An Integrated Systems Pharmacology Approach Combining Bioinformatics, Untargeted Metabolomics and Molecular Dynamics to Unveil the Anti-Aging Mechanisms of Tephroseris flammea

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Preparation of Tephroseris flammea (Turcz. ex DC.) Holub. Whole Plant Extract

2.2. UHPLC–MS/MS Analysis and Metabolite Identification

2.2.1. UHPLC–MS/MS Analysis of T. flammea Extract

2.2.2. Metabolite Identification

2.3. Reference-Based Identification of Potential Targets for Skin Aging

2.4. Metabolite Screening and Compound–Protein Interaction (CPI) Partner Prediction

2.5. Network Pharmacology

2.5.1. Protein–Protein Interaction Network Construction

2.5.2. Pathway Enrichment Analysis

2.6. Molecular Dynamics

2.6.1. Protein Structure Preparation

2.6.2. Molecular Docking

- Selection of the region corresponding to the DNA-binding interface, and

- Identification of potential druggable pockets using the SiteMap module in Maestro.

2.6.3. MD Simulation

2.7. Experimental Validation

2.7.1. MTT Viability Assay

2.7.2. Radical Scavenging Assay

2.7.3. Anti-Inflammatory Activity Assay

2.7.4. Anti-Photoaging Effect Assessment (MMP-1 Assay)

3. Results

3.1. Metabolite Profiling of T. flammea Extract Using UHPLC-MS/MS

3.2. Identification and Classification of Putative Bioactive Metabolites

3.3. Identification of Mechanistic Targets Involved in Skin Aging

3.4. Identification of Potential Functional Targets of T. flammea Metabolites

3.5. Network Pharmacology and Pathway Enrichment Analysis

3.6. Molecular Docking and Dynamics Validation

3.6.1. Molecular Docking

3.6.2. MD Simulation

3.7. Experimental Validation

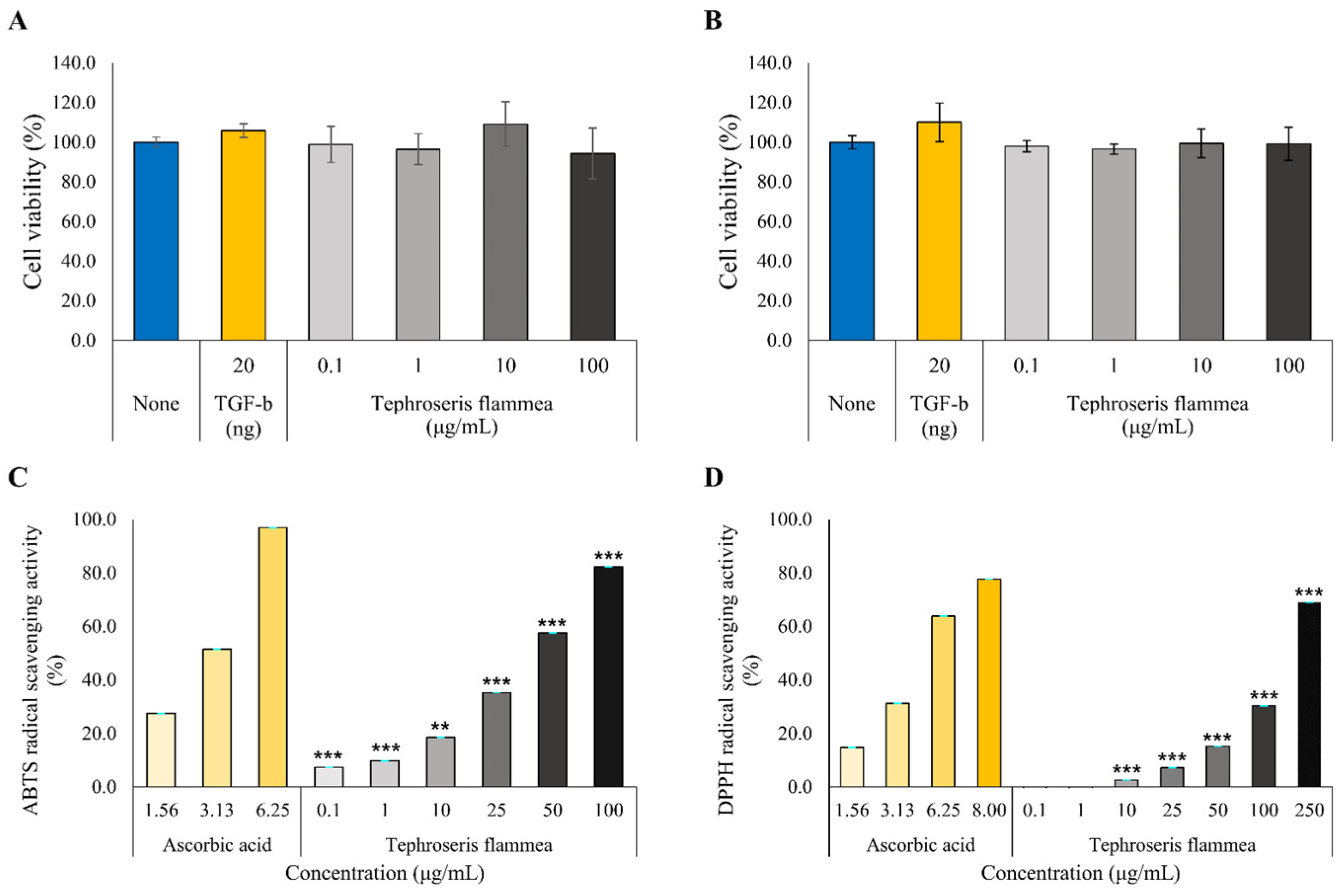

3.7.1. Cell Viability Assessment

3.7.2. Antioxidant Activity Assessment

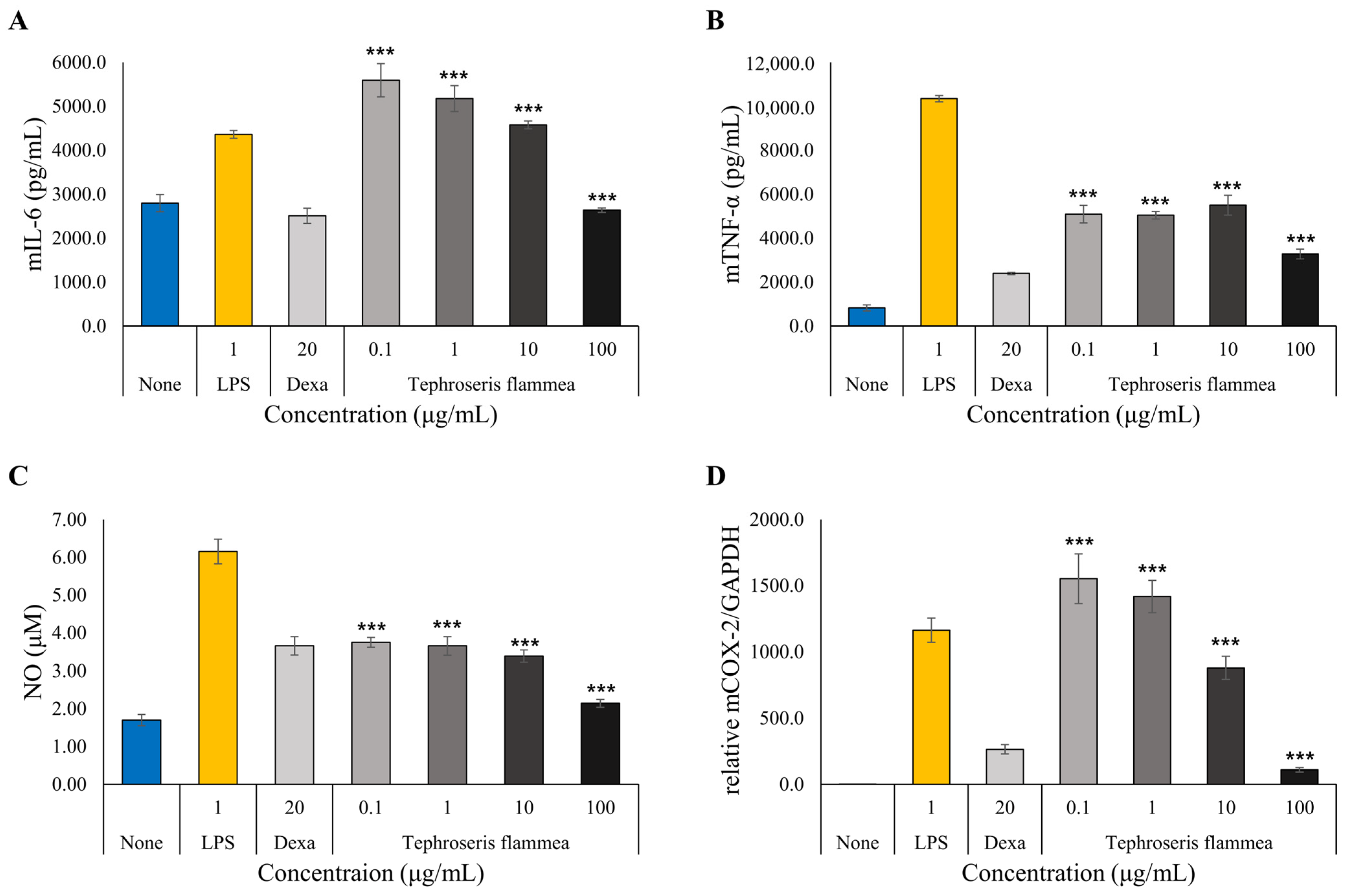

3.7.3. Anti-Inflammatory Activity Assessment

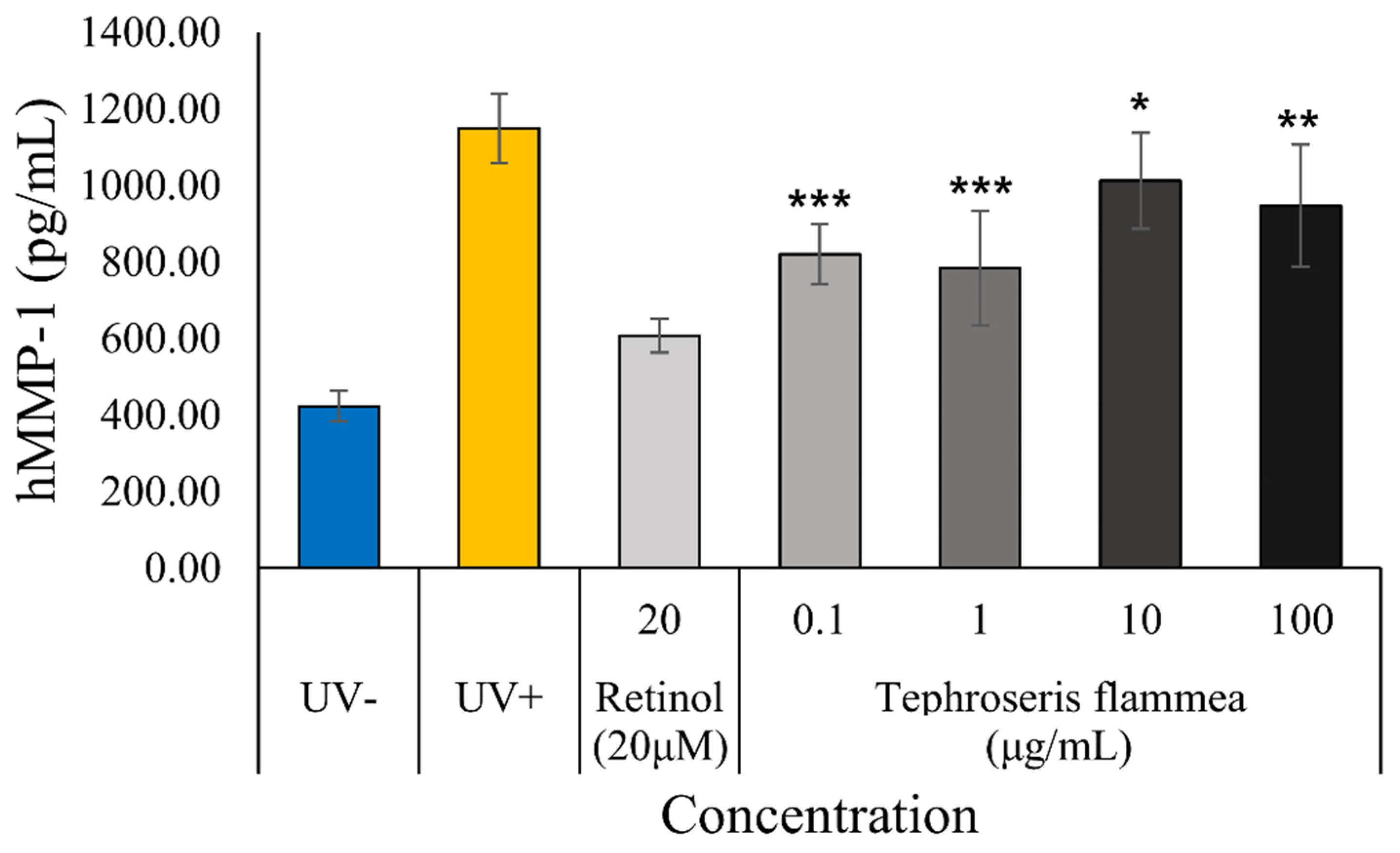

3.7.4. Anti-Photoaging Effect Assessment: Inhibition of MMP-1 Production

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CPI | Compound–protein interaction |

| ECM | Extracellular matrix |

| GO | Gene ontology |

| HDF | Human dermal fibroblast |

| MD | Molecular dynamics |

| NP | Natural product |

| PPI | Protein–protein interaction |

| RMSD | Root mean square distance |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| UHPLC | Ultra high performance liquid chromatography |

| UV | Ultraviolet |

References

- Tobin, D.J. Introduction to skin aging. J. Tissue Viability 2017, 26, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krutmann, J.; Bouloc, A.; Sore, G.; Bernard, B.A.; Passeron, T. The skin aging exposome. J. Dermatol. Sci. 2017, 85, 152–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vrani, J.; Dame, M.K.; Rittie, L.; Fligiel, S.E.; Kang, S.; Fisher, G.J.; Voorhees, J.J. Decreased collagen production in chronologically aged skin: Roles of age-dependent alteration in fibroblast function and defective mechanical stimulation. Am. J. Pathol. 2006, 168, 1861–1868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farage, M.A.; Miller, K.W.; Elsner, P.; Maibach, H.I. Intrinsic and extrinsic factors in skin ageing: A review. Int. J. Cosmet. Sci. 2008, 30, 87–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stout, R.Z.; Birch-Machin, M.A. Mitochondria’s role in skin ageing. Biology 2019, 8, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, G.J.; Kang, S.; Varani, J.; Bata-Csorgo, Z.; Wan, Y.; Datta, S.; Voorhees, J.J. Mechanisms of photoaging and chronological skin aging. Arch. Dermatol. 2002, 138, 1462–1470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pillai, S.; Oresajo, C.; Hayward, J. Ultraviolet radiation and skin aging: Roles of reactive oxygen species, inflammation and protease activation, and strategies for prevention of inflammation-induced matrix degradation. Int. J. Cosmet. Sci. 2005, 27, 17–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rittie, L.; Fisher, G.J. UV-light-induced signal cascades and skin aging. Ageing Res. Rev. 2002, 1, 705–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helfrich, Y.R.; Sachs, D.L.; Voorhees, J.J. Overview of skin aging and photoaging. Dermatol. Nurs. 2008, 20, 177–183. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Andrade, J.; Guerrero, B.V.; Diaz, C.M.G.; Radillo, J.J.V.; Lopez, M.A.R. Natural products and their mechanisms in potential photoprotection of the skin. J. Biosci. 2022, 47, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Narayanan, D.L.; Saladi, R.N.; Fox, J.L. Ultraviolet radiation and skin cancer. Int. J. Dermatol. 2010, 49, 978–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swiader, A.; Camaré, C.; Guerby, P.; Salvayre, R.; Negre-Salvayre, A. 4-Hydroxynonenal Contributes to Fibroblast Senescence in Skin Photoaging Evoked by UV-A Radiation. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, M.A.; Gilchrest, B.A. Psychosocial aspects of aging skin. Dermatol. Clin. 2005, 23, 643–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, L.L.; Lim, H.W.; Mohammad, T.F. Sunscreens and Photoaging: A Review of Current Literature. Am. J. Clin. Dermatol. 2021, 22, 819–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milosheska, D.; Roškar, R. Use of Retinoids in Topical Antiaging Treatments: A Focused Review of Clinical Evidence for Conventional and Nanoformulations. Adv. Ther. 2022, 39, 5351–5375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rostkowska, E.; Poleszak, E.; Wojciechowska, K.; Dos Santos Szewczyk, K. Dermatological Management of Aged Skin. Cosmetics 2023, 10, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, T.; Reker, D.; Schneider, P.; Schneider, G. Counting on natural products for drug design. Nat. Chem. 2016, 8, 531–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, D.J.; Cragg, G.M. Natural products as sources of new drugs over the nearly four decades from 01/1981 to 09/2019. J. Nat. Prod. 2020, 83, 770–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atanasov, A.G.; Zotchev, S.B.; Dirsch, V.M.; International Natural Product Sciences Taskforce; Supuran, C.T. Natural products in drug discovery: Advances and opportunities. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2021, 20, 200–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feher, M.; Schmidt, J.M. Property distributions: Differences between drugs, natural products, and molecules from combinatorial chemistry. J. Chem. Inf. Comput. Sci. 2003, 43, 218–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirkland, J.L.; Tchkonia, T. Senolytic drugs: From discovery to translation. J. Intern. Med. 2020, 288, 518–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saliev, T.; Singh, P.B. Targeting Senescence: A Review of Senolytics and Senomorphics in Anti-Aging Interventions. Biomole-Cules 2025, 15, 860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Houghton, C.A.; Fassett, R.G.; Coombes, J.S. Sulforaphane: Translational research from laboratory bench to clinic. Nutr. Rev. 2013, 71, 709–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, Z.Q.; Zheng, S.Y.; Sun, Z.; Luo, Y.; Wang, Y.T.; Yi, P.; Li, Y.S.; Huang, C.; Xiao, W.F. Resveratrol: Molecular Mechanisms, Health Benefits, and Potential Adverse Effects. MedComm 2025, 6, e70252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, H.; Ulrich-Merzenich, G. Synergy research: Approaching a new generation of phytopharmaceuticals. Phytomedicine 2009, 16, 97–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koeberle, A.; Werz, O. Multi-target engagement by natural products: A novel therapeutic paradigm. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2014, 35, 281–286. [Google Scholar]

- Gaudêncio, S.P.; Pereira, F. Dereplication: Racing to speed up the natural product discovery process. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2015, 32, 779–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najmi, A.; Javed, S.A.; Al Bratty, M.; Alhazmi, H.A. Modern Approaches in the Discovery and Development of Plant-Based Natural Products and Their Analogues as Potential Therapeutic Agents. Molecules 2022, 27, 349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, M.H.; Cho, K.H.; No, K.T. PhyloSophos: A high-throughput scientific name mapping algorithm augmented with explicit consideration of taxonomic science, and its application on natural product (NP) occurrence database processing. BMC Bioinform. 2023, 24, 475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Zhu, X.; Bai, H.; Ning, K. Network pharmacology databases for traditional Chinese medicine: A systematic review. J. Cheminform. 2019, 11, 73. [Google Scholar]

- Cho, M.H. From Data to Discovery: Applying AI and Big Data for Scalable Innovation in Natural Product Research. In Proceedings of the ASNP 2025 The Global Symposium on Natural Products, Jecheon, Republic of Korea, 22–24 September 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Cho, M.H. Utilization of Big Data and AI Methodologies for the Discovery of Functional Natural Products. In Proceedings of the 2024 KFN International Symposium and Annual Meeting, ICC Jeju, Jeju Island, Republic of Korea, 23–25 October 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Editorial Committee of the Flora of China. Flora of China, Vol. 20–21 (Asteraceae); Science Press & Missouri Botanical Garden Press: Beijing, China, 2011; p. 464. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.W.; Hu, J.J.; Fu, R.Q.; Liu, X.; Zhang, Y.H.; Li, J.; Liu, L.; Li, Y.N.; Deng, Q.; Luo, Q.S.; et al. Flavonoids inhibit cell proliferation and induce apoptosis and autophagy through downregulation of PI3Kγ mediated PI3K/AKT/mTOR/p70S6K/ULK signaling pathway in human breast cancer cells. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 11255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schymanski, E.L.; Jeon, J.; Gulde, R.; Fenner, K.; Ruff, M.; Singer, H.P.; Hollender, J. Identifying small molecules via high res-olution mass spectrometry: Communicating confidence. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2014, 48, 2097–2098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wyles, S.P.; Yu, G.T.; Ganier, C.; Tchkonia, T.; Lynch, M.D.; Kuchel, G.A.; Kirkland, J.L. SenSkin™: A human skin-specific cellular senescence gene set. Geroscience 2025, 47, 2631–2638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.; Jin, H.; Kim, J.; Cho, S.Y.; Moon, S.; Wang, J.; Mao, J.; No, K.T. Leveraging the Fragment Molecular Orbital and MM-GBSA Methods in Virtual Screening for the Discovery of Novel Non-Covalent Inhibitors Targeting the TEAD Lipid Binding Pocket. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 5358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Re, R.; Pellegrini, N.; Proteggente, A.; Pannala, A.; Yang, M.; Rice-Evans, C. Antioxidant activity applying an improved ABTS radical cation decolorization assay. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 1999, 26, 1231–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blois, M.S. Antioxidant determinations by the use of a stable free radical. Nature 1958, 181, 1199–1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.W.; Myers, S.P.; Leach, D.N.; Lin, G.D.; Leach, G. Anti-inflammatory activity of Chinese medicinal vine plants. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2003, 85, 61–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.H.; Kumar, S.; Barnett, A.H.; Eggo, M.C. Dexamethasone inhibits tumor necrosis factor-alpha-induced apoptosis and interleukin-1 beta release in human subcutaneous adipocytes and preadipocytes. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2001, 86, 2817–2825. [Google Scholar]

- Calabrese, E.J.; Mattson, M.P. How does hormesis impact biology, toxicology, and medicine? NPJ Aging Mech. Dis. 2017, 3, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vauzour, D. Dietary polyphenols as modulators of brain functions: Biological actions and molecular mechanisms underpinning their beneficial effects. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2012, 2012, 914273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ågren, M.S.; Schnabel, R.; Christensen, L.H.; Mirastschijski, U. Tumor necrosis factor-α-accelerated degradation of type I collagen in human skin is associated with elevated matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)-1 and MMP-3 ex vivo. Eur. J. Cell Biol. 2015, 94, 12–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoshida, M.; Sagawa, N.; Itoh, H.; Yura, S.; Korita, D.; Kakui, K.; Hirota, N.; Sato, T.; Ito, A.; Fujii, S. Nitric oxide increases matrix metalloproteinase-1 production in human uterine cervical fibroblast cells. Mol. Hum. Reprod. 2001, 7, 979–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reunanen, N.; Li, S.P.; Ahonen, M.; Foschi, M.; Han, J.; Kähäri, V.M. Activation of p38 alpha MAPK enhances collagenase-1 (matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)-1) and stromelysin-1 (MMP-3) expression by mRNA stabilization. J. Biol. Chem. 2002, 277, 32360–32368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.C.; Tsai, P.H.; Lin, C.Y.; Cheng, C.H.; Lin, T.H.; Lee, K.P.; Huang, K.Y.; Chen, S.H.; Hwang, J.J.; Kandaswami, C.C.; et al. Impact of flavonoids on matrix metalloproteinase secretion and invadopodia formation in highly invasive A431-III cancer cells. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e71903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zughaibi, T.A.; Suhail, M.; Tarique, M.; Tabrez, S. Targeting PI3K/Akt/mTOR Pathway by Different Flavonoids: A Cancer Chemopreventive Approach. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 12455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, V.; Taine, E.G.; Meng, D.; Cui, T.; Tan, W. Chlorogenic Acid: A Systematic Review on the Biological Functions, Mechanistic Actions, and Therapeutic Potentials. Nutrients 2024, 16, 924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.H.; Wang, J.H.; He, H.P.; Zhou, H.; Yang, X.W.; Li, C.S.; Hao, X.J. Norsesquiterpenoid glucosides and a rhamnoside of pyrrolizidine alkaloid from Tephroseris kirilowii. J. Asian Nat. Prod. Res. 2008, 10, 25–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Li, H.; Zhang, X.L.; Wang, W.; Rashed, M.M.A.; Duan, H.; Li, L.L.; Zhai, K.F. Exploring the anti-skin inflammation substances and mechanism of Paeonia lactiflora Pall. Flower via network pharmacology-HPLC integration. Phytomedicine 2024, 129, 155565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Deng, Q.; Deng, B.; Li, Y.; Fan, G.; Yang, F.; Han, W.; Xu, J.; Chen, X. Comprehensive analysis of Hibisci mutabilis Folium extract’s mechanisms in alleviating UV-induced skin photoaging through enhanced network pharmacology and experimental validation. Front. Pharmacol. 2024, 15, 1431391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neuman, M.G.; Cohen, L.; Opris, M.; Nanau, R.M.; Jeong, H. Hepatotoxicity of Pyrrolizidine Alkaloids. J. Pharm. Pharm. Sci. 2015, 18, 825–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Han, H.; Wang, C.; Zheng, Q.; Chen, H.; Zhang, X.; Hou, R. Hepatotoxicity of Pyrrolizidine Alkaloid Compound Intermedine: Comparison with Other Pyrrolizidine Alkaloids and Its Toxicological Mechanism. Toxins 2021, 13, 849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, T.; Mei, N.; Fu, P.P. Genotoxicity of pyrrolizidine alkaloids. J. Appl. Toxicol. 2010, 30, 183–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Subaie, S.F.; Alowaifeer, A.M.; Mohamed, M.E. Pyrrolizidine Alkaloid Extraction and Analysis: Recent Updates. Foods 2022, 11, 3873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartmann, T.; Witte, L. Chemistry, biology and chemoecology of the pyrrolizidine alkaloids. Alkaloids Chem. Biol. Perspect. 1995, 9, 155–233. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, Y.S.; Qiu, J.; Mu, X.Y.; Qian, Y.Z.; Chen, L. Levels, Toxic Effects, and Risk Assessment of Pyrrolizidine Alkaloids in Foods: A Review. Foods 2024, 13, 536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrmann, M.; Joppe, H.; Schmaus, G. Thesinine-4′-O-beta-D-glucoside the first glycosylated plant pyrrolizidine alkaloid from Borago officinalis. Phytochemistry 2002, 60, 399–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Molecule Name | RT | Monoisotopic Mass | Molecular Formula | Intensity (POS) | Intensity (NEG) |

| Quinic acid | 1.39 | 192.0634 | C7H12O6 | 1.78 × 104 | 4.61 × 106 |

| Lindelofidine (or its chiral isomer) | 1.75 | 141.1154 | C8H15NO | 8.96 × 106 | ND |

| Hydroxybenzoic acid | 6.66 | 138.0317 | C7H6O3 | 1.23 × 103 | 6.01 × 105 |

| Chlorogenic acid | 8.43 | 354.0951 | C16H18O9 | 1.55 × 106 | 4.31 × 106 |

| Angeloylplatinecine | 8.71 | 239.1521 | C13H21NO3 | 6.76 × 107 | ND |

| Rivularine | 8.78 | 237.1365 | C13H19NO3 | 1.02 × 107 | 8.51 × 105 |

| Thesin (thesinine dimer) | 15.43 | 574.3043 | C34H42N2O6 | 7.41 × 106 | 3.61 × 103 |

| Thesinine | 17.17 | 287.1521 | C17H21NO3 | 7.26 × 107 | 1.53 × 106 |

| Rutin | 18.18 | 610.1534 | C27H30O16 | 1.86 × 106 | 2.20 × 106 |

| Luteolin rutinoside | 19.64 | 594.1585 | C27H30O15 | 5.87 × 105 | 9.63 × 105 |

| Kaempferol rutinoside (Nicotiflorin) | 20.96 | 594.1585 | C27H30O15 | 3.64 × 106 | 3.81 × 106 |

| Ferulic acid | 21.41 | 194.0579 | C10H10O4 | ND | 1.09 × 106 |

| Isorhamnetin rutinoside (Narcissin) | 21.57 | 624.1690 | C28H32O16 | 5.95 × 105 | 9.02 × 105 |

| Dicaffeoylquinic acid | 23.3 | 516.1267 | C25H24O12 | 1.93 × 105 | 6.18 × 105 |

| Acacerin glucoside (Tilianin) | 28.02 | 446.1212 | C22H22O10 | 9.81 × 105 | 7.63 × 105 |

| Apigenin | 28.38 | 270.0522 | C15H10O5 | 2.41 × 105 | 6.34 × 105 |

| Luteolin | 28.47 | 286.0477 | C15H10O6 | 1.12 × 105 | 7.78 × 105 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cho, M.H.; Jin, H.; Ha, J.; Chu, S.; An, S. An Integrated Systems Pharmacology Approach Combining Bioinformatics, Untargeted Metabolomics and Molecular Dynamics to Unveil the Anti-Aging Mechanisms of Tephroseris flammea. Biomolecules 2025, 15, 1740. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom15121740

Cho MH, Jin H, Ha J, Chu S, An S. An Integrated Systems Pharmacology Approach Combining Bioinformatics, Untargeted Metabolomics and Molecular Dynamics to Unveil the Anti-Aging Mechanisms of Tephroseris flammea. Biomolecules. 2025; 15(12):1740. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom15121740

Chicago/Turabian StyleCho, Min Hyung, Haiyan Jin, JangHo Ha, SungJune Chu, and SoHee An. 2025. "An Integrated Systems Pharmacology Approach Combining Bioinformatics, Untargeted Metabolomics and Molecular Dynamics to Unveil the Anti-Aging Mechanisms of Tephroseris flammea" Biomolecules 15, no. 12: 1740. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom15121740

APA StyleCho, M. H., Jin, H., Ha, J., Chu, S., & An, S. (2025). An Integrated Systems Pharmacology Approach Combining Bioinformatics, Untargeted Metabolomics and Molecular Dynamics to Unveil the Anti-Aging Mechanisms of Tephroseris flammea. Biomolecules, 15(12), 1740. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom15121740