; Platell, C.; Hall, J.C. Peritoneal Mesothelial Cells Produce Inflammatory Related Cytokines. ANZ J. Surg. 2004, 74, 997–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Grevenstein, W.M.U.; Hofland, L.J.; van Rossen, M.E.E.; van Koetsveld, P.M.; Jeekel, J.; van Eijck, C.H.J. Inflammatory Cytokines Stimulate the Adhesion of Colon Carcinoma Cells to Mesothelial Monolayers. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2007, 52, 2775–2783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anders, H.J.; Schaefer, L. Beyond Tissue Injury—Damage-Associated Molecular Patterns, Toll-Like Receptors, and Inflammasomes Also Drive Regeneration and Fibrosis. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2014, 25, 1387–1400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raby, A.C.; González-Mateo, G.T.; Williams, A.; Topley, N.; Fraser, D.; López-Cabrera, M.; Labéta, M.O. Targeting Toll-like Receptors with Soluble Toll-like Receptor 2 Prevents Peritoneal Dialysis Solution–Induced Fibrosis. Kidney Int. 2018, 94, 346–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zheng, Z.; Lin, Y.; He, R.; Liu, J.; Yang, X. Proinflammatory Effect of High Glucose Concentrations on HMrSV5 Cells via the Autocrine Effect of HMGB1. Front. Physiol. 2017, 8, 762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nevado, J.; Peiró, C.; Vallejo, S.; El-Assar, M.; Lafuente, N.; Matesanz, N.; Azcutia, V.; Cercas, E.; Sánchez-Ferrer, C.F.; Rodríguez-Mañas, L. Amadori Adducts Activate Nuclear Factor-κ B-related Proinflammatory Genes in Cultured Human Peritoneal Mesothelial Cells. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2005, 146, 268–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuo, H.; Tamura, M.; Kabashima, N.; Serino, R.; Tokunaga, M.; Shibata, T.; Matsumoto, M.; Aijima, M.; Oikawa, S.; Anai, H.; et al. Prednisolone Inhibits Hyperosmolarity-Induced Expression of MCP-1 via NF-ΚB in Peritoneal Mesothelial Cells. Kidney Int. 2006, 69, 736–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, T.; Wang, Y.; Nayak, A.; Nast, C.C.; Quang, L.; LaPage, J.; Andalibi, A.; Adler, S.G. Janus Kinase Signaling Activation Mediates Peritoneal Inflammation and Injury in Vitro and in Vivo in Response to Dialysate. Kidney Int. 2014, 86, 1187–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.S.; Kim, Y.S.; Jee, Y.K.; Myong, N.H.; Lee, K.Y. Interleukin-8 Production in Tuberculous Pleurisy: Role of Mesothelial Cells Stimulated by Cytokine Network Involving Tumour Necrosis Factor-α and Interleukin-1β. Scand. J. Immunol. 2003, 57, 463–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mierzejewski, M.; Paplinska-Goryca, M.; Korczynski, P.; Krenke, R. Primary Human Mesothelial Cell Culture in the Evaluation of the Inflammatory Response to Different Sclerosing Agents Used for Pleurodesis. Physiol. Rep. 2021, 9, e14846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheller, J.; Ohnesorge, N.; Rose-John, S. Interleukin-6 Trans-Signalling in Chronic Inflammation and Cancer. Scand. J. Immunol. 2006, 63, 321–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, T.T.T.; Karmouty-Quintana, H.; Melicoff, E.; Le, T.T.T.; Weng, T.; Chen, N.-Y.; Pedroza, M.; Zhou, Y.; Davies, J.; Philip, K.; et al. Blockade of IL-6 Trans Signaling Attenuates Pulmonary Fibrosis. J. Immunol. 2014, 193, 3755–3768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capobianco, A.; Cottone, L.; Monno, A.; Manfredi, A.A.; Rovere-Querini, P. The Peritoneum: Healing, Immunity, and Diseases. J. Pathol. 2017, 243, 137–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delo, J.; Forton, D.; Triantafyllou, E.; Singanayagam, A. Peritoneal Immunity in Liver Disease. Livers 2023, 3, 240–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanov, S.; Gallerand, A.; Gros, M.; Stunault, M.I.; Merlin, J.; Vaillant, N.; Yvan-Charvet, L.; Guinamard, R.R. Mesothelial Cell CSF1 Sustains Peritoneal Macrophage Proliferation. Eur. J. Immunol. 2019, 49, 2012–2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, C.W.; Bagadia, P.; Barisas, D.A.G.; Jarjour, N.N.; Wong, R.; Ohara, T.; Muegge, B.D.; Lu, Q.; Xiong, S.; Edelson, B.T.; et al. Mesothelium-Derived Factors Shape GATA6-Positive Large Cavity Macrophages. J. Immunol. 2022, 209, 742–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Kubes, P. A Reservoir of Mature Cavity Macrophages That Can Rapidly Invade Visceral Organs to Affect Tissue Repair. Cell 2016, 165, 668–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amari, M.; Taguchi, K.; Iwahara, M.; Oharaseki, T.; Yokouchi, Y.; Naoe, S.; Takahashi, K. Interaction between Mesothelial Cells and Macrophages in the Initial Process of Pleural Adhesion: Ultrastructural Studies Using Adhesion Molecules. Med. Mol. Morphol. 2006, 39, 187–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasreen, N.; Mohammed, K.A.; Ward, M.J.; Antony, V.B. Mycobacterium-Induced Transmesothelial Migration of Monocytes into Pleural Space: Role of Intercellular Adhesion Molecule–1 in Tuberculous Pleurisy. J. Infect. Dis. 1999, 180, 1616–1623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellingan, G.J.; Xu, P.; Cooksley, H.; Cauldwell, H.; Shock, A.; Bottoms, S.; Haslett, C.; Mutsaers, S.E.; Laurent, G.J. Adhesion Molecule–Dependent Mechanisms Regulate the Rate of Macrophage Clearance During the Resolution of Peritoneal Inflammation. J. Exp. Med. 2002, 196, 1515–1521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suarez, J.S.; Novelli, F.; Goto, K.; Ehara, M.; Steele, M.; Kim, J.H.; Zolondick, A.A.; Xue, J.; Xu, R.; Saito, M.; et al. HMGB1 Released by Mesothelial Cells Drives the Development of Asbestos-Induced Mesothelioma. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2023, 120, e2307999120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumann, M.H.; Heinrich, K.; Sahn, S.A.; Strange, C. Pleural Macrophages Differentially Alter Mesothelial Cell Growth and Collagen Production. Inflammation 1993, 17, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, J.; Li, Q.; Sheng, M.; Zheng, M.; Yu, M.; Zhang, L. The Role of TLR4 in M1 Macrophage-Induced Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition of Peritoneal Mesothelial Cells. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 2016, 40, 1538–1548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, L.; Yu, Q.; Liu, D.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Lu, J.; Ma, X.; Huang, F.; Han, J.; Wei, L.; et al. Epithelial–Mesenchymal Transition of Peritoneal Mesothelial Cells Is Enhanced by M2c Macrophage Polarization. Immunol. Investig. 2022, 51, 301–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, S.; Balogh, P.; Kiss, A.L. Mesothelial Cells Can Detach from the Mesentery and Differentiate into Macrophage-like Cells. APMIS 2011, 119, 782–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, S.; Balogh, P.; Nagy, N.; Kiss, A.L. Epithelial-To-Mesenchymal Transition Induced by Freund’s Adjuvant Treatment in Rat Mesothelial Cells: A Morphological and Immunocytochemical Study. Pathol. Oncol. Res. 2012, 18, 641–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, S.; Zsiros, V.; Dóczi, N.; Szabó, A.; Biczó, Á.; Kiss, A.L. GM-CSF and GM-CSF Receptor Have Regulatory Role in Transforming Rat Mesenteric Mesothelial Cells into Macrophage-like Cells. Inflamm. Res. 2016, 65, 827–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zsiros, V.; Kiss, A.L. Cellular and Molecular Events of Inflammation Induced Transdifferentiation (EMT) and Regeneration (MET) in Mesenteric Mesothelial Cells. Inflamm. Res. 2020, 69, 1173–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, M.L.; Tong, Z.H.; Jin, X.G.; Zhang, J.C.; Wang, X.J.; Ma, W.L.; Yin, W.; Zhou, Q.; Ye, H.; Shi, H.Z. Regulation of CD4+ T Cells by Pleural Mesothelial Cells via Adhesion Molecule-Dependent Mechanisms in Tuberculous Pleurisy. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e74624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witowski, J.; Ksiązek, K.; Warnecke, C.; Kuźlan, M.; Korybalska, K.; Tayama, H.; Wiśniewska-Elnur, J.; Pawlaczyk, K.; Trómińska, J.; Bręborowicz, A.; et al. Role of Mesothelial Cell-Derived Granulocyte Colony-Stimulating Factor in Interleukin-17-Induced Neutrophil Accumulation in the Peritoneum. Kidney Int. 2007, 71, 514–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Witowski, J.; Pawlaczyk, K.; Breborowicz, A.; Scheuren, A.; Kuzlan-Pawlaczyk, M.; Wisniewska, J.; Polubinska, A.; Friess, H.; Gahl, G.M.; Frei, U.; et al. IL-17 Stimulates Intraperitoneal Neutrophil Infiltration Through the Release of GROα Chemokine from Mesothelial Cells. J. Immunol. 2000, 165, 5814–5821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bettelli, E.; Carrier, Y.; Gao, W.; Korn, T.; Strom, T.B.; Oukka, M.; Weiner, H.L.; Kuchroo, V.K. Reciprocal Developmental Pathways for the Generation of Pathogenic Effector TH17 and Regulatory T Cells. Nature 2006, 441, 235–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Littman, D.R.; Rudensky, A.Y. Th17 and Regulatory T Cells in Mediating and Restraining Inflammation. Cell 2010, 140, 845–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Lopes, J.E.; Chong, M.M.W.; Ivanov, I.I.; Min, R.; Victora, G.D.; Shen, Y.; Du, J.; Rubtsov, Y.P.; Rudensky, A.Y.; et al. TGF-β-Induced Foxp3 Inhibits TH17 Cell Differentiation by Antagonizing RORγt Function. Nature 2008, 453, 236–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korn, T.; Anderson, A.C.; Bettelli, E.; Oukka, M. The Dynamics of Effector T Cells and Foxp3+ Regulatory T Cells in the Promotion and Regulation of Autoimmune Encephalomyelitis. J. Neuroimmunol. 2007, 191, 51–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liappas, G.; Gónzalez-Mateo, G.T.; Majano, P.; Sánchez- Tomero, J.A.; Ruiz-Ortega, M.; Rodrigues Díez, R.; Martín, P.; Sanchez-Díaz, R.; Selgas, R.; López-Cabrera, M.; et al. T Helper 17/Regulatory T Cell Balance and Experimental Models of Peritoneal Dialysis-Induced Damage. Biomed. Res. Int. 2015, 2015, 416480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helmke, A.; Hüsing, A.M.; Gaedcke, S.; Brauns, N.; Balzer, M.S.; Reinhardt, M.; Hiss, M.; Shushakova, N.; de Luca, D.; Prinz, I.; et al. Peritoneal Dialysate-range Hypertonic Glucose Promotes T-cell IL-17 Production That Induces Mesothelial Inflammation. Eur. J. Immunol. 2021, 51, 354–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gauthier, B.R.; Rubio-Contreras, D.; Gómez-Rosado, J.C.; Capitán-Morales, L.C.; Hmadcha, A.; Soria, B.; Lachaud, C.C. Human Omental Mesothelial Cells Impart an Immunomodulatory Landscape Impeding B- and T-Cell Activation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 5924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.Y.; Kift-Morgan, A.; Moser, B.; Topley, N.; Eberl, M. Suppression of Pro-Inflammatory T-Cell Responses by Human Mesothelial Cells. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2013, 28, 1743–1750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitayama, J.; Emoto, S.; Yamaguchi, H.; Ishigami, H.; Yamashita, H.; Seto, Y.; Matsuzaki, K.; Watanabe, T. CD90(+)CD45(−) Intraperitoneal Mesothelial-like Cells Inhibit T Cell Activation by Production of Arginase I. Cell Immunol. 2014, 288, 8–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramjee, V.; Li, D.; Manderfield, L.J.; Liu, F.; Engleka, K.A.; Aghajanian, H.; Rodell, C.B.; Lu, W.; Ho, V.; Wang, T.; et al. Epicardial YAP/TAZ Orchestrate an Immunosuppressive Response Following Myocardial Infarction. J. Clin. Investig. 2017, 127, 899–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, C.L.; Bittinger, F.; Skarke, C.C.; Wagner, M.; Köhler, H.; Walgenbach, S.; Kirkpatrick, J. Effects of Cytokines on the Expression of Cell Adhesion Molecules by Cultured Human Omental Mesothelial Cells. Pathobiology 1995, 63, 204–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terri, M.; Trionfetti, F.; Montaldo, C.; Cordani, M.; Tripodi, M.; Lopez-Cabrera, M.; Strippoli, R. Mechanisms of Peritoneal Fibrosis: Focus on Immune Cells–Peritoneal Stroma Interactions. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 607204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sacnun, J.M.; Herzog, R.; Kratochwill, K. Proteomic Study of Mesothelial and Endothelial Cross-Talk: Key Lessons. Expert. Rev. Proteom. 2022, 19, 289–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ito, Y.; Sun, T.; Tawada, M.; Kinashi, H.; Yamaguchi, M.; Katsuno, T.; Kim, H.; Mizuno, M.; Ishimoto, T. Pathophysiological Mechanisms of Peritoneal Fibrosis and Peritoneal Membrane Dysfunction in Peritoneal Dialysis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 8607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanumegowda, C.; Farkas, L.; Kolb, M. Angiogenesis in Pulmonary Fibrosis. Chest 2012, 142, 200–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, N.; Gu, L.; Jia, J.; Wang, X.; Wang, L.; Yang, M.; Yuan, W. Endothelin-1 Triggers Human Peritoneal Mesothelial Cells’ Proliferation via ERK1/2-Ets-1 Signaling Pathway and Contributes to Endothelial Cell Angiogenesis. J. Cell Biochem. 2019, 120, 3539–3546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinashi, H.; Ito, Y.; Sun, T.; Katsuno, T.; Takei, Y. Roles of the TGF-β–VEGF-C Pathway in Fibrosis-Related Lymphangiogenesis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 2487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bates, D.O. Vascular Endothelial Growth Factors and Vascular Permeability. Cardiovasc. Res. 2010, 87, 262–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shibuya, M. Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor and Its Receptor System: Physiological Functions in Angiogenesis and Pathological Roles in Various Diseases. J. Biochem. 2013, 153, 13–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boulanger, E.; Grossin, N.; Wautier, M.P.; Taamma, R.; Wautier, J.L. Mesothelial RAGE Activation by AGEs Enhances VEGF Release and Potentiates Capillary Tube Formation. Kidney Int. 2007, 71, 126–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Béguin, E.P.; van den Eshof, B.L.; Hoogendijk, A.J.; Nota, B.; Mertens, K.; Meijer, A.B.; van den Biggelaar, M. Integrated Proteomic Analysis of Tumor Necrosis Factor α and Interleukin 1β-Induced Endothelial Inflammation. J. Proteom. 2019, 192, 89–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerhardt, T.; Ley, K. Monocyte Trafficking across the Vessel Wall. Cardiovasc. Res. 2015, 107, 321–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Medrano-Bosch, M.; Simón-Codina, B.; Jiménez, W.; Edelman, E.R.; Melgar-Lesmes, P. Monocyte-Endothelial Cell Interactions in Vascular and Tissue Remodeling. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1196033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, K.; Qin, W.; Jeffers, A.; Owens, S.; Destarac, L.; Idell, S.; Rao, L.V.M.; Tucker, T.A.; Keshava, S. Extracellular Vesicles Contribute to the Pathophysiology and Progression of Pleural Fibrosis by Promoting Mesothelial-to-Mesenchymal Transition and Neoangiogenesis. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 2025, 73, 938–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aoki, S.; Takezawa, T.; Oshikata-Miyazaki, A.; Ikeda, S.; Kuroyama, H.; Chimuro, T.; Oguchi, Y.; Noguchi, M.; Narisawa, Y.; Toda, S. Epithelial-to-Mesenchymal Transition and Slit Function of Mesothelial Cells Are Regulated by the Cross Talk between Mesothelial Cells and Endothelial Cells. Am. J. Physiol.-Ren. Physiol. 2014, 306, F116–F122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Bakalenko, N.; Kuznetsova, E.; Dergilev, K.; Beloglazova, I.; Malashicheva, A. Mesothelial Cells in Fibrosis: Focus on Intercellular Crosstalk. Biomolecules 2026, 16, 85. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom16010085

Bakalenko N, Kuznetsova E, Dergilev K, Beloglazova I, Malashicheva A. Mesothelial Cells in Fibrosis: Focus on Intercellular Crosstalk. Biomolecules. 2026; 16(1):85. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom16010085

Chicago/Turabian StyleBakalenko, Nadezhda, Evdokiya Kuznetsova, Konstantin Dergilev, Irina Beloglazova, and Anna Malashicheva. 2026. "Mesothelial Cells in Fibrosis: Focus on Intercellular Crosstalk" Biomolecules 16, no. 1: 85. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom16010085

APA StyleBakalenko, N., Kuznetsova, E., Dergilev, K., Beloglazova, I., & Malashicheva, A. (2026). Mesothelial Cells in Fibrosis: Focus on Intercellular Crosstalk. Biomolecules, 16(1), 85. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom16010085