Cannabidiol Mitigates Pollution-Induced Inflammatory, Oxidative, and Barrier Damage in Ex Vivo Human Skin

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Human Ex Vivo Skin Model Preparation

2.2. PM Dose Optimization Study

2.3. CBD Concentration Selection Study

2.4. Assessment of Anti-Pollution Effects of CBD

2.5. Tissue Viability Assessment Using MTT Assay

2.6. Quantification of IL-6, MMP-1, ROS, 8-OHdG, and PIP in Culture Medium

2.7. Immunofluorescence Staining of COX-2, AhR, Fibrillin, Filaggrin, and Collagen Type I

2.8. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Establishment of a PM-Induced Skin Damage Model

3.2. Optimization of CBD Concentration

3.3. CBD Suppresses PM-Induced IL-6 and MMP-1 Expression in Human Skin Explants

3.4. CBD Attenuates PM-Induced COX-2 Expression in Human Skin Explants

3.5. CBD Reduces PM-Induced Oxidative Stress in Human Skin Explants

3.6. CBD Attenuates PM-Induced Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor (AhR) Expression in Human Skin Explants

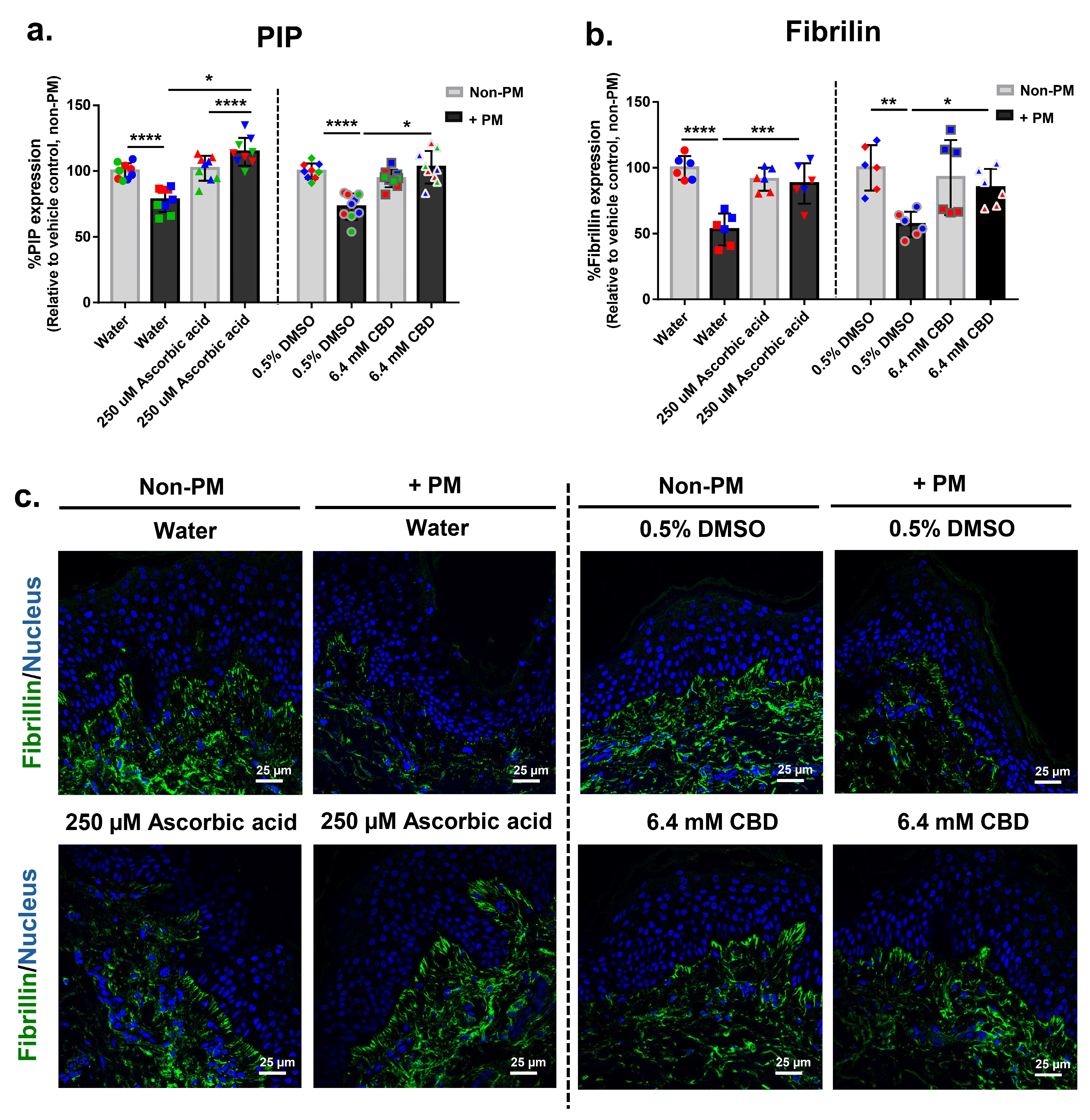

3.7. CBD Restores PM-Induced Decline in Extracellular Matrix Markers PIP and Fibrillin in Human Skin Explants

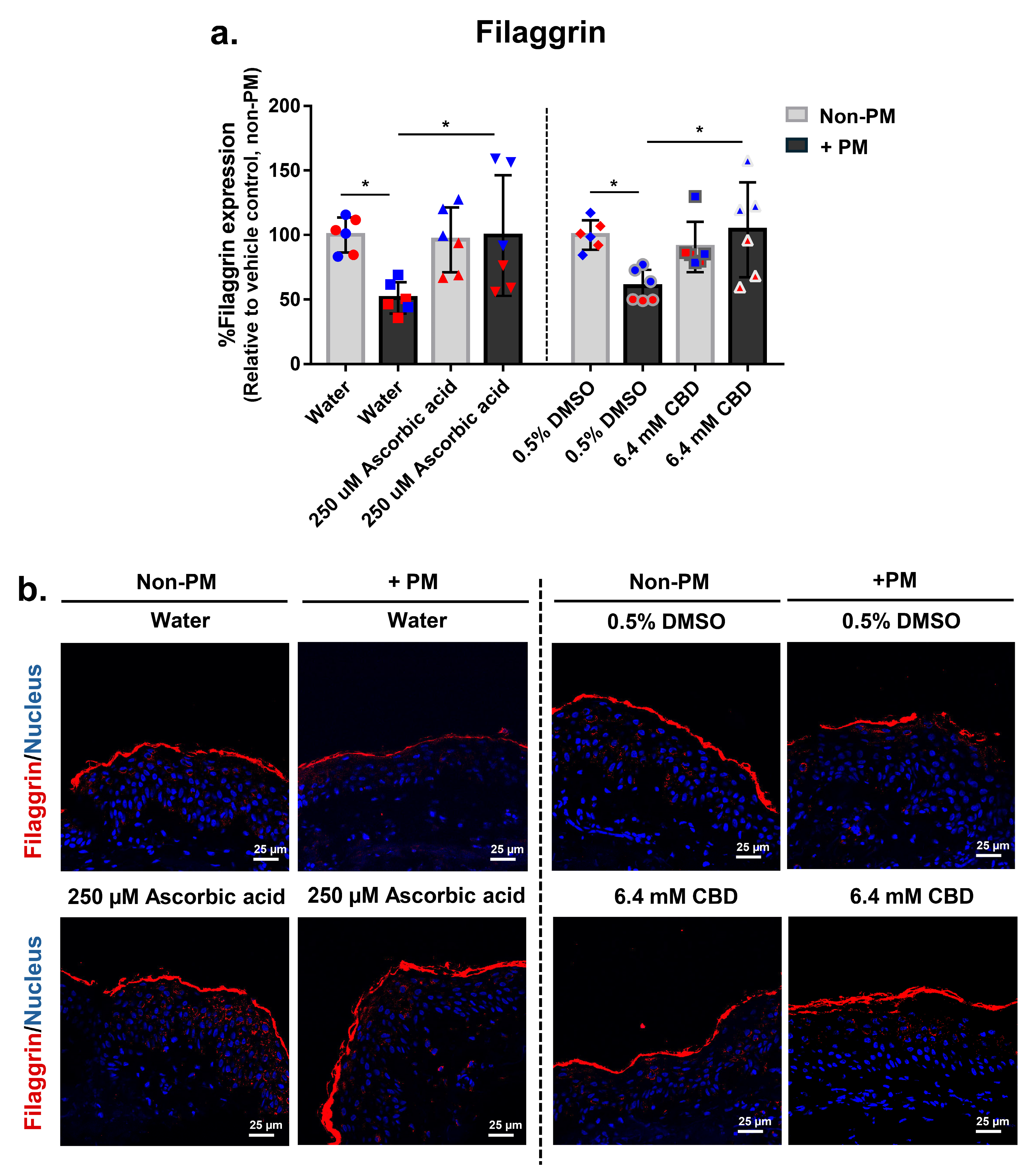

3.8. CBD Restores PM-Induced Loss of Filaggrin Expression in Human Skin Explants

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Araviiskaia, E.; Berardesca, E.; Bieber, T.; Gontijo, G.; Sanchez Viera, M.; Marrot, L.; Chuberre, B.; Dreno, B. The impact of airborne pollution on skin. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2019, 33, 1496–1505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menichini, E. Urban air pollution by polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons: Levels and sources of variability. Sci. Total Environ. 1992, 116, 109–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krutmann, J.; Liu, W.; Li, L.; Pan, X.; Crawford, M.; Sore, G.; Seite, S. Pollution and skin: From epidemiological and mechanistic studies to clinical implications. J. Dermatol. Sci. 2014, 76, 163–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poljšak, B.; Dahmane, R. Free radicals and extrinsic skin aging. Dermatol. Res. Pract. 2012, 2012, 135206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rembiesa, J.; Ruzgas, T.; Engblom, J.; Holefors, A. The impact of pollution on skin and proper efficacy testing for anti-pollution claims. Cosmetics 2018, 5, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Lee, W.; Cui, Y.R.; Ahn, G.; Jeon, Y.-J. Protective effect of green tea catechin against urban fine dust particle-induced skin aging by regulation of NF-κB, AP-1, and MAPKs signaling pathways. Environ. Pollut. 2019, 252, 1318–1324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Gallego, N.; Sánchez-Madrid, F.; Cibrian, D. Role of AHR ligands in skin homeostasis and cutaneous inflammation. Cells 2021, 10, 3176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paik, K.; Na, J.-I.; Huh, C.-H.; Shin, J.-W. Particulate matter and its molecular effects on skin: Implications for various skin diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 9888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, B.E.; Kim, J.; Goleva, E.; Berdyshev, E.; Lee, J.; Vang, K.A.; Lee, U.H.; Han, S.; Leung, S.; Hall, C.F.; et al. Particulate matter causes skin barrier dysfunction. JCI Insight 2021, 6, e145185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, S.Y.; Byun, E.J.; Lee, J.D.; Kim, S.; Kim, H.S. Air pollution, autophagy, and skin aging: Impact of particulate matter (PM10) on human dermal fibroblasts. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 2727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juliano, C.; Magrini, G.A. Cosmetic functional ingredients from botanical sources for anti-pollution skincare products. Cosmetics 2018, 5, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marrot, L. Pollution and sun exposure: A deleterious synergy. Mechanisms and opportunities for skin protection. Curr. Med. Chem. 2018, 25, 5469–5486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nobile, V.; Schiano, I.; Peral, A.; Giardina, S.; Spartà, E.; Caturla, N. Antioxidant and reduced skin-ageing effects of a polyphenol-enriched dietary supplement in response to air pollution: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Food Nutr. Res. 2021, 65, 5524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caturla Cernuda, N.; Peral, A.; Monteloeder, S.L. Composition Comprising Vegetable Extracts with Flavonoids for Alleviating the Many Effects of Air Pollution on the Skin. Patent No. WO2019211501A1, 7 November 2019. [Google Scholar]

- De Wever, B.; Kandarova, H.; Descargues, P. Human skin models for research applications in pharmacology and toxicology: Introducing NativeSkin®, the “missing link” bridging cell culture and/or reconstructed skin models and human clinical testing. Appl. Vitr. Toxicol. 2015, 1, 26–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, H.I.; Won, C.H.; Chang, S.; Lee, M.W.; Park, G. Usefulness and limitations of skin explants to assess laser treatment. Med. Lasers 2013, 2, 58–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Netzlaff, F.; Lehr, C.M.; Wertz, P.W.; Schaefer, U.F. The human epidermis models EpiSkin, SkinEthic and EpiDerm: An evaluation of morphology and their suitability for testing phototoxicity, irritancy, corrosivity, and substance transport. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2005, 60, 167–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Companjen, A.R.; van der Wel, L.I.; Wei, L.; Laman, J.D.; Prens, E.P. A modified ex vivo skin organ culture system for functional studies. Arch. Dermatol. Res. 2001, 293, 184–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuzumi, A.; Yoshizaki-Ogawa, A.; Fukasawa, T.; Sato, S.; Yoshizaki, A. The potential role of cannabidiol in cosmetic dermatology: A literature review. Am. J. Clin. Dermatol. 2024, 25, 951–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tassaneesuwan, N.; Khongkow, M.; Jansrinual, S.; Khongkow, P. Discovering the potential of cannabidiol for cosmeceutical development at the cellular level. Pharmaceuticals 2025, 18, 202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Cannabidiol (CBD): Critical review report. In Forty-First Meeting of the Expert Committee on Drug Dependence; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Luz-Veiga, M.; Mendes, A.; Tavares-Valente, D.; Amorim, M.; Conde, A.; Pintado, M.E.; Moreira, H.R.; Azevedo-Silva, J.; Fernandes, J. Exploring cannabidiol (CBD) and cannabigerol (CBG) safety profile and skincare potential. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 12224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vučković, S.; Srebro, D.; Vujović, K.S.; Vučetić, Č.; Prostran, M. Cannabinoids and pain: New insights from old molecules. Front. Pharmacol. 2018, 9, 1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pertwee, R.G. Cannabinoid pharmacology: The first 66 years. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2006, 147, S163–S171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casares, L.; García, V.; Garrido-Rodríguez, M.; Millán, E.; Collado, J.A.; García-Martín, A.; Peñarando, J.; Calzado, M.A.; de la Vega, L.; Muñoz, E. Cannabidiol induces antioxidant pathways in keratinocytes by targeting BACH1. Redox Biol. 2020, 28, 101321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrosino, S.; Verde, R.; Vaia, M.; Allarà, M.; Iuvone, T.; Di Marzo, V. Anti-inflammatory properties of cannabidiol, a nonpsychotropic cannabinoid, in experimental allergic contact dermatitis. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2018, 365, 652–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jastrząb, A.; Gęgotek, A.; Skrzydlewska, E. Cannabidiol regulates the expression of keratinocyte proteins involved in the inflammation process through transcriptional regulation. Cells 2019, 8, 827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atalay, S.; Dobrzyńska, I.; Gęgotek, A.; Skrzydlewska, E. Cannabidiol protects keratinocyte cell membranes following exposure to UVB and hydrogen peroxide. Redox Biol. 2020, 36, 101613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martins, A.M.; Gomes, A.L.; Vilas Boas, I.; Marto, J.; Ribeiro, H.M. Cannabis-based products for the treatment of skin inflammatory diseases: A timely review. Pharmaceuticals 2022, 15, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, Y.S.; Jeong, S.; Kim, A.R.; Mok, B.R.; Son, S.J.; Ryu, J.S.; Son, W.S.; Yun, S.K.; Kang, S.; Kim, H.J.; et al. Cannabidiol mediates epidermal terminal differentiation and redox homeostasis through aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR)-dependent signaling. J. Dermatol. Sci. 2023, 109, 61–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leite, M.N.; Viegas, J.S.R.; Praça, F.S.G.; de Paula, N.A.; Ramalho, L.N.Z.; Bentley, M.V.L.B.; Frade, M.A.C. Ex vivo model of human skin (hOSEC) for assessing the dermatokinetics of the anti-melanoma drug dacarbazine. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2021, 160, 105769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asserin, J.; Lati, E.; Shioya, T.; Prawitt, J. The effect of oral collagen peptide supplementation on skin moisture and the dermal collagen network: Evidence from an ex vivo model and randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trials. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2015, 14, 291–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Namchantra, K.; Wongwanakul, R.; Klinngam, W. Effects of culture medium-based and topical anti-pollution treatments on PM-induced skin damage using a human ex vivo model. Cosmetics 2025, 12, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moskot, M.; Jakóbkiewicz-Banecka, J.; Kloska, A.; Piotrowska, E.; Narajczyk, M.; Gabig-Cimińska, M. The role of dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) in gene expression modulation and glycosaminoglycan metabolism in lysosomal storage disorders on an example of mucopolysaccharidosis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gęgotek, A.; Mucha, M.; Skrzydlewska, E. Skin cells protection against UVA radiation—The comparison of various antioxidants and viability tests. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2024, 181, 117736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bocheva, G.; Slominski, R.M.; Slominski, A.T. Environmental air pollutants affecting skin functions with systemic implications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 10502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hieda, D.S.; Anastacio da Costa Carvalho, L.; Vaz de Mello, B.; Oliveira, E.A.; Romano de Assis, S.; Wu, J.; Du-Thumm, L.; Viana da Silva, C.L.; Roubicek, D.A.; Maria-Engler, S.S.; et al. Air particulate matter induces skin barrier dysfunction and water transport alteration on a reconstructed human epidermis model. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2020, 140, 2343–2352.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, C.W.; Lin, Z.C.; Hu, S.C.; Chiang, Y.C.; Hsu, L.F.; Lin, Y.C.; Lee, I.T.; Tsai, M.H.; Fang, J.Y. Urban particulate matter down-regulates filaggrin via COX-2 expression/PGE2 production leading to skin barrier dysfunction. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 27995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piao, M.J.; Ahn, M.J.; Kang, K.A.; Ryu, Y.S.; Hyun, Y.J.; Shilnikova, K.; Zhen, A.X.; Jeong, J.W.; Choi, Y.H.; Kang, H.K.; et al. Particulate matter 2.5 damages skin cells by inducing oxidative stress, subcellular organelle dysfunction, and apoptosis. Arch. Toxicol. 2018, 92, 2077–2091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dijkhoff, I.M.; Drasler, B.; Karakocak, B.B.; Petri-Fink, A.; Valacchi, G.; Eeman, M.; Rothen-Rutishauser, B. Impact of airborne particulate matter on skin: A systematic review from epidemiology to in vitro studies. Part. Fibre Toxicol. 2020, 17, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheau, C.; Caruntu, C.; Badarau, I.A.; Scheau, A.E.; Docea, A.O.; Calina, D.; Caruntu, A. Cannabinoids and inflammations of the gut–lung–skin barrier. J. Pers. Med. 2021, 11, 494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivesind, T.E.; Maghfour, J.; Rietcheck, H.; Kamel, K.; Malik, A.S.; Dellavalle, R.P. Cannabinoids for the treatment of dermatologic conditions. JID Innov. 2022, 2, 100095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baswan, S.M.; Klosner, A.E.; Glynn, K.; Rajgopal, A.; Malik, K.; Yim, S.; Stern, N. Therapeutic potential of cannabidiol (CBD) for skin health and disorders. Clin. Cosmet. Investig. Dermatol. 2020, 13, 927–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seltzer, E.S.; Watters, A.K.; MacKenzie, D., Jr.; Granat, L.M.; Zhang, D. Cannabidiol (CBD) as a promising anti-cancer drug. Cancers 2020, 12, 3203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, S.R.; Hackett, B.; O’Driscoll, D.N.; Sun, M.C.; Downer, E.J. Cannabidiol modulation of oxidative stress and signalling. Neuronal Signal. 2021, 5, NS20200080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safe, S.; Jin, U.H.; Park, H.; Chapkin, R.S.; Jayaraman, A. Aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AHR) ligands as selective AHR modulators (SAhRMs). Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 6654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rusu, A.; Farcaș, A.-M.; Oancea, O.-L.; Tanase, C. Cannabidiol in skin health: A comprehensive review of topical applications in dermatology and cosmetic science. Biomolecules 2025, 15, 1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, G.; Jakus, J.; Portillo, M.; Gvirtz, R.; Ogen-Shtern, N.; Silberstein, E.; Ayzenberg, T.; Rozenblat, S. In vitro, ex vivo, and clinical evaluation of anti-aging gel containing EPA and CBD. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2023, 22, 3047–3057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, M.; Son, D.; Shin, S.; Park, D.; Byun, S.; Jung, E. Protective effects of Camellia japonica flower extract against urban air pollutants. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2019, 19, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kahremany, S.; Hofmann, L.; Eretz-Kdosha, N.; Silberstein, E.; Gruzman, A.; Cohen, G. SH-29 and SK-119 attenuate air-pollution-induced damage by activating Nrf2 in HaCaT cells. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 12371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bielfeldt, S.; Jung, K.; Laing, S.; Moga, A.; Wilhelm, K.P. Anti-pollution effects of two antioxidants and a chelator—Ex vivo electron spin resonance and in vivo cigarette smoke model assessments in human skin. Skin Res. Technol. 2021, 27, 1092–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varadi, G.; Zhu, Z.; Crowley, H.D.; Moulin, M.; Dey, R.; Lewis, E.D.; Evans, M. Examining the systemic bioavailability of cannabidiol and tetrahydrocannabinol from a novel transdermal delivery system in healthy adults: A single-arm, open-label, exploratory study. Adv. Ther. 2023, 40, 282–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sitovs, A.; Logviss, K.; Lauberte, L.; Mohylyuk, V. Oral delivery of cannabidiol: Revealing the formulation and absorption challenges. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2024, 92, 105316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, T.; Jackson, S.; Haycock, J.W.; MacNeil, S. Culture of skin cells in 3D rather than 2D improves their ability to survive exposure to cytotoxic agents. J. Biotechnol. 2006, 122, 372–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neubert, R.H.H. Mechanisms of penetration and diffusion of drugs and cosmetic actives across the human stratum corneum. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2024, 202, 114394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larson, P.J.; Chong, D.; Fleming, E.; Oh, J. Challenges in developing a human model system for skin microbiome research. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2021, 141, 228–231.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neves, L.M.G.; Wilgus, T.A.; Bayat, A. In vitro, ex vivo, and in vivo approaches for investigation of skin scarring: Human and animal models. Adv. Wound Care 2023, 12, 97–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofmann, E.; Fink, J.; Eberl, A.; Prugger, E.-M.; Kolb, D.; Luze, H.; Schwingenschuh, S.; Birngruber, T.; Magnes, C.; Mautner, S.I.; et al. A novel human ex vivo skin model to study early local responses to burn injuries. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scientific Committee on Consumer Safety (SCCS). Scientific Opinion on Cannabidiol (CBD) (CAS/EC No. 13956-29-1/689-176-3) used in cosmetic products. In SCCS/1657/23 Final Opinion; European Commission, Scientific Committee on Consumer Safety: Brussels, Belgium, 2025. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Klinngam, W.; Loruthai, O.; Vimolmangkang, S. Cannabidiol Mitigates Pollution-Induced Inflammatory, Oxidative, and Barrier Damage in Ex Vivo Human Skin. Biomolecules 2026, 16, 10. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom16010010

Klinngam W, Loruthai O, Vimolmangkang S. Cannabidiol Mitigates Pollution-Induced Inflammatory, Oxidative, and Barrier Damage in Ex Vivo Human Skin. Biomolecules. 2026; 16(1):10. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom16010010

Chicago/Turabian StyleKlinngam, Wannita, Orathai Loruthai, and Sornkanok Vimolmangkang. 2026. "Cannabidiol Mitigates Pollution-Induced Inflammatory, Oxidative, and Barrier Damage in Ex Vivo Human Skin" Biomolecules 16, no. 1: 10. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom16010010

APA StyleKlinngam, W., Loruthai, O., & Vimolmangkang, S. (2026). Cannabidiol Mitigates Pollution-Induced Inflammatory, Oxidative, and Barrier Damage in Ex Vivo Human Skin. Biomolecules, 16(1), 10. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom16010010