The Adaptable Binding Cleft of RmuAP1, a Pepsin-like Peptidase from Rhodotorula mucilaginosa, Enables the Enzyme to Degrade Immunogenic Peptides Derived from Gluten

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Enzyme Preparation

2.2. Crystallization

2.3. Crystal Structure Determination

2.4. Protein-Ligand Docking Simulation

2.5. MD Simulation

2.6. Binding Free Energy Calculations

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Crystal Structure of RmuAP1

3.2. Structural Comparison of RmuAP1 and Pepsin

3.3. Structural Basis for Distinct Binding Modes of Pepstatin A in RmuAP1 and Pepsin

3.4. Catalytic Geometry of RmuAP1–Ligand Complexes

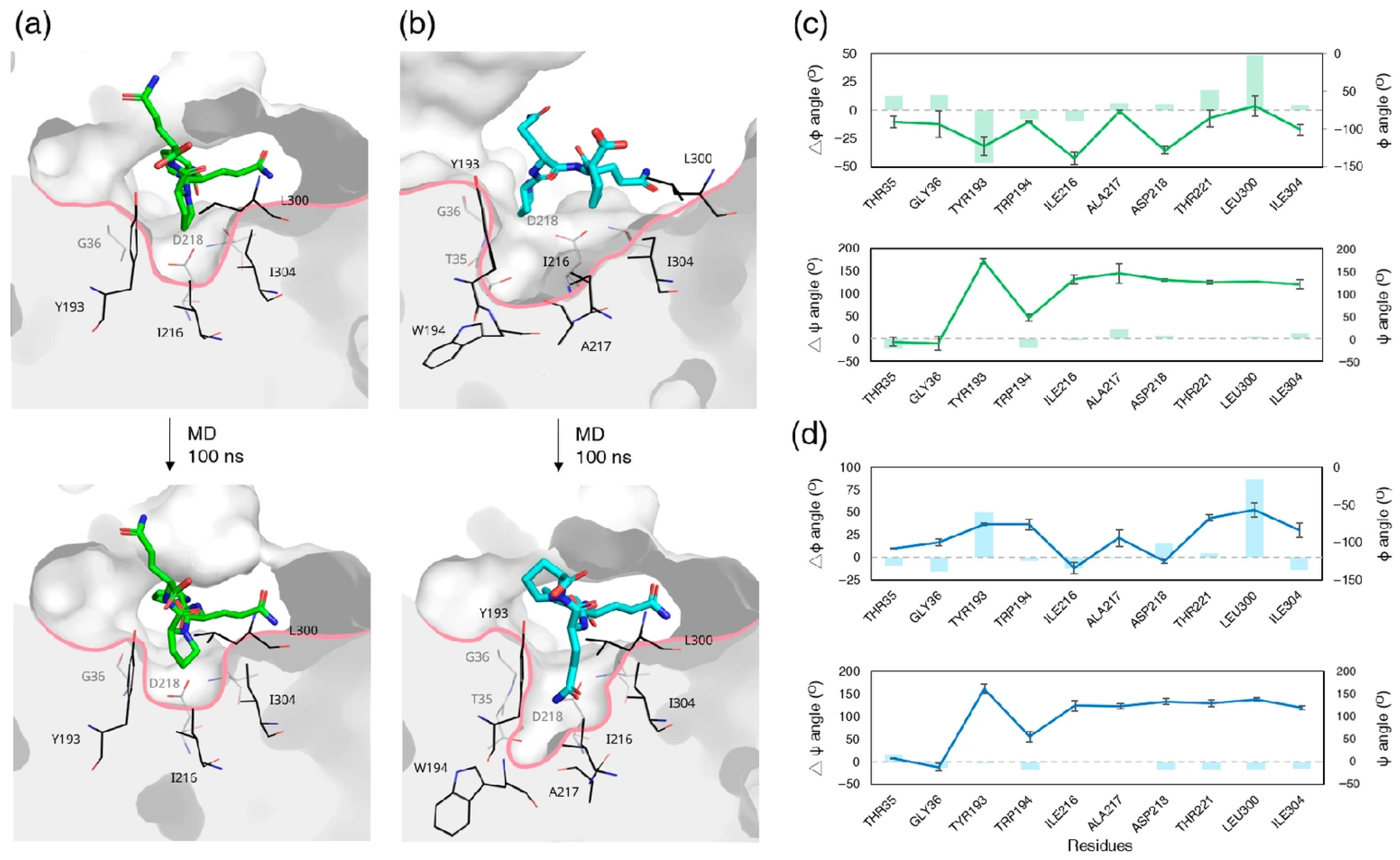

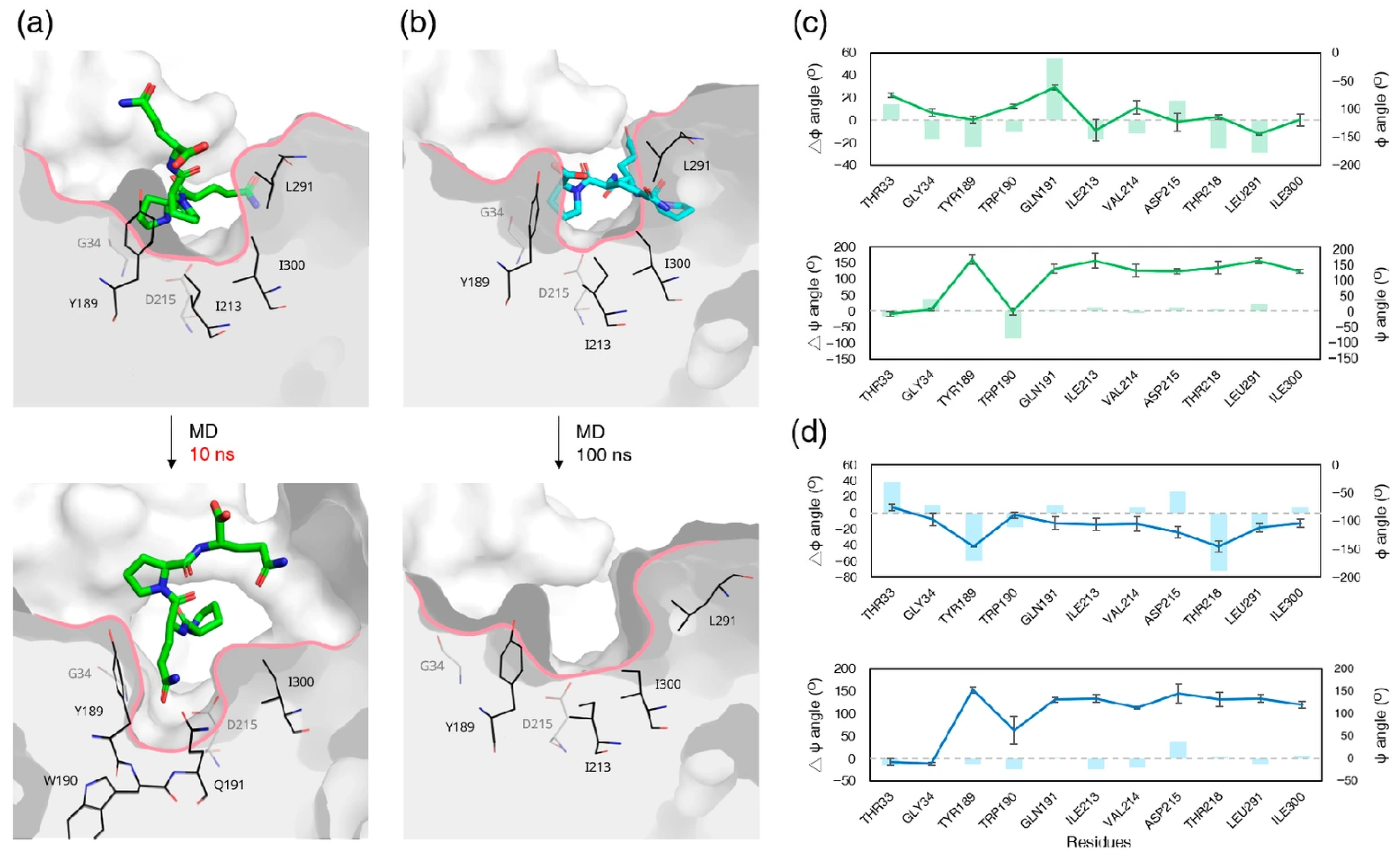

3.5. MD Simulation of Pepsin–Ligand Complexes

3.6. Ligand Binding to RmuAP1 or Pepsin After Simulation

3.7. Ligand-Induced Remodeling of the S1′ Pocket in RmuAP1

3.8. Ligand-Induced Remodeling of the S1′ Pocket in Pepsin

3.9. Apo RmuAP1 Simulations Support an Induced-Fit Model for S1′ Pocket Remodeling in RmuAP1

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CD | Celiac disease |

| GIPs | gluten-derived immunogenic peptides |

| TG2 | tissue transglutaminase 2 |

| GFD | gluten-free diet |

| MD | molecular dynamics |

| DS | Discovery Studio |

| RMSD | root mean square deviation |

| Mindist | minimum distance |

| binding free energy | |

| MM/PBSA | molecular mechanics-Poisson-Boltzmann surface area |

References

- Lindfors, K.; Ciacci, C.; Kurppa, K.; Lundin, K.E.A.; Makharia, G.K.; Mearin, M.L.; Murray, J.A.; Verdu, E.F.; Kaukinen, K. Coeliac disease. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2019, 5, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sollid, L.M. Molecular basis of celiac disease. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2000, 18, 53–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sollid, L.M.; Markussen, G.; Ek, J.; Gjerde, H.; Vartdal, F.; Thorsby, E. Evidence for a primary association of celiac disease to a particular HLA-DQ alpha/beta heterodimer. J. Exp. Med. 1989, 169, 345–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malamut, G.; Afchain, P.; Verkarre, V.; Lecomte, T.; Amiot, A.; Damotte, D.; Bouhnik, Y.; Colombel, J.F.; Delchier, J.C.; Allez, M.; et al. Presentation and long-term follow-up of refractory celiac disease: Comparison of type I with type II. Gastroenterology 2009, 136, 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gujral, N.; Freeman, H.J.; Thomson, A.B. Celiac disease: Prevalence, diagnosis, pathogenesis and treatment. World J. Gastroenterol. 2012, 18, 6036–6059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, L.; Qiao, S.W.; Arentz-Hansen, H.; Molberg, O.; Gray, G.M.; Sollid, L.M.; Khosla, C. Identification and analysis of multivalent proteolytically resistant peptides from gluten: Implications for celiac sprue. J. Proteome Res. 2005, 4, 1732–1741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, L.; Molberg, O.; Parrot, I.; Hausch, F.; Filiz, F.; Gray, G.M.; Sollid, L.M.; Khosla, C. Structural basis for gluten intolerance in celiac sprue. Science 2002, 297, 2275–2279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cosnes, J.; Nion-Larmurier, I. Complications of celiac disease. Pathol. Biol. 2013, 61, e21–e26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El Khoury, D.; Balfour-Ducharme, S.; Joye, I.J. A review on the gluten-free diet: Technological and nutritional challenges. Nutrients 2018, 10, 1410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silvester, J.A.; Comino, I.; Kelly, C.P.; Sousa, C.; Duerksen, D.R.; DOGGIE BAG Study Group. Most patients with celiac disease on gluten-free diets consume measurable amounts of gluten. Gastroenterology 2020, 158, 1497–1499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hausch, F.; Shan, L.; Santiago, N.A.; Gray, G.M.; Khosla, C. Intestinal digestive resistance of immunodominant gliadin peptides. Am. J. Physiol.-Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2002, 283, G996–G1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamone, G.; Ferranti, P.; Rossi, M.; Roepstorff, P.; Fierro, O.; Malorni, A.; Addeo, F. Identification of a peptide from alpha-gliadin resistant to digestive enzymes: Implications for celiac disease. J. Chromatogr. B 2007, 855, 236–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, G.; Helmerhorst, E.J.; Darwish, G.; Blumenkranz, G.; Schuppan, D. Gluten degrading enzymes for treatment of celiac disease. Nutrients 2020, 12, 2095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ráki, M.; Schjetne, K.W.; Stamnaes, J.; Molberg, Ø.; Jahnsen, F.L.; Issekutz, T.B.; Bogen, B.; Sollid, L.M. Surface expression of transglutaminase 2 by dendritic cells and its potential role for uptake and presentation of gluten peptides to T cells. Scand. J. Immunol. 2007, 65, 213–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuppan, D.; Junker, Y.; Barisani, D. Celiac disease: From pathogenesis to novel therapies. Gastroenterology 2009, 137, 1912–1933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sollid, L.M.; Molberg, O.; McAdam, S.; Lundin, K.E. Autoantibodies in coeliac disease: Tissue transglutaminase—Guilt by association? Gut 1997, 41, 851–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonner, E.R.; Tschollar, W.; Anderson, R.; Mourabit, S. Review article: Novel enzyme therapy design for gluten peptide digestion through exopeptidase supplementation. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2025, 61, 1123–1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, J.A.; Syage, J.A.; Wu, T.T.; Dickason, M.A.; Ramos, A.G.; Van Dyke, C.; Horwath, I.; Lavin, P.T.; Mäki, M.; Hujoel, I.; et al. Latiglutenase protects the mucosa and attenuates symptom severity in patients with celiac disease exposed to a gluten challenge. Gastroenterology 2022, 163, 1510–1521.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pultz, I.S.; Hill, M.; Vitanza, J.M.; Wolf, C.; Saaby, L.; Liu, T.; Winkle, P.; Leffler, D.A. Gluten degradation, pharmacokinetics, safety, and tolerability of TAK-062, an engineered enzyme to treat celiac disease. Gastroenterology 2021, 161, 81–93.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Amo-Maestro, L.; Mendes, S.R.; Rodríguez-Banqueri, A.; Garzon-Flores, L.; Girbal, M.; Rodríguez-Lagunas, M.J.; Guevara, T.; Franch, À.; Pérez-Cano, F.J.; Eckhard, U.; et al. Molecular and in vivo studies of a glutamate-class prolyl-endopeptidase for coeliac disease therapy. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 4446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.-H.; Leu, W.-M.; Meng, M. Hydrolysis of gluten-derived celiac disease-triggering peptides across a broad ph range by RmuAP1: A novel aspartic peptidase isolated from Rhodotorula mucilaginosa. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2023, 71, 17202–17213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, C.-K.; Tseng, C.-C.; Chiang, C.-H.; Chen, Y.-H.; Liu, Y.-C.; Huang, C.-Y.; Chao, C.-H.; Huang, C.-H. The current status and future prospects of the synchrotron radiation protein crystallography core facility at NSRRC: A focus on the TPS 05A, TPS 07A and TLS 15A1 beamlines. J. Synchrotron Radiat. 2025, 32 Pt 2, 457–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacKerell, A.D.; Bashford, D.; Bellott, M.; Dunbrack, R.L.; Evanseck, J.D.; Field, M.J.; Fischer, S.; Gao, J.; Guo, H.; Ha, S.; et al. All-atom empirical potential for molecular modeling and dynamics studies of proteins. J. Phys. Chem. B 1998, 102, 3586–3616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, J.; Rauscher, S.; Nawrocki, G.; Ran, T.; Feig, M.; de Groot, B.L.; Grubmüller, H.; MacKerell, A.D., Jr. CHARMM36m: An improved force field for folded and intrinsically disordered proteins. Nat. Methods 2017, 14, 71–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Best, R.B.; Zhu, X.; Shim, J.; Lopes, P.E.; Mittal, J.; Feig, M.; Mackerell, A.D., Jr. Optimization of the additive CHARMM all-atom protein force field targeting improved sampling of the backbone φ, ψ and side-chain χ(1) and χ(2) dihedral angles. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2012, 8, 3257–3273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coates, L.; Tuan, H.-F.; Tomanicek, S.; Kovalevsky, A.; Mustyakimov, M.; Erskine, P.; Cooper, J. The catalytic mechanism of an aspartic proteinase explored with neutron and X-ray diffraction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008, 130, 7235–7237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabbah, D.A.; Zhong, H.A. Modeling the protonation states of β-secretase binding pocket by molecular dynamics simulations and docking studies. J. Mol. Graph. Model. 2016, 68, 206–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, R.; Caflisch, A. The protonation state of the catalytic aspartates in plasmepsin II. FEBS Lett. 2007, 581, 4120–4124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anandakrishnan, R.; Aguilar, B.; Onufriev, A.V. H ++ 3.0: Automating PK Prediction and the Preparation of Biomolecular Structures for Atomistic Molecular Modeling and Simulations. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012, 40, W537–W541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Y.; Miao, Y.; Cong, Y.; Wang, J.; Zhi, F.; Pan, Y.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, J.Z.; Zhang, L. High-level expression and improved pepsin activity by enhancing the conserved domain stability based on a scissor-like model. LWT 2022, 167, 113877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhakat, S. Pepsin-like aspartic proteases (PAPs) as model systems for combining biomolecular simulation with biophysical experiments. RSC Adv. 2021, 11, 11026–11047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hánová, I.; Brynda, J.; Houštecká, R.; Alam, N.; Sojka, D.; Kopáček, P.; Marešová, L.; Vondrášek, J.; Horn, M.; Schueler-Furman, O.; et al. Novel structural mechanism of allosteric regulation of aspartic peptidases via an evolutionarily conserved exosite. Cell Chem. Biol. 2018, 25, 318–329.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shintani, T.; Nomura, K.; Ichishima, E. Engineering of porcine pepsin. Alteration of S1 substrate specificity of pepsin to those of fungal aspartic proteinases by site-directed mutagenesis. J. Biol. Chem. 1997, 272, 18855–18861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nestl, B.M.; Hauer, B. Engineering of flexible loops in enzymes. ACS Catal. 2014, 4, 3201–3211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhakat, S.; Söderhjelm, P. Flap dynamics in pepsin-like aspartic proteases: A computational perspective using plasmepsin-II and BACE-1 as model systems. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2022, 62, 914–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koshland, D.E. Application of a theory of enzyme specificity to protein synthesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1958, 44, 98–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Protein–Ligand Complexes | ΔGBind (kJ mol–1) |

|---|---|

| RmuAP1–PQPQ (0–10 ns) | 3.6 |

| RmuAP1–PQPQ (90–100 ns) | 6.0 |

| RmuAP1–PQQP (0–10 ns) | 3.3 |

| RmuAP1–PQQP (90–100 ns) | 5.5 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, Y.-H.; Lin, C.-L.; Meng, M. The Adaptable Binding Cleft of RmuAP1, a Pepsin-like Peptidase from Rhodotorula mucilaginosa, Enables the Enzyme to Degrade Immunogenic Peptides Derived from Gluten. Biomolecules 2025, 15, 1725. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom15121725

Zhang Y-H, Lin C-L, Meng M. The Adaptable Binding Cleft of RmuAP1, a Pepsin-like Peptidase from Rhodotorula mucilaginosa, Enables the Enzyme to Degrade Immunogenic Peptides Derived from Gluten. Biomolecules. 2025; 15(12):1725. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom15121725

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Yu-Han, Chia-Liang Lin, and Menghsiao Meng. 2025. "The Adaptable Binding Cleft of RmuAP1, a Pepsin-like Peptidase from Rhodotorula mucilaginosa, Enables the Enzyme to Degrade Immunogenic Peptides Derived from Gluten" Biomolecules 15, no. 12: 1725. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom15121725

APA StyleZhang, Y.-H., Lin, C.-L., & Meng, M. (2025). The Adaptable Binding Cleft of RmuAP1, a Pepsin-like Peptidase from Rhodotorula mucilaginosa, Enables the Enzyme to Degrade Immunogenic Peptides Derived from Gluten. Biomolecules, 15(12), 1725. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom15121725