Crystalline Insights into Nasal Mucosa Inflammation and Remodeling: Unveiling Role of Galectin-10

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patients

2.2. Nasal Lavage Fluid Collection and Processing

2.3. The 3D Epithelial–Mesenchymal Trophic Unit Model

2.4. Preparation of the Cultures for Histology and Immunohistochemistry (IHC) Staining

2.5. Western Blot Analysis

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Patients’ Characteristics

3.2. Determination of Gal-10, IL-5, MUC5AC and IFNγ in Nasal Lavage Fluid of Children with SAR and Cluster Analysis

3.3. Morphometric Analysis of 3D EMTU Model

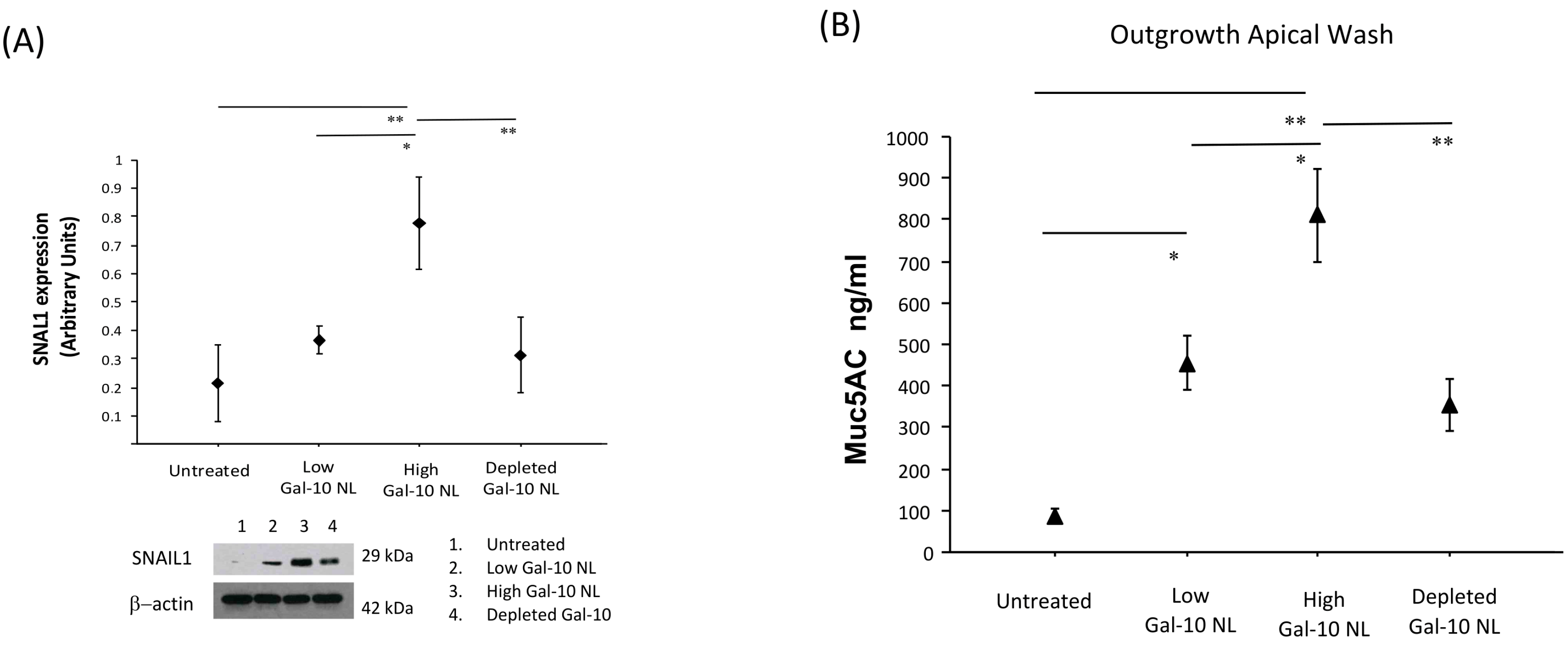

3.4. Effects of NL Exposure on EMTU Differentiation of Nasal Outgrowths

3.5. Effects of NL Exposure on MUC5AC Secretion in Apical Washes of Nasal Outgrowths

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Gal-10 | Galectin-10 |

| CLCs | Charcot-Leyden Crystals |

| SAR | Seasonal Allergic Rhinitis |

| NL | Nasal lavage |

| EMTU | epithelial–mesenchymal trophic unit |

| EMT | epithelial–mesenchymal transition |

| ALI | Air-Liquid Interface |

| TEER | trans-epithelial electrical resistance |

References

- George, L.; Brightling, C.E. Eosinophilic airway inflammation: Role in asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Ther. Adv. Chronic Dis. 2016, 7, 34–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Breiteneder, H.; Peng, Y.Q.; Agache, I.; Diamant, Z.; Eiwegger, T.; Fokkens, W.J.; Traidl-Hoffmann, C.; Nadeau, K.; O’Hehir, R.E.; O’Mahony, L.; et al. Biomarkers for diagnosis and prediction of therapy responses in allergic diseases and asthma. Allergy 2020, 75, 3039–3068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Malizia, V.; Ferrante, G.; Cilluffo, G.; Gagliardo, R.; Landi, M.; Montalbano, L.; Fasola, S.; Profita, M.; Licari, A.; Marseglia, G.L.; et al. Endotyping Seasonal Allergic Rhinitis in Children: A Cluster Analysis. Front. Med. 2022, 8, 806911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Di Cara, G.; Panfili, E.; Marseglia, G.; Pacitto, A.; Salvatori, C.; Testa, I.; Fabiano, C.; Verrotti, A.; Latini, A. Association between pollen exposure and nasal cytokines in grass pollen-allergic children. J. Investig. Allergol. Clin. Immunol. 2017, 27, 261–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segboer, C.L.; Fokkens, W.J.; Terreehorst, I.; van Drunen, C.M. Endotyping of non-allergic, allergic and mixed rhinitis patients using a broad panel of biomarkers in nasal secretions. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0200366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ciprandi, G.; Tosca, M.A.; Marseglia, G.L.; Klersy, C. Relationships between allergic inflammation and nasal airflow in children with seasonal allergic rhinitis. Ann. Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2005, 94, 258–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- König, K.; Klemens, C.; Eder, K.; San Nicoló, M.; Becker, S.; Kramer, M.F.; Gröger, M. Cytokine profiles in nasal fluid of patients with seasonal or persistent allergic rhinitis. Allergy Asthma Clin. Immunol. 2015, 11, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casado, B.; Pannell, L.K.; Iadarola, P.; Baraniuk, J.N. Identification of human nasal mucous proteins using proteomics. Proteomics 2005, 5, 2949–2959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghafouri, B.; Irander, K.; Lindbom, J.; Tagesson, C.; Lindahl, M. Comparative proteomics of nasal fluid in seasonal allergic rhinitis. J. Proteome Res. 2006, 5, 330–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maspero, J.; Adir, Y.; Al-Ahmad, M.; Celis-Preciado, C.A.; Colodenco, F.D.; Giavina-Bianchi, P.; Lababidi, H.; Ledanois, O.; Mahoub, B.; Perng, D.W.; et al. Type 2 inflammation in asthma and other airway diseases. ERJ Open Res. 2022, 8, 00576–02021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Yasukawa, A.; Hosoki, K.; Toda, M.; Miyake, Y.; Matsushima, Y.; Matsumoto, T.; Boveda-Ruiz, D.; Gil-Bernabe, P.; Nagao, M.; Sugimoto, M.; et al. Eosinophils promote epithelial to mesenchymal transition of bronchial epithelial cells. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e64281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Tomizawa, H.; Yamada, Y.; Arima, M.; Miyabe, Y.; Fukuchi, M.; Hikichi, H.; Melo, R.C.N.; Yamada, T.; Ueki, S. Galectin-10 as a Potential Biomarker for Eosinophilic Diseases. Biomolecules 2022, 12, 1385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, J. A Brief History of Charcot-Leyden Crystal Protein/Galectin-10 Research. Molecules 2018, 23, 2931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ackerman, S.J.; Corrette, S.E.; Rosenberg, H.F.; Bennett, J.C.; Mastrianni, D.M.; Nicholson-Weller, A.; Weller, P.F.; Chin, D.T.; Tenen, D.G. Molecular cloning and characterization of human eosinophil Charcot-Leyden crystal protein (lysophospholipase). Similarities to IgE binding proteins and the S type animal lectin superfamily. J. Immunol. 1993, 150, 456–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ueki, S.; Tokunaga, T.; Melo, R.C.N.; Saito, H.; Honda, K.; Fukuchi, M.; Konno, Y.; Takeda, M.; Yamamoto, Y.; Hirokawa, M.; et al. Charcot-Leyden crystal formation is closely associated with eosinophil extracellular trap cell death. Blood 2018, 132, 2183–2187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ueki, S.; Tokunaga, T.; Fujieda, S.; Honda, K.; Hirokawa, M.; Spencer, L.A.; Weller, P.F. Eosinophil ETosis and DNA Traps: A New Look at Eosinophilic Inflammation. Curr. Allergy Asthma Rep. 2016, 16, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Neves, V.H.; Palazzi, C.; Bonjour, K.; Ueki, S.; Weller, P.F.; Melo, R.C.N. In Vivo ETosis of Human Eosinophils: The Ultrastructural Signature Captured by TEM in Eosinophilic Diseases. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 938691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Melo, R.C.N.; Wang, H.; Silva, T.P.; Imoto, Y.; Fujieda, S.; Fukuchi, M.; Miyabe, Y.; Hirokawa, M.; Ueki, S.; Weller, P.F. Galectin-10, the protein that forms Charcot-Leyden crystals, is not stored in granules but resides in the peripheral cytoplasm of human eosinophils. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2020, 108, 139–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Persson, E.K.; Verstraete, K.; Heyndrickx, I.; Gevaert, E.; Aegerter, H.; Percier, J.M.; Deswarte, K.; Verschueren, K.H.G.; Dansercoer, A.; Gras, D.; et al. Protein crystallization promotes type 2 immunity and is reversible by antibody treatment. Science 2019, 364, eaaw4295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Portacci, A.; Iorillo, I.; Maselli, L.; Amendolara, M.; Quaranta, V.N.; Dragonieri, S.; Carpagnano, G.E. The Role of Galectins in Asthma Pathophysiology: A Comprehensive Review. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2024, 46, 4271–4285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Chua, J.C.; Douglass, J.A.; Gillman, A.; O’Hehir, R.E.; Meeusen, E.N. Galectin-10, a potential biomarker of eosinophilic airway inflammation. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e42549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Albano, G.D.; Di Sano, C.; Bonanno, A.; Riccobono, L.; Gagliardo, R.; Chanez, P.; Gjomarkaj, M.; Montalbano, A.M.; Anzalone, G.; La Grutta, S.; et al. Th17 immunity in children with allergic asthma and rhinitis: A pharmacological approach. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e58892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Gagliardo, R.; Chanez, P.; Profita, M.; Bonanno, A.; Albano, G.D.; Montalbano, A.M.; Pompeo, F.; Gagliardo, C.; Merendino, A.M.; Gjomarkaj, M. IκB kinase-driven nuclear factor-κB activation in patients with asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2011, 128, 635–645.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bucchieri, F.; Pitruzzella, A.; Fucarino, A.; Gammazza, A.M.; Bavisotto, C.C.; Marcianò, V.; Cajozzo, M.; Lo Iacono, G.; Marchese, R.; Zummo, G.; et al. Functional characterization of a novel 3D model of the epithelial-mesenchymal trophic unit. Exp. Lung Res. 2017, 43, 82–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gagliardo, R.; Bucchieri, F.; Montalbano, A.M.; Albano, G.D.; Gras, D.; Fucarino, A.; Marchese, R.; Anzalone, G.; Nigro, C.L.; Chanez, P.; et al. Airway epithelial dysfunction and mesenchymal transition in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: Role of Oct-4. Life Sci. 2022, 288, 120177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bucchieri, F.; Fucarino, A.; Marino Gammazza, A.; Pitruzzella, A.; Marciano, V.; Paderni, C.; De Caro, V.; Siragusa, M.G.; Lo Muzio, L.; Holgate, S.T.; et al. Medium-term culture of normal human oral mucosa: A novel three-dimensional model to study the effectiveness of drugs administration. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2012, 18, 5421–5430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fucarino, A.; Pitruzzella, A.; Burgio, S.; Intili, G.; Manna, O.M.; Modica, M.D.; Poma, S.; Benfante, A.; Tomasello, A.; Scichilone, N.; et al. A novel approach to investigate severe asthma and COPD: The 3d ex vivo respiratory mucosa model. J. Asthma 2024, 62, 110–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bryborn, M.; Halldén, C.; Säll, T.; Cardell, L.O. CLC- a novel susceptibility gene for allergic rhinitis? Allergy 2010, 65, 220–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, D.; Yan, B.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, L.; Wang, C. Predictive Significance of Charcot-Leyden Crystal Protein in Nasal Secretions in Recurrent Chronic Rhinosinusitis with Nasal Polyps. Int. Arch. Allergy Immunol. 2021, 182, 65–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hill, D.B.; Button, B.; Rubinstein, M.; Boucher, R.C. Physiology and pathophysiology of human airway mucus. Physiol. Rev. 2022, 102, 1757–1836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Fujisawa, T.; Velichko, S.; Thai, P.; Hung, L.Y.; Huang, F.; Wu, R. Regulation of airway MUC5AC expression by IL-1beta and IL-17A; the NF-kappaB paradigm. J. Immunol. 2009, 183, 6236–6243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Srinivasan, B.; Kolli, A.R.; Esch, M.B.; Abaci, H.E.; Shuler, M.L.; Hickman, J.J. TEER measurement techniques for in vitro barrier model systems. J. Lab. Autom. 2015, 20, 107–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kim, D.H.; Xing, T.; Yang, Z.; Dudek, R.; Lu, Q.; Chen, Y.H. Epithelial Mesenchymal Transition in Embryonic Development, Tissue Repair and Cancer: A Comprehensive Overview. J. Clin. Med. 2017, 7, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Stone, R.C.; Pastar, I.; Ojeh, N.; Chen, V.; Liu, S.; Garzon, K.I.; Tomic-Canic, M. Epithelial-mesenchymal transition in tissue repair and fibrosis. Cell Tissue Res. 2016, 365, 495–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Hough, K.P.; Curtiss, M.L.; Blain, T.J.; Liu, R.M.; Trevor, J.; Deshane, J.S.; Thannickal, V.J. Airway Remodeling in Asthma. Front. Med. 2020, 7, 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Nasri, A.; Foisset, F.; Ahmed, E.; Lahmar, Z.; Vachier, I.; Jorgensen, C.; Assou, S.; Bourdin, A.; De Vos, J. Roles of Mesenchymal Cells in the Lung: From Lung Development to Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Cells 2021, 10, 3467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Cano, A.; Pérez-Moreno, M.A.; Rodrigo, I.; Locascio, A.; Blanco, M.J.; del Barrio, M.G.; Portillo, F.; Nieto, M.A. The transcription factor snail controls epithelial-mesenchymal transitions by repressing E-cadherin expression. Nat. Cell Biol. 2000, 2, 76–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nieto, M.A. The snail superfamily of zinc-finger transcription factors. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2002, 3, 155–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Mean | 1st–3rd Quartiles | |

|---|---|---|

| Sex (N male/female) | 22/10 | |

| Age | 9.5 | 9–11 |

| Total IgE | 251.43 | 68–249.5 |

| Eosinophils % | 5.217 | 3.5–5.8 |

| AR (Allergic Rhinitis) Duration (Years) | 3.92 | 1.5–6 |

| Gal-10 | 0.3981 | 0.1475–0.6075 |

| MUC5AC | 0.7156 | 0.2875–1.025 |

| IL-5 | 14.48 | 5.5–20 |

| IFNγ | 7.42 | 4.83–9.83 |

| Marker | Kruskal–Wallis p | Permutation ANOVA p |

|---|---|---|

| E-cadherin | 0.1190 | 0.1090 |

| Vimentin | 0.0018 | <10−4 |

| Snail1 | 0.0900 | 0.0548 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Manna, O.M.; Malizia, V.; Perri, A.; La Grutta, S.; Fucarino, A.; Picone, D.; Profita, M.; Bucchieri, F.; Rappa, F.; Gagliardo, R. Crystalline Insights into Nasal Mucosa Inflammation and Remodeling: Unveiling Role of Galectin-10. Biomolecules 2026, 16, 77. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom16010077

Manna OM, Malizia V, Perri A, La Grutta S, Fucarino A, Picone D, Profita M, Bucchieri F, Rappa F, Gagliardo R. Crystalline Insights into Nasal Mucosa Inflammation and Remodeling: Unveiling Role of Galectin-10. Biomolecules. 2026; 16(1):77. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom16010077

Chicago/Turabian StyleManna, Olga Maria, Velia Malizia, Andrea Perri, Stefania La Grutta, Alberto Fucarino, Domiziana Picone, Mirella Profita, Fabio Bucchieri, Francesca Rappa, and Rosalia Gagliardo. 2026. "Crystalline Insights into Nasal Mucosa Inflammation and Remodeling: Unveiling Role of Galectin-10" Biomolecules 16, no. 1: 77. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom16010077

APA StyleManna, O. M., Malizia, V., Perri, A., La Grutta, S., Fucarino, A., Picone, D., Profita, M., Bucchieri, F., Rappa, F., & Gagliardo, R. (2026). Crystalline Insights into Nasal Mucosa Inflammation and Remodeling: Unveiling Role of Galectin-10. Biomolecules, 16(1), 77. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom16010077