Interleukin-38 Ameliorates Atherosclerosis by Inhibiting Macrophage M1-like Polarization and Apoptosis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Animals

2.2. Cell Culture

2.3. Body Weights and Plasma Lipid Levels

2.4. Oil Red O Staining and Quantification

2.5. Immunohistochemistry and Immunofluorescence

2.6. Western Blot Analysis

2.7. Flow Cytometry

2.8. Real-Time PCR

2.9. mRNA Sequencing

2.9.1. RNA Isolation and Library Preparation

2.9.2. mRNA Sequencing Analysis Process: RNA Sequencing and Differentially Expressed Genes Analysis

2.10. Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay

2.11. Statistics

3. Results

3.1. IL-38 Alleviates Atherosclerosis and Modulates Plaque Composition

3.2. IL-38 Reduces the Formation of Macrophage-Derived Foam Cells and the Expression of Related Inflammatory Factors

3.3. IL-38 Mitigates Systemic and Atherosclerotic Lesion Inflammation and Decreases M1-like Macrophage Polarization

3.4. IL-38 Diminishes the Polarization of Macrophages Towards M1-like Phenotype

3.5. IL-38 Acts on Multiple Inflammatory Pathways

3.6. IL-38 Inhibits NF-κB Pathway Activity

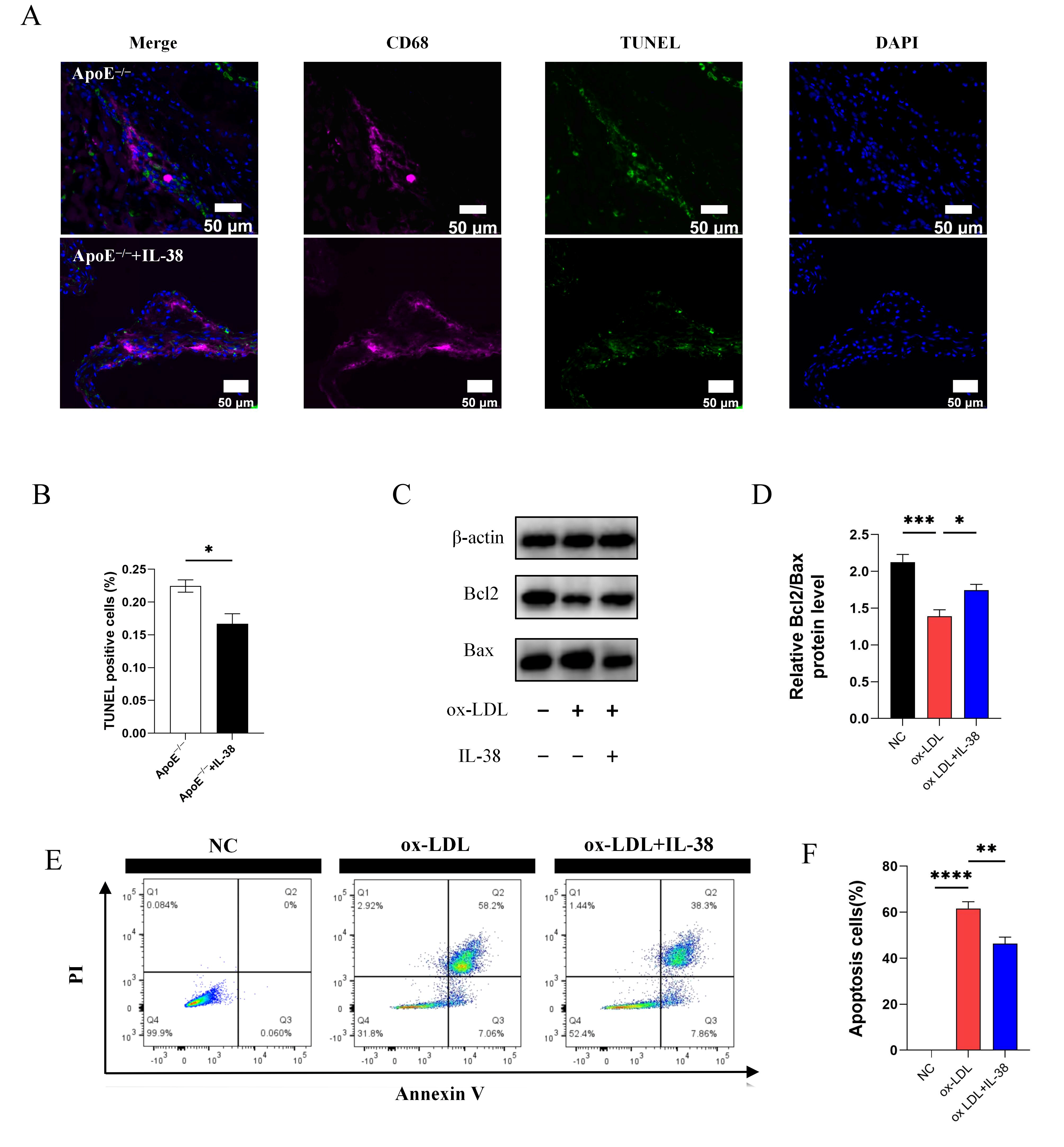

3.7. IL-38 Alleviates Macrophage Apoptosis

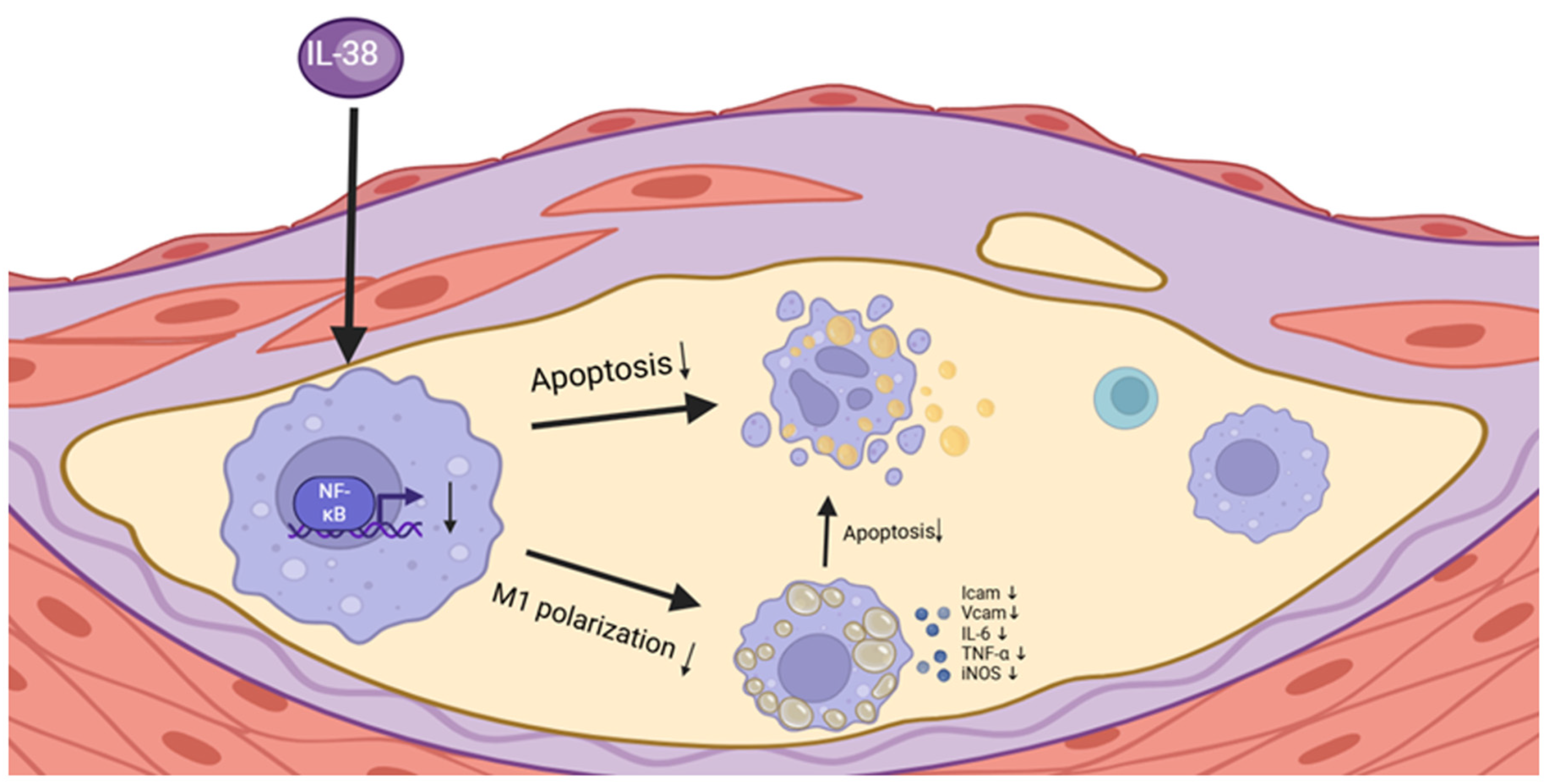

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wang, X.; Ge, J. Atherosclerotic Plaque Healing. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 384, 293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Falk, E. Pathogenesis of atherosclerosis. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2006, 47, C7–C12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansson, G.K.; Hermansson, A. The immune system in atherosclerosis. Nat. Immunol. 2011, 12, 204–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, J.W.; Zaitsev, K.; Kim, K.-W.; Ivanov, S.; Saunders, B.T.; Schrank, P.R.; Kim, K.; Elvington, A.; Kim, S.H.; Tucker, C.G.; et al. Limited proliferation capacity of aortic intima resident macrophages requires monocyte recruitment for atherosclerotic plaque progression. Nat. Immunol. 2020, 21, 1194–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brokopp, C.E.; Schoenauer, R.; Richards, P.; Bauer, S.; Lohmann, C.; Emmert, M.Y.; Weber, B.; Winnik, S.; Aikawa, E.; Graves, K.; et al. Fibroblast activation protein is induced by inflammation and degrades type I collagen in thin-cap fibroatheromata. Eur. Heart J. 2011, 32, 2713–2722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Groh, L.; Keating, S.T.; Joosten, L.A.B.; Netea, M.G.; Riksen, N.P. Monocyte and macrophage immunometabolism in atherosclerosis. Semin. Immunopathol. 2018, 40, 203–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabas, I.; Bornfeldt, K.E. Macrophage Phenotype and Function in Different Stages of Atherosclerosis. Circ. Res. 2016, 118, 653–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosco, M.C. Macrophage polarization: Reaching across the aisle? J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2019, 143, 1348–1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orecchioni, M.; Ghosheh, Y.; Pramod, A.B.; Ley, K. Macrophage Polarization: Different Gene Signatures in M1(LPS+) vs. Classically and M2(LPS-) vs. Alternatively Activated Macrophages. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, F.; Li, J.Z.; Wu, Y.; Wu, W.Y.; Wang, Y.; Li, G. Ubiquitinated ligation protein NEDD4L participates in MiR-30a-5p attenuated atherosclerosis by regulating macrophage polarization and lipid metabolism. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids 2021, 26, 1303–1317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, K.; Shim, D.; Lee, J.S.; Zaitsev, K.; Williams, J.W.; Kim, K.-W.; Jang, M.-Y.; Seok Jang, H.; Yun, T.J.; Lee, S.H.; et al. Transcriptome Analysis Reveals Nonfoamy Rather Than Foamy Plaque Macrophages Are Proinflammatory in Atherosclerotic Murine Models. Circ. Res. 2018, 123, 1127–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolfi, B.; Gallerand, A.; Haschemi, A.; Guinamard, R.R.; Ivanov, S. Macrophage metabolic regulation in atherosclerotic plaque. Atherosclerosis 2021, 334, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, J.J.; Wang, H.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, T.J.; Wei, H.L.; Liu, Z.K.; Ma, Y.H.; Yang, Z.; He, Q.; Wang, L.J.; et al. CD147 Sparks Atherosclerosis by Driving M1 Phenotype and Impairing Efferocytosis. Circ. Res. 2024, 134, 165–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tabas, I. Macrophage Apoptosis in Atherosclerosis: Consequences on Plaque Progression and the Role of Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2009, 11, 2333–2339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simion, V.; Zhou, H.; Haemmig, S.; Pierce, J.B.; Mendes, S.; Tesmenitsky, Y.; Perez-Cremades, D.; Lee, J.F.; Chen, A.F.; Ronda, N.; et al. A macrophage-specific lncRNA regulates apoptosis and atherosclerosis by tethering HuR in the nucleus. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 6135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, L.; Trigatti, B.L. Macrophage Apoptosis and Necrotic Core Development in Atherosclerosis: A Rapidly Advancing Field with Clinical Relevance to Imaging and Therapy. Can. J. Cardiol. 2017, 33, 303–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akdis, M.; Aab, A.; Altunbulakli, C.; Azkur, K.; Costa, R.A.; Crameri, R.; Duan, S.; Eiwegger, T.; Eljaszewicz, A.; Ferstl, R.; et al. Interleukins (from IL-1 to IL-38), interferons, transforming growth factor beta, and TNF-alpha: Receptors, functions, and roles in diseases. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2016, 138, 984–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, P.; Du, M.; Sun, Q.; Zhao, T.; He, H. IL-38 suppresses macrophage M1 polarization to ameliorate synovial inflammation in the TMJ via GLUT-1 inhibition. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2023, 122, 110619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinarello, A.; May, M.; Amo-Aparicio, J.; Azam, T.; Gaballa, J.M.; Marchetti, C.; Tesoriere, A.; Ghirardo, R.; Redzic, J.S.; Webber, W.S., 3rd; et al. IL-38 regulates intestinal stem cell homeostasis by inducing WNT signaling and beneficial IL-1beta secretion. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2023, 120, e2306476120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boutet, M.A.; Najm, A.; Bart, G.; Brion, R.; Touchais, S.; Trichet, V.; Layrolle, P.; Gabay, C.; Palmer, G.; Blanchard, F.; et al. IL-38 overexpression induces anti-inflammatory effects in mice arthritis models and in human macrophages in vitro. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2017, 76, 1304–1312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garraud, T.; Harel, M.; Boutet, M.A.; Le Goff, B.; Blanchard, F. The enigmatic role of IL-38 in inflammatory diseases. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2018, 39, 26–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, Y.; Yu, K.; Wang, X.; Wang, X.; Ji, Q.; Zeng, Q. Elevated Plasma IL-38 Concentrations in Patients with Acute ST-Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction and Their Dynamics after Reperfusion Treatment. Mediat. Inflamm. 2015, 2015, 490120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.H.; Li, Y.; Zhou, L.; Tian, G.P. Interleukin-38 in atherosclerosis. Clin. Chim. Acta 2022, 536, 86–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, Y.; Lan, Y.; Zhong, Y.; Yu, K.; Xu, W.; Zhu, R.; Sun, H.; Ding, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zeng, Q. Interleukin-38 alleviates cardiac remodelling after myocardial infarction. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2020, 24, 371–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ge, Y.; Chen, J.; Hu, Y.; Chen, X.; Huang, M. IL-38 Alleviates Inflammation in Sepsis in Mice by Inhibiting Macrophage Apoptosis and Activation of the NLRP3 Inflammasome. Mediat. Inflamm. 2021, 2021, 6370911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, X.; Hou, T.; Cheung, E.; Iu, T.N.; Tam, V.W.; Chu, I.M.; Tsang, M.S.; Chan, P.K.; Lam, C.W.; Wong, C.K. Anti-inflammatory mechanisms of the novel cytokine interleukin-38 in allergic asthma. Cell. Mol. Immunol. 2020, 17, 631–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chistiakov, D.A.; Bobryshev, Y.V.; Orekhov, A.N. Macrophage-mediated cholesterol handling in atherosclerosis. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2016, 20, 17–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.L.; Cho, W.; Oh, H.; Abd El-Aty, A.M.; Hong, S.A.; Jeong, J.H.; Jung, T.W. Interleukin-38 alleviates hepatic steatosis through AMPK/autophagy-mediated suppression of endoplasmic reticulum stress in obesity models. J. Cell. Physiol. 2024, 239, e31184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Back, M.; Yurdagul, A., Jr.; Tabas, I.; Oorni, K.; Kovanen, P.T. Inflammation and its resolution in atherosclerosis: Mediators and therapeutic opportunities. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2019, 16, 389–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmarasi, M.; Elmakaty, I.; Elsayed, B.; Elsayed, A.; Zein, J.A.; Boudaka, A.; Eid, A.H. Phenotypic switching of vascular smooth muscle cells in atherosclerosis, hypertension, and aortic dissection. J. Cell. Physiol. 2024, 239, e31200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.X.; Ma, X.F.; Xiong, W.H.; Ren, Z.; Jiang, M.; Deng, N.H.; Zhou, B.B.; Liu, H.T.; Zhou, K.; Hu, H.J.; et al. TRIM65 promotes vascular smooth muscle cell phenotypic transformation by activating PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling during atherogenesis. Atherosclerosis 2023, 390, 117430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harber, K.J.; Neele, A.E.; van Roomen, C.P.; Gijbels, M.J.; Beckers, L.; Toom, M.D.; Schomakers, B.V.; Heister, D.A.; Willemsen, L.; Griffith, G.R.; et al. Targeting the ACOD1-itaconate axis stabilizes atherosclerotic plaques. Redox Biol. 2024, 70, 103054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cybulsky, M.I.; Iiyama, K.; Li, H.; Zhu, S.; Milstone, D.S. A major role for VCAM-1, but not ICAM-1, in early atherosclerosis. J. Clin. Investig. 2001, 107, 1255–1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madonna, R.; Barachini, S.; Ghelardoni, S.; Lu, L.; Shen, W.F.; De Caterina, R. Vasostatins: New molecular targets for atherosclerosis, post-ischemic angiogenesis and arteriogenesis. Cardiovasc. Res. 2024, 120, 132–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaipersad, A.S.; Lip, G.Y.; Silverman, S.; Shantsila, E. The role of monocytes in angiogenesis and atherosclerosis. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2014, 63, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Lu, C.; Liu, Y.; Zhou, X.; Sun, L.; Gu, Q.; Shen, G.; Guo, A. Hyperbaric Oxygen Alleviates the Inflammatory Response Induced by LPS Through Inhibition of NF-kB/MAPKs-CCL2/CXCL1 Signaling Pathway in Cultured Astrocytes. Inflammation 2018, 41, 2003–2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Cao, Z.; Wang, L.; Liu, C.; Lin, H.; Tang, Y.; Yao, P. Macrophage Subsets and Death Are Responsible for Atherosclerotic Plaque Formation. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 843712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, H.; Wang, H.; Li, Q.; Wang, Y.; He, Y.; Li, X.; Sun, C.; Ergonul, O.; Can, F.; Pang, Z.; et al. LPS adsorption and inflammation alleviation by polymyxin B-modified liposomes for atherosclerosis treatment. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 2023, 13, 3817–3833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, T.; Ding, L.; Wang, Y.; Yang, O.; Wang, S.; Kong, J. Genetic deficiency of Phactr1 promotes atherosclerosis development via facilitating M1 macrophage polarization and foam cell formation. Clin. Sci. 2020, 134, 2353–2368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, N.; Tan, R.P.; Chan, A.H.P.; Lee, B.S.L.; Bao, S. Immobilized Macrophage Colony-Stimulating Factor (M-CSF) Regulates the Foreign Body Response to Implanted Materials. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2020, 6, 995–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Li, J.; Luo, S.; Wang, M.; Huang, Q.; Deng, Z.; de Febbo, C.; Daoui, A.; Liew, P.X.; Sukhova, G.K.; et al. IgE Contributes to Atherosclerosis and Obesity by Affecting Macrophage Polarization, Macrophage Protein Network, and Foam Cell Formation. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2020, 40, 597–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Li, Y.; Chen, Q.; Wang, T.; Ma, L.; Zhang, W.; Yu, R.; Zhang, J.; Wan, J.; Yu, C.; et al. Sialic acids promote macrophage M1 polarization and atherosclerosis by upregulating ROS and autophagy blockage. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2023, 120, 110410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Tan, Z.; Yang, J.; Li, L.; Li, H.; Zhang, H.; Liu, H.; Liu, Y.; Wang, L.; Li, Q.; et al. Perfluorooctane sulfonate promotes atherosclerosis by modulating M1 polarization of macrophages through the NF-kB pathway. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2023, 249, 114384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Du, H.; Li, X. Artesunate attenuates atherosclerosis by inhibiting macrophage M1-like polarization and improving metabolism. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2022, 102, 108413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Q.; Song, C.; Chen, X.; Xiong, Y.; Li, L.; Liao, W.; Xue, L.; Yang, S. FKBP5 deficiency attenuates calcium oxalate kidney stone formation by suppressing cell-crystal adhesion, apoptosis and macrophage M1 polarization via inhibition of NF-kB signaling. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2023, 80, 301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pei, C.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, P.; Zhang, B.; Fang, L.; Liu, B.; Meng, S. Berberine alleviates oxidized low-density lipoprotein-induced macrophage activation by downregulating galectin-3 via the NF-kB and AMPK signaling pathways. Phytother. Res. 2019, 33, 294–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seimon, T.; Tabas, I. Mechanisms and consequences of macrophage apoptosis in atherosclerosis. J. Lipid Res. 2009, 50, S382–S387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coornaert, I.; Puylaert, P.; Marcasolli, G.; Grootaert, M.O.J.; Vandenabeele, P.; De Meyer, G.R.Y.; Martinet, W. Impact of myeloid RIPK1 gene deletion on atherogenesis in ApoE-deficient mice. Atherosclerosis 2021, 322, 51–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Meyer, G.R.Y.; Zurek, M.; Puylaert, P.; Martinet, W. Programmed death of macrophages in atherosclerosis: Mechanisms and therapeutic targets. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2024, 21, 312–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doddapattar, P.; Dev, R.; Ghatge, M.; Patel, R.B.; Jain, M.; Dhanesha, N.; Lentz, S.R.; Chauhan, A.K. Myeloid Cell PKM2 Deletion Enhances Efferocytosis and Reduces Atherosclerosis. Circ. Res. 2022, 130, 1289–1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhao, X.; Guo, Y.; Liu, Z.; Wei, S.; Yuan, Q.; Shang, H.; Sang, W.; Cui, S.; Xu, T.; et al. Macrophage ALDH2 (Aldehyde Dehydrogenase 2) Stabilizing Rac2 Is Required for Efferocytosis Internalization and Reduction of Atherosclerosis Development. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2022, 42, 700–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Hu, S.; Li, Y.; Sun, Y.; Xiong, X.; Hu, X.; Chen, J.; Qiu, S. Interleukins and Ischemic Stroke. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 828447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Zhao, Q.; Yue, C.; Yu, J.; Zheng, H.; Hu, J.; Hu, Z.; Zhang, H.; Teng, X.; Liu, X.; et al. Interleukin-38 promotes skin tumorigenesis in an IL-1Rrp2-dependent manner. EMBO Rep. 2022, 23, e53791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mantovani, A.; Dinarello, C.A.; Molgora, M.; Garlanda, C. Interleukin-1 and Related Cytokines in the Regulation of Inflammation and Immunity. Immunity 2019, 50, 778–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, L.; Huang, Z.; Li, H.; Liu, X.; Zheng, S.; Su, W. IL-38: A New Player in Inflammatory Autoimmune Disorders. Biomolecules 2019, 9, 345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, Z.; Li, X.; Shen, R.; Wang, Y.; Yu, J.; Pan, C.; Cai, Y.; Dong, Q.; Yu, K.; Zeng, Q. Interleukin-38 Ameliorates Atherosclerosis by Inhibiting Macrophage M1-like Polarization and Apoptosis. Biomolecules 2025, 15, 1741. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom15121741

Li Z, Li X, Shen R, Wang Y, Yu J, Pan C, Cai Y, Dong Q, Yu K, Zeng Q. Interleukin-38 Ameliorates Atherosclerosis by Inhibiting Macrophage M1-like Polarization and Apoptosis. Biomolecules. 2025; 15(12):1741. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom15121741

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Zhiyang, Xuelian Li, Rui Shen, Yue Wang, Jian Yu, Chengliang Pan, Yifan Cai, Qian Dong, Kunwu Yu, and Qiutang Zeng. 2025. "Interleukin-38 Ameliorates Atherosclerosis by Inhibiting Macrophage M1-like Polarization and Apoptosis" Biomolecules 15, no. 12: 1741. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom15121741

APA StyleLi, Z., Li, X., Shen, R., Wang, Y., Yu, J., Pan, C., Cai, Y., Dong, Q., Yu, K., & Zeng, Q. (2025). Interleukin-38 Ameliorates Atherosclerosis by Inhibiting Macrophage M1-like Polarization and Apoptosis. Biomolecules, 15(12), 1741. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom15121741