Emerging Roles of Tubulin Isoforms and Their Post-Translational Modifications in Microtubule-Based Transport and Cellular Functions

Abstract

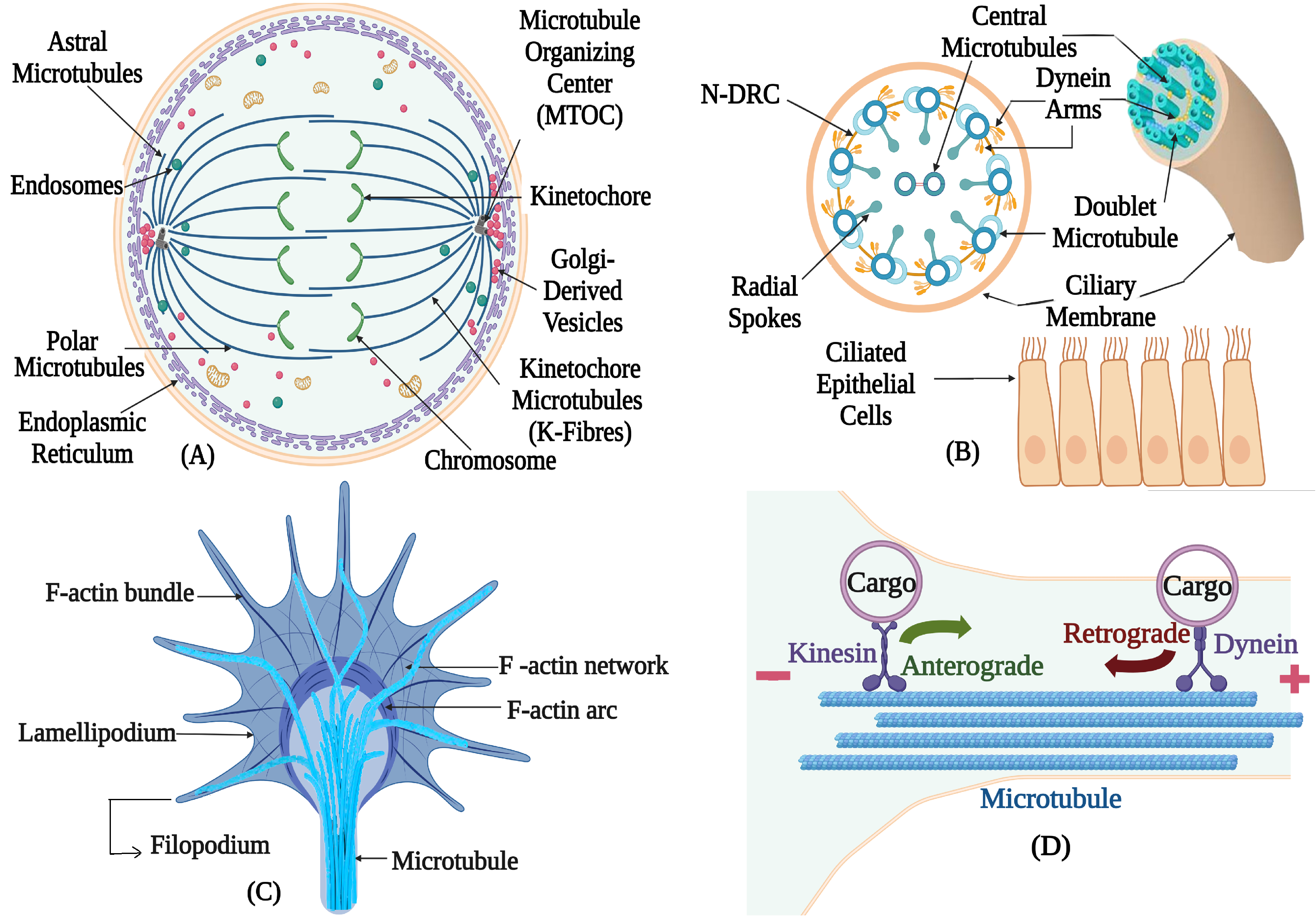

1. Introduction

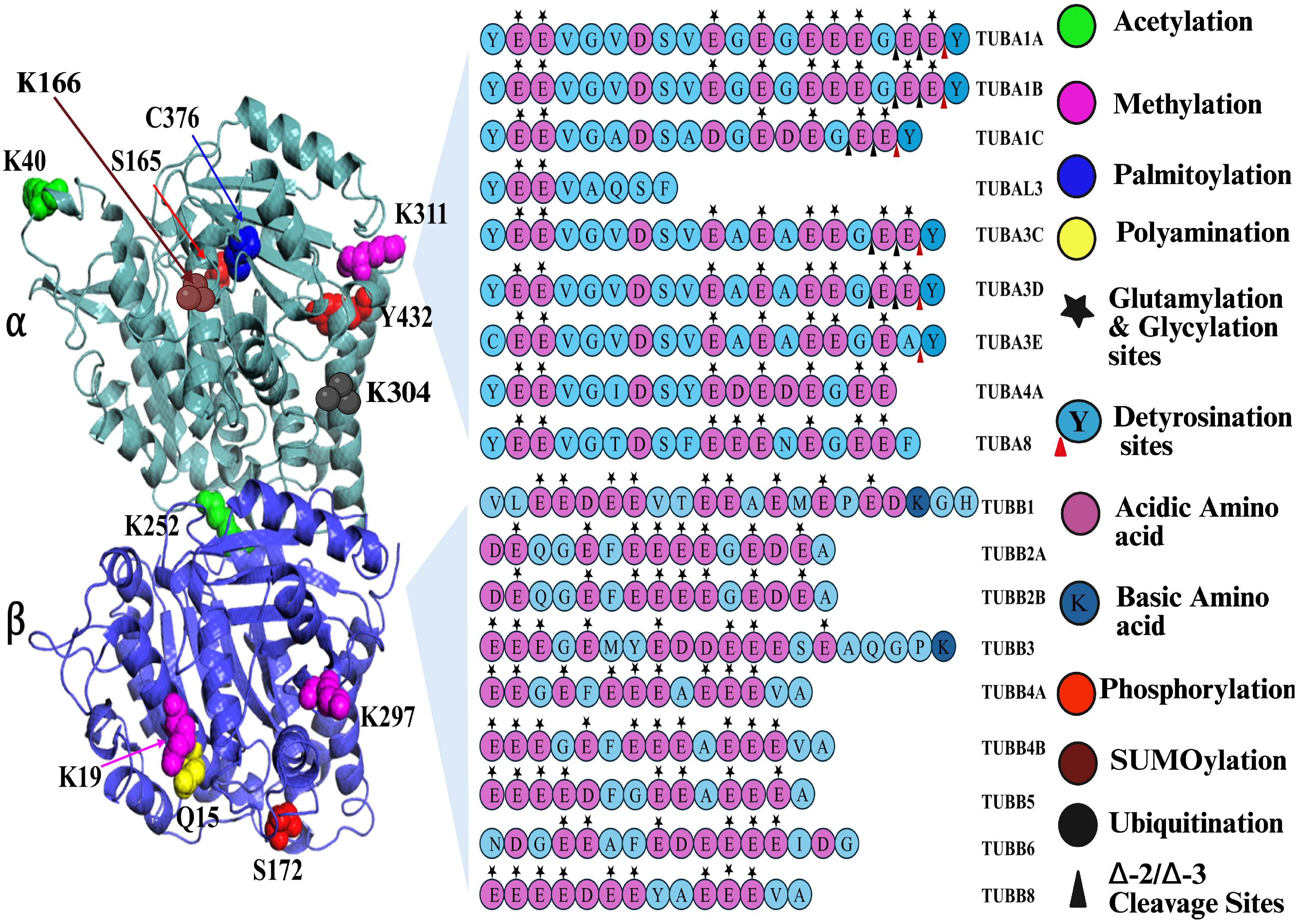

2. Tubulin Isotypes

Mutations of the Tubulin Isotypes

3. Tubulin Isoforms

4. Post-Translational Modifications of Tubulin

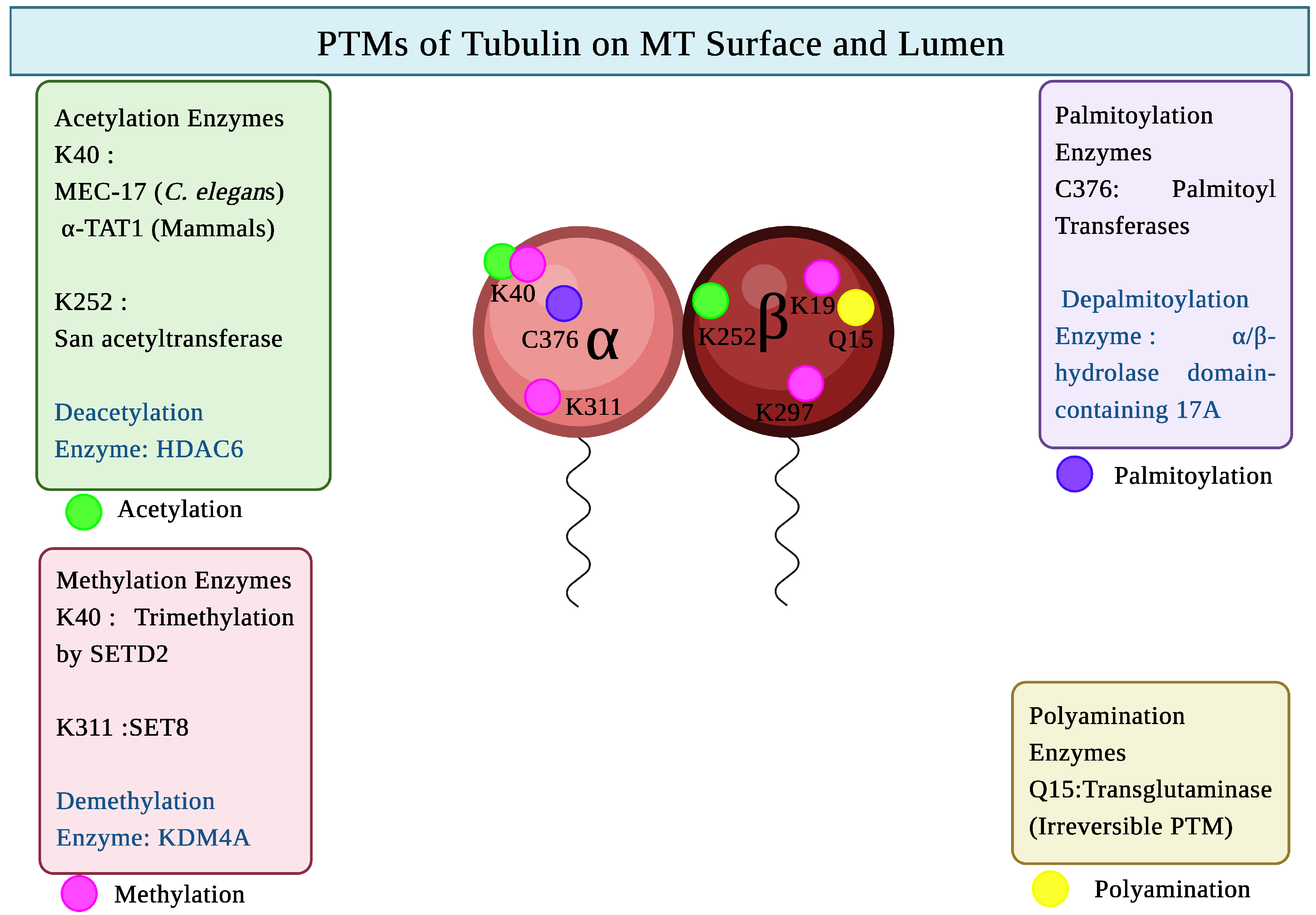

4.1. PTMs of Tubulin in MT Lumen and on Surface

4.1.1. Acetylation of Tubulin

4.1.2. Methylation of Tubulin

4.1.3. Palmitoylation of Tubulin

4.1.4. Polyamination of Tubulin

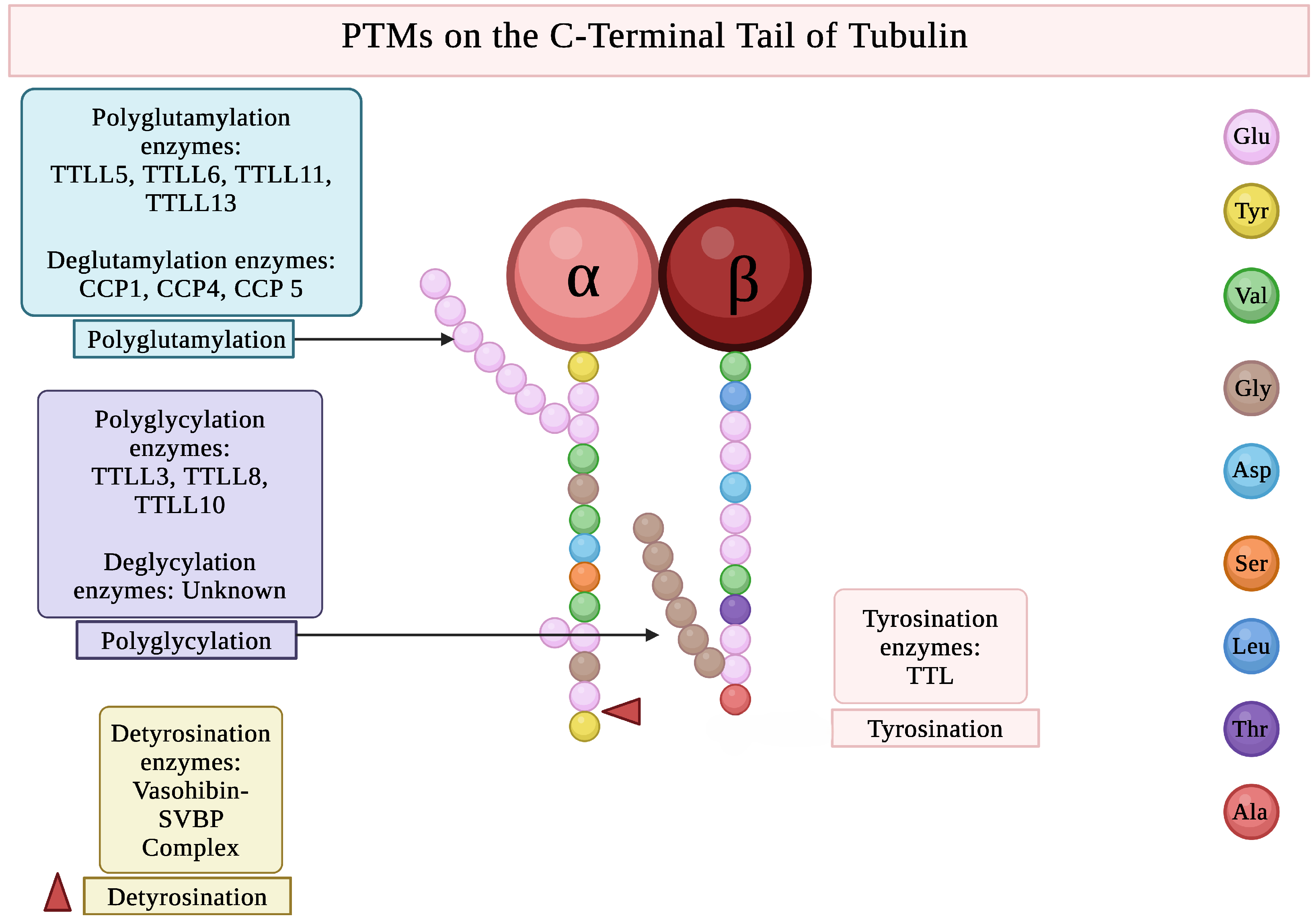

4.2. PTMs on the C-Terminal Tail of Tubulin

4.2.1. Glutamylation of Tubulin

4.2.2. Glycylation of Tubulin

4.2.3. Tyrosination of Tubulin

4.3. PTMs Providing Regulatory Tags on Tubulin

4.3.1. Phosphorylation of Tubulin

4.3.2. SUMOylation of Tubulin

4.3.3. Ubiquitination of Tubulin

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MT | Microtubule |

| GTP | Guanosine Triphosphate |

| CTT | Carboxy Terminal Tail |

| PTM | Post Translational Modification |

| MAP | Microtubule-Associated Protein |

| TTL | Tubulin Tyrosine Ligase |

| TTLL | Tubulin Tyrosine Ligase-Like |

| CCP | Cytosolic Carboxy Peptidase |

| IFT | Intraflagellar transport |

References

- Avila, J. Microtubule functions. Life Sci. 1992, 50, 327–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nogales, E. Structural Insights into Microtubule Function. Annu. Rev. Biophys. 2001, 30, 397–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gudimchuk, N.B.; McIntosh, J.R. Regulation of microtubule dynamics, mechanics and function through the growing tip. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2021, 22, 777–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Peng, Y.; Tao, X.; Ding, X.; Li, R.; Jiang, Y.; Zuo, W. Microtubule Organization Is Essential for Maintaining Cellular Morphology and Function. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2022, 2022, 1623181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pablo, P.D.; Schaap, I.; Schmidt, C. Observation of microtubules with scanning force microscopy in liquid. Nanotechnology 2003, 14, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cueva, J.G.; Hsin, J.; Huang, K.C.; Goodman, M.B. Posttranslational acetylation of α-tubulin constrains protofilament number in native microtubules. Curr. Biol. 2012, 22, 1066–1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Satir, P.; Christensen, S.T. Overview of structure and function of mammalian cilia. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2007, 69, 377–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoops, H.J.; Witman, G.B. Outer Doublet Related to Beat Heterogeneity Reveals Structural Polarity Direction in Chlamydomonas Flagella. J. Cell Biol. 1983, 97, 902–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Findeisen, P.; Mühlhausen, S.; Dempewolf, S.; Hertzog, J.; Zietlow, A.; Carlomagno, T.; Kollmar, M. Six Subgroups and Extensive Recent Duplications Characterize the Evolution of the Eukaryotic Tubulin Protein Family. Genome Biol. Evol. 2014, 6, 2274–2288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turk, E.; Wills, A.A.; Kwon, T.; Sedzinski, J.; Wallingford, J.B.; Stearns, T. ζ-tubulin is a member of a conserved tubulin module and is a component of the centriolar basal foot in multiciliated cells. Curr. Biol. 2015, 25, 2177–2183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stearns, T.; Evans, L.; Kirschner, M. γ-Tubulin is a highly conserved component of the centrosome. Cell 1991, 65, 825–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stathatos, G.G.; Dunleavy, J.E.; Zenker, J.; O’Bryan, M.K. Delta and epsilon tubulin in mammalian development. Trends Cell Biol. 2021, 31, 774–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moore, J.; Luduena, R.; Tuszynski, J.A. Editorial: The isotypes of α, β and γ tubulin: From evolutionary origins to roles in metazoan development and ligand binding differences. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2023, 11, 1176739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luchko, T.; Torin Huzil, J.; Stepanova, M.; Tuszynski, J. Conformational Analysis of the Carboxy-Terminal Tails of Human β-Tubulin Isotypes. Biophys. J. 2008, 94, 1971–1982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walczak, C.E. Microtubule dynamics and tubulin interacting proteins. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2000, 12, 52–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joe, P.A.; Banerjee, A.; Ludueña, R.F. Roles of β-Tubulin Residues Ala428 and Thr429 in Microtubule Formation in Vivo. J. Biol. Chem. 2009, 284, 4283–4291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, A.L.; Teo, W.S.; Brayford, S.; Moorthi, U.K.; Arumugam, S.; Ferguson, C.; Parton, R.G.; McCarroll, J.A.; Kavallaris, M. βIII-tubulin structural domains regulate mitochondrial network architecture in an isotype-specific manner. Cells 2022, 11, 776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gasic, I. Regulation of Tubulin Gene Expression: From Isotype Identity to Functional Specialization. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2022, 10, 898076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rostovtseva, T.K.; Gurnev, P.A.; Hoogerheide, D.P.; Rovini, A.; Sirajuddin, M.; Bezrukov, S.M. Sequence diversity of tubulin isotypes in regulation of the mitochondrial voltage-dependent anion channel. J. Biol. Chem. 2018, 293, 10949–10962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khodiyar, V.K.; Maltais, L.J.; Sneddon, K.M.; Smith, J.R.; Shimoyama, M.; Cabral, F.; Dumontet, C.; Dutcher, S.K.; Harvey, R.J.; Lafanechère, L.; et al. A revised nomenclature for the human and rodent α-tubulin gene family. Genomics 2007, 90, 285–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maliekal, T.T.; Dharmapal, D.; Sengupta, S. Tubulin Isotypes: Emerging Roles in Defining Cancer Stem Cell Niche. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 876278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, X.; Dou, Y.; Huang, G.; Sun, M.; Lu, S.; Chen, D. α-Tubulin Regulates the Fate of Germline Stem Cells in Drosophila Testis. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 10644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, M.; Morsci, N.; Nguyen, K.C.; Rizvi, A.; Rongo, C.; Hall, D.H.; Barr, M.M. Cell-Specific α-Tubulin Isotype Regulates Ciliary Microtubule Ultrastructure, Intraflagellar Transport, and Extracellular Vesicle Biology. Curr. Biol. 2017, 27, 968–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurd, D.D. Tubulins in C. elegans. In WormBook; Oxford Academic: Oxford, UK, 2018; pp. 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bera, A.; Gupta, M.L. Microtubules in Microorganisms: How Tubulin Isotypes Contribute to Diverse Cytoskeletal Functions. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2022, 10, 913809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ross, I.; Clarissa, C.; Giddings, T.H.J.; Winey, M. ε-tubulin is essential in Tetrahymena thermophila for the assembly and stability of basal bodies. J. Cell Sci. 2013, 126, 3441–3451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krauhs, E.; Little, M.; Kempf, T.; Hofer-Warbinek, R.; Ade, W.; Ponstingl, H. Complete amino acid sequence of β-tubulin from porcine brain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1981, 78, 4156–4160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fygenson, D.K.; Needleman, D.J.; Sneppen, K. Variability-based sequence alignment identifies residues responsible for functional differences in α and β tubulin. Protein Sci. 2004, 13, 25–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bode, C.J.; Gupta, M.L.; Suprenant, K.A.; Himes, R.H. The two α-tubulin isotypes in budding yeast have opposing effects on microtubule dynamics in vitro. EMBO Rep. 2003, 4, 94–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nsamba, E.T.; Bera, A.; Costanzo, M.; Boone, C.; Gupta, M.L., Jr. Tubulin isotypes optimize distinct spindle positioning mechanisms during yeast mitosis. J. Cell Biol. 2021, 220, e202010155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.M.; Zheng, C. The expression and function of tubulin isotypes in Caenorhabditis elegans. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2022, 10, 860065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, K.; Hoff, K.J.; Wethekam, L.; Stence, N.; Saenz, M.; Moore, J.K. Kinetically stabilizing mutations in beta tubulins create isotype-specific brain malformations. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9, 765992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaglin, X.H.; Chelly, J. Tubulin-related cortical dysgeneses: Microtubule dysfunction underlying neuronal migration defects. Trends Genet. 2009, 25, 555–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aiken, J.; Buscaglia, G.; Bates, E.A.; Moore, J.K. The α-tubulin gene TUBA1A in brain development: A key ingredient in the neuronal isotype blend. J. Dev. Biol. 2017, 5, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoff, K.J.; Neumann, A.J.; Moore, J.K. The molecular biology of tubulinopathies: Understanding the impact of variants on tubulin structure and microtubule regulation. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2022, 16, 1023267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romaniello, R.; Zucca, C.; Arrigoni, F.; Bonanni, P.; Panzeri, E.; Bassi, M.T.; Borgatti, R. Epilepsy in tubulinopathy: Personal series and literature review. Cells 2019, 8, 669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmidt, L.; Wain, K.E.; Hajek, C.; Estrada-Veras, J.I.; Sacoto, M.J.G.; Wentzensen, I.M.; Malhotra, A.; Clause, A.; Perry, D.; Moreno-De-Luca, A.; et al. Expanding the Phenotype of TUBB2A -Related Tubulinopathy: Three Cases of a Novel, Heterozygous TUBB2A Pathogenic Variant p.Gly98Arg. Mol. Syndromol. 2021, 12, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stottmann, R.W.; Driver, A.; Gutierrez, A.; Skelton, M.R.; Muntifering, M.; Stepien, C.; Knudson, L.; Kofron, M.; Vorhees, C.V.; Williams, M.T. A heterozygous mutation in tubulin, beta 2B (Tubb2b) causes cognitive deficits and hippocampal disorganization. Genes Brain Behav. 2017, 16, 250–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romaniello, R.; Arrigoni, F.; Fry, A.E.; Bassi, M.T.; Rees, M.I.; Borgatti, R.; Pilz, D.T.; Cushion, T.D. Tubulin genes and malformations of cortical development. Eur. J. Med. Genet. 2018, 61, 744–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tischfield, M.A.; Baris, H.N.; Wu, C.; Rudolph, G.; Van Maldergem, L.; He, W.; Chan, W.M.; Andrews, C.; Demer, J.L.; Robertson, R.L.; et al. Human TUBB3 Mutations Perturb Microtubule Dynamics, Kinesin Interactions, and Axon Guidance. Cell 2010, 140, 74–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Welburn, J.P. A circle of life: Platelet and megakaryocyte cytoskeleton dynamics in health and disease. Open Biol. 2024, 14, 240041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, A.L.; Teo, W.S.; McCarroll, J.A.; Kavallaris, M. An emerging role for tubulin isotypes in modulating cancer biology and chemotherapy resistance. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 1434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Yue, C.; Chen, J.; Tian, C.; Yang, D.; Xing, L.; Liu, H.; Jin, Y. Class III β-tubulin in colorectal cancer: Tissue distribution and clinical analysis of Chinese patients. Med. Sci. Monit. 2016, 22, 3915–3924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Höflmayer, D.; Öztürk, E.; Schroeder, C.; Hube-Magg, C.; Blessin, N.C.; Simon, R.; Lang, D.S.; Neubauer, E.; Göbel, C.; Heinrich, M.C.; et al. High expression of class III β-tubulin in upper gastrointestinal cancer types. Oncol. Lett. 2018, 16, 7139–7145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cuenca-Zamora, E.J.; Ferrer-Marín, F.; Rivera, J.; Teruel-Montoya, R. Tubulin in Platelets: When the Shape Matters. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 3484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feizabadi, M.S.; Narayanareddy, B.R.J.; Vadpey, O.; Jun, Y.; Chapman, D.; Rosenfeld, S.; Gross, S.P. Microtubule C-Terminal Tails Can Change Characteristics of Motor Force Production. Traffic 2015, 16, 1075–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wloga, D.; Joachimiak, E.; Louka, P.; Gaertig, J. Posttranslational modifications of Tubulin and cilia. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2017, 9, a028159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janke, C.; Magiera, M.M. The tubulin code and its role in controlling microtubule properties and functions. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2020, 21, 307–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramkumar, A.; Jong, B.Y.; Ori-McKenney, K.M. ReMAPping the microtubule landscape: How phosphorylation dictates the activities of microtubule-associated proteins. Dev. Dyn. 2018, 247, 138–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmona, B.; Marinho, H.S.; Matos, C.L.; Nolasco, S.; Soares, H. Tubulin Post-Translational Modifications: The Elusive Roles of Acetylation. Biology 2023, 12, 561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacTaggart, B.; Kashina, A. Posttranslational modifications of the cytoskeleton. Cytoskeleton 2021, 78, 142–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sahab, Z.J.; Kirilyuk, A.; Zhang, L.; Khamis, Z.I.; Pompach, P.; Sung, Y.; Byers, S.W. Analysis of tubulin alpha-1A/1B C-terminal tail post-translational poly-glutamylation reveals novel modification sites. Proc. J. Proteome Res. 2012, 11, 1913–1923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roll-Mecak, A. The Tubulin Code in Microtubule Dynamics and Information Encoding. Dev. Cell 2020, 54, 7–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalebic, N.; Sorrentino, S.; Perlas, E.; Bolasco, G.; Martinez, C.; Heppenstall, P.A. αTAT1 is the major α-tubulin acetyltransferase in mice. Nat. Commun. 2013, 4, 1962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, H.G.; Esteve, P.O.; Ruse, C.; Lee, J.; Schaus, S.E.; Pradhan, S.; Hansen, U. The microtubule-associated histone methyltransferase SET8, facilitated by transcription factor LSF, methylates α-tubulin. J. Biol. Chem. 2020, 295, 4748–4759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kearns, S.; Mason, F.M.; Rathmell, W.K.; Park, I.Y.; Walker, C.; Verhey, K.J.; Cianfrocco, M.A. Molecular determinants for α-tubulin methylation by SETD2. J. Biol. Chem. 2021, 297, 100898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zambito, A.M.; Wolff, J. Plasma membrane localization of palmitoylated tubulin. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2001, 283, 42–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, Y.; Kirkpatrick, L.L.; Schilling, A.B.; Helseth, D.L.; Chabot, N.; Keillor, J.W.; Johnson, G.V.; Brady, S.T. Transglutaminase and Polyamination of Tubulin: Posttranslational Modification for Stabilizing Axonal Microtubules. Neuron 2013, 78, 109–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lesort, M.; Tucholski, J.; Miller, M.L.; Johnson, G.V. Tissue transglutaminase: A possible role in neurodegenerative diseases. Prog. Neurobiol. 2000, 61, 439–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonnet, C.; Boucher, D.; Lazereg, S.; Pedrotti, B.; Islam, K.; Denoulet, P.; Larcher, J.C. Differential Binding Regulation of Microtubule-associated Proteins MAP1A, MAP1B, and MAP2 by Tubulin Polyglutamylation. J. Biol. Chem. 2001, 276, 12839–12848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacroix, B.; Dijk, J.V.; Gold, N.D.; Guizetti, J.; Aldrian-Herrada, G.; Rogowski, K.; Gerlich, D.W.; Janke, C. Tubulin polyglutamylation stimulates spastin-mediated microtubule severing. J. Cell Biol. 2010, 189, 945–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suryavanshi, S.; Eddé, B.; Fox, L.A.; Guerrero, S.; Hard, R.; Hennessey, T.; Kabi, A.; Malison, D.; Pennock, D.; Sale, W.S.; et al. Tubulin Glutamylation Regulates Ciliary Motility by Altering Inner Dynein Arm Activity. Curr. Biol. 2010, 20, 435–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Dijk, J.; Rogowski, K.; Miro, J.; Lacroix, B.; Eddé, B.; Janke, C. A Targeted Multienzyme Mechanism for Selective Microtubule Polyglutamylation. Mol. Cell 2007, 26, 437–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ping, Y.; Ohata, K.; Kikushima, K.; Sakamoto, T.; Islam, A.; Xu, L.; Zhang, H.; Chen, B.; Yan, J.; Eto, F.; et al. Tubulin Polyglutamylation by TTLL1 and TTLL7 Regulate Glutamate Concentration in the Mice Brain. Biomolecules 2023, 13, 784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosch Grau, M.; Gonzalez Curto, G.; Rocha, C.; Magiera, M.M.; Marques Sousa, P.; Giordano, T.; Spassky, N.; Janke, C. Tubulin glycylases and glutamylases have distinct functions in stabilization and motility of ependymal cilia. J. Cell Biol. 2013, 202, 441–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gadadhar, S.; Viar, G.A.; Hansen, J.N.; Gong, A.; Kostarev, A.; Ialy-Radio, C.; Leboucher, S.; Whitfield, M.; Ziyyat, A.; Touré, A.; et al. Tubulin glycylation controls axonemal dynein activity, flagellar beat, and male fertility. Science 2021, 371, eabd4914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Redeker, V.; Levilliers, N.; Schmitter, J.M.; Le Caer, J.P.; Rossier, J.; Adoutte, A.; Bré, M.H. Polyglycylation of tubulin: A posttranslational modification in axonemal microtubules. Science 1994, 266, 1688–1691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robson, S.J.; Burgoyne, R.D. Differential localisation of tyrosinated, detyrosinated, and acetylated α-tubulins in neurites and growth cones of dorsal root ganglion neurons. Cell Motil. 1989, 12, 273–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKenney, R.J.; Huynh, W.; Vale, R.D.; Sirajuddin, M. Tyrosination of α-tubulin controls the initiation of processive dynein–dynactin motility. EMBO J. 2016, 35, 1175–1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girão, H.; Macário-Monteiro, J.; Figueiredo, A.C.; e Sousa, R.S.; Doria, E.; Demidov, V.; Osório, H.; Jacome, A.; Meraldi, P.; Grishchuk, E.L.; et al. α-tubulin detyrosination fine-tunes kinetochore-microtubule attachments. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 9720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fourest-Lieuvin, A.; Peris, L.; Gache, V.; Garcia-Saez, I.; Juillan-Binard, C.; Lantez, V.; Job, D. Microtubule regulation in mitosis: Tubulin phosphorylation by the cyclin-dependent kinase Cdk1. Mol. Biol. Cell 2006, 17, 1041–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Shao, W.; Chai, Y.; Huang, J.; Mohamed, M.A.A.; Ökten, Z.; Li, W.; Zhu, Z.; Ou, G. DYF-5/MAK–dependent phosphorylation promotes ciliary tubulin unloading. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2022, 119, e2207134119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, W.; Liu, R.; Xie, X.; Diao, L.; Gao, N.; Cheng, J.; Zhang, X.; Li, Y.; Bao, L. SUMOylation of α-tubulin is a novel modification regulating microtubule dynamics. J. Mol. Cell Biol. 2021, 13, 91–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; He, Y.; Wang, X.; liang, Z.; He, G.; Zhang, P.; Zhu, H.; Xu, N.; Liang, S. Protein SUMOylation modification and its associations with disease. Open Biol. 2017, 7, 170167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Liang, Y.; Zou, J.; Cai, Z.; Yang, H.; Yang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Lin, H.; Zhang, G.; Tan, M. SUMOylation of microtubule-cleaving enzyme KATNA1 promotes microtubule severing and neurite outgrowth. J. Biol. Chem. 2022, 298, 102292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, Y.; Zhao, J.; Feng, J. Parkin Binds to α/β Tubulin and Increases their Ubiquitination and Degradation. J. Neurosci. 2003, 23, 3316–3324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Starita, L.M.; Machida, Y.; Sankaran, S.; Elias, J.E.; Griffin, K.; Schlegel, B.P.; Gygi, S.P.; Parvin, J.D. BRCA1-Dependent Ubiquitination of γ-Tubulin Regulates Centrosome Number. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2004, 24, 8457–8466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Q.; Peng, Z.; Long, H.; Deng, X.; Huang, K. Polyubiquitylation of α-tubulin at K304 is required for flagellar disassembly in Chlamydomonas. J. Cell Sci. 2019, 132, jcs229047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iuzzolino, A.; Pellegrini, F.R.; Rotili, D.; Degrassi, F.; Trisciuoglio, D. The α-tubulin acetyltransferase ATAT1: Structure, cellular functions, and its emerging role in human diseases. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2024, 81, 193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, C.W.; Hou, F.; Zhang, J.; Phu, L.; Loktev, A.V.; Kirkpatrick, D.S.; Jackson, P.K.; Zhao, Y.; Zou, H. A novel acetylation of β-tubulin by San modulates microtubule polymerization via down-regulating tubulin incorporation. Mol. Biol. Cell 2011, 22, 448–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro-Castro, A.; Janke, C.; Montagnac, G.; Paul-Gilloteaux, P.; Chavrier, P. ATAT1/MEC-17 acetyltransferase and HDAC6 deacetylase control a balance of acetylation of α-tubulin and cortactin and regulate MT1-MMP trafficking and breast tumor cell invasion. Eur. J. Cell Biol. 2012, 91, 950–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szyk, A.; Deaconescu, A.M.; Spector, J.; Goodman, B.; Valenstein, M.L.; Ziolkowska, N.E.; Kormendi, V.; Grigorieff, N.; Roll-Mecak, A. Molecular basis for age-dependent microtubule acetylation by tubulin acetyltransferase. Cell 2014, 157, 1405–1415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Yang, X.J. Tubulin acetylation: Responsible enzymes, biological functions and human diseases. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2015, 72, 4237–4255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Guan, T.; Li, Z.; Guo, B.; Luo, X.; Guo, L.; Li, M.; Xu, M.; Liu, M.; Liu, Y. Eml1 promotes axonal growth by enhancing αtat1-mediated microtubule acetylation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta BBA-Mol. Cell Res. 2024, 1871, 119770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Zhu, X.; Huang, Z.; Ren, K.; Ran, J.; Yang, Y. Histone Deacetylase 6 (HDAC6) in Ciliopathies: Emerging Insights and Therapeutic Implications. Adv. Sci. 2025, 12, 2412921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ran, J.; Yang, Y.; Li, D.; Liu, M.; Zhou, J. Deacetylation of α-tubulin and cortactin is required for HDAC6 to trigger ciliary disassembly. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 12917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dai, Y.; Faller, D.V. Transcription Regulation by Class III Histone Deacetylases (HDACs)-Sirtuins. Transl. Oncogenom. 2008, 3, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmona, B.; L. S. Delgado, I.; Nolasco, S.; Marques, R.; Gonçalves, J.; Soares, H. Tubulin Acetylation and the Cellular Mechanosensing and Stress Response. In Histone and Non-Histone Reversible Acetylation in Development, Aging and Disease; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; pp. 141–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portran, D.; Schaedel, L.; Xu, Z.; Théry, M.; Nachury, M.V. Tubulin acetylation protects long-lived microtubules against mechanical ageing. Nat. Cell Biol. 2017, 19, 391–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bance, B.; Seetharaman, S.; Leduc, C.; Boëda, B.; Etienne-Manneville, S. Microtubule acetylation but not detyrosination promotes focal adhesion dynamics and astrocyte migration. J. Cell Sci. 2019, 132, jcs225805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Schaedel, L.; Portran, D.; Aguilar, A.; Gaillard, J.; Marinkovich, M.P.; Théry, M.; Nachury, M.V. Microtubules acquire resistance from mechanical breakage through intralumenal acetylation. Science 2017, 356, 328–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, N.A.; Cai, D.; Blasius, T.L.; Jih, G.T.; Meyhofer, E.; Gaertig, J.; Verhey, K.J. Microtubule Acetylation Promotes Kinesin-1 Binding and Transport. Curr. Biol. 2006, 16, 2166–2172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinones, G.B.; Danowski, B.A.; Devaraj, A.; Singh, V.; Ligon, L.A. The posttranslational modification of tubulin undergoes a switch from detyrosination to acetylation as epithelial cells become polarized. Mol. Biol. Cell 2011, 22, 1045–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteiro, P.; Yeon, B.; Wallis, S.S.; Godinho, S.A. Centrosome amplification fine tunes tubulin acetylation to differentially control intracellular organization. EMBO J. 2023, 42, e112812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naren, P.; Samim, K.S.; Tryphena, K.P.; Vora, L.K.; Srivastava, S.; Singh, S.B.; Khatri, D.K. Microtubule acetylation dyshomeostasis in Parkinson’s disease. Transl. Neurodegener. 2023, 12, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dompierre, J.P.; Godin, J.D.; Charrin, B.C.; Cordelières, F.P.; King, S.J.; Humbert, S.; Saudou, F. Histone deacetylase 6 inhibition compensates for the transport deficit in Huntington’s disease by increasing tubulin acetylation. J. Neurosci. 2007, 27, 3571–3583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaughan, E.E.; Dean, D.A. Intracellular Trafficking of Plasmids during Transfection Is Mediated by Microtubules. Mol. Ther. 2006, 13, 422–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badding, M.A.; Dean, D.A. Highly acetylated tubulin permits enhanced interactions with and trafficking of plasmids along microtubules. Gene Ther. 2013, 20, 616–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardiner, J.; Barton, D.; Marc, J.; Overall, R. Potential Role of Tubulin Acetylation and Microtubule-Based Protein Trafficking in Familial Dysautonomia. Traffic 2007, 8, 1145–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donker, L.; Godinho, S.A. Rethinking tubulin acetylation: From regulation to cellular adaptation. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2025, 94, 102512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akella, J.S.; Wloga, D.; Kim, J.; Starostina, N.G.; Lyons-Abbott, S.; Morrissette, N.S.; Dougan, S.T.; Kipreos, E.T.; Gaertig, J. MEC-17 is an α-tubulin acetyltransferase. Nature 2010, 467, 218–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shida, T.; Cueva, J.G.; Xu, Z.; Goodman, M.B.; Nachury, M.V. The major α-tubulin K40 acetyltransferase αTAT1 promotes rapid ciliogenesis and efficient mechanosensation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 21517–21522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumann, B.; Hilliard, M.A. Loss of MEC-17 leads to microtubule instability and axonal degeneration. Cell Rep. 2014, 6, 93–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valenzuela-Fernandez, A.; Cabrero, J.R.; Serrador, J.M.; Sanchez-Madrid, F. HDAC6: A key regulator of cytoskeleton, cell migration and cell–cell interactions. Trends Cell Biol. 2008, 18, 291–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aldana-Masangkay, G.I.; Sakamoto, K.M. The role of HDAC6 in cancer. BioMed Res. Int. 2011, 2011, 875824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- New, M.; Olzscha, H.; La Thangue, N.B. HDAC inhibitor-based therapies: Can we interpret the code. Mol. Oncol. 2012, 6, 637–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, A.D.A.; Marmo, T.P.; Salam, A.A.; Che, S.; Finkelstein, E.; Kabarriti, R.; Xenias, H.S.; Mazitschek, R.; Hubbert, C.; Kawaguchi, Y.; et al. HDAC6 deacetylation of tubulin modulates dynamics of cellular adhesions. J. Cell Sci. 2007, 120, 1469–1479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado, I.L.; Gonçalves, J.; Fernandes, R.; Zúquete, S.; Basto, A.P.; Leitão, A.; Soares, H.; Nolasco, S. Balancing act: Tubulin glutamylation and microtubule dynamics in Toxoplasma gondii. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, I.Y.; Powell, R.T.; Tripathi, D.N.; Dere, R.; Ho, T.H.; Blasius, T.L.; Chiang, Y.C.; Davis, I.J.; Fahey, C.C.; Hacker, K.E.; et al. Dual Chromatin and Cytoskeletal Remodeling by SETD2. Cell 2016, 166, 950–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koenning, M.; Wang, X.; Karki, M.; Jangid, R.K.; Kearns, S.; Tripathi, D.N.; Cianfrocco, M.; Verhey, K.J.; Jung, S.Y.; Coarfa, C.; et al. Neuronal SETD2 activity links microtubule methylation to an anxiety-like phenotype in mice. Brain 2021, 144, 2527–2540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, S.; Wang, S.; Xie, X.; Tan, X.; Hu, X.; Shao, F.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, X.; Cheng, H.; Diao, L.; et al. KDM4A serves as an α-tubulin demethylase regulating microtubule polymerization and cell mitosis. Sci. Adv. 2025, 11, eadv6637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, I.Y.; Chowdhury, P.; Tripathi, D.N.; Powell, R.T.; Dere, R.; Terzo, E.A.; Rathmell, W.K.; Walker, C.L. Methylated α-tubulin antibodies recognize a new microtubule modification on mitotic microtubules. mAbs 2016, 8, 1590–1597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szasz, J.; Burns, R.; Sternlicht, H. Effects of reductive methylation on microtubule assembly. Evidence for an essential amino group in the alpha-chain. J. Biol. Chem. 1982, 257, 3697–3704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, X.; Wang, S.; Li, M.; Diao, L.; Pan, X.; Chen, J.; Zou, W.; Zhang, X.; Feng, W.; Bao, L. α-TubK40me3 is required for neuronal polarization and migration by promoting microtubule formation. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 4113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michail, C.; Rodrigues Lima, F.; Viguier, M.; Deshayes, F. Structure and function of the lysine methyltransferase SETD2 in cancer: From histones to cytoskeleton. Neoplasia 2025, 59, 101090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agborbesong, E.; Zhou, J.X.; Zhang, H.; Li, L.X.; Harris, P.C.; Calvet, J.P.; Li, X. Overexpression of SMYD3 promotes autosomal Dominant polycystic kidney disease by mediating cell proliferation and genome instability. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, R.; Zhao, W.Q.; Fang, C.; Yang, X.; Ji, M. Histone methyltransferase SETD2: A potential tumor suppressor in solid cancers. J. Cancer 2020, 11, 3349–3356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Rodríguez, P.; Engskog-Vlachos, P.; Zhang, H.; Murgoci, A.N.; Zerdes, I.; Joseph, B. SETD2 mutation in renal clear cell carcinoma suppress autophagy via regulation of ATG12. Cell Death Dis. 2020, 11, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jørgensen, S.; Elvers, I.; Trelle, M.B.; Menzel, T.; Eskildsen, M.; Jensen, O.N.; Helleday, T.; Helin, K.; Sørensen, C.S. The histone methyltransferase SET8 is required for S-phase progression. J. Cell Biol. 2007, 179, 1337–1345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Zhang, L.; Sun, J.; Hu, X.; Kalvakolanu, D.V.; Ren, H.; Guo, B. Roles for the methyltransferase SETD8 in DNA damage repair. Clin. Epigenet. 2022, 14, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Lyu, T.; Che, X.; Jia, N.; Li, Q.; Feng, W. Overexpression of SMYD3 in ovarian cancer is associated with ovarian cancer proliferation and apoptosis via methylating H3K4 and H4K20. J. Cancer 2019, 10, 4072–4084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, C.L.; Huang, Q. Overexpression of the SMYD3 Promotes Proliferation, Migration, and Invasion of Pancreatic Cancer. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2020, 65, 489–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozols, J.; Carontt, J.M. Posttranslational Modification of Tubulin by Palmitoylation: II. Identification of Sites of Palmitoylation. Mol. Biol. Cell 1997, 8, 637–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zambito, A.M.; Wolff, J. Palmitoylation of Tubulin. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1997, 239, 650–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Qian, P.; Cui, H.; Yao, L.; Yuan, J. A protein palmitoylation cascade regulates microtubule cytoskeleton integrity in Plasmodium. EMBO J. 2020, 39, e104168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tortosa, E.; Adolfs, Y.; Fukata, M.; Pasterkamp, R.J.; Kapitein, L.C.; Hoogenraad, C.C. Dynamic Palmitoylation Targets MAP6 to the Axon to Promote Microtubule Stabilization during Neuronal Polarization. Neuron 2017, 94, 809–825.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolff, J. Plasma membrane tubulin. Biochim. Biophys. Acta BBA Biomembr. 2009, 1788, 1415–1433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolff, J.; Zambito, A.M.; Britto, P.J.; Knipling, L. Autopalmitoylation of tubulin. Protein Sci. 2000, 9, 1357–1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caron, J.M. Posttranslational modification of tubulin by palmitoylation: I. In vivo and cell-free studies. Mol. Biol. Cell 1997, 8, 621–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Z.; Hou, J.; Xie, Z.; Deng, J.; Wang, X.; Chen, D.; Yang, F.; Gong, W. Acyl-biotinyl exchange chemistry and mass spectrometry-based analysis of palmitoylation sites of in vitro palmitoylated rat brain tubulin. Protein J. 2010, 29, 531–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caron, J.M.; Vega, L.R.; Fleming, J.; Bishop, R.; Solomon, F. Single Site α-Tubulin Mutation Affects Astral Microtubules and Nuclear Positioning during Anaphase in Saccharomyces cerevisiae: Possible Role for Palmitoylation of α-Tubulin. Mol. Biol. Cell 2001, 12, 2672–2687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, C.T.; Kuo, H.H.; Amartuvshin, O.; Hsu, H.J.; Liu, S.L.; Yao, J.S.; Yih, L.H. Inhibition of acetyl-CoA carboxylase impaired tubulin palmitoylation and induced spindle abnormalities. Cell Death Discov. 2023, 9, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripathi, P.; Zhu, Z.; Qin, H.; Elsherbini, A.; Crivelli, S.M.; Roush, E.; Wang, G.; Spassieva, S.D.; Bieberich, E. Palmitoylation of acetylated tubulin and association with ceramide-rich platforms is critical for ciliogenesis. J. Lipid Res. 2021, 62, 100021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caron, J.M.; Herwood, M. Vinblastine, a chemotherapeutic drug, inhibits palmitoylation of tubulin in human leukemic lymphocytes. Chemotherapy 2007, 53, 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S., P.B.; Talwar, P. Influence of palmitoylation in axonal transport mechanisms in neurodegenerative diseases. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2025, 19, 1613379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, B.; Hao, Q.; Liang, Y.; Kong, E. Protein palmitoylation in cancer: Molecular functions and therapeutic potential. Mol. Oncol. 2022, 17, 3–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Zhang, J.; Zou, L.; Cui, J.; Su, F.; Jin, J.; Xiao, F.; Liu, M.; Zhao, G. Palmitoylome profiling indicates that androgens regulate the palmitoylation of α-tubulin in prostate cancer-derived LNCaP cells and supernatants. Oncol. Rep. 2019, 42, 2788–2796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Brady, S.T. Post-translational modifications of tubulin: Pathways to functional diversity of microtubules. Trends Cell Biol. 2015, 25, 125–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magiera, M.M.; Janke, C. Post-translational modifications of tubulin. Curr. Biol. 2014, 24, R351–R354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeitner, T.M.; Matson, W.R.; Folk, J.E.; Blass, J.P.; Cooper, A.J. Increased levels of γ-glutamylamines in Huntington disease CSF. J. Neurochem. 2008, 106, 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matamoros, A.J.; Baas, P.W. Microtubules in health and degenerative disease of the nervous system. Brain Res. Bull. 2016, 126, 217–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller-Fleming, L.; Olin-Sandoval, V.; Campbell, K.; Ralser, M. Remaining mysteries of molecular biology: The role of polyamines in the cell. J. Mol. Biol. 2015, 427, 3389–3406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maccioni, R.B.; Seeds, N.W. Transglutaminase and neuronal differentiation. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 1986, 69, 161–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorand, L.; Graham, R.M. Transglutaminases: Crosslinking enzymes with pleiotropic functions. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2003, 4, 140–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komaromi, I.; Bagoly, Z.; Muszbek, L. Factor XIII: Novel structural and functional aspects. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2011, 9, 9–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudlong, J.; Cheng, A.; Johnson, G.V. The role of transglutaminase 2 in mediating glial cell function and pathophysiology in the central nervous system. Anal. Biochem. 2020, 591, 113556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruan, Q.; Johnson, G. Transglutaminase 2 in neurodegenerative disorders. Front. Biosci 2007, 12, 891–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, S.Y.; Lee, J.H.; Bae, H.D.; Jeong, E.M.; Jang, G.Y.; Kim, C.W.; Shin, D.M.; Jeon, J.H.; Kim, I.G. Transglutaminase 2 inhibits apoptosis induced by calciumoverload through down-regulation of Bax. Exp. Mol. Med. 2010, 42, 639–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Mouradian, M.M. Pathogenetic contributions and therapeutic implications of transglutaminase 2 in neurodegenerative diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 2364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wloga, D.; Dave, D.; Meagley, J.; Rogowski, K.; Jerka-Dziadosz, M.; Gaertig, J. Hyperglutamylation of tubulin can either stabilize or destabilize microtubules in the same cell. Eukaryot. Cell 2010, 9, 184–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wloga, D.; Rogowski, K.; Sharma, N.; Dijk, J.V.; Janke, C.; Eddé, B.; Bré, M.H.; Levilliers, N.; Redeker, V.; Duan, J.; et al. Glutamylation on α-tubulin is not essential but affects the assembly and functions of a subset of microtubules in Tetrahymena thermophila. Eukaryot. Cell 2008, 7, 1362–1372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tort, O.; Tanco, S.; Rocha, C.; Biéche, I.; Seixas, C.; Bosc, C.; Andrieux, A.; Moutin, M.J.; Avilés, F.X.; Lorenzo, J.; et al. The cytosolic carboxypeptidases CCP2 and CCP3 catalyze posttranslational removal of acidic amino acids. Mol. Biol. Cell 2014, 25, 3017–3027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kubo, T.; Sasaki, R.; Oda, T. Tubulin glycylation controls ciliary motility through modulation of outer-arm dyneins. Mol. Biol. Cell 2024, 35, ar90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valenstein, M.L.; Roll-Mecak, A. Graded Control of Microtubule Severing by Tubulin Glutamylation. Cell 2016, 164, 911–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janke, C.; Rogowski, K.; van Dijk, J. Polyglutamylation: A fine-regulator of protein function ’Protein Modifications: Beyond the Usual Suspects’ Review Series. EMBO Rep. 2008, 9, 636–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, M.; Dörig, R.E.; Vazquez-Pianzola, P.M.; Beuchle, D.; Suter, B. Differential modification of the C-terminal tails of different α-tubulins and their importance for microtubule function in vivo. eLife 2023, 12, e87125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lessard, D.V.; Zinder, O.J.; Hotta, T.; Verhey, K.J.; Ohi, R.; Berger, C.L. Polyglutamylation of tubulin’s C-terminal tail controls pausing and motility of kinesin-3 family member KIF1A. J. Biol. Chem. 2019, 294, 6353–6363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferro, L.S.; Fang, Q.; Eshun-Wilson, L.; Fernandes, J.; Jack, A.; Farrell, D.P.; Golcuk, M.; Huijben, T.; Costa, K.; Gur, M.; et al. Structural and functional insight into regulation o kinesin-1 by microtubule-associated protein MAP7. Science 2022, 375, 326–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheikh, A.M.; Tabassum, S. Potential role of tubulin glutamylation in neurodegenerative diseases. Neural Regen. Res. 2024, 19, 1191–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodakuntla, S.; Schnitzler, A.; Villablanca, C.; González-Billault, C.; Bieche, I.; Janke, C.; Magiera, M.M. Tubulin polyglutamylation is a general traffic-control mechanism in hippocampal neurons. J. Cell Sci. 2020, 133, jcs241802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukai, M.; Ikegami, K.; Sugiura, Y.; Takeshita, K.; Nakagawa, A.; Setou, M. Recombinant mammalian Tubulin polyglutamylase TTLL7 performs both initiation and elongation of polyglutamylation on ß-Tubulin through a random sequential pathway. Biochemistry 2009, 48, 1084–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, S.R.; Wang, C.L.; Huang, Y.S.; Chang, Y.C.; Chang, Y.C.; Pusapati, G.V.; Lin, C.Y.; Hsu, N.; Cheng, H.C.; Chiang, Y.C.; et al. Spatiotemporal manipulation of ciliary glutamylation reveals its roles in intraciliary trafficking and Hedgehog signaling. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 1732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.T.; Hong, S.R.; He, K.; Ling, K.; Shaiv, K.; Hu, J.H.; Lin, Y.C. The Emerging Roles of Axonemal Glutamylation in Regulation of Cilia Architecture and Functions. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9, 622302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szczesna, E.; Zehr, E.A.; Cummings, S.W.; Szyk, A.; Mahalingan, K.K.; Li, Y.; Roll-Mecak, A. Combinatorial and antagonistic effects of tubulin glutamylation and glycylation on katanin microtubule severing. Dev. Cell 2022, 57, 2497–2513.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roll-Mecak, A. Intrinsically disordered tubulin tails: Complex tuners of microtubule functions. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2015, 37, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodakuntla, S.; Yuan, X.; Genova, M.; Gadadhar, S.; Leboucher, S.; Birling, M.; Klein, D.; Martini, R.; Janke, C.; Magiera, M.M. Distinct roles of α- and β-tubulin polyglutamylation in controlling axonal transport and in neurodegeneration. EMBO J. 2021, 40, e108498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zadra, I.; Jimenez-Delgado, S.; Anglada-Girotto, M.; Segura-Morales, C.; Compton, Z.J.; Janke, C.; Serrano, L.; Ruprecht, V.; Vernos, I. Chromosome segregation fidelity requires microtubule polyglutamylation by the cancer downregulated enzyme TTLL11. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 7147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laan, S.V.D.; Dubra, G.; Rogowski, K. Tubulin glutamylation: A skeleton key for neurodegenerative diseases. Neural Regen. Res. 2019, 14, 1899–1900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wasylyk, C.; Zambrano, A.; Zhao, C.; Brants, J.; Abecassis, J.; Schalken, J.A.; Rogatsch, H.; Schaefer, G.; Pycha, A.; Klocker, H.; et al. Tubulin tyrosine ligase like 12 links to prostate cancer through tubulin posttranslational modification and chromosome ploidy. Int. J. Cancer 2010, 127, 2542–2553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Liang, Y.; Qian, H.; Li, Q. Original Article TTLL12 expression in ovarian cancer correlates with a poor outcome. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Pathol. 2020, 13, 239–247. Available online: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC7061784/ (accessed on 29 October 2025). [PubMed]

- Arnold, J.; Schattschneider, J.; Blechner, C.; Krisp, C.; Schlüter, H.; Schweizer, M.; Nalaskowski, M.; Oliveira-Ferrer, L.; Windhorst, S. Tubulin Tyrosine Ligase Like 4 (TTLL4) overexpression in breast cancer cells is associated with brain metastasis and alters exosome biogenesis. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2020, 39, 205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, V.; Kanakkanthara, A.; Chan, A.; Miller, J.H. Potential role of tubulin tyrosine ligase-like enzymes in tumorigenesis and cancer cell resistance. Cancer Lett. 2014, 350, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pathak, N.; Austin-Tse, C.A.; Liu, Y.; Vasilyev, A.; Drummond, I.A. Cytoplasmic carboxypeptidase 5 regulates tubulin glutamylation and zebrafish cilia formation and function. Mol. Biol. Cell 2014, 25, 1836–1844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Astuti, G.D.N.; Arno, G.; Hull, S.; Pierrache, L.; Venselaar, H.; Carss, K.; Raymond, F.L.; Collin, R.W.J.; Faradz, S.M.H.; van den Born, L.I.; et al. Mutations in AGBL5, Encoding α-Tubulin Deglutamylase, Are Associated With Autosomal Recessive Retinitis Pigmentosa. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2016, 57, 6180–6187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Zehr, E.A.; Gruschus, J.M.; Szyk, A.; Liu, Y.; Tanner, M.E.; Tjandra, N.; Roll-Mecak, A. Tubulin code eraser CCP5 binds branch glutamates by substrate deformation. Nature 2024, 631, 905–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bosch Grau, M.; Masson, C.; Gadadhar, S.; Rocha, C.; Tort, O.; Marques Sousa, P.; Vacher, S.; Bieche, I.; Janke, C. Alterations in the balance of tubulin glycylation and glutamylation in photoreceptors leads to retinal degeneration. J. Cell Sci. 2017, 130, 938–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ikegami, K.; Setou, M. TTLL10 can perform tubulin glycylation when co-expressed with TTLL8. FEBS Lett. 2009, 583, 1957–1963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rogowski, K.; Juge, F.; van Dijk, J.; Wloga, D.; Strub, J.M.; Levilliers, N.; Thomas, D.; Bré, M.H.; Dorsselaer, A.V.; Gaertig, J.; et al. Evolutionary Divergence of Enzymatic Mechanisms for Posttranslational Polyglycylation. Cell 2009, 137, 1076–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez Viar, G.; Klena, N.; Martino, F.; Nievergelt, A.P.; Bolognini, D.; Capasso, P.; Pigino, G. Protofilament-specific nanopatterns of tubulin post-translational modifications regulate the mechanics of ciliary beating. Curr. Biol. 2024, 34, 4464–4475.e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thazhath, R.; Jerka-Dziadosz, M.; Duan, J.; Wloga, D.; Gorovsky, M.A.; Frankel, J.; Gaertig, J. Cell Context-specific Effects of the-Tubulin Glycylation Domain on Assembly and Size of Microtubular Organelles. Mol. Biol. Cell 2004, 15, 4136–4147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gadadhar, S.; Dadi, H.; Bodakuntla, S.; Schnitzler, A.; Bièche, I.; Rusconi, F.; Janke, C. Tubulin glycylation controls primary cilia length. J. Cell Biol. 2017, 216, 2701–2713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bré, M.H.; Redeker, V.; Vinh, J.; Rossier, J.; Levilliers, N. Tubulin polyglycylation: Differential posttranslational modification of dynamic cytoplasmic and stable axonemal microtubules in paramecium. Mol. Biol. Cell 1998, 9, 2655–2665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wloga, D.; Webster, D.M.; Rogowski, K.; Bré, M.H.; Levilliers, N.; Jerka-Dziadosz, M.; Janke, C.; Dougan, S.T.; Gaertig, J. TTLL3 Is a tubulin glycine ligase that regulates the assembly of cilia. Dev. Cell 2009, 16, 867–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bigman, L.S.; Levy, Y. Tubulin tails and their modifications regulate protein diffusion on microtubules. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 8876–8883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, K.; Ling, K.; Hu, J. The emerging role of tubulin posttranslational modifications in cilia and ciliopathies. Biophys. Rep. 2020, 6, 89–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wall, K.P.; Hart, H.; Lee, T.; Page, C.; Hawkins, T.L.; Hough, L.E. C-Terminal Tail Polyglycylation and Polyglutamylation Alter Microtubule Mechanical Properties. Biophys. J. 2020, 119, 2219–2230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Konno, A.; Setou, M.; Ikegami, K. Chapter three—Ciliary and Flagellar Structure and Function—Their Regulations by Posttranslational Modifications of Axonemal Tubulin. Int. Rev. Cell Mol. Biol. 2012, 294, 133–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xia, L.; Hai, B.; Gao, Y.; Burnette, D.; Thazhath, R.; Duan, J.; Bré, M.H.; Levilliers, N.; Gorovsky, M.A.; Gaertig, J. Polyglycylation of Tubulin Is Essential and Affects Cell Motility and Division in Tetrahymena thermophila. J. Cell Biol. 2000, 149, 1097–1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rocha, C.; Papon, L.; Cacheux, W.; Marques Sousa, P.; Lascano, V.; Tort, O.; Giordano, T.; Vacher, S.; Lemmers, B.; Mariani, P.; et al. Tubulin glycylases are required for primary cilia, control of cell proliferation and tumor development in colon. EMBO J. 2014, 33, 2247–2260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peris, L.; Parato, J.; Qu, X.; Soleilhac, J.M.; Lante, F.; Kumar, A.; Pero, M.E.; Martínez-Hernández, J.; Corrao, C.; Falivelli, G.; et al. Tubulin tyrosination regulates synaptic function and is disrupted in Alzheimer’s disease. Brain 2022, 145, 2486–2506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, G.; Kirabo, A.; Ahmed, U.; Liu, J.; Chen, J. Vasohibins in Health and Disease: From Angiogenesis to Tumorigenesis, Multiorgan Dysfunction, and Brain–Heart Remodeling. Cells 2025, 14, 767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulze, E.; Asai, D.J.; Bulinski, J.C.; Kirschner, M. Posttranslational modification and microtubule stability. J. Cell Biol. 1987, 105, 2167–2177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanyal, C.; Pietsch, N.; Rios, S.R.; Peris, L.; Carrier, L.; Moutin, M.J. The detyrosination/re-tyrosination cycle of tubulin and its role and dysfunction in neurons and cardiomyocytes. In Proceedings of the Seminars in Cell & Developmental Biology; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2023; Volume 137, pp. 46–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peris, L.; Thery, M.; Fauré, J.; Saoudi, Y.; Lafanechère, L.; Chilton, J.K.; Gordon-Weeks, P.; Galjart, N.; Bornens, M.; Wordeman, L.; et al. Tubulin tyrosination is a major factor affecting the recruitment of CAP-Gly proteins at microtubule plus ends. J. Cell Biol. 2006, 174, 839–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinmetz, M.O.; Akhmanova, A. Capturing protein tails by CAP-Gly domains. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2008, 33, 535–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chhatre, A.; Stepanek, L.; Nievergelt, A.P.; Viar, G.A.; Diez, S.; Pigino, G. Tubulin tyrosination/detyrosination regulate the affinity and sorting of intraflagellar transport trains on axonemal microtubule doublets. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lavrsen, K.; Rajendraprasad, G.; Leda, M.; Eibes, S.; Vitiello, E.; Katopodis, V.; Goryachev, A.B.; Barisic, M. Microtubule detyrosination drives symmetry breaking to polarize cells for directed cell migration. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2023, 120, e2300322120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, M.; Gorek, L.; Kamm, N.; Jacob, R. Manipulation of the Tubulin Code Alters Directional Cell Migration and Ciliogenesis. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2022, 10, 901999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferreira, L.T.; Orr, B.; Rajendraprasad, G.; Pereira, A.J.; Lemos, C.; Lima, J.T.; Guasch Boldú, C.; Ferreira, J.G.; Barisic, M.; Maiato, H. α-Tubulin detyrosination impairs mitotic error correction by suppressing MCAK centromeric activity. J. Cell Biol. 2020, 219, e201910064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barisic, M.; Silva e Sousa, R.; Tripathy, S.K.; Magiera, M.M.; Zaytsev, A.V.; Pereira, A.L.; Janke, C.; Grishchuk, E.L.; Maiato, H. Microtubule detyrosination guides chromosomes during mitosis. Science 2015, 348, 799–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erck, C.; Peris, L.; Andrieux, A.; Meissirel, C.; Gruber, A.D.; Vernet, M.; Schweitzer, A.; Saoudi, Y.; Pointu, H.; Bosc, C.; et al. A vital role of tubulin-tyrosine-ligase for neuronal organization. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2005, 102, 7853–7858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corrales, R.M.; Vincent, J.; Crobu, L.; Neish, R.; Nepal, B.; Espeut, J.; Pasquier, G.; Gillard, G.; Cazevieille, C.; Mottram, J.C.; et al. Tubulin detyrosination shapes Leishmania cytoskeletal architecture and virulence. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2025, 122, e2415296122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whipple, R.A.; Matrone, M.A.; Cho, E.H.; Balzer, E.M.; Vitolo, M.I.; Yoon, J.R.; Ioffe, O.B.; Tuttle, K.C.; Yang, J.; Martin, S.S. Epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition promotes tubulin detyrosination and microtentacles that enhance endothelial engagement. Cancer Res. 2010, 70, 8127–8137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mialhe, A.; Lafanechéere, L.; Treilleux, I.; Peloux, N.; Dumontet, C.; Brémond, A.; Panh, M.H.; Payan, R.; Wehland, J.; Margolis, R.L.; et al. Tubulin detyrosination is a frequent occurrence in breast cancers of poor prognosis. Cancer Res. 2001, 61, 5024–5027. Available online: https://aacrjournals.org/cancerres/article/61/13/5024/507609/Tubulin-Detyrosination-Is-a-Frequent-Occurrence-in (accessed on 29 October 2025).

- Lafanechére, L.; Courtay-Cahen, C.; Kawakami, T.; Jacrot, M.; Rüdiger, M.; Wehland, J.; Job, D.; Margolis, R.L. Suppression of tubulin tyrosine ligase during tumor growth. J. Cell Sci. 1998, 111, 171–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mathias, T.J.; Ju, J.A.; Lee, R.M.; Thompson, K.N.; Mull, M.L.; Annis, D.A.; Chang, K.T.; Ory, E.C.; Stemberger, M.B.; Hotta, T.; et al. Tubulin carboxypeptidase activity promotes focal gelatin degradation in breast tumor cells and induces apoptosis in breast epithelial cells that is overcome by oncogenic signaling. Cancers 2022, 14, 1707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, S.; Rajendraprasad, G.; Wang, N.; Eibes, S.; Gao, J.; Yu, H.; Wu, G.; Tu, X.; Huang, H.; Barisic, M.; et al. Molecular basis of vasohibins-mediated detyrosination and its impact on spindle function and mitosis. Cell Res. 2019, 29, 533–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iida-Norita, R.; Kawamura, M.; Suzuki, Y.; Hamada, S.; Masamune, A.; Furukawa, T.; Sato, Y. Vasohibin-2 plays an essential role in metastasis of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Cancer Sci. 2019, 110, 2296–2308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pietsch, N.; Chen, C.Y.; Kupsch, S.; Bacmeister, L.; Geertz, B.; Herrera-Rivero, M.; Siebels, B.; Voß, H.; Krämer, E.; Braren, I.; et al. Chronic Activation of Tubulin Tyrosination Improves Heart Function. Circ. Res. 2024, 135, 910–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siveen, K.S.; Prabhu, K.S.; Achkar, I.W.; Kuttikrishnan, S.; Shyam, S.; Khan, A.Q.; Merhi, M.; Dermime, S.; Uddin, S. Role of non receptor tyrosine kinases in hematological malignances and its targeting by natural products. Mol. Cancer 2018, 17, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abeyweera, T.P.; Chen, X.; Rotenberg, S.A. Phosphorylation of α6-tubulin by protein kinase Cα activates motility of human breast cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2009, 284, 17648–17656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eklund, G.; Lang, S.; Glindre, J.; Ehlén, Å; Alvarado-Kristensson, M. The nuclear localization of γ-tubulin is regulated by SadB-mediated phosphorylation. J. Biol. Chem. 2014, 289, 21360–21373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ludueña, R.F.; Zimmermann, H.P.; Little, M. Identification of the phosphorylated β-tubulin isotype in differentiated neuroblastoma cells. FEBS Lett. 1988, 230, 142–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohtz, D.S.; Puszkin, S. Phosphorylation of Tubulin by Casein Kinase II Regulates Its Binding to a Neuronal Protein (NP185) Associated with Brain Coated Vesicles. J. Neurochem. 1989, 52, 285–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, X.; Sayeski, P.P. Identification of tubulin as a substrate of Jak2 tyrosine kinase and its role in Jak2-dependent signaling. Biochemistry 2007, 46, 7153–7162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matten, W.T.; Aubry, M.; West, J.; Maness, P.F. Tubulin is phosphorylated at tyrosine by pp60c-src in nerve growth cone membranes. J. Cell Biol. 1990, 111, 1959–1970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, I.A.; Ludueña, R.F. Phosphorylation of βIII-Tubulin. Biochemistry 1996, 35, 3704–3711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, J.E.; Hunt, D.F.; Lee, M.K.; Shabanowitz, J.; Michel, H.; Berlin, S.C.; Macdonald, T.L.; Sundberg, R.J.; Rebhun, L.I.; Frankfurter, A. Characterization of posttranslational modifications in neuron-specific class III β-tubulin by mass spectrometry. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1991, 88, 4685–4689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caudron, F.; Denarier, E.; Thibout-Quintana, J.C.; Brocard, J.; Andrieux, A.; Fourest-Lieuvin, A. Mutation of ser172 in yeast β tubulin induces defects in microtubule dynamics and cell division. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e13553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burke, B.E.; DeLorenzo, R.J. Ca2+- and calmodulin-stimulated endogenous phosphorylation of neurotubulin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1981, 78, 991–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wandosell, F.; Serrano, L.; Avila, J. Phosphorylation of α-tubulin Carboxyl-terminal Tyrosine Prevents Its Incorporation into Microtubules. J. Biol. Chem. 1987, 262, 821334273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De, S.; Tsimounis, A.; Chen, X.; Rotenberg, S.A. Phosphorylation of α-tubulin by protein kinase C stimulates microtubule dynamics in human breast cells. Cytoskeleton 2014, 71, 257–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.F.; Dong, Q.; Bai, Y.; Gu, J.; Tao, Q.; Yue, J.; Zhou, R.; Niu, X.; Zhu, L.; Song, C.; et al. c-Abl kinase-mediated phosphorylation of γ-tubulin promotes γ-tubulin ring complexes assembly and microtubule nucleation. J. Biol. Chem. 2022, 298, 101778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laurent, C.E.; Delfino, F.J.; Cheng, H.Y.; Smithgall, T.E. The Human c-Fes Tyrosine Kinase Binds Tubulin and Microtubules through Separate Domains and Promotes Microtubule Assembly. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2004, 24, 9351–9358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ori-McKenney, K.M.; McKenney, R.J.; Huang, H.H.; Li, T.; Meltzer, S.; Jan, L.Y.; Vale, R.D.; Wiita, A.P.; Jan, Y.N. Phosphorylation of β-Tubulin by the Down Syndrome Kinase, Minibrain/DYRK1a, Regulates Microtubule Dynamics and Dendrite Morphogenesis. Neuron 2016, 90, 551–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flaskos, J.; Sachana, M.; Pen, M.; Harris, W.C.; Hargreaves, A.J. Effects of phenyl saligenin phosphate on phosphorylation of pig brain tubulin in vitro. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2006, 22, 70–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montalto, G.; Ricciarelli, R. Tau, tau kinases, and tauopathies: An updated overview. BioFactors 2023, 49, 502–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, C.; Zhu, Z.; Wang, G.; Liu, Z.; Shu, C.; Guo, J.; Wan, Q. Fluoxetin suppresses tau phosphorylation and modulates the interaction between tau and tubulin in the hippocampus of CUMS rats. Neurosci. Lett. 2024, 836, 137870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ley, S.C.; Verbi, W.; Pappin, D.J.; Druker, B.; Davies, A.A.; Crumpton, M.J. Tyrosine phosphorylation of α tubulin in human T lymphocytes. Eur. J. Immunol. 1994, 24, 99–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernandez, J.A.; Keshvara, L.M.; Peters, J.D.; Furlong, M.T.; Harrison, M.L.; Geahlen, R.L. Phosphorylation-and Activation-independent Association of the Tyrosine Kinase Syk and the Tyrosine Kinase Substrates Cbl and Vav with Tubulin in B-Cells. J. Biol. Chem. 1999, 274, 1401–1406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, J.D.; Furlong, M.T.; Asai, D.J.; Harrison, M.L.; Geahlen, R.L. Syk, Activated by Cross-linking the B-cell Antigen Receptor, Localizes to the Cytosol Where It Interacts with and Phosphorylates-Tubulin on Tyrosine. J. Biol. Chem. 1996, 271, 4755–4762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, Z.; Hecker, C.M.; Scheschonka, A.; Betz, H. Protein interactions in the sumoylation cascade–lessons from X-ray structures. FEBS J. 2008, 275, 3003–3015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayer, P.; Arndt, A.; Metzger, S.; Mahajan, R.; Melchior, F.; Jaenicke, R.; Becker, J. Structure determination of the small ubiquitin-related modifier SUMO-1. J. Mol. Biol. 1998, 280, 275–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, G. SUMO and ubiquitin in the nucleus: Different functions, similar mechanisms. Genes Dev. 2004, 18, 2046–2059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.; Mahajan, M.; Das, S.; Kumar, V. Protein SUMOylation: Current updates and insights to elucidate potential roles of SUMO in plants. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2023, 157, 398–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Zhu, S.; Guzzo, C.M.; Ellis, N.A.; Ki, S.S.; Cheol, Y.C.; Matunis, M.J. Small ubiquitin-related modifier (SUMO) binding determines substrate recognition and paralog-selective SUMO modification. J. Biol. Chem. 2008, 283, 29405–29415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryu, H.Y.; Ahn, S.H.; Hochstrasser, M. SUMO and cellular adaptive mechanisms. Exp. Mol. Med. 2020, 52, 931–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bettermann, K.; Benesch, M.; Weis, S.; Haybaeck, J. SUMOylation in carcinogenesis. Cancer Lett. 2012, 316, 113–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geiss-Friedlander, R.; Melchior, F. Concepts in sumoylation: A decade on. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2007, 8, 947–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alonso, A.; Greenlee, M.; Matts, J.; Kline, J.; Davis, K.J.; Miller, R.K. Emerging roles of sumoylation in the regulation of actin, microtubules, intermediate filaments, and septins. Cytoskeleton 2015, 72, 305–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Q.; Qin, Y.; Yang, X.; Xing, Z.; Shen, Y.; Wu, H.; Qi, Y. The function of SUMOylation and its crucial roles in the development of neurological diseases. FASEB J. 2021, 35, e21510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, I.; Neutzner, M.; Neutzner, A. Enzymes of ubiquitination and deubiquitination. Essays Biochem. 2012, 52, 37–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sankaran, S.; Crone, D.E.; Palazzo, R.E.; Parvin, J.D. BRCA1 regulates γ-tubulin binding to centrosomes. Cancer Biol. Ther. 2007, 6, 1853–1857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hames, R.S.; Wattam, S.L.; Yamano, H.; Bacchieri, R.; Fry, A.M. APC/C-mediated destruction of the centrosomal kinase Nek2A occurs in early mitosis and depends upon a cyclin A-type D-box. EMBO J. 2001, 20, 7117–7127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fry, A.M. The Nek2 protein kinase: A novel regulator of centrosome structure. Oncogene 2002, 21, 6184–6194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.F.; Huang, J.; Zhang, W.X.; Liu, Y.H.; Wang, X.; Song, J.; Jin, C.Y.; Zhang, S.Y. Tubulin degradation: Principles, agents, and applications. Bioorg. Chem. 2023, 139, 106684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Upadhyay, A.; Amanullah, A.; Chhangani, D.; Mishra, R.; Prasad, A.; Mishra, A. Mahogunin Ring Finger-1 (MGRN1), a Multifaceted Ubiquitin Ligase: Recent Unraveling of Neurobiological Mechanisms. Mol. Neurobiol. 2016, 53, 4484–4496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Srivastava, D.; Chakrabarti, O. Mahogunin-mediated α-tubulin ubiquitination via noncanonical K6 linkage regulates microtubule stability and mitotic spindle orientation. Cell Death Dis. 2014, 5, e1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, R.; Majumder, P.; Chakrabarti, O. MGRN1-mediated ubiquitination of α-tubulin regulates microtubule dynamics and intracellular transport. Traffic 2017, 18, 791–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silverman, J.S.; Skaar, J.R.; Pagano, M. SCF ubiquitin ligases in the maintenance of genome stability. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2012, 37, 66–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priyanga, J.; Guha, G.; Bhakta-Guha, D. Microtubule motors in centrosome homeostasis: A target for cancer therapy. Biochim. Biophys. Acta BBA Rev. Cancer 2021, 1875, 188524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prigozhina, N.L.; Oakley, C.E.; Lewis, A.M.; Nayak, T.; Osmani, S.A.; Oakley, B.R. γ-Tubulin Plays an Essential Role in the Coordination of Mitotic Events. Mol. Biol. Cell 2004, 15, 1374–1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sankaran, S.; Starita, L.M.; Groen, A.C.; Ko, M.J.; Parvin, J.D. Centrosomal Microtubule Nucleation Activity Is Inhibited by BRCA1-Dependent Ubiquitination. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2005, 25, 8656–8668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, J.; Jin, Y.; Wang, G. The role of SCF ubiquitin-ligase complex at the beginning of life. Reprod. Biol. Endocrinol. 2019, 17, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vodermaier, H.C. APC/C and SCF: Controlling Each Other and the Cell Cycle. Curr. Biol. 2004, 14, R787–R796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castedo, M.; Perfettini, J.L.; Roumier, T.; Andreau, K.; Medema, R.; Kroemer, G. Cell death by mitotic catastrophe: A molecular definition. Oncogene 2004, 23, 2825–2837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawson, T.M.; Dawson, V.L. The role of parkin in familial and sporadic Parkinson’s disease. Mov. Disord. 2010, 25, S32–S39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muqit, M.M.; Davidson, S.M.; Payne Smith, M.D.; MacCormac, L.P.; Kahns, S.; Jensen, P.H.; Wood, N.W.; Latchman, D.S. Parkin is recruited into aggresomes in a stress-specific manner: Over-expression of parkin reduces aggresome formation but can be dissociated from parkin’s effect on neuronal survival. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2004, 13, 117–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hames, R.S.; Crookes, R.E.; Straatman, K.R.; Merdes, A.; Hayes, M.J.; Faragher, A.J.; Fry, A.M. Dynamic Recruitment of Nek2 Kinase to the Centrosome Involves Microtubules, PCM-1, and Localized Proteasomal Degradation. Mol. Biol. Cell 2005, 16, 1711–1724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aguileta, M.A.; Korac, J.; Durcan, T.M.; Trempe, J.F.; Haber, M.; Gehring, K.; Elsasser, S.; Waidmann, O.; Fon, E.A.; Husnjak, K. The E3 ubiquitin ligase parkin is recruited to the 26 S proteasome via the proteasomal ubiquitin receptor Rpn13. J. Biol. Chem. 2015, 290, 7492–7505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Species | Tubulin Isotype | Tubulin Isotype |

|---|---|---|

| Homo sapiens | TUBA1A, TUBA1B, TUBA1C, TUBA3C, TUBA3D, TUBA3E, TUBA4A, TUBA8, TUBAL3 [20,21] | TUBB or TUBB5, TUBB2A, TUBB2B, TUBB3, TUBB4A, TUBB4B, TUBB1, TUBB6, TUBB8, TUBB8B [21] |

| Mus musculus | TUBA1A, TUBA1B, TUBA1C, TUBA4A, TUBA3A, TUBA3B, TUBA8, TUBAL3 [20] | TUBB1/ TUBB2A, TUBB2B, TUBB3, TUBB4A, TUBB4B, TUBB5, TUBB6 [20] |

| Drosophila melanogaster | TUB67C, TUB84B, TUB84D, TUB85E, TUB90E [22], refer FlyBase (https://flybase.org accessed on 29 October 2025) | TUB85D, TUB65B, TUB97EF, TUB60D, TUB56D [22], refer FlyBase (https://flybase.org accessed on 29 October 2025) |

| Caenorhabditis elegans | TBA-1, TBA-2, MEC-12, TBA-4, TBA-5, TBA-6, TBA-7, TBA-8, TBA-9 [23,24] | TBB-1, TBB-2, MEC-7, TBB-4, BEN-1, TBB-6 [23,24] |

| Saccharomyces cerevisiae | TUB1, TUB3 [25] | TUB2 [25] |

| Tetrahymena thermophila | ATU1, ALT1, ALT2, ALT3 [25,26] | BTU1, BTU2, BLT1, BLT2, BLT3, BLT4, BLT5, BLT6 [25,26] |

| Tubulin PTM | Enzyme(s) Involved | Sites of PTMs | Main Cellular Functions | Chromosome Location (Human) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acetylation | TAT1 (MEC17), San acetyltransferase | -tubulin: K40, -tubulin: K252 | Increases microtubule flexibility and stability, enhances kinesin-1 and dynein motility; protects lattice from mechanical stress [54] | 6p21.33 |

| Methylation | SET8, SETD2 | -tubulin: K40, K311; -tubulin: K19, K297 | Modulates MT stability; affects mitotic spindle assembly [55,56] | SET8- 12q24.31 |

| Palmitoylation | Palmitoyl-S-acyl-transferases | -tubulin: C376 | Affects membrane-associated trafficking [57] | Multiple loci |

| Polyamination | Transglutaminase 2 (TG2) | -tubulin: Q31, Q128, Q133, Q285 -tubulin: Q15 | Increases MT resistance to mechanical stress; stabilizes axonal MTs; supports neuronal integrity under load [58,59]. | TG2-20q11.23 |

| Glutamylation | TTLL1, TTLL4, TTLL5, TTLL6, TTLL7, TTLL11, TTLL13 | C-terminal Glu residues | Regulates MAP/motor binding; controls severing; essential for cilia beating; modulates axonal [60,61,62] & mitochondrial transport [63,64] | TTLL4-2q35, TTLL5-14q24.3 |

| Glycylation | TTLL3, TTLL8, TTLL10 | C-terminal Glu residues | Maintains cilia stability; regulates axonemal dynein function; required for axoneme assembly; affects MT surface diffusion [65,66,67] | TTLL3-3p25.3, TTLL8-22q13.33 |

| Tyrosination | TTL | C-terminal Tyr of -tubulin | Marks dynamic microtubules and promotes dynein initiation, retrograde IFT, and accurate kinetochore–MT attachments [68,69,70] | TTL-2q14.1 |

| Phosphorylation | Cdk1, Jak2, PKC, CK2, CaMKII, Syk, Fes, Src | -tubulin: S165,Y432; -tubulin: S172; -tubulin: S385 | Regulates spindle assembly and mitotic dynamics; modulates MAP binding and MT polymerization; tunes MT behaviour in response to signalling [49,71,72] | Cdk1-10q21.2 |

| SUMOylation | SUMO E1/E2/E3 ligases | -tubulin: K96, K166, K304 | Controls tubulin stability and turnover, contributes to cytoskeletal reorganization during mitosis, and fine-tunes tubulin–MAP interactions [73,74,75], and septins. | SUMO1-2q33.1 |

| Ubiquitination | E3 ligases | -tubulin: K308; -tubulin: K48, K344 | Tags tubulin for degradation, involved in chromosome segregation during cell division [76,77,78] | Multiple loci |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Nair, A.R.; Saroj, N.; Kunwar, A. Emerging Roles of Tubulin Isoforms and Their Post-Translational Modifications in Microtubule-Based Transport and Cellular Functions. Biomolecules 2026, 16, 81. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom16010081

Nair AR, Saroj N, Kunwar A. Emerging Roles of Tubulin Isoforms and Their Post-Translational Modifications in Microtubule-Based Transport and Cellular Functions. Biomolecules. 2026; 16(1):81. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom16010081

Chicago/Turabian StyleNair, Aishwarya R., Nived Saroj, and Ambarish Kunwar. 2026. "Emerging Roles of Tubulin Isoforms and Their Post-Translational Modifications in Microtubule-Based Transport and Cellular Functions" Biomolecules 16, no. 1: 81. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom16010081

APA StyleNair, A. R., Saroj, N., & Kunwar, A. (2026). Emerging Roles of Tubulin Isoforms and Their Post-Translational Modifications in Microtubule-Based Transport and Cellular Functions. Biomolecules, 16(1), 81. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom16010081