Phosphomimetic Thrombospondin-1 Modulates Integrin β1-FAK Signaling and Vascular Cell Functions

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Cell Cultures

2.3. SDS-PAGE and Western Blotting

2.4. Transfection and Scratch Assay

2.5. Electric Cell-Substrate Impedance Sensing (ECIS) Measurements

2.6. High Content Screening (HCS) Confocal Microscopy

2.7. Immunoprecipitation and GST Pull-Down Assay

2.8. ELISA

2.9. MTT Assay

2.10. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

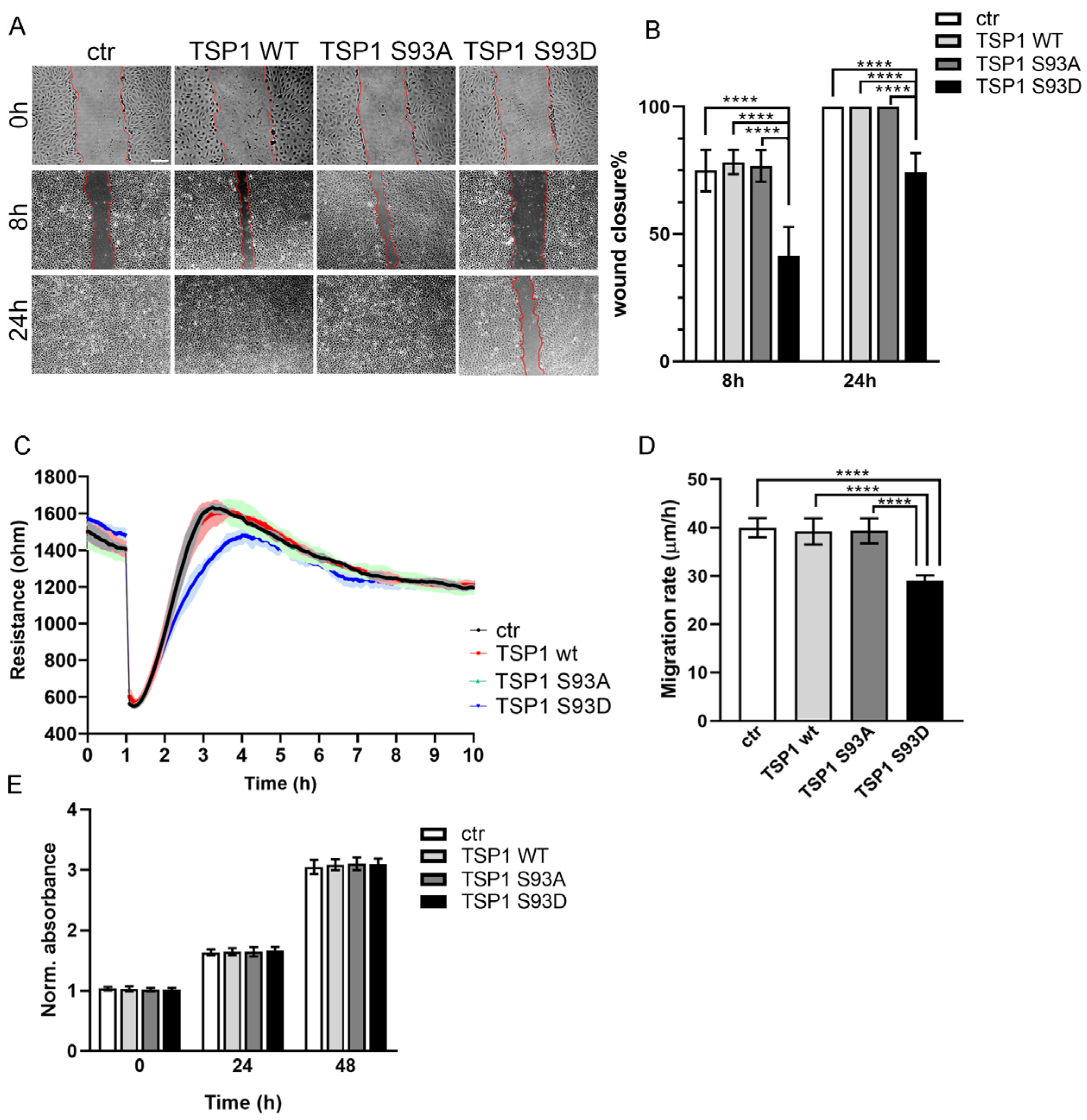

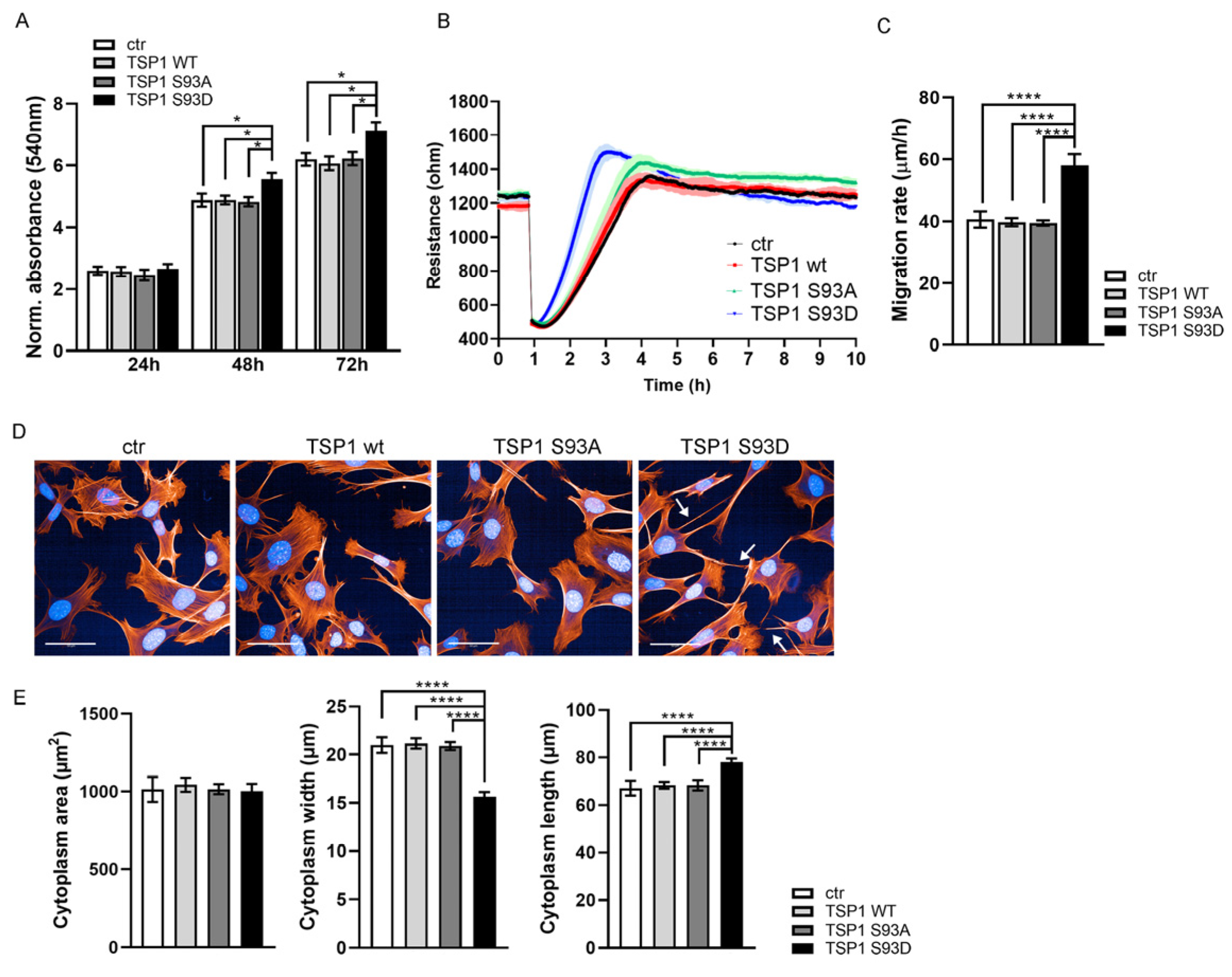

3.1. TSP1S93D Acts as a Negative Regulator of EC Migration

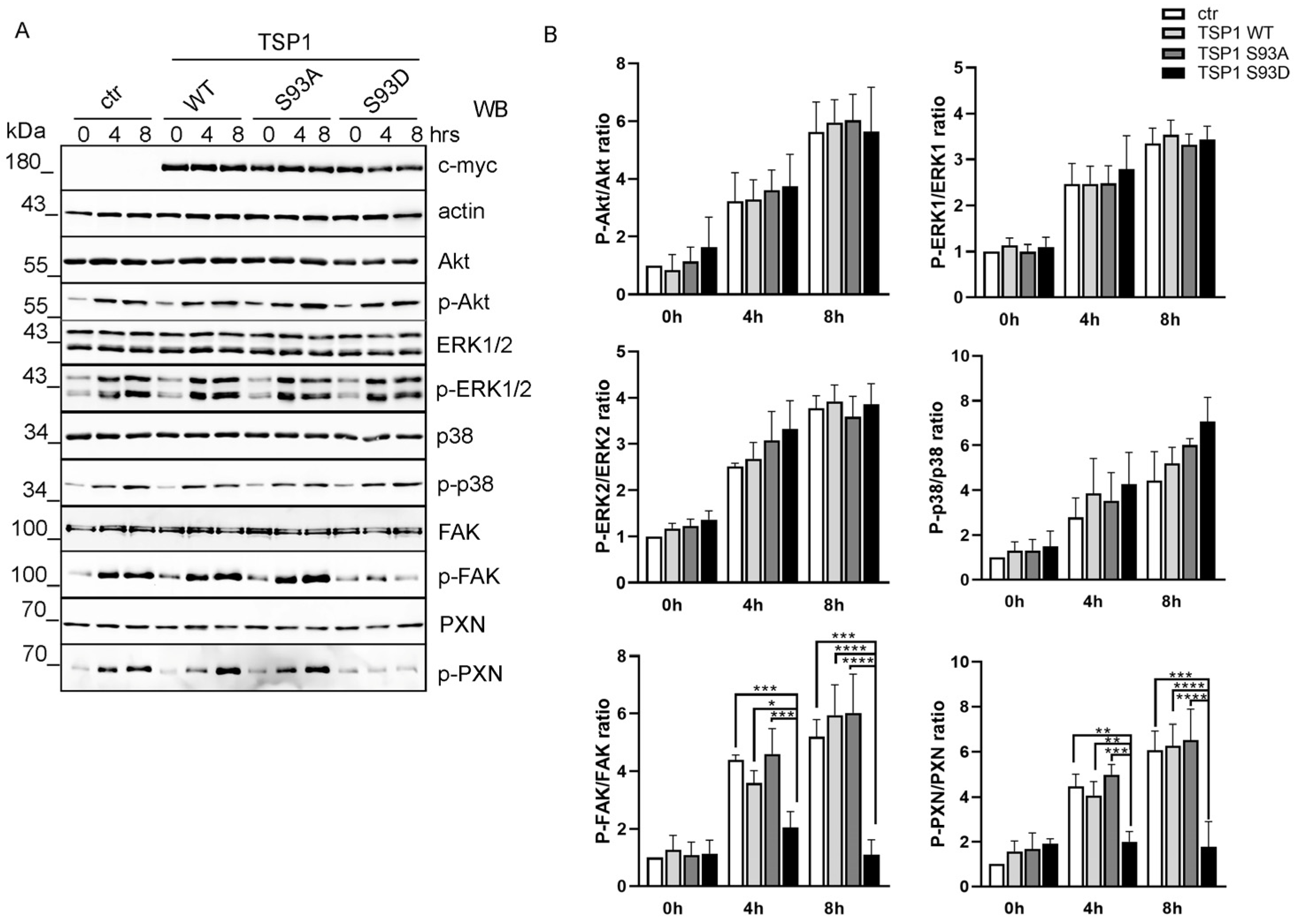

3.2. TSP1S93D Inhibits FAK Phosphorylation During Cell Migration

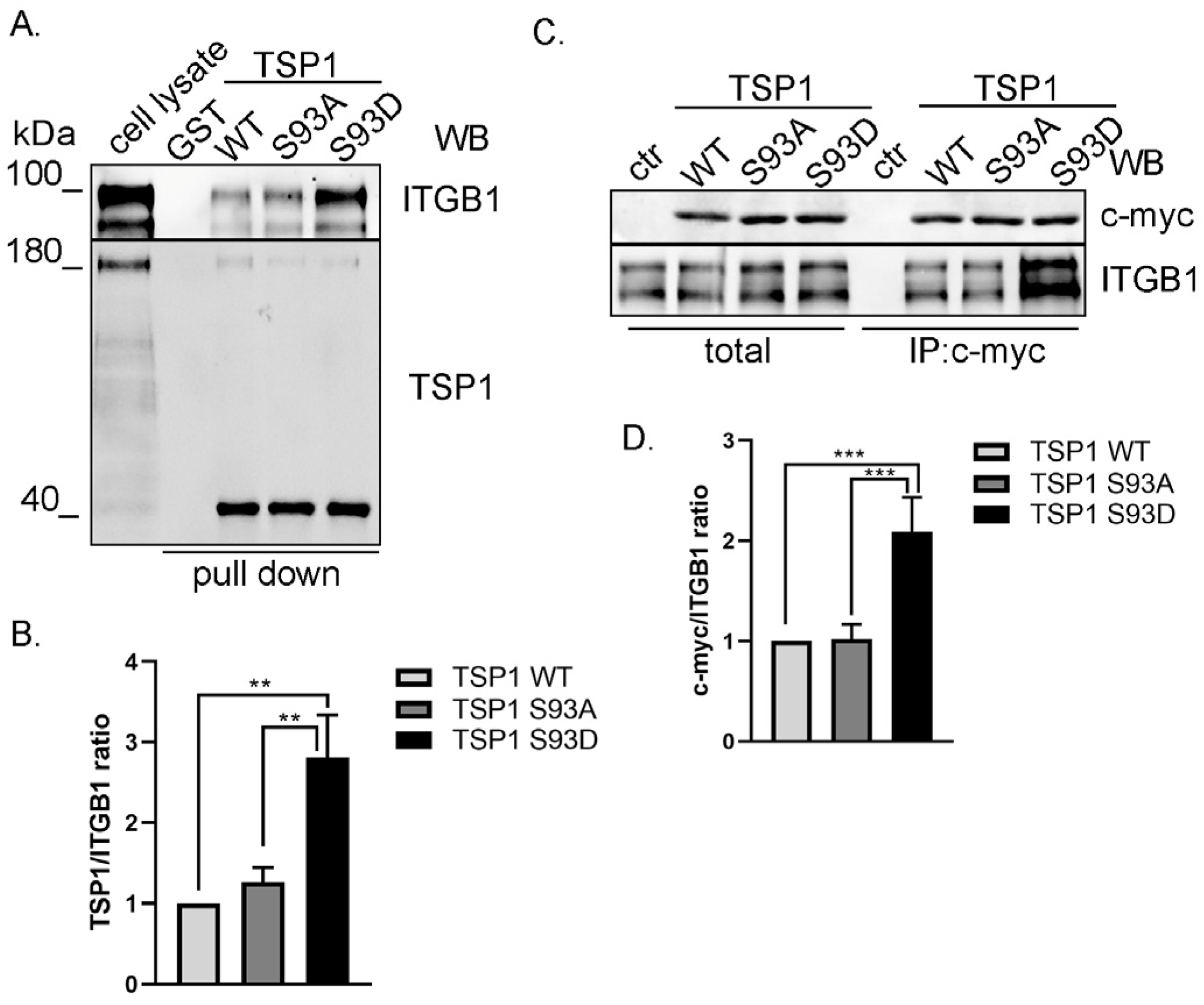

3.3. TSP1S93D Mutant Shows Enhanced Binding with Integrin β1

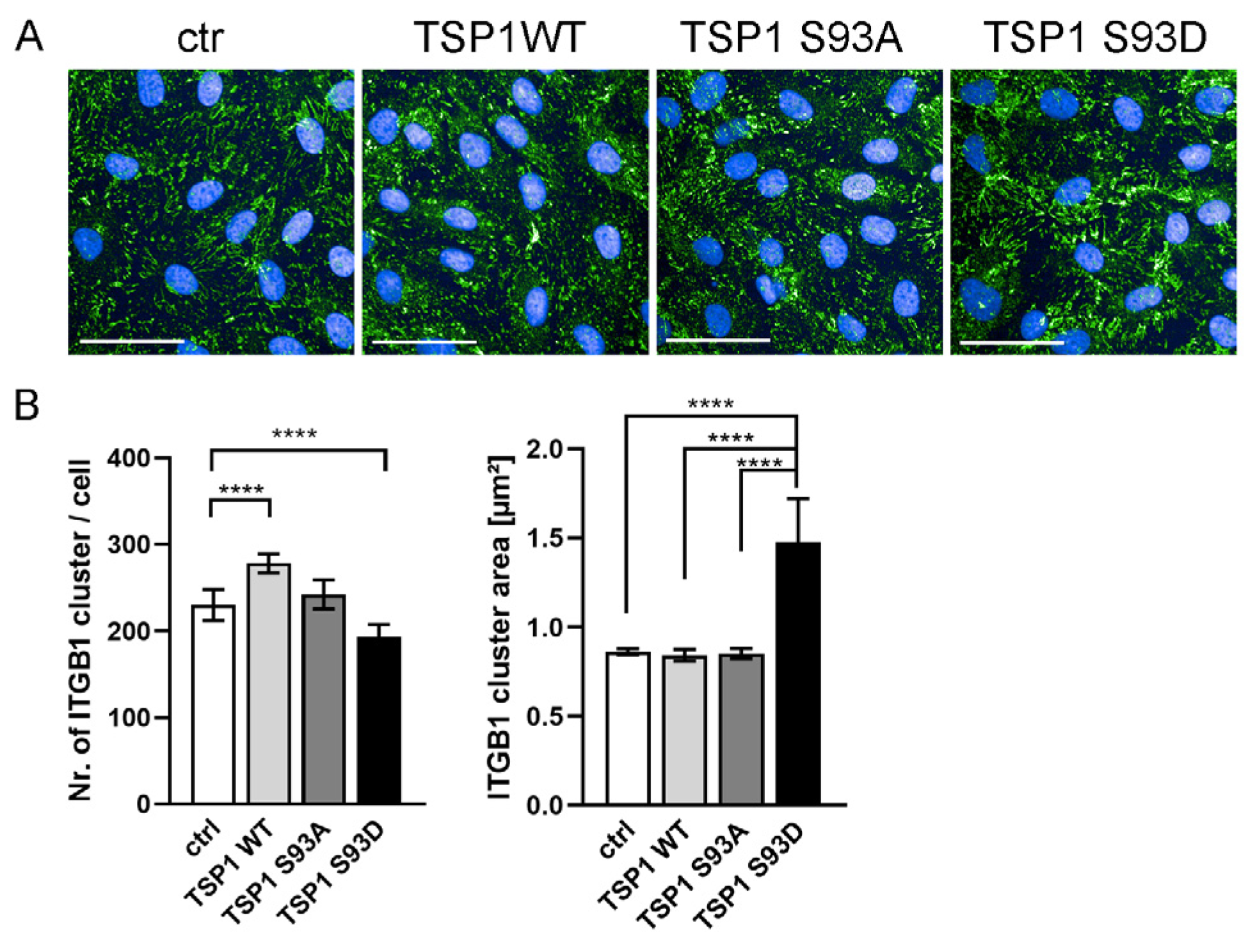

3.4. TSP1S93D Alters ITGB1 Clustering

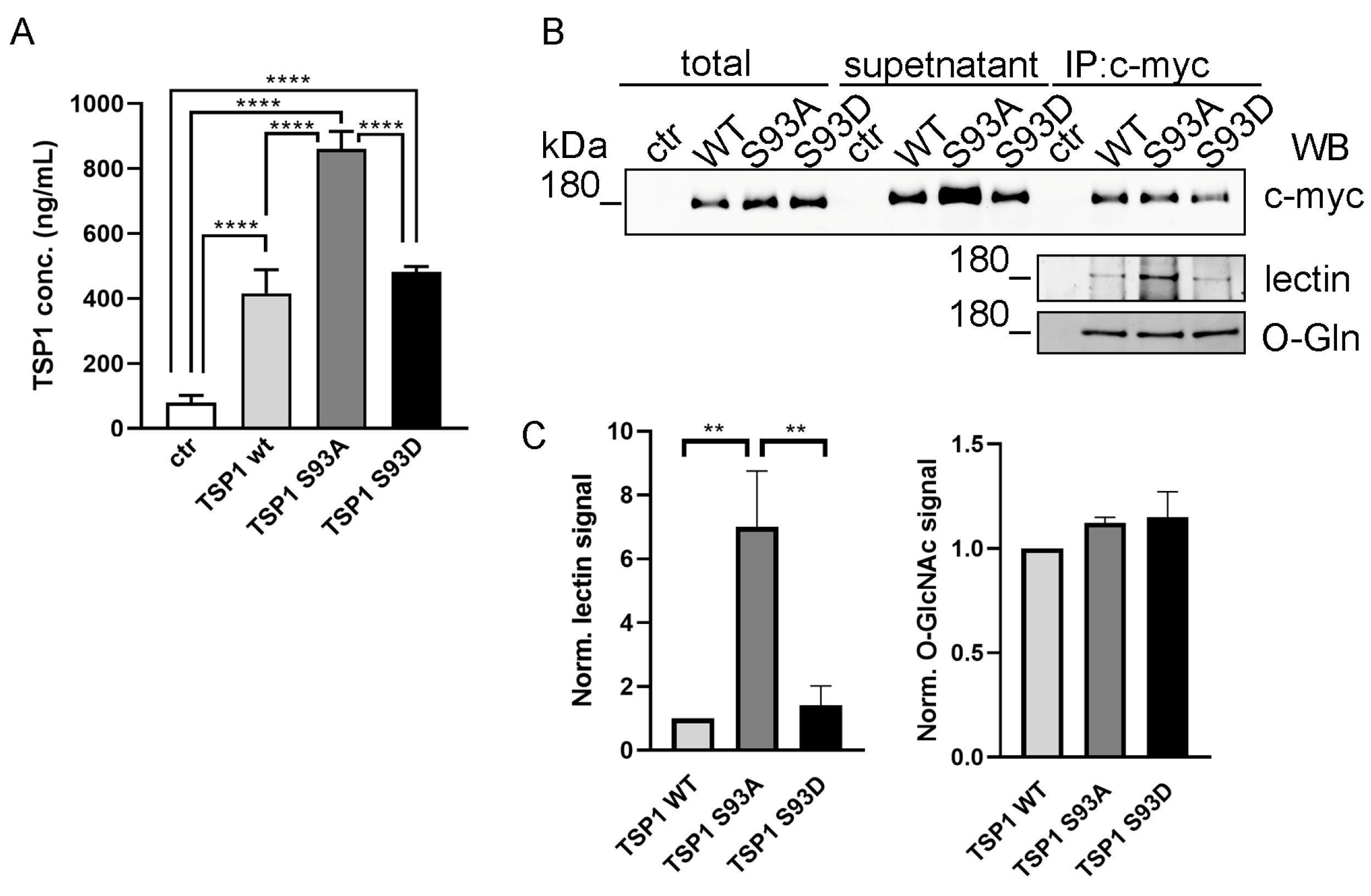

3.5. Ser93 Side Chain Phospho-Modification Affects TSP1 Secretion

3.6. TSP1S93D Enhances SMC Proliferation and Migration

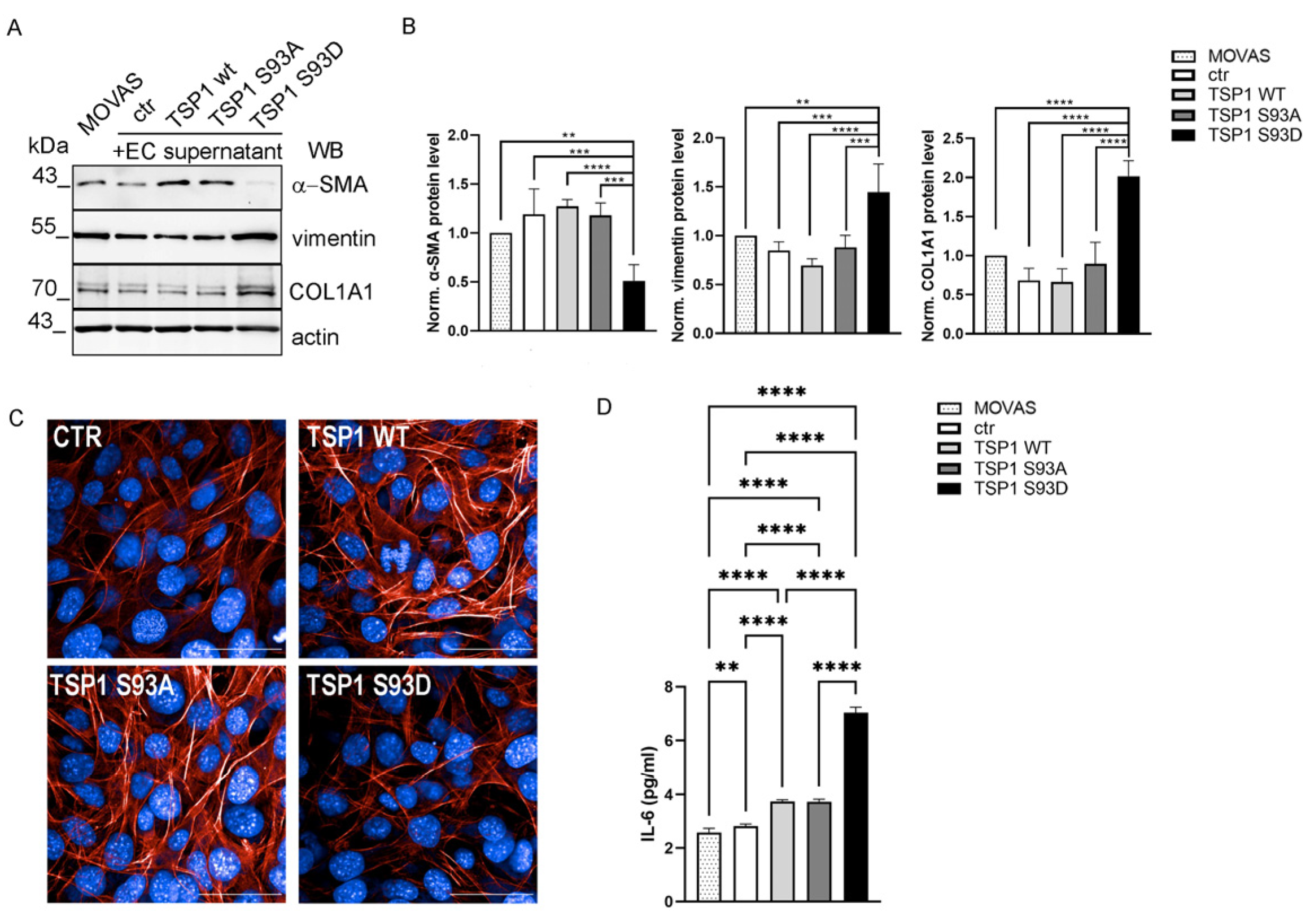

3.7. TSP1S93D Induces Phenotype Change in SMC from Contractile to Synthetic Type

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

References

- Michiels, C. Endothelial cell functions. J. Cell Physiol. 2003, 196, 430–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aird, W.C. Endothelial cell heterogeneity. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2012, 2, a006429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lamalice, L.; Le Boeuf, F.; Huot, J. Endothelial cell migration during angiogenesis. Circ. Res. 2007, 100, 782–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Korff, T.; Kimmina, S.; Martiny-Baron, G.; Augustin, H.G. Blood vessel maturation in a 3-dimensional spheroidal coculture model: Direct contact with smooth muscle cells regulates endothelial cell quiescence and abrogates VEGF responsiveness. Faseb J. 2001, 15, 447–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heydarkhan-Hagvall, S.; Helenius, G.; Johansson, B.R.; Li, J.Y.; Mattsson, E.; Risberg, B. Co-culture of endothelial cells and smooth muscle cells affects gene expression of angiogenic factors. J. Cell Biochem. 2003, 89, 1250–1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taraboletti, G.; Roberts, D.; Liotta, L.A.; Giavazzi, R. Platelet thrombospondin modulates endothelial cell adhesion, motility, and growth: A potential angiogenesis regulatory factor. J. Cell Biol. 1990, 111, 765–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, K.; Lawler, J. The interaction of Thrombospondins with extracellular matrix proteins. J. Cell Commun. Signal 2009, 3, 177–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, J.C.; Lawler, J. The thrombospondins. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2011, 3, a009712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Herndon, M.E.; Lawler, J. The cell biology of thrombospondin-1. Matrix Biol. 2000, 19, 597–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, J.C.; Tucker, R.P. The thrombospondin type 1 repeat (TSR) superfamily: Diverse proteins with related roles in neuronal development. Dev. Dyn. 2000, 218, 280–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morandi, V.; Petrik, J.; Lawler, J. Endothelial Cell Behavior Is Determined by Receptor Clustering Induced by Thrombospondin-1. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9, 664696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iruela-Arispe, M.L.; Lombardo, M.; Krutzsch, H.C.; Lawler, J.; Roberts, D.D. Inhibition of angiogenesis by thrombospondin-1 is mediated by 2 independent regions within the type 1 repeats. Circulation 1999, 100, 1423–1431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kazerounian, S.; Lawler, J. Integration of pro- and anti-angiogenic signals by endothelial cells. J. Cell Commun. Signal 2018, 12, 171–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Yang, H.; Song, Y.S.; Sorenson, C.M.; Sheibani, N. Thrombospondin-1 in vascular development, vascular function, and vascular disease. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2024, 155, 32–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kale, A.; Rogers, N.M.; Ghimire, K. Thrombospondin-1 CD47 Signalling: From Mechanisms to Medicine. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 4062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Isenberg, J.S.; Frazier, W.A.; Roberts, D.D. Thrombospondin-1: A physiological regulator of nitric oxide signaling. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 2008, 65, 728–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Isenberg, J.S.; Jia, Y.; Fukuyama, J.; Switzer, C.H.; Wink, D.A.; Roberts, D.D. Thrombospondin-1 inhibits nitric oxide signaling via CD36 by inhibiting myristic acid uptake. J. Biol. Chem. 2007, 282, 15404–15415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, C.J.; Schindler, F.; Ventura, A.M.; Morais, M.S.; Arai, R.J.; Debbas, V.; Stern, A.; Monteiro, H.P. Nitric oxide and cGMP activate the Ras-MAP kinase pathway-stimulating protein tyrosine phosphorylation in rabbit aortic endothelial cells. Free. Radic. Biol. Med. 2003, 35, 381–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isenberg, J.S.; Ridnour, L.A.; Perruccio, E.M.; Espey, M.G.; Wink, D.A.; Roberts, D.D. Thrombospondin-1 inhibits endothelial cell responses to nitric oxide in a cGMP-dependent manner. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2005, 102, 13141–13146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, B.; Cork, S.M.; Sandberg, E.M.; Devi, N.S.; Zhang, Z.; Klenotic, P.A.; Febbraio, M.; Shim, H.; Mao, H.; Tucker-Burden, C.; et al. Vasculostatin inhibits intracranial glioma growth and negatively regulates in vivo angiogenesis through a CD36-dependent mechanism. Cancer Res. 2009, 69, 1212–1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Son, N.H.; Basu, D.; Samovski, D.; Pietka, T.A.; Peche, V.S.; Willecke, F.; Fang, X.; Yu, S.Q.; Scerbo, D.; Chang, H.R.; et al. Endothelial cell CD36 optimizes tissue fatty acid uptake. J. Clin. Investig. 2018, 128, 4329–4342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jimenez, B.; Volpert, O.V.; Crawford, S.E.; Febbraio, M.; Silverstein, R.L.; Bouck, N. Signals leading to apoptosis-dependent inhibition of neovascularization by thrombospondin-1. Nat. Med. 2000, 6, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dawson, D.W.; Pearce, S.F.; Zhong, R.; Silverstein, R.L.; Frazier, W.A.; Bouck, N.P. CD36 mediates the In vitro inhibitory effects of thrombospondin-1 on endothelial cells. J. Cell Biol. 1997, 138, 707–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, B.; Yee, K.O.; Lawler, J.; Khosravi-Far, R. Regulation of tumor angiogenesis by thrombospondin-1. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2006, 1765, 178–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pal, S.K.; Nguyen, C.T.; Morita, K.I.; Miki, Y.; Kayamori, K.; Yamaguchi, A.; Sakamoto, K. THBS1 is induced by TGFB1 in the cancer stroma and promotes invasion of oral squamous cell carcinoma. J. Oral. Pathol. Med. 2016, 45, 730–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radziwon-Balicka, A.; Santos-Martinez, M.J.; Corbalan, J.J.; O’Sullivan, S.; Treumann, A.; Gilmer, J.F.; Radomski, M.W.; Medina, C. Mechanisms of platelet-stimulated colon cancer invasion: Role of clusterin and thrombospondin 1 in regulation of the P38MAPK-MMP-9 pathway. Carcinogenesis 2014, 35, 324–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orr, A.W.; Pallero, M.A.; Murphy-Ullrich, J.E. Thrombospondin stimulates focal adhesion disassembly through Gi- and phosphoinositide 3-kinase-dependent ERK activation. J. Biol. Chem. 2002, 277, 20453–20460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orr, A.W.; Pallero, M.A.; Xiong, W.C.; Murphy-Ullrich, J.E. Thrombospondin induces RhoA inactivation through FAK-dependent signaling to stimulate focal adhesion disassembly. J. Biol. Chem. 2004, 279, 48983–48992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, C.; Wen, J.; Gong, L.; Chen, X.; Wang, J.; Hu, F.; Zhou, Q.; Liang, J.; Wei, L.; Shen, Y.; et al. Thrombospondin-1 promotes cell migration, invasion and lung metastasis of osteosarcoma through FAK dependent pathway. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 75881–75892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosher, D.F.; Doyle, M.J.; Jaffe, E.A. Synthesis and secretion of thrombospondin by cultured human endothelial cells. J. Cell Biol. 1982, 93, 343–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calzada, M.J.; Kuznetsova, S.A.; Sipes, J.M.; Rodrigues, R.G.; Cashel, J.A.; Annis, D.S.; Mosher, D.F.; Roberts, D.D. Calcium indirectly regulates immunochemical reactivity and functional activities of the N-domain of thrombospondin-1. Matrix Biol. 2008, 27, 339–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Good, D.J.; Polverini, P.J.; Rastinejad, F.; Le Beau, M.M.; Lemons, R.S.; Frazier, W.A.; Bouck, N.P. A tumor suppressor-dependent inhibitor of angiogenesis is immunologically and functionally indistinguishable from a fragment of thrombospondin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1990, 87, 6624–6628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yabkowitz, R.; Mansfield, P.J.; Ryan, U.S.; Suchard, S.J. Thrombospondin mediates migration and potentiates platelet-derived growth factor-dependent migration of calf pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells. J. Cell Physiol. 1993, 157, 24–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Majack, R.A.; Goodman, L.V.; Dixit, V.M. Cell surface thrombospondin is functionally essential for vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation. J. Cell Biol. 1988, 106, 415–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moura, R.; Tjwa, M.; Vandervoort, P.; Cludts, K.; Hoylaerts, M.F. Thrombospondin-1 activates medial smooth muscle cells and triggers neointima formation upon mouse carotid artery ligation. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2007, 27, 2163–2169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ganguly, R.; Khanal, S.; Mathias, A.; Gupta, S.; Lallo, J.; Sahu, S.; Ohanyan, V.; Patel, A.; Storm, K.; Datta, S.; et al. TSP-1 (Thrombospondin-1) Deficiency Protects ApoE(-/-) Mice Against Leptin-Induced Atherosclerosis. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2021, 41, e112–e127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suades, R.; Padro, T.; Alonso, R.; Mata, P.; Badimon, L. High levels of TSP1+/CD142+ platelet-derived microparticles characterise young patients with high cardiovascular risk and subclinical atherosclerosis. Thromb. Haemost. 2015, 114, 1310–1321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akimov, V.; Barrio-Hernandez, I.; Hansen, S.V.F.; Hallenborg, P.; Pedersen, A.K.; Bekker-Jensen, D.B.; Puglia, M.; Christensen, S.D.K.; Vanselow, J.T.; Nielsen, M.M.; et al. UbiSite approach for comprehensive mapping of lysine and N-terminal ubiquitination sites. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2018, 25, 631–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dieudé, M.; Bell, C.; Turgeon, J.; Beillevaire, D.; Pomerleau, L.; Yang, B.; Hamelin, K.; Qi, S.; Pallet, N.; Béland, C.; et al. The 20S proteasome core, active within apoptotic exosome-like vesicles, induces autoantibody production and accelerates rejection. Sci. Transl. Med. 2015, 7, 318ra200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thalwieser, Z.; Fonodi, M.; Kiraly, N.; Csortos, C.; Boratko, A. PP2A Affects Angiogenesis via Its Interaction with a Novel Phosphorylation Site of TSP1. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 1844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tolsma, S.S.; Volpert, O.V.; Good, D.J.; Frazier, W.A.; Polverini, P.J.; Bouck, N. Peptides derived from two separate domains of the matrix protein thrombospondin-1 have anti-angiogenic activity. J. Cell Biol. 1993, 122, 497–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, M.S.; Mendelson, D.; Carr, R.; Knight, R.A.; Humerickhouse, R.A.; Iannone, M.; Stopeck, A.T. A phase 1 trial of 2 dose schedules of ABT-510, an antiangiogenic, thrombospondin-1-mimetic peptide, in patients with advanced cancer. Cancer 2008, 113, 3420–3429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boratko, A.; Gergely, P.; Csortos, C. RACK1 is involved in endothelial barrier regulation via its two novel interacting partners. Cell Commun. Signal 2013, 11, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Király, N.; Thalwieser, Z.; Fonódi, M.; Csortos, C.; Boratkó, A. Dephosphorylation of annexin A2 by protein phosphatase 1 regulates endothelial cell barrier. IUBMB Life 2021, 73, 1257–1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keese, C.R.; Wegener, J.; Walker, S.R.; Giaever, I. Electrical wound-healing assay for cells in vitro. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2004, 101, 1554–1559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsu, C.-C.; Tsai, W.-C.; Chen, C.P.-C.; Lu, Y.-M.; Wang, J.-S. Effects of negative pressures on epithelial tight junctions and migration in wound healing. Am. J. Physiol.-Cell Physiol. 2010, 299, C528–C534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thalwieser, Z.; Kiraly, N.; Fonodi, M.; Csortos, C.; Boratko, A. Protein phosphatase 2A-mediated flotillin-1 dephosphorylation up-regulates endothelial cell migration and angiogenesis regulation. J. Biol. Chem. 2019, 294, 20196–20206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barclay, J.L.; Keshvari, S.; Whitehead, J.P.; Inder, W.J. Development of an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for thrombospondin-1 and comparison of human plasma and serum concentrations. Ann. Clin. Biochem. 2016, 53, 606–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regdon, Z.; Demény, M.; Kovács, K.; Hajnády, Z.; Nagy, M.; Edina, B.; Kiss, A.; Hegedűs, C.; Virág, L. High-content screening identifies inhibitors of oxidative stress-induced parthanatos: Cytoprotective and anti-inflammatory effects of ciclopirox. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2021, 178, 1095–1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofsteenge, J.; Huwiler, K.G.; Macek, B.; Hess, D.; Lawler, J.; Mosher, D.F.; Peter-Katalinic, J. C-mannosylation and O-fucosylation of the thrombospondin type 1 module. J. Biol. Chem. 2001, 276, 6485–6498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zielinska, D.F.; Gnad, F.; Wisniewski, J.R.; Mann, M. Precision mapping of an in vivo N-glycoproteome reveals rigid topological and sequence constraints. Cell 2010, 141, 897–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Li, M.; Yin, L.; Fu, G.; Liu, Z. Role of thrombospondin-1 and thrombospondin-2 in cardiovascular diseases (Review). Int. J. Mol. Med. 2020, 45, 1275–1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackenzie, N.C.; Zhu, D.; Longley, L.; Patterson, C.S.; Kommareddy, S.; MacRae, V.E. MOVAS-1 cell line: A new in vitro model of vascular calcification. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2011, 27, 663–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esobi, I.C.; Barksdale, C.; Heard-Tate, C.; Reigers Powell, R.; Bruce, T.F.; Stamatikos, A. MOVAS Cells: A Versatile Cell Line for Studying Vascular Smooth Muscle Cell Cholesterol Metabolism. Lipids 2021, 56, 413–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, Z.S.; Raya-Sandino, A.; Miranda, J.; Fan, S.; Brazil, J.C.; Quiros, M.; Garcia-Hernandez, V.; Liu, Q.; Kim, C.H.; Hankenson, K.D.; et al. Critical role of thrombospondin-1 in promoting intestinal mucosal wound repair. JCI Insight 2024, 9, e180608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meijles, D.N.; Sahoo, S.; Al Ghouleh, I.; Amaral, J.H.; Bienes-Martinez, R.; Knupp, H.E.; Attaran, S.; Sembrat, J.C.; Nouraie, S.M.; Rojas, M.M.; et al. The matricellular protein TSP1 promotes human and mouse endothelial cell senescence through CD47 and Nox1. Sci. Signal 2017, 10, eaaj1784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Chen, X.; Wang, J.K.; Li, Y.; Cui, S.J.; Wang, Z.; Luo, T. Phenotypic Switching of Atherosclerotic Smooth Muscle Cells is Regulated by Activated PARP1-Dependent TET1 Expression. J. Atheroscler. Thromb. 2021, 28, 716–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, R.; Wang, H.; Cheng, X.; Fan, K.; Gao, T.; Qi, X.; Gao, S.; Zheng, G.; Dong, H. High estrogen induces trans-differentiation of vascular smooth muscle cells to a macrophage-like phenotype resulting in aortic inflammation via inhibiting VHL/HIF1a/KLF4 axis. Aging 2024, 16, 9876–9898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alexander, M.R.; Owens, G.K. Epigenetic control of smooth muscle cell differentiation and phenotypic switching in vascular development and disease. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2012, 74, 13–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Chen, S.-Y. Transforming growth factor-β and smooth muscle differentiation. World J. Biol. Chem. 2012, 3, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owens, G.K.; Kumar, M.S.; Wamhoff, B.R. Molecular regulation of vascular smooth muscle cell differentiation in development and disease. Physiol. Rev. 2004, 84, 767–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ailawadi, G.; Moehle, C.W.; Pei, H.; Walton, S.P.; Yang, Z.; Kron, I.L.; Lau, C.L.; Owens, G.K. Smooth muscle phenotypic modulation is an early event in aortic aneurysms. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2009, 138, 1392–1399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, M.C.; Littlewood, T.D.; Figg, N.; Maguire, J.J.; Davenport, A.P.; Goddard, M.; Bennett, M.R. Chronic apoptosis of vascular smooth muscle cells accelerates atherosclerosis and promotes calcification and medial degeneration. Circ. Res. 2008, 102, 1529–1538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rensen, S.S.; Doevendans, P.A.; van Eys, G.J. Regulation and characteristics of vascular smooth muscle cell phenotypic diversity. Neth. Heart J. 2007, 15, 100–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, H.; Xue, C.; Auerbach, B.J.; Fan, J.; Bashore, A.C.; Cui, J.; Yang, D.Y.; Trignano, S.B.; Liu, W.; Shi, J. Single-cell genomics reveals a novel cell state during smooth muscle cell phenotypic switching and potential therapeutic targets for atherosclerosis in mouse and human. Circulation 2020, 142, 2060–2075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alencar, G.F.; Owsiany, K.M.; Karnewar, S.; Sukhavasi, K.; Mocci, G.; Nguyen, A.T.; Williams, C.M.; Shamsuzzaman, S.; Mokry, M.; Henderson, C.A. Stem cell pluripotency genes Klf4 and Oct4 regulate complex SMC phenotypic changes critical in late-stage atherosclerotic lesion pathogenesis. Circulation 2020, 142, 2045–2059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, J.; Rolfe, B.E.; Campbell, J.H.; Campbell, G.R. Changes in three-dimensional architecture of microfilaments in cultured vascular smooth muscle cells during phenotypic modulation. Tissue Cell 1998, 30, 324–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rusk, A.; McKeegan, E.; Haviv, F.; Majest, S.; Henkin, J.; Khanna, C. Preclinical evaluation of antiangiogenic thrombospondin-1 peptide mimetics, ABT-526 and ABT-510, in companion dogs with naturally occurring cancers. Clin. Cancer Res. 2006, 12, 7444–7455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafiee, A.; Penn, J.S.; Krutzsch, H.C.; Inman, J.K.; Roberts, D.D.; Blake, D.A. Inhibition of retinal angiogenesis by peptides derived from thrombospondin-1. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2000, 41, 2378–2388. [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura, D.S.; Edwards, A.K.; Virani, S.; Thomas, R.; Tayade, C. Thrombospondin-1 mimetic peptide ABT-898 affects neovascularization and survival of human endometriotic lesions in a mouse model. Am. J. Pathol. 2012, 181, 570–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandrasekaran, L.; He, C.-Z.; Al-Barazi, H.; Krutzsch, H.C.; Iruela-Arispe, M.L.; Roberts, D.D. Cell contact–dependent activation of α3β1 integrin modulates endothelial cell responses to thrombospondin-1. Mol. Biol. Cell 2000, 11, 2885–2900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Short, S.M.; Derrien, A.; Narsimhan, R.P.; Lawler, J.; Ingber, D.E.; Zetter, B.R. Inhibition of endothelial cell migration by thrombospondin-1 type-1 repeats is mediated by beta1 integrins. J. Cell Biol. 2005, 168, 643–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy-Ullrich, J.E. Thrombospondin-1 Signaling Through the Calreticulin/LDL Receptor Related Protein 1 Axis: Functions and Possible Roles in Glaucoma. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2022, 10, 898772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sipes, J.M.; Krutzsch, H.C.; Lawler, J.; Roberts, D.D. Cooperation between thrombospondin-1 type 1 repeat peptides and alpha(v)beta(3) integrin ligands to promote melanoma cell spreading and focal adhesion kinase phosphorylation. J. Biol. Chem. 1999, 274, 22755–22762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Guan, J.L. Focal adhesion kinase and its signaling pathways in cell migration and angiogenesis. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2011, 63, 610–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deakin, N.O.; Turner, C.E. Paxillin comes of age. J. Cell Sci. 2008, 121, 2435–2444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas, J.W.; Cooley, M.A.; Broome, J.M.; Salgia, R.; Griffin, J.D.; Lombardo, C.R.; Schaller, M.D. The role of focal adhesion kinase binding in the regulation of tyrosine phosphorylation of paxillin. J. Biol. Chem. 1999, 274, 36684–36692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petit, V.; Boyer, B.; Lentz, D.; Turner, C.E.; Thiery, J.P.; Vallés, A.M. Phosphorylation of tyrosine residues 31 and 118 on paxillin regulates cell migration through an association with CRK in NBT-II cells. J. Cell Biol. 2000, 148, 957–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinon, P.; Pärssinen, J.; Vazquez, P.; Bachmann, M.; Rahikainen, R.; Jacquier, M.-C.; Azizi, L.; Määttä, J.A.; Bastmeyer, M.; Hytönen, V.P. Talin-bound NPLY motif recruits integrin-signaling adapters to regulate cell spreading and mechanosensing. J. Cell Biol. 2014, 205, 265–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soto-Ribeiro, M.; Kastberger, B.; Bachmann, M.; Azizi, L.; Fouad, K.; Jacquier, M.-C.; Boettiger, D.; Bouvard, D.; Bastmeyer, M.; Hytönen, V.P. β1D integrin splice variant stabilizes integrin dynamics and reduces integrin signaling by limiting paxillin recruitment. J. Cell Sci. 2019, 132, jcs224493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calzada, M.J.; Zhou, L.; Sipes, J.M.; Zhang, J.; Krutzsch, H.C.; Iruela-Arispe, M.L.; Annis, D.S.; Mosher, D.F.; Roberts, D.D. Alpha4beta1 integrin mediates selective endothelial cell responses to thrombospondins 1 and 2 in vitro and modulates angiogenesis in vivo. Circ. Res. 2004, 94, 462–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steentoft, C.; Vakhrushev, S.Y.; Joshi, H.J.; Kong, Y.; Vester-Christensen, M.B.; Schjoldager, K.T.; Lavrsen, K.; Dabelsteen, S.; Pedersen, N.B.; Marcos-Silva, L.; et al. Precision mapping of the human O-GalNAc glycoproteome through SimpleCell technology. EMBO J. 2013, 32, 1478–1488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasudevan, D.; Takeuchi, H.; Johar, S.S.; Majerus, E.; Haltiwanger, R.S. Peters plus syndrome mutations disrupt a noncanonical ER quality-control mechanism. Curr. Biol. 2015, 25, 286–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoffmann, B.R.; Liu, Y.; Mosher, D.F. Modification of EGF-like module 1 of thrombospondin-1, an animal extracellular protein, by O-linked N-acetylglucosamine. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e32762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Herndon, M.E.; Ranganathan, S.; Godyna, S.; Lawler, J.; Argraves, W.S.; Liau, G. Internalization but not binding of thrombospondin-1 to low density lipoprotein receptor-related protein-1 requires heparan sulfate proteoglycans. J. Cell Biochem. 2004, 91, 766–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy-Ullrich, J.E.; Gurusiddappa, S.; Frazier, W.A.; Hook, M. Heparin-binding peptides from thrombospondins 1 and 2 contain focal adhesion-labilizing activity. J. Biol. Chem. 1993, 268, 26784–26789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, K.; Duquette, M.; Liu, J.H.; Zhang, R.; Joachimiak, A.; Wang, J.H.; Lawler, J. The structures of the thrombospondin-1 N-terminal domain and its complex with a synthetic pentameric heparin. Structure 2006, 14, 33–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gittenberger-de Groot, A.C.; DeRuiter, M.C.; Bergwerff, M.; Poelmann, R.E. Smooth muscle cell origin and its relation to heterogeneity in development and disease. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 1999, 19, 1589–1594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Cai, Y.; Yang, F.; Yang, Y.; Cui, Z.; Shi, D.; Bai, R. Vascular smooth muscle cell phenotypic switching in atherosclerosis. Heliyon 2024, 10, e37727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Castresana, M.R.; Newman, W.H. Reactive oxygen and NF-κB in VEGF-induced migration of human vascular smooth muscle cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2001, 285, 669–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Newman, W.H.; Castresana, M.R.; Webb, J.G.; Wang, Z. Cyclic AMP inhibits production of interleukin-6 and migration in human vascular smooth muscle cells. J. Surg. Res. 2003, 109, 57–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Newman, W.H. Smooth muscle cell migration stimulated by interleukin 6 is associated with cytoskeletal reorganization. J. Surg. Res. 2003, 111, 261–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hojo, Y.; Ikeda, U.; Katsuki, T.; Mizuno, O.; Fukazawa, H.; Kurosaki, K.; Fujikawa, H.; Shimada, K. Interleukin 6 expression in coronary circulation after coronary angioplasty as a risk factor for restenosis. Heart 2000, 84, 83–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Insull, W. The Pathology of Atherosclerosis: Plaque Development and Plaque Responses to Medical Treatment. Am. J. Med. 2009, 122, S3–S14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoshida, T.; Kaestner, K.H.; Owens, G.K. Conditional deletion of Kruppel-like factor 4 delays downregulation of smooth muscle cell differentiation markers but accelerates neointimal formation following vascular injury. Circ. Res. 2008, 102, 1548–1557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, P.Y.; Qin, L.; Li, G.; Tellides, G.; Simons, M. Smooth muscle FGF/TGF β cross talk regulates atherosclerosis progression. EMBO Mol. Med. 2016, 8, 712–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Antibody | Dilution | Vendor (Cat#) |

|---|---|---|

| actin (20-33) | 1:1000 | Sigma (St. Louis, MO, USA) (A5060) |

| Akt1 (C73H10) | 1:1000 | Cell Signaling Technologies (Danvers, MA, USA) (2938S) |

| anti-mouse IgG HRP-linked | 1:5000 | Cell Signaling Technologies (Danvers, MA, USA) (#7076S) |

| anti-rabbit IgG HRP-linked | 1:5000 | Cell Signaling Technologies (Danvers, MA, USA) (#7074S) |

| c-myc (9E10) | 1:500 | Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA, USA) (13-2500) |

| COL1A1 (3G3) | 1:500 | Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Dallas, TX, USA) (sc-293182) |

| ERK 1/2 (C-9) | 1:1000 | Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Dallas, TX, USA) (sc-514302) |

| FAK (H-1) | 1:500 | Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Dallas, TX, USA) (sc-1688) |

| integrin β1 (A-4) | 1:1000 | Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Dallas, TX, USA) (sc-374429) |

| O-GlcNac (CTD110.6) | 1:1000 | Cell Signaling Technologies (Danvers, MA, USA) (9875S) |

| p38 alpha/beta MAPK (A-12) | 1:1000 | Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Dallas, TX, USA) (sc-7972) |

| p-Akt (S473) | 1:1000 | Cell Signaling Technologies (Danvers, MA, USA) (4060S) |

| paxillin (B-2) | 1:1000 | Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Dallas, TX, USA) (sc-365379) |

| p-ERK (E-4)(Tyr204/Tyr187) | 1:1000 | Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Dallas, TX, USA) (sc-7383) |

| p-FAK (Tyr397) | 1:1000 | Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Dallas, TX, USA) (sc-81493) |

| p-p38 MAPK (E-1) (Tyr182) | 1:1000 | Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Dallas, TX, USA) (sc-166182) |

| p-paxillin (A-5) | 1:1000 | Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Dallas, TX, USA) (sc-365020) |

| thrombospondin-1 (C-8) | 1:1000 | Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Dallas, TX, USA) (sc-393504) |

| vimentin (R28) | 1:1000 | Cell Signaling Technologies (Danvers, MA, USA) (3932S) |

| α-SMA | 1:1000 | R&D Systems Bio-techne (Minneapolis, MN, USA) (MAB1420) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Raya, A.; Bécsi, B.; Boratkó, A. Phosphomimetic Thrombospondin-1 Modulates Integrin β1-FAK Signaling and Vascular Cell Functions. Biomolecules 2026, 16, 84. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom16010084

Raya A, Bécsi B, Boratkó A. Phosphomimetic Thrombospondin-1 Modulates Integrin β1-FAK Signaling and Vascular Cell Functions. Biomolecules. 2026; 16(1):84. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom16010084

Chicago/Turabian StyleRaya, Assala, Bálint Bécsi, and Anita Boratkó. 2026. "Phosphomimetic Thrombospondin-1 Modulates Integrin β1-FAK Signaling and Vascular Cell Functions" Biomolecules 16, no. 1: 84. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom16010084

APA StyleRaya, A., Bécsi, B., & Boratkó, A. (2026). Phosphomimetic Thrombospondin-1 Modulates Integrin β1-FAK Signaling and Vascular Cell Functions. Biomolecules, 16(1), 84. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom16010084