Molecular Drivers of Vascular Adaptation in Young Athletes: An Integrative Analysis of Endothelial, Metabolic and Lipoprotein Biomarkers

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

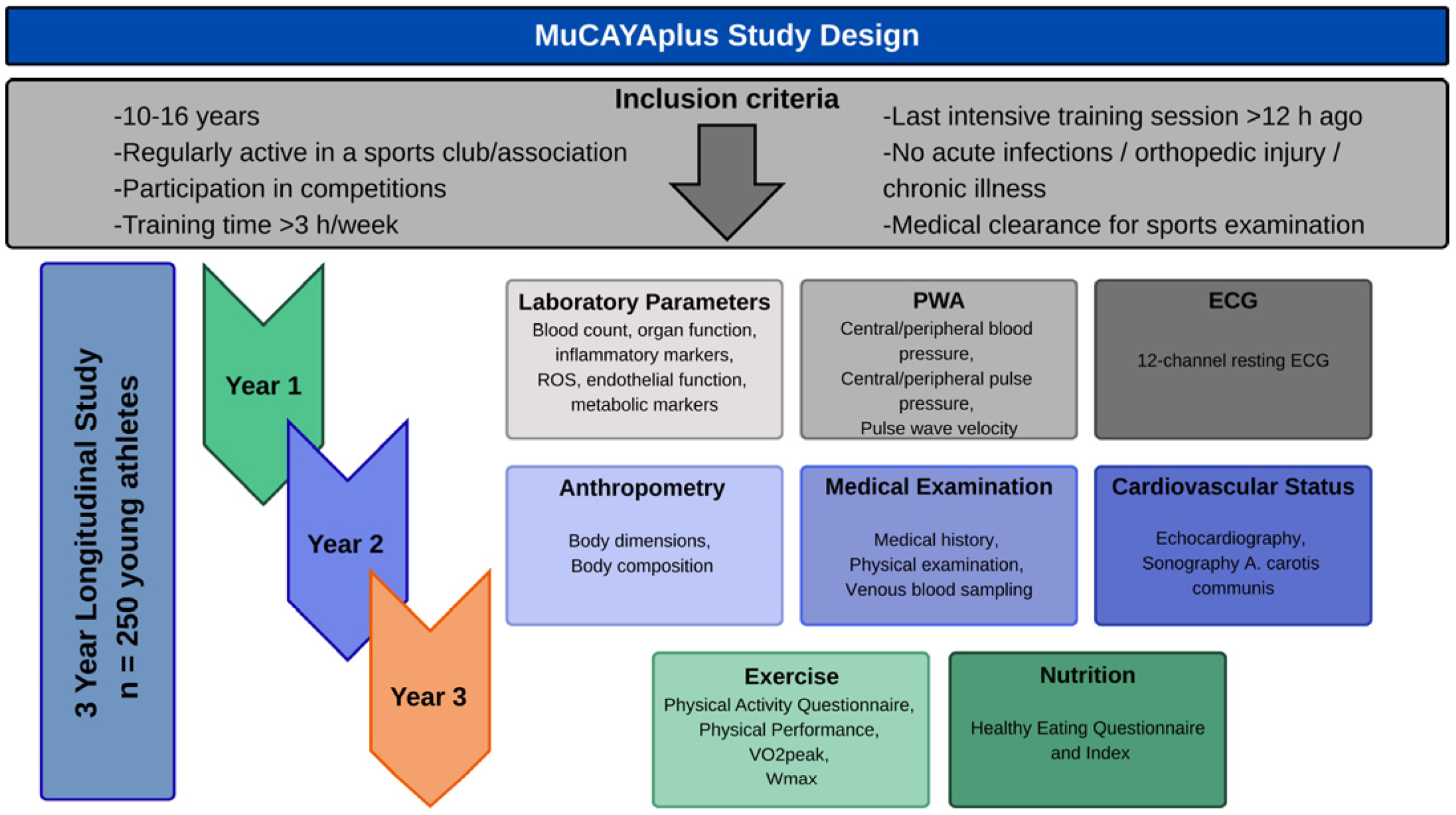

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Participants

2.3. Measurements

2.3.1. Anthropometrics

2.3.2. Basic Cardiovascular Diagnostic

2.3.3. Sonographic Measurement of Structural and Functional Vascular Parameters

2.3.4. Cardiopulmonary Fitness

2.3.5. Venous Blood Sampling and Analysis of Laboratory Parameters

2.3.6. Physical Activity Questionnaire (MoMo-PAQ)

2.4. Ethical Considerations

2.5. Statistical Analysis

- Model 1: unadjusted (bivariate),

- Model 2: + age, sex,

- Model 3: + body composition (BSA, body fat %),

- Model 4: + training volume (MET-h/week) and hemodynamic covariates (bSBP, where relevant)

3. Results

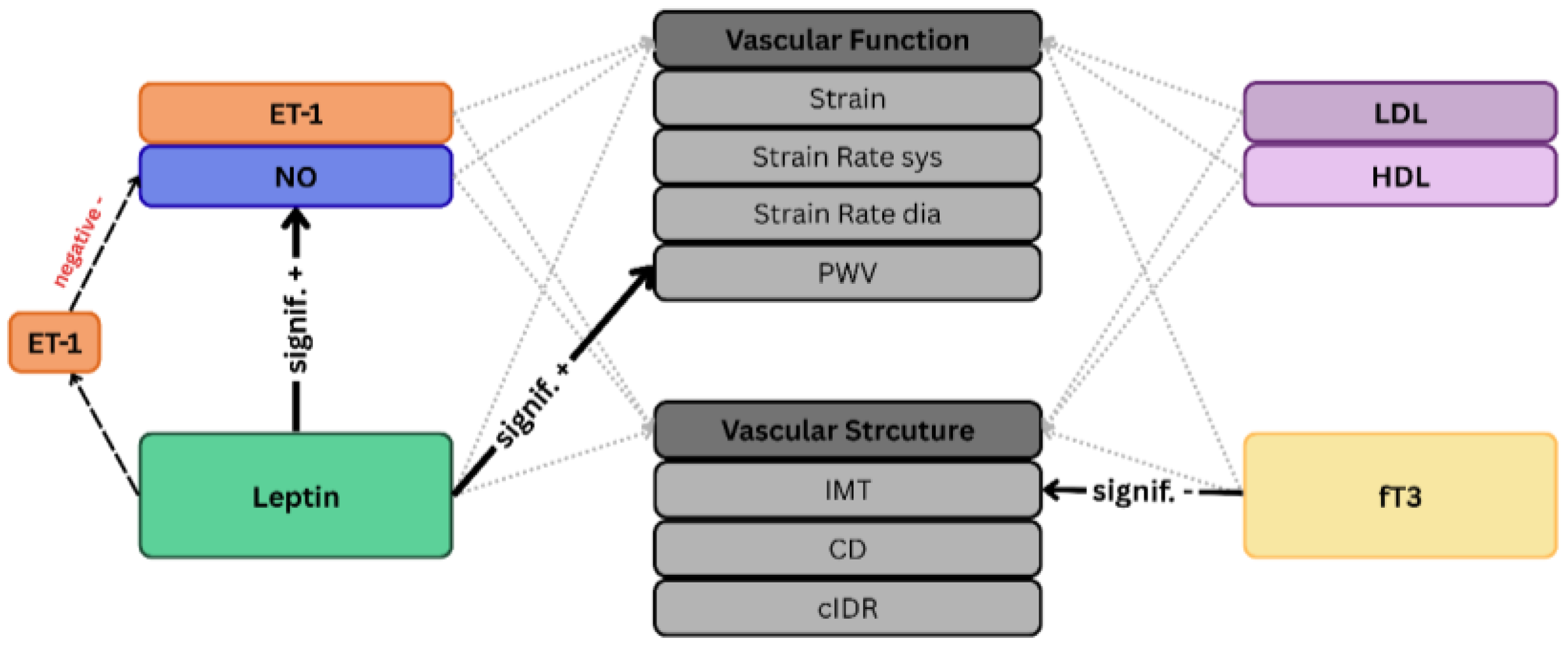

3.1. NO, ET-1 and Endothelial Function (RQ1)

3.2. Lipoprotein Profile and Vascular Structure (RQ2)

3.3. fT3 as a Marker of Energy Metabolism (RQ3)

3.4. Leptin at the Nexus of Energy Balance, and Vascular Function (RQ4)

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CV | Cardiovascular |

| OXS | Oxidative Stress |

| PA | Physical Activity |

| IMT | Intima-Media Thickness |

| VAC | Ventriculo-Arterial Coupling |

| NO | Nitric Oxide |

| ET-1 | Endothelin-1 |

| eNOS | Endothelial NO Synthase |

| PI3K | Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase |

| Akt | Protein Kinase B |

| fT3 | Free Triiodothyronine |

| BMI | Body Mass Index |

| BF% | Body Fat Percentage |

| HDL | High Density Lipoprotein |

| SR-BI | Scavenger Receptor class B type 1 |

| Src | Tyrosine Protein Kinase Src |

| MAPK | Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase |

| LDL | Low Density Lipoprotein |

| PWV | Pulse Wave Velocity |

| MuCAYA | Munich Cardiovascular Adaptation in Young Athletes |

References

- McGill, H.C.; McMahan, C.A.; Gidding, S.S. Preventing Heart Disease in the 21st Century. Circulation 2008, 117, 1216–1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berenson, G.S.; Srinivasan, S.R.; Bao, W.; Newman, W.P.; Tracy, R.E.; Wattigney, W.A. Association between Multiple Cardiovascular Risk Factors and Atherosclerosis in Children and Young Adults. N. Engl. J. Med. 1998, 338, 1650–1656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dallaire, F.; Sarkola, T. Growth of Cardiovascular Structures from the Fetus to the Young Adult. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2018, 1065, 347–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Y.; Mynard, J.P.; Smith, K.J.; Juonala, M.; Urbina, E.M.; Niiranen, T.; Daniels, S.R.; Xi, B.; Magnussen, C.G. Pediatric Blood Pressure and Cardiovascular Health in Adulthood. Curr. Hypertens. Rep. 2024, 26, 431–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Böhm, B.; Oberhoffer, R. Vascular health determinants in children. Cardiovasc. Diagn. Ther. 2019, 9 (Suppl. 2), S269–S280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juonala, M.; Viikari, J.S.; Rönnemaa, T.; Helenius, H.; Taittonen, L.; Raitakari, O.T. Elevated blood pressure in adolescent boys predicts endothelial dysfunction: The cardiovascular risk in young Finns study. Hypertension 2006, 48, 424–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Merghani, A.; Mont, L. Exercise and the heart: The good, the bad, and the ugly. Eur. Heart J. 2015, 36, 1445–1453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiuza-Luces, C.; Garatachea, N.; Berger, N.A.; Lucia, A. Exercise is the real polypill. Physiology 2013, 28, 330–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, D.M.; Radom-Aizik, S. Exercise-associated prevention of adult cardiovascular disease in children and adolescents: Monocytes, molecular mechanisms, and a call for discovery. Pediatr. Res. 2020, 87, 309–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pahkala, K.; Heinonen, O.J.; Lagström, H.; Hakala, P.; Simell, O.; Viikari, J.S.; Rönnemaa, T.; Hernelahti, M.; Sillanmäki, L.; Raitakari, O.T. Vascular endothelial function and leisure-time physical activity in adolescents. Circulation 2008, 118, 2353–2359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos-Parker, J.R.; LaRocca, T.J.; Seals, D.R. Aerobic exercise and other healthy lifestyle factors that influence vascular aging. Adv. Physiol. Educ. 2014, 38, 296–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornelissen, V.A.; Smart, N.A. Exercise training for blood pressure: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2013, 2, e004473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, J.-Y.; Guo, L. Exercise-regulated lipolysis: Its role and mechanism in health and diseases. J. Adv. Res. 2024, 75, 291–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noland, R.C. Exercise and Regulation of Lipid Metabolism. Prog. Mol. Biol. Transl. Sci. 2015, 135, 39–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gleeson, M.; Bishop, N.C.; Stensel, D.J.; Lindley, M.R.; Mastana, S.S.; Nimmo, M.A. The anti-inflammatory effects of exercise: Mechanisms and implications for the prevention and treatment of disease. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2011, 11, 607–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simioni, C.; Zauli, G.; Martelli, A.M.; Vitale, M.; Sacchetti, G.; Gonelli, A.; Neri, L.M. Oxidative stress: Role of physical exercise and antioxidant nutraceuticals in adulthood and aging. Oncotarget 2018, 9, 17181–17198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. WHO Guidelines Approved by the Guidelines Review Committee. In Global Recommendations on Physical Activity for Health; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Sabato, T.M.; Walch, T.J.; Caine, D.J. The elite young athlete: Strategies to ensure physical and emotional health. Open Access J. Sports Med. 2016, 7, 99–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Little, C.C.; Howell, D.R.; Armento, A.M.; Sweeney, E.A.; Walker, G.A. Training volume recommendations and psychosocial outcomes in adolescent athletes. Phys. Sportsmed. 2023, 51, 420–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohn, J.N.; Ferrari, R.; Sharpe, N. Cardiac remodeling—Concepts and clinical implications: A consensus paper from an international forum on cardiac remodeling. Behalf of an International Forum on Cardiac Remodeling. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2000, 35, 569–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, D.J.; Hopman, M.T.E.; Padilla, J.; Laughlin, M.H.; Thijssen, D.H.J. Vascular Adaptation to Exercise in Humans: Role of Hemodynamic Stimuli. Physiol. Rev. 2017, 97, 495–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weberruß, H.; Engl, T.; Baumgartner, L.; Mühlbauer, F.; Shehu, N.; Oberhoffer-Fritz, R. Cardiac Structure and Function in Junior Athletes: A Systematic Review of Echocardiographic Studies. Rev. Cardiovasc. Med. 2022, 23, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumgartner, L.; Weberruß, H.; Engl, T.; Schulz, T.; Oberhoffer-Fritz, R. Exercise Training Duration and Intensity Are Associated With Thicker Carotid Intima-Media Thickness but Improved Arterial Elasticity in Active Children and Adolescents. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2021, 8, 618294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guarracino, F.; Baldassarri, R.; Pinsky, M.R. Ventriculo-arterial decoupling in acutely altered hemodynamic states. Crit. Care 2013, 17, 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitchell, G.F. Arterial Stiffness and Wave Reflection: Biomarkers of Cardiovascular Risk. Artery Res. 2009, 3, 56–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.L.; Jo, S.H. Arterial Stiffness and Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction. J. Korean Med. Sci. 2024, 39, e195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Padilla, J.; Simmons, G.H.; Bender, S.B.; Arce-Esquivel, A.A.; Whyte, J.J.; Laughlin, M.H. Vascular effects of exercise: Endothelial adaptations beyond active muscle beds. Physiology 2011, 26, 132–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandoo, A.; van Zanten, J.J.; Metsios, G.S.; Carroll, D.; Kitas, G.D. The endothelium and its role in regulating vascular tone. Open Cardiovasc. Med. J. 2010, 4, 302–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nosarev, A.V.; Smagliy, L.V.; Anfinogenova, Y.; Popov, S.V.; Kapilevich, L.V. Exercise and NO production: Relevance and implications in the cardiopulmonary system. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2014, 2, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, C.; Møller, S.; Ehlers, T.; Wickham, K.A.; Bangsbo, J.; Gliemann, L.; Hellsten, Y. Redox balance in human skeletal muscle-derived endothelial cells—Effect of exercise training. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2022, 179, 144–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boughaleb, H.; Lobysheva, I.; Dei Zotti, F.; Balligand, J.L.; Montiel, V. Biological Assessment of the NO-Dependent Endothelial Function. Molecules 2022, 27, 7921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanhoutte, P.M.; Shimokawa, H.; Tang, E.H.; Feletou, M. Endothelial dysfunction and vascular disease. Acta Physiol. 2009, 196, 193–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banecki, K.; Dora, K.A. Endothelin-1 in Health and Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank, B.S.; Khailova, L.; Silveira, L.; Mitchell, M.B.; Morgan, G.J.; DiMaria, M.V.; Davidson, J.A. Increased Circulating Endothelin 1 Is Associated With Postoperative Hypoxemia in Infants With Single-Ventricle Heart Disease Undergoing Superior Cavopulmonary Anastomosis. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2022, 11, e024007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Genovesi, S.; Giussani, M.; Orlando, A.; Lieti, G.; Viazzi, F.; Parati, G. Relationship between endothelin and nitric oxide pathways in the onset and maintenance of hypertension in children and adolescents. Pediatr. Nephrol. 2022, 37, 537–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bourque, S.L.; Davidge, S.T.; Adams, M.A. The interaction between endothelin-1 and nitric oxide in the vasculature: New perspectives. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2011, 300, R1288–R1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poetsch, M.S.; Strano, A.; Guan, K. Role of Leptin in Cardiovascular Diseases. Front. Endocrinol. 2020, 11, 354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razvi, S.; Jabbar, A.; Pingitore, A.; Danzi, S.; Biondi, B.; Klein, I.; Peeters, R.; Zaman, A.; Iervasi, G. Thyroid Hormones and Cardiovascular Function and Diseases. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2018, 71, 1781–1796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carrillo-Sepúlveda, M.A.; Ceravolo, G.S.; Fortes, Z.B.; Carvalho, M.H.; Tostes, R.C.; Laurindo, F.R.; Webb, R.C.; Barreto-Chaves, M.L. Thyroid hormone stimulates NO production via activation of the PI3K/Akt pathway in vascular myocytes. Cardiovasc. Res. 2010, 85, 560–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vecchione, C.; Maffei, A.; Colella, S.; Aretini, A.; Poulet, R.; Frati, G.; Gentile, M.T.; Fratta, L.; Trimarco, V.; Trimarco, B.; et al. Leptin Effect on Endothelial Nitric Oxide Is Mediated Through Akt–Endothelial Nitric Oxide Synthase Phosphorylation Pathway. Diabetes 2002, 51, 168–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubey, L.; Hesong, Z. Role of leptin in atherogenesis. Exp. Clin. Cardiol. 2006, 11, 269–275. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, R.; Barouch, L.A. Leptin Signaling and Obesity. Circ. Res. 2007, 101, 545–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singhal, A.; Farooqi, I.S.; Cole, T.J.; O’Rahilly, S.; Fewtrell, M.; Kattenhorn, M.; Lucas, A.; Deanfield, J. Influence of leptin on arterial distensibility: A novel link between obesity and cardiovascular disease? Circulation 2002, 106, 1919–1924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Pavón, D.; Ortega, F.B.; Artero, E.G.; Labayen, I.; Vicente-Rodriguez, G.; Huybrechts, I.; Moreno, L.A.; Manios, Y.; Béghin, L.; Polito, A.; et al. Physical activity, fitness, and serum leptin concentrations in adolescents. J. Pediatr. 2012, 160, 598–603.e592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirico, F.; Bianco, A.; D’Alicandro, G.; Castaldo, C.; Montagnani, S.; Spera, R.; Di Meglio, F.; Nurzynska, D. Effects of Physical Exercise on Adiponectin, Leptin, and Inflammatory Markers in Childhood Obesity: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Child. Obes. 2018, 14, 207–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ludwig, C.; Knoll-Pientka, N.; Mwanri, A.; Erfle, C.; Onywera, V.; Tremblay, M.S.; Bühlmeier, J.; Luzak, A.; Ferland, M.; Schulz, H.; et al. Low leptin levels are associated with elevated physical activity among lean school children in rural Tanzania. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mann, D.R.; Johnson, A.O.; Gimpel, T.; Castracane, V.D. Changes in circulating leptin, leptin receptor, and gonadal hormones from infancy until advanced age in humans. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2003, 88, 3339–3345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carreras-Badosa, G.; Puerto-Carranza, E.; Mas-Parés, B.; Gómez-Vilarrubla, A.; Cebrià-Fondevila, H.; Díaz-Roldán, F.; Riera-Pérez, E.; de Zegher, F.; Ibañez, L.; Bassols, J.; et al. Circulating free T3 associates longitudinally with cardio-metabolic risk factors in euthyroid children with higher TSH. Front. Endocrinol. 2023, 14, 1172720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiroi, Y.; Kim, H.H.; Ying, H.; Furuya, F.; Huang, Z.; Simoncini, T.; Noma, K.; Ueki, K.; Nguyen, N.H.; Scanlan, T.S.; et al. Rapid nongenomic actions of thyroid hormone. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2006, 103, 14104–14109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarei, M.; Zaeemi, M.; Rashidlamir, A. Effects of testosterone enanthate treatment in conjunction with resistance training on thyroid hormones and lipid profile in male Wistar rats. Andrologia 2018, 50, e12862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ignacio, D.L.; da Silvestre, D.H.; Cavalcanti-de-Albuquerque, J.P.A.; Louzada, R.A.; Carvalho, D.P.; Werneck-de-Castro, J.P. Thyroid Hormone and Estrogen Regulate Exercise-Induced Growth Hormone Release. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0122556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ain, K.B.; Mori, Y.; Refetoff, S. Reduced clearance rate of thyroxine-binding globulin (TBG) with increased sialylation: A mechanism for estrogen-induced elevation of serum TBG concentration. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 1987, 65, 689–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ittermann, T.; Thamm, M.; Wallaschofski, H.; Rettig, R.; Völzke, H. Serum thyroid-stimulating hormone levels are associated with blood pressure in children and adolescents. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2012, 97, 828–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, D.R., Jr.; Woo, J.G.; Sinaiko, A.R.; Daniels, S.R.; Ikonen, J.; Juonala, M.; Kartiosuo, N.; Lehtimäki, T.; Magnussen, C.G.; Viikari, J.S.A.; et al. Childhood Cardiovascular Risk Factors and Adult Cardiovascular Events. N. Engl. J. Med. 2022, 386, 1877–1888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koskinen, J.S.; Kytö, V.; Juonala, M.; Viikari, J.S.A.; Nevalainen, J.; Kähönen, M.; Lehtimäki, T.; Hutri-Kähönen, N.; Laitinen, T.P.; Tossavainen, P.; et al. Childhood Dyslipidemia and Carotid Atherosclerotic Plaque in Adulthood: The Cardiovascular Risk in Young Finns Study. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2023, 12, e027586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mineo, C.; Shaul, P.W. HDL stimulation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase: A novel mechanism of HDL action. Trends Cardiovasc. Med. 2003, 13, 226–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaul, P.W. Endothelial nitric oxide synthase, caveolae and the development of atherosclerosis. J. Physiol. 2003, 547, 21–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, H.; Zhou, Y.; Nabavi, S.M.; Sahebkar, A.; Little, P.J.; Xu, S.; Weng, J.; Ge, J. Mechanisms of Oxidized LDL-Mediated Endothelial Dysfunction and Its Consequences for the Development of Atherosclerosis. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2022, 9, 925923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franczyk, B.; Gluba-Brzózka, A.; Ciałkowska-Rysz, A.; Ławiński, J.; Rysz, J. The Impact of Aerobic Exercise on HDL Quantity and Quality: A Narrative Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 4653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Böhm, B.; Hartmann, K.; Buck, M.; Oberhoffer, R. Sex differences of carotid intima-media thickness in healthy children and adolescents. Atherosclerosis 2009, 206, 458–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinaffi-Langley, A.; Dajani, R.M.; Prater, M.C.; Nguyen, H.V.M.; Vrancken, K.; Hays, F.A.; Hord, N.G. Dietary Nitrate from Plant Foods: A Conditionally Essential Nutrient for Cardiovascular Health. Adv. Nutr. 2024, 15, 100158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Li, T.; Li, J.; Zheng, D.; Yang, J.; Zhuang, X. Linear association of compound dietary antioxidant index with hyperlipidemia: A cross-sectional study. Front. Nutr. 2024, 11, 1365580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Donnell, E.; Harvey, P.J.; De Souza, M.J. Relationships between vascular resistance and energy deficiency, nutritional status and oxidative stress in oestrogen deficient physically active women. Clin. Endocrinol. 2009, 70, 294–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, D.J.; Maiorana, A.; O’Driscoll, G.; Taylor, R. Effect of exercise training on endothelium-derived nitric oxide function in humans. J. Physiol. 2004, 561, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelley, G.A.; Kelley, K.S. Aerobic exercise and lipids and lipoproteins in children and adolescents: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Atherosclerosis 2007, 191, 447–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Li, X.; Liu, X.; Xu, Y.; Feng, H.; Ren, L. Exercise blood pressure, cardiorespiratory fitness, fatness and cardiovascular risk in children and adolescents. Front. Public Health 2024, 12, 1298612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agbaje, A.O.; Barker, A.R.; Lewandowski, A.J.; Leeson, P.; Tuomainen, T.-P. Accelerometer-based sedentary time, light physical activity, and moderate-to-vigorous physical activity from childhood with arterial stiffness and carotid IMT progression: A 13-year longitudinal study of 1339 children. Acta Physiol. 2024, 240, e14132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agbaje, A.O. Arterial stiffness precedes hypertension and metabolic risks in youth: A review. J. Hypertens. 2022, 40, 1887–1896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haferanke, J.; Baumgartner, L.; Willinger, L.; Schulz, T.; Mühlbauer, F.; Engl, T.; Weberruß, H.; Hofmann, H.; Wasserfurth, P.; Köhler, K.; et al. The MuCAYAplus Study—Influence of Physical Activity and Metabolic Parameters on the Structure and Function of the Cardiovascular System in Young Athletes. CJC Open 2024, 6, 1549–1557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Waist Circumference and Waist-Hip Ratio: Report of a WHO Expert Consultation, Geneva, 8–11 December 2008; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Du Bois, D.; Du Bois, E.F. A formula to estimate the approximate surface area if height and weight be known. 1916. Nutrition 1989, 5, 303–311, discussion 312–303. [Google Scholar]

- Neuhauser, H.; Schienkiewitz, A.; Rosario, A.S.; Dortschy, R.; Kurth, B.-M. Referenzperzentile für Anthropometrische Maßzahlen und Blutdruck aus der Studie zur Gesundheit von Kindern und Jugendlichen in Deutschland (KiGGS); Robert Koch-Institut: Berlin, Germany, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godfrey, S. Exercise Testing in Children: Applications in Health and Disease; Saunders Limited: Rhodes, NSW, Australia, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Takken, T.; Bongers, B.C.; van Brussel, M.; Haapala, E.A.; Hulzebos, E.H.J. Cardiopulmonary Exercise Testing in Pediatrics. Ann. Am. Thorac. Soc. 2017, 14 (Suppl. 1), S123–S128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jekauc, D.; Voelkle, M.; Wagner, M.O.; Mewes, N.; Woll, A. Reliability, validity, and measurement invariance of the German version of the physical activity enjoyment scale. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2013, 38, 104–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bös, K.; Opper, E.; Worth, A.; Oberge, J.; Romahn, N.; Wagner, M.; Woll, A. Motorik-Modul: Motorische Leistungsfähigkeit und körperlich-sportliche Aktivität von Kindern und Jugendlichen in Deutschland. Foss. Newsl. 2007, 7, 1–2. [Google Scholar]

- Dimmeler, S.; Fleming, I.; Fisslthaler, B.; Hermann, C.; Busse, R.; Zeiher, A.M. Activation of nitric oxide synthase in endothelial cells by Akt-dependent phosphorylation. Nature 1999, 399, 601–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mellott, E.; Faulkner, J.L. Mechanisms of leptin-induced endothelial dysfunction. Curr. Opin. Nephrol. Hypertens. 2023, 32, 118–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Elia, L.; Giaquinto, A.; Iacone, R.; Russo, O.; Strazzullo, P.; Galletti, F. Serum leptin is associated with increased pulse pressure and the development of arterial stiffening in adult men: Results of an eight-year follow-up study. Hypertens. Res. 2021, 44, 1444–1450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Z.; Yuhanna, I.S.; Galcheva-Gargova, Z.; Karas, R.H.; Mendelsohn, M.E.; Shaul, P.W. Estrogen receptor alpha mediates the nongenomic activation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase by estrogen. J. Clin. Investig. 1999, 103, 401–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belin de Chantemèle, E.J. Sex Differences in Leptin Control of Cardiovascular Function in Health and Metabolic Diseases. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2017, 1043, 87–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahiante, B.; Smith, W.; Lammertyn, L.; Schutte, A. Leptin and the vasculature in young adults: The African-PREDICT study. Eur. J. Clin. Investig. 2018, 49, e13039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Zhao, L.; Wang, T.; Hong, J.; Zhang, J.; Xu, B.; Huang, X.; Xu, M.; Bi, Y. Free Triiodothyronine Concentrations are Inversely Associated with Elevated Carotid Intima-Media Thickness in Middle-Aged and Elderly Chinese Population. J. Atheroscler. Thromb. 2016, 23, 216–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Rizos, C.V.; Elisaf, M.S.; Liberopoulos, E.N. Effects of thyroid dysfunction on lipid profile. Open Cardiovasc. Med. J. 2011, 5, 76–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodríguez-Gómez, I.; Moliz, J.N.; Quesada, A.; Montoro-Molina, S.; Vargas-Tendero, P.; Osuna, A.; Wangensteen, R.; Vargas, F. L-Arginine metabolism in cardiovascular and renal tissue from hyper- and hypothyroid rats. Exp. Biol. Med. 2016, 241, 550–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zúñiga, D.; Balasubramanian, S.; Mehmood, K.T.; Al-Baldawi, S.; Zúñiga Salazar, G. Hypothyroidism and Cardiovascular Disease: A Review. Cureus 2024, 16, e52512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bensenor, I.M. Thyroid disorders in Brazil: The contribution of the Brazilian Longitudinal Study of Adult Health (ELSA-Brasil). Braz. J. Med. Biol. Res. 2019, 52, e8417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Gioia, G.; Squeo, M.R.; Lemme, E.; Maestrini, V.; Monosilio, S.; Ferrera, A.; Buzzelli, L.; Valente, D.; Pelliccia, A. Association between FT3 Levels and Exercise-Induced Cardiac Remodeling in Elite Athletes. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 1530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robert, J. Sex differences in vascular endothelial cells. Atherosclerosis 2023, 384, 117278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maeda, S.; Tanabe, T.; Miyauchi, T.; Otsuki, T.; Sugawara, J.; Iemitsu, M.; Kuno, S.; Ajisaka, R.; Yamaguchi, I.; Matsuda, M. Aerobic exercise training reduces plasma endothelin-1 concentration in older women. J. Appl. Physiol. 2003, 95, 336–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsukiyama, Y.; Ito, T.; Nagaoka, K.; Eguchi, E.; Ogino, K. Effects of exercise training on nitric oxide, blood pressure and antioxidant enzymes. J. Clin. Biochem. Nutr. 2017, 60, 180–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arefirad, T.; Seif, E.; Sepidarkish, M.; Mohammadian Khonsari, N.; Mousavifar, S.A.; Yazdani, S.; Rahimi, F.; Einollahi, F.; Heshmati, J.; Qorbani, M. Effect of exercise training on nitric oxide and nitrate/nitrite (NOx) production: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Physiol. 2022, 13, 953912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haferanke, J.; Baumgartner, L.; Willinger, L.; Oberhoffer-Fritz, R.; Schulz, T. Molecular Mechanisms of Vascular Tone in Exercising Pediatric Populations: A Comprehensive Overview on Endothelial, Antioxidative, Metabolic and Lipoprotein Signaling Molecules. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maeda, S.; Miyauchi, T.; Iemitsu, M.; Sugawara, J.; Nagata, Y.; Goto, K. Resistance exercise training reduces plasma endothelin-1 concentration in healthy young humans. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 2004, 44 (Suppl. 1), S443–S446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ichiki, T. Thyroid Hormone and Vascular Remodeling. J. Atheroscler. Thromb. 2016, 23, 266–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herzog, M.J.; Müller, P.; Lechner, K.; Stiebler, M.; Arndt, P.; Kunz, M.; Ahrens, D.; Schmeißer, A.; Schreiber, S.; Braun-Dullaeus, R.C. Arterial stiffness and vascular aging: Mechanisms, prevention, and therapy. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2025, 10, 282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Gioia, G.; Buzzelli, L.; Ferrera, A.; Maestrini, V.; Squeo, M.R.; Lemme, E.; Monosilio, S.; Serdoz, A.; Pelliccia, A. Influence of Persistently Elevated LDL Values on Carotid Intima Media Thickness in Elite Athletes. High. Blood Press. Cardiovasc. Prev. 2025, 32, 171–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karacabey, K. The effect of exercise on leptin, insulin, cortisol and lipid profiles in obese children. J. Int. Med. Res. 2009, 37, 1472–1478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zorba, E.; Cengiz, T.; Karacabey, K. Exercise training improves body composition, blood lipid profile and serum insulin levels in obese children. J. Sports Med. Phys. Fit. 2011, 51, 664–669. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.; Qin, Z.; Wang, Y.; Li, X.; Zheng, Y.; Liu, Y. Role of Inflammation in Vascular Disease-Related Perivascular Adipose Tissue Dysfunction. Front. Endocrinol. 2021, 12, 710842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, L.; Garcia-Barrio, M.T.; Chen, Y.E. Perivascular Adipose Tissue Regulates Vascular Function by Targeting Vascular Smooth Muscle Cells. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2020, 40, 1094–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nusser, V.; Murphy, C.; Hechenbichler Figueroa, S.; Braunsperger, A.; Ihalainen, J.K.; Hulmi, J.J.; Wasserfurth, P.; Koehler, K. Metabolic signature of short-term low energy availability. Physiol. Rep. 2025, 13, e70582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| n | Total (M ± SD) | n | Boys (M ± SD) | n | Girls (M ± SD) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (yrs) | 203 | 13.5 ± 1.6 | 156 | 13.6 ± 1.6 | 47 | 13.1 ± 1.61 | 0.058 |

| Body mass (kg) | 203 | 52.5 ± 12.3 | 156 | 53.4 ± 12.6 | 47 | 49.4 ± 11.0 | 0.051 |

| Body height (cm) | 203 | 165.6 ± 12.7 | 156 | 166.8 ± 13.3 | 47 | 161.7 ± 9.7 | 0.005 ** |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 203 | 18.8 ± 2.3 | 156 | 18.9 ± 2.1 | 47 | 18.7 ± 2.7 | 0.556 |

| BSA (m2) | 203 | 1.5 ± 0.2 | 156 | 1.5 ± 0.2 | 47 | 1.5 ± 0.2 | 0.022 * |

| Body Fat (%) | 200 | 12.9 ± 5.9 | 154 | 11.7 ± 5.8 | 46 | 16.8 ± 4.5 | <0.001 *** |

| FFM (kg) | 200 | 45.3 ± 11.9 | 154 | 46.8 ± 12.6 | 46 | 40.3 ± 8.0 | <0.001 *** |

| bSBP (mmHg) | 203 | 110.72 ± 9.37 | 156 | 111.89 ± 9.08 | 47 | 106.82 ± 9.36 | 0.001 *** |

| bDBP (mmHg) | 203 | 62.35 ± 6.15 | 156 | 62.69 ± 5.95 | 47 | 61.25 ± 6.69 | 0.161 |

| PWV (m/s) | 203 | 4.58 ± 0.405 | 156 | 4.62 ± 0.41 | 47 | 4.46 ± 0.36 | 0.022 * |

| IMT (mm) | 203 | 0.480 ± 0.037 | 156 | 0.48 ± 0.03 | 47 | 0.46 ± 0.03 | 0.001 *** |

| CD (mm) | 203 | 5.97 ± 0.35 | 156 | 6.00 ± 0.36 | 47 | 5.87 ± 0.30 | 0.026 * |

| cIDR | 203 | 0.08 ± 0.006 | 156 | 0.08 ± 0.007 | 47 | 0.08 ± 0.006 | 0.142 |

| Strain (%) | 203 | 9.89 ± 2.56 | 156 | 10.32 ± 2.55 | 47 | 8.46 ± 2.06 | <0.001 *** |

| SRsys (m/s) | 203 | 1.18 ± 0.26 | 156 | 1.21 ± 1.21 | 47 | 1.09 ± 0.24 | 0.006 ** |

| SRdia (m/s) | 203 | −0.99 ± 0.29 | 156 | −0.99 ± 0.29 | 47 | −1.01 ± 0.26 | 0.735 |

| MET-h/week | 203 | 96.89 ± 46.07 | 156 | 96.28 ± 40.51 | 47 | 98.90 ± 61.52 | 0.785 |

| NO (µmol/L) | 202 | 23.89 ± 10.65 | 156 | 24.18 ± 9.62 | 46 | 22.88 ± 13.66 | 0.468 |

| ET-1 (pg/mL) | 202 | 1.10 ± 0.31 | 156 | 1.09 ± 0.31 | 46 | 1.11 ± 0.33 | 0.793 |

| Leptin (ng/mL) | 194 | 3.01 ± 4.62 | 148 | 2.15 ± 3.81 | 46 | 5.77 ± 5.85 | <0.001 *** |

| HDL (mg/dL) | 201 | 57.49 ± 10.82 | 154 | 56.74 ± 10.50 | 47 | 59.95 ± 11.57 | 0.075 |

| LDL (mg/dL) | 201 | 92.60 ± 24.83 | 154 | 91.42 ± 25.14 | 47 | 96.46 ± 23.61 | 0.224 |

| fT3 (pg/mL) | 201 | 3.74 ± 0.42 | 154 | 3.78 ± 0.41 | 47 | 3.62 ± 0.44 | 0.023 * |

| Wattmax (W) | 203 | 228.15 ± 67.77 | 156 | 239.50 ± 69.35 | 47 | 190.48 ± 45.60 | <0.001 *** |

| VO2peak (l/min) | 203 | 2.57 ± 0.72 | 156 | 2.71 ± 0.73 | 47 | 2.12 ± 0.47 | <0.001 *** |

| VO2peak_rel (ml/min/kg) | 203 | 48.99 ± 6.70 | 156 | 50.66 ± 5.93 | 47 | 43.46 ± 6.17 | <0.001 *** |

| N | Outcome | Model | Direct Effect of Leptin [B, 95% CI], p | Indirect Effects (PROCESS, B, 95%, Boot-CI) | Signif. Covariates (b, p) | R2/adj. R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 192 | NO | Multivariate (age, sex, BF%, MET-h) | 0.112 [0.015–0.209], p = 0.025 * | BF% −0.010, p = 0.005 ** | 0.053/0.028 | |

| 190 | PROCESS (M: ET-1, HDL, LDL; +Covariates) | 0.123 [0.025–0.222], p = 0.015 * | −0.012 [−0.045; 0.018] | ET-1-path: −0.017 [−0.040; −0.001]; HDL/LDL n. s. | 0.097 | |

| 192 | SRdia | Multivariate (age, sex, BF%, MET-h, bSBP) | −0.322 [−0.50; −0.14], p < 0.001 *** | BF% +0.022, p < 0.001 *** | 0.097/0.067 | |

| 190 | PROCESS (M:ET-1, HDL, LDL, NO; +Covariates) | −0.355 [−0.542; −0.168], p = 0.0002 *** | 0.037 [−0.024; 0.101] | Single-path via ET-1/HDL/LDL/NO all n. s. | 0.108 | |

| 192 | SRsys | Multivariate (age, sex, BF%, MET-h, bSBP) | 0.099 [−0.07; 0.26], p = 0.244 | Sex +0.125, p = 0.022 *; BF% −0.010, p = 0.084; bSBP +0.003, p = 0.122 | 0.101/0.072 | |

| 190 | PROCESS (M: ET-1, HDL, LDL; +Covariates) | 0.139 [−0.035; 0.312], p = 0.117 | −0.046 [−0.120; 0.019] | bSBP +0.0044, p = 0.05 *; Sex +0.1125, p = 0.04 *; BF% −0.0124, p = 0.043 *; (ET-1 t = 1.79, p = 0.075) | 0.137 | |

| 192 | Strain | Multivariate (age, sex, BF%, MET-h, bSBP) | 1.114 [−0.38; 2.61], p = 0.146 | Sex +1.784, p < 0.001 ***; BF% −0.125, p = 0.018 *; Alter +0.260, p = 0.034 * | 0.183/0.161 | |

| 190 | PROCESS (M: ET-1, HDL, LDL; +Covariates) | 1.565 [−0.003; 3.133], p = 0.0504 | −0.382 [−1.077; 0.225] | ET-1 +3.290, p = 0.034 *; Sex +1.645, p = 0.001 ***; BF% −0.153, p = 0.0061 ***; bSBP +0.038, p = 0.064 | 0.231 | |

| 192 | PWV | Multivariate (age, sex, BF%, MET-h, bSBP) | 0.143 [−0.02; 0.30], p = 0.075 | bSBP +0.031, p < 0.001 ***; Alter +0.054/J, p = 0.0002 *** | 0.637/0.625 | |

| 190 | PROCESS (M: ET-1, HDL, LDL; +Covariates) | 0.131 [−0.032; 0.294], p = 0.115 | 0.003 [−0.058; 0.064] | LDL −0.0018, p = 0.0206; others n. s. | 0.650 | |

| 192 | IMT | Multivariate (age, sex, BF%, MET-h, bSBP) | −0.002 [−0.026; 0.022], p = 0.839 | 0.119/0.091 | ||

| 190 | PROCESS (M: ET-1, HDL, LDL; +Covariates) | −0.001 [−0.025; 0.023], p = 0.939 | −0.0018 [−0.0097; 0.0055] | 0.137 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Haferanke, J.; Baumgartner, L.; Dettenhofer, M.; Huber, S.; Mühlbauer, F.; Engl, T.; Wasserfurth, P.; Köhler, K.; Oberhoffer, R.; Schulz, T.; et al. Molecular Drivers of Vascular Adaptation in Young Athletes: An Integrative Analysis of Endothelial, Metabolic and Lipoprotein Biomarkers. Biomolecules 2025, 15, 1726. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom15121726

Haferanke J, Baumgartner L, Dettenhofer M, Huber S, Mühlbauer F, Engl T, Wasserfurth P, Köhler K, Oberhoffer R, Schulz T, et al. Molecular Drivers of Vascular Adaptation in Young Athletes: An Integrative Analysis of Endothelial, Metabolic and Lipoprotein Biomarkers. Biomolecules. 2025; 15(12):1726. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom15121726

Chicago/Turabian StyleHaferanke, Jonas, Lisa Baumgartner, Maximilian Dettenhofer, Stefanie Huber, Frauke Mühlbauer, Tobias Engl, Paulina Wasserfurth, Karsten Köhler, Renate Oberhoffer, Thorsten Schulz, and et al. 2025. "Molecular Drivers of Vascular Adaptation in Young Athletes: An Integrative Analysis of Endothelial, Metabolic and Lipoprotein Biomarkers" Biomolecules 15, no. 12: 1726. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom15121726

APA StyleHaferanke, J., Baumgartner, L., Dettenhofer, M., Huber, S., Mühlbauer, F., Engl, T., Wasserfurth, P., Köhler, K., Oberhoffer, R., Schulz, T., & Freilinger, S. (2025). Molecular Drivers of Vascular Adaptation in Young Athletes: An Integrative Analysis of Endothelial, Metabolic and Lipoprotein Biomarkers. Biomolecules, 15(12), 1726. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom15121726